Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Acta Scientiarum. Education

Print version ISSN 2178-5198On-line version ISSN 2178-5201

Acta Educ. vol.46 no.1 Maringá 2024 Epub Dec 01, 2023

https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v46i1.68046

TEACHERS' FORMATION AND PUBLIC POLICY

Democratic culture competences of the council of Europe: how it is interpreted from teacher training

1Departament de Didàctica de la Llengua i la Literatura, i de les Ciències Socials, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Plaça Cívica, 08193, Bellaterra, Barcelona, Espanha.

The interest in building a democratic culture that is increasingly broad and deep is understood as an urgent task. In this regard, educational institutions, teachers, and, as such, the initial training programs offered at universities play a central role in this construction. In the task of building a democratic culture, supranational institutions such as the European Commission and the European Union make continuous efforts to create reference frameworks oriented toward this goal, such as the Competences for Democratic Culture. For this reason, studying the incorporation of these competences into teacher training programs is pertinent and necessary. This article is the result of qualitative research that analyzed how the Competences for Democratic Culture (CDC), proposed by the European Union and the Council of Europe, are reflected in the Primary Education degree program at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. The analysis was conducted following the guidelines of content analysis using the Nvivo software. The analysis shows the existence of a general framework that promotes the incorporation of CDC in the analyzed degree, with a predominance of work on skills and values compared to other types of competences.

Keywords: democracy; values; atitudes; culture; social studies

El interés de construir una cultura democrática que sea cada vez más amplia y profunda se entiende como una tarea urgente. En este sentido, las instituciones educativas, el profesorado y, como tal los programas de formación inicial que se imparten em las universidades tienen un papel central em esta construcción. En la tarea de construcción de una cultura democrática, instituciones supranacionales como la Comisión Europea y la Unión Europea hacen esfuerzos permanentes por construir marcos de referencia orientados a esta tarea, como por ejemplo las Competencias de Cultura Democrática. Por esta razón, estudiar la incorporación de estas competencias en los grados de formación del profesorado es pertinente y necesario. El artículo es el resultado de una investigación cualitativa que analizó de qué manera las Competencias de Cultura Democrática (CDC), propuestas por la Unión Europea y el Consejo de Europa, se encuentran reflejadas en el Grado en Educación Primaria de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. El análisis se realizó siguiendo los lineamientos del análisis de contenido usando el software Nvivo. El análisis muestra la existencia de un marco general que favorece la incorporación de las CDC en el grado analizado, con una preponderancia del trabajo de las habilidades y los valores en comparación con otro tipo de competencias.

Palabras-clave: democracia; valores; actitudes; cultura; ciencias sociales

O interesse em construir uma cultura democrática que seja cada vez mais ampla e profunda é entendido como uma tarefa urgente. Nesse sentido, as instituições educacionais, os professores e, como tal, os programas de formação inicial oferecidos pelas universidades desempenham um papel central nessa construção. Na tarefa de construir uma cultura democrática, instituições supranacionais como a Comissão Europeia e a União Europeia fazem esforços contínuos para criar referenciais orientados para esse objetivo, como as Competências para a Cultura Democrática. Por esse motivo, estudar a incorporação dessas competências nos programas de formação de professores é pertinente e necessário. Este artigo é o resultado de uma pesquisa qualitativa que analisou como as Competências para a Cultura Democrática (CDC), propostas pela União Europeia e pelo Conselho da Europa, são refletidas no curso de Educação Primária da Universidade Autônoma de Barcelona. A análise foi conduzida seguindo as diretrizes da análise de conteúdo utilizando o software Nvivo. A análise mostra a existência de um quadro geral que promove a incorporação das CDC no curso analisado, com predominância do trabalho em habilidades e valores em comparação com outros tipos de competências.

Palavras-chave: democracia; valores; actitudes; cultura; ciencias sociales

Citizenship Education8

In a global context where conflicts, fear, and intolerance towards other cultures are increasing, capital flows freely while individuals fleeing wars are detained at national borders (Gárces, 2016; Massip & Santisteban, 2020). Economic, cultural, and political interdependence is growing, but so are the number of refugees and the inequality both between and within nations. Today more than ever, there is a need for teacher education geared towards social change and the construction of a new citizenship education and democratic culture (González-Valencia & Sanstisteban, 2016; UNESCO, 2018). This raises the question: What are the needs of democratic education in a global context of a crisis of fundamental democratic values? How can we educate for hope in democracy?

Within this context, general education, and citizenship education, in particular, should educate citizens who recognize and understand the issues affecting the democratic system and the social issues present in societies. Therefore, this type of education should be aimed at developing a disposition towards thinking about social reality and acting at both local and global levels in the pursuit of social justice (Westheimer & Kahne, 2004; Pagès & Santisteban, 2008; Spring, 2004). This relates to Lilley, Barker, and Harris's proposal, which indicates that exploring forms of education that allow students to address local and global challenges as socially responsible professionals, with critical and ethical thinking, is consistent with the global citizen (Lilley, Barker, & Harris, 2017, p. 7)9. According to Pagès and Santisteban (2008, p. 3), citizenship education of this kind should aim to develop:

“[...] a set of school knowledge, skills, and values intended to educate young people about what democracy is and to prepare them to assume their roles and responsibilities as citizens of a free, plural, and tolerant society.”

This understanding of citizenship education should help in comprehending the existence of people and human groups with diverse ways of thinking, ideologies, and interests that must coexist, debate, and, if possible, reach agreements, as well as construct a social organization and mechanisms for resolving conflicts (Delanty, 1997; Faulks, 2000; Sant, 2019).

We assume that citizenship transcends the juridical recognition granted by states, represented by the possession of a document certifying a person as a citizen, which does not imply that the associated duties and rights are assumed (González-Valencia, Ballbé, & Ortega-Sanchéz, 2020). Critical citizenship goes beyond legal recognition and mobilizes towards building a better life for individuals and society at large. From this perspective, "[...] the citizen is one who participates directly in public deliberations and decisions, [...] one who seeks to build a good polis, aiming for the common good in their political participation [...]" (Cortina, 2003, p. 43-48), understood as the construction of greater global social justice (Isin & Turner, 2002; Massip & Santisteban, 2020).

Competences for Democratic Culture and Teacher Education

The Council of Europe [CoE] (2018) pointed out in a report on the state of citizenship and human rights in Europe that countries “[...] increased their priority for education related to CE/HRE for teachers and school leaders. However, providing financial support became a much lower priority.” (CoE, 2018, p. 13). This is further clarified when it proposes “[...] Developing new curricula and pedagogical guidance tools and supporting new approaches to teacher education” (CoE, 2018, p. 13). According to the CoE, in times of economic and political crisis, it becomes even more evident that “citizenship must be able to actively participate in the defense of these values and principles and be willing to do so” (CoE, 2018, p. 13). Within this framework, critical citizenship education is posed as:

education, training, awareness, information, practices, and activities that, in addition to providing students with knowledge, competences, and understanding and developing their attitudes and behavior, aspire to give them the means to exercise and defend their democratic rights and responsibilities in society, to value diversity, and to play an active role in democratic life, with the aim of promoting and protecting democracy and the rule of law (CoE, 2018, p. 14).

Competences for democratic culture

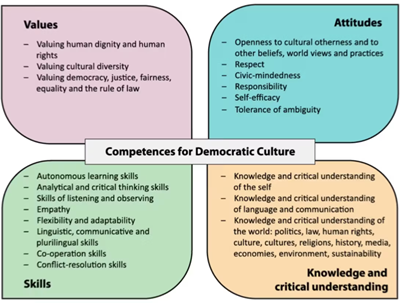

The Council of Europe's (CoE) proposal to solidify the aforementioned concepts is the Competences for Democratic Culture (CDC), which are defined as “[...] the capacity to mobilize and make use of relevant psychological resources (namely, values, attitudes, skills, knowledge, and/or critical understanding) in order to respond effectively and appropriately to the demands, challenges, and opportunities present in democratic contexts.” (CoE, 2018, p. 32). The CDCs are organized into 20 competences divided into 4 groups: a) values, b) attitudes, c) skills, and d) knowledge and critical understanding. The structure and relationships are depicted in Figure 1.

The CoE also deems the development of institutional structures for its promotion crucial, in this case, represented by the initial teacher training programs for primary education conducted by universities. This training phase is most suitable for developing the competencies that allow for the cultivation of democratic culture within educational institutions. Therefore, investigating the level of incorporation of the CDC in teacher training programs is important.

We recognize that developing a democratic culture requires teachers trained to materialize an education oriented towards promoting it (González-Valencia & Sanstisteban, 2016). The CoE suggests that such education:

[...] includes all aspects of life in a democratic society and, therefore, is related to a wide range of topics such as sustainable development, participation in society of people with disabilities, gender perspective integration, terrorism prevention, and many others" (CoE, 2018, p. 79).

According to the CoE (2019, p. 66), achieving adequate development of democratic culture within initial training programs for teaching in primary education requires:

The inclusion of CE/ HRE in pre-service teacher training was considered crucial to reach all future teachers. Research shows that continuous professional development as part of institutional policy is far more effective than one-off training events for individual staff members. The participants addressed the need to provide opportunities for capaçitybuilding across borders, arguing that International co-operation opens up perspectives for addressingboth local needs and global challenges.

For teachers to develop an appropriate Citizenship Education and Human Rights Education, as suggested by the CoE (2017, p. 32), they must possess “[...] clear and practical tools for the daily work of teachers [which] need to be constantly updated and developed in cooperation with a wide range of educational system actors, including teachers, parents, and students.” The ideal scenario for providing preparation and tools are initial training programs, thus the project responded to this need raised by the CoE.

Incorporating competencies for CDC in the initial training of primary education teachers is a strategy that will allow them, when they are carrying out their professional activities, to “[...] to organise classroom relations and communication in ways that strengthen personal commitment and responsibilities and at the same time promote the values of listening, mutual respect and reaching agreements through dialogue” (CoE, 2017, p. 37).

Teacher Education in Spain

The training of primary education teachers in Spain is defined by different public policies corresponding to various scales (European, national, regional, and institutional). The European policies are framed within the process of building the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) that began with the Sorbonne Declaration (1998) and the Lisbon Recognition Convention (Convention on the Recognition of Qualifications..., 1997), and was defined by the Bologna Declaration (1999), which urged EU member states to:

a) achieve comparable degrees through the inclusion of a diploma supplement;

b) design a system based on two cycles, materializing in undergraduate and master's degrees;

c) ECTS credits, which should establish a comparable credit system based on student workload through the clarification of learning objectives, transversal and specific competencies, training activities, and evaluation;

d) the conceptual reformation of the organization of university curriculum based on student-centered learning models;

e) the promotion of student mobility to undertake a period of study abroad; and

f) quality, which has meant the implementation of an internal quality system and a control system.

g) Spain, with the Organic Law 6/2001 on Universities (Congress of Deputies, 2001), assumes in its title XIII the integration into the EHEA.

The EHEA is considered to foster a learning process where the student must take responsibility for organizing and developing their own academic work. The process should focus on self-learning and the student's responsibility regarding their own learning and the need to develop autonomy when learning and facing problems. This entails students participating in the regulation of their educational process and that the objectives and criteria for evaluation are shared and known.

Another significant contribution of the EHEA is competency-based teaching, implying a profound change in the conception of university teaching. This model proposes moving from an activity centered on the teacher to a conception based on the active role of students as protagonists of their own learning process. Thus, it seeks to design a university didactic project oriented towards professional performance and linked with lifelong learning. For this reason, the EHEA context demands a commitment to active methodologies, the promotion of autonomous student learning, innovation, and the development of formative assessment, among other things.

State and regional policies play a role as a normative framework that, due to their general nature, frame the training. Institutional policies, in turn, specify the training in terms of a theoretical proposal, the competencies to be developed, curricular, and internal organization. This can be seen in the documents that were the subject of analysis. From the above, the degree of training of primary education teachers at UAB is inscribed in the following legislative framework:

Organic Law 6/2001 on Universities, which assumes in its Title XIII the integration into the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) (Congress of Deputies, 2001),

Royal Decree 1393/2007 (Ministry of Education and Science, 2007b), of October 29, establishing the organization of official university education (Ministry of Education and Science),

Order ECI/3857/2007 (Ministry of Education and Science, 2007a), of December 27, which sets the requirements for the verification of official university degrees that enable the practice of the profession of Teacher in Primary Education.

And also in the documents specific to the UAB that establish the criteria and general guidelines for the application of degrees:

Academic Regulations of the Autonomous University of Barcelona applicable to university studies regulated in accordance with Royal Decree 1393/2007 (Ministry of Education and Science, 2007b), of October 29, modified by Royal Decree 861/2010, of July 2 (Consolidated text approved by the Agreement of the Governing Council of March 2, 2011).

General criteria and guidelines for evaluation of the Faculty of Education Sciences (Agreement of the Academic Organization Commission of April 28, 2011, of June 4, 2014, and May 28, 2015, Modified by Agreement of the Standing Committee of April 6, 2017 - Autonomous University of Barcelona, 2017).

At the institutional level, the reference document is the Primary Education Degree Report (Autonomous University of Barcelona, 2018), which sets the objective of the degree to provide the competencies and knowledge necessary to practice the teaching profession for the 6 to 12-year age group in compulsory education. This degree offers a generalist education with the possibility to choose among four specialties: Foreign Languages, Physical Education, Music Education, and Specific Educational Needs. The structure of the curriculum (240 ECTS) is presented in the following Table 1.

Methodology and research design

The research aimed to identify whether the dimensions of the competences for democratic culture are reflected in the public policy documents related to initial teacher training. The study was qualitative. Data were analyzed independently by two researchers. To ensure inter-coder reliability, both researchers coded one policy document and discussed emerging discrepancies. For each document, data were divided into sentences using a syntactic sampling strategy (Krippendorff, 2004). Each sentence was considered a unit of analysis. Codes were assigned to sentences identifying the presence/absence of each code within each sentence. We then calculated the relative frequency of each code (i.e., the number of code occurrences in the source relative to the total number of sentences in the complete source [fi = ni/N]). While acknowledging that this method leads to an oversimplification of variance, we deemed it suitable for summarizing and comparing our data. NVivo V.11 software was used for the analysis process.

Sample

To conduct our analysis of relevant policies, we first sought institutional policies framing initial teacher training at the university for primary education teachers that met five distinctive criteria:

Timeframe: We only considered institutional policies in force as of January 2021. For cumulative policies, only the most recent were considered.

Place of application: Policies in force at the university were considered.

Focus: We only considered policies that could be directly or indirectly connected to the Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture as designed by the CoE (2018).

Our search concluded by identifying the following two public policy documents:

Primary Education Degree Report. This document contains the theoretical and public policy approaches defining the training, as well as administrative aspects (n.d.),

Teaching guides for primary education degree courses at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (2021). These documents contain, in detail, the design of the courses: objectives, competencies, concepts/topics, methodology, and evaluation.

Findings

The training to teach primary education in Spain is defined by state, regional, and institutional policies. In broad and general terms, after analysis, it can be asserted that the policies analyzed do contain explicit references to CDCs. However, it is interesting to note that these references are mainly found in the preambles of normative documents for state-level policies, and in the description of subjects for institutional policies.

Thus, the references in state and regional policies are more like statements of intent that establish a framework suggesting alignment with education for democratic culture, but lacking details on how these competencies will be implemented. In other words, more importance is given to the what and why, and to a lesser extent, the how, or implementation, although in the teaching guides, it is possible to identify advances in the how. In the future, it would be interesting to perform a more detailed study of what happens in the classrooms.

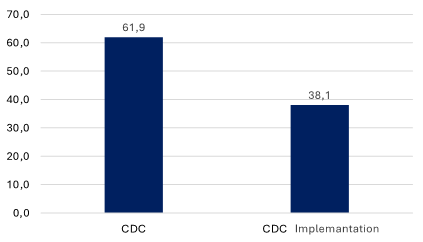

In the Primary Education Degree Report and the guides, numerous explicit references to CDCs (61.9%) and their implementation (38.1%) were found (Figure 2). The higher density of references is due to these documents (Report and Teaching Guides) addressing both normative (competencies) and conceptual (training and its components) aspects comprehensively. Several of these documents address aspects related to social and human sciences, in which approaches close to democratic culture can be found. It is important to note that the quantity and extent of documents are much more numerous than the previous ones, hence their high number of references.

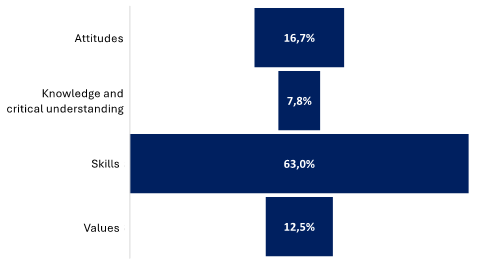

When analyzing each group of CDC competencies, it was found that explicit references tend to fundamentally privilege skills (63%) (Figure 3). This is due to the importance these hold in the current discourse on competencies. A more precise explanation might be that there is an emphasis on the skills a teacher must possess to develop their professional activity and that, for this reason, they are privileged in initial training.

Upon closer examination of the findings (Table 2), we see that the most worked and frequently appearing skills are: communicative, linguistic, and multilingual skills; cooperation skills; skills for autonomous learning; and critical and analytical thinking skills. In general terms, we can say that what was found in internal policies allows for a direct relationship with the framework of competences for democratic culture, facilitating their explicit incorporation in the initial training of primary education teachers.

Table 2 References to CDC in Institutional Policies.

| Attitudes | 16,7 |

| Civic-mindedness | 1,3 |

| Openness to cultural otherness and to different beliefs, worldviews, and practices | 4,4 |

| Respect | 4,2 |

| Responsibility | 1,0 |

| Self-efficacy | 5,7 |

| Tolerance for ambiguity | 0,0 |

| Knowledge and critical undestanding | 7,8 |

| Knowledge and critical understanding of language and comunication | 1,6 |

| Knowledge and critical understanding of the self | 0,5 |

| Knowledge and critical understanding of the world | 5,7 |

| Skills | 63,0 |

| Analytical and critical thinking skills | 10,9 |

| Skills for autonomous learning | 12,2 |

| Conflict resolution | 6,0 |

| Cooperative skills | 14,6 |

| Empathy | 0,5 |

| Flexibility and adaptability | 0,8 |

| Linguistic, communicative, and plurilingual competences | 17,4 |

| Listening and observation skills | 0,5 |

| Values | 12,5 |

| Cultural diversity | 3,9 |

| Human dignity and human rights | 5,5 |

| Valuing democracy, justice, equity, equality, and the rule of law | 3,1 |

It makes sense that these are the most worked skills in the classrooms if we consider that the primary education curriculum has been competency-based since 2006, and also considering the bilingual reality of Catalonia, and consequently the emphasis placed on communicative skills both in the curriculum and in the Education law. On the other hand, Table 2 also shows some omissions, such as work around ambiguity, critical self-knowledge, or the minimal presence of skills such as empathy, flexibility and adaptability, or responsibility.

To continue the analysis, it is intriguing to examine which subjects, among all those offered in the degree, contain references to CDCs. Within the mandatory subject area, there are minimal direct references linked to CDCs. The exception is found in various subjects within the social studies domain, such as “Let's Look at the World: Interdisciplinary Projects”, “Education and Social Sciences”, “Teaching and Learning of Natural, Social, and Cultural Environment”, and “Didactics of Social Sciences”. This slightly contradicts the findings in the section on state policies, where a normative and competency framework highly favorable to the inclusion of CDCs in all primary degree subjects is clearly established.

However, the situation changes when we look at elective subjects, especially those that are part of the Social Sciences Mention, where the intentionality and statements of purpose-which have a direct relationship with CDCs-materialize in subjects such as: “Teaching Social Sciences with a Gender Perspective”, “Research and Innovation in Social Studies”, “Current Events in Social Sciences in Primary Education: Critical Thinking Education”. Outside of the Social Sciences Mention, we find subjects like “Education for Global Justice”, “Education, Sustainability and Consumption”, “Education and Democratic Participation”, or “Mediation Strategies”, which also extensively work with contents and competencies related to CDCs. All these subjects have a direct relationship with the human and social sciences.

However, when we scrutinize the contents, objectives, and evaluation criteria of these subjects, we encounter very little specificity. For example, in the subject “Let's Look at the World: Interdisciplinary Project”, it is specified that the curricular contents of the subject will be “Ethics, Values, and Educatio”, “The Global World System”, or “Planet, Resources, and Sustainability”, among others. But it doesn’t elaborate much further than this.

Regarding the implementation of CDCs, it was found that most references are found in evaluation (54.7%), teaching methods (32.6%), and the Whole School Approach (12.7%) (Table 3). These strategies are some of the most commonly used in competency-based work approaches. Conversely, we found very few references to other types of tools or evaluation approaches such as observation-based evaluation, external evaluations, or project-based evaluations. This is surprising considering that the project-based learning category is also one of the most referenced.

Table 3 References to the Implementation of CDC in Institutional Policies.

| CDC Implementation | % |

| Assessment | 54,7 |

| Dynamic assessment | 5,1 |

| Assessment by Observation | 4,2 |

| Observation Journals | 11,9 |

| Learning Portfolio | 32,2 |

| Project-Based Assessment | 0,8 |

| Teaching methods | 32,6 |

| Cooperative Learning | 7,6 |

| Democratic Processes in the Classroom | 2,5 |

| Modeling Democratic Attitudes and Behaviors | 5,1 |

| Project-Based Learning | 14,0 |

| Service Learning | 2,1 |

| Whole School Approach | 12,7 |

| Community Collaboration | 6,4 |

| Non-discriminatory Policies | 1,3 |

| Family Participation | 3,0 |

| Participative Structures for Decision Making | 0,0 |

| School Collaboration | 2,1 |

| Student participation | 0,0 |

In classroom methodologies, project-based learning (PBL) stands out, representing 14%. Intriguingly, while state and regional policies rarely refer to this type of work, explicit and concrete references are found in teaching guides and degree reports. However, it must be mentioned that although PBL is considered within the CDC's reference framework as one form of implementation, in practice it extends further, fitting into a context of pedagogical renewal where this class type is a current educational benchmark.

Subjects utilizing projects detail them thoroughly in teaching guides, as with the Transnatura project conducted interdisciplinarily in the third year. The first-year mandatory subject “Let's Look at the World: Transdisciplinary Projects” exemplifies the use of project methodology in a degree course and how it excellently facilitates the work and implementation of democratic culture competences.

In the Transnatura project, teaching teams from third-year mandatory subjects such as Natural, Social, and Cultural Environment Teaching, Experimental Science Didactics, Learning and Development I, Visual Musical Education, and Physical Education and its Didactics I, organize a cross-curricular, multidisciplinary project culminating in a two-day nature trip con with the aim of:

Providing an intense, educational experience in the natural environment. Apart from working on specific objectives from each discipline, it also addresses cross-cutting aspects like sustainability, healthy living, coexistence, and the relationship between school and nature, among others (Autonomous University of Barcelona, 2021, Teaching Guide).

Such strategies allow for an interdisciplinary approach and direct contact with the social environment, undoubtedly an excellent opportunity for developing CDC.

In the Social Science Didactics course, students design a teaching unit around a social issue. During the design process, they must search for and analyze information related to the problem and build a teaching proposal for a specific primary education year during their professional internships. Here, students build relationships with the primary education curriculum and concepts such as critical thinking, historical time and thought, geographical space, gender perspective, and citizenship and politics. Such proposals represent one of the best opportunities to include democratic culture competences because students go through the full journey from theory to actual practice in schools.

Another interesting subject is the first-year mandatory course “Let's Look at the World: Transdisciplinary Projects”. One of the 6 projects throughout the course revolves around democracy and authoritarianism, linking CDC work with methodologies that facilitate its approach. This project aims to answer the question: “Is democracy in danger?” and challenges students to create an electoral rally where a political action program is argued and defended from any ideological option. Throughout the project, students address questions like: “Is democracy at risk? Why are so many people attracted to 'hard' and simple answers to complex problems?” The goal is to understand the reasons for this drift, reflect on psychological methodologies, and promote students' analytical abilities with a global view of current society (Autonomous University of Barcelona, 2021, Teaching Guide).

This kind of work could foster values education included in the CDC theoretical framework, such as valuing democracy, justice, equity, equality, and the rule of law, based on the widespread belief that societies should be governed by democratic processes respecting principles of justice, equity, equality, and the rule of law.

Despite the above, it's important to remember that the most utilized methodology in primary degree subjects is still the lecture. The proposed subjects are exceptions, raising the question of whether this methodology is most suitable for making CDC work a reality in university classrooms where future primary education teachers are trained.

Conclusion

Teacher training for primary education in Spain is defined by state, regional, and institutional policies. Broadly speaking, after analysis, it can be affirmed that public policies do explicitly refer to CDC and their framework. However, it’s fascinating to see that these references are primarily found in the preambles of normative documents for state-level policies and in the description of subjects for institutional policies. This approach is framed within a deliberative and participatory perspective (Sant, 2019; Kymlicka & Norman, 1997) of democracy education, worth noting as one of the most widespread in liberal and Western democracies.

In the degree-related documents (Reports and Teaching Guides), a higher number of references and specifications were found, allowing a direct connection with CDC. This connection is made more concrete in subjects related to human and social sciences. It’s relevant to point out that the existing interdisciplinary approach can facilitate the inclusion of CDC.

In the analyzed documents, competencies, especially skills, are emphasized across all policy scales (state, regional, and institutional), possibly due to the current prominence of skills in the discourse on competences. This is consistent with the CDC approach and the public policy documents defining initial training.

Primary education degrees are regulated through competencies, which facilitates the inclusion of CDC throughout the process. However, it will be necessary to review some aspects related to knowledge and critical understanding since this competence group has the fewest references, suggesting difficulties in incorporating these CDC aspects into the degree. The existing references concerning the critical aspect focus on a psychological perspective (González-Valencia & Puente, 2018), sidelining the approaches from a social and political perspective.

In institutional policies - Reports and Teaching Guides - social science subjects are found where a high number of references to CDC and conceptual axes are observed. Undoubtedly, these are the subjects that allow for a direct relationship with CDC in their conception and implementation. Subjects such as Teaching of the Natural, Social, and Cultural Environment, Didactics of Social Sciences, Citizenship Education, and Teaching of Social Sciences with a Gender Perspective are ideal for the incorporation of CDC. This raises the question: what can be done within subjects that address aspects of teaching natural sciences?

Methodologically, in the Degree Reports and Teaching Guides, there are numerous references to project-based work, shaping a pedagogical and didactic context favorable for the incorporation of CDC. This is posed as a possibility, but it raises the question: is this relationship truly materialized in teaching practices? The answer to this question can come from a deep understanding of the practices and resources used by the faculty in the degree program, which is one of the activities of the project that gave rise to this article. From the collection of information on practices and resources, we can say they are diverse and favor the realization of CDC in initial training. However, it is pertinent to note that the lecture remains the most frequent model in university classrooms. Is it the most appropriate for introducing CDC?

In conclusion, it can be said that there is a favorable regulatory framework at all levels for introducing CDC in the Primary Education Degree. Public policies anticipate this. But does this regulatory framework actually translate into classrooms and practices? This is a question that remains open for future research, in which progress could be made on teacher training and innovation projects with the faculty responsible for educationg the educators.

Finally, the normative competence context present in all public policies undoubtedly shapes a suitable environment for advancing CDC training in future teachers. The task remains to investigate how these competences are transferred into practice and to research what really happens in university classrooms and how we can effect changes and improve the training of primary education teachers, to make the knowledge and practice of democratic culture a reality, or at least a possibility in the near future.

REFERENCES

Andreotti, V. (2006). Soft versus critical global citizenship education. Policy & Practice-A Development, 3, 40-51. [ Links ]

Congres de los Diputados. (2001). Ley Orgánica 6/2002, de 27 de junio, de Partidos Políticos. Madrid, ES: Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado. [ Links ]

Consejo de Europa [CoE]. (2018). Marco de referencia de las competencias para una cultura democrática (Volumen 1. Contexto, conceptos y modelo). Estrasburgo, FR: Concejo de Europa. [ Links ]

Convenio sobre Reconocimiento de Cualificaciones relativas a la Educación Superior en la Región Europea. (1997, 11 de abril). Lisboa. Recuperado de https://bitlybr.com/Cfp [ Links ]

Cortina, A. (2003). Ciudadanos del mundo: hacia una teoría de la ciudadanía (3. reimpr.). Madrid, ES: Alianza. [ Links ]

Council of Europe. (2019). Learning to live together. Council of Europe report on the state of citizenship and human rights education in Europe. In accordance with the objectives and principles of the Council of Europe Charter on Education for Democratic Citizenship and Human Rights Education. Strasbourg, FR: Council of Europe. [ Links ]

Council of the Europe. (2017). Learning to live together. Council of Europe Report on the state of citizenship and human rights education in Europe. Strasbourg, FR: Council of Europe [ Links ]

Declaración de Bolonia. (1999). Declaración de Bolonia. Recuperado de http://www.educacion.gob.es/boloniaensecundaria/img/Declaracion_Bolonia.pdf [ Links ]

Declaración de La Sorbona. (1998). París, 25 de mayo de 1998. Recuperado em 19/10/2022 de Recuperado em 19/10/2022 de http://www.eees.ua.es/documentos/declaracion_sorbona.htm [ Links ]

Delanty, G. (1997). Models of citizenship: defining european identity and citizenship. Citizenship Studies, 1(3), 285-303. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13621029708420660 [ Links ]

Faulks, K. (2000). Citizenship. London, GB: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gárces, M. (2016). Fuera de clase: textos de filosofía de guerrilla. Barcelona, ES: Galaxia Gutenberg. [ Links ]

González-Valencia, G. A., & Morillo, S. (2018). Representaciones sobre el desarrollo del pensamiento crítico en maestros en formación. Revista Brasilera de Educação, 23, e230086. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782018230086 [ Links ]

González-Valencia, G. A., & Santisteban, A. S. (2016). La formación ciudadana en la educación obligatoria en Colombia: entre la tradición y la transformación. Educación Y Educadores, 19(1), 89-102 [ Links ]

González-Valencia, G. A., Martínez, M. B., & Ortega-Sanchéz, D. (2020). Global citizenship and analysis of social facts: results of a study with pre-service teachers. Social Sciences, 9, 65-84. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9050065 [ Links ]

Isin, E. F., & Turner, B. S. (2002). Handbook of citizenship studies. London, GB: Sage. [ Links ]

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology (2nd ed.). London, GB: Sage. [ Links ]

Kymlicka, W., Norman, W. (1997). El retorno del ciudadano. Una revisión de la producción reciente en teoría de la ciudadanía en la política. La política: revista de estudios sobre Estado y la Sociedad (Ciudadanía: el debate contemporáneo), 3, 5-40. [ Links ]

Lilley, K., Barker, M., & Harris, N. (2017) The global citizen conceptualized: accommodating ambiguity. Journal of Studies in International Education, 21(1), 6-21. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315316637354 [ Links ]

Massip, M., & Santisteban, A. S. (2020). A educação para a cidadania democrática na Europa. Revista Espaço do Currículo, 13(2), 142-152. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22478/ufpb.1983-1579.2020v13n2.51513 [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia. (2007a). Orden ECI/3857/2007, de 27 de diciembre, por la que se establecen los requisitos para la verificación de los títulos universitarios oficiales que habiliten para el ejercicio de la profesión de Maestro en Educación Primaria. Madrid, ES: Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia. (2007b). Real Decreto 1393/2007, de 29 de octubre, por el que se establece la ordenación de las enseñanzas universitarias oficiales. Madrid, ES: Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado. [ Links ]

Pagès, J., & Santisteban, A. S. (2008). La educación para la ciudadanía hoy. Wolters Kluwer. Recuperado de https://www.academia.edu/33752984/La_Educaci%C3%B3n_para_la_Ciudadan%C3%ADa_hoy_1 [ Links ]

Sant, E. (2019). Democratic education: a theoretical review (2006-2017). Review of Educational Research, 89(5), 655-696. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319862493 [ Links ]

Spring, J. (2004). How educational ideologies are shaping global society. Mahwah, NJ: LEA. [ Links ]

Unesco. (2018). Preparing teachers for global citizenship education: a template. Bangkok: Unesco Digital Library. [ Links ]

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. (2017). Acta de la Junta Permanent de 6 d’abril de 2017. Recuperado de https://www.uab.cat/servlet/BlobServer?blobtable=Document&blobcol=urldocument&blobheader=application/pdf&blobkey=id&blobwhere=1345763740920&blobnocache=true [ Links ]

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. (2018). Grado de educación primaria. Recuperado de https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/memtit/2009/149661/MemoriaWebGrauEdPrimaria_042018.pdf [ Links ]

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. (2021). Guías docentes de las asignaturas. Recuperado de https://www.uab.cat/web/estudiar/listado-de-grados/plan-de-estudios/guias-docentes/educacion-primaria-1345467893062.html?param1=1229413437355 [ Links ]

Westheimer, J., & Kahne, J. (2004). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. American Educational Research Journal, 41(2), 237-269. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312041002237 [ Links ]

8Este artículo es resultado del proyecto Embedding a Democratic Culture Dimension in Teacher Education Programmes (EDCD-TEP). Financiado por el Consejo de Europa y la Unión Europea a través del programa Democratic and Inclusive School Culture in Operation (Disco)

9“[…] to explore forms of education that enable learners to address local and global challenges, as socially responsible, critical and ethical thinking graduates, a disposition consistent with the global citizen” (Lilley, Barker, & Harris, 2017, p. 7).

18NOTA: Gustavo González Valencia. He was part of the research team. He participated in the design, fieldwork, information analysis, and article writing. Neus González-Monfort. She was part of the research team. She participated in the design, fieldwork, information analysis, and article writing. Núria Aris Redó. She contributed to the information analysis and article writing. Antoni Santisteban Fernández. He was part of the research team. He participated in the design, fieldwork, information analysis, and article writing.

4The inclusion of EDC/ HRE in pre-service teacher training was considered crucial to reach all future teachers. Research shows that continuous professional development as part of institutional policy is far more effective than one-off training events for individual staff members. The participants addressed the need to provide opportunities for capaçitybuilding across borders, arguing that International co-operation opens up perspectives for addressingboth local needs and global challenges.

5[...] clear and practical tools for teachers’ everyday work need to be continuously updated and developed in co-operation with the wide array of actors in the educational system, including teachers, parents and students”

6[...] to organise classroom relations and communication in ways that strengthen personal commitment and responsibilities and at the same time promote the values of listening, mutual respect and reaching agreements through dialogue (Council of Europe, 2017, p. 37).

Received: April 29, 2023; Accepted: October 03, 2023

text in

text in