Luiz Damasco Penna had a significant performance in the school inspection service of the State of São Paulo, working as a school inspector in the period from 1928 to 1932 and as an education commissioner between 1932 and 1959. In his long career in the Paulista public school, photography followed the family and professional life of this educator. For this, leafing through the photo albums pages that he carefully collected and organized along his life consists in a pleasured experience and, instigating at the same time, specially in respect to his professional trajectory, as some albums have more than five hundred pictures related to the Paulista primary education, either images that depict the inspection exercise or those regarding different aspects of the school culture. Consequently, each photo gives rise to memories and representations, which allows the image reader to wonder about ways of being, representing, thinking the school, and professional experience in the education field.

This text objective is to analyze memories and representations of school inspection in the state of São Paulo upon photography. The study focuses a series of 566 images related to the professional career of Luiz Damasco Penna, since his graduation as a Normal school teacher, involving his work as a school inspector and commissioner in the region of Guaratinguetá and Santos, from 1928 to 1959, inserted in seven albums of family photographs. The first part of the text is about the school inspection system of the State of São Paulo, highlighting the inspectors’ and commissioners’ attributions to outline the work field of these public education administrators. In the sequence, it reconstitutes in a summary form the professional trajectory of professor Luiz Damasco Penna, highlighting his performance in the Paulista education. The second part puts into discussion memories and representations of the school inspection service in images, considering three dimensions of this activity: a) Travelling to visit schools; b) Monitoring the school network; c) Participation in ceremonies and solemnities.

1- School Inspection in the State of São Paulo

Paulo and Warde (2013), in a very appropriate form, affirm that the school inspection service, created in the São Paulo Province in middles of the nineteenth century, was conceived as a result of the primary instruction institutionalization. Initially, this service of inspecting and controlling schools and first-letters-teachers was associated with the municipal inspection in charge of inspectors with no experience in teaching and with no technical and pedagogical qualification.

In the public instruction reform carried out in State of São Paulo at the beginning of the republican regime, school inspection and supervision were refurbished, and inspection assumed the role of organizer of the school network. As Mitrulis affirms, “between its date of creation, in 1846, and the beginning of the twentieth decade, the State School Inspection alternated the organization structures, in commissions or individual, always in cooperation with municipal powers”. (1993, p. 136).

In 1920, the reform of the public instruction (Law no. 1750 of December 8, 1920), named Sampaio Dória’s Reform, introduced significant modifications in the school inspection service, whose role was the renovation of the primary school system, emphasizing the technical-pedagogical character, besides the administrative one. Viewing the decentralization of school administration, it created 15 local education offices, extended the number of inspectors to 35, and replaced municipal inspectors by inspection auxiliaries (MARTELLI, 1972; LIGEIRO, 2014). However, the 1925 public instruction reform (Decree no. 3.858, of Jun 11, 1925) rearranged São Paulo school inspection system by eliminating local education offices and creating new jobs: five general inspectors, six specialized inspectors, 50 district inspectors, and inspector auxiliaries.

In 1930, the local education office was re-established in the State of São Paulo. The district inspectors remained, as well as the general inspector, now denominated regional school commissioner, who became a resident in the seat of the education office, becoming a liaison agent between district inspectors and the central administration. Through the Education Code of 1933 (Decree no. 5.844, of April 21, 1933), the State of São Paulo was divided into 21 school sections, an education office by region. 72 school inspectors were responsible for technological and administrative duties, whose attributions were: support and make the law and regulations to be obeyed, visit establishments to inspect them in relation to instruction technique and efficiency, repute, and assiduity of teachers, discipline, and hygiene of students; to orient principals and teachers in the educational work, stimulating and assisting them in the teaching methods and processes, as well as suggesting or making demonstrations and experiences; holding, at least two times a year, in each municipality, the teachers' monthly meeting of isolated primary schools; to realize final exams in isolated primary schools under his inspection; to render account to the regional commissioner, each week, of the work done, with detailed reports of the script followed and of the expenses made; to realize investigations, by determination of the regional commissioner; to apply or propose the application of penalties. (SÃO PAULO, 1933).

According to this legislation, school commissioners, subordinated to the General Director of the Department of Education, were responsible for school works in their respective regions. The commissioner was appointed by the governor and chosen within school inspectors who had at least 400 days of performance in this activity. It competed to these professionals the following attributions: to execute and make prevail laws, regulations, and determinations of the General Director of the Department of Education; to distribute equitably reglementary services and inspection works to school inspectors; to visit and supervise all educational establishments subordinated to the Department of Education; to deliver to the Department of Education, until the 10th of each month, the monthly inspection plan and the report of the expenses made; to propose to the General Director of the Education Department the creation, localization, transference, conversion, suspension and suppression of schools or educational establishments; to meet annually principals of local graded primary schools to orient them about the service and to determine investigations, propositions of processes instauration, application or proposal of disciplinary penalties, within other activities. (SÃO PAULO, 1933).2

Despite the improvement of the school inspection service implemented in the early 1930s, the situation of the primary instruction administration was considered deficient by educational authorities, as it is possible to verify in the State of São Paulo Teaching Yearbook of 1935-1936, in which Almeida Junior, general director of the Department of Education, pointed out many of these matters, like the necessity of increasing the number of people to the internal service of the offices and a solution to the inadequate facilities of most offices that operated in rooms of school buildings. The director also mentioned the necessity to increase expedient funds addressed to these repartitions. For Almeida Junior, one of the biggest embarrassments of the inspector's activity was the "advance" for travel expenses.

Those who can pay from their pocket, they do it and report the expenses. However, they are an exception. It is necessary a measure from the part of the Treasure to quickly transfer the advances, month to month, starting from January so that it does not occur, as frequent, inactive inspectors by lack of funds. (SÃO PAULO, [1937], p. 96).3

In consonance with the position of the general director, many school commissioners highlighted the precarious work conditions of inspectors. The opinion of professor Onofre de Arruda Penteado, of the Santa Cruz do Rio Pardo Office, registered in the same Yearbook, pictures well the content of the criticisms in vogue:

A wandering Jew, always in a hurry, afflicted to arrive in time and hour, with no chance to read, study, meditate, orient. His bureaucratic job is so big, his district so large, as large as the number of maps, guide plans, papers, reports that he has to organize. To all that, add the time spent in traveling, and to sleep out and eat out of time. In this bustle, unavoidably, disregard and no knowledge, no can be doing, for lack of time, of new theories that daily emerge in terms of education. Bureaucratization of body and soul Annulment. Automatism. (SÃO PAULO, [1937], p. 81)

It is a fact that the increase in the number of school offices and inspectors did not follow the expansion rhythm of primary and Normal instruction in the Paulista territory. In the 1950s, in front of the elementary public-school renovation movement, although the inspection service was convoked to perform as an agent of the educational renovation, inspectors became a target of forceful criticisms, especially for the monitoring and police function. In the 1960, the creation of the Pedagogical Orientation Service (SOP) in the State Department of Education and its regions (SEROPs) was the sign of radical transformations in the inspection service that would follow in the 1970s. As states Ligeiro (2014), this transformation occurred in 1974, when it was instituted the Statute of the Public Education Service of the 1st and 2nd grades of the State of São Paulo, which replaced the position of school inspector by the pedagogical supervisor (Complementary Law no. 114, of November 13, 1974).

1.1-Luiz Damasco Penna and his photograph albums

Luiz Damasco Penna had a typical career trajectory of a school administrator of the State of São Paulo of the first half of the twentieth century.4 Coming from a vigorous and innovatory education in the Normal School of the Praça da República (marked by Caetano de Campos and Oscar Thompson), he was one of the big diffusers of their teachings. At the administration of the Paulista education, he revealed himself as an intellectual, a critical collaborator, respectful of the orientations and reforms developed by the Paulista influential figures. These significant reformers and thinkers as Sampaio Dória, João Toledo, and Lourenço Filho appear not only in his reports but also in his photo albums.5

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photo albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Picture 1 Portraits of Luiz Damasco Penna

He took his degree in 1916 as an elementary teacher and begun his peregrination by different regions of the interior of the State of São Paulo that were under exploration. A quick vision of the problems of rural education in these regions can be read in Pereira (2013). His performance in the Paulista coast occurred in 1928 when he was a district inspector at São Sebastião, and mainly in the period from February 4, 1932, to the year of 1959, as a Regional Commissioner of Santos Education.6

Table 1 Professor Luiz Damasco Penna’s career until his retirement.

| Activity | Local | Dat3 |

|---|---|---|

| Student | Escola Normal da Praça em São Paulo | 1913-1916 |

| Teacher | Escola Retiro em Redenção da Serra | 1917 |

| School Principal | Buquira | 04/20/1920 |

| School Principal | Itaporanga | 1921 |

| School Principal | Catanduva | 02/26/1922 |

| School Principal | Monte Alto | 1923 |

| District Inspector | S. Sebastião | 02/05/1928 |

| District Inspector | Piratininga | 03/08/1929 |

| District Inspector | S. José do Rio Pardo | 01/10/1931 |

| Education Commissioner | Guaratinguetá | 01/24/1932 |

| Education Commissioner | Santos | 04/02/1932 a 1959 |

Source: PASQUARELLI, Silvio Luiz Santiago. Dissertação de Mestrado Educação, 2012. Author: Maria Apparecida Franco Pereira.

The career of Luiz Damasco Penna in the State administrative structure can be resumed in the following functions: teacher (1917-1920); school principal (1920-1927); district inspector (1928-1931) and education commissioner (1932-1959). He worked in many regions of the State interior before establishing his long trajectory in the Paulista coast. During his professional performance, he lived for many times in hotels, travelled to other regions by horse, boat, train, and car. He coordinated, or participated, in meetings of principals, inspectors, teachers, to discuss administrative matters, learning methods and sanitary questions. He also participated in national educational congresses, held in many regions of the country.

Penna's career passed in a time where the State of São Paulo was under rapid development concerning the coffee agro-exportation economy, and the interior conquered in the effervescent pioneer fronts. As they would go further in the hinterland, the contours of an intensive rural life were gaining form. This economy attracted a population each time bigger, the desire of improving the living conditions, including the benefits of school education. The Paulista population was 873.534 inhabitants in 1872 (before the great migration), growing to 2.282.279 in 1900, to 4.592.188 in 1920. In 1937, it was 6.961.740 inhabitants (BARROS, 1938, p. 94). During this coffee economy progress, many urban centers emerged, some considered as real capitals in their regions.

The area of the Education Office of Santos where Luiz Damasco Penna dedicated the largest share of his life in public administration was the Paulista Coast, the land between Ubatuba in the North and Cananéia in the South, which is subdivided into Litoral Norte, Baixada Santista and Litoral Sul (plus the Vale do Ribeira that reaches the hinterland).7 The coast of São Paulo had specific socioeconomic aspects: ancient stages of development throughout the centuries marked by the pursuit of gold and rice cultivation in the far south; spirits manufacture in the North; and, along the whole coast the banana economy, the subsistence agriculture and fishing, which gave the region a slow boost. People far from the urban centers in the riverside and coastal areas lived sparse and isolated, needing school to reach civilization and progress. These areas that experienced in the first half of the twentieth century the absence of railways and roads, depended on river transports and dirt roads walk. (PEREIRA, 2010, p.186-191).

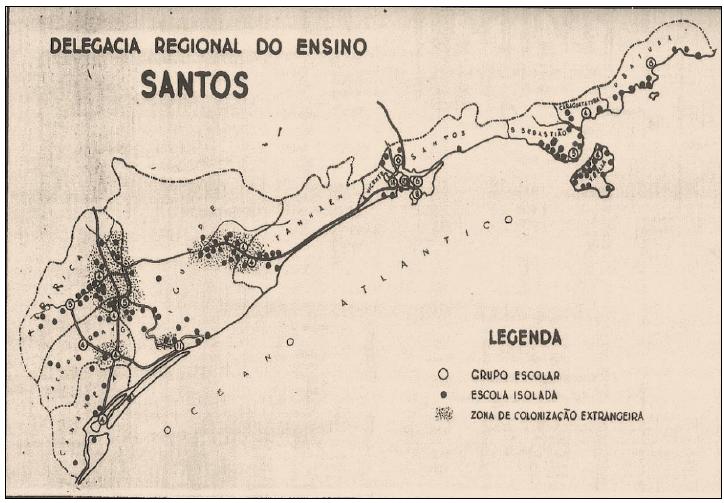

Source: Educational Yearbook of the State of São Paulo, 1935-1936, p. 81

Picture 2 Map of the School Region of Santos

The Education Office of Santos, where Luiz Damasco Penna held the office of education commissioner for 27 years, was constituted of five school districts, composed in different ways: Municipality of Santos; Municipality of Santos and São Vicente; Municipality of Santos, Itanhaém and Iguape; Municipalities of Iguape, Cananéia, Jacupiranga and Xiririca; and Municipalities of São Sebastião, Vila Bela, Ubatuba and Caraguatatuba, as picture 2 shows. It consisted, though, in a coast school zone characterized by the dispersion of elementary schools. As Denise Silva well said:

Though it did not include a significant number of school unities (nearly 402 schools in 1936), the education office of Santos was the second largest one in the percentage of attendance to the population, receiving about 60% of the children. To have more than half of the children in a region where the big part of school establishments, about 80%, were isolated primary schools, placed the regional office of Santos in evidence, which made of it a real “archipelago” of “islands of knowledge”. (2004, p. 45).

In this school zone, the education commissioner and school inspectors faced many problems as the distance of school establishments, the small number of inspectors, the fragility of roads and transportation means, and the isolation of schools in many locations. It was in this peculiar socio-cultural, educational and geographical context that Luiz Damasco Penna performed his activities of regional leadership of the public education administration in the Paulista coast.

1.2-The documentary collection

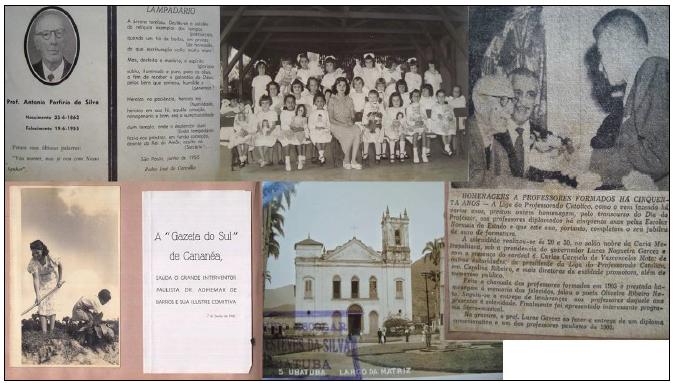

The documentary collection left by Prof. Luiz Damasco Penna regarding his professional trajectory, he distributed part in life. By what we found until the moment, copies of the Office of Education reports and his private library he donated to "Stella Maris" School of Santos. However, Prof. Luiz Alberto Penna, his grandson, is the owner of a very significant collection to the Paulista education historiography: seven albums of images related to the private and professional life of the education commissioner Luiz Damasco Penna. These albums consist of many iconography materials and some textual ones (photos, magazines photocopies, postcards of different sizes and colors, many folders such as ceremony programs and many funeral leaflets), as it is possible to note in picture 3.

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Picture 3 Kinds of photographs found in Prof. Luiz Damasco Penna’ albums

The seven albums have a total of 787 images, most of them, around 72% (566 photos), related to schools and educational activities.8 Some of the photos are from professional photographers, but most of them are from ordinary cameras. The referred albums had their confection ordered, whose support pages are of cardboard and division pages of tissue paper. All them have the same dimension (32 cm x 22.5 cm) and black covers with green spots. Only number 1 has a flat burgundy cover. There is a relative organization in each of them that follows a chronological order. An exception is album 7, where all photos are from the 1910s and 1920s, which should be album 1, giving the impression that they were found and organized later. The images, in their majority, are glued, but some of them are fixed within corners and need restoration.

Table 2 Composition of Luiz Damasco Penna’s photo albums (no. of imagens)

| Album Number | Teaching Activity | Parents and Friends | Total of Images |

|---|---|---|---|

| One | 49 | 51 | 100 |

| Two | 97 | 16 | 113 |

| Three | 47 | 59 | 106 |

| Four | 92 | 4 | 96 |

| Five | 122 | 0 | 122 |

| Six | 101 | 25 | 126 |

| Seven | 58 | 36 + 30 postais9 | 124 |

| Total General | 566 | 191 + 30 | 787 |

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photo albums. Author: Maria Apparecida Franco Pereira.

What had taken Luiz Damasco Penna to collect so many school photos? For sure, the professional activity counts too. It is possible that some of these photos have been produced and assembled by exigency of the Education Department, as in the 1930s and 1940s the general administration of the education area of São Paulo gave special attention to inspectors' and commissioners' annual reports while an instrument to follow the pedagogical renovation based on the principles of the New School implemented in the State. (SOUZA, 2009).

The reports should confirm the physical conditions of schools, instruction efficiency, and all type of problems identified in school establishments. The regional commissioners were instructed, through circular letters, to make detailed and extensive reports about the more diversified aspects of school life of their respective region, presenting statistic data, textual and visual elements such as tables, graphics, drawings, maps and, especially photos, considered as corroborating documents.10 However, it is also possible that the photographic collection gathered by professor Penna arose from his predilection for photography and sharp sense of organization and documentation, identified in the annual reports of the Education Office of Santos that he elaborated during all his professional life, as well demonstrated by Silvio Pascarelli (2002).

Although Penna died in 1985, the activities portrayed in the albums continued until 196011, the year that he retired. They are collective memories from different moments of this life. Almost thirty years of existence dedicated to translating the educational works for the Editora Nacional (where his brother João Batista directed the Library of Education), the superior graduation in Santos (1958-1968), teaching School Administration in the course of Pedagogy of the Faculty of Philosophy, Science and Letters (nowadays named Unisantos) and his activities as a member of entities of class (CPP and ANPAE, of which his was one of the founders in 1966), do not appear much in the photo albums.

In this manner, the photographs related to teaching and inspection activities can be classified in three sections: about his graduation; his career before 1932 while working as a teacher, principal, and district inspector; and as an education commissioner in the North Coast and South Coast (a time abundantly registered in photos, in albums 5 and 6).

It is worth highlighting, here, the composition of album no. 1, once it is varied and different from the others in its organization. This album reveals Penna's start point from his graduation in the Normal School of Praça da República (1912-1916) and ends up in 1936 when he presents photos of people and students of places where he worked before taking position in the Regional Education Office of Santos. Redenção, Óleo, Piratininga, Monte Alto, were some of the areas he worked as a teacher and overall as a principal. This album also presents countless family photos. He regularly added photos of his brother Batista (1909-1990), who became an important personage in the pedagogical works sector, at the Editora Nacional, and from his foster brother, Zenon Cleantes de Moura, a teacher at the Escola Experimental da Praça and, later, the first education commissioner of Santos, in the initial implementation stage of the Office (named in April 21, 1922). In many photos, Maria Henriqueta Silva appears with Penna, a workmate, and active teacher, whom he married later.

In the set of the seven albums, legends, in general, are incomplete: there are photos with no title or date, denoting they are photos from the quotidian12, gathered for the memory of the organizer, but with no enough value as a documental record, which would be probably Professor Penna's desire.

In a general manner, it is possible to say that the seven photograph albums of Luiz Damasco Penna offer many elements for the study of school culture, allowing the assertion of the following aspects:

[1] the regular presence of female teachers while inspectors are in their totality male; so, in administrative-educational positions.

[2] the road is the place where the school becomes more visible (through parades, school facades, scout groups presentations, within others).

[3] the students' extra-class-activities are present in a rather large number, like parades, civic activities, competitions or expositions of handcraft work, garden services.

[4] inspector’s visits in the classroom, working together with the teacher in the class.

[5] means and difficulties of transportations (horse, boats, bogged car)13.

In the direction of Santos Education Office, Penna interacted with school principals, teachers, his inspection auxiliaries, with other education commissioners. So, many pictures of the albums of this educator are from meetings in which it is possible to recognize inspectors of Santos region as Turiano Flávio de Andrade, Primo Ferreira, Suetônio Borges Bittencourt, besides principals as Pedro Crescenti.

Visits and meetings with educational authorities were privileged themes in the photos collected by Damasco Penna (mostly in album no. 4), as seen in picture 4, which shows Fernando de Azevedo at the center on the left, and Dr. Luiz Gonzaga Fleury, Head of the Education Direction Board, who Penna guided, from May 16 to 31, 1936, in the zone of Registro-SP, on the right.

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Picture 4 Meeting with Fernando de Azevedo (1933) and visit of Professor Fleury in Registro (1936).

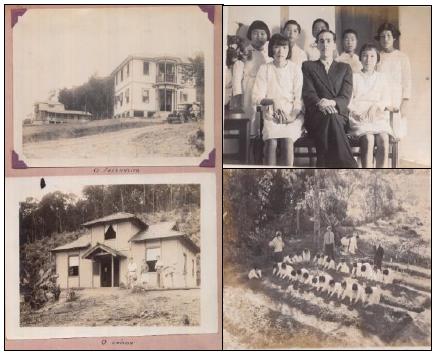

Many images are from school buildings or isolated primary schools. There is no monumentality, neither neglected constructions, in general. There are many postcards14, showing cities or areas around schools. It is interesting the photos of activities in class during the inspector's visit, but most of them are in open spaces, as cameras were not appropriate for indoors at the time. Some photos (of graduations or celebrations) were taken by professional photographers but most are from amateurs. It is also relevant, the presence of the Japanese migration in the zone of Ribeira, privileged in the iconography records of Penna, especially in albums 6 and 7, in which there are many images of Japanese activities in experimental fields, schools, accompanying Japanese and foreign authorities' visits, artistic and school festivities.15 In picture 5, some of these images are presented: a farmhouse (above) and a settler house (below) on the left, students from the Japanese settlement of Registro on the right.

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Picture 5 The residence of Japaneses in the Vale do Ribeira and students of the S.G. of Raposa, Registro, 1938

In this way, we can affirm that, in this rich iconography collection, memory and representation are interwoven in the multiple faces of school inspection and life.

2-Memories and representations of school inspection

The iconography collection delimited to the analysis of this text comprehends 566 photographic images that can be classified as school photos in the terms indicated by Bencostta (2011, p. 400), "those produced in or referent to the school universe”, which mixed with family photos, constitute memories of a trajectory in which the professional activity was inseparable from memorable occasions of family life. If, as Susan Sontag observed, "Through photos, each family constructs a portrait-chronicle of itself" (2005, p. 19), in the photo albums of Luiz Damasco Penna, his performance as a school inspector and commissioner, besides the Santos region school network, are fundamental parts of the visual speech of the family albums that he helped to collect and file. In the sequence of this text, we sought to question these images as memory and representations of education.

Jacques Le Goff (1994) highlighted the revolutionary nature played by photography in the social memory from the moment it appeared in the nineteenth century. As this author observes, the photography produces and democratizes the memory, "gives it precision and truth never before attained in visual memory, and makes it possible to preserve the memory of time and of chronological evolution". (1994. p. 466).

In a work that represents in Brazil a milestone in the reflection about photography as a historical source, Boris Kossoy affirms the importance of taking into account the elements involved in the photography production, i.e., the subject, the photographer and the technology (KOSSOY, 1980, 2001). This author has attracted attention to the multiple faces and realities of photography, pointing out that, besides the visible dimension, the evidence, which is immovable in the document, it encloses other invisible faces, i.e., the life of situations, men and women portrayed. For that, for this author, it is essential that the historian, while using photos as sources, takes into account that they are a representation elaborated from cultural conditions and technical and aesthetic criteria, which involves indispensable methodological concern, once that the index and icon present in the photograph can not be split apart from the construction process of representation.

According to Possamai (2008, p. 254), "As representations of the real, the visual images construct hierarchies, world visions, religious beliefs and utopias and, in this respect, can be constituted of valuable sources to the comprehension of the past". In this same direction, as well as remind us Andrade (1990), photography is a source that demands from the historian a new type of criticism. Paraphrasing Jacques Le Goff, this author proposes considering photography simultaneously as image/document and as image/monument. This double dimension implies taking into account the photography as referent, a mark of past materiality, and as a symbol, "what, in the past, the society established as the only image to perpetuate for the future". (ANDRADE, 1990, p. 23). Besides the work of interpretation, the researcher must establish thematic series for the exam of the iconographic set selected to the study (LEITE, 1993, POSSAMI, 2008).

Concerning the past of education, school photographs constituted a photographic genre diffused in the nineteenth century, as a result of the composition of national systems of education. School classes, graduation portraits, and photos fomented the photograph commerce, making school a relevant object of the photography vision (BENCOSTTA, 2011; LEITE, 2005). In this respect, Abdala (2013) highlights the laudatory and memory appeal of photography of school thematic. According to this author, a school photo “encompasses school buildings, the developed activities, but fundamentally the photos that authenticate a relation of identification between the student, his family and the society, and the school”. (ABDALA, 2013, p. 102).

In the case of Luiz Damasco Penna's albums, the photos related to education allow various rearrangements in thematic subseries such as school facades, students' classes, civic commemorations, scout groups, patriotic parades, rural primary schools, graduation boards, within others. Although, for this text purposes, we regrouped the images in three thematic groups that express the school inspection exercise: a) Traveling to visit schools; b) Monitoring the school network; c) Taking part in ceremonies and special events.

2.1-Traveling to visit schools

Until the 1960s, the visit to schools consisted of one essential activity of the school inspection service in the State of São Paulo. Through the visits, school inspectors and commissioners supervised the work of principals, teachers, and employees of graded primary schools and teachers of isolated primary schools, checking the classes regularity and efficiency, students' and teachers' attendance, programs fulfillment, the teaching school subjects methodology, conditions of the school buildings and didactic materials, final exams application. They oriented principals and teachers about the completion of their duties, held pedagogical meetings, and divulgated desirable practices. As well said by Denise Silva (2004), commissioners and inspectors were seen as representatives of the State, as educational authorities with power and technical competence. Inspectors supervised and were supervised; in the schools, they registered their impressions in the Book of Visit, and for the Education Office, they presented their accounts monthly, besides visit cards and reports.

However, the visit to educational establishments comprehended a constant challenge due to the operational conditions of the school inspection: a restricted number of inspectors to attend a large number of schools in each region, the size of the municipalities, the difficulty in the communication between the localities due to the poor conditions of roads and driving expenses.

In the annual report of 1936 presented by Luiz Damasco Penna to the Education and Instruction Director, he informed that the average of visits of inspectors by class in the region of Santos was 3.3 and by school 4.1. The kilometers crossed by them were 35.852. He still informed about the visits of his own: “I visited 28 rural primary schools, 178 graded primary school classes, 60 private primary schools classes and 24 of other schools classes, in a total of 290 schools unities”. (REPORT OF THE SANTOS EDUCATION OFFICE, 1936). In the report of 1938, Penna mentions with details problems faced by him and school inspectors of Santos office in trips to visit schools of the region:

Well, in 1937, inspectors, including me, were six, traveled 44.455 kilometers, from which 22.485 in railroad and 4.547 by car, as the others State inspectors; but from which 2.583 by horse and 14.840 by fluvial and maritime boats; even by air as I went in a 111km hydroplane trip.

To travel two thousand and five hundred kilometers by horse and around fifteen thousand kilometers by boat, in single words, is one thing; but another thing for who travels them. (REPORT OF THE SANTOS EDUCATION OFFICE, 1938).

Due to the centrality of the trips in the inspection work, professor Penna sought to collect photos that showed transportation means used by him and the other inspectors and hotels where they stayed and rested.

Picture 6 illustrates trips by horse, a transportation means of typical use of inspectors at the coast and interior of the State of São Paulo. Although the gallantry presented in the picture, the description of professor Penna allows apprehending the difficulties of the usage of this transportation means:

There is a long way between a mile journey in a vigorous animal and good road, and the poor and dangerous equitation to which, here, we are submitted to. In ordinary, there are no roads or even paths. There are tracks, many of which in the coastal cliff and enough for the horses. So, for hours and hours, sometimes, frequently under rain common to the coast, of the sunny side of the region, dangerous and brusque storms. Not always the safety of a new kind of a late afternoon dinner (author's emphasis) at six or seven o'clock in the evening, and rest on a sleeping mat. We do not count the risks, common ones, as animal missteps, long walk, climbing as if climbing stairs, sometimes with the help of both feet and hands, wading rivers and bars in the dark and uncertainty of the night. (REPORT OF THE SANTOS EDUCATION OFFICE, 1938).

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Picture 6 Luiz Damasco Penna on a horse to work, c. 1940.

On the coast, another transportation means much employed by inspectors was the boat. Concerning the maritime transport of Santos' region, professor Pena presented detailed considerations in the 1938 report, pointing out the different kinds of boats used by him and inspectors in the inspection trips, and the difficulties of the fluvial and maritime journeys:

From the sea, not a word to say. A section - boats - of the Monthly Summary Bulletin comprehend a retrospective museum of nautical arts, from luxury liners of Blue Star Line that touch São Sebastião, but which boarding is closed for us for the high cost of the ticket, until the more remote dugout canoe left as the last Tupi trace. Within this curve, coastal ships of second, third and tenth order, fluvial ships, steamboats, of the empire time, small sailboats from the south, those that are theme of newspaper chronicle and one day dawn raised, the embroidery unkept, cutters and yachts of thousand species, tiny fishing boats - a fridge ship's hold and a motor on the water and a wood that rests the passenger - an infinity of things of which are made those fifteenth thousand kilometers where many thousand hours of all uncertainty and discomfort is lived. (REPORT OF THE SANTOS EDUCATION OFFICE, 1938, p. 6-7).

The image of picture 7 is elucidative in this respect, presenting the arrival of professor Penna together with other men in one stop of the Paulista coast. The presence of photos of the sailboat Almirante Saldanha and Atlas in Damasco Penna's albums indicates the relevance of these vessels in the inspection service at the coast.

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Picture 7 Boats used by commissioners and inspectors in the school region of Santos

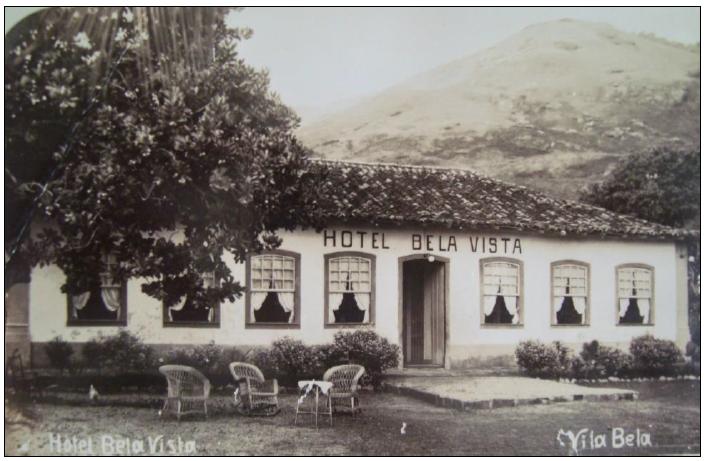

While appreciating Luiz Damasco Penna's photo albums, it called our attention some images of hotel facades on postcards and photos. It was not by accident that professor Penna kept these images, which correspond to significant aspects of the inspection trips. After hours of traveling or a day of school visits in the region, this kind of inn fitted inspectors, commissioners, and even teachers, for resting and sleeping. In picture 8, the details of the Hotel Bela Vista building, a big house of large windows and wood doors, surrounded by trees and hills on the background.

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Picture 8 Bela Vista Hotel, Vila Bela (Postcard)

In the school visit action, inspectors and commissioners acted as "pilgrims" of the educational administration, bringing tension to the multiple senses implied in the control, guidance, and supervision of instruction. The pictures collected by Luiz Damasco Penna put into question the vicissitudes of the work of these professionals of education and invite us to question, from a different perspective, the exercise of these school inspection agents.

2.2- Monitoring the school network

In the school inspection work, inspectors and commissioners should observe the more diversified aspects of the school network: the conditions of the buildings, the materials, the fulfillment of the programs, teaching methods, school bookkeeping, the performance of teachers and students. The numerous school photos collected by Luiz Damasco Penna reveal different representations of this school routine, diverse and multifaceted.

The photos of Luiz Damasco Penna's albums reproduce dominant formats of the school universe diffused in the country until the middle of the twentieth century, as facades of school buildings, portraits of students' classes and teachers' groups, graduation boards, solemnities and events pictures, school practices, among others.

For this study, we selected the more recurrent types of pictures of professor Penna's albums that explicit the dimension of the inspection activity of monitoring school life. We began with the school buildings, which were a permanent concern of school inspectors, and commissioners, who should check, certify and inform the central education authorities, about the conditions of those facilities.

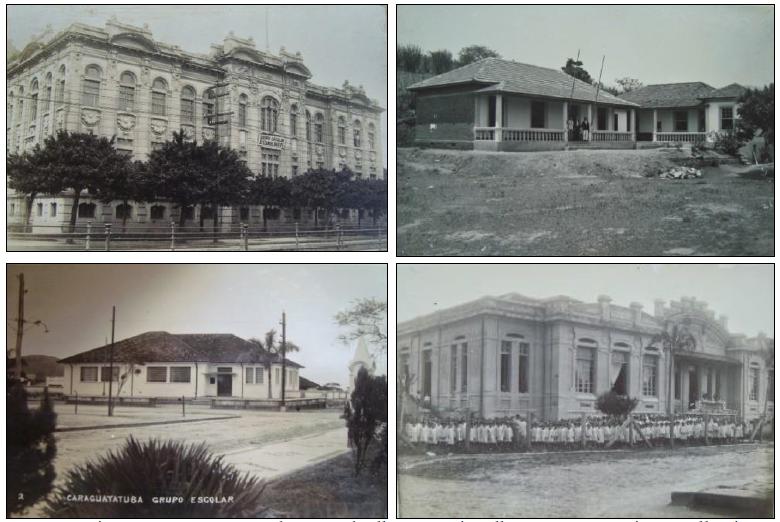

Pictures 9 and 10 are denotative of the variety of the elementary education schools in Santos region. It is worth to mention that the photos of the school buildings were much used at the beginning of the twentieth century in the State of São Paulo in postcard to diffuse the action of the Public Power in the field of education, giving visibility to the architecture, especially of graded primary schools and Normal schools built by the State.

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Figura 9 Facades of graded primary schools building of the school region of Santos.16

Nonetheless, monumental school architecture was limited to some schools and places. As Souza (2009) observed, school construction policy did not follow the fast expansion of the elementary school in the State of São Paulo. Consequently, a good part of school unities operated in modest buildings and rented and adapted residences. The problem was vaster in rural areas where most schools worked in houses borrowed from farmers, in precarious conditions, several wooden houses, shacks, or hovels.17 It is possible to learn by that why school buildings consisted of one of the biggest problems of public education.

On the Santos Education Office report of 1935, the commissioner Luiz Damasco Penna presented a thorough description of the physical conditions of each of the school buildings of the Paulista coast. According to Penna, from 24 graded primary schools existent in Santos region, only 9 (nine) worked in buildings of their own while 12 in private buildings of critical conditions. The situation was even worse at the rural primary schools of the region. Only 40% of the 136 rural primary schools of the region were in good infrastructure conditions while 60% could be classified as under regular or poor conditions. For that, the commissioner reiterated his position:

We have the conviction that as long as we are not taking charge of installing the rural teacher, every attempt in this sense will fail, not only to provide positive guidance to rural education but a proper school activity. It would be priceless to convince the municipal mayors that it would be better to build a big house a year than to appoint as municipal teachers semi-illiterate and amateurs at 100$000 and even at 50$000 per month. (REPORT OF THE SANTOS EDUCATION OFFICE, 1935, p. 12).

Commissioner Penna also affirmed that would send early a photograph album containing all school buildings: "During the current year, we will make an album with a photograph of all school buildings to send to you". (REPORT OF THE SANTOS EDUCATION OFFICE, 1935, p. 13). In this manner, the commissioner intended to answer the Educational Direction wish of knowing, attesting and recording the conditions of the buildings where the State public schools functioned.

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Figure 10 Facades of rural primary schools of the school region of Santos (Rural Primary School of Piratininga, 1930, and Standard Rural Primary Mixed School of Enseada, São Sebastião, 1950).

In Picture 10, it is evident, however, the modernization of school constructions in the countryside, product of the state and federal government policies in the 1940s and 1950s. It is a standard rural primary school. An image that presents a well-built house of comfortable appearance, with part of it destined to the residence of the teacher and other school activities.18

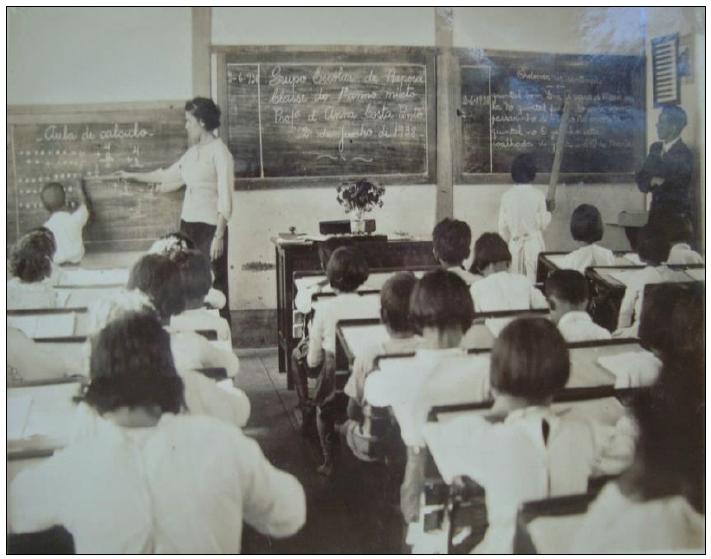

Besides checking the conditions of school buildings and reporting them to the educational authorities, another relevant activity of the inspection service consisted of the coordination of pedagogical meetings and teachers' pedagogical guidance by following classes and giving model class sessions while visiting schools. The classroom, poorly portrayed in school photos, appears in some images of Luiz Damasco Penna's albums, which shows the symbolic representation of this spatial and pedagogical unity that binds identity senses, articulating teachers and students. Picture 11 gives visibility to a typical scene of an inspector's visit to a graded primary school classroom. All students aligned and attentive attended the class. The blackboards are full of math and Portuguese content. On one side, the teacher takes the calculation lesson from a student on the blackboard, while on the opposite side, the inspector observes a student who ordinates sentences.19 In this way, the image reinforces the pedagogical dimension of the inspection exercise, dimension supported in the speeches of the educational authorities, but of difficult execution due to the excess of bureaucratic and administrative attributions of education commissioners and inspectors (LIGEIRO, 2014). In the report of 1943 of Santos' Office, commissioner Luiz Damasco Penna informed that each inspector taught, on average, 470 model class sessions that year, and accompanied, on average, 505 class sessions. (REPORT OF THE SANTOS EDUCATION OFFICE, 1943).

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Picture 11 1st grade mixed, of Graded Primary School of Raposa, 1938.

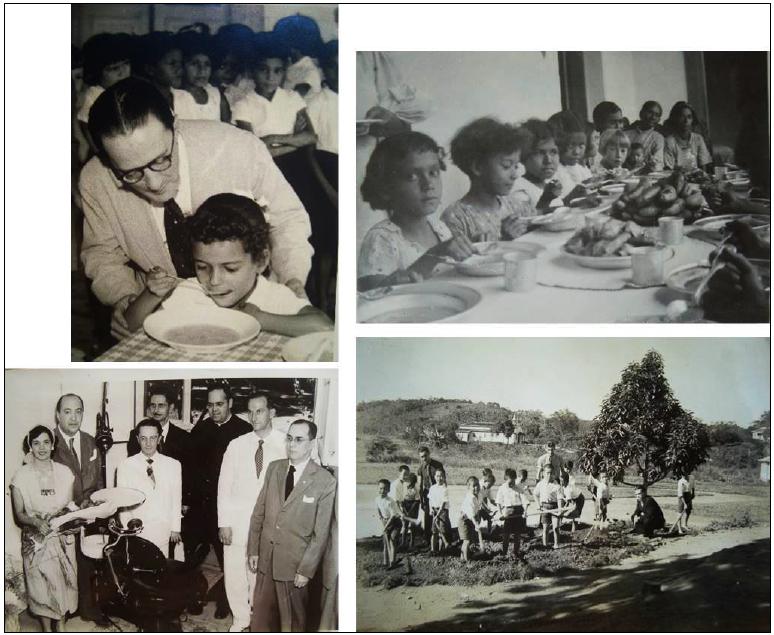

Inspectors and commissioners in their visits to schools, also supervised school practices, especially the functioning of those regarding school auxiliary institutions viewed as significant instruments of didactic renew. In picture 12, the images show some of these institutions like the school soup, the dental cabinet, and agricultural teaching. It was school inspectors’ and commissioners’ responsibility incentivizing teachers and principals of the graded primary schools to implement pedagogical renew practices. Photos of the innovator practices adopted in the schools sought to attest to the advances reached, results, in a certain measure, of the vigilant and diligent action of the inspection service.

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Picture 12 School Auxiliary Service.

Luiz Damasco Penna’s photo albums have many representations of school culture, from school facades to classrooms, from auxiliary services to fragments of pedagogical innovation. These images, probably taken to testify the situation of the elementary education of the Paulista coast, consecrated the memory of the state education. However, as observed by Ciro Flamarion Cardoso and Ana Maria Mauad (1997, p. 405), it is up to the historian to disclose what was not revealed by photographic look, challenge that implies “unraveling an intricate net of significations, which elements - men and signs - interact dialectally in the composition of reality”. In the particular case of this text, it is worth to point out the social and educational place occupied by inspectors and commissioners in the construction of the school culture.

2.3- Taking part in ceremonies and special events

A considerable part of the school commissioner work consisted of participating in festivals, events, and solemnities, representing the Public Power and contributing to the success of the activity. In all these activities, the representation invested in the position of school inspectors and commissioners calls the attention. A polysemous term, and it is worth to retain here the explanation of Roger Chartier (2011) about the old double definition of the term representation, i.e., it “brings to mind and memory absent objects”, as it constitutes the demonstration of a presence. For the analysis of the inspectional activity, it is worth to retain the political and juridical sense of the term explained by the author: “who represents a public office, represents an absent person that should be there”, and “those who are called for a succession being in the place of those who have the right” (CHARTIER, 2011, p. 17) and still, the representation as the exhibition of something, implying authority, dignity and character.

From this perspective, we can interpret the symbolic dimension of the inspectional action as invested in authority and constructed from it. This double dimension is perceptible in the participation of school inspectors and commissioners in the educational events and solemnities. It is worth to highlight, for example, the training practices in elementary teaching service and self-education of the school inspection professionals.

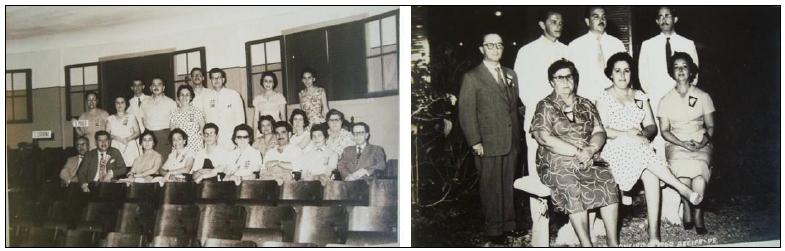

On Luiz Damasco Penna’s photo albums, we found 68 images related to the participation of this educator in various events and solemnities, such as school inaugurations, civic celebrations, authorities’ visits to the schools, graduation and final academic year ceremonies, education congresses.

From 1930, the Paulista state school network intensified the offer of refresh and vacation courses for elementary teachers with different formative finalities.

The presence of a school inspector or commissioner in these activities gave them more legitimacy. Picture 13 shows one of these activities - a course promoted by the sanitary education where prof. Penna was present, and memory perpetuated in the photo.

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Picture 13 Course against malária within the health education program developed on the North Coast with teachers and principals in 1936.

Within the 1930s and 1960s, education guidance and inspection adopted new strategies of normalization and modeling in the educational field, articulating administrative and pedagogical dimensions. Examples of those practices were the isolated primary schools and graded primary school teachers' monthly meetings with masters and inspectors, inspectors' and principals' annual meetings with the local commissioner, and local commissioners' meetings with the State Department of Education authorities. These meetings propitiated the circulation of rules and guidelines, as well as the discussion of educational problems and resolutions in different scopes of action.

In this same direction, the participation of authorities of elementary instruction in educational congresses was promoted by the State Department of Education as a means of cooperation in the school debate and professional improvement. In picture 14, we observe two photos that show the participation of commissioner Penna in events of this nature, a congress held in Porto Alegre in 1958 and the IV National Congress of Elementary Teachers held in Recife, in 1960.

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Picture 14 Congresses and educational events20

Many senses were implied in the activities of representation developed by school inspectors and commissioners. Some of them we can observe in Luiz Damasco Penna own reports: “I had the honor to accompany His Excellency the Federal Interventor in the excursion he realized from Jun 8 to 11 to municipalities of the South Coast, delivering, in name of His Excellency, a prayer, in the solemnity of the foundation stone launching of the S. G. (Graded Primary School) of Registro”. (REPORT OF THE SANTOS EDUCATION OFFICE, 1940, p. 3-4).

Prof. Penna reported the visit of interventor Ademar de Barros to the school region of Santos in Jun 1940. A moment of high solemnity, the visit of the first representative of the political power in the State of São Paulo to the coast involved school inaugurations, parades, and other activities registered in photos as picture 15, where teachers and Cananéia's local authorities accompany the interventor, while students of the graded primary school welcomed the delegation with flags.

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Figura 15 Visit of the interventor Adhemar de Barros to the SG of Cananéia, in Jun, 1940.

In the 1940 report of Santos Office, commissioner Penna still informs about activities of representation developed by him and their private and professional meaning:

I deserved, still, the distinction of representing Prof. Dario de Moura, and, later, you, in different solemnities held in this city, which I attended personally, or designated someone to represent me, either in parties or ceremonies to which this office was invited. I was the patron of a graduates' class from the Institute D. Escolática Rosa, which I am reporting since the distinction was undoubtedly delivered to the professorship I am addressing to, of the Department I have the honor to serve as commissioner. (RELATÓRIO DA DELEGACIA DE SANTOS, 1940, p. 4).

It is possible to affirm, consequently, that it was in the education authority condition where the presence of the local commissioner revealed its entire symbolic dimension as the expression of administrative power. Especially in civic commemorations and parties realized at schools, this participation brightened the solemnity as well as reaffirmed the pedagogical and socio-cultural relevance of the celebration. As Souza (1998) stated, in the transition of the nineteenth to the twentieth century, the Paulista republicans instituted multiple expression symbolic practices of the Republic sociopolitical imaginary in the public instruction system. "Festivals, school exhibitions, children's parades, exams, and civic commemorations constituted especial moments of school life, which gained more visibility and reinforced shared cultural senses". (SOUZA, 1998, P. 241)

As a political, social, and cultural phenomenon, a celebration promotes sociability bonds, also constituting as a stage of social conflicts and tension. As many authors have pointed (OZOUF, 1988, and LEONEL, 2009), a celebration breaks the routine and configures a consecrate time. Public ceremonies, in turn, have the purpose of perpetuating the National memory. At school, festivals and civil commemorations have an unequivocal pedagogical finality. They reaffirm sociability bonds at the same time that they reaffirm cultural practices. Besides, they strengthen civic-patriotic values contributing to reinforcing the historical memory through the celebration of the national calendar.

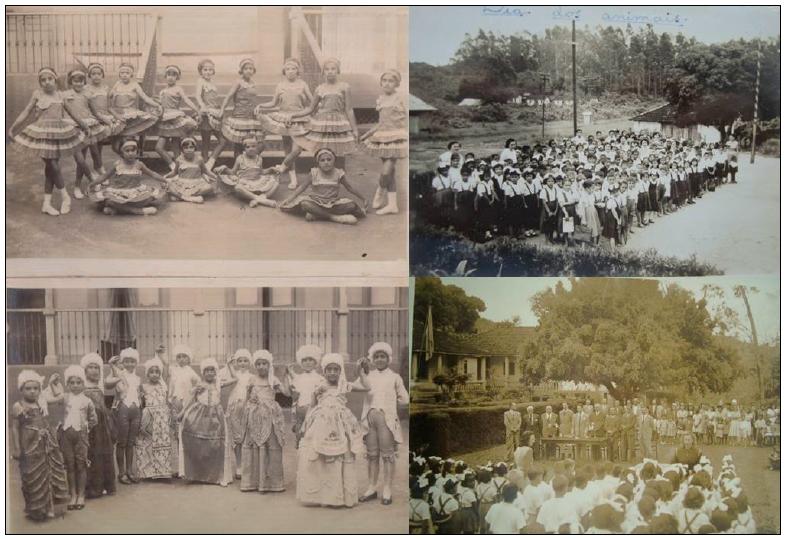

In Luiz Damasco Penna's albums, many photos are showing these ritual moments of the school calendar: independence day, parades in commemoration of school and city anniversary, animals' and trees' day, school final year party.

In all special celebrations, inspectors and commissioners were asked to participate, reinforcing their legitimate authority conferred with the endorsement of the State and the social and educative relevance of ceremony and school.

In pictures 16 and 17, the images present the diversity of school celebrations realized in the region of Santos. In picture 16, two photos on the left show a theater presentation of a group of students in 1952 and two on the right, students' participation in solemnities, in uniform and line, as actors and observers.

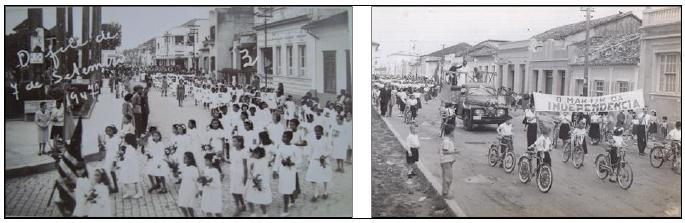

Picture 17 gives visibility to civic parades, a widespread educative practice in the Brazilian and Paulista elementary public schools of the twentieth century.

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Figura 16 School celebrations in the school region of Santos21

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Figura 17 Civic Parades - September 7

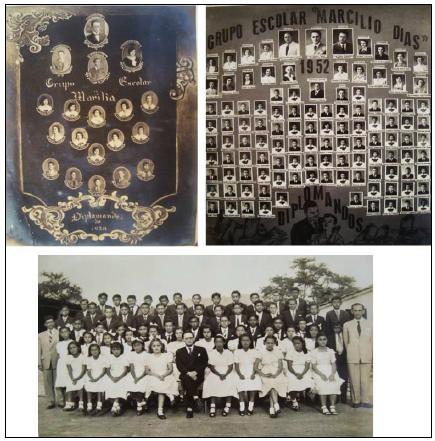

Finally, it is worth highlighting a relevant dimension contained in the representations of the school inspection: the presence of school inspectors and commissioners in the photos of the 4th grade (with the graduates of the elementary course) and the graduation boards.

Figure 19 presents a type of photo that was popular and marketable by the middle of the twentieth century. By the way, as Souza highlighted (2009, p. 322) about this type of photograph: "Taken usually at the end of the school year, they coincide with graduation ceremonies, a certification of the merit reached by so few students". Discipline, attendance, and performance supervision of students comprehended a relevant part of the work realized by the school inspection agents. At the Paulista elementary public schools, final exams were elaborated by the education office and consisted of rituals of public consecration as they validated the performance and conduct of students and teachers, playing a crucial role in a highly selective educational system. In this manner, the school year closing party with the diploma award of students that completed the elementary 4th grade was a solemnity of high prestige and symbolic value to the school community and local society.

Source: Luiz Damasco Penna’s photograph albums. Luiz Alberto Penna’s private collection.

Figura 18 Graduation Boards

The representation of this school merit celebration, registered in photographs, interlaced students, teachers, and education authorities, raising multiple sociocultural senses as honor, distinction, success, and commitment, among others.

The Werle’s analysis (2005) on the relation between the graduation boards and the institutional memory deserves to be remembered as it highlights a dimension of this practice, the one of school cultural representation. As the author affirms: "Graduation is an essential moment in the functioning of school institutions, a significant reference as it confirms the pedagogical acts of success processed in their interior". (WERLE, 2005, p. 3).

Therefore, it is a dual representation: the graduation board as a support material to be affixed in a local of relevance of the school and as a photograph of school souvenir. Also, according to Werle (2005), the graduation boards hierarchize, i.e., they homogenize the students in cloths and poses, at the same time that they highlight graduates and illustrious figures. In picture 18, this hierarchized distribution of the institutional dimension of success can be noted. In the photograph of the graduation board of the Graded Primary School of Marília, 1930, Luiz Damasco Penna is evident in the first place, as the patron. The same occurs in the graduation board of the Graded Primary School Marcílio Dia, of Guarujá, 1952, where prof. Penna appears in the first plan as school commissioner followed to the left by the municipal mayor, João Torres Leite Soares, and to the right by José Paulo Guimarães, the school inspector.

Still concerning picture 18, in the photo of the class, it is possible to note the centrality of the figure of the school commissioner, whose authority represents the figurative sense of the State and educational administration power. In synthesis, one can say that in different actions of representing, the agents of school inspection contributed to the construction of a memory of the Paulista public education.

Final considerations

As affirmed initially, the photograph albums of Luiz Damasco Penna comprehend an iconography inventory of the elementary school culture and overall from the Paulista coast. Such collection allows multiple serial cuts and diverse readings, however, in this text the option was for problematizing the three more usual dimensions of the inspection service in the photographs collected by Luiz Damasco Penna: trips to visit schools, supervision of the school network and participation of inspection agents in events and solemnities of the State of São Paulo.

Representation and memory are constituent dimensions of photography. In Luiz Damasco Penna's albums, representations of school inspection and elementary school remain interlaced. In the professional exercise, school inspectors and commissioners supervised many activities, practices, situations, and events of school life. Photographs are personal memories but also collective memories of the school community: the school, the building facade, the classroom, the class of students, the group of teachers, the graduation board, the civic parades, the solemnities...

As Felizardo and Samain (2007) advert, photography carries the magic of eternizing the moment, evoking memories and feelings. Certainly, for Luiz Damasco Penna, these countless school photos he collected and organized consisted of fragments of his life history, memories of his professional trajectory. However, in the view of the historian of education, they acquire new senses and are converted into documents, representations of the school life, impressive and revealing traces of the school culture. Concerning the school inspection, these photographs instigate a reading against-for-type, i.e., induce to questioning the instituted representations about the inspection service associated to control and exercise of power. What is the meaning of inspection for school inspectors and commissioners? Which is the professional experience of these educational subjects? Which was the contribution of these educators to public instruction?

In a particular manner, this text sought to problematize some of these questions. Luiz Damasco Penna's photograph albums, at the same time they ratify ordinary representations of school, they put into discussion the multiple faces and memories of the performance of school inspectors and commissioners. In this reflection, the photography, also as document and shrine, invites us to see and think differently; for sure, an unforgettable adventure.

texto em

texto em