Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação & Formação

versión On-line ISSN 2448-3583

Educ. Form. vol.8 Fortaleza 2023 Epub 18-Jul-2023

https://doi.org/10.25053/redufor.v8.e10059

ARTICLE

Life at a crossroads: high school students between the desire and the need to project the future

iFederal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. E-mail: liciniacorrea1@gmail.com

iiFederal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. E-mail: amaliacunha@fae.ufmg.br

This article chooses as an analysis scenario the implementation of a project of curricular reorganization in secondary education in the state public network of Minas Gerais that demands from the young people for whom this policy is addressed a reconfiguration of plans and a new calculation to prospect the future, anchored between desire and need. In the analysis, it becomes evident how much secondary education aimed at less favored groups has been instrumentalized, from a semantics anchored in the idea of “modernization” and “efficiency” of the school, application of economic logic to pedagogy, suggesting the transfer of market reason for the school. The methodology undertaken combined quali-quanti approaches, present both in the applied questionnaires and in the realization of focus groups with young people. To analyze this factual reality, we used a theoretical framework that has focused on the tensions of young people and the world of work.

Keywords: youth sociology; education/work relationship; social function of education

Este artigo elege como cenário de análise a implementação de um projeto de reorganização curricular no ensino médio na rede pública estadual de Minas Gerais que exige dos jovens para quem é endereçada essa política uma reconfiguração dos planos e um novo cálculo para prospectar o futuro, ancorado entre o desejo e a necessidade. Na análise, evidencia-se o quanto o ensino médio voltado aos grupos menos favorecidos tem sido instrumentalizado, a partir de uma semântica ancorada na ideia de “modernização” e “eficiência” da escola, aplicação de lógicas econômicas à pedagogia, o que sugere a transferência da razão do mercado para a escola. A metodologia empreendida combinou as abordagens “qualiquanti”, presentes tanto nos questionários aplicados quanto na realização de grupos focais com os jovens. Para analisar esta realidade factual, utilizou-se um referencial teórico que tem se debruçado sobre os tensionamentos do jovem e o mundo do trabalho.

Palavras-chave: sociologia da juventude; relação educação/trabalho; função social da educação

Este artículo elige como escenario de análisis la implementación de un proyecto de reordenamiento curricular en la educación secundaria de la red pública estatal de Minas Gerais que exige de los jóvenes a quienes se dirige esta política una reconfiguración de los planes y un nuevo cálculo para prospectar el futuro, anclado entre el deseo y la necesidad. En el análisis, se evidencia cuánto se ha instrumentalizado la educación secundaria dirigida a los grupos menos favorecidos, desde una semántica anclada en la idea de “modernización” y “eficiencia” de la escuela, aplicación de la lógica económica a la pedagogía, sugiriendo la transferencia de la razón del mercado para la escuela. La metodología emprendida combinó enfoques cuali-cuantitativos, presentes tanto en los cuestionarios aplicados como en la realización de grupos focales con jóvenes. Para analizar esta realidad fáctica, se utilizó un marco teórico que se ha centrado en las tensiones de los jóvenes y el mundo del trabajo.

Palabras clave: sociología juvenil; relación educación/trabajo; función social de la educación

1 Introduction

This article seeks to reflect on the resources that young people from the popular classes use to overcome the innumerable barriers of inequalities until they reach high school and carry out their school experiences in intense articulation with the demands of a society in transformation or even in the face of the need to have to design their future.

From the dialogue established with public high school students in the Metropolitan Region of Belo Horizonte (RMBH)1, Minas Gerais, we asked how young people who gradually reach this stage of basic education experience the contradictions of a schooling process that positions them at a “crossroads of life”, in which the search for meaning in the present is constantly undermined by the pressures of a future more and more uncertain.

The uncertain future is broadly related to a reformist wave in the educational field, identified by Laval (2019) as the recognition of neoliberalism in education. The use of a semantic anchored in the idea of “modernization”, “efficiency” of the school, and the application of economic logic to pedagogy, among others, evidences the transfer of the market logic to the school (LAVAL, 2019).

Secondary education, a field of ideological dispute, can be taken here as an example of the application of neoliberal logic to school education. The reform of secondary education and its recent implementation in Brazilian schools, entitled “new secondary education”, highlights, on the one hand, the setbacks of a historic dispute over the meanings, purposes, and formats that this last stage of basic education should have. On the other hand, it makes the connection between the curriculum reform more than explicit to the adaptations and interests of the market, the fulfillment of an international performance evaluation agenda, and the containment of access to higher education. In the latter, resides the dispute for a project to shape society.

When analyzing the assumptions that guided the approval of Law nº 13.415/2017, Kuenzer (2017) asserts that the much publicized reform of secondary education is nothing less than the materialization of the discourse of flexible accumulation in the field of education. For Kuenzer (2017), curriculum flexibility resides in the broader concept of flexible learning, a fallacy that, in practice, makes teaching even more exclusive, since, institutionalizing a fluid curricular organization, reduces the workload of common training, ranks disciplines in areas to be chosen early on by students and transfers to them the responsibility for defining their training itineraries.

This case study shows an unmistakable similarity in the operationalization of the neoliberal logic in the educational reforms promoted by the State, which seek, in the name of employability, the promise of innovation and a curriculum focused on the skills required by the market, under the slogan of “better” and more “efficient” school. For three academic years (2012-2014), young students from the state education system of Minas Gerais experienced the implementation, expansion, and extinction of a curriculum reorganization project that, based on the premise of an “adequate approximation between education, employability, and citizenship”, ignored the effective and concrete conditions of the school and the subjects who are in it.

Thus, the article takes as a scenario a project implemented by the State Department of Education of Minas Gerais (SEE-MG) called “Reinventando o Ensino Médio” (REM), whose objective was “[...] the creation of a cycle of studies with their own identity, which would simultaneously provide better conditions for the continuation of studies and more instruments that favor the employability of students at the end of their training during this teaching stage” (MINAS GERAIS, 2012, p. 11).

Our interest turns to the subjects for whom this policy and this “better and more efficient” school are directed, as we seek to understand, through qualitative research, how young people perceive these changes and produce subjectivities in response to the demands of a flexible capitalism. In addition, we are interested in investigating the meanings that these young people attribute to the implementation of an educational policy that not only changed the curricular reorganization and the class load, but that intended to reinvent secondary education by anchoring itself in “[...] three fundamental principles, which circumscribe its nature: meaning/identity, employability, and academic qualification” (MINAS GERAIS, 2012, p. 7)2.

The approach proposed here makes explicit the discourse, speeches, and perceptions of young people about the REM project and its schooling processes, by recognizing them as subjects who experience school beyond the acquisition of content and who, therefore, build and attribute meanings for the school and the relations established abroad, from its interior.

Thus, our analytical exercise came both from the interpretation of the speeches of the students, through the realization of focus groups carried out in schools, and from the interpretation of documents and resolutions related to the curricular reorganization implemented in the state.

2 Methodology

The research used in this work consisted of the diagnosis of the implementation of REM in the state educational system of Minas Gerais, between 2012 and 2014. The empirical basis consists of 33 schools in the RMBH, equally divided between the Metropolitan Regional Education Superintendencies (SRE) A, B, and C. These schools were the pioneers, it was in this set of educational institutions that the implantation took place (phase 1) and the expansion (phase 2) of the project.

To find out how, effectively, the new curricular organization occurred in the daily lives of high school students and teachers at RMBH, the research combined quantitative and qualitative approaches, which allowed us to understand how the implementation of REM affected the processes of schooling and the experience of school times and spaces.

The research was carried out in three stages, the first of which was limited to the analysis of the literature that discusses the themes: the relationship between students and school; identity and purpose of secondary education; as well as census data, guidelines, resolutions and official documents published by federal and state bodies concerning this stage of basic education and, specifically, official documents from the government of the state of Minas Gerais and SEE-MG that dealt with the implementation of REM.

In the second stage, we applied questionnaires to students in the 2nd and 3rd years of high school from all the schools that made up phase 1 of the REM and, to define the schools in phase 2, we used as criteria the socio-spatial context of the school, the adherence to REM and the areas of employability chosen by schools.

In the set of schools that make up the RMBH, we consider those located in industrial hub cities and in small towns with markedly rural characteristics. The same research design was applied in an article published by the authors (CORREA; CUNHA, 2018) to analyze the effects of educational policies on the daily practices of young students.

We chose to include a school close to public transport (bus and subway), which is highly convenient for working students, as we assume the need to combine a place of residence, school, and workplace. We applied 3,108 questionnaires, distributed in Metropolitan SRE A, B, and C.

In the third stage, we privileged the dialogue with students, to try to understand their experiences of REM in the school routine and the implications of the curricular reorganization, and their perspective on the conclusion of secondary education and continuity of studies. The focus groups were the way chosen to reach the subjects, the interpretations built and shared collectively about the experience of the policy in practice.

The REM project was implemented in 2012 and instituted a new proposal for the curricular organization for regular secondary education in the state education network in Minas Gerais, according to Resolution SEE-MG n 2.030. The test program was implemented in the 2012 school year in 11 schools of SRE Metropolitana C and, in 2013, it was extended to 144 schools. Of these, 22 are located in the RMBH, 11 of which belong to SRE Metropolitana A and SRE Metropolitana B. In 2014, the program was universalized to 2,149 schools in the state education system. In 2015, the program was extinguished, without the students being able to have the guarantee of terminality. REM's curriculum organization ensured 200 school days, in compliance with the National Curriculum Guidelines for this stage of basic education (BRASIL, 2012). The novelty of REM consisted in expanding the annual workload from 2,500 to 3,000 hours, distributed over three academic years, aimed at the development of general and specific training, which also allowed each student to choose different paths.

To understand what students say about their trajectories and school experiences, we try to get to know them. In the first place, we handed out questionnaires to those who attended the 2nd and 3rd years of high school and who had already been experiencing the new curricular organization for at least one school year. Of the total number of respondents (N = 3,108), 56.5% of young people were female and 43% were male. Regarding the age group of the sample, 78% were between 17 and 19 years old. Concerning the ethnic-racial variable, 68.5% of young people declared themselves to be black and 26.3%, white. As for religion, 43.6% said they were Catholic, 38.1% Evangelical and 12.2% said they had no religion. Of this total, 61.5% indicated that they lived with their parents, 27.9% with their mother only, and 10.1% with other family members.

When asked about what they most liked to do at school, students were categorical: meeting friends. Sociability is a constitutive dimension of youth life and it is also manifested in school. Paradoxically, when asked about the role of school, expanding opportunities in life, having a profession, and learning appear as the first, second, and third options, respectively. Family, school, and work are considered by young people to be the most important institutions in outlining their projects for the future.

Dialogue with young people, through the methodology of focus groups, made it possible to explain what grants positivity or negativity to youth during the schooling processes. Despite the structural issues that produce exclusion or foment an inclusion laden with perversity, the students told us that, in the cracks in the education system, they produce affectionate relationships with other young people, their families, and teachers. It is by looking at these fissures that we can glimpse and know the diversity of youth school experience in basic education.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Young people and school: the entanglement of a relationship built on the asymmetries of the system

The relationship between young people and school is a theme that has occupied research agendas, both in the governmental and academic spheres. Also for young people, the school experience and its implications for family life and the relationship with the world of work, leisure, and sociability do not go unnoticed.

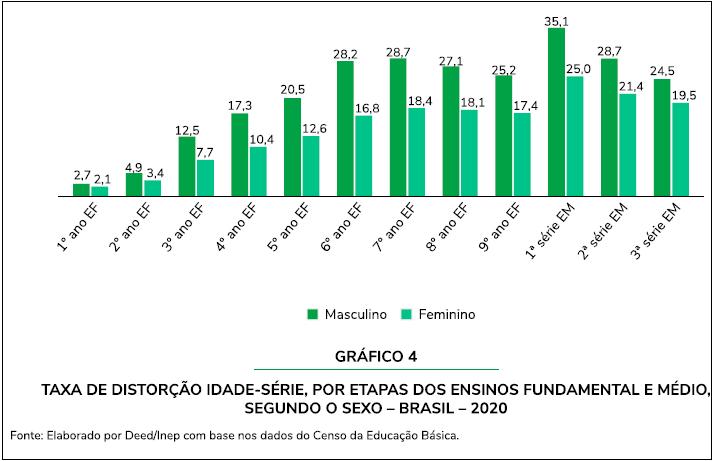

The high dropout and retention rates and the intercurrences that prevent and/or hinder the continuity of studies mobilize public agendas at municipal, state, and federal levels. This is because the problem of access and permanence in secondary education is intertwined with high retention rates, which are already alarming in elementary education. Data from the 2020 School Census report an increase in age-grade distortion rates from the 3rd year onwards, which rises in the 7th year of elementary school and reaches a peak in the 1st year of high school (BRASIL, 2021).

The transition to the 6th year of elementary school and the 1st year of high school shows bleak numbers, if we compare our evaluation of educational policies with policies in the field of health, economy, or even public safety. The age-grade distortion rates recorded in the 2020 School Census result in 22.7% in final years and 26.2% in secondary education (BRASIL, 2021). The age-grade distortion among male students is greater than that of female students at all stages of education. The greatest difference between genders is observed in the 6th year of elementary school, where the age-grade distortion rate is 28.2% for males and 16.8% for females.

Not by chance, Peregrino (2010) draws attention to the second segment of elementary school, the stage in which school inequalities deepen, in a scene that is repeated and that announces the survivors of high school: poor young people, condemned to a process of unschooling or, as Bourdieu and Champagne (1998) would say, condemned to assume the role of “excluded from the countryside” in Brazilian public schools. It must be considered that these data have other nuances in addition to dropout rates, retention rates, and age-grade distortion rates.

School inequalities in Brazil are limited to several axes of power, and this complexity evokes the concept of intersectionality (CRENSHAW, 2002). Class, race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, ableism, age, and territory constitute, paraphrasing the author, the avenues that structure the social, economic, and political terrains of what we call retention, age-grade distortion, and school dropout in the Brazilian educational system.

The data presented do not disregard the commitment of Brazilian society which, in the last decade, has significantly increased the net school rate among students aged 15 to 17 years and enabled an evolution in the average rate of years of study (CORREA et al., 2017). The expansion of secondary education brought young people from social strata previously excluded from formal schooling processes to school and represented a significant improvement in access to education for the Brazilian population. However, access and expansion of enrollments were still not enough to reverse the problem of permanence and quality.

Among the young people in our research, an insignificant number had interrupted their studies, but about 24.7% had already failed. Among the young people interviewed, 28.4% had failed in the early years of elementary school, 39.4% in the final years, and 35% in high school, a stage that was still ongoing for just over half of the respondents.

The document prepared by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF, 2019) presents the same data from the School Census (BRASIL, 2021), shown in Figure 1, broken down based on race, ethnicity, gender, and territory markers. The highest probability of failure is concentrated in students who are male, black, quilombola, indigenous, with disabilities, and who live in the North and Northeast regions of the country. These are poor students, mostly from public schools, those most affected by school inequalities.

If we can say that today we are experiencing a crisis of institutions, including schools, the question we must ask ourselves is: to what extent does the expansion of public schools to poor students, an expansion that is at the same time slow and degraded, makes it increasingly more “inhabited” and less “experienced” (as an institution) by its users, does it not discredit it as a possible space for building youth sociability and projects for the future? (PEREGRINO, 2010).

I wonder if that's it... That's where uncertainty comes in. ' Is this really what I want for my life?'. I don't know if it's just me, but when I started high school, one of the first things that came to my mind was: now that I'm becoming an adult, I'm going to start making my own choices and that's when I really have to take courses that will benefit me in things I want to pursue, so... But that's the question that drives me crazy, I think all young people think: 'What do I want to do?'. (Student, focus group at school C).

The doubts and questions expressed in the statement above denote that indetermination in the youth experience is even harder for young people who live in situations of material precariousness. The young people analyzed here experience a path of uncertainty: when they reach high school, they do so under the sign of vulnerability, as they reconcile study and work, and live in the present without being able to plan the future. Also, for them, the future constitutes the space of possible becoming (LECCARDI, 2005), but the absence of cultural, social, and economic resources prevents them from developing cognitive strategies of control over at that time of their lives. In the absence of support to build their autonomy, temporal acceleration is yet another source of social exclusion: “Everything changes. Until the start of high school, you are sure of everything; by the 2nd already comes the doubt; in the 3rd, you don't know anymore” (Student, focus group at school C).

When they reach high school, their relationship with the school starts to have other affectations. We highlight the world of work as a fundamental socialization dimension of youth life. Brazilian youth is marked by great diversity in terms of work experiences and their relationship with schooling. In this sense, the process of entering the labor market and work experiences are intertwined in their personal and school trajectories and the outlining of life projects.

3.2 Young people at the intersection between school and the world of work

For young people, work does not have a single meaning. It is an intersection between necessity and possibility, between obligation and the desire for personal fulfillment. In this respect, for some, work appears as an experience concomitant with studies or even driven by schooling; for others, as a way of being young and a way of being someone in life. Among the young people surveyed who were working, 85.5% said that work had implications for their plans for the future.

Although our research covered the inclusion of young people in multiple socialization processes, we chose to address in this article the interrelationships between student experiences in the world of work, connected to the school context, as we understand that both have a great impact, from a very early age, in the youths lives and are, therefore, socializing instances that “make youths”.

When examining data from the Brazilian Youth Profile survey, Guimarães (2005) asserts that work is a theme that is on the agenda for young Brazilians, it has multiple meanings and appears, for young people, as a value, a need, and a right. To understand the relationship between youth and work, it is important to outline that the theoretical construct “youth” is not univocal and that work as a specific field has its own rules for age or generational cuts. Guimarães (2005) points out that, in the labor market, there are different forms of professional socialization of young people who, due to their distinct feeling of belonging, build different perceptions, representations, aspirations, and interests.

The centrality of work in the youth imagination and its subjective meaning is not a coincidence. A significant portion of young people have their experiences referenced in the world of work and the first evidence is that this insertion is impacted by demographic dynamics and its determinants. A second piece of evidence in this context comprises the relationship between schooling and job opportunities, which leads us to an analysis of the patterns of inclusion and exclusion in the Brazilian school system. The third piece of evidence concerns the forms of youth entry into the labor market: informal intermediation mechanisms, intense transitions, and precarious working conditions do not diminish their meaning and importance for the youth social experience.

In recent works by Corrochano, H. Abramo, and L. Abramo (2017), we glimpse an attempt to escape the false duality built around the relationship of young people and the world of work, concomitantly with schooling. “An empty head is the devil's workshop” or “studying to be someone in life” are the old saying and the old jargon that in no way explain youth work experiences.

The relationships that young people establish with these two socializing instances are different, therefore it is not the postponement of the entry into the world of work that will solve the serious educational problems and, consequently, improve the conditions of labor insertion, nor is inactivity a serious problem of poor young people that needs to be equated with labor insertion.

It was only in recent decades that the understanding of work as a constitutive dimension of youth life began to reverberate in public policies aimed at youth. The incorporation of youth demands into the government agenda occurred in the wake of the construction of the National Agenda for Decent Work (ANTD) and the National Plan for Employment and Decent Work (PNETD).

The mobilization for the construction of a National Agenda for Decent Work for Youth (ANTDJ) brought together a group representing different levels of government, business confederations, trade union centrals, the National Youth Council (Conjuve), and the National Youth Council (Conanda). Researchers from the field of Youth and Sociology of Work joined this group, who, through studies and research, expanded the debate on the themes and presented demands that were invisible in the social scene.

Recognize and promote the right to work, examine the conditions in which young people enter the labor market to understand the extent to which the work conditions interfere with schooling, family life, leisure time, the meanings that work acquires for the acquisition of autonomy, and social inclusion are some of the issues that permeated the definition of priorities at ANTDJ.

In the testimonies of young people, job satisfaction invariably appears, adding to frustration and anguish due to the difficulties in reconciling school and work. In another dimension, however, work is seen as an expansion of the field of possibilities, of perspectives for the future.

I had some options until I started working, then I started to see other areas, in which I started to be more interested, but the most I wanted to do was Civil Engineering, then I was going to take a technical course to be able to join college already knowing what will more or less happen within the area. Kinda confusing... Because then I have this desire to do Civil Engineering, but I'm working in an environmental company, then I start to be interested in other areas related to the environment, like Biology, Environmental Engineering. (Student, focus group at school C).

When asked if work harmed school performance, 24% answered yes. Of these, 56.4% attributed this impairment to fatigue and 29.7% to lack of time to study. And the vast majority of students surveyed? Why don't they see the harm in reconciling school and work? The answers can come from several factors, and this stems from the fact that the overlap of these two activities does not occur for all young people. The age at which they start working, the time of their schooling, the type of work, and family conditions are some of the nuances that unite and separate young people when it comes to work. There are those cases in which there is respect for student-worker conditions in such a way that working hours are flexible due to the school calendar.

Mediator: How is that? How do you do both?

Student: In the rush, right? Because I get to work at half past two in the afternoon, then everything is in a rush. Home life is put to the side, only on the weekend. (School A focus group).

Among the topics still little discussed, Corrochano, H. Abramo, and L. Abramo (2017) highlight the unpaid domestic work that young women generally do. For many of them, motherhood is an obstacle to the continuity of their studies, as the lack of public care services and equipment prevents them from dedicating themselves to their studies. Problems related to urban mobility also appear to young people as an obstacle in reconciling work and studies: “I helped my father because I bought my things and he didn’t have to pay!” (Student, focus group at school B).

The troubled family relationships and domestic violence are also factors that accelerate the decision to work:

Student: I work because, because I always have, my main objective was to leave home. My life at home was hell, not only because of fights, but because of much more serious problems that I can even talk about, today it doesn't bother me anymore, but the social issue was very uncomfortable, it was very uncomfortable, and then I needed to get out of the house. I've always worked intending to leave home and it's been more than a year since I've lived alone. Today I live with my fiance, in fact, but it's, let's say, to have what I wanted, inside my house. I had a stepfather who abused me, a mother who pretended not to notice, a religious mother - I don't believe in God - and that's how it was: there was chaos, so I left home. I worked so I could leave the house.

Mediator: How old are you?

Student: 17. (Focus group from school A).

Reconciling study, work, and other demands of youth experience, such as family life, culture, and leisure, is an arduous task for young people. Long working hours, precarious work conditions, and school hours, sometimes long and almost no flexibility, affect youth life.

Failure to comply with labor legislation and regulations defined in the Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescentes are issues on which the Subcommittee made little progress, as stated by Corrochano, H. Abramo, and L. Abramo (2017). If this theme, which strongly affects youth school trajectories, due to its varied nuances, was not reached by consensus, the issue of double and triple working hours associated with domestic work and family responsibilities for young mothers and young fathers generated an intense debate about the permanence of the sexual division of domestic work and the gender effects that prevent young mothers from continuing or resuming their studies.

Finally, the issue of professional qualification of young people who are or who wish to enter the world of work highlights a set of public policies that, in the form of programs and projects, are proposed to raise schooling and stimulate professional qualification to mitigate the problems of unemployment and precariousness (informality) and the difficulties of insertion and permanence in work. Low schooling, poor quality of education, and little or no professional qualification are, for employers, the biggest obstacles to the insertion and permanence of young people in the labor market. With this in view, REM was instituted.

3.3 And REM, what does it have to do with it?

I, to be honest, I chose to study Tourism, because it was the only one - how do you say it? -, the only course that had empty spots, and then, like, you were going to go through a lottery, and we concluded with the vice-principal that if we, I plus - I think - five friends, if we chose Tourism so there would be no confusion, not having to do this whole lottery, and we could all be together. And that's why I chose Tourism, it wasn't because I wanted to do Tourism, no. (Student, focus group at school A).

The above excerpt concerns one of the issues most reiterated by young people when they talk about REM. Unlike the young students whose schools participated in the first phase of the program's implementation, the young people who joined in the following year - the expansion phase - could not choose the areas of employability they wanted to study, nor was there an offer of 18 areas, such as appears in the official document. If, in the first phase of the program, there was an investment in financial resources, human resources, infrastructure, and equipment, in the later phases, students and managers felt completely helpless.

The implementation of REM in the 33 schools surveyed caused significant changes not only in the students' routine but in the teachers' work and functional routine, although a gradual implementation was intended. In our research, we heard reports from young people who emphasized the potential of a proposal that brought a certain convergence with their demands and interests and pointed to their present and future projects:

I think it's irrelevant, useless, meaningless, and a hell of a lot to do, because if you want to reinvent high school, it's like I said, the laptop issue, that would reinvent it much better, in a much more efficient, in addition to that we have one, an English class too that I don't know what it's for. Want to reinvent high school? Reinvent, put a teacher from a course to teach English [...]. (Student, focus group at school D).

In a context of accentuated fragility, REM, daily and operationally, translated into yet another promise. An ill-fated promise to reconcile the world of school and the world of work and still respond to the challenges of the contemporary world. In the following report, the student's criticism goes into two dimensions:

The problem with education is that, as it is in the long term, in Brazil, politics, involves a lot, because, when Reinventando o Ensino Médio started, it was party X that was in government and, when it ended, it was the Y party that was in the office, and they didn't have a similar ideology. So, it turns out, instead of joining forces to build something good, it's a partisan dispute, right? (Student, focus group at school A).

Although this last excerpt explains a belief in the potential of REM, one can see, in this excerpt, an indisputable criticism directed at the implementation of the policy that, despite the multiple issues that intersect the condition of young people in their relationship with the school, makes it unfeasible significant educational relationships and reinforces the legitimacy crisis experienced by educational institutions (DUARTE et al., 2020). Policies that, like other historically known ones, are implemented under the understanding that it is necessary to raise the proficiency/performance indexes of our high school students or under the pretext of qualifying them for the job market.

From another point of view, this same youngster unveils the problems of discontinuity of public policies, which, in the case of REM, became extinct ignoring the impacts of this interruption on life projects and on the schooling processes of the subjects for whom it was intended. In a lucid reading of the need for a time frame that exceeds the times of political mandates, this same person tells us that: “Education is long term, it is no use wanting to do it today and have an answer tomorrow”.

In this way, the REM implementation process showed that, between the ideal of an educational policy and the reality of schools and their subjects, there is a long distance. According to Laval (2019, p. 19):

[...] the reformist drive in schools presents its intentions in diffuse ways, by combining, in the discourse, the prerogatives of a republican school, which should form citizens and, at the same time, a school concerned with producing 'human capital', using the techniques and the best ethical intentions.

4 Final considerations

More than a controversial topic, secondary education has provoked intense debate in recent times. A debate that extends to all corners of the country, with the participation of students, researchers, social movements, government agencies, and organized civil society. REM is an educational issue that has occupied the political agenda and manages to simultaneously mobilize the Executive, Legislative, and Judiciary powers. This fact reveals that the policies of democratization of Brazilian education have not yet been consolidated. There is a significant demand for schooling in secondary education, despite the massification of education.

The 1990s inaugurated the institutional normative parameters that have guided educational policies for basic education. The emblem "democratization of education" sheltered a set of educational reforms that, on the one hand, met the demands of organized civil society and social movements in the struggle for equal rights and, on the other hand, positioned the country to the demands of global economic orders. The programs and projects that accompanied this period are represented in the expansion of enrollments and in the quest to mitigate social and economic gaps, although overcoming school inequalities remained untouched.

Expectations of social mobility via schooling are an old and recurrent theme that permeates the relationship of young people with school and, together with other factors, contribute to the way they build the “student craft”, that is, how they experience it in their daily lives (PERRENOUD, 1984, p. 19). As the author states, schooling is a long march and it can be a long and difficult march for young people who, due to their factual conditions, are left behind and, therefore, must prepare for more difficult tomorrows.

Despite unfulfilled promises, young people are optimistic, believe in school and the mobilizing potential of schooling, and experience school as a locus of training and socialization. They confirm the need and importance of experience, school knowledge, and cultural notions that the school transmits to carry out its projects (CORREA; CUNHA, 2018).

Especially concerning future projects, young people emphasize the importance of school in guiding their personal and professional choices. If the extension of schooling is a right, it should be converted into benefits, as happens to the most favored social groups. However, the more they “can” enter the education system, the less they study. The longer the period of schooling, the more difficulties they encounter in entering or remaining in the world of work, and the school institution ends up becoming a “[...] kind of promised land, similar to the horizon, which recedes as it becomes move towards you” (BOURDIEU; CHAMPAGNE, 1998, p. 221).

Young people underline the school as the place of confrontation between a diversity of cultures and values by highlighting the privileged place of this institution in their lives and their daily lives. Thus, we understand that the school, whether for its role in transmitting values or in the confrontation with other values and cultures, should be better dimensioned in future research, always articulated with other institutions that cross the lives of young people, such as the family, work, leisure, culture and all the paradoxes implicit in the idea of knowledge as a production value.

REFERENCES

ARAÚJO, L. A. Experiências e vivências escolares de docentes do ensino médio: um estudo de caso. 2017. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação e Docência) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação e Docência, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2017. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, P.; CHAMPAGNE, P. Os excluídos do interior. In: NOGUEIRA, M. A.; CATANI, A. (org.). Pierre Bourdieu: escritos de educação. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1998. p. 217-227. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Censo da educação básica 2020: resumo técnico. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 13.415, de 16 de fevereiro de 2017. Altera as Leis nos 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional, e 11.494, de 20 de junho 2007, que regulamenta o Fundo de Manutenção e Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica e de Valorização dos Profissionais da Educação, a Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho - CLT, aprovada pelo Decreto-Lei nº 5.452, de 1º de maio de 1943, e o Decreto-Lei nº 236, de 28 de fevereiro de 1967; revoga a Lei nº 11.161, de 5 de agosto de 2005; e institui a Política de Fomento à Implementação de Escolas de Ensino Médio em Tempo Integral. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Poder Executivo, Brasília, DF, 17 fev. 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Resolução CNE/CEB nº 2, de 30 de janeiro de 2012. Define Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Médio. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Poder Executivo, Brasília, 31 jan. 2012. [ Links ]

CORREA, L. M. et al. Escola como locus da formação continuada e o Pacto Nacional pelo Fortalecimento do Ensino Médio: efeitos na vida dos professores. Revista em Aberto, Brasília, DF, n. 98, v. 30, p. 87-104, 2017. Disponível em: http://rbep.inep.gov.br/ojs3/index.php/emaberto/article/view/3186. Acesso em: 18 maio 2022. [ Links ]

CORREA, L. M.; CUNHA, M. A. A. A política educativa e seus efeitos nos tempos e espaços escolares: a reinvenção do ensino médio interpretada pelos jovens. Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, n. 34, p. 1-30, 2018. [ Links ]

CORROCHANO, M. C.; ABRAMO, H. W.; ABRAMO, L. W. O trabalho juvenil na agenda pública brasileira: avanços, tensões, limites. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios del Trabajo, [S.l.], v. 22, n. 36, p. 135-169, 2017. [ Links ]

CRENSHAW, K. Documento para o Encontro de Especialistas em Aspectos da Discriminação Racial Relativos ao Gênero. Estudos Feministas, Florianópolis, n. 10, p. 171-188, 2002. [ Links ]

DUARTE, A. M. C. et al. A contrarreforma do Ensino Médio e as perdas de direitos sociais no Brasil. Roteiro, Joaçaba, v. 45, p. 1-26, 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18593/r.v45i0.22528. Disponível em: https://periodicos.unoesc.edu.br/roteiro/article/view/22528. Acesso em: 19 maio 2023. [ Links ]

GUIMARÃES, N. Trabalho: uma categoria chave no imaginário juvenil?. In: ABRAMO, H. W.; BRANCO, P. P. M. (org.). Retratos da juventude brasileira: análise de uma pesquisa nacional. São Paulo: Instituto Cidadania: Perseu Abramo, 2005. p. 175-214. [ Links ]

KUENZER, A. Z. Trabalho e escola: a flexibilização do ensino médio no contexto do regime de acumulação flexível. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 38, n. 139, p. 331-354, 2017. [ Links ]

LAVAL, C. A escola não é uma empresa: o neoliberalismo em ataque ao ensino público. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2019. [ Links ]

LECCARDI, C. Por um novo significado do futuro: mudança social, jovens e tempo. Tempo Social, São Paulo, v. 17, n. 2, p. 35-57, 2005. [ Links ]

MINAS GERAIS. Reinventando o Ensino Médio. Belo Horizonte: Secretaria de Educação, 2012. Disponível em: https://www.educacao.mg.gov.br/images/stories/publicacoes/reinventando-o-ensino-medio.pdf. Acesso em: 9 jan. 2014. [ Links ]

PEREGRINO, M. Trajetórias desiguais: um estudo sobre os processos de escolarização pública de jovens pobres. Rio de Janeiro: Garamond, 2010. [ Links ]

PERRENOUD, P. Ofício de aluno e sentido do trabalho escolar. Porto: Porto, 1994. [ Links ]

UNICEF. Reprovação, distorção idade-série e abandono escolar. Brasília, DF: Unicef, 2019. [ Links ]

1Part of the data used here also composes the research entitled Experiences and school perceptions of high school teachers: a case study (ARAÚJO, 2017). Process number: CAAE: 57293316.7.0000.5149, received and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais.

Received: March 23, 2023; Accepted: May 17, 2023; Published: June 15, 2023

texto en

texto en