1 Introduction

The health crisis caused by Covid-19 has taken us all by surprise. The response of the educational sector to preventive isolation and quarantine policies has been characterized by an untimely migration of face-to-face academic activities to virtual (online) environments. In most of Latin American countries, this situation has evidenced numerous weaknesses in the educational systems through its different stakeholders, more specifically educational institutions, the Ministries of Education and students with their families (MEDINA-GUILLEN et al. , 2021).

In this sense, numerous universities, especially public ones, have had to end their academic activities untimely and call for early vacations because, (1) or they did not have pedagogical strategies enabled to provide their services remotely through online tools or (2), their teachers were poorly trained for this or (3), because their student population did not have sufficient financial capacities to support these virtual Education processes ( EL ESPECTADOR, 2020 ). This situation also extends to a large part of the country’s public schools, which casts doubt on the effectiveness of the educational policies implemented in previous years in terms of providing infrastructure, connectivity and teacher training in public Education and suggests urgent processes of transformation in these matters.

Across the continent, universities have begun to implement digital transformation processes of their teaching processes ( OROZCO TASCÓN, 2020 ), in a mix that combines the activation of synchronous online encounters and to a lesser extent, participation in asynchronous learning activities.

An analysis based on the reactions of some families and educational experts on the current processes of digital transformation of university´s academic activities reveals the poor understanding of the scope that virtual environments provide for Education (CELEDÓN, 2020) thereby generating feelings of disagreement, nonconformity, confusion and uncertainty.

In order to contribute to the clarification of these uncertainties and confusions, we present below some reflections regarding virtual Education when it is deployed in conditions of “compulsoriness” that clearly differ from those that existed before the current crisis in Covid- 19 and that they will most likely be affected after its proper ending.

2 About ICT supported Education

Education is a complex social structure that is supposed to develop in response to the demands of the social and economic dynamics of its time ( APPLE, 2011 ). Traditional Education, based on a teacher-centric approach, derives from an era of resource scarcity: teachers and books were difficult to obtain, so knowledge was not widely available; not to mention difficulties in communication ( RURY, 2004 ). Shifting to a student-centric approach on a socially massive scale is a consequence of having resolved that shortage and also a result of a shift in self-awareness through networked individualism ( CASTELLS, 2007 ; WILLIAMSON, 2013 ) in which lifelong learners need continuous self-upgrading and development to cope with the changes in current labour markets ( LOWE; GAYLE, 2016 ).

Education in Latin America has shown interesting changes since the mid 90s, when the massification of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and, mainly, the Internet, provided a new face to Distance Education (DE) that had been widely implemented during the previous three decades. This resulted in what became known, in this context as Virtual Education (VE) ( EDEL-NAVARRO, 2010 ).

Since the early stages of the incorporation of the Internet into educational processes, especially in Higher Education, the need to transform educational models and make them more student-centered has become evident (RESTREPO-PALACIO; CIFUENTES, 2020). However, despite these affirmations in specialized literature, the educational tradition of many decades has continued to maintain its status, so much so, that the vast majority of ICT-based learning experiences both in primary, secondary and Higher Education are still centered on the teacher.

In most of developing countries, ICT educational integration began to permeate face-to-face Education slowly; initially, through the use of online content, the incorporation of smartboards and Learning Management Systems as classroom support tools, and through a cautious redesign of curriculum in which some blended learning pilot experiences emerge ( RAMA, 2014 ); these were later converted into flipped classroom attempts.

Notwithstanding the great diversity of these experiences, the general characteristic of these technological implementations has been the scarce transformation of teaching practices, represented, mainly, in the focus on updating the means and ways of information transference ( MEASLES; ABUDAWOOD, 2015 ).

It should be noted that ICT integration has become a key subject for current Latin American educational requirements ( MOHD; SHAHBODIN, 2015 ). This includes access to broader collaborative spaces, better use of teaching and learning resources, and the reduction of educational costs, among others. Such integration is complex and is manifested in many ways, one of which is presented as a growing and emerging trend called the Open Educational Movement (RAMÍREZ; GARCÍA-PEÑALVO, 2015). This movement is especially relevant for some Latin American countries where the use of ICT is in a process of consolidation and is becoming a major alternative to improve the quality of Education on the continent ( FISCHMAN; RAMIREZ, 2008 ).

In this context, governments and universities are proposing ICT-related educational policies, especially regarding VE and, more recently, on Open Education. As a result of these initiatives, some interinstitutional and transnational academic communities have emerged such as Clarise (Latin American Regional Community of Social and Educational Research) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco)/International Council for Open and Distance Education (ICDE) Chairs on Open Educational Movement for Latin America, from which a notion of Open Education based on free access and open social interaction is being promoted ( MONTOYA, 2015 ).

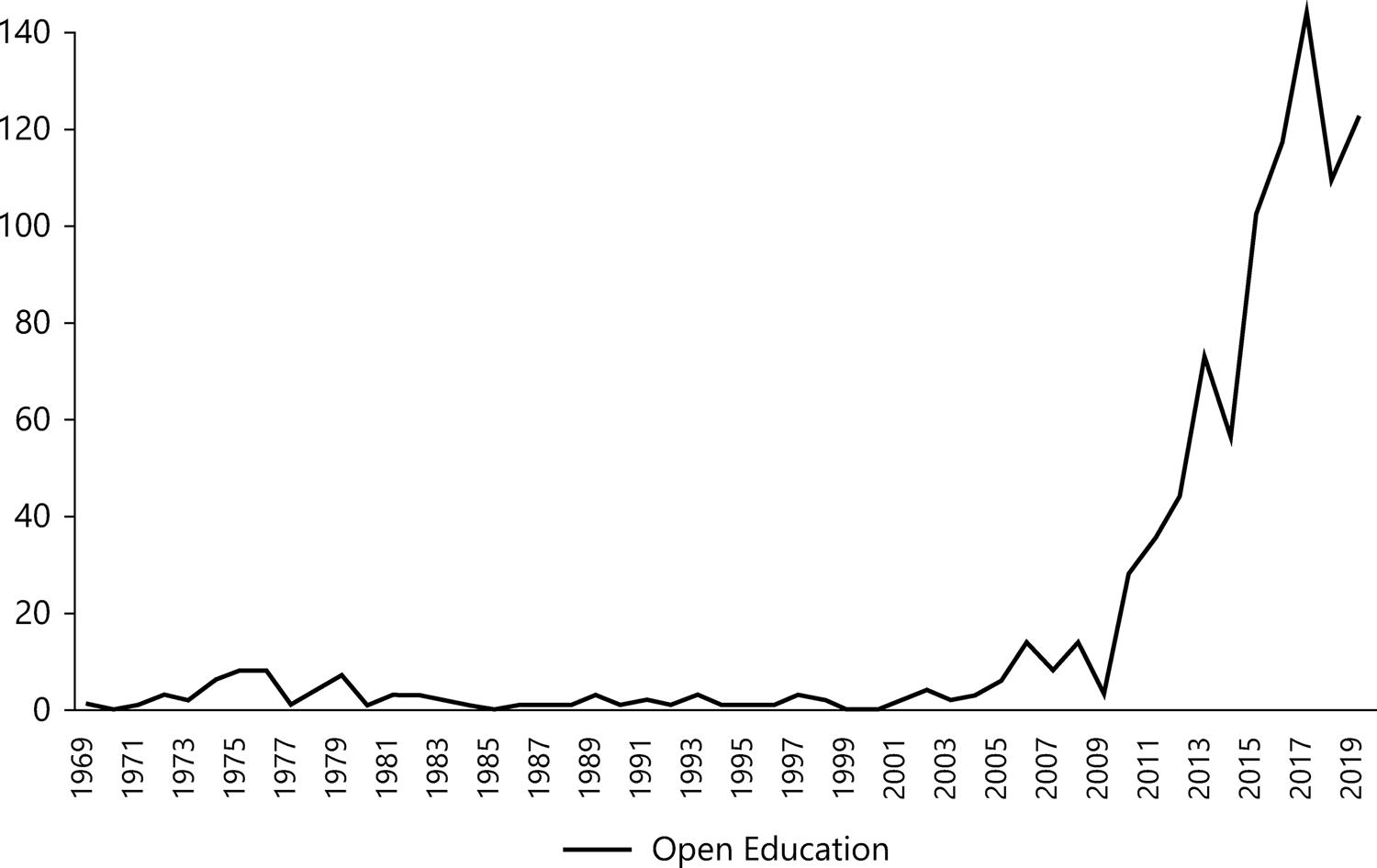

Regarding the above, it is noteworthy that there is no consensus about the meaning of Open Education. As presented in Figure 1 , a review of research about Open Education, carried out in the last 50 years, shows that it has been a matter of interest for the educational community for a long time and that it has been addressed differently in two stages: the first which comprises from the late 60s to the late 90s and the second, mainly focused on the first two decades of the 21st century.

Source: Own elaboration based on Scopus data (2020)

Figure 1 Research about Open Education on Scopus

Moreover, the interpretation of Figure 1 not only shows that Open Education is a research topic of growing interest, it also turns out to be a topic with great research potential, given the low annual production of articles related to this topic, compared to other current educational issues of great relevance.

In a first moment, Open Education was closely linked to DE and its central concerns were focused on providing access to Education ( GURI-ROZENBLIT, 1993 ; NODDINGS; ENRIGHT, 1983 ) from a spatial perspective in terms of travel limitations to university campuses. In a second moment, more linked to VE as a clear reflection of the educational impact of ICT at the time, Open Education was focused on issues related to free access to educational content, in the form of Open Educational Resources (OER) ( MISHRA, 2017 ; PELÁEZ; YUNGA, 2016) and more recently on Open Educational Practices (OEP) and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC) (CZERNIEWICZ et al. , 2017; KAATRAKOSKI; LITTLEJOHN; HOOD, 2017).

In this regard, Unesco (2012) defines OER as:

[…] teaching, learning and research materials in any medium, digital or otherwise, that are in public domain or have been released under an open license that allows free access to such material and their use, adaptation and redistribution by others without any or limited restrictions (p. 2).

For their part, Matías and Perez (2014) indicate that MOOCs are:

[…] a phenomenon that has achieved strength in recent years and integrates the connectivity of social networks, access to a recognized expert in a field of study and a collection of free access online resources, and its most important quality: the possibility of active participation of several hundred to several thousand “students” who self-organized according to their objectives, prior knowledge and skills and learning common interests (p. 42).

Regarding this, García Aretio (2015) beyond proposing a definition for MOOC – which, by the way are abundant, in the literature - raises a number of questions the educational academic community should answer about its nature as an online course, its massiveness, and its openness. In addition to the aforementioned definitions, it should be noted that there are different conceptions about OER and OEP with equally different practical implications.

Taking into account the previous considerations, and considering the current importance of Open Education for the educational context in Latin America, a highly diverse understanding on this matter becomes a serious problem, especially for those who are in charge of designing and executing educational policies in the continent ( RUBIANO, 2013 ).

In this paper, a complementary conception of Open Education is presented in order to contribute to the conceptual discussion on this topic, in the frame of what was addressed in the “introduction” section.

The conception os Open Education is addressed in relation to other, better-known, educational alternatives to which it is closely related: VE and DE. This conceptual exercise entails simultaneaously addressing the theoretical ambiguity that exists between these educational modalities and providing some elements of reflection and analysis about them.

In this regard, some scholars argue that Online Education called as “Virtual Education” (VE) in the Latin American context is equivalent to an evolved stage of DE ( LARREAMENDY-JOERNS; LEINHARDT, 2006 ) on the other hand, others argue that they are different in so many respects that it is not possible to consider them within the same educational category ( MORALES, 2014 ). This leads on to propose some questions to address in this paper about Open Education and its relation to DE and VE. Are they the same? Are they closely related? Or, should Open Education currently be conceived in a very different way?

3 Tensions between DE and VE: a proper field of reflection about Open Education

Open Education re-emerges in the space of an increasingly networked society, which makes the study of its relations with currently prevailing ICT-based educational developments such as VE and even also with DE relevant. This still seems to be a major issue among the educational community worldwide ( ARSHAD; SAEED, 2015 ).

As mentioned previously, there is an academic debate trying to elucidate the relation between VE and DE. A summarized view of the current debate was recorded a few years ago by Simonson, Smaldino, Albright & Zvacek (2012), who state that VE is a rather confusing term to describe a case of DE because of the meaning of the term “virtual”; thus, it is more appropriate to use terms such as online Education or distributed education, which is already extensively used in European and Commonwealth countries, while the term “virtual” is widely employed throughout Latin America ( RAMA, 2004) .

Based on the review of Garrison´s mid 80s “generations model” and the more recent model of Moore and Kearsley (2011) it is possible to say that development of DE has gone the way of evolution instead of revolution. In this regard, did VE evolve in the same line of DE, somehow replacing the original concept? Or did it split off from DE as a different species colonizing new educational environments? If this is true and now they coexist, a clear characterization of VE is relevant in order to avoid practical and conceptual misunderstandings.

A deeper approach to analyzing the relationship between VE and DE leads us to mention that there are both similarities and differences between them which are located in two different dimensions: time and space versus method, logistics and pedagogy. From the space-time perspective, the closeness of VE with DE is evident. One of the characteristics of VE is that participants in the educational process will not meet in the same place and much of their interaction IS asynchronous ( HIRUMI, 2002 ). This makes VE a type of DE process. On the other hand, from a methodological and pedagogical perspective the differences between them are quite considerable.

The traditional model of DE in Latin America promoted learning experiences in which students focused on reviewing study materials carefully prepared by universities. These materials included not only the content but work guides with activities to be carried out by the students as they went through the planned curriculum. Sporadic feedback encounters were established within each study plan; in them, a tutor moved to a strategic site near the student´s place of residence to answer questions or concerns about the study materials.

In this model, interactions between student and tutor were sporadic and pre-programmed and the learning approach was focused on independent study or self-study ( ANDERSON; DRON, 2011 ). On the contrary, the use of ICT as a structural component of VE allowed the transformation of learning from individual and isolated content review to a mainly collaborative experience. Unlike the traditional scheme of DE, the quality of VE is built upon continuous and personalized support and feedback ( VRASIDAS, 2004 ). In that sense, current Open Education is closer to VE than to DE regarding the greater possibilities of suitable and personalized interactions provided by MOOCs and other open learning spaces.

Given the above, in the context of the current health crisis due to the Covid-19, many questions have been raised about whether the synchronous online meetings that are being deployed through videoconference tools as a strategy to replace face-to-face classes could be called “Virtual Education”.

In this sense, two main issues could be considered: The first has to do with the fact that the term “virtual” does not refer to pedagogy or method, but rather to the environment in which the educational process unfolds, that is, that teaching and learning takes place through digital environments, remotely (PALVIA et al ., 2018). In this sense, a live synchronous online meeting would fulfill this characteristic and could be included as a component of VE. On the other hand, the second issue hints that virtual environments provide different solutions to different educational problems. The replacement of a traditional face-to-face lecture could have in an online videoconference a quite similar substitute to the original. However, we must consider that this way of educating serves well to some educational purposes and at the same time has quite a few limitations, both face-to-face and virtual. If a more complex learning process is required, clearly synchronous online encounters would fall short in scope and a more elaborate vitual strategy based on an instructional design deployed through asynchronous learning activities would be required.

4 Open and Distance: two terms related but not equal

The history of DE shows that it was considered, to a certain extent, a surrogate of conventional Education ( ANDERSON; DRON, 2011 ), albeit one committed to granting access and equal quality to everyone. In the Higher Education context, the term “open” became part of a widely recognized educational formula, Open and Distance Learning (ODL), which historically appeared after the foundation of the Open University in the United Kingdom ( BELL; TIGHT, 1993 ), and was somehow consolidated in subsequent European policies under the Socrates program and its Minerva action initiative. The first meaning of “openness” in this historical context would imply “for all”, in terms of granting access for all sectors of society.

As the ODL formula tended to amalgamate “Open” and “Distance”, it is important to differentiate and separate them. DE points to a modality that emerges under certain conditions as a complementary instance of face to face education, while Open Education attempts to describe a certain type of educational practices which could be applicable to any educational case. Viewed from the educational domain, the “open” character can be applied to the locus (place, location, venue, environment or space), the lapse (time, time-sharing frame, concurrency), the contents, the methodology or any other dimension of Education (GARCÍA ARETIO; RUIZ CORBELLA; DOMÍNGUEZ FAJARDO, 2008).

Open Education was also known as the movement to reform American and British Education in the 1970s and hence the term was used as opposed to “traditional” education. Walberg & Thomas’ 1972 operational definition of Open Education was devised for a childhood learning context, and now, some decades later, most of their principles, apparently lost in time, seem to be revolutionary for the current higher educational context ( NYBERG, 2010) .

Some of those principles are now considered ICT-based and refurbished “openness” attributes which focus mainly on allowing access to educational content, fostering free transit among different learning environments and encouraging conversations among learners with diverse backgrounds and interests. Also, these attributes seek to achieve peer interaction and collaboration as a key factor of learning, to emphazise a guiding and advisory role of teachers and foster an adequate emotional climate in the “learning collective” in order to provide proper conditions for deep learning (SCHUWER; VAN; HATTON, 2015).

Under the contemporary understanding of Open Education as a strongly ICT-mediated set of OEP characterized by the application of attributes of “openness”, it is possible to identify both similarities and substantial differences between Open Education and DE. In that sense, although MOOCs (understood as an Open Educational instance) are learning experiences clearly in which students and teachers are not in the same place and their interactions represent a scenario of DE (BONK et al ., 2015), various other OEP such as open teaching, open assessment or even the use of OER, also apply to face-to-face education. In fact, the original “for all” meaning of “open” related to DE not only applies for those who have problems accessing education, but now also means “with others”, “with anyone”, “with all”. In this regard, learning with all, with anyone at a distance, supposes a new way of learning in collaboration, far beyond the traditional concept of “working in groups” or “team work” conformed by people with similar backgrounds and characteristics, reaching the level of learning and “collaborating with the world” ( GUY, 2016 ).

5 Open and Virtual: from teacher and team feedback to social crowd feedback

We said earlier that Open Education and DE had a common origin and that although they still have their similarities, their differences are actually much more significant. Well, something similar happens between Open Education and VE. If the latter is considered an evolutionary refinement of DE, Open Education would stand as part of it; a part that manifests itself in a very different way than what we are used to.

Since its beginnings in the mid-90s, VE has been built on a quality scheme based on personalized feedback and the monitoring of the teacher who finally takes on a mentoring role ( LIEPONIENĖ; KULVIETIENĖ, 2010 ). Regarding the mentioned in the previous section about collaboration in an open learning environment, this gives us an idea of an open approach to feedback and the relations among the different participants in this kind of educational process. The interactions generated in such experiences characterized by sharing, reusing, adaptation, redistribution and collaboration “with the world”, produces feedback that is typically different from the one given by a single expert in the discipline or in online pedagogy ( RAI; CHUNRAO, 2016 ). This allows enriching feedback with less experienced but possibly richer points of view from people with a diversity of educational experiences and socio-cultural backgrounds (crowd).

In fact, in the context of current Open Education it is considered that the teacher is not the only person who can give effective feedback and that anyone is able to contribute to anyone else’s learning. This takes the feedback beyond collaborative, to something social.

Regarding the above, it is evident that both Open and VE are essentially collaborative, but in different ways. VE is more focused on working teams in collaboration mainly configured by peers who share a common space of enrolment ( AVELLO MARTÍNEZ; DUART, 2016 ). Meanwhile, in addition to providing the foregoing, current Open Education enables social feedback in the context of communities of practice and learning. It is noteworthy that such communities are composed by peers from diverse contexts that are not necessarily “classmates” and that have few things in common except their interest in learning, their information and technological skills, and a temporary coincidence in these educational spaces.

The aforementioned subject is framed in the general quality model for Distance and VE which is based on an adequate interaction between individuals (almost always between tutors and students), which implies some kind of social connectedness. In current Open Education, the interaction is also between individuals and, moreover, between individuals and a social crowd. Even though collective feedback is not new in educational context ( EDELSTEIN, 2015 ), (such as Vygotsky’s scaffolding, Bandura´s social learning theory and Berger & Luckmann´s social construction of reality), the current educational context and its stakeholders are very different. In a networked society, social collectives open up new possibilities of interaction and spaces for learning with others.

Thus, “learning to be” an active and contributing practitioner in a community becomes more important than “learning about” something ( BROWN; ADLER, 2008 ). Open Education promotes an exchange of knowledge among educational stakeholders, which is possible due to active participation and sharing. In that sense, Open Education becomes multidirectional where every stakeholder can contribute to the educational process, configuring a community-based teaching collective.

There are many questions arising from this approach. The tension between the market value of Education and the social need for educated laborers should be a matter for reflection and lead to enhanced policy making all over the world ( PETER; DEIMANN, 2013 ). As a new culture of sharing arises ( BROWN; ADLER, 2008 ), there is still the need to solve the issue of costs of contribution, production and effective distribution of knowledge.

In addition to the above, another issue linked to the quality of education is the effect of “openness” on the richness of feedback received by the student. Feedback is important in any educational process and, traditionally, teachers have been the main and “authorized” sources to provide feedback (PRICE et al ., 2010). However, social or crowd feedback allows for the creation of stronger situated learning. To address this point, let us consider for a moment that School is an artificial construct, a place “outside the world” where students are gathered to learn about that world. In this context, most teachers as part of such artificiality, teach about things that are not part of their living context. On the contrary, if as an example we consider a geography teacher who has traveled and has witnessed “with his own eyes” the geography he teaches, the feedback his students would receive would be much deeper and meaningful. Then, considering the above we could imagine the potential of feedback if instead of a person we could go to a crowd as a source of interaction.

Also, considering today´s learning context, in which constant and rapid change is a reality, feedback provided by a collective will be updated as soon as change happens; thus, learning will be more relevant and socially pertinent.

6 Conclusion

Although Open Education is not the ultimate solution for the current educational crisis caused by Covid-19 in Latin America and all over the world, it is presented as a growth factor of flexible and freely accessible collaborative learning environments, which are in constant struggle against an individualistic educational baseline that hinders its true possibilities and potential.

Beyond that, it is important to create awareness as to the extent to which theoretical efforts aimed at understanding changes in Education are currently focused on the technological domain rather than on the domain of educational theory or pedagogy. Like any human practice, Education is affected by technology, but in order to understand the formation of novel socio-technical systems, the focus should be on human action ( FU, 2013 ). Familiar educational practices like teaching, assessing or designing curricula – either in technology-mediated or in technology-depleted environments – can be subject to or led to offer ‘openness’ features or attributes. The outcome should be social and crowd-sourced; with more collaborating, reusing, sharing, remixing, using open educational content and providing feedback.

Noticeably, we should to use the term “stakeholders” rather than teachers or students, in order to represent all the parties involved in current Open Education. One of such stakeholders is the “social collective” (or crowd) – understood as an impersonal agent – which sometimes acts as a secondary “teacher”, sometimes as a “classmate”, and always as an observer, a witness, even a judge; beyond that, the crowd is also a broadcaster and a learning mediator. The roles of the stakeholders in current Open Education vary to accommodate the different uses of available resources and the levels of technological mediation involved.

So, why is social-sourced, crowded and collaborative ICT-based Education relevant for the current Covid-19 crisis, particularly for Latin American educational context?

The current, accelerated rate of change in technology in the region is a driving force for educational innovation and stakeholders are trying to seize the emerging opportunities in order to solve educational problems or improve existing solutions. However, in addition to the mandatory confinement caused by the Covid-19 crisis, in the current Latin American educational context there is a list of educational problems that can be addressed by crowd-based Open Education; these include insufficient educational opportunities and the elevated costs of higher education, the lack of time for those in the work force and the limited access to digital learning resources of high educational quality ( AMIEL; SOARES, 2016 ).

An alternative solution to these problems and to excessive use of webconferencing can be found in the participation in Communities of Practice and Inquiry (CoP), spaces in which interaction with social collectives (crowd interaction) occurs naturally ( WENGER, 2010 ). Moreover, it could be said that the current Open Education should be structured based on CoP that share and reuse their knowledge openly.

The future integration of Higher Education into Latin American society will depend on its capacity to effectively incorporate the potential of social collectives as an element of educational enrichment. Thus, Open Education reveals itself as a suitable response to current challenges, and can even be considered a key to a new shift in educational “paradigms” towards a wider social perspective.

Covid-19 has forced us to isolate ourselves socially, but that does not mean that we must continue learning in isolation. An alternative like crowd-based Open Education will allow us to reconnect and share our learning, not only with our teachers and classmates, but with the whole world.