Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Educação e Pesquisa

Print version ISSN 1517-9702On-line version ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.50 São Paulo 2024 Epub June 10, 2024

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202450274381por

ARTICLES

Emergence of group schools and production, through differentiation, of isolated schools in the state of Espírito Santo (1908-1916) * 1

Maria Anna Xavier Serra Carneiro de Novaes holds a Master of Science in Education from the Federal University of Espírito Santo (Ufes); she is a researcher at the Capixaba Center for Research in the History of Education (Nucaphe/Ufes).

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4456-744X

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4456-744X

Regina Helena Silva Simões holds a Ph.D. in Education; she is a Professor in the Graduate Program in Education at the Federal University of Espírito Santo (PPGE/Ufes) and coordinator of the Capixaba Center for Research in the History of Education (Nucaphe/Ufes).

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7554-3152

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7554-3152

2-Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, ES, Brasil.

This article assesses the trajectory of isolated schools in Espírito Santo, in the context of opposition and competition with the model school, the projection, and the conditions for the effective functioning of the Gomes Cardim School Group, the first and for a long time the only school group in Espírito Santo. The period chosen (1908-1916) covers the period from the declaration of the inconvenience of the isolated schools in Vitória, capital city of the state of Espírito Santo, to the creation of an institution aimed at modeling the practice of teachers to work in those same schools. The documentary corpus worked on including letters, requests, reports, decrees, laws, official acts of the Brazilian Ministry of Education, photographs, and news articles. Through an indexical analysis of these sources, the text focuses on school spaces, teaching staff, and the organization of teaching in isolated schools in Espírito Santo. In general, it is understood that the generally negative evaluation attributed to isolated schools (Souza, 2016 ) coexisted with forced ambiguities, on the one hand, due to the fragility of the locally established school group, and on the other hand — despite the inconvenience decreed in 1908 — due to the indispensable role of isolated schools, to the point of their modeling in 1916. In the case of Espírito Santo, contrary to the discursively constructed binarism about the modes of schooling in the early twentieth century, the relationship between the school group and the isolated schools is understood as a conflict permeated by challenges and mutual borrowings, considering that the markers of differentiation established between the two mainly concern the legal prescriptions, the status, and the visibility granted to each institution.

Keywords History of Brazilian education; Espírito Santo; Elementary school; Isolated school; 20th century

Este artigo problematiza o percurso das escolas isoladas capixabas, considerando suas relações de oposição e concorrência perante a Escola Modelo, bem como a projeção e as condições de efetivo funcionamento do Grupo Escolar Gomes Cardim – o primeiro e durante um bom tempo único GE do Espírito Santo. O recorte temporal estabelecido, de 1908 a 1916, compreende o período decorrido desde a decretação da inconveniência das escolas isoladas em Vitória, capital do Espírito Santo, até a criação de uma instituição destinada à modelização da praticagem de professores para atuarem nessas mesmas escolas. O corpus documental trabalhado compreendeu: ofícios, requerimentos, relatórios, decretos, leis, atos oficiais da Secretaria de Instrução, fotografias e matérias jornalísticas. Por meio da análise indiciária dessas fontes, o texto focaliza espaços escolares, professorado e organização do ensino em escolas isoladas capixabas. Em linhas gerais, compreende-se que a avaliação negativa geralmente atribuída às escolas isoladas convivia com ambiguidades forçadas, por um lado, pela fragilidade do grupo escolar instituído localmente e, por outro – apesar da inconveniência decretada em 1908 –, pela atuação imprescindível de escolas isoladas, até o ponto da sua modelização em 1916. No caso do Espírito Santo, ao arrepio de binarismos construídos discursivamente acerca dos modos de escolarização no início do século passado, compreende-se a relação entre o grupo escolar e as escolas isoladas como um conflito permeado por desafios e empréstimos recíprocos, considerando-se que os marcadores da diferenciação estabelecida entre os dois dizem respeito, principalmente, às prescrições legais, ao status e à visibilidade conferida a cada instituição.

Palavras-chave História da educação brasileira; Espírito Santo; Escola primária; Escola isolada; Século XX

Introduction

At the beginning of the 20th century, the educational reform led by Carlos Alberto Gomes Cardim (1908-1909) established new guidelines for teacher training, standardization of instruction, and systematic organization of public schools in Espírito Santo (Simões, Salim, 2012 ). Some of the measures taken included the emphasis on the normal school and the model school as centers for the dissemination of the analytical method to be adopted in primary schools. This was followed by the reorganization of the normal school curriculum and the approval of the decree classifying primary schools into three categories: isolated, mixed, and night schools (Espírito Santo, 1908a ).

This decree is the first mention of the term isolated school in Espírito Santo legislation. Therefore, unlike the case of São Paulo, where the term appears after the implementation of the first school groups (Vidal, 2006 ), in Espírito Santo, the idea of the isolated school is initially contrasted with the model school, whose operation both inaugurated the model of the graded school and presupposed the future implementation of school groups.

The symbolic power of the differentiation between the school group and other educational institutions becomes clear in this way. In other words, the mere projection of the school group produced a different terminology and, consequently, an unfavorable condition for other primary schools: the classification also implied different teaching programs and the duration of the primary course. Finally, in September 1908, Gomes Cardim founded the first class, which was named after him.

In the context of the Cardim reform, the introduction of the school group would express the modernizing republican ideology underlying the public education reforms in Brazil, which is why, even before its implementation, it was decreed: “[…] it is not appropriate for isolated schools to continue operating in this capital, since education is provided in the model school, in the group, and in the evening schools ” (Espírito Santo, 1908b , p. 1, emphasis ours). This is the same decree whose article 1 abolished “[…] the 1st and 2nd male chairs and the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th mixed chairs” in the city of Vitória and dismissed “[…] the respective teachers who have not been used in the new organization of education, respecting the rights or advantages guaranteed to them by law” (Espírito Santo, 1908b , p. 1).

The question is: if in 1908 the intended goal was to eradicate the isolated schools in the capital, how can we explain, eight years later, the operation of “[…] an isolated school [attached to the model school] for the training of teachers destined to teach classes of this category”? (Espírito Santo, 1916 , p. 1). Based on this circumstance, the present study problematizes the production of isolated schools in Espírito Santo, from the decree of their inappropriateness in 1908 to the creation of a model isolated school in 1916. By doing so, it inserts itself into a broader movement of historiographical reinterpretation of the place occupied by school groups in the processes of schooling, driven mainly by the shift from homogenizing narratives produced from large centers to efforts to understand regional singularities in the expansion of public education in Brazil (Souza, 2019 ).

The documentary corpus used included: official letters, requests, reports, decrees, laws, official acts of the Secretariat of Education, photographs, and journalistic articles. Through the indicative analysis of these sources (Ginzburg, 1989 , 2002 ), an attempt was made to understand the trajectory of the isolated schools in Espírito Santo, considering their relationships of opposition and competition with the model school as well as the projection and conditions for the effective functioning of the Gomes Cardim School Group (GCSG), based on three analytical axes: school spaces, teaching staff, and organization of teaching.

School spaces: architecture of the possible

In the republican idealization, the sumptuous architecture designed for the school group reflected the social role ascribed to public education. In Espírito Santo, however, the GCSG initially occupied improvised facilities in a space attached to the Model School (Locatelli, 2012 ). It later moved to an adapted building that, “[…] despite the modifications made to it, does not meet the conditions of hygiene and comfort essential for an educational institution” (Espírito Santo, 1910c , p. 10). In the improvisation of the initial facilities, the low student attendance was attributed to two factors: the inconvenience of the class schedule (from 8 a.m. to 12 p.m.), which had to be compatible with the functioning of the normal school; and the proximity of the model school since both operated adjacent to the normal school (Espírito Santo, 1909b ).

In Espírito Santo, the propaganda palace of the Republican government “[…] was made of glass, reflecting the fragility of local public education policies” (Simões; Salim, 2012 , p. 100), built by a predominantly agricultural state driven by coffee monoculture, whose resources proved insufficient for the implementation of quality primary schools.

In the cities of Santa Leopoldina and São Mateus, for example, the buildings intended for the installation of school groups housed an isolated school “[…] because there were not enough students in these cities” (Espírito Santo, 1913b , p. 27). In the capital, the existence of numerous remote villages and low population density contributed to the maintenance of isolated schools. Under these circumstances, a month after the decree that aimed to eliminate them in the capital, a new law provided for the organization of education in: a) isolated schools for each sex, directed by a male teacher in male schools and by a female teacher in female schools; b) mixed isolated schools, directed by a female teacher; c) evening schools, for students over 12 years of age; d) consolidated schools; e) school groups; and f) model schools, attached to the normal school (Espírito Santo, 1908c ). According to the legal text:

Art. 13. In places where there are at least forty illiterate pupils, an isolated mixed school will be set up.

Art. 14. In cities where the density of population so requires, there shall be as many isolated schools for each sex as there are groups of forty-five pupils of school age.

Art. 15. Whenever there are more than forty illiterate pupils over the age of twelve in a city, an evening school will be set up. (Espírito Santo, 1908c , p. 1).

The expansion of isolated schools between 1908 and 1916 contrasts sharply with the timid numerical growth of school groups ( Table 1 ).

Table 1 - Number of elementary schools in Espírito Santo between 1908 and 1916

| 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1914 | 1916 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISOLATED SCHOOLS | 107 | 139 | 203 | 238 | 218 | 210 |

| SCHOOL GROUPS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| MODEL SCHOOLS | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

Source: Government messages sent to the Legislative Congress of Espírito Santo (1908–1916).

In 1910, the isolated schools in Vitória were located in the following districts: Vila Rubim, Jucutuquara, Queimado, Pitanga, Carapina, Goiabeiras, Ilha das Caieiras, Itaoibaia, and Jacuhy (Espírito Santo, 1910c ). This distribution was linked to the proximity to the urban perimeter, so that the isolated school of Argolas, located in a neighboring municipality 3 , was among the institutions of the capital in the requests sent to the Secretariat of Education and in the school attendance published daily in the Diário da Manhã , the official government newspaper, while those located in the districts of Queimado and Carapina, predominantly rural regions, did not appear in these documents 4 .

In other words, the determination of schools that belonged to the capital was based more on the social recognition of localities than on municipal boundaries. The state government’s investment in primary schools was linked, on the one hand, to the path of progress outlined by the Monteiro government, which favored the locations of interest to the state development plan, and, on the other, to political practices based on colonelism (local political bossism) and the power of rural oligarchies 5 .

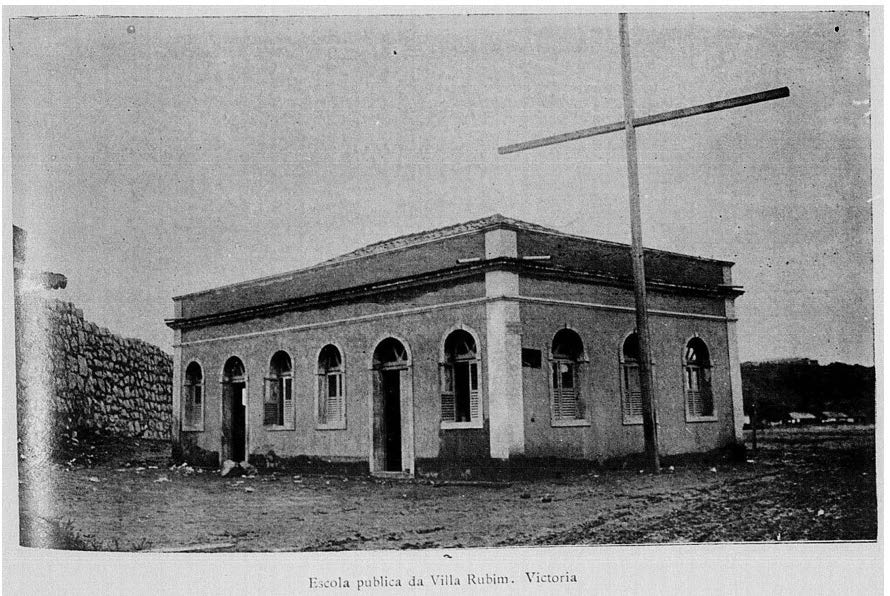

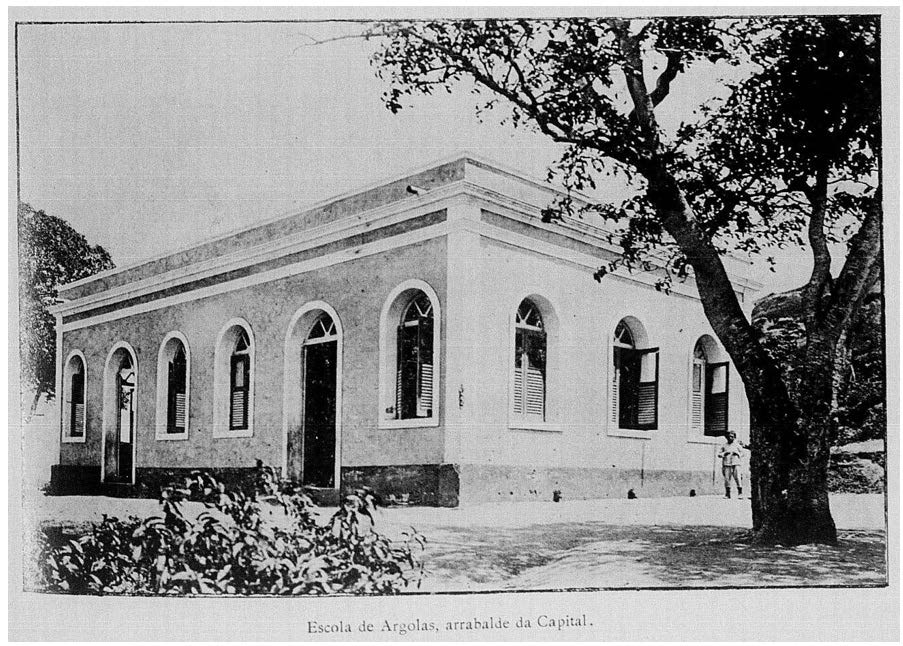

In this way, the investments made in various sectors reflect both an aesthetic attention to areas of higher social or commercial circulation, and a civilizing action that sought to discipline and regenerate the popular classes through education. The configuration of the school buildings in Vila Rubim and Argolas, for example, was linked to the urbanization plan, articulated around the works of structuring and equipping the port and the railway station. Although the planned expansion did not materialize for financial reasons, “[…] the port works were resumed in a very modest way, between Vila Rubim and the São Tiago complex ” (Siqueira; Vasconcelos, 2012 , p. 17, emphasis ours) 6 .

The development of Porto de Argolas also depended on the communication routes necessary for the flow of inland production. In 1907, the Southern Railway of Espírito Santo came under the control of the Leopoldina Railway (Siqueira; Vasconcelos, 2012 ), when the railway line, starting from Porto de Argolas, began to connect Vitória with different regions of the interior of Espírito Santo and Minas Gerais.

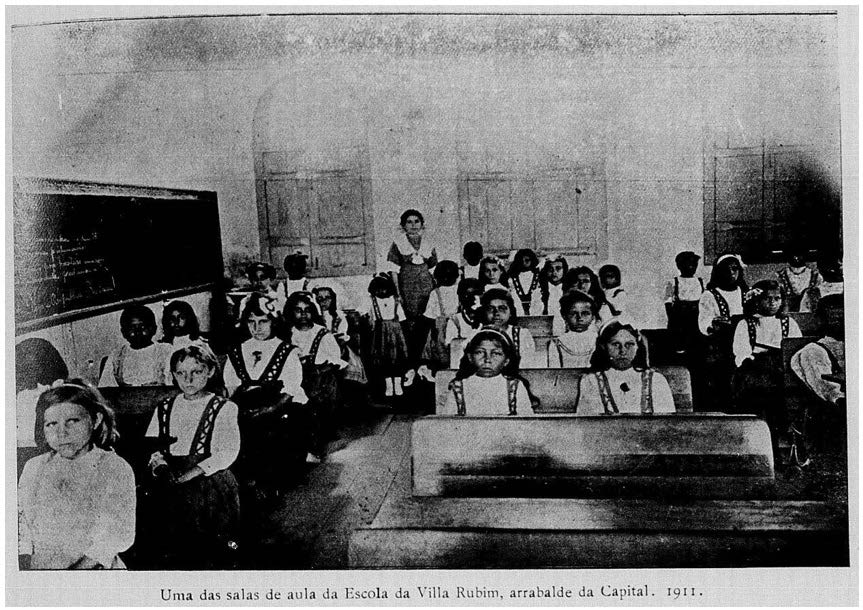

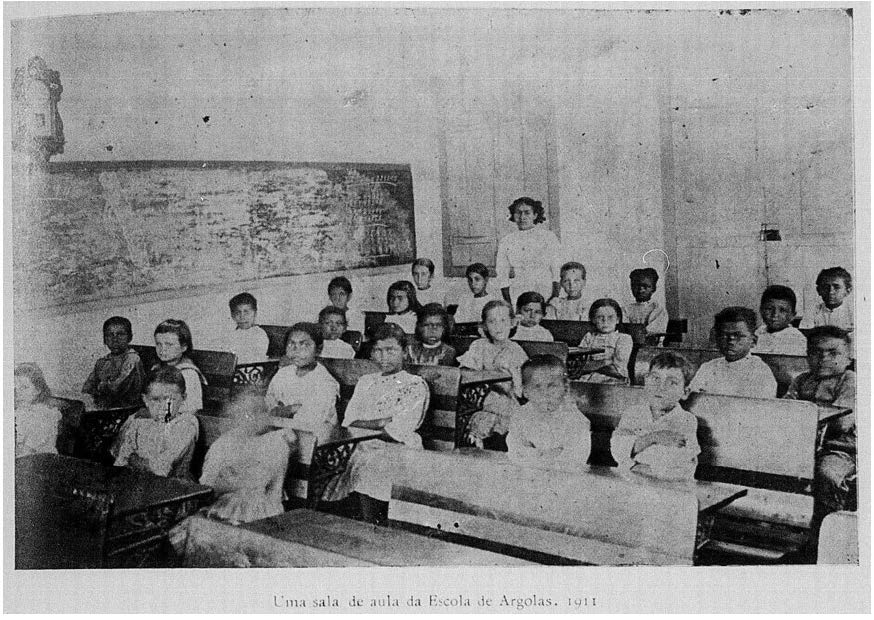

Following this logic of development, even before the allocation of a proper building for the operation of the GCSG, the schools in Vila Rubim ( Figure 1 ) and Porto de Argolas ( Figure 2 ) occupied buildings whose construction complied with “[…] all prophylactic regulations” and had “[…] furniture and materials necessary for houses of this type” (Espírito Santo, 1909b , p. 6).

As can be seen, these are similar spaces in terms of physical structure and furnishings, and they each house two isolated schools: both mixed in Porto de Argolas; one for boys and one for girls in Vila Rubim. It can be noted that the constructions followed the same standard, meeting the hygienic recommendations of the time, such as double-height ceilings and doors and windows designed to ensure ventilation, light and health.

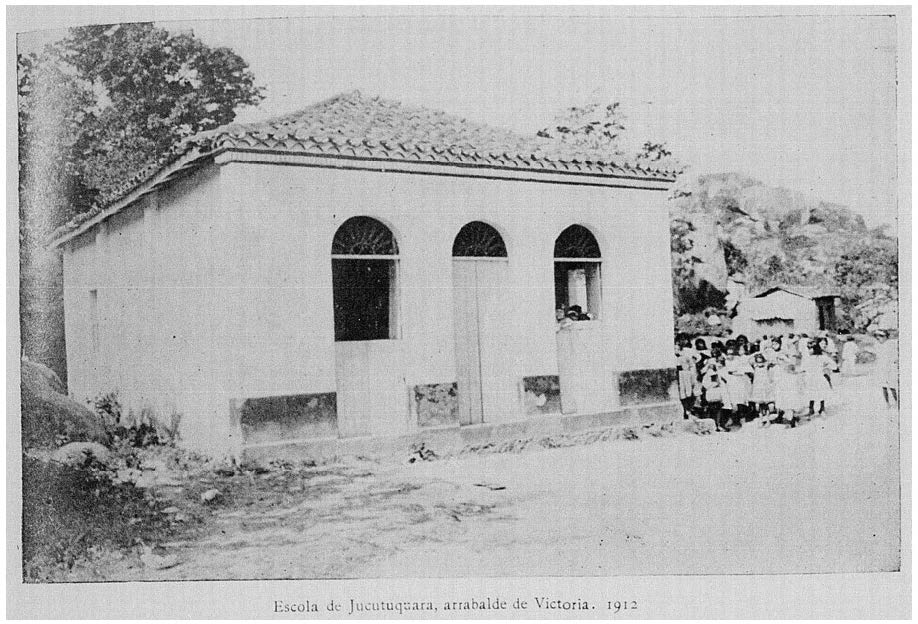

The school in Jucutuquara ( Figure 3 ), on the other hand, illustrates the operating conditions of most of the schools in Vitória, which occupied rented houses (in some cases the homes of the teachers), considering that, despite the modernizing impulses, architecturally the city “[…] retained much of its residential complex with colonial structure” (Rostoldo, 2008 , p. 115).

Compared to the previously mentioned schools, the photograph of the school in Jucutuquara shows a reduction in the number of doors and windows, raising the question of how it would accommodate the fifteen double desks distributed by the Secretariat of Education, and especially the 25 female students enrolled in the institution (Espírito Santo, 1910c ).

The offer to rent for educational purposes mainly came from popular initiative, with the state indicating the necessary adaptations, usually more focused on sanitation than on organizing the school space. This was the case with a resident who had given the teacher Margarida Neves the room in his house, “[…] the only one in a sufficiently large location” in the locality of Santo Antônio, for her to operate “[…] the school under her charge.” He proposed to expand the space given so that it could “[…] accommodate 96 students of both sexes; that is, 75 enrolled and 21 who eagerly awaited the very appropriate change authorized by the Government.” To solve the problem, he intended to “[…] demolish all the central walls of his residence, leaving it as a single hall which would perfectly accommodate 100 students,” and also to “[…] divide the said halls into two, in case two schools were needed.” He also proposed “[…] two compartments next to his house; one, where he would keep a kitchen, and another a special room for the teachers to rest during break times.” Finally, he would install “[…] water, light, and sewage, being able [illegible] a faucet on the balcony of the same house that now houses the schools, duly cemented and covered balconies, which are perfectly suited for school maneuvers” (Espírito Santo, 1912 , n/p).

At what cost (not only financial) were the proposed adjustments made for the proper structural, hygienic and pedagogical functioning of the school institution? For example, the gathering of many students under the direction of a single teacher implied inadequate working and learning conditions, especially when the educational regulations stipulated the adoption of the intuitive method in all primary schools in the state. The problem persisted for a long time: only in 1915 did the region receive another mixed school, which was closed at the end of the same year (Espírito Santo, 1915 ).

According to the primary education regulations, the school furniture would be “[…] designed to facilitate the inspection and individual responsibility of the student as well as to meet the requirements of hygienic precepts.” To the teacher, each class or school would allocate “[…] a desk, a chair, and a cabinet,” items that were nonexistent in the inventory of this institution (Espírito Santo, 1909a , p. 1).

In the urban schools of Vitória, the furniture and teaching materials varied little. However, the model school stood out from the rest ( Table 2 ). Thus, the result of dividing the objects acquired by the number of classes in the GCSG differed minimally from the quantity of material distributed by the urban isolated institutions, leading us to believe that the model school absorbed the scarce resources allocated to primary education, leaving the school groups with a symbolism that was primarily discursive.

Table 2 - List of furniture and teaching objects acquired between 1908 and 1912

| Model school | GCSG | Isolated school of Jucutuquara | Isolated school of Vila Rubim |

|---|---|---|---|

| - 212 individual desks - 8 desks for teachers - 8 clocks - 191 chairs - 7 maps - 5 counters - 7 hoists - 4 Parker’s maps - 3 spittoons - 2 bookcases - 1 desk - 1 typewriter - 1 knick-knack holder - 1 swivel chair |

- 175 double desks - 9 tables - 9 clocks - 10 chairs - 8 maps - 2 counters - 4 hoists - 4 Parker’s cards |

- 30 double desks - 2 tables - 1 clock - 3 chairs - 2 maps - 1 counter - 2 hoists |

- 40 double desks - 2 tables - 2 clocks - 3 chairs - 2 maps - 1 counter |

Source: Espírito Santo ( 1913a ).

Another significant element in the relationship of the teaching materials destined to public educational institutions are the Parker’s maps 7 , since although the curriculum of the isolated schools included calculations in Parker’s maps (content of the 1st year), the material only reached the model school and the school group. Although it is the only item that differs in the list of objects acquired for the school group and for the urban schools of Vitória, its absence provides evidence that the investment in the intuitive method would be greater in the graduated schools.

The school of Goiabeiras, belonging to the district of Carapina, was the least favored in the distribution of furniture and school supplies, noting the absence of maps and counters and the use of benches instead of double desks (Espírito Santo, 1910c ). On a visit to the state’s schools, Cardim expressed his displeasure at having found “[…] kerosene boxes replacing desks, and rooms without air and light, infected, used for public instruction” (Espírito Santo, 1909b , p. 9). He also reports: “At the school of Campinho de Jacuhy, since the teacher was not there, I had difficulty knowing which room was intended for the class, because I found some repulsive little rooms without the slightest hint of a school!” (Espírito Santo, 1909b , p. 9).

In letters and requests to the Secretariat of Instruction, inspectors also reported on students who, “[…] due to their extreme poverty, are unable to attend school classes because they lack decent clothing, books, paper, pens, ink, pencils, etc., which are required by the State’s Public Education Regulations ” (Espírito Santo, 1911 , n/p, emphasis ours). Even with the creation of the School Fund in 1915, the lack of family resources hindered access to and retention in school. Petitions also point to the absence or inadequate functioning of educational institutions. Overall, parents or guardians requested the construction of buildings, the release of teachers, and the sending of school supplies.

In 1909, a group of parents petitioned the President of the State for the continuation of the school on Ilha das Caieiras so that their children, “[…] numbering thirty-seven, of whom about twenty-five are already enrolled,” could attend. According to the petitioners, the low attendance—the reason for which the school was to be abolished—was due to the irregular functioning of the institution, since the said school “[…] was founded on the seventeenth of October, on the eve of the holidays” (Espírito Santo, 1909c , n/p).

In 1915, the inhabitants of Goiabeiras lamented “[…] the lack of a public school to guarantee the flourishing literary future of these young people, whose number exceeds ninety.” They thus requested the dispatch of a teacher “[…] to save these unfortunates who live in dense darkness and beg for education” as well as the availability of a suitable house for the operation of the school (Abaixo-Assinado, 1915 apud Locatelli, 2012 , p. 146).

Outside the focus of documents and images produced from the perspective of public power, documents like these point to neglected, abolished, or strongly demanded schools, revealing the struggles and expectations of heterogeneous and unequal social groups that converged in the interest and demand for public education. Alongside the demands for schoolrooms, the figure of the teacher stands out, with the immodest expectation of rescuing from darkness unhappy children thirsty for schooling. Who was this teacher to whom was attributed the salvation of children deprived of the light of knowledge, in accordance with an Enlightenment ideal circulating at the beginning of the last century? What was the practice of public teaching in the isolated schools of the time?

Teachers from isolated schools in Espírito Santo: between idealization and reality

Most of the teaching staff in each school consisted of teachers licensed by public examination (Salim, Manso, 2016 ), although normal school graduates predominated in urban areas 8 , as was the case in isolated schools in Vitória, where the normal school and the Our Lady Help of Christians School operated, whose graduates tended to prefer positions in the capital.

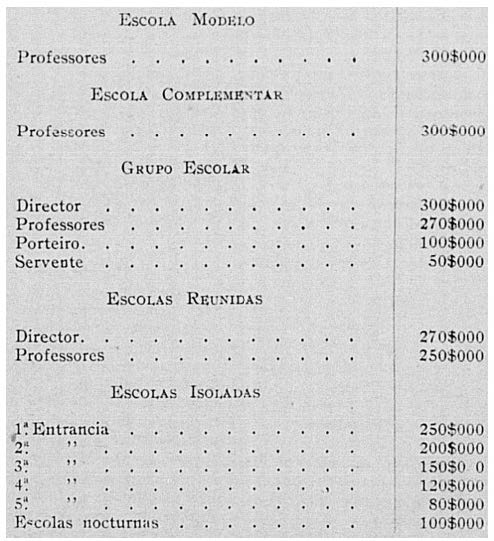

In terms of remuneration ( Figure 4 ), the difference between the salaries paid to teachers at the first level and those of the school groups is small, in contrast to rural or peripheral schools.

In Vitória, the movement of teachers between the GCSG and isolated schools suggests similarities in the teaching standards offered by both institutions. Some of these teachers even belonged to the local elite and received media attention. The Diário da Manhã , for example, praised “[…] the effort and dedication of this illustrious teacher for the brilliance of the presentation” made by an isolated school “[…] where the demands of teaching require a multiplicity of activities for its teacher to achieve this result” (Exibição […], 1909a , p. 2).

Significantly, the newspaper Commercio do Espirito Santo ’s praise for the school institutions and teachers in the capital makes no distinction between the school group and the isolated schools:

Our model school, our school group, our normal school, and the isolated schools in our capital are educational institutions, carefully arranged and equipped with the necessary pedagogical materials for the practice of the most modern methods, and directed by a teaching staff of which we should be proud, both for their qualifications and for their correctness .

(Nossa primazia, 1910 , p. 1, our emphasis).

Whether they worked in isolated schools or school groups, public teaching staff were freely appointed and dismissed by the state government. As for certified teachers, their vulnerability increased since their right to the position could be requisitioned in case of abolition or transfer ordered by the state president (Espírito Santo, 1910a ).

According to the regulations, “[…] deviating from the execution of the teaching program” or “[…] using a book not approved by the government” were grounds for punishment (Espírito Santo, 1910a , n/p). Regulation also occurred through the lens of morality: “[…] negligence or the practice of acts disapproved by society” would result in suspension (Espírito Santo, 1910a , n/p). This tight control was not without resistance, however. Through the press, Professor Olyntho Batalha expressed his indignation at the suspension he had received for alleged disobedience to teaching methods. Although the transcript is long, it is worth following his account:

[…] while I was carrying out the duties of my position in Villa Rubim, in full accordance with the established program , Mr. Inspector Archimimo appeared in my class […]. He asked the student Olympio Vieira […] to check the numbers written on the stone that he was trying to imitate. Now, because the poor boy did not imitate them perfectly, he was immediately slapped, and this happened more than once.

Next, he sat next to the student Bemvindo Alves de Abreu, […] who was trying to copy a sentence, and since the boy also did not know how to do it satisfactorily, he was subjected to the same process, receiving slaps . After Mr. Archimimo had vented his wrath , he left and returned later […] and called me to ask me how I was explaining National History. I replied that I told my students about the discovery of Brazil, important men of the Republic, etc.

Mr. Archimimo, who was prejudiced against me for reasons I don’t know, said harshly that I was a rebel.

Although humble as I am, I glared at him, saying that he had no reason to mistreat me and my students. Without replying, Mr. Archimimo left.

In light of what I have just recounted, who should be suspended or dismissed?

(Batalha, 1908 , p. 3, emphasis ours).

By asking who should be suspended, the teacher was most likely referring to Article 310 of Decree No. 43 , which expressly prohibits any form of corporal punishment under penalty of suspension. At the same time, the teacher’s testimony reveals the misfortune of students who are subjected to the wrath of an educational inspector.

When photographed, the uniformity of students from the same school suggests an essential element of the regime of appearances characteristic of the modern school (Dussel, 2005 ), which establishes the boundaries between the school and the outside world through the creation of its own aesthetics ( Figure 5 ).

In contrast, school uniforms are absent from the portrait of one of the classes at the school of Argolas, indicating the unequal material conditions of care for children attending isolated schools ( Figure 6 ).

Between photographs, legislative documents, and news about the school and its subjects, this research has traced the discursive boldness of the prescriptions for the modern school, the authoritarianism of the state, the control over the exercise of public teaching, and the attempt to homogenize student behavior. On the margins of these inducing forces, the indicative reading of cross-referenced sources reveals, above all, profound contrasts between the monolithic and often idealized discourse that directed public educational policies and the heterogeneity of school life.

Organization of teaching in isolated schools: possible teaching methods

According to the reform of public education in Espírito Santo initiated in 1908, schooling would be “[…] practical, concrete, essentially empirical, and with the complete exclusion of abstract rules” so that the child’s abilities would develop “[…] gradually and harmoniously, through intuitive processes, with the teacher always aiming to develop observation” (Espírito Santo, 1910a , n/p). It was believed, therefore, that careful and organized observation would enable the progressive transition from sensory knowledge to a higher mental elaboration of knowledge (Faria Filho, 2000 ).

This line of thought advocated pedagogical modernization with the aim of making school more attractive, attributing the increase in school attendance to the “[…] good results of the new method and the current organization of teaching.” Thus, the “[…] phenomenon was celebrated that parents are now unable to prevent their children from attending school without great inconvenience to them, whereas in the past school was considered a punishment” (Espírito Santo, 1910b , p. 22).

In this sense, there is a valorization of new disciplinary methods over corporal punishment, associating intuitive methods with ideas of domesticity and motherhood (Durães, 2011 ). In the chronicle As escolas de hoje (Today’s Schools), published in Diário da Manhã , the author compares the school of his childhood—“[…] a solitary dungeon where one went to atone”—with the renewed primary schools, seen as an “extension of the home,” where “[…] the paddle is replaced by maternal caresses and handwritten notes by books with beautiful stories, decorated with fine engravings.” He praised festive practices and awards, celebrating the replacement of the “[…] heavy-set teacher, with large glasses and a handkerchief from Alcobaça” by “[…] a caring and almost always beautiful young woman” (Braga, 1908 , p. 1).

This scenario of idealizations coincides with the increasing presence of women in primary education, especially to meet the requirement of mixed-sex schools with female teachers (Espírito Santo, 1908c ). In this context, Decree No. 43 established that affection should guide school discipline, using advice and friendly persuasion (Espírito Santo, 1910a ). The means of discipline—whether corrective or encouraging—were proposed to be the giving of rewards and the imposition of punishments.

In terms of curriculum, Reading, Oral Language, Written Language, and Arithmetic covered identical content to that taught in equivalent classes in school groups. Other subjects offered superficial approaches to the content taught in the school groups. Thus, if in the individual school one of the Natural History lessons included “[…] a talk on leaves, flowers, fruits, roots and stems” (Espírito Santo, 1910a , n/p), in the school group the study of each part of the plants was deepened, accompanied by practical exercises. Or, while in school groups’ experiments on the composition of air, water, combustion, and evaporation were part of the Physics and Chemistry discipline, for isolated schools a general lecture on the subject was foreseen. For reasons to be discussed later, the only subject intended for the fourth year of the school group whose content was fully covered in the individual schools was Agricultural Notions.

In Governor Monteiro’s logic, the program directed at individual schools was “perfectly feasible,” given their modest organization and, above all, their “[…] essential aim of preparing children for the first practical needs of life” (Espírito Santo, 1909b , p. 5). In this line of thought, different curricula indicate the social function attributed to each type of primary school. The content related to isolated institutions, by attributing needs strictly defined by the social position of the students, sanctioned and perpetuated existing inequalities (Cardoso, 2013 ).

The note published by Commercio do Espírito Santo could not have been more explicit when addressing the work done by the students of the individual school of Vila Rubim:

Particularly noteworthy were the making of household linen, mending, patching, backstitching, buttonholing and other small tasks that a good housewife, especially one from the lower classes, must master perfectly .

(Exposição […], 1909b , p. 2, emphasis ours).

The disparity between the content of Physical Education and Civic and Moral Education ( Table 3 ) also becomes significant when one considers the centrality of these disciplines in the context of republican education. In the individual schools, the lessons intended for the first year of the school groups were replicated in a reduced form that covered a detailed and extensive program, in accordance with the so-called triad of comprehensive education—physical, moral, and intellectual—that aimed to shape the new citizen (Campos, 2016 ).

Table 3 - Civic and Moral Education programs for public elementary school

| ISOLATED SCHOOLS | ||

|---|---|---|

| SIMULTANEOUSLY FOR ALL CLASSES | Draw the students’ attention to the lessons in the reading book that arouse respect and love for the things of our country and are aimed at forming good feelings. | |

| SCHOOL GROUPS | ||

| 1st year | - Recitation of civic and moral passages; - Poems and anecdotes that arouse respect and love for the things of our country and that also aim to form good feelings; - The names of the most important local, state, and national authorities. |

|

| 2nd year | - Ideas about local government; - Names of state and federal capitals; - Stories that instill a love of goodness in children; - Children’s duties to parents and teachers; - Duties of siblings to each other; - Duties to staff; - Children at school: attendance, obedience, work, and behavior; - Duties to colleagues; - Duties to the country. |

|

| 3rd year | - State government; - National flag: explanation of the colors and stars of the national flag; - Major duties and rights of citizens; - General ideas about the powers of the state; - Always take advantage of the moral lessons in the reading books and of events that are important to the formation of the students’ character. |

|

| 4th year | - Homeland; - The flag as a symbol of the homeland; - Examples of love of country; - National dates; - Forms of government; - To show in clear terms the advantages of the republican form; - Constitution of the state of Espírito Santo; - Brazilian federal constitution; - Individual morality; - Spiritual duties; - Bodily duties; - Temperance, prudence, courage, sincerity, keeping one’s word, personal dignity; - Duties: of justice, charity, family, professional, civic, and of nations among themselves. |

|

Source: Espírito Santo ( 1910a ).

Based on the understanding that “[…] all disciplines of the primary school are suitable for civic education” (Espírito Santo, 1910a , n/p), the differences in civic-moral education were not limited to this specific subject. When examined in contrast to the curriculum of the school group, the limited content of the civic education intended for the isolated schools reveals the population group for which the preparation of the new, republican, modern man was aimed at.

The concepts of active and inactive citizenship shed light on these issues, understanding that the literacy required for electoral participation reveals a context in which political rights were not granted naturally, but only to those considered deserving (Carvalho, 2004 ). In other words, inactive or simple citizens, holders of civil rights of citizenship, were distinguished from active or full citizens, who also had political rights.

In this line of reasoning, one can understand the curricula of isolated schools, which are typically designed to educate the rural and peripheral populations of urban centers. Not surprisingly, as we pointed out earlier, Agricultural Notions was the only subject offered in isolated schools that covered content common to the curricula of primary schools in general, including those intended for the 4th grade.

Especially in the city of Vitória, as we have seen, some individual schools approached the standard of the school groups. However, sources related to the participation of schools in public festivities point to hierarchical procedures adopted on these occasions. For example, reporting on an end-of-year celebration, the press highlights the departure of a ship from Cais do Imperador, “[…] carrying not only the students of the normal and model schools of Jeronymo Monteiro, the GCSG, and the isolated schools, but also the respective teaching staff and several other distinguished persons” (Festa […], 1908 , p. 1). The order of disembarkation, however, reveals a first order:

[…] first to disembark was the school battalion of Jeronymo Monteiro [belonging to the Model School of the same name], which, positioning itself to the right side of the Hostel, after the initial maneuvers, saluted the ground, followed by the other students who formed on the left side , singing the National Anthem on this occasion.

(Festa […], 1908 , p. 1, emphasis ours).

Then a series of recreational activities took place—sports competitions between students at the normal school and the model school, lunch, and a dance—which ended with the distribution of diplomas to the graduates of the model school who would continue their studies at the normal school.

The following year, the same place was the stage for the Tree Festival, which consisted of three main moments: the school parade, the civic sports demonstrations, and the tree planting. Although the newspaper Commercio reported the participation of some schools from the capital, according to Diário da Manhã, only schools of Vila Rubim and Argolas were present.

Overall, when the isolated schools participated in the ceremonies, the teachers did not integrate the scheduled performances. Besides participating in collective moments—such as the recitation of the national anthem and the dance soiree—the students of the isolated institutions in the capital attended the events as spectators. In the official dissemination of images related to the Tree Festival, the individual schools disappear.

In a context of standardization of teaching, the predominance of isolated schools led to the creation, in November 1916, of an institution aimed at guiding the teachers who worked in them. According to Governor Marcondes de Souza (1912–1916):

Another need greatly felt in the public education service is for a model isolated school, coeducational, for the training of student-teachers.

At present, both the students of the 4th year of the Normal School and the candidates for primary teaching exams practice at the Model School of the Capital.

However, the learning done in this establishment is based on the teaching provided in the School Groups, which differs greatly from the isolated schools . The model isolated school could function as an annex to the Normal School, under the supervision of a normalist teacher, with a small additional expense related to the teacher’s salary. (Espírito Santo, 1916 , p. 30, emphasis ours).

The model isolated school, attached to the normal school, was run by a normalist teacher as well as had three classes. The government report of 1917 states that the institution operated regularly and fulfilled its purpose: the learning of the 4th year students at the normal school and the state competition teachers. In summary, “[…] in the model isolated school, the learning of the teaching of the isolated schools is done, while in the model school of Jeronymo Monteiro, the learning of the teaching of the school groups is done” (Espírito Santo, 1917 , p. 67) 9 .

Unlike Jerônimo Monteiro’s model school, however, the model of the isolated school received little attention in the press and in official documents. Diário da Manhã and government reports were limited to reporting that the institution was operating regularly, and the number of students enrolled, which varied between 30 and 60 10 .

Despite the discursive emphasis on the model of isolated schools in Espírito Santo, the disparity in the operating conditions of most of these institutions during the period studied, combined with the sparse and monosyllabic tone of government reports and notes circulated by the pro-government press, always ready with easy praise, suggest a practical erosion of the normative prescriptions related to isolated schools. As a result, the few formal changes observed in these schools, which represent the bulk of local public education, could not prevent the production of deficient isolated schools. What is more serious is that the process of differentiation from the only local school group also contradicted the idealization created around the republican institution in practice.

Final considerations

The historiography of Brazilian education points to an inherently established relationship of opposition and competition between isolated schools and school groups (Souza, 2016 ). The emergence of the latter would explain the designation isolated given to the unitary school—also called elementary or primary school. On the other hand, although the designation is justified by the unitary functioning of these institutions, as opposed to the grouping of graded schools, the choice of the adjective isolated ended up undermining the dominant school model, understood as the antithesis of the primary institution idealized according to the patterns of republican modernization. Thus, the condition of an isolated school symbolically signifies a change aimed at demarcating the opposition between the school of the past and the modern school. Therefore, this designation ratified “[…] an organizational condition whose representation included several negative elements, including the association of this type of school with backwardness, precariousness, and inefficiency” (Souza, 2016 , p. 371).

In Espírito Santo, while the creation of the school group—and, above all, the symbolic force that accompanied it—devalued isolated primary schools because of local dynamics, the weak and slow implementation of school groups also led to the qualification of some of these institutions, especially those located within the urban perimeter of Vitória. In the capital of Espírito Santo, this negative evaluation coexisted with forced ambiguities, on the one hand because of the fragility of the local school group, and on the other hand—despite the inconvenience decreed in 1908—because of the indispensable role of the isolated schools, to the point of their modeling in 1916.

Therefore, in contrast to the discursively constructed binaries regarding the opposition of quality versus precariousness in educational modes at the beginning of the last century, the differentiation between the school group and the isolated school is understood as “[…] a conflict made of challenges, mutual borrowings” (Ginzburg, 2007 , p. 9). This is considering that the markers of difference among these three institutions are mainly related to legal regulations, status, and visibility given to each of them.

REFERENCES

BATALHA, Olyntho Rodrigues. Quem deve ser suspenso ou demettido? Estado do Espirito Santo, Victoria, p. 3, 7 nov. 1908. [ Links ]

BONATO, Elaine Maria. A formação de professores para as séries/anos iniciais do ensino fundamental e a avaliação de seu desempenho no município de Dois Vizinhos no período de 1971 a 2008. 2010. 202 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná, Curitiba, 2010. [ Links ]

BRAGA, Belmir. As escolas de hoje. Diário da Manhã, Victoria, p. 1, 28 ago. 1908. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Divisão administrativa em 1911 da República dos Estados Unidos do Brazil. Rio de Janeiro: Directoria do Serviço de Estatística, 1913. Trabalho organisado na Primeira Secção da Directoria do Serviço de Estatística. [ Links ]

CAMPOS, Karen Calegari Santos. A educação do corpo no projeto republicano na cidade de Vitória (1908-1912). 2016. 214 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, 2016. [ Links ]

CARDOSO, Maria Angélica. A organização do trabalho didático nas escolas isoladas paulistas: 1893 a 1932. 2013. 259 f. Tese (Doutorado) – Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2013. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, José Murilo. Os bestializados: o Rio de Janeiro e a República que não foi. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2004. [ Links ]

COSTA, Cíntia Moreira. “O éden desejado e querido”: história, fotografia e educação no Espírito Santo durante a Primeira República (1908-1912). 2016. 177 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em História) – Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, 2016. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO DA MANHÃ, Victoria, p. 2, 14 abr. 1910. [ Links ]

DURÃES, Sarah Jane Alves. Aprendendo a ser professor(a) no século XIX: algumas influências de Pestalozzi, Froebel e Herbart. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 37, n. 3, p. 465-480, dez. 2011. [ Links ]

DUSSEL, Inés. Cuando las apariencias no engañan: una historia comparada de los uniformes escolares en Argentina y Estados Unidos (siglos XIX - XX). Pro-Posições, Campinas, v. 16, n. 1, p. 65-86, jan./abr. 2005. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Decreto nº 43, de 5 de março de 1910. Dá regulamento aos diversos ramos da administração do Estado. Diário da Manhã, Victoria, 1910a. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Decreto nº 137, de 25 de julho de 1908. Classifica em tres categorias as escolas publicas de ensino primario do Estado e approva o programma das mesmas escolas. Diário da Manhã, Victoria, 1908a. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Decreto nº 197, de 10 de outubro de 1908. Supprime as escolas isoladas desta capital e dispensa os respectivos professores que não tenham sido aproveitados na nova organisação do ensino. Diário da Manhã, Victoria, 1908b. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Decreto nº 230, de 3 de fevereiro de 1909. Diário da Manhã, Victoria, 1909a. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Lei nº. 545, de 16 de novembro de 1908. Dá nova organização à Instrução Pública Primária e Secundária. Diário da Manhã, Victoria, 1908c. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Relatório apresentado ao Exmo. Sr. Dr. Jeronymo de Souza Monteiro, Presidente do Estado do Espírito Santo, pelo Sr. Inspector Geral do Ensino Carlos A. Gomes Cardim em 28 de julho de 1909. Victoria: Imprensa Official, 1909b. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Requerimento enviado ao Inspetor Geral do Ensino com abaixo-assinado contra supressão da escola da Ilha das Caieiras. Fundo de Educação do Arquivo Público Estadual do Espírito Santo. Victoria: [s. n.], 1909c. Caixa nº 28, 26 fev. 1909c. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Requerimento enviado ao Inspetor Geral do Ensino com abaixo-assinado solicitando a criação de uma escola mista em Divisa. Victoria: Fundo de Educação do Arquivo Público Estadual do Espírito Santo, 1911. Caixa nº 30, 15 fev. 1911. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Requerimento enviado ao Presidente do Estado referente ao aluguel de uma casa para funcionamento da escola de Santo Antônio. Victória: Fundo de Educação do Arquivo Público Estadual do Espírito Santo, 1912. Caixa nº 30A, 5 out. 1912. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Inspetor geral do Ensino (Oliveira). Relatório apresentado ao Exmo. Sr. Presidente do Estado Dr. Jeronymo de Souza Monteiro em 30 de julho de 1910 [por] Deocleciano Nunes de Oliveira, Inspector Geral do Ensino. Victoria: Imprensa Estadual, 1910c. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Presidente de Estado (1908-1912: Monteiro). Exposição sobre os negócios do Estado no quadriênio de 1909 a 1912 enviada ao Congresso Legislativo do Espírito Santo em 23 de maio de 1912 [por] Jeronymo de Souza Monteiro, Presidente do Estado do Espírito Santo. Victoria: Imprensa Official, 1913a. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Presidente de Estado (1908-1912: Monteiro). Mensagem enviada ao Congresso Legislativo do Espírito Santo em 23 de setembro de 1910 [por] Jeronymo de Souza Monteiro, Presidente do Estado do Espírito Santo. Victoria: Imprensa Estadual, 1910b. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Presidente de Estado (1916-1920: Monteiro). Mensagem enviada ao Congresso Legislativo do Espírito Santo em 13 de setembro de 1917 [por] Bernardino de Souza Monteiro, Presidente do Estado do Espírito Santo. Victoria, 1917. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Presidente de Estado (1912-1916: Souza). Mensagem enviada ao Congresso Legislativo do Espírito Santo em 22 de outubro de 1913 [por] Marcondes Alves de Souza, Presidente do Estado do Espírito Santo. Victoria: Papelaria e Typographia Pimenta & Comp., 1913b. [ Links ]

ESPIRITO SANTO (Estado). Presidente de Estado (1912-1916: Souza). Mensagem enviada ao Congresso Legislativo do Espirito Santo em 08 de setembro de 1915 [por] Marcondes Alves de Souza, Presidente do Estado do Espirito Santo. Victoria: Typographia do Diario da Manhã, 1915. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO (Estado). Presidente de Estado (1912-1916: Souza). Relatório sobre os negócios do Estado no período governamental de 1912 a 1916 enviado ao Congresso Legislativo do Espírito Santo em 22 de maio de 1916 [por] Marcondes Alves de Souza, Presidente do Estado do Espírito Santo. Victoria: Typographia do Diário da Manhã, 1916. [ Links ]

EXPOSIÇÃO. Commercio do Espirito Santo, Victoria, p. 2, 26 nov. 1909b. [ Links ]

EXPOSIÇÃO de prendas. Diário da Manhã, Victoria, p. 2, 28 nov. 1909a. [ Links ]

FARIA FILHO, Luciano Mendes. Instrução Elementar no Século XIX. In: LOPES, Eliana Marta Teixeira; FARIA FILHO, Luciano Mendes; VEIGA, Cynthia Greive (org.). 500 anos de educação no Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2000. p. 135-150. [ Links ]

FESTA escolar. Commercio do Espirito Santo, Victoria, p. 1, 30 nov. 1908. [ Links ]

GINZBURG, Carlo. Mitos, emblemas, sinais: morfologia e história. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1989. [ Links ]

GINZBURG, Carlo. O fio e os rastros: verdadeiro, falso, fictício. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2007. [ Links ]

GINZBURG, Carlo. Relações de força: história, retórica, prova. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2002. [ Links ]

LOCATELLI, Andréa Brandão. Espaços e tempos de grupos escolares capixabas na cena republicana do início do século XX: arquitetura, memórias e história. 2012. 206 p. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, 2012. [ Links ]

NOSSA PRIMAZIA. Commercio do Espirito Santo, Victoria, p. 1, 16 maio 1910. [ Links ]

PORTELA, Mariliza Simonete. As Cartas de Parker na matemática da escola primária paranaense na primeira metade do século XX: circulação e apropriação de um dispositivo didático pedagógico. 2014. Tese (Doutorado em Educação Matemática) – Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná, Curitiba, 2014. [ Links ]

ROSTOLDO, Jadir Peçanha. A cidade republicana na belle époque capixaba: espaço urbano, poder e sociedade. 2008. 211 f. Tese (Doutorado em História Social) – Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2008. [ Links ]

SALIM, Maria Alayde Alcântara; MANSO, Márcia Helena Siervi. O cenário da política educacional no Espírito Santo durante a Primeira República. Temas em Educação, João Pessoa, v. 25, n. 1, p. 22-42, jan./jun. 2016. [ Links ]

SIMÕES, Regina Helena Silva; SALIM, Maria Alayde Alcantara. A organização de grupos escolares capixabas na cena republicana do início do século XX: um estudo sobre a reforma Gomes Cardim (1908-1909). Cadernos de Pesquisa em Educação - PPGE/Ufes, Vitória, v. 18, n. 35, p. 93-111, jan./jun. 2012. [ Links ]

SIQUEIRA, Maria da Penha Smarzaro; VASCONCELOS, Flavia Nico. Urbanização da cidade e nova concepção portuária: a trajetória compartilhada pela cidade e porto de Vitória na construção do progresso e de identidades. In: CONGRESO LATINOAMERICANO DE HISTORIA ECONÓMICA Y XXIII JORNADAS DE HISTORIA ECONÓMICA, 3., 2012, San Carlos de Bariloche. Anais [...]. San Carlos de Bariloche: Asociación Argentina de Historia Economica, 2012. p. 1-26. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Rosa Fátima de. A configuração das Escolas Isoladas no estado de São Paulo (1846-1904). Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, Maringá, v. 16, n. 2, p. 341-377, abr. 2016. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Rosa Fátima de. A contribuição dos estudos sobre grupos escolares para a historiografia da educação brasileira: reflexões para debate. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, Maringá, v. 19, p. 1-24, 2019. [ Links ]

VASCONCELLOS, João Gualberto Moreira. A invenção do coronel: ensaio sobre as raízes do imaginário político brasileiro. Vitória: Ufes, 1995. [ Links ]

VIDAL, Diana Gonçalves (org.). Grupos escolares: cultura escolar primária e escolarização da infância no Brasil (1893-1971). Campinas, SP: Mercado de Letras, 2006. [ Links ]

*

The authors take full responsibility for the translation of the text, including titles of books/articles and the quotations originally published in Portuguese.

- Data availability: the entire data set supporting the results of this study has been referenced in the article itself and is publicly available.

1- Data availability: the entire data set supporting the results of this study has been referenced in the article itself and is publicly available.

3- At that time, Argolas belonged to the municipality of Vila Velha. The port was located in front of Vitória Bay, on the opposite shore to the old Cais do Imperador. In the same region, there was the station of the Southern Espírito Santo Railroad, responsible for connecting the capital with the interior of the state and, later, with Minas Gerais. In 1924, the district of Argolas was officially annexed to the municipality of the capital.

4- In 1911, the city of Vitória consisted of three districts: Vitória, Carapina, and Queimado (Brasil, 1913 ).

5- The Monteiro family, owners of a wealthy coffee plantation, made up this rural oligarchy and based their political power on the pillar of colonelism: “[…] the elitist pact, whose strategies were based on violence, revenge, intra-family solidarity, electoral corruption and, above all, the policy of distributing favors and punishments, as well as the private appropriation of the state” (Costa, 2016 , p. 46). Therefore, the measures proposed by Jerônimo Monteiro were crossed by the ambiguities that marked Espírito Santo politics during the First Republic and were outlined in a context of tension between the modernization of certain elements of public life and the maintenance of the broader structure of social privileges (Vasconcellos, 1995 ).

6- The populous Vila Rubim area was mainly home to workers. The area, once called a straw city due to its precarious buildings, was benefited by the Monteiro administration, becoming a subdivision and part of the capital’s urban perimeter. Urbanization, however, did not occur without conflict of interest between residents and the state and, due to its hygienist bias, the reform often led to the expulsion of popular groups (Rostoldo, 2008 ).

7- Produced by American teacher Francis Wayland Parker, the material presented a modern proposal for teaching arithmetic based on the intuitive method, as opposed to traditional practices of memorization and repetition (Portela, 2014 ).

8- Mapping created by cross-referencing official acts published in Diário da Manhã with official letters and requests located in the collection of the Education Fund of the State Public Archives of Espírito Santo.

9- Isolated model schools exist in at least three other states: São Paulo, Alagoas, and Paraná. The first institution of this type was created in São Paulo in 1908 and spread throughout the state. By 1913, there were already fourteen isolated model schools in seven São Paulo municipalities (Cardoso, 2013 ). The one in Alagoas was created in 1911 and the one in Paraná in 1921 (Bonato, 2010 ).

Received: April 30, 2023; Accepted: October 30, 2023; Revised: September 12, 2023

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons attribution-type BY 4.0 .

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons attribution-type BY 4.0 .

text in

text in