Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação & Formação

versión On-line ISSN 2448-3583

Educ. Form. vol.8 Fortaleza 2023 Epub 02-Ene-2024

https://doi.org/10.25053/redufor.v8.e10415

ARTICLE

Knowledge of literacy teachers: principles and domains for teacher self-assessment

iFederal University of Santa Maria, Santa Maria, RS, Brazil. E-mail: apowaczuk@gmail.com

iiFederal University of Santa Maria, Santa Maria, RS, Brazil. E-mail: paula.colvero@acad.ufsm.br

The article approaches the relationship between teaching knowledge and self-assessment processes in a shared way. We started with a qualitative study, developed from narrative interviews and dialogic encounters (Bakhtin, 2010; Bolzan, 2019; Freitas, 2009; Vigotsky, 2021) which will allowed us to identify the reference pedagogical practices of teachers working in the literacy cycle, as well as how to recognize the principles and the pedagogical domains prioritized by the teachers to energize their work. We consider that the knowledge derived from teaching experience makes it possible to build an effective repertoire of solutions acquired during a long period of work (Gauthier et al., 2006; Tardif, 2007), characterizing the teachers' reference practices, in which pedagogical principles and areas of scope can be evidenced. These dimensions will be discussed and shared, revealing driving forces for teacher self-assessment (Fernandes, 2008, Morales, 2014) encouraging reflection on ongoing pedagogical practices, and favoring teacher transformation and reworking.

Keywords: literacy; reference pedagogical practices; teacher self-assessment; teaching knowledge

O artigo aborda a relação entre os saberes docentes e os processos de autoavaliação de forma compartilhada. Parte-se do estudo qualitativo, desenvolvido a partir de entrevistas narrativas e encontros dialógicos (Bakhtin, 2010; Bolzan, 2019; Freitas, 2009; Vigotsky, 2021), os quais permitiram identificar as práticas pedagógicas de referência de professoras atuantes no ciclo de alfabetização, bem como reconhecer os princípios e os domínios pedagógicos priorizados pelas professoras ao dinamizarem seu trabalho. Considera-se que os saberes advindos da experiência docente possibilitam a construção de um repertório eficaz de soluções adquiridas durante uma longa prática do ofício (Gauthier et al., 2006; Tardif, 2007), caracterizando práticas de referências das docentes, nas quais se podem evidenciar princípios pedagógicos e domínios de abrangência. Tais dimensões, ao serem discutidas e compartilhadas, revelam-se impulsionadoras da autoavaliação docente (Fernandes, 2008; Morales, 2014), fomentando a reflexão das práticas pedagógicas em curso, favorecendo a transformação e a reelaboração docente.

Palavras-chave: alfabetização; práticas pedagógicas de referência; autoavaliação docente; saberes docentes

El artículo discute la relación entre los saberes docentes y los procesos de autoevaluación de forma compartida. Se parte de un estudio cualitativo, desarrollado a partir de entrevistas narrativas y encuentros dialógicos (Bakhtin, 2010; Bolzan, 2019; Freitas, 2009; Vigotsky, 2021), que permitieron identificar las prácticas pedagógicas de referencia de docentes que actúan en el ciclo de alfabetización, así como la forma de reconocer los principios y dominios pedagógicos priorizados por los docentes cuando agilizan su trabajo. Se considera que los saberes provenientes de la experiencia docente posibilitan la construcción de un repertorio efectivo de soluciones adquiridas durante una larga práctica del oficio (Gauthier et al., 2006; Tardif, 2007), caracterizando las prácticas de referencia de los docentes, de las cuales se pueden evidenciar principios pedagógicos y dominios de cobertura. Tales dimensiones, cuando discutidas y compartidas, resultan estar impulsando la autoevaluación de los docentes (Fernandes, 2008, Morales, 2014), favoreciendo la reflexión sobre las prácticas pedagógicas en curso, favoreciendo la transformación y la reelaboración docente.

Palabras clave: alfabetización; prácticas pedagógicas de referencia; autoevaluación del docente; saberes docentes

1 Introduction

The scenario seen at schools concerning the children’s right to literacy, especially concerning the pandemic period1, requires thinking about policies in different spheres, able to qualify and intensify pedagogical practices aimed at achieving literacy as a right for all.

There is a set of guidelines on what needs to be developed with children with a view to the literacy process, as we can see in the National Common Curriculum Base (Brazil, 2018), which establishes knowledge, skills, and abilities that need to be developed by students over the first three years of elementary school. However, the way teachers develop pedagogical practices lacks more systematic processes of analysis and problematization, since the dynamics of teacher self-assessment of practices rest on individualized and spontaneously directed processes.

We believe that more attention needs to be paid to the ways that the building and validation of the teacher practices are established, especially concerning the knowledge and actions that build the teachers’ everyday pedagogical practices (Bonat, 2020; Capicotto, 2017; Faria, 2018; Lopes, 2019, Machado, 2017; Pereira, 2022; Teodoro, 2019).

The establishment of processes that encourage self-assessment is essential for the advancement of issues involving the qualification of teaching practices in the literacy process and, consequently, teacher training, since talking about work and reflection on one's own action is to highlight the need to practice certain specific skills and to reflect on one's own action in order to strengthen teaching talent (Gauthier et al., 2006).

From this perspective, teacher self-assessment is an important teacher training device, as it encourages systematic processes of reflection on teachers' daily pedagogical practices (Bastos, 2021; Faria, 2018; Yot-Domín; Marcelo, 2022). This condition is fundamental for driving transformations in the way teachers do things, especially when it takes place in a shared way with colleagues in the same area.

This perspective mobilized the study, which aimed to collaboratively build dimensions for teacher self-assessment of literacy teaching practices. To this end, we sought to identify the reference pedagogical practices of literacy teachers who had been working for more than ten years in the literacy cycle of the municipal public education network of Santa Maria, Rio Grande do Sul (RS), as well as to recognize the principles and domains that guide their teaching practices.

The assumptions for this study are that teaching is built through experimentation, construction, and deconstruction, which leads us to recognize the experiential knowledge of the teachers taking part in the study (Gauthier et al., 2006, Tardif, 2007), as “[...] an experience of identity that does not belong to theoretical or practical knowledge, but to experience and thus mixes personal and professional aspects” (Tardif, 2007, p. 52).

The knowledge that emerges from teaching experience makes it possible to build up an effective repertoire of solutions acquired over a long period of practice, which in this study we refer to as reference practices. This construction encompasses a set of actions and perspectives, which we call pedagogical principles and domains of scope. By domains, we mean the areas and dimensions of knowledge that teachers address and develop in their teaching practice. The domains may vary depending on the educational institution but generally include areas prioritized in the planning and organization of lessons. Regarding the principles, we consider the dimensions prioritized in the organizational dynamics of the lesson (CPEIP, 2008).

It is important to consider that reference practices, considering their principles and domains, have a dimension of reproduction, which, in a way, transforms the teacher into a professional who is more secure in their knowledge and actions. This experiential knowledge, however, is often restricted to the teacher, a private knowledge in the classroom. Tested by the teacher, it often becomes somewhat limited, as it is based on assumptions and judgments that are not verified by scientific methods. This process, according to Gauthier et al. (2006, p. 187), has the effect of weakening teachers' professional development:

We are still in the situation in which each teacher, trapped in their own universe, creates for themselves a kind of private jurisprudence, consisting of rules built up over the years to the taste of mistakes and successes. This constitution is quite normal and desirable [...]. However, precisely because it is private, this jurisprudence only rarely makes it into the public domain to pass the validation test [...] a private jurisprudence of little use for teacher training and professionalization.

In this perspective, we based our study on the possibility of recognizing and sharing teaching knowledge as a way of valuing teachers both in their initial and continuing training and their practices. We agree with Bolzan and Powaczuk (2017) when they emphasize that many teachers feel lonely, most of the time, in the face of the difficulties encountered in teaching. Therefore, the absence of spaces for sharing makes it difficult for pedagogical protagonism to be established to its full potential.

Thus, we consider it relevant and powerful to build a tool capable of boosting the analysis and self-assessment of teaching practice, based on the recognition, analysis, and shared discussion of the domains and principles that guide the teachers' reference practices. We believe that when these dimensions are discussed and shared, they prove to be a driving force behind teacher self-assessment (Fernandes, 2008; Morales, 2014), encouraging reflection on current teaching practices and favoring teacher transformation and re-elaboration.

Morales (2014) highlights in her studies the importance of assessment to enrich teacher practices, a process that needs to be thought about and produced by teachers, requiring a path of dialog, reflection on action, and transcendence of daily life, through learning based on shared teaching and the defense of teachers' heritage of knowledge and experience.

In this sense, in this paper we present an excerpt from the study conducted, highlighting the domains and pedagogical principles evidenced in the reference practices of literacy teachers, arguing about the importance of collaborative reflection among peers for teacher self-assessment.

2 Methodological approach

he study was developed using a qualitative narrative approach of a socio-cultural nature, based on analysis of the collective construction processes of the subjects. It is therefore essential to pay attention to the sociocultural conditions/mediations from which the subjects elaborate and construct their ideas and actions. We assume that nothing can be understood in isolation, decontextualized, and that it is, therefore, necessary to consider the web of meanings and senses constructed in a given universe, within a given cultural situation, situated in a certain time and space (Bakthin, 2010; Bolzan, 2022; Freitas, 2009; Vygotsky, 2021).

The subjects of the investigation were four experienced teachers2 who had been working for more than 10 years in the literacy cycle, in other words, in the first three years of elementary school, in the municipality of Santa Maria/RS, located in the central region of Rio Grande do Sul/Brazil.

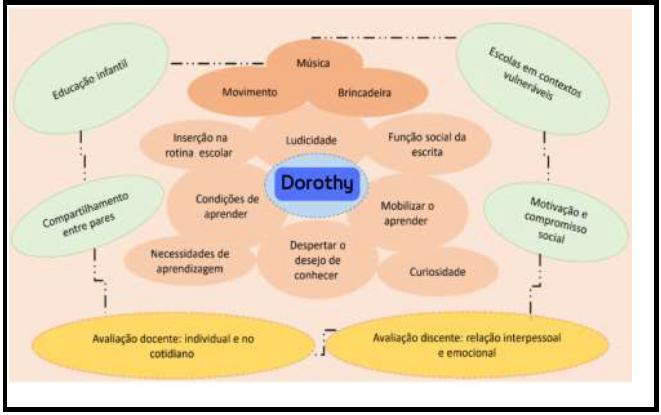

The research tools were individual narrative interviews and dialogical meetings based on the dimensions of Listening, Contextualization, Experimentation, and Re-elaboration (LCER) (Powaczuk et al., 2021). The aim of the narrative interviews was to identify the reference pedagogical practices of the literacy teachers, seeking to recognize the domains and guiding principles of their pedagogical practices. Once the interviews were completed, we transcribed them verbatim and proceeded to a preliminary analysis of the narratives, based on which we drew up concept maps, seeking to understand teaching knowledge and its sources, the domains and principles that guide literacy practices, as well as aspects relating to assessment, as shown in Figure 1.

Source: Elaborated from the individual interviews which each teacher who participated in the study (2023).

Figure 1 Conceptual map

Next, we held five dialogical meetings aiming to collaboratively analyze and problematize the principles and domains that guide the teachers' reference practices.

The research focused on the collaborative narrative perspective as a source of understanding about the values and meanings of being a teacher, betting on shared reflection as a way of building possibilities for experiencing and re-elaborating teaching knowledge.

The dialogical meetings based on the collaborative approach involved the dimensions of LCER. Listening, as the foundation of dialog, considering that there can be no dialog without listening. In this sense, each teacher was mobilized to narrate their trajectories and knowledge and to think about their practice and their challenges as literacy teachers.

The dialogical meetings aimed to bring together the meanings elaborated by the teachers, respecting their individualities and contexts. These were moments of dialogue, sharing, and teacher elaboration, considering the possibilities of Contextualization, Experimentation, and Re-elaboration among the participants.

3 Teaching knowledge of literacy teachers: principles and domains for teacher self-assessment

The study allowed us to identify, from the narrative interviews conducted with the teachers taking part in the study, that the validation and reconstruction of teaching knowledge is triggered by the daily challenges teachers face. The experimentation that teachers carry out in their pedagogical practices reveals unique ways of thinking and doing literacy teaching.

In highlighting the choices and definitions they make in their daily lives, the teachers emphasize principles and domains of pedagogical work as constituent elements of the teachers' experiential knowledge of literacy. As for the principles, we observed the mobilization of student learning as a recurring element in the organization of the teachers' teaching practice. The following narrative highlights this principle:

In fact, one of our great aspirations is the commitment to the issue of motivation, so that children recognize school not only as a place to meet their friends. It's about motivation with learning and also recognizing school as an important space and recognizing learning itself as something important for their life (Dorothy - Individual interview).

As professoras manifestam a importância da investigação, do estímulo à curiosidade, a qual exige a capacidade de escuta por parte dos professores acerca das questões que os estudantes se colocam em seus cotidianos. Nesse sentido, reconhecemos como princípio agenciador das dinâmicas pedagógicas a geração de necessidades, a qual é manifestada pelas professoras a partir da diversidade de estratégias que se utilizam para que as necessidades sejam manifestadas e mobilizem os estudantes a novas elaborações sobre os objetos de conhecimento a que se dirigem.

Mobilizing student's learning, curiosity, and interests - that's the key point. They bring us their curiosities and we have to take advantage of these moments to bring them into our planning. I had to create bonds with them, all online in the past, and the first thing I asked was: 'What do I want to learn to write?'; 'I want to learn to read'. Then they'd say: 'I want to learn about the rainbow'. 'It's nice to work, but I want to learn to read and write’, that's what they said - and the parents' desire now online - and I also explained the levels, so I did it both in person and online (Tinker Bell - 1st individual interview).

From the perspective of mobilizing students to learn, playfulness is strongly indicated in the narratives of literacy teachers. The narratives converge on the idea that playfulness is a fundamental element in students' learning. In the teachers' words:

Retelling the facts of the story in a playful way. I always start with story time and practical activities, because they really like them. So, activities that involve other areas of knowledge, like a recipe, where we can use a book, work on a recipe, the preparation, the ingredients, the quantity, or how to make other recipe ideas different from the same recipe (Alice - Individual interview).

They recognize it as an important principle of their work, but they also express the challenge of this direction, given that it is necessary to consider the diversity of students' experiences. In this sense, we identified the recognition of the diversity of students' experiences as another recurring principle in the teachers' narratives. These perspectives are close to the premises of Ferreiro and Teberosky (1999), who postulate the need to understand that children are not passive beings who wait for ready answers; on the contrary, they are individuals who actively seek to understand what is around them, who learn through their own experiences of objects in the world and who construct their own categories of thought.

The teachers emphasize the need for a careful look at each student's process so that the work considers their realities and social contexts. From this perspective, the teachers emphasize diagnostic evaluations, which support the teachers' planning. In their narratives, they say:

It's actually a routine thing. We don't stop to do something specific: “Now I'm going to evaluate myself”, it's more a day-to-day thing, a routine thing. We end up doing activities; there are things that work and don't work. As for assessing students, it's something we do in a procedural way, on a day-to-day basis too, also using the survey; I also like to work with technology as a way of assessing my students (Buttercup - Individual interview).

The teachers express the great challenge of meeting the diversity of students' experiences and, in this sense, a recurring aspect in the teachers' narratives was the need to establish pedagogical routines to promote student learning, which include organizing class times, adhering to the timetable, using the notebook correctly (formalizing the notebook), organizing school materials and knowing that everyone occupies a space in the classroom and that it is important to respect each other's space. In this sense, the teachers advocate the following:

After the pandemic, then, this welcome is even stronger; calming them down so that they can concentrate and turn their attention back to the class activity. Knowing that the moment outside is over and now they're going to return their concentration to that important moment, working on the issue of step by step. I've always had the issue of routine as a way of organizing myself with the issue of the time that is going to be worked on so that they create this habit of the importance of organizing themselves, concentrating, organizing their space at the table and their material (Buttercup - Individual interview).

Another principle of pedagogical practice is the promotion of support for the student's family. Thus, the teachers say that it is necessary to guide parents on the paths that students take in their learning to become literate; that it is necessary to get to know the reality of these families and try to make them understand that it is important to monitor activities at home so that their children are successful in their constructions. The following narratives illustrate this principle well.

I schedule meetings, I'm usually quite annoying to a certain extent; I usually give them a five-minute grace period and that's it, not because I think it's something to demand, but sometimes it's good for them to be organized and to know that they have their commitments and that this is reflected in the classroom for the children, so that they learn to be punctual for arriving at school on time, punctual with their activities to hand in. At least we manage to do most of this and we gradually adapt it, according to the routine of each family and each child (Buttercup - Individual interview).

As far as the domains are concerned, the teachers refer to the social function of writing, reading, storytelling, and phonological awareness as preponderant dimensions of their teaching practices. When talking about what they consider to be necessary in their teaching practices, the teachers express the children's recognition of words, letters, and their sounds through systematic work, which we believe refers to the development of phonological awareness. The narratives show this dimension:

So, Camila is going to show up and then my intention, I don't know the class, I don't know if they're going to like music or playing games to work on sounds, work on composition, work with the backpack, work on rhythm and word composition. I know that there are three students named Miguel in the room, so I'll pull out the 'Miguels' that are on the initial floor; I'll try to find out what they like to play with the most and my intention is to something different to arrive in the backpack every day. The object that isn't there suddenly has writing on it, which is why writing is so important. Giving them clues about what's in their backpack and encouraging them to read. If they like music, put something that has music on it, so they can guess what song it is. If it's games, I'll organize it (Tinker Bell - Individual interview).

Maluf and Santos (2017, p. 108) help us reflect on this by stating that learning written and spoken language is an explicit process, which will result in the ability to consciously process the information that children have access to:

Speakers undoubtedly have at least implicit knowledge of the structure and constitution of the language they use. Now, in order to learn the alphabetic writing system that will allow them to read and write in the same language they speak, they need to reflect on it and become aware of its various aspects: phonological, lexical, syntactic, and morphological. It is this metalinguistic knowledge that they need in order to be able to extract (decode) and spell (encode) the sounds of speech.

The development of phonological awareness involves children understanding that the sounds associated with letters have a correspondence in the sound chain of words, which presupposes the development of phonemic awareness. The teachers show this redirection in their teaching practices and exemplify the social function of writing:

To awaken this desire and to show the functionality of writing and how liberating it is to be able to read, to be able to write. When they start to learn, they feel this and show it: 'What a good thing', but she can pick up the book and already knows what the name of the book is, and they are very happy (Dorothy - Individual interview).

The teachers, when referring to their teaching practices, highlight the recurrence of work with reading and storytelling as important dimensions for contextualizing the proposals. They demonstrate that they work on the content to be developed through story time. They create possibilities for creation, skills development, and interdisciplinarity, among other alternatives that arise from storytelling.

Then there are the stories, some of which are also related to Beleléu's mathematics and the numbers he wants on a train that hides things, and then they have to count. The bunny, which is a very cute story; the wolf who ends up having a nightmare about the little sheep from counting them so much and he doesn't fall asleep, but, in fact, it's not that he wasn't falling asleep, he was dreaming, and then they're here to eat the little sheep. And then he thinks he's got a tummy ache and calls his mother outside and, in fact, he doesn't have a tummy ache, he was really hungry; he didn't eat any sheep. And it also includes counting and numerals. I also used Ziraldo's Ten Friends, which is a very nice story that also works on the names and nicknames of the fingers (Dorothy - Individual interview).

In this sense, the teachers participating in the study reveal, through their choices and definitions, the “[...] understanding that the teacher is the subject of the pedagogical process, that is, it is the teacher who defines the guidelines on the organization of classroom practices” (Bolzan, 2010, p. 110), and cannot do without careful listening to the students’ needs and paths.

Increasing this process requires reflection and permanent re-creation of ongoing pedagogical practices, knowledge built up by the teacher's teachers, favoring their professional development. However, the teachers, when talking about the self-evaluation process, expressed the understanding that self-evaluation cannot be done alone and that, in order for it to be shared, there is a lack of time and space for it in schools. Gauthier et al. (2006, p. 33) have already said that teachers create a kind of private jurisprudence when they don't have the opportunity to share their practices with their colleagues, leaving them “[...] confined to the secrecy of the classroom”.

From this perspective, we consider collaborative processes to be fundamental for improving teaching practices. Reflection allows the weaving of ideas that are redesigned in a shared way, creating a network of interactions that is produced as teachers have the opportunity to confront their knowledge and actions, thus favoring the process of learning to be a teacher (Bolzan; Powaczuk, 2017).

4 Collaborative reflections and the teacher self-assessment process

The dialogical meetings were held to bring together the meanings elaborated by the teachers, respecting their individualities and contexts. Thus, mobilized by the shared experiences, the teachers were able to talk about their practices, challenges, and experiences as literacy teachers. The following narratives show the dialogic dimension that permeated the meetings.

I would like to thank all the guest teachers for their participation: Teacher Dorothy, Teacher Buttercup, Teacher Alice, and Teacher Tinker Bell. [...]. Today's proposal is to talk about the maps drawn up from the interviews. Do you recognize yourselves in the dimensions shown on the map? Our idea today is that we can talk about the strengths of your literacy practice and what points you think you need to improve in your teaching practice from now on in the next planning sessions? (Interviewer - 2nd Dialogic Meeting).

When you ask me if I see myself on this map, I can see myself fully [...]. This is due to the movement, the space, and the children I'm working with this year. Then there's the issue that I mentioned in our conversation, which is very present, and their need, which is the issue of playfulness, that they came back to school with a great need to play, and it seems that this was, like, dormant, forgotten, at the same time that they show this need (Dorothy - 2nd Dialogic Meeting).

We believe that the sharing of knowledge during the meetings, based on the conceptual maps, were important devices for shared reflection. As the teachers expressed their ideas, knowledge and practices, the relationships fostered identification between the teachers regarding the shared challenges. In this way, the dialogical meetings were characterized by the sharing of ideas, requiring each teacher to make an effort to contextualize. Contextualization implies welcoming what the other person says, demanding a responsive posture. According to Bakhtin (2010, p. 272):

All real and integral understanding is actively responsive and constitutes nothing more than the initial preparatory stage of a response. The speaker himself is oriented precisely toward such an actively responsive understanding. He does not expect passive understanding that, so to speak, only duplicates his or her own idea in someone else’s mind, but a response, an agreement, a participation, an objectification, an execution [...].

In this sense, the responsive position is observed in the different manifestations, when the teachers, listening to the other teachers, rework their understandings based on their reality and context. From this, they express their elaborations based on aspects that are in agreement, complementary, and even deviant. Thus, each teacher's statement is reinterpreted, extracting meanings according to their needs and contexts, showing that the experience of one teacher serves as a trigger for the experiential reflection of the other participants, favoring a rethinking of teaching practices:

This responsive position of the listener is formed throughout the process of listening and understanding from the very beginning, sometimes literally from the first word of the speaker. Every understanding of living speech, of a living utterance, is of an actively responsive nature (although the degree of this activism is quite different); every understanding is full of response, and in this or that form it necessarily generates it: the listener becomes a speaker. The passive comprehension of the meaning of the speech heard is only an abstract moment of the real and full actively responsive comprehension, which is actualized in the subsequent response in real voice (Bakhtin, 2010, p. 271).

We emphasize that the responsive position favors the dimension of Experimentation to emerge, by allowing the established dialog to find new perspectives, new paths. Powaczuk et al. (2021, p. 140) remind us that “[...] dialog is inherent to the production of experiences since the word of the other invites us to get to know other worlds, creating possibilities for broadening horizons based on the relationship between self and other, in socio-historical-cultural contexts”. This creates a “weaving of networks” (Bolzan, 2019). By sharing knowledge, teachers have the opportunity to reframe their thinking and practices. The teachers' narratives highlight the dimension of experimentation:

And what a treat! It's great to be able to see in Tinker Bell's room [...] what motivates me the most: this issue of commitment. Perfect. I'm not perfect; nobody's perfect; and I don't want the day I become perfect either [...]. When I was younger, I thought I was, but life slapped me around a bit and I saw how much I wasn't and how tiny I am. The smaller I see myself, the more I have to learn. But I don't have to learn late; I have to know that there's another side to being cool; I don't know everything. For me, that's essential, but it's also essential to listen to you and to know that there's sharing, and that's what drives us; that's what makes us go forward, despite the criticism, despite finding many things wrong (Dorothy - 2nd Dialogic Meeting).

The narratives show the dialogic relationship being woven, manifesting the similarities, digressions, encounters, and disagreements that permeate teaching. In this sense, we observe the experimentation of new argumentative routes for the themes under debate, which foster Re-elaboration. According to Powaczuk et al. (2021), this process emerges from the possibility of subjects reviewing and rethinking their experiences constructed in established reflective processes, resulting in the possibility of reconfiguring knowledge and actions about teaching, because:

[...] Every concrete utterance is a link in the chain of discursive communication in a given field. The very limits of the utterance are determined by the alternation of discourse. Statements are not different from each other, nor are they sufficient in themselves; they know each other and mutually reflect each other. [...] Each utterance is full of echoes and resonances of other utterances with which it is linked by the identity of the sphere of discursive communication. [...] It is impossible to define one's position without relating it to other positions. That's why every utterance is full of various responsive attitudes to other utterances in a given sphere of discursive communication [...] (Bakhtin, 2010, p. 296-297).

Therefore, we believe that the meetings organized provided the teachers with an analysis of their work and practices, encouraging teacher self-assessment. Re-elaboration is based on the possibilities for subjects to examine and reconsider their experiences in a careful way, favoring the transformation of knowledge already known into something new, making explicit the relationships between the knowledge constructed and personal and professional trajectories. The following narrative expresses the teachers' elaborations on routine, which they see as an important principle of their practices:

In my case, as I work with younger children, I consider routine to be important, to give them a certain emotional stability, and it's no wonder that during this pandemic we've seen so many people go crazy because of their routines. It's been so disrupted, and it's all mixed up with work, home, and how much anxiety this leaves and causes for people in general. So, in that sense, I see routine as a positive thing, very positive, but routine can't be rigid either, and it's very good when you create a certain routine, a class, and it's an adaptation, and I think that teacher should adapt to her class and her class should adapt to their teachers (Dorothy - 2nd Dialogic Meeting).

Collaborative reflection emerges as the element based on the shared construction of knowledge and actions. Thus, questioning and doubt are taken as sources of teacher reworking, considering that nothing is understood outside of a context, a set of meanings, a time, and a space, resulting in the collective identification of a set of principles and domains considered by the teachers to be the driving force behind teacher self-assessment.

Absolutely, this tool provides this self-assessment and there are times when we need to stop; the running is so intense, and school is so busy, that we need to stop. And I know that we stop; I stop, but with the instrument, you can see that this item was lacking. So, yes, this self-assessment is very valid, and you were very happy to have done it, and I could see our conversations there at all times (Tinker Bell - 5th Dialogic Meeting).

I agree with [...] Tinker Bell; I was also able to see all our exchanges, our reflections, the moments of presentation, where we can bring a little bit of the reality that we experience in each part of the instrument. And, in fact, having this organization of thought in an objective, organized way makes us reflect on things that, at least for me, went unnoticed in our practice. It's a moment to reflect on what we need to improve, if everything is OK, if we can continue, so it's a very valid instrument; it puts us at ease for when we feel the need to do it and self-evaluate (Buttercup - 5th Dialogic Meeting).

We emphasize that the work will be favored if teachers have the opportunity to analyze their practices collaboratively with their colleagues, because the process of shared reflection, based on pedagogical practice, favors the activation of teaching thinking.

We believe that this perspective encourages the characterization and recognition of teachers' knowledge and ways of doing things, based on investigative and collective processes in the profession, which are the value measure of the teaching profession committed to its public dimension of social responsibility.

5 Closing remarks

The study shows that the teachers have a wealth of experiential and practical knowledge which, when analyzed and recognized, favors learning to be a teacher, encouraging teacher protagonism. It is important to consider that the process of elaborating on the teachers’ experiences is a fundamental device for constructing and reconstructing teaching knowledge, making it necessary, above all, to have a reflective practice that promotes changes and transformations (Gauthier et al., 2006; Tardif, 2007).

It is in the daily life of the classroom in which knowledge is validated and reconstructed, challenging self-reflection on ongoing practice. Self-evaluation is, therefore, fundamental to enriching teaching practices. It's a process that requires reflection on action and transcending everyday life. Through self-assessment, teachers can identify their qualities and potential, as well as their shortcomings and training needs (Morales, 2014).

Therefore, self-assessment favors professional self-knowledge since it enables teachers to identify their strengths and pedagogical preferences and seek strategies to improve them, enabling them to grow continuously and improve professionally.

We believe that dialogic encounters, based on the dimensions of Listening, Contextualization, Experimentation, and Re-elaboration (LCER), are potential for collaborative work between teachers, enabling the activation of teacher thinking, encouraging the construction and reconstruction of teaching knowledge.

In this sense, the study contributes to discussions about knowledge and the management of educational literacy practices, strengthening the argument around the need for systematically organized spaces that enable teachers to discuss and share experiences and knowledge, fostering teacher self-assessment processes and consequently teacher training and professionalization.

REFERENCES

BAKHTIN, M. M. Estética da criação verbal. 5. ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2010. [ Links ]

BASTOS, A. P. F. Pades - Processo para Autoavaliação Docente no Ensino Superior sobre suas Aulas. 2021. Dissertação (Mestrado em Informática Aplicada) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Informática Aplicada, Universidade de Fortaleza, Fortaleza, 2021. [ Links ]

BOLZAN, D. P. V. Fundamentos da leitura e escrita. Santa Maria: Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, 2022. [ Links ]

BOLZAN, D. P. V. Pesquisa narrativa sociocultural: estudos sobre a formação docente. Curitiba: Appris, 2019. [ Links ]

BOLZAN, D. P. V.; POWACZUK, A. C. H. Processos formativos nas licenciaturas: desafios da e na docência. Roteiro, Joaçaba, v. 42, p. 107-132, 2017. DOI 10.18593/r.v42i1.11550. [ Links ]

BONAT, A. P. G. Professoras iniciantes nos anos iniciais: saberes e práticas como perspectiva articuladora para a sua constituição docente. 2020. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Pelotas, 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Brasília, DF: Ministério da Educação, 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Nota técnica: Impactos da pandemia na alfabetização de crianças. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2021. [ Links ]

CAPICOTTO, A. D. Os saberes do professor alfabetizador: entre o real e o necessário. 2017. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Rio Claro, 2017. [ Links ]

CPEIP. Marco para la Buena Enseñanza. Santiago, DC: Ministerio de Educación, 2008. [ Links ]

FARIA, P. S. P. Gestão escolar, acompanhamento pedagógico e práticas escolares: um estudo sobre a eficácia escolar em três escolas estaduais de Belo Horizonte. 2018. Dissertação Mestrado em Educação) -Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2018. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, D. Avaliação do desempenho docente: desafios, problemas e oportunidades. Lisboa: Texto Editores, 2008. [ Links ]

FERREIRO, E.; TEBEROSKY, A. Psicogênese da língua escrita. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 1999. [ Links ]

FREITAS, M. T. A. A pesquisa de abordagem histórico-cultural: um espaço educativo de constituição de sujeitos. Niterói: UERJ, 2009. [ Links ]

GAUTHIER, C. et al. Por uma teoria da pedagogia: pesquisas contemporâneas sobre o saber docente. 2. ed. Unijuí: Ijuí, 2006. [ Links ]

HUBERMAN, M. O ciclo de vida profissional dos professores. In: NÓVOA, A. (org.). Vidas de professores. 2. ed. Porto: Porto, 2013. p. 31-61. [ Links ]

LOPES, K. C. P. As repercussões do Pacto Nacional pela Alfabetização na Idade Certa (PNAIC) na ótica de docentes. 2019. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2019. [ Links ]

MACHADO, K. C. S. Saberes construídos e mobilizados na prática pedagógica do professor nos anos iniciais do ensino fundamental. 2017. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal do Piauí, Teresina, 2017. [ Links ]

MALUF, M. R.; SANTOS, M. J. (org.). Ensinar a ler: das primeiras letras à leitura fluente. Curitiba: CRV, 2017. [ Links ]

MORALES, A. R. Como transitar de uma concepción distinta de evalución a la acción evaliativa?. Pearson Blue Skies: nuevas concepciones sobre el futuro de educación superior en Latinoamérica, [S.l.], 2014. Disponível em: http://latam.pearsonblueskies.com/2014/como-transitar-de-una-concepcion-distinta-de- evaluacion-a-la-accion-evaluativa/. Acesso em: 20 jan. 2023. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, D. P. O Programa Municipal de Letramento a Alfabetização (Promla) e sua Implicação na Gestão do Trabalho Pedagógico. 2022. Monografia (Especialização em Gestão Educacional) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Gestão Educacional, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Santa Maria, 2022. [ Links ]

POWACZUK, A. C. H. et al. As redes colaborativas como princípio da pesquisa e da formação. In: EIIPE, 9, 2021, Curitiba. Anais [...]. Curitiba: Universidad Nacional de Entre Ríos, 2021. [ Links ]

TARDIF, M. Saberes docentes e formação profissional. Tradução de Francisco Pereira. 8. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2007. [ Links ]

TEODORO, W. L. Construindo uma escola eficaz: boas práticas em escolas localizadas em contexto de vulnerabilidade social do município de Águas de Lindóia - São Paulo. 2019. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas, Campinas, 2019. [ Links ]

VIGOTSKY, L. S. Psicologia, educação e desenvolvimento: escritos de L. S. Vigotsky. Organização e tradução de Zoia Prestes e Elizabeth Tunes. São Paulo: Expressão Popular, 2021. [ Links ]

YOT-DOMÍNGUEZ, C.; MARCELO, C. Estrategias de aprendizaje formal y no formal de docentes para su desarrollo profesional: diseño y validación de un instrumento. Archivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas, Sevilla, 2022. [ Links ]

1This was already a necessary condition before the Covid-19 pandemic. However, given the impact of the pandemic context on student learning, this dimension has become more urgent, given the learning gaps generated by inequalities in access and conditions for our students in 2020/2021. According to the Technical Note: Impacts of the pandemic on children's literacy, in relative terms, the percentage of children aged 6 and 7 who, according to their guardians, could not read and write rose from 25.1% in 2019 to 40.8% in 2021. “This impact reinforced the difference between white children and black and brown children. The percentage of black and brown children aged 6 and 7 who could not read and write reached 47.4% and 44.5% in 2021, compared to 28.8% and 28.2% in 2019. Among white children, the percentage went from 20.3% to 35.1% in the same period” (Brazil, 2021, p. 2).

2This criterion is supported by Huberman's (2013) studies, which indicate that when teachers reach 8 to 10 years in their career, they reach a phase or stage of “definitive commitment”, “stabilization” and “taking responsibility”. This means that the subject becomes definitively committed to their teaching profession. Huberman (2013) also points out that stabilization carries a meaning of belonging to a professional body and independence (liberation, emancipation). In selecting the teachers, we also considered the 2019 Basic Education Development Index (IDEB) indicators for municipal schools, teachers who work in schools with the highest IDEB numbers in 2019, and schools with the lowest IDEB, with situations of accentuated social vulnerability.

Received: April 29, 2023; Accepted: August 25, 2023; Published: October 01, 2023

texto en

texto en