Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica

versão impressa ISSN 0100-5502versão On-line ISSN 1981-5271

Rev. Bras. Educ. Med. vol.48 no.1 Rio de Janeiro 2024 Epub 06-Mar-2024

https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-5271v48.1-2023-0048

REVIEW ARTICLE

Scoping review of the application of the Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM) in medical residency

1 Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, Espírito Santo, Brasil.

2 Hospital Estadual Central Dr Benicio Tavares Pereira, Vitória, Espírito Santo, Brasil.

3 UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA JÚLIO DE MESQUITA FILHO, BOTUCATU, SÃO PAULO, BRASIL.

Introduction:

The PHEEM (postgraduate hospital educational environment measure) is a validated and reliable instrument to assess the educational environment in medical residency programs.

Objective:

To map the application of the PHEEM questionnaire in medical residency, evaluate the results found, positive and negative aspects and points for improvement.

Method:

We performed a scoping review according to the Joanna Briggs institution’s methodology. Studies that followed the PCC structure were included, as follows: P (participants) = resident physicians of any specialty; C (concept) = The PHEEM is an instrument used to assess the educational environment in medical residency, through a 40-item questionnaire divided into 3 subscales that include perception of autonomy, teaching and social support. C (context)= studies on PHEEM in medical residency of any specialty. PubMed, EMBASE and the Virtual Health Library databases were the data sources.

Results:

We identified 1588 references, and after reading the title and abstract, 50 references were selected for full reading, and 36 studies were included. The studies were carried out in 22 countries, and most revealed a more positive than negative educational environment, albeit with room for improvement. In the subscales, the perception of autonomy was more positive than negative, and the perception of teaching revealed that most programs are moving in the right direction. However, when evaluating social support, the results were divided between an unpleasant environment and an environment with more pros than cons. The main highlighted positive points were low racial and sexual discrimination, possibility of working in a team, adequate level of responsibilities, accessible teachers with good teaching skills, learning opportunities and participation in educational events. The main negative points were lack of adequate food and accommodation during the shifts, excessive workload, lack of feedback from preceptors and lack of protected time for study and the culture of blaming the resident.

Conclusion:

The application of PHEEM revealed that in most medical residency programs the educational environment was more positive than negative, albeit with room for improvement. Efforts are needed to improve the educational environment, especially social support, in medical residency programs.

Key words: Internship and Residency; Environment; Education; PHEEM

Introdução:

O Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM) é um instrumento validado e confiável para avaliar o ambiente educacional nos programas de residência médica.

Objetivo:

Este estudo teve como objetivos mapear a aplicação do questionário PHEEM na residência médica e avaliar os resultados, os aspectos positivos e negativos e os pontos passíveis de melhoria.

Método:

Trata-se de uma revisão de escopo de acordo com a metodologia do Instituto Joanna Briggs de revisões de escopo. Foram incluídos estudos seguindo a estrutura PCC: P (participantes) = médicos residentes de qualquer especialidade; C (conceito) = o PHEEM é um instrumento utilizado para avaliar o ambiente educacional na residência médica, por meio de um questionário de 40 itens divididos em três subescalas que incluem percepção de autonomia, ensino e suporte social; C (cenário) = pesquisas sobre o PHEEM na residência médica de qualquer especialidade. As bases eletrônicas pesquisadas foram: PubMed, Embase e Biblioteca Virtual em Saúde (BVS).

Resultado:

As estratégias de busca rodadas resultaram em 1.588 estudos, 50 foram lidos na íntegra, e incluíram-se 36. Os estudos foram realizados em 22 países, e a maioria revelou um ambiente educacional mais positivo que negativo, entretanto com espaço para melhorias. Nas subescalas, a percepção de autonomia se mostrou mais positiva que negativa, e a percepção de ensino revelou que a maioria dos programas está caminhando na direção certa. Entretanto, na avaliação do suporte social, os resultados foram divididos entre um ambiente não agradável e um ambiente com mais prós do que contras. Os principais pontos positivos destacados foram baixa discriminação racial e sexual, possibilidade de trabalhar em equipe, nível adequado de responsabilidades, professores acessíveis e com boas habilidades de ensino, oportunidades de aprendizado e participação em eventos educacionais. Os principais pontos negativos foram falta de alimentação e acomodação adequadas durante o plantão, carga horária excessiva, falta de feedback por parte dos preceptores, falta de tempo protegido para estudo e cultura de culpar o residente.

Conclusão:

A aplicação do PHEEM revelou que, na maioria dos programas de residência médica, o ambiente educacional se mostrou mais positivo que negativo, entretanto com espaço para melhorias. São necessários esforços para a melhoria do ambiente educacional, especialmente do suporte social, nos programas de residência médica.

Palavras-chave: Residência Médica; Ambiente; Educação; PHEEM

INTRODUCTION

Medical residency is a type of postgraduate education aimed at physicians, in the form of specialization courses, which takes place in health institutions under the guidance of qualified medical professionals and is considered the gold standard of medical specialization1.

The educational environment is a complex and dynamic structure with multiple interactions involving the student, teachers, the medical curriculum and the course structure. The educational environment is an important determinant of student and teacher behavior and this environment influences the residents’ results, satisfaction and learning success2),(3.

The Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM) is a validated and reliable instrument for evaluating the educational environment during training in medical residency courses4. It was developed by Roff et al.5 as a 40-item questionnaire divided into three subscales that include perception of autonomy, perception of teaching and perception of social support. Each item is answered and scored according to a Likert scale with five options: Completely agree (4 points), Agree (3 points), Neutral (2 points), Disagree (1 point), Completely disagree (0 point). However, four of the 40 items (numbers 7, 8, 11 and 13) are negative sentences and must be scored in reverse. The result of its application allows evaluating the educational environment of medical residency programs, pointing out the positive points and areas that need to be improved6. The maximum score on the scale is 160 points, with the maximum score for the perception of autonomy subscale being 56, the perception of teaching 60 and the perception of social support 44 points. Scores between 0-40 can be interpreted as very bad, 41-80 as having many problems, 81-120 as a more positive than negative environment, but with room for improvement, and 121-160 are considered excellent training environments5.

PHEEM is widely adopted in different postgraduate teaching environments internationally4),(6. The PHEEM questionnaire was translated and validated into Portuguese by Vieira7 and, therefore, can be used as a method to evaluate medical residencies in Brazil. Furthermore, longitudinal monitoring of PHEEM after changes in the medical residency environment can be used to demonstrate improvements in the educational environment4),(8.

There is no structured and regular assessment of the educational environment In the vast majority of Medical Residency Programs in Brazil. Thus, knowledge and application of the PHEEM questionnaire in medical residency programs can contribute to diagnosing the situation in each program, developing strategies to improve the educational environment and its sporadic application can evaluate the impact of these changes. Therefore, this study aimed at mapping the application of the PHEEM questionnaire in medical residency programs, reporting the results found, positive and negative aspects and points that need improvement highlighted by the interviewed residents.

METHOD

A scoping review was carried out in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews8. The results were reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA- Scoping Review)9),(10.

This review used the acronym PCC, being: P for “participants”; C for “concept”, and C for “context”.

Concept

The PHEEM is an instrument used to evaluate the educational environment during training in medical residency courses4, through a 40-item questionnaire divided into three subscales that include perception of autonomy, perception of teaching and perception of social support5.

Context

This review considered studies on PHEEM in medical residency in any specialty, in any study setting, including community services and clinical settings (hospital wards, outpatient clinics, emergency room, operating room, etc.), as well as primary care services.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that had undergraduate students as participants were excluded, as well as those that had residents from other areas of health, but not physicians, as participants.

Search strategies

Three search strategies were created adapted to the electronic databases PubMed, Embase and Virtual Health Library (VHL). The descriptors and synonyms related to the terms ‘medical residency’, ‘PHEEM’ and ‘educational environment’ were used. On 08/25/2022 the search strategy was carried out in the PubMed database, and on 08/26/2023 the strategies were carried out in the Embase and BVS databases, in addition to updating the PubMed database. There were no language or publication date restrictions.

Study selection

After the search strategies were carried out, all identified references were transported to RAYYAN, a web application for carrying out systematic reviews. The titles and abstracts were then analyzed by two independent reviewers (P.L.G and A.P.M.M.) to evaluate them according to the inclusion criteria. The full texts of the selected studies were independently assessed in details according to the inclusion criteria by the authors. Reasons for exclusion of full-text studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were recorded and reported in the review. Disagreements that arose between reviewers at each stage of the study selection process were resolved through discussion, or with a third reviewer.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from the included studies: country of origin, type of study, residents’ specialty, context, assessed outcomes, number of participants, total PHEEM score, autonomy, teaching and social support subscores, more positive points, more negative points, other relevant information and results.

RESULTS

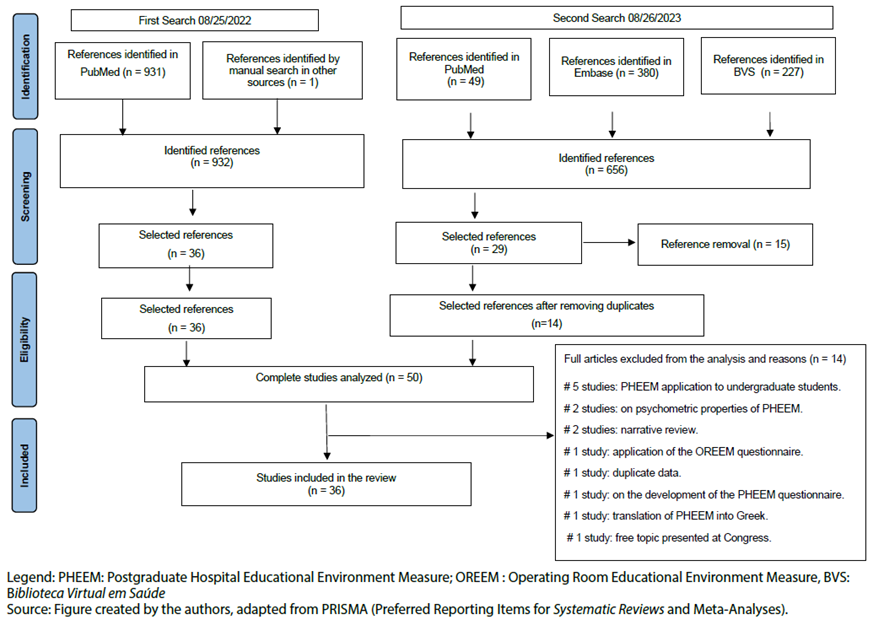

The first search strategy resulted in 931 studies and one study was acquired by manual search6. The second search strategy resulted in 656 studies. After reading the titles and abstracts, 50 studies were identified as eligible and were read in full, but 14 studies were excluded4),(5),(11)-(22 (Figure 1). The excluded studies and the reasons for exclusion are shown in Table 1. Therefore, 36 studies were included in this review (6)-(8),(23)-(55.

Table 1 Excluded studies and reasons for exclusion.

| Study | Year | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Algaidi 11 | 2010 | PHEEM applied to undergraduate students |

| Boor et al.12 | 2007 | Evaluated only psychometric properties |

| Chan et al.4 | 2016 | Review that evaluated PHEEM in several medical educational settings |

| Beer et al.13) | 2021 | PHEEM applied to undergraduate students |

| Gooneratne et al.14 | 2008 | PHEEM applied to undergraduate students |

| Kanashiro et al.15 | 2006 | Evaluated educational environment in the operating room with OREEM |

| Mohamed Cassim16 | 2018 | Free Topic in Congress |

| Naidoo et al. 17 | 2017 | PHEEM applied to undergraduate students |

| Ong et al.18 | 2020 | Duplicate data (from Ong 2019) |

| Rammos et al.19 | 2011 | Translation of PHEEM into Greek |

| Riquelme et al.20 | 2009 | PHEEM applied to undergraduate students |

| Roff et al.5 | 2005 | Creation of the PHEEM questionnaire |

| Shokoohi et al.21 | 2014 | Evaluated only psychometric properties |

| Wall et al.22 | 2009 | Review Article |

Source: prepared by the authors.

Legend: PHEEM: Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure; OREEM (Operating Room Educational Environment Measure): measure of the educational environment in a surgical center.

Included studies

Table 2 summarizes the main characteristics of the studies included in this review.

Table 2 Summary of the characteristics of the included studies.

| Author, year | Country | Study design | Participants | Concept | Context | Assessed outcomes | Number | Average PHEEM Total Score (SD) | Subscores (SD) Autonomy (A), Teaching (T) and Social (S) | Positive points | Negative points | Other information and results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aalam et et al, 2018 23 | USA and Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | Emergency medicine residents. | Adapted PHEEM | 3 emergency medicine programs in Saudi Arabia and 3 emergency medicine programs in the USA. | Compare the educational environment between the USA and Saudi Arabian programs. | 219 | USA: 118.7 SA: 109.9 | A: 41.8(USA)X 38.1 (SA) | USA: feeling like part of the team, clear training instructions, protected study time SA: protected time for study, good collaboration with other doctors, feeling part of the team. | USA: food during shifts, accommodation during shifts, opportunity to continue monitoring the patient. SA: food during shifts, opportunity to continue monitoring the patient, culture of blaming the resident. | US programs score higher overall. Mean scores differ on the autonomy and teaching scales, but not on the social support scale. US programs have more resources like simulation rooms and access to conferences and lectures. |

| T: 46.5(USA) X 43.1 (SA) | ||||||||||||

| S: 30.5(USA) X 28.6 (SA) | ||||||||||||

| Ahmad et al , 202124 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | Residents of several specialties | Adapted PHEEM | 4 tertiary hospitals in Pakistan: 3 public and 1 private | To assess the educational environment in medical residency teaching hospitals in Pakistan. | 195 | Public Hospitals: 72.6(17.6) | A:23.6 (16.2) | Feeling safe in the work environment, good collaboration with the work team. | Sexual discrimination, culture of blaming the resident, lack of time to study. | In private hospitals, the educational environment was considered worse than in public hospitals. It is necessary to improve the educational environment and, especially, eradicate sexual discrimination. |

| Private Hospitals: 61.31(25.03) | T: 24.1(16.9) | |||||||||||

| S:19.3(13.2) | ||||||||||||

| Akdeniz et al , 201525 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | Family Medicine Residents | PHEEM, MBI | Department of Family Medicine of Universities: 21 Hospitals of the Ministry of Health: 11 | To evaluate the educational environment and burnout in Family Medicine programs. | 174 | 66.0(30.5) | A:26.4(9.4) | Not reported. | Not reported. | Perception of autonomy, teaching and social support below average, indicating a need for improvement. Levels of personal satisfaction, depersonalization and emotional exhaustion were within the range considered normal. |

| T:25.7(10.9) | ||||||||||||

| S:18.7(7.6) | ||||||||||||

| Aspergren et al, 200726 | Denmark | Cross-sectional | Residents of several specialties (internal medicine, neurology, oncology, pediatrics, surgery, orthopedics, gynecology and obstetrics, and radiology). | Adapted PHEEM | Residents from several departments and specialties. | Translate into Danish and validate PHEEM in the country. A reduced version of PHEEM was used. | 342 (159 seniors and 183 juniors) | Not reported. | Not reported. Evaluated the average for each PHEEM item. | Information about the program, appropriate level of responsibilities, feeling part of the work team. | Being called at inappropriate times, lack of information about working hours, food during shifts. | The questionnaire has been validated for use in Denmark. |

| Bari et al, 201827 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | Residents in pediatrics, pediatric surgery and pediatric diagnosis | PHEEM | Lahore Children’s Hospital, Pakistan | To evaluate the residents’ perception of the educational environment and compare perceptions between different specialties and years of residency. | 160 | 88.16 (14.18) | A:29.27 (7.09) | Adequate level of responsibility, good opportunities to perform hands-on procedures and good collaboration with other doctors. | Food during shifts, inadequate working hours, lack of a working hours contract, lack of an informative manual for residents. | There was no significant difference between specialties and different years of residency. The social support subscale showed a more negative perception as an unpleasant environment. |

| T: 34.35 (9.66) | ||||||||||||

| S:21.58 (6.59) | ||||||||||||

| Berrani et al, 2020 28 | Morocco | Cross-sectional | Residents of different specialties: internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, anesthesiology, intensive care, gynecology and obstetrics and laboratory medicine | Adapted PHEEM | Six hospitals in Rabat (capital of Morocco) | To evaluate the educational environment of residents in Morocco and compare the perceptions of residents of different specialties. | 255 | 81.4 (21.8) | A:31.9 (8.3) | Preceptors with good teaching skills, accessible preceptors, faculty encourage resident autonomy. | Accommodation during shifts, food during shifts, not feeling safe in the hospital, sexual discrimination (reported by half of residents) and racial discrimination, culture of blame. | Valid and reliable instrument. Residents in laboratory medicine had higher PHEEM values than those in other specialties, especially those in surgery and gynecology and obstetrics. The main problems are poor infrastructure, inadequate quality of supervision and teaching, and inadequate work regulations. |

| T:33.2 (10.1) | ||||||||||||

| S:18.2 (21.8) | ||||||||||||

| Bigotte Vieira et al, 2016 29 | Portugal | Cross-sectional | Resident doctors of various specialties | Modified PHEEM | Medical residency for all specialties and regions of Portugal | To evaluate the doctors’ satisfaction with residency according to specialty and region of the country. | 3456 | 91.7(24.2) | Not reported | Absence of sexual and racial discrimination, good collaboration with other doctors, opportunity to participate in educational events. | Lack of protected time for study, lack of counseling opportunities for failure situations, lack of adequate accommodation during shifts, little career advice. | Modified PHEEM including questions about satisfaction with coordination and advisor. Endocrinology, Cardiology, Anesthesiology, Family Medicine and Gastroenterology were the specialties with the greatest satisfaction. Greater satisfaction among residents of Azores and Madeira. |

| Binsaleh et al, 201530 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | Urology residents | PHEEM | Urology residents, different training levels, in several regions of Saudi Arabia and in different sectors of the healthcare system. Only 1 woman. | To investigate associations with level of training, regions of Saudi Arabia, and healthcare system sectors. | 38 | 77.7 (16.5) | A: 26.18 (6.5) | Absence of racism, feeling part of the team, opportunity to participate in educational events, accessible teachers. | Food during shifts, lack of clinical protocols and information manuals for residents, lack of contract regarding working hours. | Less than satisfactory educational environment. Differences between different healthcare sectors. Perception did not vary between training level and regions of the country. Need to improve: clinical protocols, working hours, quality of supervision, infrastructure in the hospital environment. |

| T:29.7 (7.7) | ||||||||||||

| S: 21.9 (4.3) | ||||||||||||

| BuAli et al, 2015 31 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | Residents in Pediatrics | PHEEM | Six teaching hospitals in the eastern region of Saudi Arabia | To evaluate the educational environment of the pediatric residency in 6 hospitals. | 104 (37 women , 67 men) | 100.19 (23.13) | A: 34,91(7,83) | Collaboration with other residents, feeling part of the team, possibility of participating in educational events, opportunity to perform practical procedures. | Racism, sexual discrimination, working hours, food during shifts, culture of blame, having to perform inappropriate tasks and being called at inappropriate times. | There was no significant difference between genders and year of training. Differences were observed between hospitals. Improvement in social support is required, especially regarding issues of racial and sexual discrimination. |

| Women: 105.39 (22.16) | E: 38,89(9,8) | |||||||||||

| Men: 97.23 (23.48) | S:26,38(7,04) | |||||||||||

| Women: A: 38.5 (7.98) | ||||||||||||

| T: 38.88 (8.14) | ||||||||||||

| S: 28 (7.69) | ||||||||||||

| Men: A:35.86 (7.75) | ||||||||||||

| T: 35.98 (10.75) | ||||||||||||

| S:25.38 (6.56) | ||||||||||||

| Chew et al, 20228 | Singapore | Longitudinal | Psychiatry residents | PHEEM , OLBI | Singapore National Psychiatry Program | To evaluate the relationship between burnout and the educational environment among psychiatry residents each year for five years. | 93 | Initial : 112.3(16.2) | Initial : A:39.2(5.8) | Not reported | Not reported | Perception of the baseline educational environment was inversely proportional to the burnout status. The PHEEM teaching subdomain score increased significantly over time for all residents regardless of the burnout status. |

| After 5 years: 120.3(14.0) | T:43.3(6.4) | |||||||||||

| S:29.6(5.1) | ||||||||||||

| After 5 years: A:42.0 (5.4) | ||||||||||||

| T:47.0(4.8) | ||||||||||||

| S:31.4(4.6) | ||||||||||||

| Clapham et al, 2007 32 | Egland nd Scotland | Cross-sectional | Intensive care residents | PHEEM | Nine intensive care training centers in hospitals in England and Scotland. | To demonstrate the quality of the residents’ work environment. | 134 | 103.5 (19.1) | A: 35.7 (7.03) | Absence of racism or sexism, good supervision, collaboration with other residents, adequate level of responsibility, feeling like part of the team. | Food and accommodation during shifts, lack of information manual for residents, lack of opportunity for counseling for residents who failed. | There was a significant difference between training level and between centers. No racism or sexual discrimination was reported. Residents satisfied with teaching, work and social support. |

| T:38.8 (9.46) | ||||||||||||

| S: 28.43 (5.20) | ||||||||||||

| Ezomike et al, 2020 33 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | Residents of internal medicine, gynecology, pediatrics and surgery. | PHEEM | Nigeria University Hospital. | To evaluate the educational environment and determine if there are differences in subgroups of residents. | 160 | 85.82 (1.02) | A:29.27 (1.05) | Collaboration from other residents, absence of sexual discrimination, opportunity to participate in educational events, appropriate level of responsibility. | Food during shifts, accommodation during shifts, lack of counseling opportunities for residents who failed, excessive working hours | The perception of social support is that the environment is not pleasant. Men scored higher than women and gynecology and obstetrics residents scored higher than those from other specialties in the total PHEEM score and in the teaching and social support categories. There was a difference between training levels in the total score and autonomy subscore. |

| T:34.80 (0.98) | ||||||||||||

| S: 21.55 (1.03) | ||||||||||||

| Fisseha et al, 2021 34 | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | Internal medicine residents | PHEEM | University Hospital in Ethiopia. | To evaluate the educational environment in an internal medicine residency program in Ethiopia. | 100 (80 men) | 70.87 (19.8) | A:25.9 (7.1) | Collaboration from other residents, absence of racism and sexual discrimination, feeling physically safe in the hospital environment. | Food and accommodation during shifts, lack of manual and clinical protocols for residents, lack of feedback from teachers, lack of supervision at all times, excessive workload. | The total PHEEM score indicates many problems and the need for changes. Main problems to be improved: excessive workload, inadequate teaching, inadequate physical hospital environment and lack of diagnostic and therapeutic resources. The score was higher for men than for women. |

| T:27.1 (10.2) | ||||||||||||

| S:17.9 (5.1) | ||||||||||||

| Flaherty et al, 2016 35 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | Residents of various specialties | PHEEM | University Hospitals in Galway, Ireland | To assess the educational environment among residents of different training levels in Ireland. | 61 | 82.88 (18.99) | A: 27.83 | Absence of sexual and racial discrimination, feeling part of the team, collaboration with other residents, feeling physically safe in the hospital. | Excessive workload, calls at inappropriate times, poor food and accommodation during shifts, lack of protected time for study, lack of feedback from preceptors, culture of blaming the resident. | Deficiencies were identified in several aspects of the educational environment including the need to improve protected study time, feedback, and learning opportunities for doctors in the initial years of training. |

| T: 31.19 | ||||||||||||

| S: 23.75 | ||||||||||||

| Galli et al, 201436 | Argentina | Cross-sectional | Residents of Cardiology | PHEEM | 31 hospitals (public and private) in the Buenos Aires region | To evaluate the educational environment in Cardiology residency and compare public and private hospitals. | 148 | Not reported. | Not reported. | Feeling part of the team, opportunity to work as a team, absence of sexual and racial discrimination. | Lack of protected time for study, lack of a manual with instructions about the program, lack of clear rules. | More positive than negative educational environment, but with room for improvement. Private hospitals showed better teaching conditions. |

| González et al, 2022 37 | Chile | Cross-sectional | Residents from 64 specialties | PHEEM | 15 universities in Chile | To evaluate the educational environment of residency programs in different specialties. | 1259 | 100.5 | A:36.0 | Not described. | Lack of protected time for study, culture of blaming the resident and lack of a routine manual. | The specialties with the highest PHEEM scores were: Ophthalmology (116), Dermatology (113.5) and Anatomopathology (113) and those with the lowest scores were General Surgery (82) and Gynecology, Obstetrics (88.5) and Cardiology (92). |

| T:38.0 | ||||||||||||

| S26.0 | ||||||||||||

| Goughet al, 201038 | Australia | Cross-sectional | R1, R2, and R3 Residents | PHEEM | 9 hospitals | To test PHEEM acceptability. | 429 | 110 | Not reported. | Available teachers, safe environment and teamwork. | Food during shifts, lack of feedback, little career guidance. | 8 hospitals: more positive than negative environment, and 1 hospital: excellent environment. |

| Goul-ding et al, 201639 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | Dermatology Residents | Modified PHEEM | Hospitals located in one region of the United Kingdom (West Midlands) | To evaluate the educational environment in the Dermatology residency. | 19 | 96.5 / maximum score of 152 | A: 35.8/56 | Possibility of participating in educational events, safety in the workplace, teachers with good teaching skills | Accommodation and food during shifts, lack of feedback from teachers, few opportunities for counseling in case of poor performance. | Questions about sexual and racial discrimination were excluded. |

| T:39.4/60 | ||||||||||||

| S:21.3/36 | ||||||||||||

| Herrera et al.2012 6 | Chile | Cross-sectional | Residents from several specialties (35 programs) | PHEEM | Several clinical, surgical and pediatric specialties. | To compare scores by gender, university, nationality. | 318 | 105.09 (22.46) | A: 36.54 (8.26) | Low discrimination, good preceptors, safe environment. | Lack of time to study, little academic advice, lack of information about working hours. | There was no difference between gender and university of origin. Foreigners rated the educational environment better than Chileans. |

| T:39.76 (10.11) | ||||||||||||

| S:28.79 (5.98) | ||||||||||||

| Jalili et al, 2014 40 | Iran | Cross-sectional | Emergency medicine residents | PHEEM | Three emergency medicine programs | Applicability of the Persian version of the questionnaire. | 89 | Did not evaluate the total average | Evaluated average per item. Average score per item 2.24 (0.06) | Working hours contract, accessible teachers, teamwork. | Lack of information manual, accommodation during shifts, career guidance. | Persian version with 37 questions and not 40. Reliable method for emergency medicine programs. No differences between genders and training levels. |

| A: 2.4(0.58) | ||||||||||||

| T: 2.57(0.35) | ||||||||||||

| S:2.21 (0.67) | ||||||||||||

| Karatanos et al, 201541 | Greece | Cross-sectional | Residents of several specialties. | Modified PHEEM | Western Greece Hospitals | To evaluate the educational environment in hospitals in different specialties. | 731 | Not described. | Not described. | Teamwork, accessible teachers, encouragement to learn alone | Racism and sexual discrimination, lack of feedback, lack of information manual, lack of support for residents with poor performance. | Modified PHEEM with the inclusion of 10 extra closed questions and one open question. Resident doctors are not satisfied with the educational environment of Greek hospitals. |

| Khan et al, 2017 42 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | Residents of Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, Gynecology and Obstetrics, General Surgery. | PHEEM | Mirpur City Teaching Hospital, Pakistan | Evaluate the educational environment of medical residency programs. | 82 | 90.7(15.6) | A; 30.2(5.9) | Not described . | Not described. | Higher scores in the teaching and autonomy subscores. The specialty with the highest score was Internal Medicine followed by Pediatrics. |

| T:38.9(7.1) | ||||||||||||

| S:21.6(5.8) | ||||||||||||

| Khoja, 2015 43 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | Family medicine residents | PHEEM | Family medicine residents from 4 centers | Assess the educational environment and differences between genders, training level and hospital center. | 91 | 67.1 (20.1) | A: 24.2(7.1) | Safe environment, without racial discrimination, teachers encourage independence. | Accommodation and food during shifts, lack of career guidance, excessive workload. | Very low overall score. There was a difference between the centers. More advanced residents have higher scores. There was no significant difference between genders. |

| T: 25.31(8.9) | ||||||||||||

| S:17.59 (5.6) | ||||||||||||

| Koutso-giannou et al, 201544 | Greece | Cross-sectional | Residents of various specialties | PHEEM | Residents of 83 hospitals and 41 city halls | Validation of the instrument, Greek version with 6 response degrees. | 731 | Not assessed | Not assessed | Absence of racial and sexual discrimination, good collaboration between doctors, accessible teachers. | Lack of career guidance, lack of information manual for residents, poor feedback. | Greek version is valid, reliable and sensitive for evaluating educational environment. |

| Llera et al, 2014 45 | Argentina | Cross-sectional | Residents in pediatrics, internal medicine, family medicine, cardiology, intensive care | PHEEM E MBI | Residents of 5 medical residency programs | Correlates the educational environment and burnout | 92 | 106.8 (13.98) | A:36.57 (5.69) | Not reported. | Not reported. | 19.6% burnout. Negative correlation between the educational environment and exhaustion and depersonalization. Positive correlation between educational environment and personal fulfillment. Correlation between burnout and PHEEM autonomy subscore |

| T:39.79 (6.19) | ||||||||||||

| S:30.48 (2.48) | ||||||||||||

| Mahen-dran et al, 201346 | Singapore | Cross-sectional | Psychiatry residents | PHEEM | Two residency models: British and American | To compare the PHEEM results in the 2 residency models | 60 | 109.30 | Worst scores on the teaching subscale | Absence of racial and sexual discrimination, protected study time, absence of inappropriate tasks | Lack of clear expectations, lack of teaching skills by teachers, few learning opportunities. | There was no difference in PHEEM between the 2 residency models. Worst scores on the teaching subscale |

| Ong et al, 201947 | Singapore | Cross-sectional | Internal medicine residents | PHEEM | Internal Medicine Program | To assess educational environment, compare results by gender and training level, and evaluate areas for improvement. | 136 | 112.2 (16.7) | A: 38.5(6.18) | No racial and sexual discrimination, feeling of belonging to the team, good collaboration with co-workers. | Excessive workload, little contact with teachers and lack of feedback, lack of adequate food during shifts. | There was no difference between genders and training levels. |

| T: 42.79 (6.49) | ||||||||||||

| S:30.93(5.07) | ||||||||||||

| Papaefstathiou et al, 2019 48 | Greece | Cross-sectional | Resident doctors (surgery, internal medicine and laboratory) | Greek version of PHEEM, CBI, JSM | Several hospitals in Greece. | To evaluate the relationship between the educational environment and professional stress with the development of burnout. | 269 | 46.26 (14.54 ) | A: 42.09 (16.36) | Not reported | Not reported | Different scoring in the Greek version of PHEEM (0-100): 0-25: very negative; 26-40: negative; 41-50: more negative points; 51-60: more positive points; 61-75: positive; 76-100: very positive Educational environment has more negative points than positive points in total and in the 3 subscales. The total PHEEM score and the 3 subscales correlated negatively with burnout (CBI). Positive correlation between stress level and burnout and personal exhaustion. |

| Greek version - different scoring system (41-50: more negative points). | T: 46.8 (19.51) | |||||||||||

| S: 49.59 (14.33) | ||||||||||||

| Greek version - different scoring system (41-50: more negative points). | ||||||||||||

| Pinnock et al , 2009 49 | New Zealand | Cross-sectional | Pediatrics residents | PHEEM | Pediatrics residents attending early and advanced residency years. | To evaluate the educational environment of pediatric residency in New Zealand. | 53 | Early years: 106.3 (18.3) | Early years: A; 37.4(6.3) | Feeling part of the team, teachers with good teaching and communication skills, absence of racism and racial discrimination, adequate levels of responsibility. | Accommodation during shifts, few opportunities for counseling for residents with difficulties, lack of information manual and guidance. | Residents in more advanced years evaluated the educational environment better than residents in the early years. |

| Advanced years; 114.2 (17.8) | T:39.6(8.7) | |||||||||||

| S:29.4(5.7) | ||||||||||||

| Advanced years: A:39.5(5.7) | ||||||||||||

| T:44.1(8.1) | ||||||||||||

| S:30.5(5.5) | ||||||||||||

| Posada Uribe et al, 2021 50 | Colombia | Cross-sectional | Residents of clinical and surgical specialties | PHEEM and WEMWBS | Residents of clinical and surgical specialties | To determine the relationship between the educational environment and well-being | 131 | 107.96 (18.88) | Not reported. | Not described | Not described | Positive correlation between educational environment and assessment of well-being through two scales. |

| Puranitee et al, 2019 51 | Thailand | Cross-sectional | Pediatrics residents | PHEEM, MSI, WRQoL | Department of Pediatrics at a hospital in Bangkok | To evaluate the association between burnout and the educational environment and work-related quality of life | 41 | 112.7 (11.2) | It does not describe the average. | Not described. | Food during the shifts (mentioned as the item with the lowest PHEEM score) | Emotional exhaustion and educational environment correlate with quality of life at work. Positive correlation between educational environment and quality of life in the workplace. Considers that PHEEM may not be the appropriate instrument to assess the educational environment in Thailand. |

| A: 88% - positive perception | ||||||||||||

| T: 51% more positive than negative points, but needs improvement (scores between 31-45) | ||||||||||||

| S: 85% more positive than negative points | ||||||||||||

| Sandhu et al, 2018 52 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | Resident doctors from different specialties (internal medicine, general surgery, gynecology and pediatrics) | PHEEM | Hospital in the city of Lahore, Pakistan. | To determine the quality of residents’ educational environment. | 87 | 90.49 (15.4) | A: 30.16 (5.85) | Adequate level of responsibility, teachers with excellent communication and teaching skills, collaboration with other residents, team feeling | Non-compliance with working hours (highlighted as the lowest scoring item), food during shifts, accommodation during shifts, lack of time reserved for study. | Highest score for the neurology department and lowest score for anesthesiology. 71.3% of residents classified the work environment as “more positive than negative, but with room for improvement”. |

| T: 38.87 (7.03) | ||||||||||||

| S: 21.45 (5.75) | ||||||||||||

| Sheikh et al, 2017 53 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | Resident doctors | PHEEM | One public hospital and 6 private hospitals in Karachi, Pakistan | To evaluate the educational environment of residency programs and identify differences between public and private sectors of tertiary hospitals. | 302 | 93.96 (20. 79 ) | A: 32.83(7.34) | Good collaboration from other residents, teachers with good teaching skills, adequate level of responsibility. | Food during shifts, access to a document listing the skills expected of residents, calls at inappropriate times. | Total PHEEM score was significantly higher in private hospitals than in public ones. Slightly modified version to better meet regional issues, for example appropriate workload (there is no national regulation). |

| T: 37.27(9.43) | ||||||||||||

| S: 23.97(6.76) | ||||||||||||

| Shimizu et al, 2013 54 | Japan | Cross-sectional | Resident doctors | PHEEM and GM- ITE | 21 teaching hospitals in Japan | To evaluate the relationship between the educational environment and the residents’ medical knowledge assessed by an exam at the end of residency. | 206 | 57.6(5.4) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Medical knowledge was significantly associated with the educational environment of hospitals. The presence of an internal medicine department and a rural location were associated with a higher score. |

| Vieira,20087 | Brazil | Cross-sectional | Residents of internal medicine, anesthesiology and general surgery (HC) and various specialties (HGCR). | PHEEM | Hospital das Clínicas de São Paulo and Hospital Governador Celso Ramos (Florianópolis) | To validate the use of PHEEM translated into Portuguese and evaluate the reliability of its use. | 306 | Not assessed | A: 33.9 (8.6) | Absence of racism and sexual discrimination, adequate level of responsibility, accessible teachers, opportunity to practice procedures. | Food during shifts, non-compliance with workload, absence of specific periods for studying, lack of feedback from teachers, lack of culture of not blaming the resident. | Highlighted the importance of improvements in the main factors related to the perception of teaching (feedback, study period). Use of PHEEM is reliable to assess educational environment. Greater autonomy for internal medicine residents. Higher score in the perception of teaching by the anesthesiology residents. It perceived similar social support in the three areas. |

| T: 35.0 (10) | ||||||||||||

| S: 26.6 (6.0) | ||||||||||||

| Waheed et al, 201955 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | Gynecology and obstetrics residents | PHEEM | All gynecology and obstetrics residency programs in Lahore (11 institutions - 5 private and 6 public ones). | To determine the quality of the educational environment for GO residents. | 368 (only 4 men) | 63.68 (29.6) | A: 23.94 (10.28) | They feel satisfied with their work, adequate working hours, food during the shift. | Teachers lack communication skills, little collaboration from other residents, and lack of clinical supervision at all times. | The majority of residents classified the educational environment as having “many problems”, highlighting the need for improvements. Higher PHEEM scores in public hospital residents. |

| T: 20.16 ( 11.9) | ||||||||||||

| S: 18.42 ( 8.04) |

Source: prepared by the authors

Legend : CBI Copenhagen Burnout Inventory; GM- ITE General Medicine Internal Training Examination; JSM-G ; Job Stress Measure Greek version; MBI Maslach Burnout Inventory; OLBI: Oldenburg Burnout Inventory; WEMWBS: Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale; WRQoL work related quality of life scale.

The 36 studies included in the review were carried out in 22 countries and 5 continents, 16 in Asia, 8 in Europe, 7 in America, 3 in Africa and 2 in Oceania. One study was carried out in 2 countries, the United States and Saudi Arabia23. Only one study was carried out in Brazil7. Thirty studies were published as of 2013. The studies included internal medicine residents, clinical specialties, general surgery and surgical specialties, emergency medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, anesthesiology, intensive care, obstetrics and gynecology, and laboratory medicine, among others. The number of participants who answered the questionnaire ranged from 19 to 3,456, with twenty-four studies including more than 100 residents.

In 22 studies6),(8),(23),(27)-(29),(31)-(33),(35),(37)-(39),(42),(45)-(47),(49)-(53 the mean PHEEM total score was between 81-120, indicating a more positive than negative educational environment, but with room for improvement. In eight studies, carried out in Saudi Arabia30),(43, Pakistan24),(55, Ethiopia34, Japan54, Turkey25 and Greece48, the mean total score was 41-80, indicating an educational environment with many problems. None of the studies showed that the educational environment was considered very bad (score below 40) or excellent (score above 120). Six studies7),(26),(36),(40),(41),(44 did not show the total PHEEM score.

Twenty-four studies reported scores on the autonomy, teaching, and social support subscales. In the autonomy subscale, seventeen studies indicated results between 29-42, indicating a more positive than negative perception, whereas seven studies scored between 15-28, indicating a negative perception. No study scored between 0-14 or between 43-56, which would respectively show a very poor or excellent perception. In the teaching subscale, in seventeen studies the results were between 31-45, showing that the program is moving in the right direction, with six showing scores between 16-30, indicating the need for the training of teachers and preceptors. No study scored between 0-15 or between 46-60, which would reveal, respectively, teachers with low teaching quality or model teachers. In the social support subscale, eleven studies showed results between 12-22, indicating a non-pleasant environment and twelve studies between 23-33 indicating more pros than cons. No study scored between 0-11 or between 34-44, which would indicate a lack of social support or an excellently support environment.

The main positive points highlighted were low racial and sexual discrimination, teamwork, collaboration with other doctors, adequate level of responsibilities, accessible teachers, teachers with good teaching skills, good learning opportunities, opportunity to participate in educational events and a safe environment .

The main problems highlighted when analyzing the PHEEM responses were: food during the shifts in twenty studies; lack of an information manual for residents in twelve studies; accommodation during the shifts in ten studies; excessive workload in nine studies, in addition to lack of protected time for study; lack of feedback from preceptors and a culture of blaming the resident. Although, in several studies, low sexual and racial discrimination was cited as a positive factor, other studies carried out in Saudi Arabia31, Morocco28, Pakistan24 and Greece41 showed sexual and racial discrimination as an important problem in those countries.

Some studies point out differences between specialties. Vieira7 evaluated residents from different specialties and observed higher scores on the autonomy scale among internal medicine residents and a greater perception of teaching in anesthesiology residents. Sandhu et al.52 observed higher PHEEM scores in the questionnaires answered by neurology residents and lower scores among anesthesiology residents. In the study by Berrani et al.28, laboratory medicine residents had higher PHEEM values than residents from other specialties. Ezomilke et al.33 showed that gynecology and obstetrics residents scored higher than those in pediatrics and surgery in the total PHEEM score and in the teaching and social support categories. Bigotte Vieira et al.29 showed that residents in endocrinology, cardiology, anesthesiology, family medicine and gastroenterology were more satisfied with the educational environment than those from other specialties. And recently, in the study by González et al.37, the specialties with the highest scores in the total PHEEM score were ophthalmology, dermatology, pathological anatomy, while general surgery, gynecology and obstetrics and cardiology had the lowest scores.

Three studies evaluated the relationship between educational environment and burnout. Llera et al.45 showed a negative correlation between the educational environment, exhaustion and depersonalization and a positive correlation between the educational environment and personal fulfillment. Papaefstathiou et al.48 demonstrated that the total PHEEM score was negatively correlated with burnout. The perception of the educational environment was inversely proportional to the burnout status among psychiatry residents in the study by Chew et al.8. Other studies showed a positive correlation between the resident’s well-being and the educational environment50 and a correlation between emotional exhaustion and the educational environment with quality of life at work51.

One study54 showed that medical knowledge, assessed through IGM-ITE (General Medicine Internal Training Examination) at the end of the residency, was significantly associated with the educational environment. Higher PHEEM scores were associated with better results on IGM-ITE exams.

DISCUSSION

The PHEEM is a reliable instrument for evaluating the educational environment in medical residency programs and has been validated in different parts of the world. This review assessed the use of PHEEM in medical residency programs of different specialties, in several countries, evaluating the total score and subscores of PHEEM and mainly highlighting the positive and negative points assessed with the aim of identifying aspects requiring improvement in the educational environment of the residency programs.

Most studies disclosed an educational environment in medical residency programs that was more positive than negative, although there was room for improvement. When evaluating the subscales, the perception of autonomy was more positive than negative and the perception of teaching revealed that the majority of programs are moving in the right direction. However, when evaluating social support, studies showed results divided between an environment that was not pleasant and an environment that had more pros than cons.

The main positive points reported in the autonomy subscale were feeling part of the work team and adequate level of responsibility during training; in the teaching subscale, available and accessible teachers stand out, as well as teachers with good teaching skills, good learning opportunities, opportunity to participate in educational events; in the social support subscale, low racial and sexual discrimination, collaboration with other doctors and a safe environment were reported. Most of the problems highlighted in the studies were related to social support, with the lack of adequate food during shifts being the main problem in most studies, regardless of the country or region, followed by inadequate accommodation and a culture of blaming the resident. In a study carried out in Morocco28, sexual discrimination was considered a problem by half of the residents, associated with racial discrimination, problems also observed in Saudi Arabia31, Pakistan24 and Greece41, demonstrating that regional and cultural factors influence the educational environment, especially regarding social support of medical residency programs. In the perception of autonomy subscale, the main negative points were lack of an information manual and clinical protocols for residents, excessive workload, and being called at inappropriate times, while in the teaching subscale, the main problems highlighted were lack of protected time for study and lack of feedback from preceptors.

Medical residency programs have realities that vary greatly from one country to another and even from one region to another within the same country. There is a scarcity of studies evaluating the educational environment in medical residency programs in Brazil. Only one study7, carried out more than a decade ago, demonstrated the reliability of the PHEEM translated into Portuguese, evaluating the educational environment in medical residency programs at Hospital das Clinicas in São Paulo and in a hospital in Florianópolis. The obtained scores revealed a more positive than negative perception of autonomy, a perception of teaching moving in the right direction and a perception of more pros than cons regarding social support. The most positive points were the absence of racism and sexual discrimination, an adequate level of responsibility, accessible teachers and opportunities to practice procedures. The points considered to be the most problematic ones were food during shifts, excessive working hours, lack of time reserved for study, lack of feedback from teachers and a culture of blaming the resident.

Analysis of the PHEEM results allows us to point out some points for improvement. Excessive workload is a frequent problem in residency programs. In Brazil, the National Medical Residency Commission regulates the maximum weekly working hours of 60 hours of work, post-shift rest and at least one day off per week (CNRM, Law n. 6,932, 07/07/1981)56. Additionally, protected study time must be reserved during the residents’ standard week. Feedback is essential in the teaching-learning process. Preceptors must be trained and encouraged to provide feedback to residents during residency activities. The development and implementation of manuals for residents and clinical protocols can improve the residents’ perception of autonomy.

Issues related to food and accommodation during shifts are among the negative aspects most often cited by residents from all different programs in different countries and must be discussed and resolved together with the hospital administration.

This review has some limitations. Some studies did not provide the total PHEEM score, others did not provide subscale scores, and some did not show the score for each item on the scale. Regional and cultural differences in the educational environment make it difficult to generalize results.

CONCLUSION

The use of the PHEEM questionnaire showed that in most medical residency programs the educational environment was more positive than negative, however with room for improvement. The highlighted positive points were low racial and sexual discrimination, possibility of working as a team and collaboration with other doctors, adequate level of responsibilities, accessible teachers with good teaching skills, good learning opportunities and participation in educational events. The main indicated negative points were lack of adequate food and accommodation during the shifts, followed by excessive workload, lack of feedback from preceptors and lack of protected time for study, in addition to the culture of blaming the resident. Therefore, improving the educational environment in medical residency must involve efforts especially related to improving social support, aiming to improve the learning capacity and preserve the mental health of resident doctors.

REFERENCES

1. Brasil. Decreto nº 80.281, de 5 de setembro de 1977. Brasília; 1977. [ Links ]

2. Genn JM. AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 23 (Part 1): curriculum, environment, climate, quality and change in medical education-a unifying perspective. Med Teach. 2001 July; 23(4):337-44. [ Links ]

3. Harden RM. The learning environment and the curriculum. Med Teach . 2001 July;23(4):335-6. [ Links ]

4. Chan CY, Sum MY, Lim WS, Chew NW, Samarasekera DD, Sim K. Adoption and correlates of Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM) in the evaluation of learning environments: a systematic review. Med Teach . 2016 Dec;38(12):1248-55. [ Links ]

5. Roff S, McAleer S, Skinner A. Development and validation of an instrument to measure the postgraduate clinical learning and teaching educational environment for hospital-based junior doctors in the UK. Med Teach . 2005 June;27(4):326-31. [ Links ]

6. Herrera CA, Olivos T, Román JA, Larraín A, Pizarro M, Solís N, et al. Evaluación del ambiente educacional en programas de especialización médica. Rev Med Chil. 2012;140(12):1554-61. [ Links ]

7. Vieira JE. The Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM) questionnaire identifies quality of instruction as a key factor predicting academic achievement. Clinics (São Paulo). 2008 Dec;63(6):741-6. [ Links ]

8. Chew QH, Cleland J, Sim K. Burn-out and relationship with the learning environment among psychiatry residents: a longitudinal study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:E060148. [ Links ]

9. Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). Aromataris E, Munn Z , editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. Available fromhttps://synthesismanual.jbi.global. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12 [ Links ]

10. TriccoAC , Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct 2;169(7):467-73. [ Links ]

11. Algaid SA. Assessment of educational environment for interns using Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM). JTU Med Sc. 2010;5(1):1-12. [ Links ]

12. Boor K, Scheele F, Van Der Vleuten CPM, Scherpbier AJJA, Teunissen PW, Sijtsma K. Psychometric properties of an instrument to measure the clinical learning environment. Med Educ. 2007;41(1):92-9. [ Links ]

13. Beer W de, Clark H. Four years of prevocational Community Based Attachments in New Zealand: a review. N Z Med J. 2021 July 30;134(1539):56-62. [ Links ]

14. Gooneratne IK, Munasinghe SR, Siriwardena C, Olupeliyawa AM, Karunathilake I. Assessment of psychometric properties of a modified PHEEM questionnaire. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2008 Dec;37(12):993-7. [ Links ]

15. Kanashiro J, McAleer S, Roff S. Assessing the educational environment in the operating room-a measure of resident perception at one Canadian institution. Surgery. 2006 Feb;139(2):150-8. [ Links ]

16. Mohamed Cassim S. Transforming culture. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(Suppl 1): A58. [ Links ]

17. Naidoo KL, Van Wyk JM, Adhikari M. The learning environment of pediatric interns in South Africa. BMC Med Educ . 2017 Nov 29;17(1):235. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1080-3. [ Links ]

18. Ong AM, Fong WW, Chan AK, Phua GC, Tham CK. Evaluating the educational environment in a residency programme in Singapore: can we help reduce burnout rates? Singapore Med J. 2020 Sept;61(9):476-82. [ Links ]

19. Rammos A, Tatsi K, Bellos S, Dimoliatis IDK. Translation into Greek of the Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM). Arch Hellen Med. 2011;28(1):48-56. [ Links ]

20. Riquelme A, Herrera C, Aranis C, Oporto J, Padilla O. Psychometric analyses and internal consistency of the PHEEM questionnaire to measure the clinical learning environment in the clerkship of a Medical School in Chile. Med Teach . 2009 June;31(6): e221-5. [ Links ]

21. Shokoohi S, Hossein Emami A, Mohammadi A, Ahmadi S, Mojtahedzadeh R. Psychometric properties of the Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure in an Iranian hospital setting. Med Educ Online. 2014 Aug 8; 19:24546. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.3402/meo. v19.24546. [ Links ]

22. Wall D, Clapham M, Riquelme A, Vieira J, Cartmill R, Aspegren K, et al. Is PHEEM a multi-dimensional instrument? An international perspective. Med Teach . 2009 Nov;31(11): e521-7. [ Links ]

23. Aalam A, Zocchi M, Alyami K, Shalabi A, Bakhsh A, Alsufyani A, et al. Perceptions of emergency medicine residents on the quality of residency training in the United States and Saudi Arabia. World J Emerg Med. 2018;9(1):5-12. [ Links ]

24. Ahmad SA, Anwa A, Tahir H, Mohydin M, Gauha F, Aslam R, et al. Perception of the educational environment of post-graduate residents in teaching hospitals across Pakistan. PJMHS. 2021;15(12):3218-21. [ Links ]

25. Akdeniz M, Yaman H, Senol Y, Akbayin Z, Cihan FG, Celik SB, et al. Family practice in Turkey: views of family practice residents. Postgrad Med. 2011;123(3):144-9. [ Links ]

26. Aspegren K, Bastholt L, Bested KM, Bonnesen T, Ejlersen E, Fog I, et al. Validation of the PHEEM instrument in a Danish hospital setting. Med Teach . 2007 June;29(5):498-500. [ Links ]

27. Bari A, Khan RA, Rathore AW. Postgraduate residents’ perception of the clinical learning environment; use of postgraduate hospital educational environment measure (PHEEM) in Pakistani context. J Pak Med Assoc. 2018 Mar;68(3):417-22. [ Links ]

28. Berrani H, Abouqal R, Izgua AT. Moroccan residents’ perception of hospital learning environment measured with French version of the postgraduate hospital educational environment measure. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2020 Jan; 17:4. doi: https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2020.17.4. [ Links ]

29. Bigotte Vieira M, Godinho P, Gaibino N, Dias R, Sousa A, Madanelo I, et al. Medical residency’ satisfaction in Portugal. Acta Med Por. 2016;29(12):839-53. [ Links ]

30. Binsaleh S, Babaeer A, Alkhayal A, Madbouly K. Evaluation of the learning environment of urology residency training using the Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure inventory. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015 Apr 2 ; 6:271-7. [ Links ]

31. BuAli WH, Khan AS, Al-Qahtani MH, Aldossary S. Evaluation of hospital-learning environment for pediatric residency in eastern region of Saudi Arabia. J Educ Eval Health Prof . 2015 Apr 18; 12:14. doi: https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2015.12.14. [ Links ]

32. Clapham M, Wall D, Batchelor A. Educational environment in intensive care medicine: use of Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM). Med Teach . 2007 Sept;29(6): e184-91. [ Links ]

33. Ezomike UO, Udeh EI, Ugwu EO, Nwangwu EI, Nwosu NI, Ughasoro MD, et al. Evaluation of postgraduate educational environment in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Niger J Clin Pract. 2020 Nov;23(11):1583-9. [ Links ]

34. Fisseha H, Mulugeta B, Argaw AM, Kassu RA. Internal medicine residents’ perceptions of the learning environment of a residency training program in Ethiopia: a mixed methods study. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2021 Oct 7; 12:1175-83. [ Links ]

35. Flaherty GT, Connolly R, O’Brien T. Measurement of the postgraduate educational environment of junior doctors training in Medicine at an Irish University Teaching Hospital. Ir J Med Sci. 2016 Aug;185(3):565-71. [ Links ]

36. Galli A, Brissón ME, Soler C, Lapresa S, De Lima AA. Assessment of educational environment in cardiology residencies. Rev Argent Cardiol. 2014;82(5):373-8. [ Links ]

37. González C, Ahtamon A, Brokering W, Budge M C, Cadagan M J, Jofre P, et al. Perception of the educational environment in residents of medical specialties in Chilean universities. Rev Med Chil e. 2022; 150:381-90. [ Links ]

38. Gough J, Bullen M, Donath S. PHEEM “downunder”. Med Teach . 2010;32(2):161-3. [ Links ]

39. Goulding JM, Passi V. Evaluation of the educational climate for specialty trainees in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016 June;30(6):951-5. [ Links ]

40. Jalili M, Mortaz Hejri S, Ghalandari M, Moradi-Lakeh M, Mirzazadeh A, Roff S. Validating modified PHEEM questionnaire for measuring educational environment in academic emergency departments. Arch Iran Med. 2014 May;17(5):372-7. [ Links ]

41. Karathanos V, Koutsogiannou P, Bellos S, Kiosses V, Jelastopulu E, Dimoliatis I. How 731 residents in all specialties throughout Greece rated the quality of their education: evaluation of the educational environment of Greek hospitals by PHEEM (Postgraduate Hospital Education Environment Measure) Arch Hellen Med . 2015;32(6):743-57. [ Links ]

42. Khan A M, Iqbal W, Khan S A. Assessment of educational environment at a public sector Medical College in Kashmir. PJMHS . 2017;11(3):1072-4. [ Links ]

43. Khoja AT. Evaluation of the educational environment of the Saudi family medicine residency training program. J Family Community Med. 2015 Jan-Apr;22(1):49-56. [ Links ]

44. Koutsogiannou P, Dimoliatis ID, Mavridis D, Bellos S, Karathanos V, Jelastopulu E. Validation of the Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM) in a sample of 731 Greek residents. BMC Res Notes. 2015 Nov 30; 8:734. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1720-9. [ Links ]

45. Llera J, Durante E. Correlation between the educational environment and burn-out syndrome in residency programs at a university hospital. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2014 Feb;112(1):6-11. [ Links ]

46. Mahendran R, Broekman B, Wong JC, Lai YM, Kua EH. The educational environment: comparisons of the British and American postgraduate psychiatry training programmes in an Asian setting. Med Teach . 2013 Nov;35(11):959-61. [ Links ]

47. Ong AM, Fong WW, Chan AK, Phua GC, Tham CK. Using the Postgraduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure to identify areas for improvement in a Singaporean residency program. J Grad Med Educ . 2019 Aug;11(4 Suppl):73-8. [ Links ]

48. Papaefstathiou E, Tsounis A, Papaefstathiou E, Malliarou M, Sergentanis T, Sarafis P. Impact of hospital educational environment and occupational stress on burnout among Greek medical residents. BMC Res Notes . 2019 May 22;12(1):281. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4326-9. [ Links ]

49. Pinnock R, Reed P, Wright M. The learning environment of pediatric trainees in New Zealand. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009 Sept;45(9):529-34. [ Links ]

50. Posada Uribe MA, Vargas González V, Orrego Morales C, Cataño C, Vásquez EM, Restrepo D. Educational environment and mental wellbeing of medical and surgical postgraduate residents in Medellin, Colombia. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr (Engl Ed). 2021 Apr 17: S0034-7450(21)00040-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcp.2021.02.003. [ Links ]

51. Puranitee P, Stevens FFCJ, Pakakasama S, Plitponkarnpim A, Vallibhakara SA, Busari JO, et al. Exploring burnout and the association with the educational climate in pediatric residents in Thailand. BMC Med Educ . 2019 July 5;19(1):245. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1687-7. Erratum in: BMC Med Educ . 2019 Aug 1;19(1):296. [ Links ]

52. Sandhu A, Liaqat N, Waheed K, Ejaz S, Khanum A, Butt A, et al. Evaluation of educational environment for postgraduate residents using Post Graduate Hospital Educational Environment Measure. J Pak Med Assoc . 2018 May;68(5):790-2. [ Links ]

53. Sheikh S, Kumari B, Obaid M, Khalid N. Assessment of postgraduate educational environment in public and private hospitals of Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc . 2017 Feb;67(2):171-7. [ Links ]

54. Shimizu T, Tsugawa Y, Tanoue Y, Konishi R, Nishizaki Y, Kishimoto M, et al. The hospital educational environment and performance of residents in the General Medicine In-Training Examination: a multicenter study in Japan. Int J Gen Med. 2013 July 29; 6:637-40. [ Links ]

55. Waheed K, Al-Eraky M, Ejaz S, Khanum A, Naumeri F. Educational environment for residents in obstetrics and gynecology working in teaching hospitals of Lahore, Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. J Pak Med Assoc . 2019 July;69(7):1029-32. [ Links ]

56. Brasil. Lei nº 6.932, de 7 de julho de 1981. Dispõe sobre as atividades do médico residente. Diário Oficial da União; 1981. Seção 1, p. 12789. [ Links ]

Received: March 30, 2023; Accepted: December 21, 2023

texto em

texto em