Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.22 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 07-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v22-2023-150

Dossiê 1 - História da formação e do trabalho de professoras e professores de escolas rurais (1940-1970)

Crossed memories: reconstructing the history of training and work of teachers in rural elementary schools in São Paulo (1940-1970)1

1Universidade Estadual Paulista (Brasil). noelycdgarcia@terra.com.br

2Universidade Estadual Paulista (Brasil). rosa.souza@unesp.br

This paper presents partial results of a research on the history of training and work of teachers from rural elementary schools belonging to the Board of Education of the municipality of São José do Rio Preto/SP between 1940 and 1970. The fundamental corpus of the study consisted of interviews with ten teachers (nine female teachers and one male teacher) who taught in rural schools during the period delimited for the study. Besides these oral sources, educational policies are analyzed in relation to the expansion of rural elementary education, as well as the changes in the Normal School, especially with the Reform of Primary and Secondary Education, by means of Law nº 5.692/71. TThe results obtained indicated that the teachers had difficulties with the multigrade classes and the location of the rural schools, generally difficult to access, however, many challenges were solved with the production of teaching materials, the production of meals and the purchase of primers for the children, but they were individualized solutions, since the rural schools in São Paulo never received systemic planning.

Keywords: History of the teaching profession; Training and work of rural teachers; Rural elementary school

Este texto apresenta resultados parciais de pesquisa sobre a história da formação e trabalho de professores de escolas primárias rurais pertencentes à Diretoria de Ensino do município de São José do Rio Preto/SP entre 1940 e 1970. O corpus fundamental do estudo foi constituído por entrevistas realizadas com dez professores (9 professoras e um professor) que exerceram a docência em escolas rurais no período delimitado para o estudo. Além das fontes orais, são analisadas as políticas educacionais com relação à expansão do ensino primário rural, bem como a as alterações do Curso Normal, em 1971. Os resultados obtidos indicaram que os docentes tiveram dificuldades com as classes multisseriadas e a localização das escolas rurais, geralmente de difícil acesso, contudo, muitos desafios foram dirimidos com a produção de materiais de ensino, produção da merenda e compra de cartilhas para as crianças, soluções individualizadas, já que a escola rural em São Paulo nunca recebeu um planejamento sistêmico.

Palavras-chave: História da profissão docente; Formação e trabalho de professores rurais; Escolas primárias rurais

Este texto presenta resultados parciales de la investigación sobre la historia de la formación y trabajo de los profesores de escuelas primarias rurales pertenecientes al Directorio de Enseñanza del municipio de São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo, Brasil, entre 1940 y 1970. El cuerpo fundamental de este estudio fue construido por entrevistas realizadas a diez profesores (nueve profesoras y un profesor) que ejercieron la docencia en escuelas rurales en el período delimitado para este trabajo. Además de las fuentes orales, son analizadas las políticas educativas relacionadas a la expansión de la enseñanza primaria rural, así como las alteraciones del Curso Normal, em 1971. Los resultados obtenidos indicaron que los docentes enfrentaron dificultades en relación a las clases con alumnos de diferentes niveles y la localización de las escuelas rurales, ya que generalmente eran de difícil acceso. Sin embargo, muchos desafíos fueron dirimidos con la producción de materiales educativos y de merienda, y compra de manuales para los niños. No obstante, estas soluciones fueron individuales, ya que la escuela rural en São Paulo nunca recibió un planeamiento sistémico.

Palabras clave: Historia de la profesión docente; Formación y trabajo de profesores rurales; Escuelas primarias rurales

As soon as she graduated from the normal school, she decided to transfer her eighteen years and her joy as a young girl to a neighborhood school. She went there somewhat out of a spirit of adventure, as if she were going to play being a teacher, and much out of necessity, hoping that with her salary she would have more abundance of clothes and fewer limitations on her desire to have fun. She was appointed. She took the train and traveled four hours. She got off at a lonely station, lost in the outback, where a sleepy trolley waited for her. She traveled another three hours, uphill, downhill, over dusty and rough roads. The trip never seemed to end, with the boredom of the monotonous turning of the wheels on the sand. [...] She arrived at the farm. The administrator's family lived in the old and gloomy house. That was where she was going to stay, in a room of empty tiles, without a window, next to the harness warehouse. [...] At night, she retired to her room, which smelled of grease; she locked herself in; lay down on her board bed on a noisy mattress made of corn straw, blew out the candle. And then, remembering the backlands she was in, the monotonous turning of the trolley up and down; thinking of the people she was going to live with, the way they spoke, the way they ate, her future students - the image of the capital, surrounded by the memory of her mother and sisters, came to her mind as something distant, far away, lost forever - and she began to cry slowly, like a child. (ALMEIDA JÚNIOR, 1951, p.130-131).

The description of Almeida Junior extracted from the book A escola pitoresca e outros estudos2 poetically portrays the ills of entering the teaching career of a teacher in a rural school revealing the conditions of life in the countryside. The contradiction addressed by the author puts in question the enthusiasm and expectations of the newly formed normalist in relation to the career in the magisterium and the deplorable reality faced by her in the first contact with the rural environment. The difficulty of getting to school, the situation of dependence on the farmer, the discomfort of rural life and the sadness felt by the teacher due to the confrontation of cultures are portrayed by the author to demonstrate situations experienced by normalists in the state of São Paulo when entering the teaching profession.

Although the situation described by the author refers to the context of the early 1930s, this reality was not very different in the following decades, which could be corroborated in the testimonies of the teachers interviewed for this research.

As the recent historiography on the subject has so well demonstrated, not only in the state of São Paulo, but in different regions of the country, the differentiation and inequalities between urban and rural schools have marked Brazilian education throughout the 20th century (LIMA and ASSIS, 2013; LIMA, 2018; SIQUEIRA, 2019). In 1940, 69% of the Brazilian population lived in rural areas and in 1960 this rate was still 55%. However, despite this concentration of population in the countryside, educational policies carried out by the governments of the states privileged urban areas. The expansion of rural primary schools intensified in the country between the 1940s and 1960s amid numerous problems such as the material precariousness of schools and the large number of lay teachers in various states. Nevertheless, the research has highlighted the relevant role played by rural primary schools in childhood schooling in Brazil (SOUZA and FARIA FILHO, 2006; AVILA, 2013; SOUZA; SILVA and SÁ, 2013).

Aiming to contribute to the studies on the history of rural education and the teaching profession, this text presents partial results of research on the conditions of entry and work in the rural primary magisterium in the region of São José do Rio Preto/SP, between 1940 and 1970. The initial time frame (1940) marks the period of Union initiatives in relation to the expansion of rural primary education through investments, in the construction of schools and training of rural teachers and the final period (1970) is justified by the extinction of the model of training and adoption of new models from the implementation of the Education Reform of 1st and 2nd Grades, by Law 5.692/71.

For this study were used oral narratives of nine female teachers and one male teacher who entered rural primary schools between 1940 and 1970, in the region of the Teaching Regional Office of São José do Rio Preto. Of the ten interviews, eight were conducted throughout 2019 and two at the beginning of 2020.All interviews were conducted in the city of São José do Rio Preto. The memory of teachers in this research was examined based on authors who have dedicated themselves to methodological analysis of memory such as the studies of Thompson (1998), Halbachs (2006), Le Goff (2003), Meihy (2000, 2013), among others. The oral sources were recorded in audio upon authorization of the teachers by signing the Informed Consent Form - TCLE. The teachers interviewed reported the experiences in the teaching based on a semi-structured questionnaire, leaving the narratives flowing, whose synthesis followed the necessary comparison with other sources and pertinent bibliography. In this sense, documentary sources such as legislation, reports of teaching delegates and school inspectors and statistical summaries were also used.

For the analysis of the sources we use the notion of representation of Roger Chartier (1991) and in the reflections of Certeau (2013). Thus, the systematic reports of the memories of teachers who began their respective careers in rural schools, in the region of São José do Rio Preto, is part of the analyses, whose aim is to understand the strategies and tactics used. The use of the concepts of "strategies" and "tactics" are anchored in the studies of Certeau (2012), in view of the current educational policies that established the criteria for entering the career of the magisterium.

In the first part of the text, the norms on entering the career of primary teachers in the state of São Paulo and the strategies employed by the public authorities to compel the recent graduates to teach in rural schools to ensure the provision of schools in the rural environment are analyzed. Next, the text highlights the memories of the female teachers interviewed on the conditions of rural primary schools and the itineraries traveled by them in the rural magisterium marked by ephemeral passage and intermittence.

The conditions for entering the teaching career in the primary magisterium of São Paulo

The issue of providing teachers to rural schools played an important role in the standardization devices for entering the primary school in the state of São Paulo. The criteria for entering the teaching profession in the 1930s, were established according to the prescriptions of Article 3 of Decree No. 804, of 16 January 1933, in which the teacher should enter the entry contest in the period from 1 to 15 of January, at the headquarters of each School Police Station (SÃO PAULO, 1933). Teachers should present the diploma of the Normal Course completed in state schools, or those equated, in addition to the mental health sheet and certificate for those who had time of service in the magisterium.

In fact, the entrance of the newly graduated in the first stage schools, known as isolated rural schools, had already been exercised in the state of São Paulo since the reform of 1904 (Law nº 930, of 13 August), which subjected the entrance of the teacher in isolated schools, conditioning removal only after 200 (two hundred) exercise days in rural schools.

Another device for the teacher entry contest in the state of São Paulo was the Education Code of 1933 (Decree nº 5,884, of April 21), instituted by Fernando de Azevedo. The first innovation of the Code was the minimum and maximum age of the candidate to enter the competition, which before was not mentioned in the decree and was now delimited in age groups between 18 and 45 years. In addition to this, it was authorized the promotion of the teacher to higher internship, however, the candidate can go from the 1st to the 3rd or from the 2nd to the 4th, provided that proved net time 800 (eight hundred) exercise days in the internship. The Code provided for preference in the removal of teachers who had more consecutive practice time in the same school.

The classification of isolated schools and school groups remained defined in stage levels for the effect of the first admission. The Code provided for the distribution of public primary schools in: isolated schools, school groups, night popular courses and experimental schools. Unlike the reforms undertaken in the 1920s, isolated schools were classified according to their location among urban or rural (SOUZA and ÁVILA, 2015). The purposes of primary education prescribed in the Education Code, "[...] reiterated the national character of teaching, the integration of the school with the environment and the needs to meet the interests and needs of children". (SOUZA, 2019, p. 26).

After eight months of institution of the Code of Education, was introducing changes in the career of the primary teaching, through the promulgation of Decree 6.197, of December 9, 1933 that changed the classification of primary schools of the state adopting 5 stages; criteria based on the location of schools (located in the capital or in the interior, whether in the rural or urban area).

Thus, in the consolidation of the norms of Decree nº 6,197, two contests were instituted that would take place after the end of the school year, the first of removal, in December, and the second, of entrance and reversion to the magisterium, in January. The vacancies would be filled until the next competition by the effective substitutes of the local school groups and, in the absence of these, by senior or lay interim teachers, who would be dismissed on November 30.

From this perspective, teacher Maria Alvarez Romano reported that she began teaching in rural areas in 1940. In this regard, she says:

Before I graduated, I started in the school that my father built. I stayed for about six months. I went to isolated schools, because at that time I needed points to join the magisterium. It was not a contest, it was points. I needed a few points to get in. So in that school that I taught, before I graduated, they counted points together with the other schools that I taught, being already graduated. I graduated in 1948, in São Paulo. In 1949, I came to José Bonifácio. Then I went to rural schools. (MARIA ALVAREZ ROMANO, 2019).

According to Maria Alvarez one of the reasons that led her to rural schools was because "at the time needed points to join the magisterium, it was not by contest, it was points." At this point in the narrative, the teacher was confused about the admission criteria of the state of São Paulo, since the execution was by contest. Acting in rural areas was a requirement of state legislation, and the score was essential for the teacher’s classification criterion. Thus, the 1935 legislation provided for "appointment of laywomen in the absence of graduating teachers". (SÃO PAULO, 1935, p. 6).

For the formation of the points of the candidate for the entry contest, the following elements would be evaluated: time of exercise in the teaching as a teacher, substitute, or acting graduate; the number of complete years from the date of graduation to the contest, being counted for each year ten points, up to a maximum of five years; duration of the course to the time it graduated, being awarded ten points for the Normal Course as for improvement; a general average of the diploma, calculating from 0 to 100, with approximations up to tenths. (SÃO PAULO, 1933c).

With regard to removals and promotions, these should happen in December so that in January of the following year the list of schools and class vacancies, remaining in each municipality of São Paulo for the contest and admission or reversion3 to teaching.

In 1935, through Decree nº 6.947, of February 6, new changes were introduced in the career of the primary magisterium classifying the schools in only three stages:

1)They are of first stage, except those of the municipality of Capital, schools and classes located in the rural area and headquarters of peace districts not served by railways; 2) They are of second stage, the schools and classes located in the headquarters of peace districts by railways and in the headquarters of municipalities, except those referred to in n. 3; 3) They are of third stage, the schools and classes of the municipality of Capital, headquarters of the municipalities of Santos, São Vicente, Campinas, Santo Amaro, São Bernardo and peace districts of São Caetano and Sto. André. (SÃO PAULO, 1935, p. 1)

With the new provision, the schools located in the rural area were classified as of 1st stage and 2° internship depending on whether they are serviced by railways indicating the relevance of the means of transport to the school organization and provision of teachers.

In 1941, Decree-Law 12,427 was approved, of December 23, by the federal intervener Fernando de Souza Costa, which embodied new provisions related to the career of the public magisterium of São Paulo. The entry and re-entry contest remained the same as it was already being held, that is, could only enroll graduates by the training courses of primary teachers of the normal state schools and teachers to these courses equated. Appointments would also be of an interim nature and the teachers would serve as interns. It is worth noting the need to complete the teacher training course, which was possible, given the large offer of public and private normal schools in the capital and in the state.

The calculation for the formation of the points of each candidate for the title of intern underwent changes involving the following elements: exercise time as a teacher or substitute of urban and district municipal school (nine points per month); as substitute teacher of second or third stage state school or class, as well as of primary school attached to normal free schools (nine points per month); as substitute teacher of school or state class of first stage and municipal rural (thirty points a month). (SÃO PAULO, 1941).

They were also evaluated in the composition of the points, the number of complete years of teaching exercise until the maximum of five years, date of completion of the normal competition (if graduated by Normal School would be equivalent to ten points and if graduated by the Institute of Education of the University of São Paulo, 15 points). Likewise, the general average of the notes of Psychology and Pedagogy was computed, multiplied by three (graduates by the normal school) or of History and Philosophy of Education and Educational Psychology, multiplied by four (graduated by the extinct Institute of Education of the University of São Paulo (SÃO PAULO, 1941).

This was the first time that the points appeared in a specific way for the substitute teacher of first stage school or rural state and municipal class. As can be observed, the highest score was for teachers who had taught in rural areas, a way to encourage and enhance teaching in the rural area.

Another change foreseen in the decree was the classification of the state’s primary schools in three stages. Thus, isolated schools and school groups were classified for statistical purposes in: [...] a) urban, district or rural, according to whether they worked in the city, district of peace or rural areas; b) as to the students' gender, in men, women or mixed; c) for the purpose of the primary teacher’s career, in 1st, 2nd and 3rd stages [...] (SÃO PAULO, 1941, p. 1)

The classification of internships followed the same prescription of the 1935 legislation. In 1942, the "prize chair" was instituted, as another form of entry into the magisterium of São Paulo. Through the enactment of Decree-Law 12.801, of 13 July, the benefit was granted to graduates of the Caetano de Campos Normal School, being established, that each year, as an award, the nomination, independent of competition, for the school or class of the municipality of the Capital, the student who graduates with the highest average, and may not be less than ninety. (SÃO PAULO, 1942)

The concession of this advantage was also extended to students of other State Official Normal Schools, however, the appointment would be for schools or state class, except those located in the Capital region. If there was equal average, the prize would be awarded to the older.

With the approval of Decree 15.993, of 29 of August, of 1946 the convocation of candidates to enter the magisterium with the right to "prize chair", It happened to be made by the Department of Education, five days after the removal contest. Applicants should present the diploma together with a certificate from the principal of the school in which they graduated, in which they confirmed that the applicant was in a position to acquire legal favor, with proof of the averages obtained during the course.

In 1949 a new law was passed regulating the form of entering the public magisterium. According to Law no 467, from 30 September 1949, it would be up to the Department of Education to publish annually a notice calling candidates in the month of January, so that registrations were made for ten consecutive days in any state Teaching Police. The schools and classes to fill were all of the 1st stage and remained vacant after the removal contest. Schools were offered to candidates in general call, respecting the classification in the decreasing order of the points obtained.

For the formation of points, substitutions and interim or occasional regencies made before the candidate's graduation were added to the counting of time of effective exercise. Teachers under 18 and over 45 years old were not allowed to join, as well as foreigners and those who were not even with the Military Service (SÃO PAULO, 1949, p. 5).

Teacher Nilce Apparecida Lodi Rizzini is an example of a candidate who joined the countryside by granting the right to the "prize chair". She reported that she enjoyed this prerogative to have completed the normal course at the State Institute that enabled her.

award of PRIZE to choose, a class in primary school together with the teachers enrolled in the removal contest. This award was created by state law and applied since the creation of the State Institute of Education Course from 1950 to 53. In my case this was the stimulus that awakened the desire to compete. Many dedicated themselves to passing with the best grades during the Course. I got the award in 1953 and it determined the direction of my teaching career. (NILCE APPARECIDA LODI RIZZINI, 2020)

Nilce Lodi enrolled in the primary teaching competition in 1954. Although she reported that the choice of awarded normalists was made before the teachers enrolled for the removal, the prescribed in the current legislation was that the registration would be after five days of the removal contest. However, she explained that at the São José do Rio Preto Teaching Regional Office there was no vacancy in any of the city’s School Groups, only a mixed rural school, located 7 km from São José do Rio Preto. In this way, she chose the Scaff Farm Mixed School, in São José do Rio Preto.

In fact, in the set of narratives analyzed, with the comparison of the laws examined, one of the strategies used by the state government to address the absence of teachers in schools located in rural areas was to institute educational legislation so that the first appointment of the teacher would be in the rural area.

In view of this, the teacher Aparecida Aude, whose beginning in the rural magisterium took place in 1961, explained: "So the reasons that led me to the rural environment was the opportunity of newly graduated. Opportunity to earn money. Opportunity to work. My goal was to teach". For the normalists, the criteria established for entering the teaching career intertwined the rural school and the need for work.

In 1961 also took place the entrance of the teacher Irce Elias Pires da Costa. She said that her early teaching in the countryside took place because it was necessary to add an adequate score to have lessons awarded and even outside São José do Rio Preto could not "catch anything", since there was no competition open at the time.

Points were how many days taught. To enter the teaching profession. At first it was only points, then... when I joined, 25% of the vacancies were based on tests and 75% on points, but I was based on tests. Then the following year it was 50% by test and 50% by points. Then the next year 75% of the vacancies were by exam and 25% by points. The next year it was 100% by exam. You did count the points for classification, but you had to take the exam. Then you had to take the contest. I entered in the first contest of titles and tests. The first contest that was open for testing, I took the contest and passed. Thank God. (IRCE ELIAS PIRES DA COSTA, 2019)

However, on December 24, 1962, Decree No 41,277 was approved, regulating Law No 7,378, which caused rectifications. In this way, the subjects of the entrance tests have been determined. For the proof of general culture, the knowledge in Portuguese and General Knowledge and those of specialized culture, Psychology and Methodology would be evaluated. If they had the proof of intelligence, vocation and personality or teaching ability, would aim to exclude candidates who presented serious contraindication for the exercise of the profession. In order for the applicant to be qualified, she should obtain a score of 50 or more in general culture, specialized culture and general average.

Another correction suffered in Law 7.378, were the evaluations of titles that began to be analyzed with more elements on the aspects of the teaching experience involving the time of acting in the magisterium and cultural formation and activities in the school environment: Regency of the Children’s College, help in the auxiliary activities of the school, classes given to groups of students of difficult learning, vacation and specialization courses, physical education classes.

Thus, between the years 1964 to 1966, the provisions of the classes and schools of primary education vacant in the state obeyed what provided for Article 6 of Law 7.378:

I - In 1963, 75% (seventy-five percent) of the existing vacancies, through a competition of titles, of 016, according to Law n. 467, of September 30, 1949, and respective regulations, and 25% (twenty-five percent), through competition of titles and tests, in accordance with this law.

II - In 1964, 50% (fifty per cent) of the existing vacancies, by means of competition of titles, according to Law n. 467, of September 30, 1949, and respective regulations, and 50% (fifty per cent), by competition of titles and tests, according to this law.

III - In 1965, 25% (twenty-five percent) of the existing vacancies, by means of competition of titles, according to Law n. 467, of September 30, 1949, and respective regulations, and 75% (seventy-five percent) by means of competition of titles and tests, according to this law.

IV - As of 1966, all vacancies exist, through competition of titles and tests, according to this law. (SÃO PAULO, 1962c, p. 2).

Anyway, the beginning of the teaching of primary teachers in São Paulo took place in isolated rural schools. This statement meets the narrative of teacher Maria Inês Magnani Salomão. After graduating, she reported that available class was only in the sertão, since in the cities there were few schools and were already occupied by effective teachers. With this, the only way was to "put your foot on the road and teach away". Thus, the reasons that led her to the rural magisterium was the need to get a room to work, besides adding points to compete next year a vacancy in the city schools, as can be verified in her narrative:

In the outback you took an easy class. Staying here in the city.... Rio Preto was a small town, it did not have much resources in terms of number of schools. But to take lessons here was also about who came before, because it was by points too. I had no point, I was newly graduated. There’s no point in competing with... if you taught here for a year, you’ve already earned ten points. So we went to the outback to score points, and then we came back. Then came the entry contest and if you had those points they were added to the contest score. But we had nothing, no point. So let’s go to the outback, let’s teach! (MARIA INÊS MAGNANI SOLOMON, 2019).

Teacher Palmira Miqueletti Marra reported that after graduating from normalist in 1968, she started the Faculty of Geography in Catanduva. At that time, she worked in the commerce in São José do Rio Preto:

I didn’t quit the job I was. I worked in commerce. I didn’t leave because my college was an autarchy4, right... and I had to pay a little and I thought like that. If I venture to pick up a class this year, maybe next year, I won’t be able to take an emergency teacher class. Sometimes If I didn’t get a class the next year and then it would make it difficult for me to finish my college. (PALMIRA MIQUELETTI MARRA, 2019)

Her narrative points out that the isolated schools were of the emergency type. Created in the 1950s, emergency schools were part of a deliberate policy of the São Paulo government to expand primary education in the state of São Paulo to serve students of 1° primary school year in a precarious and palliative nature in improvised classes and with teachers hired as surrogates (LEITE, 2018).

When the Public Notice5 of an entry contest for the magisterium was published, teacher Palmira was approved, but its effectiveness was not immediate. However, in 1972 the state government issued a decree giving priority of choice in emergency schools to those teachers approved in competition. Through this possibility, she was able to be hired as a substitute in a rural school. She thus reports the reason that brought her to rural school, whose salary was higher than what she earned working in commerce:

It was the salary at that time. I earned at the company I worked for, I don’t remember if it was $250.00 cruzeiros or cruzados and I went to teach earning $750.00. So that also helped a lot. And it was the opportunity that I was waiting for do what I always wanted to. Being a teacher! (PALMIRA MIQUELETTI MARRA, 2019)

Therefore, the analysis of the sources (documentary and oral) revealed that entering the rural magisterium in the state of São Paulo was not a choice of teachers, but the only option to begin their career. Only after the minimum time of 200 school days did they request removal to another establishment. In this sense, the normalists "paulistas had no way to escape the baptism of fire in the rural school". (ALCÂNTARA, 2012, p. 294).

Given the historical cutout analyzed here, it was noted that the teachers used the strategy of entering the magisterium in isolated rural schools to accumulate points and conquer successive transfers until reaching schools closer to urban centers, so they could start a teaching profession in the state of São Paulo.

The laws here were interpreted as strategies used by the governments of São Paulo to ensure education in isolated rural schools constituting these educational establishments as mandatory elements for the beginning of the career in primary education. In the set of the ten narratives analyzed, common points were identified for entering teaching in the rural environment, although there are particularities of each, the reports reveal this assertion, insofar as they evoke the form in which they began their career.

Teachers, in general, entered the profession in the rural area at different times. Nine of them had a specific training to work in teaching and only one teacher started her activities as a lay teacher having only the primary course.

Table 1: Entrance to the rural magisterium of São Paulo - 1940-1972

| Teacher | Start in the rural area | Type of admission |

|---|---|---|

| Maria Alvarez Romano | 1940 | Tender |

| Nilce Apparecida Lodi Rizzini | 1954 | Government Decree |

| Ivanilde Afonso Prudencio | 1959 | Tender |

| Irce Elias Pires da Costa | 1961 | Tender |

| Yara Aparecida Aude | 1961 | Tender |

| Maria Inês Magnani Salomão | 1966 | Tender |

| Maria Nirce Previdente Sanches | 1967 | Tender |

| Jorge Salomão | 1971 | Tender |

| Palmira Miqueletti Marra | 1972 | Tender |

| Sônia Aparecida Azem | 1972 | Tender |

Source: Elaborated by the authors

Throughout the above, teachers from the region of São José do Rio Preto entered the career through a competition, being appointed as substitute teachers. Starting a career as a substitute teacher in the rural environment was one of the appropriate tactics by teachers, in order to accumulate points and achieve in subsequent years better ranking for appointments and removals.

Itineraries covered in the rural magisterium

From 1920 the ruralist proposals began to circulate in the Brazilian educational field. However, in the state of São Paulo, only between the 1930s and 1960s, the policies of the state governments focused on rural primary education began to be debated between rural farmers and supporters6 of the common school. (SOUZA and ÁVILA, 2015)

From this stemmed, in the conception of Ávila (2013), the idea of an educational model aimed at rural life as opposed to a common school in the city, causing debates around the adoption of rural school models that should be spread in the country.

Among those who advocated a rural school model were the educators, supporters of the New School, who advocated a single, common school for all, regardless of where it was located. The ruralists, in turn, argued that the rural area should include a typical rural school, with an agricultural vocational training. (ORANI, 2017).

In the 1930s, among the various types of classification of existing primary schools: school groups, isolated schools, reunited schools, isolated urban schools and rural schools, The differentiation of the network of primary schools in the rural area began with the creation of school farms, rural school groups and typical rural schools. (SOUZA and ÁVILA, 2015). In this way, primary schools in rural areas began to coexist as

common primary schools, with the same program as isolated urban schools, and typical rural primary schools, that is, with objectives and programs for rural areas. In the Consolidation of Teaching Laws, the separation between primary education and rural education was established. The first designated teaching in urban and rural primary schools of common education. The second referred to the type of rural education, that is, that is taught in typical rural schools, in school groups, in agricultural courses in normal schools and in intensive courses for rural teachers. (SOUZA and ÁVILA, 2015, p. 235-236).

In the state of São Paulo, the typical rural education was taught in three types of primary schools: in the School Farms, in the Rural School Groups and in the so-called Typical Rural Schools. These schools provided specific education programs for the rural environment, in addition to requiring agricultural training or specialization from all the employees who worked there. However, rural type schools did not have a significant development, being restricted to a small number when compared to the significant number of isolated schools7 . (MORAES, 2014; SOUZA e MORAES, 2015).

In 1955, Decree 24,400 authorized the creation of " [...] up to one hundred (100) primary classes, for temporary operation, during the two-year period, in state-owned rooms and sheds or for this purpose provided by private entities or private individuals". (SÃO PAULO, 1955, p. 1). As previously mentioned, the installation of these classes was an action of the government to supply in character "emergency" the lack of places in the state’s public primary schools.

I worked in Floreal, in Nhandeara, in Nova Lusitânia, in the rural area... There I was forced to live, because I could not go back and forth. Here I was already married and lived in Nhandeara. I went to Nova Lusitania to score points for another year. I had to live there... on the farm. (MARIA NIRCE PREVIDENTE SANCHES, 2019)

She did not remember the name of the schools, but explained that the first rural school where she taught was on the farm of an owner named Orlando Manzato, in the city of Nhandeara, in 1967. To accumulate points, she was prompted to reside on the farm. In 1968, Maria Nirce worked on the farm of the Belini family, in Floreal, but this school did not need to reside in the locality, because there was a bus for daily commuting to the school. Even so, she said she had faced several problems, especially for the return home, since the bus had fixed hours to pass only at the outward time, however for the return home she stayed long waiting for the bus to pass or depended on some ride. In 1969, the interviewee taught at the Canjarana farm in Nova Lusitânia. On this farm she was forced to live there, because she could not go and return on the same day due to the distance. At that time her son had already been born and was two years old. As she had to live on the farm, she ended up taking her son with her. The owner was a widow who lived with her six children and arranged a room for her, where she could stay with her young son.

The difficulties of access and living in the countryside explain the intermittence in the exercise of the magisterium in these localities as it was possible to apprehend in the oral sources collected for this study.

Teacher Palmira Miqueletti said that the first rural school where she taught, in 1972, was at the Emergency School Fazenda Monte Belo8 in Nova Aliança/SP, a city that she considered "[...] prospers that after the attack extinguished the city, but there were some people there, right". The following year, she performed at the Fazenda Laranjal in Nova Aliança. Then, at Fazenda Santa Inês in Potirendaba and, finally, before taking a permanent position in the urban area, she took a school at Fazenda Fulgência, in Tanabi, 38 km after the municipality of Tanabi.

Maria Ines' reports corroborate with the other teachers. After completing the normal course in 1965, the only alternative to entering the career was, as she said, "put foot on the road and teach away", so she enrolled in the Teaching Regional Office of Jales/ SP, because there was vacancy in the district of São João de Iracema, a village near General Salgado 127 km from São José do Rio Preto, as described by her:

São João do Iracema was a small town... like this. It had the church... the square around the church, the blocks were inhabited... it had houses, I mean it had 2 or 3 houses each block, only...then it was a place. It was a place, it was a farm, that’s it... In that little town there was a church, there was a bar, there was a notary, and just... it was more rural than urban. The children who lived far away went on horseback, because right there in the centre had hardly any... there were no students, the students came from farms, farms, farms. (MARIA INÊS MAGNANI SALOMÃO, 2019).

Maria Inês taught in São João de Iracema between 1966 and 1967. In 1968, worked at the Zocal Farm, in the municipality of General Salgado, teaching at the First Mixed Rural School9 , having the obligation to reside in the place because of the distance traveled, because it was necessary to move by bus to Araçatuba and complete the walk for 4 km. A similar situation occurred when teaching classes in another farm even further away from General Salgado, whose itinerary was 20 km by bus and 4 km by horse. In 1970, she taught at the Rural School of José Bonifácio. In 1971, she took a leave from a pregnant teacher in the municipality of Potirendaba, where the rural school was accessible by buggy.

Another example is denoting the intermittence of teaching in rural São Paulo. According to the narrative of teacher Yara Aude, she worked

In Pirangi was in 1961, I do not remember if it was Mixed School of the Neighborhood Santa Luzia. In Cedral, 1963 at Escola Mista do Bairro da Abelha, it was four months. Still in Cedral I worked at Fazenda Bortoluzo as well. Then I went to José Bonifácio, at the Mixed School of the Neighborhood of Matão. Then I returned in 1971 to Cedral again, in the Mixed School of the Neighborhood of Açude, where I stayed 1971 to 1980. (YARA APARECIDA AUDE, 2019).

During this period, her work in rural areas was discontinuous, covering teachers' licenses: "three months here, four months there", but received very little. She had established on the state network in 1967. In addition to the rural schools mentioned, for a time, she worked in the following cities: Santa Albertina, Santa Fé do Sul and Santa Clara d'Oeste, all located in the urban perimeter. In 1971, she returned to Cedral to teach at the Mixed Rural School of the Açude neighborhood, remaining until 1980, but as it was effective in two contests it was necessary to make the choice between teacher P1 or teacher P3, Yara explains "I effected the contest in both, both P1 and P3. In 1980 I had to choose. Then I chose Rio Preto as P3, so I came here. I stayed with Mathematics and was in my city. She did not have that expense". She worked for 27 years, of which 10 years were dedicated to the rural environment.

Unlike the other teachers interviewed, the teacher Nilce Lodi, worked only in a rural school. Having entered the magisterium starting with the award of the "prize chair", in 1954, she was able to choose a school closer to São José do Rio Preto. She explained that she chose the Scaff Farm Mixed School, created in 1953. The school was located in the headquarters of an old coffee farm, very rich, with huge coffee plantations: "[...] the largest in the Municipality. The farmhouse was wonderful, with a walled garden. Its owner was assigned to the school, the old office next to the farmhouse. To the side, the yard and a series of the houses of workers and the corral". Added:

It was the only choice I could make inside Rio Preto. The only award for best student...the award gave me the right to a school within Rio Preto. In Rio Preto the only vacant school to be chosen was this or else I would choose Balsamo. This school was inside Rio Preto. It was 7km. It was a mixed first grade school. In the contest when I went to São Paulo to choose, the panel warned: you only have this school in Rio Preto, it is not in any School Group within the city, but it is of first degree. In Rio Preto there are people who wanted this school or else I could choose a School Group in some neighboring city. Between traveling to a neighboring city, I preferred there, because our family had a nearby place. So I found it much more interesting to choose this first grade. (NILCE APPARECIDA LODI RIZZINI, 2020)

In general, the reports showed the "passage" of teachers through various schools in the rural environment. It was mentioned as a passage because they remained for a short period in schools in the rural area, as we can see in Table 2.

Table 2: Region of operation

| Teacher | Region of operation | Number of Schools | Time of rural Magisterium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maria Alvarez | José Bonifácio | 3 | 1 year and a half |

| Nilce Lodi | São José do Rio Preto | 1 | 7 years |

| Ivanilde Afonso | Mendonça, São José do Rio Preto, Poloni | 3 | 3 years |

| Irce Elias | Guapiaçu, Planalto | 2 | 5 years |

| Yara Aude | Piragi, José Bonifácio, Cedral | 5 | 10 years |

| Maria Inês | São João do Iracema, general Salgado, Potirendaba | 4 | 5 years and a half |

| Maria Nirce | Nhandeara, Nova Lusitânia, Floreal | 4 | 4 years |

| Jorge Salomão | Bady Bassitt | 2 | 3 years |

| Palmira Miqueletti | Nova Aliança, Tanabi, Potirendaba | 4 | 3 years and a half |

| Sônia Azem | Monte Belo, Tanabi, São José do Rio Preto, Nova Aliança | 4 | 3 year and a half |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The systematized data showed the itineraries traveled in the rural magisterium by the teachers, whose permanence, for the most part, was four years. Thus, based on the writing of Certeau (2012), understood this turnover in rural schools, as a space of daily life full of strategies and tactics adopted by teachers, on condition that they had to enter the rural environment and then be removed to other schools closer to the urban center.

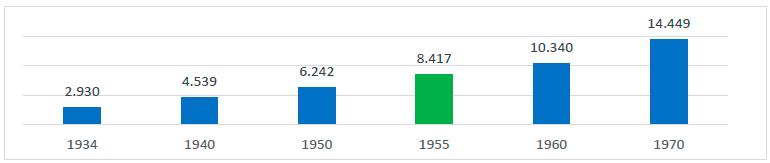

Between 1930 and 1960 intensified in the state of São Paulo policies aimed at the schooling of the rural population aiming at the modernization of Brazilian society, which implied to remedy the unfitness of the rural man, without professional preparation, to be integrated into a society in full industrial and urban development. This expansion of rural primary schools can be observed in graphic 1.

Source: Leite (2018, p. 40)

Graphic 1: Number of rural schools in the state of São Paulo -1934-1970.

The expressive growth of schools occurred in the 1950s as a result of the creation of 8,417 emergency schools (decree 24,400, of March 11, 1955), which added to the total of those created at the beginning of the period, totaling 14,650 schools. The number of emergency schools established in 1960, according to Leite (2018), was exclusively in the rural area.

The need for expansion in the São Paulo school system has led to precarious operating conditions in schools. In this sense, teachers' narratives are revealing when describing the situation of school buildings in rural schools where they worked. Thus, each teacher portrayed the reality they were able to remember.

In this regard, teacher Maria Alvarez recalled: "It was a simple room, with small desks, designed to sit in two students. A very small blackboard, that sometimes was not enough to write some subjects". Teacher Maria Nirce also reported “It was that house... opening window... the door to enter with a key. It had nothing. A blackboard. One room. A pantry. A wood stove.

Teacher Irce Elias mentioned "adapted houses, with doors, windows and rustic floors. They had no ceilings, it was just the roof. All were masonry, but with a single room. There were blackboards, double chairs, tables and cabinets".

However, the narrative of teacher Palmira Miqueletti revealed a rural school considered by her as "good". Thus, she reported:

Laranjal Farm was good, in terms, it was a real school. It was built to be a school. It was a classroom with a blackboard and everything. Here in Santa Inês as well. And in Fulgêncio as well. It was schools that were created for this. Now in Monte Belo, it was like this: the classroom was the room of a house, here were the desks, here was the blackboard for them to see, here was our table and here the little cabinet. It had an L-shape. Now, the others already had... The only difference of Santa Inês is that it had a stove. We made the soup. Sometimes the kids brought us vegetables. Things like that, because they gave the basics, the pasta...and we added the vegetables. Not the meat. None. (PALMIRA MIQUELETTI MARRA, 2019).

For teacher Maria Inês, to be a teacher in rural schools was to "kill a lion a day". She described the rural school as a place "[...] depressing. It had a place on the blackboard that you couldn’t even write. It was a small room. It was very small. It had two windows, a door in the background and a shelf that served as a cabinet, with a cloth in the front to cover. That was it. Poor! Poor!". The furniture, according to her

It was those two-seater desks. Here was the bench... but here was the countertop… the backrest was the back of the table of the person sitting behind, who sat on another bench... There were people who were so naughty, that when it was time to sit down they would release the body like this and shake their desk and fall all over the floor of the student sitting behind. Student’s prank, right? (laughs). Then you had to get mad. There was a little blackboard. (MARIA INÊS MAGNANI SALOMÃO, 2019)

As teacher Nilce Lodi pointed out, the school in the rural area had only one teacher, there were no paid assistants. She was responsible for organizing the school, making decisions about cleaning the building, the hall, the courtyard, providing hygienic conditions for the supply of drinking water and adequate sanitary facilities, but always relied on the collaboration of the older students, boys and girls. She provided the indispensable material for the execution of the tasks and guided their execution.

Nilce Lodi explained that the Scaff Farm provided the building to run the school, adapting the old office of the farm, turning it into a classroom with the furniture: a table of wide boards, the benches, the blackboard, a cabinet for the books and the earthenware (pot) for water, in addition to the chair and the table for the teacher. In her conception, this was at the time the basic material of rural schools in the interior of São Paulo.

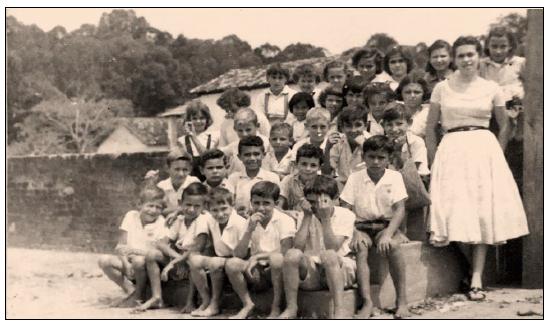

On the Scarf farm, the school was adapted from the owner’s old office. The building comprised a porch, a rectangular room, with two doors and two windows, lined and covered with tiles. The school was located next to the headquarters and large yards used for drying coffee and next to the warehouses. In front of it there were several houses of masonry, covered with tiles, plastered, painted, with a large yard; and a nearby colony with employees in charge of dairy cattle and further away from the vegetable garden. From this school, the teacher kept some photographs as can be seen in image 1.

Source: Personal archive of teacher Nilce Apparecida Lodi Rizzini.

Image 1: Students of the Scaff Farm Mixed School (1956)

The image depicts the students sitting on a concrete staircase, with 5 stair steps, in front of the Scaff Farm Mixed School. Next to the students is the intern Vanda Carrazone, student of the Normal School of Mirassol, interning with the class of 1956. On that day, as can be seen, there were 29 students, mostly male. The depiction expressed by the image was that all students wore uniforms, as they were wearing a white shirt as clothing, however, the color of the boys' shorts in front are not the same. As for the girls, it is not possible to identify what kind of clothes they wear at the bottom (skirt or short) and much less the color, because they were behind the boys at the time of the photo. The children in front are all barefoot, which was very common at that time when shoes were considered luxury and expensive. Teacher Rizzini did not appear in the photo, according to her, because she was the photographer.

Final considerations

The paper highlighted how entering the career of primary teachers in the state of São Paulo was linked to teaching in rural areas. Unlike other Brazilian states, the number of lay teachers working in rural schools was small; this is because the expansion of normal education was bigger in this state in relation to both public and private schools. Nevertheless, the offer of trained teachers triggered other adverse problems for the rural magisterium. It can be said that the training became a factor of departure of the primary teacher on the field, since the normalists (women, in their majority), for their level of schooling of medium degree, very high for the whole population, and a school education marked by urban culture, preferred to stay in the cities.

On the other hand, the public authorities, at state and municipal levels, did little to improve the conditions of infrastructure and work in rural schools. Difficulties of access, transportation and housing for teachers in the countryside, low salaries and the precarious material conditions of rural primary schools (absence of adequate building for school operation, absence of furniture and provision of school materials) did not make rural school attractive to teachers.

Thus, the contradiction between the offer of teachers with normalist training and the problems of providing rural schools in the state of São Paulo can be seen as sides of the complex dynamics of the development of capitalism in the countryside and in the cities. Not by chance, the admission of teachers in rural schools has become one of the major problems of public education in São Paulo. The simple creation of schools without compensatory measures to alleviate the difficulties of life in the rural environment were not enough and the problem of provision dragged on throughout the twentieth century (why not say, until today!). To soften it, the strategy of the public powers was to create mechanisms to compel teaching in the field by subjecting the masters to point counting, title tests and the prize chair system, among other strategies.

The beginning of the teaching career in São Paulo, generally, occurred in rural primary schools, a requirement laid down in the state legislation since the beginning of the Republic, whose criteria determined the effective exercise in office in isolated establishments. Strictly speaking, the teacher should work in interstices for up to two years to plead for vacancies in the selection process of removal. Thus, the narratives demonstrated how the teachers were creating tactics to promote education in rural primary schools in the interior of São Paulo.

As analyzed in the text, numerous laws were instituted between the 1940s and 1970s to prescribe the requirement of entering the career of primary teachers in isolated schools located in rural areas, although with little effectiveness. These demands, instead of encouraging teachers to stay in rural areas, caused other problems such as intermittence (teachers passing through several schools seeking those that were easier to access and closer to the urban area) and diligent compliance with the basic criteria necessary to claim removal to an urban school. This explains the discontinuous and transitory itinerary in the field of most teachers interviewed.

The few years worked in rural primary schools in the region of São José do Rio Preto were remembered by the teachers as a time of difficulties, a "baptism of fire" in the magisterium marked by many vicissitudes, but also for the confirmation of teaching as a professional career. The peculiarities of these trajectories highlight the problems of rural education in the state of São Paulo and the relevance of rural schools for rural workers.

REFERENCES

ALCÂNTARA, Wiara Rosa Rios. A sala de aula foi o meu mundo: a carreira do magistério em São Paulo (1920-1950). Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 38, n. 2, p.289-305, abr./jun. 2012. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-97022012000200002 [ Links ]

ALMEIDA JÚNIOR, Antônio. A escola pitoresca e outros trabalhos. Companhia Editora Nacional, São Paulo, 2ª ed., Série 3ª da Biblioteca Pedagógica Brasileira, 1951. [ Links ]

ÁVILA, Virgínia Pereira da Silva. História do ensino primário rural em São Paulo e Santa Catarina (1921-1952): uma abordagem comparada. 2013. Tese (Doutorado em Educação Escolar) - Faculdade de Ciências e Letras, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Araraquara, 2013 [ Links ]

CERTEAU, Michel de. A invenção do cotidiano. 19. ed. Tradução de: Ephraim Ferreira Alves. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2012. [ Links ]

CERTEAU, Michel. A escrita da história. Tradução de Maria de Lurdes Menezes. 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 2013. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. O mundo como representação. Estudos Avançados (online), São Paulo, v.5, n.11, p. 173-191, 1991. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-40141991000100010 [ Links ]

LE GOFF, Jacques. História e Memória. 5 ed. Campinas - SP: Editora da Unicamp, 2003 [ Links ]

HALBWACHS, Maurice. A memória coletiva. São Paulo: Centauro, 2006. [ Links ]

LEITE, Kamila Cristina Evaristo. Memórias de professoras de escolas rurais: (Rio Claro-SP, 1950 a 1992). 2018. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Marília, 2018. [ Links ]

LIMA, Sandra Cristina Fagundes; ASSIS, Danielle Angélica. Poetas de seus negócios: Professoras leigas das escolas rurais (Uberlândia-MG, 1950 a 1979). Cadernos de História da Educação, 12, 313-332, 2013. [ Links ]

LIMA, Sandra Cristina Fagundes. Eu aprendi e ensinei também ao mesmo tempo: professores leigos na história da escola rural. Revista de Educação Pública, 27, 405-423, 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29286/rep.v27i65/1.6588 [ Links ]

MEIHY, José Carlos Sebe Bom. Manual de história oral. 3. ed. São Paulo: Loyola, 2000. [ Links ]

MEIHY, José Carlos Sebe Bom. História oral: como fazer, como pensar. 2. ed. São Paulo: Contexto, 2013. [ Links ]

MORAES, Agnes Iara Domingos. O ensino primário tipicamente rural no estado de São Paulo: um estudo sobre as granjas escolares, os grupos escolares rurais e as escolas típicas rurais (1933-1968). 2014. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Marília, 2014. [ Links ]

ORANI, Angélica Pall. Apontamentos sobre a história das escolas rurais em São Paulo (1930-1970). Anais Eletrônico do IX Congresso Brasileiro de História da Educação, João Pessoa, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, 2017, p.469-480. [ Links ]

RIZZINI, Nilce Apparecida Lodi. Álbum de fotos. Fotografia da turma de alunos da Escola Mista da Fazenda Scaff. São José do Rio Preto, 1956. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (ESTADO). Lei nº 930, de 13 de agosto de 1904. Modifica várias disposições das leis em vigor sobre instrucção publica do Estado. Alesp, [1904]. Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/lei/1904/lei-930-13.08.1904.html. Acesso em: 15 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (ESTADO). Decreto nº 5.804, de 16 de janeiro de 1933. Institui a carreira no magistério público primário. Alesp, [1933]. Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/ repositorio/legislacao/decreto/1933/decreto-5804-16.01.1933.html. Acesso em: 09 mar 2021. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (ESTADO). Decreto nº 5.884, de 21 de abril de 1933. Institue o Código de Educação do Estado de São Paulo. Alesp, [1933a]. Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto/1933/decreto-5884-21.04.1933.html. Acesso em: 09 mar 2021. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (ESTADO). Decreto nº 6.197, de 9 de dezembro de 1933. Introduz modificações na carreira do magistério primário. Alesp, [1933c]. Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto/1933/decreto-6197-09.12.1933.html. Acesso em: 15 mar 2021. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (ESTADO). Decreto nº 6.947, de 6 de fevereiro de 1935. Consolida disposições anteriores na carreira do magistério primária, instituída pelo Decreto nº 3.884, de 21 de abril de 1933 e alternada pelo Decreto nº 6. 197 de 9 de dezembro de 1933. Alesp [1935]. Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto/1935/decreto-6947-06.02.1935.html. Acesso em: 15 mar 2021. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (ESTADO). Decreto-Lei nº 12.427, de 23 de dezembro de 1941. Consubstancia novas disposições relativas à carreira do magistério público primário, e dá outras providências. Alesp [1942]. Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto.lei/1941/ decreto.lei-12427-23.12.1941.html. Acesso em: 15 mar 2021. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (ESTADO). Decreto-Lei nº 12.801, de 13 de julho de 1942. Dispõe sobre concessão de vantagens aos diplomados pela Escola Normal “Caetano de Campos. Alesp [1942]. Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto.lei/1942/ decreto.lei-12801-13.07.1942.html. Acesso em: 15 mar 2021. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (ESTADO). Decreto nº 15.993, de 29 de agosto de 1946. Dá regulamento ao estabelecimento no § 1º, do artigo 2º, do decreto n. 12.801, de 13-7-1942. Alesp [1946]. Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto/1946/decreto-15993-29.08.1946.html. Acesso em: 15 mar 2021. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (ESTADO). Lei nº 467, de 30 de setembro de 1949. Dispõe sobre concurso de ingresso e reingresso ao magistério público. Alesp, [1948]. Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/lei/1949/lei-467-30.09.1949.html. Acesso em: 15 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (ESTADO). Decreto nº 24.400, de 11 de março de 1955. Dispõe sobre a instalação de classes de emergência, de ensino primário. Alesp, [1955]. Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto/1955/decreto-24400-11.03.1955.html. Acesso em: 19 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (ESTADO). Lei nº 7.378, de 31 de outubro de 1962. Dispõe sobre o concurso de ingresso e reingresso no magistério público primário do Estado e dá outras provid6encias. Alesp, [1962c]. Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/lei/1962/lei-7378-31.10.1962.html. Acesso em: 16 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (ESTADO). Decreto nº 41.277, de 24 de dezembro de 1962. Regulamenta a Lei n.º 7.378, de 31 de outubro de 1962, que dispõe sôbre o Concurso de Ingresso e Reingresso no Magistério Público Primário do Estado, e dá outras providências. Alesp, [1962d]. Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto/1962/decreto-41277-24.12.1962.html. Acesso em: 16 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

SIQUEIRA, Maryluze Souza Santos. Revolver a terra, regar a memória e semear a história: o campo de formação do professor primário rural em Sergipe (1946 - 1963). Tese (Doutorado em Educação), Universidade Tiradentes, Aracajú, 2019. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Rosa Fátima; FARIA FILHO, Luciano Mendes. A Contribuição dos estudos sobre Grupos Escolares para a Renovação da História do Ensino Primário no Brasil. In: VIDAL, Diana Gonçalves. (Org.). Grupos Escolares no Brasil: cultura escolar primária e escolarização da infância no Brasil (1893-1971). Campinas: Mercado de Letras, 2006, p. 21-56. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Rosa Fátima de. A escola pública primária no Estado de São Paulo: políticas de expansão e de renovação pedagógica (1930 - 1961). In: FURTADO, A.C.; SCHELBAUER, A. R.; CORRÊA, R. L. T. (Org.). Itinerários e singularidades da institucionalização e expansão da escola primária no Brasil (1930 - 1961). 1ed. Maringá: UEM, 2019, p. 17-54. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Rosa Fátima de. ÁVILA, Virgínia Pereira da Silva de. Para uma genealogia da escola primária rural: entre o espaço e a configuração pedagógica (São Paulo, 1889-1947). Roteiro, v. 40, p. 293-310, 2015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18593/r.v40i2.7462 [ Links ]

SOUZA, Rosa F.; SILVA, Vera Lucia G.; SÁ, Elizabeth F. Por uma teoria e uma história da escola primária no Brasil. Investigações comparadas sobre a escola graduada (1870 - 1930). Cuiabá: EdUFMT, 2013. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Rosa Fátima de. MORAES, Agnes Iara Domingos. O “ensino típico rural”: contribuições para a historiografia da educação rural no Brasil. Revista Documento/Monumento, Mato Grosso, vol. 15, n. 1, p.277-305, set/2015. [ Links ]

THOMPSON, Paul. A voz do passado. 2 ed. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 1998. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

Irce Elias Pires da Costa. Relato oral sobre formação e docência rural em São Paulo. Entrevista concedida a Noely Costa Dias Garcia. São José do Rio Preto/SP, 18 maio 2019. [ Links ]

Ivanilde Afonso Prudêncio. Relato oral sobre formação e docência rural em São Paulo. Entrevista concedida a Noely Costa Dias Garcia. São José do Rio Preto/SP, 8 jan. 2020. [ Links ]

Jorge Salomão. Relato oral sobre formação e docência rural em São Paulo. Entrevista concedida a Noely Costa Dias Garcia. São José do Rio Preto/SP, 25 maio 2019. [ Links ]

Maria Alvarez Romano. Relato oral sobre formação e docência rural em São Paulo. Entrevista concedida a Noely Costa Dias Garcia. São José do Rio Preto/SP, 4 mar. 2019. [ Links ]

Maria Inês Magnani Salomão. Relato oral sobre formação e docência rural em São Paulo. Entrevista concedida a Noely Costa Dias Garcia. São José do Rio Preto/SP, 25 maio 2019. [ Links ]

Maria Nirce Previdentes Sanches. Relato oral sobre formação e docência rural em São Paulo. Entrevista concedida a Noely Costa Dias Garcia. São José do Rio Preto/SP, 4 mar. 2019. [ Links ]

Nilce Aparecida Lodi Rizzini. Relato oral sobre formação e docência rural em São Paulo. Entrevista concedida a Noely Costa Dias Garcia. São José do Rio Preto/SP, 9 jan. 2020. [ Links ]

Palmira Miqueletti Marra da Silva. Relato oral sobre formação e docência rural em São Paulo. Entrevista concedida a Noely Costa Dias Garcia. São José do Rio Preto/SP, 18 maio 2019. [ Links ]

Sônia Aparecida Azem. Relato oral sobre formação e docência rural em São Paulo. Entrevista concedida a Noely Costa Dias Garcia. São José do Rio Preto/SP, 4 maio 2019. [ Links ]

Yara Aparecida Aude. Relato oral sobre formação e docência rural em São Paulo. Entrevista concedida a Noely Costa Dias Garcia. São José do Rio Preto/SP, 21 setembro 2019. [ Links ]

2The first edition of this book was published in 1934 and the second in 1951. The work is divided into four chapters, as follows: I - The picturesque school; II - Teacher training; III - Administration and teaching; IV - Guidelines and Bases of National Education. Chapter II was structured on the basis of a survey carried out by the author with 37 graduates of the normal school. In this chapter, Almeida Júnior presents the reasons for entering the normal course and the students' understanding of the teaching career. In addition, when dealing with the greatness and miseries of rural teaching (third subtitle of the chapter), the author highlights the process of entry of a teacher in the rural school, revealing the living and working conditions in the exercise of rural teaching.

3Reversion is the possibility of re-entry for candidates who have already been teachers and have left the post. The reversion to primary teaching is prescribed by the Education Code of 1933, article 336, and consolidated by Decree 6,947, article 15.

4As can be seen, the aforementioned Faculty of Philosophy, Sciences and Languages of Catanduva (FAFICA) was established on July 29, 1966, through Municipal Law 792/66, and transformed in September of the same year, by Law 803/66, into a Municipal Autarchical Entity, with legal personality of Public Law, constituting a non-profit entity, with its headquarters and jurisdiction in the City and County of Catanduva. Available at: https://www.fafica.br/page.php?q=institucional.

5The decree referred to by the teacher was published on February 11, 1972, during the administration of Laudo Natel, governor of the state of São Paulo, which ensured, during 1972, "priority to the use of candidates classified in the last state primary teaching entrance exam, to regency of common and emergency schools, provided they were enrolled in their respective schools. (SÃO PAULO, 1972, p. 1)

6Among the defenders of the common school were Fernando de Azevedo and Almeida Júnior, pioneers of Educação Nova, who advocated a common education in urban and rural elementary school, however, Sud Mennuci, one of the main defenders of ruralism, advocated a school with its own program for rural children.

7To have an idea of the number of these establishments, Moraes (2014) identified at the year 1937, the existence, in the state of São Paulo, of 628 school groups and 3,827 isolated schools, and, in that same period, there were four School Farms and 29 Rural School Groups. However, in the period from 1933 to 1968, she managed to identify 253 typical rural schools, distributed as follows: 5 (school farm); 82 (rural school groups) and 76 (typical rural schools ).

Received: July 11, 2022; Accepted: September 26, 2022

texto en

texto en