INTRODUCTION

In the last twenty years, several viral epidemics have been recorded, such as the SARS-CoV in 2002 and 2003, and the Influenza H1N1 in 20091. The current outbreak of the new coronavirus or SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19 (Corona Virus Disease) was first reported to the World Health Organization (WHO), by China, on December 31, 20192. On January 30, 2020, the WHO Emergency Committee, in turn, declared the disease a global health emergency. Shortly thereafter, on March 11, the number of COVID-19 cases outside China had already increased 13 times and the number of involved countries tripled, leading the WHO to declare a state of global pandemic1.

As for the clinical spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 infection, it is a broad one, ranging from asymptomatic, mild upper respiratory tract disease to severe viral pneumonia with respiratory failure and death3. Tien S. et al., in February 2020, described that the proportion of severe cases to mild cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection was approximately 1:44. A meta-analysis carried out by Wang B. et al., in March 2020, demonstrated that the presence of comorbidities increased the risk of death in patients with COVID-19. The presence of COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease), for instance, is associated with an increased risk of severe symptoms, in addition to hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases and elderly individuals3),(5.

With a chance of severe clinical presentation close to 25%, SARS-CoV-2 infection can lead to health service overload and an increase in the demand for both material and human resources. As it is a highly transmissible disease and caused by exposure, health professionals are more frequently affected, requiring medical leave for treatment and recovery. This fact can lead to a lack of professionals to provide care in the front line, having even more serious impacts on the chaotic scenario of the pandemic. Following the trend of other countries, such as Italy6 and the United States7, to increase the availability of health professionals directly involved in care during the pandemic, the Ministry of Education published Ordinance Number 383 on April 9, 2020 that authorized the early graduation of students from several areas of health, including Medicine8. In the city of Curitiba, four medical schools adhered to the ordinance, with undergraduate students having finished more than 75% of the mandatory internship workload.

In this sense, the effects of anticipating the graduation in a context of a global health crisis, from an emotional point of view, deserve to be evaluated. According to an article published by psychologist Unadkat S., in March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic might increase the pressure on health professionals, since the increase in the demand for work is a significant one9. Flotte TR et. al., 2020, quotes in published article, that the early graduation at the Medical University of Massachusetts, two months before the due date, led new physicians to become involved in a variety of responses to COVID-19 Pandemic, contributing to decrease the workload for residents and medical professors7.

Therefore, the aim of the present article is to carry out a first assessment, still a preliminary one, of the impact of the early graduation of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHODS

This was an observational and cross-sectional study carried out through the application of a questionnaire with 13 questions, five of which used a Likert scale of evaluation, six in the multiple choice format and two descriptive ones, via Google Forms and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Health Sciences Sector of Universidade Federal do Paraná, on August 27, 2020, CAAE 34840820.9.0000.0102.

The questionnaires were applied to medical students, from the universities of Curitiba-PR, who graduated in the first semester of 2020, whose graduation took place two months earlier than the due date because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The collected data were tabulated in an Excel spreadsheet, where the measures of trend and dispersion were calculated, as well as the pie charts were generated.

RESULTS

In total, 113 graduates answered the questionnaire. As for the characteristics of the participants, 72 respondents were females (63.7%) and 41 were males (36.3%). Information regarding age is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Information regarding the participants’ age.

| Age | Mean | Minimum-maximum | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 25.62 | 23-32 | 1.74 |

| Male | 26.58 | 23-41 | 3.28 |

| Total | 25.97 | 23-41 | 2.44 |

Note: age expressed in years.

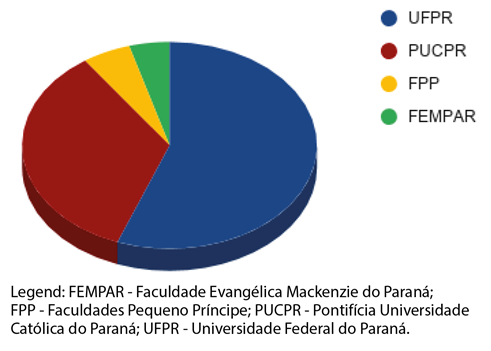

Regarding the institution in which they completed their graduation (Chart 1), most of the interviewees were from Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR), followed by Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná (PUCPR).

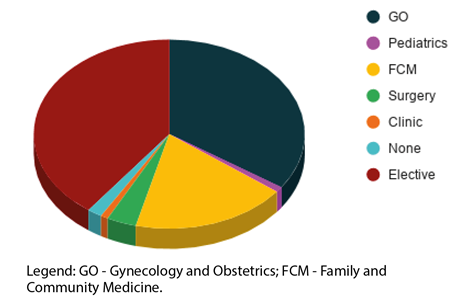

As for the internship that was not attended (or was partially attended) due to the early graduation, most respondents answered that it was the elective internship, followed by the family and community medicine internship (Chart 2).

Regarding the professional performance, 101 participants reported that they are working as physicians (89.4%). Among those who are working, 64 (63.36%) stated that they are working directly with COVID-19 patients. Among the remaining 37, 27 (72.97%), although they are not working directly with it, reported indirect actions in the pandemic (working in places that do not focus on treating COVID-19, but that have received some cases).

As for the workplace, 86.13% are working in the state of Paraná, with 54 (53.5%) in Curitiba and the Metropolitan Region. The state of Santa Catarina comes in second place, with nine responses (8.91%). Other responses included the states of Mato Grosso (2 responses), São Paulo (2 responses) and Rio Grande do Norte (1 response).

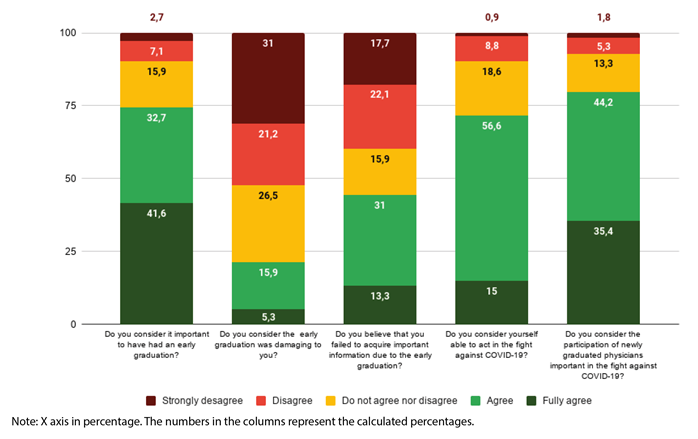

Regarding the importance of having had an early graduation, most participants totally agree or agree, while only 3 participants (2.65%) totally disagree with it (Chart 3).

As for the fact that the participant feels the early graduation was damaging to them, more than half of the interviewees disagree, or completely disagree (Chart 3). However, 43.3% believe that they failed to acquire important information for their education with the early graduation (Chart 3).

Finally, regarding their performance in the pandemic, 79.6% consider the performance of newly graduated doctors in the fight against COVID-19 to be important (Chart 3). Still in this sense, most interviewees consider themselves able to work in the pandemic (Chart 3).

DISCUSSION

In the beginning of April 2020, amid the intensification of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil, Ordinance N. 374 was published by the Ministry of Education, authorizing educational institutions to exceptionally grant an early graduation to students regularly enrolled in the last period of the Medical, Nursing, Pharmacy and Physical Therapy courses, provided that seventy-five percent of the expected workload for the medical internship or supervised internship period had been completed10.

Initially, the students should graduate to work exclusively in the fight against the new coronavirus pandemic - COVID-19. On April 13, however, a new ordinance was published in the Federal Register, revoking the aforementioned ordinance, and revoking the need for working exclusively in the fight against the pandemic after the graduation8. In this sense, it is interesting to highlight what was observed in our research: even though there is no such obligation, most of the participants are in fact working as physicians, directly or indirectly in the fight against the pandemic. Within this context, participants were asked about the importance of the early graduation, and 72.3% of the students agreed or totally agreed with this statement. This possibly shows that new physicians consider their medical performance important amidst the pandemic.

About the place where they are working, it is evident that most of the new graduates are working in the state of Paraná, especially in Curitiba and the Metropolitan Region. This corroborates the local and regional importance these new professionals have had, helping to supply the need created by the pandemic. For instance, in Curitiba alone, until November 13, 2020, 58,633 cases were recorded, 1,553 of which died. In the city, the peak of active cases occurred in late July. At the state level, there are already 225,514 confirmed cases11.

In addition to the increase in demand, another point to be highlighted for the need and importance of new professionals, is the contamination and temporary leave of many health professionals. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) estimates that, by September 2020, approximately 570,000 health professionals had already been infected, with 2,500 deaths due to COVID-19 in the Americas12.

Much has been discussed about training and whether these professionals would be ready to face the pandemic. De Oliveira, et. al.13, asked in their article published in April 2020, if there was a satisfactory progress related to the training of physicians, making them able to meet the health needs of the population at the circumstances in which we are living. The Medical course is an undergraduate course with a minimum of 7,200 hours, with curricula that exceed 8,000 hours, such as the one in the Federal University of Paraná14. With the early graduation, only 5% of the total course load (25% of the internship workload) was missed, and all the theoretical and practical content that is essential for medical training was completed. This is reflected in the response of the graduates about feeling harmed by the early graduation, where 52.2% totally disagreed or disagreed with this statement.

It is also possible to show that 39.8% failed to attend the elective internship, with this type of internship being chosen by the students according to their area of interest, after attending all mandatory internships. When we analyze the large mandatory area that was missed, 34.5% of the respondents answered gynecology and obstetrics, a discipline covered in other phases of the curriculum, such as in Family and Community Medicine or Maternity, previously attended by these students, which favors the positive response as to not being harmed by the early graduation.

Most of them, 71% of the interviewed graduates, said they were able to work in the fight against COVID-19. This can be explained, in addition to the long hours of preparation in medical school, but also because it is a new disease with constant changes in management protocols. The pandemic brought an unprecedented scenario, in which more experienced professionals also had to learn together with the newly graduates, who, because they are still in the training phase, have a greater capacity for assimilation and acceptance of new concepts, which could be considered an advantage.

In the future, perhaps a greater focus on psychological preparation and support for medical students in pandemic situations would have a greater impact than just the knowledge of pathophysiological bases and the treatment of diseases15.

As well stated by Gallagher and Schleyer16, in a recent article dealing with the insecurity and fear of students and newly graduates in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, seeing them willing to work in the presence of such a severe and contagious disease, gives us hope that the future of Medicine is in good hands.

As for limitations, it is noteworthy that our study was performed in only one city and mainly comprised students from only two institutions. It is also important to note that we carried out a cross-sectional study, conducted a few months after graduation. We know that the long-term follow-up of the participants can better elucidate certain issues and generate more objective results in assessing the impact.

CONCLUSION

The present study contributes to demonstrate that the early graduation was successful in its objective of increasing the availability of health professionals directly involved in patient care amidst the pandemic. Moreover, the study also allowed assessing the opinion of students who had an early graduation, who were the ones mostly affected by the measure, but who, according to our research, showed a favorable opinion regarding the early graduation.

texto em

texto em