Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 1517-9702versión On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.46 São Paulo 2020 Epub 24-Sep-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202046221756

SECTION: ARTICLES

Anti-gender discourse and LGBT and feminist agendas in state-level education plans: tensions and disputes

1- University of São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Contact: cpvianna@usp.br; bortolini.alexandre@gmail.com

This article presents the results of a research on the use of gender in education plans of 25 Brazilian states and the Federal District, enacted between 2014 and 2016. We demonstrate that the disputes around the gender issues in the plans bespeak that there is not just one way of excluding or excluding the topic, namely: the veto; leaving out the word and other related terms; the specification of gender as women´s right and the right of the LGBT community in order to ensure access to and permanence in quality education, and the partial use associated with human rights, the guarantee of some women´s rights, and the culture of peace. Over half the plans included issues related to the women´s agenda in a gender perspective. Almost one third of the plans clearly express that ensuring access and permanence with quality involves confronting gender inequalities. The fixed and binary nature of the opposition between male and female meanings was problematized when fighting sexism, machismo, and LGBTphobia was embraced. However, several plans indicated the move of conservative agendas by excluding gender, by cutting or limiting the LGBT agenda, and by including items that demand that dealing with such topics be subject to family approval. Conclusion is that the conservative anti-gender advance, at least in the period under screen, is opposed to maintaining a number of political achievements. Therefore, contradictions remain in the disputes of power through the contribution of gender in the social function of education.

Key words: Educational policy; Gender; Education state-level plan; LGBT; Anti-gender agenda

Este artigo apresenta resultados de pesquisa sobre o uso do gênero nos 25 planos estaduais e distrital de educação promulgados entre 2014 e 2016. Demonstramos que as disputas em torno das questões de gênero nos planos evidenciam que não existe apenas uma forma de excluir ou incluir o tema, a saber: o veto; a omissão do termo e de outros a ele relacionados; a explicitação do gênero como um direito das mulheres e da população LGBT para a garantia de acesso e de permanência à educação de qualidade e o uso parcial com referências aos direitos humanos, à garantia de alguns direitos das mulheres e à cultura da paz. Mais da metade dos planos inseriu questões relativas à agenda das mulheres, sob uma perspectiva de gênero. Quase um terço dos planos expressam clareza de que a garantia de acesso e permanência com qualidade passa pelo enfrentamento das desigualdades de gênero. O caráter fixo e binário da oposição entre significados masculinos e femininos foi problematizado ao se incluir o combate ao sexismo, ao machismo e à LGBTfobia. Entretanto, vários planos manifestam o avanço de pautas conservadoras com a exclusão do gênero, corte ou limitação da agenda LGBT e inserção de itens que submetem a abordagem destes temas na escola à concordância das famílias. Conclui-se que o avanço conservador antigênero, ao menos no momento examinado, contrapõe-se à manutenção de várias conquistas. Permanecem, portanto, as contradições nas disputas de poder pela contribuição do gênero na função social da educação.

Palavras-Chave: Política educacional; Gênero; Plano estadual de educação; LGBT; Agenda antigênero

This article exposes and analyze the results of a research nearly completed2 concerning how the critical perspectives on gender relations and the production of sexualities have been expressed, omitted, partially included or even vetoed in the education plans in each Brazilian state and in the federal district enacted between 2014 and 2016, from now on simply named education plans.

The investigation started by looking at democratization of education focusing on its public policies in the perspective of the social gender relations. The intention was dialogue with the already broad academic production on gender and sexuality in education, initially disseminated in Brazil by Guacira Lopes Louro (1999, 2006) and widely expanded over the last decades, according to the most recent reviews (VIANNA; UNBEHAUM, 2016; VIANNA, 2018). The investigation whose results are presented in this article utilizes gender as a concept capable of seizing the social and historical construction of the social relations concerning it, combined with the multiple processes of cultural, economic, political, and symbolic domination (SCOTT, 1995, 2011) and, therefore, as a fruitful category to analyze the educational policies, seen as a process of creation – tense and negotiated – among groups that claim tangible interests from the State. Whereas the analysis of making of the educational policies must begin by identifying the respective groups that claim from the State interests of material and symbolic nature (CUNHA, 2002), it is possible to look at these policies not only as claims, but also as responses materialized in the form of documents, plans, programs, and actions (VIEIRA, 2007) resulting from heated disputes.

The investigation sought to comprehend the way the recent debate around the approval of the education plans was traversed by these disputes, leading sectors connected with feminist and LGBT3 activism to confront groups organized to fight the introduction of gender perspectives in the public policies. The purpose was to capture the language and the contents of the education plans (PEE) taken as documents indicating intents, interests, power struggles involving the different conceptions of education, as well as to question how critical perspectives on gender relations and the production of sexualities were included or, in extreme cases, were excluded from those educational norms.

In our analysis, we have sought to identify the intersection of the gender and sexuality issues in the education plans enacted between 2014 and 2016. The clear expression, partial inclusion, omission, or the veto concerning these dimensions in the plans are indications of to what extent and how those topics were negotiated in the making of the educational policies on the state level and in the Federal District. We surveyed all the plans available for the next decade. The states of Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro, until the completion of this article, had not approved an Education plan for the period. We examined, therefore, 24 education state plans and the federal district plan.

The information analyzed here has been obtained from the public digital platforms of the respective legislative chambers in each state and the federal district. The access to information provided by these platforms varies from state to state. In some of them, only the final act of law was available, in others it was also possible to read the original bill and in some the entire legislative proceedings could be viewed, with its amendments, minutes, reports from committees and other documents available.

In this article, we prioritize the text found in the publication of the final version of the law, without leaving aside the understanding that it is not a static version, but it rather charged with contradictions and disputes of power around the role played by gender relations and the production of sexualities in education. We demonstrate that the education plans recently passed show in their wording tensions and disputes between: the explanation of gender as an important tool to confront gender inequalities in a variety of levels and categories in Brazilian education; the partial use of gender in reference to women, human rights, and culture of peace; the term gender and other related words being omitted or even vetoed.

Gender and production of sexualities in the public education policies

Reviewing the context in which public education policies are made from the perspective of social gender relations bespeaks a tense process of negotiation that determines its materialization but also the withdrawal of reforms, plans, projects, programs, and actions implemented, separately or combined, by the State and the social movements and collective actions which press for new public policies, by occupying spaces in the public administration, and by acknowledging new forms of inequality. Both the State and the social movements, in their respective plurality, combine themselves and/or toughly dispute social interests at stake in this process. In such arena of relations that are necessarily conflictive and, sometimes contradictory, articulating these policies leads us to the discussion of complexities.

From the mid-1990´s on and in early 2000, there was a gradual openness in education towards discussing gender relations in the sphere of public policies. Studies conducted in the last decades reveal the introduction of gender perspectives and socio-historical approaches to sexualities in the public education policies. The issue was actually resumed in the educational area took place from 1995 on, due to the pressure made by the women´s movement and upon the continuing responses by the administration of former President Fernando Henrique Cardoso to the international commitments related to the gender and sexuality agenda, together with the goals of the Millennium and the Dakar Conference regarding education (ANDRADE, 2004; VIANNA; UNBEHAUM, 2004).

Under the government of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, this movement continues in the rise and then also embraces the recognition of the diversity of sexual orientations and gender identities in a more explicit way, even if with a great deal of tensions.

In this arena of necessarily conflictive and sometimes contradictory relations, making such policies involves theoretical strands and collective actions restricted to the Women´s Movement and to the Movement of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Tranvestites, Transexuals, and Transgender People (LGBT). Both took a leading role in proposing a number of projects and programs in the federal and state levels concerning the inclusion of sexual diversity in the schools. There was also great influence from sectors representing international forces, with crucial participation in domestic affairs and in fabricating lines of action for public policies in education. The organization of the first National Plan of Policies for Women (PNPM), in 2004, and of its second edition in 2008, both preceded by the Conferences of Policies for Women (2004 and 2007), and by the Program Brazil Without Homophobia (BSH), in 2004, are a few examples.

It is worth emphasizing that the process was a victory of women, of LGBT people, and of other collective subjects politically organized in developing agendas, sometimes combined, sometimes specific, but recurrently converging. Implementing these agendas in Brazilian education; implementing policies for in-service training in gender, sexualities, and reproductive rights to teachers; including the topic in learning materials and in the national exams; enhancing sexual education in the schools; regulating the acknowledgment of gender identity of transgender people in various institutions and schooling systems, and including those dimensions in different national educational guidelines are examples of such achievements, recorded in several researches (ANDRADE, 2004; CARREIRA, 2015; FERNANDES, 2011; LOURO, 2006; DESLANDES, 2016, and more).

It is important to highlight that this was the tone in the policies of gender and sexual diversity prioritized along the two terms of former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva – the first one between 2003/2006 and the second one between 2007/2010 – leaving an imprint in the plans and programs within the educational field. But one cannot imply that this path was taken in a linear fashion towards the great advancements that would guarantee the introduction and institutionalization of all demands being negotiated. Quite the contrary. Those were times of organizing the demands but also of tough clashes and resistances.

In a study about the how the agenda of diversities was devised in the education policies under the administrations of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff, Denise Carreira (2015) highlights the disputes around the gender agenda. One of them involved the fact the agendas of diversities gradually stole the spotlight, even before Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva being elected in 2003. Along the first term, there was pressure from the social movements in negotiating the agenda of diversity as an element that would virtually aggregate the agenda for the educational policy “under permanent tension with the notion of affirmative actions, strengthened after Durban [Conference], and with the notion of social inclusion, which was hegemonic in the federal government” (CARREIRA, 2015, p. 173). Another characteristic of this dispute was how precarious and fragmented, and even partial, the agendas were brought in. And, finally, one should remind the systematic resistances from several sectors of society at large, from the Congress and government, and also from the very Ministry of Education (MEC).

The visibility given to those topics in the educational policies gave rise to a debate around issues so far ignored, mainly because they were seen as taboos in the school ambience. Regarding this aspect, we may say that it gave voice to topics that had been silenced till then, getting close to what Ball defines as “policies of change” in reference to the appropriation of these federal policies by the micropolitics in the schools, which bring “to surface the underground conflicts and differences that otherwise would remain silenced in the everyday routine of school life” (BALL, 1989, p. 45).

This advancement, even though precarious and strained, finds a turning point in veto committed by the Dilma Roussef administration to the set of materials being produced by the project Schools With Homophobia. Managend by the Ministry of Education and carried out since 2009 by a group of non-governmental organizations, the project included seminars to be held with education professionals, managers, and representatives from civil society, a research to be conducted about the theme in 11 capital cities in the five geographic regions of Brazil, and a package of educative materials. The set became known as the “kit”, consisting of a pedagogical notebook with activities to be conducted by teachers in the classroom; six newsletters for discussion with the students and three audiovisuals, each of them provided with a guide, a poster, and presentation letters for managers and teachers.

However, upon being pressed by the conservative religious bench in the National Congress, president Dilma Rousseff vetoed the material in May, 2011, claiming it was improper. According to the Ministry of Education, the veto had to do with three videos portraying affirmative stories of gender identities and sexual orientations by students who questioned the heteronormative standards in the schools. The remainder of the material could still be shared in the public educational institutions. But that never happened, revealing the tension between those who defend versus those who are against gender and sexual diversity in the education policies. Vetoing the “kit” was not an isolated incident, as along the process it was possible to clearly see the federal government setback resulting in the loss of a great deal of agendas that had been achieved (FERNANDES, 2011; CARREIRA, 2015; DESLANDES, 2016; VIANNA, 2018).

Many of those victories, which had never been structural, were actually fragile and their continuity was uncertain. But this was perhaps the first incident that more overtly revealed the mentioned tension between defense of and attack against sexual diversity in the educational policies, part of a broader movement of confronting the inclusion of gender in public policies not only in Brazil but also in different parts of the world.

In an effort to reconstruct this history, Sonia Corrêa (2018) acknowledges that there is not an accurate moment when the confrontation began, but the most widespread version goes back to the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), best known as the Cairo Conference, held in September, 1994, and 4th World Conference on Women: Action for Equality, Development, and Peace, organized by the United Nations in Beijing in 1995, with marks of heated debates.

The Cairo Conference was responsible for expressing and detailing reproductive rights as well the right to information and support required when making such decision. In turn, the 4th World Conference on Women was the stage of an intense debate about sexual rights, that is, one´s right to live their own sexuality and reproduction free of discrimination, coercion, or violence.

During the Cairo Conference, the Vatican unsuccessfully tried to ban the use of the words gender or families, in the plural. Confronting the movements that advocate for women´s reproductive and sexual rights, the Holy See was able to get together in a mor incisive way during the 4th World Conference on Women opposing the feminist agenda by defending a generalist discourse and by taking the role of speaker for the human rights and for the women´s rights, even though the Catholic Church was exclusively represented by men. The upsurge of this very crusade against gender (JUNQUEIRA, 2017) gained momentum in the early 21st century. The most conservative sectors of the Holy See took as their starting point the criticism to the feminist theories to create a theological counter-discourse which accuses international bodies, including the United Nations Organization (UNO), of disseminating what was then called “gender ideology”.

Examples of the extent to which the Catholic Church invested against gender are the Lexicon of ambiguous and disputable terms about family life and ethics (JOHN PAUL II, 2003)4 and the Letter to the Bishops of the Church about the collaboration of men and women in the Church and in the world (CONGREGATION..., 2004). The first document presents the expression “gender ideology” defined as part of the radical feminist agenda intended to crumble the family as a result of questioning the sexual differences. In turn, the Letter to the Bishops of the Church inquires the assumptions of the gender studies, more specifically the criticism to heteronormativity.

In reaction to the gender perspective moving upward, the Catholic counteroffensive was coordinated with conservative religious representatives of the bishops´ conferences from several countries, with pro-life and pro-family movements and with far-right sectors not necessarily religious. This offensive was progressively made on the transnational level over the last decades and a great number of reflections draw attention to the transnational dimension of this phenomenon characterized by many as an anti-gender crusade, campaign or offensive (REIS; EGGERT, 2017; LUNA, 2017; SILVA; CÉSAR, 2017; CASTELLS, 2017; CORNEJO-VALLE; PICHARDO, 2017; JUNQUEIRA, 2017; CORRÊA, 2018; PRADO; CORRÊA, 2018). Such crusade resulted in excluding these terms not only from the National Education Plan, but also from part of the education plans in the Brazilian states. However, again, we must emphasize that this has not been a linear process.

In the specific field of education, the reactionary endeavor expanded both in defending traditional moral values and religious viewpoints in bioethics (JUNQUEIRA, 2017) and contrary to the legal reforms, social policies in general, and, specifically, in the areas of health and education, such as sexual education, appreciation of the different sexual orientations, the plurality in family composition, and the recognition of gender identity as self-assigned.

This crusade proved effective at the time when the national education plan was being voted upon. In a tensioned political scenario, conservative groups – advocates of violent solutions to social issues, rural caucus members, Catholic and Evangelical religious leaders –, supported by other religious denominations (Kardecists and Jews) or non-religious groups gathering different professionals, but also the Movement Brazil Free (MBL)5 and the Movement Schools without Political Parties (ESP)6 acted in coordinated fashion while the proceedings of the national education plan were in progress in the Congress whose climax was the gender issues being withdrawn. The final version of the national education plan (2014-2024), promulgated as law, approved the goal of fighting educational inequalities with a generalist reference to eradicating all forms of discrimination.

Although the final text continues to legally support actions to confront LGBTphobia, to acknowledge and value gender and sexual diversity, and to promote sexual and reproductive rights, suppression the express mention to gender resulted in a support to discourses that the NEP would have vetoed everything that might relate to “gender ideology” in the educational policies.

This narrative had a significant impact on the making of the education plans in the states and in the federal district, which is specifically focused in this article.

Education plans in the states and in the federal district

The process through which the education plans was made in the Brazilian states and in the federal district is diverse, with different degrees and sorts of social participation. The plan is materialized in a law, whose initial bill is necessarily drafted by the government, then it is forwarded to the legislative body in each state. It is assessed – and perhaps modified – in the committees and in the plenary vote of the legislative body, by means of amendments or substitutions, the bill returns to the government, which may veto it in part; the vetoes will be maintained or overturned by the legislative chamber, and it is eventually passed into law.

Most of the laws here analysed basically follows the same structure found in the national education plan: there is a text passed into law, organized in articles and paragraphs, which defines guidelines, objectives, and other general issues, followed by an exhibit where the goals and their respective strategies are included. Out of the plans reviewed, 14 present one single exhibit with goals and strategies while 11 plans also contain a diagnostic or situational analysis of education in each state. Since more than a half states did not add the latter item, our study excluded such diagnostic or situational analysis.

As the education plans are structured in a similar fashion, some contradictions are blatant in the texts, which makes it easy to see the local variations in the disputes around these topics. Reviewing the plans draws a map revealing the outcome of the negotiation, but also a number of disputes, whose meaning and characteristics are materialized in the text passed into law.

It is important to highlight the fact that, in the face of we have found, it does not seem possible, nor even useful, to dichotomously organize the education plans pointing out the ones which include gender and those that do not. There is no point, therefore, in dividing them between those against and those in favor, between those that veto and those promoting the addition of a perspective of gender in the educational policy, but rather realize the different forms through which the plans deal with such issues and what we learn about the political struggles amidst which they have been. What have we found out?

The detailed account presented as follows shows that the disputes around gender issues in the 25 education plans is evidence that there is not only one way of excluding or including the topic. Working on gender as an object of dispute and confrontation with anti-gender policies in education focusing on how they are dealt with in the education plans means to take the challenge of breaking away with the understanding of “gender ideology” as a strategy to conceal or smoke screen issues that are more crucial to our society. “Gender ideology” in this context is not a concept nor an analytical category, it is an accusation category powerfully utilized in context in which the “anti-gender logic is no longer a strategy of mobilization spread in socio-institutional fabric intended to convert itself into an explicit public policy” (PRADO; CORRÊA, 2018, p. 447) and re-signified in the dispute that unfolds in the education plans and in the understanding of the very social function of education.

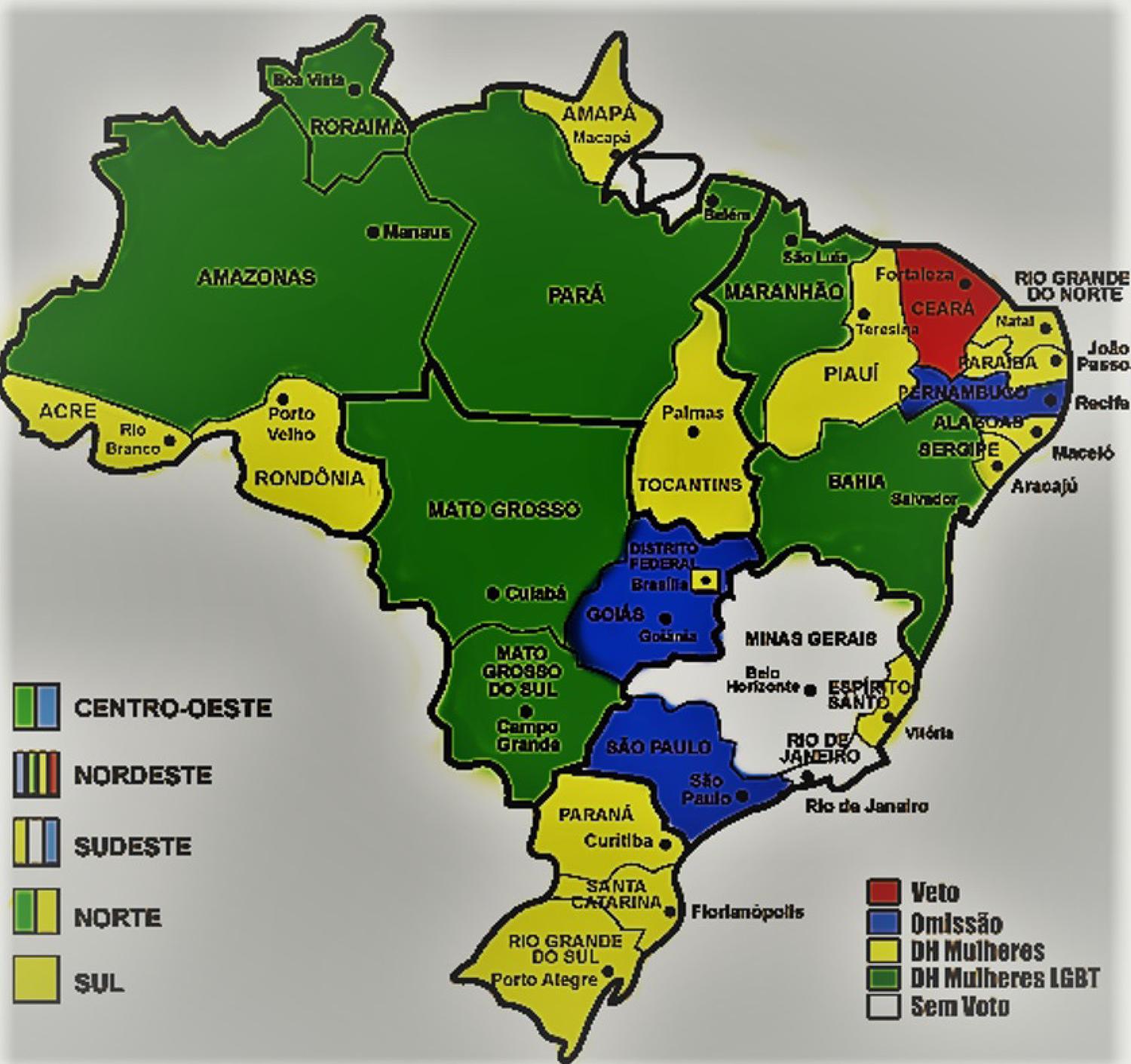

The 25 education plans we have examined – 24 states and the Federal District – can be divided into four groups. Some states address aspects that belong to two groups, but we chose to include them in the group whose tendency is more clearly defended in each of the education plans we were looking at.

The first group (red) concerns the veto and consists of only one state (CE).

The second group (blue) with three states is characterized by omitting the term gender and any other word related to it (GO, PE, SP).

The third cluster (yellow), with 14 states (AP, AC, AL, ES, DF, PB, PI, PR, RN, RO, RS, SC, SE, TO), is highlighted by partially including the topic, with references to human rights, to ensuring some women´s rights, and to the culture of peace, but in a restricted way, sometime reiterating binary perspectives, sometimes evoking the precedence of family over the school. None of these plans include references to LGBT demands.

The fourth group (green) with seven states operates with clear mention of gender and sexuality issues, both in what concerns overcoming inequalities and promoting women´s rights, and in acknowledging, protecting, and promoting the rights of LGBT people (AM, BA, MA, MT, MTS, PA, RR).

The four ways gender and the production of sexualities were addressed can be best visualized in the map shown, which are described in detail in Figure 1.

Gender veto (CE)

Of all plans reviewed, State Education Plan of the state of Ceará is the only one whose guidelines include a paragraph that overtly “forbids, under any justification, the use of gender ideology in the state education” (CEARÁ, 2016, Art. 3º, Paragraph XV, our emphasis).

Such veto, however, gets along with mentions which, initially, seem contradictory. In Goal 21, Strategy 21.10, the plan indicates “adjustments in curricula of schools for indigenous people, Quilombo residents, and peasants” in order to include contents that will help

[...] develop culture to overcome prejudice and discrimination against populational segments, including racism, sexual orientation, machismo, religious intolerance and generation, ethnicity, agroecology, territorial management, traditional medicine, body painting and indigenous rituals etc.) which meet the reality and the specificities of those communities. (CEARÁ, 2016, our emphasis)

Goal 8 foresees an increase in the population´s schooling and includes as target public

[...] populational segments that undergo prejudices and oppressions on account of their nationality, social status and place of birth, race, color, religion, ethinic origin, political or philosophical conviction, physical or mental disability, illness, age, professional activity, marital status, social class, sex, sexual orientation, and family morality respecting the guidance by parents and/or guardians. (CEARÁ, 2016, Goal 8, our emphasis).

This statement is repeated in the strategies intended to expand vacancies in the Education of Youths and Adults (EYA) and initial and continued training of teachers, managers, and other education professionals (CEARÁ, 2016, Goal 8, Strategies 8.3, 8.8). The document also highlights how important it is to “allow the productive inclusion and economic autonomy of women”, emphasizing the strategy of universalizing the provision of “Child Education, starting at (zero) month of age, full-time daycare centers; Elementary/Middle/High School in communities of indigenous people, Quilombo residents, and peasants, regardless of the number of students” (CEARÁ, 2016, Goal 21, Strategy 21.1, our emphasis). These references bespeak the presence of the deliberations of the seven lines of discussion in The National Education Conference (CONAE), including Line II “Education and Diversity: Social Justice, Inclusion, and Human Rights” in compliance with the principles of teaching set forth by the Act of Guidelines and Grounds for the National Education (BRAZIL, 1996) which, according to Article 3 of the Brazilian Federal Constitution of 1988, includes among the fundamental objectives of the Federal Republic of Brazil “to promote the welfare of all, without prejudices of origin, race, sex, color, age, and any other forms of discrimination” (BRAZIL, 1988/2001).

It should be noted, however, that those mentions share room with the necessary family´s control and prerogative over the school in addressing such topics, in reference to an alleged family morality. In order to do so, the plan´s strategies include, one of them is in Goal 7, fostering the quality of basic education in all stages and levels the “previous and specific assessment of school materials, intended for children and adolescents, covering at least the following items: racism, prejudice, discrimination, and sexual orientation” (CEARÁ, 2016, Goal 7, Strategy 7.49, our emphasis). Although it seems contradictory, this education plan expresses the power of conservative sectors active in the legislative branch. The very text justifies the veto based on the syntagma7 of “gender ideology” –, with the purpose of reporting and condemning the alleged doctrinaire nature of the gender approach in the moral education of children and adolescents, bringing about real panic to the families concerning these topics. That is why family control is crucial to avoid an alleged breakup of the male and female social roles and, consequently, of the nuclear family.

The strong anti-feminist and heteronormative twist in the “gender ideology” becomes crystal-clear on behalf of the heterosexual family as the rule, of the female role in the center of the household world supported by the “concept of ‘human nature’ as a result of a ‘natural law’ given by God, proven by biology and unchangeable, which is a key component in arguing to condemn gender deemed as an ‘ideology’, with a strong negative connotation” (ROSADO-NUNES, 2015, p. 1250). The very definition of family is sustained by an unchangeable biological concept of man and woman as well as of reproduction. The essentialist use of woman, in singular or in universal plural, presupposes a universal feminine identity, with evident biological connotations and the strong intention of generating hierarchies that uphold relations which are unequal and of domination in the specific sphere of the family, also referred to in singular and so advocated by the Vatican the Cairo Conference.

Leaving out all and any mention of gender (GO, PE, SP)

As in most Brazilian states, Goiás, Pernambuco, and São Paulo witnessed strong protests during the vote in the Legislative Chambers, impacted by the anti-gender context when the National Education Plan went to a vote (BRAZIL, 2014). The debate had a great effect on several state chambers in which the respective education plans were voted and there were mixed reactions which bringing together grassroot sectors, either influenced by church or not.

Despite the countless attempts by teachers and students in favor of addressing gender and sexual diversity issues in the schools, the states of Goiás, Pernambuco, and São Paulo left out all and any discussion concerning the topic. There was mention of the importance of carrying out actions in the schools that encourage a culture of peace, with safety and respect to the human rights, but the word gender was banned even if when it had other meanings (in Portuguese) together with all related terms – woman, man, sexual orientation, sexuality.

The state of São Paulo, in its Goal 3 concerning the rise of young people´s schooling level refers to fighting “any form of discrimination” (SÃO PAULO, 2016, Goal 3, Strategy 3.9, our emphasis) and the state of Goiás included protection from “violence, bullying, drug use and abuse” (GOIAS, 2015, Gol 2, Strategy 2.15, our emphasis). In turn, Pernambuco adds that fighting violence must be done with “identifying and suppressing all and any direct or indirect source that causes racism, discrimination, xenophobia, and related forms of intolerance, including in the curricula, practices and teaching/learning materials” (PERNAMBUCO, 2015, Go 8, Strategy 8.10, our emphasis), but mentioning discrimination, violence, or, in the case of Pernambuco, racism, xenophobia, and related forms of intolerance do not appear in connection with the gender perspective. Gender is absolutely left out from the education plans in those states. Once again, we observe the concealed nature of the mention of gender when the current national education plan is in point; that is a tendency pointed out in the beginning of the century when it was necessary to read between the lines in dealing with the policies intended for public education in attempt to see, amidst the defence of rights in general, small steps forward involving gender issues (VIANNA; UNBEHAUM, 2004).

Striking is also the language utilized in these plans characterized by the omission of gender. When naming the individuals of both sexes, the plans in this group emphasize the masculine words. We know that, in our society, the generic male form in the use of words combined with or written as a way of expressing and communicating is used to express ideas, feelings, and references to other people. However, this use is never neutral. Language as a system of meanings is an expression of the culture and of the social relations in a given historical moment. If, on one hand, the generic male form expresses a common way of speaking up, on the other hand – especially in documents intended to guide the public educational policies for a period of 10 years – does not go unpunished, since adopting the male form exclusively may express sexist discrimination and reinforce the androcentric linguistic model. Such androcentrism cannot (and should not) be accepted as unquestionable or a mere detail of the linguistic rule. Because it may give rise to hide gender inequalities. Acknowledging these inequalities is the first step to suppress it.

The partial use gender: human rights, women, culture of peace (AP, AC, AL, ES, DF, PB, PI, PR, RN, RO, RS, SC, SE, TO)

In the above 14 plans, mention of gender is generic under human rights or associated with specific rights for women or, also, praising the importance of respect between men and women and the culture of peace in the schools.

In the vast majority, not only the word gender was replaced by sex and the “men and women” pair was repeated throughout the text, but also any reference to sexual orientation and the affirmation of gender identities disappear, so that the cis-heteronormative patterns prevail. Only in the states of Rio Grande do Sul and Amapá the text leaves the word gender out but mentions include sexual orientation, just when talks about “promoting the principles of respect to the human rights, to diversity and to socio-environmental sustainability, to sexual orientation and to religious choices” (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 2015, Art. 2º, Paragraph X, our emphasis) and in the goal about expanding enrolment in higher education (AMAPÁ, 2015, Goal 15, Strategy 15.5), with no further developments.

The State Plan in Rio Grande do Norte (2016, Goal 1, our emphasis) talks about “inclusion actions to be implemented with the purpose of overcoming inequalities which affect women”. In addition, “indigenous and black people, quilombo dwellers, traditional peoples, peasants, and disabled persons” (RIO GRANDE DO NORTE, 2016), but LGBT people are not included. Mention of women is associated with the fight for daycare centers and child education as well as the care of children with no reference to reproductive rights or the right to information and support required to make this decision. Alagoas links the stimulus to women´s autonomy to expanding the provision of child education. The state includes a “survey and publication of the demand for daycare centers, for the population aged zero (0) to three (3) years, and pre-school, for children from four (4) to five (5) years old” (ALAGOAS, 2016, Goal 1, Strategy 1.8, our emphasis). Among adolescents and youths in middle school, the most recurring concern has to do with a set of situations: discrimination, prejudice, violence, and early pregnancy.

Espírito Santo (2015, Goal 3, Strategy 3.8), Pará (2015, Strategy 3.8), Rio Grande do Norte (2016, Goal 3, Strategy 10), Piauí (2015, Goal 3, Strategies 3.19 and 3.21), Sergipe (2015, Goal 3, Strategy 3.9), and Tocantins (2015, Goal 4, Strategy 4.12) include the list of the above situations as the aim to be followed up in order to ensure students benefitting from income transfer programs will remain and complete high-school.

In higher education, attention is drawn to policies of inclusion and social assistance to female students in the university (PARANÁ, 2015, Goal 12, Strategy 12.6) or even in graduate programs, in which the idea is “to stimulate women´s participation in graduate courses, especially those related to the areas of Engineering, Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Computing, and other in the field of science” (FEDERAL DISTRICT, 2015, Goal 14, Strategy 14.5; ALAGOAS, 2016, Goal 14, Strategy 14.8, our emphasis).

Another topic repeated in most plans of this group of Brazilian states is sexual and domestic violence, but there is no mention of gender or sexual orientation. This format appears in the state plans of Acre, Alagoas, Amapá, Amazonas, Ceará, Maranhão, Paraíba, Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Sergipe through texts that express the need to “guarantee policies to fight violence in the school and its surroundings, including carrying out actions intend for the training of teachers to that they will detect signs of its causes, such as sexual and domestic violence, fostering appropriate measures to promote the culture of peace and a safe school environment for the community” (Acre, 2015, Goal 7, Strategy 7.17; ALAGOAS, 2015, Goal 7, Strategy 7.43; AMAPÁ, 2015, Goal 4, Strategy 4.6; AMAZONAS, 2015, Goal 7, Strategy 7.18; CEARÁ; 2016, Goal 7, Strategy 7.20; MARANHÃO, 2014, Goal 8, Strategy 8.24; PARAÍBA, 2015, Goal 19, Strategy 19.23; PARANÁ, 2015, Goal 7, Strategy 7.22; SANTA CATARINA, 2015, Goal 7, Strategy 7.18; SERGIPE, 2015, Goal 7, Strategy 7.22, our emphasis).

In this group, there is an exception: a shorter text from the state Rio Grande do Norte (2016, Dimension 8, Goal 1, Strategy 10, our emphasis), which only argues about implementing “actions based on human rights to prevent drug abuse and violence towards women, children and young people, in the school context”.

Educating for respect is also included in some plans. The plan of Rio Grande do Norte is quite comprehensive and mentions all forms of prejudice and ensures the school curricula must address the “formative specificities and needs in the Education for Youths and Adults, for children, for teenagers, for the peasants, riverside dwellers, and gypsy communities ”, emphasizing “the perspective of human rights, adopting practices to overcome racism, machismo, sexism, and all forms of prejudice, in order to contribute to accomplish a non-discriminating education” (RIO GRANDE DO NORTE, 2016, Dimension 8, Goal 1, Item 4, our emphasis).

The guidelines of Federal District plan (2015, Art. 2, Paragraph XI, our emphasis) mention, in very generic way, the “promotion of the principles of respect to human rights”. Likewise, the state of Tocantins (2015, Goal 11, paragraphs I, II, III, our emphasis) has three paragraphs concerning the human rights, all of them included in the goal dealing with environmental education. Although they have been placed in a specific goal, they address general topics such as “implementing educational program and policies for the education in human rights, with the aim of ensuring individual and collective rights, citizenry, and respect for the differences”; “school curriculum that meets education in human rights, in all stages and levels of basic education, in a permanent and linking way, drawing from transversal and interdisciplinary pedagogical processes”.

The state of Paraná plan (2015, Goal 2, Strategy 2.21 our emphasis) highlights “the education that accomplishes respect among and between men and women” when it deals with the curriculum and basic/continued training of education workers (PARANÁ, 2015, Goal 1, Strategy 1.3; Goal 15, Strategy 15.11).

In this group of plans, the mention of respect is always followed by a caveat: the precedence of the family over the State. Many are the forms through which this precedence is stated, as for example in the guidelines of the Federal District plan, which mentions “promotion of the principles of human rights”, but compliant to a conditioning factor which subjects it to the “moral convictions of the students and their parents or guardians” (FEDERAL DISTRICT, 2015, Art. 2º, Paragraph XI, our emphasis). Or perhaps, in the Paraná plan which talks about the “specificities of the age bracket” (2015, Goal 1, Strategy 1.3; Goal 2, Strategy 2.21; Goal 15, 15.11, our emphasis), and “to acknowledge the precedence of the family over schooling up to graduation, to strengthen and accomplish the participation of parents in the pedagogical policies addressing the topic” (TOCANTINS, 2016, Art. 2º, Paragraph XII, our emphasis).

Gender perspective in these states is limited and resumes an approach that is very close to the hidden gender approach that is typical in the Federal Constitution (BRAZIL, 1988/2001) clouding gender issues within the wide range of human rights, culture of peace and respect among and between men and women, with no specific reference to the multiple inequalities these terms may encompass, as if their meanings were self-evident. Even though some state plans have also highlighted the complaints of machismo, sexism, and especially domestic and sexual violence against women or accusations of violence against children, they are loose propositions as they are not clearly linked to a given approach and may be materialized either in combination with gender and sexuality issues or under a perspective that is conservative and limited to the biological and naturalized bodies of men and women.

Moreover, this mention of human rights and/or respect among and between men and women, except for the brief mention of sexual orientation in Rio Grande do Sul, leaves out any reference to LGBT people, which seems to be the most worrisome target, of reactionary investment, and one of the major topic being disputed.

Rondônia is outstanding example. The plan initially passed had various references to issues regarding LGBT people, sexual orientation, and gender identity. After some time, another act of law passed and all mentions of LGBT issues were withdrawn. The subsequente law targeted exactly the set of items in which the agenda above had been included, however all mentions in relation to promoting women´s rights survived, as they were intended to ensure “starting when the plan will be fully in force, in 100% of schools, preventive actions contained in the school curriculum regarding adolescent pregnancy” (RONDÔNIA, 2015, Goal 2, Item 2.21, our emphasis) and to ensure “policies intended to fight violence in the schools, including by performing actions aimed at training teachers to detect signs of its causes, such as domestic and sexual violence sexual” (RONDÔNIA, 2015, Goal 7, Item 7.12, our emphasis).

This, the ways this group of states addresses human rights, rights to education, the very domestic and sexual violence against women do not absorb the gender relations in the policies of education; more specifically in the state education plans we have examined, gender is concealed when the topic is addressed. This indicates that, despite the mentions of machismo, sexism, or domestic violence, the plans reassert a generalist approach, showing proximity to the same tendency in the National Education Plan. More than that, this group indicates a major setback by taking gender as a synonym of woman or women. It goes back to the essentialist use of the word woman, widely criticized by several feminists, when in turn the concept of gender should exactly problematize this notion. Prevalent in this group is what Judith Butler (1990, 2014) calls heterosexual matrix, that it, man, woman, and family in the propositions contained in these plans have to been seen as the imposition of heterosexuality as the only standard.

Specifying gender as human rights: women, LGBT people (AM, BA, MA, MT, MTS, PA, RR)

These seven states have absorbed the gender perspective quite widely and in detail and they have also acknowledged the sexualities as integral parts of the social role of education and, therefore, it must be included in the laws that organize the policies associated with the access and permanence in the several levels and stages of schooling – including child education, elementary and middle school, in addition to youth and adult education, going as far as the higher education in some states – and in the educational guidelines, in the contents of the school curriculum, and in the basic and/or continued teacher training.

Regarding access and permanence in the several stages and levels of schooling, in order to universalize “school provision to the entire age bracket of 15 to 17 years old”, the state of Amazonas has proposed to implement policies to “prevent school drop-out, withdrawal” motivated by any “prejudice or social, sexual, religious, cultural, and ethnic-racial discriminations” (AMAZONAS, 2015, Goal 3, Strategy 3.11, our emphasis). Therefore, despite using the terms dropout and withdrawal it is clear that giving up study is related to conditions caused by social inequalities, either class, ethnicity/race, gender etc.

Mato Grosso takes the same way and proposes the goal of putting up “affirmative action policies based on research, looking at school census data concerning repetition, school dropout/withdrawal, making a tapestry of gender, color/race, income, and the parents´ schooling level” (MATO GROSSO, 2014, Goal 15, Strategy 1, our emphasis). The mentioned state also recommends to adopt “administrative, pedagogical, and organizational measures required to ensure the students access and permanence in the school with no discrimination based on gender identity and sexual orientation” (MATO GROSSO, 2014, Goal 2, Strategy 33, our emphasis).

In turn, Roraima has strategies that include the guarantee of access and permanence in higher education by “ensuring affirmative action programs for disabled, black, indigenous people and those dwelling in riversides and in forests, with different sexual orientations” (RORAIMA, 2015, Item 5, Strategy 8, our emphasis). The state of Maranhão is quite emphatic by including policies to ensure “access and conditions for permanence” for “gays, lesbians, bisexuals, transvestites, and transsexuals in Elementary and Middle School” (MARANHÃO, 2014, Goal 2, Strategy 2.17, our emphasis).

In a country where the expected life span of a trans person is 35 years and has no systematized records about the exercise of their rights to formal education (MOTT, MICHELS, 2018), such measures, by breaking the silence, bring about rights that have not yet been exercised and indicate that changes are possible, as defines Ball (1989).

Also, regarding the guarantee of access, permanence and academic achievement, Mato Grosso state plan includes that care should be taken about what is called “early pregnancy” in the case of “young girls benefitting from income transfer programs in high-school” (MATO GROSSO, 2014, Goal 9, Strategy 12, our emphasis). Many studies cast doubt on the alleged earliness of pregnancy among young girls and point out that young people utilize many elements to materialize or postpone maternity (OLIVEIRA, 2007), but here it is worth highlighting how important it is that the plan stresses the school responsibility in preventing that such young girls from dropping out from school.

Some plans have a clear mention of gender and sexuality issues in the curriculum. Once again, Maranhão state plan stands out by supporting “the Local Education Authorities in designing, setting up, implementing, and assessing curriculum proposals for Child Education” that respect “gender diversity” (MARANHÃO, 2014, Goal 1, Strategy 1.17, our emphasis), which indicates that “all public policies towards diversity”, including the ones intended to “ensure the rights of blacks, indigenous people, women, people from the LGBTTT segment and others” be “considered in the Political-Pedagogical Projects of the public state schools” (MARANHÃO, 2014, Goal 7, Strategy 7.8, our emphasis).

The Amazonas state plan is even more specific in relation to high-school by including “school curricula that organize, in a flexible and diversified manner, mandatory and optional contents combined in dimensions such as science, labor, languages, technology, culture, sport, education for public traffic, and sexual education” (AMAZONAS, 2015, Goal 3, Strategy 3.1, our emphasis).

Mato Grosso state plan has a strategy to assess quality education by “ensuring that curricular projects be devised in combination with the national common baseline” and related to some aspects including “human rights, genders, sexuality” (MATO GROSSO, 2014, Goal 2, Strategy 13, our emphasis). The state plan also includes the creation of “guidelines for the educational systems to implement actions that substantiate the respect to citizenship and non-discrimination based on sexual orientation” (MATO GROSSO, 2014, Goal 2, Strategy 34, our emphasis).

Regarding the learning materials, the states of Maranhão (2014, Goal 7, Strategies 7.11 and 7.15), Mato Grosso do Sul (2014, Goal 7, Strategy 7.35), and Pará (2015, Goal 7, Strategy 7.34) propose to purchase, produce, and distribute learning materials about human rights, STD/Aids prevention, and issues of gender, sexual orientation, and sexuality intended for education professionals, students, and parents/guardians. When producing learning materials, Maranhão state plan (2014, Goal 7, Strategy 7.11, our emphasis) mentions clearly “gender relations” and “sexual diversity”.

Those states acknowledge that including gender issues and the production of sexualities in the curricula and textbooks is not enough, and highlight how important basic and continued teacher training is. Mato Grosso do Sul (2014, Goal 7, Strategy 7.34) and Pará (2015, Goal 7, Strategy 7.34) have included continued teacher training on “human rights”, “/Aids prevention, alcohol and drug abuse, in its interface with gender and sexuality issues, generation and ethnic-racial issues, situation of disabled people”, with identical readings. Mato Grosso do Sul state plan also includes joint efforts with “public and private higher-education institutions, to provide in their premises or somewhere, continued teacher training courses” on “education and gender” (MATO GROSSO DO SUL, 2014, Goal 16, Strategy 16.2, our emphasis). Bahia state plan (2016, Goal 15, Strategy 15.15, our emphasis) adds the basic teacher training in order to

[...] ensure that issues of cultural, ethnic, religious, and sexual diversity be treated as themes in the curricula [...] under the aegis of the National Education Plan in Human Rights and the National Guidelines for the Education in Humans Rights set forth by the National Education Council.

In the Mato Grosso state plan (2014, Goal 5, Strategy 16, our emphasis), there is a longer reference which indicates the provision of “specific basic and continued training” for education professionals “regarding gender, sexuality and sexual orientation, within the segment of diversity with the aim of fighting sexism and homophobia/lesbophobia/transphobia in the perspective of the human rights”.

Mato Grosso do Sul e Pará state plans show identical reading that also include policies to “prevent and fight violence in the schools” to be implemented and in addition to “domestic and sexual violence” – foreseen by the vast majority of the states as will be seen later – the violence resulting from “gender and sexual orientation issues”, including “capacity-building for education professionals so that they can perform preventive actions with the students in order to detect the causes”. (Mato Grosso do Sul, 2014, Goal 7, Strategy 7.33; PARÁ, 2015, Goal 7, Strategy 7.33, our emphasis).

The bodies of women´s policies are mentioned in three state plans in this group. Maranhão (2014, Goal 7, Strategy 7.3) proposes, in general, to develop partnerships with the “State Department of Human Rights, State Department of Racial Equality, State Department of Women”, while Mato Grosso do Sul (2014, Goal 3, Strategy 3.74) indicates partnerships with bodies such as

[...] State Department of Social Assistance - SEDSS; Social Assistance Reference Center - CRAS; the Public State Attorney-General - MPE; State Department for Women´s Policies - SEPMULHERES; State Department of Justice and Human Rights - SEJUDH; State Department of Humanization; State Health Department - SESACRE to promote women´s rights in order to fight prejudice, violence, and all forms of discrimination.

Mato Grosso state plan (2014, Goal 15, Strategy 5) mentions the support to “innovating projects intended to devise pedagogical proposals suitable to the specific needs of students regarding the knowledge of ethnic-racial, gender, sexuality, and sexual orientation diversities.”

But Maranhão is the only state to envisage “a specialized and multidisciplinary sector or technical team” in the State Education Department and in all the Regional Educational Units para “conduct, follow up, assess, and monitor the activities of education in human rights, of education for the ethnic-racial relations, for gender relations, gender identity and sexual diversity”, thus strengthening “partnerships between public bodies, non-governmental organization, and the social movements’, including “women, feminists, and LGBTTT people” with the purpose of “achieving an education that is non-discriminatory, non-sexist, non-macho, non-racist, non-homophobic, non- lesbophobic, non-transphobic” (MARANHÃO, 2014, Goal 7, Strategy 7.7, our emphasis).

Consistent with the foundations and principles of the Federal Constitution, these documents bespeak the zeal and care towards many aspects associated with the meanings and effects of gender in the relations and in the school contents, as they acknowledge them as fundamental references in the making of the identity of children and young people.

Even though with specificities, each of the plans in this group problematizes the fixed and binary view of opposing male versus female meanings as they include the fight against sexism, machismo, LGBTphobia, a concept that condemns “a form of making it inferior, an immediate consequence of the hierarchy of sexualities, as it also grants heterosexuality a superior status, placing it on the level of what is natural and obvious” (Borrillo, 2001, p. 15). That is to say, the gender agenda is made clear in these plans because they absorb the demands from the LGBT activism – and in many moments they go hand in hand with the feminist and women´s movement demands – perceived in the references to sexual violence, sexual diversity, sexual orientation, and gender identity, as well as in challenging LGBTphobia. Thus, they question the tendency of thinking sexual identities as granted, as basic and universal. Therefore, it can be understood that this group of state plans criticizes more sharply the characteristics held by as naturally masculine or feminine and the biological statements about bodies, behaviors, and skills of women and men and about the social differences, emphasizing the socially defined nature of scientific knowledge.

These mentions help us realize our achievements and be aware of the fact that they have gradually challenged and de-constructed the essentialist conceptions sustained both by the biological determinism and by the Christian religious discourse which (still) guides the notions of woman, mother, man, woman teacher, man teacher, child, childhood, youth, body, sexuality, and family.

Inconclusive conclusions

If there is something we can learn from this and other recent studies, we have conducted is that the place of gender and of the production of the sexualities in the educational policies still remains to be consolidated. It is, therefore, an object under dispute whose unfinished process, necessarily open, is susceptible to the different concepts of education, of the right to access and permanence, to the specific contents with professionals qualified for such.

The different meanings held by the principles of universalization, expansion, and democratization of the access to education found in all state plans examined bespeak the dispute around the possible interaction between gender and the conditions of learning, teaching, adequate funding, acknowledgment, appreciation of the differences in the right to education. The legal text and what is between the lines help us comprehend the potential (of lack thereof) of gender relations and the production of sexualities in every and all state education plan.

The very concept and use of gender is also a matter in dispute. That is, despite the fuss and the impact caused by withdrawing the clear mention of gender in the National Education Plan, over half the state plans, even though in quite different ways, included issues associated with the women´s agenda, under a gender perspective, in its final reading. Several states have committed to fight social discriminations in general and some of them have welcome various dimensions of gender and sexual diversity in different stages and levels of schooling such as child education, basic education, while other states have included secondary school and the education of young and adult people, and a few of them have even mentioned higher education and graduate studies.

Almost one third of the plans clearly state that ensuring access and permanence with quality has to do with Fighting gender inequalities in the administrative, pedagogical, and organizational measures, going from the prevention of the so called Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) and the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (Aids), sexual violence and the violence based on gender and sexual orientation up to including gender and sexuality in the curriculum, in learning/teaching materials, and in the basic and continued teacher training, involving education staff, students, fathers, mothers, and guardians in confronting sexism and LGBTphobia. Some plans also includes the support of women´s policy bodies and even a specialized and multidisciplinary team.

We are then allowed to assume that this affirmative movement is the fruit of a countless achievements by women and LGBT people already mentioned in the beginning of this article. And, in the plans which include the various aspects of addressing gender in this educational policy, gender is deemed in a relational manner, capable of embracing the framework of the social relations, encompassing the dimensions of class, race, ethnicity, and generation in the search for apprehending inequality in its different forms.

On the other hand, the anti-gender discourse and the dispute for passing conservative agendas are clearly expressed in leaving out the term gender and all words associated with it such as woman, man, sexual orientation, sexuality. And also by cutting out and/or restraining the LGBT agenda in several state plans and banning any work on gender and sexuality in the schools, under the claim that “gender ideology” would be harmful for the education of children and youths.

In accord with several aforementioned studies on the matter, we can say that the rhetoric of “gender ideology” has become – as it also holds true in the making of the education state plans – a combination key around which a cluster of groups and individuals were brought together with strategies openly contrary to the advancement of any policy associated with the feminist and LGBT agenda; they have also reiterated, in the very legal text, a perspective that is essentialist, deterministic, cis-heteronormative, and masculinist.

The reactionary agenda was also very clear by including items to refrain or subjugate the approach to these topics under the agreement of the families. The idea that gender may be a threat to the children and their families and the use of the concept in the school seen as an interference by the State onto the parents´ sovereignty in regard of the moral education of their children upholds both the topic being left out and the veto to make use of gender in the schools and its control by the family in order to avoid an alleged ideological indoctrination what would have been put in place by activists, teachers, and political groups.

Even so, the conservative move, at least at the time the education plans went to a vote, counteracts and jeopardize a number of political achievements. If a state bans and other three states nominally exclude mentions of gender of any other terms associated with gender and, instead, include items that may be interpreted as strong restrictions to a free debate of such topics, we have, on the other hand, a group of seven states that take gender and the production of sexualities as far as possible in their education plans.

As a result, if the place of gender and the production of the sexualities has never existed in fact, it is possible to say that “precisely, their particular meanings need to be drawn from the materials we have examined” (SCOTT, 2011, p. 101).

The contradictions in the disputes for power concerning the contribution of gender to the social function of education, therefore, remain. And if this holds true, it should be known that this is not about the simple polarization for or against gender. What is expressed in the documents will also become a tension in the relations between the state plans and the local powers and between such local powers and every and all sphere of the educational system and their respective schools with actions to prevent educative institutions to address gender in the classrooms, as well as actions intended to take the matter forward.

Therefore, even characterized by the polarization in the current context of the gender ideology rhetoric overwhelming the passing of the state education plans between 2014 and 2016, they bring to light conflictive agendas which inevitably arise from the dispute among different and even antagonistic projects.

However, this is only one side of the history that we are about to write, there is not just one single educational project but, instead, a heated dispute. This is a scenario that demands to look closely at the cracks and tensions because they are very important for the struggle to maintain rights.

REFERENCES

ACRE. Decreto de Lei nº 2.965, de 2 de julho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-AC) e dá outras providências. Rio Branco: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

ALAGOAS. Decreto de Lei nº 7.795, de 22 de janeiro de 2016. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-AL) e dá outras providências. Maceió: Governo, 2016. [ Links ]

AMAPÁ. Decreto de Lei nº 1.907, de 24 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-AP) e dá outras providências. Macapá: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

AMAZONAS. Decreto de Lei nº 4.183, de 28 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-AM) e dá outras providências. Manaus: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

ANDRADE, Teresa Cristina Bruno. Dos temas transversais à apropriação/vivência de valores: uma proposta de qualidade socioeducacional. 2004. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) – Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, Marília, 2004. [ Links ]

BAHIA. Decreto de Lei nº 13.559, de 11 de maio de 2016. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-BA) e dá outras providências. Salvador: Governo, 2016. [ Links ]

BALL, Stephen J. La micropolítica de la escuela: hacia una teoría de la organización escolar. Barcelona: Paidós, 1989. [ Links ]

BARBOUR, Rosaline. Grupos focais. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2009. [ Links ]

BORRILLO, Daniel. Homofobia. Barcelona: Bellaterra, 2001. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Brasília, DF: Senado, 1988/2001. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto de Lei nº 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014. Aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação (PNE) e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, n. 120-A, p. 01, 26 jun. 2014. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei n. 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, v. 134, n. 248, 23 dez. 1996. [ Links ]

BUTLER, Judith. Gender trouble: feminism and the subversion of identity. New York; London: Routledge; Champman & Hall, 1990. [ Links ]

BUTLER, Judith. Hablando claro, contestando: o feminismo crítico de Joan Scott. Rey Desnudo – Revista de Livros, Buenos Aires, v. 2, n. 4, p. 31-72, 2014. [ Links ]

CARREIRA, Denise. Igualdade e diferenças nas políticas educacionais: a agenda das diversidades nos governos Lula e Dilma. 2015. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2015. [ Links ]

CASTELLS, Manuel. Ruptura: la crisis de la democracia liberal. Madrid: Alianza, 2017. [ Links ]

CEARÁ. Decreto de Lei nº16.025, de 30 de maio de 2016. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-CE) e dá outras providências. Fortaleza: Governo, 2016. [ Links ]

CONGREGAÇÃO PARA A DOUTRINA DA FÉ. Carta aos Bispos da Igreja Católica sobre a colaboração do homem e da mulher na Igreja e no mundo. Vaticano: [s. n.], 2004. Disponível em: <http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_20040731_collaboration_po.html>. Acesso em: 18 set. 2018. [ Links ]

CORNEJO-VALLE, Mónica; PICHARDO, J. Ignacio. La “ideología de género” frente a los derechos sexuales y reproductivos: el escenario español. Cadernos Pagu, Campinas, n. 50, e175009, 2017. [ Links ]

CORRÊA, Sônia. A “política do gênero”: um comentário genealógico. Cadernos Pagu, Campinas, n. 53, e185301, 2018. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Luiz Antônio. As agências financeiras internacionais e a reforma brasileira do ensino técnico: a crítica da crítica. In: ZIBAS, Dagmar M. L.; AGUIAR, Márcia Ângela. S.; BUENO, Maria Sylvia Simões (Org.). O ensino médio e a reforma da educação básica. Brasília, DF: Plano, 2002. p. 103-134. [ Links ]

DESLANDES, Keila. Formação de professores e direitos humanos: construindo escolas promotoras da igualdade. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2016. [ Links ]

Distrito Federal. Decreto de Lei nº 5.499, de 14 de julho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Distrital de Educação (PDE) e dá outras providências. Brasília, DF: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

ESPÍRITO SANTO. Decreto de Lei nº 10.382, de 25 de julho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-ES) e dá outras providências. Vitória: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Felipe Bruno Martins. Agenda anti-homofobia na educação brasileira (2003-2010). 2011. Tese (Doutorado em Ciências Humanas) – Centro de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2011. [ Links ]

FRIGOTTO, Gaudêncio (Org.). Escola “Sem” Partido: esfinge que ameaça a educação e a sociedade brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: LPP/UERJ, 2017. [ Links ]

GOIÁS. Decreto de Lei nº 18.969, de 22 de julho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-GO) e dá outras providências. Goiânia: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

JOÃO PAULO II. Léxicon de termos ambíguos e discutidos sobre a vida familiar e ética. Vaticano: [s. n.], 2003. [ Links ]

JUNQUEIRA, Rogério Diniz. “Ideologia de gênero”: a gênese de uma categoria política reacionária ou: a promoção dos direitos humanos se tornou uma “ameaça à família natural”? In: RIBEIRO, Paula Regina Costa; MAGALHÃES, Joanalira Corpes (Org.). Debates contemporâneos sobre educação para a sexualidade. Rio Grande: FURG, 2017. p. 25-52. [ Links ]

LOURO, Guacira Lopes. O corpo educado: pedagogias da sexualidade. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 1999. [ Links ]

LOURO, Guacira Lopes. Um corpo estranho: ensaio sobre sexualidade e teoria queer. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2006. [ Links ]

LUNA, Naara. A criminalização da “ideologia de gênero”: uma análise do debate sobre diversidade sexual na Câmara dos Deputados em 2015. Cadernos Pagu, Campinas, v. 50, 2017. [ Links ]

MARANHÃO. Decreto de Lei nº10.099, de 11 de junho de 2014. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-MA) e dá outras providências. São Luís: Governo, 2014. [ Links ]

MATO GROSSO. Decreto de Lei nº 10.111, de 06 de junho de 2014. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-MS) e dá outras providências. Cuiabá: Governo, 2014. [ Links ]

MATO GROSSO DO SUL. Decreto de Lei nº 4.621, de 22 de dezembro de 2014. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-MS) e dá outras providências. Campo Grande: Governo, 2014. [ Links ]

MOTT, Luiz; MICHELS, Eduardo. Mortes violentas de LGBT no Brasil relatório - 2017. Salvador: Grupo Gay da Bahia, 2018. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Elisabete Regina Baptista de. Sexualidade, maternidade e gênero: experiências de socialização de mulheres jovens de estratos populares. 2007. Dissertação (Metrado em Educação) – Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2007. [ Links ]

PARÁ. Decreto de Lei nº 8.186, de 23 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-PA) e dá outras providências. Belém: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

PARAÍBA. Decreto de Lei nº 10.488, de 23 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-PB) e dá outras providências. João Pessoa: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Decreto de Lei nº 18.492, de 24 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-PR) e dá outras providências. Curitiba: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

PERNAMBUCO. Decreto de Lei nº 15.533, de 23 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-PE) e dá outras providências. Recife: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

PIAUÍ. Decreto de Lei nº 6.733, de 17 de dezembro de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-PE) e dá outras providências. Teresina: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

PRADO, Marco Aurélio Maximo; CORRÊA Sonia. Retratos transnacionais e nacionais das cruzadas antigênero. Psicologia Política, São Paulo, v. 18, n. 43, p. 444-448, 2018. [ Links ]

REIS, Toni; EGGERT, Edla. Ideologia de gênero: uma falácia construída sobre os Planos de Educação Brasileiros. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 38, n. 138, p. 9-26, jan./mar, 2017. [ Links ]

RIO GRANDE DO NORTE. Decreto de Lei nº 10.049, de 27 de janeiro de 2016. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-RN) e dá outras providências. Natal: Governo, 2016. [ Links ]

RIO GRANDE DO SUL. Decreto de Lei nº 14.705, de 25 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-RS) e dá outras providências. Porto Alegre: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

RONDÔNIA. Decreto de Lei nº 3.565, de 3 de junho de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-RO) e dá outras providências. Porto Velho: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

RORAIMA. Decreto de Lei nº 1.008, de 3 de setembro de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-RR) e dá outras providências. Boa Vista: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

ROSADO-NUNES, Maria José Fontelas. A “ideologia de gênero” na discussão do PNE: a intervenção da hierarquia católica. Horizonte, Belo Horizonte, v. 13, n. 39, p. 1237-1260, jul./set. 2015. [ Links ]

SANTA CATARINA. Decreto de Lei nº 16.794, de 14 de dezembro de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-SC) e dá outras providências. Florianópolis: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (Estado). Decreto de Lei nº 16.279, de 8 de julho de 2016. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-SP) e dá outras providências. São Paulo: Governo, 2016. [ Links ]

SCOTT, Joan Wallach. Género: todavía una categoría útil para el análisis. La Manzana de la Discordia, Calli, v. 6, n. 1, p. 95-101, ene./jun. 2011. [ Links ]

SCOTT, Joan Wallach. Gênero: uma categoria útil para a análise histórica. Educação & Realidade, Porto Alegre, v. 20, n. 2, p. 71-99, jul./dez. 1995. [ Links ]

SERGIPE. Decreto de Lei nº 8.025, de 4 de setembro de 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-SE) e dá outras providências. Aracajú: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

SILVA, Amanda; CÉSAR, Maria Rita de Assis. A emergência da “ideologia de gênero” no discurso católico. InterMeio, Campo Grande, v. 23, n. 46, p. 193-213, jul./dez. 2017. [ Links ]

TOCANTINS. Decreto de Lei nº 2.977, de 8 de julho 2015. Aprova o Plano Estadual de Educação (PEE-TO) e dá outras providências. Palmas: Governo, 2015. [ Links ]

VIANNA, Cláudia Pereira; UNBEHAUM, Sandra. Contribuições da produção acadêmica sobre gênero nas políticas educacionais: elementos para repensar a agenda. In: CARREIRA, Denise et al. (Org.). Gênero e educação: fortalecendo uma agenda para as políticas educacionais. São Paulo: Ação Educativa: Cladem: Ecos: Geledés: Fundação Carlos Chagas, 2016. p. 55-120. [ Links ]

VIANNA, Cláudia Pereira; UNBEHAUM, Sandra. Gênero na educação básica: quem se importa? Uma análise de documentos de políticas públicas no Brasil. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 28, n. 95, p. 407-28, maio/ago. 2006. [ Links ]

VIANNA, Cláudia Pereira; UNBEHAUM, Sandra. O gênero nas políticas públicas de educação. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 34, n. 121, p. 77-104, 2004. [ Links ]

VIANNA, Cláudia Pereira. Políticas de educação, gênero e diversidade sexual: breve história de lutas, danos e resistências. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2018. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, Evaldo. Os direitos sociais e a política social. São Paulo: Cortez, 2007. [ Links ]

3- The acronym LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transvestite, Transsexual, and Transgender), here adopted, complies with the deliberation of 1st National LGBT Conference, held in 2008. It is known, however, that the acronym is not sufficient to encompass the multiple forms of sexual and gender expression and identification. It is utilized, therefore, in more broadly to include a variety of gender identities (transvestites, transsexual and transgender persons, no binary, agender, queer) and the sexuality identities (homosexual, bisexual, pansexual, asexual persons), as we are aware that this is a process that is in permanent construction.

4- Lexicon is a document prepared by the Catholic Church against the feminist agenda that advocates for needs of reproductive health intertwined with other social and individual rights.

5- The Movement Brazil Free (MBL) emerges in the demonstrations held in Brazil in 2014 in protest against former president Dilma Rousseff (of the Workers´ Party), with agendas associated with fighting corruption and economic liberalism. It occupies an important place in disseminating conservative agendas such as: reducing legal age, right to abortion, same-sex marriage, and the instrumentalization of schools by what they call “gender ideology”. For example, it is the MBL who publicly calls for demonstrations against the exhibit Queermuseum in the city of Porto Alegre (2017) or the coming of philosopher Judith Butler (2017) for an event in São Paulo.

6- ESP was created in 2004 by lawyer Miguel Nagib, attorney-general for the State of São Paulo, and is presented as a “joint initiative of students and parents worried with the degree of political-ideological contamination in the Brazilian schools” (http://escolasempartido.org/quem-somos). Research has shown that it is a movement intended to attack and censor historical-social criticism in the schools, a reactionary combination that attributes feminist and LGBT policies to the “left wing”, with the purpose of simultaneously expurgate “cultural Marxism” and “gender ideology” from the educational policies and school practices (FRIGOTTO, 2017).

7- The characterization of “gender ideology” as a sintagma is done by Rogério Junqueira (2017) to highlight its lack of conceptual accuracy and its use strongly intended to cause moral panic.

Received: March 25, 2019; Revised: August 20, 2019; Accepted: October 01, 2019

texto en

texto en