Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1413-2478versão On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.23 Rio de Janeiro 2018 Epub 12-Jan-2018

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782018230009

Article

Teachers’ readings: The circulation of ideas about art and education in Paraná, Brazil, in the 1960s

2Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

This article investigates the circulation of ideas about art and education during the 1960s among educators responsible for the course Visual arts in education, created by the State Secretariat for Education and Culture of Paraná and aimed at qualifying teachers to implement artistic activities in school groups. More specifically, an analysis is performed on the notes made on a 1959 edition of the book Educación por el arte, by the British philosopher Herbert Read, which once belonged to one of the coordinators of the above-mentioned course, professor Lúcia Rysicz. This article relies on Le Goff, whose theorey is that no document is innocuous, and Roger Chartier, who considers notes on the pages of a book a form of intellectual appropriation of texts.

KEYWORDS: education; art; teacher training

Este artigo investiga a circulação de ideias acerca de arte e educação durante a década de 1960 entre os educadores responsáveis pelo curso de artes plásticas na educação criado pela Secretaria de Estado da Educação do Paraná com o objetivo de especializar professores normalistas para implementar atividades artísticas nos grupos escolares do estado. Mais especificamente, analisa anotações feitas nas margens de uma edição de 1959 do livro Educación por el arte do filósofo britânico Herbert Read, exemplar que pertenceu a uma das coordenadoras do curso de artes plásticas na educação, professora Lúcia Rysicz. O artigo apoia-se em Le Goff, segundo o qual nenhum documento é inócuo, e em Roger Chartier, quando este considera as anotações em páginas de livros como uma forma de apropriação intelectual dos textos.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: educação; arte; formação de professores

En este artículo se investiga la circulación de ideas sobre el arte y la educación durante la década de 1960 entre los educadores responsables del curso de artes visuales en educación creados por la Secretaría de Estado de Educación y Cultura de Paraná, con el fin de especializarse maestros para implementar actividades artísticas en escuelas públicas. En concreto, se analiza notas hechas en una edición de 1959 del libro Educación por el arte del filósofo británico Herbert Read, que una vez perteneció a uno de los coordinadores del curso mencionado, la profesora Lucía Rysicz. El artículo se basa en Le Goff, cuya teoría es que ningún documento es inocuo, y Roger Chartier, que considera las notas en las páginas del libro como una forma de apropriación intelectual de los textos.

PALABRAS CLAVE: educación; arte; formación de profesores

This article is part of a wider study of representations of children’s art developed within the postgraduate Program in Education at the Federal University of Paraná in Brazil. More specifically, it analyzes the spread of ideas in art and education among the educators responsible for the course Visual arts in Education1 (CAPE; henceforth all organizations will be referred to by their acronyms in Portuguese) which was created in 1964 by the State Secretariat for Education and Culture of Paraná (SEC-PR).

Based on theories that see artistic practice as a fundamental component of the education process, CAPE was part of a broader project named Art in Education, whose purpose was to support the specialization of teachers for the promotion of artistic activities in state school groups after school hours. Between 1964 and 1974, teachers from various school groups in the State were exempted from their activities for a year to attend CAPE in the city of Curitiba. On completion of the course, they would return to their respective school groups with the responsibility of creating and directing small art schools that were exclusively intended as spaces for artistic activities. In order to achieve this goal, the teachers were accompanied and supervised by people responsible for the creation and intellectual development of CAPE: the artist and educator Ivany Moreira,2 head of the Division of Cultural Activities in Education (DACE) of the Department of Culture of SEC-PR, as well as the teachers Lúcia Rysicz3 and Icléa Guimarães Rodrigues.4 Although in 1969 the coordination of the project reported the existence of twelve art schools across different municipalities, none of them were regulated or officially incorporated into the school groups that housed them until the end of the experiment (Antonio, 2008, p. 156). Eventually, with the implementation of article 5692 in 1971, which progressively replaced school groups in the regular first-grade education system, along with the creation of the Arts Education courses in 1973, CAPE ended its activities upon forming its last group in 1974.

However, the expression art school was not created by CAPE coordinators; it was actually made popular among Brazilian educators in 1948 with the creation of the Escolinha de Arte do Brasil in Rio de Janeiro. This was an initiative of the artist Augusto Rodrigues and a group of educators and artists (INEP, 1980). The experience of Escolinha de Arte do Brasil led to other similar initiatives and also consolidated the School of Art Movement (MEA) in 1961, which brought together several educators around the common goal of disseminating this educational experience in Brazil. The Escolinha de Arte do Brasil main objective was to:

develop in children the full force of their creative power. For this, the group of teachers who integrate it into their work and engage with their students create an atmosphere conducive to freedom, allowing them to express themselves without inhibitions and affirm their personalities. On paper, in clay, with pencils and brushes, it is children who experiment, rehearse, seek, and, more importantly, find their own solutions. (INEP, 1980, p. 37)

An important reference for the creation of Escolinha de Arte do Brasil would have been an exhibition of drawings by English children made during World War II that traveled through several countries, including Brazil, and was shown in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in 1941, and in Belo Horizonte and Curitiba in 1942. Promoted by the British Council, this exhibition was organized by British historian and art critic Herbert Read (1893-1968), who later became perhaps the most influential voice in defending the importance of the presence of artistic practice in the process of educating children. Author of several publications in this area, his most popular book was titled Education Through Art, published in 1943. In this text, Read defends the theory that art should be the basis of education, since this would produce, according to him, people who are efficient in the most diverse means of expression (Read, 2001, p. 12). Herbert Read concludes by deducing that if there is one type of individual better than others, this would be the artist, although he admitted that there is not just one “artistic” type, for:

every individual has their artistic attitude (that is, esthetic), their moments of spontaneous development and of creative activity. Every person is a special type of artist and, in their creative, playful or professional activity (and in a natural society, we affirm, there should be no distinction between work and playful psychology), they are doing more than expressing themselves: they are manifesting the form which our common life should assume in its unfolding. (Read, 2001, p. 344)

Read proposed an education based on creativity, aiming to achieve a universal understanding through the development of sensitivity and tolerance of cultural diversities. These ideals would have influenced the educators and Brazilian artists who formed part of Escolinha de Arte do Brasil, which received Read in 1953 when the Briton came to Brazil to take part in the II Biennial of São Paulo’s International Jury. The following year, Read would host an exhibition of Brazilian children’s drawings in London (INEP, 1980, p. 82).

Besides the British author, another educator, the Austrian Viktor Lowenfeld, exerted an important influence in this area during the second half of the 20th century. Two of his books, Desarrollo de la capacidad creadora of 1961 and El niño y su arte of 1958, published by the Argentinian publisher Kapelusz, made an important contribution to the formation of Brazilian educators interested in the involvement of art in the development of the child. In 1977, El niño y su arte was published in Portuguese by Mestre Jou Publishing. Lowenfeld’s influence may have been more important due to his practical propositions, which enabled a systematization of classroom activities, while Herbert Read may have been “more invoked than read” (Barbosa, 2015, p. 422).

In addition to Read and Lowenfeld, several other authors are cited by CAPE educators in their bibliographic lists. Examination of some of these lists reveals that the basic readings included authors in the field of psychology, among them Emilio Myra y Lopez, who approached the child’s evolutionary psychology as a feature of physiology, and Paul Guillaume, French representative of the Gestalt psychology. It is not surprising to find the Scottish educator Alexander Sutherland Neill with two titles: Freedom Without Fear (Summerhill) and Freedom Without Excess. Summerhill, a small school set up by Neill in the south of England in 1923, was known for the unrestricted freedom granted to students, to the point that they could choose whether or not to study. CAPE’s proposal was not as permissive as Neill’s, but finding his ideas in the bibliographies indicates a belief that the creative spirit would be achieved only by living in a happy and hierarchy-free environment. Another referenced author is the German pedagogue Arno Stern, who at the time was very influential for his publications, including proposals and guidelines for children’s workshops. A number of his books were published in small format by the same Argentinian publisher, Kapelusz. For Stern, a child’s drawing is not a result of imagination but of an organic need that follows specific laws. Here too, it is possible to find correspondences with the CAPE project, especially in the demonstration of respect for children’s artwork and in its importance in the formation of individuality. Finally, the educator Erasmo Pilotto from Paraná is also cited with his text Education is Everybody’s Right, of 1952.5 Pilotto had a great influence on teacher Lúcia Rysicz, as will be seen later.

However, an Argentinian edition in Spanish of the book Education Through Art from 1959 was the main influence for this article. This book belonged to one of CAPE’s coordinators, Lúcia Rysicz, who wrote notes in almost every chapter. These traces, in addition to demonstrating a critical and exhaustive reading undertaken by Rysicz, allow us to examine the influence of Herbert Read’s ideas on the formation of this educator and her key role in the CAPE.

HERBERT READ’S INFLUENCE ON CAPE

The archives corresponding to CAPE and the Art Project in Education are both kept in the Alfredo Andersen Museum (MAA) and the Museum of Contemporary Art of Paraná (MAC-PR), both with headquarters in Curitiba. In these two collections, crafts, minutes, course programs, photographs, standards, and reports of the various activities developed during the ten years of the course were found. The analysis of this documentation reveals some of the theoretical references on which those responsible for coordinating the project based it. Among the most cited are Read and the Italian plastic artist Guido Viaro,6 who settled in Curitiba in the 1930s.

One of the methods used in CAPE to provide students with extracts from reference authors can be observed in the archives of the MAA. This consisted of black and white photographs of texts typed on pages of plain paper. Once the film was developed, the negatives were projected with slide projectors, which allowed the audience to read them. Some of these slides, or negatives in black and white, dated 1971, contain quotations from educators Guido Viaro and Herbert Read. One of them reproduces the following passage by Herbert Read: “The purpose of a reform to the educational system is not to produce more art work, but better people and better societies” (CAPE, 1971a). In another frame produced by the same process, the following quote from the artist Guido Viaro was used:

We have absolutely no intention of training artists. I have always considered this to be among the most ridiculous pretensions. We are limited to simply awakening in the child an interest in the plastic arts. We let the children work freely and express themselves, which is what matters, and gives vent to their fanciful imagination. Our painting and ceramics teachers have clear instructions not to interfere in any way in the work of the children. Guido Viaro. (CAPE, 1971b)

These two quotations bring about fundamental aspects of CAPE. The first one, stated in Read’s passage, is the main justification for the project, as well as for all the art schools that were based on the original proposal by the Escolinha de Arte do Brasil in Rio de Janeiro. Essentially, it was believed that child’s artistic practice could contribute to the formation of an adult with a more balanced personality and thus result in a greater understanding and integration between different cultures. This objective was clearly led by a discourse published and defended by the United Nations Education, Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO) that sought to encourage cultural exchange among children of different countries in the post-World War II period, strongly conditioned by the years of the so-called Cold War.

The passage attributed to Viaro contains a second aspect of high value to the defenders of education through art: non-interference in the work of the child. Viaro wanted to make clear that children under his and his assistant teachers’ guidance had full creative freedom. However, his displays presented contradictory results regarding the freedom allowed to the children. According to Osinski (2008, p. 291), the students selected by Viaro to attend their artistic activities were not allowed to approach certain topics or to seek inspiration from certain sources:

In Viaro’s case, the limits extended to copies of drawings made from external references such as magazines, and to the language of comic stories. In a subtle and non-imposing way, students were also thematically directed. The tests carried out to select pupils for the school are also shown to contradict his position in this sense, serving as an instrument for choosing children more capable of expressing themselves freely than others. (Osinski, 2008, p. 291)

This apparent contradiction between discourse and practice did not prevent the project developed by Viaro from being recognized as a reference in art teaching for children in Paraná, although the work developed in this same period by the educator and Polish artist Emma Koch is also relevant.7

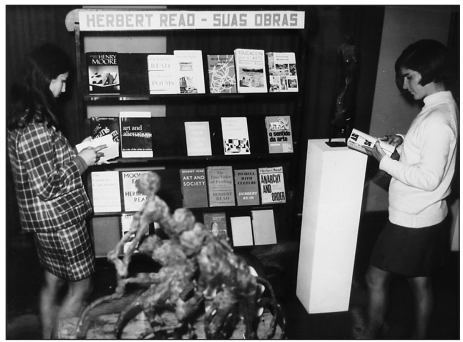

With regard to Read, the references are not only contained in the texts prepared by the CAPE coordinators. During the second Week of Art and Education Studies,8 held by SEC-PR in Curitiba between October 14th and 20th, 1968, with the intention of bringing together the art schools’ teachers from all over the State, a photographic record of a bookcase was made with the objective of divulging some of Read’s works (Figure 1).

Source: Contemporary Art Museum of Paraná.

Figure 1: Bookcase containing Herbert Read’s books in the II Week of Art studies in Education. Curitiba, 1968

The presence of this bookcase at the event might also have been related to the death of the British philosopher in June of that year. Being a posthumous tribute or not, the diverse range of Read’s works that were exhibited demonstrates the importance attributed to him in the training of the teachers present at the meeting. In this image, some titles are visible, but there is no further information that can help clarify their origin or to whom those publications belonged. It is likely that some of the books appearing in this photograph had been loaned to the Department of Culture by the British Council, according to correspondence found in the archives of MAC-PR (British Council, [196-]). Among these titles, there’s a Spanish edition of the book Education Through Art (the second book from the right on the first shelf). Several other titles are present, most of them in English, with the apparent exception of three: O sentido da arte (1968), As origens da forma na arte (1967) e A natureza criadora do humanismo (1967).9

The photographic evidence of these publications leads us to believe that a library had been established for CAPE. Nonetheless, it was not possible before the end of this research to locate a bibliographic set that could be associated with this course. Assuming that there was indeed a bibliographic collection composed of Read’s and other authors’ titles, one may infer that this could have been disassembled upon the end of the course in 1974, assuming it consisted of books owned by the teachers and directors themselves.

Considering that physical access to such library could provide data about the criteria for selecting the titles, editions, and even using and manipulating these books, its location became increasingly important to this research. A search was then started in several probable locations, and information that the private bibliographic collection of one of the teachers of CAPE might have been sold to book merchants was obtained. Although it was not possible to find the books to which the information originally referred, two copies proven significant for the investigation were found.10

DIALOGUES AMIDST READING PRACTICES

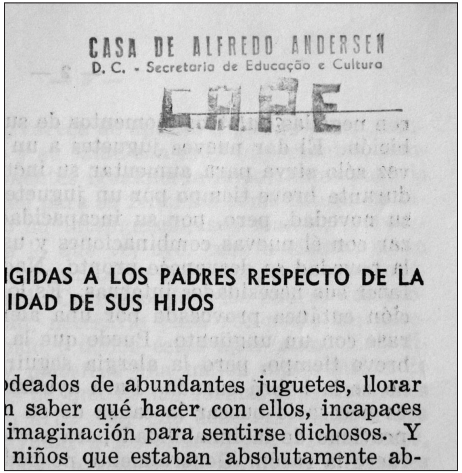

The first book located is an edition of Viktor Lowenfeld’s El niño y su arte, dated 1958, from the Argentinian publisher Kapelusz. In addition to sections underlined in pencil, several pages of this copy bear an impression of a handcrafted stamp carved in wood or linoleum matrix where the initials CAPE are read (Figure 2).

Source: El niño y su arte (Lowenfeld, 1958, p. 1).

Figure 2: CAPE and the Alfredo Andersen House stamps

On page 1, the engraved stamp is placed below the official stamp of Alfredo Andersen House - D. C. - Secretariat of Education and Culture11 of the Department of Culture, which hosted the CAPE. This identification by an institutional stamp reinforces the hypothesis of a course library, even though small or limited.

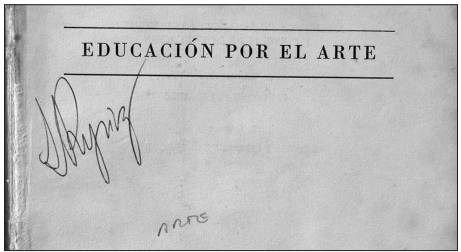

The second book, also an Argentinian edition, is Educación por el arte (translation of the original Education Through Art) by Herbert Read dated 1959, which bears on its cover page teacher Lúcia Rysicz’s signature in ballpoint pen. Rysicz’s signature can be compared with others of several CAPE documents kept by the MAA (Figure 3).

Source: Educación por el arte (Read, 1959).

Figure 3: Teacher Lúcia Rysicz’s signature in the cover page of the book Education Through Art by Herbert Read

A former student of the educator Erasmo Pilotto12 as well as his collaborator in the Pedagogical Studies Association and the Pedagogy Journal in 1958 (Silva, 2014, p. 223), Lúcia Rysicz was a high school teacher in the city of Guarapuava in Paraná when she was transferred in 1965. The transfer was requested by the head of the Department of Culture to the Alfredo Andersen House, which at the time was under the direction of the artist and educator Ivany Moreira (Antonio, 2008, p. 134).

Rysicz’s book has notes made in pencil on a large number of its pages, clear suggestions of meticulous and deep reading. Many of these notes feature the names of her collaborators in CAPE associated with specific portions of the Read’s text. Of greater significance, however, are the handwritten fragments in the margins or at the end of some chapters, which resemble a dialogue between her, the reader, and the author of the book, particularly when Rysicz refers to her doubts or questions about art and education. Today, this copy serves not only as a document that preserves the details of CAPE’s pedagogical planning foundation, but also as testimony of a private moment in the intellectual development of this educator. Originally written without the intention of being manipulated by anyone other than its owner, the book containing these notes was brought before the public when sold to a book dealer and later collected for this research almost by chance.

The institutional archives can be interpreted as a set of documents that were considered the most important and representative of a period by those who selected them. Occasionally, copies of handwritten documents presenting corrections and alterations before assuming their final form can be found. Signs of the internal political conflicts that shaped the final document are often recognized in these drafts. They represent possible agreements arrived at by those involved in the process. On the other hand, personal documents, reflecting intellectual property production, are not commonly found in the institutional archives. For evidencing their creators’ thoughts in construction, subject to corrections and reassessments, doubts and questions, they are not intended for the public due to their transitory character. Private archives are usually the primary place for personal documents, where they are often destined to be forgotten once they have fulfilled their thought-making function. According to Angela de Castro Gomes, when referring to private archives,

By keeping personal documentation, produced with the personality mark and not explicitly intended for the public, his producer would be revealed in a “true” way: it would show himself “in fact”, which would be attested by the spontaneity and the intimacy that mark most of the records. (Gomes, 1998, p. 125)

For Gomes, the documentation found in the private archives would “give life to history” by presenting the virtues and defects of its authors (Gomes, 1998, p. 125). Still considering Prochasson’s contribution, the risk of these files being dispersed is great, whether into small libraries or even the hands of individuals, since in these cases “It is almost always chance that leads the primary research, chance that allows historians to create their own archival resources” (Prochasson, 1998, p. 108). The possibility of this book being a source for the interpretation of the pedagogical ideas CAPE was based on can be seen in the words of Le Goff, when he says:

Through the intervention of the historian who chooses the document, extracting it from the set of data of the past, choosing it over others, assigning it the value of testimony that, at least in part, depends on his own position in the society of his time and on his mental organization, he enters into an initial situation which is even less “neutral” than his intervention. The document is not innocuous. It is, first of all, the result of a conscious or unconscious assembly of the history, the time, the society that produced it, but also of the successive periods during which it continued to live, perhaps forgotten, and during which it continued to be manipulated, albeit by silence. (Le Goff, 2003, p. 537)

At first, Rysicz’s notes in pencil may seem no more than a set of sparse names and phrases, mere remnants of a private and codified reading. However, when looking at CAPE’s files, the names cited are, for the most part, teachers of the course. The relationship between the ideas expressed in the text of the book and the names of her fellow educators is sometimes difficult to interpret and required a cross-check of the research field of each individual mentioned. Adopting this book as a source of study was only possible because of the existence of an institutional file containing enough information to attribute meaning to it, making it possible to relate Rysicz’s annotated thoughts to her actions as a course educator. Still, according to Ragazzini, “the source is a construction of the researcher, that is, a recognition that is constituted by a denomination and an attribution of meaning; it is part of the historiographical operation” (Ragazzini, 2001, p. 14).

Thus, the annotations made by Lúcia Rysicz will be considered here as the result of private and intimate reflections about the teacher’s object of study, which, having fulfilled their reflective function, were eventually discarded, perhaps by herself or by those who possessed the book after her. For this reason, her notes will be analyzed according to CAPE’s political and pedagogical objectives detailed in documents preserved in institutions previously mentioned.

LÚCIA RYSICZ AND THE PROJECT VISUAL ART IN EDUCATION

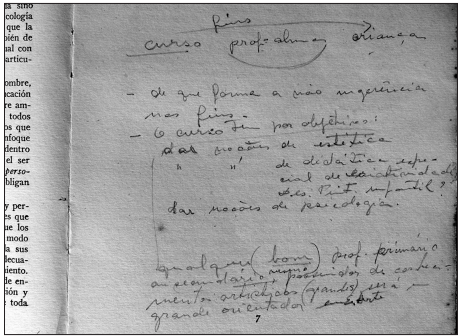

The first records left by Rysicz can be found as early as page 7 of Educación por el arte, revealing that her reading of Read, in addition to influencing the model of the art school project, also raised doubts about the strategies that should be adopted.

As observed in Figure 4, she brings important points about the planning and creation of CAPE when putting the words course, teacher-student, and child side by side. Then, with an arrow, she connects the word course to the word child and, right above the arrow, she writes ends.

The form of her writing systematizes her ideas about the purposes of the course she was involved with and about the relationships teacher-student and the child. The scheme composed of words and graphics can be seen as evidence of their main concerns, i.e., what is the purpose of Visual Art in Education, and how should it be operated. But soon after, Rysicz notes a fundamental question of the course objectives: “how is non-interference defined in the end” (Figure 4). This concerns a basic principle of Visual Art in Education Project’s actions of the period, as well as several previous initiatives that considered artistic experience important in the formation of children. It is possible to reflect on the issues raised by the reading. Should children have total freedom to manifest himself through artistic techniques, how would them behave during the activities at the art school? What attitude should be expected from the teacher in charge? How useful would academic knowledge about art and art history that CAPE anticipated in its curriculum actually be? Lúcia Rysicz questions herself about interference or control over the child’s production inside the art schools, since these should be primarily a space for creativity and freedom.

Moreover, on the same page, she makes reference to the objectives of the teachers’ training course and relates them first to the need for “notions of esthetics”. The course would also need to “provide notions of special didactics of creativity” as well as “notions of psychology”. Rysicz, however, seems to have doubts about the need for these teachers to have notions of children’s drawing and painting, since she includes a question mark after the note “Des. Pint. infantil?” Would this interrogation mark be suggesting questions about the formation of these art teachers or doubts about the actual existence of children’s art?

Right below, on this same page (Figure 4), the educator notes down a reflection about the characteristics needed for an art school teacher: “Any (good) primary or secondary teacher, (even) possessing artistic knowledge (large) will be a great Art advisor”. Would Rysicz be considering that “even” when the teacher has artistic knowledge, they can be a good teacher for an art school? Would she be suggesting that artistic training would be considered by some of her colleagues as an impediment to monitoring school-age children?

The notes made by Lúcia Rysicz represent a dialogue between Herbert Read’s formulations, in this case her interlocutor, and her own experience with CAPE. In order to analyze the reading method adopted by Rysicz and following Michel de Certeau’ ideas, one can consider that:

The reader does not take the place of the author or a place of author. Formulates in the texts something that was not their “intention”. Combines its threads and creates something not known in space, organized by an ability to allow an indefinite plurality of meanings. (Certeau, 2007, p. 265)

Examining the possible conditions for a history of reading practices, Roger Chartier points out that this would be “hindered both by the rarity of direct traces and by the complexity of the interpretation of indirect clues” (Chartier, 2009, p. 77). For Chartier, a reading story will state:

That the meanings of the texts, whatever they may be, are differentially constituted by the readings that seize them. Hence, a double consequence. First of all, to give the reading the status of a creative, inventive, and productive practice, and not to nullify it in the text read, as if the meaning desired by its author should register with all immediacy and transparency, without resistance or deviation, in the spirit of its readers. Then, to think that the reading acts that give the texts plural and mobile meanings are based in the encounter of ways of reading, collective or individual, inherited or innovative, intimate or public, and reading protocols deposited in the read object [...]. (Chartier, 2009, p. 78)

It is also possible to find, in Roger Chartier’s observations about the act of reading, a way of interpreting Lúcia Rysicz’s reading procedure, since

Any reader belongs to an interpretation community and defines themselves in relation to their reading abilities; between the illiterate and the virtuous readers, there is a whole range of capacities that must be reconstructed to understand the starting point of a reading community. Then the reading rules, norms, conventions, and codes of each reading community come. This is the way to add sociocultural reality to the figure of the reader. I can say, in a somewhat simplistic way, that the materiality of the text and the reader’s corporality must be taken into account, but not only from the physical point of view (because reading is making gestures), but also as a socially and culturally constructed corporeity. (Chartier, 2001, p. 31)

Rysicz was not a beginning reader in her area. On the contrary, her notes, which express questions about CAPE and demonstrate knowledge of the activities of other educators, reveal the search for interlocution with an author considered a relevant reference in art and education. In order to understand Rysicz’s doubts and position regarding art and education, it is necessary to refer to two documents that are part of the MAC-PR collection and which can be considered the most representative of CAPE’s13 proposal, due to the detailing and clarity of the objectives and ideological positions of all three coordinators.

The first is a lecture given by Lúcia Rysicz in the city of Ponta Grossa, Brazil, in 1969, where she talked to teachers to explain the proposal of the Visual Art in Education project and presented justifications to add art schools in the national curriculum.14 In this lecture, the question regarding the training of the teachers that would be responsible for art schools can be observed when the subjects studied in CAPE are mentioned, which include drawing, composition, anatomy, diverse techniques, and art history, among others (Rysicz, 1969, p. 9). These disciplines indicate an approximation to the classic study of art, demonstrating an apparent incongruence with the creative freedom to be provided to children. Referring to the evaluation of the works produced within the schools, Rysicz tells the teachers that:

It is not what the child did that matters. What matters is what they have lived, what they have looked at, experienced from the outside world and then integrated into their personality, assimilated, and expressed through drawing, as an expression, but their expression, an utterly personal expression. Only then will it be a good drawing. (Rysicz, 1969, p. 6)

Apparently, teachers should not rely on the disciplines studied in CAPE’s curriculum to classify the drawings produced by children, but rather consider whether these drawings demonstrated free will or had undergone any adult interference: “We can, therefore, classify the child’s drawing, giving it a concept, but in that sense - what is theirs and what someone has imposed on them” (Rysicz, 1969, p. 6).

In her reading of Read, Rysicz underlined quotes which demonstrate the British author’s opinion of the role of the teacher on page 232:

In general terms, self-expression activity cannot be taught. Any application of an external norm, whether of technique or of form, immediately induces inhibitions and undermines the whole objective. The role of the teacher is that of an assistant, guide, inspirer, psychic midwife. (Read, 1959, p. 232)

Further on the same page, the author completes his considerations, noting that:

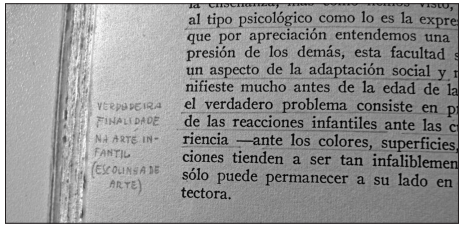

The real problem is to preserve the original intensity of children’s reactions to the sensitive qualities of experience - in the face of colors, surfaces, shapes and rhythms. These reactions tend to be so infallibly “right” that the teacher can only remain by their side in a kind of protective reverence. (Read, 1959, p. 232)

Lúcia Rysicz underlined this passage and wrote on the margin of the page: “true purpose in children’s art (art school)” (Figure 5).

Read defined self-expression as the “innate need of the individual to communicate to other individuals their thoughts, feelings, and emotions” (Read, 1959, p. 231), and Rysicz in turn uses the term “free expression” when referring to the work of art schools. In Read’s text, the definition of free expression can be found in Chapter V, “The Art of Children” (1959, p. 134), where the author comments that children, like adults, have states of mind that they wish to express. This expression would be governed by the child’s somatic and psychological dispositions, “but because it is relatively indirect and apparently not intended to achieve the satisfaction of an immediate need, we call it ‘free expression’” (Read, 1959, p. 134). The author further adds that “‘free’ expression does not necessarily mean ‘artistic’ expression” (Read, 1959, p. 135).

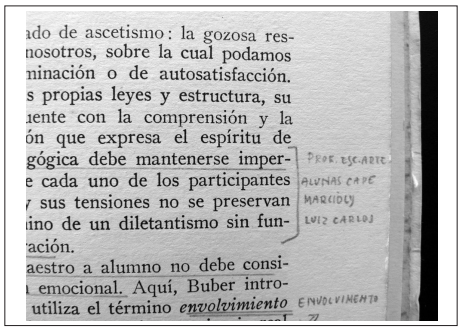

Regarding the relationship between the art school teacher and the student, Rysicz wrote “art school teachers” and “CAPE students” (Figure 6) next to the passage in which Read considers that pedagogical relationships must remain impersonal because if the private spheres of the participants were manifested, this would eventually result in pure baseless dilettantism (Read, 1959, p. 311).

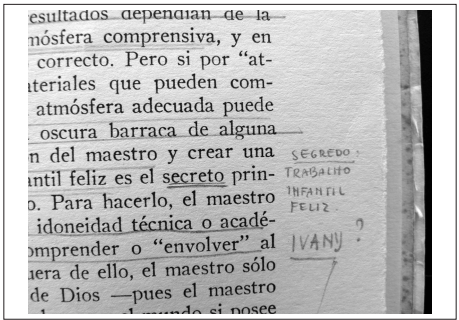

In her notes, Rysicz seems to show concern about the way practices were conducted in art schools, considering the risk of these resulting in empty activities due to the lack of the teacher’s guidance. Later she seems to agree with Read when he concludes that the atmosphere required for the art school is created by the teachers and that the spontaneity necessary for the production of a happy child’s work is the secret to the success of their job (Read, 1959, p. 315). Alongside this passage, Rysicz notes, repeating the author’s expression, “secret: happy child’s work” (Figure 7).

However, the educator’s reading reveals, on the following page, doubts regarding the purpose of one of the art schools in particular, since she notes, at the end of the chapter, “Art school ‘Col. Abranches’, what is the objective? A citizen?” At this point, Lúcia Rysicz reflects on the purpose of art schools by citing a specific school, Abranches College in Curitiba, where this question may have been raised. Here one can infer her concern about the purpose of the proposal when provoked by Read’s reading.

The second document mentioned above was written by Lúcia Rysicz, Ivany Moreira, and Icléa Rodrigues under the title Art in Education: Thesis Presented by the Cultural Activities in Education Division and Alfredo Andersen House during the First Teaching Symposium in Paraná15 (I SENPAR).16 However, there is no reference to this document among the various theses presented at this Symposium, although the final recommendations point out the need for art schools and training courses for the “teacher who wishes to work in Visual Art in Education” (Paraná, 1969). In the text, the three educators requested that the art schools already existing within Paraná’s school groups were made official by the state under the direction of a specialist formed by CAPE - a request that was necessary since, according to Antonio (2008, p. 157), the schools had already stablished were facing operational difficulties that threatened their continuity.

Justifying the newly proposed formation, the educators affirm in their thesis that the teacher who will act in the art schools must be specialized “not to be an artist, but to be able to feel and to integrate in himself the creativity and the free expression” (Rysicz, Rodrigues e Moreira, 1969, p. 8). Here, the importance placed on the activity called “free expression” that is associated with creativity can be appreciated. Further, the development of the educator, considered “anti-natural” and “bookish,” is referred to as the main factor responsible for loss of creative capacity, “a basic condition that provides the human with evolution possibilities”. The authors refer to “integral education” as the final objective in their justifications for the insertion of art schools into school groups, defending it as the ideal environment for the development of creative capacity, a basic component of the integral development of the child (Rysicz, Rodrigues and Moreira, 1969, p. 5).

The project Visual Art in Education brings about the need to build a new sort of teacher with new attitudes not only in the classroom, but towards their own training. The educators emphasize the need for “deep respect for the child,” which can be interpreted here as respect for their freedom to create. Nonetheless, the teacher specialized by CAPE would need to solve a problem: “Be able to create an environment conducive to the free activities of the child; be a stimulating person, but without imposing themselves”. And still “exercise this orientation whilst reorganizing their personality accordingly” (Rysicz, Rodrigues e Moreira, 1969, p. 8).

In accordance with the proposal, this specialized teacher would work with these school groups outside school hours without the children being obliged by curricular requirements to attend these, the teacher’s mission being to stimulate this attendance. The art school teachers would be professionals “carefully prepared to free themselves from the rigidity of their life that prevents them from communicating with the child and, silently and expectantly, to provide them with stimuli, inspirations, guidance, encouraging them to create and to express themselves” (Rysicz, Rodrigues e Moreira, 1969, p. 8).

The educators concluded the document with several proposals, including the state government as regulator of art schools inside school groups under the responsibility of the school director, which are under the control of the SEC. They demanded a space of their own, “independent of the school body, to give the child a mark of freedom”. According to Antonio (2008, p. 190), these two proposals are the main problems faced by the art schools that were created by CAPE up to that point and that had never had full institutionalization - permanence in operation and possession of their own physical space. The request for regulation of the art schools is due to the difficulty of maintaining an activity that, while seeking to belong to the school group, criticized it as an environment not suitable for the development of the child. This becomes more evident when educators include in their proposals the need for a specific independent area, but one within the school body, which most likely caused clashes between the directors of the school groups and the project coordinators. This 1969 document suggests that after five years of attempting to establish and maintain art schools within the school groups in Curitiba and other regions of the state, CAPE educators concluded that the continuity of this experience would only be possible under the determination of the state government to create and establish the art schools.

In its final resolutions, the First Teaching Symposium in Paraná (I SENPAR) contemplated the request of educators only in part. Although supportive of the creation of art schools, it simply recommended that teachers interested in being part of them provide a proof of qualification without the need to pursue a specialization as proposed by CAPE. With this recommendation, Visual Art in Education lost much of its political strength within SEC-PR, entering a period of uncertainty and eventually stopping its activities after federal law n. 5692 was enacted in 1971, making it compulsory to include the Artistic Education discipline in the Brazilian schools’ curriculum. This obligation, however, envisaged a multi-purpose professional who was to work with a multiplicity of techniques and diverse artistic manifestations, far from the professional dedicated to stimulating the child’s creative freedom as idealized by Lúcia Rysicz and her colleagues (Antonio, 2008, p. 191).

Finally, when looking at Rysicz’s writings in CAPE’s files, it is possible to identify the issues that preoccupied the educator. At the same time, her notes reveal the contribution of her reading to the development of her knowledge of art and education and how much the teacher found in Read an interlocutor who helped her to construct meanings that allowed the materialization of her projects and ideals.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

This copy of Educación por el arte is a particular edition because it contains fragments of a reading process aimed at the training practices of young art teachers. It mainly contains indications of Lúcia Rysicz’s method of study, her doubts and questions arranged in layers of reflections about CAPE’s creation and the possible purpose of introducing art into the daily lives of the school groups. It also allowed us to interpret Rysicz as a coauthor of Read’s work, who interprets between the lines based on her own work and experience.

Another particularity of this source relates to the evidence about it provides of the British author’s diffusion of ideas and practices. The reading and appropriation of the texts’ practices identified here demonstrate that the circulation of these concepts among the training teachers would not have occurred through the direct reading of certain titles. Since the Portuguese versions of Read and Lowenfeld were only published after the 1960s and the Argentinian editions were the only ones available, it is thus probable that only a small number of educators had access to these authors’ ideas during this period. It seems that the introduction of these theories into CAPE was done through readings undertaken by their coordinators and disseminated during lessons through lectures, and typed texts. Read may not have been a theorist with practical proposals for the classroom like Lowenfeld, but this particular source is the record of his theoretical influence and how his ideas would have circulated in that environment.

The interferences made by Rysicz are important in understanding the collective construction of a curriculum that had as its purpose the formation of a specialized professional, one not yet existent in the school groups. The names annotated alongside various sections of the book take on meaning when they are identified as educators belonging to CAPE or other educational institutions of Curitiba. In writing them down, it is likely that the teacher associated portions of Read’s ideas with the activities developed by each of these educators, their areas of affinity, or the work divisions within CAPE.

The contribution of Read’s reading appears with greater definition in Rysicz’s lecture and in the document presented to I SENPAR in 1969. The strategies chosen by the CAPE educators suggest that in order for the free and creative activities proposed by Read and Lowenfeld to be able to coexist, adaptations to the traditional school culture would be necessary. This reading is not intended for future elaboration. Rysicz’s reading of Read is based on her experience and on a project in progress and which evolved in accordance with institutional rules. For this reason, her notes present questions that demonstrate doubts about the route to be followed.

Unlike most of the documents in the official archives, the writings Rysicz left in her book did not undergo the revisions and care that are common in texts designed to go through institutional paths. Recovered almost by chance, they have become vestiges of the intellectual presence of this educator and are a reminder of the fragility of private archives and how they preserve in silence the possibility of historical interpretation.

Finally, thinking like Michel de Certeau (2007, p. 269) when he sees the reader as a “producer of gardens that miniaturize and congregate a world”, it is possible to identify in the traces of Lúcia Rysicz’s reading the ideals of a generation of educators who believed that art could transform education.

REFERENCES

Antonio, R. C. A escola de arte de Alfredo Andersen, 1902-1962. 2001. 134f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Setor de Educação, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2001. [ Links ]

Antonio, R. C. Arte na educação: o projeto de implantação de escolinhasde arte nas escolas primárias paranaenses (décadas de 1960-1970). 2008. 206f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Setor de Educação, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2008. [ Links ]

Barbosa, A. M. Redesenhando o desenho: educadores, política e história. São Paulo: Cortez, 2015. [ Links ]

Brasil. Lei n. 5.692, de 11 de agosto de 1971. Fixa Diretrizes e Bases para o ensino do 1º e 2º graus, e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 12 de agosto de 1971. Seção 1, p. 6.377. [ Links ]

Certeau, M. A invenção do cotidiano. 1. Artes de fazer. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2007. [ Links ]

Chartier, R. Cultura escrita, literatura e história: conversas de Roger Chartier com Carlos Agirre Anaya, Jesús Anaya Rosique, Daniel Goldin e Antonio Saborit. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2001. [ Links ]

Chartier, R. Do livro à leitura. In: Chartier, R. (Org.). Práticas da leitura. São Paulo: Estação Liberdade, 2009. p. 77. [ Links ]

Gomes, A. C. Nas malhas do feitiço: o historiador e os encantos dos arquivos privados. Revista Estudos Históricos, Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Getúlio Vargas, v. 11, n. 21, p. 121-127, 1998. [ Links ]

Le Goff, J. História e memória. Tradução de Bernardo Leitão. Campinas: Editora da UNICAMP, 2003. [ Links ]

Osinski, D. R. B. A modernidade no sótão: educação e arte em Guido Viaro. Curitiba: Editora UFPR, 2008. [ Links ]

Osinski, D. R. B.; Simão, G. Emma Kleè Koch e as exposições de arte infantil: rituais coloridos pela educação moderna (1949-1952). Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, Maringá: UEM, v. 14, n. 1 (34), p. 195-222, jan./abr. 2014. [ Links ]

Prochasson, C. “Atenção: verdade!” Arquivos privados e renovação das práticas historiográficas. Revista Estudos Históricos, Rio de Janeiro: CPDOC, v. 11, n. 21, p. 105-119, 1998. [ Links ]

Ragazzini, D. Para quem e o que testemunham as fontes da história da educação? Educar em Revista, Curitiba: UFPR, n. 18, p. 13-28, 2001. [ Links ]

Read, H. E. A natureza criadora do humanismo. Rio de Janeiro: Fundo de Cultura, 1967. 40p. [ Links ]

Read, H. E. As origens da forma na arte. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1967. 202p. [ Links ]

Read, H. E. O sentido da arte: esboço da história da arte, principalmente da pintura e da escultura, e das bases dos julgamentos estéticos. 6. ed. São Paulo: IBRASA, 1987. 166p. [ Links ]

Read, H. E. A educação pela arte. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2001. [ Links ]

Silva, R. O CAPE e a formação do professor de arte nos anos de 1964 a 1975 em Curitiba. 2002. Monografia (Curso de Especialização em Fundamentos Estéticos do Ensino da Arte) - Faculdade de Artes do Paraná, Curitiba, 2002. [ Links ]

Silva, R. Educação, arte e política: a trajetória intelectual de Erasmo Pilotto. 2014. 341f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Setor de Educação, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2014. [ Links ]

Vieira, C. E. O Movimento da Escola Nova no Paraná: trajetória e ideias educativas de Erasmo Pilotto. Educar em Revista, Curitiba: UFPR, n. 18, p. 53-73, 2001. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

British Council. Lista de livros de Herbert Read emprestados para a Casa Alfredo Andersen. [196-]. Pasta DACE-DC-SEC ARQUIVO 1969, Museu de Arte Contemporânea do Paraná, Curitiba. [ Links ]

CAPE - Curso de Artes Plásticas na Educação. [Texto de Herbert Read]. 1971a. Fotograma, p&b, 35mm. Arquivo do Museu Alfredo Andersen. [ Links ]

CAPE - Curso de Artes Plásticas na Educação. [Texto de Guido Viaro]. 1971b. Fotograma, p&b, 35mm. Arquivo do Museu Alfredo Andersen. [ Links ]

INEP - Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais. Escolinha de Arte do Brasil. Brasília, 1980. (Coordenação: Augusto Rodrigues). [ Links ]

Lowenfeld, V. Desarrollo de la capacidad creadora. Buenos Aires: Editoral Kapelusz, 1961. [ Links ]

Lowenfeld, V. El niño y su arte. Buenos Aires: Editoral Kapelusz , 1958. [ Links ]

Lowenfeld, V. A criança e sua arte (um guia para os pais). São Paulo: Editora Mestre Jou, 1977. [ Links ]

Neill, A. S. Summerhill: a radical approach to child rearing. New York City: Hart Publishing Company: 1960. [ Links ]

Neill, A. Freedom - not license! New York: Hart Publishing Company, 1966. [ Links ]

Neill, A. Liberdade sem medo (Summerhill). São Paulo: Editora Ibrasa, 1968. [ Links ]

Neill, A. Liberdade sem excesso. São Paulo: Editora Ibrasa , 1968. [ Links ]

Paraná. Secretaria de Educação e Cultura. I SENPAR: recomendações finais. Curitiba, 13-20 dez. 1969. [ Links ]

Pilotto, E. A educação é direito de todos. Curitiba: 1952. [ Links ]

Read, H. Educación por el arte. Buenos Aires: Editorial Paidós, 1959. [ Links ]

Rysicz, L. [Anotações manuscritas em livro impresso]. [196-]. In: Read, H. Educación por el arte. Buenos Aires: Editorial Paidós , 1959. Acervo do autor. [ Links ]

Rysicz, L. Palestra proferida no evento Tempo de Cultura em Ponta Grossa. Ponta Grossa, 1969. Arquivo do Museu Alfredo Andersen. [ Links ]

Rysicz, L.; Rodrigues, I. G.; Moreira, I. Arte na educação: tese apresentada pela Divisão de Atividades Culturais na Educação e Casa de Alfredo Andersen durante o I Simpósio de Ensino no Paraná. Curitiba, 13 a 20 dez. 1969. Arquivo do Museu de Arte Contemporânea do Paraná. [ Links ]

Simpósio de Ensino do Paraná, I., 1969, Curitiba. Discursos proferidos na sessão solene de abertura do I SENPAR. Curitiba: Secretaria de Educação e Cultura, 1969. [ Links ]

Simpósio de Ensino do Paraná, I., 1969, Curitiba. Recomendações finais. Curitiba: Secretaria de Educação e Cultura , 1969. [ Links ]

1 CAPE was studied by Silva (2002) and Antonio (2008).

4 In 1963, teacher Icléa Guimarães Rodrigues (1941) was exempted by SEC-PR to attend the intensive Art in Education course delivered by the Escolinha de Arte do Brasil in Rio de Janeiro. Upon her return to Curitiba, she was transferred to the Department of Culture and appointed coordinator of CAPE in June 1965.

5 A educação é direito de todos (Pilotto, 1952).

6 There are indications that the Italian painter Guido Viaro (1897-1971) was involved with art education for groups of children in the late 1930s in Curitiba. However, his most significant contribution to this area was the creation of the Visual Arts Youth Center in 1953, which remains active in the State of Paraná to date. About Viaro, see Osinski (2008).

7 The artist and educator Emma Koch was born in Poland in 1904 and immigrated to Brazil in 1929, where she settled in the city of Curitiba in 1940 at the invitation of the Polish Consulate. In 1949, she was entrusted by the then-Education and Culture Secretary, Erasmo Pilotto, to lead the reform of artistic education in the schools of Paraná. About Koch, see Osinski and Simão (2014).

8 CAPE’s coordinators conducted three of the Week of Art and Education Studies, seeking not only greater integration between the art schools’ teachers but also greater visibility for the state project of Visual Art in Education. Activities such as lectures, recycling workshops, and evaluation of working conditions were included.

11 The Alfredo Andersen House was a museum and art school that preserved the memory of this Norwegian artist, who settled in Curitiba in 1902. Part of the Department of Culture of SEC-PR, this institution hosted CAPE after its creation in 1964. Now called the Alfredo Andersen Museum, it remains a state institution that, in addition to preserving and disseminating the artist’s work, delivers courses and art workshops. About Alfredo Andersen House, see Antonio (2001).

12 One of the main articulators of the New School in Paraná Movement, Erasmo Pilotto (1910-1992) was secretary of state for Education and Culture from 1946 to 1952. In 1956 he created the Pedagogical Studies Association (AEP), whose proposal was to discuss methods and educational policies for public schools. The Pedagogy Journal was an AEP publication that issued five volumes and 22 issues from 1957 to 1966. About Pilotto, see Vieira (2001) and Silva (2014).

13 About these texts, see Antonio (2008).

15 Arte na educação: tese apresentada pela Divisão de Atividades Culturais na Educação e Casa de Alfredo Andersen durante o I Simpósio de Ensino no Paraná (Rysicz, Rodrigues and Moreira, 1969).

16The First Teaching Symposium in Paraná, I SENPAR, was organized by State Secretariat for Education and Culture of Paraná, in Curitiba, between December 13th and 20th, 1969. According to its dossier, it was attended by representatives of national and international organizations, including the National Department of Education, Federal Council of Education, and institutions linked to UNESCO, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and United Nations (UN). In its final document, Artistic Education was recommended for inclusion as a compulsory discipline of the school curriculum, which would be realized two years later with the enactment of law n. 5692.

Received: August 20, 2015; Accepted: May 16, 2016

texto em

texto em