Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica

versão impressa ISSN 0100-5502versão On-line ISSN 1981-5271

Rev. Bras. Educ. Med. vol.47 no.3 Rio de Janeiro 2023 Epub 31-Jul-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-5271v47.3-2022-0091

REVIEW ARTICLE

The fine line between health promotion and the reproduction of fatphobic speech by doctors

1 Universidade Positivo, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil.

Introduction:

Body weight control is essential for the treatment and prevention of the main comorbidities in the world, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia and obesity. However, medical guidelines regarding weight loss are often not evidence-based or clearly communicated, and they also do not take into account the psychological and social conditions of patients, as dictated by the values of health promotion, but rather, approached in a prejudiced and shallow way. This study seeks to answer the following question: Is the manner physicians deal with their patients’ obesity a way of promoting health or of propagating even more unfavorable clinical outcomes in this population?

Objective:

This study aimed to review the literature regarding medical fatphobia and its impacts on the patient.

Method:

This is an integrative literature review, carried out in January 2022. The data search took place from the year 2007 to January 2022. The following databases were used: SciELO, Lilacs and PubMed. The following descriptors were used in the search for articles: Obesity, Overweight, Social Stigma, Social Discrimination, Bullying, Fatphobia, Weight Bias, Medication Adherence, Therapeutic Alliance, Health Professionals, Binge-Eating Disorder.

Result:

The 16 selected articles were classified according to type of study, year, place, target audience and results, and then critically analyzed.

Conclusion:

Although it is crucial for doctors to warn their patients about weight loss, these guidelines, when made in a prejudiced, rude way and without well-defined goals, make them not interested in taking care of their own health, or even trying to lose weight without professional support. Therefore, instead of fighting obesity, its current management is responsible for aggravating it and even developing other comorbidities, such as depression.

Keywords: Obesity; Social stigma; Therapeutic alliance; Health Promotion

Introdução:

O controle do peso corporal é fundamental para o tratamento e a prevenção das principais comorbidades no mundo, tais como hipertensão, dislipidemia e obesidade. Entretanto, as orientações médicas referentes à perda de peso, muitas vezes, não são baseadas em evidências ou comunicadas de maneira clara, e também não consideram as condições psicológicas e sociais dos pacientes, como ditam os valores da promoção da saúde, mas são abordadas de maneira preconceituosa e rasa. Este estudo busca responder à seguinte questão: “A maneira como os médicos lidam com a obesidade dos seus pacientes é uma forma de promover saúde ou de propagar ainda mais desfechos clínicos desfavoráveis nessa população?”.

Objetivo:

Este estudo teve como objetivo revisar a literatura no que concerne à gordofobia médica e aos seus impactos para o paciente.

Método:

Trata-se de uma revisão de literatura integrativa, realizada em janeiro de 2022. A busca de dados se deu a partir do ano de 2007 até janeiro de 2022. Usaram-se as seguintes bases de dados: SciELO, Lilacs e PubMed. Utilizaram-se, na busca de artigos, os seguintes descritores: obesity, overweight, social stigma, social discrimination, bullying, fatphobia, weight bias, medication adherence, therapeutic alliance, health professionals, binge-eating disorder.

Resultado:

Os 16 artigos selecionados foram classificados segundo tipo de estudo, ano, local, público-alvo e resultados, e, em seguida, analisados de maneira crítica.

Conclusão:

Embora seja crucial os médicos alertarem seus pacientes sobre perda de peso, essas orientações, quando feitas de maneira preconceituosa, grosseira e sem metas bem definidas, fazem com que o paciente se desinteresse em cuidar da própria saúde ou ainda procure perder peso sem apoio profissional. Logo, em vez de combater a obesidade, o atual manejo é responsável por agravá-la e, inclusive, desenvolver outras comorbidades, como a depressão.

Palavras-chave: Obesidade; Estigma Social; Aliança Terapêutica; Promoção da Saúde

INTRODUCTION

It is indisputable that showing the patient how adhering to a balanced diet, performing physical exercises regularly and controlling body weight are fundamental bases for the treatment of many prevalent comorbidities today. For instance, weight loss is associated with good blood pressure (BP) control: the loss of 5.1 kg in body weight reduces, on average, systolic BP by 4.4 mmHg and diastolic BP by 3.6 mmHg1. Additionally, according to the Brazilian Obesity Guideline, an elevated waist circumference (> 80 cm in women and 94 cm in men) is strongly associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, comorbidities that carry a high cardiovascular risk2. However, it is observed that medical schools teach students the sine qua non condition of weight loss as the cure for many illnesses, and yet, there is no correct understanding about how these recommendations should be given to patients3. Articles that analyze this phenomenon state that there are no well-defined plans and goals on weight control, diets and physical activity during an appointment with a fat patient, as these practices were not taught to the students3),(4. Although the National Curriculum Guidelines (DCN) of medical schools emphasize the need for the training of a general practitioner capable of working in a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, critical and humanist way5, these studies highlight the lack of methodologies that instruct students to base their conduct, their diagnoses and their language on respected semiological guidelines and literature. What is observed, according to these analyses, is the reproduction of shallow and offensive speeches in the management of a fat patient, such as the phrases ‘’you are like this because you’re fat’’ and ‘’get thinner and you’ll be better’’, or even, associating any and all comorbidities to one’s weight, without adequate clinical reasoning3. The term “medical fatphobia” was coined precisely to designate this lack of correct and evidence-based guidelines. What for the physician can be a normal behavior regarding the non-drug treatment, which they learned during undergraduate school, for the patient, it is a great offense and a great danger (since, as they do not receive the adequate recommendations about weight loss, they search for radical solutions, such as medications and the so-called miraculous diets)6. Not to mention that the reproduction of these discourses destroys the doctor-patient relationship: the patient stops consulting, as they associate health care with suffering prejudice. Without this relationship, the therapy becomes ineffective, in addition to the fact that a healthy life is impossible when a person suffers discrimination and is in constant hatred of themselves, their body and society3),(6),(7.

This unfounded pathologization of fat bodies becomes more problematic during campaigns to fight obesity, which treat this disease as a worldwide epidemic (a connotation that gives a contagious characteristic and causes panic in the population). Campaigns aimed at health care are necessary, since 96 million people are overweight in Brazil and 40 to 60% of Brazilians have dyslipidemia8. However, these actions only show the exclusive glorification of bodies that fit the currently imposed beauty standards, and not ideal indexes and references values for weight, BP and abdominal circumference, nor concrete actions on how to achieve them. Therefore, this war against obesity can easily become a war against fat people, based on discriminatory actions and judgments, coming from the team that should most welcome and guide them without offending them: the health team3.

According to the First International Conference on Health Promotion, held in Ottawa, Canada, in 1986, health promotion is any transformation of the environment aimed to guarantee the well-being of society, with well-being involving the individuals’ physical, mental and social aspects. This term also encompasses a set of values, such as quality of life, solidarity, citizenship and partnership9. However, although the Ottawa Charter is the foundation for the different health systems worldwide, including the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS, Sistema Único de Saúde)10, studies that analyze medical fatphobia state that the fight against obesity, as it is carried out, is very far from the concept of health promotion 3),(4),(6.

Also in light of the concepts that guide an effective health system, the term therapeutic alliance is present in the main literature on medical propaedeutics. This concept designates the set of conducts and methods that physicians apply in their appointments aiming to encourage the patient to adhere to the treatment, using clear and friendly terms and adapting the therapies according to the patient’s reality and wishes11. This alliance is even related to health promotion, as the partnership with the patient is one of the values mentioned in the Ottawa Charter9. Thus, according to research on fatphobia, as the physicians offend their patients and do not delimit well-defined therapeutic plans, the current fight against obesity also goes against key concepts of semiology3),(6.

That said, to effectively fight obesity, the patient must be treated as a whole, understanding that their illness is related to their biological, psychological and social conditions, without simply reducing them to their abdominal circumference3),(4.

Therefore, this review aims to discuss and analyze how prejudice against fat bodies affects the physical and mental health of overweight people, as well as highlighting the contradictory character that this practice has for health promotion and medical practice.

METHODS

This is an integrative literature review aimed at gathering and synthesizing the content present in articles that address fatphobia and the practice of medical fatphobia. Studies carried out with groups of human beings and literature studies published from 2007 to January 2022 were considered. The study question was: “Is the manner physicians deal with their patients’ obesity a way to promote health or to further propagate unfavorable clinical outcomes in this population?”

The bibliographic search was carried out in the following databases: Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences (LILACS) and PubMed. Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) and Boolean operators (OR or AND) were used in the search for articles: (“Obesity”[Mesh] OR “Overweight”[Mesh]) AND (“Social Stigma”[Mesh] OR “Social Discrimination”[Mesh] OR Bullying[Mesh] OR Fatphobia OR Medical Fatphobia OR Weight Bias[Mesh]) AND (“Medication Adherence”[Mesh] OR “Therapeutic Alliance”[Mesh] OR “therapeutic”[Mesh] OR “Health Professionals”[Mesh]) AND (‘’Mental Health’’[Mesh] OR ‘’Binge-Eating Disorder’’[Mesh]).

The inclusion criteria used in the study were: 1. Scientific articles, national and international, related to the topic of fatphobia, involving human beings and/or literature reviews in Portuguese, English or Spanish, available online as complete and free articles, with access to all audiences, published from 2007 to January 2022. 2. Scientific articles, national and international, related to the topic of medical fatphobia, involving human beings and/or literature reviews in Portuguese, English or Spanish, available online line as complete and free articles, with access to all audiences, published from 2007 to January 2022.

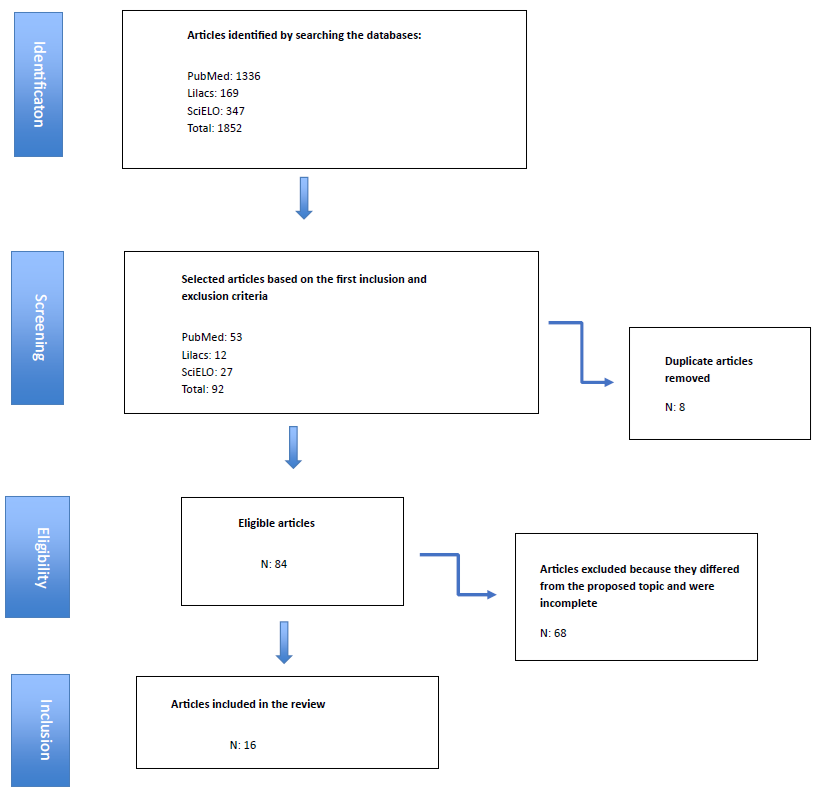

The exclusion criteria were: articles that did not address the proposed topic, as well as incomplete texts, in addition to research focusing on other topics outside the descriptors; doctoral theses; book chapters or undergraduate theses. Duplicate works in databases and those outside the proposed period were also excluded. The flowchart of selected articles is shown in Figure 1.

RESULTS

A total of 1852 articles were found in the following databases: SciELO (n=347), Lilacs (n=169) and PubMed (n=1336). After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, disregarding articles in duplicate, and the reading of full texts, 16 articles were selected, based on the inclusion criteria.

Among the analyzed articles, there was a large number of publications from the United States of America and Brazil, countries that lead the rankings of metabolic diseases related to living conditions and habits2, as well as social discrimination3. It is also noteworthy that most of the analyzed articles were observational studies.

Regarding the epidemiology, it was observed that women were the ones who suffer the most prejudice due to their weight during medical appointments. Additionally, there is a high prevalence of SAH (Systemic Arterial Hypertension) and obesity in the black population, which also constitutes one of the groups that most suffer from fat phobia in medical appointments. It seems, therefore, that discrimination by physicians against fat patients has a more social foundation, of a prejudiced nature, than a scientific one. Data related to the mental health of fat people were also analyzed, highlighting the strong relationship between the practice of fatphobia by the health team and how this leads to a lack of self-esteem in these patients, which also leads to a lack of motivation to seek medical attention and the development of food disorders. Chart 1 describes each article analyzed, based on the type of study and results.

Chart 1 List of selected studies on fatphobia and its consequences, according to authorship, place and year of publication, type of study, target audience and results, from 2007 to January 2022.

| AuthorsRef | Place and year | Study type | Target audience | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paim and Kovaleski3 | Brazil 2020 | Reflection | Health professionals and students | Medical fatphobia may be responsible for the worsening of the lifestyle of fat patients, as they do not receive proper guidance on changing their lifestyle. |

| Sutin and Terracciano.12 | United States 2016 | Cross-sectional observational | Fat people who suffer discrimination because of their weight. | People who suffer from fatphobia tend to develop more eating disorders compared to fat people who do not report suffering prejudiced. |

| Tylka et al.13 | United States2014 | Cross-sectional observational | Physicians and/or medical interns and fat patients | Behind the supposed concern of doctors with the patients’ weight, there is a strong prejudice. |

| Hatzenbuehler and McLaughlin14 | United States 2013 | Cross-sectional observational | Gays, Lesbian and Bisexual Adults | There is a relationship between experiencing social prejudice and developing metabolic disorders such as obesity. It has been shown that gays, lesbians and bisexuals have high cardiovascular risks. |

| Malterud and Ulriksen15 | Norway 2011 | Review article | Health professionals | It is observed that a considerable number of health professionals attribute excess weight exclusively to the lack of physical exercise and a hypercaloric diet, disregarding hormonal and psychosocial factors. |

| Pearl and Schulte16 | United States 2021 | Narrative review | Fat people in social isolation | Overweight people during the pandemic were the ones who suffered the most from binge eating and psychological suffering. However, these people did not receive any guidance on health care. |

| Phelan et al17 | United States 2021 | Cross-sectional observational | Medical students | A questionnaire was applied to students from the first to the fourth year of the course and the same prejudiced content against fat people was observed, both in students at the beginning of the course and at the end. |

| Hurst et al.18 | United States 2021 | Cross-sectional observational | Overweight pregnant women receiving prenatal care | Overweight pregnant women reported not receiving adequate guidance on the importance of weight loss for pregnancy and fetal health. |

| Hübner et al19 | Germany 2016 | Retrospective study | Adults who reported experiencing fatphobia during their childhood and adolescence | Children and adolescents who have been bullied because of their weight go through adulthood with anxiety attacks and lack of self-esteem. |

| Benas and Gibb20 | United States 2006 | Cross-sectional observational | Overweight children and young adults | Children and young adults who are bullied for their weight have higher rates of suicidal ideation and depression. |

| Richard et al.21 | United States 2014 | Cross-sectional observational | Physicians and overweight patients | Physicians, when treating overweight patients, tend to interrupt more appointments and there is no creation of a therapeutic alliance from the patient’s view. In addition, the physical examination for these patients is often uncomfortable. |

| Phelan et al.7 | United States 2015 | Cross-sectional observational | Medical students | A bias about weight is, implicitly and explicitly, widespread In medical schools. That is, just because the patient is overweight, students tend not to establish an adequate bond and approach the appointment in a discriminatory manner. |

| Durso et al.22 | United States 2012 | Cross-sectional observational | Overweight and normal weight people | There is a close relationship between weight discrimination and the development of eating disorders. |

| O´Brien et al.23 | United States 2016 | Cross-sectional observational | Overweight patients undergoing the process of losing weight | Due to the offenses and lack of adequate guidance, the process of changing lifestyle habits is seen as a traumatic process for the patient, who may develop psychological problems in the future due to this process. |

| Murakami and Latner24 | United States 2015 | Cross-sectional observational | Overweight patients undergoing the process of losing weight | Patients who blame themselves for being overweight are the ones with the lowest adherence to the treatment of lifestyle changes and the ones who most resort to over-the-counter diets. |

| Tarozo and Pessa25 | Brazil 2020 | Integrative review | Healthcare professionals and overweight patients | It is crucial for the process of changing the lifestyle of an overweight patient that they have a health team capable of welcoming them, guiding them in a correct and scientific way, and above all, without discrimination and prejudice. Treatment success rates are considerably higher when the professional-patient binomial is empathically established. |

Source: created by the authors.

DISCUSSION

Paim and Kovaleski3) demonstrate in their study that there is a vicious circle regarding the number of obese people and the management of obesity. That happens because doctors, in addition to stigmatizing fat bodies, without considering the individual’s biopsychosocial conditions, do not correctly guide the reason why one should lose weight to reduce cardiovascular events, nor exemplify diet and physical exercise goals, which results in the non-attainment of target blood glucose, weight and BP values. The patient then remains in their state of endocrine disorder and may develop other types of comorbidities due to stigmatization, such as depression, eating and self-image disorders. Hence, the doctor-patient binomial is rarefied, and, consequently, the concept of therapeutic alliance disintegrates, a value that is of the utmost importance to be achieved, especially when related to obesity, since it is a complex comorbidity that involves several areas related to the individual and, therefore, demands comprehensive and concrete care3.

In addition, highlighting this vicious circle, the American study by Sutin and Terracciano12 reports that individuals who suffered medical fatphobia revealed greater food consumption than overweight people who did not suffer such prejudice. That is, when doctors offend their patients, with the unfounded objective of raising awareness, they end up pushing the problem of obesity even further3.

Tylka et al.13 point out that, behind this supposed medical concern with weight to improve health, in fact, there is a strong prejudiced burden that doctors bring to the appointment, arising from an academic background and from a fatphobic society, as well. This fact is evidenced by the fact that medical guidelines are restricted to judgments of appearance, and not practices, diets and well-addressed exercises13.

Hatzenbuehler and McLaughlin14 present epidemiological data on fatphobia. It was found that the black population, women, gays and lesbians are the groups most likely to abandon treatment to control comorbidities related to lifestyle conditions and habits, as well as constitute the groups with the highest risk of developing cardiovascular events. No studies were found related to fatphobia and other groups of the LGBTQIA+ community (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex, asexual). That is, the thesis is highlighted that prejudice with marginalized populations is actually intertwined with these physicians’ desire to reduce the weight of their patients3),(14.

The lack of knowledge about the etiologies of obesity was also the subject of research by Malterud and Ulriksen15. They observed that physicians attribute obesity exclusively to lack of physical exercise and a hypercaloric diet, disregarding genetics, stress, depression, thyroid and adrenal disorders. This study corroborates the study by Tylka et al.13, because when obesity is addressed by physicians, they do not base their arguments on solid analyses and studies, but on shallow, lay opinions, without clinical reasoning13),(15.

More recent studies, which bring the context of the pandemic caused by Sars-Cov-2, during which people were confined to their homes, showed that fat individuals with a predisposition to cardiovascular events were the ones who suffered the most with binge eating and psychological distress during the quarantine. However, this research by Pearl and Schulte16 highlighted that this fact is not taken into account during medical appointments, further fueling the stigma against fat people, as if their state of obesity was solely the result of their actions, disregarding any social and historical contexts.

Fatphobia practiced by doctors starts in medical schools. According to Phelan et al.17, medical students tend to base their clinical conduct much more on the attitudes and reasoning of faculty members than necessarily on guidelines, an approach known as the ‘’hidden curriculum’’. Therefore, neglect related to care of fat people becomes internalized in academic training, and even widely accepted. In this study, a questionnaire was applied to students attending the first and the fourth years, and the same score of prejudice and alienation was observed regarding fat people in the first and fourth years. It was evident that many students believe that fat people are fat due to the individual’s sole responsibility, as a result of the hypercaloric diet alone. That is, even if, theoretically, subjects involving endocrinology and collective health are more consolidated with each year of the course, the stigma is not lost. Hence, the scarcity of undergraduate practices that encourage students to understand the patient in a comprehensive, multidisciplinary and humanitarian way becomes evident17. Although this research is from the United States, based on the Brazilian DCN, there is a marked gap between the objectives of medical schools and what is taught to students. This occurs because, although the guidelines aim at a humanist, generalist and critical academic education5, the students are taught to reproduce shallow, prejudiced speeches and without solid clinical reasoning, capable of understanding the patient in their entirety. These attitudes also deviate from the concept of health promotion3.

In fact, the research by Hurst et al.18 carried out in an obstetrics clinic in the United States, pointed out the lack of bonding and adequate guidance from physicians in the management of overweight pregnant women and/or those with type II Diabetes Mellitus. Pregnant women stated that the health team used “scare tactics” to advise on the harmful effects of poor glycemic control during pregnancy. The team only frightened the patients, in the sense that if the pregnant woman did not lose weight, unfavorable outcomes would occur during pregnancy, such as problems in the amniotic fluid, eclampsia and fetal death. However, there were no explanations or recommendations on the importance of metabolic control during pregnancy. In that same study, the research found that the groups of pregnant women with high BMI, mainly those above 40 kg/m², include not only the greatest cases of breastfeeding problems and hypertensive diseases during pregnancy, but also of postpartum depression and postpartum with poor adherence to maternal health management.

Children and adolescents who suffer prejudice due to their weight are the most refractory in metabolic control during a 2-year follow-up and are also the ones who suffer the most from anxiety attacks, eating disorders and low self-esteem, according to the study by Hübner et al.19. This study also points out that bullying practices in childhood and adolescence, due to one’s weight, can have fatal outcomes in adult life, such as depression, body dysmorphic disorder and suicide.

Benas and Gibb20 and Richard et al.21 quantitatively researched medical appointments with fat patients. It was found that when treating the fat population, physicians tend to interrupt more and listen less to the patient’s speech, compared to patients whose weight is within the standards. The appointment time and the demonstration of respect were also different. And Phelan et al.7 also found that this phenomenon is taught and reproduced implicitly and explicitly at the beginning of undergraduate school, pointing out that there is a bias associated with weight and that it is widespread in medical schools.

From the patient’s point of view, it seems that those who do not accept being overweight are the ones who have more uncontrolled eating, more psychopathologies and less adherence to metabolic control plans. It is also observed that they end up resorting to the so-called miraculous internet diets and over-the-counter weight loss medications. Durso et al.22, O´Brien et al.23 and Murakami and Latner24 emphasize in their studies the importance of the patient’s mental health during any type of treatment. It is crucial that the patient become the protagonist of their physical and mental health, with health professionals being the scientific foundations that guarantee that these goals are achieved4),(19. However, it is clear that, in fact, patients feel guilty about their condition, and seek to lose weight with the sole aim of minimizing the social stigmas they suffer and not to acquire better living conditions. Added to that, they do not receive adequate information from doctors about their health, causing them to seek information in non-scientific databases and submit to dangerous diets19),(20.

Tarozo and Pessa25 state that, given the huge problem involving obesity, as well as the other comorbidities and unfavorable outcomes that occur in obese people, mainly due to the neglect by the health team, it is crucial to reduce health professionals’ prejudices, increase the ability to employ concrete, straightforward, evidence-based goals and plans. Moreover, since the etiologies of obesity are diverse, it is crucial to expand the collaboration of multidisciplinary teams to care for these patients, aiming to cover all levels of care that this comorbidity demands. Without these necessary changes, obesity and its other consequences will continue to increase in society21),(25.

Thus, dealing with obesity in the way it is seen nowadays goes against the main concepts of good medical practices, such as health promotion and the therapeutic alliance. This is because, although these values emphasize that health is only possible when the patient is observed in a universal, humanitarian and scientific way5),(9, the current management of obesity is based on discrimination, the reproduction of shallow discourses without scientific basis and the lack of effective and friendly communication3. And this distortion between theory and practice is precisely responsible for further fueling obesity and even adding new comorbidities, such as depression and binge eating disorders23.

CONCLUSION

Fatphobia, as a whole, is present in the various scenarios of society. Medical students, active professionals and master’s degree students in the health area, are unfortunately included in this group. Medical fatphobia starts in the first years of the course and is perpetuated throughout the others: the fat body is seen as the result of carelessness, the result of a hypercaloric diet. This preconception directly and indirectly affects the quality of life of patients who are outside the stipulated standard, placing them in a vicious circle of permanence in their health status and even developing new comorbidities, such as depression and body image disorders.

It is indisputable that obesity has several drastic consequences for the patient, such as systemic arterial hypertension and cardiovascular disorders. Thus, fighting obesity is promoting health. And health promotion is only effective when the patient is seen as beyond their appearance, considering the social, physical and psychological spheres that led the individual to this circumstance. Also, since there are several factors that lead to obesity, knowing these areas also makes it possible to treat obesity at its root. However, physicians disregard this range of etiologies and associate obesity solely with individual patient attitudes.

And precisely because obesity involves multifactorial etiologies, it is necessary to provide, in addition to humanized evidence-based medical care, also an interprofessional approach. Psychologists, social workers and nutritionists, for instance, should be part of the support team for these patients. Recognizing that multidisciplinary care is the flagship not only for the treatment of obesity, but also of several comorbidities, is to legitimize the DCNs, which emphasize the importance of health promotion based on science, humanity and, above all, teamwork.

It is also unquestionable that, since obesity encompasses several axes, contexts and etiologies, its treatment is a complex one and, therefore, demands a medical figure capable of offering concrete and tangible methods, which are adapted to the patient’s reality, oriented through a clear and friendly language, aiming to make the patient the protagonist of their health. A set of methodologies that encompass the term ‘’therapeutic alliance’’, a concept that, although valuable for propaedeutics and, consequently, for health promotion, is not established in medical appointments. There is a lack of respectful dialogue, as well as tangible and scientific guidelines in the approaches to fat patients. Thus, the doctor-patient binomial is lost, since the patient is not welcomed, nor guided, resorting to other weight loss methods, such as diets obtained from the internet.

And this gap between theories to promote health and what is observed during obesity management, are increasingly prevalent, as they reflect the way physicians were taught during undergraduate school. In many aspects, the application of the hidden curriculum prevails more in medical schools than the encouragement to follow guidelines, semiology literature and clear and friendly communication techniques. And, precisely because they do not follow the main literature, they also do not base their conduct and teachings on the DCNs, which emphasize that effective medical practice is based on a solid, ethical and prejudice-free doctor-patient relationship, on understanding the social context and of the individual and in establishing well-defined therapeutic plans. It is, therefore, contradictory that the principles to promote health are not truly applied in the schools that should train health promoters.

Given this scenario, it is clear how fragile the line is between real health promotion and fatphobia, and that the way obesity is viewed by the medical profession further aggravates the comorbidities observed in obesity cases, due to the neglect that the patient goes through, which leads to an increase in cases of unfavorable outcomes and treatment abandonment. The general objective of this review is to emphasize, and even recall, what the values of efficient medicine that promote health are: embracement, treating and caring based on science, humanity and multidisciplinary care, setting all and any judgment aside.

REFERENCES

1. Barroso W, Rodrigues C, Bortolotto L, Mota-Gomes M, Brandão A, Feitosa A, et al. Diretrizes Brasileiras de Hipertensão Arterial - 2020. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2021;116(3):516-658. [ Links ]

2. Associação Brasileira para o Estudo da Obesidade e da Síndrome Metabólica. Diretrizes Brasileiras de Obesidade. São Paulo: Abeso; c2016 [acesso em 3 mar 2022]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.abeso.org.br/ . [ Links ]

3. Paim M, Kovaleski D. Análise das diretrizes brasileiras de obesidade: patologização do corpo gordo, abordagem focada na perda de peso e gordofobia. Saúde e Soc. 2020;29(1):4-12. [ Links ]

4. Silva M, Schraiber L, Mota A. The concept of health in collective health: contributions from social and historical critique of scientific production. Physis. 2019;29(1):4-7. [ Links ]

5. Brasil. Resolução nº 3, de 20 de junho de 2014. Institui Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do Curso de Graduação em Medicina e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União; 23 jun 2014. Seção 1, p. 8-11. [ Links ]

6. Paim M. Os corpos gordos merecem ser vividos. Estud Fem. 2019;27(1);2-6. [ Links ]

7. Phelan SM, Puhl RM, Burke SE, Hardeman R, Dovidio JF, Nelson DB, et al. The mixed impact of medical school on medical students’ implicit and explicit weight bias. Med Educ. 2015;49(10):983-92. [ Links ]

8. Associação Brasileira para o Estudo da Obesidade e da Síndrome Metabólica. Os últimos números da obesidade no Brasil. São Paulo: Abeso c2020 [acesso em 3 março 2022]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://abeso.org.br/os-ultimos-numeros-da-obesidade-no-bras . [ Links ]

9. Biblioteca Virtual da Saúde do Ministério da Saúde. Carta de Ottawa, primeira conferência internacional sobre promoção a saúde. BVSMS; c2007 [acesso em 6 jul 2022]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/carta_ottawa.pdf . [ Links ]

10. Giovanella L, Mendonça MHM, Buss PM, Fleury S, Gadelha CAG, Galvão LAC, et al. De Alma-Ata a Astana. Atenção primária à saúde e sistemas universais de saúde: compromisso indissociável e direito humano fundamental. Cad Saude Publica. 2019;35(3):1-5 [ Links ]

11. Porto CC. Aliança terapêutica, decisão compartilhada e parceria na cura. Academia de Medicina; 16 jul 2018 [acesso em 3 mar 2022]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.academiademedicina.com.br/genmedicina/alianca-terapeutica-decisao-compartilhada-e-parceria-na-cura . [ Links ]

12. Sutin A, Robinson E, Daly M, Terracciano A. Weight discrimination and unhealthy eating-related behaviors. Appetite. 2016;102:83-9. [ Links ]

13. Tylka TL, Annunziato RA, Burgard D, Daníelsdóttir S, Shuman E, Davis C, et al. The weight-inclusive versus weight-normative approach to health: evaluating the evidence for prioritizing well-being over weight loss. J Obes. 2014;2014(1):1-18. [ Links ]

14. Hatzenbuehler L, McLaughlin A. Structural stigma and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis reactivity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Ann Behav Med. 2013;(47):39-47 [ Links ]

15. Malterud K, Ulriksen K. Obesity, stigma, and responsibility in health care: a synthesis of qualitative studies. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being. 2011;6(4):1-8. . [ Links ]

16. Pearl R, Schulte E. Weight bias during the Covid-19 pandemic. Curr Obes Rep. 2021;10(2):181-90. [ Links ]

17. Phelan S, Puhl R, Burgess D, Natt N, Mundi M, Miller N, et al. The role of weight bias and role-modeling in medical students’ patient-centered communication with higher weight standardized patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(8):1962-9. [ Links ]

18. Hurst D, Schmuhl N, Voils C, Antony K. Prenatal care experiences among pregnant women with obesity in Wisconsin, United States: a qualitative quality improvement assessment. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):2-10. [ Links ]

19. Hübner C, Baldofski S, Crosby R, Müller A, Zwaan M de, Hilbert A. Weight-related teasing and non-normative eating behaviors as predictors of weight loss maintenance. A longitudinal mediation analysis. Appetite . 2016;102:25-31. [ Links ]

20. Benas J, Gibb B. Weight-related teasing, dysfunctional cognitions, and symptoms of depression and eating disturbances. Cognit Ther Res. 2006;32(2):143-60. [ Links ]

21. Richard P, Ferguson C, Lara A, Leonard J, Younis M. Disparities in physician-patient communication by obesity status. Inquiry. 2014;51(1):2-7. . [ Links ]

22. Durso L, Latner J, Hayashi K. Perceived discrimination is associated with binge eating in a community sample of non-overweight, overweight, and obese adults. Obes Facts. 2012;5(6):869-80. [ Links ]

23. O’Brien K, Latner J, Puhl R, Vartanian L, Giles C, Griva K, et al. The relationship between weight stigma and eating behavior is explained by weight bias internalization and psychological distress. Appetite . 2016;102:70-6. [ Links ]

24. Murakami J, Latner J. Weight acceptance versus body dissatisfaction: effects on stigma, perceived self-esteem, and perceived psychopathology. Eat Behav. 2015;19:163-7. [ Links ]

25. Tarozo M, Pessa R. Impacto das consequências psicossociais do estigma do peso no tratamento da obesidade: uma revisão integrativa da literatura. Psicol Ciênc Prof. 2020;40:1-12. [ Links ]

Received: March 28, 2022; Accepted: May 22, 2023

texto em

texto em