Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.22 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 07-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v22-2023-149

Dossiê 1 - História da formação e do trabalho de professoras e professores de escolas rurais (1940-1970)

Reflections on the processes of feminization and professionalization of the Mexican rural teaching profession in the period of National Unity1

1El Colegio de San Luis (Mexico). oresta.lopez@colsan.edu.mx

During the Government of Manuel Ávila Camacho (1940-1946), a National Unity policy was promoted, which called for internal agreements in order to strengthen the State in the context of World War II. For rural education it meant an important turn to National conservatism, a setback in the reformist, socialist, feminist and agrarian policies of the Cardenista period. In this article, the background and educational challenges of professionalization of rural teaching are analyzed. Also, the unionization controlled by the State is made visible as well as the precariousness and feminization of teachers. In this context, female teachers in rural areas were fundamental for literacy and pacification of the country. In this regard, data on the feminization of rural teaching is provided, such as analytical frameworks in order to understand these processes in the light of national unity ideologies; and teachers’ narratives, recovered from their personal files, which demonstrate the implementation of these policies in the lives of female teachers of rural areas, as well as their resistance to such policies.

Key words: Feminization; Professionalization; Gender; Education

Durante el gobierno de Manuel Ávila Camacho (1940-1946), se impulsó una política denominada como de Unidad Nacional, en nombre de la cual se impusieron acuerdos internos para fortalecer al Estado, en el contexto de la 2ª. Guerra Mundial, a la que México se sumó. Para la educación rural significó un giro importante a la derecha, un retroceso en las políticas reformistas, socialistas, feministas y agraristas del periodo cardenista. En el presente artículo se analizan los antecedentes y los desafíos educativos de profesionalización del magisterio rural y se hace visible la sindicalización controlada por el estado, así como la precarización y feminizacion de este gremio, siendo las maestras rurales fundamentales para la alfabetización y la pacificación rural del país. En este sentido se aportan datos duros de la feminización del magisterio rural; marcos analíticos para comprender estos procesos, en la coyuntura de la ideología de la unidad nacional y narrativas que demuestran la aplicación de estas políticas en las vidas de las maestras rurales, y sus resistencias a tales políticas.

Palabras clave: Feminización; Profesionalización; Genero; Educación

Durante o governo de Manuel Ávila Camacho (1940-1946), foi promovida uma política denominada Unidade Nacional, em nome da qual se impuseram acordos internos para fortalecer o Estado, no contexto da 2ª. Guerra Mundial, à qual o México aderiu. Para a educação rural, significou um importante deslocamento à direita, um retrocesso nas políticas reformistas, socialistas, feministas e agrárias do período cardenista. Neste artigo, analisam-se os antecedentes e os desafios educacionais da profissionalização do magistério rural e dá visibilidade à sindicalização controlada pelo Estado, bem como a precariedade e feminização desse grêmio, sendo os professores ds escolas rurais considerados fundamentais para a alfabetização e pacificação do país. Nesse sentido, temos dados concretos sobre a feminização da educação rural; referências analíticas para compreender esses processos em conjunto com a ideologia da unidade nacional e narrativas que demonstram a aplicação dessas políticas na vida das professoras rurais e suas resistências a essas políticas.

Palavras-chave: Feminização; Profissionalização; Gênero; Educação

This paper examines the transformations in the professionalization of Mexican rural teachers, focusing on the training and professionalization of rural teachers in the period known as national unity and the “school of love”. This period (1940-1946) in the History of Mexico, led by President Manuel Ávila Camacho, was characterized by right-wing nationalism for promoting a narrative of national reconciliation and for backtracking on the Cardenista Educational Policy.

Subsequently, more systematic State actions in the construction of a modern educational system were identified under the administration of Jaime Torres Bodet at the head of the Ministry of Education (SEP).

Thus, in the name of national unity, during the first three years of the 1940’s, the agrarian reformed was stopped, which resulted in benefits for small property and to detriment of communal land for agriculture (ejido). Socialist education stopped being promoted and education was oriented towards industrialization and job training. For the second triennium, intense mass literacy campaigns were launched and private education was promoted. In addition, by joining the alliance in World War II, Mexican companies were supported for the productions of manufactures, generating business ideas that did not have the expected impact. After ten years of having a new Law of Ranking Promotion for Teachers, a more demanding regulation on teachers’ training was not enough, but the need for State strategies to meet the training demands of in-service teachers was evident. At the same time, new job insecurity for teachers is noticed, in the context of narratives of glorification of motherhood at a time of unstoppable process of feminization of the teaching profession. Both processes, -the extension of mass education and the feminization of the teaching profession-, revealed clear asymmetries that confirm the differences in terms of opportunities and salaries of the urban and rural teaching profession.

The establishment of new policies for the professionalization of rural teachers eliminated coeducation in the rural Normal Schools, and also the National Institute of Teacher Training was opened as part of the new strategies to certify the so-called empirical teachers.

The entry of Mexico to World Wat II brought about changes in schools, they became more segregated and the process of feminization of the teaching profession was even more stratified, regressing to previous representations of sexual division of educational work. In this context, militarization of schools and pronatalist policies for women were imposed.

The Cardenista Reforms as an important precedent

Some authors recognize that the period of Plutarco Elías Calles aimed at formulating an educational model in accordance with reformist approaches of the Mexican Revolution. The reform of Article III in 1934, promoted by President Cárdenas and elaborated by his Minister of Education, Narciso Bassols, was in favor of socialist education since it was believed it should not only be secular but radical and committed to society.

The presence of anticlerical revolutionaries and communists in the Ministry of Education (SEP) as well as the socialist education project were widely criticized by the press, some right-wing associations, teachers and parents’ associations, the National Action Party (PAN), and the Catholic Association of Mexican Youth (ACJM).

All this happened because the project aimed to prepare new generations of Mexicans for the control of means of production and for an education not only socialist but also cooperative and free from fanatism. Clerical education was prohibited and those who bent this rule were punished with administrative and economic sanctions.

Bassols, Minister of Education, became the target of criticism because he was in charge of important reforms. He promoted social education and a new Law of Ranking Promotion for Teachers which established completed elementary education as a requirement. This law affected many teachers badly so they protested through their union representatives demanding justice for their work and experience at the founding moments of the Ministry of Education (SEP).

On the other hand, a step forward was taken by improving salaries, making them equal for female teachers and male teachers, and by authorizing a permit for “pregnant teachers” known as “permiso para maestras encintas”. This benefit aroused controversy in communities and supervisors who frequently dismissed pregnant teachers. If that were not enough, Bassols also launched the sex education project. He was ahead of his time by pointing out the need to give students scientific notions about something as basic as the biological reproduction of living beings. This educational proposal ignited the Catholic opposition and it caused violent reactions against rural teachers in various entities of the country.

Unlike the reforms promoted by Vasconcelos in the founding years of the Ministry of Education (SEP), which had broad social support, in the thirties, the officials had to face the effects of the Cristero Rebellion, which led to a large number of human losses, including those of the teachers sacrificed in this absurd war, as pointed out (Meyer, 2002) and other authors. The Cristero Rebellion showed the anger of a social Catholicism which wanted to intervene in public power and use arms to combat State reforms that affected it influence.

Thus, pedagogical training of rural teachers continued in the Normal Schools, and also in the itinerant and seasonal Cultural Missions, which offered teacher training courses.

One of the most common errors that have been pointed out in this period is the ideological indoctrination of socialist education that was imposed on teachers. Even if they did not understand it, they had to sign confusing letters of ideological declaration against “fanatical practices” and total adherence to socialist education. (See figure 1. Ideological declaration format).

However, the rural education model was strengthened during the Cardenismo, since many of the projects initiated by Vasconcelos and Moisés Sáenz were continued. The number of rural schools and rural regional schools was multiplied to improve the conditions of the peasantry.

It was at the end of the Cárdenas government that the support for the itinerant Cultural Missions decreased, then they were incorporated into the Rural Regional Schools due to the social expectations they created in the towns.

In the general balance of this period, it is known that Cárdenas founded 4869 federal elementary schools. However, the efforts of the federation were not supported by the State governments, since at the end of his presidency there were 457 fewer schools than at the beginning of his administration. (Meneses, 2000; 227).

President Cárdenas received a polarized country amid the Cristero Rebellion. Despite the fact that he had great popular support, especially from teachers, he gradually softened his ideas as he received much criticism and opposition from conservative sectors from Mexico and from The United States. In addition, union organizations of teachers were polarized and had conflicting positions regarding the Socialist Education Reform.2

Undoubtedly, the ideological differences within the government during this period became visible as well as the polarization of ideas that led to violent expressions and altercations in different parts of the territory. There were also good practices and successful cases in the implementation of the educational reform in some regions.

The National Unity Policy

President Manuel Avila Camacho established the narrative of national unity on the political stage, with a view to confronting the division and polarization of social classes as well as the disagreements with the church caused by previous governments. His first Minister of Education, Sánchez Pontón, did not meet the expectations to face socialist education. It was his second minister of education, Octavio Véjar Vázquez, who immediately announced the cancellation of the Socialist Education Reform, as well as the active incorporation of the private sector in education and declared his resolution to fight radical and communist groups in the positions of the Ministry of Education (SEP), including teachers, administration positions and unions. The aim was also to promote the integration of the unions.

For the President, the first and most important action was to reorient national education in order to promote a “school of love based on nation-building” and to stop encouraging hatred through a school influenced by “strange influences”.

Thus, unity became the most important topic, and the development of anticommunist feelings favored the idea that teachers should not get involved in politics and devote themselves exclusively to teaching. This new perspective clashed with the model of teachers promoted by Vasconcelos, who had called teachers to carry out social work in the communities. Under the leadership of Vasconcelos, teachers were expected to be committed to the well-being of communities by promoting organization among them in order to address issues such as the agrarian reform, democratization and modernization of forms of agricultural production, and the elimination of cacicazgos. They even had to confront priests and landowners (hacendados) if necessary.

The new policy of “national unity” meant right-wing nationalism (Meyer, 2002) by promoting greater productivism in favor of religious beliefs and cooperation with the private sector. Thereafter, between 40 and 50 per cent of the government expenditures were invested in basic infrastructure which favored the operation of the private sector. The production of oil, electricity and the road network increased. Hydraulic infrastructure for agricultural irrigation was also promoted, as well as investment in aviation and telephone communication (Meyer, 2002; 894). Political elite was unified to modernize the national economy with a view to preparing for the impact of World War II, which implied adjustments in the internal and external markets. Thus, a new business elite emerged. Their interests were focused on industry, finance and commerce. For Carlos Monsiváis, the Avilacamachista narrative of national unity shows ambiguity in its cultural policy which aims the strengthening of the State.

National Unity is the solid ground and the safe-conduct: harmoniously blends social classes, ideological tendencies, antagonistic achievements, contradictory heroes. A posteriori, redeems and reconciles, […] National Unity is essential for progress. the exaltation of syncretism as a guarantee of political, cultural and social balance. Separated, we are propitious victims of the enemy (imperialism, oligarchy, subversion, right-wing and left-wing). We are brought together by a sentiment of nationalism (irreplaceable virtues of our problems, own profiles, sustenance in the roots), hero cult (culture and history as the anthology of exceptional works and personalities, the past as a catalog or a proud enumeration from pre-Hispanic ruins to Juárez, from muralism to José Gorostiza). (Monsiváis, 2002; 961).

Monsiváis pointed out it was the radio, with La Hora Nacional, and film productions which were an important part of the dissemination of the nationalist rhetoric in order to build the coveted national unity.

However, the turn in politics was more evident in education, some authors point out that the change of direction of the narrative of socialist radicalism led to a nebulous policy of national unity which put nationalist interests of the State before any other. Conciliation of social classes was taken to the classrooms as a way to eliminate the social and community commitment of teachers. From then on, the approval of political activism or any other collectivist affiliation would be deemed suspicious.

The change of direction of the education policy, according to Meneses (1998), was carried out by two Ministers of Education, Octavio Véjar Vázquez and Jaime Torres Bodet. Véjar Vázquez was in charge of the constitutional reform to eliminate socialist education and “remove” radicals of the SEP involved in clearly anti-communist actions. That is how many professors were dismissed. Nevertheless, Véjar Vázquez was unable to deal with the teachers’ conflicts since he did not have their support, and he could not adequately mediate the issue of teachers’ unity which was his purpose given the great division and discontent among teachers’ groups.

Due to the lack of proposals for the long-awaited unity, the president Manuel Ávila Camacho turned to one of the leading figures of the Vasconcelismo, Jaime Torres Bodet, who later became Minister of Education (1943-1946).

Meneses maintains that the decision of President Ávila Camacho helped him make changes in the second part of his presidency, since Véjar Vázquez had already managed to establish some polemic changes such as the elimination of coeducation in elementary schools and Normal Schools as it was considered dangerous. He also promoted teachers’ training for middle school; and the issuance of the Public Education Act of 1942 which eliminated the postulates of socialist education. Regarding rural education, he abolished Peasants Rural Schools by eliminating and separating agricultural education in order to set up Practical Schools of Agriculture separately. He also implemented a new curriculum for urban and rural elementary education throughout the country, which was used for almost two decades.

The President intervened directly in the resolution and conciliation of different groups of Teachers’ Unions. Considering the turns of educational policies, it can be said that teachers felt the need for greater security and protection from their groups.

The corporate policy of the State and the control of Teachers’ organizations

In the context of the threats and effects of World War II, where national security was the priority, the Mexican State succeeded in building great authority to impose control over the workers’ organizations such as teachers; and at the same time to guarantee the alliance with the business sector. Union leaders were easy to manage by the government’s interests. 3

This power structure of the Mexican State, connected to the Party of Mexican Revolution (PMR), and later to the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), would determine the political dynamics through much of the 20th century with effects up to the present.

In the case of federal teachers, this meant the control of working conditions based on agreements between the Ministry of Education (SEP) and a single Union for the education workers.

Precarious employment in education was evident given the number of strikes for non-payment and constant dismissals. Teachers were made redundant due to their lack of qualifications. Base on the new Law of Ranking Promotion for Teachers driven by Narciso Bassols in 1933, they were required to hold an elementary education diploma to have access to a rural teacher position. Law wages, the lack of homogeneity in the study programs, attacks from the press, Synarchists, and parents’ associations constituted a tense and adverse work environment for teachers.

Teachers’ groups were incorporated into different workers’ unions such as the Union of Education workers of the Mexican Republic (STERM), the National Autonomous Union of Education Workers (SNATE), the Revolutionary Front of Mexican Teachers (FRMMM), among others.

In 1941, Minister Véjar Vázquez called teachers’ organizations to form a single Union and to accept a new statute and legal framework. According to Ornelas (1995), the discourse of the school of love and moralization of teachers implied dismissals, punishment for expressing ideas, and expulsion of communists. In general, he tried to impose his policy on teachers in authoritarian ways.

Although teachers joined a single Union in 1943, the truth is they agreed to request the resignation of the Minister Véjar Vázquez, which President Ávila Camacho had to accept.

The policy of national unity in education was determined by the new Minister of Education Jaime Torres Bodet, throughout the period of Ávila Camacho and other administrations.4 When Torres Bodet took up office in December 1943, he defined himself as a technical professional rather than a politician. He did not mention the school of love nor did he speak of socialist education but defined the national school based on the slogan of President Ávila Camacho: as democratic, Mexican and profoundly social. Having worked with Vasconcelos as head of the Library Department, gave him great credibility as an experienced educational reformer. He was also a recognized diplomat and intellectual, rather than an ambitious politician.

Torres Bodet was given extensive budget support, which allowed him to achieve significant increase in teachers’ salaries. According to the press, between 1940 and 1946 increases exceeding 80% were authorized. Thus in 1946:

Preschool teachers, who earned $142 a month, received 315.70 in 1946; elementary

teachers in Mexico City, whose salary was $176 monthly, received $375.57; middle school teachers with $250, received $425; and special education teachers, who earned $200, received $510.80. (La Nación, 20th December 1947).

Given the salary improvement, especially aimed at qualified and urban teachers, training and further education were also encouraged. The demand for training increased considerably, as there were a large number of teachers who were left out of the benefits due to their poor academic preparation.

The Federal Teacher Training Institute:

Torres Bodet, founded the Federal Teacher Training Institute in 1945, aim at offering courses in 6 years through correspondence education. 134 specialists were in charge of planning, they prepared lesson plans, and designed teaching materials for: mathematics, history, civics, geography, language and literature. Up to 163 172 lessons and exams were sent to teachers across the country delivered by mail, free of charge. In addition, there were face-to-face- courses in the so-called Centros Orales. Courses were intensive and they were taught in strategic places during school holidays.

Torres Bodet pointed out that there were about 17000 teachers who were not qualified.

In 1945, when the Federal Teacher Training Institute started, around 4500 teachers began to study to obtain the teaching degree they longed for.

In addition, study plans of the Normal Schools were reviewed as it was believed the teachers’ training was important for the consolidation of a modern educational system.

Professionalization of teachers was a great challenge, just in the Ávila Camacho administration there were 3 948 new teachers hired by the federation, most of them were women, especially preschool educators. The creativity for the pedagogical training of empirical teachers was highly valued and also imitated in other Latin American countries.

The feminization process of the teaching profession

In the last two decades, studies on the processes of feminization have pointed out the quantitative impact of the presence of women, as the teaching profession of elementary and preschool education had been gradually feminized since the end of the 19th century and throughout the 20th century, introducing a global phenomenon and distinctive of the construction of modern educational systems. This, for the Mexican case, required debates and meetings based on specific historical research work (López, 2003; Galván y López, 2008).

This confirms that the emphasis on the phenomenon of feminization of the teaching profession in Mexico occurred mainly in urban education, but we had many questions about the impact and dynamics of this process in rural and indigenous areas.

The methodological-theoretical challenge of the studies on feminization lies in the need to approach the historical configurations of the conditions of women. It is not only about building data of their presence from available documents, but also about analyzing the current representation in feminine matters and women’s work, which includes the analysis of normative systems that apply gender relations in society in both, formal and hidden terms, and the influence of symbols and ideologies in specific historical periods, in order to understand the agency of women in their individual lives, their identity construction processes, and their demands (Scott, 1993).

This is a titanic task, and yet the historiography is diverse and provides elements to understand these historical configurations of gender in socio-professional groups. It is necessary to dialogue with many local histories, biographies of female teachers and the imagination of education and gender studies researchers.

Having said that, it is important to place the analytical pieces for the understanding of the feminization process of the teaching profession during the period of national unity:

There was a State discourse in favor of incorporating women into the construction of a modern educational system and mass literacy. It is true that at the beginning, -the legacy of the 20th century prevailed- and only single female teachers could be part of the system, married female teacher were excluded from the system. This approach was modified by the beginning of the 20th century so it could be aligned with the pro-natalist demographic policies promoting the image of a modern teacher-mother, which was hegemonic throughout the twentieth century.

The professionalization of the teaching profession, carried out by the State since the 1940’s, tend to eliminate gender-biased pedagogical narratives in order to favor neutral teaching techniques. This was supported by a series of racial eugenic discourses about children, indigenous people and women’s body.

Feminization occurs with asymmetries that reveal the childcare tasks are considered exclusive of women in the educational system. This happened in the preschool education system, as an expansive phenomenon during the period of national unit. It also happened in the first years of elementary education but not in middle school, despite its growth. Thus, the hard and patriarchal nucleus of feminization of the modern Mexican teaching profession was bult.

The greatest precariousness and risks of the feminization process are observed among federal rural female teachers. Particularly the ones who were sent to Cristero Rebellion regions as peace-makers, without guaranties, without health insurance and with the lowest salaries in the entire system. These female teachers were founders of schools in a country that had 75% of its population in rural areas.

The Mexican catholic church was not in favor of modernization of women or coeducation in schools. During the first three decades of the 20th century, they showed resistance and totally disapproved of the State policies, they even encourage armed actions against the Sate. However, from the period of national unity, and the policy of conciliation, the church supported the educational policy and its private educational system resumed. They also assumed, in their own way, their participation in the national unity project, joined the civic activities and accepted a nationalist discourse.

The suffrage movement of feminists in Europe and The United States was supported in Mexico and Latin America in the 1930’s. This showed the new potential of female teachers in their organizing and claiming role, while generating gender and class awareness, with an impact on their own lives, on their Unions and on their demands for the improvement of their working conditions. The suffrage demands advanced more slowly, they would only see results in the decade of the 50s. During the Cardenismo and Avilacamachismo, feminist movements were repressed by the State corporatism (Tuñón, 1992).

In México, since the period of Vasconcelos and his literacy crusades, the rural education project was favored as never before; the participation of women in teaching was considered an unprecedented action. Later, we found a great number of female empirical teachers who applied for positions to formally join the educational system in towns and cities, even during the years or religious conflict and polarizations due to the socialist education, women did not abandon the teaching profession completely. They opted for mobility or for taking career breaks, but in general, they continued founding schools, teaching literacy in their communities, or training to obtain their teaching degrees.

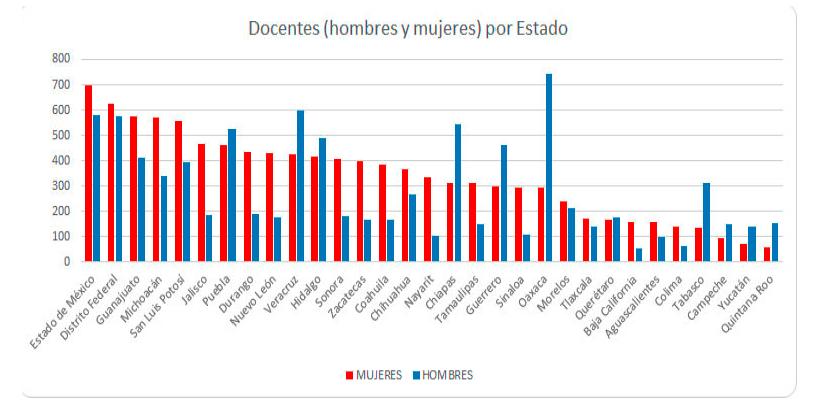

We have been able to identify that the feminization process of the federal teaching profession did not advance equally in rural areas, which might have been due to the unequal presence of the federation in the States (See graph 1 Table 1).

The presence of women in education was an issue that the State had to address, so they reviewed their demands and made adjustments to regulations and daily practices.

From 1933, Narciso Bassols had issued a Law of Rank Promotion that modified the old gender hierarchies which approved positions and salaries of assistants for female teachers, whereas positions of principals were for male professors. The new law established that opportunities for promotions and salaries would be based on merit, academic preparation, quality of service and seniority. It also established that pregnant teachers, regardless their marital status, should be entitled to have a fully paid 90-day maternity leave to devote themselves to their pregnancy, labor and puerperium period. This benefit for teachers, achieved in the context of maternalistic feminist struggles of that time, had as an argument in the regulation: To guarantee the life of the newborn, since there was a low birth rate and high infant mortality rate. In this context of demographic policy of the State, nursing mothers were also permitted to take three 30-minute breaks per day so that they could breastfeed their babies.

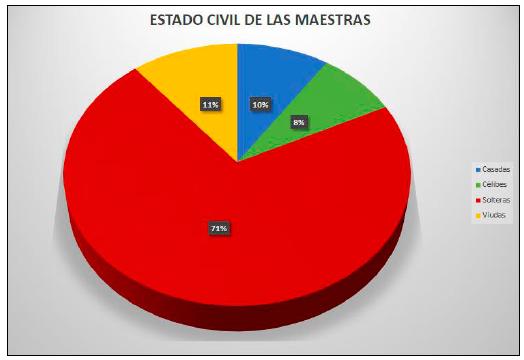

May 10th was established as Mother’s Day celebration by Vasconcelos through the pronatalist policy in 1922. In addition, the Ministry of Education (SEP) rewarded mothers who gave birth and raised many children. However, most female teachers were young, single women, some widows, and very few were married due to the refusal of inspectors and communities to accept pregnant teachers or single mothers. The double role of workers and mothers was considered immoral, especially in rural areas (See graphs 2 and 3).

Feminization process of rural teaching.

The specific condition of female teachers is not mentioned in the official histories of education in México, which has overshadowed their situation as a group. Although the feminization of the Mexican teaching profession has been discussed, there is absence of accurate data, as well as explanations of its heterogeneity. Even the SEP stopped generating data for some time, which resulted in a statistical phenomenon that complicated a detailed historical analysis of this process.

We have been able to find data focused on the Fund of Rural Female Teachers of the Historical Archive of the SEP which provided us with a vast amount of information on the working conditions and individual situation of female teachers. This document collection was constituted of the personal files of female teachers from the moment they were hired, which allows us to identify standardized data for quantification, as we recovered mandatory forms that were filled out by teachers when they first started working, as well as ideology declarations, evaluations, educational level, information on salaries among others. This collection also includes personal letters written by teachers and other members of the communities where they worked, which provide detailed information on some conflicts, sick leaves, complaints and other petitions addressed to the SEP authorities.

These documents are found in the General Archive of the Nation (AGN). Fund of Rural Female Teachers, Historical Archive of the Ministry of Education, General Direction of Elementary Education in States and Territories (AHSEP/DGEPET). Fund start period: 1924. 150 boxes with 10,466 files organized in alphabetical order. The regions with most files are the ones in the West and Central México as shown in the table below:

Table 1 Number of files revised on this research.

| REGIONS | NUMER OF FILES |

|---|---|

| WEST | 2 808 |

| NORTHWEST | 1 226 |

| NORTHEAST | 2 120 |

| SOUTHEAST | 1 693 |

| CENTER | 2 619 |

Source: Elaborated by LIGIDH-COLSAN, data from the General Archive of the Nation (AGN). Historical Archive of the Ministry of Education, General Direction of Elementary Education in States and Territories (AHSEP/DGEPET). Fund of Female Rural Teachers, start period, 1924.

We will show information related to the hiring process of female teachers, and it will be compared with the catalog of rural teachers. The exploration and in-depth study on the data related to men is in process since January 2022. pending.

Since the Vasconcelos administration, federalization was the modernizing expression of education, clearly as a State policy it favored the recruitment of women, first as literacy tutors and later they were offered a position as rural female teachers.

Keeping the teacher positions was not easy, due to the violent contexts prevailing in some regions, especially in the areas with the presence of Cristero rebels. Female teachers were also victims of sexist violence from inspectors and the communities.

Female teachers put into practice some strategies not only to maintain their jobs but also to keep themselves alive, demonstrating greater agency than in previous periods. They addressed their complaints to SEP authorities, joined Unions, and they also took part in feminist and political groups. They wanted to be heard. When they were not well-received in a community, they had to look for another one. Rotation between schools from the same region was highly favored as well as taking career breaks. All this led to great challenges, especially the lack of professionalization as most of them did not hold a teaching degree from a Normal School. It was a feminized teaching profession with many actions of bravery but poorly paid and vulnerable due to the lack of benefits and unsafe working conditions in rural contexts. Unions were starting to organize and the medical service was practically inaccessible to female rural teachers.

Even titles were not homogenized and they were extremely diverse, salaries were unequal, the highest for the SEP offices and the lowest for female teachers of rural and indigenous towns. They complained that an office boy from the SEP earned more than a rural female teacher.

The following graphs show data of the feminization process of the teaching profession by States. Information was taken from the personal files of female teachers.

Source: Elaborated by LIGIDH-COLSAN, data from the General Archive of the Nation (AGN). Historical Archive of the Ministry of Education, General Direction of Elementary Education in States and Territories (AHSEP/DGEPET).

Fund of Female Rural Teachers, 1924-1942.

Graph 1 Presence of rural teachers in México according to the personal files from 1924-1942.

The prevalence of young rural female teachers, manly in their twenties and single, has to do with the validity of the old model young female single teacher (señorita-profesora). (See graph 3). That is to say, teachers did not have the right to maternity or the possibility of alternating professional and family life.

It was not until the 1960s that female rural teachers were granted with such rights. By that time, urban teachers had already managed to consolidate the model mother-teacher and had access to professional medical service in the cities.

Source: Elaborated by LIGIDH-COLSAN, data from the General Archive of the Nation (AGN). Historical Archive of the Ministry of Education, General Direction of Elementary Education in States and Territories (AHSEP/DGEPET).

Fund of Female Rural Teachers, 1924-1942.

Graph 2 Ages of female rural teachers in México, according to the data from their personal files, 1924-1942.

In the period of national unit, rural teachers were benefited by new social institutions as part of a national union. The Mexican Institute of Social Security was opened in 1943, this institution would provide service to workers from all over the country. Years later, in 1960, the ISSSTE was created in order to provide social security to State workers.

Source: Elaborated by LIGIDH-COLSAN, data from the General Archive of the Nation (AGN). Historical Archive of the Ministry of Education, General Direction of Elementary Education in States and Territories (AHSEP/DGEPET). Fund of Female Rural Teachers, 1924-1942.

Graph 3 Marital status of female rural teachers in México, based on their personal files, 1924-1942.

Precariousness and resistance of female rural teachers

The teachers’ salaries ranged from one to three Mexican pesos per day; or 20 to 60 pesos a month. Despite being salaries from the federation, when they reached the State finances, they depended on a series of mediations and processes such as the payers, who sometimes withheld the payments, or transferred them through inspectors or other civil servants. Female teachers also calculated food and transportation costs to settle in towns, and they often reached the conclusion that they could not afford to live there on that salary. So, they quit their jobs and continue looking for vacancies in other municipalities until they were able to find something to meet their needs.

The personal files below provide information on female teachers’ salaries, their knowledge and their resistance strategies to keep their jobs. These files also allow us to understand the context of violence in rural areas in Jalisco, which were controlled by the Cristero rebels who attacked schools and threatened teachers:

Leave requests:

Refugio de la Mora received her appointment as a rural teacher on January 1st, 1925, for Buenavista School, located in the municipality of Ixtlahuacán del Río. He earned 2 pesos per day. In a letter, the residents of Buenavista said the teacher was suitable for the job and that her behavior was impeccable. Miss Mora requested a leave of absence as the school had been invaded by “fanatical troops”. She did not return to work so she was dismissed on February 21st, 1928 “for not showing up to resume her job” (AGN/AHSEP/DGEPET/ Box M9/77).

Rotation of underage female teachers in different schools

Teacher Magdalena Medina, 16 years old, single. She completed her primary education, and she received some training in Ahualulco. She was appointed school principal in El Chante, Autlán de Navarro, Jalisco, on October 21st, 1927. Since that region was occupied by the Cristero rebels, she was relocated to the Mezquitán school in Guadalajara, and later to the school in El Fresno, Atotonilco el Alto. She earned 2 pesos per day and she had to teach 3 groups of students, one in the morning and two in the afternoon. According to information in her personal file, she was sick, although the condition is not specified. On November 15th, 1933 she submitted her resignation for “suiting her interests”. (AGN/AHSEP/ DGEPET/ Box M7/93).

Teacher Esther Hernández, seventeen years old, single. She was appointed female rural teacher on February 1st. 1926. She carried out her teaching work in San Jacinto, in the municipality of Poncitlán. She earned 2 pesos per day. Later, she was relocated to Mezquitán in Autlán de Navarro, since the previous community was threatened by a group of rebels. (AGN/AHSEP/DGEPET/ Box H4/64)

Rotation and migration to the United States:

Teacher Engracia Estrada, completed her primary education, she became a rural teacher since May 21st, 1927. She was in charge of the school of Santiago Soyatán, in the municipality of San Sebastián, and then she was relocated to Las Canoas, in Techaluta. She earned 2 pesos per day. She submitted her resignation on October 21st., 1927 to emigrate to the United States. (AGN/AHSEP/DGEPET, Box E3/45)

Engaged at work:

Teacher María Mejía, widowed, and provider of 4 dependents, she was 34 years old. She studied for 2 years at the Normal School, she was appointed female rural teacher on Janury 1st, 1925. She earned 2 pesos per day. She started working at the school of Miradillas, in San Miguel el Alto, Jalisco. She was from the area, as she lived in Ocotlán. She promoted activities such as soap making, tanning, apiculture, clothing design and kitchen chores. She earned 3 pesos per day due to her good performance at work. The school inspector, Esteban Dueñas, pointed out that Miss Mejía was “one of the most serious and hard-working teachers in the area… her work has been acceptable despite the fanatism in the region”.

Regardless of her good performance and her need for work the teacher submitted her resignation on August 6th ,1933, for “suiting her interests” [...] (AGN/AHSEP/DGEPET, Box M7/47)

During the national unity period, female teachers were able to settle in their schools as their salaries improved a bit. In addition, violence decreased and the Cristero Rebellion came to an end. However, higher academic qualifications for teachers were established.

Population had grown, therefore the educational demands also increased, particularly in urban preschool education, which was a sector completely feminized, and the one with most female teacher positions available.5

Minister of Education Torres Bodet, knew it was necessary to consider long-term policies and planning, so he founded the Federal Teachers Training Institute. He was clear about the intellectual and material weaknesses of rural teaching.

But how can we demand thorough performance without providing them -at least- free, fast and uniform teaching training? Rural teachers were able to demonstrate their great human capacity but most of them lacked pedagogical skills. Only 9000 out of 18 000 had elementary studies. 3000 had graduated from Rural Normal Schools, and only 2 had studied the full plan of Normal Schools. (Torres Bodet, 1981; 332)

At the end of his administration there were about 25 543 teachers in the States and territories educating 1 514 448 girls and boys. There were 11 813 rural schools in total in 1946, but in rural areas there were also a total of 1636 federal State schools and 493 of Article 123, as well as boarding schools for elementary education and rural Normal Schools.

The increase in the number of elementary schools was evident. By 1946 they were 21 780. Nonetheless, only 60% of schools had a suitable building and only 25% had a house for the teacher. (Meneses, 2000; 276).

Torres Bodet followed Vasconcelos’ example, and called some intellectuals to collaborate in the revision of the school curriculum and textbooks, promoted the Institute of Pedagogy, expanded the libraries, and supported the improvement of industrial technical schools. He was a Minister who insisted on promoting culture and national unity in education in the long run.

He promoted the UNESCO agreements on peace, democracy and justice in order to update the educational contents.

National literacy campaign

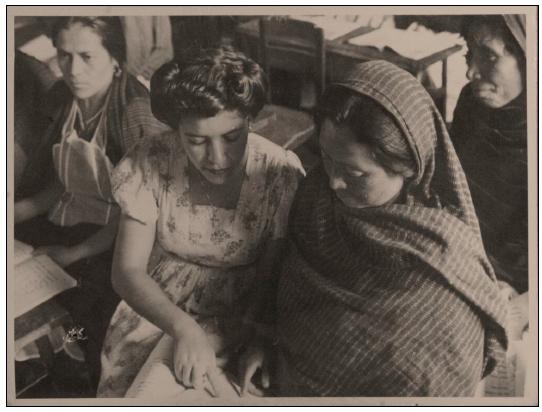

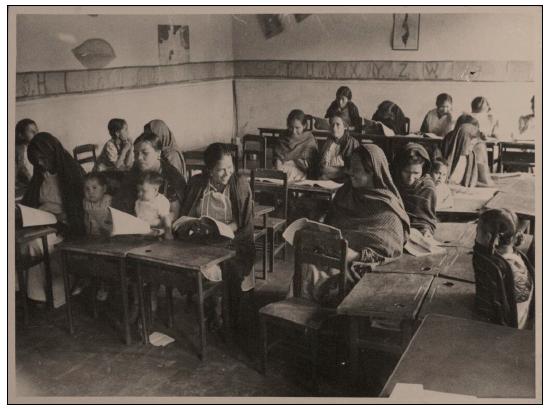

According to UNESCO, literacy was the best form of resistance in the context of war, as it favored moral and intellectual preparation based on education, not on militarization. Literacy campaigns were better planned, they resumed in 1945 and concluded in 1946 with satisfactory results. For this purpose, the Ministry of Education (SEP) published ten million literacy primers and later, in order to encourage reading, the Popular Encyclopedic Library was promoted through popular brochures.

Source: Photographic Library of the General Archive of the Nation. México.

Literacy Campaign.1945. Presidents Fund. General. Manuel Ávila Camacho.

Source: Photographic Library of the General Archive of the Nation. México.

Literacy Campaign.1945. Presidents Fund. General. Manuel Ávila Camacho.

Source: Photographic Library of the General Archive of the Nation. México.

Literacy Campaign.1945. Presidents Fund. General. Manuel Ávila Camacho.

Additionally, Torres Bodet undertook the improvement of school buildings by creating the Administrative Committee of the Federal Program for the Construction of Schools (CAPFCE) with additional funds derived from Petróleos Mexicanos. Construction of schools and expansion of literacy activities continued the following decades.

In 1944, México took into account the UNESCO proposals such as education for peace, democracy and justice. Especially in 1945, when México had an outstanding participation in the London Assembly where important resolutions were adopted and the idea education as the best strategy for war prevention was strengthened.

Final considerations

In the post-revolutionary period and the so-called national unity, great precariousness has been identified in rural teachers’ lives as well as in terms of their professional training.

In the context of the threat of war, some changes were imposed in the educational policy, which resulted in a new configuration where the State promoted a national corporatism faced with the possibility of confronting fascism.

During this period, a nationalist narrative of unity was strengthened, which covered up the repression of the State against socialist and reformist teachers throughout the national territory. The militarization of schools facilitated the attack on coeducation and in consequence segregated education in Normal Schools was resumed. In addition, in the context of the processes of feminization and professionalization of the Mexican teaching profession, rural and indigenous teachers continued to be the reference of precariousness in terms of salaries and professional training. Although violence against female teachers had decreased -because there was progress in the pacification and conclusion of the Cristero Rebellion in various regions in México- they were the most vulnerable group of the entire educational structure as they did not have access to further education therefore to fair salaries and benefits.

We can also see that UNESCO supported in the construction of national unity narratives, which provided the foundations of the Mexican educational system of the second half of the 20th century.

REFERENCES

Archivo General de la Nación. Fondo de maestras rurales del Archivo Histórico de la Secretaría de Educación Pública, Dirección General de Educación Primaria en Estados y Territorios (AGN/AHSEP/DGEPET). [ Links ]

FOTOTECA AGN, Fondo Presidentes. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

ACKER, Sandra. 2000 Género y educación, reflexiones sociológicas sobre mujeres, enseñanza y feminismo, Madrid, Narcea Ediciones. [ Links ]

ANA LAU-CARMEN RAMOS, 1993 Mujeres y Revolución 1900-1917, México, INEHRM, INAH, Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. [ Links ]

CANO, Gabriela, Mary Kay Vaughan y Jocelyn Olcott (compiladoras) 2009 Género, poder y política en el México posrevolucionario, Fondo de cultura Económica, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, México. [ Links ]

G. Joseph y Daniel Nugent (eds.) 1994 Everyday forms of state formation. Revolution and the negotiation of rule in modern Mexico. Durham, Duke, University Press. [ Links ]

GALVÁN, Luz Elena, Oresta López y Sonsoles San Román, (Coords.) 2001 Primer Congreso Internacional sobre los procesos de Feminización del Magisterio, 21-23 de febrero, San Luis Potosí, México. El Colegio de San Luis, CIESAS y Univ. Aut. De Madrid. CD. [ Links ]

GALVAN, Luz Elena y Oresta López, 2008 Entre imaginarios y utopías: Historias de maestras, CIESAS, México, COLSAN, PUEG-UNAM. [ Links ]

LOPEZ Pérez, Oresta 2001 Alfabeto y enseñanzas domésticas, el arte de ser maestra rural en el Valle del Mezquital. México, Colec. Antropologías CIESAS-CECAH. [ Links ]

LÓPEZ Pérez, Oresta, 2006 “Las maestras en la historia de la educación en México: contribuciones para hacerlas visibles”, en Sinectica, No. 28, Febrero-julio, pp. 4-16. [ Links ]

LÓPEZ Pérez, Oresta, 2010 Que nuestras vidas hablen. Historias de vida de maestras y maestros indígenas tének y nahuas de San Luis Potosí, El Colegio de San Luis. [ Links ]

MEYER, Lorenzo, 2002, “De la estabilidad al cambio” en Historia General de México. México, El Colegio de México. Pp. 883-956. [ Links ]

MONSIVÁIS, Carlos, 2002, “Notas sobre la cultura mexicana en el siglo XX” en Historia General de México. México, El Colegio de México. Pp. 959-1076. [ Links ]

NAMO de Mello, Guiomar 1985 “Mujer y profesionista” en Ser maestro: Estudios sobre el trabajo docente en Elsie Rockwell (comp.), México, SEP-El Caballito. [ Links ]

RAMOS Escandón, Carmen (comp.) 1992 Género e Historia, México, Antologías Universitarias. Instituto Mora, UAM. [ Links ]

ROCKWELL, Elsie, 2007 Hacer Escuela, hacer estado. La educación posrevolucionaria vista desde Tlaxcala, COLMICH, CIESAS, CINVESTAV, 2007. [ Links ]

SCOTT, Joan 1993 “Historia de las mujeres”, en Burke, Peter, et. al. Formas de hacer Historia, Madrid, España, Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

TORRES BODET, Jaime, Menorias, Mexico, Porrúa, 1981, 2ª. Ed. [ Links ]

TUÑON PABLOS, Esperanza 1992 Mujeres que se organizan. El Frente Unico Pro-derechos de la mujer 1935-1938, México, Coordinación de Humanidades UNAM- Grupo Ed. Miguel Angel Porrua. [ Links ]

VAUGHAN, Mary Kay, 2000 La política cultural en la revolución, maestros, campesinos y escuelas en México 1930-1940, Biblioteca para la actualización del maestro, SEP. [ Links ]

2There were three organizations of teachers, the one led by David Vilchis (CTM), those who followed Lombardo Toledano and the one led by the communist Hernán Laborde.

3In this period the name of “charros” Unions was coined to the groups controlled by their bosses with the support of governments.

4Jaime Torres Bodet (1902-1974) was the private secretary of Vasconcelos when he was in charge of the National University. Later, in 1922, Torres Bodet became the Head of the Library Department. He was also Subsecretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Minister of Education from 1943 to 1946 and from 1958 to 1964. From a very young age he was the author of poetic and biographical works. He was Secretary of UNESCO.

5During the administration of President Cárdenas, preschool education was in the Ministry of Health. Later, it was relocated to the SEP by Avila Camacho who created the preschool education department. Torres Bodet, focused on pedagogical attention to schools, he duplicated the number of schools and improved the buildings. There were 46 783 girls and boys enrolled who were served by 1492 women from various professions. (La Obra Educativa 1946, 63-72).

Received: July 11, 2022; Accepted: September 26, 2022

texto en

texto en