1 Introduction

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan and other post-Soviet countries have faced simultaneous demands for political and economic transitions to move away from their Communist past. Higher Education has been both a driver and a reflection of such transitions, playing a central role in the discussions of policy futures associated with democratization, Europeanization and market-oriented globalization. Thus, internationalization was considered as modernization ( KUZHABEKOVA, 2020 ), allowing Kazakhstan to become progressively integrated into globalization trends. The transition to a market economy and globalization necessitated the training of economists, international workers, lawyers, translators and managers, who, in the independent Kazakhstan, would have to think and work in different ways than they did during the Soviet period. It was widely argued that one of the obstacles to the training of personnel and the development of Kazakhstan was the lack of a self-sufficient, market-oriented Higher Education system (RUSTEMOVA et al ., 2020).

The process of the internationalization of education, aimed at the implementation of the following goals, is one of the most important indicators of the quality and efficiency in the university’s educational activities, which determines its prestige at the international level:

broadening the scope of universities beyond their national education system;

diversification and growth of financial income through attracting foreign students;

broad and balanced mobility of students, teachers and researchers;

expansion of partnerships with foreign universities;

improving educational quality through student and teacher participation in the international process of knowledge exchange and production.

The processes of economic internationalization and globalization, the formation of a single economic space, the setting up of a common market and the technological revolution all contributed to an increase in the students’ academic mobility. The number of students studying abroad has increased fifteen times in the last five decades ( FILIPPOV; KIRABAEV, 2010 ).

Currently, Kazakhstani universities are being introduced to the global market of educational services in the midst of fierce international competition among leading universities. The demand for highly qualified specialists is impelled by the driving forces of globalization. A university’s primary task is to prepare highly qualified competitive personnel ( ABDIMANAPOV, 2018 ).

The First President of the Republic of Kazakhstan underlined the need to improve the country’s competitiveness. He suggested that each Kazakh should possess a set of qualities important for the twenty-first century. Among those qualities are computer literacy, foreign language proficiency and cultural openness (NAZAEBAYEV, 2017). This political will to internationalize Kazakhstan aimed mainly at economic goals. Kazakhstan is by far the richest country in Central Asia and benefits from huge natural resources. On average, from 1999 to 2014, Kazakhstan spent 1.7% of GDP on education and about 13.0% of its total educational budget on Higher Education, compared to the other Central Asian countries, which devote an average of only 1.4% of GDP on education and 9% of their total educational budget on Higher Education ( HANSON; SOKHEY, 2020 ).

One of the strategies used by Kazakhstan to enhance the internationalization of Higher Education was to join the Bologna Processes in 2010. This entry into the European educational space was implemented in the context of national interests in the development of the country’s foreign policy aimed at cooperation with Europe, including joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) and participating in the international market for educational services. With Kazakhstan joining the Bologna Process, the main objective of the state educational policy for the future was to focus on delivering Higher Education in line with today’s international standards. The internationalization process in Kazakhstan can be described in a certain way as Westernization ( SPERDUTI, 2017 ). However, the republic’s entry into the Bologna process has given rise to several difficulties ( TEMIRTASSOVA, 2019 ). Indeed, the adoption of Bologna processes may be considered as top-down Higher Education policy that underestimates the real situation affecting Kazakh universities, human resources and potential.

Ultimately, we observe that the question of the internationalization of Higher Education is a priority for public policies in Kazakhstan. However, it is always more complicated to move from political will to implementation.

2 Literature review: Internationalization policies and their impact in Kazakhstan and elsewhere

Before summarizing the literature review, it is useful to define the concept of internationalization. Indeed, the idea of internationalization of Higher Education is not easy to define. Most observers’ understanding of internationalization is related to Higher Education activities such as: curricular development; student and faculty exchange; intercultural and language training; the number of international students; and joint research initiatives. Internationalization is the process of integrating international dimensions into teaching, research and educational provision ( KNIGHT; DE WIT, 1995 , 1999 ). According to Thondhlana, Garwe and De Witt (2020), internationalization includes the following domains:

Outbound and inbound student mobility;

Academic staff mobility;

International collaborative research, conferences and journals;

Institutional linkages;

International presence/cross-border Education/international branch campuses;

Internationalization of the curriculum (at home);

Regional and local connectivity;

Ranking;

National policy for internationalization;

Curriculum/educational programs.

We will address in this paper mainly internationalization at home with a focus on inbound student mobility, international branch campuses and the recruitment of foreign academic staff in Kazakhstan.

The impact of the internationalization of Higher Education in a country will depend on many factors including the resources used. The impact is both on individuals (students and staff) but also on power relations between universities and within each university. Internationalization is closely tied to the specific history, culture, resources and priorities of the specific institutions of Higher Education operating in a country ( YANG, 2010 ). One of the main forms of Higher Education internationalization is academic mobility, which is important for personal development and career opportunities. It helps students and faculty alike to become more open minded, respectful and to seize opportunities to learn about other cultures ( GOHARD-RADENKOVIC, 2004 ).

According to Papatsiba (2003) , mobility can also be understood in a broader concept—the ability to change one’s place of living. There are various forms and reasons for mobility, such as: geographic, social, economic, political, cultural, educational, professional, urban, national, international, internal, external, individual, collective, self-comforting reasons, necessity and family. Murphy-Lejeune (2003) views mobility as the feature of an individual who is able to move abroad and adapt easily. Mobility is not only a geographic process, it also includes cultural, linguistic, social, psychological and professional processes. Making the decision to move, settling into a new home, gradually adapting to a new linguistic, cultural and professional environment, building social relations and altering behavior and personality all require specific skills.

Anquetil (2006) demonstrates that most of the students adapted to the local system of multiple exams, accepted “others” as they were, experienced international friendship, visited tourist places and, ultimately, broadened their minds. Murphy-Lejeune (2003) suggests that mobility capital consist of four components: personal or family history; previous mobility experience; language competency; and adaptation experience and personal features. These indicators give an opportunity to measure changes in cultural, linguistic, scientific and personal experiences before and after an episode of mobility.

Bearing in mind these various parameters, in Kazakhstan there is a gap between the political will to internationalize and the potential of Kazakh universities: “Kazakhstan’s Higher Education is still in its infancy compared to many countries, as it lacks strategic vision and the level of resourcing needed to make a real difference” ( TEMIRTASSOVA, 2019 , p. 54). In this context, the internationalization of learning is booming at university mostly at the institutional level. At this level, it is easy to pay lip service to introductory outcomes for international and intercultural learning, since that is not where they are assessed. The real challenge is to contextualize internationalized learning outcomes in individual study programs and to support academics in crafting outcomes and assessment—in other words, “internationalization at home”.

Analyzing internationalization through research in Kazakhstan, Moldashev and Tleuov (2022) suggested that universities’ policies focused mainly on obtaining publication in international peer-reviewed journals that were indexed in Scopus or WoS databases. This orientation often leads to the gaming and token-conformity response types. Due to the lack of necessary research experience and training among doctoral students, publication requirements for obtaining a Ph.D. degree mostly led to the token-conformity type of response. In addition, Ph.D. students who study under a government scholarship are also required to complete their studies in three years, which puts additional pressure on them. The huge pressure in terms of publication requirements and sponsorship duration in Kazakhstan leads to the spread of unethical practices, including reliance on predatory journals and the use of corrupted co-authorship arrangements to get articles published.

In Kazakhstan, internationalization has been mostly a movement toward close relations with West European and North American universities. Nevertheless, since the 1990s, ties with China have become closer. The opening of borders has relaunched population movements in both directions: pendulum flows of small traders; Chinese migrants settling in Central Asia; and Central Asian students, mostly Kazakhs, leaving for China. These movements play a key role in the perception of China. For Central Asians who travel regularly to China, this trade offers specific access to certain aspects of Chinese culture, spreading the image of a country with unique business opportunities, where front-line technology rubs shoulders with everyday objects ( LARUELLE; PEYROUSE, 2012 ).

It is interesting to observe that Kazakhstan addresses the issue of internationalization in a different way from that of China. While in Kazakhstan, internationalization may be considered as the importation of the North American or Anglo-Saxon model, in China there is a tendency to build a Chinese model of world-class universities. As pointed out by Vergnsud and Palisse (2018), Chinese universities must be the spearhead of national soft power and compete in the rankings for the best institutions in the world. To do this, new “competitiveness programs” have been put in place to support the major project of the “Chinese Dream” and help it to become, beyond rhetoric, a real alternative to the “American Dream”.

The Kazakh dream of Western driven internationalization is hard to achieve. Kuzhabekova, Baigazina and Sparks (2022) pointed out that Western host universities’ engagement in hosting mobile faculty coming from Kazakhstan on short visits seems to be driven predominantly by neo-liberal profit-seeking motives rather than by a more humanistic desire to serve the larger global society by sharing its expertise or to engage in equal and mutually beneficial partnership relationships.

3 Research objectives

Internationalization at home touches upon many dimensions of the university in Kazakhstan, from the academic curriculum to the interactions between local students and international students and faculty, to the cultivation of internationally-focused campuses and to innovative uses of digital technology. Internationalization at home aims primarily at giving the large majority of students who do not spend time abroad international contacts and to create an international environment in order to strengthen their intercultural linguistic and academic skills. A confusion arises around the overlap between internationalization at home and internationalization of the curriculum, which refers to dimensions of the curriculum regardless of where it is delivered.

To analyze internationalization at home in Kazakhstan, we address the following three research questions:

4 Methodology

This study seeks to describe the phenomenon of internationalization of Higher Education in Kazakhstan and to explore in depth the ways government and university policies tried to accelerate the development of internationalization in a post-soviet system of Higher Education. We used a mixed method, combining an analysis of quantitative and qualitative data.

The data used to answer our research questions came from two main sources. On the one hand, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) statistical database (uis.unesco.org) and recent surveys on internationalization of Higher Education in Kazakhstan allowed us to describe the flow of student mobility (In and Out) with the most recent statistics available and to identify the list of foreign universities founded in the country during last years. We compared and combined in our analysis quantitative data national and international statistics.

And, on the other, we consulted and analyzed institutional and government reports dedicated to internationalization. The categories of our qualitative analysis were guided by the trends we found in the literature review. As three of the four authors of the paper are academic staff in the oldest and most prestigious public university in Kazakhstan, they did several informal discussions with staff in central administration and International office of their university in 2019 and 2020.

As the phenomenon of university internationalization is recent in Kazakhstan (less than 30 years) and not clearly stabilized, we adopted an exploratory research perspective conducted to have a better understanding of the existing problem (why Kazakh university internationalization is struggling?), but will not provide conclusive or generalizable results.

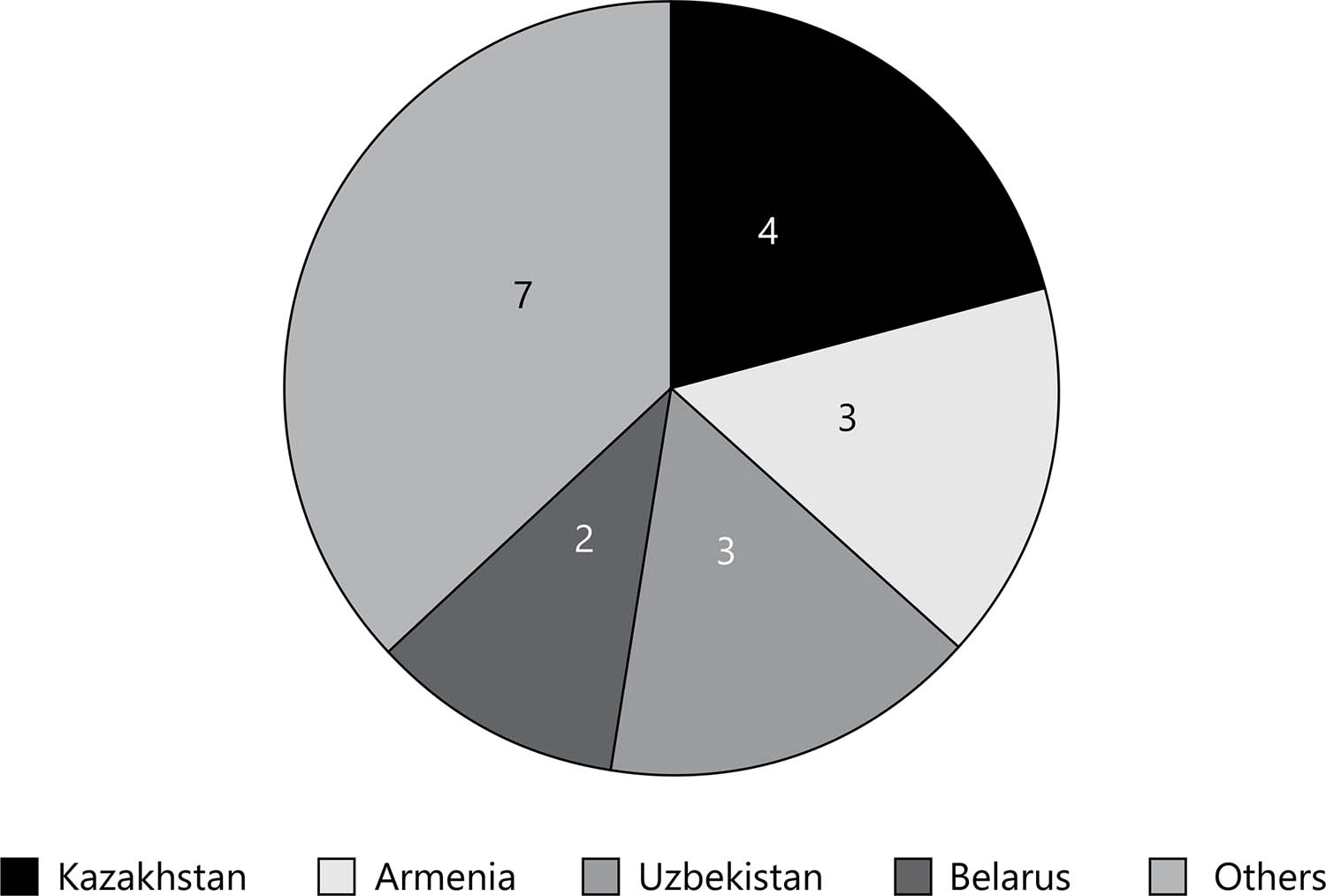

5 Framing the discussion: international students in Kazakhstan

Outbound student mobility has been increasing in the last thirty years, in particular with the launching of the Bolashak scholarship scheme (PERNA; OROSZ; JUMAKULOV, 2015). However, inbound academic mobility of students is poorly developed in Kazakhstan compared to outbound mobility. This mobility remains low with students coming largely from Central Asia. Although the “Strategy for Academic Mobility in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2012‒2020” ( KAZAKHSTAN, 2012 ) pointed out the importance of balanced mobility (outbound and inbound), currently only 9,077 international students come to Kazakhstan, as opposed to about 48,875 Kazakhstani students studying abroad (more than five times more). Most international students studying in Kazakhstan come from one of the Commonwealth of Independent States’ (CIS) nations, as well as India, Pakistan, China and Afghanistan ( JUMAKULOV; ASHIRBEKOV, 2016 ). From 2013 to 2019, a total of 4,006 inbound mobile students came to study in Kazakhstan. The majority of these came from the CIS and Asia. This is due to the fact that most citizens of the CIS countries speak Russian, which allows them to follow academic programs in the Russian language in Kazakhstan. Another factor is the affordability of tuition fees and the cost of living in Kazakhstan compared to European countries (RUSTEMOVA et al. , 2020).

Table 1 shows a regular increase in inbound students’ mobility from 2014 to 2019. Asia is the region where most international students arriving in Kazakhstan originated, increasing steadily between 2014 and 2019. Inbound student mobility has been broadly viewed as an important source of income and diversity on campus. The context of marketing Higher Education encourages public and private universities in Kazakhstan to attract international students ( BAYETOVA, 2019 ; SMOLENTSEVA, 2020 ). However, the Covid-19 pandemic interrupted the growth of inbound student mobility in Kazakhstan.

Table 1 Geographic origin of inbound student mobility in Kazakhstan

| Year/Regions | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | 9,691 | 8,611 | 11,286 | 12,547 | 12,962 | 20,970 |

| North America | 3 | 4 | 11 | 11 | 3 | 10 |

| Africa | 3 | 3 | 9 | 30 | 14 | 37 |

| Europe | 1,261 | 1,357 | 1,222 | 1,258 | 1,348 | 1,698 |

Source: UIS (2021)

In Table 2 , we observe that the inbound mobility rate is lower in Kazakhstan compared to those of Russia and Kyrgyzstan. By contrast, the rate of inbound mobility is far higher in Kazakhstan compared to other Central Asian countries presented in the table. It is probable that the war in Ukraine will increase the number of international students in Kazakhstan, including students interested in learning the Russian language.

Table 2 Inbound mobility rate in Central Asia and Russia

| Indicator | Inbound mobility rate, both sexes (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Country | ||||||

| Kazakhstan | 1.50921 | 1.51531 | 2.00999 | 2.21043 | 2.26755 | 3.31774 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 4.50545 | 4.79422 | 5.99593 | 6.3999 | 7.5951 | 8.97558 |

| Russian Federation | 3.04967 | 3.43472 | 3.94274 | 4.25808 | 4.54407 | ... |

| Tajikistan | 0.55362 | 0.8302 | 0.63215 | 0.84317 | ... | … |

| Turkmenistan | 0.1959 | … | … | … | … | 0.26559 |

| Uzbekistan | 0.26262 | 0.29043 | 0.27251 | 0.21425 | 0.23362 | .. |

Source: UIS (2021)

6 Importing universities, campuses, staff and learning English—a Kazakh peculiarity?

The process of internationalization of higher education in Kazakhstan involves three proactive policies that we will examine in depth. First, the establishment of campuses and foreign universities in the country. These institutions are sometimes linked to countries or to private entities. Second, we observe various mechanisms that allow academic staff of foreign origin to work in Kazakh universities. Third, the use of English as the language of instruction has been the lever of internationalization used by many Kazakh universities.

6.1 New foreign universities as a mainstream means of internationalization

In the third part of the article, we will analyze the process of internationalization of Higher Education through three mechanisms: the creation of new internationally oriented universities; the employment of university academic staff coming from abroad; and the increase in the learning and use of English.

The foundation of several universities, as shown in Table 3 , highlights the will of the Kazakh state and public and private Higher Education actors to build an ambitious internationalization policy. The state aims to build international legitimacy by improving the quality of Higher Education ( TAMTIK; SABZALIEVA, 2018 ).

Table 3 New international universities in Kazakhstan (1992‒2013)

| Institution | Founded in | International dimension | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| KIMEP | 1992 | Faculty, programs, language (English) | Almaty |

| Ahmet Yesevi University | 1993 | Partner: Turkey | Turkestan |

| Suleyman Demirel University | 1996 | Partner: Turkey Faculty, programs, language (Turkish) | Almaty |

| Kazakh American Free University | 1997 | Partner: USA | Almaty |

| Kazakh American University | 1997 | Faculty, partners (HEIs), and language (English) | Ust-Kamenogorsk |

| German Kazakh University | 1999 | Partner: Germany Faculty, programs, language (German) | Almaty |

| University of Central Asia | 2000 | Partners: Aga Khan Development Network, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, language (English) | Tekili |

| Lomonosov Moscow State University | 2001 | Partner: HEI | Astana |

| Kazakh British Technical University | 2001 | Partner: UK Faculty, programs, language (English) | Almaty |

| International Business School | 2008 | Partners: HEIs | Almaty |

| Nazarbayev University | 2010 | Faculty, partners: HEI), programs, language (English) | Astana |

| Sorbonne-Kazakhstan Institute | 2013 | Partner: HEI, language (French) | Almaty |

Source: Lee; Kuzhabekova (2018)

Kimep: Kazakhstan Institute of Management, Economics and Strategic Research

In 1992, Kazakhstan established a private, international university called Kazakhstan Institute of Management, Economics and Strategic Research (Kimep). This private university, inspired by the North American Higher Education system, began with faculty members recruited largely from outside Kazakhstan. For example, Canada’s McGill University helped establish Kimep’s International Executive Center in 1998. The language of instruction at Kimep is English ( LEE; KUZHABEKOVA, 2018 ). Shortly after the establishment of the Kimep, the Kazakhstani Government, working closely with the Turkish Government, established Ahmet Yesevi University and Suleyman Demirel University. These institutions affirmed the historical and cultural ties between the two countries. The next major international university was established in 2000 under the leadership of the Aga Khan Development Network and known as the University of Central Asia. The Kazakh British Technical University was established in 2001 through close partnerships between the Kazakh and United Kingdom Governments ( LEE; KUZHABEKOVA, 2018 ). As Table 3 demonstrates, during recent decades Kazakhstan has become a laboratory for the internationalization of Higher Education. The universities created are the result of both diplomatic initiatives by certain countries wanting to consolidate their links with Kazakhstan (Turkey, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, etc.) but also by private actors (foundations, foreign universities).

In 2010, Kazakhstan made its most substantial investment in an international university by creating Nazarbayev University (NU), presented as the country’s flagship university. NU is an archetypal creation of contemporary Kazakhstan, teaching in English, recruiting academics from around the world and expanding rapidly after admitting its first students in 2010.

It is crucial at this stage to understand and analyze the impact of the internationalization of Higher Education on the processes of state formation in the post-Socialist space—states that are (re)forming, under intense global pressures not experienced by other countries that came into existence in the mid-twentieth century or earlier, international mobility in Higher Education ( LEE; KUZHABEKOVA, 2018 ). Almost immediately after opening, the university assumed leadership among the universities of Kazakhstan and the process of internationalization has been going on since its foundation: 85% of the faculty were foreign experts who were invited to Kazakhstan; all subjects are taught in English; and the university itself cooperates with many of the top-ranking universities in the world (RUSTEMOVA et al ., 2020).

Meanwhile, offshore university campuses have continued to progress in Kazakhstan using both the Russian and English languages. Indeed, the Kazakh Higher Education system reflects a country in transition between the Russo-Soviet model and the globalized Anglo-Saxon world. While the country is becoming integrated into globalization, it is still within the sphere of Russian political, cultural and educational influence.

6.2 International staff

According to Dushinski (2017) , “incoming” or visiting foreign lecturers are more cost-effective in terms of programme implementation and economic efficiency. Foreign staff not only have an international, modern knowledge base obtained from high-quality universities, but they also share invaluable experience, which helps improve the quality of research work at domestic universities. Indeed, the process of “incoming” internationalization benefits both public and private Higher Education institutions. Foreign faculty and students also have an impact on domestic university academic environments.

Lee and Kuzhabekova (2018) investigated the case of Kazakhstan as a peripheral state that is actively pursuing internationalization. They pointed out the motivations of international academics who relocate to Kazakhstan to take up full-time employment—a reverse flow of talent that contradicts most empirical studies ( LEE; KUZHABEKOVA, 2018 ). Remarkably, nearly 40% of the participants in this study had lived in two or more foreign countries prior to moving to Kazakhstan. While hypermobility was never a participant selection criterion, its prevalence among participants reveals both an affinity for international work and the realities of today’s global academic job market. Unsurprisingly, one of the reasons to leave a country is the lack of employment opportunities. The surplus of doctorates in the United States of America and parts of Europe creates a very competitive job market in academia:

Together, these three issues represent the most common push factors that drove participants to leave their previous places of residence: job market (system level), unsatisfactory work conditions (institutional level), and age and marital status (individual level). These levels reveal the complexity of push factors, as well as differences in agency when considering relocation ( LEE; KUZHABEKOVA, 2018 , p. 377).

Interestingly, less than two years after the data collection for this study, nearly half of the participants concerned had already left Kazakhstan. While this study does not explore the reasons these participants left, this outcome raises serious questions about the sustainability of recruiting and employing international staff in Kazakhstan, in spite of rather optimistic forecasts:

In recruiting international faculty members, Kazakhstan could emphasize these dynamic changes in the country to attract talented scholars. Universities can also develop retention strategies that address the needs of international faculty members who seek meaningful work ( LEE; KUZHABEKOVA, 2018 , p. 383).

Indeed, empirical research demonstrates that the motivations of foreign staff to relocate in Kazakhstan were a mix of curiosity and a will to work in a context where it is possible to make a difference to one’s academic career:

I decided to stay at Nazarbayev University because it is always interesting. It is an opportunity to see how human capital can be systematically developed and leveraged for local, regional and global impact. It was a chance to bring my research to life. There is a long way to go but I felt like I could make a real difference here (MOWBRAY, 2019).

Some of the challenges in taking on a Higher Education teaching position in another part of the world include the need to make implicit knowledge much more explicit. Nazarbayev University has nearly 500 faculty members from fifty-nine countries. Quite naturally, all of them arrive in Kazakhstan with a fully formed view of how a university should function (MOWBRAY, 2019).

Findings demonstrate that, as expected by policy-makers promoting internationalization of Higher Education for research capacity development, international faculty do contribute to the strengthening of local research capacity in Kazakhstan. While bibliometric and social network analysis showed that they contribute by conducting research in areas identified as prioritized by governmental policies, as well as by engaging in collaborations abroad linking Kazakhstani universities to scholarly networks outside the country, research showed that they also contribute by providing apprenticeship opportunities for junior researchers ( KUZHABEKOVA; LEE, 2020 ).

As suggested by SABZALIEVA (2017) , Kazakhstan’s policies on Higher Education bear the imprints of a range of external actors, from the European Union, the Anglo-American university model, the World Bank, and including also nation-states such as China, Russia and Singapore. The government’s openness to align itself with international best practices, wherever these may be found, is not impelled by the provision of aid or a colonizing outside power, but stems from the state’s own vision. Yet, it is too early to conclude that the research university model of Nazarbayev University has lasting benefits and is sustainable.

Richardson and McKenna(2002) identified four main types of expatriate academics: (a) the explorer, who wants to discover new countries and different cultures; (b) the refugee, who wants to “escape” from unfavorable circumstances, such as an unrewarding job or a bad relationship; (c) the mercenary, who is motivated by higher levels of salary and financial benefits; and (d) the architect, who believes that international work experience will enhance his or her career progression. Probably, Kazakhstan attracts all four types of expatriate academics. This is why it is difficult to predict in the medium and long term the impact of this mode of internationalization on the country’s Higher Education system.

6.3 From one lingua franca to another: teaching in English as an internationalizing tool

Another strategy for internationalization and globalization was to promote the use of English in Higher Education in Kazakhstan. This policy results from several factors, such as the lack of competitiveness of Kazakhstani universities in the international market, the low level of technical support and the availability of accommodation services, and the small number of courses taught in English (RUSTEMOVA et al. , 2020; UVALEYEVA et al ., 2019). To increase further the number of incoming students, universities are increasing the proportion of English language courses and programs. This is also due to the broader trilingual policy at all levels of Education launched by the government (Kazakh, Russian and English). The literature suggests that inbound mobility can have positive benefits, such as, amongst others, creating an international environment in the classroom ( JUMAKULOV; ASHIRBEKOV, 2016 ).

Returning to the issue of training young people in world languages, which contributes to the internationalization of Education, it is necessary to emphasize the role of the cultural project “The Trinity of Languages” initiated by the country’s first President: “Kazakhstan should be seen around the world as a highly educated country, whose population can use three languages. They are: Kazakh—the official language; Russian—the language of inter-ethnic communication; and English—the language of successful integration into the global economy.” Thus, in deciding that its citizens should master three languages, Kazakhstan tried to adapt to the realities of the modern world: this trinity of languages will be an indication of the country’s competitiveness.

Experts believe that investment on the development of the national language should be greater and more consistent than has previously been the case. Furthermore, it is essential to maintain the position of the Russian language. Everybody understands the role of the Russian language as the language of successful inter-ethnic cooperation and its integrative function as a lingua franca . The Russian language plays a pivotal role in cultural and professional settings in Kazakhstan and knowledge of it will remain a factor of personal competitiveness for the foreseeable future. Finally, the third component is related to the importance of learning the English language, which is necessary in a globalized world with its enormous flow of information and innovation. The majority of experts agree that the idea of this trinity of languages is, in fact, a part of a national ideology designed to enhance Kazakhstan’s competitiveness ( ALTYNBEKOVA; ESTIMOVA, 2019 ). Kazakh students are highly motivated to learn English and this requires structural changes within academic programs (PALATOVA et al., 2020). Yet, the question of the applicability of the three languages within the whole Higher Education system in Kazakhstan is still under debate. To put it simply, the resources and skills needed are not at present available to build quality skills in three languages among the majority of students.

7 Discussion

Kazakhstan’s educational policies aim to develop Education in accordance with global standards, improving quality and integrating the country into international scientific and educational communities. Referring to post-Soviet universities, Chankseliani (2022) pointed out that:

Universities have been operating in the context of substantial social, economic and political transformations after the collapse of the Soviet Union. These transformations have followed different paths in each country and today there exists great diversity in terms of where each nation stands in term of their human, economic, and political development, as measured by mainstream global indicators (p. 5).

Our analysis shows that Kazakhstan’s pathway to internationalization is different from that of other central Asian countries, who have much less resources, or even compared to China or Russia.

Until recently, authoritarian political regimes combined with the availability of resources allowed the country to become involved in diverse Higher Education internationalization policies.

Hanson and Sokhey (2020) have provided one of the most relevant assessments of Higher Education policies in countries with an outlook similar to that of Kazakhstan:

Authoritarian regimes should be willing to invest in Higher Education when the public sector plays a big role in the economy. A large public sector makes it both safe and desirable to invest in Higher Education. Although Higher Education could foster the kinds of social changes that contribute to modernization and the growth of a demanding middle class, this is less of a risk if many people are going to work in the state sector and are economically dependent on the state. Furthermore, a more educated population might be beneficial for improving the quality of the public sector and the goals of economic modernization.

In Kazakhstan, economic growth linked to oil and others sectors has allowed the government to invest in Higher Education and to promote internationalization at home and abroad. However, the stagnation of economic growth has translated into a sharp decrease in spending on Education and a stagnation of funding for Higher Education ( HANSON; SOKHEY, 2020 ). Most universities are now reliant on the private financing of Higher Education. Although some Kazakhs students have scholarships to study in public universities, most of them pay tuition fees.

As shown in Table 4 , government expenditure on Education decreased by 1% of GDP from 2012 to 2019 and funding for tertiary student decreased from 2345.1 to 2305 PPP$ (purchasing power parity with the US$) in the same period. Consequently, there is doubt about the state funding of ambitious internationalization policies in the future. In 2022, global economic crisis, the Ukraine war and political/security unrest which took place in Kazakhstan in January 2022 will also impact negatively government spending on Higher Education.

Table 4 Kazakhstan’s spending on Education and Higher Education

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government expenditure on Education as % of GDP | 3.9 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 3 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.9 |

| Initial government funding per tertiary student (PPP$) | - | 2345.1 | 2282.7 | 2632.6 | 2357.2 | 2079.5 | 1856.3 | 2305.6 |

Source: https://uis.unesco.org/en/country/kz (2021)

Crucially, internationalization, privatization and new models of governance of universities in Kazakhstan are typical of a post-Soviet transition, similar to processes observed elsewhere, as in Vietnam by Le Ha and Ngoc:

There are the historic public universities that are moving from a Franco-Soviet model, heavily inflected, of course, by Vietnamese pedagogical traditions, toward more Anglo-inspired modes of Higher Education. Added to the mix are a myriad of initiatives spearheaded by, for instance, Vietnamese philanthropists attempting to create liberal arts colleges in the image of the Ivy League, Western-based universities establishing branches in Vietnam as part of a broader project of developing global, academic empires, and educational entrepreneurs ( LE HA; NGOC, 2020 , p. xiii).

As the same authors observe, the final outcomes of such a transition have still not been stabilized:

What these colonial residues (both domestically and internationally) have meant for the academic study of Vietnam, including Higher Education, is that rather than assessing various aspects of Vietnam on its own terms, the country (like all of the Global South) has been juxtaposed to a Western standard, against which Vietnamese institutions and people inevitably fall short. Further, this benchmark is more idealized than real ( LE HA; NGOC, 2020 , p. xiv).

Bearing in mind these global discussions and debates regarding the transition towards a single conception of Higher Education based on an Anglo-Saxon benchmark, the meaning of university in Kazakhstan remains a disputed concept:

Historically, Kazakhstan’s universities have been accustomed to central control. It is too early to evaluate the success of the decentralization and the granting of institutional autonomy. There is a perceptible trend that the phenomenon of institutional autonomy is a case of cross-national transfer of educational practices. Interestingly, the policy documents and local media have referred to the concept of autonomy as the world’s best practice, though not much has been explored in terms of the relevance of the autonomy to Kazakhstan’s social context (SAGINTAYEVA; KURAKBAYEV, 2015, p. 208).

In this article, we have analyzed the process of internationalization of Higher Education in Kazakhstan. We can conclude that this outcome is mixed and that internationalization, while making some progress in the last thirty years (RIMANTAS et al ., 2021), is still incomplete and facing many challenges ( TIGHT, 2022 ). On the one hand, Kazakh universities are currently included in many international networks. Universities denote one component of nation-branding ( EGGELING, 2020 ). Many foreign universities or universities inspired by foreign models of teaching have settled in the country with some impact on research productivity ( KUZHABEKOVA; LEE, 2020 ). More international students are arriving from neighboring countries to carry out all or part of their studies in Kazakhstan.

Yet, on the other hand, privatization and commodification are advancing and inequalities in access to Higher Education are increasing ( BAYETOVA, 2019 ; CHANSELIANI et al. , 2020). A Kazakh model of governance and management of Higher Education is still lacking (DENGELBAEVA et al. , 2020). The example of English as a language of instruction illustrates the gap between the political and institutional will to internationalize and the actual situation on the ground.

8 Conclusion: the winding path towards internationalization in Kazakhstan

The internationalization of Higher Education creates new opportunities, encourages the acquisition of accessible knowledge, hastens the implementation of innovative work methods in Higher Education systems, improves mutual understanding between peoples and cultures, and contributes to the Education of a new generation for work in the global labor market.

As previously stated, the problem with implementing the internationalization of Education is the dearth of highly qualified personnel who are conversant in foreign languages. In this particular case, it concerns English (despite the fact that 13,600 students studied abroad under the Bolashak Programme), as well as centralized management to achieve effective results. To address this issue, it is necessary to decentralize Higher Education management, improve educational quality management systems and train multilingual specialists who are competitive and have a high specialty potential.

Our analysis shows the challenge of moving from the political and institutional will for internationalization and globalization to concrete implementation in teaching and research. Thus, a country undergoing a long transition, like Kazakhstan, requires proactive public policies to boost internationalization: inbound and outbound mobility of students and staff; increased use of foreign languages, in particular English; recruitment of foreign teaching staff; and participation in international research projects. Thanks to the income generated by the country’s natural resources, Kazakhstan was able to finance this international opening. Nevertheless, we observe that the internationalization process suffers from the inadequacy of university structures and a limitation in the capacity of university actors to project themselves internationally. Attracting international faculty, undergraduates and post-graduates allows the system to be improved upon, while taking into account the demands of the national and international labor market.

As previously stated, four types of expatriate research scientists visit Kazakhstan each year, and all were concerned about whether they could be expected to remain for a long-term perspective for the internationalization of Education. However, another issue that arose from time to time is that, if Kazakhstan continues to attract foreign lecturers in large numbers, this may result in the loss of local staff and the consequent brain drain and unemployment, which may have a negative impact on the nation’s future. Thus, when planning and implementing teacher and student academic mobility, an even ratio of foreign and local teaching staff at the rate of 50/50 must be considered as the ideal: if the university accepts ten foreign lecturers, it must dispatch ten domestics professors abroad for advanced training—and ensure they come back to the country.

A culture of internationalization will take some time to consolidate in Kazakhstan, as elsewhere in all the ex-Soviet countries. Future research should explore local obstacles to effective internationalization of Higher Education. It is also important to address inequities in accessing international Education for Kazak students. Probably, small and provincial universities lack real opportunities for internationalization.