INTRODUCTION

Binge drinking consists of an alcohol consumption pattern that is dangerous for the drinkers and for the society. In 2004, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism defined binge drinking based on the minimum number of doses consumed by women (four doses) and men (five doses), during a two-hour interval, a volume that is able to bring one’s blood alcohol level to at least 0.08 g/dL1.

Excessive alcohol consumption is a problem, especially among individuals of college age. Cultural, social, and developmental factors are featured in transition from youth to adulthood and are potentially influenced by the college environment. College attendance increases the risk of binge drinking as a common practice. In this situation, college students experience alcohol use disorders (AUD) that, in turn, result in physical, emotional, social, cognitive and legal consequences2.

Undergraduate medical courses shown certain features, such as high workload and medical content, which may affect medical students’ quality of life. During the learning phase, medical students are often exposed to stressful situations that may lead to depression and anxiety manifestations3. Under these conditions, they are at risk to start using psychoactive drugs or alcohol or maintaining their previously initiated habits3. It has been reported, for example, that negative internal motivations induce alcohol abuse as a coping mechanism in almost 20% of medical students at five Korean medical schools4. A study that investigated psychoactive drug use in four medical schools in Rio de Janeiro estimated a 19.8% prevalence of alcohol abuse and warned that such behavior could be a coping strategy to deal with the medical school demands5.

By acknowledging a propensity for psychoactive substance use, including alcohol abuse, during the undergraduate medical education period3, we believe that a national estimate can aid in understanding the magnitude of binge drinking in Brazil, thereby encouraging the implementation of preventive measures, involving Brazilian universities. No meta-analysis addressing the prevalence of binge drinking among medical students in Brazil is, however, available. In this context, the aim of this study was to estimate the pooled prevalence of binge drinking practiced by Brazilian medical students.

METHODS

A systematic review and meta-analysis was designed to answer the research question, phrased in the PICO format6, (P = population or medical condition; I = intervention or exposure; C= comparison; O = outcome): “What is the prevalence (O) of binge drinking (E) among medical students in Brazil (P)?”

This review protocol was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under CRD number 42019138036. Database consultation started in January and ended in June 2020, with a final update performed in June 2021. This systematic review followed the Guidelines for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses7 and was carried out according to the Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews-2 (AMSTAR2)8.

Information sources and search strategies

The searches were performed at the PubMed/Medline (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online), SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online) and LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences) databases. The search strategy included terms in both English and Portuguese and was guided by combinations such as ((binge drinking [All Fields]) OR (alcoholic intoxication [All Fields]) OR (alcoholism [All Fields]) AND (students, medical [All Fields] Fields]) AND (Brazil [All Fields])) at the Medline database via PUBMED, (binge drinking [Words] OR alcoholism [Words] AND medical students [Words]) at LILACS and (binge drinking [All Indices]0 OR (intoxication) alcoholic [All ratings] OR (alcoholism[All ratings]) AND (medical students [All ratings]) and (Binge Drinking [All ratings]) OR (Alcoholic intoxication [All ratings]) OR (Alcoholism [All indices] AND (Medical students) at the SciELO database, in both Portuguese and English. To address gray literature, the first 200 Google Scholar records were searched using a more flexible search strategy. To complete the search, the reference lists of articles read in full were also screened, and e-mail messages were sent to experts in the alcoholism area asking for non-retrieved records.

Eligibility Criteria

As the primary result for this review comprised the prevalence of binge drinking practiced by medical students, the inclusion criteria for the primary studies were based on providing (i) the absolute number of students participating in the study; and (ii) the absolute number of students practicing binge drinking. When necessary, the authors were contacted to obtain data not directly available in the published articles.

Studies addressing medical students along with students from other health area careers or undergoing medical treatment, and those that measured binge drinking using a definition not consistent with the pattern based on the number of alcohol doses were excluded from the analysis.

Data collection and variables of interest

Two researchers were responsible for the study selection and data extraction, which were carried out independently. Data selection was performed in two stages, initially by reading the titles and abstracts and, later, by full article reading. Disagreements observed at any stage were solved by consensus. The entire process was supervised by a third researcher, whose opinion settled any inconsistencies and disagreements. The searches were not restricted by language.

We selected data from the study identification (author, year, journal), medical school characteristics (administrative category, location), student features (gender, course period, alcohol use patterns) and measurement instruments. All data were recorded in a form created specifically for this study.

Quality assessment of the included studies

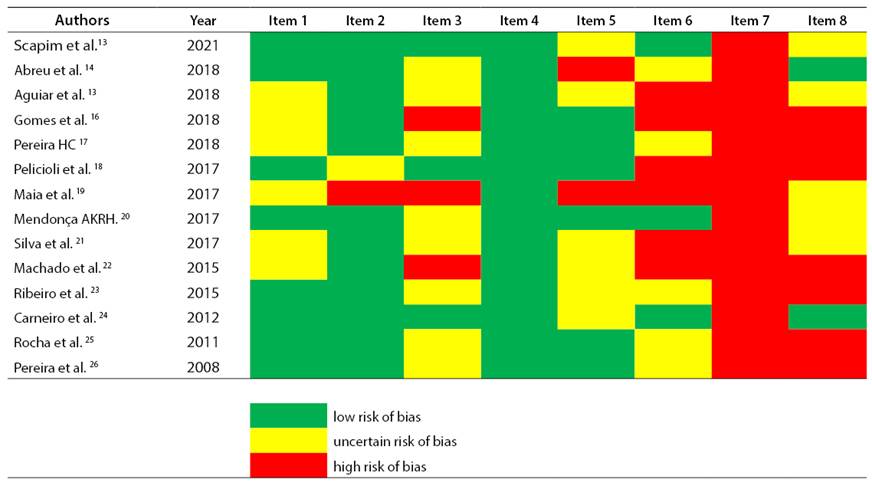

Quality assessment followed the criteria developed by Loney et al (1998) to specifically assess incidence and prevalence studies9. This questionnaire consists of eight items and the total score ranges from zero to eight. The same reviewers also independently performed the quality assessment of the selected studies.

Statistical analyses

The procedures for obtaining summary measures via random effects models, in addition to fixed effects modeling, were employed using the metaprop package10. Metaprop is designed to develop a proportion meta-analysis and 95% confidence intervals (CI) using the R Platform, version 4.0.3, following a hands-on tutorial11.

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by Cochran’s Q statistic, interpreted via chi-square statistics and p values (5% significance level). The I2 statistic provides the degree of inconsistency among studies and was used as recommended by Higgins et al (2003)12 to obtain the proportion of the total variation not attributed to chance. The measure ranges from 0 to 100% and was interpreted considering cutoff points of 25% (small), 50% (moderate) and 75% (high).

Assuming sex-differentiated binge drinking behaviors, additional sex-stratified meta-analyses were conducted. Possible heterogeneity sources were assessed by analyzing subgroups considering medical school features (location and administrative category), as well as the year of study publication (up to 2015 and after 2015).

The effect of publication bias was evaluated by constructing and interpreting a funnel graph and by Egger’s test, using the metabias command available in the R Platform.

RESULTS

Study selection and inclusion

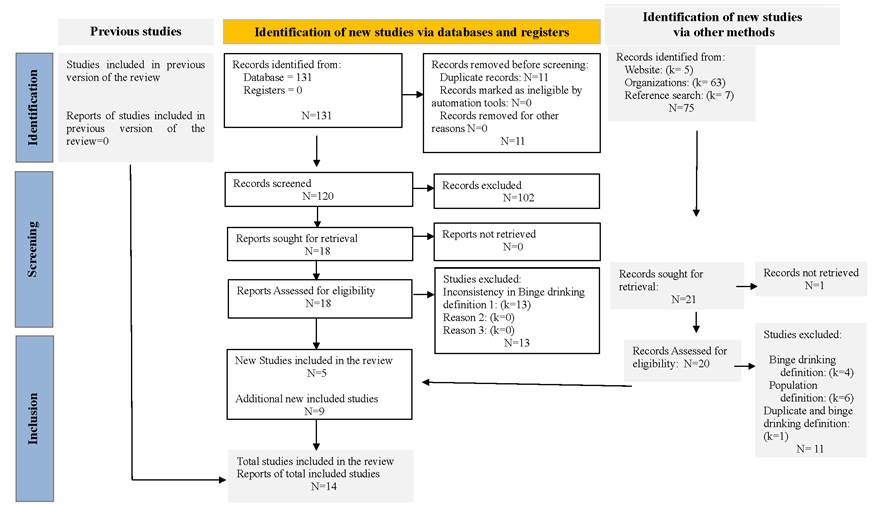

This review identified 206 publications using the search strategy at the MEDLINE (n=72), LILACS (n=26), SCIELO (n=33) and CAPES thesis and dissertation (n=63) databases and following a manual search in the reference lists (n=7) and at other sources, such as Google Scholar (n=5). After excluding duplicates (n=11), ineligible publications (n=156) were discarded according to their titles and abstracts. Complementary reading was indicated for 39 selected texts, but one could not be retrieved, despite requests to the author. Of the retrieved studies, 24 were excluded due to the following reasons: alcohol use definition incompatible with binge drinking (n=18) or incompatibility of the study population (n=6). A total of 14 publications were analyzed in the subsequent steps of this review (Figure 1).

The studies included in this review were conducted in the North (n=1), Northeast (n=4), Southeast (n=7) and South (n=2) regions of Brazil. Together, the studies analyzed 4,256 medical students. The sample size ranged from 111 to 571 students, with six studies reporting over 300 participants, five studies assessing a sample size from 200 to 300 and only three studies reporting the participation of fewer than 200 students. Students were enrolled in educational institutions located in the state capital (n=5), state interior (n=8) and in both locations (n=1). Regarding binge drinking prevalence, a considerable variation in frequencies reported in the selected studies were individually noted, ranging from 19% (13%; 26%)26 to 74% (70%; 78%)24. This indicates the need for the implementation of more in-depth assessments in this regard. Despite the importance of epidemiological measures stratified by sex, the frequencies of binge drinking in men and women were provided in only six studies (Table 1).

Table 1 Synthesis of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Identification | Higher Education Institution | Methodological characteristics | Prevalence of binge drinking | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors/ Year | Administration type | Location | Region | Design | Tool | Course semester | Students (n) | Total (%) | Male sex (%) | Female sex (%) |

| Scapim et al; 202113 | Public | Capital | Northeast | Cross sectional | VIGITELa | from 1st to 8th | 556 | 36.0 | 39.0 | 32.0 |

| Abreu et al; 201814 | Public | Interior | Southeast | Cross sectional | AUDITb | from 1st to 10th | 201 | 53.7 | 69.6 | 40.4 |

| Aguiar et al; 201815 | Public | Both | Southeast | Cross sectional | AUDIT | 3rd, 6th and 11th | 371 | 60.1 | NAc | NA |

| Gomes et al; 201816 | Private | Interior | Southeast | Cross sectional | AUDIT | from 1st to 8th | 265 | 48.7 | 58.9 | 42.9 |

| Pereira HC; 201817 | Public | Interior | Northeast | Cross sectional | AUDIT | from 1st to 12th | 281 | 48.8 | NA | NA |

| Pelicioli et al; 201718 | Private | Interior | South | Cross sectional | AUDIT | NId | 111 | 68.5 | NA | NA |

| Maia et al; 201719 | Private | Capital | Northeast | NI | AUDIT | from 1st to 8th | 291 | 48.8 | 61.4 | 36.3 |

| Mendonça AKRH; 201720 | Both | Capital | Northeast | Cross sectional | AUDIT | from 1st to 12th | 210 | 55.2 | NA | NA |

| Silva et al; 201721 | Private | Interior | South | Cross sectional | AUDIT | from 1st to 12th | 343 | 63.6 | 73.7 | 59.7 |

| Machado et al; 201522 | Both | Interior | Southeast | Cross sectional | AUDIT | from 1st to 8th | 146 | 41.1 | NA | NA |

| Ribeiro et al; 201523 | Public | Capital | North | Cross sectional | AUDIT | from 1st to 12th | 306 | 27.8 | NA | NA |

| Carneiro et al; 201224 | Private | Interior | Southeast | Survey | AUDIT | from 1st to 8th | 436 | 74.1 | 82.4 | 68.1 |

| Rocha et al; 201125 | Both | Interior | Southeast | Cross sectional | AUDIT | from 1st to 8th | 571 | 21.7 | NA | NA |

| Pereira et al; 200826 | Public | Capital | Southeast | Cross sectional | WHOe | from 1st to 12th | 168 | 19.0 | NA | NA |

aVIGITEL - Vigilância de Fatores de Risco e Proteção para Doenças Crônicas por Inquérito Telefônico.

bAUDIT - Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. cNA - Not Applicable. dNI - Not Informed.

eWHO - World Health Organization.

Qualitative aspects of the included studies

In general, some data regarding the sampling procedures were not provided in detail. The mean score of the selected studies was 4.5 points, ranging from 2 to 6.5. No study obtained the maximum score (8 points). The best-scoring item concerned the use of a validated measuring instrument, which was positively reported in all 14 studies. On the other hand, item 7, concerning the confidence intervals of the prevalence measures, exhibited the worst scores, given the absence of this information in all included studies. Furthermore, no publications reported financial support or funding sources, with the exception of the Espírito Santo Research Support Foundation (FAPES), cited by Pereira et al (2008)26. Finally, a declaration on conflicts of interest statement was reported by seven13)-(16),(18),(24),(25) studies, but was not even mentioned by the authors of the remaining investigations (Chart 1).

Combined binge drinking prevalence

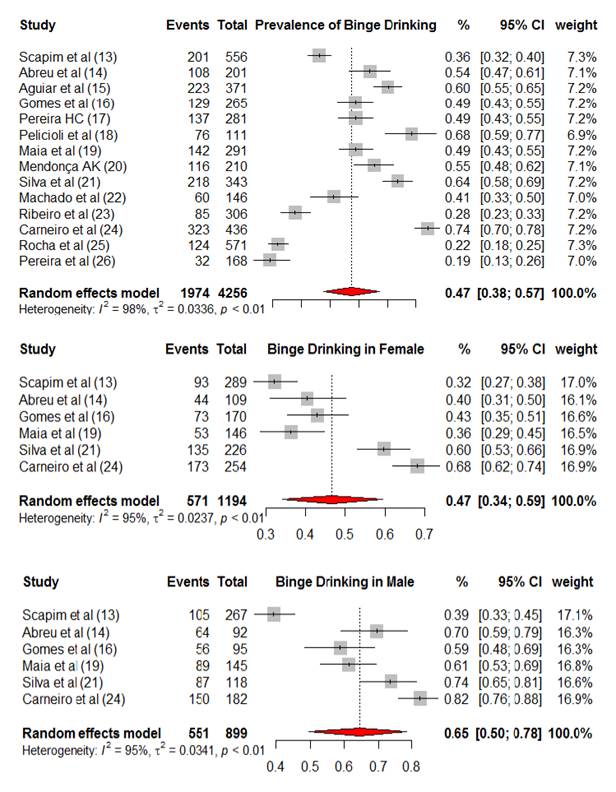

As we expected statistical (and clinical) heterogeneity to be high, the combined binge drinking prevalence was estimated by the random effects method. The pooled analysis of all 14 studies indicated that binge drinking is practiced by 47% of medical students in Brazil (95% CI: 38%; 57%), reaching a pooled prevalence of 65% among men (6 studies, 95% CI: 50%; 78%) and 47% among women (6 studies, 95% CI: 34% to 59%) (Chart 2).

Heterogeneity analysis

The meta-analysis with all the 14 studies exhibited high statistical heterogeneity (I2: 98.00%; p<0.01), as well as for the 6 studies that included only men (I2: 95.00%; p< 0.001) and only women (I2: 95.00%; p<001). Subgroup analyses showed variations according to previously postulated characteristics, such as year of publication (before or after 2015), medical school administration type (public or private), location (capital or interior) and country region (North, Northeast, Southeast, South or Midwest). A high heterogeneity persisted when assessing the different features, suggesting considerable inconsistencies between studies and not a mere chance effect (Table 2).

Table 2 Analysis of subgroups considering 14 studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Subgroups | Publication (n) | Prevalence | 95% Confidence Intervals | I2 Statistics | P value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | |||||

| North | n=1 | 28.00 | 23.00; 33.00 | NAb | <0.01 |

| Northeast | n=4 | 47.00 | 38.00; 56.00 | 90.00 | <0.01 |

| Southeast | n=7 | 45.00 | 28.00; 63.00 | 98.50 | <0.01 |

| South | n=2 | 65.00 | 60.00; 69.00 | NA | <0.01 |

| Location | |||||

| Capital | n=5 | 37.00 | 26.00; 49.00 | 95.20 | <0.01 |

| Interior | n=8 | 52.00 | 38.00; 67.00 | 98.10 | <0.01 |

| Both | n=1 | 60.00 | 55.00; 65.00 | NA | <0.01 |

| Type of administration | |||||

| Public | n=6 | 41.00 | 29.00; 53.00 | 96.50 | <0.01 |

| Private | n=5 | 61.00 | 50.00; 71.00 | 94.40 | <0.01 |

| Both | n=3 | 39.00 | 18.00; 62.00 | 97.60 | <0.01 |

| Year/publication | |||||

| After 2015 | n=9 | 54.00 | 47.00; 60.00 | 92.20 | <0.01 |

| Up to 2015 | n=5 | 37.00 | 16.00; 60.00 | 98.90 | <0.01 |

aQ Test of Cochran. bNot Applicable.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review sought to provide a more accurate scenario concerning the prevalence of binge drinking among medical students in Brazil. The pooled measure suggests that almost half (47%) of these students consumes alcoholic beverage amounts above the acceptable limit within a short period of time. This practice is more prevalent in men (65%) than in women (47%). In addition to the reverse causality that underlies the relationship between alcohol consumption and mental health, binge drinking may lead to a substantial risk of injuries, such as accidents and violence. This, in turn, leads to acute and chronic effects on both individual and collective health, with potential risks for disability and death.

In the United States, a survey conducted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) estimated that 29.6% of adults aged 18 to 22 practiced binge drinking in the thirty days prior to the data collection27. Another study reported a 58.1% binge drinking prevalence in a sample comprising 485 students from the Georgetown University School of Medicine28. In France, the prevalence measured in the 15 days prior to data collection was 74.8% and involved 302 students29. Data from five medical schools from Korea reported 56% of binge drinking, showing that this behavior was observed throughout all years of the medical course4.

Tobacco use, mental disorders, drug use and coping strategies to face day-to-day problems are linked to alcohol abuse among medical students28),(29. Regarding binge drinking, some studies associated it to other situations experienced in medical school, such as lower test grades13, attending a more advanced medical course phase13),(14),(16 and poor school performance19),(21. These studies suggest that factors inherent to the medical school environment may motivate medical students to engage in binge drinking in Brazil.

Studies regarding alcohol use and mental health among medical students are not rare in Brazil. For example, a recent systematic review30 aiming to provide a comprehensive picture of mental disorders concluded that problematic alcohol use occurs in 32.9% of medical students, while depression is observed in 30.6%, common mental disorders in 31.5%, burnout in 13.1%, suicidal ideation in 13.4% and poor sleep quality, in 51.5%. The studies included in this review reported a prevalence of 21.17% of common mental disorders17, 3.59% of addiction patterns detected by the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)23) and 10.0% of excessive consumption with recommendations to stop drinking22 among binge drinking students. Medication use was also mentioned21, as well as experimentation with solvents, cannabis sativa, amphetamines and anxiolytic drugs26.

Binge drinking behavior is still poorly studied, despite the negative potential it may bring to human health. This makes this meta-analysis at the very least, timely, comprising one of the strengths of this study, in addition to the use of a comprehensive search strategy that also includes gray literature. Furthermore, this review, in addition to providing insights into the magnitude of binge drinking, was based on an objective binge drinking definition and included studies that measured alcohol intake by the number of consumed doses. However, Heavy Alcohol Use (more than 3 drinks on any day or more than 7 drinks per week for women, and 4 drinks on any day or more than 14 drinks per week for men) and High-Intensity Drinking (consumption of 2 or more times the gender-specific thresholds for binge drinking) are emerging trends27 that are even less often studied than binge drinking, indicating the need for future assessments.

A high heterogeneity among the studies was noted in the present meta-analysis, involving all studies (n=14), as well as data for men (n=6) and women (n=6), separately. As foreseen in the review protocol, subgroup analyses were performed, but due to the low number of publications stratified by sex, the subgroups were assessed only considering all 14 studies.

The parameters provided for the subgroup analysis, in addition to expressing decreased precision due to the stratification, were not sufficient to explain part of the observed statistical heterogeneity. The prevalence reported in individual studies ranged from 19.0%26 to 74.1%24. Thus, other clinical and/or methodological issues not directly reported in the publications may comprise possible unmeasured heterogeneity sources. Moreover, Brazil is a continental country with great differences experienced by the population groups from its five geographic regions. It may partially explain the variability of prevalence measures, comparing to those found in other countries.

In addition to the unexplained heterogeneity, other limitations for this systematic review are also noted. First, despite the extensive search including gray literature, few studies were obtained, and sample sizes were relatively small. Furthermore, students might not have been sincere when answering the questionnaires, possibly underestimating binge drinking rates.

Publication bias was verified by inspecting the funnel plot and evaluating Egger’s test. Although graph symmetry assessments may be inaccurate for extreme proportions, this is a valid approach in the case of measurements around 0.5031. Thus, the symmetrical distribution of the studies and the rejection of the null hypothesis that the results might be expressing due to the effect of the absence of small studies, suggest that the estimated parameters are free from publication bias.

CONCLUSIONS

Binge drinking is practiced by almost half of our future physicians. These results provide insights as to the choices and decisions that these students make regarding the consumption of potentially dangerous substances for human health. Despite the high heterogeneity, the magnitude of binge-drinking problem estimated in this meta-analysis demands an effective involvement of medical schools in Brazil, by counseling and other actions to prevent the harmful consequences for medical students and society.