Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.22 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 07-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v22-2023-168

Artigos

The Science Fair of São Paulo in the Brazilian press (1960-1976)1

1Instituto Nacional de Comunicação Pública da Ciência e Tecnologia (Brasil). Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (Brasil). danilomagalhaes@protonmail.com

2Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Brasil). Instituto Nacional de Comunicação Pública da Ciência e Tecnologia (Brasil). Bolsista de Produtividade em Pesquisa do CNPq - Nível 1B. luisa.massarani@fiocruz.br

3Fundação Centro de Ciências e Educação Superior a Distância do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Brasil). Bolsista de Produtividade em Pesquisa do CNPq - Nível 2. jessicanorberto@yahoo.com.br

Science fairs were introduced and popularized in Brazil during the 1960s and 1970s as part of the science education renewal movement. In this paper, the authors analyzed the journalistic coverage of the São Paulo Science Fair, considered the first in the country. A search was performed in the National Library’s Digital Library and in digital newspaper archives. The newspapers presented the São Paulo Fair as a reference standard for the organization of fairs across the country and internationally. Analysis also revealed that newspapers argued that fairs played an important role in the educational reform movement and in the legitimization of science, as part of a national development project based on the strengthening of scientific and technological capital.

Keywords: Science Education; José Reis; IBECC

As feiras de ciências foram introduzidas e popularizadas no Brasil nas décadas de 1960 e 1970, como parte do movimento renovador do ensino de ciências. Neste artigo, tivemos como objetivo analisar a cobertura jornalística da Feira de Ciências de São Paulo, considerada a primeira no país. Foi feito levantamento na Hemeroteca Digital da Biblioteca Nacional e nos acervos digitais de jornais, a partir do qual identificamos 248 textos de 15 jornais, que compuseram o corpus de nossa análise. Os jornais apresentaram a Feira de São Paulo como a mais desenvolvida do Brasil, servindo de referência para a organização de feiras pelo país e internacionalmente. A análise das matérias permitiu observar também que os jornais defenderam que as feiras tinham um papel importante no movimento que visava a reforma educacional e na legitimação da ciência, inseridas em um projeto de desenvolvimento nacional baseado no fortalecimento da ciência e da tecnologia.

Palavras-Chave: Ensino de Ciências; José Reis; IBECC

Las ferias de ciencia se introdujeron y popularizaron en Brasil durante las décadas de 1960 y 1970, como parte del movimiento renovador de la educación científica. En este artículo, tuvimos como objetivo analizar la cobertura periodística de la Feria de Ciencias de São Paulo, considerada la primera del país. Se investigó en las bibliotecas digitales de la Biblioteca Nacional y de periódicos. Los periódicos presentaron la Feira de São Paulo como la más desarrollada de Brasil, sirviendo de referencia para la organización de ferias en todo el país e internacionalmente. El análisis de los textos también mostró que los periódicos argumentaron que las ferias jugaron un papel importante en el movimiento de reforma educativa y en la legitimación de la ciencia, como parte de un proyecto de desarrollo nacional basado en el fortalecimiento de la ciencia y la tecnología.

Palabras clave: Enseñanza de las ciências; José Reis; IBECC

Introduction

Brazilian educators and scientists promoted a set of proposals and initiatives from 1950 to 1970 that became known as the "science education renewal movement" (CASSAB, 2015; KRASILCHIK, 2000). This movement came to prominence during a period of scientific institutionalization and the fight for secondary school "modernization", and was influenced by similar foreign curricula projects, particularly those of the United States. It had as one of its aims the production of a more practical and experimental education system, striving to accomplish this by updating science education materials and curriculum content, redefining the role of science teachers in the classroom, and incentivizing students' intellectual autonomy and capacity for critical thinking (ABRANTES, 2008; VALLA et al, 2014: CASSAB, 2015). Another of the movement's goals was to prepare higher achieving students for scientific careers in order to further scientific and technological progress in the country, which was understood to be dependent on the then ongoing industrialization process (KRASILCHIK, 2000; ABRANTES, 2008).

Many of the stakeholders directly involved in this movement were connected to such institutions as the "Instituto Brasileiro de Educação, Ciência e Cultura" (Brazilian Institute of Education, Science, and Culture) (IBECC), the "Fundação Brasileira para o Desenvolvimento do Ensino de Ciências" (Brazilian Foundation for the Development of Teaching in the Sciences) (FUNBEC), and the six "Centros de Ciências" (Science Centers) (CECIs) in Salvador, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, Recife, and Porto Alegre (MANCUSO; LEITE FILHO, 2006; ABRANTES, 2008; BORGES et al, 2012).

Founded in 1946 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), IBECC was a beacon for science education and communication in Brazil, synergizing and concentrating the projects of individual teachers and scientists that had previously been sparse and disconnected (KRASILCHICK, 2000; ABRANTES, 2008). With its initial headquarters on the campus of the "Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo" (São Paulo University Medical College) (FMUSP), IBECC carried out innovative programs such as the organization of contests, clubs, and science fairs, as well as the translation and editing of primary and secondary school level educational materials and experimental kits, with the support of the federal government and state secretaries of education, as well as international agencies such as the Ford Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation (ABRANTES, 2008; ABRANTES; AZEVEDO, 2010).

The organization of science fairs in the 1960s and 1970s was one of main initiatives both of IBECC and of the science education renewal movement (MANCUSO; LEITE FILHO, 2006; ABRANTES, 2008). Science fairs were developed in the United States as extracurricular educational activities in the first half of the twentieth century together with other primary school reform movements (TERZIAN, 2013). These were supported by investments in science, technology, and science education during the post-World War II period and throughout the Cold War era (KRASILCHIK, 2000; TERZIAN, 2013).

Inspired by U.S. fairs, an event considered the first Brazilian science fair - the “Primeira Feira de Ciências de São Paulo” (First São Paulo Science Fair) - was held in 1960 (MANCUSO; LEITE FILHO, 2006). This fair was organized by IBECC and brought together 432 projects from 25 schools in the São Paulo capital region. It was visited by approximately 7,000 people (ABRANTES, 2008). The implementation of this fair was the culmination of the vision of José Reis, an IBECC member who had been advocating for the organization of science fairs in the country since 1950, considering them to be an important tool for the improvement of science education and engagement of young people in scientific careers (REIS; GONÇALVES, 2007; MASSARANI et al., 2018).

José Reis was one of the most important individuals in Brazilian science communication during his career (MASSARANI, et al., 2018). In the 1940s, Reis began to systematically author articles on science, technology, and science education for the Folha Group, an activity he continued for 55 years until his death in 2002. He held the position of editorial director at the Folha de São Paulo newspaper from 1962 to 1967. During this period, he actively fomented the newspaper's coverage, organization, financing, and awarding of prizes to the country's first science fairs, becoming a major protagonist in the support of such extracurricular educational activities (MASSARANI et al, 2018). In 1965, Reis published a booklet, titled "Feiras de Ciência: uma revolução pedagógica" (Science Fairs: an educational revolution), in which he condensed his experiences following science fairs carried out during the early 1960s and described the key educational objectives of such fairs (REIS, [1965] 2018). In 1968, he included this text in a collection and released "Educação é Investimento" (Education is Investment) (REIS, 1968), which elevated him to prominence in debates of the era on education and public education policy. In recognition of his efforts, he received the Kalinga Prize for the Popularization of Science in 1975, awarded by UNESCO. In 1978, the "Centro Nacional de Pesquisa" (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development) (CNPq) created the “José Reis Prize for Science Communication” in his honor2.

During the 1960s, the São Paulo Fair continued to hold subsequent editions and science fairs disseminated throughout Brazil, first in the state of São Paulo and then the rest of the country (REIS, [1965] 2018). The development and popularization of science fairs in Brazil during the 1960s gained visibility through news coverage, exciting students and educators alike. José Reis described this process as a "science fair movement" (cf. REIS, [1965] 2018) that was part of the "pedagogical renewal of science" (REIS, 1966, p.1), responsible for making science fairs "more attractive and better taught" (REIS, [1965] 2018), as described by Abrantes (2008, p.156-157):

The fair experience was well-adapted to the precarious condition of Brazilian secondary schools and laboratories, helping to remedy the extant deficiency in formal education and proposing experiments that were adequate to the local reality of the places in which they were carried out (REIS & GONÇALVES, 2000, p. 55), mobilizing the population in rural towns and contributing to the integration of schools and society.

Little is known about the history of Brazilian science fairs, with literature produced on the subject being exceptionally scarce. Among the exceptions, a chronicle produced by Ronaldo Mancuso and Ivo Leite Filho for the "Programa Nacional de Apoio a Feiras de Ciências" (National Science Fair Support Program) (Fenaceb) stands out (MANCUSO; LEITE FILHO, 2006). Most of the information available can be found in José Reis' own writings and works written about the science education renewal movement, of which fairs are only tangentially referenced (cf. KRASILCHIK, 2000; ABRANTES, 2008; BORGES et al, 2012; VALLA et al., 2014; CASSAB, 2015). The precise number of editions of the São Paulo Science Fairs that were held, as well as the reason for their discontinuation, which appears to have occurred during the 1970s, are among the pieces of information that are unverifiable in the extant literature.

As previously mentioned, period newspapers systematically covered these science fairs and as such are an important source of information in the reformulation of fairs from the 1960s and 1970s. This article takes as its precise objective the analysis of the journalistic coverage of the São Paulo Science Fairs over the course of the decades in question. The authors seek to understand how newspapers framed science fairs and their role in the science education renewal movement and science communication, as well as reconstitute a part of the Fair's history.

This study falls under the scope of the "Instituto Nacional de Comunicação Pública da Ciência e Tecnologia" (National Institute of Public Communication for Science and Technology) (INCT-CPCT), with support from the CNPq and the “Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro” (Research Support Foundation of Rio de Janeiro) (FAPERJ), and is part of a larger research effort on the impact of José Reis on the process of introduction and diffusion of science fairs in Brazil. The authors believe that this study additionally supports a deeper understanding of a process that is little studied in the extant literature on the history of education, science, and science communication in the country.

1. Methodology

This document-based, qualitative study was supported by the resources available at the "Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira da Biblioteca Nacional" (National Library Digital Newspaper Archive) (BNDigital)23 . BNDigital was accessed free of charge over the internet and is an ample archive including diverse newspapers, magazines, and other periodicals as well as cartographic and iconographic documents, manuscripts, bibliographies, and audio files, constituting as a whole a highly relevant source. Additionally, the authors consulted the digital archives of O Globo, O estado de São Paulo, and Folha de São Paulo, the three most representative newspapers in terms of circulation and reach in the Southeastern region, as well as in the country as a whole. This consultation was executed by searching for variations on the phrase “feira de ciências” ("science fair"), such as “feiras de ciências”, “feira de ciência” e “feiras de ciência” during the period of interest. Only those materials that cited the São Paulo Science Fair were selected for citation. The São Paulo Science Fair was chosen given its status as the first Brazilian science fair and its recognition in the literature on the history of science education in the country as an important step in IBECC’s implementation of a more practical and experimental educational system (ABRANTES, 2008).

After source selection, the textual content of each document was analyzed in order to identify key events and actors in the event’s trajectory. Locations and dates of the different editions were collected, as well as the number of participants, number of visitors, and official sponsors and supporters. Descriptions of the editions and the motivations mentioned for the fair in news coverage were also observed. The authors also analyzed the profile of exhibiting students at the Fair and the prizes awarded to the best projects. Patterns in exhibit projects were noted, as well as how those patterns changed over time. All of this information served to reconstitute the history of the Fair, as these data were not available in a systematized form in the literature. The authors seek to use this bibliography to investigate the history of science education in Brazil and of science fairs in such a way as to contextualize some of the issues presented by the source material.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Coverage of the São Paulo Science Fair in newspapers

In total, 248 documents mentioning the São Paulo Fair were found in the following 15 newspapers, dated between 1960 and 1976: Folha de São Paulo (SP) (111 articles), O Estado de São Paulo (SP) (49 articles), Jornal do Brasil (RJ) (24 articles), Correio Paulistano (SP) and Diário da Noite (SP) (14 articles each), Correio da Manhã (RJ) (12 articles), A Tribuna (SP) (9 articles), Diário de Notícias (RJ) (4 articles), Última Hora (PR) (3 articles), A Noite (RJ) and O Jornal (RJ) (2 articles each), Última Hora (RJ), O Fluminense (RJ), Jornal do Commercio (RJ) and Jornal dos Sports (RJ) (1 article each).

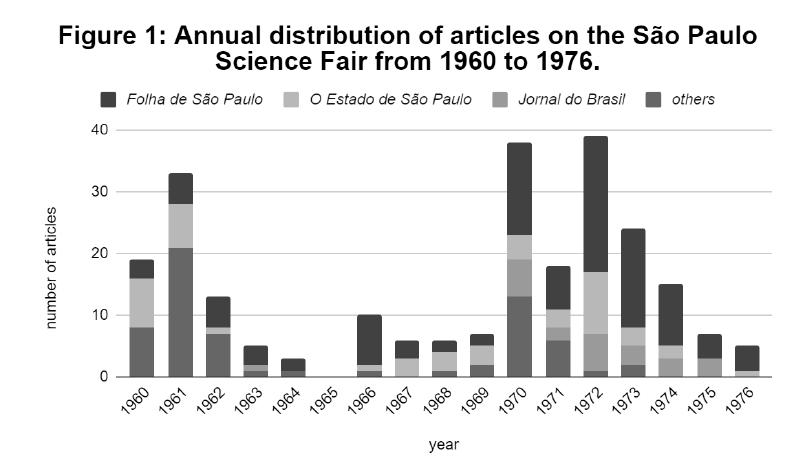

The Folha de São Paulo engaged in the most extensive coverage of the various editions of the Fair, followed by O Estado de São Paulo. This is explained, in part, by the advocacy and influence of José Reis at the Folha Group, as previously mentioned (MASSARANI et al, 2018). The distribution of these articles over the years can be observed in Figure 1.

In its three first years, the Fair garnered significant attention from newspapers (19 articles in 1960, 33 in 1961, and 13 in 1962). The Folha de São Paulo, O Estado de São Paulo, Correio Paulistano and Diário da Noite, all from the state of São Paulo, were the newspapers that covered the events most. There was a reduction in the number of articles about the fair from 1963 to 1969. No articles could be found referencing the event in 1965, leading the authors to believe that the Fair did not occur that year. The year of 1965 was turbulent due to the military coup in 1964. Mentions in publications recommenced in 1966, mostly in editions of the Folha de São Paulo, then directed by José Reis.

No articles referencing the end of the Fair were located. From 1977 on there were no publications. Abrantes (2008, p.280) indicates changes in the process of the institutionalization of science in Brazil, internal shifts in the identity of IBECC as an institution, and alterations in UNESCO’s activities on the international stage that led to a gradual reduction in its capacity throughout the 1970s and 1980s as causative factors.

Visual resources employed in the articles mostly consist of photographs. Maps of the Fair’s location at Ibirapuera Park and maps of the locations of stands inside of the fairs were also published by the newspapers. The 59 total photographs depict similar scenes: the Fairs seen from above (demonstrating its broad appeal to visitors), authority figures at opening ceremonies or visiting the Fairs, young people at the various editions, students assembling stands on the days leading up the Fair and - in the vast majority of the photographs - students at their stands posing with their experiments and apparatuses or demonstrating and explaining them to the visiting public. Photographs of students looking through microscopes and telescopes were also published. The majority of the students in the photographs are white and male.

2.2. History and involved parties

Bibliographical analysis indicates that 15 editions of the São Paulo Science fair were organized between 1960 and 1976. In its three first years, the Fair took place at the Prestes Maia Gallery, in downtown São Paulo. As the number of exhibitors and visitors grew, the Fair was moved first to the Cásper Líbero Foundation, on Paulista Avenue (1964), then to the Pacaembu Gymnasium (1966-1967), and lastly to the Biannual Pavilion, in Ibirapuera Park, where the Fair was held for its final nine consecutive years (1968-1976).

The principal organizers of the Fair were sociologist and educator Maria Julieta Ormastroni and biochemist Isaías Raw. Both were frequently interviewed by newspapers. Ormastroni is cited as the organizer of almost all of the editions. Other names mentioned as coordinators include Paulo Mendes da Rocha (1962), Cícero Wolfie (1968), João Paulo Brito Serra (1970), Antônio Teixeira (1972), and Jaime Nazário (1974).

Maria Julieta Ormastroni was instrumental in the incentivization of extra-curricular activities as the executive director of IBECC's São Paulo branch. Together with Isaías Raw, she was responsible for the creation of numerous informal science education programs, such as the “Scientists of Tomorrow” contest, which occurred annually at the meetings of the “Sociedade Brasileira para o Progresso da Ciência” (Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science) (SBPC). In some editions of the Fair, it can be affirmed that the winning students were automatically classified for the contest. Ormastroni was also invited by Reis to write about science in the Folhinha, the supplemental publication of the Folha de São Paulo for children, which she did for 25 years. Some of the documents analyzed in this article were Ormastroni’s publications in the Folhinha, which included suggestions for science fair experiments as well as announcements and publicity for the Fair.

Isaías Raw held leadership roles for many years at institutions dedicated to science education and communication (RAW, 2007; ABRANTES, 2008). Between 1950 and 1969, he founded the “Editoras da Universidade de São Paulo” (São Paulo University Editors) and the “Editoras da Universidade de Brasília” (Brasília University Editors), in addition to creating the “Fundação Carlos Chagas” (Carlos Chagas Foundation) and the “Curso Experimental de Medicina da FMUSP” (FMUSP Experimental Medicine Program). He was also the scientific director at IBECC from 1955 to 1969 and the director of FUNBEC, leading numerous projects at both institutions and becoming one of the most important figures in the science education renewal movement. According to Abrantes (2008, p.148), Isaías Raw had “a central role in the dynamization of IBECC/SP’s science communication activities, displaying charismatic and engaging leadership on an innovative proposal for science education”. After the passing of Institutional Act n˚5, Raw was persecuted and exiled by Brazil’s military dictatorship in 1969, later working in Israel and universities in North America. He returned to Brazil in 1979 and began work at the Butantan Institute, where he worked until his retirement.

Analysis of the collected bibliography revealed that IBECC fomented numerous partnerships over the years in order to support the various editions of the Fair. The first Fair, in 1960, was supported by the “Campanha de Aperfeiçoamento e Difusão do Ensino Secundário” (Campaign for the Improvement and Dissemination of Secondary Education) (CADES)34 , the “Federação das Indústrias de São Paulo” (Industrial Federation of São Paulo) (FIESP), and São Paulo’s state and municipal secretaries of education. No sponsorship information was found for the following four editions. The Folha de São Paulo began supporting and sponsoring the event in 1966. In 1967, O Estado de São Paulo wrote an editorial defending the fact that the Fair organizers benefited from public funding, as follows: “our Secretary of Education shouldn’t continue ignoring this state-wide movement that shows no signs of slowing its continued growth, despite the obstacles'' (ESTÍMULO…, 1967, p.12). According to registries, the São Paulo State Government is only cited as a sponsor in 1969, alongside the Roberto Simonsen Foundation, a branch of FIESP, and the São Paulo State Bank (BANESPA) (E, NESTA…, 1969, p.14). The following year, they were joined by the “Fundação Bienal” (Biannual Foundation) (FEIRA…, 1970d, p.15). In 1973, the “Fundação Padre Anchieta” (Father Anchieta Foundation) also began supporting the Fair (SÃO…, 1973, p.17). In 1974, the São Paulo mayoral office allocated an amount equal to 200 monthly salaries at minimum wage for the implementation of the event (PAULISTAS…, 1974, p.10). In 1976, the “Organização de Estados Ibero-Americanos” (Organization of Ibero-American States) (OEI) was listed as a supporter (FEIRA…, 1976, p.176).

Over the course of the Fair’s various editions, IBECC organized talks and set up stands selling textbooks and scientific demonstrations at the Fair. Some professors and teachers associated with the Institute are listed as creators of the demonstrations, such as Myriam Kasilchik, Rachel Gevertz, Fuad Karim Miguel and Odília Paloma Gomes (FEIRA…, 1960, p.6). Aside from these demonstrations, the IBECC educators showed scientific films and carried out blood drives for certain blood types.

All of the Fair’s editions had opening and closing ceremonies, some with musical performances. The presence of authority figures and individuals important to the history of science and Brazilian education at these ceremonies is repeatedly registered in the documents analyzed. One article from 1963, for example, notes the presence of “numerous authority figures associated with São Paulo’s educational sector”, such as the dean of the University of São Paulo (USP) (A IV…, 1963, p.7). Subtitled “prestige”, another article in 1967 noted the presence of the State Secretary of Education and representatives of the “Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo” (São Paulo Research Foundation) (FAPESP) and the CNPq (X FEIRA…, 1967, p.10). The musicologist Renato Almeida, president of IBECC and an important figure in the study of Brazilian folklore, was present at the same ceremony (VII FEIRA…, 1967, p.7).

The panels of judges of student work were also typically composed of USP professors and important figures in science and education. José Reis himself was on the 1960 and 1962 panels.

As well as a demonstration of prestige and possibly a strategy to popularize the Fairs, the presence and participation of science and education authorities made the event a space for the strengthening of ties between the social entities involved in the science education renewal movement. Given the quantity of articles in newspapers, practically all of which mention IBECC, the authors believe that it is possible to affirm that the Fair inserted itself into the process of legitimization of the Institute itself among educators and society as a whole. In an article on the third Fair in 1962, for example, the “success” of the event is described as representing how “IBECC has taken another step towards the consolidation of its goal of increasing the popularity of science education” (FEIRA… 1962, p.10).

2.2.1. Profile of student exhibitors

At first, the Fairs were destined towards students in the antiquated “ginasial” (junior high) and “colegial” (high school) grade levels. From 1962 onwards, the Fair also accepted elementary school projects (FEIRA…, 1962, p.10). As such, the profile of the students shifted: in the first editions, most of the students described were 15-17 year old males. In 1968, however, an article mentions that “the average age of the students is 14” (BOAS…, 1968, p.7).

In the first editions, public school students predominated the newspapers’ student descriptions. Over time, private schools began to be highlighted. The newspapers began emphasizing the names of the schools that students attended. The authors encountered some publicity pieces published in 1970 in São Paulo high schools announcing the names of prize-winning students and the implementation of internal science fairs as indicators of the high quality of education that they provided. This shift follows the broader increase in prevalence of private schools in Brazil during the 1970s.

Students from the capital and the state of São Paulo exhibited at the fair from its first edition onward. As science fairs expanded across the state, the Fair began to divide registries into two categories: students from the capital could register directly at the Fair, and students from around the state that had won their respective local fairs the previous year were automatically classified for the São Paulo city Fair. Reis elaborates in this 1970 article:

The science fair movement won over the entire state of São Paulo and also spread to other states and various countries around South America that were inspired by IBECC’s work. Little by little the Fair organized by this Institution came to be the crown jewel of the many fairs held around the state (REIS, 1970, p.1).

The inequality between students from the capital and the rest of the state is mentioned in some texts. Students not from the city of São Paulo are generally presented as “hard working” with more “simple” and “modest” projects. This disparity, however, did not impede prizes from being awarded to students from the countryside. Their presence at the fairs, even with their “diminutive resources and means for study and research”, was considered a demonstration of the “extraordinary spirit of sacrifice and abnegation that animates them” (ESTÍMULO…, 1967, p.12). A 1969 article narrates the conquest of first prize at the Fair by a team of students from Sorocaba (SP), denoting this polarization:

Appearing with their materials held under their arms, the Sorocaba students almost gave up on participating in the Fair when they saw the arrival of trucks or even tractor trailers bringing in modern and complex equipment for super-stands. Despite this, they set themselves up with their crickets, toads and spiders [...], which filled their stand with webbing and won them first prize (ARANHA…, 1969, p.26).

As time went on, the Fair also began accepting applications from students from other states, especially from Rio de Janeiro. The five editions from 1970 to 1974 even received students from Argentina, which had also been consolidating its own science fairs. In 1974, the attendance of Peruvian students was noted (COMEÇA…, 1974, p.14). The presence of these students from other states and countries was depicted by newspapers as a marker of development and prestige of the São Paulo Fair in relation to the rest of Brazil and Latin America, as well as evidence of the advancement of the science fair movement that had begun in São Paulo with the Fair. One 1969 article denoted that in its 9 years of existence, “the fair demonstrated such good results that, this time, professors from Argentina, Venezuela, and Bolívia have come to witness it for themselves in order to model their own efforts after it” (E, NESTA…, 1969, p.14). In 1971, it was written that:

Having begun just over ten years ago in Brazil, more precisely in São Paulo, the Science Fairs were slowly but surely gaining popularity, polarizing interests and crystalizing ideas until they encompassed the Brazilian education system as a whole. Today, fairs are held around the State of São Paulo and in many other Brazilian cities. For some time now, educational institutions in neighboring countries, under the direct influence of IBECC’s work, have joined the movement to renew scholastic methods and practices in the teaching of the sciences (GRANDE…, 1971, p.152).

As stated in the documents, the Fairs were attended by hundreds of exhibitors and thousands of visitors, which was presented as an indicator of the initiative’s success. The majority of visitors were young students. Other visitors are described as “the common man”, the “teachers”, and the “parents” of students. The enthusiastic and upbeat spirit of the students and the fair environment is markedly evident in these descriptions. According to the texts, each edition was carefully organized and well decorated with vibrant colors. Signs and placards advertising the projects on display were spread through the corridors. Moreover, the students, many of which wore lab coats or white aprons, distributed pamphlets inviting visitors to their stands.

2.2.2. Exhibited projects

Articles covering the Fair during the fair days themselves and those that announced the prize winners of each edition typically presented a few of the exhibits that had been prepared during the school year for the occasion. Some were described with the clear intention of promoting the event, piquing the reader’s interest in order to draw visitors to the Fair. Those that described the prize winning projects were presented with the intention of celebrating the potential of those young scientists.

Projects were explained in their minutiae, with journalists describing the research process, potential applications, modes of demonstrations, and expository materials: signs, panels, illustrations, and mockups. The majority of the projects presented at the Fairs were group projects. Individual projects, though a minority, were also highlighted in newspaper coverage. Among those highlighted were collections of minerals, animals, and plants, demonstrations of scientific principles and presentations of the history of scientific concepts and disciplines. Projects related to themes in the health sciences were frequently highlighted. One article in 1974 noted the existence of “a preventative and educational mentality in the areas of hygiene and health, showing films and graphics on diseases” at the fourteenth Fair (TERMINA…, 1974, p.22).

Another strain of projects focused on by newspapers over the years were those involving experiments with animals. Dissection and vivisection were frequent entries in these categories45.

The “apparatuses” that students constructed - batteries, miniature steam-powered machines, miniature electric automobiles, etc - also garnered the newspapers’ attention. Among these “apparatuses”, robots constructed by the students truly stood out. The 1973 Fair, for example, was to have a “full sized robot” (IBECC-UNESCO, 1973, p.16) as a “main attraction” (UM ROBÔ…, 1973, p.11). The words “advanced” and “automatic” were frequently used in the descriptions of these robots and apparatuses in a positive light.

Projects researching outer space at the end of the 1960s and inspired by the arrival of man on the moon in 1969 were also markedly present at Fair editions. Rockets and replicas of National Space Agency (NASA) projects were commonly seen during this period. At the 1968 Fair, a miniature of a “NASA project, from rocket launches to electromagnetic propulsion” was specifically mentioned (VEJA…, 1968, p.8). The 1970 Fair went further, with “a rocket, with a rat on board” that “was launched 300 meters, once every half hour [...] in Ibirapuera park” (FOGUETE…, 1970, p.14).

At the end of 1972, the Folha de São Paulo published that the winner of the previous year’s Science Fair, with a project on the “origin, form, measure, and weight of rain drops”, was invited by NASA to tour their facilities and watch the launch of the Apollo-17 rocket at the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, USA (NASA…, 1972, p.25). The trip, which included a visit to other scientific and technological institutions around the country as well as Disney theme parks, was paid for by the aeronautic technology company Fairchild Industries. Prior to the journey, the winning student was invited to a meeting with the governor of São Paulo, Laudo Natel (1920-2020) (LAUDO…, 1972, p.11), and, upon her return, attended an event with the Secretary of State of the United States, William Rogers (1913-2001), and the President of Brazil, Emílio Médici (1905-1985), to whom she delivered a “moon rock” brought back from the trip (MÉDICI…, 1973, p.3).

Projects most commonly fell under the categories of either physics or biology, though mathematics and chemistry were also prevalent. Projects in other scientific disciplines, such as astronomy, zoology, geology, etc appeared over time. The majority of projects in the 1960s tended to frame science in a positive light, demonstrating its potential. The risks of science appear more rarely, in the form of explosion risk. Innovation and the applicability of scientific experiments can be categorized as expectations for the students’ presented work.

The 1970s presented two subtle shifts in the profile of projects highlighted by the press. On one hand, it was emphasized that projects presented at fairs should be “streamlined for potential industrial applications” (IBECC-UNESCO…, 1972, p.16). For the then representative of FUNBEC, Jaime Nazário, “projects piquing the interest of the business community may be further developed, after the completion of a study on economic viability, and produced on an industrial scale” (NA FEIRA, 1973, p.41). On the other, the concept of “social utility” also appeared in the 1970s (NA FEIRA…, 1973, p.41).

Similarly, projects more connected to the context in which they took place, such as those with an environmental focus, began to appear in this decade. At the tenth Fair in 1970, a journalist’s attention was arrested by a project on air and water pollution. According to the student who was interviewed, the project demonstrated that “one of the consequences of the technological progress of modern society is environmental pollution. Our sky is no longer so blue and our water no longer so clear” (FEIRA…, 1970c, p.6). For another journalist, this stand was considered “one of the favorites” (FOGUETE…, 1970, p.14). At the following year’s Fair, the newspaper A Tribuna noted that “most of the projects [...] address the problem of air, water, soil, and noise pollution” (ADULTOS…, 1971, p.5). In 1972, at the twelfth Fair, one of the event’s objectives was the “presentation of projects related to various aspects of community life” (COMEÇA…, 1972, p.14). At the same edition, projects employing the terms “reforestation” and “environmental education” were seen for the first time, presented by students from a Rio de Janeiro science club, supported and sent to the Fair by Jornal do Brasil. The project was named the “Patrulha da Natureza” (Nature Patrol) and the students, after taking courses on the subject, planted approximately 7500 trees (ELES…, 1972, p.20). This project was one of the most visited and received honorable mention at the Fair (COLÉGIO…, 1972, p.16). At the 1973 Fair, a project with explanatory posters on the consequences of air pollution in São Paulo was highlighted (COMEÇA…, 1973, p.15).

This media coverage and the emphasis on projects related to the discussion of the environment and the impact of science reflect some of the changes in science education during this period. Beginning in the 1970s, new science curricula were designed, especially in countries such as England, The United States, Canada, The Netherlands, and Australia, contemplating the impacts of science and technology on daily life, work, and the environment (NORBERTO ROCHA, 2018). The same process can be observed in Brazil, as argued by Krasilchik (2000, p.89):

From 1960 to 1980, environmental crises, increases in pollution, the energy crisis, and the social efervescence manifested in movements such as the student revolt and the fights against racial segregation led to profound transformations in the types of proposals seen in scientific disciplines at all levels of study. The social implications of science were incorporated into these curriculum proposals at the junior high schools of the time and later in elementary schools.

It can also be observed how some articles drew attention to the capacity for “improvisation” and “creativity” in the use of “spare parts” and “old toys” that were “repurposed” for scientific experiments. One article on the 1972 Fair, for example, noted “improvisation and ingenuity in the use of simple materials from daily life in the construction [of an] apparatus” (COLÉGIO…, 1972, p.16). Two years prior, O Estado de São Paulo described the students’ improvisational capacity as an “effort of future scientists to continue despite adversity” (E, NESTA…, 1969, p.14).

2.2.3. The expansion of the fair to other subjects and the arts

The materials reviewed by the authors showed that the Fair was gradually opened to areas of study outside of the natural sciences, including to the arts. Works in the social sciences and humanities, particularly in psychology, can be identified from 1969 onward. In 1970, the tenth São Paulo Fair began accepting artistic projects “related to scientific themes”: “as such, children who have created paintings or sculptures related to science fiction or that depict some advancement in the sciences may register” (FEIRA…, 1970b, p.9). According to the Jornal do Brasil, “paintings alluding to man’s conquest of the moon” predominated (FOGUETE…, 1970, p.14).

In his Sunday column in the Folha de São Paulo, José Reis described the approximation of science and art promoted by the Science Fairs as an “important step” (REIS, 1970, p.1). In his article titled “A arte comparecerá à Feira de Ciências” (Art will appear at the Science Fair), Reis wrote that the common ground between these two areas could “humanize science”, and would also be capable of “reforming or expanding the resources available to the arts in their experience and utilization of science” (REIS, 1970, p.1)

From 1972 onwards, the Fair included musical performances such as choirs, bands, and marching bands (ARTE…, 1972, p.21). The Fair’s 1972 objectives include stimulating “the cooperation between experts in different areas, even those not generally considered ‘sciences’” (COMEÇA…, 1972, p.14).

In the following year, “a Brazilian art and folklore section” (COMEÇA…, 1973, p.15) and “a section for a children-only art contest” with “drawings, collages and paintings” (ESTUDANTES…, 1973, p.25) were included in the Fair. The event came to be called the “Grand São Paulo Science and Culture Fair”, with the addition of the words “grand” and “culture” to the previous name. The 1974 fair even included a “parade of fanfare”, composed of 38 different educational institutions (A FEIRA…, 1974, p.14). The 1976 Fair went so far as to include theatrical performances by students and conferences with titles such as “theater in school” and “why include theater at school?” (PRODUÇÃO…, 1976, p.12).

Maria Julieta Ormastroni described this widening of the Fair’s scope: “at first, the fairs were focused only on science. We thought: ‘Why not introduce theater, music…?’ So we began to organize musical performances and plays. The project expanded enormously”6.

2.2.4. Prizes

The first fairs (1960-1964) awarded prizes to students who presented the best projects with the science experiment “kits” that IBECC produced (cf. ABRANTES, 2008), as well as honorable mentions and the publication of the names of winners, sometimes accompanied by photographs, in newspapers. Teachers were also awarded 5 thousand cruzeiros (equivalent to about 900 reais or 180 dollars).

In 1966, the year in which the Folha de São Paulo began sponsoring the Fair, the “Folha de São Paulo Trophy” was instituted, consisting of “statuettes representing a boy and girl with arms raised holding an effigy of a Brazilian scientist” (TROFÉUS…, 1966, p.17)

Beginning in 1969, newspapers began to announce trips as prizes for the best projects, such as a trip to Caxias do Sul (RS) for participation in the local science fair (ARANHA…, 1969, p.26). In 1970, another trip was offered, this one to the North of the country, as well as medals and trophies (PRORROGADAS…, 1970, p.9).

Newspaper coverage revealed the presence of a competitive spirit during the transition from the 1960s to the 1970s. In 1967, one newspaper announced that the objective of the Fair was to awaken “the spirit of competition” between students. In the 1970 Fair, an article on the closing ceremony -where prizes were distributed- stated that it “showed aspects of a true dispute, with delegations from high schools waving banners and cheering passionately for their colleagues” (FEIRA…, 1970e, p.10).

The question of competitiveness in education has been debated in academic literature on education, particularly in terms of activities such as olympiads and science fairs. Rezende and Ostermann (2012), for example, indicate the necessity of questioning competitiveness as a fundamental value in science education (a historically exclusionary field of knowledge). For these authors, the presence of competition in teaching is based on the idea that the contributions of talented individuals should form the foundation of the construction of scientific knowledge. The concept that these talents can be revealed through scientific competitions resonates in the political developmentalism present in the Brazilian government since the 1960s. Disregarding the pre-existing inequalities and the impacts that failures in these activities can have on students, Rezende and Ostermann argue, scientific competitions can reinforce the role of school as a reproducer of social inequalities.

Rezende and Ostermann also indicate that the construction of a relationship between knowledge, language, science, and real, day-to-day situations is questionable for this type of activity.

Upon analyzing the history of science fairs in the United States, Terzian (2013) identifies the presence of meritocratic thought that strengthened during the post World War II period and during the Cold War era. The author suggests that this approach accentuated educational inequality and, as a whole, contributed to the general problem of underrepresentation of minorities and women in scientific fields.

Mancuso and Leite Filho (2006) apply such a lens to the specific case of Brazil, identifying competition-related conflicts during the history of the Fair that damaged its educational value, even causing some discomfort through the use of the name “science fair”, with proposals for substitution with terms such as “show” and even the opening of fairs to the arts.

An attempt to ameliorate the competitive nature of the São Paulo Fair can be found in press coverage during 1972, when the twelfth Fair announced the end of its prize system:

The Brazilian Institute of Education, Science, and Culture, the promoter of this contest, will no longer award prizes for best projects, as it has done in previous years, for, as professor Antônio Teixeira, one of the organizers, has stated, “the distribution of prizes has never sat well with all involved and does not advance the objectives of the Science Fair in any way” (SÃO…, 1972, p,10)

In the same year, the Fair announced that one of its objectives was the “development of the spirit of solidarity among students” (COMEÇA…, 1972, p.14). Instead of the old prize scheme, there would be only one prize: the projects that most stood out would be presented “during a program dedicated to Science Fairs”, on “Educational TV, Channel 2” (IBECC…, 1972, p.22)

In the following year, the 1973 Fair declared itself as having “the character of an exposition” and no longer that of a “competition” as it previously had (JOVENS…, 1973, p.16). However, some projects were still classified as the “best”. For these selected projects, “the prizes offered”, as the Folha de São Paulo announced, would be “books, exclusively, seeing as the event aims to, above all, awaken an interest in culture in general” (COMEÇA…, 1973, p.15).

Meanwhile, during the Fair, the awarding of “a trip to Belo Horizonte and Ouro Preto” as a prize to the six best projects was announced (ÚLTIMO…, 1973, p.18). In 1974, the organizers declared to the press that the Fair did not have:

Any prizes for the projects presented by students, however, [...] all will receive a certificate of participation and, among the six best teams, one will be randomly chosen to travel to Belo Horizonte, where the winners will participate in that city’s science fair as well (COMEÇA…, 1974, p.14).

Despite the reduction in prizes and such announcements from the organizers declaring that the fair would no longer be a competition, newspapers never stopped emphasizing the words “prizes”, “competition”, and “best” in their coverage.

2.3. The Science Fair between school and society: experimental teaching, the training of scientists, and science communication.

The Brazilian science education renewal movement was the subject of debates on the model and objectives of schools, as well as the role of science in Brazilian society (CASSAB, 2015). Demands for the expansion of schools and the relative weight of science in curricula, as well as better training for teachers and the replacement of older, expository methods of teaching with those in which the students would have the experience of “learning by doing”, in such a way as to form a population trained as scientists, were a constant presence in proposals for an educational system in which science had a more central role in national development efforts. Initiatives in the areas of science communication and the construction and modeling of science’s role in society were gaining strength when IBECC was created at the end of the 1940s (ABRANTES, 2008). As Cassab (2015) observes, rhetoric in proposals for the reformation of Brazilian science education frequently cited the association between deficits in science education and unsatisfactory technological development. This association served to legitimize such programs, allowing for the implementation of systematic investment in science education and the expansion of the domestic scientific community. These goals formed the foundation of IBECC’s mission in the sciences in general and in science education (ABRANTES, 2008; CASSAB, 2015, p.27). Press coverage of the São Paulo Science Fair demonstrates the specific ways in which these same associations appeared in the 1960s and 1970s.

The São Paulo Fair was presented by newspapers as an example of the application of new methods in experimental education derived from the science education renewal movement spearheaded by IBECC. In one article on the third Fair in 1962, the newspaper Correio Paulistano published the Institute’s argument that “science education in our schools sins in its bookish, boring, and unpleasant nature, demanding that our students memorize abstract texts” (CIENTISTAS…, 1962, p.4). As such, the Institute set out to organize science fairs as part of the fight for the “transformation” and “dynamization of science education” (CIENTISTAS…, 1962, p.4). The Folha de São Paulo’s support for experimental teaching methods can be seen in an article it published on IBECC and the 1969 Fair, stating that “studying science by practicing it, through personal experience, is the only way to learn” (IBECC…, 1969, p.40). The objectives of the Fair that the paper most often cites are those of “awakening the scientific spirit and the interest in scientific vocations” in students. Some articles focused on the capacity that students demonstrated to plan and produce apparatuses and other experiments with only their teachers for support, as well as to create clear presentations of their projects and show their mastery of scientific concepts and methods. The newspapers attributed this capacity to the practical and experimental teachings methods that the Science Fair represented, as can be seen when the Estado de São Paulo writes that the Fair represented the “reform effort in scholastic methods and practices in science education” (GRANDE…, 1971, p.152) promoted by IBECC. It can be stated, therefore, that the newspapers analyzed in this work considered science fairs to be strategically effective in transforming science education in the country.

The potential to attract young people to scientific careers was also a present and important objective stated in the articles analyzed, especially in editorials and interviews with organizers. Soon after the first Fair, O Estado de São Paulo published an editorial on the initiative in which it was stated that the projects presented at the fair signified “the future beckoning”, “the image of a modern Brazil and, above all, the Brazil of the future” (NOTAS…, 1960, p.3). This same optimism regarding long term results of science fairs can be seen in other articles, such as this editorial from the Correio Paulistano commemorating the success of the first Fair:

Without scientists and future scientists, aspirations of economic development in Brazil would be fantasy, remote illusion, unrealizable. Science, cultivated by teams that earn renown and grow [...], is the only real and effective guarantee for the strengthening of our civilization. [...] For these reasons, the first Science Fair, of these young students, is something that deserves support and incentive [...]. They are the future “scientists of tomorrow” that Brazil so dearly needs (NOS…, 1960, p.6).

Seven years later, that same optimism persisted in the following editorial from the Estado de São Paulo written shortly after the seventh Fair in 1967, in which experimental education and the preparation of new scientists appear linked:

[the science fairs] are eloquent manifestations of the fact that the youth of Brazil wishes to learn by participating in the experimental school, the practices and assays of the laboratory [...]. No doubt remains that, if they continue to be assisted and stimulated as they have been, the youth of today will be able to take part in the near future in a fruitful flowering of science among us (ESTÍMULO…, 1967, p.12).

In 1970, in a column on the tenth Fair, the Folha stated “This is where the great scientists that will make Brazil proud in the future are coming from” (FEIRA…, 1970a, p.12).

The students were constantly described as “young scientists”, “mini-scientists”, “little scientists”, and “scientists of the future”. Expressions such as “mini-geniuses” or just “scientists” can also be found. Some texts focus on the “genius” of the best students, as is the case in a 1969 article that reads: “the Fair’s promoters are always looking for new geniuses and can proudly say that they have found a few, as indeed many good people have been discovered at the Fair.” (E, NESTA…, 1969, p.14). Some descriptions of interviewed students include their desired future professions. Most mentioned areas in engineering or medicine. These references had the clear intention of supporting the argument that these students felt a vocational call to science and that they intended to dedicate their careers to the sciences.

The presentation of the Fair as a medium for science communication was the third aspect revealed by the authors’ analysis. Presenting students were incentivized to demonstrate their methods, executions, principles, and scientific research objectives to the visiting public as a way of informing society on the scientific universe. As can be observed in one article, one of the objectives of the Fair from 1970 onward was to “awaken an interest in science in the common man” (COMO…, 1970, p.2). In 1971, the statement that “adults can learn from young presenters at the eleventh Science Fair” was published (ADULTOS…, 1971, p.5). In 1972, O Estado de São Paulo published an article on the twelfth Fair titled “Ciência vai às ruas para educar o povo” (Science hits the streets to educate the public) (CIÊNCIA…, 1972, p.12).

According to press coverage, the predominant model of the fair appears to be the deficit model, common in science communication, that separates producers and consumers of knowledge and presents science communication activities in a linear and unidirectional manner, with information flowing from gifted individuals that hold scientific knowledge to an amorphous mass of the uninformed, with the objective of creating a better educated population (BROSSARD; LEWENSTEIN, 2010). This is evident in the articles that report on the students “on exhibition for”, “presenting to”, and “informing” the “public”. Their capacity to explain the “complex scientific principles” with the use of “scientific language” is a present theme (BOAS…, 1968, p.7). In 1962, a journalist was surprised by students that “made a point of stopping visitors in order to explain their apparatuses which, according to them, were ‘complicated for lay-people’” (FEIRA…, 1962, p.9).

Visitors were presented as people who “should attend” science fairs in order to “learn from the students”, expanding their scientific knowledge, as well as being “surprised” by the students’ intellectual and expository capacities. Their most protagonistic action was that of “asking questions”, though this was not commonly cited. Captions of two photographs from a 1972 article illustrate their position: the visitors “listen attentively to the students’ intricate explanations. They all ask questions, observe, and examine the details of the project” (ELES…, 1972, p.20). The two photographs depict the same scene: adult men observing stands while a young student gestures.

Final Considerations

This analysis of journalistic material allowed for the systematization of some of the data that reconstitute a part of the history of the São Paulo Science Fair and its most important related individuals and organizations. It was possible to discern that, between 1960 and 1976, 16 editions of the Fair were organized, in four distinct locations, with varied support and sponsorship and distinct prizes. Fronted by Maria Julieta Ormastroni and Isaías Raw, with active support from José Reis, the São Paulo Science Fair constituted an important event in the demonstration of scientific projects executed by students from the city of São Paulo and from around the state during the school year. The authors observed the special attention paid by newspapers to the projects involving animals, “apparatuses”, robots, and rockets, as well as an expectation for the projects to be technologically applicable. Some changes in the standards for presented projects, such as the inclusion of artistic work and projects concerning local contexts, as in the case of projects with an environmental theme, were also observed.

The São Paulo Science Fair was well-covered by important newspapers of the period and was described by them as being the most developed fair, having the most participants and the largest visiting public, and being the best organized fair in the country, serving as a benchmark for the organization of other fairs domestically and even internationally. For this reason, the Fair can be considered the most important fair of the period and the outwardly radiating center of the science fair movement that developed in the 1960s and 1970s due to its size and popularity.

The high expectations around science fairs as part of the science education renewal movement, the focus of IBECC’s initiatives, is an important aspect of discussion. Newspapers presented some of the positive results of the Fairs, such as students’ academic development, shown through their demonstrated creative and expository capacities and dextrous handling of scientific concepts and methods, in order to defend the efficacy of such events.

Contemporary authors dispute the degree to which various persistent investments that began in the 1950s resulted in a de facto improvement in science education, both in Brazil and internationally. Rezende and Ostermann (2012), for example, indicate that science education remains inadequate in terms of society’s needs, students’ interests, and epistemological considerations. However, numerous other authors defend the importance of the organization of science fairs as motivational events for students and teachers, as well as for their role in promoting scientific literacy and education and the integration of schools with their communities (MANCUSO; LEITE FILHO, 2006).

The authors’ analysis of the collected bibliography additionally allowed for the observation of how the newspapers defended the grounding thesis of science fairs as an important strategy for the engagement of young people in scientific careers. Abrantes (2008) argues that IBECC’s programs, advanced by scientists and educators interested in educational reform and the legitimization of science, formulated a viable path for the insertion of science into the national development project. In this sense, the presence of the fair in press coverage can be viewed as a reinforcement of this insertion, grounded in the strengthening of the nation’s scientific and technological capital.

Acknowledgements

The first author thanks FAPERJ for the TCT scholarship. The second author thanks FAPERJ for the “Cientista do Nosso Estado” (Our State Scientist) scholarship, as well as the CNPq for the 1B productivity scholarship. The third author thanks FAPERJ for the “Jovem Cientista do Nosso Estado” (Young Scientist of Our State) scholarship.

REFERENCES

VII FEIRA de Ciências mostra 1200 trabalhos. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 20 mai. 1967, p.7. [ Links ]

X FEIRA de Ciências será aberta hoje. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 19 mai. 1967, p.10. [ Links ]

A IV Feira de Ciências termina hoje com prêmios. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 22 set. 1963, assuntos diversos II, p.7. [ Links ]

A FEIRA de Ciências, dia 25 no Ibirapuera. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 21 mai. 1974, Educação, p.14. [ Links ]

ABRANTES, Antonio Carlos Souza de. Ciência, Educação e Sociedade: o caso do Instituto Brasileiro de Educação, Ciência e Cultura (IBECC) e da Fundação Brasileira de Ensino de Ciências (FUNBEC). Tese (Doutorado em História das Ciências e da Saúde) - Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. Rio de Janeiro, 2008. Disponível em: https://www.arca.fiocruz.br/bitstream/icict/15976/2/63.pdf. Acesso em: 23 mar. 2020. [ Links ]

ABRANTES, Antonio Carlos Souza de; AZEVEDO, Nara. O Instituto Brasileiro de Educação, Ciência e Cultura e a Institucionalização da Ciência no Brasil, 1946-1966. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi - Ciências Humanas, vol. 5, n.2, p.469-489, maio-ago. 2010. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1981-81222010000200016 [ Links ]

ADULTOS podem aprender com jovens expositores da XI Feira de Ciências. A Tribuna, São Paulo, 29 mai. 1971, p.5. [ Links ]

ARANHA alucinada dá o prêmio a Sorocaba. O Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 26 jun. 1969, p.26. [ Links ]

ARTE e música vão à Feira de Ciências. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 14 mai. 1972, terceiro caderno, p.21. [ Links ]

BOAS experiências e muito esforço dos jovens estão na VIII Feira de Ciências. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 26 mai. 1968, p.7. [ Links ]

BORGES, Regina Maria Rabello; IMHOFF, Ana Lúcia; BARCELLOS, Guy Barros (Org.). Educação e cultura científica e tecnológica: centros e museus de ciências no Brasil. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2012. Disponível em: https://editora.pucrs.br//Ebooks/Pdf/978-85-397-0761-4.pdf. Acesso em: 18 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

BROSSARD, Dominique; LEWENSTEIN, Bruce V. A Critical Appraisal of Models of Public Understanding of Science: using practice to inform theory. In: KAHLOR, Lee Ann; STOUT, Patricia (Eds.) Communicating Science: new agendas in communication. New York: Routledge, 2010. p.11-39. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203867631. [ Links ]

CASSAB, Mariana O Movimento Renovador do Ensino das Ciências: entre renovar a escola secundária e assegurar o prestígio social da ciência. Revista Tempos e Espaços em Educação, v. 8, n.16, p.19-35, mai./ago. 2015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20952/revtee.v0i0.3938. [ Links ]

CIÊNCIA vai às ruas para educar o povo. O Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 27 mai. 1972, p.12. [ Links ]

CIENTISTAS de amanhã inauguram Feira hoje. Correio Paulistano, São Paulo, 21 set. 1962, p.4. [ Links ]

COLÉGIO Afonso Celso ganha menção especial na Feira de Ciências de São Paulo. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 30 mai. 1972, p.16. [ Links ]

COMEÇA amanhã a XIII Feira de Ciências. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 24 mai. 1973, 2º Caderno, Educação, p.15. [ Links ]

COMEÇA amanhã no Ibirapuera a XII Feira de Ciências de São Paulo. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 25 mai. 1972, Educação, p.14. [ Links ]

COMEÇA na sexta a Feira de Ciências. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 21 mai. 1974, educação, p.14. [ Links ]

COMO anda o turismo. O Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 08 mai. 1970, suplemento Turismo, p.2. [ Links ]

DE 20 a 30 do corrente a 1ª Feira de Ciências. O Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 7 abr. 1960, p.13. [ Links ]

E, NESTA feira, o cabelo fica em pé. O Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 20 jun. 1969, p.14. [ Links ]

ELES estão com a ciência na mão. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 28 mai. 1972, 2º Caderno, Educação, p.20. [ Links ]

ESTÍMULO aos jovens. O Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 26 mai. 1967, p.12. [ Links ]

ESTUDANTES e ciência, 3 dias no Ibirapuera. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 25 mai. 1973, Educação, p. 25. [ Links ]

FEIRA de ciências. O Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 12 set. 1976, p.176. [ Links ]

FEIRA de Ciências começa amanhã com 800 peças. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 28 mai. 1970a, p.12. [ Links ]

FEIRA de Ciências: gente miúda trabalhou como gente grande. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 10 out. 1962, Folha Ilustrada, p.10. [ Links ]

FEIRA de Ciências: inscrições. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 22 abr. 1970b, p.9. [ Links ]

FEIRA de Ciências: os jovens expõem o trabalho do futuro. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 30 mai. 1970c, p.6. [ Links ]

FEIRA de Ciências premiou os mestres e os alunos. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 24 set. 1962, 1º caderno, p.9. [ Links ]

FEIRA de ciências que abre dia 29 no Ibirapuera já tem 50 colégios inscritos. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 13 mai. 1970d, p.15. [ Links ]

FEIRA de Ciências terminou em meio a torcidas e faixas dos estudantes em S. Paulo. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 02 jun. 1970e, p.10. [ Links ]

FEIRA do IBECC: admirável mundo novo para a vocação dos cientistas-mirins. Diário da Noite, São Paulo, 25 abr. 1960, p.6. [ Links ]

FOGUETE com rato a bordo é lançado a 300m pela Feira de Ciências do Ibirapuera. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 03 mai. 1970, p.14. [ Links ]

GRANDE feira de ciências. O Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 23 mai. 1971, p.152. [ Links ]

IBECC - aqui se formam os cientistas de amanhã. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 22 jun. 1969, caderno especial, p.40. [ Links ]

IBECC participa da reunião de ciência. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 21 mai. 1972, segundo caderno, p.22. [ Links ]

IBECC-UNESCO. O Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 25 mai. 1973, p. 16. [ Links ]

JOVEM verá Apolo-17 subir. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 15 nov. 1972, Local, p.10. [ Links ]

JOVENS estão expondo na Feira de Ciências. O Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 20 mai. 1967, p.12. [ Links ]

JOVENS vão demonstrar seu interesse pela Ciência. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 08 abr. 1973, 2º caderno, Educação, p.16. [ Links ]

KRASILCHIK, Myriam. Inovação no ensino de ciências. In: GARCIA, W.E. (coord.) Inovação educacional no Brasil: problemas e perspectivas. 3a ed. São Paulo: Cortez e Autores Associados, 1995, p. 177-94. [ Links ]

KRASILCHIK, Myriam. Reformas e Realidade: o caso do ensino das ciências. São Paulo em Perspectiva, v.14, n.1, p.85-96, 2000. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-88392000000100010. [ Links ]

LAUDO recebe aluna que verá vôo à Lua. Correio da Manhã, Rio de Janeiro, 29 nov. 1972, p.11. [ Links ]

MAGALHÃES, Danilo; MASSARANI, Luisa; NORBERTO ROCHA, Jessica. A mídia e a experimentação com animais no ensino básico de ciências no Estado de São Paulo: uma análise da cobertura feita por jornais impressos nas décadas de 1960 e 1970. Educação em Foco, v.24, n.43, 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24934/eef.v24i43.5636 [ Links ]

MANCUSO, Ronaldo; LEITE FILHO, Ivo. Feiras de Ciências no Brasil: uma trajetória de quatro décadas. In: BRASIL. Ministério da Educação/ Secretaria de Educação Básica. Programa Nacional de Apoio às Feiras de Ciências da Educação Básica. 84p. Brasília, 2006. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/seb/arquivos/pdf/EnsMed/fenaceb.pdf. Acesso em: 04 nov. 2019. [ Links ]

MASSARANI, Luisa; BURLAMAQUI, Mariana Mello; PASSOS, Juliana. José Reis: caixeiro-viajante da ciência. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz/COC, 2018. Disponível em: http://josereis.coc.fiocruz.br/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/miolo_jose_reis_caixeiro_ciencia_web.pdf. Acesso em: 02 jul. 2020 [ Links ]

MÉDICI e Rogers tratam só de assuntos gerais. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 24 mai. 1973, p.3. [ Links ]

NA FEIRA, estudante mostra seu talento. O Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 27 mai. 1973, p.41. [ Links ]

NASA escolhe colegial de SP. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 19 nov. 1972, 2º Caderno, Educação, p.25. [ Links ]

NORBERTO ROCHA, Jessica. Museus e Centros de Ciências Itinerantes: análise das exposições na perspectiva da Alfabetização Científica. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Programa de Pós Graduação em Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2018. DOI: 10.11606/T.48.2018.tde-03122018-122740 [ Links ]

NOS “Cientistas de Amanhã” o Futuro do País. Correio Paulistano, São Paulo, 24 abr. 1960, p.6. [ Links ]

NOTAS e informações. O Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 23 abr. 1960, p.3. [ Links ]

PAULISTAS farão feira de Ciência. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 12 nov. 1974, p.10. [ Links ]

PRÊMIOS da VI Feira de Ciências serão distribuídos hoje. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 15 mai. 1966, p.19. [ Links ]

PRODUÇÃO científica do escolar à mostra. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 11 set. 1976, educação, p.12. [ Links ]

PRORROGADAS inscrições da Grande Feira. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 6 mai. 1970, p.9. [ Links ]

REIS, José. A arte comparecerá à Feira de Ciências. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 03 mai. 1970, Folha Ilustrada, p.1. [ Links ]

REIS, José. A Feira de Ciências de Pindamonhangaba inspirou muitas reflexões. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo 30 out. 1966, Folha Ilustrada, No Mundo da Ciência, p.1. [ Links ]

REIS, José. Ciência extra-curricular. Revista Espiral, Ano 3, n. 10, jan. /mar. 2002. [ Links ]

REIS, José. Feira de Ciências no Espírito Santo. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 6 dez. 1970, Folha Ilustrada, No Mundo da Ciência, p.1. [ Links ]

REIS, José. Feiras de Ciência: uma revolução pedagógica [1965]. In: MASSARANI, Luisa; DIAS, Eliane Monteiro de Santana. (orgs.). José Reis: reflexões sobre a divulgação científica. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz/COC, 2018. Disponível em: http://portal.sbpcnet.org.br/livro/ebook_reflexoes_divulgacao_cientifica_press.pdf. Acesso em: 02 jul. 2020 [ Links ]

REIS, José; GONÇALVES, Nair Lemos. Veículos de divulgação científica. In: KREINZ, Glória; PAVAN, Crodowaldo; MARCONDES FILHO, Ciro. Feiras de Reis: cem anos de divulgação científica no Brasil: homenagem a José Reis. São Paulo: NJR-ECA/USP, 2007. [ Links ]

REZENDE, Flávia; OSTERMANN, Fernanda. Olimpíadas de Ciências: uma prática em questão. Ciência & Educação, v.18, n.1, p.245-256, 2012. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-73132012000100015. [ Links ]

SÃO Paulo abre Feira de Ciência. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 22 mai. 1973, p.17. [ Links ]

SÃO Paulo inaugura hoje no Pavilhão da Bienal a XIV Feira de Ciências. Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 26 mai. 1972, p.10. [ Links ]

TERMINA hoje a feira de ciência no Ibirapuera. O Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 26 mai. 1974, p.22. [ Links ]

TERZIAN, Sevan G. Science Education and Citizenship: Fairs, Clubs, and Talent Searches for American Youth, 1918-1958. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137031877. [ Links ]

TROFÉUS da FOLHA para trabalhos premiados em Feiras de Ciências. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 3 abr. 1966, p.17. [ Links ]

ÚLTIMO dia da Feira de Ciências. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 27 mai. 1973, 2º caderno, Educação, p.18. [ Links ]

UM ROBÔ, a grande atração da Feira. Folha de São Paulo, São Paulo, 26 mai. 1973, 2º Caderno, Educação, p.11. [ Links ]

VALLA, Daniela Fabrini; ROQUETTE, Diego Amoroso Gonzalez; GOMES, Maria Margarida; FERREIRA, Marcia Serra. Disciplina escolar Ciências: inovações curriculares nos anos de 1950-1970. Ciência & Educação (Bauru), vol.20, n.2, pp.377-391, 2014. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-73132014000200008. [ Links ]

2For more information about José Reis, see the work "José Reis: caixeiro-viajante da ciência" (MASSARANI et al, 2018) and the Acervo José Reis website, under the care of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation; Available at: http://josereis.coc.fiocruz.br. Accessed on: 26 August 2020.

4The “Campanha de Aperfeiçoamento e Difusão do Ensino Secundário” (Campaign for the Improvement and Dissemination of Secondary Education (CADES) was a program created bybe the Ministry of Education and Culture (MEC) on November 17th, 1953, during Getúlio Vargas’ second term, via Decree n˚ 34,638, which was in effect until 1971. The improvement of teacher quality, the creation of textbooks and educational materials, and the support of other activities involved in the improvement of secondary education in the country were some of the Campaign’s objectives. Available at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/1950-1969/D34638impressao.htm. Accessed on August 22nd, 2020.

Received: June 09, 2022; Accepted: August 21, 2022

texto en

texto en