Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Educação em Questão

versão impressa ISSN 0102-7735versão On-line ISSN 1981-1802

Rev. Educ. Questão vol.61 no.70 Natal out./dez 2023 Epub 06-Mar-2024

https://doi.org/10.21680/1981-1802.2023v61n70id34410

Artigo

Community school practices: a key to construct a curriculum for cultural diversity in Colombia

Prof.ª Surjey del Carmen Montes-Pérez, Universidad del Norte (Barranquilla, Atlántico, Colombia), Doutoranda do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Instituto de Estudios Superiores, Grupo de Pesquisa Global South, Grupo de Pesquisa Lenguaje y Educación, Grupo de Pesquisa Network of Critical Action Research in Education, Email: surjeym@uninorte.edu.co

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3965-926X

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3965-926X

Prof.ª Dr.ª Nayibe Rosado-Mendinueta, Universidad del Norte (Barranquilla, Atlántico, Colombia), Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Instituto de Estudios Superiores, Grupo de Pesquisa Global South, Grupo de Pesquisa Lenguaje y Educación da Universidad del Norte, Grupo de Pesquisa Network of Critical Action Research in Education, Email: nrosado@uninorte.edu.co

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1865-2464

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1865-2464

2Universidad del Norte (Colombia)

The development of ethnic education and the design of curricula relevant to the cultural identity of communities is a necessity in the Colombian context. This article shows the advances of qualitative research with a realistic ethnographic action research design. This study explores aspects of the written and lived curriculum that align or clash with the practices of the community served by a public ethno-educational institution in Colombia. It is based on cultural diversity, ethnic education, intercultural education, and intercultural curriculum. This realistic ethnographic action research comprises several moments. We report on the Exploration moment built with the educational community, sabedores, and leaders. The results highlight the potential of community school practices to align the curriculum, that ethno-educational pedagogical experiences and classroom projects clash with the general pedagogical model. Community school practices' role in constructing an intercultural and multilingual curriculum is emphasized.

Keywords Cultural diversity; Ethnic-education; Intercultural education; Intercultural curriculum

El desarrollo de la etnoeducación y, con ello, el diseño de currículos pertinentes a la identidad cultural de las comunidades es una necesidad en el contexto colombiano. Este artículo muestra avances de una investigación cualitativa con diseño de investigación-acción etnográfica realista. Este estudio explora aspectos del currículo escrito y vivido que se alinean o chocan con las prácticas de la comunidad que atiende una institución etnoeducativa pública en Colombia. Se fundamenta en diversidad cultural, etnoeducación, educación intercultural y currículo intercultural. La investigación-acción de corte etnográfica realista comprende diversos momentos. Se reporta el momento de Exploración construido con la comunidad educativa, sabedores, líderes y lideresas. Los resultados destacan el potencial de las prácticas escolares comunitarias para alinear el currículo; que las experiencias pedagógicas y proyectos de aula etnoeducativos chocan con el modelo pedagógico general. Se resalta el papel de las practicas escolares comunitarias para la construcción de un currículo intercultural y plurilingüe

Palabras clave Diversidad cultural; Etnoeducación; Educación intercultural; Currículo intercultural

O desenvolvimento da etnoeducação e, com ela, a elaboração de currículos relevantes para a identidade cultural das comunidades é uma necessidade no contexto colombiano. Este artigo mostra o progresso de uma pesquisa qualitativa com um desenho de pesquisa-ação realista etnográfica. Este estudo explora aspectos do currículo escrito e vivido que se alinham ou se chocam com as práticas da comunidade atendida por uma instituição pública de etnoeducação na Colômbia. Baseia-se na diversidade cultural, etnoeducação, educação intercultural e currículo intercultural. A pesquisa-ação realista etnográfica compreende vários momentos. Relatamos o momento de Exploração construído com a comunidade educacional, especialistas e líderes. Os resultados destacam o potencial das práticas da escola comunitária para alinhar o currículo; que as experiências pedagógicas etnoeducacionais e os projetos de sala de aula entram em conflito com o modelo pedagógico geral. O papel das práticas das escolas comunitárias na construção de um currículo intercultural e multilíngue é destacado

Palavras-chave Diversidade cultural; Etnoeducação; Educação intercultural; Currículo intercultural

Introduction

The Political Constitution of Colombia (CPC) of 1991 acknowledges the Colombian nation's ethnic and cultural diversity (Colombia, 1991). This recognition implies an education that defends, knows, values, and enriches its own culture with the contributions of others in a dimension of cultural alterity, that is, in a respectful dialogue of knowledge and insights from diverse cultures that interconnect and complement one another (Artunduaga, 1997; Castillo Guzmán; Caicedo Ortiz, 2008). Colombian ethno-educational policy must pave the way to transcend from a mono-cultural system to one that recognizes and involves the faces and voices immersed in the Colombian educational system (Mena García, 2011). However, ethno-education has generated tensions in its implementation in Colombia, as it has not fully overcome the discrimination, stigmatization, and invisibility faced by Afro-descendants, Indigenous peoples, Rrom, and foreigners.

At the policy level, Law 115 of 1994, the General Education Law, in its Article 55, conceives of ethno-education, or education for ethnic groups, as "that which is offered to groups or communities that are part of the Colombian nationality and that possess their own and indigenous culture, language, traditions, and customs" (Colombia, 1994, p. 38). Title III (Chapter III) elaborates on the conditions of ethno-education with the aim of "[...] strengthening the processes of identity, knowledge, socialization, protection, and use of vernacular languages, teacher training, and research in all areas of culture" (Colombia, 1994, p. 38).

Therefore, ethno-education is a continuous educational process that involves strengthening diverse ethnic and cultural identities from the autonomy of the communities that construct their overall life project in environments where cultural diversity (CD) and interculturality are fundamental. Ethno-education is conceptualized as a "[...] transformative strategy focused on BEING, creating bridges of interculturality to strengthen self-recognition, otherness, citizenship competencies, values, alterity, sustainability, and respect" (Gobernación de Antioquia, 2015, p. 11). In this way, it should serve as a tool for change in educational contexts, fostering respect, recognition, and the strengthening of the principles and values underpinning ethno-education itself, and as a starting point for the design of relevant curricula in these educational contexts.

This article presents the progress of a research project to establish the dynamics that enable the collective construction of an intercultural and multilingual curriculum. It focuses on a curriculum that strengthens the cultural diversity of a community composed of Afro-Colombian, Palenquera, mestizo, Indigenous, and Venezuelan migrant populations, served by a public ethno-educational institution (IEPC) in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia (Montes Pérez, 2022). The challenges of enhancing the cultural diversity of this population and the complexities of designing an intercultural and multilingual curriculum in urban contexts drive this research. Specifically, we aim to explore, "Which aspects of the written and lived curriculum of the IEPC align with or clash with the practices of the community served by the institution?"

Strengthening cultural diversity through the curriculum

The relationship between cultural identity and curriculum in the educational context is fundamental for understanding and strengthening cultural diversity (CD). Identity is a set of traits that characterize an individual or group, constantly changing and in ongoing negotiation with the environment (Real Academia Española, 2001; Walsh, 2005). The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) defines culture as a set of distinctive features that characterize a society, encompassing ways of life, value systems, traditions, and beliefs (UNESCO, 1982, 2002). This conception encompasses a variety of worldviews that seek respect and coexistence.

Cultural identity (CI) also encompasses a political dimension, especially in Indigenous and Afro-descendant contexts, where ethno-development, i.e., self-government and self-management, are seen as means to overcome imposed cultures and make independent decisions (Bonfil, 1982; Castillo Guzmán; Caicedo Ortiz, 2008; Orozco-López, 2018; Pardo, 2002; Rojas, 2011). Therefore, the rescue, promotion, recognition, preservation, and strengthening of CI are among.

Within this framework, Cultural Diversity (CD) is woven, representing the encounter of multiple cultures in a context, each distinguished by its unique characteristics (Montes Pérez, 2022). UNESCO (2002) defines CD as the multitude of forms through which cultures express themselves in societies, transmitting the cultural heritage of humanity through various methods: artistic creation, production, dissemination, distribution, and enjoyment across generations. This is because culture evolves and manifests in various ways depending on time and space, "[...] as an open and dynamic process, a relational process linked to power relations" (Grimson, 2008, p. 61). It is about recognizing differences without engaging in discrimination or power games.

Dietz, Mateos Cortés, Jiménez Naranjo, Mendoza Zuarry (2009) and Dietz; Mateos Cortés (2011) understand CD as the product of the presence of ethnic and/or cultural minorities or the establishment of new migrant communities within contemporary society. These authors illustrate the complexity of CD as a product of intercultural relations among different ethnic and cultural groups at the national and international levels, incorporating intercultural, multicultural, and cross-cultural aspects into our current society. Thus, CD is conceived as a web of cultural differences that territorialize, deterritorialize, and reterritorialize in the process of hybridization generated in each space.

In this context, an understanding of the curriculum determines how others are perceived, possible interactions, reactions, and relationships that either favor or disadvantage, modes of participation, messages of acceptance, adaptation, respect, and rejection (Banks, 1989). In this sense, it is necessary to establish the aspects that characterize a curriculum from the perspective of CD, interculturality, and multilingualism. This way, the curriculum can assist the educational community in conferring sociocultural meaning and significance to their experiences, especially in an urban context marked by vulnerability.

The findings in the literature reveal practices, strategies, and methods that are considered essential for transforming practices in intercultural, multicultural, and ethno-educational contexts. Among these perspectives are the works of De Ávila Torres, Simarra Obeso (2012), Cabarcas Bello (2017), Carreño Bolívar (2018), and Perneth Pareja, Ortiz Fonseca, García Becerra (2019). These studies share a common emphasis on the need to transform pedagogical practices towards the defense, strengthening, and inclusion of CD in the design and implementation of strategies that align with the communities served by the teachers. The studies by Ricardo (2013), Ricardo Barreto, Llinaz Solano, Hernández Beleño (2017), and Gómez-Zermeño (2018) highlight the importance of the affective dimension and sensitivity to intercultural or multicultural education and the CD of the school actors.

Research design-realist ethnographic action research (REAR)

The research approach is qualitative, with an ontological and epistemological stance grounded in critical realism (CR) and Southern epistemologies. CR is a philosophical paradigm that emerged from the ideas of Roy Bhaskar (1998), (2008) as a response to the dichotomy between positivism, constructivism, and intermediate paradigms (post-positivism, critical theory, pragmatism). On the other hand, Southern epistemologies use a decolonial critical perspective that is indigenous and autonomous, aiming to unveil social reality (Hall, 2014; Santos, 2011). An integration of these paradigms is achieved in this research.

This qualitative research is understood as a community activity aimed at pursuing the common good and a social practice that involves reflection on what is done and what is investigated (Elliott, 2000; Martínez Miguélez, 2000). Realist Ethnographic Action Research (REAR) (Montes Pérez, 2022) is the central method used to address the question: What are the dynamics that enable (or hinder) the collective construction of an intercultural and multilingual curriculum? Action research, rooted in the socio-critical paradigm, has an orientation towards change and the transformation of reality by bridging theory and practice (Creswell, 2009; Elliott, 2000; Fals Borda, 2018, 1994; Johnson; Christensen, 2008). On the other hand, ethnography allows for the description, interpretation, and reflection on reality from the voices of different actors in the specific context where it unfolds (Coulon, 1995; De Tezanos, 1998; Dietz, 2011; Woods, 1987). Realist Evaluation (RE) is a critical realist method based on systems theory and critical theory (Pawson; Tilley, 1997; Tilley; Pawson, 2014). RE establishes the causality of social issues and the agency of communities in solving these problems, aiming to unravel the effectiveness, impact, and effects of programs, projects, and interventions in society by bringing public policies into the spotlight (Parra, 2017, 2019).

The REAR research design at the macro level is developed in five stages: opening, exploration, collective construction, implementation, and evaluation-reflection (Montes Pérez, 2022). The Exploration Stage, conducted in the second semester of 2022, is reported here. Additionally, the question "What aspects of the written and lived curriculum of the IEPC align or clash with the practices of the community served by the institution?" is addressed with the participation of members of the educational community, as well as traditional knowledge holders, and community leaders to highlight their ancestral educational practices in educational processes, particularly within the social, political, historical, territorial, and cultural context of the IEPC.

Regarding ethical considerations, criteria for accessibility were established for teachers, school leaders, students, and parents with explicit expressions of participation and belonging to the institution and the surrounding community, including ancestral knowledge holders, community leaders from the neighborhoods surrounding the IEPC, where part of the students and their families live.

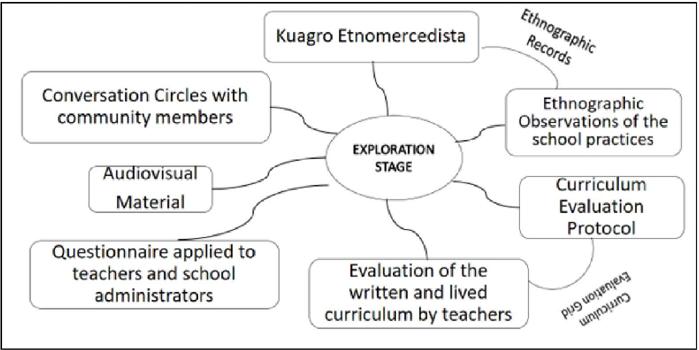

To collect information, strategies such as Kuagro Etnomercedista (De Ávila Torres, 2017; De Ávila Torres; Simarra Obeso, 2012), Curriculum Evaluation Protocol including the Curriculum Evaluation Grid (Banks, 2014; Montes Pérez, 2022), Ethnographic Observation using Ethnographic Records (De Tezanos, 1998; Woods, 1987), Audiovisual Material, and Conversation Circles (Arias Monge, 2012) were employed (see Figure 1). The strategies are detailed below.

Kuagro Etnomercedista

A group of six teachers, members of the Institutional Ethno-education Committee, was formed in August 2022. Four meetings were scheduled and conducted during the second semester, one in-person and three virtual via Teams. These meetings allowed for decision-making regarding collecting information on school practices through ethnographic observations. They also explained the study's components, analysis strategies, epistemic categories, and how to complete records. A WhatsApp group was created to disseminate project information.

Ethnographic Observations

Simultaneously, members of the Kuagro Etnomercedista completed ethnographic records based on the work of De Tezanos (1998) and Montes Pérez (2022). These records were designed for on-site observation of school dynamics and practices. Author 1 held conversations with each member of Kuagro to address any concerns about completing this instrument. Some members recorded audio and video of their observations, which were shared via WhatsApp. These dynamics helped build trust, and the teachers wrote 12 ethnographic records.

Curriculum Evaluation Protocol

The review and documentary analysis of the written curriculum followed a protocol designed based on planned tasks: a) Collection of the Community Ethno-educational Project (PEC) and institutional documents; b) Information systematization; c) Documentary analysis; and d) Emerging categorization (Montes Pérez, 2022). Initially, 261 institutional curriculum documents were collected. Selection criteria for these documents included being part of physical or digital IEPC archives, having dates and being complete, and having been created between 2014 and 2022. These documents were classified into 11 folders for systematization according to aspects such as PEC, Area Plans, and Minutes of Teacher/Parent Meetings, for instance. Documentary analysis was conducted with the assistance of Atlas.ti 22, which facilitated the categorization process.

Audiovisual Material

This strategy included photos and videos from Kuagro sessions, community school practices, and conversation circle meetings collected during the exploration stage. This material was organized, systematized, and analyzed cyclically, holistically, openly, and flexibly.

Conversation Circles (Arias Monge, 2012)

The first circle consisted of 40 teachers from IEPC branches, which functioned as a general assembly and institutional development meetings. They explored the dynamics of school practices, collected information about their lesson plans, and applied the curriculum evaluation grid. The second circle was organized with ten parents from different grades and branches. They completed the evaluation grid, and a WhatsApp group was created to inquire about their educational thoughts and desires for their children.

Several analysis strategies were employed to analyze the collected and systematized data, including documentary analysis, critical discourse analysis (Bernstein, 1986; Cook, 1990; Van Leeuwen, 2008), and interpretative-reflective analysis (De Tezanos, 1998; Woods, 1987).

Documentary Analysis

Its purpose was to analyze the written curriculum and unveil its alignment with ethno-educational policy, intercultural education, cultural diversity, indigenous and disciplinary knowledge, school and community practices, and the community life project. This analysis involved tracing previous and emerging categories and subcategories in the Community Ethno-educational Project (PEC) and the collected and systematized institutional documents (261). This process was carried out using Atlas.ti, version 22, which allowed for organization, processing, careful reading, and interpretation of the documents. This tool was also used to generate direct quotations, semantic networks, and various graphs and appropriately code this information.

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA)

CDA was conducted to uncover the dynamics that shape the relationships among teachers, school administrators, administrative and support staff, students, parents and guardians, knowledge holders, community leaders, and others who converge in an IEPC. It is based on discourse theory (Cook, 1990), pedagogical and contextualized discourse (Bernstein, 1986), and discourse as recontextualized social practice (Van Leeuwen, 2008).

CDA was carried out in four phases. The first phase involved systematizing minutes, videos, and researcher's notes from Kuagro Etnomercedista workshop-type meetings and conversation circles. This data included ethnographic records of observations of school practices. The second phase focused on identifying and categorizing speech acts in these documents using Atlas.ti 22. Dimensions and functions of speech acts were classified. The third phase comprised the critical analysis of categorized speech acts to unveil attitudes, beliefs, conceptions, and perspectives underlying the school discourses analyzed in this study. The fourth phase involved reporting findings based on school dynamics in the context of IEPC.

Interpretative-Reflective Analysis

This analysis reveals the reality of the observed community school dynamics and practices. The Ethnographic Record, a fundamental research instrument, includes an interpretation section aligned with previous categories and subcategories. It also includes a comments and reflections section, where teachers from Kuagro Etnomercedista randomly conducted their ethnographic observations of school practices. Later, Author 1, with the support of colleagues and additional assistance from Atlas.ti 22, conducted an interpretative-reflective analysis of the resulting material from the observations.

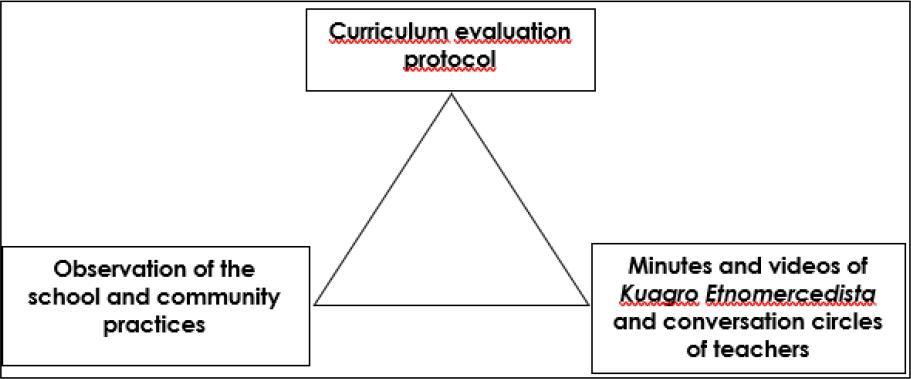

In sum, multiple data collection and analysis strategies were used to compare these data with emerging categories and subcategories to ensure the credibility and dependability of the findings and results based on them (Creswell, 2009; Johnson; Christensen, 2008). Figure 2 illustrates the triangulation performed.

Source: Taken from Montes Pérez (2022). Triangulación en el Momento de Exploración p. 164. Adaptado de Mertler (2009). Figure 5.6 Triangulation of Three Sources of Data, p. 116.

Figure 2 Exploration stage triangulation

Results and Discussion

The comparison of collected and analyzed data revealed the elements of the IEPC's written and lived curriculum, which emerged from the voices of the educational community, the community ethno-educational project, and institutional documents. Table 1 presents the emerging elements of the current curriculum.

Table 1 Elements of the current written and lived curriculum

| Elements of the IEPC's written and current curriculum | Tendencies in data analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Written curriculum evaluation | Kuagro EM & conversation circles | Observations of the school practices | Total | % | |

| Ethno-educational policy in the school curriculum | 77 | 14 | 19 | 110 | 8,8 |

| General educational policy in the school curriculum | 63 | 2 | 12 | 77 | 6,2 |

| School environment and the fostering of the CD | 141 | 62 | 22 | 225 | 18 |

| Ethno-educational and intercultural elements -school curriculum | 121 | 45 | 129 | 295 | 23,6 |

| General elements of the school curriculum | 234 | 9 | 145 | 388 | 31 |

| Intercultural competence of the community | 73 | 42 | 40 | 155 | 12,4 |

| Total | 1250 | 100 | |||

Source: Own construction with the support of a code trend diagram on Atlas.ti 22.

One of the elements of the school curriculum aligned with school practices is the ethno-educational policy established in school documents such as the Community Ethno-Educational Project (PEC) and cross-institutional projects (77), minutes and videos from the Kuagro Etnomercedista and conversation circles (14), as well as observations (19). An assortment of regulations was analyzed, which stems from the 1991 Political Constitution of Colombia (CPC) and the laws and regulatory decrees related to ethno-education. Furthermore, this assortment is guided and complemented by the general educational policy (with occurrences of 63, 2, and 12) found in Law 115 of 1994 and its decrees, guidelines, and quality standards. As explained by León García León (2012), García Rincón (2015), and Perneth Pareja, Ortiz Fonseca, and García Becerra (2019) in their analysis of ethno-educational policy and its impact on schools, the written curriculum possesses legal tools to implement ethno-education in the urban context of Cartagena de Indias.

As an identified curricular element, the school environment (18% occurrences) is conducive to respecting, defending, and strengthening cultural diversity. This environment is embedded and manifested in the school atmosphere, which is positively sensitive to cultural diversity. It encompasses extracurricular activities, pedagogical sessions, classroom projects, cross-institutional projects, bulletin boards and murals, festivals, commemorations, celebrations, physical education programs, recreational activities, sports, and arts, as well as the participation of educational community members in school life.

This aligns with the intercultural competence of the community (with 12.4% of occurrences), manifested in their attitudes, beliefs, skills, abilities, and knowledge regarding the cultural diversity of the population and respect for differences observed in school practice observations. However, there is a need for more adaptable, sensitive, and diversity-strengthening environments that lead to critical reflection on the conditions of development and the generation of opportunities for the defense of cultural diversity in school practices.

It is also reflected in the dichotomy between teachers with general education and those with ethno-educational training in the way they carry out their teaching practices (Fals Borda, 2018; Freire, 2005). Ethno-educator teachers display greater sensitivity, and respect, and strengthening of the community's diversity. General education teachers are in the early stages of sensitivity development.

These results indicate an initial development of intercultural sensitivity in which cultural diversity is recognized, and both one's own and others' differences are respected. Studies on intercultural/multicultural awareness and development suggest that in contexts with initial or low levels of community members' intercultural competence (Gómez-Zermeño, 2018; Hammer; Bennett; Wiseman, 2003; Ricardo Barreto; Llinás Solano; Hernández Beleño, 2017; Ricardo Barreto, 2013), a more profound process of self-recognition of cultural identity and the consequent critical respect, defense, and strengthening are required. (Giroux, 2013).

On the other hand, the analysis results show a hybrid curriculum between general elements (31% occurrences) and ethno-educational and intercultural elements (23.6% occurrences). This curriculum includes ethno-educational pedagogical experiences and classroom projects but is based on a general pedagogical model divided into fundamental and compulsory areas and subjects. In practice, it is moving toward an intercultural curriculum in some areas such as Social Sciences, Spanish Language, English, Natural Sciences, Arts, and Physical Education.

Ethno-educational and intercultural elements such as strategies, methods, ethno-educational practices, evaluation systems, teaching methods, and motivation suitable for the ethnic and cultural diversity of students, student welfare programs for diversity, and parental involvement in school life, collide with general elements of the school curriculum such as the pedagogical model, study plans, general fundamental and compulsory areas and subjects. The former has a lower impact on the curriculum than the latter. This is due to the history of the IEPC itself and the gradual transformation of the curriculum from general to ethno-educational. The promotion of a plurilingual curriculum has been observed in festivals, commemorations, and celebrations specific to ethnic and cultural diversity, as stated in the Rectoral Resolution 010 of 2019.

Emerging community school practices

This section will discuss the school practices that align with a context-based intercultural curriculum. Six institutional cross-cutting projects have been identified among the community school practices, which run parallel to regular classes.

Firstly, the School Democracy Project, led by Social Sciences teachers and supported by Student Welfare and other departments, involves activities related to the School Government. It includes the planning, organizing, and developing elections for its members. This project continues with meetings and training for the elected leaders. The documentation and systematization of this project, such as guidelines, candidate and election records, publication of results to the entire community, campaign activities, inauguration, and programs written by each student candidate, makes it a highly visible and significant project for school life.

Secondly, the School Environmental Project (PRAES), led by the Natural Sciences team and with cooperation from other departments, is responsible for promoting, preventing, and caring for the school environment. This project is divided into subprojects focusing on water conservation, electricity conservation, solid waste management, and recycling in general. It is implemented in all five branches of the IEPC through workshops, campaigns, and environmental events. Students actively participate through ecological groups, environmental committees, and as collaborators.

Thirdly, the Bilingualism Project, led by the Foreign Language Department - English, emphasizes learning English as a foreign language from elementary to eleventh grade. It combines communicative competence, interculturality, disciplinary topics, and local and foreign cultures using various methodologies outlined in the curriculum plan. It creates a bilingual environment in the school through activities such as Spelling Bee, English Friday on the school radio, and English Day/Week, as well as through bilingual murals, posters, and notices in both Spanish and English. However, there is a need to link the Palenquero language and indigenous languages to this project.

Fourthly, the Communication Project, led by the Spanish Language department and with collaboration from Art, Computer Science, and English, encompasses different ways of communication within the school. This project includes the INSEMA Magazine, INSEMA Stéreo Radio Station, participation in the Leer el Caribe program, and classroom projects within the Spanish Language department, such as Cangrejo Moro and literary analysis. The project involves various departments and external collaborators such as the District Education Secretary, the Caribbean Writers' Society, the El Universal newspaper, and some city radio stations.

Fifthly, with support from the Student Welfare team and the Ethics and Values, Religious Education, Philosophy, and Social Sciences departments, the Potters of Healthy Coexistence Project is responsible for school coexistence and disseminating, promoting, and preventing minor and significant disciplinary offenses. They also provide support through school vigilance groups and peace facilitators in preventing or addressing situations and violations of the rules established in the Coexistence Manual (Mercedes Ábrego Educational Institution, 2014).

Lastly, the Cultural Cabildo Project, led by the Social Sciences department, promotes folk dances in the IEPC. This project aims to strengthen the cultural identity of the educational community of Cartagena de Indias through the respect, defense, and understanding of the customs and traditions of the region and the language of dance that is part of their identity. The Cabildo expresses the culture and heritage of Afro-descendants, Indigenous people, and Europeans. Dancers are selected annually from different secondary grades to form the group that participates in the institutional Cabildo. This year, primary grades have also been included.

These cross-cutting school practices have a significant impact on the educational community. These results align with the findings of Ortiz Fonseca, Rodríguez Gaitán, Perneth Pareja (2018) and Perneth Pareja, Ortiz Fonseca, García Becerra (2019), who found that integrated classroom projects are contextualized and relevant to the needs of the population for the development of ethno-education and IE in rural and urban contexts in the Caribbean region. While these reported contextualized experiences are valuable, they do not cover the entire curriculum, unlike the scope of this study.

Other school practices include pedagogical meetings (classes), breaks, festivals, celebrations, and commemorations, pedagogical experiences and classroom projects, extracurricular activities, school coexistence, institutional development weeks, evaluation and promotion committees, and meetings of teachers and school leaders. These practices are related to the lived curriculum and some documents that make up the written curriculum. In these practices, student participation predominates, along with teachers, school leaders, parents, guardians, and the Student Welfare team. Occasionally, some administrative and support staff members and other community members are also involved. The participation of knowledgeable individuals, leaders, and community figures occurs during training sessions for teachers. School leaders, welfare teams, and administrative personnel participate during institutional development weeks or when festivals and celebrations related to ethno-education and cultural diversity are held.

As explained by De Ávila Torres, Simarra Obeso (2012), Cabarcas Bello (2017), Carreño Bolívar (2018), Gómez-Zermeño (2018), and Perneth Pareja; Ortiz Fonseca; García Becerra (2019), it is only through the participation of everyone that the integration of differences can be achieved in a process of ethno-relativism that involves us all.

Final considerations

The exploratory phase of this study revealed the initial dynamics that enable (or hinder) the collective construction of an intercultural and plurilingual curriculum, as well as the community school practices that strengthen the cultural diversity of the educational community, especially the identity of the Afro-Colombian and Palenquera, indigenous, mestizo, and migrant populations served by a public ethno-educational institution in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia.

The active participation of community members in school practices is emphasized, involving all actors regardless of their cultural identity. In this way, the identified school practices become examples of interaction within the institution's diversity: all its members converge in the same space to make school dynamics their own. They "wear the shirt" (or get involved) and give their best. Students from different grades not only attend but also organize presentations for events. Their commitment to their institution is evident as they continue to enrich and strengthen their culture and identity.

These results show an initial development of intercultural sensitivity in which cultural diversity is recognized, and differences, whether one's own or others are respected. For this reason, it is possible that activities that enrich school practices can be transformed into intercultural spaces where reflection on the purpose of community life, problem-solving, and context-based needs can take place; they can become problematizing axes. The transition can occur in these spaces from doing to praxis, generating critical and reflective dialogues and conversations about these practices. Various issues can be explored, including how they influence self-recognition and respect for others, demonstrate the strengthening of the cultural diversity of the population, and how classroom processes can be further enhanced to relate subjects and areas in general to the lived curriculum.

As mentioned, ethno-educational pedagogical experiences and classroom projects clash with the general pedagogical model divided into fundamental and mandatory subjects. School practices can serve as a bridge or device to transition from a general pedagogical model to an intercultural and plurilingual pedagogical model. This model should contain the necessary elements for educational community members to construct an ethno-relativism process involving all of us.

In this regard, the emergence of an intercultural and plurilingual curriculum matrix that goes beyond subject divisions and strengthens diversity while interweaving disciplinary concepts and ancestral knowledge, worldviews, territory, and languages that persist in the urban context of Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, is foreseen. This matrix needs to result from the consensus of all community members. Much work still needs to be done, but we have taken the first step.

Referências

ARIAS MONGE, Mónica. Conversation Circles as a Teaching Strategy: An Experience to Reflect on and Implement in Higher Education. Revista Electrónica Educare, San José de Costa Rica, v. 16, n. 2, p. 9-24, 2012. [ Links ]

ARTUNDUAGA, Luis Alberto. La etnoeducación: una dimensión de trabajo para la educación en comunidades indígenas de Colombia. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, Madrid, n. 13, p. 35-45, 1997. [ Links ]

BANKS, James Albert. An introduction to multicultural education. Fifth ed. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc., 2014. [ Links ]

BANKS, James Albert. Approaches to Multicultural Curriculum Reform. Trotter Review, Boston, v. 3, n. 3, p. 17–19, 1989. Disponível em: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_review/vol3/iss3/5. Acesso em: 30 ago. 2023. [ Links ]

BERNSTEIN, Basil. On Pedagogic Discourse. Em: RICHARDSON, John (org.). Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. New York: Greenwood Press, 1986. [ Links ]

BHASKAR, Roy. A realist theory of science. First ed. New York: Routledge, 2008. [ Links ]

BHASKAR, Roy. The possibility of naturalism. A philosophical critique of contemporary human science. Third ed. New York: Routledge, 1998. [ Links ]

BONFIL, Guillermo. El etnodesarrollo: sus premisas jurídicas, políticas y de organización. Em: EDICIONES FLACSO; ROJAS ARAVENA, José (org.). América Latina: Etnodesarrollo y etnocidio. Primera ed. San José de Costa Rica: EUNED, 1982. [ Links ]

CABARCAS BELLO, Bleidys. “El Kuagro, un zambapalo en el aula”. Una propuesta pedagógica intercultural. Revista Adelante Ahead, Cartagena, v. 8, n. 1, p. 13-22, 2017. Disponível em: http://ojs.unicolombo.edu.co/index.php/adelante-ahead/article/view/128. Acesso em: 30 ago. 2023. [ Links ]

CARREÑO BOLIVAR, Laura Lucia. Promoting meaningful encounters as a way to enhance intercultural competences. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, Bogotá, v. 20, n. 1, p. 120-135, 2018. [ Links ]

CASTILLO GUZMÁN, Elizabeth; CAICEDO ORTIZ, José Antonio. La educación intercultural bilingüe. El caso colombiano. Primera ed. Buenos Aires: Fundación Laboratorio de Políticas Públicas – FLAPE, 2008. [ Links ]

COLOMBIA. [Constituição (1991)]. Constitución Política de la República de Colombia 1991. Bogotá: Función Pública Gov.co, 1991. [ Links ]

COLOMBIA. Ley general de educación. Ley 115 febrero 8 de 1994: Colombia, n. 115, 8 fev. 1994. [ Links ]

COOK, Guy. Discourse. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1990. [ Links ]

COULON, Alain. Etnometodología y educación. Primera Editora Barcelona: Ediciones Paidós Ibérica S.A., 1995. (v. 118). [ Links ]

CRESWELL, John Ward. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 3. ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc, 2009. [ Links ]

DE ÁVILA TORRES, Dimas. San Basilio de Palenque y su organización social: El kuagro como referente histórico cultural. Hexágono Pedagógico, Cartagena, v. 8, n. 1, p. 155-163, 2017. [ Links ]

DE ÁVILA TORRES, Dimas del Rosario; SIMARRA OBESO, Rutsely. Ma-Kuagro: Elemento de la cultura palenquera y su incidencia en las prácticas pedagógicas en la escuela San Basilio Palenque, Colombia. Ciencia e Interculturalidad, Managua, v. 11, n. 2, p. 88-99, 2012. [ Links ]

DE TEZANOS, Araceli. Una etnografía de la etnografía. Aproximaciones metodológicas para la enseñanza del enfoque cualitativo interpretativo para la investigación social. Primera ed. Bogotá: Editorial Antropos, 1998. [ Links ]

DIETZ, Gunther. Hacia una etnografía doblemente reflexiva: una propuesta desde la antropología de la interculturalidad. Asociación de Antropólogos Iberoamericanos en Red-AIBR, Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana, v. 6, n. 1, p. 3-26, 2011. Disponível em: https://www.rAedalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=62321332002. Acesso em: 30 ago. 2023. [ Links ]

DIETZ, Gunther; MATEOS CORTÉS, Laura Selene. Interculturalidad y educación intercultural en México. Un análisis de los discursos nacionales e internacionales en su impacto en los modelos educativos mexicanos. Primera ed. México: Secretaría de Educación Pública, CGEIB, 2011. E-book. Disponível em: http://eib.sep.gob.mx. Acesso em: 30 ago. 2023. [ Links ]

DIETZ, Gunther; MATEOS CORTÉS, Laura Selene; JIMÉNEZ NARANJO, Yolanda; MENDOZA ZUARRY, Rosa Guadalupe. Los estudios interculturales ante la diversidad cultural. Una propuesta conceptual. Revista Decisio, Michoacán, p. 26-29, 2009. Disponível em: http://www.uv.mx/uvi/cuerpo/introduccion.html. Acesso em: 30 ago. 2023. [ Links ]

ELLIOTT, John. La investigación-acción en educación. Cuarta ed. Madrid: Morata, 2000. [ Links ]

FALS BORDA, Orlando. Capítulo 4. Por la Praxis: el problema de cómo investigar la realidad para transformarla. In: ORDÓÑEZ, Edward Javier; GRANJA ESCOBAR, Luis Carlos; LUNA NIETO, Alexander (org.). Antología del pensamiento social en Colombia. 26. ed. Cali: Universidad Santiago de Cali, 2018. [ Links ]

FALS BORDA, Orlando. El problema de como investigar la realidad para transformarla por la praxis. 7. ed. Bogotá: Tercer Mundo Editores S.A., 1994. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogía del oprimido. 2. ed. Tradução Jorge Mellado. México: Siglo XXI Editores, S.A., de C.V., 2005. [ Links ]

GARCÍA LEÓN, Javier; GARCÍA LEÓN, David. Políticas Lingüísticas en Colombia: tensiones entre políticas para lenguas mayoritarias y lenguas minoritarias. Boletín de Filología, Santiago, v. 47, n. 2, p. 47-70, 2012. [ Links ]

GARCÍA RINCÓN, Jorge Enrique. Pensamiento Educativo Afrocolombiano. De los intelectuales a las experiencias del movimiento social y pedagógico. Revista Colombiana de Educación, Bogotá, n. 69, p. 159-182, 2015. [ Links ]

GIROUX, Henry. La Pedagogía crítica en tiempos oscuros. Praxis Educativa, La Pampa, v. XVII, n. 1 y 2, p. 13-26, 2013. Disponível em: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=153129924002. Acesso em: 30 ago. 2023. [ Links ]

GOBERNACIÓN DE ANTIOQUIA. Etnoeducación. Texto para maestras y maestros. Grados: 3°, 4° y 5°. Primera ed. Medellín, Milenio Editores e Impresores E.U., 2015. [ Links ]

GÓMEZ-ZERMEÑO, Marcela Georgina. Strategies to identify intercultural competences in community instructors. Journal for Multicultural Education, Leeds, v. 12, n. 4, p. 330-342, 2018. [ Links ]

GRIMSON, Alejandro. Diversidad y Cultura. Reificación y situacionalidad. Tabula Rasa, Bogotá, n. 8, p. 45-67, 2008. [ Links ]

HALL, Stuart. Sin garantías: Trayectorias y problemáticas en estudios culturales. Restrepo, Eduardo; Walsh, Catherine; Vich, Víctor (org.). Quito, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, 2014. [ Links ]

HAMMER, Mitchell; BENNETT, Milton James; WISEMAN, Richard. Measuring intercultural sensitivity: The intercultural development inventory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Texas, v. 27, n. 4, p. 421-443, 2003. [ Links ]

INSTITUCIÓN EDUCATIVA MERCEDES ÁBREGO. Manual de convivencia. Resolución nº 025, del 4 de noviembre 2014. Cartagena, 2014. [ Links ]

JOHNSON, Burke; CHRISTENSEN, Larry. Educational research: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. Third ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2008. [ Links ]

MARTÍNEZ MIGUÉLEZ, Miguel. La investigación-acción en el aula. Agenda Académica, v. 7, n. 1, p. 27-39, 2000. [ Links ]

MENA GARCÍA, María Isabel. Panorama Afrodescendiente. Las Paradojas Etnoeducativas. In: LÓPEZ, Néstor; D’ALESSANDRE, Vanessa; CORBETTA, Silvina (org.). La educación de los pueblos indígenas y afrodescendientes: informe sobre tendencias sociales y educativas en América Latina 48. Buenos Aires: IIPE-UNESCO, Sede Regional Buenos Aires, 2011. [ Links ]

MERTLER, Craig. Action research: teachers as researchers in the classroom. Second ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2009. [ Links ]

MONTES PÉREZ, Surjey del Carmen. Currículo para la diversidad cultural colombiana. 2022. Propuesta de tesis doctoral sustentada y aprobada. Universidad del Norte, Barranquilla, 2022. [ Links ]

OROZCO-LÓPEZ, Efrén. ¿Autonomía educativa o interculturalidad? La educación alternativa entre los pueblos originarios de Chiapas, México. Revista Colombiana de Educación, Bogotá, n. 74, p. 37-61, 2018. [ Links ]

ORTIZ FONSECA, Jenny Paola; RODRÍGUEZ GAITÁN, Luisa Fernanda; PERNETH PAREJA, Leidy Laura. Caminos Interculturales en la Región Caribe III. Narrativas y oralidades recuperando saberes ancestrales. Bogotá: Gente Nueva, 2018. E-book. Disponível em: http://www.cinep.org.co. Acesso em: 30 ago. 2023. [ Links ]

PARDO, Mauricio. Entre la autonomía y la institucionalización: Dilemas del movimiento negro colombiano. Journal of Latin American Anthropology, Arlington, v. 7, n. 2, p. 60-84, 2002. [ Links ]

PARRA, Juan David. El arte del muestreo cualitativo y su importancia para la evaluación y la investigación de políticas públicas: una aproximación realista. Revista Ópera, Bogotá, n. 25, p. 119-136, 2019. [ Links ]

PARRA, Juan David. Introducción a la evaluación realista y sus métodos: ¿qué funciona, para quién, en qué aspectos, hasta qué punto, en qué contexto y cómo? Revista Economía & Región, Cartagena, v. 11, n. 2, p. 11-44, 2017. [ Links ]

PAWSON, Ray; TILLEY, Nick. Realistic evaluation. London: SAGE, 1997. [ Links ]

PERNETH PAREJA, Leidy Laura; ORTIZ FONSECA, Jenny Paola; GARCIA BECERRA, Andrea. De encuentros y desencuentros. Reflexiones sobre la educación intercultural desde una experiencia en el Caribe colombiano. Primera ed. Bogotá: Imageprinting, 2019. Disponível em: http://www.cinep.org.co. Acesso em: 30 ago. 2023. E-book. [ Links ]

REAL ACADEMIA ESPAÑOLA. Diccionario de la lengua española. 22. ed. Bogotá: Quebecor World Bogotá S.A., 2001. (v. II, g/z). [ Links ]

RICARDO BARRETO, Carmen Tulia. Formación y desarrollo de la competencia intercultural en ambientes virtuales de aprendizaje. 2013. Tesis Doctoral - Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Madrid, 2013. [ Links ]

RICARDO BARRETO, Carmen; LLINÁS SOLANO, Humberto; HERNÁNDEZ BELEÑO, Sergio. Competencias interculturales de profesores virtuales en universidades de la Costa Caribe Colombiana. Revista Opción, Zulia, v. 33, n. 82, p. 263-279, 2017. [ Links ]

ROJAS, Axel. Gobernar(se) en nombre de la cultura. Interculturalidad y educación para grupos étnicos en Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Antropología, Bogotá, v. 47, n. 2, p. 173-198, 2011. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Boaventura de Souza. Epistemologías del sur. Epistemologies of the south. Utopía y praxis latinoamericana, Revista Internacional de Filosofía Iberoamericana y Teoría Social, Zulia. v. 16, n. 54, p. 17-39, 2011. [ Links ]

TILLEY, Nick; PAWSON, Ray. Realistic evaluation. Thousand Oaks, C. A. US.: SAGE Publications, Limited, 2014. [ Links ]

ORGANIZACIÓN DE LAS NACIONES UNIDAS PARA LA CULTURA, LAS CIENCIAS Y LA EDUCACIÓN – UNESCO. 25. Declaración Universal de la UNESCO sobre la Diversidad Cultural. In: 2002, París, Francia. Actas de la Conferencia General, 31a reunión, París, 15 de octubre-3 de noviembre de 2001, v. 1: Resoluciones. París, 2002. p. 66-70. Disponível em: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000124687_spa.page=72. Acesso em: 9 set. 2023. [ Links ]

ORGANIZACIÓN DE LAS NACIONES UNIDAS PARA LA CULTURA, LAS CIENCIAS Y LA EDUCACIÓN – UNESCO. Conferencia Mundial sobre las Políticas Culturales. In: 1982, París. Informe Final, México, D.F., 26 julio-6 de agosto de 1982. Paris: UNESCO, 1982. [ Links ]

VAN LEEUWEN, Theo. Discourse and practice. New tools for critical discourse analysis. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 2008. [ Links ]

WALSH, Catherine. Interculturalidad, colonialidad y educación. Revista Educación y Pedagogía, Medellín, v. 19, n. 48, p. 25-35, 2007. [ Links ]

WALSH, Catherine. La interculturalidad en la educación. Lima: Ministerio de Educación - Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia UNICEF, 2005. [ Links ]

WOODS, Peter. La escuela por dentro. La etnografía en la investigación educativa. Primera ed. Tradução Marcos Aurelio Galmarini. Barcelona: PAIDÓS/MEC, 1987. [ Links ]

Received: October 22, 2023; Accepted: November 17, 2023

texto em

texto em