We understand as teacher turnover the process of teachers giving up their professional life in education. This problem stems from the high numbers of teachers who leave teaching during the first five years of their career. As an example of this phenomenon, the so-called “dropout rates” have been estimated at 40% in the United States (INGERSOLL; SMITH, 2003), similar numbers found in some provinces of Canada (KARSENTI; COLLIN, 2013; SCHAEFER; LONG; CLANDININ, 2012) or Latin American countries such as Chile (LÓPEZ, 2015). They all exemplify an issue that has been described and documented by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) for more than a decade (OECD, 2005).

Teacher turnover is often linked to the concern in public policies to “retain” a sufficient number of teachers in school (MASON; MATAS, 2015). An example of this are the mentoring programs (accompaniment) for beginning teachers (CORNEJO, 2009; INOSTROZA; TAGLE; JARA, 2007; ORTÚZAR, 2009). More in particular these policies seek to solve what has been shown by several studies: it is often the teachers with professional responsibility, strong commitment to the job as well as holding high expectations, who decide to leave school (BUZZETTI, 2005). For policy makers it is crucial to ensure the retention of these quality teachers, as there is a growing awareness that for education to be effective, quality teachers are needed in the classroom. A position gaining ground is the claim that to get good results, it is vital to keep in the classroom those teachers who are deemed to be effective (BARBER; MOURSHED, 2007; INGVARSON, 2013; OECD, 2005; SANTELICES; VALENZUELA, 2015).

We see our work as an attempt to synthesize the knowledge built around teacher turnover, by answering the question: What are the reasons teachers give for leaving the classroom? More in particular, our study focuses on the specific geographical context of Latin America.

METHODOLOGY

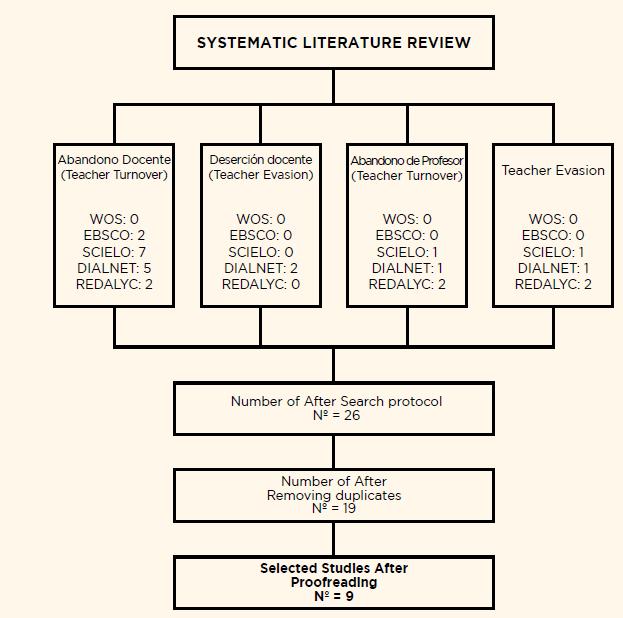

We performed a bibliographic search of the works available in databases: Web of Science (WOS), EBSCO, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), Dialnet, and Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain, and Portugal (Redalyc). In the search, we used the keywords “abandono docente” (“teacher turnover”) y “deserción docente” (“teacher evasion”) (for the search in Spanish) and “abandono de profesor” (“teacher turnover”) and “evasão de professores” (“teacher evasion”) for the search in Portuguese. We took into consideration works that met the following criteria: a) empirical studies addressing teacher turnover, b) that had been conducted in the Latin American context, and c) were published between early 2000 and June 2019.

The initial search process yielded a list of twenty-six documents. We proceeded to eliminate the repeated articles, leaving a total of nineteen investigations. We further evaluated the documents, selecting only those that met the inclusion criteria. We excluded ten studies, where turnover was only a secondary issue. Rather, they were teachers’ knowledge production, teaching reform, first experiences, labor conditions, virtual course drop-out, desertion from the legal system. One article is also devoted to a film about a teacher who leaves the classroom (FRAGA; DESSBESELL; DE CÉSARO, 2015).

Of the selected articles that met the described criteria, we excluded one, which, despite addressing teacher dropout, does not meet the empirical study criterion, the paper is an essay (GONZÁLEZ, 2018). We also excluded two others, one due to its context in Texas, United States (SASS, 2012) and the other in Turkey (DEMIRKASIMOGLU, 2018).

At the end, the procedure yielded a total of nine empirical studies conducted in Latin America on teacher turnover. Table 1 illustrates the process of systematic literature review carried out.

RESULTS

We will report the findings in three sections. First, we summarize the concepts used to describe turnover, distinguish between temporary and permanent turnover, as well as the distinction between mandatory/voluntary turnover as they appeared in the publications. Secondly, we analyze the causes of teacher turnover. In the final section, we elaborate on the concept of functional dropout, as it contributes to the discussion proposed in this study.

ABOUT THE TYPE OF TEACHING ABANDONMENT

Our analysis showed that the concept of teacher turnover is used with different meanings. In the research, the concept is used to refer to teachers who quit teaching, as well as to name those who leave the classroom, but not educational work. Finally, teacher turnover includes all educators who leave the profession. Below, we summarize the categories used in the articles reviewed:

Teacher turnover (abandono docente). In this sense, turnover means ending the teaching career. It corresponds to professionals with a teaching degree who have decided to stop working as such (LAPO; BUENO, 2002; CASSETTARI; DE FÁTIMA; FRUTUOSO, 2014; SOUTO, 2016).

Giving up teaching (dejar el aula). It refers to teachers who choose to leave the classroom and school but not the educational field, for example, those teachers who hold a job in the Ministry of Education or in teacher training institutions (GAETE et al., 2017).

Giving up education as a professional field (dejar la profesión). This is the type of turnover that consists of leaving not only the classroom and the school, but also the field of education (GAETE et al., 2017).

USE OF TEMPORALITY FOR THE NAME OF TEACHING ABANDONMENT

Another view is to distinguish between teacher turnover that is either permanent or only temporary. In some ocasions teachers decide to exchange their teaching job temporarily for another, but eventually return to the classroom. In other cases the decision to leave is a permanent one. Short dropout observed through absences from school, unpaid leave, and short leave. In the case of permanent turnover, it would be a break with both the school and the work it entails, when they give up the teaching role for good (LAPO; BUENO, 2002).

THE MANDATORY / VOLUNTARY DISTINCTION

Voluntary turnover corresponds to teachers who decide to migrate to another school. In this case, a specific educational context is abandoned in exchange for another (LAPO; BUENO, 2002). Voluntary turnover is observed in teachers who decide to leave school, but not education as a field (GAETE et al., 2017). The concept of mandatory or compulsory turnover is used when external reasons force teachers to leave, such as retirement or becoming a parent (having children of one’s own) exclusive child-rearing (GAETE et al., 2017). Along these same lines, we consider the concept of “Remoción” (evasion), which refers to leaving school as a way to escape from negative working conditions, such as bad relationships with colleagues (LAPO; BUENO, 2002). According to the articles, these evasions are often the first step to a permanent turnover.

CAUSES OF TEACHER ABANDONMENT

Initially, we prepared several tables to organize the information. However, as our analysis developed, it became obvious that we need to understand the phenomenon of teacher turnover in an interactionist way. Choosing the lens of micro-political theory proved to be effective in that respect. Quitting the profession involves more than just the act of a decision at a particular point in time. The decision to drop out eventually results from meaningful interactions between the teacher and his/her professional context. In micro-political theory people’s behavior is considered as the outcome of the meaningful interplay of the person’s biography and former training, as well as a particular professional context (KELCHTERMANS; BALLET, 2002; KELCHTERMANS; VANASSCHE, 2017). The concept, allows for a broader explanation of teacher turnover, in comparison to a psychological perspective that only takes into account individual elements and characteristics.

School micropolitics refers to power relations in daily school life, which often remain little visible or go unnoticed in the stream of day to day activities. Some authors describe this aspect as part of the professional development of the educator (SALGADO LABRA; SILVA-PEÑA, 2009; SILVA- -PEÑA, 2007). Specifically, when we analyze teacher turnover from a micropolitical perspective, we turn our attention to the more complex, local space of the professional and personal relationships within the organization.

In this way, we came to propose the analysis of the different selected texts considering the concept of micropolitical literacy (KELCHTERMANS; VANASSCHE, 2017; SILVA-PEÑA et al., 2019). This way we contributed to an integrative synthesis of the findings from the studies carried out in Latin America. Micropolitical literacy refers metaphorically to the process of learning to read and write in school micropolitics. A concept initially coined by Blase and Anderson (1995) was later developed in the research process of beginning teachers (KELCHTERMANS; BALLET, 2002; KELCHTERMANS; VANASSCHE, 2017). The micropolitical perspective points to the fact that human behavior in organisations is driven by interests, which are constituted by particular desired working conditions: self-interests, material interests, organizational interests, cultural-ideological interests, social-professional interests (SILVA-PEÑA et al., 2019). Those interests would be part of the relationship between the teaching process in the field of initial training and the school, the so-called “practice shock” (LORTIE, 1975). Our analysis takes these interests into account to organize the findings of the different articles on teacher turnover.

Self-interest. From the perspective of micropolitical literacy, this interest refers to issues related to teachers’ sense of identity, their professional self-understanding and its recognition by others (like for example colleagues or parents). In this framework, González (2013), Lapo and Bueno (2002, 2003), and Souto (2016) point out that the authorities in the educational centers have limited expectations about the teacher’s teaching. In other words, the recognition of teachers would be more connected to factors that are external to the school (extra-curricular), instead of elements in the curricular activities of teaching and learning. Consequently, teachers feel that their efforts in teaching, still don’t seem to meet or satisfy the demands of (local) policy makers (GAETE et al., 2017). They may result in a sense of de-professionalisation, i.e. the ill feeling of not being treated as professionals or having little possibility for professional development.

The studies analysed further also showed that material interests were at stake. Material interests refer to the availability of teaching materials, financial resources, the specific infrastructure, and time facilities. From the review carried out, Lapo and Bueno (2002) highlight that the institutional bureaucracy reflected in the lack of material resources, the lack of technical--pedagogical support, and the lack of incentives for professional improvement. Experiencing these gaps often developed into reasons to leave teaching. Pereira and Oliveira (2018) point to working conditions as the main factor in teacher turnover, while Souto (2016) refers to this same point, labeling it as “bad working conditions”. Likewise, Gaete et al. (2017) state that salaries, added to the scarce support from management teams and the lack of resources, are all arguments used by teachers to leave the school (GOMES; NUNES; PADUA, 2019).

A third category of interests at stake are the so-called organizational interests. These interests address issues related to formal roles at school. Here we find that some causes of teacher turnover could be considered part of this category. For example, Lapo and Bueno (2002, 2003) highlight management based on rigid structures as contributing to turnover. More in particular they found that school leaders tended to focus on imposition, making it difficult for teachers to participate in decisions about the direction of teaching. In these conditions, the authorities do not value the work done by the teaching staff; they cause undue levels of competition, angry feelings, poor self-esteem and frustration in professionals, which, in long-term, means a loss of motivation, along with the breakdown of the bonds formed between them and the school. For their part, Gaete et al. (2017) refer to “job dissatisfaction”, which constitutes an essential point in teacher turnover.

The so-called cultural-ideological interests constitute a fourth category, referring to norms, values, and ideals that are recognized as legitimate within the school culture. In this context, González (2013) proposes this: some schools appreciate those teaching practices that, although they are part of the work at school, do not have a direct impact on student learning, thus transforming these practices into forms that are functional to the school dynamics. On the other end of the spectrum, opposition to bad practices triggers the decision of committed teachers to drop out from schools. In addition, Lapo and Bueno (2002) cited the presence of large workloads, excessive red- -tape, and unspoken requirements as causes of teacher drop-out, leading to a mismatch between the goals of teachers and managers. As a consequence teachers may develop an idealized representation of their job, which then is found to be very different from the reality in schools as well as their work lives.

Finally, we consider the social-professional interests, referred to as the quality of interpersonal relationships between school members. For example, Lapo and Bueno (2002, 2003) highlight interpersonal relationships as a neglected factor. In this sense, the relationships with principals, other teachers, and students are the sources of satisfaction or dissatisfaction at work and also determine teachers’ commitment in professional activities. From another edge, Souto (2016) identifies lack of discipline or interest in learning from the students as an influential factor in teachers’ decisions to leave the classroom.

An important thing to note is that all the papers reviewed documented that teacher turnover is a multi-dimensional, complex phenomenon for which no simple, one-dimensional causes can be given. While considering the limitations of any chosen perspective of analysis, we have opted for the micropolitical literacy lens to organize our findings and explain them in relation to power issues within the school, affecting the quality of the interpersonal interactions and relations, which eventually may become the cause for teacher turnover.

FUNCTIONAL ABANDONMENT OF TEACHING

Within the review, we found research that refers to a particular type of turnover, which exists without people physically leaving the establishment: the so-called “abandono funcional de la enseñanza” (functional teacher turnover) (GONZÁLEZ, 2013; PICH; SCHAEFFER; DE CARVALHO, 2013). Although strictly speaking, it would not be part of what we have considered teacher turnover; we believe it is relevant to incorporate it. Lapo and Bueno (2002) call this concept “acomodación” (accommodation).

In functional teacher turnover, educators are found to be physically fulfilling their professional duties, that is to say, they are present at the school, they meet and work with their students, but their commitment to the teaching-learning process is weak (PICH; SCHAEFFER; DE CARVALHO, 2013). In that case those teachers hold very low expectations in their educational practices and show a disinterest in students’ learning. Thus, they become administrators or distributors of educational supplies, an activity far removed from the notion of an educational professional (GONZÁLEZ, 2013; PICH; SCHAEFFER; DE CARVALHO, 2013).

In the case of functional teacher turnover, teachers carry out the administrative activities inherent to their work and are very willing to cooperate with institutional activities. As such the teacher seems to live up to a school community’s requirements and at the same time achieves his/her own satisfaction of expectations, which are recognized by the community. However, he or she is in no way committed to students’ learning performance (PICH; SCHAEFFER; DE CARVALHO, 2013).

According to González (2013), functional teacher turnover results from the low expectations the educational community holds in terms of teaching and learning. For instance, in Physical Education, the Principals think such discipline has as aim to expend the accumulated students’ energy and as such contributes to students being more relaxed or calm for the next few hours in class. As such the functional teacher turnover may operate as an effective way to deal with the dynamics in the school culture.

In short, such functional turnover results in teachers’ work being seen, valued and recognized by the school leaders, which eventually (and in a perverse way) creates a level of working comfort for the teachers. Teachers with functional turnover seem less tired, therefore, more willing to cooperate in school activities. They have more time to cope with red tape and to cooperate in the various institutional demands (FAVATTO; BOTH, 2019; GONZÁLEZ, 2013). Consequently, they are valued by the educational community (GONZÁLEZ, 2013).

DISCUSSION

As we pointed out at the beginning of this article, the aim of this work was to review the scientific literature published in Latin America on teacher turnover. One of the first findings is the scarcity of articles related to the subject. However, the texts studied allowed us to advance in the understanding of the phenomenon. Furthermore, we went on to compare our findings with the recent international literature, in order to compensate for the scarce literature. This allowed us to broaden the discussion by identifying new avenues for further research on this issue.

In Latin America, there is an embryonic development of the discussion on defining types of teacher turnover. The description that emerges from the review is rather general, except when it refers to a temporary turnover. In the international literature, a somewhat broader definition is being used. Thus, for example, we can see Ingersoll’s (2003) distinction between stayers (those who stay) and leavers (those who leave). The National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) adds the distinction of movers, who move from classrooms or schools. Freedman and Appleman (2009) add to the category of those who stay that of drifters. They are the ones who leave the classes but remain in teaching. There is also the “take a break”, that is, the temporary turnover. Finally, Olsen and Anderson (2007) propose three groups: (a) stayers (those who stay) (b) uncertain/uncertain (they still teach, but are not sure they want to stay), and (c) leavers (those who leave the classrooms).

The distinctions between types of teacher turnover make us reconsider the definition used. What are we discussing when we approach turnover? This is an important issue both for research and policy development. The chosen approach leads to an understanding of causes and implications coherent with that option. In line with the findings of our review, we may understand teacher turnover as those teachers who walk out of the classroom. In sense, those of us who leave school to become teacher educators at a university level, are we also part of said turnover? (CLANDININ; DOWNEY; SCHAEFER, 2014). On the other hand, a question that remains to be answered in the literature is how to name those who graduated as teachers but never get to work as such, how to speak of turnover if they have never started their career in the classroom? How to name them? (KELCHTERMANS, 2017). As we move forward in the organization of information, it seems that the doors are opening to more questions than answers.

When analyzing the different ways in which teacher turnover has been studied, we note the dominance of an individual approach to this phenomenon. Although there is some research that unravels both the conditions for leaving and for returning to the classroom (ÁVALOS; VALENZUELA, 2016; GAETE et al., 2017; PEREIRA; OLIVEIRA, 2018), it is still rarely considered in terms of an interactive process between individual and the school context. This dominant view has a strong impact, as it stresses the fact that teachers are ‘quitters’, who give up and drop out, without -however- ever critically questioning how the system has failed the teachers and/or triggered their leaving. So the implicit burden remains on the teachers’ shoulder: it is their individual responsibility to be able/capable/committed to stay. Although some articles indicate the conditions necessary for teachers to be able to stay committed and effective, the dominant connotation with teachers leaving remains to be very negative. As a matter of fact, maybe the very concept of “teacher turnover” needs thorough rethinking.

An example of this is when the conditions for returning to the school classroom are raised. The questions raised are: Do we want these teachers to return? Why do they need to come back? What makes us want, as researchers, that these teachers return to the classroom? Alongside those concerns, we pose the legitimate question for teachers, like any other professional, to seek other possibilities for potential growth. This point might be controversial; however, some research suggests that teaching work is part of teachers’ lives (SCHAEFER; LONG; CLANDININ, 2012; SMITH; ULVIK, 2017). In a world where there is high labor mobility, it may be essential to consider this approach as much in research, public policy development and teacher training.

Following the analysis on the causes of turnover, we decided to investigate the findings from an interactionist point of view, and more in particular drew on the different categories of professional interests as developed in the micro-political perspective (KELCHTERMANS, 2017). This kind of analysis provided us with a comprehensive framework to broaden the discussion on teacher turnover to include the various interests at play in schools (self-interests, material interests, organizational interests, cultural-ideological interests, social-professional interests).

Analyzing selected texts, alongside with a discussion of international literature, provides us with an insight into teacher turnover, immediately after initial training. For instance, Rots, Kelchtermans, and Aelterman (2012) propose that Education departments should consider confronting future teachers with working conditions closer to those they will have upon graduation. These articles, in a way, stress how critical it is to emphasize aspects that are often considered “less--technical”. It coincides with what is proposed by Silva-Peña et al. (2019), calling for the development of micropolitical literacy in initial teacher training. In other words, initial teacher training should explicitly consider those aspects that are part of developing relationships within schools.

Also, the reviewed articles coincide with the investigations in other latitudes. For example, in the case of a study in the United States, the research concludes that relationships developed within schools are more important than financial issues (NEWBERRY; ALLSOP, 2017). However, it does not mean that educational policies should lose their focus on improving salaries. Nevertheless, it should be born in mind that teacher turnover occurs, even when there is job and economic stability (CLANDININ; DOWNEY; SCHAEFER, 2014; SCHAEFER; LONG; CLANDININ, 2012). In addition, we need to pay attention to the health of the teaching collective from public policies. As stated by Yinon and Orland-Barak (2017), the issue is related to salutogenesis, that is, to cease wondering why teachers get ill, moving towards a reconsideration of how we can maintain a healthy teaching community within schools settings.

Along with the afore mentioned, we agree with Gallant and Riley (2017). They raise the existence of a disconnection between theoretical and practical aspects as well as the policies executed with regard of teacher turnover. In Latin America this research work needs to be strengthened by expanding the problem.

The critical point is to reflect on the support given to beginning teachers. Kelchtermans (2019) proposes to go beyond the issue of mentoring. He proposes to change the way we look at those who start teaching. Many mentoring programs are seen as remedial, framing recent graduates from a deficit perspective, as people who still lack necessary professional skills that need to be remediated. Changing the viewpoint means seeing these professionals as change agents, who would make the school context more dynamic. From this point of view, if we want to address teacher turnover, it is important to review the concepts behind the mentoring proposals.

Considering it as the loss of investment in the training process implies leaving aside an analytical model that views these teachers as people in the making (as we all are). We believe it is convenient to consider turnover and retention in the context of a broad teaching career. Here, the concept of teachers’ work lives helps us to broaden the criteria for analysis (KELCHTERMANS, 2009; KELCHTERMANS, HAMILTON, 2004).

We subscribe of an understanding on this phenomenon as part of a teacher training process which starts long before university entry and the turnover of the classroom is part of that process. It seems that there were previous elements that gave rise to such turnover and it would not be a one-off event. This vision, which has been developed in different countries (KELCHTERMANS, 2017; SCHAEFER; LONG; CLANDININ, 2012), is vital to adopt for future analysis of teacher turnover. This new perspective on turnover research also incorporates the processes of motivation and de-motivation existing in initial training. So far, an understanding of the turnover process as a “practice shock” has been developed, but it remains to be seen whether there are aspects of training or practice in training that could help to take the decision to leave the job. Even if this option is taken after the graduation process.

In short, the phenomena referred to as teacher turnover is addressed as an individual process through public policy. Thus, policies are proposed regarding retention, rather than accompanying or sustaining continuous teacher professional development processes. Also, in this line we find the possibilities of rethinking the processes of initial training in order to detect the existence a priori of these “ideas of turnover”. Processes such as demotivation for teaching during the professional practice are extremely worrying, with little research addressing them. Research is also incorporated here about the expectations that Pedagogy students have to know if they can adjust to the reality that they will have to face. Investigating this topic also allows knowing whether future teachers have the necessary skills to face the professional reality. Furthermore, we think that the concept of “turnover”, at least from the research reviewed, could be seen as a legitimate search to which all of us are entitled. From this discussion, new questions are born, new investigative paths that can be addressed in future research.

texto em

texto em