1 Introduction

The assessment process of Higher Education Institutions (HEI) and Post Graduate Courses (PGC) is a fundamental mechanism that generates indicators for both control bodies and course coordinators to optimise their practices to offer high-performance professionals to the academia or the job market, as well as diagnose the aspects that must be improved. In this perspective, the qualification of PGCs becomes a decisive factor to enable the improvement of educational systems (Astakhova et al., 2016).

It is the universities’ responsibility to develop and encourage the employability of their students. In this perspective, universities must show society that they can train students with qualities useful to the job market through quality Education, in addition to citizen training (Caballero; Alvarez-González; López-Miguens, 2021; Leal, 2023). Among their purposes, Bispo and Costa (2016), add that stricto sensu graduate courses train high-level researchers in a given area, professionals capable of working in Higher-Education teaching, and high-performance professionals through professional master’s courses.

Aiming at a greater efficiency in the teaching and learning process of the graduate courses, and the qualification of the courses offered, their assessment is necessary. In Brazil, this process is done through the Brazilian graduate assessment system. Among other goals and based on established criteria, the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Capes) assesses existing courses and approves the proposal of new courses (Marques; Veiga; Borges, 2020). Capes has been undergoing constant updates encompassing technological, scientific and educational advances and included self-assessment as one of the evaluation criteria for graduate courses in 2018. Self-assessment is a way of self-knowledge of what happens in a course or institution, and allows an evaluation of the present situation of the course and the expectations. Such assessment also permits the evaluation of what has already been accomplished, how the administration takes place, what information is available for analysis and interpretation, and what the strengths and weaknesses of the institution are (Zainko; Pinto, 2008). Self-assessment favours the construction of identity, heterogeneity and involvement of the courses assessed, in addition to the minimum standards guaranteed by external assessment (CAPES, 2019). Also, Seifert and Feliks (2018) claim that self-assessment establishes what is being built, considering the teaching-learning process.

Meeting the CAPES assessment criteria, which include issues related to the dissertation and theses development process; course infrastructure; professors’ performance; curriculum structure, among others, this work aims to develop a Self-Assessment model of Graduate Courses from the student’s perspective.

The study presents an innovative bias for providing new evidence for the emerging literature on self-assessment applied to the graduate courses scenario, since the inclusion of this dimension in the Capes assessment system is recent and highlights a new aspect in the courses assessment field. It also innovates for being the pioneer on building a model that considers the aspects of self-assessment and for dealing with an empirical approach that can be replicated to different realities of the various graduate courses.

In addition, understanding the relationship between the different aspects of self-assessment and identifying the influencers in the assessment process and in the satisfaction of students and alumni is essential for graduate courses to achieve better results, as self-assessment provides relevant and updated information (Angst; Alves, 2018). Furthermore, the study can be useful to identify the central points to be addressed in institutional strategies aimed at improving graduate courses at HEI.

2 Model development

The development of a nation is directly related to the Education quality (Astakhova et al., 2016). Permanent assessment and continuous development of the educational context are necessary to meet social demands, measure quality and provide visibility to educational institutions. The assessment process with organised information favours the understanding of situations and relationships, the construction of meanings and knowledge about subjects, structures and activities that occur in an educational institution at a given time (Leite, 2008).

In Brazil, the assessment is carried out every four years, seeking to analyse and assess the permanence of the PGCs offer (CAPES, 2014). That evaluation contemplates three central dimensions. First, regarding the Program, the assessment seeks to check the operation, structure and planning of the Postgraduate Program (PPG) considering its characteristics and objectives. Second, the Educational Background considers the quality of the students, the performance of professors and the production of knowledge associated with the research and training activities of the program. Third the Impact on Society verifies the innovativeness of the intellectual production, internationalization, impact and social relevance of the program (BRASIL, 2019).

In the last reformulation, implemented for the 2017–2020 quadrennium, the self-assessment of the graduate course started to be recommended and assessed by Capes. Self-assessment is present in the “Course” query, specifically in the “The processes, procedures and results of the course self-assessment, focusing on student training and intellectual production” item (CAPES, 2018).

Self-assessment is characterised by a process of self-reflection and self-analysis that highlights strengths and challenges that remain, aiming to improve the quality of academic work, training concepts, development and learning. Self-assessment is planned, executed and explored by the individuals who are responsible for the actions being assessed. It also allows for reflections on the context and policies applied, as well as the organisation of data that result in decision-making (CAPES, 2019).

The self-assessment process must be broad both in its assessment dimensions and in the assumption of the participation of all those involved (Angst, 2017; Myalkina, 2019). When creating a model, one must consider the need to cover all the activities of academic institutions, teaching, research, extension and management in a coordinated way, as well as crediting and supporting the various interested parties for the information (Monticelli et al., 2021).

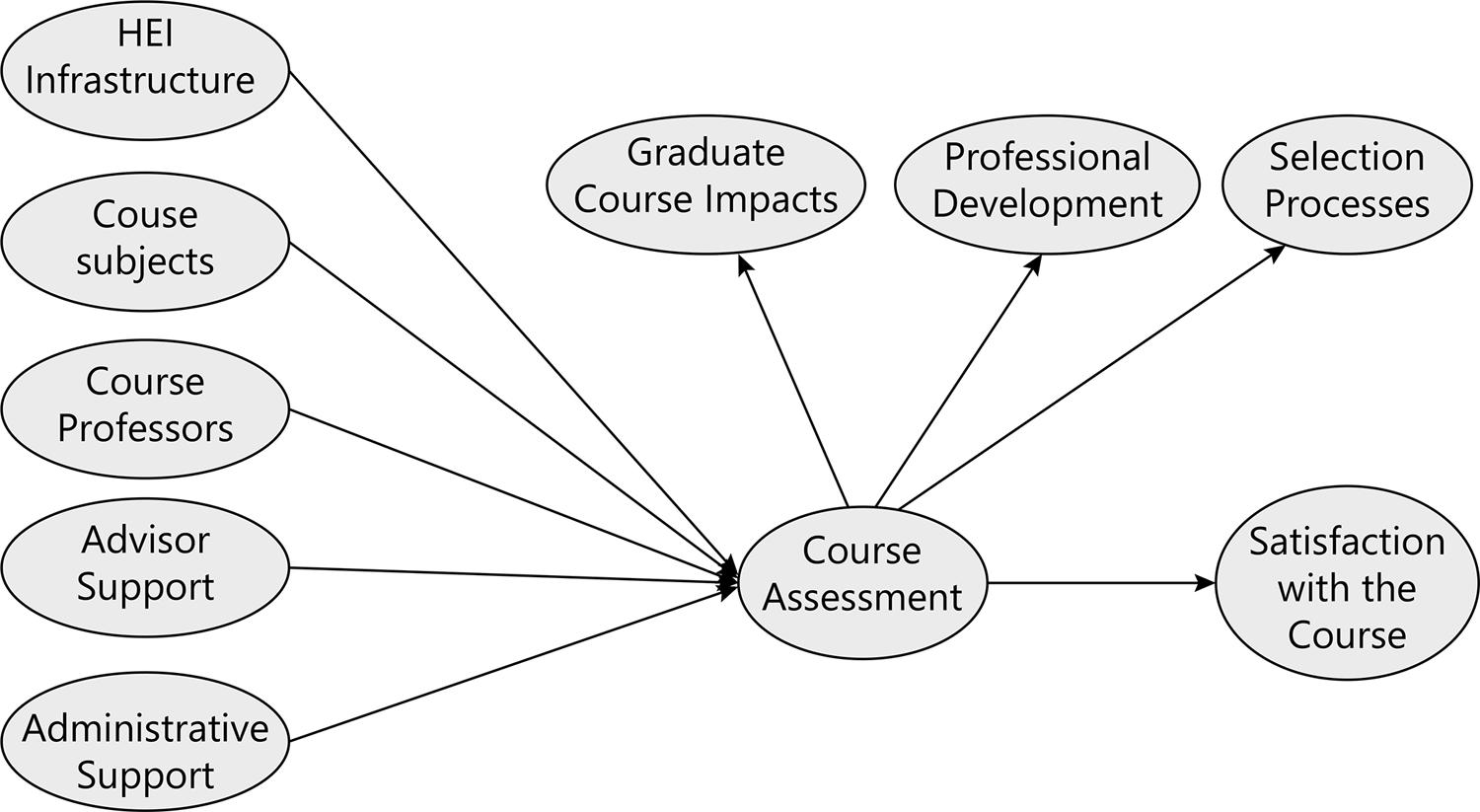

Therefore, considering the need to implement effective self-assessment systems to meet Capes’s requirements, the internal assessment systems of educational institutions, and the multidimensionality necessary for a self-assessment model, this study proposes a Student Self-Assessment model with seven main dimensions: “HEI Infrastructure”, “Course Subjects”, “Course Professors”, “Advisor Support”, “Administrative Support”, “Course Assessment” and “Satisfaction with the Course”, which are related as shown in Figure 1 .

The “course assessment” represents the graduate student’s self-assessment. This dimension is formed by three first-order constructs: the “Graduate Course Impacts”, “Professional Development” and “Selection Processes”. The “Graduate Course Impacts” dimension assesses the course performance in terms of teaching capacity, self-management and regional and national impacts, in addition to international performance. The “Professional Development” dimension analyses both the ability of the course to provide specific knowledge that effectively contributes to career development and to build researchers capable of producing nationally and internationally. On the other hand, the “Selection Process” dimension refers to the form, clarity and adequacy of the processes for selecting students and distributing scholarships (if any).

As determinants of the student’s self-assessment, five fundamental factors are considered: HEI Infrastructure, Course Subjects, Course Professors, Advisor Support, and Administrative Support. The first three factors are assessment parameters provided for in the assessment model of graduate courses used by Capes. The last two, which refer to the presence of support for students, are important support dimensions for the conclusion of a stricto sensu graduate course.

The “HEI Infrastructure” factor identifies the student’s perception of the adequacy of physical facilities, equipment, Internet access and security provided by the educational institution. The “Course Subjects” dimension comprehensively assesses the student’s perception of the adequacy of contents, bibliographies, activities developed, evaluation forms, and the quality of classes. In “Course Professors”, the student’s perception is sought both in terms of mastery of knowledge, teaching learning strategies and the form of service and access to the subject’s professors. In this sense, it is considered that in Higher Education, teaching-learning strategies generally require students to act more independently and proactively, with feedback being essential (Leal, 2023).

In the support-related dimensions, both the course secretariat and the advisors are assessed. For the secretariat, the focus is on the adequate provision of information, accessibility, courtesy, and willingness to help students. The insertion of the “Advisor Support” dimension is justified by the evidence that the advisor-student relationship has a relevant role in retaining students in courses, in addition to being important in the knowledge construction (Moore, 2017; Vieira et al. , 2022), since it helps students to fulfil their academic, personal and career goals (Martinez; Elue, 2020; Meurer et al ., 2020). In the student’s perception, the dimension identifies the various facets of the guidance process, ranging from issues related to knowledge sharing to issues of access and feedback from the advisor.

The last dimension of the model is “Satisfaction with the Graduate Course”, which is directly impacted by the course assessment. This dimension represents the student’s level of satisfaction with the course in a comprehensive way, considering the main assessment parameters of a course according to the Capes assessment system.

Therefore, the Student Self-Assessment model is multidimensional, with seven central dimensions and three constructs that form the course assessment dimension. Of the seven dimensions, five are considered assessment antecedents (“HEI Infrastructure”, “Course Subjects”, “Course Professors”, “Advisor Support”, “Administrative Support”), and “Satisfaction” is the consequent dimension, that is, the one that is directly impacted by the course assessment. Table 1 presents the set of items that measure each of the model dimensions and their respective scales.

Table 1 Items and scales of the student self-assessment model dimensions

| Dimension | Items | Scale | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HEI Infrastructure | 1 | Resources made available by UFSM libraries. | 1 = Inadequate 2 = Not suitable 3 = Adequate 4 = Very suitable 5 = Totally adequate |

| 2 | Infrastructure available at the Teaching Centres (or campuses outside the headquarters) for holding conferences and events. | ||

| 3 | Safety measures practised at the university. | ||

| 4 | The campus infrastructure. | ||

| 5 | The infrastructure used by the program. | ||

| 6 | The adequacy of the infrastructure used by the program for PNE (Persons with Special Needs). | ||

| 7 | The equipment available. | ||

| 8 | The labs available. | ||

| 9 | Internet access in the classrooms used by the program. | ||

| 10 | Internet access in common areas at the university. | ||

| 11 | Internet access in my workroom. | ||

| Course Professors | 12 | The professors are responsive. | 1 = I totally disagree 2 = I partially disagree 3 = I neither disagree nor agree 4 = I partially agree 5 = I totally agree |

| 13 | The professors are accessible. | ||

| 14 | The professors adopt good teaching practices. | ||

| 15 | The professors have specific knowledge that they add to my training. | ||

| 16 | The professors have general knowledge that adds to my training. | ||

| 17 | The professors have international academic contacts. | ||

| 18 | The professors publish in international journals. | ||

| Course Subjects | 19 | I can understand the concepts discussed in the subjects. | |

| 20 | I can apply the concepts discussed in the subjects. | ||

| 21 | I believe the classes are of good quality. | ||

| 22 | The subject’s activities are adequate. | ||

| 23 | The bibliography is predominantly based on international literature. | ||

| 24 | The bibliography is updated. | ||

| 25 | The use of writing articles as an assessing criterion is appropriate. | ||

| 26 | The assessment criteria are adequate. | ||

| 27 | I receive feedback from the activities I perform in the course. | ||

| 28 | Grading is consistent with my performance. | ||

| 29 | The recommended readings are appropriate to what is discussed in the classroom. | ||

| 30 | The amount of readings is adequate to what is discussed in the classroom. | ||

| 31 | The course workload is fulfilled. | ||

| 32 | The program content is fulfilled. | ||

| Advisor Support | 33 | My advisor has a good relationship with me. | |

| 34 | My advisor treats me respectfully. | ||

| 35 | My advisor is a good researcher. | ||

| 36 | My advisor is patient with me. | ||

| 37 | My advisor always assists me when I need it. | ||

| 38 | My advisor quickly returns the requests I submit. | ||

| 39 | My advisor is easily accessible. | ||

| 40 | My advisor encourages me to attend events. | ||

| 41 | My advisor helps me publish articles in national journals. | ||

| 42 | My advisor helps me publish articles in international journals. | ||

| 43 | My advisor helps me get international academic contacts. | ||

| 44 | My advisor places me in activities (meetings, presentations, projects, articles etc.). | ||

| 45 | My advisor masters the knowledge related to the subject of my dissertation/thesis. | ||

| 46 | My advisor masters the methodological procedures necessary for the development of my dissertation/thesis. | ||

| 47 | My advisor discusses my research with me regularly. | ||

| 48 | My advisor teaches me to find work that is relevant to the development of my work. | ||

| 49 | My advisor provides constructive feedback and guidance for my work. | ||

| 50 | My advisor is essential for the elaboration of my dissertation/thesis. | ||

| Administrative Support | 51 | The secretary is courteous. | |

| 52 | The secretary is always willing to help. | ||

| 53 | The secretary provides correct information. | ||

| 54 | The secretary is accessible during working hours. | ||

| 55 | The secretary answers my questions. | ||

| 56 | The secretary treats me respectfully. | ||

| 57 | The secretary updates me with academic proceedings. | ||

| Graduate Course Impacts | 58 | The teaching quality of the course is high. | |

| 59 | The international performance of the course is relevant. | ||

| 60 | The regional impact of the course is high. | ||

| 61 | The national impact of the course is high. | ||

| 62 | The course is properly coordinated. | ||

| 63 | The course has an efficient information system (website, emails, media). | ||

| Professional Development | 64 | My national academic production evolved from the learning acquired in the course. | |

| 65 | My international academic production evolved from the learning acquired in the course. | ||

| 66 | The course improved my specific knowledge in my field of expertise. | ||

| 67 | The completion of the course has been important for my professional career. | ||

| Selection Processes | 68 | The requirements for joining the program are clear. | |

| 69 | The selection process is fair. | ||

| 70 | The criteria for awarding scholarships are clear. | ||

| 71 | The curriculum structure of the course (research lines, subjects, credits) is adequate to the course goals. | ||

| Satisfaction with the Course | 72 | Course curriculum structure. | 0 (completely unsatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied) |

| 73 | Course faculty competencies. | ||

| 74 | Course internationalisation. | ||

| 75 | Regional impacts of the course. | ||

| 76 | Incentive to Academic Production. | ||

| 77 | Course Selection Criteria. | ||

| 78 | Career/labour market preparation. | ||

| 79 | Overall satisfaction with the advisor. | ||

| 80 | Overall satisfaction with the course. |

Source: Prepared by the authors (2022)

It is also noteworthy that internationalization, a challenge institutionalized both by national public policies and by institutional policies (Heinzle; Pereira, 2023), depends on different actors to be executed (Vázquez; Jiménez García, Canan, 2022). The internationalization creates new opportunities, hastens the implementation of innovative work methods, improves mutual understanding between peoples and cultures, and contributes to the Education of a new generation for work in the global labor Market (Akkari et al ., 2023) was incorporated into the model based on specific items in different dimensions. Questions related to social impact were also incorporated into the model, which are represented by activities with the potential to highlight the link and impact of programs with society, in a virtuous circle between practice, research and professional qualification (Ferraço; Farias, 2021).

3 Method

The present study is characterised as descriptive, carried out through a quantitative approach, from a survey-type research. According to Malhotra (2019), the survey method is based on an interrogation of the participants carried out through a structured questionnaire, with the purpose of eliciting specific information from the interviewees.

The research was carried out with regularly enrolled students and alumni (since 2017) of graduate courses at the Federal University of Santa Maria (UFSM), constituting the population of this study (4,544 students and 7,970 alumni). The entire population received an invitation email from the institution, which resulted in a sample of 2,037 respondents.

As a collection tool, a questionnaire with 85 questions was used and organised into seven blocks. In the first block (“Graduate Courses Infrastructure”), a five-point adequacy scale was used (1– Totally inadequate; 5 – Totally adequate). The other blocks addressed issues related to the professors’ academic and professional quality, the advisor’s relationship and accessibility, the support from the secretariat, the general assessment of the graduate course, and the satisfaction with the graduate course. To measure the responses of these blocks, a five-point Likert scale was used (1 – Totally disagree; 5 – Totally agree). Finally, the last block was intended to characterise the respondents’ profile and collect some general information, with questions about gender, age, marital status, relationship, performance and length of service in the graduate courses.

In the first phase of the quantitative stage, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was carried out to validate the proposed constructs using version 23 of the SPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). Internal consistency was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s Alpha. As the analysis is exploratory, values equal to or greater than 0,7 were considered acceptable (Hair Junior et al ., 2014). In the second phase of the quantitative stage, Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used in order to validate the first-order constructs: “HEI Infrastructure”, “Course Subjects”, “Course Professors”, “Advisor Support”, “Administrative Support”, “Satisfaction with the Graduate Course”, and the second-order construct “Course Assessment”. The models were estimated using the Amos Graphics software.

To validate the constructs, the statistical significance of the indices was analysed: Chi-square (χ 2 ), Chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Residual (RMR), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). For the chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio, the recommendations are for values less than five. For CFI and TLI, values greater than 0,950 are suggested, and the RMR and RMSEA should be below 0,080 and 0,060, respectively (Byrne; 2010; Hair Junior et al. , 2014; Hooper; Coughlan; Mullen; 2008; Kline; 2015).

As for the reliability measures, the coefficients of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Composite Reliability and Cronbach’s Alpha were considered. For the AVE, values equal to or greater than 0,5 are desirable (Fornell; Larcker, 1981), with values from 0,7 admitted for the Composite Reliability and Cronbach’s Alpha (Hair Junior et al. , 2014). Discriminant validity was assessed in the nine constructs, comparing the AVE and the correlations. For this, it was necessary to consider the premises (Fornell; Larcker, 1981), in which the correlation of all pairs of the model constructs was verified, comparing it with the square root of the AVE and the orientations of Bagozzi, Yi and Phillips (1991) through the Chi-square difference test. Finally, the estimation of the integrated model occurred through the SEM. In this step, the chi-square indices (χ 2 ), the Chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio, CFI, NFI, TLI, RMR and RMSEA were considered in the validation of the integrated model.

4 Results

In order to identify the self-assessment dimensions of the PGCs, and the satisfaction and general assessment of the courses, the EFA was applied, with the varimax rotation method and as an extraction criterion, eigenvalues greater than one were defined. Also, all initial variables showed a commonality greater than 0,5 and were maintained in the analysis. The exploratory factor results of the analyses are presented in Table 2 .

Table 2 Factor analysis results

| Variable | Factor loading | Variance | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 - HEI Infrastructure | |||

| Question 9 | 0,863 | 60,76 | 0,918 |

| Question 11 | 0,828 | ||

| Question 10 | 0,825 | ||

| Question 7 | 0,790 | ||

| Question 5 | 0,787 | ||

| Question 8 | 0,743 | ||

| Question 4 | 0,740 | ||

| Question 2 | 0,722 | ||

| Question 3 | 0,691 | ||

| Question 1 | 0,656 | ||

| Question 6 | 0,646 | ||

| Factor 2 – Course Subjects | |||

| Question 32 | 0,719 | 35,83 | 0,930 |

| Question 31 | 0,711 | ||

| Question 28 | 0,698 | 35,83 | 0,930 |

| Question 29 | 0,685 | ||

| Question 30 | 0,671 | ||

| Question 22 | 0,671 | ||

| Question 26 | 0,669 | ||

| Question 21 | 0,639 | ||

| Question 27 | 0,628 | ||

| Question 19 | 0,612 | ||

| Question 20 | 0,596 | ||

| Question 25 | 0,584 | ||

| Question 23 | 0,558 | ||

| Question 24 | 0,550 | ||

| Factor 3 – Course Professors | |||

| Question 16 | 0,762 | 31,35 | 0,901 |

| Question 15 | 0,735 | ||

| Question 12 | 0,720 | ||

| Question 13 | 0,702 | ||

| Question 14 | 0,696 | ||

| Question 18 | 0,676 | ||

| Question 17 | 0,617 | ||

| Factor 4 – Advisor Support | |||

| Question 42 | 0,818 | 26,83 | 0,955 |

| Question 43 | 0,795 | ||

| Question 41 | 0,784 | ||

| Question 47 | 0,780 | ||

| Question 48 | 0,778 | ||

| Question 50 | 0,760 | ||

| Question 49 | 0,749 | ||

| Question 44 | 0,732 | ||

| Question 40 | 0,698 | ||

| Question 45 | 0,694 | ||

| Question 46 | 0,668 | 26,83 | 0,955 |

| Question 38 | 0,609 | ||

| Question 35 | 0,567 | ||

| Factor 5 – Administrative Support | |||

| Question 55 | 0,924 | 21,47 | 0,958 |

| Question 52 | 0,923 | ||

| Question 54 | 0,890 | ||

| Question 51 | 0,887 | ||

| Question 53 | 0,870 | ||

| Question 56 | 0,854 | ||

| Question 57 | 0,820 | ||

| Factor 6 – Graduate Course Impacts | |||

| Question 69 | 0,846 | 23,93 | 0,879 |

| Question 68 | 0,787 | ||

| Question 67 | 0,729 | ||

| Question 70 | 0,606 | ||

| Question 61 | 0,599 | ||

| Question 71 | 0,531 | ||

| Factor 7 – Professional Development | |||

| Question 62 | 0,762 | 20,59 | 0,775 |

| Question 64 | 0,759 | ||

| Question 65 | 0,700 | ||

| Question 63 | 0,683 | ||

| Factor 8 – Selection Processes | |||

| Question 59 | 0,835 | 20,1 | 0,777 |

| Question 58 | 0,811 | ||

| Question 60 | 0,686 | ||

| Question 66 | 0,405 | ||

| Factor 9 – Satisfaction with the Course | |||

| Question 80 | 0,861 | 62,87 | 0,918 |

| Question 73 | 0,854 | ||

| Question 78 | 0,827 | ||

| Question 76 | 0,811 | ||

| Question 72 | 0,808 | ||

| Question 75 | 0,802 | ||

| Question 77 | 0,767 | ||

| Question 74 | 0,765 | ||

| Question 79 | 0,591 | ||

Source: Prepared by the authors (2022)

Bartlett’s test rejected the null hypothesis that the data matrix is an identity matrix for all dimensions, indicating the data factorability. The factor loadings of the variables range from 0,405 to 0,924, demonstrating that some variables have a greater contribution to the item’s formation. Cronbach’s alphas are adequate, as they all resulted above 0,7. Therefore, the EFA confirms the dimensions predicted in the theoretical model and their respective items.

4.1 Validation of constructs

In order to validate the first-order constructs, the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was applied for individual validation of each of the nine constructs. Then, in order to confirm whether the models are adequate, the fit indices were analysed, which are presented in Table 3 .

Table 3 Adjustment indices of first-order constructs

| Indices | Limits | HEI Infrastructure | Course Subjects | Course Professors | Advisor Support | Administrative Support | Graduate Course Impacts | Professional Development | Selection Processes | Satisfaction with the Course | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| IM | FM | IM | FM | IM | FM | IM | FM | IM | FM | IM | FM | IM | FM | IM | FM | IM | FM | ||

| X 2 (value) | - | 2297,456 | 79,003 | 3162,662 | 254,244 | 629,026 | 37,603 | 757,859 | 194,880 | 1088,604 | 17,106 | 702,589 | 702,589 | 230,900 | 0,007 | 5,261 | 544,394 | 72,602 | |

| DF/X 2 | - | 52,215 | 4,158 | 41,074 | 4,889 | 116,359 | 4,178 | 42,429 | 4,753 | 77,757 | 2,138 | 78,065 | 78,065 | 115,450 | 0,007 | 2,630 | 20,163 | 4,536 | |

| CFI | > 0,950 | 0,837 | 0,994 | 0,831 | 0,988 | 0,831 | 0,997 | 0,887 | 0,994 | 0,934 | 0,999 | 0,896 | 0,896 | 0,915 | 1,00 | 0,999 | 0,956 | 0,995 | |

| TLI | > 0,950 | 0,796 | 0,99 | 0,800 | 0,983 | 0,747 | 0,993 | 0,864 | 0,988 | 0,901 | 0,999 | 0,826 | 0,826 | 0,745 | 1,002 | 0,996 | 0,941 | 0,989 | |

| RMSR | < 0,080 | 0,080 | 0,016 | 0,049 | 0,015 | 0,079 | 0,009 | 0,067 | 0,016 | 0,026 | 0,003 | 0,058 | 0,058 | 0,057 | 0,000 | 0,008 | 0,140 | 0,047 | |

| RMSEA | < 0,060 | 0,159 | 0,039 | 0,140 | 0,044 | 0,238 | 0,040 | 0,143 | 0,043 | 0,194 | 0,024 | 0,195 | 0,195 | 0,237 | 0,000 | 0,028 | 0,097 | 0,042 | |

| CR | > 0,700 | .... | 0,902 | .... | 0,932 | ... | 0,889 | ... | 0,951 | ... | 0,954 | ...... | ...... | ... | 0,781 | 0,794 | ... | 0,918 | |

| AVE | > 0,500 | .... | 0,510 | .... | 0,513 | ... | 0,538 | ... | 0,604 | ... | 0,750 | ...... | ...... | ... | 0,482 | 0,500 | ... | 0,560 | |

| Alpha | > 0,700 | 0,918 | 0,906 | 0,930 | 0,934 | ... | 0,901 | ... | 0,955 | ... | 0,958 | 0,879 | 0,879 | ... | 0,775 | 0,777 | ... | 0,918 | |

Source: Prepared by the authors (2022)

IM: Initial Model; FM: Final Model; DF: Degrees of Freedom; CR: Composite Reliability; AVE: Average Variance Extracted.

Upon verifying the initial models, it can be seen that the values are outside the pre-established standards. In this sense, the necessary procedures were carried out to adjust the indices, adopting two main measures: the removal of variables with a coefficient lower than 0,5 (Hair Junior et al. , 2014) and the insertion of correlations between the variables errors, which were suggested by the software and that made theoretical sense.

For the nine constructs, it is observed that the models initially proposed refer to the model with all the variables of the original scale, and only the “Selection Processes” construct presented an adequate initial model, with no adjustments required. The adjustment indices of the “HEI Infrastructure”, “Course Subjects”, “Graduate Course Impacts”, “Professional Development” constructs corroborate that the model is not adjusted because the division between the Chi-Square and the degrees of freedom is greater than 5, the CFI and TLI are less than 0,95, and the RMSEA is greater than 0,06.

Thus, in order to reach the validity and reliability adjustment indices, the correlations indicated by the software were inserted, in addition to the variables 1, 10, 23, 71 and 79 were removed. After these changes, all adjustments, reliability and unidimensionality indices of the constructs showed satisfactory values.

Once the model adjustment procedures were performed, the Composite Reliability and Cronbach’s Alpha of the constructs were calculated, and all resulted above 0,700, as indicated in the literature (Hair Junior et al. , 2014). It is observed that the convergent validity of the constructs also reached adequate values through the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), which demonstrates the results obtained with values close, equal and higher than 0,5, as suggested by Hair Junior et al. (2014). It is noteworthy that the AVE from the “Professional Development” construct (0,482) does not compromise its convergent validity since the value is close to that suggested in the literature, and the other indices are adequate, indicating the adequacy of the construct.

In order to verify the discriminant validity of the constructs set, Fornell and Lacker’s criteria (1981) were used, in which the correlation of all construct pairs was verified and compared with the square root of the AVE. Table 4 shows the results.

Table 4 Discriminating Validity

| Inf-IES | Dis-C | Do-C | Su-O | Su-A | Im-PPG | DV | Pr-S | Sa-PPG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEI Infrastructure (Inf-IES) | 0,714 | ||||||||

| Course Subjects (Dis-C) | 0,517 | 0,716 | |||||||

| Course Professors (Do-C) | 0,500 | 0,892 | 0,733 | ||||||

| Advisor Support (Su-O) | 0,291 | 0,520 | 0,625 | 0,777 | |||||

| Administrative Support (Su-A) | 0,273 | 0,395 | 0,473 | 0,337 | 0,866 | ||||

| Graduate Course Impacts (Im-PPG) | 0,478 | 0,730 | 0,747 | 0,515 | 0,401 | 0,749 | |||

| Professional Development (DV) | 0,417 | 0,707 | 0,693 | 0,605 | 0,324 | 0,754 | 0,694 | ||

| Selection Processes (Pr-S) | 0,408 | 0,701 | 0,668 | 0,472 | 0,408 | 0,684 | 0,641 | 0,707 | |

| Satisfaction with the Course (Sa-PPG) | 0,335 | 0,582 | 0,590 | 0,428 | 0,284 | 0,615 | 0,587 | 0,530 | 0,748 |

Source: Prepared by the authors (2022)

According to the data in Table 4 , it can be seen that all constructs pairs obtained the values of the correlations between the constructs smaller than the square root of the AVE, indicating the discriminant validity. The following relationships were the exceptions: “Course Subjects” – “Course Professors” (0,892), “Course Professors” – “Graduate Course Impacts” (0,747) and “Graduate Course Impacts” – “Professional Development” (0,754), which presented correlation values greater than the AVE. As an alternative procedure to assess the discriminant validity of these constructs, the Chi-square difference test was performed (Bagozzi, Yi and Phillips, 1991). The results of this test indicated differences between the restricted model and the free model greater than 3,84, which suggests the existence of discriminant validity. In addition, it is observed that the correlations between the constructs are less than 0,85, also meeting the criterion proposed by Kline (2015).

After carrying out all the procedures related to the validation and reliability of the nine first-order constructs presented, it is confirmed that the results of the indices reached the proposed parameters, demonstrating that the constructs have convergent validity, reliability and discriminant validity.

4.2 Integrated model analysis

To analyse the integrated model, the first procedure performed was the validation of the second-order construct, called “Course Assessment”. The results of the validation procedure are shown in Table 5 .

Table 5 Adjustment indices of the second-order construct and the integrated model

| Indices | Criteria | Course Assessment (second-order construct) | Integrated Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| IM | FM | IM | FM | ||

| x 2 (value) | --- | 162,246 | 367,400 | 17465,421 | 6104,581 |

| x 2 (probability) | >0,05 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 |

| x 2 /degrees of freedom | < 5 | 28,443 | 7,654 | 6,687 | 2,769 |

| CFI – Comparative Fit Index | > 0,95 | 0,889 | 0,977 | 0,885 | 0,966 |

| TLI – Tucker-Lewis Index | > 0,95 | 0,847 | 0,963 | 0,878 | 0,963 |

| RMSR – Root Mean Square Residual | < 0,08 | 0,069 | 0,032 | 0,250 | 0,044 |

| RMSEA – R.M.S. Error of Approximation | < 0,06 | 0,116 | 0,057 | 0,053 | 0,029 |

Source: Prepared by the authors (2022)

Once the second-order construct was validated, the analysis of the integrated model was performed. To verify the validity of the integrated model, analyses of the Chi-square, Chi-square/degrees of freedom, CFI, TLI, RMSR and RMSEA indices were used. The results are also presented in Table 5 .

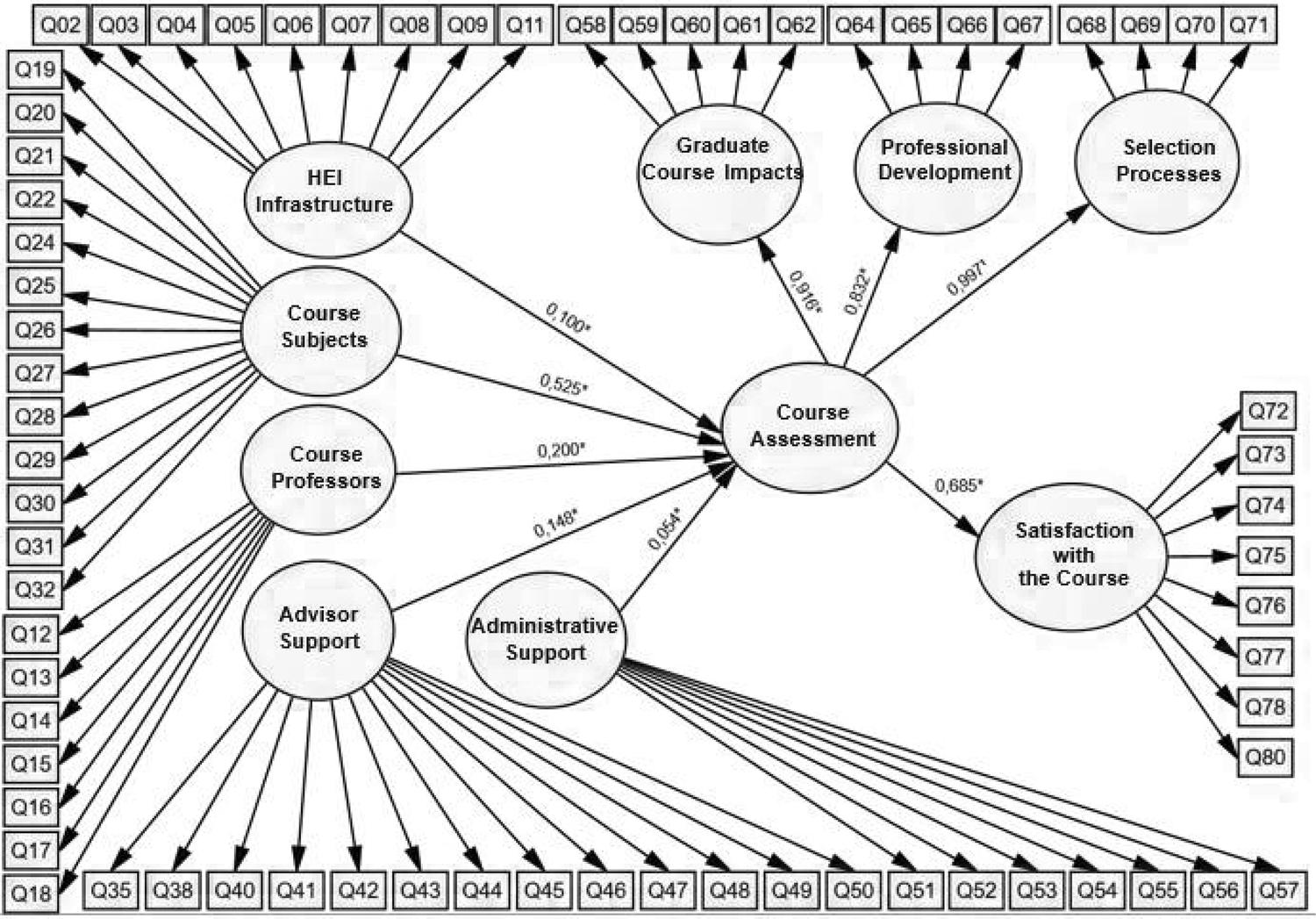

The proposed model initially presented inadequate adjustment indices. Therefore, the strategy of including correlations between the variables errors that made theoretical sense was adopted. Thus, Figure 2 presents the final integrated model with standardised coefficients and significance of the relationships between the constructs.

The relationship evidenced in the theoretical model shown in Figure 2 demonstrates that the assessment of graduate courses is directly influenced by the “HEI Infrastructure”, “Course Subjects”, “Course Professors”, “Advisor Support” and “Administrative Support” factors. The highest impact is exerted by the course subjects (0,525) and the course professors (0,200). This is in line with studies carried out by De Rezende et al. (2017), who found that the faculty also directly impacts the academic performance of graduate students. They are also consistent with the literature that highlights the role of the teacher by promoting a harmonious and democratic dialogue with students with respect, availability, care and receptivity, (Alves; Espindola; Bianchetti, 2012) and so, directly contributes to a positive self-evaluation of the course.

It can also be seen that the course assessment is formed by the first-order constructs: “Graduate Course Impacts”, “Professional Development” and “Selection Processes”, which have a regression load higher than 0,8, indicating a strong influence on the second-order construct.

Another point to be highlighted from the model results is that the course assessment has a significant influence on the course satisfaction. In other words, there is a causal relationship between two constructs so that better course evaluation results imply a better perception of satisfaction by students and alumni.

It is also necessary to highlight that the variables defended in the projection of the initial model were, for the most part, accepted after the estimations and validity tests, corroborating the adequacy of the proposed model. The results of the factor loadings of each item (observed variable) in relation to its first-order construct are shown in Appendix A.

Finally, the averages were estimated to identify the perception of students and alumni in each of the model dimensions of the model.

For the five antecedents of the course assessment, there were four averages: “HEI Infrastructure” (3,63), “Course Subjects” (4,21), “Course Professors” (4,23), “Advisor Support” (4,35) and “Administrative Support” (4,52). Considering that the scale varies from 1 to 5, it appears that the respondents consider the “HEI Infrastructure” very adequate and that they agree with most of the issues related to Subjects, Professors and Support. Also, for these three constructs: “Graduate Course Impacts” (4,26), “Professional Development” (4,35) and “Selection Processes” (4,32), and for the “Course Assessment” factor (4,31), the averages are slightly higher than 4, stating that students and alumni positively assess the graduate course. Furthermore, it is observed that the “Satisfaction with the Graduate Course” is high, as it reached an average of 8,106 on a scale from zero (totally unsatisfied) to ten (totally satisfied). Therefore, the average results indicate that the institution’s graduate courses are well-assessed, and that students and alumni are satisfied.

Thus, the estimation and validation results presented in this section demonstrate the possibility of using a very comprehensive and complete model for student self-assessment. In line with the self-assessment literature that suggests the need to create models capable of highlighting the complexity, plurality and challenges of self-assessment in university institutions, since it is influenced by structural and situational elements (Lehfeld et al., 2010). Such results are essential because they are associated with the development of students’ skills and their employability (ST Jorre; Oliver, 2018).

5 Final Considerations

Self-assessment as an assessment process has several dimensions and encompasses the perception of different stakeholders, that is, it includes professors, students, the community, and alumni. In this study, the main actor is the student, and the main goal is their self-assessment of the graduate course.

For this, a multidimensional model of self-assessment was developed with five evaluation antecedents (“HEI Infrastructure”, “Course Subjects”, “Course Professors”, “Advisor Support”, “Administrative Support”) and “Satisfaction” is the dimension directly impacted by the course assessment.

In the process of building the model, several validation tests were performed, which analysed and indicated the unidimensionality and the convergent and discriminant validity of all the proposed dimensions. The estimation of the integrated model confirmed the impact of antecedents on the graduate course assessment and its direct influence on satisfaction. Altogether, these results indicated that the proposed self-assessment model is robust and parsimonious.

Since Capes has included self-assessment as one of the assessments of graduate courses, the use of student self-assessment models should be adopted by all programs, so the self-assessment model presented in this article can become useful to several courses. The use of a multidimensional measure allows a broad approach to the different aspects that impact directly on the course assessment and indirectly on the satisfaction of students and alumni. It is also worth noting that the measure as a whole or some of its dimensions can be used to assess other stakeholders in the self-assessment process, such as alumni.

The practice of student self-assessment, by itself, is already a fundamental process for self-regulated and lifelong learning (Yan, 2020), as it leads students to reflect on the gap between current and desirable performance levels (Yan; Carless, 2022). However, Brazil still does not have a culture favorable to the self-assessment process, which is often criticized for inducing behaviors and valuations, either positive and negative, based on indicators that are not always accepted or seen as the most appropriate (Leite et al., 2020).

Thus, the construction of adequate measurement models is just one of the first conditions for the implementation of a self-assessment policy capable of effectively indicating the strengths and possible improvements to graduate courses managers. Just with the development of a continuous self-assessment policy that promotes effective feedback a country’s graduate system evolves. Thus, in addition to choosing an appropriate model, it is necessary for graduate courses to establish their own self-assessment policy, taking into account both the rules established by Capes and their own criteria.

As for the research limitations, we can mention the application of the questionnaire via the Internet and the fact that the research was carried out only at one university. It is suggested that future works use other samples and analyse the possible differences arising from the course level (master’s and doctorate). New scale validation tests can also be performed.