Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Estudos em Avaliação Educacional

versión impresa ISSN 0103-6831versión On-line ISSN 1984-932X

Est. Aval. Educ. vol.35 São Paulo 2024 Epub 21-Jun-2024

https://doi.org/10.18222/eae.v35.10687

ARTICLES

MAPPING SCIENTIFIC PRODUCTION ON SCHOOL CLIMATE: AN INTEGRATIVE REVIEW

IUniversidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM), Santa Maria-RS, Brazil;

IIUniversidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM), Santa Maria-RS, Brazil;

IIIUniversidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM), Santa Maria-RS, Brazil;

IVUniversidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM), Santa Maria-RS, Brazil;

VUniversidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM), Santa Maria-RS, Brazil;

VIUniversidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM), Santa Maria-RS, Brazil;

VIIViamundi Idiomas e Traduções, Belo Horizonte-MG, Brazil;

The aim of this study was to map national and international scientific production on school climate. To this end, an integrative literature review was carried out using the time frame from 2019 to 2023. Sixteen articles were selected that addressed different conceptions of school climate and were submitted to conceptual and methodological analysis. The analysis indicated a diversity of concepts and instruments used to assess school climate, and a predominance of quantitative international studies. The need for studies in the national context is essential, given the impact that school climate exerts on the well-being, quality of life and educational process of students.

KEYWORDS ADOLESCENCE; SCHOOL CLIMATE; EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY.

Este estudo buscou mapear as produções científicas nacionais e internacionais referentes ao clima escolar. Para isso foi realizada uma revisão integrativa da literatura, adotando- -se o recorte temporal de 2019 a 2023. Foram selecionados 16 artigos que abordaram diferentes concepções sobre clima escolar, os quais foram submetidos a análise conceitual e metodológica. A análise indicou uma diversidade de conceitos e instrumentos utilizados para a avaliação do clima escolar e a predominância de estudos internacionais quantitativos. A necessidade de estudos no contexto nacional é essencial diante dos impactos que o clima escolar exerce no bem-estar, na qualidade de vida e no processo educacional dos estudantes.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE ADOLESCÊNCIA; CLIMA ESCOLAR; PSICOLOGIA DA EDUCAÇÃO.

El objetivo del presente estudio fue el de mapear las producciones científicas nacionales e internacionales sobre el clima escolar. Para ello, se realizó una revisión integradora de la literatura, adoptando el marco temporal de 2019 a 2023. Se seleccionaron 16 artículos que abordaron diferentes concepciones de clima escolar, y que fueron sometidos al análisis conceptual y metodológico. Dicho análisis indicó una diversidad de conceptos e instrumentos utilizados para evaluar el clima escolar y el predominio de estudios internacionales cuantitativos. La necesidad de estudios en el marco nacional es fundamental frente a los impactos del clima escolar en el bienestar, calidad de vida y el proceso educativo de los alumnos.

PALABRAS CLAVE ADOLESCENCIA; CLIMA ESCOLAR; PSICOLOGÍA DE LA EDUCACIÓN.

INTRODUCTION

The school institution is characterized as an essential context of human development, where the learning and socialization processes of children and adolescents are made possible (Dessen & Polonia, 2007). In this educational environment, the school climate, in turn, is defined as the set of perceptions and expectations resulting from the experiences of the different actors that make up the educational context (Santos & Adam, 2022). These perceptions about the school climate are linked to interrelated aspects such as values, norms, relationships, structure, organization - from physical to administrative -, among others. In this sense, each school has its own climate (positive or negative), or psychosocial atmosphere, which, mutually related to the school dynamics of each institution, influences the quality of life and the teaching-learning process (Vinha et al., 2017).

A positive school climate is associated with support, security, belonging and quality present in the interpersonal relationships and in the teaching-learning process (Vinha et al., 2018). In addition, a positive climate is linked to satisfactory academic performance, qualifying as a protective factor in the socioeconomic and educational context (Vinha et al., 2018). On the other hand, the negative school climate is related to the emergence of behavioral problems, increased stress and conflicts, unsatisfactory school performance (Vinha et al., 2017) and involvement in situations of peer intimidation (Wrege, 2017), in addition to being associated with the presence of violence, such as bullying, which can be characterized as a factor of vulnerability to the quality of life in the school institution (Melim & Pereira, 2013).

Research into school climate becomes essential in view of its impacts on the well-being, quality of life and educational process of students. The school climate, specifically, has implications for and is affected by the relationships established in the school. Thus, in addition to impacting the well-being of school actors, the climate can prevent or produce violence. Therefore, the study, evaluation and intervention in the school climate become relevant since, in Brazil, there have been more attacks and threats of violence in this context (BBC News Brasil, 2023; Félix & Franzão, 2023).

In this way, research plays an essential role in surveying the scientific production related to school climate, seeking to understand the construct so that, by understanding the elements, interventions and public policies can be built to prevent negative school climate and promote positive school climate, especially in a scenario where attacks and threats are present. These attacks can occur in contexts previously affected by violence and be carried out by individuals who often have experienced feelings of loneliness, stress and have been victims of bullying (Welter et al., 2022). This is where the relationship with the school climate becomes relevant. A school environment with a positive climate has the potential to prevent the emergence of violent situations (Alcantara et al., 2019). Therefore, the present study aimed to map national and international scientific productions related to the school climate.

METHOD

Characterization of the study

This is an integrative literature review, which consists of synthesizing available research on certain topics, based on scientific knowledge (Souza et al., 2010). The integrative review followed eight steps, namely: delimitation of the research question, choice of data sources, choice of keywords, search and storage of results, selection of articles by title and abstract, selection of article data, evaluation of selected articles, and synthesis and interpretation of the data (Costa et al., 2022).

Research question and search tools

The guiding question was developed using the PICOD strategy, which represents the initials of the essential components of the question: patient/problem, intervention, comparison and result. Based on these elements, we can make the following analysis: P: main concepts, participants, variables investigated; I: there is no specific intervention mentioned in the question; C: there is no specific comparison mentioned in the question; O: scientific productions on the school climate construct; D: study design (Araújo, 2020). Thus, the study question was: what are the main concepts, methods (e.g., design, participants, instruments) and variables investigated in the scientific productions on the “school climate” construct?

The search for the studies took place between May and June 2023 in the following databases: Web of Science, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), American Psychological Association (PsycINFO), and SciVerse (Scopus). The following word combinations and the respective Boolean operators were used: “clima escolar” OR “ambiente escolar”; and, their respective names in English, “school climate” OR “school environment”.

The inclusion criteria were: time frame within the last five years (2019-2023); articles in Portuguese, English and/or Spanish; articles that had adolescents as participants (10 to 19 years old, following the criteria of the World Health Organization - WHO), teachers and/or managers; articles that presented the words “school climate” and/or “school environment” in the title and abstract; empirical articles using different methods (qualitative, quantitative or mixed); and, articles that were peer-reviewed. The exclusion criteria were: duplicate works; reviews; articles with the abstract unavailable; and, articles not available in full. Studies that addressed only the validation of instruments were also excluded.

Data extraction, analysis and interpretation of results

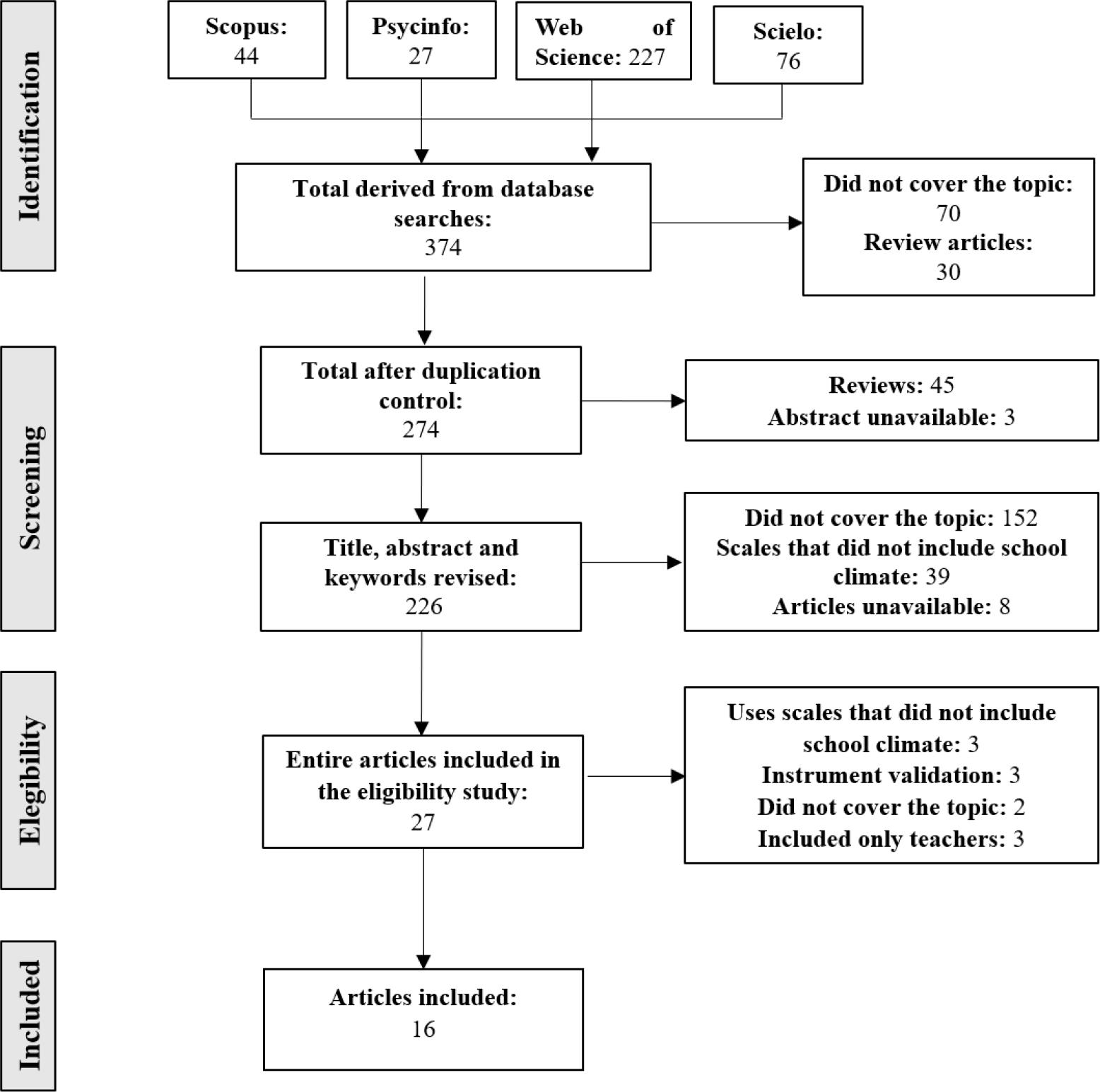

A total of 374 studies were identified in the databases: 27 in PsycINFO, 76 in SciELO, 227 in Web of Science, and 44 in Scopus. To select the studies, four independent researchers first read the titles and abstracts. The free software Rayyan was used, which is a computer service designed to help researchers with their reviews (Ouzzani et al., 2016). Subsequently, the abstracts were analyzed and each article was screened and read in full. Also at this stage, the articles were fully analyzed, taking into account aspects such as: study objective, main concepts, main results, instruments used, method, country of origin and language (Portuguese, English or Spanish), authors and year.

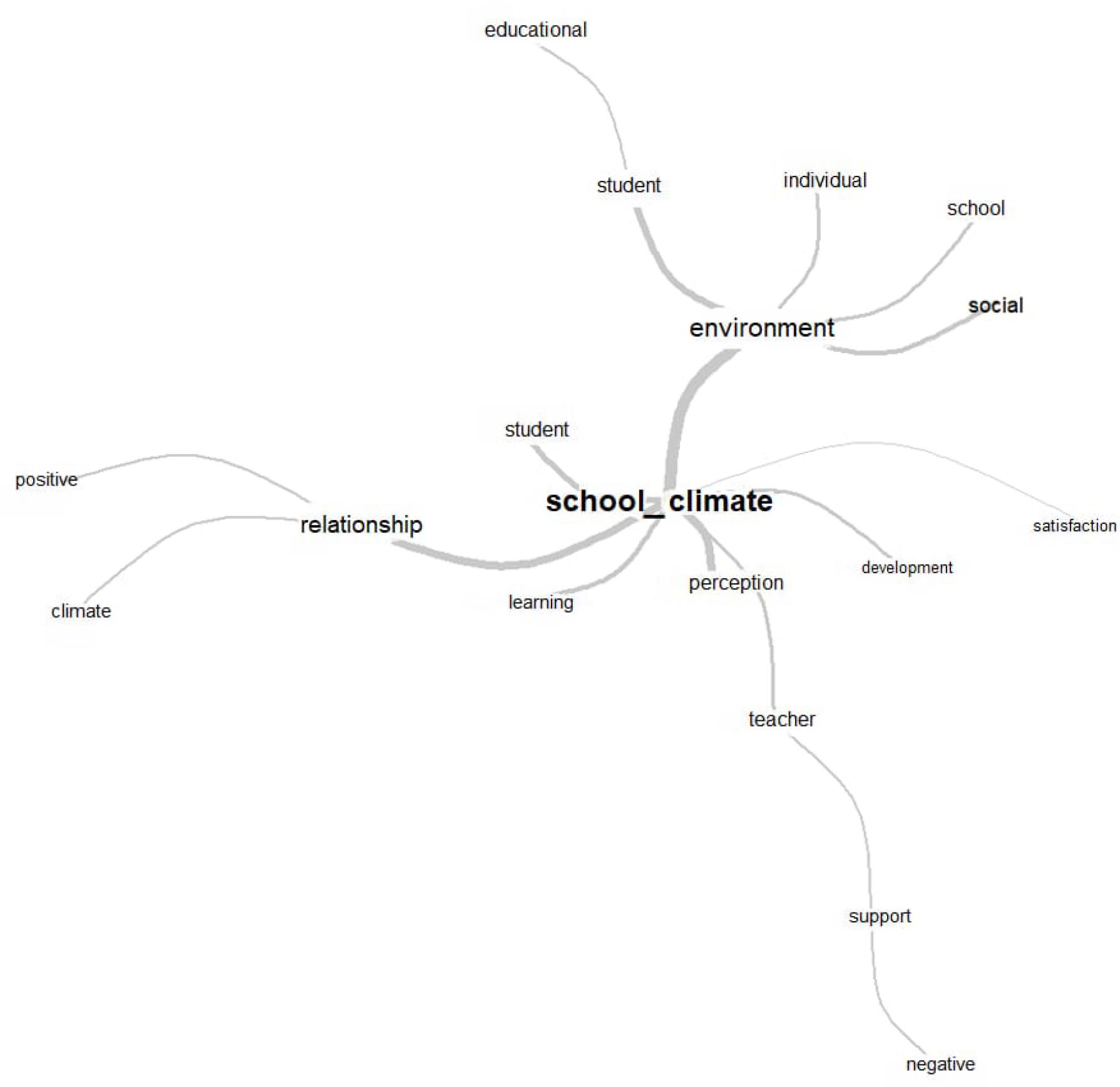

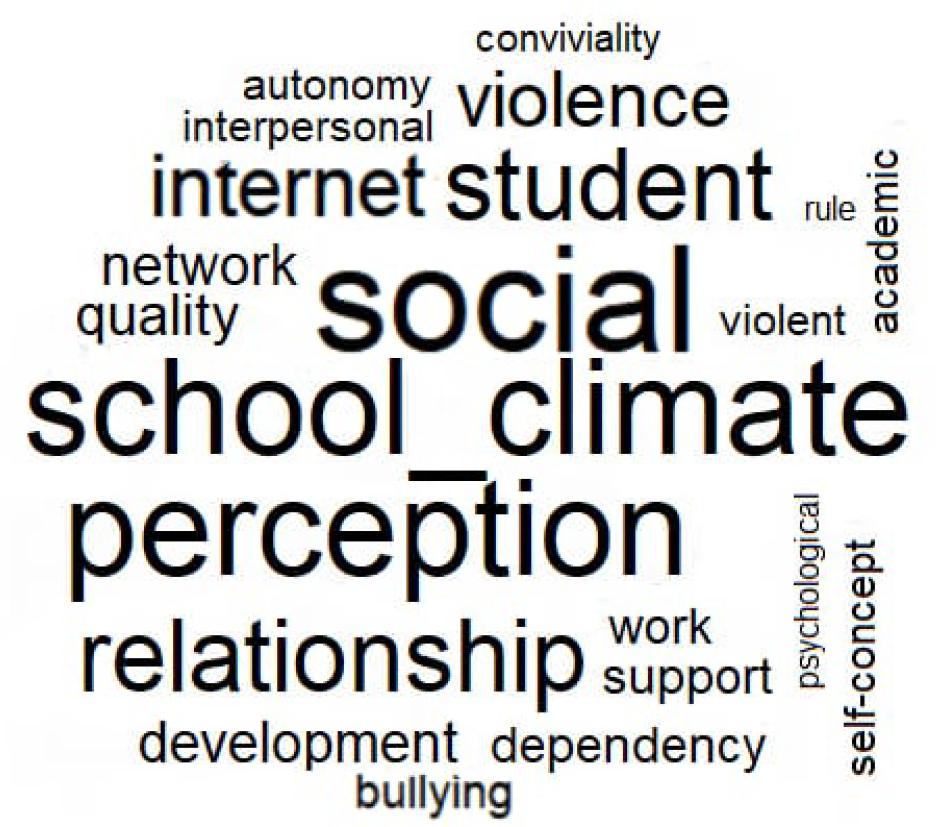

In addition, to answer the research question, the main results and concepts of the articles were added to a corpus for analysis, with the support of the Iramuteq software. This program enables different types of textual analysis, such as descending hierarchical analysis, word cloud analysis, descending hierarchical classification, simple correspondence analysis, in addition to allowing in-depth exploration of textual data (Camargo & Justo, 2013). Figure 1 illustrates the process of selecting and excluding articles.

The 16 articles selected for the final review were read in their entirety, and the researchers analyzed their content in order to sort, classify and categorize the results. A table was used to identify data such as authors, year, country, type of instruments, main results, among others. Based on the content of the studies, and aligning the results and objectives, the following categories were created a priori: concepts of the studies about school environment and/or climate; description of the participants; study design, analysis of the results and language; description of the instruments; and, word clouds that include the main results of the articles.

We opted for the word cloud for the main results, and the similarity analysis of the different concepts of school climate (Souza et al., 2018). The former shows the frequency of repeated words in the text, while the latter allows the researcher to understand co-occurrences and the connection among words, helping to identify the structure of the text (Camargo & Justo, 2013).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results of the 16 articles analyzed in full are presented along the five axes, previously defined. For the purposes of the present study, the articles were identified with the letter “A” followed by a sequential number: A1, A2, A3, A4, (...) A16, as shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Specification of articles used in the final sample

| TITLE | AUTHOR/YEAR |

|---|---|

| A1 - Clima escolar como fator protetivo ao desempenho em condições socioeconômicas desfavoráveis | Melo and Morais (2019) |

| A2 - La valoración de estudiantes acerca del clima escolar, convivencia y violencia en escuelas secundarias del noroeste de México | Calderón-González and Vera-Noriega (2022) |

| A3 - Clima escolar y factores asociados: Modelo predictivo de ecuaciones estructurales | Cuadra-Martínez et al. (2022) |

| A4 - Sensibilidad intercultural, clima escolar y contacto intergrupal en adolescentes de escuelas municipales de la Región Metropolitana de Santiago de Chile | Lahoz i Ubach and Cuccia (2021) |

| A5 - Clima escolar, autoconcepto académico y calidad de vida en alumnos/as de aulas culturalmente diversas | Lahoz i Ubach (2021) |

| A6 - Tecnologias da informação e comunicação em adolescentes, práticas parentais e percepção de clima escolar: Uma abordagem multinível | Wendt et al. (2020) |

| A7 - Estudio de un modelo predictivo del clima escolar sobre el desarrollo del carácter y las conductas de bullying | Montero Carretero and Cervelló Gimeno (2019) |

| A8 - Estilo interpessoal docente. Un análisis de perfil según las diferenças en motivación necesidad psicológicas básicas, clima escolar y satisfacción con la enseñanza | Sánchez and Jiménez-Parra (2022) |

| A9 - La dependencia a las redes sociales virtuales y el clima escolar en la violencia de pareja en la adolescencia | Muñiz-Rivas et al. (2020) |

| A10 - Clima escolar e satisfação com a escola entre adolescentes de ensino médio | Coelho and Dell’Aglio (2019) |

| A11 - Clima escolar y libertad de expresión en adolescentes | Campos Ancalle (2020) |

| A12 - Exploración de las relaciones entre clima escolar, satisfacción con la vida y empatía en adolescentes costarricenses | Alvarado Calderón (2022) |

| A13 - Efecto del clima social escolar en la satisfacción con la vida en estudiantes de primaria y secundaria | Leria-Dulčić and Salgado-Roa (2019) |

| A14 - Contribución de la dimensión relacional del clima social escolar (CES) a la convivencia escolar para la no violencia (CENVI), desde la percepción de estudiantes de segundo ciclo y enseñanza media en escuelas y liceos municipalizados de Estación Central | Sánchez and Barría Ramirez (2021) |

| A15 - Habilidades sociales y clima social escolar en estudiantes de educación básica | Araoz and Uchasara (2020) |

| A16 - Violência entre pares, clima escolar e contextos de desenvolvimento: Suas implicações no bem-estar | Alcântara et al. (2019) |

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on research data.

Concepts from studies about school environment and/or climate

Figure 2 shows that there are four words that stand out in the discourse: “school climate”, “perception”, “relationship” and “environment”. From these keywords, others branch out, expanding the spectrum of analysis and providing a comprehensive understanding of the topic in question.

Regarding the term “school climate”, which connects all axes and is connected to the words “perception”, “relationship” and “environment”, it can be understood as the social environment experienced in the school context, whose reference is influenced by the perception of the relationship among members. In trying to understand this movement, the following excerpts1 taken from the analyzed studies show the following: “The school climate can be defined as the perception about experiences in the school environment, understood as a characteristic of educational establishments that is produced by the relationships among variables that influence behavior and school” (A7); “The School Climate is understood as a social space experienced in educational environments, whose quality will be conditioned by the relationships and perceptions among the members of education, the organization of the institution, the socioeconomic and political context in which one is inserted” (A8).

It is important to note that the concept of school climate is multifaceted. That is, it presents a wide range of variations. Although it is not a recent construct, there is no consensus among researchers from different countries who are investigating the subject (Moro, 2020). In the mapping carried out, it is possible to find several terms that are used to define school climate/environment (Moro et al., 2019) such as ethos, school atmosphere, school climate/environment (Matos & Carvalhosa, 2001), among others. However, what is common is that researchers try to define this concept by relating it to the feeling of individuals within the school institution, that is, how they perceive the institutional, organizational and coexistence space, the understanding of the relationships among the members of the school community, and the educational experiences (Moro et al., 2019).

Another branch of the similarity analysis concerns the words “school climate”, “teacher”, “support” and “negative”. This connection suggests the existence of an association among these terms in the school context. In this sense, it is understood that the school climate/environment can be positive or negative. The concept of negative school climate, as defined in study A8, is linked to the adverse perception of the school environment, characterized by lack of support, flawed interactions between students and teachers, and rejection among classmates. On the other hand, study A6 explores the concept of “positive school climate”, associating it with “learning”, which includes standards, goals and ideals that promote a “positive” environment, as well as good interpersonal relationships and “satisfaction”. This positive climate is also marked by high-quality social relationships, positive emotional environments, physical safety, and overall satisfaction.

It is important to highlight that the positive school climate exerts an important and significant influence on students’ quality of life. This may be linked to the feeling of well-being, self-confidence to carry out school tasks, motivation, learning and academic performance, attitude toward studies, identification and sense of school belonging, emotional and social development of students and teachers (Vinha et al., 2018). The negative school climate, in turn, can be considered a risk factor for the quality of school life, impacting confidence and violent behavior (Barreto Trujillo & Álvarez Bermúdez, 2017).

Another representative branch regarding the school climate, found in fragments of studies A5 and A10, connects the words “school climate”, “environment”, “development”, “student” and “environment”, “development”, “student”, “individual”, “educational”, “social” and “school”: “School climate is a concept that encompasses the properties of the school environment that affect student behavior and plays a crucial role in the development or not of behavioral problems” (A5); “School climate is understood as the quality of interactions at school that influences the cognitive, social and psychological development of the student. Other definitions include the importance of the individual feeling psychologically and physically safe in this educational environment” (A10).

That said, it can be observed that the school climate can affect student development, which may be related to violence, meaning that physical, verbal and/or psychological violence can affect the health, quality of life and the subjective, physical and social well-being of children and adolescents. These actions are intentional, repetitive over time and occur among peers, involving an unequal relationship of power and strength, without an apparent motivation (Currie et al., 2012).

In short, most authors report that school climate refers to the environment that addresses social, emotional, and psychological issues in a school. This scenario relates to the quality of interpersonal relationships, the emotional atmosphere and the support offered to students. This means that school climate directly influences students’ well-being, motivation, involvement in school activities and social-emotional development. The next topic describes the participants in the selected studies.

Description of participants

Regarding the participants of the analyzed studies, all are adolescents aged 10 to 19 (World Health Organization [WHO], 2013), according to the inclusion criteria established by the aforementioned review. Only one study (A1) included teachers and managers as participants, in addition to adolescents. The sample of adolescents in the 16 studies totaled 12,241, while that of teachers and managers (A1) was 599. The study with the lowest number of participants was A13, with 120 adolescents, and the one with the highest number of participants was A1 (2,731 adolescents). Regarding the type of school investigated, 8 studies (A1, A2, A4, A5, A10, A12, A14, A15) were carried out in municipal and/or state public schools; and 4 studies (A6, A7, A9, A16) investigated adolescents from public and private schools. Regarding students’ schooling, 6 studies (A1, A2, A4, A5, A16, A14) investigated adolescents in elementary school, with a greater predominance in the final years of elementary school (from the 7th to the 9th grade); 5 studies (A3, A8, A9, A10, A15) addressed only high school students; and 3 studies (A7, A11, A13) addressed both elementary school and high school students.

Regarding the criteria for selecting schools and participants, 12 schools (A1, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8, A10, A11, A12, A13, A14, A16) were selected for the convenience of the researchers, and there is no further description of these criteria. One school (A2) was chosen due to the high rate of violence (theft and vandalism) in the region where it is located. As for the selection of participants, in 12 studies (A1, A6, A7, A8, A9, A10, A11, A12, A13, A14, A15, A16) students were selected randomly with non-probability samples; and in 3 studies (A3, A4, A5) only volunteer students were chosen. Regarding the country of origin of the adolescents, 4 studies (A1, A6, A10, A16) were carried out in Brazil; one (A2) in Mexico; 4 (A3, A4, A13, A14) in Chile; one (A11) in Bolivia; one (A12) in Costa Rica; 3 (A7, A8, A9) in Spain; one (A15) in Peru; and one (A5) included adolescents from different countries - Chile, Venezuela, Peru and Haiti.

The description of the participants reveals a scarcity of studies that present the results of all school agents together (teachers, students, managers), considering the descriptors and databases used in the present review. In light of this, national (Moro et al., 2019; Vinha et al., 2017; Santos & Adam, 2022) and international (Umaña Altamirano, 2020; Vukičević et al., 2019) studies have pointed to the importance of research on school climate/environment that could encompass all agents, making it possible to investigate the perception of the school community in favor of a positive school climate. As for the schooling of the adolescents, there was a greater concentration of research from the 7th year of elementary school onward, which is consistent with the study by Moro et al. (2018), which mentions that students in the 6th year are sometimes experiencing many changes such as transferring schools, increasing the number of teachers and assessments. The next section details the studies.

Study design, analysis of results and language

As for the design of the studies, all studies presented a quantitative design and only one study (A5) used a mixed quantitative and qualitative design. The 16 studies are cross-sectional, that is, data was collected only once. Regarding the analyses of the results, 9 studies (A1, A2, A4, A5, A6, A11, A12, A14, A15) used statistical procedures with correlational analyses; one study (A10) presented multiple linear regression analysis; one study (A13) used association and comparison analysis; and finally, 2 studies (A8, A11) showed descriptive analyses of the results. Of the total studies, 4 (A1, A6, A10, A16) were published in Portuguese and 12 (A2, A3, A4, A5, A7, A8, A9, A11, A12, A13, A14, A15) in Spanish.

The methodological characteristics of the studies show that there is a greater concentration of studies using quantitative and cross-sectional methods. These studies include a wide range of research and their main purpose is to search for large population samples in a single time frame, since this investigation allows for the generalization of the results found (Creswell, 2010). Also, based on this review, it is noteworthy that Spanish-speaking countries are the ones that invest the most in research on school climate/environment, due to a global understanding of the influences of this climate on student development. The greatest evidence of research carried out in Chile is due to the large investment in educational quality at the basic and the higher education levels, since Chile is ranked among the ten countries that invest the most in education (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2022). The next section describes the instruments used to assess the school climate/environment.

Description of the instruments

Different instruments were identified for the specific assessment of school climate/environment. The articles selected did not mention the instrument’s comprehensive theoretical foundations of school climate. Fourteen different instruments were identified from the 16 articles analyzed. Four were built, validated and/or adapted in Brazil (School Climate Questionnaire, by Vinha et al. [2017]; Delaware School Climate Survey Scale - student version, by Holst [2014]; Biosociodemographic Questionnaire, by Genta et al. [2009]).

Table 2 specifies the type of instrument used for data collection (questionnaire, scale and its definition). We also seek to explain the definitions analyzed by dimensions that are the specific components that will be investigated or measured by the instruments, the definitions of the instrument (format, composition) and Cronbach’s alpha values. This value represents a measure of internal reliability of the instrument, which assesses the internal consistency of the responses to the instrument’s items. That is, it assesses how well these items correlate with each other. A Cronbach’s alpha value closer to 1 indicates greater internal consistency, that is, greater reliability of the results obtained with the instrument (Quero Virla, 2010).

TABLE 2 Instruments specification

| INSTRUMENT/AUTHOR/YEAR AND COUNTRY | DEFINITION | DIMENSIONS ANALYZED | INSTRUMENT CHARACTERISTICS | CRONBACH’S ALPHA VALUES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| School Climate Questionnaire Vinha et al. (2016) Brazil (A1) |

Aimed at students, teachers and managers, the instrument encompasses eight dimensions covering issues related to the reality of Brazilian schools. These dimensions include relationships with teaching and learning. | 1) Relationships with teaching and learning; 2) Social relations and conflicts at school; 3) Rules, sanctions and safety at school; 4) Bullying situations among students; 5) The family, the school and the community; 6) The school’s infrastructure and physical network; 7) Relationships with work; 8) Management and participation. |

The model uses clear and objective language, in which the response options are in the format of a Likert scale. Each item has four response possibilities, corresponding to a scale of 1 to 4 points. There are 123 items for students, 137 for teachers and 141 for managers. This scale ranges from low agreement to high agreement. |

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the total scale ranged between 0.80 and 0.90. |

| School Coexistence Questionnaire Case Niebla et al. (2013) Mexico (A2) |

The scale analyzes the relationships among students, student-teacher, student-principal relationship and school environment. | 1) Relationship among students (coexistence, communication, respect and cohesion); 2) Student-teacher relationship (communication, trust, coexistence, academic and personal support); 3) Student-principal relationship (coexistence, communication and trust); 4) School environment (discipline, physical conditions of the campus and violence within the campus). | The school climate scale has 24 questions, using the Likert format with five response options (1 = never, 2 = almost never, 3 = sometimes, 4 = almost always, 5 = always). The questions are organized in four dimensions with their respective indicators. |

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the total scale was 0.85. |

| School climate scale - Adapted for Chile Chile López et al. (2014) (A3) |

Developed and adapted in Chile for secondary school students, it analyzes students’ experiences in the schools. | 1) Clear rules; 2) Rules against violence; 3) Participation; 4) Social support. | It is a self-reported, Likert-type scale that measures school climate based on 4 factors and has 18 items. | The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the four dimensions ranged: from 0.84 to 0.85, for clear rules; from 0.86 to 0.88, for rules against violence; from 0.53 to 0.63, for participation and social support. |

| School Climate Scale (Inventory of School Climate - Student ISC-S) Chile Brand et al. (2003) (A4) and (A5) |

The scale is aimed at the school community and seeks to understand relationships, interactions, support and pluralism. | The dimensions are: 1) Teacher support (6 items); 2) Positive peer interaction (5 items); 3) Negative peer interaction; 4) Cultural support and pluralism (5 items). |

In the evaluation of the social dimensions of the school climate, four ISC-S scales (Brand et al., 2003) were used. The items on each of the scales follow a 5-point Likert-type response format, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (often). It consists of 21 items. |

The Cronbach’s alpha value for the total scale ranged from 0.65 to 0.79. |

| Biosociodemographic Questionnaire Brazil Genta et al. (2009) (A6) |

The questionnaire has eight questions about students’ perception of the school climate. | No dimensions. | Developed on a 3-point scale, ranging from 1 (yes, always) to 3 (no). Higher scores indicate a worse perception of the school environment (maximum possible score = 24). |

The Cronbach’s alpha value of the total scale was 0.66. |

| “What is Happening in this School?” Questionnaire (WHITS) Spain Aldridge et al. (2015) (A7) |

The instrument tries to capture the factors that correspond to a favorable environment for the prevention of aggressive behaviors in school, in relation to the role of teachers, colleagues, and educational and organizational strategies, which favor, as we commented, the prevention of these behaviors. | 1) Teacher support (4 items); 2) Connection with colleagues (3 items); 3) Connection with the school (4 items); 4) Affirmation of diversity (4 items); 5) Clarity of rules (4 items); 6) Inform and ask for help (4 items). |

It has 48 items, but we reduced the original scale to 23 items. Responses are formulated on a Likert numerical scale whose values range from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). | As for the reliability of the instrument, all the factors in the questionnaire showed an alpha above 0.70, except for the factors for connection with school (0.66) and connection with peers (0.68). |

| School Social Climate Questionnaire (CECSCE) Spain Trianes Torres and Gallardo Cruz (2004) (A8) |

It seeks to understand the school climate and the relationship with the institutions and the faculty and students. | 1) Climate related to the school institution (adequate comfort, peace in the institution, safety, ability to help...); 2) Climate related to the faculty and students (academic requirements, fairness, accessibility in treatment...). | A Likert-type scale with a minimum value of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was used. It consists of 14 items. | Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.78 for the school climate and 0.66 for the faculty climate. |

| School climate scale (CES; Spanish adaptation) Spain Fernández-Ballesteros and Sierra-Díez (1989) (A9) |

The scale seeks to understand the relationships between the school community and involvement in school tasks. | 1) Perception of teacher help; 2) Affiliation: friendship and help among students; 3) Involvement in school tasks. |

Composed of 30 items that measure the adolescents’ perception of the quality of the school climate (true-false). | Cronbach’s alpha values were: perception of teacher help (0.79); affiliation: friendship and help among students (0.86); and, involvement in school tasks (0.75). |

| Delaware School Climate Survey Scale - student version Brazil Horst (2014) (A10) |

The scale aims to understand relationships in the student’s perception. | 1) Teacher-student; 2) Student-student relationship; 3) Fairness of rules and clarity of expectations; 4) Safety at school; 5) Bullying; 6) Student engagement. | Instrument composed of 28 items (excluding 2 validity items) distributed in 6 subscales (teacher-student relationship; student-student relationship; fairness of rules and clarity of expectations; safety at school; bullying; and student engagement). Each subscale consists of 4 to 6 items, answered using a Likert scale with four response options, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). | Cronbach’s alpha value for the total scale was 0.86. |

| School Climate Assessment Questionnaire for Students Spain Gutiérrez et al. (2011) (A11) |

The questionnaire assesses the positive or negative perception of the school climate. | No dimensions. | Based on the questionnaire, we present the students’ perceptions of the school climate (whether positive or negative), the general climate of coexistence within the school grounds (whether positive or negative) and satisfaction and fulfillment of expectations (whether positive or negative). | The Cronbach’s alpha value has an internal consistency of 0.78, which indicates an adequate internal consistency in the scale distribution. |

| School Climate Scale, on an abridged version of the instrument. Costa Rica Aron et al. (2012) (A12) |

Set of scales aimed at understanding the teachers, school satisfaction and infrastructure assessment, among others. | 1) My teachers; 2) Satisfaction with the school; 3) Infrastructure assessment. | It consists of 82 items distributed over 5 subscales. The scale proposes a Likert-type response format, with 4 levels, which refer to the degree of agreement with each of the items’ statements. For the subscale “My teachers”, the levels are “all”, “most”, “few” or “none”. For the subscales “My colleagues” and “Infrastructure”, there are “always”, “almost always”, “rarely” or “never”. For the subscale “My school”, there are four levels of “agree”. | Cronbach’s alpha value for the total scale was 0.90. |

| School Social Climate Scale (ECLIS) Chile Aron and Milicic (1999) (A13) |

Using a scale, it shows the students’ perception of the social climate in the classroom. | 1) Teachers; 2) Classmates; 3) Perception and satisfaction with the school as an institution; 4) Satisfaction with the infrastructure. |

It consists of 82 items organized into 4 sub-scales designed to assess the perception of strengths and weaknesses in relation to 4 different areas: their teachers (30 items); classmates (15 items); perception and satisfaction with the school as an institution (10 items); and, satisfaction with the infrastructure (27 items). | The Cronbach’s Alpha value for the total scale ranged from 0.63 to 0.89. |

| School Social Climate (CES) Trickett and Moos (1974) Chile and Peru (A14) and (A15) |

The scale can provide information about how students relate to each other, how they engage in school activities, and the level of social connection they experience in class. | 1) Implication; 2) Help; 3) Affiliation. | It contains 45 items arranged on a Likert scale, where 1 means strongly disagree and 5 strongly agree. | Cronbach’s Alpha: Implication (0.71); Help (0.68); Affiliation (0.60). The total alpha is 0.76. |

| School Climate Questionnaire Brazil Veiga et al. (2004) A16 |

Analyzes the climate/environment and exchanges in the school context. | 1) Physical, pedagogical and social environment; 2) Rules; 3) Interpersonal relationships. | Instrument composed in the original form of 22 items evaluated on a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 6 = strongly agree). |

The Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency value was 0.91 (Physical, pedagogical and social environment: 0.86; Rules: 0.73; Interpersonal relationships: 0.76 - each factor calculated by the arithmetic sum of the values of its items). |

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on research data.

After analyzing the dimensions of the instruments that are used in research about the subject, those which assess school climate/environment play a significant role in understanding and improving the educational context. This is because such instruments provide important information about different aspects of the school climate/environment such as interpersonal relationships, social support, communication, safety and organization. They also make it possible to identify specific areas that need to be improved to create a more positive and productive environment for the school’s students and staff. With this information, measures can be implemented to create a safer, more inclusive and healthier environment for all (Parente et al., 2021). The next topic reports the word cloud.

Word cloud that includes the main results of the articles

The Iramuteq software was used to analyze the results. This software performed a word cloud analysis, indicating a corpus of 1,252 words. To arrive at this total, the relevant analysis options had to be selected to count the words. This involved choosing the “Word frequency” option in the analysis configuration.

After excluding meaningless words (adverbs, conjunctions, prepositions and pronouns), 480 words were identified. Regarding the results of the articles, the word cloud was used and it showed that the most repeated words were ”school climate” (n = 18); “perception” (n = 17); “social” (n = 17); “student” (n = 15); “relationship” (n = 14); “internet” (n = 9); “violence” (n = 9); “network” (n = 6); “dependence” (n = 6); “quality” (n = 5); “development” (n = 5); ”violent” (n = 5); “interpersonal” (n = 4); “autonomy” (n = 4); “coexistence” (n = 4); ”rule” (n = 4); “academic” (n = 4); “self-concept” (n = 4); “work” (n = 4); ”bullying” (n = 4); ”support” (n = 4); and “psychological” (n = 3).

The analysis reveals that the main keywords found in the research results, with a frequency of more than ten occurrences, are: “school climate”, “perception”, “social”, “student” and “relationship”. By advancing our understanding of these words, we were able to relate the objectives to the research results, as can be seen in the studies discussed below.

Study A14 aimed to relate the components of the relational factor of the school social climate (implication, affiliation and support) and the types of school violence (verbal, physical-behavioral, social exclusion). The results showed that the better the relationships of school coexistence present in the school social climate, the fewer events and types of violence occur at school. Study A11 determined the relationship between the perception of the school climate and the exercise of freedom of expression in high school adolescents at the Juan Misael Saracho National School in the city of Oruro, Bolivia. The research indicated that the factors associated with the exercise of freedom and the dimensions of the school climate are substantially related, as it was found that the better the school climate of general coexistence and the better the school climate of satisfaction and fulfillment of expectations, the greater the exercise of freedom of expression. Since the school allows students to participate democratically and freely, the adolescents’ perceptions of the school climate are satisfactory, as the majority perceive a positive environment.

These studies are in line with the research carried out by Vinha et al. (2016), who argued that positive relationships and freedom of expression are important. This means that when students are deprived of the opportunity to make decisions and discuss problems and situations in which they are involved, it becomes more challenging to develop an environment that supports collective well-being and responsible behavior.

The words identified in the range of 5 to 9 occurrences are “violence”, “network” and “internet”, “quality”, “development”, “violent”, “dependence”, “interpersonal”, “rule”, “self-concept” and “work”. It was found that violence is a result that is very present in the school climate/environment, so that in some studies it is associated with technology in general. These words suggest that research results may be linking violence and networking to a negative school climate/environment, and the development of social skills to an appropriate school climate/environment.

Study A9 aimed to analyze the relationships between dependence on social networks, school climate and online violence between adolescent partners (boy/girlfriends) from a gender perspective. The results showed that dependence on social networks and the internet is related significantly to the degree of online violence against the partner. As for the school environment, it can be inferred that the quality of the climate perceived by adolescent boys and girls is related to the degree of violence between partners exercised online, which means that in a positive school environment, in which there are healthy relationships, emotional support and violence prevention policies, it is more likely that there will be a lesser degree of online violence between partners. It can also be inferred that the interaction between partners violence and the student’s gender was not statistically significant. This result indicates that, during adolescence, online violence is equally related to poor school adjustment in both boys and girls.

Study A15 aimed to understand the relationship between social skills and the school climate of secondary school students in public educational institutions in Puerto Maldonado, Uruguay. It was observed that there is a moderate, direct and significant correlation between social skills and the school social climate, because as long as students have high levels of development in their social skills, the school social climate will be more suitable and conducive to the development of learning. On the other hand, having a limited repertoire of social skills worsens interpersonal relationships, generating conflict, disrespect and non-compliance with rules and agreements, which makes the work of the teacher more difficult.

Finally, the word cloud identified four occurrences of the words “autonomy”, “coexistence”, “bullying”, “psychological support” and “self-concept”. The word “bullying” was found to be related to the negative variable of climate, while the rest were associated with positive variables.

In fact, study A16 aimed to analyze the implications of peer violence in the school context, the school climate and the perception of development contexts on the subjective well-being of children and adolescents. It was concluded that the “bullying” typology (verbal, psychological, emotional) represents a risk/protective factor most associated with subjective well-being. In this sense, if the climate is favorable, it is characterized by a safe, welcoming and supportive environment, promoting healthy and respectful relationships. On the other hand, the unfavorable school climate, in which bullying may be more prevalent, can negatively affect adolescent mental health. In this sense, it is noteworthy that the victims of these violent acts can suffer important negative effects, including aversion to attending classes, drop in academic performance, anxiety, depression, social isolation, low self-esteem and even suicidal thoughts (Valdés Cuervo & Carlos Martínez, 2014). Study A14 related the components of the relational factor of the school climate (implication, affiliation and support) and the types of school violence (verbal, physical-behavioral, social exclusion). It was identified that the better the relationships of school coexistence present in the school climate, the fewer events and types of violence occur at school, improving coexistence, support and autonomy in this context.

As for study A15, it aimed to understand the relationship between social skills, the students’ school climate and the academic self-concept perceived by elementary and high school students from schools and colleges in the Metropolitan Region of Peru, enrolled in culturally diverse classrooms. It was found that the relationship between school climate, academic self-concept and perceived quality of life, as well as the explanatory value of the school climate and the perception of quality of life in the academic self-concept, also varies according to the nationality of the students. In addition, there is a significant relationship among the dimensions of assertiveness, communication, self-esteem, decision-making and the school social climate variable. Therefore, it can be seen that there are important correlations between the dimensions of social skills and the school climate.

In the study mentioned above, self-concept refers to a person’s perception and evaluation of themselves, including their beliefs, values, skills, physical characteristics, and personality traits. When the self-concept is positive, a person tends to have a healthy and confident view of themselves, which can keep their motivation, emotion and actions geared towards self-development. On the other hand, a negative self-concept can lead to feelings of inadequacy, low self-esteem and self-destructive behavior (Paiva & Lourenço, 2011).

In conclusion, these studies emphasize the importance of a positive school climate, healthy relationships and emotional support for the promotion of a healthy environment for adolescents. They also highlight the association between a negative school climate and the occurrence of violence, and the negative impacts on mental health. In addition, the studies highlight the influence and importance of aspects such as social skills, self-concept and perceived quality of life in the school context.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The present integrative literature review sought to map national and international scientific productions related to the school climate/environment, indicating the main concepts, methods (instruments, participants, designs) and variables investigated in the scientific productions about this construct, from 2019 to 2023.

A greater concentration of quantitative and cross-sectional research was found, which is characterized by a broad investigation based on large population samples in a single time frame, making it possible to generalize the results. In addition, the present study found that Spanish-speaking countries are the ones that invest the most in research involving school climate/environment, which is based on a global understanding of the influences of this construct on student development. In these studies, researchers use different instruments to assess school climate/environment.

School climate/environment can be understood as the perception of the quality of interactions at school, with impacts on students’ cognitive, social and psychological development, and can be positive or negative. A positive climate/environment is one marked by respect and support for individuals, capable of providing high-quality relationships in the social, environmental and emotional dimensions, and is linked to the quality of life provided to students, insofar as it builds a sense of well-being, self-confidence, motivation, learning, academic performance and belonging, for example. On the other hand, the school climate/environment is rated negatively due to the lack of support, or even the absence/non-existence of quality interactions between students and their peers, or students and teachers.

Limitations of the present study include the scarcity of research involving school climate/environment and specific instruments that have been built and validated in Brazil, such as the School Climate Questionnaire by Vinha et al. (2017). However, it is important to note that this instrument contains a large number of items, making the response procedure tiring for participants, especially when combined with other questionnaires. Therefore, it is suggested that future longitudinal research be carried out into effective interventions, which could include all school agents (students, teachers, managers, school staff), making it possible to understand the perception of the wider school community. It is also suggested that other questionnaires be developed and validated for national surveys. This review, therefore, points to the importance of studies involving the school climate/environment which, using different methodological designs, could make it possible to understand the different dimensions of the construct in favor of a positive school climate/environment.

HOW TO CITE:Danzmann, P. S., Silva, N. D. da, Silva, A. C. P. da, Vargas, L. G. de, Zappe, J. G., & Patias, N. D. Mapping scientific production on school climate: An integrative review. Estudos em Avaliação Educacional, 35, Article e10687. https://doi.org/10.18222/eae.v35.10687_en

NOTE:The authors produced this article collaboratively. Pâmela Schultz Danzmann, in particular, was responsible for a substantial part of the work, which included research, collaborative writing, data analysis, revisions and editing, as well as being involved in discussions, detailed bibliographic research, preparation for publication and collaborations with other authors. Natan Daniel da Silva, Ana Claudia Pinto da Silva and Lenon Goulart Vargas were involved in the process of detailed bibliographical research, data analysis and preparation for publication. The revisions and monitoring of the construction of the article were carried out by professors Jana Gonçalves Zappe and Naiana Dapieve Patias.

REFERENCES

Alcântara, S. C. de, González-Carrasco, M., Montserrat, C., Casas, F., Viñas-Poch, F., & Abreu, D. P. de. (2019). Violência entre pares, clima escolar e contextos de desenvolvimento: Suas implicações no bem-estar. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 24(2), 509-522. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232018242.01302017 [ Links ]

Aldridge, V. K., Dovey, T. M., Martin, C. I., & Meyer, C. (2015). Relative contributions of parent-perceived child characteristics to variation in child feeding behavior. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(1), 56-65. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21544 [ Links ]

Alvarado Calderón, K. (2022). Exploración de las relaciones entre clima escolar, satisfacción con la vida y empatía en adolescentes costarricenses. Revista Educación, 46(1), 205-220. https://doi.org/10.15517/revedu.v46i1.45127 [ Links ]

Araoz, E. G. E., & Uchasara, H. J. M. (2020). Habilidades sociales y clima social escolar en estudiantes de educación básica. Conrado, 16(76), 135-141. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?pid=S1990-86442020000500135&script=sci_arttext [ Links ]

Araújo, W. C. O. (2020). Recuperação da informação em saúde: Construção, modelos e estratégias. Onci: Convergências em Ciência da Informação, 3(2), 100-134. https://doi.org/10.33467/conci.v3i2.13447 [ Links ]

Aron, A. M., & Milicic, N. (1999). Clima social escolar y desarrollo personal: Un programa de mejoramiento. Andrés Bello. [ Links ]

Aron, A. M., Milicic, N., & Armijo, I. (2012). Clima social escolar: Una escala de evaluación - Escala de Clima Social Escolar, ECLIS. Universitas Psychologica, 11(3), 803-813. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S1657-92672012000300010&script=sci_arttext [ Links ]

Barreto Trujillo, F., & Álvarez Bermúdez, J. (2017). Clima escolar y rendimiento académico en estudiantes de preparatoria. Daena: International Journal of Good Conscience, 12(2), 31-44. http://www.spentamexico.org/v12-n2/A2.12(2)31-44.pdf [ Links ]

BBC News Brasil. (2023). Os dados que mostram explosão no número de ataques a escolas no Brasil. BBC News Brasil.https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/articles/ckryl4epnpeo [ Links ]

Brand, S., Felner, R., Shim, M., Seitsinger, A., & Dumas, T. (2003). Middle school improvement and reform: Development and validation of a school-level assessment of climate, cultural pluralism, and school safety. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(3), 570-588. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.3.570 [ Links ]

Calderón-González, N. G., & Vera-Noriega, J. Á. (2022). La valoración de estudiantes acerca del clima escolar, convivencia y violencia en escuelas secundarias del noroeste de México. Revista Electrónica Educare, 26(3), 186-201. https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.26-3.11 [ Links ]

Camargo, B. V., & Justo, A. M. (2013). Iramuteq: Um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais. Temas em Psicologia, 21(2), 513-518. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2013.2-16 [ Links ]

Campos Ancalle, M. A. (2020). Clima escolar y libertad de expresión en adolescentes. Ajayu, 18(1), 214-243. https://app.lpz.ucb.edu.bo/Publicaciones/Ajayu/v18n1/v18n1_a09.pdf [ Links ]

Caso Niebla, J., Díaz López, C. D., & Caso-López, A. C. (2013). Aplicación de un procedimiento para la optimización de la medida de la convivencia escolar. Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Educativa, 6(2), 137-145. https://revistas.uam.es/riee/article/view/3409 [ Links ]

Coelho, C. C. de A., & Dell’Aglio, D. B. (2019). Clima escolar e satisfação com a escola entre adolescentes de ensino médio. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 21(1), 248-264. [ Links ]

Costa, A. B., Fontanari, A. M., & Zoltowski, A. P. (2022). Como escrever um artigo de revisão sistemática: Um guia atualizado. In M. I. C. Sampaio, A. A. Z. P. Sabadini, & S. H. Koller (Orgs.), Produção científica: Um guia prático (pp. 130-165). Instituto de Psicologia da Universidade de São Paulo. [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. (2010). Projeto de pesquisa: Métodos qualitativo, quantitativo e misto (3a ed.). Artmed. [ Links ]

Cuadra-Martínez, D., Pérez-Zapata, D., Sandoval-Díaz, J., & Rubio-González, J. (2022). Clima escolar y factores asociados: Modelo predictivo de ecuaciones estructurales. Revista de Psicología (PUCP), 40(2), 685-709. http://dx.doi.org/10.18800/psico.202202.002 [ Links ]

Currie, C., Zanotti, C., Morgan, A., Currie, D., Looze, M., Roberts, C., Samdal, O., Smith, O. R. F., & Barnekow, V. (Eds.). (2012). Social determinants of health and well-being among young people - Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2009/2010 survey. WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/326406/9789289014236-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [ Links ]

Dessen, M. A., & Polonia, A. D. C. (2007). A família e a escola como contextos de desenvolvimento humano. Paidéia, 17(36), 21-32. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-863X2007000100003 [ Links ]

Félix, T., & Franzão, L. (2023). Por que ataques em escolas têm se repetido no Brasil? Especialistas analisam. CNN Brasil. https://www.cnnbrasil.com.br/nacional/por-que-ataques-em-escolas-tem-se-repetido-no-brasil-especialistas-analisam/ [ Links ]

Fernández-Ballesteros, R., & Sierra-Díez, B. (1989). Estudio factorial sobre la percepción del ambiente escolar. In R. Fernández-Ballesteros (Coord.), Intervención psicológica en contextos ambientales (pp. 143-176). Universidad de Murcia. [ Links ]

Genta, M. L., Brighi, A., & Guarini, A. (2009). European project on bullying and cyberbullying granted by Daphne II Programme. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 217(4), 233-239. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, M., Ruiz Pérez, L. M., & López, E. (2011). Clima motivacional en Educación Física: Concordancia entre las percepciones de los alumnos y las de sus profesores. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 20(2), 321-335. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2351/235122167006.pdf [ Links ]

Holst, B. (2014). Evidências de validade da escala de clima escolar Delaware School Climate Survey-Student (DSCS-S) no Brasil [Dissertação de mestrado, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul]. Repositório Institucional PUCRS. https://meriva.pucrs.br/dspace/handle/10923/7017 [ Links ]

Lahoz i Ubach, S. (2021). Clima escolar, autoconcepto académico y calidad de vida en alumnos/as de aulas culturalmente diversas. Estudios Pedagógicos (Valdivia), 47(1), 7-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07052021000100007 [ Links ]

Lahoz i Ubach, S., & Cuccia, C. C. (2021). Sensibilidad intercultural, clima escolar y contacto intergrupal en adolescentes de escuelas municipales de la Región Metropolitana de Santiago de Chile. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 39(1), 131-147. https://doi.org/10.6018/RIE.415921 [ Links ]

Leria-Dulčić, F. J., & Salgado-Roa, J. A. (2019). Efecto del clima social escolar en la satisfacción con la vida en estudiantes de primaria y secundaria. Revista Educación, 43(1), 364-379. https://doi.org/10.15517/revedu.v43i1.30019 [ Links ]

López, V., Bilbao, M. A., Ascorra, P., Moya Diez, I., & Morales, M. (2014). Escala de Clima Escolar: Adaptación al español y validación en estudiantes chilenos. Universitas Psychologica, 13(3), 1111-1122. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-3.ecea [ Links ]

Matos, M. G., & Carvalhosa, S. F. (2001). A saúde dos adolescentes: Ambiente escolar e bem-estar. Psicologia, Saúde e Doenças, 2(2), 43-53. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/362/36220203.pdf [ Links ]

Melim, M., & Pereira, B. O. (2013, 3-6 de julho). Violência, bullying e indisciplina na escola: Violência e clima escolar, uma intervenção global. In Anais do 9. Seminário Internacional de Educação Física, Lazer e Saúde. https://repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt/handle/1822/37556 [ Links ]

Melo, S. G. de, & Morais, A. de. (2019). Clima escolar como fator protetivo ao desempenho em condições socioeconômicas desfavoráveis. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 49(172), 10-34. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053145305 [ Links ]

Montero Carretero, C., & Cervelló Gimeno, E. M. (2019). Estudio de un modelo predictivo del clima escolar sobre el desarrollo del carácter y las conductas de bullying. ESE. Estudios sobre Educación, 37, 135-157. https://redined.educacion.gob.es/xmlui/handle/11162/219829 [ Links ]

Moro, A. (2020). A avaliação do clima escolar no Brasil: Construção, testagem e validação de questionários avaliativos. Appris. [ Links ]

Moro, A., Morais, A. de, Vinha, T. P., & Tognetta, L. R. P. (2018). Avaliação do clima escolar por estudantes e professores: Construção e validação de instrumentos de medida. Revista de Educação Pública, 27(64), 67-90. https://doi.org/10.29286/rep.v27i64.3733 [ Links ]

Moro, A., Vinha, T. P., & Morais, A. de. (2019). Avaliação do clima escolar: Construção e validação de instrumentos de medida. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 49(172), 312-334. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053146151 [ Links ]

Muñiz-Rivas, M., Callejas-Jerónimo, J. E., & Povedano-Díaz, A. (2020). La dependencia a las redes sociales virtuales y el clima escolar en la violencia de pareja en la adolescencia. International Journal of Sociology of Education, 9(2), 213-233. https://doi.org/10.17583/rise.2020.5203 [ Links ]

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2022). Education at a Glance 2022 (OECD Indicators). OECD. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/deliver/3197152b-en.pdf?itemId=/content/publication/3197152b-en&mimeType=pdf [ Links ]

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan - A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5, Article 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [ Links ]

Paiva, M. O. A. de, & Lourenço, A. A. (2011). Rendimento acadêmico: Influência do autoconceito e do ambiente de sala de aula. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 27(4), 393-402. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-37722011000400002 [ Links ]

Parente, E. M. P. R., Bataglia, P. U. R., & Castellini, T. S. J. (2021). Instrumentos de avaliação do clima escolar adaptados aos anos iniciais do ensino fundamental: Evidências de validação. Veras, 10(2), 293-319. http://dx.doi.org/10.14212/veras.vol10.n2.ano2020.art415 [ Links ]

Quero Virla, M. Q. (2010). Confiabilidad y coeficiente Alpha de Cronbach. Telos, 12(2), 248-252. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/993/99315569010.pdf [ Links ]

Sánchez, C. A. R., & Barría Ramírez, R. (2021). Contribución de la dimensión relacional del Clima Social Escolar (CES) a la Convivencia Escolar para la No Violencia (CENVI), desde la percepción de estudiantes de segundo ciclo y enseñanza media en escuelas y liceos municipalizados de Estación Central. Rumbos TS, 16(26), 167-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.51188/rrts.num26.573 [ Links ]

Sánchez, D. M., & Jiménez-Parra, J. F. (2022). Estilo interpersonal docente. Un análisis de perfil según las diferencias en motivación, necesidades psicológicas básicas, clima escolar y satisfacción con la enseñanza. SPORT TK-Revista EuroAmericana de Ciencias del Deporte, 11, Article 18. https://revistas.um.es/sportk/article/view/469701 [ Links ]

Santos, J. M. V., & Adam, J. M. (2022). Clima escolar: Perspectivas e possibilidades de análise. Editora Unesp. https://doi.org/10.7476/9786559542512 [ Links ]

Souza, M. A. R. de, Wall, M. L., Thuler, A. C. de M. C., Lowen, I. M. V., & Peres, A. M. (2018). O uso do software Iramuteq na análise de dados em pesquisas qualitativas. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 52, Artigo e03353. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1980-220X2017015003353 [ Links ]

Souza, M. T., Silva, M. D., & Carvalho, R. (2010). Revisão integrativa: O que é e como fazer. einstein, 8(1), 102-106. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1679-45082010rw1134 [ Links ]

Trianes Torres, M. V., & Gallardo Cruz, J. A. (2004). Psicología de la educación y del desarrollo en contextos escolares. Pirámide. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=5566 [ Links ]

Trickett, E. J., & Moos, R. H. (1974). Personal correlates of contrasting environments: Student satisfactions in high school classrooms. American Journal of Community Psychology, 2(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00894149 [ Links ]

Umaña Altamirano, M. J. (2020). Clima de convivencia escolar en el marco de la complejidad. Contextos: Estudios de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales, (47). http://revistas2.umce.cl/index.php/contextos/article/view/1566 [ Links ]

Valdés Cuervo, A. A., & Carlos Martínez, E. A. (2014). Relación entre el autoconcepto social, el clima familiar y el clima escolar con el bullying en estudiantes de secundarias. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 32(3), 447-457. https://doi.org/10.12804/apl32.03.2014.07 [ Links ]

Veiga, F. H., Antunes, J., Guerra, T. M., Moura, H. M., Fernandes, L., & Roque, P. (2004). Clima de escola: Uma escala de avaliação (CLES). In Anais da 10. Conferência Internacional de Avaliação Psicológica: Formas e Contextos (pp. 545-550). Universidade do Minho. [ Links ]

Vinha, T. P., Morais, A. de, & Moro, A. (2017). Manual de orientação para a aplicação dos questionários que avaliam o clima escolar. FE/Unicamp. http://www.bibliotecadigital.unicamp.br/document/?code=79559&opt=1 [ Links ]

Vinha, T. P., Morais, A. de, Tognetta, L. R. P., Azzi, R. G., Aragão, A. M. F. de, Marques, C. de A. E., Silva, L. M. F. da, Moro, A., Vivaldi, F. M. de C., Ramos, A. de M., Oliveira, M. T. A., & Bozza, T. C. L. (2016). O clima escolar e a convivência respeitosa nas instituições educativas. Estudos em Avaliação Educacional, 27(64), 96-127. https://doi.org/10.18222/eae.v27i64.3747 [ Links ]

Vinha, T. P., Tognetta, L. R. P., Azzi, R. G., Moro, A., Aragão, A. M. F. de, & Morais, A. de. (2018). O clima escolar na perspectiva dos alunos de escolas públicas. Revista Educação e Cultura Contemporânea, 15(40), 163-186. https://mestradoedoutoradoestacio.periodicoscientificos.com.br/index.php/reeduc/article/view/1830 [ Links ]

Vukičević, J. P., Prpić, M., & Mraović, I. C. (2019). Perceptions of school climate by students and teachers in secondary schools in Croatia. Journal of Contemporary Educational Studies/Sodobna Pedagogika, 70(4), 192-219. https://www.sodobna-pedagogika.net/en/articles/04-2019_perceptions-of-school-climate-by-students-and-teachers-in-secondary-schools-in-croatia/ [ Links ]

Welter, L. dos S., Vasconcellos, S. J. L., Barbosa, T. P., Lucchese, V. C., & Steffler, H. T. (2022). Assassinatos em massa: Uma pesquisa documental. Psico, 53(1), Artigo e38921. https://doi.org/10.15448/1980-8623.2022.1.38921 [ Links ]

Wendt, G. W., Silva, M. A., & Koller, S. H. (2020). Tecnologias da informação e comunicação em adolescentes, práticas parentais e percepção de clima escolar: Uma abordagem multinível. Interação em Psicologia, 24(1), 66-75. http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/psi.v24i1.64907 [ Links ]

World Health Organization (WHO). (2013). Adolescent health. WHO. https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1 [ Links ]

Wrege, M. G. (2017). Um olhar sobre o clima escolar e a intimidação: Contribuições da psicologia moral [Tese de doutorado, Universidade Estadual de Campinas]. Repositório da Produção Científica e Intelectual da Unicamp. https://doi.org/10.47749/T/UNICAMP.2017.981860 [ Links ]

Received: October 30, 2023; Accepted: December 06, 2023

texto en

texto en