Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educar em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0104-4060versão On-line ISSN 1984-0411

Educ. Rev. vol.39 Curitiba 2023 Epub 06-Set-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-0411.87258

Dossier: Migratory processes and the history of education from a transnational perspective

Piccolo Mondo by Fanny Romagnoli and Silvia Albertoni: a study on production, circulation, materiality and content (1901-1938)

*Universidade Federal de São Paulo, UNIFESP, Guarulhos, São Paulo, Brasil. E-mail: claudia.panizzolo@unifesp.br

Between the last two decades of the 19th century and the first three of the 20th, it is possible to find signs of distribution and circulation of Italian books among immigrants and their descendants. This article aims to understand the production and circulation of reading books by Fanny Romagnoli and Silvia Albertoni, authors of Piccolo Mondo, approved to be adopted in elementary schools on the Peninsula and in Italian schools in Brazil at the beginning of the 20th century, and then analyze one of the volumes, the Sillabario, intended for first-class use. Anchored in the contributions of the History of Education and Cultural History and having the documental analysis as the adopted procedure, the present text takes as a privileged source the Piccolo Mondo reading book, in addition to Ministerial Circulars, a biobibliographic dictionary and newspapers. It also operates with the transnational category as a methodological approach in the History of Education. Books are considered cultural artifacts that are situated in the articulation between the prescriptions imposed by official programs and the unique discourses of teachers. For the process of internalizing the idea of the Italian Nation, a political-pedagogical project capable of bringing together the notions of nation, state and moral education in a single virtuous process was necessary. It can be said that Piccolo Mondo joined the project of creating a “new man”, a citizen of a Nation capable of leading the Nation to the conquest of modernity.

Keywords : Reading books; Piccolo Mondo; Elementary school; Reading; Civilized

Entre as últimas duas décadas do século XIX e as três primeiras do XX é possível encontrar indícios de distribuição e circulação de livros italianos entre os imigrantes e seus descendentes. Este artigo objetiva compreender a produção e a circulação dos livros de leitura de Fanny Romagnoli e Silvia Albertoni, autoras de Piccolo Mondo, aprovados para serem adotados nas escolas elementares da Península e escolas italianas no Brasil no início do século XX e, em seguida, analisar um dos volumes, o Sillabario, destinado ao uso da primeira classe. Ancorado nas contribuições da História da Educação e na História Cultural e tendo a análise documental como procedimento adotado, o presente texto toma como fonte privilegiada os livros de leitura Piccolo Mondo, além de circulares ministeriais, dicionário biobibliográfico e jornais. Opera ainda com a categoria transnacional como uma abordagem metodológica na História da Educação. Os livros são considerados artefatos culturais que se situam na articulação entre as prescrições impostas pelos programas oficiais e os discursos singulares dos professores. Para o processo de internalização da ideia de nação italiana se fez necessário um projeto político-pedagógico capaz de reunir as noções de nação, Estado e educação moral em um único processo virtuoso. Pode-se afirmar que Piccolo Mondo aderiu ao projeto de criar um “homem novo”, cidadão de um Estado capaz de conduzir a nação à conquista da modernidade.

Palavras-chave: Livros De Leitura; Piccolo Mondo; Escola Elementar; Leitura; Civilizado

Introduction

Between the last two decades of the 19th century and the first three decades of the 20th century, it is possible to find evidences of the distribution and circulation of Italian books among immigrants and their descendants. The productions of Barausse (2021; 2018; 2016); Luchese (2022; 2021; 2019; 2017), Panizzolo (2022; 2021; 2019; 2018; 2016) and Teixeira (2018; 2016) inform that the Syllabuses, the Books of Reading, Religion, Arithmetic, Homeland History, Geography, Songs, literary excerpts, among others that followed the current curricular program in Italy, were produced and authorized to be adopted in elementary schools in the Italian Peninsula, and sent as subsidy for Italian schools in Brazil.

This article aims to understand the production and circulation of books by Fanny Romagnoli and Silvia Albertoni, authors of the book series Piccolo Mondo, letture per le scuole elementari, approved to be adopted in elementary schools on the Peninsula and Italian schools in Brazil at the beginning of the 20th century, and then analyze one of the volumes, the Sillabario, a book intended for the use of the first class, for teaching reading and writing.

The reading book Piccolo Mondo, letture per le scuole elementari, especially the Sillabario, are taken as a privileged source, in addition to Ministerial Circulars, biobibliographic dictionary and newspapers.

The spelling book, the reading book, the textbook, the school book (terminology that changes over time and due to the material structure itself) are understood as privileged sources for the History of Education, as they are in the intersection between the prescriptions imposed by the official programs and the singular discourses made by teachers (CHOPPIN, 2002). It is presented by Chiosso (2011) as a precious document from the school of the past, capable of associating moral norms and notions of everyday life with the teaching of the alphabet; to provide information about school life, educational practices and childhood feelings.

In this sense, reading books can be taken as cultural artifacts that produce sense and meaning, as cultural tools that establish senses and meanings between mental structures and social figurations or, in the words of Elias (1994), between psychogenesis and sociogenesis. The theory of the civilizing process, expression created by Elias (2006) points to the joint development of the psychic apparatus and the chains of relationships constituted by individuals in society, therefore the models, in the civilizing process, can only be assumed within the concrete dynamics of each historical time.

Civilized is, for Elias (1994), the individual whose behavior has been transformed, molded, conditioned to acquire new behaviors, new habits, which are incorporated as a second nature. Chartier (2004) collaborates to understand that civilizing also took place through a process of symbolic production, through the edition and circulation of books, which, through reading, favored its being put into action, based on a corporate matrix, a set of provisions aimed at imitation and learning. Such readings intended to teach the elementary knowledge of reading, counting and writing, at the same time disciplining conducts and making their readers civilized.

It should also be clarified that the analysis carried out in this article is anchored in the fertile dialogue between Cultural History (CHARTIER, 1994; 1996; 1998; 2004) and the History of Education (CHOPPIN, 2002; CHIOSSO, 2011). It also takes the transnational category as a methodological approach in the History of Education, considering that some global elements help in understanding the issue of production and circulation of reading books on both sides of the Atlantic.

This article questions about the conditions of approval and circulation of the series Piccolo Mondo, letture per le scuole elementari in the Peninsula and in Brazil and, specifically regarding the Sillabario, its structure, its contents, methodological perspective and the way it operates with the elementary knowledge of reading and writing and the rules of conduct.

The text is organized into two sections: the first one searches to understand the place of reading books in the Italian political-pedagogical project at the beginning of the 20th century, as well as the approval and circulation of the series Piccolo Mondo, letture per le scuole elementari in Italy and in Brazil; in the second, a study is developed on the materiality and contents of the studied books, with a view to knowing the educational proposal, as well as the values prescribed therein.

The production and circulation of books by Fanny Romagnoli and Silvia Albertoni on both sides of the Atlantic

In 1901, almost a quarter of a century after primary education had become compulsory, literacy rates were still worrying in the Italian Peninsula, especially when comparing the various regions with each other and with the countries of Europe, according to Chiosso (2011, p. 59).

[…] half of the inhabitants of the Kingdom were illiterate. Strong imbalances persisted between the various regions of the country: compared to 32% of illiterates in the north, 52% were illiterate in the center and up to 70% in the south. At the beginning of the 20th century, the illiterate in England were only 3% of the adult population, the French were 5% and the Belgians about 12%.

It was urgent to teach literacy to the population, enroll children in schools, open night courses for young people and adults, rural schools, therefore, the role that education had to play in “making Italians” was undeniable - in reference to Massimo D’Azeglio’s famous statement, in reference to the Risorgimento, for whom Italy was made - and at that moment it was necessary, therefore, to make the Italians. According to Chiosso (2011, p. 61):

The realization that there were no Italians was equivalent to thinking of Italy as a nation without a people, a nation that was legitimized by a series of historical, geographic and linguistic factors, but, to be truly such, it lacked an adequate collective subject. Hence the conviction that national unification needed effective fusion and that it was therefore necessary to proceed a posteriori with extreme urgency. What needed to be done, in other words, was precisely the Italy understood as a national political unit, as a modern State, as a liberal and modern society.

It became necessary to expand the social base, convincing new groups that had not yet been included, at the same time that it was necessary to regenerate the “Italian populations to free them from inertia, indifference and ignorance” (CHIOSSO, 2011, p. 61) and “frame them within the values of the Nation” (CHIOSSO, 2011, p. 61), conceived as the will of each one, as the personal conscience, that is, a great collective moral principle, for what was needed, in the words of Chiosso (2011, p. 66) to the quote F. Gaeta in Dalla nazionallità al nazionalismo (From nationality to nationalism):

[...] mobilize public opinion, instill ideals of activity and sacrifice, spread the idea that to be a nation a language, a tradition, a common geographical area was not enough, but a common will was needed that was not the Rousseau’s ‘initial convention’ nor a result of nature, but a continuous and incessant diligence.

For the process of internalizing the idea of Nation, a political-pedagogical project capable of bringing together the notions of Nation, State and moral education in a single virtuous process was necessary. An essential condition was to create the “new man”, a new Italian, citizen of a State capable of leading the nation to the conquest of modernity and, for that, it was urgent to abandon the uncertain morality, the prevalence of individual interests, inheritance of centuries of conformism, dogmatism and skepticism. Education, teachers and books had an important role to play in this regard.

The reading book, in most cases, was the only book used in primary school, sometimes accompanied by the arithmetic book. According to Chiosso (2011), it was a book often compiled or written by teachers and school inspectors, with rather classic typographic characteristics, at least until the beginning of the 20th century, and sold at low cost, which made it very accessible. Grammar, History, Geography, Natural Sciences, Rights and Duties books were adopted from the fourth grade, attended by a minority of students who continued beyond the three years of compulsory schooling. The reading book was intended for the elementary course (primary school) organized into two sections, the lower one comprising the 1st, 2nd and 3rd grades, and the upper ones, the 4th and 5th grades.

One of the many books produced in Italy is the graded series Piccolo Mondo, letture per le scuole elementari, for girls and boys. In studies carried out by Panizzolo (2019; 2018; 2016) she states that the series is composed of the Sillabario, Complementary book to the Sillabario, Reading book for the second grade, Reading book for the third grade, Reading book for the fourth grade, Reading book for the fifth grade, by Fanny Romagnoli, a teacher who is a member of the Bolognese Teachers’ Society, and Silvia Albertoni (no information about the author has yet been found), published by the important publishing house Florentine Bemporad, which, alongside Editora Mondadori, held the greater number of books approved by the Ministry (GALFRÉ, 2005).

Piccolo Mondo, letture per le scuole elementari has been approved to be adopted in schools on the Italian peninsula and in Italian schools abroad. Barausse (2008), in his work Il libro per la scuola dall’Unità al fascism; la normativa sui libri di testo dalla legge Casati alla Riforma Gentile -1861-1922 (The book for the school from Unification to Fascism; the normative on the textbooks of the Casati Law to the Gentile Reform - 1861-1922), offers a wide and detailed repertoire of ministerial circulars and lists of approved books. It contains Ministerial Circular n. 74, of September 3, 1898, which approved the book by Fanny Romagnoli entitled In alto i cuori - letture per le giovinette raccolte e ordinate, from 1898 (Lift the hearts, selected and organized readings for young people), authorized for domestic readings, to make up the collection of school libraries and to be offered as a prize in schools. Ministerial Circular no. 68 of October 3, 1899 reiterates the previous approval.

The Ministerial Circular of April 30, 1900 authorizes again the use of In alto i cuori - letture per le giovinette raccolte e ordinate and includes Piccolo mondo, letture per le scuole elementari (Little World, readings for elementary schools), the Sillabario for the first class, the Complementary Book to the Sillabario, in addition to the books for the second and third classes.

Ministerial Circular no. 18 of March 1, 1905 includes approval for specific provinces, as seen in Chart 1:

CHART 1 Approval of the books Piccolo Mondo, letture per le scuole elementari by Fanny Romagnoli and Silvia Albertoni for the Italian provinces.

| Books | Piccolo Mondo Sillabario | Piccolo Mondo Compimento al Sillabario | Piccolo Mondo 2ª classe | Piccolo Mondo 3ª classe | Piccolo Mondo 4ª classe | Piccolo Mondo 5ª classe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paese | ||||||

| Ancona | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Arezzo | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Ascoli-Piceno | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Catania | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Como | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Firenze | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Genova | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Palermo | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Parma | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Pisa | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Reggio Calabria | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Chieti | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Venezia | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Caserta | x | x | x | x | ||

| Lecce | x | x | x | x | ||

| Cuneo | x | x | x | |||

| Massa- Carrara | x | x | ||||

| Siracusa | x | x | ||||

| Cremona | x | |||||

SOURCE: Table constructed by the author based on Barause (2008).

Although I could not find information about the year of the first edition of each of the books and about their circulation, there is some information on their covers about the number of copies produced at the time of that edition, giving clues about their circulation, as shown in chart 2.

CHART 2 Circulation of the graded series Piccolo Mondo, letture per le scuole elementari.

| Book | Year of the studied edition | Number of copies produced |

|---|---|---|

| Sillabario | 1908 | 220 thousand |

| Compimento al Sillabario | 1907 | 155 thousand |

| Piccolo Mondo- Per la 2ª classe | 1901 | copy without cover |

| Piccolo Mondo- Per la 3ª classe | 1906 | 125 thousand |

| Piccolo Mondo- Per la 4ª classe | 1910 | The information is not included |

| Piccolo Mondo- Per la 5ª classe | 1912 | The information is not included |

SOURCE: Constructed by the author based on Romagnoli e Albertoni (1908; 1907; 1901; 1906; 1910; 1912).

The lack of information on the covers of books for the fourth and fifth grades may have occurred due to the probable decrease in the number of students who reached these grades, which, consequently, impacted the demand for books, and the editors decided not to disclose the possible small number of copies in circulation, in the same way, but in the very initial of schooling, one can understand the largest number of copies in circulation of the Sillabario, a book intended for language learning in the first grade of elementary school, with a greater intake of students, who, with the passage of school grades, motivated by repetition and evasion, is quantitatively decreasing.

Piccolo Mondo, letture per le scuole elementari crossed the Ocean and arrived in Brazilian lands. According to Teixeira (2018), the books circulated in the brazilian city of Juiz de Fora (Minas Gerais state). According to the author, in 1894, a request was made from teacher Amalia di Battisti, from the Regina Margherita School, to the vice-consul, for the receipt of textbooks. At first, the solution found was the donation by the immigrants themselves and “about 190 copies of books, plus a few hundred notebooks were collected and divided between the Umberto Primo and Regina Margherita schools” (TEIXEIRA, 2018, p. 237). All books were published in Italy, with emphasis on Ida Baccini and Pietro Dazzi, authors of several reading books adopted by Italian schools. Between 1899 and 1919, the author states that subsidies were sent “without any regularity and depended on the availability and goodwill of the vice-consuls” (TEIXEIRA, 2018, p. 239).

On October the 1st, 1906, the Regina Margherita’s school received 4 copies of Piccolo Mondo for 2nd grade; 4 copies of Piccolo Mondo for 3rd class; 2 copies of Geografia e Storia (Geography and History) for 3rd grade (without identification of authorship); plus 2 copies of Geografia, Storia e doveri (Geography, History and duties for 3rd grade. On the 13rd December 1906, another shipment containing books by Pietro Dazzi: 11 Sillabario and First Reading Book, 13 Books for 1st Class - Part 1, 29 Books for 1st Class - Part 2, 7 Books for 2nd Class, and 9 books for 3rd grade; 8 books Primmi Elementi di Geografia (First Elements of Geography), by Silvio Pacini; 12 books L’Aritmetica (The Arithmetic), by Giuseppe Baldasseroni; 10 books Abaco ed Aritmetica (10 books Abacus and Arithmetic), by Nazzareno Dati; 29 books Grammatichetta Italiana (29 books Small Italian Grammar), by Lirilli and Curradini; 13 books Calcolo mentale e scritto (13 books Mental and written calculation), by Cerrado Ciamberlini; 42 books Il Risorgimento Nazionale (42 books The National Risorgimento), by Luigi Neretti; 12 books Manuale Atlante di Geografia e Storia (12 books Manual Atlas of Geography and History), by Gianni Trapani; in addition to Piccolo Mondo books: 6 books for 2nd grade and 6 books for 3rd grade.

There are also indications of the adoption of the book Piccolo Mondo for 4th grade by the Italo-Brazilian School Principe di Napoli, from Associazione di Mutuo Socorso (Mutual Aid Association) from São Caetano in the state of São Paulo, during the 1920s, a period in which Giovvani Cardo was the teacher. No records were found about the foundation of the school, curriculum structure, organization of times and spaces, methods and material culture. Only this book preserved in the Collection of the Historical Museum of São Caetano do Sul city. It is not known whether the book was a donation from the teacher himself to work with children or, as in Juiz de For a city, a donation from immigrant families, or even sent by the Italian government. But it appears among the documents of the school.

According to Barausse (2018), in the didactic plans of the Italian schools in Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre adopted in the 1920s, which are under the care of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Italy, there was the presence of Piccolo Mondo, letture per le scuole elementari even though it is not possible to specify the edition and to which class it was intended.

In addition to circulating in Italian, Piccolo Mondo circulated also in Portuguese. In the edition number 216, dated September 15, 1908, there was news about the Portuguese version of the book, which was renamed Mundo Infantil, as read below:

The editors, our friends Souza & Barros, were kind enough to send the Federation a copy of the Italian book Mundo Infantil, an original Italian by Fanny Romagnoli and Sylvia Albertoni and translated by Mr. J.F. Lima Cortes. Mundo Infantil, intended as its title implies for primary school, was approved by the Public Instruction Council of the State last year.

The style of the whole carefully translated book is light; the stories are interesting, short and fulfill the purposes for which they are intended: to instruct, delighting childhood (A FEDERAÇÃO, 09/15/1908, p. 2).

The translator, João Fernandes de Lima Cortes, attended the Faculty of Law in Recife until the fourth year, having, however, abandoned the course. He taught Latin, Portuguese and French in renowned schools, such as Colégio Pedro II and Colégio Abílio, both in Rio de Janeiro state, in addition to teaching many individual and private classes. He also exercised the function of district judge in Garibaldi, in Rio Grande do Sul state, and published the following works: Modo de medir as Odes de Horacio (Mode of measuring the Odes of Horacio), in 1879; Resumo da Grammatica portuguesa (Summary of Portuguese Grammatica), in 1888; and translated from Latin into Portuguese: Lelio ou Tratado sobre amizade (Lelio or Treatise on Friendship) by M. F. Cicero, in 1888; Discurso de Cicero em favor de M. Marcello ( Cicero’s Speech in favor of M. Marcello), in 1905, and, from Italian, Piccolo Mondo, which was translated as Mundo Infantil, in 1907. The book was not found and there is no information about which class the translation had been intended for (GUARANÁ, 1925; O BRASIL, 03/13/1909; TAMBARA, 2003).

With regard to Casa Editora Souza & Barros, founded in 1895, it was owned by lieutenant colonel Luiz Manoel de Souza Filho and João Rodrigues de Barros. The owners, in addition to the publishing house, had a bookshop (no information is available on when it opened) which operated in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul (brazilian state) until 1928, when the publishing house closed (A FEDERAÇÃO, 11/07/ 1928).

In 1938 there was an article in the newspaper A Comarca, from Mogy-Mirin city (in São Paulo state), about books for sale at Casa Cardona. Among the announced books are spelling book, reading books and graded series books that achieved significant circulation1 in Lthe first decades of the 20th century, such as those by João Köpke (First, Second, Third and Fourth Reading Books); Puiggari-Barreto (First and Second Reading Books); Antonio Firmino de Proença (Cartilha Proença; Primeiro Livro de Leitura e Leitura para Principiante -Proença Spelling Book; First Reading Book and Readings for Beginners); Thomaz Galhardo (Cartilha da Infância e Terceiro Livro de Leitura - Childhood Booklet and Third Reading Book); Erasmo Braga (First, Second, Third Reading Books); Mariano de Oliveira (Páginas Infantis, Nova Cartilha - Children’s Pages, New Spelling Book); Rita M. Barreto (Coração de crianças, Leituras preparatórias, Primeiro, Segundo e Terceiro Livros de Leitura - Children’s Heart, Preparatory Readings, First, Second and Third Reading Books). Alongside these renowned books, Fanny Romagnoli and Silvia Albertoni appear with two indications, the first consisting only of Piccolo Mondo, and the second with the information that it was the Second Reading Book) (A COMARCA, 07/28/1938).

The book was not located, which does not allow to say whether the edition was in Italian, or whether the editorial option was to abandon the Mundo Infantil version, and keep the title in Italian and the translated content, in order to link to the book the recognition already achieved in Italy. In any case, being among important reading books, which were on the wallets of Brazilian children for decades, (con)forming the Brazilian citizen, teaching to read and write from a certain standard of conduct and values is an indication of the notoriety that Piccolo Mondo achieved.

In the next section, a study will be developed on one of the books in the series published by the authors, the Sillabario.

Sillabario per la prima classe

The Sillabario taken as the object of study in this article dates from 1908. It follows the same visual structure as the other books in the series, does not indicate whether it is for boys or girls, and is made up of 72 pages, with illustrations for each new lesson.

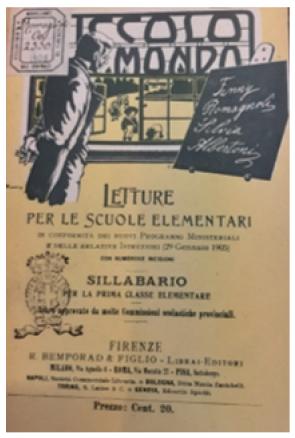

The cover (see Figure 1) contains the title of the book, the names of the authors Fanny Romagnoli and Silvia Albertoni; information about the publication complies with the Ministerial Programs and Instructions of January 29, 1905, a requirement imposed on publishing houses by ministerial circulars; just below the indication of the publishing house, R. Bemporad & Figli - booksellers and publishers, located in Firenze - Italy. At the top of the title there is an indication of 220,000 which probably indicates the number of copies published. The title page then reiterates all the same elements and informs that the book has been approved by many provincial school boards (the equivalent of states).

Information about the published copies and the various approvals is important for deciphering the book. As stated by Chartier (1998), “The book has always aimed to establish an order; whether it was the order in which it was deciphered, the order within which it must be understood, or even the order desired by the authority that commissioned or permitted its publication” (p. 8). This order is clearly evidenced by the editor, when attributing notoriety and authority to the authors and relevance to the Sillabario due to its expressive approval and circulation.

On the back of the title page, there is an indication of 1908 as the year of publication and information from the Typography by Vittorio Sieni, located at 26, Corso de Tintori, - Firenze - Italy, as the place where the book was printed.

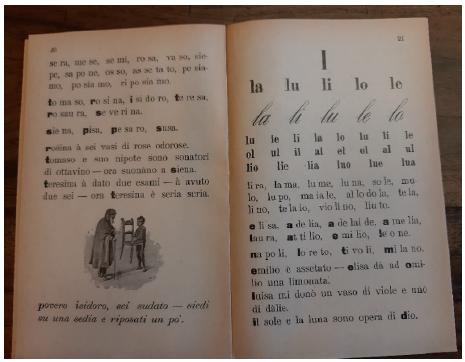

The Sillabario, indicated to be the first book of the first class of the elementary course, introduces future readers to the literate world through the presentation of the vowels, “i, u, e, o, a” and, in the sequence, the vowels beginning with “ i” and with “u”. All letters are presented in printed and cursive, as shown in Figure 2.

The authors pay attention to the presentation of the letters. The displayed sequence is: n, t, m, r, p, v, d, s, l, b, c, z, f, g, h, q; followed by the consonant clusters gh, gn, gl. The first “lesson” is that of “n” containing the letter to be taught in block letters, its syllable family in block letters and italics, words with this letter at the beginning, middle or end, always in block letters, in addition to a few short phrases, whose syllables are sometimes separated, sometimes united. The lesson is accompanied by an illustrative image of what is presented throughout the “lesson”. The writing of all the words is always separated by syllables, which leads us to the hypothesis, still to be investigated that, when reading in this paused way, the reader is incentivated to do it clearly and to pronounce all the words. Letters, which, for the teaching of the Italian language, is very important, especially in the case of “double” letters, as in Anna, taught in the sillabario as “an na”. It would therefore be a strategy of the authors and/or the editor, called by Chartier (1996) panoply of narratives, which would work as “a machinery should produce obligatory effects, guaranteeing good reading” (p. 96).

Another highlight of the “lesson” is the use of bold in several letters, mainly, but not exclusively, in the letter “n” that is being taught, but always in the first letter of the word, as seen in Figure 3.

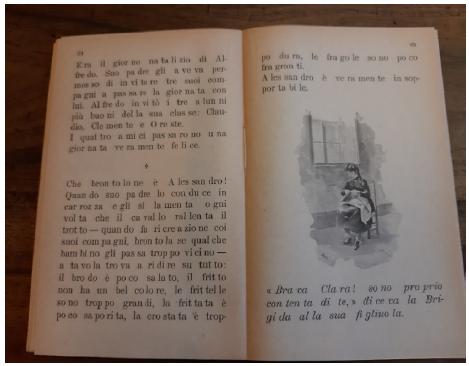

In the lessons referring to the letters “n” and “q”, the structure remains the same, expanding, however, the size and amount of reading. Apparently, the authors start from the assumption that, knowing more letters, syllables and words, the children’s repertoire will be expanded, making them, therefore, capable of intensifying their dedication to reading. Thus, while in the first lessons there were 2 to 4 short sentences of one or two lines, from lesson “1” onwards, in addition to sentences, very short stories are presented, but with a connection between the sentences, as seen in the Figure 4.

After the “q” lesson, the Sillabario assumes a structure more similar to that of a reading book, rarer the presentation of syllables and words by comic strips, but preserving the illustrations, as seen in Figure 5.

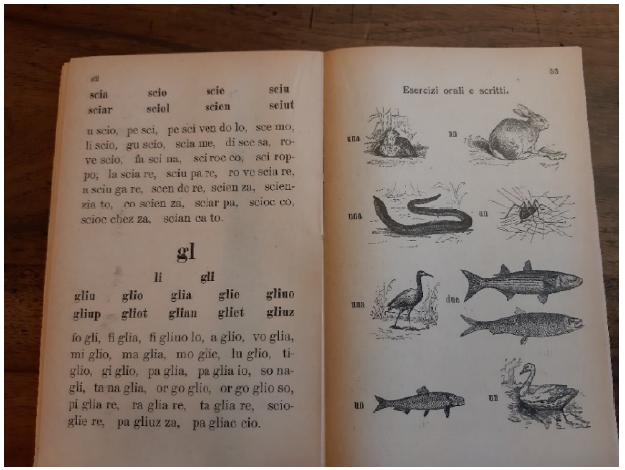

Romagnoli and Albertoni (1908) insert ten exercises called Esercizi orali e scritti (Oral and written exercises) throughout the Sillabario, prescribing in this way, even without presenting a manual to the teachers, the way they should conduct them. All exercises present grammatical elements to be taught, such as masculine and feminine, singular and plural, and definite and indefinite articles, as seen in Figure 6. With regard to the images, it is worth asking: what would they represent to the children? Probably many were unaware of, for example, sharks, swans and herons, but, it seems, the authors’ concern was based on the grammatical issue of the proper use of singular and plural, to the detriment of an eventual distance from the universe of concrete knowledge of children.

By taking the Sillabario as a source, it is possible to approach the methodological principles present in its pages. In a first reading, it could be assumed an adherence to synthetic methods, which go from the parts to the whole, when taking into account the teaching of the letter, the syllable, the word. We refer to Frade (2005, p. 22) for the definition of the method:

[...] in synthetic methods, we have the election of differentiated organizational principles, which privilege phonographic correspondences. This trend comprises the alphabetic method, which takes the letter as a unit; the phonic method, which takes the phoneme as a unit; the syllabic method, which takes as a unit a more easily pronounced phonological segment, which is the syllable. The dispute over which unit of analysis to be considered - the letter, the phoneme or the syllable - is what set the tone for the differentiations around the phonographic correspondences. For this set of so-called synthetic methods, a distancing from the situation of use and meaning is proposed, in order to promote strategies for analyzing the writing system.

Among the synthetic methods, the oldest, widely used in European countries and in Brazil until the beginning of the 20th century, is the alphabetic method, which consists of presenting minimal parts of the writing, the letters of the alphabet, which, when joined together, they formed the syllables that would give rise to words. According to Frade (2005, p. 23) “learners, first, should memorize the alphabet, letter by letter, to find the parts that would form the syllable or another segment of the word” and only after a while would they come to understand that these syllables could be turned into a word. Another widely used characteristic was the spelling procedure, which generated exhausting “cantilena” exercises, it is a singing with the names of the letters and their combinations, and repetitive training with possible combinations of letters in syllabaries. The book written by Romagnoli and Albertoni, although it starts with letters, moves quickly from there to syllables, words and phrases. What is possible to apprehend, without a manual or guidance to teachers, is not the valorization of memorizing the alphabet, which, by the way, is not taught in its sequence; nor is it the use of chants of joining letters into syllables and syllabic and vowel combinations, which are shortly explored in the book.

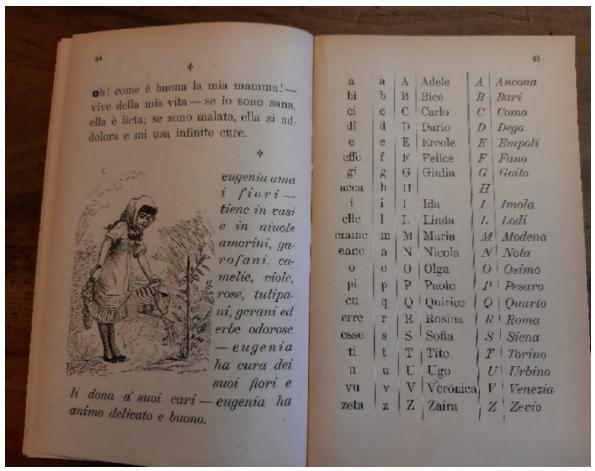

Approximately in the midle of the Sillabario, a full-page table is presented with the sequence of the letters of the alphabet, which differs from the structure adopted throughout the book. It consists of six columns, distributed as follows: the first four in letters printed, the initial one with the sounds of the letters; the second with lowercase letters and the third with uppercase letters; the fourth column with proper names beginning with those letters. The last two columns, in cursive, the fifth column with capital letters and the last column with names of Italian cities that begin with that letter, as seen in Figure 7.

Although this table refers us to the other synthetic method called Phonic, “whose principle is that, it is necessary to teach the relationships between sounds and letters, so that the spoken word is related to the written word” (FRADE, 2005, p. 25), making sound the minimum unit of analysis, I reiterate that, due to the absence of guidance to teachers about the Sillabario, which certainly limits the understanding of the protocols imposed for its adoption, it is possible to state that the authors’ proposal does not seem to have been based on in teaching sounds. One hypothesis is that this table was inserted as an exercise for training the sounds, at the same time as an opportunity to learn the use of lowercase and uppercase letters, the proper name and the sequence of the alphabet.

Another synthetic method is the Syllable, in which “the main unit to be analyzed by the students is the syllable” (FRADE, 2005, p. 27). Regarding this method, Frade (2005) states that the methods that follow the synthetic march, that is, those that start from the parts to the whole, often “tend to prioritize only the decoding, that is, the phonological analysis, with short emphasis on the meaning of texts and the social use of writing” (FRADE, 2005, p. 30), which does not seem to be the case of Sillabario, as will be discussed below.

Finally, the Sillabario presents some characteristics of the Synthetic Method, even though it values phrases and short stories. This article is not intended to classify the method adopted, also because such an analysis requires expanding issues that do not fit within what is proposed here, such as, for example, investigating in depth the political character of literacy, its context of application, the choice of the vocabulary universe, among other issues that give the method a much broader meaning, which goes beyond the choice of one principle or another.

Considering that “reading is not only an abstract operation of intellection; it is body engagement, inscription in a space, relationship with oneself and with others” (CHARTIER, 1998, p. 16-7), the study of Sillabario allows understanding how a reality is constructed and thought from the social representations determined by interests of the groups that create them and that, therefore, are not neutral, but, on the contrary, are driven by strategies that aim to legitimize their discourses. Chartier (1994, p. 104) defines them as a set of “[...] collective representations that incorporate in individuals the divisions of the social world and structure the schemes of perception and appreciation from which they classify, judge and act”.

Romagnoli and Albertoni teach reading and writing through letters, syllables, words, but also through short sentences and short stories, which clearly demonstrates the expectations placed on children. When analyzing them, the theme of the work stands out. Everyone works, adults and children, as the small text reads: “We are many in the family: father, mother and five children. The father works as a carpenter and the mother weaves the clothes. We are still small, we cannot work, but we take care of the clothes that our mother makes, so that they do not deteriorate in a short time” (ROMAGNOLI; ALBERTONI, 1908, p. 55).

It is recurrent the presence of children who work to contribute to the tasks of the family structure, with a sense of responsibility that practically drives them to work: “Adele is a poor widow and Laura is one of her nieces - Adele worked from morning to night - now Adele is sick and Laura has to work a lot” (ROMAGNOLI; ALBERTONI, 1908, p. 22).

Working is presented as the great expectation of life, that is, one lives to work, hard and always: “Beniamino is used to working from morning to night” (ROMAGNOLI; ALBERTONI, 1908, p. 23); “Now my parents work from morning to night - one day I’ll work in their place” (ROMAGNOLI; ALBERTONI, 1908, p. 35).

The children also perform work that is presented as personal and compatible with childhood, invariably related to the demands of the house or manual knowledge, as is the case of Pierina: “[...] she is ten years old and sews very well - tomorrow will be the Christmas day of one of her aunts and Pierina will give her a little job done by her” (ROMAGNOLI; ALBERTONI, 1908, p. 42); from Clara: “how daddy will be happy when he sees the finished shirt! it was the first time that Clara did a difficult job on her own - she had to undo it many times, but by dint of reflecting and trying, she succeeded” (ROMAGNOLI; ALBERTONI, 1908, p. 66); and Eugenia, who “[...] loves flowers - she keeps angelica, carnations, camellias, violets, roses, tulips, roses and aromatic herbs in vases and flowerbeds - Eugenia takes care of her flowers and gives them to her loved ones - Eugenia has a delicate and good soul” (ROMAGNOLI; ALBERTONI, 1908, p. 44). Eugênia is one of many children who, in addition to being hardworking, have virtues, such as being delicate, generous, obedient, diligent, resilient, etc.:

Nina and Luisa are sisters. Nina is still young, but very sensible. When the mother dresses the baby, Nina hands her the shoes or the dress - when the mother has to stay in the kitchen, Nina takes care of Luisa, entertains her and keeps her away from any danger. Nina already knows how to dust the lower furniture and knows how to use her broom. What a woman! (ROMAGNOLI; ALBERTONI, 1908, p. 60-61).

In order to understand the place that work and moral values occupy in the Sillabario, we turn to Chiosso (2011) in his book Alfabeti d’Italia; la lotta contro l’ignoranza nell’Italia Unita (Literates of Italy; the fight against ignorance in Unified Italy). According to Chiosso, (2011) the prototype of the reading book that circulated in the Peninsula in part of the 19th and 20th centuries was born with the publication of the book Giannetto2 , by Luigi Alessandro Parravicini, pedagogist, school director in Como and Venezia, winner of the work award original for the exercise of reading and moral instruction proposed by the Society of Firenze, in the year 1835, for the dissemination of the reciprocal teaching method. The model built from the Giannetto circulated for a long time in books aimed at children and aimed to.

The formation of a student who is aware of his duties, respectful and obedient, lover of study, aware of good and evil, capable of self-control of body, gestures, words, decent and clean, desirous of improving himself and his own condition of life (CHIOSSO, 2011, p. 301).

These same principles are found in Sillabario with the presence of what Chiosso (2011, p. 302) called the “shaping force of civil morality” and the “importance of work conceived as the access key to deserving life and improving one’s conditions”. The phrases and short stories can then be understood as “[...] direct instruments of conditioning or modeling, of adapting the individual to these modes of behavior, which the structure and situation of the society where he lives make necessary” (ELIAS, 1994, p. 95). Thus, most likely the authors intended to replace usual and shared behaviors with new ones; the former become wrong, blameworthy, uncivilized, and intolerable; these become expected and necessary, as they are correct, adequate and considered civilized. Borrowing from Elias (1994), the behaviors to be abandoned would be equivalent to “[...] a pattern of human relations and a structure of feeling” (ELIAS, 1994, p. 80); while the new behaviors to be acquired would correspond to another pattern of relationships, feelings and cognitive structure.

In this civility building process, obedience must be learned and apprehended through self-control, which disciplines the will. Leão (2007, p. 64) clarifies that the very act of reading can be considered “[...] a permanent exercise of self-control”. In this sense, learning to read the letters, syllables, words, phrases and comic strips of the Sillabario is part of a certain social learning process, that is the learning to control the emotions.

Final considerations

The reading books Piccolo Mondo, letture per le scuole elementari that were distributed to Italian schools in Brazil were books recently published in Italy. They were contained in a Ministerial Circular that authorized their use in schools on the Peninsula, were approved for adoption in various regions of Italy in the same period in which they were sent to Brazil, for distribution by the Consulate to schools in the cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre and Juiz de Fora. Although it is not yet known how this selection was made, what criteria were adopted, how the relationship between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the publishing houses took place, it can be safely stated that the book adopted on this side of the Atlantic was the even authorized to be adopted on the other side of the Ocean.

From Piccolo Mondo’s phrases and stories emerge rules of individual and collective conduct considered at the time the pillars of a ‘modern’ society, therefore the authors intended, instead of describing society, to transform it. In this sense, the vision of childhood and children is idyllic, of an obedient, generous, resilient and very hardworking child, revealing more the desired image than the true image of children.

People learned to read by reading a certain standard of conduct, by disciplining the children’s hearts and souls, trying to teach everyone a code of civility, by coercing the body and imposing norms of sociable behavior. The purpose of the books was to help the school carry out the important project assigned to it, after all, it was necessary to invent the Italian People in the Peninsula and beyond.

REFERENCES

A COMARCA, de Mogy- Mirin, 28/07/1938. [ Links ]

A FEDERAÇÃO, do Rio Grande do Sul, 11/07/1928. [ Links ]

A FEDERAÇÃO, do Rio Grande do Sul, 15/09/1908. [ Links ]

BARAUSSE, Alberto. Il libro per la scuola dall’unità al fascismo: la normativa sui libri di testo dalla legge Casati alla Riforma Gentile (1861- 1922). Macerata: Alfabetica Edizioni, 2008. (Fonti e documenti 2). [ Links ]

BARAUSSE, Alberto. Escolarização étnica italiana e cultura escolar em São Paulo: as iniciativas de Gaetano Nesi e Gemma Manetti pela infância escolar italiana entre o final do século XIX e o início do século XX. Revista Inter Ação, v. 46, n. 2, p. 422-440, 2021. Disponível em: https://revistas.ufg.br/interacao/article/view/67954. Acesso em 09 mar. 2023. [ Links ]

BARAUSSE, Alberto. Livros didáticos e italianidade no Brasil nos anos 1920-1930. In: LUCHESE, Terciane Ângela (Org.). Escolarização, culturas e instituições: escolas étnicas italianas em terras brasileiras. Caxias do Sul: Educs, 2018. p. 29-74. [ Links ]

BARAUSSE, Alberto. Os livros escolares como instrumentos para a promoção da identidade nacional italiana no Brasil durante os primeiros anos do fascismo (1922-1925). História da. Educação, v. 20, n. 49, p. 81-94, 2016. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/heduc/a/C6MKG7LSKkVzKjhNNrLBfWm/?lang=pt. Acesso em: 9 mar. 2023. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger (Org.). Práticas da leitura. São Paulo: Estação Liberdade, 1996. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A história hoje: dúvidas, desafios, propostas. Estudos Históricos, v. 7, n. 13, p. 97-113, 1994. Disponível em: https://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/ojs/index.php/reh/article/view/1973. Acesso em: 9 mar. 2023. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A ordem dos livros: leitores, autores e bibliotecas na Europa entre os séculos XIV e XVIII. 2. ed. Brasília: Ed. da Universidade de Brasília, 1998. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. Leituras e leitores na França do antigo regime. São Paulo: UNESP, 2004. [ Links ]

CHIOSSO, Giorgio. Alfabeti d’Italia: la lotta contro l’ignoranza nell’Italia unita. Torino: Società Editrice Internazionale, 2011. [ Links ]

CHOPPIN, Allain. O historiador e o livro escolar. História da Educação, v. 6, n. 11, p. 5-24, 2002. Disponível em: https://seer.ufrgs.br/asphe/article/view/30596. Acesso em: 9 mar. 2023. [ Links ]

ELIAS, Norbert. Escritos e ensaios. 1. Estado, processo, opinião pública. Tradução: Vera Ribeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Ed., 2006. [ Links ]

ELIAS, Norbert. O processo civilizador: uma história dos costumes. Tradução: Ruy Jungmann. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Ed., 1994. [ Links ]

FRADE, Isabel Cristina Alves da Silva. Métodos e didáticas de alfabetização: história, características e modos de fazer de professores. Belo Horizonte: Centro de alfabetização, leitura e escrita - Ceale: FAE/ UFMG, 2005. [ Links ]

GALFRÉ, Monica. Il regime degli editori: libri, scuola e fascismo. Roma: Editori Laterza, 2005. [ Links ]

GUARANÁ, Armindo. Dicionário Bio-bibliográfico sergipano. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Pongetti, 1925. [ Links ]

LEÃO, Andrea Borges. Norbert Elias & a educação. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2007. [ Links ]

LUCHESE, Terciane Ângela. “Libriccini com amore per l’infanzia”: Silabários escritos e impressos no Brasil para as escolas étnico-italianas (1906-1907). In: LUCHESE, Terciane Ângela et al (Orgs.). Migrações e história da educação: saberes, práticas e instituições, um olhar transnacional. Caxias do Sul: Educs, 2021. p.307-336. [ Links ]

LUCHESE, Terciane Ângela. Da Itália ao Brasil: Indícios da Produção, Circulação e Consumo de Livros de Leitura (1875-1945). História da Educação, v. 21, n. 51, p. 123-142, 2017. Disponível em: https://seer.ufrgs.br/index.php/asphe/article/view/68984. Acesso em: 9 mar. 2023. [ Links ]

LUCHESE, Terciane Ângela. ‘E não nos deixeis cair em tentação’: livros de leitura religiosa do governo fascista para as escolas italianas no Brasil (anos 20 e 30 do século XX). Cadernos de História da Educação, v. 18, n. 2, p. 368-385, 2019. Disponível em: https://seer.ufu.br/index.php/che/article/view/50289. Acesso em: 9 mar. 2023. [ Links ]

LUCHESE, Terciane Ângela. ‘Quando il Mondo era Roma’: livros escolares para fascistizar os italianos no exterior, o caso brasileiro (1922-1938). Cadernos de História da Educação, v. 21, p. 1-17, 2022. Disponível em: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362500697_’Quando_il_Mondo_era_Roma’_livros_escolares_para_fascistizar_os_italianos_no_exterior_o_caso_brasileiro_1922-1938. Acesso em: 9 mar. 2023. [ Links ]

MORTATTTI, Maria do Rosário Longo. Os sentidos da alfabetização: 1876-1994. São Paulo: Editora da UNESP, 2000. [ Links ]

O BRASIL, de Caxias, Rio Grande do Sul, 13/03/1909. [ Links ]

PANIZZOLO, Claudia. Italianizar os brasileirinhos, paulistanizar os italianinhos: um estudo sobre os livros de leitura que circularam nas escolas em São Paulo no início do século XX. In: Castro, C. A.; Castellanos, S. L.V. (Orgs.). História da escola: métodos, disciplinas, currículos e espaços de leitura. São Luís: EDFUMA, 2018. p. 100-125. [ Links ]

PANIZZOLO, Claudia. Livros de leitura e a construção da identidade nacional de crianças italianas e descendentes (São Paulo no início do século XX). Acta Scientiarum. Education v. 41, n. 1, p. 1-13, 2019. Disponível em: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/3033/303360435041/html/. Acesso em: 9 mar. 2023. [ Links ]

PANIZZOLO, Claudia. Livros escolares para a escola elementar italiana nos dois lados do Atlântico: o estudo do Libro d’appunti de Giovanni Soli (entre o final do século XIX e início do século XX). Cadernos de História da Educação, v. 21, p. 1-25, 2022. Disponível em: file:///C:/Users/claud/Downloads/120a+-+Claudia+Panizollo+-+Portugues+-+DIAGRAMADO%20(2).pdf. Acesso em: 9 mar. 2023. [ Links ]

PANIZZOLO, Claudia. Piccolo mondo letture per le scuole elementari: mutualismo e educação em uma escola étnica italiana em São Paulo In: MAZZA, D.; NORÕES, K. (Orgs.). Educação e migrações internas e internacionais: um diálogo necessário. Jundiaí: Paco Editorial, 2016. p. 80-100. [ Links ]

PANIZZOLO, Claudia. Scuole italiane all’estero: um estudo sobre os livros de leitura que circularam nas escolas étnico-italianas no Brasil (fins do século XIX e início do século XX). In: LUCHESE, Terciane Ângela et al. (Orgs.). Migrações e história da educação: saberes, práticas e instituições, um olhar transnacional. Caxias do Sul: Educs, 2021. p. 281-306. [ Links ]

PARRAVICINI, Luigi Alessandro. Giannetto. Napoli: Gaetano Nobile Libraio- Tipografo, 1841. [ Links ]

PFROMM NETO, Samuel; ROSAMILHA, Nelson; DIB, Claudio Zaki. O livro na educação. Rio de Janeiro: Primor/INL, 1974. [ Links ]

ROMAGNOLI, Fanny, ALBERTONI, Silvia. Piccolo mondo, letture per le scuole elementari. Compimento al Sillabario, per la I classe. Firenze: Bemporad, 1907. [ Links ]

ROMAGNOLI, Fanny, ALBERTONI, Silvia. Piccolo mondo, letture per le scuole elementari. Sillabario, per la I classe. Firenze : Bemporad, 1908. [ Links ]

ROMAGNOLI, Fanny, ALBERTONI, Silvia. Piccolo mondo, letture per le scuole elementari, per la II classe. Firenze: Bemporad, 1901. [ Links ]

ROMAGNOLI, Fanny, ALBERTONI, Silvia. Piccolo mondo, letture per le scuole elementari, per la III classe. Firenze: Bemporad, 1906. [ Links ]

ROMAGNOLI, Fanny, ALBERTONI, Silvia. Piccolo mondo, letture per le scuole elementari, per la IV classe. Firenze: Bemporad, 1910. [ Links ]

ROMAGNOLI, Fanny, ALBERTONI, Silvia. Piccolo mondo, letture per le scuole elementari, per la IV classe. Firenze: Bemporad, 1912. [ Links ]

TAMBARA, Elomar. Bosquejo de um ostensor do repertório de textos escolares utilizados no ensino primário e secundário no século XIX no Brasil. Pelotas: Seiva Publicações, 2003. [ Links ]

TEIXEIRA, Mariana Eliane. Ecos do nacionalismo: os sentidos da italianidade em Juiz de Fora (1878-1922). Tese (Doutorado em História) - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2016. Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufmg.br/handle/1843/BUBD-ABYDZB. Acesso em: 11 maio 2023. [ Links ]

TEIXEIRA, Mariana Eliane. Literatura e nacionalismo italiano nas escolas de imigrantes em Juiz de Fora - MG. In: ANHEZINI, Karina (Org.). Anais da XXI Semana de História: usos públicos e políticos da história ao papel do historiador. Franca: UNESP- FCHS, p. 233-250, 2018. [ Links ]

1Regarding the notoriety of these authors of reading books, see Mortatti (2000) and Pfromm Neto et al. (1974).

Received: August 15, 2022; Accepted: March 21, 2023

texto em

texto em