Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação & Formação

versión On-line ISSN 2448-3583

Educ. Form. vol.8 Fortaleza 2023 Epub 02-Ene-2024

https://doi.org/10.25053/redufor.v8.e11262

ARTICLE

A sui generis educational process: the pedagogy for love in a Brazilianized idyll1

iFederal University of Jataí, Jataí, GO, Brazil. E-mail: bh.santana@yahoo.com.br

This paper seeks to understand the meaning and the nature of the label “idyll”, purposefully employed by Mário de Andrade in the novel To love, intransitive verb, as an important element for reading the work, emphasizing the representations of female teachers who worked in the homes of some wealthy families in São Paulo in the early twentieth century. The pedagogy of love as a contingency of a type of social need contrasts with the classical sense of idyll, for in this work it denotes a peculiar purity that is relentless for a demanded love education that aimed at patrimonial protection. In this research we used the methodology pertinent to the notion of historiographical operation, through which we were able to verify that the literary text, through verisimilitude, also has the ability to shed light on the educational past.

Keywords: To love, intransitive verb; homeschooling; history of education; idyll

O presente artigo busca compreender o sentido e a natureza do rótulo “idílio”, empregado propositalmente por Mário de Andrade no romance Amar, verbo intransitivo, como importante elemento para a leitura da obra, enfatizando as representações de professoras que atuavam nas casas de algumas famílias ricas paulistanas no início do século XX. A pedagogia do amor como contingência de um tipo de necessidade social contrasta com o sentido clássico de idílio, pois nessa obra denota peculiar pureza, que é implacável para uma demandada educação amorosa que visava à proteção patrimonial. Utilizou-se, para a elaboração desta pesquisa, a metodologia pertinente à noção de operação historiográfica, por meio da qual se pôde verificar que o texto literário, através da verossimilhança, também possui aptidão para iluminar o passado educativo.

Palavras-chave: Amar, verbo intransitivo; ensino doméstico; história da educação; idílio

Este artículo busca comprender el significado y la naturaleza de la etiqueta “idilio”, empleada a propósito por Mário de Andrade en la novela Amar, verbo intransitivo, como elemento importante para la lectura de la obra, haciendo hincapié en las representaciones de las maestras que trabajaban en las casas de algunas familias adineradas de São Paulo a principios del siglo XX. La pedagogía del amor como contingencia de un tipo de necesidad social contrasta con el sentido clásico del idilio, pues en esta obra denota una peculiar pureza implacable para una exigida educación amorosa que apuntaba a la protección patrimonial. Se utilizó, para la elaboración de esta investigación, la metodología pertinente a la noción de operación historiográfica, mediante la cual se pudo comprobar que el texto literario, a través de la verosimilitud, también tiene la aptitud de iluminar el pasado educativo.

Palabras clave: Amar, verbo intransitivo; enseñanza en casa; historia de la educación; idilio

1 Introduction

Mário de Andrade was a multifaceted Brazilian modernist intellectual and, although he lived in the capital of São Paulo, he sought to get to know and understand Brazil up close, through trips to various locations, as he noticed not only the linguistic variations of the speakers, but also the strong presence of miscegenation and diverse cultural expressions.

He was the main organizer of the Modern Art Week in São Paulo, who spared no effort to bring aesthetic ideas inspired by the European avant-garde, especially Futurism, to Brazil. In literature, he sought to implement a type of writing that provided reading speed with little punctuation, that didn't worry so much about metrics, to show a rupture with traditional schools, such as Parnassianism, still attached to forms, and with authors who behaved very impassively towards their objects, such as Olavo Bilac and Coelho Neto.

Mário de Andrade, who died prematurely in 1945 from heart complications, was the poet of the new, although in literature it is not appropriate to speak of evolution but of expansion, as if we were facing new stars in the firmament (Frye, [1963]/2017). However, the writer focused on new problems and approaches more geared towards social reality, as can be seen in To love (1927), Macunaíma (1928) and Contos novos (1947, posthumous). In this, the author highlighted social dilemmas and challenges, so that, specifically in the novel To love, intransitive verb - hereafter referred to simply as To Love for greater fluidity in reading - Mário de Andrade addressed the issue of foreigners circulating in Brazil in the First Republic [or Old Republic] (1889-1930) who, in addition to farming, also worked for the new wealthy industrialists on the rise in the capital of São Paulo, considering the state of crisis and discontent with the policy focused on the production and export of coffee.

The writer's perspective in the novel To Love was the domestic environment of a wealthy family from São Paulo who demanded the pedagogical services of a foreign teacher in a kind of teaching that was idealized in form but subverted in content, because, on the surface, Fräulein was a German and piano teacher, but in practice she was fulfilling an obligation arising from a verbal contract signed with the patriarch Mr. Felisberto Sousa Costa, which provided for the sexual and amorous initiation of his teenage son Carlos. This service was seen as necessary for the boy to know how to deal with women and for love to be taught as something practical, without madness, attachment, and jealousy, in a logic that would give the student the expertise to deal with possible adventurous women, protecting the tangible assets and intangible heritage of the family surname.

It's important to note that To love has a subtitle that Mário de Andrade calls "idyll". This characteristic perplexes the reader of the novel, since the idyllic idea in the traditional form is one of pure love, of sincere feelings connected to nature, whereas in To Love we find a love themed contrary to these characteristics, since it is nothing more than a contingency of the needs of a bourgeois family, dissociated from affection and mutual cooperation.

Thus, in this article, we invite you to reflect on the nature of this idyll employed by the writer and what it can reveal to us, based on the representations of the teachers who worked in these houses to provide services that were not necessarily sentimental, but marked by the logic and contingency of the education of politeness due to the esteem of European appearances.

The methodology used here is critical source analysis, based on the historiographical operation advocated by Michel de Certeau ([1975]/2020), which places the historian in the role of mediator. To this end, the text has been organized into three topics, starting with brief considerations about domestic education and how this practice appears in To love; we then move on to analyse the meaning of idyll in the Marioandradian sense, which according to the modernist himself, is also pure, but in his concept, what is striking is fatality. Finally, we analyze the relationship between preceptorship and/for love, considering that the pedagogy invoked takes into account the story of love, which according to Sant'anna (1992), is confused with the story of the fear of loving.

2 A brief look at domestic education based on To love, by Mário

Literature, as art, seems to be even more prodigious in portraying the educational act in a private environment. In Brazil, this literary perspective regarding preceptorship or domestic teaching stands out, under the aegis of Modernism2, Mário de Andrade's novel To love, an intranzitive verb3 (1927), which deals with the passage of a German woman, Fräulein [Miss] Elza, through the home of a wealthy São Paulo family, stands out under the aegis of modernism. An exquisite teacher with the skills to teach piano and German to the four children of the Sousa Costa family: Carlos, and his sisters Maria Luísa, Laurita and Aldinha, aged fifteen, twelve, seven and five respectively.

But Mário de Andrade inserts an ingredient that puts the job of teaching this knowledge as a façade, since the task was to give sexual lessons to Carlos, the first-born and “inexperienced” fifteen-year-old boy (Andrade, 1995, p. 70 and 92). There are contrasting cultural, moral, economic and legal elements here; apparent circumvention of the criminal law in place; not to mention male domination, racism and the association of the figure of the teacher with unusual images for the time. The novel involves the centrality of subverted education aimed at the male gender (Carlos), although the character's sisters also received apparent lessons from the preceptor, involving sophisticated knowledge.

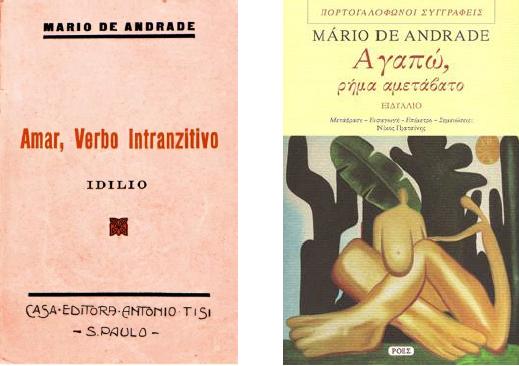

Source: Personal archive of the researcher.

Figure 1 Cover of To Love (1927) and its Greek translation (2017)

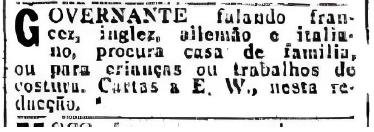

In addition to literature, the passage of foreign preceptors through Brazil from the 19th century to the mid-20th century is demonstrated by other sources. Several advertisements for such services in newspapers from the period in question required the candidate to have reliable conduct and an unblemished reputation for teaching. Notwithstanding the press source, there are records, in letters, of foreign preceptors passing through Brazil, such as Ina von Binzer (1856-1916) or simply Fräulein Binzer, a German woman born in 1856, who arrived in Rio de Janeiro at the age of 22 to teach the children of wealthy farmers from the countryside of São Paulo and the province of São Sebastião (now Rio de Janeiro). After three years in Brazil, Ina wrote forty letters to her friend Grete, from Germany (from May 27, 1881 to January 9, 1883), detailing aspects of daily life within the host family, as well as the educational act, its difficulties and impressions (Binzer, [1956]/2017).

Transcript: “GOVERNESS: speaking French, English, German and Italian, looking for a family home, or for children or sewing work. Letters to E. W., in this editorial office [sic]”.

Source: Estado de S. Paulo (8 May 1914, p. 13).

Figure 2 Foreign teacher advertisement

The historical records and literary discourses surrounding the same fact have a lot to say about these women, since, as Ginzburg ([2007]/2017, p. 14) infers, historians “(and, in another way, poets too) have as their job something that is part of everyone's life: to unravel the interweaving of true, false and fictitious that is the fabric of our being in the world”.

2.1 Brazilianized pedagogical idyll as fatalistic purity

Mário de Andrade lived through the effervescence of the belle époque in Frenchized Brazil. However, he never left Brazil and, of the great exponents of the foundation of Brazilian Modernism, he was the only one who didn't go to São Francisco to study law or any other higher education course (Miceli, 2016). And the self-taught nature of the author of Macunaíma didn't dampen his enthusiasm for better understanding Brazil, while he was also attuned to what was happening in Europe. For example, Mário was a careful subscriber and reader of the magazine L'Esprit Nouveau4 (Feres, 1969; Grembecki, 1969), which made him aware of the European avant-garde and brought to the Brazilian modernist new matrices of aesthetic ideas in circulation on the Old Continent.

Carvalho (2008) dedicated a meticulous study to showing that Mário de Andrade accessed every issue of the magazine, which he not only made a point of acquiring, but also dedicated in-depth analysis to, according to the various notes in the margins of the periodical, and that many ideas expressed there were incorporated here, including in the Prefácio interessantíssimo, from 1922; in To love, from 1927 and [1944]/1995; Macunaíma, from [1928]/1977; and in the collection Contos novos, from 1947.

It should be made clear that from the perspective of “form”, Mário de Andrade took care to clarify that To Love is a work similar to another French novel published in the 18th century, since the Brazilian modernist was a reader of Bernardin de Saint-Pierre (1737-1814), who had written a work of similar content, with a strong expressionist imprint. In fact, Mário didn't hide this background, confirming the origin of the inspiration in the novel itself, but this time in a Brazilianized language: “Ahn... I was about to warn you that this idyll5 is imitated from the French of Bernardin de Saint-Pierre [...]” (Andrade, 1995, p. 91). However, this doesn't mean that the Brazilian modernist's novel wasn't an original production, so he wasn't lacking in intellectual honesty, not least because it wasn't plagiarism, but an allusion to a transformative mechanism.

Inspirations such as the one pointed out by the author, that To Love would be an imitation of the French work Paul et Virginie, were duly clarified in a publication in the Diário Nacional of April 9, 1929, verbis:

We can't conceive of the formation of a spirit without influences, the result of personal experience alone, because that goes against the very laws of psychology. As for originality, while historically it is of paramount importance in the evolution of the arts, it has no conceptual value in verifying the masterpiece. And thinking of the deluge of spirits that have arisen and disappeared, without giving what they promised to the modern Brazilian movement, I'm sure that for many it was the empty vanity of originality that disarmed them. They were silenced by a deficiency that was false (Andrade, 2005, p. 63).

These lines demonstrate that Mário de Andrade's idyll is not the same as Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s but was forged in the aesthetic spirit of the modernist, from the intense influence of that French author. However, it is still an idyll. In fact, the Brazilian writer only rescued the notion of the classic idyll, as that which concerns a country romance, whose plot involves love in the form of tenderness, complicity, harmony with nature and reciprocated affection, to characterize, in the light of his modernist project, a love that is an object, which is at the service of a specific purpose, namely: to demonstrate his criticism of some of the new Brazilian rich on the rise during the First Republic.

This part of the elite preferred the civilizing brilliance of the German teacher to teach their “male” children to love without getting involved. It's an intransitive action, since, unlike the classic sense of idyll, love is nothing more than a casual, uncompromising and apathetic enjoyment of the other person in the relationship. In addition, with regards to the Brazilian idyll To love, it should be noted that the author himself justified what he meant by this label in his handwritten6 note in pencil, on a loose sheet of paper, located inside the notebook he called “Wind”, which belongs to Mário's collection, held by the Institute of Brazilian Studies (IEB), linked to the University of São Paulo:

- Wind - Explain why I call this book ‘idyllic’, as well as ‘To love, intranzitive verb’ and the forthcoming Tempo da Maria. Idyll no longer has pastoral objectivity. For me, an idyll is a passage of love, full of sweetness and, above all, full of purity. Just as Fräulein and Carlos Sousa Costa's idyll To love, intranzitive verb is pure. Not the traditional purity of the Christian concept of sin, of course. It's pure because it has that purity of fatality. It had to happen and it didn't have cons (sic) wickedness, no conscious impurity to speak of. It's sincere, it's fatal, it's pure. Even easier to prove is the idyllic purity of this book (Andrade, 1925?a, n.p., crossed out by the author).

Returning to the inspiration for his writing, Mário de Andrade didn't need to go to Europe to get closer to new aesthetic sources, because, according to him: “Je suis un ilumine économique. Je n’ai pas besoin de voyager”7 (Andrade, 1921, p. 1.218)8. The intellectual journey took place in his personal library, in Lopes Chaves Street, in São Paulo, according to the essay “Mário de Andrade's library: a hotbed of creation” by Lopez (2002), which discusses the author's creative process. In this respect, it should be added that To love, as the nominal form of the title, refers to the provocative action and strange verbal classification, not naively or out of ignorance of the grammatical rules of the vernacular. In this case, love is an intransitive practice.

As mentioned earlier, the modernist author alluded to the imitated and imitation, so there seems to be a line that stands out in relation to the very idea of what love is, because in Paul et Virginie love is affection, sensitivity, charity, and the joy of meeting despite life's adversities. In the French novel, love is in fact transitive and supportive. In To love, on the other hand, it's not just sublime love, but sexual love, which needs to be taught. In other words, there are two types of love, the one that Mr. Sousa Costa understands to be (purpose), and the one that Professor Fräulein (pedagogical agent) teaches: practical sense and absence of madness.

These matters indicate that a hasty reading of the passage in which Mário de Andrade declared that he had almost forgotten to warn about the “imitated” condition of the French of Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, can lead the inattentive reader astray, either because of the grammatical mockery contained in the title or because of the expression idyll, which in To love evokes a sentimental narrative different from the traditional definition, re-signified according to the modernist bias.

So, just as the subtitle “idyll” was chosen, the title given to the novel by Mário de Andrade does not serve to defy grammar. On the contrary, it refers to the behavior that, in theory, should allude to reciprocity, but which is not reciprocal, so it is the behavior itself that infirms the verb and the respective classifications of predication. The link that unites the preceptor and the student does not denote naivety, nor does it denote ordinary action.

Regardless of whether it is classified as a verb, to love is a word and it is not grammatical in itself but reveals a meaning that is a reflection of who we are, of what society expresses, of the symbolic universe objectified, of what Mário de Andrade witnessed in his chronotope [time and space / chronos + tópos]. This brings us back to the philosopher of language Valentin Volóchinov (2019), who argues that the word does not exist as an object of nature or technology for subsequent transformation into a sign, that is, “in the word there is nothing that is indifferent to this purpose and that has not been generated by it” (Volóchinov, 2019, p. 312). Thus, by subsuming the Russian author's idea, the word to love, which is part of the novel's title, takes on the role of awakening the reader to reflection, based on a procedure that Volóchinov (2019, p. 317) does not consider to be a “gross grammatical error, but a stylistic value of the word”9.

But the strangeness of the intransitive verb is not just due to the teacher's pedagogical relationship with the student. The futuristic avant-garde allowed this kind of lengthening of the verb in To love's lines, all in order to encompass new proposals, including the social issue of the drama experienced by the foreigners who arrived in Brazil. The butler and gardener Tanaka (one of the immigrant characters) and the shy housekeeper Elza have come to live in a strange family circle. They are anonymous people who also fit into Mário de Andrade's social research, and here they were used to shed light on those who could not speak for themselves about their dramas.

It's important to note that the actions are intransitive in other domains; we only need to see that in the novel, when the preceptor finally manages to take the student to the practical love lesson, the reader is left out of the room, when the author, instead of reporting details of the bed, puts it in the background, so that the climactic scene is suspended and gives way to the theme of immigrants, not to deal with the advances of industrial modernity that they have contributed, but to highlight the problems surrounding language, art and, above all, the humanity of the Elzas, Tanakas, governesses, teachers, prostitutes, gardeners and butlers who are tolerated and not included.

2.2 Preceptorship and love as a transposition for To love, by Mário

When it comes to philosophical inspirations for the theme of preceptorship discussed above, it is important to think of it as an activity, as a “means to an end” human action: teaching. In the case of Mário de Andrade's To love, as examined here, it is about secretly established teaching, described in a modernist novel, as a genre characteristic of the crisis of the modern subject (Rosenfeld, 1973).

To love grew out of a restless mind and this has to do with the influences of a writer who was eager to get to know the world through research and, through this, produce a provocative and audacious aesthetic. This concern is also linked to lived or witnessed experiences, resulting in his artistic creation as a whole. In another work called The banquet, also by Mário de Andrade, dialogues take place over a luxurious dinner, themed around music, his greatest affinity. It was published posthumously in 1977 and contains a passage in which Mário explains the articulations related to the inspiration for his writing:

- I say that ‘free creation’ is a chimera because no one is made of nothing, nor of themselves alone; and creation is neither an invention from nothing, but a fabric of memorized elements, which the creator acts in a different way , and at most takes further. I'm insisting on an obvious point. Creation, with all its freedom of invention, which I don't deny, is nothing more than a reformulation of pieces of memory (Andrade, 1977, p. 150, emphasis added).

This agency that the Brazilian modernist highlights is reminiscent of Plato's work of the same name, which concerns a kind of debate on the theme of “love”. While Plato's banquet thematizes love, Mário de Andrade's banquet thematizes music, which does not seem to be a fortuitous choice, since this was his passion, therefore associated with love and predilection. What is love? Although classics claim that To love, intransitive verb is timeless, it is safe to say that love is a theme that runs through history. It is [and has been] the subject of poetry, the inspiration for songs, the cause of Christian redemption, so that some might ask: Hasn't everything already been written about love, declaimed in every language and in every era? Is there still room for originality in the face of such an exploited and perhaps trivialized theme?

These inquiries lead us to think that understanding our subject also involves reflecting on the important variable of love, since the representations being analyzed are interconnected with the pedagogical act of this element. In this respect, it is worth considering that Sant'Anna (1992, p. 85) explained that the theme of love is a privileged subject in literature, because writers, in a way, function as “dreamers of public utility”, since they publicly dream of a mechanism that invites the reader to do the same. And in this effort, thinking of Mário de Andrade's contribution from 1923 to 1944, he adds that “The history of love - not only in Brazilian literature, but in universal literature and, in general, in all cultures - is not only the history of love, but the history of the fear of loving” (Sant'anna, 1992, p. 86, emphasis added).

Indeed. The question still throbs and bifurcates into other questions: Is love something only imagined? Is it natural or socially constructed? “Is love something that can be taught?” (Andrade, 1995, p. 63) - echoes the doubt of To love's narrator. It's important to say that, for some, it has no tangible body:

Love has a place to hurt. And it's not in the heart. If love decided to penetrate the organ that supplies the body with blood, hearts in love wouldn't last half an hour. Love is madness, the Greeks knew that. For me, love hurts in the belly, just below the ribs. Pain that lasts for days, sometimes weeks (Schüler, 2013, p. 234).

Whether or not it causes physical pain, as reported by Donaldo Schüler, in Machado de Assis, for example, love is not idyllic, but a dangerous and intoxicating game, it is strong at the same time that it is also tyrannical, it arouses possession, jealousy and sometimes empties the pocket, according to Brás Cubas' experience with his beloved Marcela: “Marcela loved me for fifteen months and eleven réis; nothing less” (Assis, [1881]/2008, p. 74). In other words, when the economic gain that fed Marcela's vanity ceased, she stopped loving and, “without blushing”, soon afterwards moved to Europe in the company of another man. From this point of view, love in Machado can be pure and solemn, but at the same time it can be tainted by the question of interests, especially property, so that it is a mixture that complements each other, and the two are constituted within one being. A lame verb, which also means to barter or buy, and this would become a tormenting realization for a 19th century Brazilian reader.

Thus, regardless of whether love is more than an arm, an eye, skin, or an object available on market shelves, the novel To love discusses love, social relations, wrongdoing and disenchantment in the capital of São Paulo at the beginning of the 20th century. The representations of teachers are based on the dynamics surrounding the pedagogy of love. And speaking of this theme, there was no shortage of references in the modernist novel to Plato, to that Greek banquet:

To so much science and so little anatomy, I prefer the idea told by Father Pernetty: ‘Les femmes ont plus de pituite et les hommes plus de bile... Certains philosophes ne craindraient pas d’afirmer que les femmes ne sont femmes que par un défaut de chaleur’10. And if you want something even more gratifying, just remember the discreet fable told by Plato in the Banquet... But what matters are the statements of those very wise Germans, evoked here to validate my assertion and give it a scientific-experimental frown: THERE IS NO LONGER A SINGLE WHOLE PERSON IN THIS WORLD AND WE ARE NOTHING MORE THAN DISCOURSE AND COMPLICATION (Andrade, 1995, p. 80, emphasis added).

Mário de Andrade was a reader of philosophy, according to several letters sent to his peers (Amaral, 2001; Ionta, 2007). Thus, starting with Plato's The Banquet, Mário was aware of the various perspectives on love contained therein, originating from a dialog established at a party (hence the name banquet) between Aristophanes, Socrates, Alcebiades and Agathon, the latter the host, winner of the contest for poetry interpreter, with love being the theme of this conversation. What stands out in this dialog is Aristophanes' idea that love meant missing, longing, absence, filling a void that already exists in us (Plato, [380 BC?]/1996), which is similar to the romantic love of the bourgeois world.

In this vein, it's worth remembering that in William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet (1597), also read by Mário, love is very intense but short-lived, so four days wasn't enough time for the feeling to get “soiled” by pacts and social rules. In Hamlet (1602?), a work by the same author that also deals with the subject, the approach is different, since this time love passes through the filter of reflection and, when this happens (rationalizing), things aren't going very well, love is no longer spontaneous. Now, love is affection, but from this perspective, it wears out over time. It's a powerful affection that can be beneficial to the subject's humanity, but when it gets stained by legal rules, especially with the notion of marriage, it moves away from the meaning given by Aristophanes: tenderness and filling the void.

In Mário de Andrade's novel To love, we find this complexity related to the love of rules and, above all, that of appearance, which must be taught by an expert teacher, without the madness of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet ([1597]/2011); without the deep and indispensable connection of Gasset ([1914]/2019); without the hidden and contradictory ardor of Camões (1843), but sifted by reflection motivated by utility or contingency. The Sousa Costa family has assimilated that love, as defined below by Carlos Drummond de Andrade, is not what a child should experience, and there is nothing better than an experienced teacher to teach such a lesson in line with the social pacts she believes in.

TO LOVE

What can one creature among other creatures

Do but love?

Love and forget,

Love and mislove,

Love, unlove, love?

Always, and with wide eyes, love?

What, I ask, can a loving soul

Alone in the universal rotation do

But spin with everything else, and love?

Love what the wave brings to shore,

What it buries, and what in the ocean breeze

Is salt, or the need for love, or mere longing?

Love solemnly the desert palms,

The act of surrender, or expectant adoration…

And love what’s rough or barren,

A flowerless vase, an iron land,

The unfeeling breast, the street from a dream, a bird of prey…

This is our destiny: to spread unmeasured love

Among treacherous or worthless things,

To give without limits to a total ingratitude,

And to search with hopeful patience, in love’s empty

Shell, for still more love.

To love our very lack of love, and to love in our dryness

The implicit water, and the tacit kiss, and that infinite thirst.

(Andrade, [1951]/2006, p. 263).

Well then, if all the letters haven't dealt with the subject of love, this is just an invitation to reflect on the subject, which is always around the edges of the novel To love. With regards to preceptorship as a philosophical inspiration, it should be added that in Plato's The Banquet there is a direct allusion to love being taught by a foreigner (like Fräulein). In one passage, Socrates declares that he has received lessons in love:

Now I’ll let you go. I’ll try to restate for you the account of Love that I once heard from a woman from Mantinea called Diotima. She was wise about this and many other things. On one occasion, she enabled the Athenians to delay the plague for ten years by telling them what sacrifices to make. She is also the one who taught me the ways of Love [...] (Platão, [380 a.C.?]/1996, p. 29).

Diotima, the preceptor remembered with admiration by Socrates, made her initiation into love (sexual and sentimental) not out of social disgust, or to escape the consequences of war, or for payment, proving to be a successful priestess of the pedagogy of love. Otherwise, “Educating that does not resist seduction causes a double failure, that of the educator and that of the seduced. To seduce is to lead to the path of learning, of conscious life, of continuous care for oneself” (Schüler, 2013, p. 238). But it's important to note, as Ramos (1979) infers, that in To love, the centrality is in the capitalist context and money appears as a relevant element, since the German governess taught for pecuniary advantage, both for subsistence and for her future return to her homeland.

More pragmatically, as far as love is concerned, in the essay called Love in literature: an exercise in historical understanding, Schpun (1997) explains that the preceptor Fräulein was given a very clear mission by Mr. Sousa Costa: to teach his son to be superior to women, and not only that, but to be distant and insensitive, in a kind of immunization against emotional and affective dependence on them. Now, insensitivity doesn't seem to go hand in hand with affection, with love, as Drummond's (2006) poem states. However, young Carlos' father acted with freedom, both at home and in the city, to repeat in his children the maintenance of the imbalance between the genders by teaching inequality in social roles and, not only in that, but also in love.

What kind of love is that? Similarly to Prost ([1989]/2020), the author Mônica Schpun shows in her essay that marriages at that time could be motivated by two things: financial interest or intimate and affective aspirations, a domain that corresponds to married life in the territory of love. However, she adds that the new adults of the 1920s, in the capital of São Paulo, witnessed sudden social changes fin de siècle, when a strong individualist notion was visible, in which the imposed matrimonial bonds waned and the supposed advantages of the father's financial estate dissolved with the absence of the idea of a dowry, which “[...] took away from women the important and essential trump card in the negotiations established at the time of marriage. For men, on the other hand, this increased their autonomy even more” (Schpun, 1997, p. 186).

It's important to note that the asymmetry put on one side women who wanted husbands with an aptitude for love (Besse, 1999, p. 42), even if it wasn't idyllic, but with the presence of affection, fidelity and sentimental interlocution, while the men saw that this love, as claimed by the women, consisted of a tormenting imprisonment because they had to give up the captivating alternative of having parallel relationships with so many other women, in favor of just one.

3 Final thoughts

To love is a non-traditional idyll, because it portrays the purity of fatality and thematizes a love that, having become a verb, is not conjugated in the absence of normative grammar as a way of criticizing the São Paulo bourgeoisie, which tried to be what it really wasn't in order to hide what it was.

The mask was not only on the face of this class but had been fitted to the face of the teacher Elza, who became Fräulein, an unnamed woman, in other words, a kind of priestess who taught love out of a need to survive and who helped us think about family and social relations in the capital of São Paulo during the years in which the novel was written. She is a cultured German woman who is content with superficiality in a dynamic in which even internal riches were nothing more than illusions. Her depersonalization occurs when other people's lifestyles become bigger than her own, regardless of the fact that the books in the mansion were nothing more than ornaments, revealing a teacher doomed to a mediocre life by embodying the political choice of various families, in which closed books had the same value as the varnish that foreign teachers could provide.

In addition to these considerations, on the question of the idyll related to the subtitle of the novel To love, a hasty analysis could lead the reader to mistakenly understand that Mário de Andrade's supposed confession would lead one to think that the imitation of Bernardin de Saint-Pierre had the meaning of a copy. On the contrary, Mário was only referring to the format and type of novel in which To Love is set, not the content. The novel has distinct characteristics from the French idyll, not in form, but in meaning, in the scope intended by Mário, in the appropriation made of a standard type of aesthetic for new content, superimposed on that mold. It is therefore unusual in content and ordinary in form due to the procedure of emulation.

Given the above, the writing of Mário de Andrade serves as an invitation to reflect on what else has served to educate us for life, beyond the traditional figures of school and human service.

REFERENCES

AMARAL, A. (org.). Correspondência: Mário de Andrade & Tarsila do Amaral. São Paulo: Edusp, 2001. [ Links ]

ANDRADE, C. D. Claro enigma (1951). In: ANDRADE, C. D. Poesia completa. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Aguilar, 2006. [ Links ]

ANDRADE, M. [Anotação manual]. Em folha, com marca de dobra, inclusa no caderno denominado “Vento”. São Paulo: [s.n.], 1925?a, n.p. Acervo do IEB, Universidade de São Paulo. [ Links ]

ANDRADE, M. [Apontamentos à margem]. In: EPSTEIN, J. Le phénomène littéraire: L’Esprit Nouveau, Paris, n. 11-12, p. 1218-1219, 1921. Acervo do IEB, Universidade de São Paulo. [ Links ]

ANDRADE, M. [Correspondência]. Destinatário: Manuel Bandeira. São Paulo, 11 maio 1925b. 1 carta. In: MORAES, M. A. (org.). Correspondência: Mário de Andrade & Manuel Bandeira. 2. ed. São Paulo: Edusp, 2001. p. 210-211. [ Links ]

ANDRADE, M. Amar, verbo intransitivo: idílio (1944). 16. ed. Belo Horizonte: Villa Rica, 1995. [ Links ]

ANDRADE, M. Amar, verbo intranzitivo: idílio. São Paulo: Antonio Tisi, 1927. [ Links ]

ANDRADE, M. O banquete. São Paulo: Duas Cidades, 1977. [ Links ]

ANDRADE, M. Αγαπώ, ρήμα αμετάβατο. Μεταφράστηκε από Nikos Pratsinis. Αθήνα: Printa-Ροές, 2017. [ Links ]

ANDRADE, M. Táxi e crônicas no Diário Nacional. Estabelecimento de texto, introdução e notas de Telê Porto Ancona Lopez. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 2005. [ Links ]

ASSIS, M. Do trapézio e outras coisas. In: ASSIS, M. Memórias póstumas de Brás Cubas (1881). São Paulo: Globo, 2008. p. 74-77. [ Links ]

BESSE, S. K. Modernizando a desigualdade: reestruturação da ideologia de gênero no Brasil, 1914-1940. São Paulo: Edusp, 1999. [ Links ]

BINZER, I. V. Os meus romanos: alegrias e tristezas de uma educadora alemã no Brasil (1956). 7. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2017. [ Links ]

BRITO, M. S. História do modernismo brasileiro: antecedentes da Semana de Arte Moderna. 5. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1978. [ Links ]

CAMÕES, L. Rimas. Sonetos. In: CAMÕES, L. Obras completas de Luis de Camões. Paris: Officina Typographica De Fain e Thunot, 1843. p. 44-181. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, L. E. A revista francesa L’Esprit Nouveau na formação das ideias estéticas e da poética de Mário de Andrade. 2008. Tese (Doutorado em Letras) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2008. [ Links ]

CERTEAU, M. A escrita da história (1975). 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 2020. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, R. História cultural: entre práticas e representações. Tradução de Maria Manuela Galhardo. 2. ed. Lisboa: Difel, 2002. [ Links ]

CUNHA, A. G. Dicionário etimológico nova fronteira da língua portuguesa (1982). 17. reimp. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 2005. [ Links ]

FERES, N. T. Leituras em francês de Mário de Andrade: seleção e comentários com fundamento na marginália. São Paulo: IEB-USP, 1969. [ Links ]

FRYE, H. N. A imaginação educada (1963). Campinas: Vide, 2017. [ Links ]

GASSET, J. O. Y. Meditações do Quixote (1914). Campinas: Vide, 2019. [ Links ]

GINZBURG, C. O fio e os rastros: verdadeiro, falso, fictício (2007). 3. reimp. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2017. [ Links ]

GREMBECKI, M. H. Mário de Andrade e L’Esprit Nouveau. São Paulo: IEB-USP, 1969. [ Links ]

IONTA, M. As cores da amizade: cartas de Anita Malfatti, Oneyda Alvarenga, Henriqueta Lisboa e Mário de Andrade. São Paulo: Annablume: Fapesp, 2007. [ Links ]

LOPEZ, T. P. A. A biblioteca de Mário de Andrade: seara e celeiro da criação. In: ZULAR, R. (org.). Criação em processo: ensaios de crítica genética. São Paulo: Iluminuras: Fapesp, 2002. p. 45-72. [ Links ]

LUCAS, F. Fronteiras imaginárias: crítica. Rio de Janeiro: Cátedra, 1971. [ Links ]

MICELI, S. Mário de Andrade: a invenção do moderno intelectual brasileiro. In: BOTELHO, A.; SCHWARCZ, L. M. (org.). Um enigma chamado Brasil: 29 intérpretes e um país. 3. reimp. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2016. p. 161-173. [ Links ]

MOISÉS, M. Dicionário de termos literários (1974). 16. ed. São Paulo: Cultrix, 2008. [ Links ]

PLATÃO. O banquete (380 a.C.?). Bauru: Edipro, 1996. (Coleção Clássicos). [ Links ]

PROST, A. Fronteiras e espaços do privado. In: PROST, A.; VINCENT, G. (org.). História da vida privada: da Primeira Guerra a nossos dias (1989). 4. reimp. São Paulo: Companhia de Bolso, 2020. 5 v. p. 13-136. [ Links ]

RAMOS, M. L. O latente manifesto. In: WALTY, I. C.; RAMOS, M. L. (org.). Ensaios de Semiótica, Belo Horizonte, n. 2, p. 76-103, 1979. [ Links ]

ROSENFELD, A. Texto/Contexto: ensaios. 2. ed. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1973. (Coleção Debates, 7). [ Links ]

SANT’ANNA, A. R. Poesia brasileira: uma trajetória do desejo. In: SCHÜLER, D. et al. (org.). O amor na literatura. Porto Alegre: UFGRS, 1992. p. 85-99. [ Links ]

SCHPUN, M. R. O amor na literatura um exercício de compreensão histórica. Cadernos Pagu, Campinas, n. 8/9, p. 177-209, 1997. [ Links ]

SCHÜLER, D. Abismados em amor. Porto Alegre: Movimento, 2013. [ Links ]

SHAKESPEARE, W. Romeu e Julieta (1597). Tradução de Barbara Heliodora. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 2011. [ Links ]

VOLÓCHINOV, V. A palavra na vida e a palavra na poesia: ensaios, artigos, resenhas e poemas (1926). São Paulo: 34, 2019. [ Links ]

1This article is an output of the doctoral thesis completed in 2022, which received funding from CAPES and was selected to receive the Capes Thesis Award 2023 in the field of education, according to the Diário Oficial da União of August 31, 2023, n.167, Section 3, p. 81.

2“From late Latin modernus, from mǒdus, based on hodiernus, from hodiē, ‘today’” (Cunha, [1982]/2005, p. 527). It is, for Moisés ([1974]/2008, p. 304-306), an unstable word from a semantic perspective, but which refers to the idea of something recent, new, a different trend. Brazilian Modernism came to propose an original, spontaneous, lively, engaged literature of a psychological nature, whose in-depth historicity of the antecedents that marked the 1922 event is contained in Brito (1978).

3According to Figure 1, it was spelled with “z” in the 1927 edition (São Paulo: Antonio Tisi), but changed to “s” in the version published in 1944. This was Mário’s stylistic choice to cause a double impact.

5In ancient times, it referred to any short lyrical, amorous, descriptive, dramatic or epic poem on rural or pastoral themes. Later, it came to be characterized as a sentimental story (Moisés, 2008). In To love, it is, in fact, a lesson on love, full of pain and disappointment.

6According to an excerpt from a letter to Manuel Bandeira: “My book of short stories is coming out soon, I don't know if I told you. Losango Caqui comes out this year. Now, on the 3rd or 4th, I'm going to the farm. I'll spend a month and a half there. A month's vacation and half a month's leave. I think that's enough for me to be a right man again. Maybe there I'll write a 'Praise of my native state', which I'm imagining, a poem of pure intellectual construction, don't be alarmed. Or I'll write Wind... Or John the Fool... I don't know. I don't think I'll write anything. Projects are so good to do!...” (Andrade, [1925b]/2001, p. 211).

9According to Lucas (1971), the title chosen by the author had the function of bringing together rapid communication and high impact on issues that seem to be of our time.

Received: July 20, 2023; Accepted: September 18, 2023; Published: October 18, 2023

texto en

texto en