Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Acta Scientiarum. Education

versión impresa ISSN 2178-5198versión On-line ISSN 2178-5201

Acta Educ. vol.46 no.1 Maringá 2024 Epub 01-Dic-2023

https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v46i1.68060

TEACHERS' FORMATION AND PUBLIC POLICY

Populisms and identity(ies). A relevant content in the teaching of Social Sciences

1Universidad de Sevilla, España.

The rise of populism is a serious problem for democracy. These movements appeal to simplifying ideas of identity based on cultural clichés. We start from the hypothesis that this type of elementary and poorly elaborated discourse connects better with the population than other more democratic and critical discourses, which require a greater complexity of reasoning, and which go hand in hand with the development of a greater critical conscience. This situation is particularly serious in the case of teachers who, in the final analysis, are responsible for a large part of the political education of future generations. The research presented here explores this hypothesis in a group of 80 students of the Primary Education Degree of the University of Seville by means of a questionnaire of open and closed questions. The results of the study allow us to affirm that students in initial training give little relevance to politics to explain the construction of their identities. They largely justify that element closer to them (social, linguistic, local, or territorial) have a greater influence on the construction of their identities. This, in addition, conditions the practical perspectives they have on how identities should be worked on in the primary education classroom, giving priority to a vision of teaching linked to the territory and local culture. In conclusion, it is necessary for training models to consider the approach to politics as a relevant issue both in the identities of young future teachers and in the work on identities with children in primary education.

Keywords: identities; teaching identities; political education; preservice teachers; populism

El auge de los populismos es un grave problema para la democracia. Estos movimientos apelan a ideas simplificadoras de la identidad basadas en tópicos culturales. Partimos de la hipótesis de que este tipo de discursos elementales y poco elaborados conectan mejor con la población que otros más democráticos y críticos, que requieren una mayor complejidad de razonamiento y que van unidos al desarrollo de una mayor conciencia crítica. Esta situación es especialmente grave en el caso de los docentes que, en definitiva, son los encargados de gran parte de la formación política de las futuras generaciones. La investigación que se presenta explora esta hipótesis en un grupo de 80 estudiantes del Grado de Educación Primaria de la Universidad de Sevilla mediante un cuestionario de preguntas abiertas y cerradas. Los resultados del estudio nos permiten afirmar que los estudiantes en formación inicial dan poca relevancia a la política para explicar la construcción de sus identidades. En gran medida justifican que elementos más cercanos a ellos (social, lingüístico, local o territorial) influyen más en la construcción de sus identidades. Esto, además, condiciona las perspectivas prácticas que tienen sobre cómo deben trabajarse las identidades en el aula de Educación Primaria, primando una visión sobre la enseñanza vinculada al territorio y cultura local. En conclusión, es necesario que los modelos formativos consideren el abordaje de la política como cuestión relevante tanto en las identidades de los jóvenes futuros maestros como en el trabajo de las identidades con niños y niñas de Educación Primaria.

Palabras clave: identidades; enseñanza de las identidades; educación política; formación inicial de docentes; populismos

A ascensão do populismo é um problema sério para a democracia. Estes movimentos apelam a ideias simplificadoras de identidade baseadas em clichés culturais. Partimos da hipótese de que este tipo de discurso elementar e pouco elaborado se relaciona melhor com a população do que outros discursos mais democráticos e críticos, que exigem uma maior complexidade de raciocínio e que são acompanhados pelo desenvolvimento de uma maior consciência crítica. Esta situação é particularmente grave no caso dos professores, que são, em última análise, responsáveis por grande parte da educação política das gerações futuras. A investigação aqui apresentada explora esta hipótese num grupo de 80 alunos da Licenciatura em Educação Básica da Universidade de Sevilha, através de um questionário de perguntas abertas e fechadas. Os resultados do estudo permitem-nos afirmar que os alunos em formação inicial dão pouca relevância à política para explicar a construção das suas identidades. Em grande medida, justificam que os elementos que lhes são mais próximos (sociais, linguísticos, locais ou territoriais) têm maior influência na construção das suas identidades. Este facto condiciona, aliás, as perspectivas práticas que têm sobre a forma como as identidades devem ser trabalhadas na sala de aula do ensino básico, privilegiando uma visão de ensino ligada ao território e à cultura locais. Em conclusão, é necessário que os modelos de formação considerem a abordagem da política como uma questão relevante tanto nas identidades dos jovens futuros professores como no trabalho sobre as identidades com as crianças no ensino básico.

Palavras-chave: identidades; identidades docentes; educação política; formação inicial de professores; populismos

Introduction. Identity(ies) and their construction under discussion

The reality of an increasingly globalized world in which a majority and uniform culture is imposed, means that identities are under constant debate and, in many cases, lead them to try to reaffirm themselves for the sake of preserving certain cultural values (Banks, 2017).

Undoubtedly, the question of identity is key to the construction of social cohesion and stability, as it allows individuals to define themselves and link with their reference groups. However, it requires careful educational treatment, since its changing, dynamic, and multiple nature makes it, in any case, a complex and diffuse field (Valdés, Oller, & Labraña, 2016).

Moreover, just as identity allows us to build ourselves, together with some, it also makes us differentiate ourselves from others (Kriger & Cid, 2017). Thus, as stated by Santisteban & Pagès (2007, p. 6) there is no identity without otherness, i.e. "[...] we define ourselves in terms of differences with other people". The elements we use to highlight these differences range from the territory itself, culture, our origin, religion, etc. Throughout the history of humanity, and at present, there have been numerous problems and conflicts between human groups based on their identities (Giménez, 2004). These conflicts usually derive from attempts to affirm some identities over others, as superior, which has led to the subjugation of identities belonging to minority groups by others that become hegemonic or dominant, because they belong to more powerful groups, as for example has occurred historically in the case of the conquests of some peoples over others.

In the study developed by Sant, Davies, and Santisteban (2016) with Secondary Education students in England and Catalonia, it is shown that in the English context, adolescents have a subjective view of their identities, that is, they attribute to it a personal elaboration constructed in interaction with others. However, the Catalan students in this same study show visions of their identities linked to a legal status externally attributed and associated to the territory.

At the level of teaching and teacher training, work on identities is key. Previous studies have shown how teachers' conceptions and representations of their own construction of their identities have an impact on their practical perspectives on their teaching (Tosello, 2018). In the study developed by Tosello (2018) with teachers in different countries, the result is that most teachers have a view of identities as characteristics or traits of a group rather than as a social construction, thus ignoring their dynamic nature.

This has a direct influence on teaching, as it perpetuates an essentialist or cultural nation vision (Serrano, & Facal, 2012), favoring that identity traits are also inherited without questioning. The lack of critical reflection on this issue in initial and continuing teacher training has two serious consequences.

The first is that teachers themselves teach based on their own experiences in the construction of their own identity, be it more or less critical. Therefore, rather than reconstructing in a reflective and critical way, identities are 'inherited' or uncritically 'transmitted' as something finished and immutable, moving away from offering students the skills to "[...] examine, critique and revise past traditions, existing social practices and problem solving" (Ross, 2004, p. 250).

The second is that the issues worked on in the classroom do not tend to be analyzed from the point of view of the various identities involved, but rather from that of the dominant one, which means that minority groups continue to be made invisible and some cultures are subordinated to others. This occurs, for example, in the Spanish context in the teaching of the 'discovery' of America, in which a vision that legitimizes a Eurocentric and colonizing identity prevails and, in turn, eliminates the identity valuation of the original peoples of the American continent (Cordes & Sabzalian, 2020).

Both issues have an impact on the teaching of coexistence and democratic culture, on the development of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values linked to appreciating cultural diversity, respecting other worldviews, and protecting democracy and social justice as public and common goods (Ross, 2004; Kahne & Westheimer, 2014; Kennedy, 2019). Democracy, not as an abstract and static concept, but as a dynamic and complex one, is also linked to the identity of peoples and groups (Apple et al., 2022). Now we consider its open character, we understand following Biesta (2016, p. 26) that:

Democracy, therefore, is not only a rupture of the existing order, but an interruption that translates into a reconfiguration of this new order into one in which there are new ways of being and acting and where new identities come into play.

From this conception we can begin to build hope in the future, in the transformation and achievement of more coexistent and respectful spaces. This vision is, if possible, even more important in recent times. Contemporary history, and unfortunately very current events, show us that identities are also used negatively to justify anti-democratic actions through hate speeches. The situation is even more serious if we consider that in democratic states it is legitimized even by the institutions themselves, both at international and national level. Clear examples are the immigration problems in the United States or the conflict between Spain and Morocco with the Melilla border fence. Nor can we forget that there are political groups that use hate speech for their own benefit and that, on most occasions, those affected are vulnerable groups (girls, boys, women, or immigrants, among others). Is it possible and, above all, desirable, therefore, to work on identities outside our own political identity?

Political education, identities and populisms

"When social sciences are taught, political decisions are made, with politics understood as a process of coexistence and social organization, as a way of understanding power and the solution of social conflicts" (Santisteban, 2021, p. 240).

As Santisteban (2021) argues, teaching social sciences involves making political decisions. The political education of citizenship is always open to discussion. In the face of this, there are simplistic ideas that defend a false neutrality when it comes to the didactic decisions made in the classroom (Westheimer, 2019). Working on identities from the Social Sciences also requires critically educating our students considering that "[...] the values, knowledge and procedures of political education, [must be] taught from topics that [problematize] aspects close to the lives of students, children and young people" (Santisteban, 2021, p. 239). In this sense, and following Sant's (2021) perspective, we understand political education "[...] as a purpose of education and not as a subject or curricular area" (Santisteban, 2021, p. 139). However, there are some curricular areas, such as Social Sciences, which by their own idiosyncrasy cannot obviate this issue within their contents.

The political education of young people is even more urgent if we consider that there is a political disaffection of young people towards the institutional sphere (Morán & Benedicto, 2016). This disaffection has several origins, among which stand out a generalized conception of weak citizenship and disconnected from the daily experiences of young people as opposed to the protagonism that institutions have. Educating students politically involves contemplating, from the individual level, the critical thinking already mentioned above. At the social and identity level, it requires strengthening the links with the community to which they belong. From this perspective, "[...] participation only acquires its true socio-political relevance to the extent that we recognize that the processes of involvement are one of the main ways in which citizens make their links with their community of belonging a reality" (Morán & Benedicto, 2016, p. 17).

In this sense, from the Social Sciences there is a special responsibility because, for example, since its emergence, the teaching of history has been closely linked to the nationalist discourse (Grever & van der Vlies, 2017; Pagès & Sant, 2015; Serrano & Facal, 2012). This type of discourse traditionally appeals to a vision of national identity of an exclusionary nature, derived from a teaching "[...] centered on the values of patriotism, of the nation, and of conservative and liberal ideologies" (Pagès, 2015, p. 20).

Currently we observe an increase in populist nationalisms in which, among other issues, local and cultural elements are instrumentalized to use them in pursuit of a preservation and even exaggeration of the identity traits of the nation. Westheimer (2019) argues that there is a high percentage of young people willing to accept non-democratic forms of government and that, in a way, this derives from the fact that in schools the conception of citizenship is worked in a diffuse way and focused on good behavior and patriotism, leaving aside the development of critical thinking and participation.

Although there are studies that show that those who attain a university degree are less likely to support populist discourses (Sant & Brown, 2020), in terms of teacher training we should continue to focus on this issue, since in addition to young people with the capacity to actively participate in public life, they will also be responsible for the training of future generations.

In this study we start from the hypothesis that nationalist populisms appeal to a vision of identities linked to territory, traditions, and culture. These issues, which are usually more neutral and require less political positioning, connect better with citizens and youth. From our perspective, traditional cultural identity is a richness for peoples as it allows us to explain our roots and particularities, as well as to appreciate that of others. However, the lack of agreement on how to politically educate our students means that the work in schools remains diffuse and, in some cases, nonexistent (Ross, 2004; Westheimer, 2019). Hence the relevance of working on identities from a broad and critical plane.

Methodology

Studying the construction of the identities of teachers in pre-service training is key to know what their perception of the configuration of these identities is, and what role they give to the political question. In turn, in relation to the above, it is also relevant to approach their practical perspectives on the teaching of identities at school, to know what importance they attach to the formation of the political identity of boys and girls.

Through an interpretative and critical research (Creswell, 2014) we intend to delve into both issues, considering that the participants in the study meet the condition of young people and future teachers. Knowing and analyzing their perspectives helps us, on the one hand, to interpret the issue itself. On the other hand, as teacher educators, it allows us to be critical of our own training strategies, in the sense of exploring new ways of intervention in initial teacher training that favor the construction of a critical and participatory citizenship that, in turn, can favor the construction of diverse identities from childhood.

The problems we pose, in line with what has been commented above, are threefold:

What identity elements do students in initial training select as most relevant, and what arguments do they give for their selection?

What role do they give to political education in connection with the work on identities at school? What arguments do they give for their selection?

What topics do they select to work on identities in the classroom?

What contents do they propose to work on identities in the classroom?

What types of activities are designed to work on identities in the classroom?

What relationships exist between the conceptions about the construction of their own identities and the practical approach to teaching them?

Participants

The research involved 80 students in initial training for the Degree in Primary Education at the University of Seville. As shown in Table 1, the majority are women (71.3%) and reside in Seville capital (38.8%) and province (51.2%). Seville is one of the eight cities that make up the Autonomous Community of Andalusia, in southern Spain. All the participants in the study were born in Spain, although in some cases their relatives were born in other countries such as Germany, Scotland, or Mexico. Considering that the study delves into identities, we first considered keeping these contextual variables to better understand the cultural, contextual, and social experiences lived by the participants. The participants in the study signed a commitment to confidentiality and voluntary participation in the study, which complies with the requirements of the regulations of the Ethics Committee of the University of Seville.

Table 1 Characteristics of the participants.

| F | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 23 | 28.7% |

| Female | 57 | 71.3% | |

| Place of residence | Seville city | 31 | 38.8% |

| Sevilla province | 41 | 51.2% | |

| Huelva | 4 | 5% | |

| Cadiz | 2 | 2.5% | |

| Caceres | 1 | 1.3% | |

| Galicia | 1 | 1.3% | |

| Country of birth | Spain | 80 | 100% |

| Country of birth family members | Spain | 76 | 95% |

| Spain and Germany | 2 | 2.5% | |

| Spain and Scotland | 1 | 1.3% | |

| Spain and Mexico | 1 | 1.3% | |

Source: own elaboration.

Instrument and data analysis

To approach the students' reality, we used a questionnaire of open and closed questions, of a reflective nature. The objective is to allow students to reflect on the issues discussed above. For this reason, the questionnaire has two parts. One linked to the construction of their identities and the other to the practical perspectives on their teaching in the classroom. The questionnaire is carried out as an activity of previous ideas in the classroom. This strategy allows us, on the one hand, not to condition the answers and, on the other hand, to consider the results to deepen the possible difficulties found.

Quantitative and qualitative techniques were combined for data analysis. The quantitative techniques are based on a descriptive and frequency analysis of the closed-ended responses. For the qualitative analysis we relied on the principles of grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 2002). For this purpose, we carried out a two-phase coding process:

1) Open coding. This consisted of identifying Significant Information Units (SIU) for each of the problems under investigation. Two families of codes emerge: conceptions on the construction of their identities and their justification; practical perspectives on the work of identities in the classroom (themes, contents, and activities). A total of 460 citations resulted.

2) Axial coding. Subsequently, we established relationships between the two groups of families to know the existing relationships between the conceptions on the construction of their identities and the practical perspectives on their teaching.

The identities of teachers in pre-service training

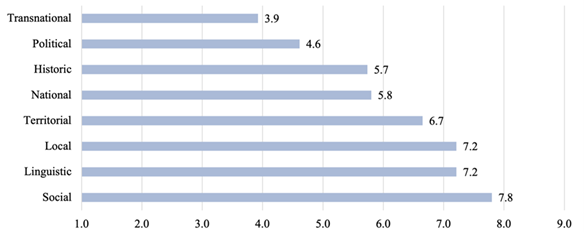

Identities are currently influenced by multiple elements, including politics. As shown in Figure 1, the pre-service training teachers participating in this study, when ordering the different elements that define their identities (where 1 is not important at all and 9 is very important), consider that the issues that most influence their definition are linked to social (7.8), linguistic (7.2), local (7.2) and territorial (6.7) elements. It is striking that the issues they perceive as least explanatory in the construction of their identities refer to transnational (3.9) and political (4.6) elements.

The explanations provided by the students to justify their selection have allowed us to establish a typology of arguments: uncritical; personal preference; closeness; political closeness and disaffection; and multiple interaction (Table 2).

As shown in Figure 2, the most frequent typologies are by proximity (45.1%), by multiple interaction (22%) or by personal preferences (17.1%). It is noteworthy that 11% are in the typology 'closeness and political disaffection'.

Table 2 Typology of arguments and representative quotations.

| Type | Description | Allusion quotation |

| Acritical | Does not argue anything | "Because I think they are necessary to form our identity" (13:7). |

| Personal preference | Elements are selected by personal preferences | "Because I think they are the ones that most define me as a person and are closest to who I am" (2:7) |

| Closeness | Nearby elements (local, territorial) have more importance | "Because what is closest is what can affect us the most" (39:6). |

| Political closeness and disaffection | Close (local, territorial) elements have more importance. The policy is far from themselves | "The social element I think is of vital importance because I believe that the human being must, and in fact knows no other way, live in society. Then, the linguistic elements are essential to be a cultured person, to be able to dialogue, to communicate.... Next, I have selected local and territorial elements because they are undoubtedly the ones, I identify with more than the national or transnational element. On the contrary, I think that politics, although it is very important and is my own ideology, is an element that is very tainted and damaged, so sometimes I think it would be better not to think about it" (75:7). |

| Multiple interaction | Elements interact with each other, although some elements are given more relevance over others | "I think my identity is influenced to some extent by my ideals and principles and that has a translation into politics, it is also influenced to a large extent by where I live; my neighborhood, friends and family as they have a lot of importance in my life, and I care what they think of me. I think that the historical and the past also influences, but less. On the other hand, what happens in my country worries me and I feel that it can affect me on a personal level, although not as much as the social, I think it mostly defines me my relationships with the rest of the people and how I behave with them. The transnational, however, I think it hardly has any influence on my identity, but I don't know how to explain it either" (8:7). |

Source: Own elaboration.

The teaching of identities, also political? in elementary school

To respond to the second research problem, we have analyzed the practical perspectives of pre-service training teachers to address the work on identities in the Primary Education classroom. Figure 3 shows those elements they consider most relevant for working on identities with their students (1 is not at all important and 8 is very important). It can be seen how the elements they consider most relevant are linked to local issues such as territory (6), language (5.9) and heritage (5.7). To a lesser extent, they consider political participation (2.7), religion (3.5) and art (3.7).

The justification for the selection of some elements over others has also allowed us to establish a typology of visions on the teaching of identities (Table 3): vision of uncritical teaching; vision linked to local territory and culture; vision linked to territory and culture (local-national interaction); and critical vision.

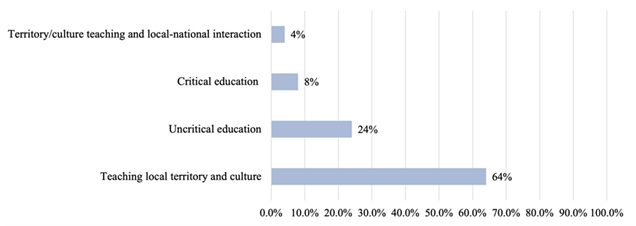

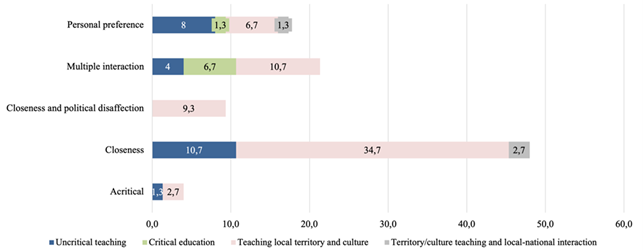

Of this typology, as shown in Figure 4, the most frequent is a vision on teaching identities linked to local territory and culture (64%), followed by a vision on uncritical teaching (24%). Critical visions (8%) or visions that relate local and national issues (4%) are in the minority.

Table 3 Typology of visions on teaching identities.

| Tipology visions of teaching identities | Description | Allusion quotations |

| Acritical | Justifies selection based on personal preferences | "Because I think that with this order more information could be extracted and related to other topics to get to know the identities of my students" (30:8). |

| Linked to local territory and culture | Justifies selection on territorial and cultural grounds | "In the first place, I have highlighted the Andalusian territory since it is main that they know the territory in which they live to know about their identity. The expressions of each region of Andalusia seems interesting to me so that the students can see the number of variants that can be produced in the identity of the people according to the area of our autonomous community, seeing evidenced that each place has its customs starting with the expressions in communication. Another important and primordial point in the formation of identity is the difference between rural and urban areas. Finally, it is important to highlight customs such as the taste for Easter (religious beliefs) or the importance of traditions such as flamenco to understand where we come from to create our identity" (70:4). |

| Linked to territory and culture (local-national interaction) | Justifies selection on territorial grounds in interaction from local to national (Seville, Andalusia, Spain). | "I have followed this order because in order to work on the theme of identity it is first important to put ourselves in situation with the environment that surrounds us (Spain, Andalusia...). Once we have put ourselves in situation, we begin by detailing the most characteristic aspects of the community such as the parliament, flamenco, olive trees, holy week etc." (4:8) |

| Critical | Justifies selection based on a multiple and critical vision of identities. It should be worked from different areas and considering its dynamism. | "Because politics is the aspect that affects us most directly in the present and has the greatest impact on the future" (18:8). |

Source: Own elaboration.

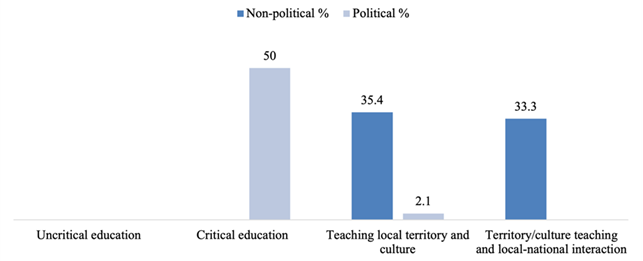

Of these visions, some of the students explicitly state whether they would address political identity with their students (Figure 5).

As can be seen in Figure 5, those who have a vision linked to local teaching and territory explicitly state that political identity should not be worked on (35.4%). They justify this for various reasons:

It is a difficult aspect to assimilate in childhood: "In last place I have left the political aspect, since I consider that it is something that is not so clearly assimilated when we are children. That is why it does not carry so much weight in my opinion from the beginning" (52:8).

The topic is complicated to work on at the Elementary Education stage: "In last place I would put the political aspect, since I think, it is complicated to deal with the topic with Primary School children" (77:8).

Children do not understand politics: "From my experience, politics can influence people's identity, but being of a more adult age, children so young do not understand politics, although it can indirectly influence them because of their parents' politics" (11:7).

Children do not identify with politics: "What I think is less important and why I don't think it should be important to work on identification is politics or government, because most of them don't identify with it" (12:8).

Something similar occurs with those students who have a vision of teaching linked to territory and culture in interaction of local and national elements (33.3%). On the contrary, those who have a critical view of the teaching of identities, declare to a greater extent the relevance of also working on identities from the political level, due to their present and future importance (50%): "Politics is the aspect that affects us most directly in the present and has the greatest impact on the future" (18:8). However, some of them also have a more disciplinary view of the work on politics from the perspective of knowing the forms of government and institutional political participation: "For me, the form of government, as well as the political actions that are taken, influences us all, and the children have to know how the territory in which they live is governed" (29:7). It would be convenient to address this question in greater depth to analyze what they understand by politics.

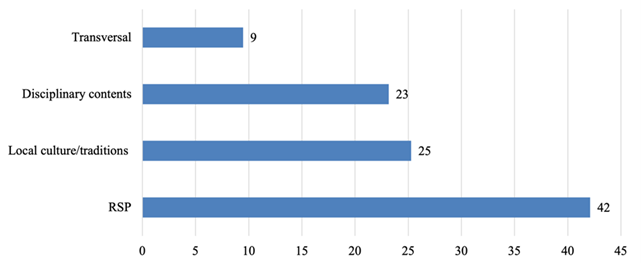

As for the topics they select to work on identities in the classroom, the most frequent, as shown in Figure 6, is to select disciplinary content (58%). This is closely related to the elements previously selected to work on identities in the classroom and explains a persistence of practical perspectives on the teaching of identities linked to local or disciplinary issues, which could be considered less controversial than working on Relevant Social and/or political Problems (RSP).

The selected of RSP (42%) are mostly linked to issues related to racism (12.7%), gender (8.9%), cultural diversity (6.3%) or climate change (6.3%). Examples of allusions to these are shown in Table 4.

However, the disciplinary contents are mostly linked to Andalusian culture and traditions (8.7%), Andalusian dialect (7.2%), flamenco (7.2%), Andalusian territory (4.3%), local popular festivals (4.3%) or Andalusian monuments (4.3%) (Table 5).

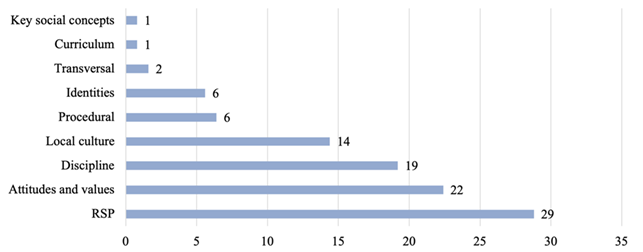

When they specify the contents (Figure 7) that they will work on with this topic, most of them allude again to RSP (29%), attitudes and values (22%), disciplinary issues (19%) or local culture (14%), among others. This suggests three main models of teaching identities with respect to content: a model based on the work of PSR, a model based on the development of attitudes and values, and a model based on the work of disciplinary issues.

Table 4 Examples of the most frequent RSP allusion.

| RSP | Allusion quotations |

| Racism | "As a cultural problem I would like to work on racism, and I also think that it can be very useful for students in the development of empathy" (68:3). |

| Gender | "Gender difference" (39:2). |

| Cultural diversity | "One of the issues that I think are vital for children to learn and understand from a very early age are cultural issues, that is, we are all equal regardless of where we come from, we are all people" (13:3). |

| Climate change | "Climate change, their ideas about it and their ways of acting on it" (49:3). |

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 5 Examples of the most frequent local culture/traditions allusion.

| Local culture/Traditions | Allusion quotations |

| Andalusian culture and traditions | "I would select topics such as the culture of Andalusia..." (36:3). |

| Flamenco | "Flamenco as intangible heritage of humanity (in which you can even include topics from literature such as Federico García Lorca)" (62:3). |

| Andalusian dialect | "Style of speech that exists in Andalusia (lisp, seseo, jejeo) and typical words from here" (58:3). |

Source: Own elaboration.

The type of activities (Figure 8) presented to work on identities in the classroom are mostly based on activities that involve researching the environment (24%), followed by activities involving debates and reflection (16%), activities that involve creating, manipulating, or experimenting (14%) or activities focused on the critical analysis of information (10%). Although research activities in the environment stand out as the most frequent, it is striking that activities involving participation in the environment (1%), activities based on the children's previous experiences and ideas (3%) or activities that favor proposals for solutions or action on their reality (4%) are hardly considered. This leads us to think again about the need to approach the teaching of identities from a more practical and reality-related perspective. To form citizen and political identity is also to participate with and from the environment.

The construction of identities as a key to understanding practical perspectives on their teaching

We have previously considered, on the one hand, the question of the construction of identities and, on the other, their practical approach at the classroom level. However, if we compare the data on both issues, we can see relationships between the two aspects. As can be seen in Figure 9, there is a greater number of students who justify proximity as a key to explaining their identity; likewise, the greatest number of them have a practical perspective on their approach in the Primary Education classroom linked to the teaching of the territory and local culture (34.7%) and to an uncritical teaching (10.7%). On the other hand, those who justify that the construction of their identities is due to the multiple interaction of different elements, although most of them (10.7%) also have a practical perspective related to the teaching of territory and local culture, present the greatest number of justifications linked to the need to approach it from a more critical teaching (6.7%).

Figure 9 Relationship between vision and construction of identities and their teaching. Source: Own elaboration.

These results confirm that there is a relationship between the perception that students in pre-service training have about the construction of their own identities and their practical perspectives on their teaching. From a formative point of view, it is key to consider this issue to move towards a more critical model.

Conclusion

The study allows us to approach the ideas and representations of teachers in pre-service training on the construction of their own identities and their teaching. As the results show, the teachers in the study have a vision of the construction of their identities linked to issues closer to them (social, linguistic, local, or territorial elements) than to more distant or abstract issues (transnational or political elements).

It is noteworthy that, when arguing why they consider some elements more representative than others in defining their identity, the majority refer to the fact that the elements close to them may affect them more (45.1%). Others, in addition to the latter, add that politics is far from themselves (11%) hinting at a certain disaffection on this issue. According to Morán & Benedicto (2016, p. 19) the manifestations of political disaffection in young people are usually linked to institutional politics and "[...] lies in the widespread perception that it does not care about their problems and that politicians do not pay attention to their demands and needs". This could have serious consequences, since populist and nationalist discourses, linked to immobilism and essentialism, may have more chances of success in the eyes of young people with an uncritical view of their identities. In the face of this, they may come to feel the complex political discourse as detached from the construction of their own identity. Therefore, it is key to continue strengthening the political identity of young people, considering that it is fundamental for our democracy to build a critical and participatory citizenship (Biesta, 2016; Westheimer, 2019). To this end, it is necessary to explore what young people's conception of politics is, as well as the ways of political and democratic participation that exist beyond the institutional (such as voting).

Similarly, a minority considers that the construction of their identities depends on the interaction of multiple factors (22%). Therefore, on the one hand, the perception about the construction of their identities is linked more to the local territory and, on the other hand, there is a lack of reflection on the dynamic and interactive nature of identities. Already in the study developed Sant et al. (2016) it is shown that Catalan students have a vision of their identities linked to the territory unlike English students who attribute a more interactive character to it. Similarly, the research by Tosello (2018) reflects how teachers have a static view of identities, ignoring their dynamic and changing nature.

In addition, the study allows us to observe a direct relationship between the perceptions of teachers in training on the construction of their identities (linked to nearby and static elements) and uncritical conceptions of teaching, based on the perpetuation of discourses through isolated disciplinary contents, as opposed to problematization and questioning. Thus, 64% of the students in pre-service training consider that identities should be worked on in the classroom linked to the territory and local culture. On this issue, it is important to point out that those who have an uncritical view of teaching identities do not consider working on political issues in any case. However, those who position themselves in a teaching of identities of a critical nature and attend to a multiple vision, claiming the need to work from different fields and in a dynamic way, consider it relevant (50%) to work explicitly on political issues. In relation to the topics and contents they select to work on identities in the classroom, there is a predominance of selection of disciplinary contents (58%) linked again to local issues, such as Andalusian culture and traditions, the Andalusian dialect or flamenco.

Previous studies have already shown that, for example, the teaching of history has traditionally been linked to the nationalist discourse through isolated and excluding disciplinary contents (Serrano & Facal, 2012; Pagès & Sant, 2015; Grever & van der Vlies, 2017). Therefore, bringing into classroom practice a critical and political teaching of identities also requires rethinking the purposes of teaching Social Sciences (history, geography, politics, among other disciplines) (Pagès, 2015). Doing so requires not only increasing epistemological reflection in teachers in training on the purposes, i.e., what is political education and why should it be taught in connection with identities, but doing so in close relation to the topics and contents that are selected. In this sense, it is noteworthy that the teachers in this study select RSP as contents to work on identities with their students to a high degree (42%). However, these results in relation to the type of activities they detail later denote that RSP are taught more as closed issues or projects linked to the discipline, rather than as social problems to be investigated, about which girls and boys have previous ideas and experiences and, above all, on which it is necessary to position and act in the social context. Therefore, although RSP are selected, they continue to be worked on in a predefined way and with little room for practicing citizen participation.

Considering the above, it would be necessary to deepen the political and democratic education of teachers in training, to make their conceptions of their own identity more complex and to make them understand that in advanced democratic societies, citizen identity, beyond culture, has an important critical and political component. In addition, their didactic training should be made more complex, leading them to positions that are less reproductive of content and more questioning of the problems of current reality.

Moreover, it is logical to think that when students enter the teaching profession, they will be strongly influenced by their own conceptions of identity and its teaching. This would lead to the perpetuation of these conceptions in the school system. In any case, it would be necessary to study the teaching practices surrounding this type of issues to go deeper into the question.

In sum, the results of this research make us reaffirm and think that, in the Spanish context, it is necessary to work in depth on citizenship education and identities. However, as Pagès (2015, p. 21) pointed out "[...] the democratization of the school and democratic political education were, and continue to be, minority phenomena". Faced with the rise of populist discourses, it is urgent that we put the focus on deconstructing our own identities and reconstructing them critically to favor coexistence between cultures and peoples. This does not mean that we should forget our signs of identity, since for any community this means security and legacy. But we also must decide how to construct new narratives and ways of linking ourselves, which, without making us lose our particularities, allow us to share, understand, respect and value other realities.

REFERENCES

Apple, M. W., Biesta, G., Bright, D., Giroux, H. A., Heffernan, A., McLaren, P., … Yeatman, A. (2022). Reflections on contemporary challenges and possibilities for democracy and education. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 54(3), 245-262. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2022.2052029 [ Links ]

Banks, J. A. (2017). Failed citizenship and transformative civic education. Educational Researcher, 46(7), 366-377. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X17726741 [ Links ]

Biesta, G. (2016). Democracia, ciudadanía y educación: de la socialización a la subjetivación. Foro de Educación, 14(20), 21-34. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14516/fde.2016.014.020.003 [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Sage. [ Links ]

Giménez, G. (2004). Culturas e identidades. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 66, 77-99. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/3541444 [ Links ]

Grever, M., & van der Vlies, T. (2017). Why national narratives are perpetuated: A literature review on new insights from history textbook research. London Review of Education, 15(2), 286-301. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.15.2.11 [ Links ]

Kahne, J., & Westheimer, J. (2014). Teaching democracy: what schools need to do. In E. W. Ross (Ed.), The social studies curriculum: purposes, problems, and possibilities (4th ed., p. 353-371). Albany, NY: Suny Press. [ Links ]

Kennedy, K. J. (2019). Civic and citizenship education in volatile times. Preparing students for citizenship in the 21st century. Hong Kong, CN: Springer. [ Links ]

Kriger, M. E., & Cid, H. F. (2017). Identidad ciudadana: los jóvenes y la construcción del espacio sociopolítico. Revista Latinoamericana de Investigación Crítica, IV(7), 119-136. [ Links ]

Morán, M. L., & Benedicto, J. (2016). Los jóvenes españoles entre la indignación y la desafección política: una interpretación desde las identidades ciudadanas. Última Década, 24(44), 11-38. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-22362016000100002 [ Links ]

Pagès, J. (2015). La educación política y la enseñanza de la actualidad en una sociedad democrática. Educaçâo em Foco, 19(3), 17-37. [ Links ]

Pagès, J., & Sant, E. (2015). L´escola i la nació. Barcelona, ES: Servei de Publicacions. [ Links ]

Ross, E. W. (2004). Negotiating the politics of citizenship education. PS: Political Science & Politics, 37(2), 249-251. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096504004172 [ Links ]

Sant, E. (2021). Educación política para una democracia radical. Revista Forum, 20, 138-157. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/frdcp.n20.84203 [ Links ]

Sant, E., & Brown, T. (2020). The fantasy of the populist disease and the educational cure. British Educational Research Journal, 47(2), 409-426. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3666 [ Links ]

Sant, E., Davies, I., & Santisteban, A. (2016). Citizenship and identity: the self-image of secondary school students in england and Catalonia. British Journal of Educational Studies, 64(2), 235-260. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2015.1070789 [ Links ]

Santisteban, A. (2021). Las contribuciones de Joan Pagès a la educación política: una obra imprescindible. Revista Forum , 20, 233-248. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/frdcp.n20.92094 [ Links ]

Santisteban, A., & Pagès, J. (2007). El marco teórico para el desarrollo conceptual de la Educación para la Ciudadanía. In A. Santisteban, & J. Pagès (Eds.), Educación para la ciudadanía. Guías para educación secundaria obligatoria (p. 1-14). Madrid, ES: Wolters Kluwer. [ Links ]

Serrano, J. S., & Facal, R. L. (2012). Aprender y argumentar España. La visión de la identidad española entre el alumnado al finalizar el bachillerato. Didáctica de Las Ciencias Experimentales y Sociales, (26), 95-120. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7203/dces.26.1933 [ Links ]

Cordes, A. & Sabzalian, L. (2020). The Urgent Need for Anticolonial Media Literacy. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 22(2), 182-201. [ Links ]

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (2002). Bases de la investigación cualitativa. Técnicas y procedimientos para desarrollar la teoría fundamentada. Medellín, CO: Universidad de Antioquía. [ Links ]

Tosello, J. (2018). Identidades y enseñanza de las ciencias sociales. Estudio de casos desde tres lugares del mundo. Revista de Investigación En Didáctica de Las Ciencias Sociales, (2), 88-103. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17398/2531-0968.02.88 [ Links ]

Valdés, J. J., Oller, M., & Labraña, C. M. (2016). Desarrollo de identidades ciudadanas: representaciones sociales sobre la participación en democracia tras las movilizaciones estudiantiles en Chile. In C. R. G. Ruiz, A. A. Doreste, & B. A. Mediero (Coords.), Deconstruir la alteridad desde la didáctica de las ciencias sociales: educar para una ciudadanía global (p. 246-254). Las Palmas, ES: AUPDCS. [ Links ]

Westheimer, J. (2019). Civic education and the rise of populist nationalism. Peabody Journal of Education, 94(1), 4-16. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2019.1553581 [ Links ]

8NOTE: Noelia Pérez-Rodríguez: Conceptualization, methodology, instrument validation, data collection, data analysis, writing original draft, reviewing, and editing. Nicolás de-Alba-Fernández: Conceptualization, methodology, instrument validation, data collection, data analysis, writing the original draft, reviewing, and editing, supervision, project management. Elisa Navarro-Medina: Conceptualization, methodology, instrument validation, data collection, data analysis, writing the original draft, review and editing, supervision, project administration. All authors have read and accepted the final version of the manuscript.

Received: April 30, 2023; Accepted: September 08, 2023

texto en

texto en