Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Acta Scientiarum. Education

versão impressa ISSN 2178-5198versão On-line ISSN 2178-5201

Acta Educ. vol.41 Maringá jan. 2019 Epub 01-Out-2019

https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v41i1.47777

HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF EDUCATION

History and philosophy of education in the middle ages: a consideration on the concept of prudence according to Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica

1Departamento de Ciências Sociais e Filosofia, Programa de Pós- Graduação em Educação, Universidade Regional de Blumenau. R. Antônio da Veiga, 140, 89030-903, Blumenau, Santa Catarina, Brasil.

2Laboratório Blumenauense de Estudos Antigos e Medievais, Departamento de História e Geografia, Universidade Regional de Blumenau, Blumenau, Santa Catarina, Brasil.

ABSTRACT. Thomas Aquinas was one among the scholars who contributed to the debate of the most important questions present in the intellectual environments of the thirteenth century. In this article, we analyze one of his main works, the Summa Theologica, especially question 47 of the part that became known as Secunda Secundae, or simply IIª IIªae, i.e. Second part of the Second Part. Take this section into account, we present a short consideration on the concept of ‘Prudence’, understood as the theory or logic of human action, in the sense of a decision-making process. It is argued that Aquinas concept of ‘Prudence’ can help us not only to improve our comprehension of the History and Philosophy of Education in the Middle Ages, but also our own present-day educational practices.

Keywords: education; medieval; Thomas Aquinas; Summa theologica; prudence

Tomás de Aquino foi um dos pensadores que contribuiu para o debate das questões mais importantes presentes nos ambientes intelectuais do século XIII. Neste artigo, analisamos uma de suas principais obras, a Suma Teológica, sobretudo a questão 47 da parte que ficou conhecida como Secunda Secundae, ou simplesmente IIª IIae, ou seja, Segunda da Segunda, a partir da qual apresentamos uma reflexão sobre o conceito de ‘prudência’, que, compreendido como teoria ou lógica da ação humana, no sentido da tomada de decisão, pode nos auxiliar não só a problematizar a História e a Filosofia da Educação na Idade Média, mas também nossas próprias práticas educacionais no tempo presente.

Palavras-chave: educação; medieval; Tomás de Aquino; Suma Teológica; prudência

Tomás de Aquino fue uno de los pensadores que contribuyó al debate sobre los temas más importantes en los entornos intelectuales del siglo XIII. En este artículo, analizamos una de sus principales obras, Suma Teológica, especialmente la pregunta 47 de la parte que se conoció como Secunda Secundae, o simplemente IIª IIae, la segunda parte de la segunda parte. Presentamos una reflexión sobre el concepto de "Prudencia", que, entendida como la teoría o lógica de la acción humana, en el sentido de la toma de decisiones, puede ayudarnos no solo a problematizar la Historia y la Filosofía de la Educación en la Edad Media, sino también nuestras propias prácticas educativas en la actualidad.

Palabras-clave: educación; medieval; Tomás de Aquino; Summa teológica; prudencia

Introduction

Teaching in medieval universities had two main forms: “[...] the ‘lesson’, or commented reading of a sacred or doctrinal text; the ‘dispute’, either prepared (disputed questions) or improvised (quodlibetal questions)” (Pépin apud Châtelet, 1974, p. 152, emphasis in the original). Disputes, originating in the twelfth century, took the form of an intellectual dispute. “In the face of citations by authors (who were called ‘authority’) that differed or even contradicted, there was a need to harmonize or choose between them. It is what gave rise to the quaestio” (Nascimento, 2003, p. 27, emphasis in the original). This intellectual tournament was not something spontaneous but it was part of the task of the master, who posed the question, collected the objections to a previously formulated thesis, answered the objections and determined the sentence: “It began by giving a certain order to the objections formulated randomly in previous debate. It made some counterarguments to these objections. Then came the determination itself, that is, the solution the master proposed for the issue at hand” (Nascimento, 2003, p. 28). Much of the textual and intellectual productions of the Middle Ages was conceived from such techniques, whether drawn from the minutes of disputes, from the notes of students or copyists, or from material prepared by the master for his lessons or disputes (Nunes, 1979; Verger, 1990; Le Goff, 1993).

One of the authors who contributed greatly to the understanding of the main themes debated in the thirteenth century was Thomas Aquinas. Taking this into consideration, from the analysis of a small part of his Summa Theologica (Thomas Aquinas, 1934), the Question 47, known as Secunda Secundae, or simply IIª IIae, Second of the Second, we present some considerations about his concept of Prudence, which will contribute to broaden our understanding about the important theme of the History and Philosophy of Education in the Middle Ages. According to TerezinhaOliveira (2008, p. 208), “[...] to study the History and Philosophy of Education in a given historical epoch implies analyzing the social, political and cultural reality that produced a given educational model”. Considering this, we believe that the analysis of the proposed theme will also provide subsidies for thinking about our own educational practices, observing changes and permanences, focusing not only on similarities, but also on differences because from alterity and diversity we can reevaluate our conceptions and positionings.

Saint Thomas Aquinas and his Summa Theologica

Thomas Aquinas’ life was not very long, he lived only 49 years, from 1225 to 1274, and spent much of his time “[...] within the tranquil frames of a life of a preacher and university professor [...]” (Lima Vaz, 1986, p. 29). At the age of five he becomes oblate5 in Monte Cassino Monastery. In 1239 he returns to his family and joins the newly formed University of Naples. Still in Naples, even against the wishes of the family, he becomes Dominican at the age of 20 (in 1244). With the master general of the order, he sets out for Paris but his brothers kidnap him for disagreeing with his entry into the order.

In 1245 Thomas Aquinas goes to Paris, where he studies at the Faculty of Theology under the direction of Albertus Magnus. In 1248 he accompanied Albertus Magnus to Cologne, staying there until 1252, when he returned to Paris to pursue his studies, obtaining a license in Theology in 1256. He began teaching and earned the title of Master of Theology in 1259. He then returns to Italy where he remains until 1268, teaching in Anagni, Orvieto, Rome, and Viterbo. He teaches again in Paris from 1269 to 1272. In 1273 he teaches in Naples and “[...] departs in January 1274, personally summoned by Pope Gregory X for the second General Council of Lyon. Falling ill on the way, he stops in Fossanova, where he dies on March 7, 1274” (Gilson, 1995, p. 654). Although the term did not originate in the thirteenth century, it is possible to claim that Aquinas was an ‘intellectual’ of his time, in the sense that Jacques Le Goff uses it, to identify masters and teachers whose task was to teach the thought systems developed by them (Le Goff, 1993). We could also refer to Aquinas as a ‘man of knowledge’ (Verger, 1999). Both are anachronisms but which, used with caution, can help us categorize certain specific medieval situations while allowing new ways of reading the past and also facilitating their comprehension for the contemporary audience (Loraux, 1998). Thus, as long as the limits of this historical form are understood and respected, that is, its similarities and differences with our modern uses of the term 'intellectual', its use would no longer be a problem (Teixeira, 2014).

Having lived in the thirteenth century, Thomas Aquinas was the protagonist of the ongoing changes in the period. His ideas sometimes even generated conflicts between him and authorities of the period. Some of his theses, for example, were condemned by Stephen Tempier, bishop of Paris, in 1277, two years after his death. The convictions were only revoked two years after his canonization in 1325 (Nascimento, 2003). Three questions, in very general terms, can be pointed out in Thomas Aquinas that put him at crucial points in the controversy. These points may seem unimportant today, all the more so because we are so used to seeing the figure of Thomas Aquinas so closely linked to Christianity. But, on the other hand, they are fundamental in marking the new directions that, especially philosophy, were taken from then on.

The first question is related to the importance of Aristotle in the works of Thomas Aquinas. This places him in a different perspective from the Augustinian and Platonic tradition that served as the basis for guiding the theological-philosophical thinking of the time and opens up new possibilities of work to answer the questions under discussion. The other two questions are related to this ‘conversion’ of Aristotle to Christianity. The second question is Thomas Aquinas’ distinction between faith and reason, establishing specific competencies for each: reason is concerned with human issues; faith is concerned with divine matters which are accessible by revelation, although reason is also put to work to better understand and commit oneself to the faith. With this distinction, reason (and philosophy) acquires its own status in the conduct of man’s existential questions, both theoretically and practically. The third of these questions is what might be called the internalization of reason or intellect. The dominant thought at the time, under the influence of St. Augustine and Avicenna, kept the agent intellect separate from the individual, a principle general, unique and equal to all in which

[...] the soul and body prepare only to receive that which only he gives; our activity, as well as the activity of things, comes from an outer principle. St. Thomas, on the contrary, thinks of an inner principle, a ‘nature’ that performs its own work [...] becomes a ‘part’ of the soul, multiplies with individual souls [...]. St. Thomas derives from Plato all the thinkers who rob the natural beings of their own actions [...]. The man for St. Thomas is a ‘natural being’ who, even in knowledge, maintains his ‘own action’ (Vignaux, 1994, p. 125-127, emphasis in the original).

This ‘naturalism’ of Thomas Aquinas, which he sought in Aristotle, points to a humanism,

[...] since man is ‘nature in nature’ [...]. The being who knows is not a mere subject opposed to the world, a human compound in which the soul defines itself as the form of the body. ‘It is not the sense or intellect that know, but man through them’ (Vignaux, 1994, p. 128, emphasis in the original).

This conception of the human being exposes intriguing perspectives to think about the theme of freedom and autonomy which we will see later.

In this sense, Foucault (2004) says that it is not in Descartes that the beginning of the foundation of the subject of knowledge is. In an earlier moment there is a break with the theory of divine illumination and the agent intellect, internalizing it in the singular man himself. Thomas makes access to the truth an autonomous process of the human being in knowledge, no longer remaining the demand for a transformation (conversion) of the subject based on spiritual practices, enabling him to be enlightened. According to Foucault, such an event must be sought in a historical moment prior to Descartes, “[...] on the side of theology, which could be founded on Aristotle and that, with St. Thomas, and scholasticism [...] founded the principle of a knowing subject in general” (Foucault, 2004, p. 36).

Unlike Foucault, who points to a rupture, from the conditions of spirituality for access to truth (asceticism) to an autonomous rational subject, we think that Aquinas was able to reconcile the practices of spirituality from the Platonic-Augustinian tradition with Aristotelian thought, founding a rational knowing subject in which reason is a component of the nature of the human being. This harmonization between the two sides leads the crisis of his time to a solution. Based at the same time on Aristotle, especially on his moral and political works, and on the tradition that cultivates the conversion of the subject (not in the religious but gnoseological sense), in which the person deals with himself, what Foucault (2004) calls ‘self-care’, Thomas Aquinas achieves four striking things: a) to preserve tradition (transmission) as a culture of the subject’s spirituality, caring, or occupation; b) introduces and resignifies Aristotle’s work in theological thought, for it was already affecting Christian thought even before Thomas; c) faces and forwards solutions to the crisis that Christian thought was going through, presenting other interpretations for the important theological issues of the period; d) open concrete possibilities for existential questions, such as organization and policy of the government, freedom, personal conduct in the face of singular situations to which the traditional model, perhaps already worn out or impoverished by pure repetition, was no longer responding to satisfactorily. “The formidable success of Thomism is precisely because it has been able to extract from the chaos of new ideas the specific remedy to the dangers they present” (Gilson, 1995, p. 481).

The work of Thomas Aquinas “[...] of vast extension comprises models of all genres of philosophical works then known. If we stick to the content of his works [...] we will distinguish, ‘roughly speaking’, the Comments on Aristotle, the Summas, and the ‘Disputed Questions’” (Gilson, 1995, p. 654, emphasis in the original). But, as Foucault (2004) says, speaking about the author and the work:

[...] is everything he wrote or said, everything he left behind him part of his work? [...] Among the millions of traces left by someone after his death, how can his work be defined? The theory of the work does not exist (Foucault, 2004, p. 267-270).

In the case of Thomas Aquinas, this problem may be even greater: a) due to the characteristics of the time, a time when everything is handwritten by the author, by copyists, by students; b) due to his style, his work as a thinker, researcher, writer is largely a function of teaching and so much of his production was not systematically written as text.

Among all these works of Thomas Aquinas, we will present a short outline of Summa Theologica, because it deals with the concept of Prudence, developed from question 47 on the part of Summa that became known, especially in the area of Medieval Philosophy, as Second of the Second, in Latin: Secunda Secundae, or simply IIª IIae. We hope, from the considerations about this specific source, to contribute to broaden our understanding of the important theme of philosophy and history of education in the Middle Ages.

The term summa comes from Latin, summa, and is related to both sum and summary, the essence of something. In this sense, it reveals an intellectual procedure that, based on the syllogistic style, performs calculated confrontations of propositions (arguments), making the author's thinking appear in a rigorously logical way. In the Middle Ages, the term designates a literary style, a way of organizing, systematizing and exposing textual production. Thomas Aquinas is not the only one to write summas, on the contrary, he learns the style of his time.

The style of the summa is directly linked to the style of the disputed questions. Initially there is a general theme. This theme is divided into questions, which are sub-themes of the general theme. They are called quaestio/quaestionis, that is, question/questions because they present themselves in the form of a problem, a concept, an attribute, to be faced theoretically. To do so, it must be defined, delimited, distributed in its details and resolved. Therefore, each of the questions is subdivided into smaller topics called articles. The article opens usually in the form of a question (eg, “whether prudence knows the particular.” IIª IIae, q. 47, a. 3).

An excellent, synthetic and precise exposition of the structure of an article in Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica is presented to us by Prof. Carlos Arthur R. do Nascimento:

Each of the Summa’s articles has the structure of a disputed question article [...]. There is always an initial question, which gives rise to two opposite answers. Here are some arguments (three or four in general) which are contrary to the thesis that Thomas wants to support. Following these arguments comes a ‘backward’ argument, which most often consists of quoting an ‘authority’ and which in most cases represents the opinion of Thomas Aquinas. This [St. Thomas's opinion] is presented, quite accurately, in the ‘body of the article’, that is, in a short explanation that follows the argument, in the opposite direction, and contains the thesis supported by Thomas Aquinas and its justification. Having done this, Thomas responds to the initial arguments (Nascimento, 2003, p. 69, emphasis in the original).

Most of the time, in this response to the arguments, the author makes it clear that the disagreement between the argument initially posed and the position of the author is rather a matter of point of view, of interpretation (the way the argument was being understood) and he ‘works’ the argument giving it a ‘more precise’ meaning so that it fits in with the author’s thinking (‘the authorities have a wax nose’). The Summa was a kind of encyclopedic practice. It tried to gather knowledge on a particular theme from this system of debates in the elaboration of these quaestionis (Teixeira, 2015).

The Summa Theologica6 is the work in which Thomas Aquinas worked the longest, which began in 1266 in Rome, extends during “[...] his second stay in Paris and even his residence in Naples at the end of his life, remaining unfinished” (Nascimento, 2003, p. 43). In it, Thomas worked for eight years. It is a “[...] masterpiece of methodical progression and thoroughly prepared by numerous preliminary works” (Châtelet, 1974, p. 157), in which he proposes to “briefly and clearly expose that which refers to the sacred doctrine” (Nascimento, 2003, p. 44).

In the general structure of the Summa, the first part deals with questions concerning God, his being, his essence, his operation, and the origin of creatures from him. The second part, written at the moment Thomas reaches his intellectual maturity, “[...] is the longest, and certainly the best structured, of the three that compose it” (Nascimento, 2003, p. 51), deals with the human being, “[...] not as soon as he is ready from the hand of God, but insofar as he is also able to make himself and make his world, to choose what he wants to be. This is every personal and collective human adventure” (Nascimento, 2003, p.75). This part deals more directly with ethics, has a direct influence of the Aristotle's ethics, especially the Nicomachean Ethics (without neglecting every Christian tradition that came from the Patristics). Thomas Aquinas makes a study of human actions, the proper actions of man. From the concepts of virtue (good habits) and vices (bad habits), he presents a general and specific study of man, his being, his action and his end, and exposes how and how much the specific action of a human being is directed by the end of man in general, that is, each action is related to its own particular end and at the same time to the end of man in general. In a way, the work of Thomas Aquinas is organized in the “[...] instrument of the dialectic, characterized by its two complementary and inverse movements: one proceeds from the supreme unity to the multiplicity of genres, species and individuals; on the other, it returns from multiplicity to unity” (Châtelet, 1974, p. 100-101).

The third part of the Summa, more strictly theological and Christian, deals with Jesus Christ as savior and redeemer, his sacraments and human salvation: “In the third part we are faced with pure divine gratuity. We are facing the concrete history of God's gifts, that is, the divine freedom and the contingency of history” (Nascimento, 2003, p. 87). This reminds us that while there is a strongly philosophical work, in some parts more and others less, Thomas Aquinas’ general enterprise in writing the Summa Theologica was to write a work of theology for he was a theologian.

Prudence in Thomas Aquinas

We could call phronesis or prudence a ‘decision-making theory’ (Nascimento, 1993). In this sense, it relates to every aspect and every moment of human life. This condition of man of being unfinished, open, makes him a free being, in the process of constituting himself, compels him, uninterruptedly, to make decisions. Not wanting to decide is in itself a decision. Freedom as a principle that forces us to decide is an idea present in Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, as in many others, both inside and outside philosophy. The important thing is not to lose sight of the scope of the decision question. We will return to this in the next item.

As seen above, the medieval environment was strongly impacted by the insertion of Aristotle's thought, markedly from his ethics, which cannot be disconnected from his cosmology, anthropology, metaphysics etc.: “Medieval ethics can be divided into two very different phases: before and after the diffusion in the schools of the Latin West of Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics” (Lima Vaz, 2002, p. 199). Nor is it for the least: in a world of patristic, Augustinian tradition, whose main endeavor is the accommodation of the human being to a divine project of the world, in which not even the intellect is in man, but outside him, in a transcendent, supernatural plane, it is inserted a theoretical-philosophical framework that gives man a reason capable of knowing by itself and capable (more than capable, conditioned - it is its condition) of making its own decisions about all human things. It is admirable that this fact did not produce major ruptures. On the contrary, several writers of the time managed to reconcile these two strands, resizing that experience of Christianity. Among these is Thomas Aquinas who lived the experience of this meeting of the two theoretical aspects. According to Lima Vaz, one can point out two phases in the ethics of Thomas Aquinas,

[...] due to the theoretical instrumental used, knowing that it was only in the last years of his life that Thomas Aquinas had the opportunity to use the Nicomachean Ethics in depth in the construction and exposition of his moral doctrine in the second part of the Summa (Lima Vaz, 2002, p. 213).

Only in 1247/48 Robert Grosseteste made a full translation of the Nicomachean Ethics. To this Albertus Magnus made a full commentary to which Thomas Aquinas, who followed the courses of Albertus Magnus, also had access. Even with the strong presence of the Nicomachean Ethics, there is no disruption in Thomas Aquinas’ thinking; on the contrary, it develops, progresses, in a harmonious line. And his challenge is not small: “[...] to reconcile the ‘historical’ order, or order of saving events, of ‘grace’ with the ‘static’ order, or order of hierarchical perfections, of ‘nature’” (Lima Vaz, 2002, p. 217, emphasis in the original).

Specifically on the question of prudence, Aquinas first studies it “[...] in his commentary on Book III of the Sentences (1254-1255). He will study it again in the second part of the Summa Theologica (1268-1272), contemporary to his Commentary on the Nicomachean Ethics” (Nascimento, 1993, p. 367). Even knowing that already in the Iª IIª Thomas Aquinas elaborates important elements, both in the terminology and in the conceptions of a theory of human action, for our approach to prudence in Thomas Aquinas, in this article, we will limit ourselves to Questions 47-567 of the IIª IIae because it makes up a possible unity, ranging from the concept of prudence to its mode of operation, from the mode of acquisition by the human being, to its implications and applications in everyday life..

Some preliminary questions may be raised before we specifically enter the Aquinas approach to prudence.

The first question is a recommendation, not to lose sight of the Summa own style, which is not a linear description but is in the form of a disputed question..

The second question concerns how to use the authorities, in the form of arguments, for or against the question raised by the Article, to corroborate the author's thesis or even to answer the arguments. This requires caution in always seeking Thomas Aquinas’ perspective, seeking to understand what the fundamental thesis he is defending and the specific way in which he uses the argument of authority to achieve his goal. Thus, we reduce the risk of ‘anti-tomistic’ interpretations of his writings8.

The third relates to the term means: Thomas never uses the term means to designate the means employed to reach an end. For this he uses “[...] that which is in view of the end” (IIª IIae, 47, a. 6), de his quae sunt ad finem in Latin; de ce qui est pour la fin, in french. In the Portuguese version, the translator employs the term means: ‘means conducive to the end’ but it is a problem in our language, where the term means refers interchangeably to both meanings. This may lead to misunderstanding what was originally said by Thomas. When he uses the term ‘medium’ it is to designate the equilibrium point between extremes, the 'middle ground' between opposing terms, the intermediate way.

The fourth question concerns the general framework of virtues in which Thomas Aquinas is situated. Keeping this picture in mind is fundamental to following the line of reasoning, steps, and assumptions of Thomas Aquinas’ thinking. In this framework, he broadly follows Aristotle but gives him a more precise and detailed organization. In the framework of human reason, the being and the way of acting of each party, the specific attributes that compete with reason, the example is also Aristotle in general, although it introduces the concept of synderesis in practical reason.

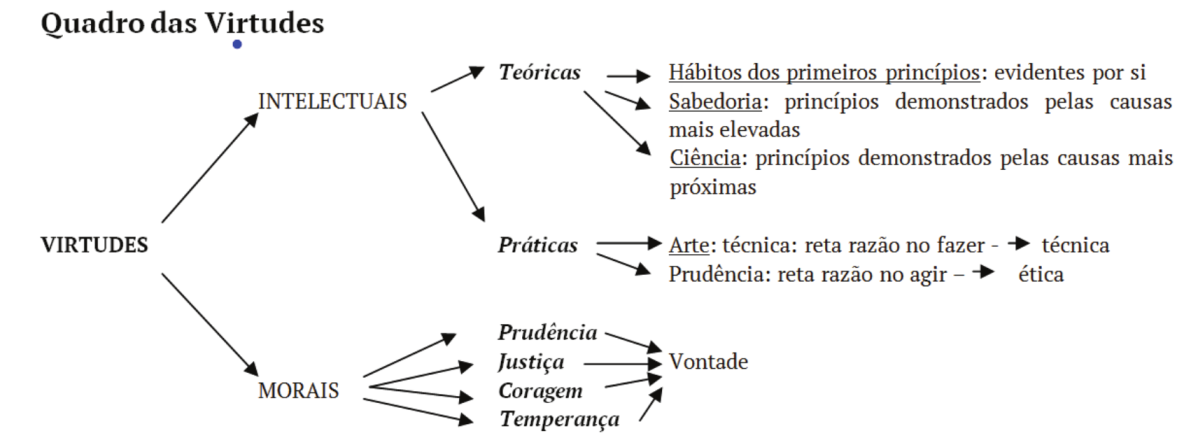

The scheme of reason is evidenced in the intellectual virtues. Reason is subdivided, according to its object, into theoretical reason and practical reason. Theoretical reason is concerned with universal and necessary things, which are not the object of deliberation. The universal and necessary things are distributed in three different ways: a) the first principles, self-evident, which cannot be demonstrated and which are grasped by the intellect; b) propositions that are not self-evident and which need to be demonstrated, discursively, from the highest causes and are the object of wisdom (theoretical or philosophical); c) propositions not self-evident and that need to be demonstrated discursively, from the nearest causes and are the object of science. In the scheme, the intellect, as intellect, apprehends and, as reason, reasons to demonstrate metaphysical (wisdom/philosophical) and physical (scientifical) causes. Let us remember that the terms science and philosophy are not clearly separated for Thomas Aquinas and are often used as synonyms. Practical reason has as its object multiple, variable things that can be deliberate. It is distributed in two different ways: a) art, which deals with making, techniques and the creation of artifacts in human activity; b) prudence, which is concerned with acting, with the ethical part of human action. In the table of virtues, represented in Figure 1, we systematize the set of such attributes.

The moral or cardinal virtues do not belong to intellect or reason, for it is not for them to reason, but to choose, which is an act of will, of desire. Prudence is the exception for it appears in moral as well as intellectual virtues. Thomas Aquinas is already dedicated to demonstrating this question in the first article of question 47 (IIª IIae, q. 47, a. 1) by saying that prudence has its proper seat in reason, since it is up to it to deliberate, search, research, compare , judge and order based on what was deliberated and judged. But it is also a love, not essentially but causally, for it moves reason to understanding and it also implies choice and action, which are acts of will and, as such, fit into moral virtues. But it is noteworthy: essentially it is an intellectual virtue, only causally a moral one.

In the second article (IIª IIae, q. 47, a.2) Thomas Aquinas demonstrates that prudence cannot belong to theoretical reason, for although it is also a form of wisdom, theoretical wisdom is concerned with absolutely high things, which are not the object of deliberation, for truth does not depend upon deliberation. Prudence is concerned with human things. Quoting Aristotle, he says that prudence is the right reason applied to what we must do in view of some end and is not determined by itself, depending on deliberation, judgment and command to choose from. Therefore, it is practical knowledge not, however, theoretical.

In the third article (IIª IIae, q. 47, a. 3) Thomas shows that prudence must not only consider rationally but also apply itself to work, the end of practical reason. Since acts are always related to the singular, the prudent must necessarily know the universal principles of reason and the singular ones, which are the object of action. In responding to the second argument (IIª IIae, q. 47, a. 2 ad. 2m) Thomas Aquinas takes up the theme of experience, which was also fundamental to Aristotle. Thomas says that since the singulars are infinite in the sense that they are many (the infinity of the singulars), reason cannot grasp them all, which makes our provisions (deliberations, judgments, commands) uncertain. However, from experience, the infinity of singulars is reduced to a finite number of cases whose knowledge is sufficient for human prudence. In replying to the third argument (IIª IIae, q. 47, a. 2 ad. 3m) he quotes Aristotle again, saying that prudence, perfected by memory and experience, becomes apt to judge promptly the particular cases that present themselves.

In the fourth article (IIª IIae, q. 47, a. 4), Thomas demonstrates that to prudence belongs the application of right reason to works, which is not possible without the rectitude of appetite. Habits concerning the righteousness of appetite are virtues more essentially because they have as their object good not only materially but also formally. Prudence is therefore both an intellectual and moral virtue. Given this, it is a virtue in the strict sense..

n the fifth article (IIª IIae, q. 47, a. 5) Thomas shows that prudence is a special virtue: a) because it differs from the intellectual virtues: 1) from the theoretical virtues by its object (the objects of prudence are singular, contingent things, not universal and necessary, as are the objects of science, wisdom and intellect); 2) of art, as it applies to external, material things, while prudence applies to the very subject of action; b) because it differs from moral virtues, which reside in appetitive potency, while prudence lies in intellectual potency. It follows that prudence is a special virtue.

In these first five articles we find a first conceptualization of prudence, which is summarized as follows: “[...] prudence refers to reason (a. 1) in its practical function (a. 2), applying to the singular action the moral principles (a. 3). It is a virtue in the strict sense (a. 4) and a special virtue (a. 5)” (Nascimento, 1993, p. 369).

In the next four articles (from 6 to 9) Thomas Aquinas determines what are the proper acts of prudence. In Article 6 (IIª IIae, q. 47, a. 6), he says that it is not prudent to set the ends, for they already pre-exist in natural reason, similar to principles in theoretical reason. The ends function in practical reason in a similar way to the way principles work in theoretical reason: some are self-evident (first principles); others are reached in the form of conclusion: in the highest things, by philosophical wisdom, bearing in mind the first principles; by science, in the nearest things, taking into account the first principles and those already obtained by theoretical wisdom. Similarly, the ultimate ends of moral virtues are previously given to natural reason (called synderesis), as good, happiness and which are not the object of deliberation. But certain knowledge is given to practical reason as conclusions (first analogy between the proper mode of theoretical wisdom and that of practical wisdom - prudence). This knowledge, concerning what is in view of the end, is the object of prudence, whose proper act is to apply the general principles (in this case the supreme ends of human action) to particular conclusions in the matter of action. Thus, the proper act of prudence is not to establish the end, but only to dispose what is in view of the end, which is a matter of deliberation. There still remains a hierarchy between prudence and the other moral virtues, for moral virtues tend to the ends established by natural reason in which they are aided by prudence (second analogy, between the proper mode of science and that of moral virtues).

Therefore, the same hierarchy that Thomas establishes between intellect, theoretical knowledge, and science is transposed into the realm of action: natural reason (synderesis) grasps (predetermines) the supreme ends of human action (the good) that serve it as principles. On the basis of these ends (principles), practical reason (prudence) reasons (deliberates, judges, commands) and, on the basis of the first principles and conclusions of practical reason, directs the choices of will, for right reason in action..

As for synderesis, although the term does not exist (does not appear) in Aristotle, what the term designates in Thomas Aquinas seems to us present in Aristotle.:

The word synderesis would be a deformation of synteresis derived from syn teréo, which can be translated as conserving. Hence, J. Ferrater Mora says that ‘it was common in many authors to understand synderesis as conservation in the consciousness of knowledge of the moral law [...]’ (Nascimento, 1993, p. 373, emphasis in original).

Aristotle's historical time is distinct from the historical time in which Thomas Aquinas lived, implying variations in languages and beliefs. However, some questions present in his works can be approximated: a) just as, in Thomas Aquinas’ concept of synderesis, for Aristotle it is not reason, either theoretical or practical, which establishes the supreme end (the happiness) to human action, it is an end in itself, it is not the object of deliberation, nor is it reached as a conclusion. It remains, then, that it pre-exists in reason; b) also for Aristotle, virtues are not an invention of the intellect, nor of the will, they pre-exist to any reasoning but are only apprehended by reason. They are part of the ‘nature’ of the human being or, as Heidegger (1983) would say, man's way of being. And it is as moral being, therefore, endowed with virtues, that man manifests (reveals, shows) his essence, the truth of his being; c) also for Aristotle, the specific end of each particular virtue is found by practical reason, in the form of conclusion (it does not invent it), based on the ultimate end of human action; d) also for Aristotle, the deliberation of practical reason (phrónesis) will be about the specific way to reach the good end in each singular case. We also believe that this can be taken, which seems to us common to Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, and which the latter called natural reason or synderesis, as a background to understand practical reason in Kant.

We believe that attention and estrangement should be maintained in Thomas Aquinas’ concept of synderesis with regard to Aristotle, seeking to understand and preserve the novelties he introduces while reconciling Aristotle with the Augustinian tradition. But it seems to us that the concept of synderesis is rather a mediation for working with Aristotle's thought in a very different historical environment (éthos) from which it was generated, rather than adding something strange to Aristotle in the sense of the theoretical framework that underlies the concept of prudence. The notion of éthos, which embraces tradition, ethical conflicts, and the way in which ethical living as a materiality of virtues in human experience takes effect, helps us to preserve both the theoretical and the specificities of the world that each one experienced. It also helps us not to make the work of thinking in the ethical field a mere abstract, detached and ineffective exercise.

From the other articles in question 47, from the seventh to the sixteenth (ten in all), let us see how articles 7, 8, and 15 allow us to more closely relate prudence and autonomy with regard to education in the ethical discussions in Thomas Aquinas.

In Article 7, the term ‘mean’ requires special attention. The question is: “[...] whether it is prudence to establish (find - trouver) the mean in moral virtues” (Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, IIª IIae, q. 47, a. 7). As we have said, the term mean does not refer to what is in view of an end, which in Portuguese can be said to be the means to an end. Here the term mean means the equilibrium point between extremes, the median, also called in Portuguese the middle ground, which for Aristotle is the main characteristic of virtue. It would also be important not to confuse it with mediocre or ‘lukewarm’, which is not, for Aristotle or Thomas Aquinas, a virtuous behavior, but already means a moral deficiency of habit resulting in lack of action, positioning, and as such should be corrected by exercise. The equilibrium point of virtuous behavior is a constant care not to fall into excess (of strength, bravery, pleasures, spending), nor to remain lacking (weakness, fear, indifference or coldness, greed). It requires boldness and admits changes (or revolutions) but seeking the best way, assessing, calculating risks (deliberating and judging), and ordering action (prescribing).

In addressing this question (IIª IIae, q. 47, a. 7) Thomas Aquinas follows Aristotle closely , for to conform action to right reason is the proper end of moral virtues. And such an end (the equilibrium point) is dictated by natural reason. Knowing what it is and how to strike the balance in every particular situation or circumstance, however, is not given in natural reason for these are the 'human things' of the 'human circumstance' concerned with practical reason (prudence). In the body of the article he says: “[...] indeed, even though attaining the mean is the end of moral virtue, yet what is the medium is only found by the right disposition of what is in view of the end” (Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, IIª IIae, q. 47, a. 7). The third argument in question 7 says that morality tends to the middle ground operating in the mode of nature, while prudence operates in the mode of reason. In his answer Aquinas shows that the natural inclination (from virtues to the middle ground) always treats things the same way and is therefore insufficient, as the middle ground is not the same in every case, so prudence is required (Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, IIª IIae, q. 47, a. 7, ad 3m), because “[...] it is up to the ordering of prudence to determine how and through what the human being, in acting, observes the reasonable mean” (Nascimento, 1993, p. 372). For Lima Vaz, Aquinas’ deepening of the Aristotelian notion of mesotis or virtue as a ‘mean’ between vicious extremes, on the other hand, allows,

[...] unify the two classic notions: Aristotle's, in which virtue is defined as the teleiosis of being and the stoic, received by Augustine, according to which virtue is the good quality of the mind, by which one lives righteously (Lima Vaz, 2002, p. 233).

In Article 8 (IIª IIae, q. 47, a. 8), Thomas wants to know if command is the chief act of prudence. Briefly, he comes to the following conclusion: prudence is the right reason in actions; it follows that the principal act of prudence is the principal act of reason applied to our actions. This application to actions requires three acts: the first is deliberation, which implies research and discovery; the second is to judge what was found in the deliberation, calculating what is most appropriate for the particular case under consideration; the third act is to command (to prescribe), that is, to apply to the realization what was deliberated and what was judged as the act is directly implicated in the notion of prudence, since it is a practical reason. In replying to the third argument (IIª IIae, q. 47, a. 8, ad 3m), Tomas adds that to move as such is an act of will but it requires deliberation and judgment (commander implique motion accompagnée d’órdenation). Therefore it belongs to prudence to command (to prescribe) but the motion (to move to act) requires the will.

Lima Vaz (2002, p. 227, emphasis in the original) shows us that

Thomas Aquinas, in line with the Aristotelian tradition, affirms a relationship of intercausality in the structure of the free act between reason and will, and reason enjoys relative priority in the order of the ‘formal and final’ cause and the will has priority in the order of the ‘efficient’ cause.

In article 15 of question 47 (IIª IIae) a very important theme appears. In it Thomas Aquinas demonstrates that prudence is not in us by nature, that is, it is not innate to humans but is acquired by education and exercise. This is why he states that although the first principles, both in theoretical and practical reason, are given to us by nature, the other principles are attained by us through experience or instruction. Moreover, while one may have a natural inclination toward right ends, the ways of accomplishing an end in the realm of human things are not determined, they are subject to all sorts of variations, concerning variations between people and things to do (the different actions) and only experience and exercise can provide the knowledge necessary for prudence, because its object does not depend on any natural law.

In the body of article 3 of question 49 of IIª IIae, Thomas Aquinas takes up the theme of experience, saying that prudence is a necessary matter to enlighten others and, among all, the old are the most suitable (qualified) to clarify the others for they have attained the healthy intelligence of action-related ends, since their experience makes them see the principles. In answering the second argument of the same question (IIª IIae, q. 49, a. 3, ad 2m) he says that docility, like the other qualities concerning prudence, are natural in capacity, but study and exercise concur strongly and effectively to perfect it. And in this sense, man with care, assiduity, and respect applies his spirit to the teachings of elders, avoiding neglecting them for laziness or despising them for pride. In reply to the third argument (IIª IIae, q. 49, a. 3, ad 3m) Thomas Aquinas says that by prudence man commands not only others but also himself (commanding in the sense of guiding, conducting, ensuring the direction and correctness of action, governing oneself in actions).

Surely the principle of autonomy of philosophy in relation to theology is clearly shown in Thomas Aquinas’ approach to prudence. Although it is a theological Summa, it is intensely shown to be a free exercise of thought, markedly a philosophical practice. That is in relation to the form. As for content, Thomas Aquinas is insistent on securing freedom for human reason, both in ‘seeking’ the best way to accomplish his ends and in ‘choosing’ how to act. According to Lima Vaz (2002, p. 239, emphasis in the original),

The Aristotelian phrónesis, raised and dilated to the universal horizon of human things to which ‘prudence’ extends (q. 47 a. 2), becomes the next objective norm of moral action, exercising a ‘mediating’ function between the objectivity of the law and the subjective act of the ‘decision’.

It is also worth noting that prudence is not an individualistic or selfish proposition. It deals with both the individual and the collective good, as studied in question 50 of IIª IIae. It is as fundamental to the individual as it is to collective experiences. This aspect is protected by both Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, showing that it is difficult to be happy, just, generous, and kind living in isolation, unrelated to others because these virtues require the presence, coexistence, being in the world with others, including respecting the limits and needs of nature: “[...] this is the part that is up to prudence, as to making man for political life” (Souza Neto, 1995, p. 28).

Final considerations

The concept of prudence of Thomas Aquinas allows us to remember that the human being, in his experience in the world, is a totality, composed of three specific spheres: an intellectual one in which the theoretical researches are carried out, whose final result is the conditions of truth and truth as such, along the lines of philosophy (sophos) and science; a moral sphere, in the realm of human action itself, in which man's own acts are carried out, endowed with freedom and responsibility, also called the sphere of ethics, in which man produces himself; an artistic, productive sphere in which material and cultural goods are produced. These three orders need to be in balance so that human beings do not break apart, losing their unity as a whole. More than that, prudence insists that the priority in the three spheres is given to the moral one, which deals with the destiny of the human being, his integrity and his happiness..

More specifically in the field of education (broadly, not just school), prudence in Thomas Aquinas makes us see the central place that formation, preparation, training, exercise in the field of practical wisdom (moral action) must occupy. The ethical component (practical wisdom) is a constitutive part of the human being in any and all circumstances in which we are or act, so it is important to rethink themes of this nature. In many contemporary educational, social, cultural, political, affective, and sexual environments, the importance of the notion of prudence (with its key terms such as virtue, value, ethics, self-exercise) does not seem to receive proper attention. The work of Thomas Aquinas helps us understand how education and prudence are related. Deepening this issue can prevent education from losing its way between epistemological foundations and pedagogical techniques, and human formation in general from being reduced to technical effectiveness in capitalist and market machinery..

Therefore, from the analyzed work of Thomas Aquinas, we can see that prudence has to do with decision making. The “forgetfulness” of the importance of this concept and the possibilities it offers us for thinking about contemporaneity has shown catastrophic effects: we make decisions and do things without measuring the moral, environmental and cultural consequences; we no longer have preparation, training, to deliberate, to judge and to prescribe taking into account the totality of human action. Thus, we are obliged (conditioned by our limitations, spiritual poverty, ignorance of practical knowledge) to make our choices with fragmented, partial views, such as profit, personal advantage, following fashion, immediate pleasure, among other things. All this makes us less free, without autonomy in our own acts, dependent on and subject to the dominance of technology, consumerism, exploitation (financial, intellectual, moral, cultural, labor) and the market. Nor do those who occupy important positions for decision-making on the direction of society, the population, such as country presidents, prime ministers, senators, owners or administrators of large international conglomerates have sufficient training in this sphere. We are characterized by being efficient in two of these spheres, the theoretical and the technical, but very deficient in the sphere of the mean, ethics. The concept of prudence in Thomas Aquinas is an important device in education to cope with the current difficulties.

The ever faster advancement of technology and the media makes us make ever more accurate and faster decisions. The vacuum formed by the ‘forgetfulness’ of ethical and moral formation produced the society of technique or cybernetics (Heidegger, 1983, p. 72). So we have, on the one hand, a society that demands ever faster and more efficient decisions and, on the other, a human being less and less ethically prepared for this activity. Perhaps if we resumed the formative practice, supported and extended by the concept of prudence, which is also called the theory of human action in the sense of decision-making, we would not only cover this gap that currently makes us poorer and spiritually limited but we would become more autonomous and responsible in our personal and professional, private and public, loving and political decisions. In this way, we would gain a new scope for freedom, not absolute, nor trivialized, but critical, in that, through education and exercise, we reach autonomy to decide for ourselves the direction, the moment, the intensity, the duration and the value of each of our actions. Systematic study of the History and Philosophy of Education can help to achieve this and, in this sense, the concept of prudence, as discussed here, can be an important starting point.

REFERENCES

Châtelet, F. (1974). História da filosofia: idéias, doutrinas. A filosofia medieval, do séc. I ao séc. XV (Vol. 2, Librairie Hachette, trad. e ed. da primeira edição francesa). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Zahar. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (2004). A hermenêutica do sujeito. Curso no Collége de France de 1981-1982 (M. A. Fonseca, S. T. Muchail, Trad.). São Paulo, SP: Martins Fontes. [ Links ]

Gilson, E. (1995). A filosofia na idade média (E. Brandão, Trad.). São Paulo, SP: Martins Fontes. [ Links ]

Gomes, R. (2001). Crítica da razão Tupiniquim (12a ed.). Curitiba, PR: Criar Edições. [ Links ]

Heidegger, M. (1983). Conferências e escritos filosóficos. São Paulo, SP: Abril Cultural. [ Links ]

Le Goff, J. (1993). Os intelectuais na Idade Média. São Paulo, SP: Brasiliense. [ Links ]

Lima Vaz, H. C. (1986). Escritos de filosofia. Problemas de fronteiras. São Paulo, SP: Loyola. [ Links ]

Lima Vaz, H. C. (2002). Escritos de filosofia IV. Introdução à ética filosófica 1 (2a ed.). São Paulo, SP: Loyola. [ Links ]

Loraux, N. (1992). Elogio do anacronismo. In A. Novais (Org.), Tempo e história (p. 57-70). São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Nascimento, C. A. R. (1993). A prudência segundo Santo Tomás de Aquino. Revista Síntese Nova Fase, 20(62), 365-385. Recuperado de https://faje.edu.br/periodicos/index.php/Sintese/article/view/1316/1712 [ Links ]

Nascimento, C. A. R. (2003). Santo Tomás de Aquino. O Boi Mudo da Sicília (2a ed. rev.). São Paulo, SP: Educ. [ Links ]

Nunes, R. A. C. (1979). História da educação na Idade Média. São Paulo, SP: Edusp. [ Links ]

Oliveira, T. (2008). Os mosteiros e a institucionalização do ensino na Alta Idade Média: uma análise da história da educação. Série-Estudos (UCDB), 25, 207-218. Recuperado de http://www.serie-estudos.ucdb.br/index.php/serie-estudos/article/viewFile/308/161 [ Links ]

Souza Neto, F. B. (1995). Introdução. In T. Aquino. Escritos políticos (F. B. Souza Neto, Trad.). Petrópolis, RJ, Vozes. [ Links ]

Teixeira, I. S. (2014). O Intelectual na Idade Média: divergências historiográficas e proposta de análise. Revista Diálogos Mediterrânicos, 7, 155-173. Recuperado de http://www.dialogosmediterranicos.com.br/index.php/RevistaDM/article/view/114 [ Links ]

Teixeira, I. S. (2015). Aquinas’ Summae Theologiae and the moral instruction in the 13th century. Acta Scientiarum, 37(3), 247-257. Doi: dx.doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v37i3.23509. [ Links ]

Tomás de Aquino, Santo. (1934). Suma teológica (A. Fontana, Trad.). São Paulo, SP: Imprimatur Mons. Ernesto de Paula. [ Links ]

Verger, J. (1990). As universidades na Idade Média (F. M. L. Moretto, Trad.). São Paulo, SP: Unesp. [ Links ]

Verger, J. (1999). Homens e saber na Idade Média. Bauru, SP: Edusc. [ Links ]

Vignaux, P. (1994). A filosofia na idade média (M. J. V. Figueiredo, Trad.). Lisboa, PT: Editorial Presença. [ Links ]

Received: May 03, 2019; Accepted: September 04, 2019

texto em

texto em