Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educar em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0104-4060versão On-line ISSN 1984-0411

Educ. Rev. vol.39 Curitiba 2023 Epub 06-Set-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-0411.86995

Dossier: Migratory processes and the history of education from a transnational perspective

The Castillo Method on the pages of the “Revista da Instrução Pública para Portugal e Brasil” (1857-1858)

*Universidade Federal do Maranhão, UFMA, São Luís, Maranhão, Brasil. E-mail: cesar.castro@ufma.br

**Universidade de São Paulo, USP, São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil. E-maill: reisboto@usp.br

This text analyzes the Castilho method in the Revista da Instrução Pública para Portugal e Brasil published in 1857 and 1858 with the aim of strengthening pedagogical relations between the two countries. It addresses the importance of this materiality for the writing of the History of Education. It discusses its graphic characteristics and circulation processes. The correspondence between the writers, António Feliciano de Castilho and Luiz Filipe Leite with the Brazilian teachers, where this method was implemented, is taken as a reference. It is concluded that this source makes it possible to understand the relationships between Portuguese and Brazilian educators in the 19th century.

Keywords: Castilho Method; Teaching Press; Portugal-Brazil Relationship; History of Education

Este texto analisa o método Castilho na Revista da Instrução Pública para Portugal e Brasil, publicada nos anos de 1857 e 1858, com o objetivo de estreitar as relações pedagógicas entre os dois países. Aborda-se e a importância desta materialidade para a escrita da História da Educação. Discorre-se sobre as suas características gráficas e os processos de circulação. Toma-se como referência as correspondências entre os redatores, António Feliciano de Castilho e Luiz Filipe Leite com os professores brasileiros, onde nas quais este método foi implantado. Conclui-se que esta fonte possibilita compreendermos as relações entre os educadores portugueses e brasileiros no Oitocentos.

Palavras- chave: Método Castilho; Imprensa de Ensino; Relação Portugal-Brasil; História da Educação

Este texto analisa el método Castilho de la Revista da Instrucción Pública para Portugal y Brasil publicada en 1857 y 1858 con el objetivo de fortalecer las relaciones pedagógicas entre los dos países. Aborda la importancia de esta materialidad para la escrita de la Historia de la Educación. Se discuten sus características gráficas y los procesos de circulación. Se toma como referencia la correspondencia entre los escritores António Feliciano de Castilho y Luiz Filipe Leite con los profesores brasileños, donde se implementó este método. Se concluye que esta fuente permite comprender las relaciones entre los educadores portugueses y brasileños en el siglo XIX.

Palabras clave: Método Castilho; Prensa Didáctica; Relación Portugal-Brasil; Historia de la Educación

Introduction

The relations between Europe and the Americas were historically established under different forms and perspectives, which were materialized in writings (letters, legislation, drawings, and books) that showed how the transatlantic distances were no obstacle to the circulation of ideas and thoughts between both continents, from the colonial period to the present time. Among the printed media, newspapers and magazines were the main channels for (in)formation and inculcation of rules and values, as pointed out by Bittencourt (2014), Boto (2022), Lajolo (2022 ), Castellanos e Castro (2021), Abreu e Mollier (2018), and Escolano (2017), among other authors, who report directly and indirectly on the circulation of printed media among different nations and temporalities.

With regard to Brazil and Portugal, Silva (2018, p. 262-263), states that:

Luso-Brazilian views on shared cultural realities cross each other on the pages of multiple Luso-Brazilian press entities, published in Portugal and Brazil, creating multiple complicities between writers, journalists, [teachers], and writers from both countries. Thus, we have to consider two issues: the essential importance for Portugal of the Brazilian market in the literary [,] journalistic [and educational] fields, and the relative ease with which professionals in the press [and education] were able to move and work on both sides of the Atlantic.

In this paper1, we take as a source and object of analysis the Revista da Instrução Pública para Portugal e Brasil (1857-1858), whose writers were António Feliciano de Castilho and Luiz Filipe Leite. Relevant presences in literature, in the production of didactic works, and in the Portuguese press, who maintained strong and fertile relations2 with Brazil, through their writings dedicated to scholars, literati, and intellectuals throughout the wide national territory and in the various 19th-century Portuguese possessions on the African continent.

Rogério Fernandes (2000, p. 22), when analyzing this journal in the article “A Luso-Brazilian pedagogical journalism project in the 19th century (1857-1858)”, in the aforementioned journal revisited the main topics addressed in the referred publication, and states that:

In the Portuguese poet’s extensive teaching activity, the significance of the journalistic project of which he was one of the founders and main enthusiasts, the Revista da Instrução Pública para Portugal e Brasil, has not been emphasized. He notes, however, an attempt at cooperation between the pedagogues of the two countries, which, although unsuccessful, was no less meaningful for that. Using a common language, then less different than today, from a literary point of view, among the educated classes, contributed to justifying the option taken. At the same time, identical concerns in the sphere of public education made for a reflection of interest for teachers, policymakers, and men of culture on both sides of the Atlantic. In addition, Castilho seemed to be reasonably familiar with the Brazilian situation, since he had returned shortly before from Brazil, where he had tried to disseminate his reading method and had sought an economic situation suitable to his family’s needs.

António Feliciano de Castilho, with his wide literary production and, mainly, through his teaching method of reading. Luiz Filipe, with his works aimed at children and young people that were adopted in Primary and Secondary school institutions, such as Ramalhetinho da Puerícia (1854), Exercícios de Leitura Manuscrita para Usos das Escolas pelo Método Português (1854), and Do ensino nacional em Portugal (1892). The friendly relationship between them is due to the fact that Luiz Filipe Leite had been, “since he was nineteen, secretary and the most dedicated assistant of the master in the crusade of education,” in Ponta Delgada, as Castilho reports (REVISTA, 1857, p. 11).

Therefore, in this text, when we take Revista de Instrução, we start from the idea that the proposal of the writers was to strengthen the ties between Brazilian and Portuguese educators, serving as means for the dissemination of the Castilho Method, and also to discuss the ideas set forth about public education, reforms and problems in this field, understanding these writings as one of the means, if not the most relevant, to promote an educated civilization, universal and able to equalize Brazil and Portugal, to European nations, which had an “advanced and promising” education system (REVISTA, 1857, p. 21).

Thus, this article aims to analyze the purpose of the production of the journal and the circulation of Castilho’s Portuguese method3, as well as its adoption in Brazil4. In that regard, we present this essay in two parts: in the first part, we describe the journal as a materiality; in the second part, we describe the various receptions of this method in Brazil, taking as reference the correspondence of Brazilian teachers sent to the writers of the journal. Therefore, this text is relevant to the extent that studies on this educator and his reading method are incomplete both in Portugal and in Brazil, as stated by Cunha (2014) and Albuquerque (2019), contrary to his activities as a literate, as highlighted by Ida Alves e Eduardo Cruz (2014), since António Feliciano de Castilho is a

[...] once-famous writer, recognized by his peers and readers in Portugal and Brazil, with nearly 60 years of constant production in different fields (journalism, poetry, narrative, drama, translation, epistolography, historical research, and education), provoking controversies, a target of criticism from the 70’s Generation, in short, a name that was more than present throughout the Portuguese 19th century, with a history of public life that began at the turn of the century, does justice at least to a critical, up-to-date, and more impartial reading of his work, with the demonstration, of course, of his contradictions and weaknesses, but also of his contribution to 19th century Portuguese [and Brazilian] culture. (REVISTA, 1857, p. 11-12).

Regarding this journal, Revista da Instrução Pública para Portugal e Brasil, Fernandes (2000. p. 23) states that “there were few articles that contemplated Brazilian issues”. However, despite the predominance of debates about Portugal, the daily reality of Castilho and Luiz Filipe Leite, the articles about Brazil, in particular, are of great relevance to analyze the adoption of Castilho’s method in 19th century Brazil.

The “Revista da Instrução Pública para Portugal e Brasil”

The Revista da Instrução circulated in Portugal and Brazil from 1857 to 1858 (volume 1 to volume 8), with António Feliciano de Castilho and Luiz Filipe Leite as writers,

[...] and it was released twice a month. [It had 12 pages [...] [with] 24 columns for each issue. Correspondence [was] addressed frankly from the port to Oficina do Progresso in Lisbon. Rua da Cruz do Pau, n .15. To the editorial office; to Luiz Filipe Leite. To the administration, to Francisco Gonçalves Lopes [...]. Overseas, to Brazil, it will be sent to the Revista in the suitcases of sailing ships. The subscriptions, paid in advance, for three months or so. Request[s] that whoever signs this prospectus, or for him to collect signatures in the empire of Brazil, please deliver it with the respective amount, to the Portuguese consular officer in the place, or to the person designated by him. (REVISTA, 1857, p. 3).

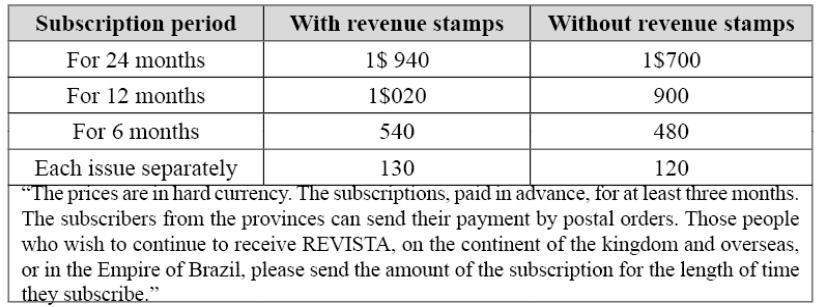

The title of the journal appears in capital letters, Revista da Instrução Pública, and in lowercase letters for Portugal and Brazil, followed by the names of the writers, and is sold to subscribers or by single issues (with or without revenue stamps).

The acts of the Portuguese and Brazilian governments (dismissal, hiring, competitions, and retirement of teachers), instruction of women and workers, report of the Ministry of Public Instruction of Brazil and the General Commission of Public Instruction of Portugal, dissemination of books published in Portugal and intended for schools and, especially, articles by António Feliciano de Castilho, are published in the pages of Revista, making up the main topics present. Moreover, “one of the most innovative aspects of Revista was the use of the history of education as an instrument for the construction of a modern educational system. [...] We believe that, for the first time, the history of education was seen as important in the search for the foundation for political decision and its backwardness pointed out in its negative aspects”(FERNANDES, 2000, p. 34-35).

SOURCE: Revista da Instrução Pública para Portugal e Brasil (1857).

FIGURE 1 -Frontispiece of the Magazine.

SOURCE: Revista da instrução (Pública para Portugal e Brasil), (1ª Edition de 1857).

CHART 1 Revista’ subscription and sales prices.

In the article, “Program that proceeded to the publication of this journal”, in which the writers present the Revista, they state that it had two purposes: the first, “[...] to weigh in the scales of common sense and in the light of current science, what exists, good or bad, great or terrible in the two legislations, to inquire what is lacking or should exist” (REVISTA, 1857, p. 2); the second, “to examine with the same conscience what is done and what has been done in countries where the organization of public education is more advanced, considered administratively, or in its pedagogical and didactic details” (REVISTA, 1857, p. 2).

The confrontation between the Portuguese and Brazilian realities aimed to prepare propositions for Portuguese and Brazilian public education; although they understood that the confrontation would not be an easy task, insofar as it would depend, above all, on the will of the specialists and intellectuals of the two countries, and to “[...] whom the writers should resort to obtaining their opinions, notes and their studies” (REVISTA, 1857, p. 3).

Considering that the pleasure born from mildness is an innocent seduction for the taste of the majority and that no means should be neglected for the sake of the holy end that we demand, let alone beautiful literature, we will sometimes try to relieve with it the fatigue of serious studies, even in order to create them a greater number of sectarians. The example is not new, we have it in the special newspapers of all languages. Take it from France5, mainly. (REVISTA, 1858, p. 3).

Although Castilho and Leite do not evidence such a proposal, the analysis of the Revista allows us to affirm that the purpose of printed media was to disseminate and strengthen the bonds between Brazil and Portugal regarding public education, and mainly to serve as a communication and exposure channel of the Portuguese method6, in face of others adopted in the school institutions of both nations; to a certain extent, they carried out a comparative analysis between the teaching systems, without however “tracing advantages or disadvantages between one and the other” (REVISTA, 1857, p. 2), since, according to the writers, both in Brazil and in Portugal there was not a national education system organized under the principles of modern science and geared towards local needs and regional conveniences; on the contrary, “they were in accordance with the imperious demands of the political position of both countries” (REVISTA, 1857, p. 3), which, they claimed, made it difficult to make “value judgments” about them.

However, Castilho and Leite believed that Portugal, a country with a promising agricultural and manufacturing industry and committed to the improvement of material conditions, but without paying attention to the public education reforms that aimed at a “popular illustration”, despite all its development efforts, would be “nothing but a chimera”. It would not break with “the errors of the past” nor did it project a future that would only be possible “from the union between intellectual and [...] material interests” (REVISTA, 1857, p. 3). Brazil, in turn, a strong nation with a thriving adolescence and with prospects for broad horizons of prosperity and public wealth, should start from the same principles of intellectual aggrandizement and “not hesitate before the broadness of the undertaking” (REVISTA, 1857, p. 5).

For these authors, only through intellectual development, considering Portugal by its geographical and historical position, and Brazil, by the vast territory and natural resources, could make up a “universal civilization” for all peoples, through an “educated opinion, as a safe way to good governments and public greeting” (REVISTA, 1858, p. 2). This would place the two countries on the same level of education, despite their time and historical differences, but with identical aspirations and whose north would be through a “[...] [public] education system that [could reach] the real level of the respective social distinction [;] any efforts intended to make a country progress on the providential road of perfectibility [would be] unsuccessful” (REVISTA, 1858, p. 2-3).

In the article “Preamble”, in which Castilho and Leite present the advantage of the periodical press as a channel for the dissemination of modern science and advances in all branches of knowledge, they draw a peculiar and comprehensive overview of the origin of this materiality, when they state that the “press killed the book [....] the press itself, with the periodical killed the book” (REVISTA, 1857, p. 4).

When analyzing the Revista da Instrução Pública para Portugal e Brasil, Magalhães (2021, p. 24-25) claims that:

António Feliciano de Castilho and Luís Filipe Leite proposed a publication smaller than the book, but not a small book. They refer to a new phase of the Press considered as a means of civilization: from shrouded by ephemeral flyers, appeared the average publications between the newspaper and books, participating in the advantages of one and the other. The authors introduce the idea of ‘the periodical book’ or ‘serial book’. These would be publications with general knowledge and culture; with useful knowledge and reading material; with civic, moral, and vital advice and principles. This type of publication would suit, according to Castilho and Filipe Leite, the multiple audiences that are thrown to it, particularly rural women.

Therefore, the periodical press, for Castilho and Filipe Leite, expanded the reading possibilities, unlike the book, by its form, length, weight, cost, and style, “becoming an oracle for the profane” (REVISTA, 1857, p. 4.), and its “scientific air, deleterious air” (REVISTA, 1857, p. 4) for popular instruction. In contrast, the periodical press, which was born under a principle of democracy and equality for all, was far from meeting this wish and the need of the people, and restricted itself to other purposes, for a certain culture and order of ideas “to which usage has given the name of politics”(REVISTA, 1857, p. 4).

For Castilho and Filipe Leite, each profession and each science founded their “respective weekly, monthly, quarterly publications, under different titles - magazines, almanacs, yearbooks - that as ‘semi-books’” (REVISTA, 1857, p. 4) made it possible to understand the movement and history of different careers: “periodicals for physicians, periodicals for judges, periodicals for farmers, etc.” (REVISTA, 1857, p. 4-5).

In the midst of so many and so diverse groups of journal publications, the lack of a didactic newspaper was felt, but didactic in the sense of the main requirements of the century, which would participate in the book for its powerful and reflective nature and also, a little bit for the extent of exposing and supporting the doctrines, but which at the same time blend in with the flying pages due to the flow of the style, the lack of ambition in the forms, the variety of subjects to be uttered, among these those that best matched the precisions and trends of the present time, for looking more at the present that stops the past; more for the future than for the present and that so many of these gifts or more of them would enhance them with the amenities of literature and the tenuity of prices, a very primary condition. (REVISTA, 1857, p. 5).

According to the writers of Revista, a didactic newspaper should follow the example of a woman in her multiple tasks: mother, wife, farmer, spinner, and “[...] of practical virtues and an open and loving heart. Thus, it should be the Newspaper of Public Instruction, in order to examine what was there with [...] regard to teaching, what it lacks. What is left is the quantity and quality of schools from primary to higher education” (REVISTA, 1857, pa.6), both in Brazil and Portugal. That would be, according to the writers,

The only policy currently possible not only for Europe but for America and for all free peoples, is that of universal civilization. Educated popular opinion is the surest guarantee of stability for good rulers and of public greetings. Through it, we will operate, in the common interest, what would otherwise be confined to the limited sphere of individual convenience. (CORREIO DA TARDE, 1856, p. 3).

This was the purpose and the perspective that stimulated António Feliciano de Castilho and Luís Filipe Leite to publish Revista that, like all the others, especially the specialized ones, lived the dilemma and the difficulties of maintaining its regularity, as stated by its writers in issue number 7, of 1858.

The company, struggling with difficulties, as has happened to all the journals of a similar nature in recent times, states that the publication of the Revista will have to be bimonthly for some time to come, as it happens in this one. As the subscription is counted by the numbers one subscribes to and not by a certain time, this irregularity will not harm the subscribers. (REVISTA ,1857, p. 5).

As a channel for information and dissemination during its life cycle (1857-1858), the Revista was a privileged space for circulating ideas about the Castilho Method in Brazil. In light of this, we will discuss its circulation in the many Brazilian provinces, that is, where its adoption occurred and the main teachers involved in this process.

The Castilho Method in Brazil in the pages of the ‘Revista’

Antonio F. de Castilho’s attempt to spread his method in Brazil for the teaching of reading is an episode in the history of teaching in this country, with interest in itself and also because it is a Luso-Brazilian case in this very field, since A. F. de Castilho, had previously tried with all his might to spread and impose this same method in Portugal. Therefore, the pedagogical campaign of A. F. de Castilho is of interest to the history of education in Portugal and also to the history of education in Brazil, and, we believe that aspects like this are rare in the history of teaching in both countries, after 1823. (CASTELO-BRANCO, 1977, p. 33) (emphasis added).

After the dissemination of the method in Portugal, a strong and virulent campaign against it began, which became in the history of education in Portugal the longest and most heated controversy against a proposal of education, as stated by Castello-Branco (1977), Castilho fought back in the press and in his books Tosquia de um camelo (1853) and Ajuste de contas com os adversários do método português (1854), in which he justified his choices and showed the difference between his method and the “old methods” adopted until then in Portugal.

The enemies of the Portuguese method invented that the teachers who taught by singing and marching were not subject to the law which prescribes teaching to be by simultaneous method, and this is said with a certain air of mockery because these gentlemen ignore the difference between method and manner of teaching7, which in Germany, where education is much more advanced than in Portugal, they teach some subjects through verses, which they tell the children to sing so that they can easily memorize them. They ignore the opinion of the medical committees of Lisbon and Bahia about singing, clapping, and marching in schools, in which these two committees decided that “the lungs have in singing and their gymnastics, which are developed and strengthened by it, and that in no type of people is phthisis so rare as in professional singers, that clapping and marching is the hygiene of the extremities and the whole body in general, that the excessive use of any organ develops it remarkably, and that the organs that are least used in the exercise of their faculties are weakened and atrophied”. (DIÁRIO DE PERNAMBUCO, 1860, p. 3) (emphasis added).

“Echoes” of this campaign for the adoption of his method, initiated by Castilho in Ponta Delgada and in other Portuguese cities, such as Lisbon, Porto, Leria, reach Brazil through many supporters and advocates such as José Nogueira de Jaguaribe8 (congressman for the province of Ceará) and professor(s): Abílio César Borges (Bahia); the priests João Soares de Sousa; and Vicente Júlio Soares (Colégio São Januário); A. E. Zaluar (Colégio Zaluar); Valentim José da Silveira Lopes9, (Rio de Janeiro); José Maria Pereira de Alencastre (Piauí); Raimundo José de Almeida Couceiro (Pará); Secundino José de Farias Simões, Priscila S. Mendes Albuquerque and Francisco de Freitas Gamboa (Pernambuco); Frederico da Costa Rubim (Ceará); Sotero do Reis (Maranhão); Antônio Pedro Pinto (Minas Gerais), among others that adopted and described the advantages of this method with regard to the “old” ones in the Brazilian periodical press: in Jornal do Comércio (1855) and Correio Mercantil (1856) of Rio de Janeiro, in Diário de Pernambuco (1860), in Publicador Maranhense (1858), among others.

For Castello-Branco, as Castilho did not succeed in having his method adopted by the Portuguese education system as he had intended, and because of the heated controversies arising from the method, he turned his attention to Brazil which, according to Júlio de Castilho (in Castello-Branco, p. 33), was a country where first,

[...] his literary name [...] had reached the level of celebrity for many years [...[. Second, the emperor showed himself to be friends with literati in general and distinguished Castilho with special and unequivocal proofs of appreciation [....]. And third, José Feliciano de Castilho’s requests to his brother for a trip to Rio were instantaneous and continuous. (CASTELLO-BRANCO, 1977, p. 37).

With this support and believing in the success of his method in Brazil, Castilho arrived in Rio de Janeiro in February 1855 to teach a course to Brazilian teachers from many provinces, such as Bahia, Pernambuco, Alagoas, who had been summoned for this purpose by D. Pedro II. “On March 22, 1855, the course was inaugurated in the great room of the Military School, and the inaugural session was attended by the Minister of the Empire, members of the State, [the] Inspector General of Public Instruction, teachers from Colégio Pedro II, and a few ladies” (CASTELLO-BRANCO, 1977, p. 36). The course was also widely publicized in the Rio de Janeiro press.

Yesterday Mr. Counselor António Feliciano de Castilho made, in the hall of doctorates of the military school, before a bright and numerous contest, the inaugural speech of the lessons he intends to give to popularize his system of sudden reading. [...] Mr. Counselor Castilho in fluent and lively language, stated two reasons [that] had determined his trip: the first, to pay his respectful tribute to His Excellency D. Pedro II; and the other; to implement in Brazil his system of reading, freeing children from the hardship with which they hitherto purchased the knowledge of the language [...] [He stated that] He was not a lecturer, he was simply a clear exhibitor of a system that is of immense benefit to humanity. Expanding on well-deserved praise for our homeland, Mr. Castilho declared the enrollment or registration for the lessons in which he intended to expose his system open and invited teachers of both sexes, and those who desire the progress of humanity, and especially those who did not believe in his system, to enroll and hear him. (JORNAL DO COMÉRCIO, 1855, p. 3).

The professors at Castilho’s course in Rio de Janeiro, such as Felipe José Alberto (Bahia), Francisco José Soares (Alagoas), Francisco de Freitas Gamboa (Pernambuco), Valentim José da Silveira Lopes (Rio de Janeiro), among others, when returning to their origins, became the interlocutors and supporters of the Castilho method in Brazil, whose correspondence was published in Revista da Instrução, which is the subject of this article10. Correspondence that came in response to the request for a report from the General Commission of Public Instruction in Portugal on the adoption of the Portuguese method throughout the kingdom, to be prepared with the following information: (i) when, where, with what qualification and the number of students with whom the classes began; (ii) the purposes, opposition or resistance encountered about the method; (iii) the results achieved by the students; iv) report of individual experiences and opinion, “on the comparative merit” between the two methods (old ones and Castilho’s) and manners of primary instruction (before and after) existing in the country.

Thus, we ask all professors who may have stopped teaching through the new method, after having accepted and tried it in their schools, to state frankly and explicitly what were the reasons that have led them to such a change. It is hoped that this and other information will come in time for them to be included in a general report, thoroughly analyzed and documented, which this commission should and will soon officially teach to the government and legislative chambers. Lisbon, August 3, 1857 (REVISTA, 1857, p. 3).

What would be the reasons for this report? To demonstrate the efficiency of the Portuguese method before others or to show its inefficiency before others? Was the intention of the General Commission of Public Instruction to verify the higher quality or otherwise of Castilho’s method with regard to those already adopted in Portugal and Brazil? Meanwhile, the Commission describes, based on the survey received from Portuguese professors, a report which highlights the superiority of the Castilho method over others popular in Portugal in the year 1858. So, if this Commission issues an opinion favorable to the Portuguese method, why had it not been adopted and caused controversy among Portuguese intellectuals?

We conclude that the rejection to the Portuguese method was not only related to the method itself, but also to Castilho’s controversy with members of the 70s Generation, such as Antero de Quental, Teófilo Braga, among others (TOIPA, 2014; VELOSO, 2007; CRUZ, 2017); or, perhaps because it was a method that privileged a popular education to attend the less favored strata of society (poor, underprivileged, women, soldiers, farmers, among others) and because Portugal was a society in which the school was aimed at ensuring privileges in the social hierarchy (FERNANDES, 1994, p. 56), the Castilho’s proposal brought a possibility of disruption? In Brazil, besides the aspects similar to Portugal, there was also a slave-owning society that privileged private schools over public schools, which were “[...] essentially destined to the poor black [freedmen] and mixed-race population, of ‘rough habits and values’, not accustomed to social standards nor to the fulfillment of duties and therefore likely to be civilized” (VEIGA, 2007, p. 149).

The Castilho method in Brazil was adopted in the Northeast Region, especially in the provinces of Alagoas, Ceará, Rio Grande do Norte, Bahia, and Piauí. In the Midwest, in the province of Goiás, and in the Southeast, in the Empire’s capital, Minas Gerais, and in Niterói, as it can be seen from the correspondence of the teachers from these locations who “applied the Portuguese method” and were published in Revista de Instrução and in the local newspapers.

Similarly, we conclude that the first professor to adopt the Castilho method in the Northeast was José Francisco Soares, from the province of Alagoas, and that in Pernambuco its expansion was more present, as can be seen in the transcript below.

Pernambuco is an auspicious setting for regenerative primary instruction. There are ten schools based on the Castilho method that are widely attended in Recife, the capital of the Province. The first of the ten, which has the name of the Castilho Method’s head office and had 173 disciples on June 20th of this year, was founded and written by Mr. Francisco de Freitas Gamboa, with expertise, diligence, and results that are astonishing and that public opinion, unanimously, today, pays the most sincere tribute to. The authorities and almost all the journalism of the land, convinced by the multiple, brilliant, and indisputable facts, of the excellence of the new teaching, mastery, and government of Mr. Gamboa fulfills a pleasant duty assisting him [...] He is a man [Mr. Gamboa] undeniably a benefactor, that on the podium, without injury, being overlooked in the pedagogical gallery with which our journal intends to enrich itself and which it hopes will not be, among its parts, the least useful, nor the least pleasant (DIÁRIO DE PERNAMBUCO, 1857, p.17) (author’s emphasis).

In Recife, Professor Gamboa transmitted to other professors the teachings received in Rio de Janeiro, so that they could teach by the Portuguese method, which allowed ten classrooms to operate from the Castilho Method Center, where he would radiate the knowledge and practices for its application to Pernambuco professors. Hence, António Feliciano de Castilho’s deference to Gamboa (CASTELLO-BRANCO, 1977, p. 38), who was, for him, worthy of a place in the “pedagogical gallery” of Brazilian professors. Certainly, this expansion of the Castilho method in Recife is due to his visit (26 hours) to “that tropical Venice” (CURSO DE LATIM, 1857, p. 30) on his return to Portugal, where he was received by several local authorities, such as the president of the province, director of public instruction, poets such as Rangel Barbosa and professor Gamboa e Menna Callado da Fonseca, the principal of a school for girls to whose friendship Castilho dedicates the Latin course he taught at the Royal Academy of Sciences of Lisbon.

Regarding the adoption of the method in Pernambuco, Revista also transcribed an article published in the Diário de Pernambuco, on February 14, 1855, and, in Portugal, in the newspaper Revolução de Setembro, of April 16, 1855, written by a “trustworthy person” (REVISTA, 1857, p. 4).

I am persuaded that only the general power can forbid the Castilho method, since three provinces - Alagoas, Sergipe, [and] Rio Grande do Norte - have adopted it by order of their competent provincial assemblies; besides these, there are private schools in Rio de Janeiro, Bahia, Piauí, Pernambuco, and Ceará using the new method. It would take superhuman strength to make the Silveira Lopes, from the capital of the Empire, the Ibirapitangas and Albertos, from Bahia; the Soares from Alagoas, the Menna, the Drumonds, the Farias Simões, Fonseca, Silva’s, Viana, Maximos Figueiredo, from Pernambuco; the Carneiros da Cunha, the Liberato, in Rio Grande; the Reis and Padre Medeiros, in Apodi and Ceará return.

This description of this “trustworthy person” shows the number of books and their methods adopted in the different locations of Brazil, which, to a certain extent, can, on the one hand, evidence the lack of a national system of teaching elementary schools and, on the other hand, configures a transposition of models from one location to another and internal disputes in each province so that the works of certain authors were adopted in detriment of others. This note is present in the Maranhão province and may configure a national scenario, as addressed by Castellanos in Valdemarin (2022), that is:

Printed media were the means for the dissemination of innovations, including those unleashed in the exemplary spaces that enabled pedagogical practices aligned to the new conceptions. Among them, are the textbooks which contributed by articulating the innovations with specific educational contexts. Produced to circulate in educational institutions, textbooks show the selection that tradition imposes on the process of incorporating meanings. (VALDEMARIN, 2010, p. 209-210).

In Alagoas11, professor José Francisco Soares, returning from Rio de Janeiro after attending Castilho’s course, implemented, in Maceió, his method, stating in a letter to the writers of Revista that its adoption was a complete success and without any negative discussion, which demonstrated the “efficiency and advantages of the new system” (REVISTA, 1858, p. 4). 4); aspects endorsed by the president of the province in his report to the Provincial Assembly in 1856. According to Villela, Chagas and Dias (2022), the 1855 report of Bahia’s provincial president, José Maurício Wanderley, indicated professors Felipe José Alberto and Antonio Gentil to attend the course of António Feliciano de Castilho in Rio de Janeiro, who, upon returning to Salvador, would teach what they had learned to other teachers in order to expand the Portuguese method throughout the province, since: “[...] The experiences made by professors Felipe José Alberto(sic) and Antonio Gentil Ibirapitanga have corresponded to some extent to the author’s promises; but reading the books is not enough, unaccompanied by practice...” (MOACYR apud VILLELA; CHAGAS; DIAS, 2022, p. 96).

Among the two professors, Felipe was the one who had worked the hardest on this task, earning praise from the then inspector of public instruction, Abílio César Borges, for the results achieved with his students in the literacy process using the Castilho method. According to Nogueira (1838), quoted by Villela, Chagas e Dias (2022, p. 4), that “young black teacher fascinated Emperor Pedro II, on his visit to Salvador, who called him to head the Teacher-Training Course of the province of Rio de Janeiro”.

The same Felipe Alberto taught at the elementary school of the São Bento Monastery, in the Court. From the descriptions of the lessons and materials requested, it is also clear that he was practicing the Portuguese method there. Likewise, [...] his performance as a public elementary school teacher in Niterói, leads us to the same conclusion. (VILLELA; CHAGAS; DIAS, 2022, p. 4).

Beyond Rio de Janeiro, in the Southeast region, the Castilho method was adopted in the province of Minas Gerais by professor Gervásio José da Silva Braga, as stated by Villela, Chagas e Dias (2022), and in 1871, the Official Gazette published an article by this professor and a group of parents reporting the positive aspects obtained by their students and children in reading and writing through this method.

Then, the public professor, Gervásio José da Silva Braga, was outraged to know that Castilho’s system had been disapproved by a board of professors established by the government (he does not make it clear which government, but it is more likely to have been the provincial one), gave an account of his school’s routine, guided by the method, praising its advantages over the old system, regretting the time he had not yet known the method of the “great sage”, the “great friend of humanity and childhood” that António Feliciano de Castilho was. (VILLELA; CHAGAS; DIAS, 2022, p. 4).

In Maranhão, the Portuguese method was not adopted, although the Provincial Assembly, on June 19, 1858, approved the granting of 1:200$00 réis to one of the primary professors to learn the Castilho method wherever it was most convenient for him (PUBLICADOR MARANHENSE, 1858). However, Sotero dos Reis, when he was in charge of the General Inspectorate of Public Instruction, discussed the adoption of this method in other provinces and the advantages it offered over other methods, as well as the need to implement it in Maranhão. In correspondence to Sotero dos Reis, Castilho praises the work of the Latinist and grammarian from Maranhão for the publication of Postilhas de gramática geral aplicada à lingua portuguesa pela análise dos clássicos (1866), stating that “[....] among the ones he knew of in Brazil, he considered it the most complete and, therefore, deserving to be adopted throughout the Brazilian Empire”.

Castilho’s relationship with Brazilian authors issuing opinions about his works was frequent in the press, as in the case of Sotero dos Reis, and of Francisco Gomes de Amorim, Portuguese and resident in the province of Pará, on his work Caminhos matutinos (1860).

My dear and most excellent poet - This dear letter of yours has added to the confusion in which I already was, for not having thanked you yet for the gift of the book, and not only the gift, but the very real enjoyment that its reading gave me; (...) on top of all these loves, and wrapped up with them all, there is still some fragrance of homeland, just one of the so sincere and good of the legitimate talking of our people, and such changing reflections of past glories, that I do not want any Portuguese reader, learned or uneducated, classical, romantic, eclectic, skeptic unless a satire of these listed and being entrails who, choosing to open this book on any page, fails to continue to the end and, after reading it, to start it over. (...) Cantos Matutinos will have many and many editions, it will be followed by new poetic collections of the same quill; therefore, I recommend that you enjoy them for yourself and for us, as time goes by, the changes of the years, and the cooling of age do not erase them from your memory and heart, those scenes of intertropical nature, a true paradise to have real fantasies. It came out of the ocean crowned with pearls, become (a single spirit) become America, and return to us carrying the palms that you scorned to pick. (...) From Your Excellency a very affectionate admirer. Lisbon, &c. A. F. Castilho. (DIÁRIO DO GRÃO-PARÁ, 1860).

Even though Brazilian professors recognized the advantage of the method with regard to others adopted in Brazil, they pointed out the difficulties for its adoption, due to the number of materials required, such as those requested by professor José Francisco Soares from the province of Alagoas for his classes using the Castilho method:

This list points out the number of objects necessary for the adoption of the Castilho method, which certainly did not facilitate its application in several Brazilian provinces, while other methods required a smaller number of artifacts for the use of students (slate blackboards, books, pencils, for example), and for teachers (book, desk, board, chair, for example), as reported by professors Gentil Ibirapitanga (Bahia), Joaquim Frederico da Costa Rubim (Ceará) and J. R. Couceiro (Pará). However, Professor José Martins Pereira de Alencastre, from the Piauí province, when describing the importance of adopting it, pointed out that, even if the cost of furniture and other materials were high, the results in the students’ learning justified all the expenses (JORNAL DO COMÉRCIO, 1860, p. 2).

CHART 2 Materials for the Castilho Method classes in the province of Alagoas

| Order | Materials | Qty |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | One Minute Reading Fluency | 01 |

| 2 | Blackboard, for writing with chalk | 01 |

| 3 | Boards whose models are already attached to the compendia | 44 |

| 4 | Wooden boxes for the boards above, to be nailed to the classroom wall | 44 |

| 5 | Large bell tower in imitation of an existing small one | 01 |

| 6 | Editions of transcripts | 02 |

| 7 | Slate blackboards | ------ |

| 8 | Copies of manuscript lessons corrected from the Method by Professor Gentil da Bahia; | 200 |

| 9 | Copies of rules and exercises | 200 |

| 10 | Professor’s desk inkwell | 01 |

| 11 | Cabinet for storing class objects | 01 |

| 12 | Compass | 01 |

| 13 | Small wand, for pointing | 01 |

| 14 | Chalk and sponge | - |

| 15 | Armchair | 01 |

| 16 | Desk to replace the existing one. | 01 |

SOURCE: Albuquerque e Boto (2018).

The report of the Interim Council of the Government of Bahia (1854, p. 14) describes that the generalization of the new system should be noted:

Expenses with [the] material for the classes, renting houses, printing and purchasing the compendia and catechisms [...]. If at first, this budget was almost null or unknown, today it is recognized that for a convenient application of this teaching method, not only the appropriate house and furniture are necessary, but also a compendium and uniforms, we need to provide things so that this branch of service does not absorb the others, for lack of means it becomes less profitable. (RELATÓRIO, 1854, p. 14).

Also, according to Albuquerque e Boto (2018), the opinion issued by professor José Francisco Soares reaffirmed that the Castilho method was more efficient than the old ones, but also pointed out doubts regarding the speed in learning to read, as propagated by its agent and advocates.

[...] it is my opinion that the Castilho method cannot present that advantage of amazing speed, which is said. I do believe that it can improve the old system by the process it creates of memorization and alternate ear reading. The former holds the children’s attention and can make them learn the alphabet in much less time than the old system; therefore, as to writing, Castilho’s system improves the old one in the following terms: that the child who by the old system learned to write well and calligraphically in three years (let us suppose), but without any spelling, today they can learn in the same three years calligraphically and orthographically. It is certainly an improvement, for sure; but there is no astonishing speed. (REPORT OF THE BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION OF ALAGOAS, OF MARCH 26, 1855 apudALBUQUERQUE; BOTO, 2018).

Just as in Portugal, the Castilho method was the target of heated controversy, as evidenced by Duarte (1961 apudALBUQUERQUE; BOTO, 2018, p. 123), in Alagoas,

Such conflicts were politically motivated, since José Alexandre Passos’ brother, Professor Ignacio Joaquim Passos, lost his acting position as professor of Rhetoric at the Maceió High School to Francisco José Soares, who had been chosen by the province’s president to attend the course offered by the Portuguese poet and philologist in Rio de Janeiro.

In Minas Gerais, the method was rejected by a board of professors set up by the government and, in his defense, Professor Gervásio José da Silva Braga claimed that the advantages of the Portuguese Method over the old reading systems were “incomparable” and regretted that he had not known more about the “new method” of the “great sage”, and friend of “humanity and childhood”, that Antonio Feliciano de Castilho was. (VILLELA; CHAGAS; DIAS, 2022, p. 6). Finally, the pages of Revista showed how Castilho sought to maintain relationships with Brazilian literati and professors, which justifies, in our opinion, the impression that the journal constitutes a fertile space as a channel for understanding the cultural, historical, and pedagogical exchanges between Brazil and Portugal, beyond the present time relationships and the respective practices.

Final considerations

The periodical press of education represents a relevant source for us to understand the movement of/in the field of education in different times and spaces, taking into account the present ideas and debates and the claims of professors and students regarding the different levels of education. In this context, the Revista da Instrução Pública para Portugal e Brasil, published by Castilho and Filipe Leite and edited in Lisbon, aimed at narrowing the Atlantic frontier between these two countries, which even with historical differences in time, were united by the language and the desire to achieve intellectual and literary development through public education, equal to European nations and North American countries, taking into account the multiplicity of educational and pedagogical practices established in the pedagogical field in progress.

To this end, Portugal should follow the most modern teaching methods that could make the students the center of the learning process, in a pleasant and fast way, unlike the boring practices that did not present (via archaic teaching methods) the same advantages in the literacy process of Brazilian and Portuguese boys and girls. That, it seems to us, would be Castilho’s proposal in Ponta Delgada: That of creating the Portuguese method that showed the school as a place of knowledge experiences and not as a space in which children and young people had to be kept under torture and, therefore, rejecting reading, writing and mathematical operations, as he portrays in his works focused on education, such as Felicidade pela instrução (1854) and Felicidade pela agricultura (1849), among other texts in which he severely criticizes the Portuguese school institutions and teaching methods and manners, which, due to the conditions of transposition of models, applied to Brazil.

In order to present his method, Castilho traveled to Brazil and, when he returned to Portugal, he published the Revista da Instrução Pública para Portugal e Brasil, which had a short life cycle, although it was a privileged source to identify the circulation of the Portuguese method in the tropics, teaches a course in Rio de Janeiro in which professors from various provinces attend and, upon returning to their places of origin, would implement Castilho’s pedagogical proposal. However, we believe that, due to the presence of several works on literacy published in Brazil, and mainly because of the prospect of breaking the ties with Portugal and establishing a teaching system with national features, his method was not adopted as Castilho intended when he came to Brazil to spread the word about a method capable of breaking with the dull methods present in both countries.

In some places, such as the province of Pernambuco, the expansion of the Castilho method occurred in a more incisive and lasting way than in others, such as Alagoas, where it had a shorter application. What is certain is that this method, just as in Portugal, was present in several regions of Brazil, deserving praise and acceptance in some provinces and, in others, rejection, even if we do not find it as virulent as in the homeland of António Feliciano de Castilho.

Finally, analyzing the literary production of the “blind poet12”, the Castilho’ works related to teaching, and specifically those about his Portuguese method of reading allows us to map countless aspects of public education, among them: The relevance of teaching for girls and for professional education; the role of professors and students in the process of teaching and learning; the meaning of school material culture, among many other possible axes to be investigated and addressed by educational historians, once Feliciano Castilho, as an intellectual and pedagogue, spread teaching in Portugal and Brazil, giving new meanings to local and regional education, thus stimulating transatlantic practices, even if (re)signified in each school culture.

REFERENCES

ABREU, Márcia; MOLLIER, Jean-Yves. Nota Introdutória: circulação transatlântica dos impressos - a globalização da cultura no século XIX. In: GRANJA, Lúcia; LUCA, Tania (Orgs.). Suportes e mediadores: circulação transatlântica dos impressos. Campinas: Editora da Unicamp, 2018. [ Links ]

ALBUQUERQUE, Suzana Lopes de. Métodos de ensino de leitura no Império brasileiro: António Feliciano de Castilho e Joseph Jacotot. Tese (Faculdade de Educação) - Universidade de São Paulo, 2019. Disponível em: https://teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/48/48134/tde-19112019-163229/pt-br.php. Acesso em: 23 abr. 2023. [ Links ]

ALBUQUERQUE, Suzana Lopes de; BOTO, Carlota. Impressos da instrução pública no Império brasileiro sob a lente da filologia. Filol. Linguíst. Port, v. 20, n. 1, p. 115-125, 2018. Disponível em: https://www.revistas.usp.br/flp/article/view/140244. Acesso em: 23 abr. 2023. [ Links ]

ALVES, Ida; CUNHA, Eduardo. Para não esquecer Castilho: cultura literária no Oitocentos. Niterói: Editora da UFF, 2014 [ Links ]

BITTENCOURT, Circe Maria Fernandes. Textbooks and school memory: research and preservation of the books for Projeto Livres. History of Education & Children’s Literature (Testo Stampato), v. 9, p. 135, 2014. [ Links ]

BOTO, Carlota. Sociedade portuguesa em revista: o método da escola e a escola como método no século XIX. Disponivel em; https://www.google.com.br/search?q=sociedade+portuguesa+em+revista%3A+o+m%C3%A9todo+da+escola+e+a+escola+como+m%C3%A9todo+no+s%C3%A9culo+xix&sxsr. Acesso em: 20 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

BOTO, Carlota; ALBUQUERQUE, Suzana Lopes de. Entre idas e vindas: vicissitudes do método Castilho no Brasil do século XIX. Hist. Educ. v. 22 n. 56, p. 16-37, 2018. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/heduc/a/rK7WfrvvbSn9D7w4XgpGKKb/?lang=pt. Acesso em: 23 abr. 2023. [ Links ]

CASTELLANOS, Samuel Luis Velázquez. A circulação dos livros escolares franceses no Maranhão Império (1822-1889). São Luís: Edufma, 2022. [ Links ]

CASTELO-BRANCO, Fernando. Castilho tenta difundir o seu método de leitura no Brasil. Revista da Faculdade de Educação da USP, v. 3, n. 1, p. 32-45, 1977. Disponível em: https://www.revistas.usp.br/rfe/article/view/33235. Acesso em: 23 abr. 2023. [ Links ]

CORREIO DA TARDE, Rio de Janeiro, 2 de julho de 1856. [ Links ]

CORREIO MERCANTIL, Rio de Janeiro, 1o de setembro de 1856. [ Links ]

CRUZ, Eduardo da. Um ‘brilhante congresso’: escritoras portuguesas no projeto de António Feliciano de Castilho para sua versão d’Os Fastos ovidianos. Soletras - Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras e Linguística, n. 34, p. 141-165, 2017. Disponível em: https://www.e-publicacoes.uerj.br/index.php/soletras/article/view/30436. Acesso em: 23 abr. 2023. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Ana Cristina Comandulli da. Presença de António Feliciano de Castilho nas letras oitocentistas portuguesas: sociabilidades e difusão da escrita feminina. Tese (Doutorado em Literatura Comparada) - Universidade Federal Fluminense, 2014. Disponível em: https://app.uff.br/riuff/handle/1/11144?locale-attribute=en. Acesso em: 23 abr. 2023. [ Links ]

CURSO DE LATIM. Diário de Pernambuco, Recife, 4 de maio de 1857, p. 30. [ Links ]

DIÁRIO DO GRÃO-PARÁ, Belém, 4 de abril de 1860, p. 2. n 78. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Rogério. Os caminhos do ABC: sociedade portuguesa e ensino das Primeiras Letras. Porto: Porto Editora, 1994. [ Links ]

LAJOLO, Marisa. O mercado brasileiro na correspondência de Antonio Feliciano de Castilho e Camilo Castelo Branco. Disponível em: https://lusitanistasail.press/index.php/ailpress/catalog/download/25/40/407-1?inline=1. Acesso em: 15 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

JORNAL DO COMÉRCIO, Rio de Janeiro, 23 de março de 1855. [ Links ]

PUBLICADOR MARANHENSE, São Luís, 2 de setembro de 1858, p. 2. [ Links ]

RELATÓRIO DOS TRABALHOS DO CONSELHO INTERINO DO GOVERNO DA BAHIA. 1854. Disponível em: http://bndigital.bn.br/acervo-digital/relatorio-trabalhos-conselho-interino-governo/130605. Acesso em 20 mar. 2022 [ Links ]

REVISTA DE INSTRUÇÃO PÚBLICA PARA PORTUGAL E BRASIL. 1858-1859. Lisboa: Tipografia Progresso, 96 p. [ Links ]

SILVA, Júlio Rodrigues da. As revistas luso-brasileiras (1897-1914): Jornal do Brasil - edição quinzenal ilustrada (1897-1898) e Brasil-Portugal: Revista Ilustrada (1899-1914). In: GRANJA, Lúcia; LUCA, Tania (Orgs.) Suportes e mediadores: circulação transatlântica dos impressos. Campinas: Editora da Unicamp, 2018. [ Links ]

TOIPA, Helena Costa. Castilho, o campo e os clássicos. Máthesis, n. 14, p. 149-167, 2005.Disponível em: https://revistas.ucp.pt/index.php/mathesis/article/view/3943. Acesso em: 23 abr. 2023. [ Links ]

VALDEMARIN, Vera. História dos métodos e materiais de ensino: a escola nova e seus modos de uso. São Paulo: Cortez, 2010. [ Links ]

VEIGA, Cyntia Greive. História da educação. São Paulo: Ática, 2007. [ Links ]

VELOSO, Jane Adriane Gandra. A (de)formação da imagem: Pinheiro Chagas refletido pelo monóculo de Eça de Queirós. Dissertação (Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas) - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2007. Disponível em: https://teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/8/8156/tde-02102007-150520/es.php. Acesso em: 23 abr. 2023. [ Links ]

VILLELA, Heloisa de O. Santos; CHAGAS, Renata Rodrigues, DIAS, Mônica Oliveira. Rotas atlânticas: um poeta português, um professor baiano, destinos cruzados no Rio de Janeiro do século XIX. II Seminário Brasileiro Livro e História Editorial. Disponível em: http://www.livroehistoriaeditorial.pro.br/ii_pdf/Heloisa_Villela_Renata_Chagas_Monica_Dias.pdf. Acesso em: 28 jun. 2022. [ Links ]

1This text is an integral part of the research in development of post-doctoral activities at the Faculty of Education of the University of São Paulo, under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Carlota Boto, and the Faculty of Educational Sciences of the University of Lisbon, under the supervision of Prof. doctor Justino Magalhães, who is supported by Fundação de Amparo under the supervision of Prof. doctor Justino Magalhaes, who is supported by Fundação de Amparo to Scientific and Technological Research and Development in Maranhão - Fapema. (Notice to Scientific and Technological Research and Development in Maranhão - Fapema. (Notice 18/2021- - Process BPD - 04993/21).

2Relationships, in this text, are understood as the communication between readers and writers, about public instruction between Portugal and Brazil.

3In the pages of Revista, we find the expressions Reading Method, Castilho Method, Portuguese Method, and Castilho’s Portuguese Method, all with the same meaning.

4Regarding the adoption of the Castilho Method in Portugal, we suggest reading the text “A Luso-Brazilian pedagogical journalism project in the 19th century (1857-1858)” by professor Rogério Fernandes (see in the References).

5Probably the admiration contained in Castilho’s texts about France as a model of an education system to be “copied” is due to his visit to this country in 1856, in the company of his brother José Feliciano de Castilho (CORREIO MERCANTIL, Rio de Janeiro, September 1, 1856).

6In Revista, we find the names Sudden Reading Method, Castilho Method, and Portuguese Method to refer to his proposal for instruction and education.

7In Felicidade pela instrução, Castilho, explains the difference between method and manner of teaching. For him, “method is an inner and essential process and manner is an inner and accidental process. The teaching of any subject, therefore, requires a method and a manner, for it consists of an intrinsic and an extrinsic part (FELICIDADE PELA INSTRUÇÃO, 1909, p. 33) (Author’s emphasis).

8Jaguaribe advocated that Castilho’s method was adopted in provinces with larger numbers of illiterate people and fewer public schools, and in institutions such as the Army to serve soldiers, as the Duke of Saldanha had done in Portugal.

9Professors Francisco de Freitas Gamboa and Valentim José da Silveira Lopes published several articles in newspapers of Pernambuco, Bahia, and Rio de Janeiro about the importance, advantages, and successful experiences of the Castilho method in Brazil.

10In Revista de Instrução, correspondence and accounts of the adoption of the Castilho method in the Azores, especially in Ponta Delgada, are published. But in this text, we will only focus on Brazil.

11The Castilhos’ relationship with Alagoas seems to have been quite fertile and promising, considering that the 1st edition of the work Iris clássico, by José Feliciano de Castilho Barreto Noronha (brother of António Feliciano de Castilho) was published by Jornal de Alagoas to be adopted in the schools of the province, by order of the then president of the province, Pedro Leão Veloso, and then in Bahia, Ceará, Espírito Santo, Goiás, Maranhão, Minas, Pará, Paraíba, Pernambuco, Piauí, Rio Grande do Norte, Santa Catarina, and Sergipe, as well as in the Council of Public Instruction of the Court and at Colégio de Pedro II.

Received: July 29, 2022; Accepted: March 21, 2023

texto em

texto em