Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Acta Scientiarum. Education

versión impresa ISSN 2178-5198versión On-line ISSN 2178-5201

Acta Educ. vol.44 Maringá 2022 Epub 01-Ago-2022

https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v44i1.62319

TEACHERS' FORMATION AND PUBLIC POLICY

An analysis of educational policies of curriculum and teacher training for religious education in Brazil after LDB 1996

1Centro de Ciências do Homem, Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense Darcy Ribeiro, Av. Alberto Lamego, 2000, 28013-600, Campos dos Goytacazes, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil.

The current study started from two problematizations: (1) what interests/contents are making up the curriculum of Religious Education? (2) How do these contents relate to the training policies of these teachers? Sources used in this study were: Brazilian educational legislation relevant to the subject and a survey in the official database of courses and Higher Education Institutions in Brazil. The objective was to analyze the changes and continuities in the scope of legal and pedagogical interpretations concerning the selection of contents and to map the offer and configuration of teacher training courses for religious education. The methodology counted on the contribution of the bibliographic review in the scientific literature on the subject, and culminated in the elaboration of a mapping of the offer of initial training courses in the national territory with the use of four descriptors for the search: (I) ‘Science of Religion’, (II) ‘Sciences of Religion’, (III) ‘Sciences of Religions’, and (IV) ‘Religious Teaching’. The research results are twofold: (1) It is necessary to recognize and reflect on the dialogue and mobilization of religious institutions in the process of dispute over the definition of the contents of Religious Education in public schools. The other result (2) refers to the possible impacts of the current political scenario of regulation for teacher training (abbreviated, without the emphasis on the research and teaching relationship, based on the nonpresential modality) as a market niche, and not as a omnilateral training view. It is concluded that even though we can currently experience an apparent victory in the regulations for the control of content and teacher training along the lines proposed by the market-oriented model, it must be agreed that there is a distance between what the official curricula propose and what is effectively appropriate in the different learning situations in school reality.

Keywords: legislation; education; teachers; religion; state; Brazil

O estudo em tela partiu de duas problematizações: (1) quais interesses/conteúdos estão compondo o currículo de Ensino Religioso? (2) Como estes conteúdos se relacionam com as políticas de formação destes professores? As fontes usadas neste estudo foram: as legislações educacionais brasileiras pertinentes à temática, e um levantamento na base de dados oficial dos cursos e Instituições de Ensino Superior no Brasil. O objetivo foi analisar as mudanças e permanências no âmbito das interpretações jurídicas e pedagógicas concernentes à seleção dos conteúdos e mapear a oferta e a configuração dos cursos de formação docente para o ensino religioso. A metodologia contou com o aporte da revisão bibliográfica na literatura científica sobre o tema, e culminou na elaboração de um mapeamento da oferta de cursos de formação inicial no território nacional com a utilização de quatro descritores para a busca: (I) ‘Ciência da Religião’, (II) ‘Ciências da Religião’, (III) ‘Ciências das Religiões’, e (IV) ‘Ensino Religioso’. Os resultados da pesquisa são de duas ordens: (1) É preciso reconhecer e refletir sobre interlocução e mobilização das instituições religiosas no processo de disputa pela definição dos conteúdos do Ensino Religioso na escola pública. O outro resultado (2) se refere aos possíveis impactos do atual cenário político da regulação para a formação de professores, (aligeirada, sem a tônica na relação pesquisa e ensino, baseada na modalidade não presencial) como um nicho mercadológico, e não como uma visão de formação omnilateral. Conclui-se que ainda que atualmente possamos experimentar uma aparente vitória nas regulações pelo controle dos conteúdos e a formação docente aos moldes propostos pelo modelo mercadológico, há que se convir que existe uma distância entre o que os currículos oficiais propõem e o que é efetivamente apropriado nas diversas situações de aprendizagem na realidade escolar.

Palavras-chave: legislação; educação; professores; religião; estado; Brasil

El estudio en pantalla partió de dos problematizaciones: (1) ¿qué intereses/contenidos están conformando el currículo de Educación Religiosa? (2) ¿Cómo se relacionan estos contenidos con las políticas de formación de estos docentes? Las fuentes utilizadas en este estudio fueron: la legislación educativa brasileña relevante para el tema y una encuesta en la base de datos oficial de cursos e instituciones de educación superior en Brasil. El objetivo fue analizar los cambios y continuidades en el alcance de las interpretaciones legales y pedagógicas sobre la selección de contenidos y mapear la oferta y configuración de los cursos de formación docente para la educación religiosa. La metodología contó con el aporte de la revisión bibliográfica en la literatura científica sobre el tema, y culminó con la elaboración de un mapeo de la oferta de cursos de formación inicial en el territorio nacional con el uso de cuatro descriptores para la búsqueda: (I) ‘Ciencia de la Religión’, (II) ‘Ciencia de la Religión’, (III) ‘Ciencia de las Religiones’, y (IV) ‘Educación Religiosa’. Los resultados de la investigación son dos: (1) Es necesario reconocer y reflexionar sobre el diálogo y la movilización de las instituciones religiosas en el proceso de disputa por la definición de los contenidos de la Educación Religiosa en las escuelas públicas. El otro resultado (2) se refiere a los posibles impactos del actual escenario político de regulación de la formación docente (aligerada, sin énfasis en la relación investigación y docencia, basada en la modalidad no presencial) como nicho de mercado, y no como una vista de entrenamiento omnilateral. Se concluye que si bien en la actualidad podemos vivir una aparente victoria de la normativa de control de contenidos y formación docente en la línea que propone el modelo de marketing, hay que reconocer que existe una distancia entre lo que proponen los currículos oficiales y lo que es efectivamente apropiado en las diferentes situaciones de aprendizaje en la realidad escolar.

Palabras clave: legislation; education; professors; religion; condition; Brazil

Introduction

This study reflects and analyzes the changes and continuities in the scope of the pedagogical and legal aspects contained in the curricula and in the legislation for Religious Education (RE) within the national territory. To examine how the configuration of religious learning processes and the definition of teaching knowledge necessary for professionalization are understood, since in the target activity of schooling, learning, the teacher is the agent of their pedagogical practice at school. In this sense, to give shape to meaningful learning for the student, it is necessary to offer professional formation to teachers to act in order to build a theoretical and practical training.

Part of the answer to the problematization posed for this study lies in the fragility of the collaboration of the federative pact. When the Brazilian State (Union) is faced with controversial guidelines, as is the case of the issue of secularity in education, roughly speaking, it tends to leave some generic orientation and leave to the federated entities (states and municipalities) the definition of attributions for the ‘problematic agenda’. Here is an example of this with RE.

As of 1996, when the Law of Directives and Bases (LDB) was enacted, working groups were established for the elaboration of National Curriculum Parameters (PCNs) for all school subjects, except for Religious Education; what motivated the Permanent National Forum for Religious Education (Fonaper) to create PCNs for RE.

According to a report by a member of the Fonaper coordination, the group at that time consisted of professors, religion scholars, and religious people and leaders who voluntarily contributed to the elaboration of curricular parameters to guide RE. At the time, the Ministry of Education (MEC) did not appoint any commission to discuss specific parameters for RE, so the group met without government approval and composed the text (Rodrigues, 2015, p. 24).

However, this curricular parameter for RE elaborated by Fonaper and published by the Ave-Maria publisher in 1997 did not have MEC’s [Ministry of Education] approval, which followed the opinion of Roseli Fischmann, appointed by the Ministry to examine a process that had been opened in the cabinet of the Minister of Education. Fischmann (2006) publicly exposed her memory on the subject:

There, I was asked to give an opinion on a text that sought to mimic the PCNs’ documents, […] as if they were official documents. At the time, I had the feeling that I had in my hands a document that could be that of someone who decides to launch their ‘version’ of the Constitution, and still asks themselves ‘why not?’. In other words, it was clear that the concept of democracy and respect for the legal order was very relativized, both by the people who prepared that text and by those who made it reach the Minister’s hands directly, with explicit pressure present in the request that opened the process, cutting the path of respect for the public interest.

I felt it as violence and, in the role of a specialist who had been advising the MEC on the subject, through the theme of Cultural Plurality, I did what I considered I should do. My answer was direct, and soon after it was endorsed by the PCNs’ team and by the coordination, unanimously, and in the same spirit it was forwarded to the minister by the then secretary of elementary education. […] I also invoked, attaching it, the opinion of Dr. Anna Cândida da Cunha Ferraz (1997), from the USP Law School, on the matter, which had been prepared at my request when I joined the Commission of the State of São Paulo […] With this, not only was the original conception of the PCNs maintained, which had been under discussion in its two versions that went to reviewers and regional meetings throughout Brazil throughout 1995 and 1996, but subsidy was also met for the article specifically focused on the theme in the Law of Directives and Bases of Education, which was approved in December 1996 (Fischmann, 2006, p. 226-227, emphasis in the original).

Thus, Religious Education, for not having a disciplinary treatment, was defined as a ‘transversal theme’ of Brazilian cultural plurality (Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais, 1997). And not as a curricular component for basic training. It is worth noting that, according to the aforementioned report, since the original conception of the PCNs, RE was already left out, even though its offer was mandatory by the education systems. In an evident gap left by educational policies, and as voids are always occupied in spaces of power, these gaps in educational policies for the RE were filled by the interests of Christian churches. Although the Fonaper is not a confessional entity, its composition includes Christian denominations of different origins, and the leadership (covert or not) of the Catholic Church in this institution has been observed since its foundation.

This gap in the curricular issue for the RE allowed the action coordinated by Fonaper in the sense of building knowledge to compose school curricula. Through this articulation, the National Curriculum Parameters for Religious Education (PCNER) were disseminated throughout the national territory, since the second paragraph of Law No. 9475 (1997) established that the educational systems should listen to civil entities constituted by diverse religious denominations. Now, the first civil entity constituted by different religious denominations was Fonaper, the same one that disseminated the PCNERs among its networks, covering the absence of the regulatory power of the Union in the consolidation of an RE curriculum that: “[…] in the capacity of a transversal theme, therefore, a set of learnings or legitimate knowledge that requires a place in school curricula is not recognized, possibly also because religion is not recognized as an ‘object’ of study and research, that is, not only as a private belief” (Rodrigues, 2015, p. 29, emphasis in the original).

This legal perspective of RE as a transversal theme will have a new modulation as of 1998, with the establishment of the National Curricular Guidelines for Elementary Education by the Basic Education Chamber (CEB) Resolution No. 2, of April 7, 1998. In this regulation, the “[…] Religious Education, in the form of art. 33 of Law 9394, of December 20, 1996 […]” is established as one of the areas of knowledge of fundamental education in subparagraph b of item IV of art. 3 (Resolution No. 2, 1998).

Therefore, in 1998, the DCNs determined ‘Religious Education’ as an area of knowledge that is part of Elementary School. Only in 2010, when new National General Curriculum Guidelines for Basic Education were established (Resolution No. 04, 2010), the Ministry of Education (MEC) elevates the status of RE to a mandatory curriculum component in Elementary Education within the Common National Base. In this document, ‘Religious Teaching’ is established both as a curricular component and as an area of knowledge. What would lead to this terminological change between the two DCNs regarding the knowledge area ‘Religious Education’ in 1998, to ‘Religious Teaching’ in 2010?

Indeed, it is urgent to refine these three terms: ‘area of knowledge’, ‘Religious Education’ and ‘Religious Teaching’. In 2005, the Education and Religion Research Group (GPER) published a bulletin on its website, organized by researcher Sérgio Junqueira, entitled ‘Religious Teaching in Question’, in which the authors define the areas of knowledge in basic education:

The areas of knowledge are structured frameworks for reading and interpreting reality, essential to guarantee the possibility of citizen participation in society in an autonomous way. Each of the ten areas helps students understand the society in which they live and can interfere in the space and history they occupy; because one of the concerns of Basic Education is the formation of the citizen and that the studies that children and adolescents carry out contribute to the studies and the work they will perform later. In other words, it is a relationship of the present, a re-reading of the past and a construction of the future (Junqueira, 2005, p. 7-8).

This quote understands RE as an area of knowledge of Basic Education and this means thematizing the religious phenomenon from the early grades, as a way of reading and understanding reality in order to contribute to the maintenance of the sense of secular State in Brazil, admitting the relevance of the religious fact not only as a political element, but also as a constituent element of our cultural formation.

Thus, the understanding of the term ‘Religious Education’ is unilaterally linked to the political component, to the legal framework, without worrying about culturally problematizing its pedagogical developments, since the contents are the responsibility of the churches. ‘Religious Education’ therefore refers to the recognition of its nature as an area of knowledge, but which was not configured as a disciplinary character, as an integral element of a curriculum. As mentioned […] there was, until the end of the 1990s, an understanding that religious education would not go beyond the contours of a ‘transversal theme’, and another interpretative key of political bias can explain this understanding:

The laws in force had laid new bases for establishing RE in school (Law 9475/97 and Resolution 2/98 of the Basic Education Chamber), at the time of its operationalization, this old principle of the right of the believing citizen to receive religious education in the school environment prevails. The principle stems from an agreement between Churches and State. The State offers the formal guarantee of this enforcement without going into the merits of the teaching itself (Passos, 2011, p. 113).

In this interpretation, more than a ‘transversal theme’, Religious Education is a political path in which the State is responsible for guaranteeing the offer of RE, and for the churches to carry out their doctrines in a veiled way in the form of school programs. Hence, both win: the State guarantees the legitimacy of its regulatory action as being of ‘neutrality’ in the intimate (private) scope, that is, of not intervening in ecclesial issues, while the churches of hegemonic composition reiterate their confessional heritage not only in the private sphere, but also in the public. In this way, “[…] the discussion on the epistemology of the RE constitutes, in fact, a subject that does not interest, in principle, neither the State nor the Churches, being for both a politically inconvenient issue” (Passos, 2011, p. 113).

However, despite this political inconvenience for the epistemological development of RE between the two main actors (Church and State), the construction of theoretical and methodological knowledge in an epistemological perspective for RE will be discussed by the scientific and academic community, initially assuming a counter-hegemonic form in scientific culture.

Thus, in the early 2000s, the beginning of the construction of a sketch of a new facet for RE was started, culminating in the consolidation of a specific area for this, which, since 2010, has been experimented with as a contribution to a discipline (Resolution No. 04, 2010). In this way, RE is linked not only to the political, but to a broader educational and pedagogical contingent, the cultural one. By being qualified as a discipline, ‘Religious Teaching’ presupposes a specific area of professional activity of the teacher whose target is the subject, religious or not, who inquires about the reasons for being religious inside or outside religion, from inside or outside the religious group, or having no religion at all.

Thus, the question posed, schools - from public and private networks - are called upon to provide their students with knowledge and provide them with conditions for the development of critical reflection, so that they are able to understand:

a) That the different religious traditions present in Brazil play an important role in the socio-historical constitution of this country, which today is democratic and secular;

b) That despite being different from each other, all religions deserve to be recognized as legitimate, since they reflect ways of thinking and acting in the world, which diversely represent Brazilian citizens (Rodrigues, 2013, p. 2).

In this context, intellectual products emerge, such as the collective work organized by Sena (2006), which exemplifies the ideal of demanding competence from educators in this curricular component, and which therefore proposes specific teacher training for this curricular component through a Graduation in Science of Religion. There is a collection of texts in this work resulting from the collective discussion of the lecturers at the IX Seminar on Teacher Training for Religious Education promoted by Fonaper in October 2005, in the city of São Paulo. In 2017, a book was published that presents the course of composition of degrees in Sciences of Religion (CRE) at the State University of Amazonas (UEA), State University of Pará (Uepa), State University of Rio Grande do Norte (Uern), Federal University of Sergipe (UFS), Federal University of Juiz de Fora (UFJF), State University of Montes Claros (Unimontes), Regional University of Blumenau (Furb), Municipal University Center of São José (USJ), Community University of the Region de Chapecó (Unochapecó), in addition to having a chapter dedicated to the National Network of Degrees in Religious Education (RELER) (Riske-Koch, Oliveira & Pozzer, 2017). But how to think about this process of implementation of degree courses for RE in Brazilian territory from LBD 9394/96? This is the question to be answered in the next item.

Mapping of Licentiate Degree courses in Science(s) of religion(s) in Brazil after the LDB 1996

Since 1997, the Licentiate course in Science(s) of Religion(s) has been offered continuously, to meet the demands for teacher training for the discipline. Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), with the creation of these courses, covered an existing gap in the educational policy for the training of these professionals, as the norms for their implementation are decentralized in the state education systems. The state systems, in turn, in the absence of support from the National Education Council (CNE) - which at first (1997-2010) omitted itself from the orientation for this process of adhesion regarding the selection of contents and teacher training and qualification, by reiterating that these two aspects of educational policy were the responsibility of the state systems - they depended on, roughly speaking, the interference of religious denominations. These, in the absence of greater explanation of their role, which would be heard by the state systems, and due to lack of supervision, started to dictate not only the contents, but also the norms of teacher accreditation.

The current configuration of the situation of teacher training for ER has been going through a process of reconstructions, motivated by legal frameworks and by discussions of current issues and phenomena.

In this sense, new investigations become extremely relevant about the creation of these courses within the scope of federal universities, since the State has not issued new guidelines on the creation of these courses, pointing to two problematizing situations: an absence of the CNE for decision-making or an interested omission of the Brazilian State when it excuses itself from taking decisions because it may have unclear interests about the consequences of these actions (Amaral & Souza, 2015, p. 6).

The aforementioned authors do not distinguish Licentiate in Religious Education from Licentiate in Religious Sciences (CRE). This seems to be an important fact, given that the degrees in CRE as well as the bachelors emerge from a field of studies whose genesis dates back to the turn of the 19th-20th century. In addition, as of 2018, the CNE takes a new stance on RE, through the approval of the Resolution that creates the DCNs for the CRE and allows teacher training for RE to have a secular treatment, by withdrawing from religious denominations the ability to interfere in the training of these professionals, an attitude that the HEIs were already taking when creating these courses.

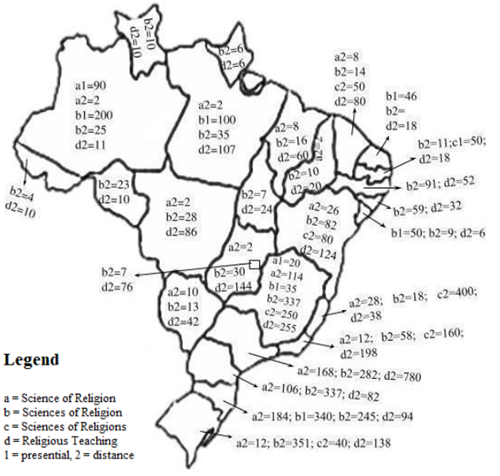

In the data collection carried out between October 2019 and January 2020 in the National Registry of Higher Education Courses and Institutions, maintained by the MEC through the e-MEC system, the courses offered in the Licentiate degree and four (4) descriptors were used: (a) ‘Science of Religion’, (b) ‘Sciences of Religion’, (c) ‘Science of Religions’, and (d) ‘Religious Teaching’. With these search criteria, the results were able to cover the degree courses in all federative units of the national territory, also taking into account the offer in the distance education modality (EAD). Although all the courses listed in the e-MEC system are in full operation, some courses have not yet started their activities, and others are in the process of being discontinued. Figure 1 presents the result of the coverage of vacancies of these courses in the Brazilian territory.

When using the term ‘Science of Religion’ as a descriptor, the result returned seven (7) courses in six (6) HEIs, all of them in activity, with three courses having already started, and four have not yet started. Among these seven courses, four (4) are on-site courses, two (2) courses in public HEIs, and two (2) in private HEIs, in addition to three (3) courses in the distance learning modality - all in private HEIs. Table 1 mentions other data from the results found in the search.

From a total of four (4) on-site courses in Science of Religion, two (2) uninitiated courses are offered by the University of Contestado (UnC) and are located in two cities of SC: Canoinhas and Curitibanos. In the first municipality, the course was created on May 20, 2010 by the University Council of the HEI, with “[…] a single entry, in a special way, to the University of Contestado (UnC), for PARFOR students” - National Basic Education Teacher Training Plan - (Resolution UnC-Consun 022, 2010). In the city of Curitibanos, the Official Gazette of Santa Catarina (SC) of April 4, 2014 shows the recognition of the Degree in CRE at UnC for a period of three years after publication. When searching on the HEI website, there is no mention of the course offering, that is, although the system indicates that this course has not been started, the university has already offered it, but there are no classes in progress (Riske-Koch et al., 2017). Therefore, currently, the face-to-face course in Science of Religion is offered at two HEIs, at UFJF and at UEA, although in the latter the name of the course appears in the e-MEC Registry as Science of Religion and on the HEI website the name is Sciences of Religion.

Source: Own elaboration based on e-MEC data.

Figure 1 Coverage of vacancies for degree courses in teacher training for Religious Education.

Table 1 Science of Religion Licentiate Courses.

| UF | HEI | Free | Vacancies | Workload | Start | Operating status | Modality |

| AM | UEA | Yes | 90 | 2800h | 06/01/2015 | In activity | Presential |

| MG | UFJF | Yes | 20 | 3050h | 05/03/2012 | In activity | Presential |

| PR | UNINGA | No | 300 | 3000h | 19/03/2020 | In activity | Distance |

| SC | UNC | No | 40 | 2835h | Not started | In activity | Presential |

| SC | UNC | No | 40 | 2835h | Not started | In activity | Presential |

| SP | UNIASSELVI | No | 600 | 2800h | Not started | In activity | Distance |

| SP | UNIMES | No | 1000 | 3480h | Not started | In activity | Distance |

Source: Own elaboration based on e-MEC data.

The other three (3) uninitiated courses, offered in the EAD modality, draw attention due to the number of vacancies they offer, and the capillarity they reach in the Brazilian territory through the support centers. However, after a search on the website of the 3 HEIs - University Center Leonardo da Vinci (Uniasselvi), University Center Ingá (Uningá) and Santos Metropolitan University (Unimes) -, no mention was found of the offer of these courses. The Uningá course also did not provide information about the selection notice. In addition, not all 300 vacancies are offered, since, according to the e-MEC system itself, the distribution of vacancies is concentrated in a new headquarters in Maringá with 100 vacancies.

When using the name of the course ‘Sciences of Religion’ as a descriptor for the search in the system, the result found in the e-MEC system covered a total of twenty-six (26) courses registered in undergraduate degree distributed in twenty (20) HEIs. Of these 26 courses, 22 are in operation, eight of which have not yet started and four are in the process of being discontinued. Among the 26 courses, fifteen (15) are on-site, nine (9) in private HEIs and six (6) in public HEIs, eleven (11) are in the distance learning modality, three (3) in public HEIs and eight (8) in private HEIs, as can be seen in Table 2 3.

Table 2 On-site Licentiate Courses in Sciences of Religion.

| UF | HEI | Free | Vacancies | Workload | Start | Operating status | Modality |

| AM | FBNCTSB | No | 200 | 3200h | 15/05/2019 | In activity | Presential |

| MA | UEMA | Yes | 0 | 3015h | 03/10/2006 | In activity | Distance |

| MG | UNIMONTES | Yes | 35 | 3360h | 01/02/2007 | In activity | Presential |

| MG | UNIMONTES | Yes | 100 | 3266h | Not started | In extinction | Distance |

| MG | PUC/MG | No | 370 | 3200h | 03/02/2020 | In activity | Distance |

| PA | UEPA | Yes | 100 | 3200h | 04/10/2001 | In activity | Presential |

| PB | UEPB | Yes | 50 | 2880h | 13/04/2009 | In activity | Presential |

| PE | UNICAP | No | 120 | 3365h | 17/02/2020 | In activity | Distance |

| PR | UNIFAESP | No | 50 | 3200h | 20/11/2019 | In activity | Distance |

| RN | UERN | Yes | 46 | 3080h | 22/02/2002 | In activity | Presential |

| RS | EST | No | 100 | 3200h | Not started | In activity | Distance |

| RS | UFSM | Yes | 150 | 3215h | 06/03/2019 | In activity | Distance |

| RS | UNINTER | No | 1000 | 3232h | 09/04/2018 | In activity | Distance |

| SC | FURB | No | 100 | 3474h | 06/01/1997 | In activity | Presential |

| SC | FURB | No | 40 | 3474h | Not started | In activity | Presential |

| SC | FURB | No | 40 | 3474h | Not started | In activity | Presential |

| SC | UNOCHAPECÓ | No | 40 | 2800h | 01/08/2008 | In extinction | Presential |

| SC | UNOCHAPECÓ | No | 200 | 3200h | 26/02/2018 | In activity | Distance |

| SC | UNOESC | No | 40 | 2805h | Not started | In extinction | Presential |

| SC | UNOESC | No | 40 | 2805h | 01/11/2009 | In extinction | Presential |

| SC | USJ | Yes | 80 | 3196h | 01/02/2008 | In activity | Presential |

| SE | UFS | Yes | 50 | 2805h | 26/09/2011 | In activity | Presential |

| SP | UNIÍTALO | No | 100 | 3200h | Not started | In activity | Distance |

| SP | UNIÍTALO | No | 100 | 3200h | Not started | In activity | Presential |

| SP | CEUCLAR | No | 300 | 3250h | 27/01/2020 | In activity | Distance |

| TO | FECIPAR | No | 120* | 2910h* | Not started | In activity | Presential |

Source: Own elaboration based on e-MEC data.

With the descriptor ‘Sciences of Religion’, the search returned five (5) HEIs with more than one course in the system: Furb, with three face-to-face courses, one in activity and the other two face-to-face courses (Sciences of Religion - Religious Teaching) in educational units outside the headquarters that have not started; UniÍtalo, which did not start either of the two courses; Unoesc, which maintains two (2) processes of extinction of the Sciences of Religion courses, one of which was in 2009 in partnership with the State Department of Education (SEE) of SC to offer the CRE course by Parfor; Unimontes, which maintains an on-site course and whose distance learning course is in the process of being discontinued and has not yet started; Unochapecó, which does the opposite, maintaining a recently created distance learning course (2018), with its face-to-face modality, in operation since 2008, undergoing a process of extinction.

Fecipar is listed in the e-MEC system as a not started face-to-face course, but the website data does not have information on the number of vacancies, course workload, not even on the website of the maintainer of the Faculty of Education, Sciences, and Letters de Paraíso (Fecipar) there is mention of the course. Thus, the data listed in Table 2 were obtained in a survey in the Official Gazette of the state of Tocantins.

The research found two documents about the HEIs on the CRE course: the first, Resolution No. 168 of December 27, 2009, whose art. 1st resolves to “Approve the Curriculum Structure of the Degree in Science of Religions, with 2910 h/y, 60 biyearly vacancies, minimum payment period of 8 semesters to a maximum of 16, in the night shift” (Resolution CEE-TO, No. 168, 2009, p. 20), the second refers to the opening of a public notice for the selection process for the 2011/1 entrance exam (Opinion CES/CEE-TO, No. 360, 2010, p. 22). Although in the system it is listed as a not started course, there are records of two entrance exams for admission to the course: one in 2010 and another in 2011. The term used is Sciences of Religions.

The course of Sciences of Religion in the distance modality of EST College is listed, in the e-MEC system, as without a forecast for the beginning of the course. However, the HEI website released a note with reference to the future offer of the course, but still without details about the public notice for admission. Regarding the other three (3) distance learning courses, from the Catholic University of Pernambuco (Unicap), the Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais (PUC-MG) and the Claretiano University Center (Ceuclar), all of them have information on their websites about admission on the course.

Among the eighteen (18) courses reported by the e-MEC as started and in operation, ten (10) are in-person courses, seven (7) in public HEIs. Among the eight (8) degree courses in the distance modality, two (2) are based in public HEIs: The Uema course started on 10/03/2006, but is currently inactive (Riske-Koch et al., 2017), which is why it is the only course with zero vacancies in the system. UFSM offers the distance learning course through UAB, being the only HEI to offer this course through this program and, currently, the only public HEI to offer the course in this modality. Among the six distance learning courses based in private HEIs, two of these are in Catholic denominational HEIs: The Catholic University of Pernambuco (Unicap) and the Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais (PUC-MG); a course is in a community HEI (Unochapecó); and the three remaining private HEIs that offer degrees are: Uninter, UniFaesp, and Ceuclar.

When using the descriptor ‘Sciences of religions’, the e-MEC system presented two results: a face-to-face course in a public HEI and distance course in a private HEI, as shown in Table 3 4.

Table 3 On-site Licentiate Course in Sciences of Religions.

| UF | HEIs | Free | Vacancies | Workload | Start | Operating status | Modality |

| PB | UFPB | Sim | 50 | 2880h | 13/04/2009 | In activity | Presential |

| ES | FUV | Não | 1000** | 3200h | 04/02/2020 | In activity | Distance |

Source: Own elaboration based on e-MEC data.

The UFPB course has an interesting memory that dates back to a postgraduate initiative in the Sociology Program dated 1994, which offered the Optional Subject ‘Religion and Society’, which then developed the Religare, Research Group on Religion and Religiosity at CNPq in 1996. Based on the extension experiences, the group received a demand in 2005 from the Permanent Commission for Religious Education of SEE-PE for a training course for RE teachers, which gave rise to a specialization course, promoting the creation of a Strictu Sensu Program in Sciences of Religions in 2006 (Miele & Possebon, 2012). With regard to the Graduation course in Sciences of Religions at UFPB, there is also a mention of the influence of the Permanent National Forum for Religious Education (Fonaper) in the configuration of these courses:

Beyond faith, the study of the religious phenomenon in public schools must recover the history of different religions, of the most different peoples, from antiquity to today, giving students the opportunity to understand the relationships that human beings establish with the transcendent, with the divine, with the sacred, and how they apply their beliefs in the relationships they establish with the society in which they live, and with themselves. This new conception of religious education had the outstanding performance of the Permanent National Forum of Religious Education (Miele & Possebon, 2012, p. 428).

This quote makes evident an effort to justify the relevance of the discipline, by arguing that this knowledge ‘beyond faith’ provides a religious formation for citizenship. Another point of view, critical of this argument, problematizes the course of Sciences of Religions at UFPB:

Firstly, it would not be feasible for the religious education teacher, who on average has a weekly class time, to address such extensive content. We know that the history of religions is a very vast topic, and the great Abrahamic religions are marked by events of difficult dimensions to be approached, without simplifications, in a short period of time. The problem becomes more complex if we include non-monotheistic creeds and syncretic religious doctrines […]. In second place […] is the issue of freedom of belief […]. Although this is a constitutional precept, to what extent can the religious education teacher effectively respect it? […]. In view of this, wouldn't the subjects of history, philosophy and sociology, mandatory in basic education, also be enough to promote these discussions without the embarrassment caused by religious faith? (Amaral, Oliveira, & Souza, 2017, p. 284).

These two antagonistic quotes about the same course bring within them the changes and the permanences that not only configure RE today, but bring up questions that involve other public spheres, such as the interpenetration of the disputes of the religious field in the political field, and that refer to the secular debate.

The last query of the survey in the e-MEC system used the term ‘Religious Teaching’ and showed as a result two (2) active Licentiate courses in the distance modality in private HEIs, the Estácio de Sá University (Unesa) and the Estácio de Ribeirão Preto University Center (Estacio). According to Table 4.

Table 4 On-site Licentiate Degree Course in Religious Teaching.

| UF | HEIs | Free | Vacancies | Workload | Start | Operation status | Modality |

| RJ | UNESA | No | 660 | 3486h | 14/06/2019 | In activity | Distance |

| SP | ESTÁCIO | No | 1930 | 3486h | 29/06/2019 | In activity | Distance |

Source: Own elaboration based on e-MEC data.

These two courses are offered by two HEIs of the same educational group, Estácio. Both the curriculum matrices are identical, and the contact telephone numbers of the two HEIs are the same. On the website of these institutions, when you click to register for the course, the page is the same as well. The data indicates that in addition to the interest of religious denominations, other marketing interests are interested in this market share, which is the training of RE teachers. Thus, the DCNs for Sciences of Religion opened the way for the offer of courses in the distance modality, as the number of places offered and the date of creation of the courses in these two HEIs allow us to infer.

Changes and permanence in current educational policies for teacher training

This survey carried out at e-MEC indicates that, despite the lack of regulation at the federal level for teacher training for Religious Education, HEIs have sought strategies to address the gap related to the lack of specific training in teaching this curricular component, generally triggered by the demands of the Education Systems, which need to resolve this issue through the positivization given by the LDB. The data collected show that, although incipient, in total there are 37 training courses for teachers in RE, with a movement towards professionalization of these teachers. If, at the beginning, the vanguard in the creation of these courses was carried out in public HEIs, today this scenario is reversed, as nineteen (19) CRE courses are located in private HEIs, with 14 of these courses being offered in the distance education (EAD) modality. This data exposes another challenge regarding the formative heritage of students who enter private HEI courses, since:

The distance education method is based on the isolation of the student and on their autonomy, on their self-didacticism. The student who cannot operate with this tuning fork is the one who evades and, therefore, does not constitute any formative heritage during the time in which they maintain formal links with the course. The dramatic aspect of all this is structural and, for the time being, we can only state it through the following questions: ‘Are we constituting, in Brazil, a gear in which the dropout student is a functional part of the scheme that finances distance education? Is this student as (or more) interesting, in financial terms, than the persevering student?’ (Giolo, 2018, p. 89).

However, dropout does not only occur in distance learning courses, although in this modality it is greater, according to data from CNE/CP Opinion No. 22 (2019, p. 7-8): “[…] analyzing all undergraduate courses, […] in the flow from 2010 to 2016, by type of education, dropout rates are high and very similar, that is, for on-site courses the rate is 55.6%, while for Distance Education (EAD) courses, [it is] slightly higher than 62%”.

The great expansion in the offer of distance learning courses for initial training contradicts what is foreseen in the third paragraph of art. 62 of the LDB, which determines “[…] the initial training of teaching professionals will give preference to face-to-face teaching, subsidiarily making use of distance education resources and technologies” (Law No. 9394, 1996). However, this has now become a dead letter in 2018 when the number of enrollments in EAD surpassed the number of enrollments in face-to-face training. Since the 1990s, the private education market has made use of this gap in the terminology ‘will give preference’ to grab this ‘share of the market’ that is teacher training. According to data from the 2018 Education Census:

For the first time in the historical series of degree courses, the number of students attending distance courses, in 2018, was greater than the number of students in on-site courses, that is, 50.2% of students in degree courses are enrolled in distance courses. Census data also reveal that the typical student in undergraduate courses is female and studies at a university. More than 80% of undergraduate students from public institutions attend face-to-face courses. In the private network, distance courses prevail, with almost 70% of students (Opinion CNE/CP No. 22, 2019, p. 8).

It is worth noting that the great growth of distance education in the field of teacher training shows how market interests override legislation, since public HEIs comply with the LDB, and private HEIs do not. In this way, the opinion recognizes that the MEC must not only ensure what is set out in the LDB, but also monitor and supervise the quality of courses in both modalities, through a system of evaluation of graduates.

The opinion, which establishes the National Curriculum Guidelines for the Initial Training of Basic Education Teachers and the Common National Base for the Initial Training of Basic Education Teachers (BNC-Training), was approved on December 20, 2019, and proclaims that to achieve the PNE goals 17 and 18, which deal with the salary equalization of these professionals with others with the same title in different careers, there are already two instruments: for goal 17, the Floor Law and Fundeb. Regarding goal 18, which deals with the career plan, all states and the Federal District have a policy for the career plan and remuneration of teaching professionals, according to a survey carried out by Inep in 2017 (Opinion CNE/CP No. 22, 2019).

Nevertheless, the teaching career is still not attractive to young people and this is due to material factors, such as poor working conditions, and cultural factors, such as the social devaluation of the profession. As studies released in 2018 by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) reveal, “[…] in Brazil, 5% of 15-year-olds want to be Basic Education teachers, compared to 21% who think about becoming engineers in the future. One of the elements that contribute to the low attractiveness of the teaching career for current generations is the low remuneration” (Elacqua et al., 2018, p. 18-19).

In the case of Opinion CNE/CP No. 22 (2019), there is a search for a link between policies for teacher training and the ten general competencies of the National Common Curricular Base (BNCC). According to art. 4 of Resolution CNE/CP No. 2 (2017), that institutes and guides the implementation of the BNCC in compliance with the LDB and the National Education Plan (PNE), which determines, for Basic Education, learning objectives to be developed by students in the following general competences:

1. To value and use knowledge historically built on the physical, social, cultural and digital world to understand and explain reality, continue learning and collaborate to build a fair, democratic and inclusive society;

2. To exercise intellectual curiosity and utilize the sciences’ own approach, including research, reflection, critical analysis, imagination and creativity, to investigate causes, develop and test hypotheses, formulate and solve problems and create solutions (including technological ones) based on knowledge of different areas;

3. To develop the aesthetic sense to recognize, value and enjoy the various artistic and cultural manifestations, from local to global, and also to participate in diversified practices of artistic and cultural production;

4. To use different languages - verbal (oral or visual-motor, such as Libras[Brazilian Sign Language], and written), body, visual, sound, and digital - as well as knowledge of artistic, mathematical and scientific languages to express themselves and share information, experiences, ideas, and feelings in different contexts, and produce meanings that lead to mutual understanding;

5. To understand, use and create digital information and communication technologies in a critical, meaningful, reflective and ethical way in the various social practices (including school ones) to communicate, access and disseminate information, produce knowledge, solve problems and exercise protagonism and authorship in the personal and collective life;

6. To value the diversity of knowledge and cultural experiences and to appropriate knowledge and experiences that allow them to understand the relations of the world of work and make choices in line with the exercise of citizenship and their life project, with freedom, autonomy, critical awareness and responsibility;

7. To argue based on facts, data and reliable information, to formulate, negotiate and defend common ideas, points of view and decisions that respect and promote human rights, socio-environmental awareness and responsible consumption, at the local, regional and global levels, with an ethical positioning in relation to care for oneself, for others and for the planet;

8. To know oneself, appreciate oneself and take care of one’s physical and emotional health, to understand oneself in human diversity and recognize one’s emotions and those of others, with self-criticism and the ability to deal with them;

9. To exercise empathy and dialogue, to resolve conflicts harmoniously and cooperation, being respected, as well as promoting respect for others and human rights, with acceptance and appreciation of the diversity of individuals and social groups, their knowledge, identities, cultures and potential, without prejudice of any kind;

10. Act personally and collectively with autonomy, responsibility, flexibility, resilience and determination, making decisions, based on ethical, democratic, inclusive, sustainable and solidary principles (Resolution CNE/CP No. 2, 2017, p. 4-5).

These essential learnings are in accordance with the propositions of Tedesco (2012), however, with the BNCC that should be built in the form of dialogue with society, defining the basic and indispensable socializing contents to universalize meaningful learning, it was not quite what occurred. At least not in its outcome, as we can see below:

In 2015, new studies were initiated by the MEC to prepare a document on the BNCC. About 120 (one hundred and twenty) education professionals, including Basic Education and Higher Education teachers from different areas of knowledge, were invited by the MEC to prepare a document that resulted in the ‘first version’ of the BNCC. This version was put for public consultation, through the internet, between October 2015 and March 2016. According to MEC data, there were more than 12 million contributions to the text, with the participation of about 300 thousand people and institutions. It also counted on the opinions of Brazilian and foreign experts, scientific associations and members of the academic community. The contributions were systematized by professionals from the University of Brasília (UnB) and the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-RJ), and subsidized the MEC in the elaboration of the ‘second version’. In May 2016, the ‘second version’ of the BNCC document was made available and submitted for discussion by around 9000 educators in seminars held by the National Union of Municipal Education Directors (Undime) and by the National Council of Secretaries of Education (Consed), throughout the country, between June and August of the same year. The document analysis methodology was carried out through discussions in specific rooms, by study areas/curricular components, and coordinated by moderators who, for the most part, presented slides with objectives and contents and the participants chose one of the following alternatives: agree, totally disagree or partially disagree and indicate proposed changes, if applicable (Aguiar, 2018, p. 11, emphasis in the original).

Although in the first and second versions of the BNCC there was a wide participation of educators and specialists, in the third version, sent by the MEC to the CNE in April 2017, there was a conservative turn in the composition of the political forces that, among other actions, implied a change in the composition of the CNE “[…] through the revocation of the ordinance for reappointment and appointment of new councilors” (Aguiar, 2018, p. 8) in which the influence and control of populist, authoritarian, and neoconservative groups practically removed or excluded the academic groups. The third version was “[…] prepared autonomously by the Management Committee” (Aguiar, 2018, p, 16) and its content went through a quick process in the bicameral commission, culminating in approval by the CNE, with three contrary votes, of Resolution CNE/CP No. 2, of December 22, 2017, and approved by Mendonça Filho, Minister of Education at the time.

The BNCC was approved with a shallow conception of education and curriculum. This base was focused more on skills than on rights and learning objectives, in line with the managerial perspective anchored in learning standards measured in national assessments linked to global policies of a network sponsored by corporations and private philanthropy, which call themselves ‘social entrepreneurs’, which advocate programs for the precariousness of teaching work and teacher training, such as the Teach For All movement. These teacher training programs are a more articulated action than Teach For America (USA) and Teach First (England) that seek to impose their multiple agenda to meet the interests of the market with conservative inspiration.

In Brazil, its correspondent is Ensina Brasil (Teach Brazil), which is based on recruiting graduates with a degree completed for a maximum of ten years, or they are likely to be graduates in licensure or bachelor's courses recognized by the MEC, undergo face-to-face or distance training, followed by a pedagogical complementation to teach classes in vulnerable schools with remuneration for two years. As the contents or objectives of the BNCC become uniform for the entire national territory, this type of program can materialize.

Ensina Brasil is in line with the supporters of neoliberal managerial policies. The program is supported or has as partners, for example, Itaú Social, Insper, Lemann Foundation, Elos Educational, Kroton, among others. Its purpose is to remove teacher training from universities and show that it is possible for newly trained young graduates to become teachers, for a short period of two or three years. There is no contradiction with the BNCC, as it is enough to apply materials and packages already oriented to the achievement of the curriculum provided for in the base. Currently, with the legal possibility of outsourcing core activities and volunteer work, it has become more flexible and possible for these young recruits to be paid by city halls, as temporary work, and with scholarships articulated by partner entities. (Hypolito, 2019, p. 198).

In the context of teacher training, this model can threaten the one based on teaching and research. Therefore, it is important to highlight the validity of the legal frameworks prior to these reactionary movements of a global agenda that are structured in ultra-liberal and mediocre molds that are nothing more than a mockery of public policies since they are not based on evidence. Thus, in order to give shape to a meaningful learning for the student, it is necessary to offer professional training to teachers to act in the sense of building a theoretical and practical training not only:

[…] in the perspective of valorization and of their initial and continued formation, the norms, the curricula of the courses and programs destined to them must adapt to the BNCC, in the terms of paragraph 8 of art. 61 of the LDB, and must be implemented within two years, counted from the publication of the BNCC, in accordance with art. 11 of Law No. 13415/2017 (Resolution CNE/CP No. 2, 2017, p. 11).

But also with the school equipped with infrastructure, technical and didactic resources for this training. In this context, the ten aforementioned competences refer to the formulation of Delacôte (1997), who relates the teaching work to that of a cognitive companion, who teaches the craft of learning and living together that only organized educational activity can provide.

Anyhow, what is already defined by the CNE is that the RE was standardized in the BNCC as a curricular component of Elementary School, and it is necessary to monitor how the state systems that expand the offer of RE for High School will regulate these curricula, since Resolution No. 4, of December 17, 2018, which provides for the BNCC of High School, does not mention ER.

In the final provisions of Resolution CNE/CP No. 2 (2017, p. 12), art. 23 determines that “[…] the CNE, upon proposal of a specific commission, will decide whether religious education will be treated as an area of knowledge or as a curricular component of the area of Human Sciences, in Elementary School”. With this future determination, the CNE will take another step towards the consolidation of educational policies for RE, by determining whether this is an area of knowledge or a curricular component in the area of Human Sciences. However, in art. 14, which delimits the competences for the areas of knowledge, ER is located as an area in item V. Indeed, in the 2010-2020 decade, a new posture of the CNE towards ER can be seen, motivated both by the political action of the Fonaper and other Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) to clarify educational policies, which, in the way they were configured in state systems, formed a true pedagogical revelry motivated by legal anomie (Cunha, 2013).

Conclusion

This study allows us to bring Gramsci’s (1999) reflection on RE as a worldview to the present, when the Sardinian author poses the issue of RE as a way of meeting the interests of Catholic clericalism, which in our times is disguised as ecumenism. Paradoxically, it is curious to note that in these articulations there is a search for consensus building, that is, the search for an approximation between the intellectual segments and the mass, which at the time of Gramsci was sewn between school and the Catholic Church; today, in the secular era (Taylor, 2010) finds in pluralism an integrated action between churches and school.

The question to be faced from this observation is: how not to let the proselytizing aspect of a religious group prevail over the others? An immediate answer comes to mind: training teachers. At this point, another problematic issue refers to the current political scenario of regulation for teacher training, in which a market interested group prepares a niche for abbreviated teacher training, without the emphasis on research and teaching relationship, based on the nonpresential modality. Not to mention that, according to the BNCC, ER must include Elementary Education and at this level of training there is a first stage, the early years (child education), in which teacher training in a specific discipline is not required, but only in Pedagogy courses and teacher-training high school courses.

Apparently, it is rare in these courses to have content or training experiences that include a methodological preparation to work with the contents for RE. In any case, future research focused on the analysis of teaching practice in RE can focus on the effects of the training model based on the contents of the BNCC and on the guidelines of the DCN-ER, paying attention to the question of the didactic transposition of the contents of the CRE in the conduction of discipline. After all, even though we can currently experience an apparent victory in the regulations for the control of content and teacher training along the lines proposed by the market-oriented model, it has to be agreed that there is a gap between what the official curricula propose and what is effectively appropriated in the various learning situations in school reality.

REFERENCES

Aguiar, M. A. S. (2018). Relato da resistência à instituição da BNCC pelo Conselho Nacional de Educação mediante pedido de vista e declarações de votos. In M. A. S. Aguiar , & L. F. Dourado (Orgs.), A BNCC na contramão do PNE 2014-2024: avaliação e perspectivas (p. 8-22). Recife, PE: ANPAE. [ Links ]

Amaral, D. P., & Souza, E. C. F. (2015). Formação docente para o ensino religioso. In Anais da Reunião Nacional da ANPED, 37 (p. 1-18). Florianópolis, SC: ANPED. [ Links ]

Amaral, D. P., Oliveira, R. J., & Souza, E. C. F. (2017). Argumentos para a formação do professor de ensino religioso no projeto pedagógico do curso de Ciências das Religiões da UFPB: que docente se pretende formar? Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos, 98(249), 270-292. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24109/2176-6681.rbep.98i249.2628 [ Links ]

Cunha, L. A. (2013). O Sistema Nacional de Educação e o ensino religioso nas escolas públicas. Educação & Sociedade, 34(124), 925-941. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302013000300014 [ Links ]

Delacôte, G. (1997). Enseñar y aprender con nuevos métodos. La revolucíon cultural de la era eletrônica. Barcelona, ES: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Elacqua, G., Hincapié, D., Vegas, E., Alfonso, M., Montalva, V., & Paredes, D. (2018). Profissão professor na América Latina: por que a docência perdeu prestígio e como recuperá-lo?. Inter-American Development Bank. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18235/0001172 [ Links ]

Fischmann, R. (2006). Ainda o ensino religioso em escolas públicas: subsídio para a elaboração de memória sobre o tema. Revista Contemporânea de Educação, 1(2), 222‑231. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20500/rce.v1i2.1506 [ Links ]

Giolo, J. (2018). Educação a Distância no Brasil: a expansão vertiginosa. Revista Brasileira de Política e Administração da Educação, 34(1), 73-97. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21573/vol34n12018.82465 [ Links ]

Gramsci, A. (1999). Cadernos do cárcere. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Civilização Brasileira. [ Links ]

Hypolito, A. M. (2019). BNCC, agenda global e formação docente. Revista Retratos da Escola, 13(25), 187-201. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22420/rde.v13i25 [ Links ]

Junqueira, S. R. A. (2005). Ensino Religioso em Questão. O que é o ensino religioso no contexto escolar? (Luzia Sena - São Paulo/SP). Recuperado de https://docplayer.com.br/12739407-Ensino-religioso-em-questao-organizado-por-sergio-junqueira-01-o-que-e-o-ensino-religioso-no-contexto-escolar-luzia-sena-sao-paulo-sp.html [ Links ]

Lei n° 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. (1996, 20 dezembro). Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília. [ Links ]

Lei nº 9.475, de 22 de julho de 1997. (1997, 22 julho). Dá nova redação ao art. 33 da Lei n° 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília. [ Links ]

Miele, N., & Possebon, F. (2012). Ciências das religiões: proposta pluralista na UFPB. Numen: Revista de Estudos e Pesquisa da Religião, 15(2), 403-431. [ Links ]

Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais. (1997). Introdução aos parâmetros curriculares nacionais. Secretaria de Educação Fundamental, Brasília. Recuperado de: http://portal.mec.gov.br/seb/arquivos/pdf/livro01.pdf [ Links ]

Parecer CES/CEE nº 360. (2010, 26 novembro). Aprovação de Edital do Processo Seletivo Vestibular 2011/I, Faculdade de Educação, Ciências e Letras de Paraíso do Tocantins. Diário Oficial do Tocantins, nº 3.285, Ano XXII, p. 22. Recuperado de: https://doe.to.gov.br/diario/1616/download [ Links ]

Parecer CNE/CP nº 22, de 7 de novembro de 2019. (2019, 7 novembro). Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Formação Inicial de Professores para a Educação Básica e Base Nacional Comum para a Formação Inicial de Professores da Educação Básica. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília. [ Links ]

Passos, J. D. (2011). Epistemologia do Ensino Religioso: a inconveniência política de uma área de conhecimento. Revista Ciberteologia. Revista de Teologia & Cultura, 7(34), 108-124. [ Links ]

Resolução CEB/CNE nº 2, de 07 de abril de 1998. (1998, 2 julho). Institui as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Fundamental. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília. [ Links ]

Resolução CEE-TO nº 168. (2009, 17 novembro). Aprova estrutura curricular do Curso de Ciências das Religiões da Faculdade de Educação, Ciências e Letras de Paraíso do Tocantins - FECIPAR, neste Estado. Diário Oficial do Tocantins nº 3108, Ano XXII, p. 20. Recuperado de: https://doe.to.gov.br/diario/1429/download [ Links ]

Resolução nº 04, de 13 de julho de 2010. (2010, 13 julho). Define as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais Gerais da Educação Básica. CEB/CNE. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília. [ Links ]

Resolução nº 4, de 17 de dezembro de 2018. (2018, 17 dezembro). Institui a Base Nacional Comum Curricular na Etapa do Ensino Médio (BNCC-EM), como etapa final da Educação Básica, nos termos do artigo 35 da LDB, completando o conjunto constituído pela BNCC da Educação Infantil e do Ensino Fundamental, com base na Resolução CNE/CP nº 2/2017, fundamentada no Parecer CNE/CP nº 15/2017. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília. [ Links ]

Resolução CNE/CP nº 2, 22 de dezembro de 2017. (2017, 22 dezembro). Institui e orienta a implantação da Base Nacional Comum Curricular, a ser respeitada obrigatoriamente ao longo das etapas e respectivas modalidades no âmbito da Educação Básica. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília. [ Links ]

Resolução UnC-Consun 022. (2010, 10 maio). Dispõe sobre a aprovação, "ad referendum" do CONSUN, da criação do curso de licenciatura em Ciência da Religião, para um único ingresso, em caráter especial, para ingressantes do PARFOR. Universidade Do Contestado, Santa Catarina. [ Links ]

Riske-Koch, S., Oliveira, L. B., & Pozzer, A. (2017). Formação inicial em ensino religioso: experiências em cursos de ciência(s) da(s) religião(ões) no Brasil. Florianópolis: SC. Saberes em Diálogo. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, E. (2013). A formação do Estado secular brasileiro: notas sobre a relação entre religião, laicidade e esfera pública. Horizonte, 11(29), 149-174. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5752/P.2175-5841.2013v11n29p149 [ Links ]

Rodrigues, E. (2015). Formação de professores para o ensino de religião nas escolas: dilemas e perspectivas. Revista Ciências da Religião - História e Sociedade, 13(2), 19-46. [ Links ]

Sena, L. (2006). Ensino religioso e formação docente: ciências da religião e ensino religioso em diálogo. São Paulo, SP: Paulinas. [ Links ]

Taylor, C. (2010). Uma era secular. São Leopoldo, RS: Unisinos. [ Links ]

Tedesco, J. C. (2012). Educación y justicia social en América Latina. Buenos Aires, AR: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

3In order to preserve the visual intelligibility of this table, we opted for the explanation of the acronyms mentioned here: Boas Novas Faculty of Theological, Social and Biotechnological Sciences (FBNCTSB); State University of Maranhão (UEMA); State University of Montes Claros (UNIMONTES); Pontifical Catholic University of Minas Gerais (PUC-MG); University of the State of Pará (UEPA); Catholic University of Pernambuco (UNICAP); State University of Paraíba (UEPB); University Center Anchieta College of Higher Education of Paraná (UNIFAESP); University of the State of Rio Grande do Norte (UERN); Higher School of Theology (EST); Federal University of Santa Maria (UFSM); International University Center (UNITER); Regional University of Blumenau (FURB); Community University of Chapecó Region (UNOCHAPECO); São José Municipal University Center (USJ); Federal University of Sergipe (UFS); Italo-Brazilian University Center (UNIÍTALO); Claretian University Center (CEUCLAR); Educational Foundation of Paraíso do Tocantins (FECIPAR).

4According to the standard used for Table 2 of this text, the meanings of the acronyms used in this Table 3 are explained here: Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB); United College of Vitória (FUV).

Received: January 31, 2022; Accepted: February 27, 2022

texto en

texto en