Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Educar em Revista

Print version ISSN 0104-4060On-line version ISSN 1984-0411

Educ. Rev. vol.39 Curitiba 2023 Epub Sep 06, 2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-0411.87319

Dossier: Migratory processes and the history of education from a transnational perspective

Domenico Caon and his love for The Divine Comedy

*Universidade de Caxias do Sul, UCS, Caxias do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. E-mail: erela@ucs.br; E-mail: mcbernardi1@ucs.br

This work aims to discuss the life of Domenico Caon, an Italian immigrant who lived in Rio Grande do Sul, seeking to understand the intense relationship that he, as a reader, developed with the work The Divine Comedy, by Dante Alighieri. Domenico Caon was born in 1876 in the province of Padua, Italy, and immigrated to Brazil at a young age with his family, settling with his wife and children where today is located the municipality of Nova Roma do Sul. Domenico worked, among other activities, as a politician, merchant, artisan and farmer. This study was conceived from evidence of reading practices developed by the immigrant that deserve detailed attention, mainly in order to explain how his taste for reading arose and how Domenico related his reading experience with the social and its surroundings. The theoretical-methodological procedures applyed in this analysis are based on Cultural History and the History of Education; in particular, the concept of reading practices proposed by Batista and Galvão (2002) is used. Throughout this text, information from the immigrant’s genealogical research is presented, as well as evidence of how reading, especially the work The Divine Comedy, was present in his personal trajectory. From the investigation, it is concluded that reading practices developed by social actors, such as those of Domenico, allow to open investigative possibilities and examine the singularities that involve the historical processes of literacy outside the school environment.

Keywords: Reading practices; History of Education History (readers)

Este trabalho objetiva discutir a vida de Domenico Caon, imigrante italiano que viveu no Rio Grande do Sul, procurando compreender a intensa relação que ele, enquanto leitor, desenvolveu com a obra A Divina Comédia, de Dante Alighieri. Domenico Caon nasceu em 1876 na província de Pádua, Itália, e imigrou ao Brasil ainda jovem com a família, fixando residência com a esposa e os filhos onde hoje se localiza o município de Nova Roma do Sul. Domenico atuou, entre outras atividades, como político, comerciante, artesão e agricultor. Este estudo foi concebido a partir de evidências de práticas de leitura desenvolvidas pelo imigrante que merecem uma atenção detalhada, principalmente no sentido de explicar como surgiu o seu gosto pela leitura e como Domenico relacionou sua experiência de leitura com o social e o seu entorno. Os procedimentos teórico-metodológicos empregados nesta análise são fundamentados na História Cultural e da História da Educação; em especial, usa-se o conceito de práticas de leitura proposto por Batista e Galvão (2002). No decorrer deste texto, apresentam-se informações oriundas de pesquisa genealógica do imigrante, e indícios de como a leitura, em especial da obra A Divina Comédia, esteve presente em sua trajetória pessoal. Da investigação, conclui-se que práticas de leitura desenvolvidas por atores sociais, como as de Domenico, permitem abrir possibilidades investigativas e examinar as singularidades que envolvem os processos históricos de alfabetização fora do ambiente escolar.

Palavras-chave: Práticas de leitura; História da educação; História (leitores)

Opening remarks

The present work aims to discuss the life of Domenico1 Caon and his relations with the work The Divine Comedy, an epic poem written by Dante Alighieri. Domenico was an Italian immigrant born in 1876 in the province of Padua, Italy; he came to Brazil with his parents and siblings when he was 12. After marrying, he got domicile in Nova Treviso, a region of the current municipality of Nova Roma do Sul, at the time the second district of Antônio Prado, belonging to the Italian Colonial Region (RCI), in the northeast of the state of Rio Grande do Sul. This study is justified by the unique role that Domenico Caon assumed in the society in which he was inserted, and in his life trajectory, marked by reading practices, especially related to the work in question, which deserve a deepening of interest in Cultural History and History of Education.

The discussion proposed here is therefore based on authors from both areas. It is a genealogical operation (BARROS, 2007), based on Michel de Certeau conception of historiographical operation, which starts from the use of sources to understand a phenomenon, in this case involving family ties and the life of the investigated individual (BARROS, 2007). From his biography, some variables can be evidenced, such as socioeconomic characterization, professional performance, group, and community that are relevant to the understanding of literacy processes (MAGALHÃES, 1994).

The searches made correspond to the period from the birth of Domenico Caon until his death, respectively the years 1876 to 1949, and were made in civil archives of births, marriages, and deaths, consulting the regional press preserved in the Brazilian Digital Library, and in State and immigration collections.

When thinking of an immigrant-reader, evident characteristics of Domenico Caon, the idea of reading practices is introduced, presented by Batista and Galvão (2002), whose application allows us to understand not only the meaning of the act of reading in that context, but to focus it from an interdisciplinary dimension, with plural meanings, especially regarding the relations between text and subject. Thus, one can understand at least in part how Domenico made appropriations of the work and cultivated, throughout his life, the love for Dante’s poem. This perspective is also supported by microhistory2, in a discussion that changes the perspective of analysis (LEVI, 2017) reducing the scale of observation.

The work was divided into four parts, including this beginning, in which the theme, the choices, the theoretical bases used and the focus that this work gives to the object of study were explained. Next, the biography of Domenico from his birth to the time of the family’s immigration to Brazil is presented; later, his reading practices and the love he had for The Divine Comedy are discussed; and, finally, the final considerations are made, seeking to synthesize the objective of the work, the searches and the results achieved.

Who was Domenico Caon?3

Domenico Caon was born at 10:15 pm on October 25, 1876, at house number 53 in Via San Marco, municipality of Camposampiero, province of Padua (CAMPOSAMPIERO, 1876), and was the third child of Giuseppe Caon and Giovanna Bressan4 Zaniolo. In his birth record, it appears that the father did not take him to prove his birth due to the long distance, but that, despite this, the facts were verified for registration of the act. Also, it is interesting to note that Giuseppe Caon claimed not to know how to sign5.

Thinking a little about Domenico’s life to understand the cultures of reading and writing that were embedded in his family nucleus, the fact that his father subsequently declared himself illiterate6 at the birth of his children in the 1870s and 1880s indicates that, until at least his 40s, he probably could not read either.

From the family records 7, it is possible to establish that Giuseppe, Giovanna and their six children lived in the same house until they immigrated to Brazil, however it is interesting to note that Giuseppe was born in Busiago, Campo San Martino and Giovanna Bressan, in Fratte, a small village in the rural area of Santa Giustina in Colle. Despite being nearby locations, one of the reasons that may have led Giuseppe and Giovanna to move to Camposampiero8 is the displacement to work, mainly because the region is flat and with several properties and agricultural activities. From the birth records of the children, Giuseppe worked as a villic, that is, an employee of a rural property, which is also a particularity to think about the reading and writing processes and the education of children.

The first question that can be asked from this is how Domenico comes into contact with reading, since this is an activity that “is taught and learned” (BATISTA; GALVÃO, 2002). A study produced by Silva (2007, p. 205) states that the family is not “heir to a cultural capital [...] instituted and legitimized in literate societies”. It is therefore worth asking: “through what literacy practices might Domenico have developed the initialization in writing skills and actively participated in writing cultures? And then at what point does Domenico’s relationship with The Divine Comedy begin and intensify?

Certainly, both questions cannot be answered completely, but they serve to guide reflection on the processes. It is necessary to consider, in this sense, the individual in the space of socialization, to understand his initial formation, since there are relations between the practices of reading and writing and the processes of schooling (SILVA, 2007). It is known that Domenico left Italy at the age of 12, and therefore began his schooling in Camposampiero. Would he have had contact and access books and been encouraged to read at a young age? An important fact to consider is that, unlike much of other municipalities, Camposampiero already had upper-level school9 and railway lines being created in the 1870s (ATTI, 1874); the complete district had 21 and 28 lower public schools, respectively female and male, with an average of 2,800 students attending them (ATTI, 1874). It is therefore possible that Domenico frequented one of them, even though he lived inside the locality.

In this sense, it would be natural to think that his brothers also did so, but the evidence does not point to the same condition. Antonio10, a brother four years older than Domenico, reportedly could not sign11 before the beginning of the 20th century, when he was already in Brazil. The same happened to Pietro, firstborn son, and Maria, his younger sister (ANTÔNIO PRADO, 1908). It is worth asking, therefore, whether Domenico would be the “chosen” among children to attend school, considering several roles that could be assigned to children within families at that time.

It is interesting to note that, in addition to the love that Domenico would develop for The Divine Comedy, the literacy processes began, from the twentieth century, to be developed by other members of the house who until then did not know how to sign. This situation demonstrates that, in addition to schooling, other factors allowed the introduction12 of the family in reading and writing practices.

Briefly resuming the number of schools and students (49 and 2,800 respectively), it is worth emphasizing how important they are for the end of the 19th century. Camposampiero belongs to the province of Padua, which is home to one of the oldest European universities. The University of Padua (UNIPD) was founded in 1222, that is, when Domenico Caon began his schooling, it was close to 660 years of history. The institution is born as a splinter group of the University of Bologna, which is relevant since it does not arise by concession of the emperor or the pope. This represented freedom to learn and teach, to think and write without much interference from the established powers of that time.

It is noteworthy that the University is in the province where Domenico Caon started schooling, which perhaps encouraged him by the presence of knowledge and circulating knowledge, through teachers trained there. These are hypotheses to be considered in his journey as a reader of The Divine Comedy.

Immigration and the Signs of Readings in Domenico’s Life Trajectory in Brazil

It is known today “that the emigration movement has its roots in the process of the implantation of capitalism in Europe. From this perspective, overpopulation, pauperism, unemployment, low wages, and misery come to be seen as part of the phenomenon, whose essence lies in the analysis of the world expansion of capitalist relations of production” (IOTTI, 2001, p. 27, translated). Research indicates, in this sense, that at least 1/3 of the Italian population emigrated in the same period as Domenico Caon and his family.

A diplomatic record13 made by Edoardo Pantano (1904, p. 18, translated) explains that “[...] in 1901, the number of Italians residing abroad was about three and a half million [...], but probably this number is lower than reality, having been taken from approximate calculations or official censuses”. From the year 1875, on the upper slope of the northeast of the province of São Pedro do Rio Grande do Sul14, the establishment of immigrants began with the creation of colonies that today make up more than 50 municipalities of Serra Gaúcha, the RCI.

In an interview with a regional newspaper, Domenico stated that the date of emigration of his family was January 14, 1889, and that they had landed in Porto Alegre on the last day of Carnival; then, until São Sebastião do Caí, the trip was made in a smaller steam, and by cartor or15 by foot, they headed to Campo dos Bugres and after a month to the Linha Barra, near the Das Antas River, where Giuseppe bought land number 2 (O PIONEIRO, 1949a). In fact, based on the records, the family left Genoa with the steamship Chateau Yquem on the day and month mentioned, but in 1888, remaining only one day in Ilha das Flores, an inn for immigrants, and leaving for Porto Alegre on February 5 (ARQUIVO NACIONAL, 1888). This last date matches the account provided by Domenico when explaining that he arrived at the Carnival, that year celebrated on February 14.

It is interesting to question how Domenico experienced and memorized this stage of his trajectory, and how the readings he may have already made would also be related to his way of seeing the world. In this sense, what would be his opinion on immigration, being himself someone who left his homeland? Domenico responds to this in a certain way, mentioning excerpts from a poem, in a kind of chronicle written to the same newspaper to which he gave an interview that year. This game with literature shows the parallel between him and the text, since it refers directly to his own experience:

[...] As the poet said: «E quando reduti, ai patri lari, giocondi e liberi sarete un di, e, lá trai l giubilo dei vostri cari, non siate imemori di chi mori... Italy and Brazil, Heart and Soul - Precisely, on the 20th of this month, I complete another anniversary of arrival, to Campo dei Bulgheri, time of the Empire 1899, we kids in baskets, weight controlled, in a packhorse, and our late mom pulled the animal, walking, with dear dad and siblings, all in Eternity. I remember well the labors, the sacrifices, that our always living predecessors faced, continuing to travel, to Nova Padua, in a closed backcountry, being there animals, even ferocious, that frightened everyone, but the faith in God and the persevering works of the parents triumphed, although suffering resignedly, we were always well, and to thank everyone, we continue with joy, singing warmly Grace to God, long live Brazil! [...] Sincerely, Domingos, Tereza and Caon family. (O PIONEIRO, 1949b, p. 1, translated).

From the excerpt, it is possible to see some of the meanings and representations that Domenico attributed to this period of his life, showing a social reality marked by the faith of immigrants, by dedication to work, by the search for identity ties in common with others, and by bravery and heroism, characteristics also present in the discourses of other Italian immigrants in the region.

Domenico married Teresa Fabris, and tells this part of his biography in an interview: “My name is Domingos Caon. I’m married to Mrs. Tereza Fabbris Caon. Both born in Padua, Italy. We’ve come to meet here. And we got married in Nova Trento, today, Flores da Cunha, on February 22, 1897. [...] Nineteen children were born, fourteen of whom are still alive. I don’t know the right number of the grandchildren, but it goes beyond 70.” (O PIONEIRO, 1949a, p. 8, translated). Shortly after their marriage, the couple moved to Nova Roma, where they settled on lots Nos. 42 and 44, granted on March 12 and 19, 1904 from Linha Blessmann in Nova Treviso16 (ARQUIVO, 19--).

From his involvement with the community, it is possible to find reports in newspapers referring to him as “citizen of the most well-liked of that region” (O PIONEIRO, 1949b, p. 1, translated). Throughout his life in the locality of Nova Treviso, Domenico developed several activities: he owned a commercial house, set up a pottery and a ceramic and crockery factory, was a leather artisan, winegrower, imported the silkworm, exported wood, was a cattle rancher, a tropeiro, a trucker. He also joined the Republican Party17 and later twice became subintendent of Nova Roma (COSTA, 2007).

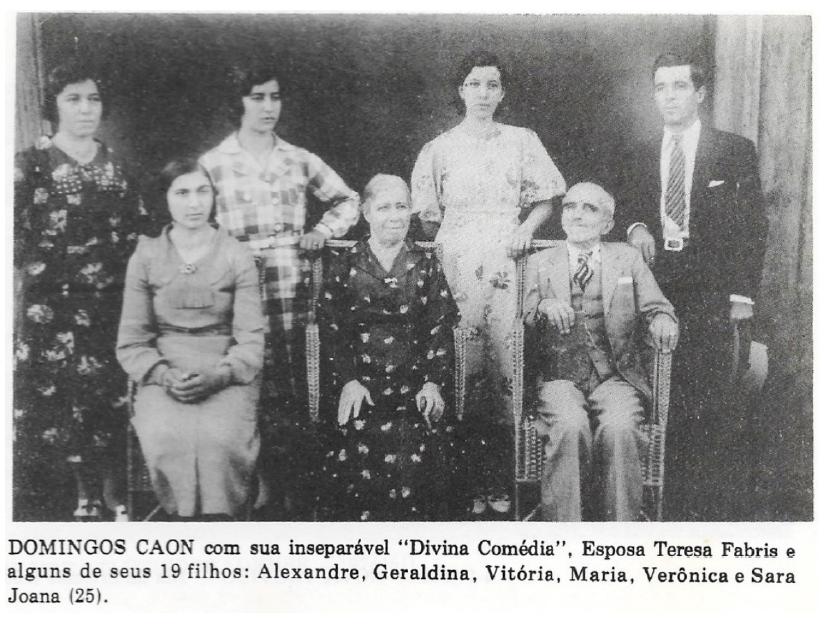

Domenico and Teresa had the following children18: Jocondo, Olinda, Cristiano, Armindo, Urbano Eliseu, Elvira, Emma Sofia, Dante Leon, Alexandrino, Jordão Bruno, Catulino Principe, Sara Joana, Veronica Amelia, Geraldina Vitoria (NOVA ROMA, 1949). Barbosa (1980) exhibits a photograph of Domenico’s family, which can be seen below:

In the photograph, dated approximately 1940, it is possible to see, in addition to part of the family, Domenico sitting at the front, with in his hands “his inseparable ‘Divine Comedy’”, as Barbosa said (1980, p. 281, translated). In fact, there are clear indications that Domenico was followed by the Dantesque poem, materially, as in the photo, and through his speeches. By the way, says the newspaper that visited him: “we must emphasize that he knows Dante by heart, and is a true lover of the things of literature” (O PIONEIRO, 1949a, p. 8, translated).

This relationship of Domenico with literature, and the predilection he had for Dante Alighieri’s text, finds more reasons than what can be revealed from the records. It is valid, however, to consider the characteristics of the work as a way of analyzing the corpus (BATISTA; GALVÃO, 2002) and then think of it in association with Domenico’s biography.

The Divine Comedy was written between 1304 and 1321, by Dante Alighieri, and “chronicles his own journey through the three realms of eternity: Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. He makes this journey by the grace of his late beloved Beatriz, who summons him to travel the kingdom beyond the grave so that Dante can save himself from his doom, rediscovering his true path” (VILLELA, 2010, p. 10, translated). Because it is a complex work that portrays human experiences (VILLELA, 2010), it is difficult to point out one or another particularity only that leads to its esteem by Domenico or by any other reader. However, it is possible to state with certainty that there was a production of meaning from this appropriation, and that his way of seeing the world was influenced by his being immersed in the content and reflected in his own trajectory and perhaps in that of the other individuals of Domenico’s life.

About this expansion of the text, and the reach it assumes from Domenico and in the context in which it is inserted, there is a statement by Franklin Cunha, a local memorialist. A child at the time of the facts, Franklin recalls that

“on the empty and cold nights of Antônio Prado, when Domingos Caon took over the city hall, he would climb on a bench in the deserted square and read some excerpts from The Divine Comedy, by Dante Alighieri, to four or five kids who understood little or nothing, but some excerpts he would translate to us and others he would tell us that he would not read because they were very strong scenes for children... Caon was a creative genius” (CHAVES, 2021, p. 32, translated).

Thinking about this account, the censored excerpts from Domenico’s narration could be references to hell or libidinous excerpts present in the work. Omitting is, in this case, a way of reading; it is the choice of what is acceptable to a given interlocutor. Could it be, then, that in the translation itself, there was an adaptation of Domenico for the others? Probably. And the appropriation of the work by him, in the theme, in the dramas of existence, in the manifestations between good and evil to those who received it aloud, as children, but not only, shows the complexity and potency of this relationship, and makes it possible to glimpse processes that took place there.

It can be considered that his intense relationship with literature, hypothetically distant from the cultures of the group to which Domenico belonged, as well as the permanence of evidence of his readings today, are due to the fact that Domenico was a public figure. Otherwise, it may also be thought that his case was only an exception, or that both factors played an important role in these phenomena. This, however, does not explain how Domenico became a reader, but evidence in this regard can be sought in different spaces.

Analyzing again his family nucleus, his father, who in Italy declared himself illiterate, began in Brazil to sign the documents of his children19, as does his brother Antonio between 1898 and 1903. Silva (2007) speaks of the family as the main space for acquiring reading and writing practices, and therefore, perhaps Domenico has developed his skills with the help of his parents and siblings. It is not improbable, however, that he influenced the other members of the family because of his love for reading.

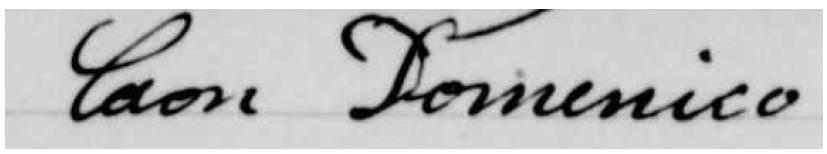

With regard to writing, below it is possible to check the signature of Domenico in the birth record of one of his children:

SOURCE: certificate of birth of Jocondo, Jan. 18. 1898, Antônio Prado.

FIGURE 2 Signature of Domenico Caon in 1898

When analyzed based on the problematizations and signature scales proposed by Magalhães (1994, p. 317-319), the signature shows a handwriting located between level 4 and 5 in which all letters are correctly drawn, at an almost individualized and conducted level of trace and rhythm. In 1898, Domenico showed a signature with marks of schooling, evident in the calligraphy. More than just a rudimentary signature, it indicates, more than a decade after the end of his period of formal instruction, that he possibly used writing in everyday life and that this writing remained over the following decades.

Regarding the appropriation and resuming his biography, one of his sons was named Dante Leone, possibly in honor of the Florentine writer and his work. The same can be said of the choice of the name of a daughter, who died a small girl, and was called Beatriz, in a probable allusion to Dante’s beloved. And what about Jordão Bruno, perhaps thinking of Giordano Bruno? How much did Domenico immerse himself in literature to bring it to his and his children’s life trajectories?

From the indications of his daily life due to the love he had for the work, it is not surprising that he built a granite monument approximately 3 meters high in honor of Dante Alighieri (FOLHA DE HOJE, 1994), located in Nova Treviso. It “still exists, although damaged by a bomb, thrown by criminal hands”, as Costa (2007, p. 36, translated) reports, who also states that “On the pedestal of the statue we read this verse of the poet himself: ‘Onorate l’Altissimo poeta’”. This shows what the work symbolized for Domenico, who, moreover, even wanted to change the name of the locality from Nova Treviso to Dante Alighieri (COSTA, 2007).

To those who had contact with him, Domenico “did not make a visit or meeting or receive interested parties, without, in the middle of the conversation, opening a beautiful copy of the Divine Comedy and reading it” (FOLHA DE HOJE, 1994, p. 1, translated). Because of him, people had contact with literature, developed or not their own reading and writing practices. As an example of this, many of their children ended up exercising teaching professions (COSTA, 2007).

Domenico applied for Brazilian naturalization between 1939 and 1940 when he had 14 years of municipal public service (SIAN, 1940) and died in Nova Roma on December 27, 1949, of natural causes and without medical assistance at the age of 76. The newspaper of the region reported his death explaining that “With much trepidation the population of Antonio Prado became aware of the death of the elder Domingos Caon, one of the pioneers, old pioneer, who with his sweat and effort, contributed to the enrichment of the municipality and our homeland. [...]” (O PIONEIRO, 1949c, translated).

Investigating Domenico’s life path associated with the traces of the readings, especially the references he made to Dante’s work, is the source of many questions, some of which cannot be fully answered, but which still point to directions for understanding the relation between his life, his reading and writing practices and the effects they had within the community. Batista and Galvão state, in this sense, that

The distribution of a cultural product does not reveal everything; on the contrary, its appropriation, its use and its consumption are as important for the realization of a history of reading as its circulation, in several cases, in fact, much more fluid than one thinks, the relations between objects of reading and social groups are much more complex (BATISTA; GALVÃO, 2002, p. 19, translated).

The life of Domenico Caon instigates to deepen the particularities of his trajectory, in the love he had for The Divine Comedy and in the family nucleus that was involved in the processes of acquiring writing. The use and appropriation that Domenico made allows us to understand the complexity of these processes for him and the relationships he established with this, and other texts read. They are paths that tell an individual and local history, but they are also part of a history of education, culture and reading, at the limits of space and time investigated and beyond them.

Final Considerations

Domenico Caon showed traces of reading cultures in the community in which he was inserted. They are especially recognized in the subjects of their family, who seem to have gone through a literacy process not limited to formal instruction. His wife20, for example, perhaps developed reading practices precisely because she was in contact with Domenico. It is not unlikely that Antonio, his brother, hearing Domenico talk about The Divine Comedy, became interested in the books and then learned to sign and then read. His father Giuseppe, who at age 50 no longer claims to be unaware of reading and writing, may have gone through a similar process. Antônio and Giuseppe, by the way, were inserted in the literate world even when they were reportedly unable to read or write, and this shows that the definition of being or not being literate is not restricted to technical processes.

The evidence of Domenico’s life and reading practices shows the sociability that often revolves around orality and enables the insertion of new individuals in these same practices. The Divine Comedy seems to have been only one of the works that marked him and came to this analysis, since his relatives informed that he had a large library. Domenico marked his trajectory by his taste for reading, which accompanies the economic transformations, industrialization movements and the development of schooling experienced by him in youth, and which was probably encouraged, as a habit, by other readers with whom he was in contact, in a movement that repeats itself from Domenico to the others, such as his father and brother.

This work aimed to discuss Domenico Caon when seeking to understand the love that he, as an Italian immigrant established in Brazil, developed for The Divine Comedy, work of Dante Alighieri. With genealogical research, it was possible to highlight elements of his biography, relationships with his family and with the community in which he was inserted, seeking to comprehend how the reading practices developed by him were linked to his life trajectory.

Domenico’s path was marked by traces of the readings (and writings) developed by him. In the most diverse ways, it was possible to see evidence that these practices were present in his daily life, from the choice of children’s names, through people’s reports, newspaper chronicles, to the construction of the monument in honor of Dante Alighieri. The life of Domenico makes us think of so many other “Domenicos” whose actions regarding education have been erased by time.

From the investigation, it is evident that, despite the mobilization of only one individual and their family nucleus, in the context of Italian immigration in Brazil, some reading and writing practices may have been developed outside the school environment and the schooling period. This serves as a warning for researchers to examine informal evidence of schooling and use microhistory, as in this work, to corroborate with research in the various possible perspectives linked to the theme.

REFERENCES

ANTÔNIO PRADO (RS). Registro civil de Antônio Prado. Casamento de Marcello Bortolotti e Maria Caon. Disponível em: https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/263342?availability=Family%20History%20Library . Acesso em: 06 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

ARQUIVO Público do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul. Cartório de Registro Civil de Caxias do Sul. Habilitação de matrimônio de Domingos Caon e Teresa Fabris. 1897. Disponível em: http://antigo.apers.rs.gov.br/AAP/corpo.php?cmp_pedido=consultaDocumento&nro_int_documento=70960 . Acesso em: 11 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

ARQUIVO Público do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul. Livro Colônia Antônio Prado, Linha Blessmann. 19--. Disponível em: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-D1J9-S2Q?i=2 . Acesso em: 12 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

ARQUIVO NACIONAL. Registro da Hospedaria Ilha das Flores. 4 de fevereiro de 1888, p. 105, número de ordem: 4236-4242. [ Links ]

ATTI del Consiglio Provinciale di Padova. Sessioni straordinarie ed ordinaria. Anno 1873. Padova: Tipografia Prov. E Preff. L. Penada, 1874. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, Fidélis Dalcin. Antônio Prado e sua história. Porto Alegre: EST, 1980. [ Links ]

BARROS, José D’Assunção. A operação genealógica: a produção de memória e os Livros de Linhagens medievais portugueses. Mouseion, v. 1, n. 2, p. 142-167, 2007, Disponível em: https://arquivos.ufrrj.br/arquivos/20201800047e21230477710504e7e3425/A_Operacao_Genealogica._Mouseion_2007.pdf. Acesso em: 25 abr. 2023. [ Links ]

BATISTA, Antônio Augusto Gomes; GALVÃO, Ana Maria de Oliveira. Práticas de leitura, impressos, letramentos: uma introdução. In: BATISTA, Antônio Augusto Gomes; GALVÃO, Ana Maria de Oliveira (Orgs.). Leitura: práticas, impressos, letramentos. 2 ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2002. p. 11-45. [ Links ]

CAMPOSAMPIERO (PD). Registri dello stato civile di Camposampiero. Originali nell’ Archivio Tribunale di Padova. Certidão de nascimento de Domenico Caon. Registro em: 29 out. 1876. Disponível em: https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/738778?availability=Family%20History%20Library . Acesso em: 06 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

CHAVES, Ricardo. O “divino” Domingos Caon. Zero Hora, Porto Alegre, 27 abr. 2021. [ Links ]

COSTA, Rovílio. Povoadores de Antônio Prado. Porto Alegre: EST, 2007. [ Links ]

FOLHA DE HOJE: o diário de Caxias. Caxias e sua relação com o escritor italiano. Ano V, n. 1503, p. 1, 14 set. 1994. [ Links ]

FLORES DA CUNHA (RS). Registro civil de Flores da Cunha. Certidão de casamento de Domingos Caon e Teresa Fabris. Disponível em: https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/1209926?availability=Family%20History%20Library . Acesso em: 08 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

IOTTI, Luiza Horn. O olhar do poder: a imigração italiana no Rio Grande do Sul, de 1875 a 1914, através dos relatórios consulares. 2. ed. Caxias do Sul, RS: EDUCS, 2001. [ Links ]

LEVI, Giovanni. O pequeno, o grande e o pequeno. Entrevista com Giovanni Levi. Revista Brasileira de História, v. 37, n.74, p. 157-182, 2017. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/rbh/a/FyVZm5Jzs9vX3JJTHcMXLQQ/?lang=pt . Acesso em 07 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

MAGALHÃES, Justino Pereira de. Ler e escrever no mundo rural do antigo regime: um contributo para a história da alfabetização e da escolarização em Portugal. Braga, Portugal: Tilgráfica, 1994. [ Links ]

NOVA ROMA (RS). Registro civil de Nova Roma. Certidão de óbito de Domingos Caon. Registro em: 27 dez. 1949. Disponível em: https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/1201186?availability=Family%20History%20Library . Acesso em: 07 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

O PIONEIRO. Galeria dos pioneiros: Domingos Caon, p. 8, 17 out. 1949a. [ Links ]

O PIONEIRO. Em marcha a ideia do monumento. Expressiva carta do sr. Domingos Caon, velho morador do município de Antônio Prado. Ano 1, n. 19, p. 1, 12 mar. 1949b. [ Links ]

O PIONEIRO. Notícias de Antônio Prado. 31 dez. 1949c, p. 2. [ Links ]

PANTANO, Edoardo. Condizioni presenti dell’emigrazione italiana (Parte I). BE. p. 7-39, n. 11, 1904. In: HERÉDIA, Vania Beatriz Merlotti; ROMANATO, Gianpaolo. Fontes Diplomáticas: Documentos da imigração italiana no Rio Grande do Sul. Tomo III. 2017, p. 386-418. Disponível em: https://www.ucs.br/educs . Acesso em: 04 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

SIAN, Sistema de informações do Arquivo Nacional. Processo de Naturalização de Domingos Caon. BR RJANRIO A9.0.PNE.47425. Disponível em: http://imagem.sian.an.gov.br/acervo/derivadas/BR_RJANRIO_A9/0/PNE/47425/BR_RJANRIO_A9_0_PNE_47425_d0001de0001.pdf . Acesso em: 14 fev. 2023. [ Links ]

SILVA, Fabiana Cristina da. Práticas de leitura e escrita em famílias negras de meios populares (Pernambuco, 1950-1970). In: GALVÃO, Ana Maria de Oliveira et al. História da cultura escrita: séculos XIX e XX. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2007. p. 205-238. [ Links ]

VILLELA, Felipe Stiebler Leite. O caminho da nossa vida, uma aproximação entre Ser e tempo e Divina Comédia. Dissertação (Mestrado em Filosofia), 2010. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, 2010. Disponível em: https://sapientia.pucsp.br/bitstream/handle/11835/1/Felipe%20Stiebler%20Leite%20Villela.pdf . Acesso em: 06 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

4Known as Zaniolo. It is worth noting that, in Brazil, Giovanna always appears as Zaniolo in the records.

5As original: “Letto il presente atto a tutti gli intervenuti l ‘hanno questi meso sottoscritto meno il dichiarante perché illetterato come asserisce”. Translated: “Read this act to all those present, all signed it, except the declarant for being illiterate as he claims”. As for Domenico’s mother, it seems that she remains, even in Brazil, without signing the records. See Archive (1897).

6It was decided not to deepen the concept of illiteracy. For understanding, in this study, the term illiterate refers only to the absence of the ability to sign.

8Municipality located in the province of Padua, in Veneto, northern Italy. At the time, the town had about 3,000 inhabitants.

12Despite the use of the term “introduction”, it is understood, as well as in Galvão’s studies, that it is impossible to be outside the written world.

16As already explained, it belonged to Nova Roma, at the time the second district of Antônio Prado/RS.

18Some children passed away after birth and others at a few years of age or in their youth. The children listed were alive in 1940.

Received: August 01, 2022; Accepted: March 03, 2023

text in

text in