Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação e Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 1517-9702versão On-line ISSN 1678-4634

Educ. Pesqui. vol.50 São Paulo 2024 Epub 31-Dez-2024

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634202450274022por

THEME SECTION: Youth, itineraries and reflexivities

Listening to images in the narrative research with young people*

Ana Karina Brenner is PhD in education and associate professor at the School of Education and the Graduate Program of Education (ProPEd) at the Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ).

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0778-3525

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0778-3525

Paulo Cesar Rodrigues Carrano is PhD in education and associate professor at the School of Education and in the Graduate Program of Education at the Federal Fluminense University (UFF). He is a Productivity scholarship holder at CNPq, level 2.

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3312-1362

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3312-1362

1Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil

2Universidade Federal Fluminense. Niterói, RJ, Brasil

This article presents a set of qualitative methodological tools utilized in a research conducted by listening to young high school students in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Narrative interviews were conducted using photographic devices with a dialogical and reflexive style for the interaction between the interviewers and young interviewees. A discussion group was set up to prospect collective representations of the research´s key topics for which a line of photos was used to cheer the discussion up. Three youths were given a digital photographic camera to take pictures expressing their paths of life. They also made videos which were included in the research movie released in 2018. The photographs taken and interpreted by the young participants allowed to understand processes of subjectivation and interactions taking place in the social contexts of reference, such as those associated with their family life, work, and the school.

Keywords Youth; Photography; Reflexivity; Narratives; Itineraries

Neste artigo apresentamos um conjunto de ferramentas metodológicas qualitativas utilizadas em pesquisa desenvolvida realizando escuta de jovens estudantes de ensino médio na cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Realizamos entrevistas narrativas utilizando dispositivos fotográficos com estilo dialógico e reflexivo de interação entre entrevistadores e jovens entrevistados. Foi realizado um grupo de discussão para sondar representações coletivas sobre temas-chave da pesquisa para o qual utilizou-se de um varal de fotos para animar a discussão. Três jovens receberam máquina fotográfica digital para a produção de fotografias expressivas sobre seus percursos de vida. Também produziram vídeos que compuseram o filme de pesquisa lançado em 2018. As fotografias produzidas e interpretadas pelos jovens permitiram a compreensão sobre processos de subjetivação e interações realizadas em seus contextos sociais de referência, tais como aqueles relacionados com a vida familiar, o trabalho e a escola.

Palavras-chave Juventude; Fotografia; Reflexividade; Narrativas; Itinerários

The research this paper is based on lies in the field of youth studies and is intended to understand processes of individuation of young people whose lives are especially marked by bumpy academic paths – drop-outs and repetition. An effort was made, starting with the association of quantitative and qualitative approaches, to critically list paths of young lives and their singular processes through which they became individuals (Carrano; Marinho; Oliveira, 2015 ; Brenner; Carrano, 2019 , 2023 ) 3 .

Researching young people has required sociological imagination (Mills, 1972) and creativity in order to combine methodological approaches that allow to acknowledge the diversities and inequalities of the juvenile experience, as well as to extrapolate the limits of the interviews having the oral narrative as their only resource. Subjects immersed in contexts of reiterated institutional interviews or controversial topics or also difficult to express in the process of juvenile development might be inadequately addressed with the exclusive use of orality in the interview. Combining research techniques and approaches would reach, more consistently, the multiple forms of interaction among young people in contemporary society. This search presses forward the construction of devices for the use and production of images in the research that will be core analytical element in this work.

The research originating this paper was carried out between 2012 and 2016, between a quantitative stage and two qualitative stages. The qualitative stages resulted in a research film. This article covers some core concepts underpinning the research highlighting the methodological design and tools adopted in its development. The term “devices” is used to talk about the strategies adopted which included the use and production of photos and videos by the research team and also by the young participants. Some of those devices were inspired by previous work experiences with youths, which are also mentioned.

The research

The research methodological design included a survey, applied in 14 high schools in the state school network of the city of Rio de Janeiro. A total of 593 questionnaires were applied to young people, in a non-probabilistic sample, selected on the basis of personal criteria regarding elements that are more representative of the population.

Tabulations and analyses of the survey data gave rise to a list of recurrent profiles of students out of which the young participants were selected – among those who had accepted the invitation to take part in a subsequent stage with interviews – 19 young people for the second (qualitative) phase of the research. The interviews were recorded with quality of audio and image to that, in addition to the content analysis, a video research documentary could be made, released in the first half of 2018. 4 Along the interviews and the decoupage of the material recorded, as well as based on the research team´s meetings to discuss the materials collected, the possibility of having a third phase of the investigation was raised in order to follow on a smaller group of youths in their daily journeys. The interest lay in getting to know and record those significant aspects of their lives narrated in the interviews. Thus, new research strategies and tools were integrated into the process underway, extrapolating the plans initially planned for the investigation.

Following up these youths would require choices since it would be impossible for the team to keep in touch with all 19 young participants interviewed in the qualitative stage. It would be necessary to explain the proposal, to inquire if the youths would be available and willing to have their lives accompanied. A year or so had already passed since the interviews had been conducted. The research team then needed a strategy to re-engage participants, including to obtain their consent, based on quality information, to participate. An e-mail or a phone call did not seem enough to provide this clarification. A discussion group (Weller, 2006 ) looked to be the best way to organize this meeting, dialogue, information, and possibility of selecting “characters” for this new stage of the research which would also be included in the research film. Conducting a discussion group was also important for the research team to introduced issues related to the investigation problem in a perspective of surveying the collective representations of those young people regarding relevant aspects of the trajectories they shared as working-class youths and students in Adult Education (high school level), such as issues associated with school and extra-school learning, working experiences, future expectancies, etc. Out of the 19 interviewees in the first qualitative stage, eight were invited, and five attended. To cheer up the discussion group, since participants had not met before but were known by the research team, a methodological element was adopted to allow interactions and exchanges among the youths by introducing the usual dynamics of a discussion group. We called it “line of photos” and it will be presented later.

The idea was to take an in-depth look into the reflexive possibilities of participants around their life itineraries, the hardships they had gone through and supports (Martuccelli, 2007 ) they had turned to in order to overcome those hardships. For this purpose, methodological devices were utilized to allow the youths to produce narratives drawing from the images presented, and to produce images about themselves, that is, their own records in their everyday activities and representations of their experiences and projections for the future. The notion of projects appeared under the key concept by Alfred Schutz ( 1979 ), as a dynamic field fed by a stock of knowledge that is constantly expanding.

A set of actions sought to ensure the principles ethics in research in the area of Human Sciences. In addition to free informed consent form that was signed by the interviewees and, later on, the accompaniment to their everyday life – described below -, each stage of the research had supplementary actions aimed at enforcing the principles of ethics in research. All of the 19 young interviewees were mailed to their homes an integral copy of their own interview, filmed for the production of the research movie. All youths were invited to watch the final cut of the research film at different hours in order to meet the availability of all of them. Those who could not attend were given a web link to watch the movie – and they would be able to comment on it and, should any significant disagreement arise, parts of the film would be changed before being publicly released. None of the young participants expressed any disagreement whatsoever in relation to the film´s final cut. For the youths – two boys and a girl – who had been accompanied in the everyday routine and who, therefore, appeared more in the film and where more exposed, they had access to the final cut individually.

Along the feedback process with participants regarding the use of their narratives, one of them expressed that he was afraid that he could be depicted in the film since he had revealed sensitive aspects of his life that could be traumatic if publicly exposed. This individual felt relieved when he found out that the final cut had not utilized the moments he considered sensitive. Such revelation confirmed the team´s perception that not everything that a narrator tells within a relationship of trust and dialogue in a research should be used to achieve the purpose of public expression of the research outcome. This ethical care did not prevent, however, the research from revealing the complexity and tension points in the narrative we had been entrusted with. It is necessary to consider that having a research film as one of the academic products in an investigation requires additional elements of care in this constant search to produce knowledge about individuals without exposing them to risks arising from the revelations triggered by the investigation.

The singularization of the sociological analysis

Three significant moments can be highlight in the debate about the socialization of individuals. On the one hand, there is the sociological tradition which, in a holistic perspective, comprehends socialization as a unitary principle. Socialization would lead individuals to adjust to the social rules – the habitus becomes body. In other words, the individuals may be deduced from their position in the social structure. The methodological individualism, in turn, takes the starting point of society being made up of individuals. The collective forms are nothing more than the result of an aggregation of individual actions. On the other hand, in a third moment and under a relational and constructivist view that seeks to acknowledge the plural dimensionality of individuality (Corcuff, 2008 ), one may think of socialization in contexts of social differentiation. Such theoretical-methodological perspective does not disregard the integrating function of socialization but invests in the effort to acknowledge socialization under the key of the complex societies. The individual is not only deduced from their social position but they also take a key role in the making of oneself and in the creation of their own biographic paths.

This imperative of making oneself is characteristic to modern societies or the so-called high modernity of the fourth industrial and technological revolution. What has been called process of singularization has hallmarks, in the sphere of economy, the de-standardization of the Fordist production line and the personalization of the economic activity which yielded practices of consumption and singularities in replacement of the vectors of standardization in the so-called mass consumption society. On this record, the markets endeavor to capture individualized information in order to get to know the consumer as much as possible to foster their fidelity. Data capitalism and the so-called attention economy, ruled by algorithms, are examples of such singularization. For Eugênio Bucci ( 2021 ), we have been living in a super-industry of the imaginary. The capital has transformed the act of looking into work and has hijacked everything that is visible. The economy is now an attention economy. The individual inhabits a world whose de-traditionalization is one of its organizing principles and with the complexities of the networks of social relations which demand the individual to perform a multiplicity of roles all along their biographic journey. Differentiation is a distinctive hallmark of the processes of socialization in the contemporary complex societies in comparison to the simple societies of the past. It is not unusual that socializing, contradictory and conflicting logics clash in the intergenerational dialogue. It is in this sense that the social order becomes more contingent – less determinant – and sociology tends to get more aware of the need to inventory, in the analysis, the complexity of the life of each individual. This is long-term historical process which is related to the loss of tradition as a core element, the complexification of life and social differentiation. Anthony Giddens ( 2002 ) names de-traditionalization the process through which the individuals in urban societies are no longer submitted to the rules of the community and of tradition. Making oneself an individual means to establish sovereignty over oneself and to manage the separation in regard of the others. Alberto Melucci ( 2004 ) argues that autonomy is another name of individuation. In this respect, the search for interpretation of experience is an investigation key in a sociology that is processed on the scale of individuals.

Danilo Martuccelli ( 2010 ) draws attention to the signs of singularization of the social that are expressed on different levels, apart from the economy mentioned before. Society itself sees the decline in the strength of its institutions (Dubet, 2006 ) regarding the bonds and it now perceived as relation between individuals. The conflict of interest is perceived as a relation between people. The political leader, in this context, asserts him or herself in forms of representation by means of identifying with the charismatic individual. In the field of justice, there are also processes of singularization in the quest for equity. Adolescents at schools react to the general rules that does not consider the different personalities that inhabit the institution. Acknowledging individual experiences has become, today, fundamentally important to produce meanings of presence at school for teenagers and youths. Within the family ambience, process that singularize socialibity can also be noted. Grandchildren interact with their grandparents without the mediation of parents by means of communication technologies which autonomize the intergenerational relationships.

There are many examples that can be listed to highlight the hallmarks of singularity in the social relations and in the institutional processes. Anyway, what becomes clear is the need to tackle the sociological challenges involved in the social process of singularization. Thus, it makes sense to assert that the center of gravity in the sociological analysis moves from society, in general, towards the individual and his/her actual experiences. Or, in other words, it is the challenge of seeking to understand social phenomena at the scale of the individuals overcoming the logic of the “social character” in the sociological analysis and look for the singular experience lived as a social position in its multiple crossings of class, race, gender, generation, and living in a territory.

It is necessary, however, to be careful with the risk of reducing the sociological analysis to the level of the individuals, but to conduct it a macrosociology that is developed at the scale of this singularized individuals. The challenge is to explain social processes drawing from individual experiences. This would be, then, a way of describing society which is, ultimately, the structural way of manufacturing individuals.

Danilo Martuccelli ( 2010 ) says, then, we should be careful in order to avoid two analytical imbalances that might compromise the sociological interpretations. The first mismatch comes from looking at individualization losing sight of the historical processes; and the second imbalance would be, reversely, to look just at history as central background, so the singular experiences would be lost. Thus, three significant indications emerge for the analysis of social processes in the view of a singular-oriented macro sociology. The first indication seeks to preserve the bonds between the individual and the structural dimensions; the second is aware of the nature socially and historically located of every individual and, last but not least, the third indication highlights the care that must be taken in order to inventory the work individuals do onto themselves in becoming a subject.

In this last indication lies the sociological imagination (Mills, 1972 ) that may yield methodological arrangements required so that the individuals we seek to get to know will be able to narrate their own experiences. Special emphasis is granted to the narration of the existential ordeals they have to go through and the support they manage to secure in their social milieu. We agree with Castel ( 2010 ) when he says that the supports are the conditions necessary for the individual to lead him or herself as a social actor. It is in this perspective that we must draw attention to the historical dimension of the individual that has, to a great extent, their genealogy crossed by the history of transformation of their existential supports.

Reflexivity at the research encounter

Bauman and May ( 2010 ) argue that thinking sociologically may turn us more sensitive to diversity and incite us to look beyond our immediate life worlds. A way, then, to explore human conditions so far relatively invisible. The anti-fixation power of the sociological thought would expand the reach of the practice of freedom. The condition for being a social actor is to understand the connection between one´s own actions and the social conditions that demarcate our field of action. We can even say, following the mentioned authors, that self-consciousness of oneself in the world, of the thing that determine us, may be the basis to articulate projects of life. In this perspective, we understand that the investigation movement may also be an opportunity to produce reflexive processes with the young individuals who we relate to in the field of research.

Reflexivity is a fundamental characteristic of modernity (Giddens, 2002 ; Melucci, 2004 ). It is intensified insofar as societies become more complex and heterogeneous. Reflexivity takes a decisive role in the process of individuation for young people since it allows them to think about themselves and about their relationships with the others. Such double movement enables them to experience different identities and to produce their own identity processes.

Photo and video devices

The interview process in a dialogical perspective seeks to make “biographical room” (Arfuch, 2010 ) to make the discourse of the other person to arise. The mediation by the imagistic device makes the narrator take the role of a reflexive co-producer as a result of “be teased” by the person who wants to get to know biographic and daily itineraries. A documentary film is, in summary, the process of producing a new reality, that is, the relation between the one who films and the one who narrates. The production of films and the use of reflexive devices were part of the same process of research and dialogue. The production of images and sound to edit the research movie was also a support to the dialogical process of interviews in an effort to overcome methodological limits. Lins ( 2008 , p. 56), analyzing Brazilian contemporary documentaries argues that the notion of device refers to the creation, by the maker, of an artifice or protocol that produces situations to be filmed. For us, devices are also artifices or protocols that produce dialogues and reflexivity about oneself in the subjects of the research.

In our investigation, the use of images as supports to the biographical narration and the representation of daily life was the result of a device of photos and videos that we had introduced in the interview which had the purpose of inciting reflexivity in the process of producing and narrating the image. Thus, what we got were images (photographs and videos) produced in a context of incited reflexivity. The images the youths produced were representations of themselves and of everyday life intentionally changed by the research process. They were not, therefor, the images Martins ( 2008 , p. 53) called “naive photographs of the popular common sense” which do not portray or represent daily life, but rather refer to a naive challenge of everyday activity, its refusal, the refusal of the daily as a moment of work.

Much of what is seen in an image, in addition to the intentions and the significant chances of whoever produced that image, also expresses the experiences, feelings, knowledge, and pre-notions of who is looking at that very picture.

Objects of memory for narrative interviews

Asking the young people to bring objects of memory to anchor their narratives in the interview is inscribed in our methodological framework of producing reflexive devices for the dialogue. By adopting the use of devices in research processes, whatever they might be, we assume that the investigation interferes with the reality we want to comprehend. The device is, then, a creative laboratory where the researching and the researched individuals interact and allow themselves to make subject and object exchanges, especially when using objects, to formulate and answer to investigation questions. In this perspective, the intervention onto the real is undertaken as some teasing that contributes so that the narration and the dialogue become key elements of the investigation process.

The biographical value of an object lies in our capacity to restore the life of the social relations that are intertwined with it. Making memory out of an object involves, therefore, redefining the past through the production of new images and representations of the objects and its networks of relations. In this regard, we agree with Bruno Latour ( 2015 ) who see the object as an actor and mediator of the whole social action, that is, the object is a legitimate social actor; an active element in a perspective that expresses the passage from an intersubjectivity to an intersubjectivity which, according to him, would be more adapted to the human sciences.

The objects of memory were proposed to the youths in conducting the narative interviews that took place in the schools each young participant attended. It was an effort to understand, through the interviews, the juvenile biographic itineraries pay special attention to the territorial dynamics and their incidence onto the school trajectories, as well as other aspect that the scientific literature demonstrate to be crucial in the paths of life and schooling, such as the family strategies to achieve school longevity, the transition to work and the very quality of school life that may mean a factor of attraction or repulsion regarding going on with one´s studies. For the purpose of facilitating the dialogue around these issues, the interviewees were asked at the time of making an appointment, to bring an object which helped tell their story, something significant of what they considered to be important to say about themselves.

All interviewees did so and what drew the research team´s attention, in addition to the diversity of the stories told involving those objects, was that the majority brought photographs, some of them printed, but most of them in their mobile phones.

Having the picture in one´s mobile phone as a support to the narration of oneself says a lot about the presence of the digital photography in today´s visual culture. The facility to produce, edit, store, and share instantly a digital picture explains how it became a way of visual communication that is extremely widespread and accessible. The social media, such as Instagram and Facebook, gave even more emphasis to the digital images which has allowed people to share their lives and create visual narratives by means of photographs. It is no exaggeration to say that digital photography changed our way of seeing and understanding the world and create new forms of expression and visual communication. If on one hand digital photography was absorbed as one of the most significant features of the culture of our time, on the other hand, and especially in the case of young people, it is actually a key to comprehend the ways of being young, on the individual and collective basis.

A research by the Pew Research Center ( 2018 ) show how popular photography is among American youths. Among them, 97% said they had taken pictures with their cell phones. Some common ways young people utilize photography include: a) Sharing through social media: many youths use the social network to share their pictures with friends and followers; b) Personal memories: young people use photography to capture significant moments of their lives and create personal memories; c) Visual communication: photography is often used by the youths as a way to visually communicate with other people; d) Art and creativity: some youths utilize photography as a way of artistic expression and to explore their creativity. Generally speaking, the research suggests that photography plays an important role in life of young people and they use if in diverse and creative manners.

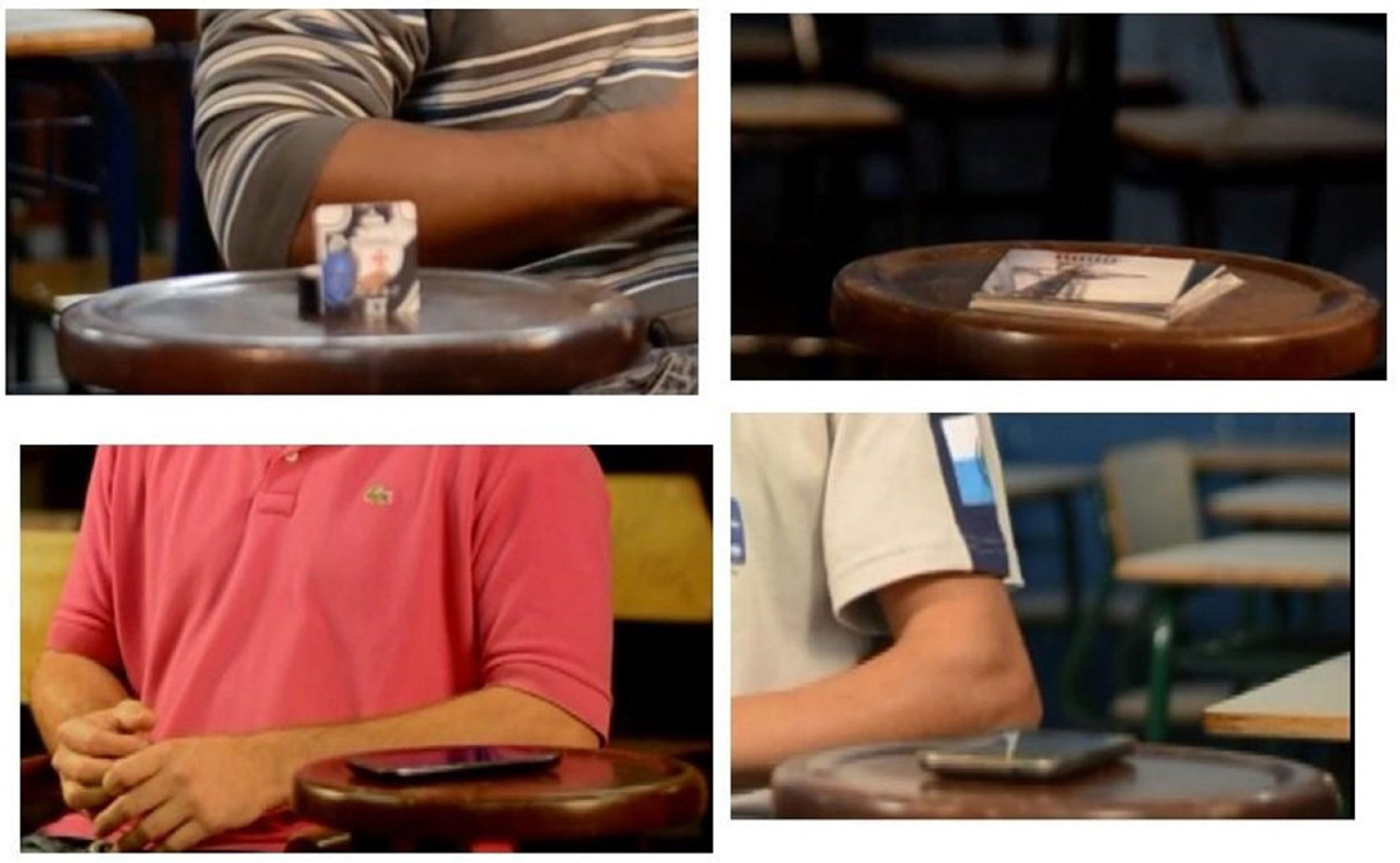

In our research, at the beginning of the interview, the young participants were asked to place the objects on a little stool (image 1) next to their chair, and were told to present the object to the interviewer the moment they thought it was more appropriate.

Some began the talk showing the objects they had brought, other engage them along the interview when the conversation crossed the reference of memory represented by the object in question. One of the interviewees, when asked the first question that incited her to talk about her life, told her name and, with virtually no interference of the interviewer, talked about 12 minutes in a chain of ideas that went from the beginning of the adolescence to that very moment (21 years of age). Her narrative culminates with her handling the three objects of memory she had put on the little stool: she showed her son´s photo to the camera, replaced in her finger the wedding ring she had taken off when she arrived meaning her new marriage and replace on her neck the identification badge which implied she had finally got a formal job. The objects on the stool represented the guiding thread of her narrative, which led to the current moment of her life when the joy expressed by the son represented she had overcome the domestic violence she endured (on the part of her own father and on the part her son´s father), the wedding ring a new possibility of having a happy family life and the identification badge, the moment of reversal of her life represented by job which meant stability, positive novelty and support to changes in life she had been seeking.

Photos of children the boys brought showed the organizing meaning of the biographic itineraries that paternity can provide.

The National Health Research, carried out in 2019, included a special supplement about the life cycle. The study demonstrates that paternity varies according to the age bracket a man is part of. Among males 15 to 29 years old, 19% were fathers, while in 30 to 39 years bracket such percentage reaches 68.9%. The research analyst, Marina Águas, stresses that the reproductive cycle of most men, especially the youngest, may be just starting or be incomplete (IBGE, 2021 ).

Researches on youth still focus almost exclusively on maternity and young people showed that the little incidence of this topic in the studies is a result of this important debate remaining invisible when one considers the individuation processes and their incidence onto the school paths.

The photographs tell what in words, perhaps, would not have the same emotional weight to show the importance of overcoming the challenge of “being a father” in the life of these young males.

Still on paternity, but in the sense of the relationship between the young interviewees and their parents, the suggestion of a youth, when the appointment of his interview was being made with the request of bringing an object of memory, may have created an awkward situation if the holder of a scientific initiation scholarship had not mediated it when getting in contact. The youth asked if he could bring a weapon as his object of memory. Obviously, the reaction of the research team was that it would not be possible to use the object suggested, as it would imply carrying a gun on the way from home to school and also enter the school with a fire weapon. As an alternative, the scholarship holder asked the youth if he could take something that represented the gun which might tell the reasons for using it as an expression of his life story. The youth agreed and ended up bringing an object that did not have to do with the story referred to the weapon, but as the interviewer was aware of it, the interviewer managed to ask why the young man had meant to take a gun as an object of memory. Thus it was possible to learn the young man´s father had been killed when his mother was still pregnant of him; in short, he had never met his father. When he was 14, he found out who the killer was and got a gun. A dilemma arises between fulfilling the desire for revenge or running away somewhere else to restart his life. That is how he gave up the idea of avenging his father´s death and got on a bus towards Rio de Janeiro, leaving his home town in the northeast part of Brazil.

The research team felt a remarkable need not to make pre-judgments and seek to understand the story behind the desire of carrying a gun and introduce it as an object of memory. The representations prevailing in a society like the one in the state of Rio de Janeiro, crossed by the violence of organized crime and the police, would easily consolidate the idea of a young male with a gun is someone involved with crime. However, the reference to the weapon was meant to tell the story of a violence someone had gone through – the fact that he could not get to know his own father, killed before the young man was born -, facing the dilemma and choosing to run away of a new possible life without a shotgun in his hand. The episode of a fire weapon being suggested as an object of memory that lies within the context of the so-called “honor killing”, found in societies where the values of revenge are justified and represent an ethical and cultural code of manliness, as several studies have already demonstrated (Barreira, 2002 , 2008 ; Martins, 1994 ).

The objects of memory allowed, therefore, to reveal significant events in the life of the young interviewees for whom interview scripts alone would hardly manage to reach out.

Line of photographs

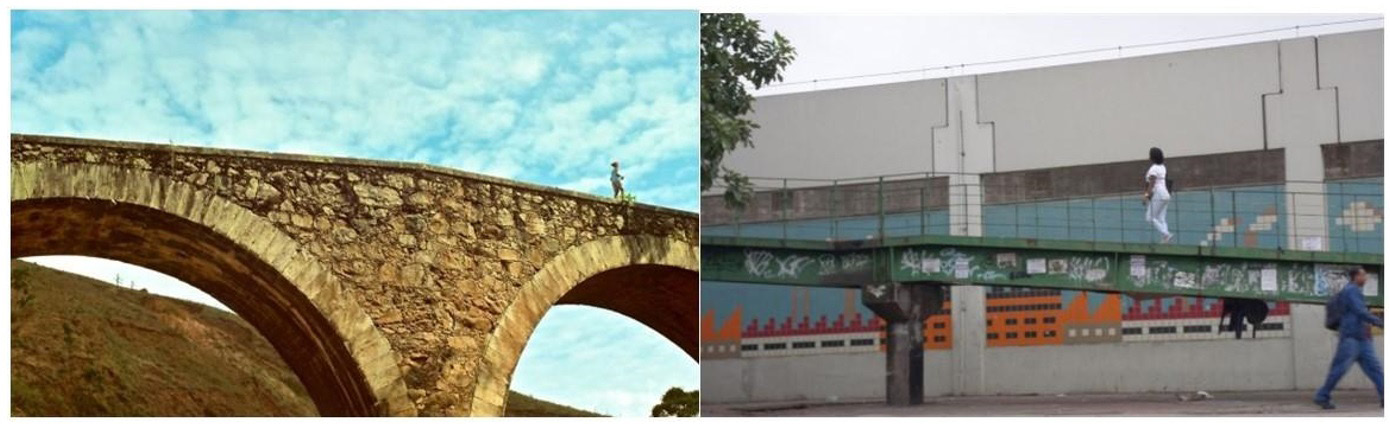

When the discussion group finally took place, over a year had elapsed since the interviews were made, that is, since the research team had met each of the youths in person. An issue concerning how to meet again after so much time and start a conversation that would no longer be on an individual basis, but instead together with other participants in the research. Thought was given regarding how to facilitate the meeting and the integration among the youths, then a line of photographs (see image 2) was set up to trigger the dialogue in the group. The pictures utilized may be defined as concept photos, they did not refer to spaces and places easily identifiable, but a variety of relatively abstract images, representing paths, the passage of time, rubble, details of objects, lights and shadows, etc.

The picture of a landing strip with marks indicating paths passengers must follow when boarding and de-boarding led one of the youths to say how those lines marked on the ground with a blue sky as background made him think of his past-present-future; the marks of what was left behind and the possibilities projected in the horizon. The picture of an ancient stone aqueduct reminded another youth of the crossing everybody has faced along their lives. Leaving a place to go somewhere else or leaving a life project behind in search for a new one, closer or more necessary. The photo also inspired other youths, whose everyday routine was accompanied by the research team, to make his own version – when accomplishing the photographic challenge that will be presented later in this paper – taking a picture of a subway overpass (image 3).

The line of photographs allowed not only a dynamics of encounter but more properly the remembrance of narratives of other kind in relation to those produced in the interviews made in the previous year. And they led on rather fluid and organic way the group of youngsters to the circle where the discussion group gathered. In image 4, the young participants observe the pictures arranged in the line of photos and, teased by research team, they seek to link the photographs to their own biographic itineraries. The reflexive exercises created a field of subjectivation so that the youth could produce and narrate their own mental images around biographic elements of their own experiences and life projects.

The photographic challenge

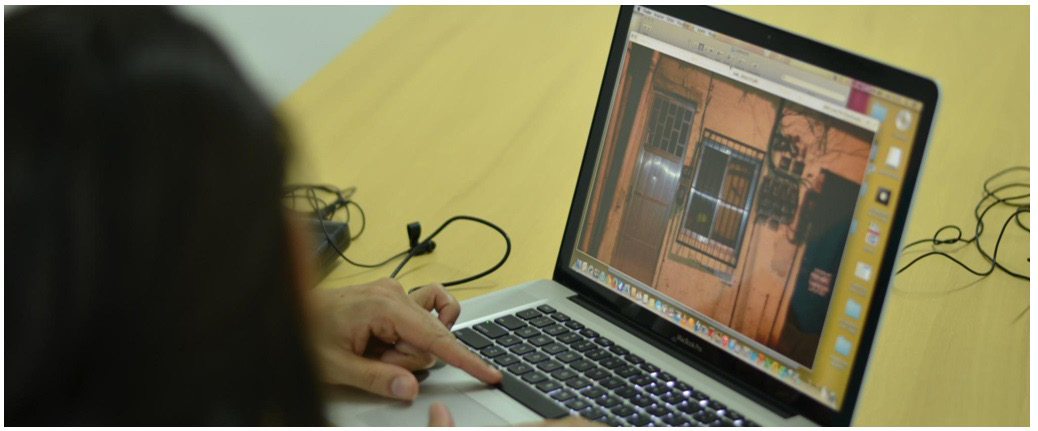

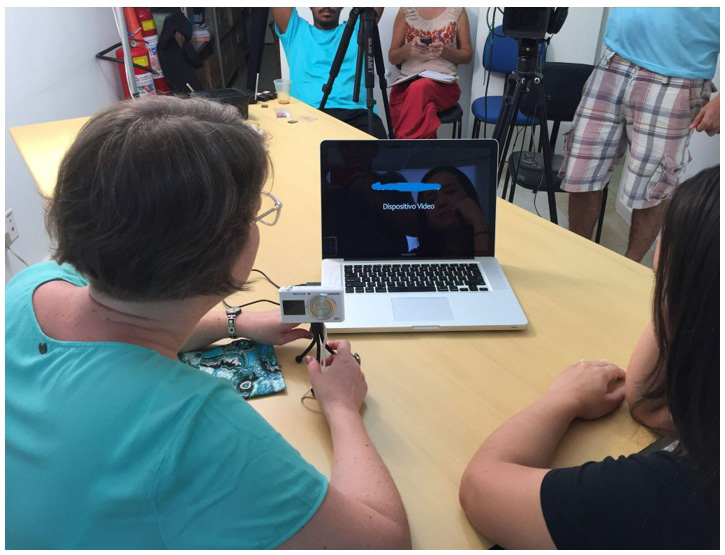

Once the young participants in the second qualitative phase had been defined, when the daily activities indicated by the youths themselves would be accompanied, again the need for supports (changed into devices) stood in the way towards reflexivity. The youths narrated their paths of life, the challenged they had faced, and the ways used to overcome them. With this in mind, a photographic challenge was proposed around two questions: a) could your life be photographed? b) What would you photograph? Each of the three young participants in the stage of the research was given, as a loan, a digital camera. In image 5, the researcher presents to the young participant – both female – the camera she should tackle the challenge of photographically narrating her biographic itinerary. In the background, the picture reveals the shooting team which produced images for the research´s documentary film .

Source: Research archive.

Figure 5 Camera that was lent and the dialogue about the production of a young participant in the research

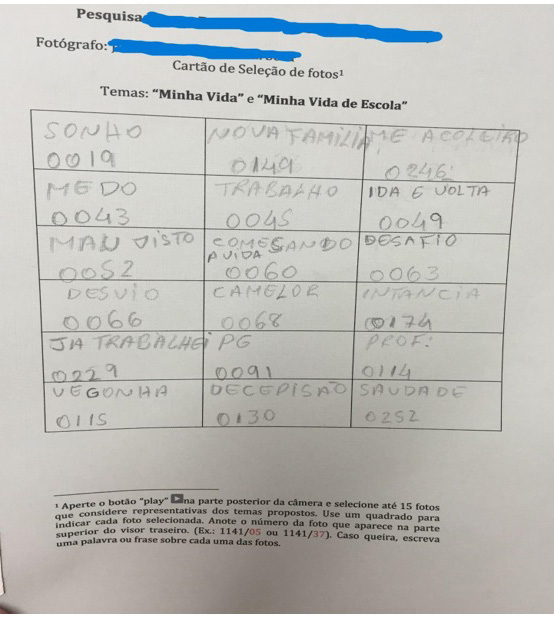

With these questions, a projective exercise was suggested with photographs that might record and describe time-spaces of their daily lives, as well as abstract images that might represent experiences, events, feelings, projections, expectancies of the future. In times of digital cameras, it is possible to record a number of photographs, the main point of the task of reflecting on oneself falls upon the choice of pictures, those which best represent what one intends to show. In this regard, youths could record as many pictures as they wished, but they should choose and provide a title to between 15 and 18 photos to be presented to the research team in a new meeting that would take place within 2 to 4 weeks after the first meeting. A record sheet was designed and presented to the youths to take notes of their photographic production (image 6).

Common sense says that “an image is worth a thousand words”, however, much of what is seen in an explicit picture, in addition to the intentions and the significant hazards of its maker, also includes experiences, feelings, knowledge, and pre-notions of whoever looks at it. The potential meanings that may emerge from a photograph are enhanced by its articulation with the text (written or narrated), especially when the objective is to construct a scientific discourse, as demonstrates Milton Guran ( 2011 ). In this regard, returning with the pictures for a new talk about them was fundamental to understand what and why the young people had made and chosen the photographic items they brought with. In doing so, many topics that had already been addressed in the interviews were resumed with new contents and alternative interpretations by the youths about their own experiences and life itineraries.

Young Maria 5 presented a significant set of images of doors, windows and façades: of the house from where she had been expelled by the father with the consent of her mother, of new façade of her aunt´s house – located in the same plot of the precarious old house where she moved after being kicked out -, of the little room where she lived with the father of her baby before he was born (image 7), of her job which meant a turning point in her life, of the English course she had started recently and which also represented a remarkable achievement.

Young Jhonata recorded some of his fears: the homeless man he sympathized with who represents his fear of him becoming a homeless person too, the fear of abandonment, of poverty. But he also recorded a scene that, when he told, recorded and reproduced it in the research film, results in one of his most riveting passages (Image 8). He photographed subway train doors open with a crowd going in and out of the railcar. When asked about what that picture meant, he told that everybody in it was “filling”, cake filling. The railcar was the cake. And the time to sing “happy birthday to you” was the arrival at his job. It is interesting to notice that the “happy birthday to you” – which represents joy, celebration – was not to arrive at home, the rest after a working day, but rather getting to work. For Jhonata, who since he was a kid had to work to help support the family, always in very precarious types of labor, having a formal job in commerce represented something magnificent: “I went from zero to 10”, said he when he showed the picture of his workplace and his employers. Congratulations for someone who achieved a job and has to get there as “cake filling” in the overcrowded public transportation system.

Video production

The last device utilized in this research was the video, introduced with the use of the same digital camera the youths were given. The video device was intended to proceed with the self-reflexive process by the young participants and, also, to obtain images that might be used in the documentary video which could hardly be shot by a film team without significant interference in the situation being filmed.

Maria filmed the start of a morning. Her son gets dressed to go to school, she fixes her son´s lunch and get ready to go to work. They leave home together saying good-bye to Maria´s partner, stepfather to her son. Out of home on a rainy day, she videotapes the difficulties with the public transport that does not work, the slopes she needs to go down and up when leaving home to get to her kid´s school, ending up in a long sequence of her arrival to her job. At work, she highlights the door which represents the social mobility she achieved with a protected job, she quickly goes past the receptionist and greets her, and finally gets into her work space still empty. She points to the boss´ desk, the co-workers´ and her own, organized with her son´s picture and other objects.

Jhonata films a home moment, watching a children´s movie and having fun with his daughter while his girlfriend was setting up decorations for the birthday party of her stepchild. He also recorded leaving his workplace. He walks through the streets in the center of Rio de Janeiro and talks with the camera getting ahead of the dialogue he would have with the spectators of the researcher movie, as if he was talking directly face-to-face with someone. He points the workers who, just like him, are in a hurry to get back home, the homeless people who are getting settled along the sidewalks at sunset, when he gets to the subway station and hops in the railcar with a sigh of relief because it is “empty” – to the eyes less acquainted with the city´s subway at the rush hour the railcar may seem crowded, but, for Jhonata, a frequent commuter, it is not actually. Holding the camera, he starts telling the people around him that he is filming his way home from work as he is participating in a research conducted by a university and, at one of the stops along his way in the railcar, he stops shooting as if finishing a filmed diary: “tomorrow we´ll have more”, says the young participant and maker of the research movie. His audiovisual production was used to end the research film upon completing expression of the interviews, discussion group, and accompaniment of the youths´ daily lives.

Alexandre filmed moments of his family´s daily gatherings: the mother, siblings, nephews and nieces, all of them in lively conversations in the living room at the home of one of them, while they enjoyed popsicles. He also filmed the neighborhood where he used to live when he was a child, in the city center which he missed a lot after moving to a distant neighborhood far from the center in his early youth. From his former house he could see wonderful nature and quite appreciated sightseeing spots. The landscape described is filmed by Alexandre not as an element of nature, he gives it a symbolic and cultural dimension to what he had lost when the family moved far away from the city center. While in the inner city he had a broad horizon with a vivacious landscape in front of his eyes as well as cultural facilities he could walk to down the hill, in the new house the horizon seemed shortened: houses glued together, the decayed scenery of a peripheral neighborhood too far from the city center, with little urban infrastructure and no cultural places and facilities.

The scenes filmed by the three youths showed moments of their private lives that the research team would hardly be able to shoot, either due the unease of having strangers at home, or due to other reasons that would prevent people from authorizing such audiovisual production greatly invasive to their daily lives. For the researchers, the authorial production seemed to be an alternative that allowed the youths, in reflecting about themselves and their family relationships, to choose both the contents and the form of recording what they wanted to reveal to the researchers and to a broader audience.

Conclusions

The discussion about listening to others in a social research leads to face the challenge of objectivity. We live in a world that is changing quickly with complexities and a wider field of possibilities so that the individual we want to listen to can formulate their own representations of themselves and the world around them. In this context it becomes clear that it is impossible to observe from a distance and outside the relationship with others. Researching under the auspices of reflexivity challenges us to think of multiple notions of relationships that are horizontal e interdependent. From this point of view, it is necessary to say that the social reality that we want to investigate includes those who observe it. The challenge is, to a great extent, to decipher the language revealed in the interactions at play between researchers and the subjects being researched.

Language is understood here in its paradoxical dimension of being simultaneously the constitutive basis of the word and the space to express and redefine it. That is, what someone says is said from a given point of view, but it can only be said because it is in the context of the language itself. There would be, then, some arbitrariness regarding the limits that separate “us” from “them”. The reason for that is that social actors move about, talk, thinks, act while we simply observe them (Melucci, 2005 ).

In the face of such impossibility of observing without any interdependency, there comes the challenge of tensioning the boarders of the relationship between the ones who observe and those being observed in order to understand, beyond the narrative material emerging from the context of the research, what is produced in between.

The theoretical-methodological orientation we have defined as sociology of individuation seeks to start with the experiences of the actors to describe great structural challenges in society. The change in the question as well as the way it is asked opens possibilities to striking responses. It is from the point of view that make use of devices of reflexive listening to incite the situated narration of working-class youths about their life itineraries and their formative paths.

The use of the devices mentioned above has allowed to enhance the reflexive possibilities of the individual participating in the research around their life trajectories, the ordeals experienced and the supports they were able to gather in order to overcome these difficulties.

The use of images in the dialogue with the youths defined two entries. The first one introduced concept-images in the device we have called “line of photos” where pictures previously selected were displayed in order to tease the youths to establish links with their life experiences and expectancies. This device turned out to be appropriate to reinforce the perspective which invited youths to be themselves all the time the interpreters of their own lives. The second entry with imagistic devices took place with the photographic challenge when the young participants were invited to visually surprise the research team with pictures and videos narrating their experiences, daily lives, and projections for the future.

By comparing the productions and outcome of the two latter devices, it was possible to see the best result in terms of self-reflexive process revealed in the photographs. Nevertheless, the videos actually produced images that were significant to the research movie, either because of the peculiar view of each youth on their realities, or due to maintaining the scene lived without the interference of the research team or even due to the exclusive interference of the youth him or herself.

The objects of memory added elements of surprise to the play of the narrative interview. Those youth narrating themselves were give something that only them were aware of, playing with the known script of the interview the interviewers had in their hands. The play of the interview turned out to be more balanced and the narratives took a flowing in the step also defined by the young interviewees.

The title of this article may lead to a inaccurate impression that we are really convinced that it is possible to “listen to” images which would speak for themselves. What we have sought to say is that the images speak through their narrators, whether those who have produced them or those who were affected by them. In the research context, the photographs allowed the young narrators to reveal themselves. In the encounter with the images, they could express what they think, fell and imagine, based on the field of reflexivity on the experiences that the research encounter enabled to happen through a dialogical ground.

REFERENCES

ARFUCH, Leonor. O espaço biográfico: dilemas da subjetividade contemporânea. Tradução: Paloma Vidal. Rio de Janeiro: UERJ, 2010. [ Links ]

BARREIRA, César. Cotidiano despedaçado: cenas de uma violência difusa. São Paulo: Pontes, 2008. [ Links ]

BARREIRA, César. Pistoleiro ou vingador: construção de trajetórias. Sociologias, Porto Alegre, v. 8, dez. 2002. Dossiê Violências, América Latina. [ Links ]

BAUMAN, Zygmunt e MAY, Tim. Aprendendo a pensar com a sociologia. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar, 2010. [ Links ]

BRENNER, Ana Karina; CARRANO, Paulo. Entre o trabalho e a escola: cursos de vida de jovens pobres. Educação Realidade, Porto Alegre, v. 48, e120417, 2023. [ Links ]

BRENNER, Ana Karina; CARRANO, Paulo. Work and schooling in the life course of poor young people in Rio de Janeiro. In: Rausky, M., Chaves, M. (ed.). Living and working in poverty in Latin America. 1. ed. New York: Springer, 2019. p. 99-122. [ Links ]

BUCCI, Eugênio. A superindústria do imaginário: como o capital transformou o olhar em trabalho e se apropriou de tudo que é visível. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2021. [ Links ]

CARRANO, Paulo; MARINHO, Andrea; OLIVEIRA, Viviane. Trajetórias truncadas, trabalho e futuro: jovens fora de série na escola pública de ensino médio. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 41, p. 1439-1454, 2015. [ Links ]

CASTEL, Robert. El ascenso de las incertidumbres: trabajo, protecciones, estatuto del individuo. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2010. [ Links ]

CORCUFF, Philippe. Figuras de la individualidad: de Marx a las sociologías contemporáneas. Cultura y Representaciones Sociales, Mexico, DF, v. 4, n. 4, p. 1-33, 01 mar. 2008. [ Links ]

DUBET, François. El declive de la institución: profesiones, sujetos e individuos en la modernidad. Barcelona: Gedisa, 2006. [ Links ]

GIDDENS, Anthony. Modernidade e identidade. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar 2002. [ Links ]

GURAN, Milton. Considerações sobre a constituição e a utilização de um corpus fotográfico na pesquisa antropológica. Revista Discursos fotográficos, Londrina, v. 7, n. 10, 2011. [ Links ]

IBGE. 64,6% dos homens com 15 anos ou mais de idade já eram pais em 2019. Agência IBGE Notícias, Brasília, DF, 2021. Disponível em: https://censoagro2017.ibge.gov.br/agencia-noticias/2012-agencia-de-noticias/noticias/31446-64-6-dos-homens-com-15-anos-ou-mais-de-idade-ja-eram-pais-em-2019 . Acesso em: 13 mar. 2023. [ Links ]

LATOUR, Bruno. Uma sociologia sem objeto? Observações sobre a interobjetividade. Revista-Valise, Porto Alegre, v. 5, n. 10, p. 165-187, dez. 2015. [ Links ]

LINS, Consuelo. Dispositivo documentais, dispositivos artísticos. In: LINS, Consuelo e MESQUITA, Claudia. Filmar o real: sobre o documentário brasileiro contemporâneo. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar, 2008. p. 56-61. [ Links ]

MARTINS, José de S. O poder do atraso: ensaios de sociologia da história lenta. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1994. [ Links ]

MARTINS, José de Souza. Sociologia da fotografia e da imagem. São Paulo: Contexto, 2008. [ Links ]

MARTUCCELLI, Danilo. Cambio de rumbo: la sociedad a escala del individuo. Santiago de Chile: Lom, 2007. [ Links ]

MARTUCCELLI, Danilo. La individuación como macrosociología de la sociedad singularista. Persona y Sociedad, Santiago de Chile, v. 24, n. 3, p. 9-29, 1 dez. 2010. [ Links ]

MELUCCI, Alberto. O jogo do eu: a mudança de si em uma sociedade global. São Leopoldo: Unisinos, 2004. [ Links ]

MELUCCI, Alberto. Por uma sociologia reflexiva: pesquisa qualitativa e cultura. Petrópolis: Vozes 2005. [ Links ]

MILLS, Charles Wright. A imaginação sociológica. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1972. [ Links ]

PEW RESEARCH CENTER. Teens, Social Media Technology, 2018. Disponível em Disponível em: https://www.pewresearch.org . Acesso em: 14 abr. 2023. [ Links ]

SCHUTZ, Alfred. Fenomenologia e relações sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar, 1979. [ Links ]

WELLER, Wivian. Grupos de discussão na pesquisa com adolescentes e jovens: aportes teórico-metodológicos e análise de uma experiência com o método. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo v. 32, n. 2, p. 241-260, maio/ago. 2006. [ Links ]

3 Data availability: The entire data set supporting the results of this study are available from the institutional drive of the Federal Fluminense University and can be accessed at: https://bit.ly/3xK468R

4 The research documentary film is called “ Fora de Série ” – a play of words meaning both “remarkable or mind-blowing” and “held back after repeating a school year”. It is available (in Portuguese and with subtitles in English) at: www.filmeforadeserie.com

Received: April 18, 2023; Accepted: July 11, 2023

Este é um artigo de acesso aberto distribuído sob os termos de uma Licença Creative Commons

Este é um artigo de acesso aberto distribuído sob os termos de uma Licença Creative Commons

texto em

texto em