Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1413-2478versão On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.24 Rio de Janeiro 2019 Epub 29-Set-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782019240042

Article

Practices adopted in the state of Espírito Santo to overcome grade retention in literacy classes (1960-1970)

IUniversidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, ES, Brazil.

This paper aims mainly to understand two practices engaged by the Secretary of Education and Culture to promote the enhancement of approval rates in public schools, in the state of Espírito Santo, in the 1960s and 1970s, by establishing criteria for the creation of homogeneous groups and system of assessment of learning mainly in the first grade, in which grade retention rates were more alarming. It emerges from a historical research in which documents generated in the period were analyzed. It has as theoretical reference writings of Mikhail Bakhtin in the field of philosophy of language. It concludes that the criteria for group creation and assessments did not contribute significantly to the growth of the approval rates, making development difficult for poor children in public schools.

KEYWORDS: history of literacy; assessment of literacy; creation of groups; teaching-learning

Este artigo teve por objetivo central compreender duas ações empreendidas pela Secretaria de Estado da Educação e Cultura para promover a melhoria dos índices de aprovação das escolas públicas do Espírito Santo, nas décadas de 1960 e 70, por meio do estabelecimento de critérios para a formação de turmas homogêneas e de sistema de avaliação da aprendizagem principalmente na 1ª série, em que os índices de repetência eram mais preocupantes. Resulta de uma pesquisa histórica em que foram analisados documentos produzidos no período. Teve como referencial teórico escritos de Mikhail Bakhtin no campo da filosofia da linguagem. Concluiu que os critérios de formação de turmas e avaliações não contribuíram significativamente para a elevação dos índices de aprovação, dificultando o desenvolvimento das crianças pobres nas escolas públicas.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: história da alfabetização; avaliação da alfabetização; formação de turmas; ensino-aprendizagem

Este artículo tiene por objetivo central comprender dos acciones emprendidas por la Secretaría de Educación y Cultura para promover la mejora de los índices de aprobación en las escuelas públicas, en Espírito Santo, en las décadas de 1960 y 1970, por medio del establecimiento de criterios para la formación de grupos homogéneos y de sistema de evaluación del aprendizaje principalmente en la primera serie, en que los índices de repetición eran más preocupantes. Es el resultado de una investigación histórica en la que se analizaron documentos producidos en el período. Tiene como referencial teórico los escritos de Mikhail Bakhtin en el campo de la filosofía del lenguaje. Concluye que los criterios de formación de clases y evaluaciones no contribuyeron significativamente al aumento de los índices de aprobación, dificultando el desarrollo de los niños pobres en las escuelas públicas.

PALABRAS CLAVE: historia de la alfabetización; evaluación de la alfabetización; formación de clases; enseñanza-aprendizaje

INTRODUCTION

This article is part of a group of studies that investigate the history of literacy in Espírito Santo State, based on the understanding that literacy of children, youth, adolescents and adults continues to be a challenge for scholars, administrators, governments and society in the 21st century. Thus, its main objective was to analyze two methods used by the State Secretariat of Education to promote improved approval rates of students in public schools, in Espírito Santo, in the 1960s and 1970s, i.e., criteria for the formation of homogenous classes and for the evaluation of learning, mainly in the first grade, whose rates of being held back caused more concern.

Being retained can be considered one of the most dramatic forms of school and social exclusion. It functions as a stigma that negatively marks the body, and the school and community life of the subjects, once that retained students come to be seen by their families and community as incapable of learning what the school teaches, and thus as unfit for life in modern society. In schools, the existence of classes of students who were retained contributes to leaving deep and long-lasting marks, through continued exposure of the children in these classes. As if low grades were not enough, it was necessary to publicly expose those left behind to colleagues, teachers, parents and the community.

Given the growing demand for schooling over the history of Brazilian education, holding students back became quite inconvenient, because it would keep children in school for more time and prevent vacancies from being released to serve those who need them. As the demand increased, educational administrative entities had to secure vacancies for new plaintiffs. In 1960, of the 147,061 students registered in public schools in Espírito Santo, 71,493 were promoted and 45,804 were retained (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1961).

Given this situation, two measures were adopted in the state to solve the problem of school retention that in principle produces a distortion between a student’s age and their grade of study, difficulties in being promoted and exclusion of students from educational processes. As mentioned, the measures consist in the adoption of criteria for formation of homogenous classes and for the evaluation of learning. The measures were implemented in the 1960s and 1970s by the Secretariat of Education and Culture of Espírito Santo State.

A number of studies have currently been dedicated to investigating literacy in the 1960s and 1970s, thus encompassing the military dictatorship period, which imposed severe limits on national democratization processes. Among these studies, we can cite those by Mortatti (2000), Cardoso (2011) and Dornfeld (2013). The study by Mortatti (2000) encompassed a broader period (1876 to 1994) and thus examined literacy education in São Paulo State during all of the dictatorship (1964 to 1985). This work inaugurated studies in the history of literacy education in Brazil and is a landmark study that inspired other researchers to become interested in and conduct studies on the history of literacy. The study by Cardoso (2011) discusses the directions by Ada and Edu, adopted in Mato Grosso State, from 1977 to 1985, while Dornfeld (2013)’s work focused on the analysis of curricular guides used in São Paulo State to coordinate teaching in literacy classes, mainly in the 1970s.

In general, as the three studies mentioned demonstrate, much of the research in the history of literacy education is dedicated to analyzing, in different moments of history, primers and methods used to teach reading. The study by Dornfeld (2013) analyzes curricular guidelines from the Secretariat of Education of São Paulo. This article, as mentioned, also has this objective, that is, to analyze the actions of the state entity that administers education. However, it will focus on criteria for the organization of classes and evaluations, actions little explored in the literature about the history of literacy. Evaluation continues to be a central issue in Brazilian and international literacy education policies to this day.

The analyses that support this article result from a documentary research based on documents and texts produced in the 1960s and 1970s to guide actions in public schools in Espírito Santo State. According to Bakhtin (2003), the text (written or oral) uses a language system to produce meanings. As a unit of signification, it is a product of ideological creation and, thus, can only be understood and studied in relation to society, that is, within the historic, cultural, social, political, economic, religious, etc. context in which it was produced. The text is the dialog between interlocutors and with other texts. The sources analyzed can be classified, according to Mortatti (2000, p. 30), as primary or direct, because “they are documents produced by subjects from the period that is being examined (subjects at the time)” (Mortatti, 2000, p. 30). The texts/documents explored in this article respond to the need to resolve what was considered one of the most serious problems in education in Brazil and Espírito Santo: retention of students, particularly in the first grade.

Our theoretical references for the analyses were writings of Mikhail Bakhtin, mainly those that help to consider the education of children and related measures implemented, such as those adopted in Espírito Santo, and help to positively shape children for social and community life.

CRITERIA FOR THE ORGANIZATION OF CLASSES

The formation of homogeneous classes, based on previously established criteria, sought to raise the number of approved students, supposedly by creating conditions for satisfactory learning. In order to classify children in the first grade, and determine which classes they should attend, in Espírito Santo, according to the guidelines of the Secretariat of Education and Culture, the ABC Test by Lourenço Filho was used. In 1961, that guideline, which had been adopted in previous years, was sent to school principals, in Circular No. 2, of January 23, 1961 (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1961), of the Department of Pedagogical Guidelines and Research (Departamento de Orientações e Pesquisas Pedagógicas - Dopp):

1st grade - Beginner students - The selection should be made by applying the ABC Tests, by Lourenço Filho, in upper, average, lower and immature levels classes.

2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th grades - Students will be classified by their average final grade, in strong, average and weak classes.

Whenever possible, those held back will be placed in special classes, in all grades, mainly the 1st grade, which should receive special attention from Your Lordship. (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1961)

The ABC Test was created by Manoel Bergström Lourenço Filho, in 1928. As emphasized by Lourenço Filho in the book entitled Testes ABC: para a verificação da maturidade necessária à aprendizagem da leitura e da escrita (ABC Tests: for the verification of the maturity needed to learn to read and write), republished in 2008 by the National Institute of Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira (Inep), the tests sought “to verify in children who attend primary school the level of maturity required for learning to read and write” (Lourenço Filho, 2008, p. 15) and also allow classifying the children into three groups, namely:

Those who can learn quickly in common teaching conditions, that is, in a single school semester; those who normally are able to learn during the entire year; and finally, the less mature children, who will only be able to grasp reading and writing, in this period, if special attention is dedicated to them, through preparatory exercises, suitable conditions of motivation, or even certain corrective work. (Lourenço Filho, 2008, p. 15)

Thus, the tests not only provide the diagnosis of maturity levels, but also allow forecasting school work, based on a prognosis of the children’s learning abilities. According to this author, the test would classify children as normal, infranormal or supernormal. This classification was used to support the organization of homogeneous classes. For Lourenço Filho (2008), the innovative aspect of his material was the selection process it proposed, compared to the postulate of the new school regarding the rational organization of classes.

Although the author mentioned the formation of three homogeneous groups based on the use of these tests, the Secretariat of Education and Culture guided the formation of four classes defined according to the upper, average, inferior and immature levels. In this way, we can infer that immature children were diagnosed as incapable of learning in one school year, even when special attention was dedicated to them. In such case, they would be placed in special classes or classes with children who had been retained. From the second year on, children were regrouped according to their final grade, that is, those with the best grades remained would be in strong classes, those with average grades in average classes, and those with low grades in weak classes.

From the perspective of the gifted theory, which seeks to explain the causes for school failure according to the individual characteristics of students, the ABC Tests proposed organizational forms of classes, indicating that there would be greater probability of children learning how to read if they were separated into homogeneous classes. “Teachers who know their art know the advantages of working with a homogeneous group, instead of working with a group of children with different aptitudes” (Lourenço Filho, 2008, p. 83). This author understood that failure, or even difficulty in learning, was caused by individual differences that, in turn, were due to the level of maturity of each student and defended the idea that learning should be individualized.

The attempted homogenization of classes was based, as can be noted, on previously established characterizations and definitions of the children, mainly psychological ones. These definitions, seen as truths about the subjects prevented them from going further, beyond the imposed objectives, that is, they established limits for their possibilities of growth. The aesthetic value of our body, both beautiful and ugly features, our abilities and inabilities reach us, shaping our being, through others. As Bakhtin (2003, p. 46) points out: “The various acts of attention, of love and recognition of my value, issued to me by other people and disseminated in my life seem to have sculpted the plastic value of my exterior body”. In contrast, expressions such as infranormal, weak and inferior classes reach the children not as gestures of love, attention and recognition of their value, but as stigmas that produce deep scars that impede, mainly poor children, from going father, from transgressing the limits that the school and life impose on them, negatively shaping the image that they have of themselves.

A letter sent to school principals called attention to the fact that the teaching of weak classes was seen as a threat to a teacher’s career. For this reason, it was recommended that weak classes be taught by teachers who do not need to accumulate more points for career advancement. At that time, productivity, that is, the number of students promoted, accounted as points on the classification for career advancement. With this consideration, the text of the letter emphasized that:

To avoid future complaints or complaints from the class teachers, we suggest that weak classes preferably be entrusted to teachers who are already stable in their position and in the establishment and therefore do not depend on scoring to be tenured or promoted. (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1960)

Law No. 549, of December 7, 1951, applicable in the 1960s, created mechanisms for control of achievement and attendance for career advancement, established parameters that linked the classification in the exams to the higher objective of this law, which was to increase school attendance by teachers and to satisfactory results among students. To obtain a good classification on career advancement competitions, the following element was emphasized: “School achievement, granting two points for a student who passes, adding to the total another two, five, eight or ten points, depending on whether it is a school or class of the 2nd, 3rd, 4th or 5th grade, respectively” (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1951).

The concern for teachers who led the weak classes demonstrates that the Secretariat of Education and Culture and the teachers had little confidence that these classes would have good results and that the children would pass at the end of the year, indicating the perversity of the classification that, previously, condemned many children to failure. Ironically, as written in the correspondence to school directors, the guidelines for the formation of classes sought to:

Benefit the child;

Facilitate the work of the teacher in the class;

Raise the standard of teaching in schools;

Lead teachers to attain better results in school achievement. (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1960)

Bakhtin (2010), upon analyzing how Dostoevsky treated the characters in his novels, created a concept that was central to his work, which is incompleteness, the inconclusiveness of the human being, of subjects. Dostoevsky, like Bakhtin, also had a negative attitude towards the psychology of his time which reified the human soul, causing it humiliation, depriving it of liberty, an inconclusiveness. In contrast to the determinism in some fields of psychology, the “main emphasis of all of Dostoevsky’s work, whether in terms of form, or in terms of the aspect of content, expresses a resistance towards the reification of man, of human relations” (Bakhtin, 2010, p. 71, emphasis by the author). In this way, the opinions of the characters coincide with Dostoyevsky’s own aversion to the psychology of his time, whose determinist system sought to produce a finish and conclusion to subjects regardless of their will. The criteria for organizing school classes, suggested by the Secretariat of Education and Culture, was based on psychological theories that defined children in advance and imposed limits on their opportunities for development, considering levels of maturity determined by the ABC Test.

Later, classes were organized by observing age criterion, since psychology itself, especially genetic psychology, evolved in the direction of determining levels of development according to this factor. As evidenced in Circular No. 61, of 1968 (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1968), maturity tests should be abandoned, and the organization of classes would come to be guided by the chronological age of the children.

EVALUATION OF LEARNING

In the early 1960s, the primary school curriculum in Espírito Santo encompassed the subjects of Vernacular Language, General Knowledge and Mathematics. As the curriculum sought to maintain the uniformity of the knowledge learned, tests also came to be used as a teaching-learning control mechanism to improve the educational performance of children in the first grade. In addition to the orientations for teachers in order to help them issue the tests, a single final exam for each grade was prepared by the Secretariat of Education and Culture and sent to all schools.

Concerning the instructions for the oral reading test, a document entitled Instruções referentes à prova de leitura oral - 1ª série primária [Instructions for the Oral Reading Test - 1st grade] included the following orientation: the test is worth 100 points and the score obtained in oral reading should be added to the average of the written test and divided by two (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1967b). The final result would then be the average of the two tests. In relation to issuing the oral test, everything must be done carefully, according to the following ritual:

II - Issuing the Oral Reading Test.

a) Students will be called, two at a time, in the order in which they are found on the test list. The examiner will give sheet 1 to the first student and sheet 2 to the second.

b) The student will receive the text beforehand, with the examiner first saying: “Read to yourself, very carefully, everything that is written on this sheet (indicate the corresponding sheet to each student); let me know when you are done”.

c) The second student should sit at the back of the room and is called to come up to the examiner when the first student finishes the test.

d) After the first student finishes studying the reading text (maximum time: 10 minutes), the examiner will say: “read, this short story out loud”, - (show it)

e) During the reading, the examiner will not intervene when the student makes an error, only discretely making notations on previously prepared lists, which will facilitate later judging. However, the examiner should encourage the student to continue the reading, if he/she feels that although the student may have stopped, he or she is capable of reading until the end.

f) Once the reading is completed, the examiner will orally ask questions corresponding to the passage read in these instructions and will write on the exam list, whose model we send along with the scores for each student. (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1963, p. 1, our emphasis)

Thus, children would receive a short text, called historieta or brief story, and were given the opportunity to read it silently first, and then read it out loud to the teacher. Thus, the final reading test was based on a short text rather than on words and sentences as proposed at other times by the Secretariat of Education and Culture.

The interim year tests were prepared by the teachers in the schools and underwent analyses by a teacher indicated by the Secretariat of Education and Culture to evaluate the quality of the texts in the tests issued. The result of the analysis was informed to the schools by the Division of Educational Orientation and Research, with indications of the most common mistakes found in the tests.

Excessively long tests;

Questions not related to children’s interests;

Absence of composition exercises;

Absence of a determined scale of difficulties;

Lack of variety in the types of exercises;

Lack of technique in the organization of some of the exercises;

Absence of silent reading. (Espírito Santo, 1963, p. 2)

The analysis of the tests thus indicated an absence of composition exercises, silent reading, and that there were no questions that considered the interests of children. The other aspects indicated concern the technique for preparing the tests and their items. Based on problems with the evaluation tools, teachers were oriented as to the elaboration technique. Thus, upon organizing the tests, teachers should consider:

1 - A rather wide range difficulties, including easy, average and difficult questions. Most of the questions should have average difficulty. There are those who affirm with certainty that a well-dosed test consists of:

10% indispensable issues

15% complementary issues

5% detailed issues

2. a number of questions related to the level of the class:

For the 1 st grade:

VERNACULAR LANGUAGE - 7 questions including:

Silent reading ...................................... (1)

Grammar exercises ............................ (3)

Spelling ........................................................ (1)

Composition ............................................... (1)

Copying of six lines, preferably of printed letters, to be copied with cursive letters............................ (1)”. (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1963, p. 3, emphasis in the original)

In addition to the guidelines for applying the reading test and the preparation of partial tests, official messages were sent to schools that attained satisfactory results, to congratulate them on these results. This is indicated in Circular No. 15, of December 11, 1962, from the Division of Pedagogical Research and Guidance, addressed to the principal of Grupo Escolar Prof. Augusto Luciano.

Upon sending Your Lordship the test results, we would like to express our profuse appreciation, which extends to the entire staff of this establishment, for the work conducted during the school year of 1962.

The Division of Pedagogical Orientation and Research evaluates, through the information received, the work conducted in our schools and recognizes its greatness. The spirit of sacrifice, the idealism that it imbues. We must express our appreciation. (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1962, p. 1)

Nevertheless, there came a time when there was a lack of financial resources to send materials to the schools, including the mailing of the tests prepared by the state Secretariat of Education and Culture. For this reason, it was necessary to authorize the schools to develop final exams as well. Circular No. 16/65, by the Division of Educational Orientation and Research, issued this authorization and determined that the school principal should prepare the test alone or with the teaching staff - with close supervision of the school principal in the latter case. To help organize the tests, the circular suggested documents that provide guidance about the work of formulating tests:

- an insert to “Boletim” [Bulletins] No. 61, which we sent;

- Bulletins No. 8, 30, 36, which contain works related to organizing tests;

- Suggestions of exercises for various grades (Bulletins 51, 52, 53, 54 and 55);

- brochure: “Leia! Isto interessa a você - 1963 [Read, it’s in your own interest].” (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1965)

The indication of guidelines for the formulation of partial and final tests were based on the idea that poorly prepared and weighted evaluation tools could raise the rates of students retained in the first grade.

In general, orientation documents recommended that the questions be related to children’s interests. In this sense, it indicated that: “Care should be taken when selecting the passages for dictation, silent reading, observing if they correspond to the children’s interests. Within this principle it is advisable to abolish the dictations of isolated or excessively long words” (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1965, p. 17-18). About the composition, it should be clarified that all types of “writing [...] involve the formation of sentences, organization of brief stories, narratives, interpretation, notes, letters, official correspondence, etc.” (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1965, p. 18).

Based on the principle that “reading is interpreting”, to evaluate silent reading, a scale of difficulties was offered with a mixture of easy, average and difficult questions, given that the most difficult ones demand greater mental effort by the child, making them tired, which could interfere in the quality of the child’s work, causing false results in their school achievement.

The knowledge required in a final test in the 1st grade by the Secretariat of Education and Culture, was, in a certain way, determined by the literary curriculum as well as the parameters used to consider a student to be literate. A literate student would be one capable of reading a text silently and responding to questions orally or in writing. In addition, the student should conduct grammar exercises, write words or phrases spoken by the teacher, and compose a written text to have the spelling checked. These criteria should be carefully considered at the time of evaluation. Students who do not demonstrate this knowledge in the test would be considered illiterate and would therefore fail.

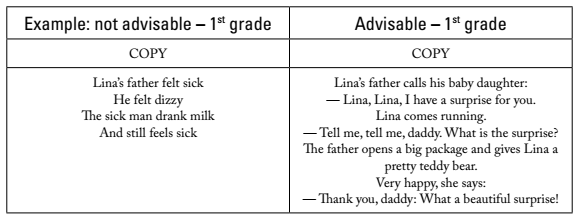

The texts used in the evaluation should be chosen to provide pleasurable reading with positive messages for children. In this sense, guidance was given on what is advisable and unadvisable to include in a text for children, as transcribed in Chart 1.

According to the example found in Chart 1, the text written in the first column is not advisable for a test, while that in the second column is advisable. The former involves the illness of the father of a character named Lina, it is therefore negative and can emotionally influence a child at the time of taking the test and have a negative repercussion on results. The latter has a positive message. This can contribute to the good mood of the students and, thus, to good test results. In addition, the first text is consisted of short sentences, while in the second there is dialog, and therefore the use of punctuation, dashes, etc. Although the second text has different characteristics than the first, we cannot say that it is an utterance, that is, a unit of discursive communication. Created for evaluation purposes only, it has no authorship, does not allow responses nor responds to other texts or questions asked by the children. As Bakhtin (2003, p. 381) points out: “That which does not respond to any questions is meaningless.”

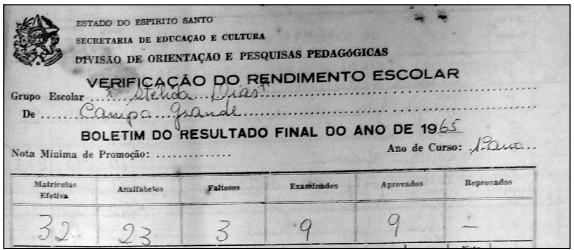

The test results were registered in the final report card, as shown in Figure 1.

As can be seen in the final results bulletin, of the 32 children enrolled, or the actual enrollment, 23 were considered illiterate. Due to the lack of success of the measures adopted to raise the literacy rate, the Secretariat of Education and Culture adopted new more flexible norms for evaluation, according to Resolution of the State Board of Education (CEE), No. 30, of October 12, 1966 (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1966), establishing that the oral test would no longer have an eliminatory character, that is, a student could not fail based on it alone, but the oral test would helpful in determining the final grade. The new criteria involved readings of texts composed of six sentences. Each sentence read with clarity and expressed correctly would be worth two points. The grade for the oral test was added to the average grade obtained on the written test and divided by two. The final grade was thus the average of the grades obtained on the two tests. Since then, the system for promotion and evaluation of school achievement, tests and exams came to be attributions of the schools.

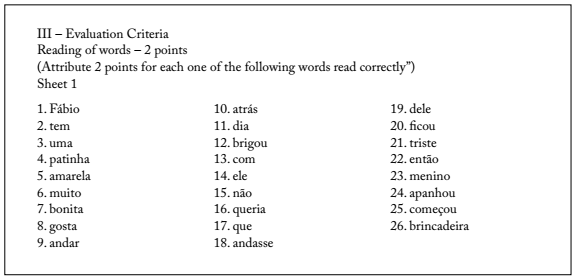

In this way, permission for schools to develop the tests was no longer a contingent situation to become the norm, and schools came to have entire responsibility for the system of promotion and evaluation of school achievement, tests and exams. The following sheet shows one of the ways used to verify performance in oral reading (Figure 2).

*The name of the student was whited-out to maintain privacy. School: Digitalized personal archives.

Figure 2 - Final result sheet for the 1st grade*.

The numbers reveal changes in the results, although the document entitled General Instructions for determining school achievement of the group schools, combined schools and supplementary night courses in Espírito Santo State (1967b) shows that there was no action taken in relation to the pedagogical intervention for serving students who still have not learned to read and write: Students judged unfit by the class teacher, since, if promoted, they will be a problem for the 2nd grade teacher and will not be required to take the exams, being considered as “ILLITERATES” (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1967b, p. 3). In this sense, the orientation continued to be that only students who already knew how to read and write should be enlisted for the exams, because the promotion of the other students would be a problem for the teachers.

Based on the principle that words are “an ideological phenomenon par excellence” (Bakhtin and Volochinov, 2004, p. 36) and that they have the capacity to reflect and refract the conditions of socio-historically production constituted by discourse, we think that the exclusion of illiterate students from the list of those who could be submitted to the reading test is an indication of the way these students and these people were conceived in school and society. In the history of the Brazilian Constitutions themselves and in the relationships that they established with illiterate subjects, we find ways of conceiving these subjects, which obviously had a general repercussion in society.

The first Constitution of 1824, enacted by D. Pedro I, considers Brazilian citizens those born in Brazil, “whether they are ingenuous1, or freed slaves” (Brasil, 1824). In this constitution, no distinction is made between those who are literate or not. In the second constitution, of 1891, the stigma of the illiterate was introduced, establishing that paupers, the illiterate and soldiers could not enlist as voters. The Constitution promulgated in 1934 ratifies this norm, determining that those who could not read and write cannot be enlisted as voters. The Constitution of 1937 recycles the term illiterate. The same term was repeated in the Constitutions of 1946 and 1967. In the current Constitution of 1988, which reinstitutes the democratic state of rights to the country, the vote of the illiterate is optional, that is, it is not necessary/mandatory. The historic thread that guides subjectivities about illiteracy explains how this practice of exclusion of the illiterate, even exclusion from the right to participate in evaluation, was enrooted in the culture of schools, which legitimates social selectivity.

As mentioned, the guidelines of the State Secretariat of Education and Culture on evaluation focused on the more educational and procedural than classificatory aspects. This is seen in the legal recommendations of the Educational System, according to law No. 2,227/67, more precisely in art. 55.

The verification of school achievement will be the responsibility of the teaching establishments, under the guidance of the Secretariat of Education and Culture.

§ 1st In the evaluation of a student’s achievement, consideration will be given to the results attained during the school year, in school activities, ensuring the judgement authority of the teacher.

§ 2nd The evaluation of learning performance will involve appreciation of all the aspects involved in integral education, encompassing not only the evaluation of knowledge, but also that of attitude and habits, skills and forms of behavior consistent with educational purposes. (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1967a)

Thus, evaluative criteria included, in addition to the content studied in school, other aspects, such as attitudes, habits, skills and forms of behavior considered appropriate. The inclusion of elements linked to attitudes and behaviors gives the evaluation a more flexible and subjective character, with the teacher having the responsibility of deciding who should or should not be approved. This allowed decreasing the rate of students who were not promoted after the first grade.

In relation to the oral test, there was a decrease in the level of the reading requirement, to make it easier for children to pass the tests. Teachers should give more points for reading of words and less points for reading sentences. In this new evaluative logic, reading as decoding gained more strength, that is, the code came to be emphasized, despite being “only a technical means of information […] [thus not having] cognitive creative meaning” (Bakhtin, 2003, p. 383). The readings of brief stories included in the previous orientations were substituted by sentences and words. The words included in the oral test were not linked to any context and did not belong to a semantic field and varied from monosyllabic to polysyllabic words, with various tonic accentuations (Figure 3).

The difficulty in the level of reading required on the oral test was associated to what should be understood by subjects considered literate. However, focusing on reading only in words would reduce the difficulty of the reading and made it easier for the students and, thus, improved the statistical rates. In addition to being a pedagogical issue, ideological and political issues are also implicit in evaluation measures, since according to Graff (1994), during the history of literacy education, reading and writing were used as objects of control by the dominant groups. Although literacy education was provided, it was organized, protected and even limited. In this sense, reading as comprehension, in the evaluative perspective of the State Secretariat of Education and Culture, was no longer the central issue in the evaluation process, giving space to a mechanical and decontextualized concept of reading. In addition to the ideological issue raised, pedagogical changes arose, given that the data presented charts before these norms went into effect reveal the high number of failures, not to forget that many students were not even enlisted in the test. Thus, in this context, both form and content changed.

To further reduce the high rates of failure even more, Circular No. 61/68 (Estado do Espírito Santo, 1968), issued by the Division of Primary Education, informed that first grade students should only receive grades from August to December and that the final average would be calculated by adding all the monthly grades and dividing it by five. This guidance was in agreement with the previously determined curricular program for teaching reading and writing. Under the teaching program adopted, by the month of August, all students would already be reading words. In this sense, by only evaluating students after this month, the grades obtained would contribute to a positive result in the final average.

With the enactment of Law No. 5,692/71 (Brasil, 1971), the so-called cumulative evaluation modality to monitor learning in literacy was instituted in Espírito Santo. The teacher training program, known as Evaluation and reinforcement in the teaching-learning process, conducted by the Department of Technical Support of the State Secretariat of Education, explains this modality of evaluation. According to the text entitled “Cummulative Evaluation”, the method should be applied after the introduction of a block of units of study or at the end of a bimonthly period to monitor the learning of the contents worked in these units. The purpose of the adoption of the cumulative evaluation was to provide an objective basis to determine concepts, given that the objective of the formative tests was only to guide teaching and should not be used to assigns concepts. In this way, cumulative evaluation would provide the school system data that would offer a global vision of the process of the various classes, in terms of the objectives of the block of units or bimonthly period.

The instruments that were part of the new evaluation system were spreadsheets intended for student monitoring. In this sense, the referred training program guided the teacher who, before beginning the specific process of teaching reading and writing, had to focus on the evaluation of sensorial aspects. These included:

visual discrimination skills to determine: size, form, color, position, details, graphic signs, depth and visual memories;

auditory discrimination with skills: non-oral sounds, oral sounds, hearing memory;

space-time coordination with the abilities of: analysis and synthesis, and command of corporal scheme, touch, smell and taste, position and direction, time;

motor coordination, with the abilities to: distinguish thick and thin;

oral expression with the abilities to organize ideas, to use language correctly, and to express comprehension of ideas in complete sentences.

To evaluate sensorial skills, the teacher should use the Registration sheet for fundamental skills for the initiation of reading and writing which considered each one of the abilities described.

As the teacher worked with this group of skills, they would proceed to a cumulative preparatory evaluation. Only children who had mastered perceptive and sensorial skills were considered ready to begin the process of learning to read and write. It should be noted that children considered illiterate in the 1960s, according to the evaluation system adopted, did not conduct the final tests or exams. Only those considered ready by the teacher were submitted to these tests. With the cumulative evaluation modality implemented in the 1970s, and from the notion of assumed readiness, children came to be impeded from beginning the process of literacy itself until they demonstrated mastery of the sensory skills seen as requirements for the learning of reading and writing.

As soon as a student met the requirements of readiness to read and write, the teacher should conduct the process of teaching-learning, focused on the objectives to be evaluated and the types of questions specified in the evaluation reports, described in Chart 2.

Source: Digitalized personal archives.

Chart 2 - Objectives of learning and corresponding types of questions.

The learning objectives as well as the types of questions demonstrate the emphasis on reading and writing words whose domain is established through recognition of syllables. As mentioned, the focus on reading and writing words, considered to be an easier activity than writing and reading sentences and texts, can help raise the rates of approval.

To accompany the learning of reading and writing, the teacher would receive a control sheet with a list of objectives to be achieved in the first grade. As a given child would attain them, the teacher would mark it with an X in the direction of the goal and under the student’s name. The objectives proposed are written on the sheet presented in Figure 4.

Source: Digitalized personal archives.

Figure 4 - Control sheet to follow-up the initial reading process.

The objectives described in the control sheet indicate not only what will be evaluated, but also define a gradation of teaching: vowels, gliding vowels, syllables, words formed with the syllables studied, reading of sentences and short texts. The fact that the evaluation comes to give more emphasis to reading and writing words, syllables and sentences stands out. Given the impossibility of creating mechanisms that improve learning, forms are created to facilitate raising the rates of approval by lowering the requirements for progressing in the studies.

Considering that the evaluation determines what was taught in school, we can infer that these objectives shaped the educational practices of teachers. If on the one hand, the formation of classes was based on criteria constructed independently from the subjects, on the other, the objectives described in the control sheet for initial accompaniment of reading are prepared based on a concept of language “as a system of fixed, objective and unquestionable norms” (Bakhtin and Volochinov, 1992, p. 92) that need to be learned by the subjects. In this way, the evaluation is based on the learning of more abstract units of language, like sounds and their respective graphic correspondents, and of syllables. These units do not make sense to the children because, as Bakhtin and Volochinov (1992, p. 92-93) show, what is important for the user of language, and thus for students of written languages “is not the aspect of the linguistic form that, in any case in which it is used, always remains the same […] what is important is that which allows that the linguistic form to compose a given context, that which makes a sign suitable to the conditions of a concrete situation”.

Contradictorily, in schools, by imposition of the educational administrative entities, abstractly conceived children learned an also abstract linguistic system. In this context, with both subjects and language that they learn separated from the concrete reality that constitute them, school failure was inevitable. Nevertheless, theoretical models in the fields of psychology and linguistics, which seek to explain, respectively, subjects and language, based on generalizations that ignore the essential diversity of children and languages, were and are still used to determine how classes are composed and evaluations are designed.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

As pointed out, the objective of this article was to analyze two measures undertaken by the State Secretariat of Education and Culture to improve the rates of approvals in public schools, in Espírito Santo, in the 1960s and 1970s. These are the criteria adopted for the organization of classes and evaluation systems.

In relation to the organization of classes, the criteria adopted followed the levels of maturity of the children, based on the ABC Tests. In terms of the evaluation, it was seen that the system was modified in the two decades also for the purpose of raising approval rates. The oral reading of texts was replaced with the reading of sentences, words and syllables which were central to the tests, thus decreasing approval requirements.

Nevertheless, neither the criteria for formation of classes nor the evaluation systems used in Espírito Santo in the 1960s and 1970s contributed significantly to raising approval rates, for they are based on principles that belittle the abilities of poor children, because it is they who are left behind in public schools. These children lack elements that are essential to survival such as proper food, clothing, medical care and basic sanitation, etc. However, regardless of this condition, educational administrators adopted evaluations and classifications that were extremely harmful to the education of these subjects.

Bakhtin (2003), upon discussing the value that subjects confer to themselves, indicated that this is of a “borrowed nature”, that is, it is based on recognition of the other. As highlighted by the author, acts of recognition penetrate the lives of subjects from a very young age, and thus “children receive the initial definitions of themselves” (Bakhtin, 2003, p. 46) from people they live with. Initially, when there is a propitious family environment, these definitions, always positive, are formulated by the closest relatives (mothers and fathers).

At school, these definitions are promoted in the life of the children by teachers, colleagues and others. As soon as children begin “to see themselves for the first time as if through their mother’s eyes and start talking about themselves in their mother’s volitive-emotional tones” (Bakhtin, 2003, p. 46), in school, children, based on the evaluations that are made of them, also come to think of themselves as the school defines them: weak, inferior, immature… These denominations mark the interior and exterior life of subjects, attributing to them a cognitive value that does not help to positively shape children. As Bakhtin (2003, p. 47) emphasizes, the love of the mother (family) and of other people “from childhood shapes man from the outside throughout his life, gives consistency to his interior body”.

The indifference with which educational administrators create categories to classify and evaluate children create insurmountable obstacles for them to be able to improve their performance in schools. Proof of this, to this day, is that the greatest challenge of schools, society and governments is to guarantee that poor children gain the ability to read and write. This is because scenarios change, years go by, forms of classification acquire more scientific bases, evaluations become more refined, but children continue to be submitted to perverse stigmatizing mechanisms that do not contribute to positively educate them.

REFERENCES

BAKHTIN, M. M. Estética da criação verbal. 4. ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2003. [ Links ]

BAKHTIN, M. M. Estética da criação verbal. 5. ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes , 2010. [ Links ]

BAKHTIN, M. M.; VOLOCHINOV, V. N. Marxismo e filosofia da linguagem. Tradução de Michel Lauhud e Yara Frateschi Vieira. 6. ed. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1992. [ Links ]

BAKHTIN, M. M.; VOLOCHINOV, V. N. Marxismo e filosofia da linguagem: problemas fundamentais do método sociológico em ciência da linguagem. Tradução de Michel Lauhud e Yara Frateschi Vieira. 11. ed. São Paulo: Hucitec , 2004. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 5.692, de 11 de agosto de 1971. Fixa Diretrizes e Bases para o Ensino de 1º e 2º graus e dá outras providências. Brasil, 1971. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Presidência da República. Constituição Política do Império do Brasil, de 25 de março de 1824. Brasil, 1824. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao24.htm . Acesso em: ago. 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Presidência da República. Constituição dos Estados Unidos do Brasil, de 24 de fevereiro de 1891. Brasil, 1891. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao91.htm . Acesso em: ago. 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Presidência da República. Constituição da República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil, de 16 de julho de 1934. Brasil, 1934. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao34.htm . Acesso em: ago. 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Presidência da República. Constituição da República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil, de 10 de novembro de 1937. Brasil, 1937. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao37.htm . Acesso em: ago. 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Presidência da República. Constituição da República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil, de 18 de setembro de 1946. Brasil, 1946. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/consti/1940-1949/constituicao-1946-18-julho-1946-365199-publicacaooriginal-1-pl.html . Acesso em: ago. 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Presidência da República. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil, de 1967. Brasil, 1967. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao67.htm . Acesso em: ago. 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Presidência da República. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil, de 1988. Brasil, 1988. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm . Acesso em: ago. 2019. [ Links ]

CARDOSO, C. J. Cartilha Ada e Edu: produção, difusão e circulação (1977-1985). Cuiabá: EdUFMT, 2011. [ Links ]

DORNFELD, L. M. G. Alfabetização em São Paulo (1970-1985): um estudo das diretrizes curriculares elaboradas pela Secretaria de Estado da Educação. 2013. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação da Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, 2013. [ Links ]

ESTADO DO ESPÍRITO SANTO. Lei 549, de 7 de dezembro de 1951. Vitória, 1951. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www3.al.es.gov.br/Arquivo/Documents/legislacao/html/LO549.html . Acesso em: 12 ago. 2018. [ Links ]

ESTADO DO ESPÍRITO SANTO. Governador (1959-1962: Lindenberg). Mensagem enviada à Assembleia Legislativa do Estado em 15 de março de 1960 [por] Carlos Fernando Monteiro Lindenberg, governador do Estado do Espírito Santo. Vitória, 1960. [ Links ]

ESTADO DO ESPÍRITO SANTO. Secretaria de Estado da Educação e Cultura. Circular nº 2/61. Vitória, 1961. [ Links ]

ESTADO DO ESPÍRITO SANTO. Secretaria de Estado da Educação e Cultura. Circular nº 15/62. Vitória, 1962. [ Links ]

ESTADO DO ESPÍRITO SANTO. Secretaria de Estado da Educação e Cultura. Divisão de Orientação e Pesquisas pedagógicas. Boletim Informativo. Vitória, 1963. [ Links ]

ESTADO DO ESPÍRITO SANTO. Secretaria de Estado da Educação e Cultura. Circular nº 16/65. Vitória, 1965. [ Links ]

ESTADO DO ESPÍRITO SANTO. Conselho Estadual de Educação. Resolução nº 30/66. Vitória, 1966. [ Links ]

ESTADO DO ESPÍRITO SANTO. Lei nº 2.227/67. Normas para o Sistema de Ensino Estadual. Vitória, 1967a. [ Links ]

ESTADO DO ESPÍRITO SANTO. Secretaria de Estado da Educação e Cultura. Instruções Gerais para a apuração do rendimento escolar dos grupos escolares, escolas reunidas e cursos supletivos noturnos do Estado do Espírito Santo. Vitória, 1967b. [ Links ]

ESTADO DO ESPÍRITO SANTO. Secretaria de Estado da Educação e Cultura. Circular nº 61/68. Vitória, 1968. [ Links ]

GRAFF, H. J. Os labirintos da alfabetização: reflexões sobre o passado e o presente da alfabetização. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1994. [ Links ]

LOURENÇO FILHO, M. B. Testes ABC: para a verificação da maturidade necessária à aprendizagem da leitura e da escrita. Brasília: Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira, 2008. [ Links ]

MORTATTI, M. do R. L. Os sentidos da alfabetização (São Paulo: 1876-1994). São Paulo: Ed. Unesp; Conped, 2000. [ Links ]

Received: April 28, 2018; Accepted: April 25, 2019

texto em

texto em