Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Realidade

versión impresa ISSN 0100-3143versión On-line ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.44 no.2 Porto Alegre abr./jun 2019 Epub 26-Mar-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-623681355

OTHER THEMES

Flexibilization and Intensification of Teaching Work in Brazil and Portugal

IUniversidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), São Paulo/SP - Brazil

The main goal of this text is to present to the readers an analysis on the impact of the work flexibilization and intensification in the career of teachers from Brazil and Portugal, which have occurred in the last 27 years. Also, we highlight the main legislation of the countries that have led to the increase of the flexibility and intensification of the teaching work. For the study we performed bibliographical, documental and empirical research. The empirical data collection was performed through semi structured interviews. Although Brazil, the state of São Paulo and Portugal have distinct socioeconomic, political and institutional realities, we can verify that there is a convergence between the countries in relation to the phenomenon of the precariousness of teaching work.

Keywords: Flexibility; Intensification; Teaching Work; Brazil; Portugal

O principal objetivo deste texto é apresentar aos leitores uma análise sobre os impactos da flexibilização e da intensificação do trabalho na carreira dos professores do Brasil e de Portugal, ocorridos nos últimos 27 anos. Ainda, destacamos as principais legislações dos países que levaram à ampliação da flexibilização e intensificação do trabalho docente. Para o estudo, realizamos as pesquisas bibliográfica, documental e empírica. A coleta de dados empíricos foi realizada por meio de entrevistas semiestruturadas. Embora o Brasil, Estado de São Paulo, e Portugal possuam realidades socioeconômicas, políticas e institucionais distintas, pudemos verificar que há uma convergência entre os países em relação ao fenômeno da precarização do trabalho docente.

Palavras-chave: Flexibilização; Intensificação; Trabalho Docente; Brasil; Portugal

Introduction

Rising in the last forty years in the countries of central and peripheral economy, the precariousness of work has become a phenomenon that affects workers of diverse categories. An element of productive restructuring that was consolidated following the economic crisis of the 1970s, the precariousness of labor can be understood, according to Antunes (2009, p. 234), in its multiple "[...] time, functional or organizational" dimensions.

Antunes (2009) argues that the main concept that characterizes the precariousness of work is flexibility. For the author (2009), the precariousness of work produces flexibilization of the working hours (extended or flexible part-time work), the salaries (adoption of bonuses) and the functions and organization of the subjects, requiring the participation of the workers in various activities and stages of the production process.

While for Antunes (2009) the precariousness of work can be understood as flexibility, for Alves (2007, p. 114) "Casualization has a sense of loss of rights accumulated over the years by the most diverse categories of wage earners". Thus, in this article we discuss how the so-called flexibilization and intensification process cause the precariousness of the work of teachers and how the changes and approval of new educational legislation resulted in the loss of the rights of teachers from São Paulo and Portugal.

Work flexibilization is the expansion of the work activities developed by teachers; and the work intensification is the quantitative expansion of the number of classes, groups, students, work shifts and schools in which the teachers teach.

For this study we developed bibliographical, documental and empirical research. In the bibliographic research we selected books, scientific articles, theses and dissertations that dealt with the precariousness of work and teaching work themes. In the documental research, we selected and analyzed the main legislation promulgated and applied in the last 30 years by the State Department of Education of São Paulo and the Ministry of Education and Science of Portugal, which resulted in the expansion of flexibilization and intensification of teaching work. Also, we analyzed newsletters, pamphlets, trade union information and newspaper reports that address the precariousness of teaching work in the state of São Paulo and in Portugal.

For the collection of empirical data we conducted semi structured interviews with 20 teachers who teach in two Brazilian state schools located in the city of Marília, ETEC Antônio Devisate and EE Prof.ª Maria Cecília Ferraz de Freitas, and 17 teachers from two groups of schools, Grouping Alberto Sampaio and Carlos Amarante, located in the city of Braga, Portugal.

In order to select the sample of schools and teachers for the interviews, we used the following criteria: we selected the professionals who have been teaching for at least 20 years, so that the teacher could reflect on their work experience in the last three decades; we chose the schools with higher scores in the external evaluations carried out by the responsible bodies, considering the hypothesis that the engagement of the teachers in the activities, so that the school reaches higher indexes in the evaluations, could influence the flexibility and intensification of their work.

It should also be pointed out that we selected only schools that offer vacancies in elementary school (final years) and high school, in the state of São Paulo, primary and secondary schools in Braga, Portugal, and teachers who teach in the respective phases. The reason for this selection is the fragmentation of the disciplines and the need for teachers to teach in various institutions, classes and periods, corroborating that the intensification of teaching work is most evident at this stage of teaching.

Flexibilization of Teaching Work

Flexibilization is one of the elements that are part of the precariousness of the work that has affected workers of distinct categories, including the teaching category of the countries investigated in this study: Brazil and Portugal. The flexibilization of teaching work is characterized by the expansion of the competences and functions that must be performed by this professional inside and outside the school.

In the last 27 years, the volume of tasks carried out by teachers who teach in state schools in São Paulo has been widely extended. The main reasons for the expansion of functions and activities were the increase of administrative-bureaucratic work, that is, the role of teachers in meetings and councils and the increase of the paperwork that teachers need to fulfill (forms, frequency controls, assessments), as well as the participation of teachers in activities that are carried out outside the classroom.

In addition to bureaucratic tasks, teachers should participate in projects that stimulate the practice of students' sports activities, the organization of typical parties and events and campaigns carried out by the school. For Oliveira (2004, p. 1132), what happened in recent years was the expansion of the competences inherent in the work of the teacher, requiring that the teacher be a multipurpose or multi-tasking professional.

Teaching work is not defined as a classroom activity anymore, it now comprises the management of the school as it relates to the dedication of teachers to planning, project design, collective discussion of the curriculum and assessments. Teaching work expands its scope of understanding and, consequently, the analyzes about it tend to become more complex.

In relation to the activities that teachers develop and that exceed the knowledge available for the exercise of their profession, Oliveira (2012, p. 8) points out that the current school "[...] brings other tasks to the teachers that go beyond what is established by their function: taking care of hygiene, nutrition, health, among other needs of their students". Therefore, they are activities unrelated to the work that must be developed by teachers in the classroom; as well, they have no relation with the knowledge acquired by these professionals throughout their academic training.

In addition to the tasks that escape the training of teachers, bureaucracy is pointed out as another element of the work flexibilization, considering the need to prepare, including at times of rest and outside the school, "Student assessment forms, frequency charts, catalogs of activities with families and their communities that involve standardized procedures and that are considered by teachers as excessive bureaucracy" (Assunção; Oliveira, 2009, p. 356-357).

In the interviews we conducted, Teacher 1, who teaches at Antônio Devisate State Technical School, located in the city of Marília, emphasized that one of the factors that increased the volume of his work was the time devoted to the paperwork bureaucracy, which was previously carried out by the secretaries at the central office.

[...] there is a lot of the bureaucratic issues, and now they have created the electronic device, the teacher has to enter the grade and such and such, and I do not know what, then it is a great accumulation of work. You want a xerox copy, you want to create something there, and you have to go after it, you have to get it, do everything and everything on top of the teacher, and besides that, in my case, I have 64 classes a week.

Regarding the activities dedicated to the management of the school, Teacher 8, from the State School Prof. Maria Cecília Ferraz de Freitas, stated that

They are always demanding, asking for something extra. The central office loves to push these things, you have to do this, you have to do that, but the class-activity time out of class, outside the pedagogic scope, they do not increase it, it's always the same.

The democratic management at school was one of the main demands of teachers in the 1980s, and the education movement gained its inclusion in the 1988 Federal Constitution and the National Education Bases and Guidelines Law N. 9394, dated December 20, 1996. However, for Oliveira (2012, p. 66) "[...] the educational reforms of recent years, including democratic-popular administrations, have brought new professional demands for teachers without the necessary adjustment of the working conditions", considering that the number of classes taught weekly was not reduced so that the teachers could dedicate themselves to management tasks.

According to Inforsato (2001), the accumulation of teachers' activities is not directly related to the democratic management, as presently there is little or no democracy in schools. According to the author, the work flexibilization is associated with the business management model imposed on schools in the last 27 years, which has caused the loss of the autonomy of teachers and managers and increased their work functions.

The teachers of the state schools of São Paulo highlighted in their interviews that there has been an increase in the work flexibilization in the last decades. This phenomenon is based on the 1996 Bases and Guidelines Law (LDB), which outlines the activities that teachers must fulfill. According to article 13 of LDB (Brasil, 1996), besides participating in the preparation of the pedagogical proposal, teaching, planning and evaluation, teachers should collaborate with the activities of articulation of the school with the students' families and the community. Therefore, the law ratifies and legitimizes the flexibility of teaching work, given the diversity of functions that are required from these professionals.

Another factor that contributes to the flexibility of the work of teachers is their inclusion in projects, programs, training courses, etc. In the specific case of the Education Department Education of the state of São Paulo there are training programs, online courses offered regularly by the Department and the participation of teachers is required in continuing education projects, for instance, the Rede São Paulo Training Teacher (REDEFOR).

In this way, teachers have become multi-tasking and multipurpose professionals, taking into account the characteristics and profile of the employees who are recruited to work in the business sector. Thus, teachers do not have the time to update their classes or reflect on their teaching practice, after all, teaching an average of 40 hours a week "[...] how much pedagogical time is dedicated to reflection, reading the world, in a school work organization that imposes a factory rhythm on the teacher?" (Santos, 2012, p. 66).

In Portugal, one of the main reasons for the flexibilization of teaching work was the same that triggered this phenomenon in Brazil, that is, the increase in the volume of tasks performed by teachers due to the model of educational management. Following the Carnation Revolution and the reform of the education system aimed at the democratization of public education, teachers demanded a management model that would guarantee the autonomy of schools and the participation of teachers in the management decisions of institutions.

However, since the 1980s, the democratic management of the Portuguese school has gradually been transformed into a management model that requires the participation of teachers in various activities carried out at school and the responsibility for, control, effectiveness and efficiency in the accountability of managers and teachers. The new management model was implemented in the 1980s, according to the report of the Ministry of Education and Science, which addressed the situation of Portuguese teachers in that period.

In addition to school work, teachers are also required to attend various teacher meetings and work meetings with other colleagues. [...] In addition to teaching and attending meetings, teachers, although they have no specific preparation for this purpose, also carry out managerial and administrative functions, both administrative and pedagogical. For many, the exercise of these functions represents even more professional obligation (Commission Report, 1988, p. 1231).

According to Machado and Formosinho (2009, p. 310), the new teacher needed to deal with the various tasks assigned to them at school, although their training had not prepared them to perform this function, and a missionary spirit was necessary to deal with the challenges of career, among them, to assume the profile of a multifaceted professional, acting as "[...] teacher, class director, discipline delegate, department coordinator, pedagogical advisor, continuous training monitor, school manager, appraiser, etc.".

Due to an overloaded work routine, teachers present emotional problems such as stress, depression and burnout, and physical conditions such as tiredness, orthopedic diseases, tendinitis, low back pain, bursitis, arthritis, hypertension, vascular or voice-related problems. According to Pinto (2000, p. 330), health problems unleashed in teachers are consequences of "the overload of work to which the teacher is subject, which is results from the discrepancy between the multiple requirements that made to them".

In interviews conducted at the Alberto Sampaio Secondary School, located in the city of Braga, the 10 teachers interviewed confirmed that the volume of work has increased in the last 25 years. According to Teacher 2, the amount of work increased,

[...] especially because of these new technologies. On the one hand, new technologies make it easier, but on the other they invade the 24-hour day. And we have enough school situations that come in for more work. [...] The teacher has to do something else anyway. The teacher has to do bureaucratic matters in addition to the lessons. I have a little more work in recent years because I am the delegate of the group, and I have more and more things to do.

The main Portuguese legislation that elucidates the functions of teachers is the Statute of the Career of Childhood Educators and Basic and Secondary Education Teachers. The first approved Statute was Decree-Law N. 19-A, of April 28, 1990 (Portugal, 1990) and, since its first version, the teacher's working day has been divided into two parts: the teaching component and the non-teaching component.

In 1990, the teacher's workday was 35 hours per week. For teachers who taught in the 2nd and 3rd cycles of basic education, the teaching component was 22 hour per week and the non-teaching component was 13 hours per week. In the secondary education, the teaching component was 20 hours per week and the non-teaching component was 15 hours per week. The teaching component, that is, the work that the teacher developed with the student in the classroom, could not exceed 5 hours per day. The non-teaching component was composed of a series of activities, among them:

Art. 82

2 - The work at the individual level may include, in addition to the preparation of classes and evaluation of the teaching-learning process, the preparation of studies and research works of a psychological or scientific-pedagogical nature.

3 - The work at the educational or teaching institution must be integrated into the respective pedagogical structures with the aim of contributing to the educational process of the school, which may include:

Educational information and orientation of curricular complement that aim to promote the cultural enrichment and the insertion of the students in the community;

Information and educational guidance of students, in collaboration with families and with local and regional school structures;

Participation in legally convened pedagogical meetings;

Participation promoted under the legal terms or duly authorized, in continuous training actions or in congresses, conferences, seminars or meetings to study and debate issues and problems related to teaching activities;

Replacement of other teachers from the same educational or teaching institution;

Development of studies and research work that, among other goals, aim to contribute to the promotion of school and educational success (Portugal, 1990, p. 23).

In 2007, the Statute of the Teaching Career suffered the fifth amendment and became the most rigorous legislation among the previous versions. The new version of the law was highlighted due to the requirements related to the evaluations, the compulsory role of the principal in all school units, the increase in class hours and the division of the teaching career between teacher and full teacher. We highlight in the wording of article 35 the main functions assigned to the position of teacher.

To teach the disciplines, subjects and courses for which it is qualified according to the educational needs of the students entrusted to it, and in the fulfillment of the teaching service assigned to it;

To plan, organize and prepare the academic activities aimed to the group or group of students in the disciplinary areas or matters that are distributed to it;

To design, apply, correct and classify learning assessment tools and participate in the evaluation service and evaluation meetings;

To prepare resources and didactic-pedagogical materials and to participate in the respective evaluation;

To promote, organize and participate in all complementary, curricular and extracurricular activities, included in the school's plan of activities or educational project, inside and outside the school premises;

To organize, to assure and to accompany the activities of curricular enrichment of the students;

To ensure educational support activities, implement the follow-up plans of students determined by the educational administration and cooperate in the detection and monitoring of learning difficulties;

To monitor and guide students learning in collaboration with parents and caregivers;

To provide guidance and counseling in the students educational, social and professional fields, in collaboration with specialized educational guidance services;

To participate in the evaluation activities of the school;

To advise supervised pedagogical practice at the school level;

To participate in activities of research, innovation and scientific and pedagogical experimentation;

To organize and participate, as a trainee or a trainer, in continuous and specialized training;

To carry out the activities of administrative and pedagogical coordination which are not exclusively committed to the full teacher (Portugal, 2007, p. 507).

We can see that in the 2007 Teaching Career Statute, there was an increase in the number of tasks assigned to teachers. While in the 1990 Statute it was up to the teacher to perform six functions, besides the work done in the classroom, in the 2007 version of the legislation ten functions were added to the teachers, besides teaching.

Among the tasks that stand out in this article, the main ones are focused on the preparation and participation of the teachers in the evaluations. In the interview we conducted with Teacher 4 of Carlos Amarante High School, the professional commented on the centrality of the evaluations, "It is so, it has really increased because with this question of the evaluation system, the teachers want to show more work, as they do more activities when pushed by norms".

In addition to evaluations, the teacher was required to participate in complementary curricular and extracurricular activities inside or outside the school, participation as a trainer or trainee of continuous activities, the accomplishment of distinct administrative tasks and the educational and curricular support to the students.

The version of the Teaching Career Statute approved by Decree-Law N. 15 of January 19, 2007 (Portugal, 2007) underwent several changes in 2010, due to the mobilization of Portuguese teachers against the division of the career in two categories and the requirement of the position of principal. Decree-Law N. 75, of June 23, 2010 (Portugal, 2010), revoked article 34, excluding the category of full teacher. However, it did not change article 35 and the activities of teachers remained overwhelming in relation to the administrative aspects of the school that requires a strong participation of the teachers in the processes of school evaluation.

Another complaint of the Portuguese teachers was the increase in the time allocated to school support activities for students. While until 2007 teachers could fulfill part of the non-teaching component outside the school premises, as of the 2007 Statute version, teachers needed to fulfill a weekly workload of the non-teaching component within the institution itself. One of the main tasks of this component was the increase of the support to students, an activity that corresponds to the model of monitoring developed in some Brazilian schools. According to the statement of Teacher 8 of the Carlos Amarante school,

Thus, with the changes that have come to exist in our educational system, teachers are increasingly certified for the classroom, support in the library, support classes that are consecrated in our schedules, right? This didn't exist before, therefore, formerly it was almost exclusively school time and the rest we did at home, and now there is a series of supports.

According to the reports of the interviewees and the legislation developed over the last 27 years, we can say that in Portugal the teacher must also be versatile and flexible, considering that, since the 1990s, it is their responsibility "[...] to perform administrative tasks, to allow time for programming, to evaluate, to recycle, to guide students, to receive the parents, to organize various activities, to attend seminars and coordination, discipline or year meetings" (Ramos, 2009, p. 23-24).

Intensification of the Teaching Work

Besides flexibilization being usual in the teacher's work routine, another phenomenon that has increased in recent years is the intensification of their work, that is, the increase in the number of classes taught, number of groups, work periods, schools and, consequently, the increase in the number of students the teacher needs to attend daily.

For Del Pino, Vieira and Hypolito (2009), in addition to the work intensification triggering restrictions on the teacher's personal life, reducing their time of rest, leisure or socialization, their availability for the improvement of their studies and their work school decreases, as the overwork of the teacher reduces the time spent to discuss, create and carry out a collective school project with the other professionals of the school, since many experience the work intensification.

Kuenzer and Caldas (2009, p. 35) point out that the intensification of the teaching work interferes in such a way in the life of the professional, to the point of "[…] not even having time to go to the restroom, having a cup of coffee, even a total lack of time to keep up with their field of knowledge". According to the authors, two reasons that drive the work intensification are low salaries and the possibility, provided by legislation, for teachers to accumulate positions in two or more schools.

One of the legislations that allowed teachers to accumulate positions, increasing their number of classes, schools and work shifts was Constitutional Amendment 19, of June 4, 1998, which modified the regime on the principles and norms of Public Administration, admitting in its article 3 that the remunerated accumulation of public offices is prohibited, except when there is compatibility of schedules "a) of two teacher positions, b) of a teacher position with another one, technical or scientific, c) two exclusively medical positions" (Brasil, 1998, p. 1).

Thus, we understand that the Constitutional Amendment 19 was a foundation for the creation of Decree N. 59448, of August 19, 2013 (São Paulo, 2013), by the Governor of the state of São Paulo, Geraldo Alckmin, who authorized the accumulation of a total workload of teachers within the limit of 65 hours per week, in case the professional holds two positions or functions.

The following is a study carried out by the Union of Official Education Teachers of the State of São Paulo (APEOESP) in 2011, regarding the health of teachers who taught in the public network of São Paulo, highlighting three figures that expose, through the systematization of data, the number of weekly hours, the number of schools and the teachers' work shifts.

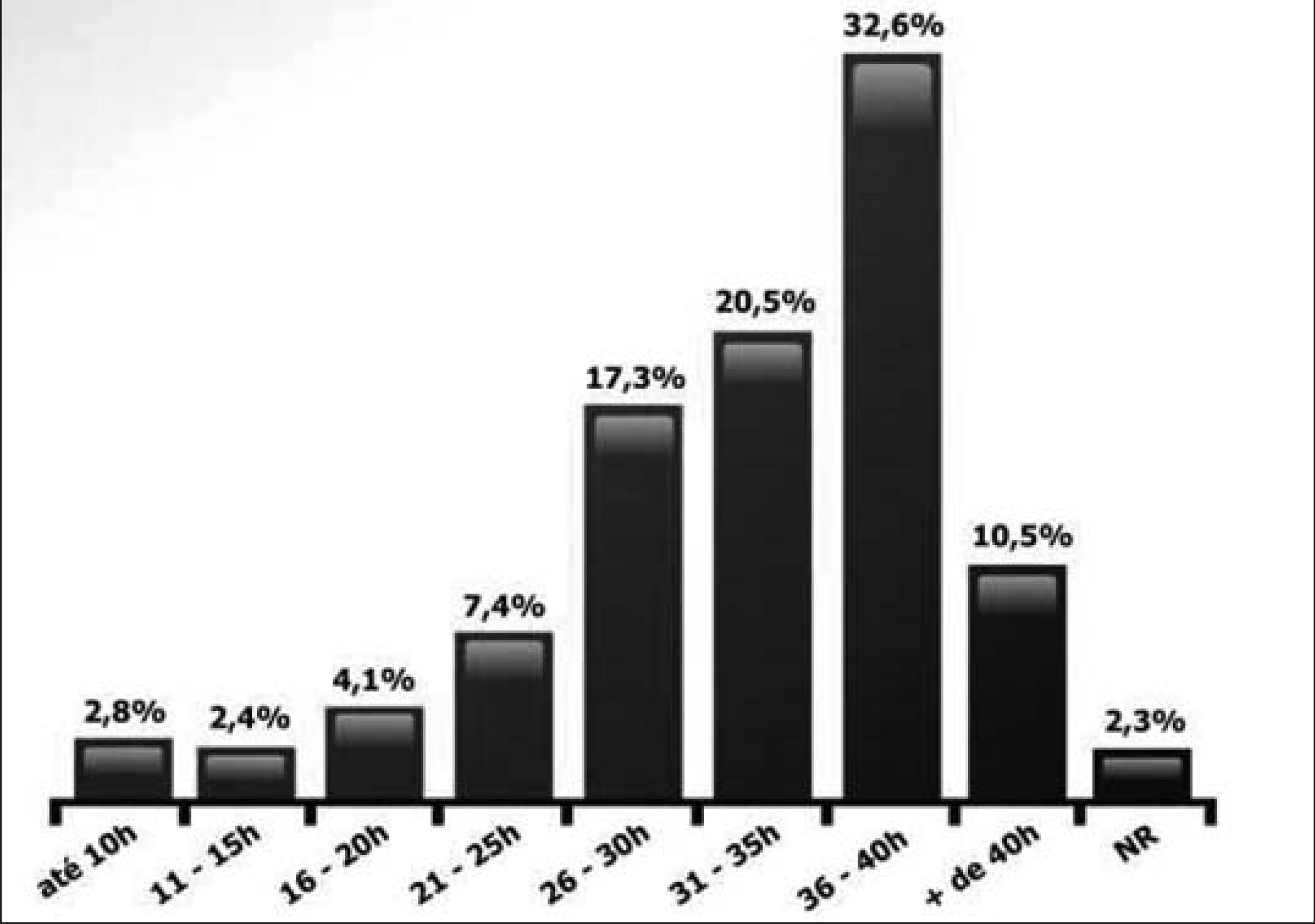

In Figure 1, regarding the number of hours of the teacher's weekly work, we observed that the highest percentage, 32.6%, was comprised by teachers who worked between 36 and 40 hours a week, that is, the maximum working hours allowed by Law 11738, dated July 16, 2008 (Brasil, 2008), which established the national professional minimum wage for those in the public K-12 education. However, although 10.5% of the teachers responded that they worked more than 40 hours a week, corroborating the condition of work intensification of these professionals, this research did not include the impact on the increase of teachers' working hours, after the approval of Decree N. 59448, of August 19, 2013 (São Paulo, 2013).

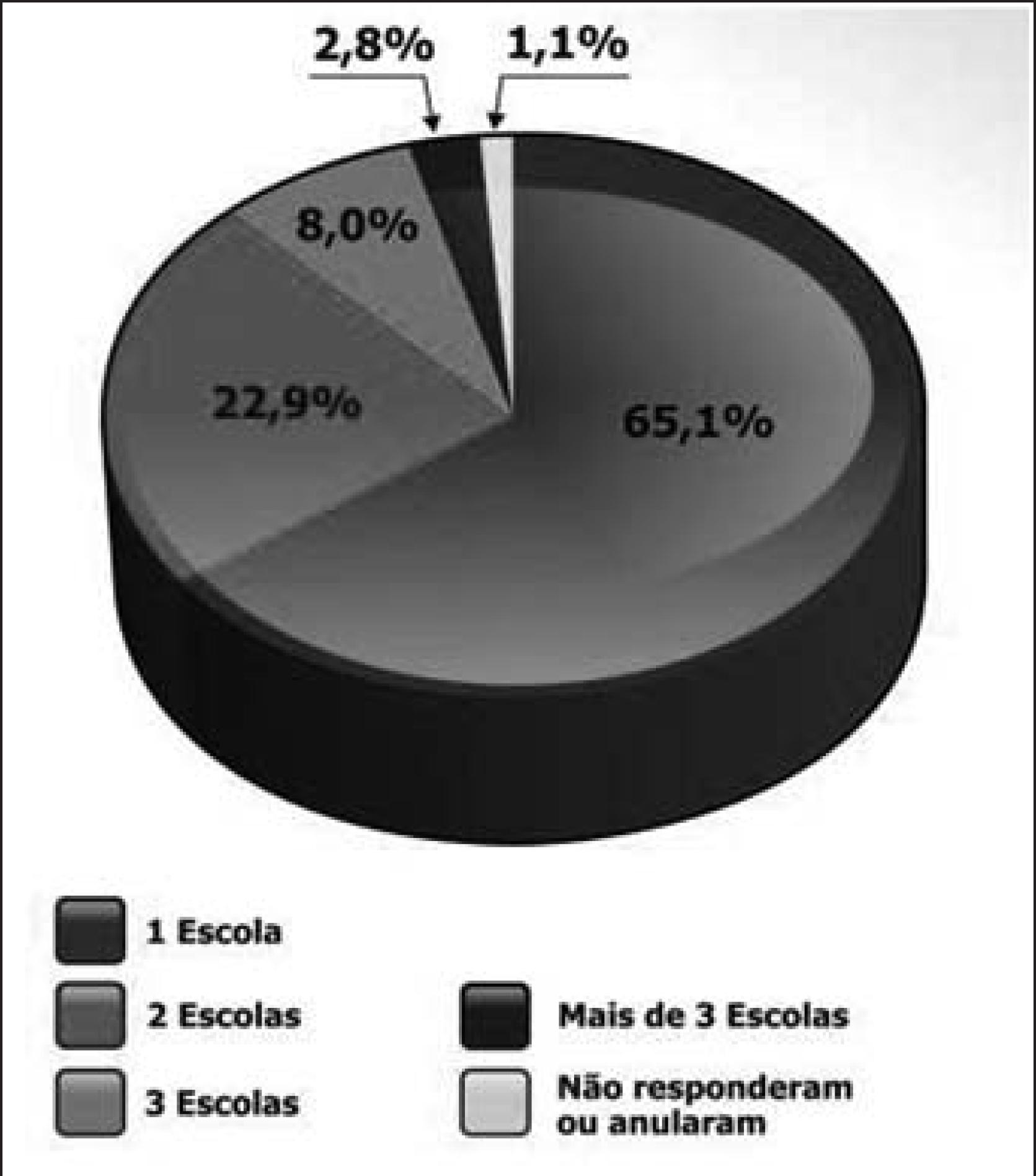

In Figure 2, we found that the majority of teachers, 65.1%, worked in only one school. However, 33.7% reported working in 2, 3 or more than 3 schools, which is considered a fairly high number.

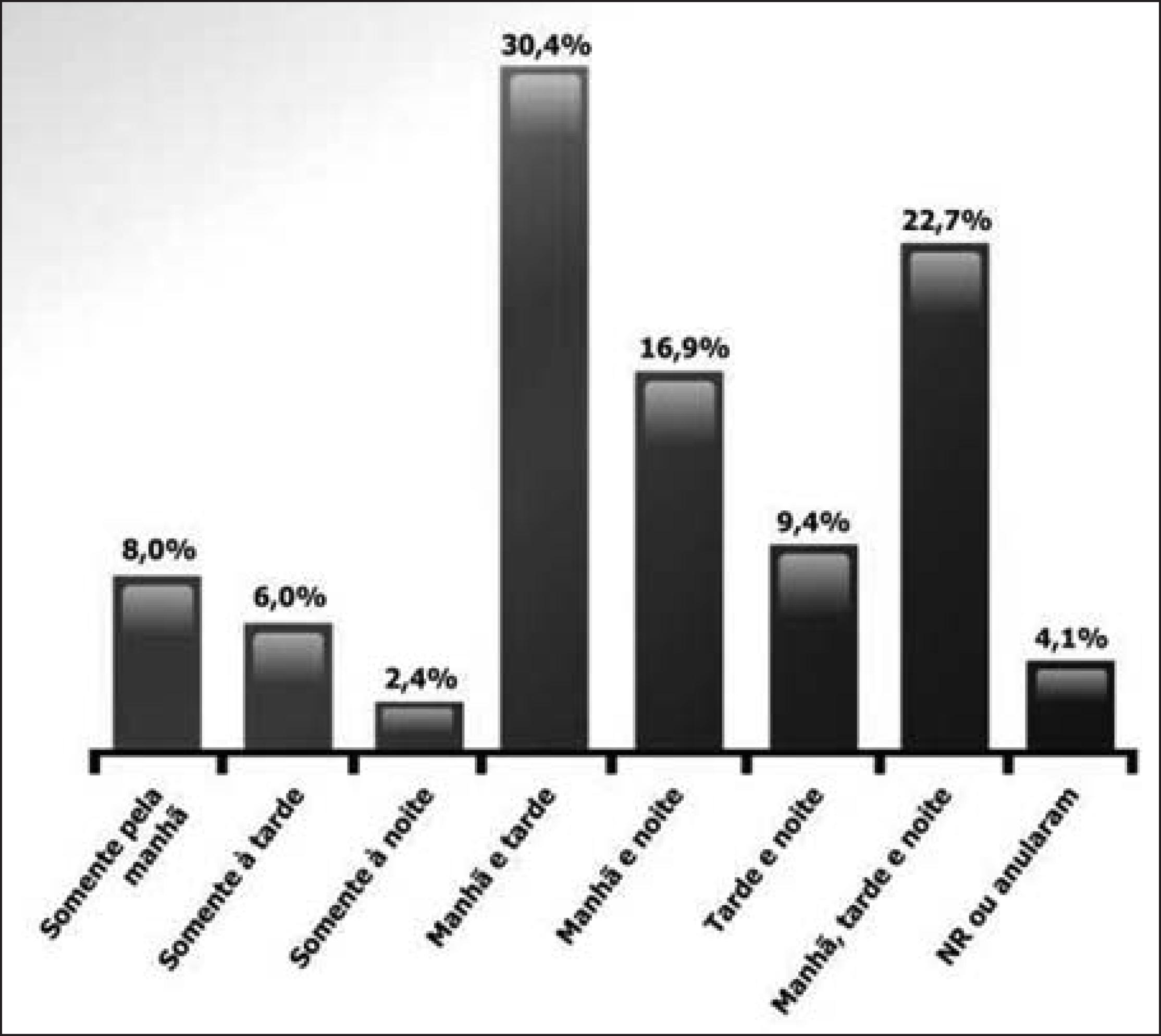

Regarding Figure 3, we observed that only 16.4% of teachers worked one shift throughout the day. Teachers who worked two shifts represented the majority, 56.7%, while 22.7% worked during the three shifts, morning, afternoon and evening. Thus, 79.4% of the teachers who responded to the research worked 2 or 3 shifts daily, leaving little or no free time to perform other activities, in addition to the time spent in the classroom.

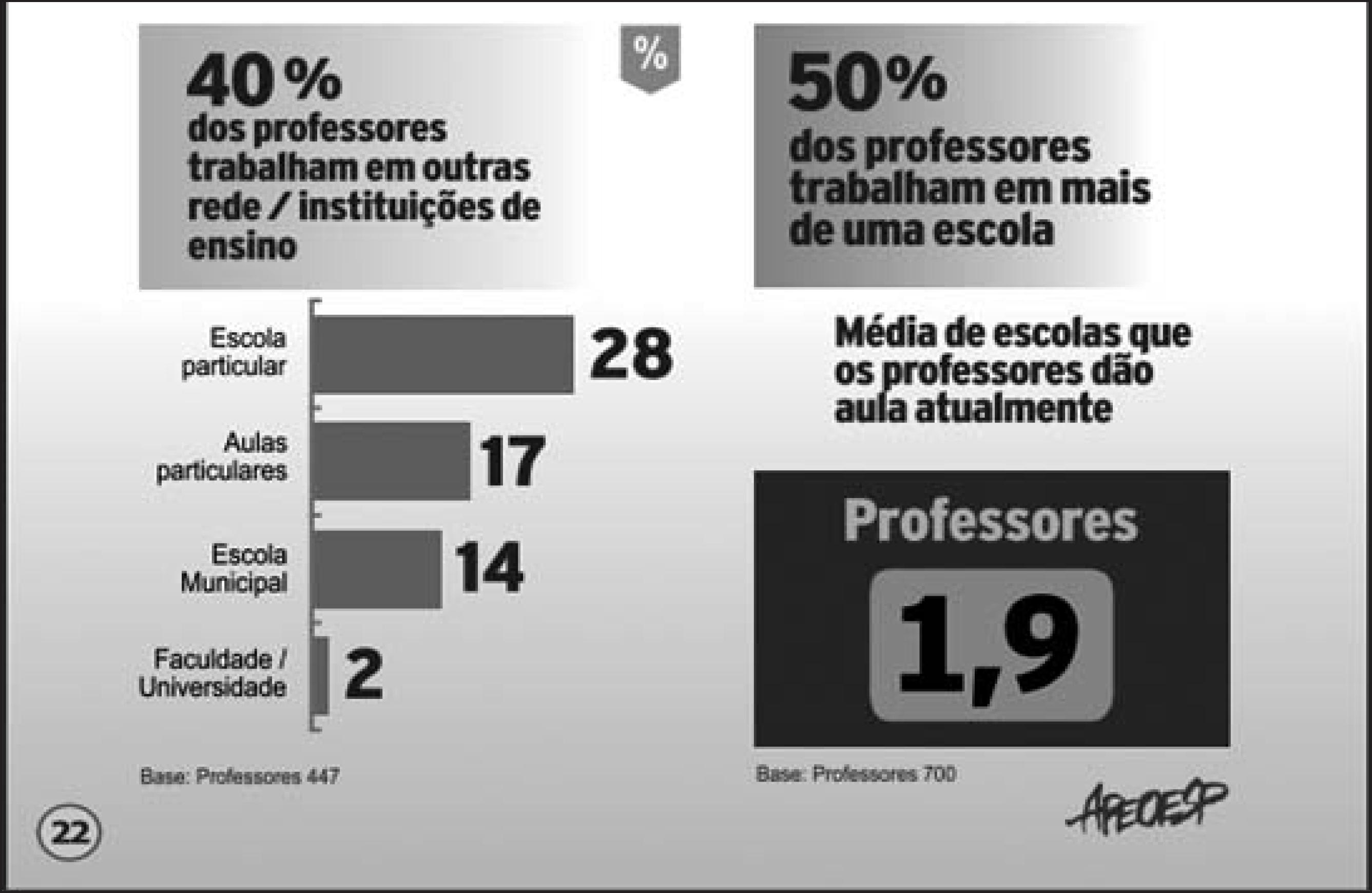

In the most recent Bulletin published by APEOESP in 2014, we can observe an increase in the percentage of teachers working in more than one school, reaching 50% of the group of teachers who participated in the study. This fact evidences the work intensification of these professionals, since in Figure 2, referring to APEOESP research conducted in 2011, the percentage of teachers working in more than 1 school corresponded to 33.7%.

From the 10 interviews we conducted at ETEC Antônio Devisate, only one teacher stated that his workday has not been intensified during the last 25 years. In contrast, Teacher 2 narrated her weekly work routine by accumulating 3 positions.

In order we can have a satisfactory income, which exceeds the needs of the family, in short, a decent income, one needs to work double. Actually, I have, if we see, I have 3 positions. I'm a teacher here at ETEC, coordinator of a course and I also hold a position in the state. In the state I teach in the middle school from Tuesday to Friday. Every morning here, from Tuesday to Friday in the middle school and I also teach, I teach in the Work Safety vocational course here on Tuesdays. I have to fulfill 15 hours of coordination here, plus 9 classes in high school and one in the evening, with two classes each, 22 with 15, 35, plus 20 in the state, 47, because there are ATPCs also where I need to participate in the state.

We can see that many teachers accumulate weekly workloads, schools and work shifts, as well as a large number of classes and students. According to APEOESP's research (2012, p. 50), "[...] to have a weekly workload of 40 classes, depending on the state or region, this teacher will have to take up six classes, that is, a total of 240 students".

Regarding the increase in the number of students per room, Teacher 7 of EE Maria Cecília reported that "[…] now the number of students has increased even more, because sometimes we can keep a certain number, but then we are obliged to receive up to 42 or 45, so it's not in all rooms, but the number of students has increased". It seems that the intensification of the work of teachers in the public network of São Paulo is inevitable, especially for those who teach in the final grades of elementary and high school.

In 2015, the head of the Department of Education, Herman Voorwald, announced a proposal for school reorganization with the closing of 94 schools throughout the state of São Paulo. Against the reform, thousands of teachers and students resisted and mobilized for more than six months occupying 213 schools across the state.

Although Governor Geraldo Alckmin suspended the reorganization project in December 2015, since the beginning of the 2016 school year the head of the Department of Education managed a silent school reorganization, causing overcrowding of classrooms, since, "Although the state schools of São Paulo have received 70 thousand more registrations this year than in 2015, Governor Geraldo Alckmin (PSDB) closed 2,800 classrooms throughout the state" (Oliveira, 2016, p. 1).

According to Barbosa (2011, p. 170), a problem of work intensification is the displacement of teachers among educational institutions, that is, the turnover and roaming of professionals in various work environments, which "[…] hinders the process of identification and involvement of the teacher with the school and the school community" and, in many cases,"[...] makes it impossible to carry out collective work among the teachers of the school, since it is not even possible to find common time for all the teachers to meet".

Although Law N. 11738 of July 16, 2008 (Brasil, 2008) was created, which established the workload of 40 hours per week, with 2/3 of the workload allocated to interaction with students , according to APEOESP (2011), the time spent in extra-class activities is not enough to reduce the intensity of work, since in 1/3 of their workload, teachers need to carry out their studies, prepare classes, grade papers, evaluate, etc.

In Portugal, the early indications of the intensification of teaching work were observed in the 1980s. In the 1988 Ministry of Education research, it was found that the teachers who worked the most were from poor families and beginners, an aggravating factor in view of the little experience of these professionals. In this research it was also revealed in which stage of teaching the work of the teacher was more intense.

The teachers with the highest teaching load per week are, in particular, the youngest, at the beginning of their careers (44.5% up to 25 years old and 43.1 from 26-35 years old) [...] above all from the end grades of the education system (36.2% from the unified and 35.9% from the secondary), and the lowest family income stratum (44.7%) (Commission Report, 1988, p. 1229).

In addition to secondary school teachers, teachers of the 2nd and 3rd cycles of (unified) K-12 education were overloaded by the number of classes, so that "Most post-primary teachers (47.5%) teach 4-6 classes. But there are still 28% who teach only 3 classes and 23.9% who already do it to more than 6 classes" (Relatório da Comissão, 1988, p. 1230). According to the percentages, we can observe that the number of teachers who taught in up to 3 classes was low, predominating the percentage of teachers who taught in 4, 6 or more classes, totaling 71.4%.

The increase in the number of classes, students, teaching hours or working hours was fundamental to guarantee a lower expense with the hiring of teachers. Intensification was one of the pillars of the management model implemented in the Portuguese schools, as well as in the public sector in general. This form of management aims to control and rationalize the tasks performed by the staff, guaranteeing their effectiveness by distributing a larger amount of work to a smaller number of teachers, rationalizing the expenses.

According to Santos (2010, p. 85), the work intensification in Portugal is a consequence of a new management model adopted by the Ministry of Education in the 1990s, with the aim of "[...] adjusting to organizational patterns and management of the work of flexible new enterprises, allowing the penetration of the capitalist logic in the educational structure, which inevitably falls on the work of the teacher".

Santos (2010) claims that the work intensification has led to the disqualification of teachers, because, in addition to the problems associated with the fragility of their performance as a professional, there is a collective problem in the relationship between teachers in schools, given the restricted availability to meetings or the implementation of school programs.

In the interviews with teachers of Alberto Sampaio and Carlos Amarante schools, the main complaints regarding the intensification of teaching work were: the increase in the number of classes and of students per class. For Teacher 8 of the Alberto Sampaio school, "The number of students [has increased], the rooms are larger. By chance, I teach here only, but there are cases of colleagues who teach in other schools, it's part of the grouping". According to Teacher 3 of the Carlos Amarante school,

The number of students has increased, the classes are larger, which is a negative thing. We would need smaller classes to work better and more individually, and we also have more difficult classes in that they have more students. Before we didn't have special needs students in the usual classes, and today we have them.

Teacher 2 from the Alberto Sampaio school confirmed the increase in the number of classes and students, however, he said that beginning teachers are the most disadvantaged, since "[...] sometimes the younger staff has annual contracts, and often the classes are not enough, and they work in 2 or 3 schools, which is extremely difficult". According to the teachers interviewed, the increase in the number of students per room was a consequence of a rule that only authorized the opening of classes with at least 30 students. However, during the school year students, may be transferred, increasing or reducing classes.

Reforms in educational legislation, especially in the Statute of the Career of Childhood Educators and Basic and Secondary Education Teachers, were fundamental for the intensification of teaching work in Portugal. Although the teachers' weekly workload is 35 hours per week, the Ministry of Education has changed the length of time of the teaching component and, consequently, of the non-teaching as well.

In article 77 of the 1990 Statute, "The teaching component of the 2nd and 3rd elementary school teachers are 22 hours per week" (Portugal, 1990, p. 23) and "The teaching component of the teaching staff of the secondary education, provided that it is fully provided at this level of education, is 20 hours per week" (Portugal, 1990, p. 23). In the 2007 Statute, the teaching component of the two stages of education was matched, discriminating in Article 77 that "The teaching component of teaching staff in other cycles and levels of education, including special education, is twenty-two hours per week" (Portugal, 2007, p. 514).

Another change related to the teachers' working day was the change of article 78 in which "The teacher is prohibited from providing more than five consecutive teaching hours per day" (Portugal, 1990, p. 23) for the new wording in the 2007 Statute in which "it is not allowed to assign to the teacher more than six consecutive teaching hours" (Portugal, 2007, p. 514), approving the increase of one hour per day.

Still in relation to the number of classes, since the first Statute of the Teaching Career of 1990, it was developed a calculation to reduce the teaching component of those teachers with higher accumulated service time. The proposal, under Article 79, was to reduce the time of the teaching component and increase the time of the non-teaching component.

The mandatory teaching component of teachers in the 2nd and 3rd cycles of basic education and those in secondary education and special education is successively reduced from two hours every five years to a maximum of eight hours, as soon as the professionals reach 40 years of age and 10 years of teaching service, 45 years of age and 15 years of teaching service, 50 years of age and 20 years of teaching service and 55 years of age and 21 years of teaching service (Portugal, 1990, p. 514).

However, in the 2007 Career Statute, in addition to increasing the minimum age for teachers to be entitled to reduction of the teaching component, the minimum time of professional service was extended. Thus, we understand that by delaying the right to reduction of the teaching component, the intention of the Ministry of Education was to optimize the work of teachers, aiming to maintain the largest number of classes distributed to each teacher, and it is therefore necessary to reduce the rights inherent in the reduction of the teaching component.

Article 79

1- The mandatory teaching component of the weekly work of the teachers of the 2nd and 3rd cycles of basic education, secondary education and special education is reduced, to the limit of eight hours, in the following terms:

Two hours as soon as the teachers reach 50 years of age and 15 years of teaching service;

Additional two hours as soon as the teachers reach 55 years of age and 20 years of teaching service;

Additional four hours as soon as teachers reach 60 years of age and 25 years of teaching service (Portugal, 2007, p. 514).

Besides extending the working time and the minimum age for reduction of the teaching component, other rights of Portuguese teachers have also changed. The two main ones were the reduction of the number of absences allowed each year for teachers, and the limit on the number of waivers allowed for teachers to carry out the ongoing training activities.

Another factor of intensification of the teaching work was the increase in the number of classes and groups distributed by teachers, from the creation of Decree-Law 18, of February 2, 2011, that changed the class time. The class time in the 2nd and 3rd cycles of basic and secondary education was 50 minutes, corresponding to the teaching component of 22 hours of work per week, or 1,100 minutes. However, Article 5 of Decree-Law 18 allowed schools "to organize the weekly workload of all components of the curricular discipline areas of the 2nd and 3rd cycles in periods of 45 or 90 minutes" (Portugal, 2011, p. 660).

Thus, the compulsory 1,100 weekly minutes were divided into 45-minute classes, increasing from 22 to 24 lessons per teacher. Thus, teachers had to increase the number of classes and, consequently, the number of students or schools, since some teachers needed to teach in other schools to reach the required number of classes.

We can see that in the last 27 years the reforms carried out by the Ministry of Education in the Teaching Career Statutes have increased the number of classes, groups and students per room and shortened the time of reduction of the teaching component of the oldest teachers, ratifying the phenomenon of intensification of teaching work that "creates a chronic burden of work, reduces the quality of work, destroys sociability" (Santos, 2010, p. 85).

It is about using the legal apparatus to ensure that changes in the Career Statutes would tailor the human resources of the education sector in line with the new rules of effective, efficient and optimized management of work productivity.

Conclusion

Although Brazil, the state of São Paulo and Portugal have distinct socioeconomic, political and institutional realities, we can verify that there is a convergence between the two countries in relation to the phenomenon of the precariousness of teaching work.

Over the last three decades, state administrative reform in these countries has altered the educational legislation in accordance with the requirements of control, policy monitoring, effectiveness and efficiency, based on "[...] neo-scientific and managerialist inspiration, arising centered on evaluation and management quality, modernization and rationalization, accountability to stakeholders, competitiveness among schools and the creation of internal markets among them" (Lima, 2012, p. 150).

In the state of São Paulo and in Portugal, several legislations that were developed in the last 30 years have boosted the flexibility and intensification of teaching work, as well as reducing labor and social rights of these professionals. The similarity in the precariousness of the teaching work in Brazil and Portugal occurred, except for the peculiarities in each country, due to the adherence to the neoliberal State model, whose objective is to reduce the cost of public services, including health, education and social security, the reduction of labor rights and the increase of private enterprise to occupy the lack of public sector offer.

However, it is important to highlight the resistance of the teaching category against the offensive of work precariousness. The Union of Official Education Teachers of the State of São Paulo (APEOESP) and the National Federation of Teachers (FENPROF), in Portugal, have held several demonstrations and strikes in the last 30 years in order to curb the precariousness of teaching and defend the rights of the category.

Although wage claims by unions are legitimate and permanent, in view of the historically low wages paid to education professionals and the freezing of their salaries, in recent years teachers have carried out extensive campaigns against work flexibilization and intensification.

In April 2017, for instance, FENPROF (2017) carried out a survey with teachers who teach in the 2nd and 3rd cycles of basic education and in secondary education questioning the daily and weekly working hours of Portuguese teachers. While in the public sector the employees work 7 hours a day and 35 hours a week, teachers said they work between 9 and 10 hours a day, around 46 hours a week.

Therefore, one of the biggest problems of the teaching profession in the last three decades is the excess of work and lack of time to dedicate to improving in the profession. Time is scarce for the teacher who teaches in 2 or 3 schools, who has 6 classes, more than 200 students and works in 3 shifts daily. The time for work and the time that the teachers dedicate to their private life are so intertwined that the professionals work during their lunch hour, dinner, at dawn, holidays and weekends.

In this way, it is pertinent that the teaching category and the São Paulo and Portugal unions continue their campaigns to reduce the working day, since teachers need time to study, to prepare their classes, to carry out continuous training, to reflect on their practice, participate in cultural events or simply to have free time for rest and leisure.

The work flexibilization was one of the factors that led to increased stress, physical and emotional exhaustion of teachers in Brazil and Portugal, since this professional does not only perform the activities that are inherent in their function, that is, planning classes, teaching, preparing and correcting tests and assignments. In their profession, a continuous action is required to deal with the administrative, management, raising funds for maintenance of schools, and interpersonal relationship with other co-workers, parents and the community at large.

The consequences of the work intensification do not only affect the physical and mental health of these professionals, but the quality of their work itself, since "[...] the intensification concerns not only the expansion and the accumulation of time constraints during the performance of the work, but also to the transformations impinged on the quality of the service, of the product" (Assunção; Oliveira, 2009, p. 354).

The precariousness of teaching work is part of a project to dismantle public education that was expanded by the rulers of the state of São Paulo and of Portugal in order to expand the private market for education. The main consequences of this project have been the weakening of the teachers' career and, consequently, the lowering of the quality of the public school, which is mainly aimed at the training of young people and children from the working class.

Referências

ALVES, Giovanni. Dimensões da Reestruturação Produtiva: ensaios da sociologia do trabalho. Londrina: Práxis, 2007. [ Links ]

ANTUNES, Ricardo. Século XXI: nova era da precarização estrutural do trabalho? In: ANTUNES, Ricardo; BRAGA, Ruy (Org.). Infoproletários: degradação real do trabalho virtual. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2009. P. 231-250. [ Links ]

APEOESP. Conversas sobre a Carreira: caderno 1. São Paulo: CEPES, 2012. Disponível em: <http://www.apeoesp.org.br/publicacoes/carreira-do-magisterio/conversas-sobre-a-carreira-do-magisterio/>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

APEOESP. Qualidade da Educação nas Escolas estaduais de São Paulo. São Paulo: CEPES, 2014. Disponível em: <http://www.apeoesp.org.br/d/sistema/publicacoes/667/arquivo/cad-quali-apeoesp2014-web.pdf>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

APEOESP. Saúde dos Professores e a Qualidade do Ensino. São Paulo: CEPES, 2011. Disponível em: <http://www.apeoesp.org.br/publicacoes/saude-dos-professores/saude-dos-professores-e-a-qualidade-do-ensino/>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

ASSUNÇÃO, Ada Ávila; OLIVEIRA, Dalila Andrade. Intensificação do Trabalho e Saúde dos Professores. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 30, n. 107, p. 349-372, maio/ago. 2009. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/pdf/es/v30n107/03.pdf>. Acesso em: l0 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, Andreza. Os Salários dos Professores Brasileiros: implicações para o trabalho docente. 2011. 208 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação Escolar) - Faculdade de Ciências e Letras, Campus de Araraquara, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Araraquara, 2011. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei Darcy Ribeiro (1996). Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional: lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 1996. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L9394.htm>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Emenda Constitucional nº 19, de 04 de junho de 1998. Modifica o regime e dispõe sobre princípios e normas da Administração Pública, servidores e agentes políticos, controle de despesas e finanças públicas e custeio de atividades a cargo do Distrito Federal, e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, Seção 1, p. 1, 1998. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/Emendas/Emc/emc19.htm>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 11.738, de 16 de julho de 2008. Regulamenta a alínea "e" do inciso III do caput do art. 60 do Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias, para instituir o piso salarial profissional nacional para os profissionais do magistério público da educação básica. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, Seção 1, p. 1, 2008. Disponível em: <http://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/lei/2008/lei-11738-16-julho-2008-578202-norma-pl.html>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

DEL PINO, Mauro Augusto Burket; VIEIRA, Jarbas Santos; HYPOLITO, Álvaro Moreira. Trabalho Docente, Controle e Intensificação: câmeras, novo gerencialismo e práticas de governo. In: FIDALGO, Fernando; OLIVEIRA, Maria Auxiliadora Monteiro; FIDALGO, Nara Luciene Rocha (Orgs.). A Intensificação do Trabalho Docente: tecnologias e produtividade. Campinas: Papirus, 2009. P. 113-134. [ Links ]

FENPROF. 94 Por Cento! A Maior Greve de Sempre dos Professores Portugueses! FENPROF. Lisboa. 03 dez. 2008. Disponível em: <https://www.fenprof.pt/?aba=27&mid=115&cat=95&doc=3838>. Acesso em 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

FENPROF. Professores Trabalham, em Média, Mais de 46 Horas/Semana. Lisboa: FENPROF, 2017. Disponível em: <https://www.fenprof.pt/?aba=27&mid=115&cat=95&doc=10819>. Acesso em 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

INFORSATO, Edson Carmo. As Dificuldades e Dilemas do Professor Iniciante. In: SOARES, Jane Almeida (Org.). Estudos sobre a Profissão Docente. São Paulo: Cultura Acadêmica Editora, 2001. P. 91-115. [ Links ]

KUENZER, Acácia Zeneida; CALDAS, Andrea. Trabalho Docente: comprometimento e desistência. In: FIDALGO, Fernando; OLIVEIRA, Maria Auxiliadora Monteiro; FIDALGO, Nara Luciene Rocha (Orgs.). A Intensificação do Trabalho Docente: tecnologias e produtividade. Campinas: Papirus, 2009. P. 19-48. [ Links ]

LIMA, Licínio Carlos. Elementos da hiperburocratização da administração educacional. In: LUCENA, Carlos; SILVA JUNIOR, João Reis. Trabalho e Educação no Século XXI: experiências organizacionais. São Paulo: Xamã, 2012. P. 129-158. [ Links ]

MACHADO, João; FORMOSINHO, Joaquim. Desempenho, Mérito e Desenvolvimento: para uma avaliação mais profissional dos professores. Revista ELO 16, Guimarães, p. 237-306, maio 2009. Disponível em: <http://www.cffh.pt/userfiles/files/ELO%2016.pdf>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Aparecida. Governo Alckmin fecha 2.800 salas de aula, apesar do aumento de 70 mil matrículas. Rede Brasil Atual, São Paulo, p. 01, 07 abr. 2016. Disponível em: <http://www.redebrasilatual.com.br/educacao/2016/04/governo-alckmin-fecha-2800-salas-apesar-do-aumento-de-60-mil-matriculas-915.html>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Dalila Andrade. A Reestruturação do Trabalho Docente: precarização e flexibilização. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 25, n. 89, p. 1127-1144, set./dez. 2004. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/pdf/es/v25n89/22614>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Dalila Andrade et al. Transformações na Organização do Processo de Trabalho Docente e o Sofrimento do Professor. Belo Horizonte: Rede Estrado, 2012. Disponível em: <http://www.redeestrado.org/web/archivos/publicaciones/10.pdf>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

PINTO, Alexandra Marques. Burnout Profissional em Professores Portugueses: representação social, incidência e preditores. 2000. 504f. Tese (Doutorado em Psicologia) - Faculdade de Psicologia e Ciências da Educação, Universidade de Lisboa. Lisboa, 2000. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Decreto-Lei nº 139-A, de 28 de abril de 1990. Diário da República, Lisboa, n. 98, Série I, 1990. Disponível em: <http://www.dgeste.mec.pt/index.php/2013/09/estatuto-da-carreira-docente/>. Acesso em 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Decreto-Lei nº 15, 19 de janeiro de 2007. Diário da República, Lisboa, n. 14, Série I, 2007. Disponível em: <http://www.aeps.pt/cfps/Decreto_Lei15_2007.pdf>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Decreto-Lei nº 75, 23 de junho de 2010. Diário da República, Lisboa, n. 14, Série I, 2010. Disponível em: <http://www.uc.pt/feuc/eea/Documentos/ECD>. Acesso em: 03 jul. 2016. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Decreto-Lei nº 18, 02 de fevereiro de 2011. Diário da República, Lisboa, n. 23, Série I, 2011. Disponível em: <http://www.idesporto.pt/ficheiros/file/DL_18_2011.pdf>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

RAMOS, Susana Isabel Vicente. (In) Satisfação e Stress Docente. Coimbra: Estudo Geral, 2009. Disponível em: <https://estudogeral.sib.uc.pt/jspui/bitstream/10316/8522/1/Bem%20estar%20e%20mal%20estar%20docente.pdf>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

RELATÓRIO DA COMISSÃO. A Situação do Professor em Portugal. Análise Social, Lisboa, v. XXIV, n. 103-104, p. 1187-1293, abr./maio 1988. Disponível em: <http://analisesocial.ics.ul.pt/documentos/1223032742E9hPK9ju2Hw89SX2.pdf>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Aparecida Fátima Tiradentes. Pedagogia do Mercado: neoliberalismo, trabalho e educação no século XXI. Rio de Janeiro, Ibis Libris, 2012. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Maria Olímpia Rodrigues. Professores Titulares e (outros) Professores. Profissão, trabalho e relações entre docentes: breve ensaio sobre um processo de mudança. 2010. 252 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciências da Educação) - Universidade do Minho, Braga, 2010. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO. Decreto nº 59.448, de 19 de agosto de 2013. Altera e acrescenta dispositivos ao Decreto nº 55.078, de 25 de novembro de 2009, que dispõe sobre as jornadas de trabalho do pessoal docente do Quadro do Magistério e dá providências correlatas. Diário Oficial do Estado, São Paulo, Seção I, p. 1, 2013. Disponível em: <www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto/2013/decreto-5944819.08.2013.html>. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

Received: March 21, 2018; Accepted: July 28, 2018

texto en

texto en