a practical look at the concept of freedom with a philosophy approach for children in early childhood2

introduction

Value is a criterion with cognitive and affective dimensions that express desired behavior and lifestyle. They guide individuals' lives when they act, make decisions, or evaluate others and themselves (Rokeach, 1979). Values enable individuals to solve the problems they encounter in their lives. They have their roots in society's traditions and past and are still relevant today (MEB, 2018). At the same time, however, these values cannot be attributed to only one society. From this point of view, it is possible to speak of national and universal values. They are called national and universal values, which depend on the ideas of different societies and nations. National values are values that refer to specific nations and express the feelings of that nation. Universal values are the values that concern the whole world and humanity (Ercan, 2001). Justice, freedom, respect for people, honesty, hard work, etc. values (Doğan, 2001) can be described as universal values. However, values are not inherited, but the individual acquires them in their life; they determine their personality, outlook, and direction of behavior. Therefore, they must know their specific values and produce, adapt, and display new ones (Yeşil & Aydın, 2007).

Social studies accomplish this task by preparing children to assume their civic responsibilities and providing them with knowledge, skills, behaviors, and values consistent with democratic living (Seefeldt, Castle, & Falconer, 2015). Values in schools are taught to students through curricula. The values taught to the students differ each semester, depending on the society's development rate. While the values to be acquired by students in the social studies program before 1980 were responsibility, cooperation, and sensitivity, after 1980, these values changed to loyalty to Atatürk nationalism, sensitivity (Turkish history and culture), patriotism, independence, the importance of family values, respect, cleanliness, solidarity, hard work, etc. With the new values education program published in 2004, a smaller emphasis was placed on multiculturalism (Keskin, 2008). This difference in values also shows itself from society to society. They differ in each society depending on the importance attached to the value and the acceptance of the value (Schwartz, 1992). This situation leads to the fact that the values in the countries' curricula differ. For example, while "giving importance to family unity, hospitality, cleanliness" is an essential value in the social studies curriculum in Turkey, “kind-heartedness, compassion” is another value emphasized in New Zealand (Ekşi & Katılmış, 2011). Based on this difference, the Social Studies Curriculum (2018) of the Ministry of National Education of the Republic of Turkey lists a total of 18 values, including national and universal values: importance to family unity[1], fairness, independence, peace, freedom, scientificity, diligence, solidarity, sensitivity, honesty, aesthetics, tolerance, hospitality, the importance of health, respect, love, responsibility, cleanliness, patriotism, and helpfulness (MEB, 2018). The concept of “freedom”, which is one of these values, is a concept that has accompanied humanity throughout history and has been frequently emphasized by philosophers. Freedom was a reason and an indispensable condition for every individual and social action. This situation allowed philosophy to address the problem of freedom (Adugit, 2013), and the nature and limits of freedom were discussed. Socrates linked freedom to knowledge, but Plato said freedom is only possible for virtuous individuals who act according to their will (Töle, 2005). Aristotle defined freedom as the ability to choose and act freely and consciously (Adugit, 2013), while Montesquieu defined it as the right to do what the rules allow (Timuçin, 2002).

On the other hand, Rousseau stated that man, who is free and equal in the natural state, loses this freedom and equality with social life (Rousseau, 2004). Philosophy for Children addressed questions about freedom in general within the framework of “what freedom is, where its limits lie, how rules and obligations affect freedom, the relationship between freedom and responsibility” (Direk, 2015) and included discussions with children. These discussions were led by Matthew Lipman (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, 2007, p. 3), who promoted the idea that children can understand philosophical questions and think abstractly at an early age; it has been implemented in many countries. Lipman wrote his novel, “Harry Stottlemeier's Discovery”, and held his first applied philosophy class in the fifth grade (Brandt, 1988, p. 34). Thus, instead of teaching philosophy to children, he aimed to develop children's thinking, questioning, and reasoning skills through inquiry. Instead of teaching a specific philosophical doctrine, he worked with universal concepts such as law, justice, and even violence, empowering the child to think and question for himself (UNESCO, 2007, p. 3). Within this framework, philosophy for children is a teaching style that aims to bring philosophy together with children at an early age (Tepe, 2013); it allows for dialogue and questioning between children and teachers, children and children, and thus aims to develop critical and creative thinking (Fisher, 2013). Philosophy for Children rejects memorization and teaches children to judge based on evidence and reason rather than memorization (Marashi, 2008). For this purpose, Lipman, the founder of the Philosophy for Children approach, conducted discussion sessions based on questions and mutual dialogue. In the sessions, children are read a novel that contains ambiguities and contradictions; a session leader with theoretical knowledge of philosophy and logic takes children's questions about situations they want to discuss with their peers and that interest them and ensures that these questions are discussed (Daniel & Auric, 2011; McCall, 2017). In Lipman's approach to philosophy for children, the story is the foundational material. However, a poem, song, or newspaper article can provide another source for discussion.

Lipman's work led to the emergence of the “Philosophy for Children” (P4C) approach (Altıparmak, 2016). Lipman and Ann Margaret Sharp founded the Institute for the Advancement of Philosophy for Children (IAPC). To implement the “philosophy for children” approach, he wrote novels for students, handbooks, and guides for teachers.

Lipman's theory originated as a rebellion against the education circle of the 1970s, particularly Piaget's well-known and widely accepted view that "children cannot think abstractly" before the age of 11-12. Children who participated in Lipman's program showed high achievement in thinking and creativity (Pohoata, 2013, p. 8). For this reason, this trend started by Lipman has spread to many countries worldwide, including America and Europe (Germany, Denmark, Austria, and Canada). Besides Matthew Lipman, many names such as Gareth Matthews, Thomas Wartenberg, Karin Muris, Catherine McCall, and David Kennedy have worked in the field of philosophy for children; new methods, new approaches, and generations have emerged (Valitalo, Juuso, & Sutinen, 2016).

Both theoretical and practical studies on the philosophical approach to children have been carried out in the United States and Europe. Studies on this topic have been at the preschool, elementary, and secondary levels. Studies have been conducted with educators (e.g., creating handbook effects of training on thinking skills). In terms of content, the focus was on the necessity of philosophy (Lipman, Sharp ve Oscanyan 1977), the effect of philosophy for on children thinking skills, literacy, language skills, and academic achievement (Daniel, Gagnon ve Pettier, 2012; Lam, 2012; Säre, Luik ve Tulviste, 2016), the elements shaping philosophy for children (Vansieleghem ve Kennedy, 2011), the nature of philosophy for children (Fisher, 2013); implementation of this approach in programs, difficulties in implementation, children's competences in the philosophy of children (Murris, 2000), the changing perspectives towards philosophy for children (2 different generations) and the approach is considered in a broad perspective. In Turkey, it was found that the importance of philosophy for children has been recognized only recently, and the studies conducted are limited in content and level. However, it was determined that the studies conducted in preschool education program, followed by the values of respect, solidarity, trust, and love; tolerance, freedom, equality, friendship, and justice are hardly included in the learning outcomes and indicators. Karakuş (2015), on the other hand, studied the values in the cartoon Niloya, which is aimed at preschool children, and found that the values of “love, tolerance, sensitivity, and kindness” are emphasized most frequently, followed by the values of “hard work, solidarity, respect, responsibility, and benevolence”, and that the values of “honesty and freedom” are prevalent in the cartoon. Orhan (2021) analyzed 80 preschool children's books regarding values and found that the value of freedom was mentioned 41 times in only 26 of 80 books. Aktan and Padem (2013) investigated the values in the reading texts in the primary school 5th-grade social studies textbook. Accordingly, the most common values in the texts are peace, success, solidarity, love, commitment, and sensitivity, and the least common values are being open-minded, giving importance to family unity, reliability, idealistic, national unity consciousness, kindness, freedom, and self-confidence. Values are patience, cleanliness, and openness to innovations. As a result, freedom is mentioned as a virtue in both social studies and preschool programs. However, the philosophical view is ignored, and there is no debate about it in social studies classes. It is assumed that the concept of freedom in preschool is abstract and that children cannot think in abstract terms. Moreover, the studies on the values remain at the level of determining the frequencies of the values. Discussions about the nature of values are not entered into. However, with the philosophy for children approach, children gain many values. Mehdiyev and Tozduman-Yaralı (2020) state that philosophy education for children positively affects children's behavior towards human values (happiness, freedom, justice, right, beauty, and ugliness). With this in mind, this study sought answers to the following questions:

method

the research model

The study used a qualitative experimental approach to determine if there was a difference in the children's views before and after the application. Qualitative experimentation is the exploratory, heuristic form of experimentation. It is an intervention in a social and psychological situation using scientific criteria to explore its structure (Kleining, 1986). In this qualitative experimental intervention into the phenomenon, changes are made in its natural environment to reveal its structure (Mayring, 2011). Qualitative experimentation allows observing communication processes and responses to phenomena in different environments (Robinson, Mendolson, 2012; Naber, 2015). In addition, it allows researchers to identify the hidden structure of the process by creating dynamics in the field and exploring and finding solutions to the problem (Naber, 2015). The phases of qualitative experimental design are the characterization of the phenomenon, experimental intervention, redescription of the phenomenon, and concluding the structure of the phenomenon (Mayring, 2011). According to Kleining (1986), individuals, communities, and social systems can be factually or cognitively transformed in qualitative experiments: (a) partitioning/separation (the phenomenon is subdivided and observed) (b) combination (used in problem-solving experiments to capture the structure of small groups; the phenomenon is put together differently; differences, inconsistencies, contradictions are observed) (c) attenuation/reduction (which part is essential in the case, some elements are reduced or removed from the case to determine this) (d) adjectivization/condensation (used, e.g.., in perception experiments, group cohesion experiments, stress studies; the change in the phenomenon occurs either by adding a new part or by reinforcing an existing part) (e) substitution (imaginary or actual functions, actions, properties, social positions. The goal is to determine whether significant changes can occur with small shifts) and (f) transformation (transformation of all constructs of social functions, roles, attitudes found empirically under different conditions). In this study, the substitution of qualitative experimental techniques was used. Thus, the effect of location changes in the case was determined.

research study group

The study research group included 19 children (14 boys, 5 girls) aged 5-6 years. The program continued as planned when a child could not participate for various reasons. Thus, 15 children participated in the preliminary application and 12 in the final application. Participants were selected based on “readily available case studies” A situation was chosen that was close and easily accessible in order to conduct the research quickly and practically (Yıldırım & Şimşek, 2013).

instruments and process of data collection

Semi-structured interviews and document analysis were used to collect data because the study group was 5-6 years old and illiterate. In the semi-structured interview, the interview sheet is structured (planned and specific questions to be asked) and prepared in a semi-structured way. It also considers the interviewer's responses during the interview, and the form is designed to be adaptable (Cemaloğlu, 2009). During implementation, the semi-structured interviews were conducted with the children individually and in groups. Individual interviews are those in which only the interviewee and the interviewees are present. Group interviews are interviews in which a topic is discussed with a large group. Group members respond interactively to the interviewer's questions and listen to each other and discuss their perspectives (Karasar, 1998). Group discussions encouraged children to express their thoughts openly, listen to each other, and contribute new and different ideas. Individual interviews were also used to gather additional data from the children (especially for picture-based activities). The interviews attempted to find out how the children perceive freedom, for what reasons they conceptualize it in specific ways, and in what situations they think they are free; a total of 3 interviews were conducted for this purpose.

Another data collection tool is document analysis, which uses books, diaries, films, and videos to obtain information about the event or phenomenon under study. It involves the study of textual or visual information, such as (Yıldırım & Şimşek, 2013). Image analysis was used as a research document; 27 photographs were analyzed. Children's discourses were analyzed using coding. Thus, the children were coded based on their gender and the first letters of their first and last names. The children's middle names were also included in the code. For example, the extension of the KMO code may be as follows: the girl (gender), Melisa (name), and Osmanoğlu (last name).

In the study, a total of three activities, namely “Freedom… is similar to. Because…”, “…am I free?” and “Rapunzel story activity”. “Freedom is similar to …, because…” was analyzed under the categories of “justification” (J); “… am I free?” was analyzed under the categories of “decision making” (DM) and “justification” (J); and “Rapunzel story activity” was analyzed under the categories of “justification” (J), “question generation” (QG), “questioning” (Q), and “idea generation” (IG). Because in the context of the philosophy for children approach, it was tried to ensure that the child produces questions, explains his/her views with justifications, produces ideas, and questions the ideas produced. The basis of philosophy for children is critical thinking. Critical thinking includes asking questions, agreeing or disagreeing, stating reasons, generalizing, giving examples, classifying, comparing, defining, inferring, making assumptions, and expressing one's opinion in one's own words (Kennedy, 2013). In the activities carried out for this purpose, in addition to the story activity that forms the basis of Lipman's approach to philosophy for children, activities were included to show the nature of the concept of Freedom and enable them to think about it. First, pre-applications and post-applications were conducted to determine the children's conceptions of freedom. In the pre-application, children were asked to do the activity “Freedom is similar to…, because…”; their opinions about the concept of Freedom were recorded, and an attempt was made to show their opinions with their reasons. After the pre-application, an activity titled “… am I free?” was applied to the children who were asked to make a choice (decision-making) about which situations they are free to do or not do and to express this with a reason (justification/reasoning). In the “Rapunzel story activity”, the children were made to watch an episode about freedom; they were asked to ask questions about the story in the context of philosophy (question generation), to generate ideas and present them with their justifications (idea generation and justification/reasoning), to criticize and evaluate their friends' opinions (questioning), and to discuss them. In the last exercise, the “Freedom is similar to…, because…” activity was repeated with the children.

data analysis

Miles and Huberman describe the process of data analysis in three parts: Data processing (data reduction), data visualization (data presentation), decision making and its confirmation (Yıldırım & Şimşek, 2013). The researcher first reviews and codes the data in the data processing stage. When coding the data, concepts, and themes relevant to the research subject are used. The data are summarized, and key data are selected in this way. For example, “I am not free” is a theme in the children's talk about freedom, while rules are necessary, permission is sought, things are done secretly, authority is obeyed, and so on.

The data set, which was relatively simple and appropriate to the research problem in the first phase, is visualized with various charts, tables, and figures in the data presentation phase. This visualization allows for a better understanding of the connection between concepts and themes. The emerging concepts, themes, and relationships are understood, compared, and validated in the final phase. In this way, it is possible to understand the study's results and confirm their validity.

Based on these steps, the children's utterances were examined individually during the data analysis, these utterances were analyzed, and the themes were recorded with the code to make the data more meaningful. Therefore, descriptive and content analysis were used in analyzing the data. Descriptive analysis is concerned with presenting the reader with the findings obtained from the research in an organized and interpreted form. Therefore, the themes are determined in advance, the data are summarized according to these themes, and the result is obtained by interpretation within the framework of a cause-effect relationship (Yıldırım & Şimşek, 2013). Therefore, a frequency table was created in the study by considering the students' discourses about freedom and the levels of the questions they asked. The frequency table shows the repetitions of the individual data collected separately and not processed (Karasar, 1998, p. 209).

validity and reliability

Expert opinions were sought on all interpretations, explanations, coding, and questions related to the study, and data diversity (interview, document) was established to ensure the credibility of the research. Regarding transferability/transferability (external validity), all data were described in detail and communicated to the reader. For this purpose, direct quotes about the discourses received from the participants were included in the study. For consistency (internal reliability), the data were coded and checked for consistency by two researchers. For this purpose, Miles & Huberman's (1994) reliability formula was used (Reliability = Consensus / (Consensus + Disagreement)). This technique primarily concerns whether coders use similar codes for the same data. In this framework, the agreement rate between coders is 90%. Finally, confirmability (external reliability) was ensured by comparing the results with the raw data.

findings

The findings of the study were revealed by describing the data obtained within the framework of “Freedom is similar to…, because…” “…am I free?” and “Rapunzel story activity.” The metaphor activity “Freedom is similar to…, because…” was applied to the children twice as both the first and the last application. In this direction, after the first application, “…am I free?” and “Rapunzel story activities” were performed, and then the metaphor activity was repeated. Explanations about the activities and detailed explanations of the findings are given below.

the results of the “Freedom is similar to…, because…” activity

Under this heading, children were asked to make metaphors about “freedom” In response to the statement “Freedom is similar to…, because…” they were asked to draw a picture of what freedom means to them and what it looks like. Then, the children were interviewed individually, and their thoughts about the picture they drew were collected. In this way, both in the philosophical sense and in the philosophical approach to children, an attempt was made to ensure that the children expressed their opinions about what freedom means and what it means to them and also gave reasons (G) about this topic. After the second and third activities, the children were again confronted with this exercise.

In the first application of the metaphor study on freedom, 15 out of 19 children (15/19) participated; in the second application, 12 out of 19 children (12/19) participated3. The codes and themes that emerged about the children's metaphors during the pre-application and post-application on the theme of freedom are listed below.

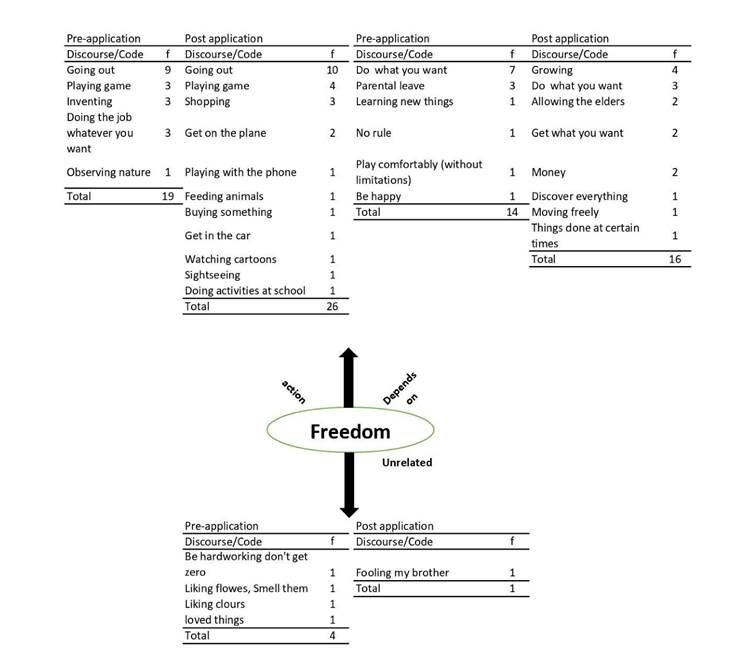

figure 1: Emerging discourses/codes on the analysis of children's metaphors about freedom perception.

The children's discourses are categorized under the themes of action, the situation on which freedom depends, and unconnectedness in the metaphor about freedom, as shown in Figure 1. Accordingly, the children not only compared freedom to “actions” but also reflected in their analogies the situation/base on which freedom “depends” They also made analogies that had nothing to do with freedom. However, these irrelevant metaphors were reduced to a minimum (1/12) after the activities on freedom in the second metaphor.

The children's first discourse on the true meaning of freedom in the approach to philosophy and philosophy for children consists of analogies for “actions” It was noted that these metaphors (see Figure 1) come before activity 19 and after activity 26. “Going Out (9/10)” focused on freedom-related actions before and after the activity. This theme was followed by a discourse on “playing (3/4)” They compared freedom at home and outside, emphasizing that it is freer to be outside than at home. They expressed this situation as having the opportunity to play outside with their friends. So when children play together outside, they feel the freest. For children, outside is a place with no restrictions, like at home, where they can play and do what they want. The basis for their desire to go outside is their desire to play. Play is a pleasurable, voluntary act in which children participate at the action level, reveal their thoughts and feelings, and have the opportunity to explore and observe with their sense of curiosity (MEB, 2013, p. 47). After the discourses on going out and playing, it was found that the expressions invent (3) and do what you want to do (3) were frequently used in the pre-registration; the expressions shop (3) and get on a plane (2) were frequently used in the post-registration.

The second of the children's freedom metaphors refers to the situation in which freedom is dependent. These analogies (see Figure 1) were found in 14 cases before the activity and in 16 cases after. “To do what you want (7)” in the pre-application and “to grow (4)” in the final application were at the top of the discourse defining the situation on which children's freedom depends. These discourses were followed by “parental leave (3)” in the pre-application and “to do what you want (3)” in the final application. In this context, it can be concluded that children's perception of freedom is shaped along the axis of “do what you want, parental leave, and growth.” According to Droit (2017), obedience and freedom are two completely different ways of being for children. To be obedient means to obey the will of another imposed from without (e.g., by parents, teachers, or adults) rather than one's own will. Being free also means eating as much chocolate as possible, not bathing, eating, and sleeping late. An essential criterion for their independence may be their parents' permission to do what they want or the fact that they will make their own decisions when they grow up. For example, one child (EEZ) claims that flying means freedom and that he or she will not be able to do this until adulthood. In the preliminary application, one child stated that there are “no rules” In the final application. However, another stated “money” as a means to freedom. It can be said that the children's expressions of the conditions on which freedom depends, such as “growth, parental permission, lack of rules, and money”, draw the boundaries of freedom in a philosophical sense.

Examining the children's non-meaning discourse, we find that the expressions in the pre-announcement are 4 (e.g., being industrious, liking flowers). These expressions are also 1 in the final application (fool my brother). At the same time, the number of expressions that did not make sense decreased.

In general, children discuss the meaning of freedom and the limits of freedom (permission, prohibition, growth, money, and rules) within the framework of children's philosophy itself. It has also been shown that what they can accomplish within the limits of their free will varies by age. In addition, it has been shown that children have different perspectives on each subject (school) regarding independence. For example, while one child (EBA) stated that he feels free when not in school, another child (KHB) described the school as a place where he can do different things. When examining children's metaphors and images and talking about freedom, it is clear that they value freedom in terms of playing outside, restrictions and permissions, growing up, and doing what they want. This study found that the children used statements that had nothing to do with the concept's meaning and statements about the meaning. However, in the final application, it was found that these irrelevant statements decreased. Again, it was found that the number of meaningful statements about the concept of freedom increased quantitatively in favor of the post-activity before and after the activity. However, it was found that student discourse increased in favor of the last application (rule, money, being independent). It can be said that “… am I free?” and "Rapunzel story activity" performed after the first implementation influenced this determination. The “… am I free?” activity made the children question topics such as attending school, following rules, and choosing friends. The activity “Rapunzel story” discusses Rapunzel's curiosity about the outside world, her desire to leave the tower, what she can do in the outside world, and in what situation she is free. The children also evaluated freedom through this focus. For example, one of the children's expressions of freedom was “to be able to move freely” This expression bears the traces of the “Rapunzel story activity” shown to the children as part of the Philosophy for Children approach. Thus, the children's expressions of the concept of freedom were varied. In this way, children can express abstract concepts such as freedom and use metaphors and stories to ask about them. As for thinking ability, they express themselves based on causes and effects due to the nature of the activity; when describing the conditions on which freedom depends, they express themselves mainly based on evaluations. In addition, children were found to describe freedom (free/unfree), make comparisons, incorporate fictional components into their pictures (e.g., flying bicycles and flying ships), and express creative ideas (cutting machine).

the results of the activity “…am I free?”

One of the topics discussed in Philosophy for Children is the criteria by which individuals make their choices and to what extent they are free. Therefore, this activity sought to ensure that children decide when they are free and explain their reasons for doing so. Due to the nature of the activity, children were required to make decisions and justify them (G). In this event, 13 out of 19 students participated (13/19). When the same questions are repeated in class, children are known to repeat each other's answers. Therefore, the children were asked different questions in the activity. These are the questions:

- Are you allowed to eat as much chocolate as you want?

- Are you allowed to go to bed when you want?

- Are you free not to go to school?

- Are you allowed to go out and play when you want?

- Are you allowed to break the rules?

- Are you free to choose your friends?

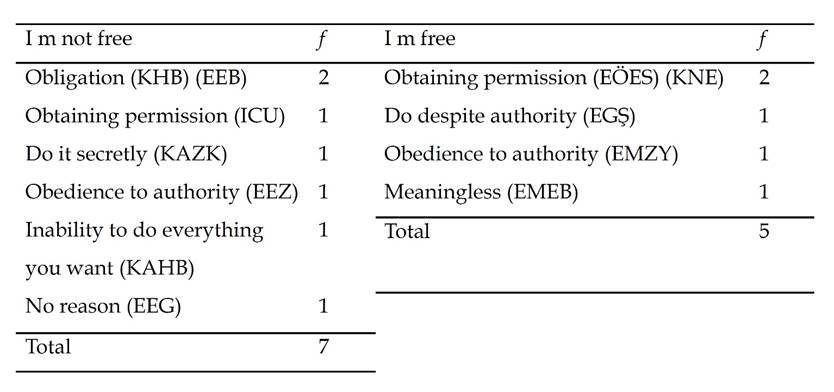

The children were then instructed to “stand on the yellow cardboard on the floor if they think they are free, and stand on the red cardboard if they think that they are not free”. They should explain why they are free or not. The children's answers to the questions about freedom were categorized under the titles "I am free" and “I am not free” based on their decision status for each question, and the reasons for the answers they gave were examined individually. As a result of this investigation, several codes were discovered. These are summarized in the following table.

As can be seen from Figure 2, within the theme “I am not free”, the children emphasized “obligation” (2/7) the most when evaluating the codes from the domains “decision making (DM) and justification (G)”. In the context of children's philosophy, they present their arguments (justifications) for conditions that limit their freedom. For example, EBB answered, “Are you allowed to break the rules?” as follows: “We have to pay attention to our teachers. We learn new things from them”. He responded with rhetoric, explaining that he was not free because he was “obligated” in the context of a cause-and-effect relationship. KHB responded to the question, “Are you free not to go to school?” with this code, “We have to go. Because if we do not go to school, we will not learn anything. We can not read the texts if we do not go to school. However, I want to go to school. Because there are so many good things in school”. He emphasized that going to school “is an obligation (duty) and not a freedom”. KHB used their discourse to evaluate within the framework of the criteria: “We can not learn anything if we do not go to school. If we do not attend school, we can not read the scriptures”. It also establishes a cause-effect relationship with the saying “…because there are many beautiful things in school” “Obedience to authority” is another code proposed under the theme “I am not free”, and “limiting the freedom of children within the framework of philosophy for children. In this context, “Are you free not to go to school?” EEZ to the question, “No. I tell my mother that I do not go to school, and she says you have to go to school”.

Also, the phrases “Do not obey authority” and “Can you go to bed when you want?” were used in the context of the theme “I am free” EMZ says: “Yes, I am free. I do not sleep late, but I sleep early. Yes, they tell me to go to bed, but I listen to what they say”. However, it is clear from his statement that he is indecisive and ambivalent about freedom. Although he says he is free to go to bed when he wants, he listens to his parents. In the context of “I am not free”, KAHB responds to the question, “Can you go out and play whenever you want?” as follows: “I am not free. Because we can not do everything we want outside”. She rated freedom in the context of not being able to do everything she wants outside, rather than the lesson highlighted in the question. The “parental leave” may have influenced her on this issue. Another question asked, “Are you free to not follow the rules?”. EEG answered this question by saying, “I have to”. He answered that he was not free to do so but did not explain the reason (grounding).

On the topic of "I am free," the children mainly mentioned the topic of "asking permission” (2/5); they emphasized the limits of freedom in philosophy for children. KNE responded to the question “Are you free to go out and play whenever you want?” with this statement, explaining that the criterion of his freedom depends on “permission”: “I am free, sometimes I can go out alone. My grandmother sometimes lets me go out alone, but I can not do that in cold weather” When asked, “Are you free not to go to school?” EOES answered, “I am free. My mother told me that sometimes you could stay home for three days” He emphasizes that he is available at certain times on this issue, again with his mother's permission.

Similarly, asking permission was included in the theme “I am not free”, EUÇ evaluated the question, “Are you allowed to eat as much chocolate as you want?” “I will eat if my father takes it; I will not eat if my father does not buy it.” “We may consume it discreetly from our parents”, KAZK responds to the same question. She responds with rhetoric, claiming she can do what she wants secretly because she is not free. In this sense, the freedoms of the EU and KAZK could be said to be “limited to her parents” In particular, KAZK's notion of “if there is no authority, you can behave in forbidden ways” that she uses to act freely relates to Kohlberg's “pre-conventional level” of moral levels that he defines. EGŞ answers the question, “Can you go to bed when you want?” thus, “Yes [he goes to the box to show that he is free], I go to bed at nine-thirty and sleep at eleven. My mother tells me to go to bed, but I go to bed at 11, and she talks to me”. He said he sleeps when he wants, even if his mother dictates it. So we can say that EGŞ shows this behavior “despite authority” The fact that his parents consider him sleeping means freedom for him. This view shows that he is at “Kohlberg's pre-conventional level” regarding moral development. Again, “Are you free to choose your boyfriend?” EMEB answers that I am free. However, “I am not big, I can not make him do what I want [by going to the cardboard box he is free to choose], I am free. Because we are friends with him, we have fun”. His statement shows he is confused about this issue and presents “meaningless” reasons that do not answer the question.

Looking at children's expressions about freedom in general, we find these expressions are grouped under the themes “I am not free” and “I am free” depending on their decision status. In the context of philosophy for children, more commitments under the theme I am not free; under the theme of my freedom, they emphasized the permission to take; It was found that the discourses of permission to take and authority to obey are included in both themes. In this context, it was found that the children determine the limits of freedom while expressing the situation of being free. The children see their parents as authority when they act. It was found that sometimes they ask for their permission, do it secretly, or do it despite authority. Two children (EMZY and EMEB) have problems making decisions about freedom and justifying them. However, regarding the children's philosophy, it was found that the children generally made comparisons during the discussion process and presented them with their justifications. Regarding thinking skills, due to the nature of the activity, expressions based on cause and effect are common, but they also use expressions based on evaluation and make comparisons.

findings on the “rapunzel story activity”

The third activity on freedom was conducted under the categories of justification (grounding) (G), question generation (SU), questioning (S), and idea generation (FI). An attempt was made to ensure that the children asked their questions, shared their thoughts, emphasized whether they agreed with their friend's opinion, and presented their justification (grounding) within the framework of the “philosophy for children” approach. For this purpose, a part of the “Rapunzel” story was watched with the children, in which freedom is emphasized (see URL 1). First, they were asked to watch the video and think about the situations that interested them in the story. After the video, they were asked to formulate questions about freedom. These questions were then discussed with the children. As the children formulated their questions and searched for answers in the story, shared their views, presented their justifications, and discussed their opinions, the categories of “justification (G), question generation (SU), questioning (S), and idea generation (IG)” were applied. Thirteen (13/19) children participated in the event.

In the context of the story activity, “freedom” and “those thought to be related to freedom” were selected from the questions produced by the children and discussed in class. These questions are as follows;

- Why did they lock Rapunzel in the tower?

- Is Rapunzel free in this tower?

- Why did Rapunzel never escape from the tower?

As mentioned earlier, in philosophy, children must declare whether they agree with their friend's opinion to develop ideas and support them with reasoning. Therefore, in the discussion, the child who asked the question first explained his question with a rationale. If he or she did not have an answer, another child was given the right to speak. Then the others gave their rationale by choosing one of the options, “I agree” or “I disagree”, against their friend's answer. The children's responses were then evaluated individually. Below are the children's responses to the questions and their analysis.

why did they imprison rapunzel in the tower? analysis of the question

To the question, “Why did they lock Rapunzel in the tower?” KAHB answered, “Because she might have done something to the environment. For example, she might have left a messy place”. This suggests that contrary to the story's content, KAHB relates her difficulties to the “second form of punishment” because she was deprived of her freedom. Other children (KEHB, KEB, EMZY) disagreed with this response, which had nothing to do with the story's content but could be applied to their everyday lives. They responded, “I disagree”, using the philosophy of children's approach. Therefore, the EEB with the conjunction “because” means “I disagree”. “Because there is no such thing, Rapunzel cleaned everywhere.” He contradicted KAHB's sentences by supporting his statement with evidence. KHB said, “Because there is no such thing. Maybe it was because her parents bought lettuce during Rapunzel's birth”. She explained, claiming that Rapunzel was imprisoned because of a punishment imposed on her parents. “Because there is no such thing”, EMZY said. “Because the witch took it and put it there.” He explained that his speech differed from that of KHB and KAHB and that Rapunzel's cause (house arrest) was due to the “judgment of the witch”.

is rapunzel free in that tower? analysis of the question

To the question, “Is Rapunzel free in this tower?” answered EMZY: “No, because there is nothing in the house. There is cleaning, sweeping, and sewing. For example, when we go out, we can do something nice. We can play, buy daisies for our mother, and do all kinds of things”. In his talk, he compared home to the outdoors, using examples to explain that the outdoors creates a space of freedom where you can play and do what you want. He noted that Rapunzel was not free in this direction because she could not do these things in the tower. In addition, EMZY said, “This is the first time Rapunzel has been outside, and she loves it there. That is why she never goes back inside the tower. The funniest thing is outside. Because there is a park outside, we play games; we play sports, we travel”, he explained that Rapunzel would not return to the tower after seeing this because of her understanding of freedom. When comparing EMZY's and other children's views on children's philosophy, EUÇ and KHB “agree”; however, EMEB and EGŞ responded, “I disagree”. EUÇ stated that he joined EMZY and “outside is free”, meaning that Rapunzel was not free in the tower for no apparent reason. KHB said, “Outside, we are free, but not at home. The whole house is already closed. At home, we play with toys, and we are bored. When we play with a toy, we draw and are bored. We have no friends; our mother's friends always come. We can not play at all”. She tried to explain that Rapunzel is not free by giving an example from her own daily life, stating: “Like EMZY, he contrasted with home and outside. In his opinion, he supports EMZY's idea that the outside gives people freedom”. EMEB turned against EMZY with this statement: “Freedom. For he paints, sings and can do many things even if there is no tree” and explained that Rapunzel could do anything she wants in the tower even if she does not go outside. EGŞ also said, “She is not free to paint and sweep everything. She can not slide off the slide, and she can not swing from the swing”, which means that she is not free to do everything. He compared what Rapunzel could do at home and what she could not do outside; therefore, he was against EMEB's free expression at home.

why did rapunzel never escape from the tower? analysis of the question

EUÇ answered the question, “Why did Rapunzel never escape from the tower?” by saying, “If the witch does not allow it, she can not escape”. He emphasized that Rapunzel could not escape from the tower mainly because of the “witch”. EUÇ's discourse shows that he evaluates based on criteria. In response to EUÇ's opinion, EMEB, KNE, KG, and KHB “agree” with the philosophy for children, but EEG says, “I disagree”. “Because the witch could see them”, EMEB claims. His speech demonstrates why Rapunzel, like the EU, could not escape from the tower as a “witch”. Also, “Maybe she has not gone out yet. She was afraid of heights”, he predicted. “Girls are sometimes afraid of heights”, EMEB said. He generalized his statement. “Maybe his mother is in the tower, too.” He gave Rapunzel's reason (grounding) for not escaping from the tower as “mother”. “Maybe she has not found that method yet”, EGŞ said. Unlike the others, he drew attention to the “method problem” with his discourse and spoke of a possibility like KNE. EEG also opposed EDU, saying, “She can run away when the witch collects something, goes somewhere. She can go out with her hair”, and suggested a solution to the problem. Therefore, he showed a capacity for “problem-solving ability” KHB disagreed with EEG's opinion and said, “Why? Because he was still a baby. When she was grown up, the witch cut off her hair. What will happen next?”. She emphasized that she could not escape because she was still very young and did not have the opportunity to do so because the witch later cut off her hair, so she explained that running away with her hair, as the EEG said, could not be a solution.

In general, the children's follow-up questions about the Rapunzel story showed that they were more concerned with the causes limiting freedom and the goals of the plot. Evaluating the questions by level showed that the children asked questions based on the reason and the why (convergent thinking). Regarding the approach to philosophy for children, it was found that they made statements about the nature and limits of freedom and listened to each other. During the discussion of the questions, they indicated whether they agreed or disagreed with their friends' ideas. The children were observed explaining their viewpoints using examples from their lives (e.g., playing games at home and outdoors). It was also noted that children who had seen or heard the story included related elements in their responses (e.g., Rapunzel's mother giving birth to her and her father getting the lettuce). In terms of thinking skills, it was found that they used expressions based on cause and effect, evaluation, generalization, comparison, examples, probabilistic thinking, evidence, and problem-solving.

discussion

According to the results, the children discussed the meaning of freedom and the limits of freedom for themselves in the philosophical framework for children. In this sense, it was found that children define freedom mainly as “playing outdoors”; they use terms for freedom outside of play such as “forbidden, permission, growth, doing what they want, being able to behave freely”. According to Ölçer and Yılmaz (2019), children's views on the concept of freedom were divided into three categories: Behavioral autonomy, social-emotional autonomy, and cognitive autonomy, and their approach to the concept of freedom is primarily behavioral autonomy, which is defined as individuals' control over their behavior and taking responsibility for their behavior (51.64%), and they see play as a place of freedom. It can be argued that children feel most free when playing outdoors and in the community, especially when they play together. Unlike at home, children have no constraints outside, and they can play and do what they want. Bağatır (2008) also states that the moment when the child feels most free is playtime, so he tends to play without coercion or guidance. In the play, the child lives the world he wants and sets the rules in that world himself. The concepts of freedom, seriousness, excitement, order, sharing, and pleasure are expressed in the play. Doğan-Ömür (2012) claims that 6-year-old children's definitions of freedom include “doing what they want”, “behaving the way they want”, and “getting out of prison/something” According to Çelikkaya and Seyhan (2017), who conducted metaphor research, to determine secondary students' perceptions of universal values, children were most likely to associate freedom with a bird and explained this as being able to go where they wanted when they were not allowed to. Bayrakdar (2022) examined the perception of freedom of imprisoned children through metaphors. As a result, metaphors are connected with present situations; for example, just as preschool children define freedom as playing games, imprisoned children express freedom as being unburdened by using the metaphor of a bird. Because the bird can fly anywhere it wishes without encountering any barriers. These children's perspectives on freedom are consistent with the study's findings.

The children also emphasized the limits of freedom in the activities and the issues that arose from the activity, expressing these limits as “permission, prohibition, growth, money, rules”. In Karasu's study (2018) with fourth-grade students, the children indicated that the factors affecting freedom were “growing up” and “others”. Toy, Uzunoez, Aktepe, and Meydan (2020) studied metaphors with prospective teachers about the value of freedom. They found that teachers likened independence to a cage with restrictions, stating that they believe laws and rules restrict freedom and that they are dependent on someone else. Çelikkaya and Seyhan (2017) also tried to determine the perceptions of social studies teachers and teacher candidates towards universal values. Accordingly, while teachers and pre-service teachers chose the bird metaphor for freedom, they described the absence of barriers as freedom. Freedom is immensely provided that it does not disturb anyone, changing according to the situation; it is not clear where it starts and ends, and knowing its limits is another qualification of freedom by teachers and teacher candidates. In studies conducted in this sense, freedom is discussed in the context of obstacles, rules, and borders that coincides with the expression.

When children made statements about the meaning of a concept, they also used unrelated expressions; however, in current practice, these irrelevant expressions decreased; it was determined that right-meaning discourses about the concept of freedom increased after the activity. However, it saw that with the last application, student discourses expanded with phrases such as rules, money, and independence. Aydemir and Kalın (2018) studied the changes in their judgments of the values of independence, freedom, self-confidence, and modernity in 8th-grade students before and after values education. Children especially perceived freedom as travel, after school, vacation, and a physical education lesson due to the research in the pre-application. They described it as freedom, rights, a statute of liberty, law, democracy, and justice in the last application. Karasu (2018) found that students' perception of freedom changed after the activities; the answers about freedom, which were initially given at the level of understanding, started to be given at the level of evaluation. The success of the activities carried out with children in the research and the value education provided might explain this variation in children's discourses or perspectives.

Children perceive their parents as the authority when performing an activity. Considering the child's age level, this situation can be explained by the fact that their behavior largely depends on their parent's approval (Oruç, 2010). Sometimes, they get permission from them, doing it secretly or despite authority. According to Kohlberg's stage of moral development, there are three stages (pre-conventional, conventional, and post-conventional morality) and six phases, with two steps at each level. At the first level (pre-conventional), the emphasis is on the benefits of one's actions, and rules are regarded as acceptable due to authority and its sanctions; Interpersonal interactions and social expectations are considered at the second level (traditional); at the last level (post-conventional), people utilize their moral standards (Çiftçi, 2003). According to this, the children's belief that “if there is no authority, prohibited behavior can be done” is associated with the “pre-conventional level”, the first of Kohlberg's moral development stages. Because, according to Kohlberg (1958), at this stage, the child believes that powerful authorities have created a system of definite rules. He behaves according to the outcome of his behavior and claims that the action is wrong due to punishment (Crain, 1985).

In the story activity, it was observed that one child (EMEB) associated Rapunzel's inability to escape from the tower with the fact that she was a girl and made a generalization. This generalization can be cited as an example of the impact of gender perception on the conception of freedom. In their study, Esen, Soylu, Siyez, and Demirgürrz (2017) found that male students have a traditional view of gender perception. Accordingly, the understanding that housework is women's job, that men are strong and should protect women, and that men are the authority at home is evident. Kırbaşoğlu-Kılıç and Eyüp (2011) found that a traditional understanding influences the gender roles presented to women and men in Turkish 6th-grade textbooks. In the textbooks, it was found that males were more represented in occupational roles than females, that males were portrayed in different and diverse occupational roles compared to females, and that females were more expressed in family roles; in roles related to housework, women were presented as being inside the house, while men were presented as being outside the house and the breadwinner of the family.

Regarding the philosophical approach for children, children made statements on the nature and limits of freedom, listened to one another, and presented with reasons (grounding) whether they agreed or disagreed with their friends' ideas throughout the discussion of the questions. In terms of thinking skills, it was observed that they used expressions based on cause-effect, definition, evaluation, generalization, comparison, giving examples, probabilistic thinking, showing evidence, creativity, and problem-solving. Because through philosophy for children, children discuss with each other and develop their reasoning skills by thinking together in this discussion environment; they become more independent and active learners. They use their knowledge and experience to discuss the questions and continue the conversation toward their interests. Children develop critical thinking skills by reasoning, evaluating objections, and counterexamples; creative thinking skills by presenting and discussing their ideas; focus and concentration skills; the ability to listen attentively and not interrupt others; communication skills by putting thoughts into words and communicating them clearly to others; and social skills by being respectful and tolerant of others' ideas (Gaut & Gaut, 2012). Philosophy for children, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2007), improves children's independent thinking capacity, critical thinking skills, reasoning, and argumentation skills, and thus self-esteem (listening to others' opinions, voicing their opinion in front of the group), and language skills. Garcia-Moriyon, Rebollo, and Colom (2005) stated that the philosophical approach for children positively affects the development of their reasoning skills. Daniel, Gagnon, and Pettier (2012) examined "philosophy for children and the development process of dialogical critical thinking in preschool children's groups." They discovered that philosophy for children improves children's ability to understand peer views and react dialogically, and they begin to think relatively rather than egocentric thinking. Lam (2012) found that students studying philosophy for children showed significant improvement in the reasoning test, and this approach played an essential role in developing students' critical thinking. Säre, Luik, and Tulviste (2016) stated that students who get a philosophy education for children are better at comparing, analogy, justification, giving reasons, and creating intellectual connections regarding the cause, and their language skills and academic achievements improve.

Given all of these factors, it is recommended that essential values such as equality, freedom, justice, tolerance, solidarity, etc., which are included in both social studies and preschool education programs, should be tried to be taught to children through activities by using the philosophy approach for children from the preschool level; in this sense, arrangements should be made in the preschool and social studies programs; especially in the preschool period, considering the perception that "children do not think abstractly," applications should be made to encourage children to discuss with materials such as stories, cartoons, photographs; the suitability of these materials for discussion should be checked and helpful resources should be provided to the teacher.