INTRODUCTION

Current societies face challenges in the health area due to the prolongation of life expectancy, with a consequent increase in the prevalence of chronic-degenerative diseases due to the population’s aging process. On the other hand, according to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), this reality brings up the importance of including in medical education topics related to end-of-life care and the process of dying. Emerging diseases, such as COVID19, combined with demographic and epidemiological transitions, require specific care processes during illness and death. People who are undergoing the process of finitude, whether in acute processes or those with advanced diseases, can benefit from the palliative care (PC) approach, corroborated by scientific evidence. Adequate support from professionals with PC resources requires rethinking the role of medical schools aiming to meet the health needs of patients and families1)-(4).

The PC approach emerges from a historical and sociocultural process, with the medieval hospices, places of lodging destined to accommodate people who needed care due to illness or hunger, as examples of this modality. However, it was only in the 1960s that modern palliative care emerged. Two health professionals, Cicely Saunders in the United Kingdom and Elizabeth Kübler-Ross in Switzerland/USA promoted the teaching and research in PC, aiming at best practices for people who needed assistance in the finitude of life5),(6).

In Brazil, the pioneering work of Professor Marco Túlio A Figueiredo has been recorded, by creating an elective course in PC for students at Universidade Federal de São Paulo from 1994 to 2008. According to Oliveira et al7, when evaluating the teaching of bioethics and PC, there is a fragile commitment of Brazilian medical schools in relation to PC teaching.

The approach in PC can be understood as a care modality recognized as adequate for children and adults in situations of suffering and with life-threatening diseases, as well as their families. They must be offered to people whose conditions lead to a high risk of mortality, negative impact on quality of life and implications for body functions. PC take the individual into account as a whole, regarding the physical, psychological, social and spiritual aspects, and not just their illness. For the PC to be effective, they require interprofessional and interdisciplinary work to manage symptoms and prevent complications8),(9.

The intensification of PC training is relevant in teaching since undergraduate school, being a strategy that corroborates for de-hospitalization and greater user satisfaction. PC teaching, when included in the undergraduate course, captures the attention of future doctors, improving the care offered to the patient. A greater sense of control is observed in the interaction with patients and family members, as well as compassion, empathy and respect, through exposure to patients with advanced diseases10),(11.

It is observed that curriculum presentations vary considerably worldwide, even in countries where palliative medicine has become mandatory in undergraduate medical courses. According to Von Gunten et al12 and Schulz et al13, changes in attitudes are important challenges, requiring the interchanging of didactic and experiential strategies, enhanced by self-reflection and interdisciplinary teaching to achieve the competencies required for the PC learning process.

PC competencies are aligned with patient-centered care and respect for autonomy, as well as family approach. These involve technical, cultural and ethical issues, such as the decrease in inappropriate and little effective use of invasive medical intervention to the detriment of resources to improve the quality of life and the dealing with the process of death in human existence14),(15.

According to the international literature, the evaluation of PC teaching have shown changes in students’ values and attitudes, and are recognized as essential for medical training, contributing to the acquisition of communication skills, as well as the examination of the patient’s preferences regarding end-of-life care, the relaying of bad news and the conversation about spiritual issues and their practices16)-(18.

According to MacPherson et al19, PC teaching should be integrated into the undergraduate curriculum, enabling better symptom management, teamwork and care with a focus on the person since the initial stages of illness.

According to Toledo et al20, there is little data on PC education in Brazil and a scarce literature corroborates this scenario. The authors comment on the identification of barriers in PC teaching and point out the challenges faced by the coordinators of medical courses, such as the lack of specialized teaching staff, the absence of clinical PC service, reduced interest by the institution, negligible funds, scarcity of time and of appropriate didactic material.

Considering these data, PC teaching is a necessity for the training of qualified doctors. This situation raises the following questions:

How is PC teaching currently in Brazilian schools?

Which pedagogical projects guide the training of health professionals focused on care, transforming the focus of attention from cure to care?

This study aims to identify the Brazilian medical courses that include PC in their curriculum, and how it has been taught.

METHODS

This is a descriptive, exploratory and cross-sectional study with a quantitative approach, which used secondary data on medical schools that included PC teaching in Brazil. The research field is concentrated in medical schools that have PC teaching in their curriculum. It started by searching for all medical schools registered in the official Brazilian database, available on the electronic system of the Ministry of Education of Brazil (e-Mec Register of Higher Education Institutions and Courses), and available medical school websites (www. Escolasmedicas.com.br)21),(22. Subsequently, the websites of each school were consulted for the analysis and selection of the ones that have a palliative care discipline in the curricular matrix, from August to December 2018. Aiming to identify which schools have the PC discipline in their curricular matrix, the following topics were used in the search: palliative care, thanatology, processes of death, finitude and death, oncology and PC, geriatrics and PC, aging and death.

The distribution profile of the schools was analyzed regarding: Administrative Region and Federation Units (FU): number of vacancies offered in the 1st year; type of institution, whether public or private; and among public ones, the type of administration, whether federal, state or municipal. The same profile analysis was carried out in relation to medical courses that have a PC discipline in their curricular matrix. To analyze the syllabi of the offered disciplines, we used the variables: period offered, workload, practice scenario, type of discipline (elective or mandatory) based on the recommendations of international entities for the teaching in palliative care and the 2014 National Curricular Guidelines for Medical Courses23),(24.

RESULTS

We identified 315 medical schools in operation in Brazil during the assessed period. As for the geographic distribution, 42.5% are located in the Southeast, 16.5% in the South, 8.9% in the Midwest, 23.9% in the Northeast and 8.2% in the North region. The schools are distributed throughout all Brazilian states, with most of them being private schools (63.8%). Approximately 33,520 vacancies were made available for the first year of medical courses in 2018, almost half (46%) in the Southeast region, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Distribution of medical schools according to geographic distribution (Region-FU), number of vacancies in the 1st year and type of institution, Brazil-2018

| Region | FU | N. of vacancies | Public schools | Private schools | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| NORTH | PA | 690 | 4 | 67 | 2 | 33 |

| AM | 465 | 3 | 60 | 2 | 40 | |

| RO | 325 | 1 | 25 | 3 | 75 | |

| AC | 161 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 | |

| AP | 60 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| TO | 518 | 2 | 33 | 4 | 67 | |

| RR | 140 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 2,359 | 14 | 60 | 12 | 40 | |

| NORTHEAST | BA | 2,164 | 11 | 52 | 10 | 48 |

| PE | 1,490 | 6 | 55 | 5 | 45 | |

| PB | 985 | 3 | 33 | 6 | 67 | |

| CE | 1,093 | 4 | 50 | 4 | 50 | |

| PI | 631 | 5 | 71 | 2 | 39 | |

| RN | 472 | 2 | 40 | 3 | 60 | |

| MA | 539 | 2 | 33 | 4 | 67 | |

| AL | 495 | 2 | 40 | 3 | 60 | |

| SE | 320 | 2 | 67 | 1 | 33 | |

| Total | 8,189 | 37 | 49 | 38 | 51 | |

| MIDWEST | GO | 1,374 | 4 | 31 | 9 | 69 |

| DF | 336 | 2 | 50 | 2 | 50 | |

| MT | 431 | 4 | 67 | 2 | 33 | |

| MS | 388 | 4 | 80 | 1 | 20 | |

| Total | 2,529 | 14 | 47 | 14 | 53 | |

| SOUTHEAST | SP | 7,300 | 9 | 15 | 51 | 85 |

| MG | 4,787 | 14 | 30 | 32 | 70 | |

| RJ | 2,789 | 5 | 23 | 17 | 77 | |

| ES | 718 | 1 | 17 | 5 | 83 | |

| Total | 15,594 | 29 | 22 | 105 | 78 | |

| SOUTH | PR | 2,139 | 9 | 45 | 11 | 55 |

| SC | 957 | 4 | 33 | 8 | 67 | |

| RS | 1,753 | 7 | 35 | 13 | 65 | |

| Total | 4,849 | 20 | 38 | 32 | 62 | |

| Overall total | 33,520 | 114 | 36 | 201 | 64 | |

There were 114 public medical schools (36.2%). In the states of Amapá and Roraima, 100% of medical schools are public. Most medical schools are private (201), totaling 105 (52%) courses, all of them located in the Southeast region.

As for the teaching of PC, we identified 44 medical schools that have the discipline of PC in their curricular matrix, as shown on the official websites of educational institutions, which corresponds to 14% of the total number of schools, and 16% of the total number of vacancies offered for 1st year of medical school. The distribution of these schools according to the Region, Federation Unit (FU), number of vacancies offered in the first year and the type of the institution are shown in Table 2. It is worth noting that there are no medical courses in the North region of the country that offers training in PC. On the other hand, the predominance of schools with the discipline of PC (52%) is also located in the Southeast region.

Table 2 Distribution of medical schools with the PC discipline according to the geographic distribution (Region-FU), number of vacancies in the 1st year and type of institution, Brazil-2018

| Region | FU | N. of vacancies | Public Schools | Private Schools | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| NORTHEAST | BA | 525 | 3 | 50 | 3 | 50 |

| CE | 460 | 2 | 50 | 2 | 50 | |

| RN | 80 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 1,065 | 6 | 55 | 5 | 45 | |

| MIDWEST | MS | 140 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 2 | 100 | 0 | 100 | ||

| SOUTHEAST | SP | 986 | 4 | 67 | 2 | 33 |

| MG | 945 | 1 | 17 | 5 | 83 | |

| RJ | 1,309 | 2 | 22 | 7 | 78 | |

| ES | 228 | 2 | 50 | 2 | 50 | |

| Total | 3,468 | 7 | 28 | 16 | 64 | |

| SOUTH | PR | 620 | 3 | 50 | 3 | 50 |

| SC | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| RS | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | |

| Total | 820 | 4 | 50 | 4 | 50 | |

| Overall Total | 5,493 | 19 | 43 | 25 | 57 | |

Of the 44 institutions that included the palliative care discipline in the curriculum, it is mandatory in 27 schools (61%) and elective in 17 schools (39%).

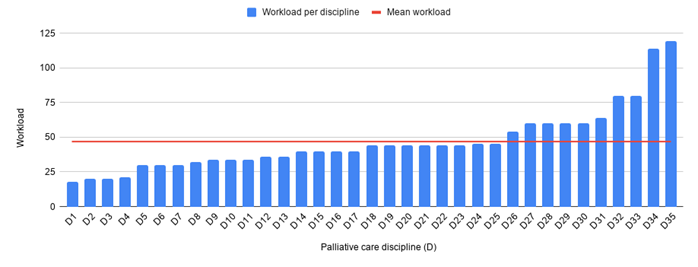

In most schools, PC training occurs in the clinical cycle (3rd and 4th years) with a median workload of 46.9 hours, varying from 18 h to 119 h (Chart 1). Schools that follow a modular curriculum were excluded from the estimate. The most frequent teaching scenario is the classroom, that is, a predominantly theoretical approach. Scenario diversity was observed in seven institutions, with a service-school-community teaching model and medical practice. PC teaching is part of the modular model (workload > 120h) in twelve schools, consisting of theory and practice, but a specific PC workload cannot be identified. In two schools, PC is included in more than one moment of the course as a discipline. The syllabi were not available in two of the schools, but only appeared as being part of the curricular matrix. As shown in the programs of the assessed schools, the predominant contents were thanatology, geriatrics, senescence and finitude, humanization, ethics-bioethics, pain, oncology and chronic diseases.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that the geographic distribution of medical schools that offer PC teaching is similar to that of total number of schools in the country, with the exception of the North region, which has no schools that include PC as a discipline. The highest concentration of medical courses is found in the Southeast region, which may be an indicator of the country inequalities (Table 2).

When we observe the distribution of schools that have PC teaching throughout the Brazilian states, greater investment is verified in some states. It is observed that 50% of the schools in the state of Ceará and 41% of the schools in the state of Rio de Janeiro have a PC discipline. In the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, 40% of the medical schools have a PC discipline. On the other hand, in the state of São Paulo, 10% of the schools have a PC discipline. Inter and intra-regional differences are evident. In the Southern region of the state of Paraná, 30% of schools have a PC discipline and in the State of Rio Grande do Sul, only 5%. This reality may reflect the legal frameworks to promote PC, both at the national and state levels. These are initiatives by the society and the state legislative power, as is the case of the states of Paraná and Rio de Janeiro, which reinforce the promotion of public policies for the reorganization of services and training of human resources in the field of PC25)-(27.

Regarding the medical schools with a PC discipline, it can be observed that 25 (57%) are private schools. This proportion in relation to the type of funding entity is also observed in the total of Brazilian medical schools, which reflects a trend towards the progression through the privatization in medical education, as described in the literature28.

International studies point to a worldwide consensus on the importance of teaching PC in undergraduate courses. However, its inclusion and the consolidation of the teaching-learning process is very different in each country and school. The realities are very different, considering the cultural, economic, political and social aspects. Although it is considered important, there are challenges for the inclusion of palliative care teaching worldwide. In Latin America, only 05 countries are officially certified in palliative care. In Brazil, palliative medicine is considered an area of activity29),(30. In the USA, specific PC teaching is declared in three quarters of medical schools, a much higher percentage than that found in Brazil, where it was only identified in 14% of schools.

According to Floriani (2008), the importance of a teaching policy with continuing educational programs in PC is pointed out, in line with other experiences from around the world. The inclusion of the PC discipline can reduce distortions considering the curative therapeutic limitations, reinforcing the relationship of care and other non-curative approaches in advanced-stage diseases31),(32.

According to Calda et al33, the challenges in implementing PC teaching can be attributed to the lack of knowledge about PC, generating resistance to changes, which persist due to the teaching staff’s low level of training in this area of knowledge. On the other hand, the curricula have excessive workloads and limited resources.

The study program content found in the syllabus of Brazilian schools points to the domains recommended by scientific entities and national and international studies. Some schools emphasize thanatology and the study of death and dying; others address the life cycle as in geriatrics, senescence and finitude, and others in groups of more specific diseases, such as oncology and symptom management such as pain. According to MacPherson, the teaching should be integrated into the undergraduate curriculum, and it is recommended it should include areas of knowledge such as symptom control, teamwork and caring for the individual from the basic stages of illness34.

The Brazilian teaching experiences in PC have a median workload of 46.9 hours, consistent with the recommended one, although with variations in modular formats. According to international entities, such as the Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance (WPCA, 2014) and the recommendations of the National Academy of Palliative Care, the training of professionals can be divided into three levels, with basic training in PC being recommended in undergraduate school in all health areas, with the specific workload varying from 18 to 45 hours35),(36.

The literature recommends experience-based learning, which results in significant practice. According to Shaheen37, in the USA, the learned topics are taught by physicians from different specialties, such as geriatricians, family doctors in home care and clinicians in the wards. However, difficulties in teaching strategies are reported, with reading and discussion tactics in small groups still prevailing.

Regarding the learning scenarios, the integration between teaching-school-community and medical practice was observed in some Brazilian experiences. Considering the studies by Costa et al38, the transformations of students’ representativeness about PC, the time required for rationalization and awareness, and the acquisition of assertive skills such as symptom management, are enhanced by the theoretical reflection associated with the field of practice and interprofessional education.

This knowledge can be used in all areas of the future doctors’ activities and specialties. For Gibbins et al39, the inclusion of PC teaching in undergraduate courses allows the student to develop skills that will improve patient care not only in terms of finitude, but also in general patient care.

According to Carroll et al40, there is a lack of standardization regarding the learning objectives and what should be taught in PC, as well as the fragmentation of teaching and/or its formal absence from the curricula. Different learning strategies can be included during the training of doctors in general PC, and not just as a specialty.

Although PC education in Brazil remains scarce, the data indicate that transformations are taking place in the country. Until 2012, the country officially had 03 schools (2%) with a palliative care discipline in its curriculum. The studies by Oliveira et al7 and Fonseca et al41 showed specific initiatives, albeit successful, in the PC area in some Brazilian schools in the state of Minas Gerais, São Paulo and Rio Grande do Sul. The occurrence of systematized PC teaching in 11 Federation Units and in most regions of Brazil shows the increase in PC teaching in Brazilian schools. According to a survey carried out by the National Academy of Palliative Care in 2017, there has been an increase from 40 PC teams to 123 PC services in the last fifteen years, and new studies are in progress, aiming at getting an update42.

CONCLUSION

This study showed the increase in PC teaching in Brazil, although still insufficient, and a greater concern for the inclusion of a humanist axis, aiming at the acquisition of central competencies in the PC approach. We emphasize the need for this study to unfold into future investigations to assess the successful experiences in the area and the role of different social actors, expanding the knowledge of students’ central roles, the strategies of the teachers involved in the process and the understanding of managers regarding the transformative potential of PC teaching.

Despite being limited to the information contained in the syllabi of the medical school curricular matrices, which are heterogeneous and sometimes reduced, our study reveals that the scarcity of PC teaching represents a barrier to the training of doctors, in agreement with the recommendations of international entities, the National Curriculum Guidelines and legal frameworks within the scope of SUS. The urgency of investments by medical entities and governmental bodies is evidenced for the expansion of PC teaching and the consequent qualification of medical training.

text in

text in