the community of philosophical inquiry

“When they truly collaborate, it is a matter of we…”

Ann Sharp, “What is the Community of Inquiry?”

introduction

On the face of it, it might seem unproblematic to say that a community, whether of “philosophical inquiry” or otherwise, is composed of persons. From this we may conclude that a community is no more than a gathering of persons and rest content with this idea. Such a notion of community may be unproblematic, indeed, but it would have been far from satisfactory for Ann Sharp, the founder, alongside Matthew Lipman, of P4C. Of the two, it was Ann Sharp who probed into the interrelation of community and personhood during the years of developing CPI as a pedagogical and philosophical model of collaborative inquiry, while Lipman was arguably more focused on the “inquiry” side of the coin (Cam, 2018, p. 31). Studying Sharp’s writings, which are spread out over a vast output of scholarly articles, journalistic essays, conference presentations, letters, and interviews, is thus of major significance for understanding the deep philosophical foundations of the conceptions of personhood and community that animate the practice of CPI.

Sharp insisted time and again, and in so many ways, that the community of philosophical inquiry is essentially a community of “persons-in-relation” (Sharp, 1987, p.16). She was concerned with the sense of connection that bonded a collection of individuals into a true community. This idea of community as a “greater self”, as David Kennedy put it (Kennedy, 1994, p.13), has been an abiding theme in the literature ever since CPI was developed as the model of inquiry best suited for the practice of philosophy for children by Sharp and Lipman in the 1960s (cf. Gregory & Laverty, 2018a; Kennedy, 2010).1

Such views on the nature of personhood flow logically, imaginatively, and ethically from the process of philosophical inquiry itself. In the community of philosophical inquiry, the habitual answer expressed above - that a community is some sort of collection of discrete persons - will be found lacking. The process of inquiry will keep instructing us to attend to the ways in which one of the terms - either “person” or “community” - falls short of our initial definitions, our practical use of the terms, and our aspirations as participants in the inquiry. In the collaborative process of inquiry, the interdependence of the two terms (community and person) will come under as much scrutiny as the distinction that sets them apart. As a result, we will keep desiring to go beyond the strict separation of the two. We will come to see that while we cannot meaningfully understand community without the assurance that it is made up of physiologically embodied, reasonably self-aware persons, we cannot seem to adequately comprehend it as nothing more than such a collection of individuals. Simply put, the whole that we call “community” will seem to us, for many reasons, to exceed the aggregate of its parts (individual “persons”, including myself and others).

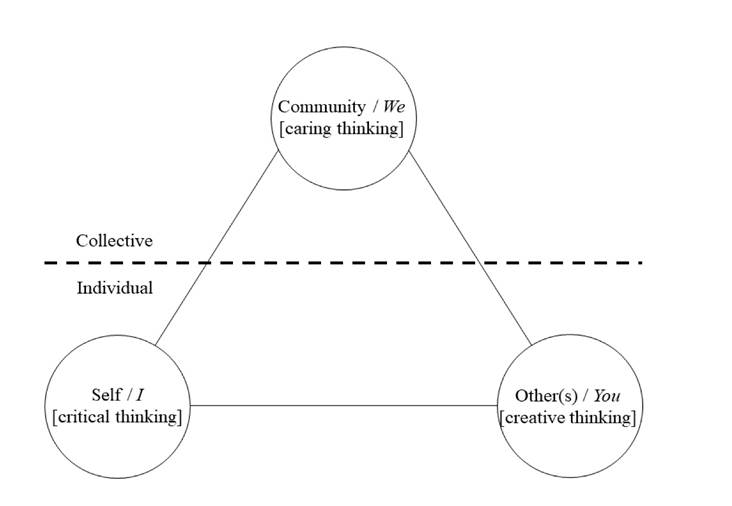

How are personhood and community exactly related, then? This question is not new. It was arguably one of the factors that led Lipman to revise his initial schema of P4C as centering around “critical thinking” and “creative thinking” to include a third kind of thinking which, following Sharp’s lead, was labeled “caring thinking”.2 And it is through the prism of caring thinking that Sharp’s pioneering contribution to conceptualizing the relationship between personhood and community comes to its own. Accordingly, the first half of the paper will outline the relationship that Sharp and Lipman had theorized between critical, creative, and caring thinking, focusing particularly on how these processes map onto the relationship between self, other, and community. After all, it is caring thinking, viewed as the culmination of critical analysis and imaginative reasoning, that ultimately discloses Sharp’s conception of personhood as a trilateral relationship. The second half of the paper will address a possible shortfall in Sharp’s conception of personhood, particularly with regard to her views on the relation of community to faith, the latter being expressive of the spiritual connection unifying the three terms of personhood. The paper will conclude by suggesting a possible path that may better illuminate the meaning of that spiritual connection, leaving the question open, though one hopes in a sharper light, for further inquiry.

community and personhood: preliminary conceptions

Self-knowledge, the Socratic aim of the philosopher, is not simply an inward-gazing procedure. “Only in community,” claims Sharp, “does one come to know oneself” (Sharp, 2018 [1996a], p. 53). What makes community such a privileged site of self-knowledge? According to Sharp, a community is composed, among other things, of habits. Each person involved in a community introduces their own idiosyncratic habits into the mix, even as they are conditioned by the habits at work in the community at large. Taking her cue from John Dewey, Sharp likens this dynamic to an encounter between two “selves”: “the innovative self,” the habits of thought and action which each person brings to the community out of the vicissitudes of their intimate life, and “the habitual self” or that aspect of my character which has formed without my knowledge, that is, through social conditioning (Cam, 2018, p. 31). Here we have the first sign of a genuine encounter, albeit of a seemingly hostile sort, between the individual and the community, where the latter appears as an external agency, operating over and above the life of the individual.

Similarly, the community of philosophical inquiry (CPI) may be said to consist of habits of philosophical inquiry. These habits are designed to facilitate a “ritual” (Sharp, 2009b, p. 302; cf. Sharp, 1997, p. 67) of self-knowledge by spurring “the innovative self” to ask fundamental, critical questions of “the habitual self” to which one is conditioned to assimilate in everyday life (Sharp, 2018 [1996a], p. 54). In other words, CPI is meant to saturate the innovative self with the habits of philosophical inquiry so that one can encounter the habits promoted by society at large with the tools of critical, creative, and caring thinking (more on these shortly). The encounter between these two aspects of the self (the innovative and the habitual) is one of the most transformative experiences that CPI can facilitate, as it discloses the deep involvement of the dictates of social conditioning in the intimate life of the individual, while at the same time providing the individual with the necessary means to exert their agency in the opposite direction.

How and when does this encounter take place? Sharp describes the encounter as a moment of self-realization brought about by the experience of error and the process of self-correction:

Unlikely as it may at first seem, the moments when we realize our own selves most intimately are not times when we are feeling good about who we are; rather, they are times when we have made errors, become conscious of the person who made these errors, and begun the process of self-correction. It is primarily through the act of self-correction that we come to know the self. (Sharp, 2018 [1996a], p. 51)

In such occasions as those described by Sharp here, the habitual self becomes present to me, I can relate to it (cf. Bieri, 2011; Tallis, 1999, p. 247) an “I” emerges that is not the habitual I, but speaks to it from “a place apart”, as David Kennedy put it, asking it questions, demanding that it account for its actions, undermining its unquestioned authority, and inviting it, in short, “to experience [a] crisis of meaning” (Kennedy, 1994, p. 18). Particularly because CPI secures a communal space that facilitates the articulation of concepts and fosters dialogical modes of thought, the “place apart” in which self-knowledge develops reveals itself to be a place both “within” and “without”, that is, not simply within me but somehow “inside” the community. The “intimacy” Sharp ascribes to the shared activity of self-correction and self-knowledge derives ultimately from “knowing and feeling oneself […] not as an atomistic ego but as a self in relationship to the other” (Sharp, 2009a, p. 414). But such “relational consciousness” (Sharp, 2009a.) is not forthcoming on its own. It is an accomplishment, the success of which depends on the dynamic exercise of critical analysis, “imaginative reasoning” (Sharp, 1997, p. 73), and “moral imagination” (Sharp, 2018 [2004], p. 233).

from critical to creative to caring thinking

When I engage in critical inquiry with the habitual self (mine or others’), I am trying to reason with that self and, in so doing, to win it over:

When the self thinks, there are always two selves thinking: the habitual self and the innovative self. When the self thinks, it is the habitual self that the innovative self tries to persuade. (Sharp, 2018 [1996a], p. 54)

Naturally, the appeal goes both ways, and the habitual self tries to draw the innovative self back into its orbit. In this sense, Sharp finds that “it is in the mystery and perplexity aroused by the analysis of concepts,” namely the concepts handed down to us by our upbringing and social conditioning, “that we begin to see the emergence of personhood” (Sharp, 1992, p. 58). What Sharp refers to as “the analysis of concepts” encompasses what is generally meant in P4C by “critical thinking”. It includes the familiar operations of detecting formal and informal logical fallacies. The upshot of Sharp’s statement is that genuine individuation becomes possible only when one becomes capable of interrogating the received wisdom with the aid of conceptual analysis. Conceptual analysis is thus depicted as a sort of minimum enabling condition for genuinely individuating as a person.

If the conditions of “critical thinking” are fulfilled, the process will deliver us to the moment of self-correction. The demands of the latter moment, however, cannot be fulfilled by the procedures of critical analysis alone, for in these logical procedures I take myself out of the equation, so to speak: I am generically “conscious” of the object under analysis, without necessarily being simultaneously conscious of myself. However, “the mystery and perplexity aroused by the analysis of concepts” will sooner or later drive the inquirer to re-construct their account of their own intimate experience and, to a greater or lesser degree down the line, to reconstruct their self-conception as a whole, such reconstruction being the only recourse left to avoid the collapse of one’s self-image under the weight of contradictions. This is why self-correction demands the contribution of imagination in tandem with conceptual analysis, since in reconstructing my self-image, I am no longer analyzing or breaking-up a given account of experience but attempting to smoothly integrate a number of conflicting accounts. Quite literally, in such situations, one has to imagine oneself otherwise, while preserving the results of the critical analysis that brought one to this point of the inquiry. Imagination in this context, therefore, is really a process of “imaginative reasoning” (Sharp, 1997, p. 73). In this process, I also gain insight into the extent to which my self-conception is the imaginary fabrication of social habits and institutions, that is, of the habitual self. Viewed in this light, imagination is that “crucial step in the growth of philosophical reasoning in the community,” which allows the inquirers “to become conscious of themselves in relation to the other people in their world, and to the ideas and culture of which they are part” (Sharp, 1987, p. 17). Lipman called this aspect of philosophical inquiry “creative thinking”. In creative thinking, the “discovery” of logical inconsistencies (“critical thinking”) calls for the “invention” of alternative, more reasonable accounts of experience, which in turn form the basis of a different, more reasonable and meaningful self-conception (cf. Sharp, 1987, p. 15; 2018 [2004], p. 237; Lipman, 2003, p. 249).

Such “aesthetic” (in the broad sense of creative or artistic) engagements with the self are part and parcel of the process of collaborative philosophical inquiry (Sharp, 1997; Kennedy, 2018). However, as was the case with critical thinking, creative thinking is not self-fulfilling. Like critical thinking, creative thinking must find its satisfaction outside of itself. In order for the self-transformation instigated by “creative thinking” to be fulfilled, Sharp argued for the cultivation of “caring thinking” side by side with critical analysis and imaginative reasoning. What caring thinking adds and imaginative reasoning on its own cannot provide is “intelligent sympathy”, another term borrowed from Dewey (Sharp, 1995, 1997, p. 72). While in “imagining” I see myself and reconstruct my experience in relation to what I know of others and their accounts of experience, in “intelligently sympathizing” I recognize myself not only in relation to another, but from the standpoint of another, that is, as someone other than who I imagine myself to be. Sharp also calls this capacity “empathic imagination” or “moral imagination” to distinguish it from imaginative reasoning (cf. Sharp, 2018 [2004], p. 233). According to Sharp, intelligent sympathy is realized at the moment when critical, creative, and caring thinking fuse together to bring about a transition from “self-consciousness” into “personhood” proper (cf. Sharp, 1992, p. 58). With caring thinking, I become something more than a self-conscious individual: I become a person proper, ethically and existentially bound not only to myself and others, but to the community at large.

Caring thinking thus fosters the creation of genuinely “relational consciousness”, that is, “knowing and feeling oneself intimately connected with and part of everything that is, and coming to act and relate out of that awareness” (Sharp, 2009a, p. 414). In caring thinking, I experience myself “not as an atomistic ego but as a self in relationship to the other” (Sharp, 2009a). My “self”, in other words, is invited to adapt to expanding and including the other(s) in my community not only as separate individuals encountering me each on their own, but as a collective: this collective other, so to speak, is invited to occupy a place at the core of my self-conception. But just as “imagination” and “sympathy” work in diverging directions, I must reckon with my “self” as containing aspects of both self-consciousness and personhood proper, the latter incorporating yet exceeding the limits of individual self-consciousness and the encounter between individual self-consciousnesses. From this standpoint, caring thinking can be said to incorporate and exceed the limits of creative thinking, which remains beholden to the standpoint of the individual self. Put differently, whereas in the mode of critical thinking I subtract my self-consciousness, so to speak, and aim to be purely conscious of the object of analysis, while in the mode of creative thinking I act as a self-consciousness looking out from myself toward the other, in caring thinking I become a person who strives to see myself as another as well. In other words, while in logically analyzing I bracket myself and others from my considerations, and while in imagining I actively reach out to the other, in caring thinking I “passionately” draw the other into communion with myself (Sharp, 2018 [1995], p. 115). And just as critical thinking takes us to the point where it must be supplemented by creative thinking, so is creative thinking fulfilled at the point where it must open onto caring thinking. Critical, creative, and caring thinking stand for nested processes of realizing my personhood.

In this way, genuine selfhood on the level of the individual, that is to say self-conscious personhood, is born out of the “struggle against one’s habitual self” which is facilitated by the critical, creative, and caring thinking that governs CPI (Sharp, 2018 [1996a], p. 58; Splitter, 2018, p. 99). The community of philosophical inquiry is in this sense “a community of persons-in-relation” (Sharp, 1987, p. 16). “Caring thinking” fulfills the process of self-correction to the extent that “critical” and “creative” thinking are carried out competently as well (Sharp, 1988, 2004).

ann sharp and the trilateral model of personhood

The foregoing reveals how the model of personhood Sharp conceptualizes is “relational and holistic”, interrelating “the growth of self-awareness” with “the awareness of other, and the awareness we share” (Splitter, 2018, pp. 99-104). Thus, for Sharp, there are three actors at play in CPI: the I, the You, and the We. As we have seen in the previous section, while both critical and creative thinking advance us along the way toward understanding and embracing this dynamic as a trilateral relationship, it is caring thinking that perfects the process and brings it to completion. Caring thinking is a necessary undertaking for examining the value of who one is, a question that inevitably brings out one’s intrinsic relation to the social and natural environments one inhabits, opening up a window onto oneself not only as a twofold “I-and-thou” relationship, but indeed as threefold relation, embodying simultaneously a relation of self to others and of individual selves (whether mine or others’) to community.

Figure 1 Personhood as a Trilateral Relationship, Mapped onto Critical, Creative, and Caring Thinking

Based on such claims, Sharp declares that there is an “ontological dimension” unaccounted for in P4C literature prior to her intervention (Morehouse, 2018). The ontological dimension emerges when caring thinking introduces the development of personhood as an “existential” question about who I, others, and the world at large are. Caring thinking brings not only myself, but others and the totality of myself and others, which is community, into intentional relation.

As already mentioned, this “triangular model of awareness” (Splitter, 2018, p. 104) implies that personhood, according to Sharp, is inherently threefold. True to her pragmatic and transactionalist roots, which emphasize the essential social mediation of personhood (Kennedy, 2004, p. 210), the foregoing statement is consistent with Sharp’s argument against the possibility of discovering personhood and self-knowledge through introspection (Sharp, 2018 [1996a], p. 55). Personhood and self-knowledge cannot be discovered through introspection, because they are essentially rooted in embodied intentionalities, subjects whose discovery reveals a reality which is “out there” just as much as “within”. The question now becomes: How do the three players in CPI - myself, others, and community; the I, the You, and the We - ontologically relate or present to one another?

the spiritual relationship and the problem of closure

As Leonard Nelson had perceived in the 1920s, any thorough analysis of concepts amounts to a “regress to principles” (Nelson, 1949, p. 10). Clearly, part and parcel of this regress is that it will be open ended: at each stage of “regressive abstraction” a new horizon will open up, inviting the inquirer to engage in further analysis. This open-ended aspect of philosophical inquiry has been defended and articulated extensively by Sharp and other theorists of CPI, such as David Kennedy. Yet it also stands to reason, with equal force, that such regress will only be fulfilled when the principles it arrives at provide a satisfactory (though not necessarily terminal) form of closure to the inquiry.

This complementary dimension of philosophical inquiry, namely, the dimension of closure, has not received nearly the same level of rigorous attention in the literature as the dimension of openness. The problem relates directly to the trilateral conception of personhood as articulated by Sharp. Indeed, it is this problem that Sharp attempts to address through her writings on CPI as a spiritual space and on the element of faith constitutive of the threefold relationship through which personhood is embodied.

One location worthy of investigation in Sharp’s account of personhood and faith is her grounding of the relationship between self and other in a metaphysics of direct encounter. This is the position adopted by Ann Sharp in her essay, co-authored with Megan Laverty, entitled “Looking at Others’ Faces” (Sharp & Laverty, 2018). In this essay, Sharp and Laverty follow Levinas in giving a privileged place to the direct encounter of the other as an immediate experiential ground that ties together the three actors at play in CPI: self, other, and community (Sharp & Laverty, 2018, p. 122; cf. Sharp, 2006). While there is no doubt that a fully-fledged conception of the community of inquiry must account for the physical embodiment of the inquirers and the process of inquiry itself, given the essay’s primary concern with the intimate relationship between self and other, the account presented in this essay is not the place to look for Sharp’s thoughts on the essentially socially mediated aspects of CPI and personhood.

Given Sharp’s rich and varied philosophical output, encompassing scholarly articles, journalistic essays, conference presentations, and interviews, it is difficult to distill first principles in Sharp’s thought regarding this matter. In other places, Sharp seems to also adopt a seemingly antithetical position to the one just noted, which may be seen as balancing out her privileging of direct encounter. Consider her claims that community itself stands for a unique “unity of minds under the thread of purpose” (Sharp, 1997, p. 73). Clearly, between the individual, physiologically embodied person and the “unity of minds” that is community, no “looking at the face” can take place. Yet both “persons”, if we are allowed to call them that, are presented as “persons-in-relation”. Sharp seems to be speaking of two kinds of personhood, seemingly incompatible, though both share the attribute of existing relationally, in the ways delineated above: the concrete personhood of the individual inquirer(s) and the more elusive “personhood” of the community. The question remains: how do these two modalities of personhood (individual and collective) relate to one another? We are confronted here by a problem of closure, of closing the triangle whose base extends between self and other(s), and whose apex represents the collective (see Figure 1). Put differently, unless we can give a satisfactory account of the manner in which the individual(s) relate to and, thus, become present to the collective, and vice versa, we risk undermining the threefold model of personhood which is philosophically foundational to CPI practice, or at least for Sharp’s conception of CPI.

faith as a function of closure

A question that had long preoccupied Sharp, especially in her later years, was the extent to which it is possible to square the spiritual with the intellectual, imaginative, and ethical dimensions of CPI (cf. Sharp, 1997, p. 3). In what follows, I will identify one way in which faith serves as a function of closure in the community of philosophical inquiry.

Sharp argued that the relationship of personhood at work in CPI has the features of a life in faith (Sharp, 2018 [2004], p. 235). If so, the underlying conception of “faith” highlighted by Sharp may benefit from further clarification as to how it can account not only for the openness necessary for collaborative inquiry to genuinely take place, but also for the sense of closure with which it furnishes the participants. It is only reasonable to expect that the modality of faith which can emerge within a community of philosophical inquiry will have to account for the shared experience of critical, creative, and caring thinking, not leap over it. But with a concept of faith that needs to publicly account for itself, we are on entirely different grounds from any notion of faith as a strictly private affair, an affair of “the heart”. What kind of faith might this be?

A clue toward addressing this question may be glimpsed in Leonard Nelson’s description of “the Socratic spirit” as “the stout spirit of reason’s self-confidence, its reverence for its own self-sufficient strength” (Nelson, 1949, p. 24). The “faith” at work in CPI, in its commitment to Socratic dialogue, can likewise be depicted as a confidence in reason pressed upon the philosophical inquirer by reasoning itself, a confidence of reason in itself - a confidence, moreover, that is eminently articulable and thematizable: were it not, it would have no place in CPI theory and practice. Naturally, a faith of this sort will ebb and flow in line with its relation to reasoning. The intensity of this faith, therefore, will be determinable by the degree to which critical, creative, and caring thinking succeed in their coordinated activity. By no means, then, is this faith pregiven, guaranteed, or otherwise unconditional. In fact, what distinguishes it from private notions of faith would be precisely that it is thoroughly conditional. It is because of this that our intelligent faith in the meaning and beauty furnished in one’s life by the community of philosophical inquiry, just like our intelligent sympathy, will steer away from the risk of “collective solipsism”, which Kennedy cautions against (Kennedy, 1994, p. 16), and which Sharp refers to as “a mob where the collective mind takes over” (Sharp, 2012, p. 9). In other words, this modality of conditional faith serves equally to shelter the individual from the tyranny of the community, even as it locates community within the structure of personhood that manifests itself in collaborative philosophical inquiry.

Phenomenologically, that is, to the empirical, “interested” inquirer, the community (as a sought-after coordination of perspectives) may procedurally or heuristically appear as an ultimate horizon toward which one may look as an ideal. But by the sheer drive of its own momentum, CPI practice opens one up to the ontological dimension, that which is constitutive of the reality of experience, particularly through one’s experience of caring thinking, as Sharp had argued. Ontologically, therefore, we can say that Sharp’s concept of personhood entails that community is always-already present as a basic, structural element of genuinely collaborative philosophical inquiry. Its presence, as Sharp suggests, exhibits the attributes of a spiritual relation, a characteristic of CPI that goes over and above the dynamics of critical, creative, and caring thinking, uniting them together in a substantial sense, beyond the merely procedural. Ontology, viewed in this way, would align not only with Aristotle’s classical identification of ontology and theology, but also with Kennedy’s conception of the community of philosophical inquiry as “the discursive master-form of the emergent epoch of the intersubject [which] expresses the possibility” - and perhaps the actuality, as well - “of overcoming the contradiction between two poles of subjectivity: the ‘autonomous’ discrete subject and the collective being” (Kennedy 2004, 212; cf. Sharp, 2018 [2004], p. 236). In addition to Sharp’s own statements concerning this matter, I have attempted above to suggest one way in which that element of faith can be conceptualized, following the thread offered by Leonard Nelson’s conception of faith as a “self-confidence of reason”.

conclusion

This paper sought to clear a space for considering Ann Sharp’s thoughts on the structure of intentionality or the modes of presence governing the connection between one’s own personhood, the personhood of others, and the status of community as a “person-in-relation” or “greater self” in CPI, such that the community can be conceptualized, as intended by Sharp, as “actually a means and an end, satisfying and worthwhile in itself” (Sharp, 2018 [1991], p. 245-246). As often happens in the process of philosophical inquiry, I was only able to suggest a tentative clarification of one of the more complicated aspects of Sharp’s account of the relationship binding together and, in so doing, mutually constituting the personhood of inquirers (self and others) and community. The aspect in question is reflected in Sharp’s view of faith as the expression of a spiritual bond that makes a unified whole out of the interplay of the three distinct persons-in-relation (self, other(s), and community as a “greater self”) that manifest themselves in CPI practice.

I have suggested, further, that Leonard Nelson’s idea of “the Socratic spirit”, as an expression of reason’s self-confidence, may furnish us with a conception of faith more suitable for the demands of CPI than a view which sees faith as a strictly private matter. While the development of the latter suggestion would require a standalone treatment, I believe that it has the potential to offer a basis from which one may rigorously articulate Sharp’s conception of the spiritual relationship that brings together the critical/analytic, creative/imaginative, and caring/ethical dimensions of personhood as embodied in CPI. Furthermore, while Sharp compellingly highlighted the relational ontology of personhood at play in CPI, the account one gleans from her various writings on the topic can benefit from an extended conceptual treatment of exactly how individual(s) and community are reciprocally related and mutually constituted. As noted above, while we can locate a fully-fledged argument in Sharp’s work for the ethical relation that ties the self to others as individuals, namely through the immediacy of bodily encounter, one is hard pressed to find an equally rigorous articulation of the foundational bond tying individual selves to the community as a greater self in her work, despite the fact that Sharp clearly believed in and defended the latter view just as strongly, if not in stronger terms, throughout her career.

As mentioned in the previous section, Sharp was preoccupied in her later years with the question “whether it was possible to combine a spiritual and religious dimension with […] the basic assumptions of Philosophy for Children” (cf. J. Bornstein’s introduction to Sharp, 2012). In highlighting the significance of considering community itself as a unique “person-in-relation”, or as an actively existing and not only projected “unity of minds under the thread of purpose” (Sharp, 1997, p. 73), my aim was to suggest one way in which inquiry into personhood may serve as a viable framework within which the spiritual question that animated Sharp’s writings for so long may be addressed. If the foregoing exploration furnishes future inquirers with working conclusions that will enrich the inquiry and, hopefully, propel it further, then it has succeeded in achieving its goal.

Looking forward, it may seem that the difficulties in conceiving community as a person-in-relation are compounded by the question of how the suggested personhood of community and the personhood of the individual inquirer(s) can encounter one another: what kind of intentionality presents these relata to one another? As I hinted above, this is possibly a point where the ethics of direct encounter, through which Sharp has accounted for the deep presence of individuals (self and other(s)) to one another, will be of little use: the collective has no “face”, certainly not in the sense of an immediately identifiable physiological presence. I propose that the question can be somewhat disambiguated by attending to the kinds of embodiment in which individual and communal personhood are manifested, respectively. This, perhaps, will aid us in articulating the conditions under which the two modalities of personhood - individual and collective, finite and “infinite” (in the sense of collective and self-enclosed) - may come into contact in a comprehensive structure of intermediated presence.

As Sharp noted, intentionality is nothing less than “the structure which gives meaning to experience” (Sharp, 2004, p. 212). Illuminating the intentionality structure that informs the relationship between the finite/individual and the infinite/collective modes of personhood thus promises to more explicitly disclose the meaning of self-knowledge, both for the individual self and the “greater self” of the community. By so doing, the “spiritual” relationship binding the two together may be articulated with greater clarity. To be sure, Sharp may have been the first to write on this issue as it relates to P4C and CPI, but later philosophers of education, such as David Kennedy, have provided more extensive and systematic accounts. For instance, it is in grappling with the multifaced reality of the intentionality structure that binds the individual to the collective that Kennedy articulates his conception of the abovementioned “intersubject”. However, the exploration of Kennedy’s development of this concept must be set aside for future inquiries dedicated to his work.