The phenomenon of violence in schools has been analyzed from different perspectives that differ in their comprehensive approach and definition of violence as a conceptual category. Based on the review of scientific literature of the last fifty years, three perspectives of analysis are identified: criminological, psychoeducational and socio-educational. We highlight the risk of identifying violence with delinquency, as the criminological perspective suggests. We do not agree either with the psycho-educational perspectives that focus on bullying, in relation to dichotomous relationships between “aggressor-victim”. They individualize responsibilities and build stereotyped psychic profiles. Framed in the socio-educational perspective, we claim the need to consider the sociocultural and relational contexts in which violence situations arise and, in turn, to explore the meanings assigned by the actors in educational environments (DI NAPOLI, 2016).

The meanings attributed, and practices adopted by students in their youth are frequently ignored by secondary school2 authorities when dealing with conflicts or violence situations and when planning strategies of school coexistence. The hypothesis posed by Dubet and Martuccelli (1998) is that secondary school tends to reproduce the same dispositives of primary school, targeted to children education, without taking into account the particular characteristics of being young. In contrast with children, the young start to experiment a relative autonomy from their family and school contexts and, additionally, their peer group gains more ascendancy in their subjective configuration. “In the adolescence, a non-educational self, a subjectivity and a collective life, independent from school, are built, ‘affecting’ school life” (DUBET; MARTUCELLI, 1998, p. 196-197).

In the same educational institution, the young meet, share spaces, make friends, identify themselves with certain groups, at the same time that disagreements, conflicts and rivalries arise. We consider that school socialization and young’s sociability converge, and also come into tension in the process of subjectivity construction of students (WEISS, 2015).

This work is aimed at problematizing the conflict, coexistence and violence in secondary schools based on the analysis of two “critical incidents” in which two groups of male students from two different schools exhibited a violent behavior against each other, but they were unable to perceive it as a violent event. We use the analytic category violence as the actions that cause pain to them, are not agreed upon when they happen, and violate the “implicit codes” of school coexistence. Being framed within a ludic context, the protagonists resignified the aggressions they inflict themselves (punches and humiliations) as a way of interacting with others without considering this behavior conflictive or violent.

THEORETICAL FRAME

SOCIABILITY AS A DIMENSION OF ANALYSIS

The concept of sociability proposed by Simmel (2002) is useful to understand the ways of interacting of the young at school, i.e. the ways of being together “just because”, beyond the coercions of any calculation, or any other purpose. It is socialization in its pure form, through its ludic nature. The artificial, unreal and superficial characteristics of sociability, inherent to its pure form, entail to play “ ‘as if’ everybody is equal and at the same time as if each one is specially honored” (SIMMEL, 2002, p. 90). There is not any external purpose to the sociable moment as such.

The sociability requires to maintain a balance among individuals, thus personal interests and objective meanings must be left aside (such as wealth, and/or social position) as well as the aspects purely subjective (character, mood). Likewise, the way of acting the good manners becomes very significant. The sense of tact has a special relevance according to the sociologist from Berlin “because it governs the individual self-regulation in a personal relationship with others, when there are no external or selfish interests that can assume the regulation”3 (SIMMEL, 2002, p. 85, own translation). Individual satisfaction depends on others’ satisfaction; therefore, nobody could find her/his satisfaction at others’ expense. The interactions of sociability are not constituted by the way they are carried out, but by the vitality of the individuals that make up them, expressing the pleasure of being with the other. Based on this concept, Simmel (2002) combined what appears to be superficial with what is more profound in life. Consequently, with this framework, we can analyze symmetrical relationships among individuals. Some examples of highly frequent sociability situations in the young, mentioned by this author, are the following: the game, coquetry and conversation.

In this respect, Elias and Dunning tackled sociability in relation to leisure-type activities. In a first work, they considered it as a continuum from a formal end to another of informal nature. In the formal end, the activities of sociability correlate somehow with work environment such as participating with colleagues in a leisure-type activity organized by the company. Instead, the informal end is characterized by those activities that have nothing to do with work, such as meeting in a bar or party, and that have as their purpose to “be with other people without doing anything else, as a purpose in itself”4 (ELIAS; DUNNING, 1992, p. 90, own translation).

In a further article, these authors introduced sociability as one of the three elements that constitute leisure (along with motility and emotional arousal). Leisure would be the sole public sphere in which individuals can decide their course of actions, based mainly in their own satisfaction, reducing the rigidity of self-control and allowing themselves a greater emotional stimulation. Consequently, the authors circumscribed the notion of sociability exclusively to informal leisure-type activities consisting in the encounter “to enjoy each other’s company, i.e. to enjoy emotional warmth, social integration and stimulation that produce the presence of others”5 (ELIAS; DUNNING, 1992, p. 152, own translation).

In our perspective, the approach of Elias and Dunning (1992) was inspired by Simmel’s idea about sociability, in which to be together is a purpose in itself. Nevertheless, in contrast to the sociologist from Berlin, they distinguished the ludic nature of some activities from sociability. Games, including sports, would be part of the leisure-type activities they nominated as mimetic, different from leisure sociability such as meetings in bars or going to a party. Both activities are considered as part of the leisure sphere and contribute to neutralize “the routinization inherent to the relatively impersonal contacts that prevail in non-leisure spheres of these societies”6 (ELIAS; DUNNING, 1992, p. 152, own translation).

The mimetic activities arise emotions that although they are not the same, they are closely related to those experienced by individuals in the course of their non-leisure life. In this context, feelings are altered, becoming less sharp. In sociability activities, people are gathered without “acting” for others or for themselves. The “as if” and the artificial world of sociability, proposed by Simmel (2002), are attributed to mimetic activities by Elias and Dunning (1992), and in the sociability activities, the relatively spontaneous encounter appears as a purpose in itself.

Finally, it is worth mentioning Martuccelli’s perspective (2007) who asserted that sociability has been a dimension of social interactions neglected by Sociology in relation to the Modern project. From his approach to individuation processes, he claimed that “the sociability compels us to look beyond pure interactive strategies, towards the quality of relations”7 (MARTUCCELLI, 2007, p. 150, own translation).

Sociability aims at the quality of the social bond in a context of ductile and elastic situations. Individuals and social life are founded on diverse situational sociabilities that need to be studied in their singularity, even those that appear to be standardized. Martuccelli (2007) gave as an example the school class. Despite being a standardized situation, sociability between students and teacher varies from class to class regarding the bonds that individuals built in this situation during the year. “What makes the difference among the situations, apart from the context variations, is the nature of sociability among individuals”8 (MARTUCCELLI, 2007, p. 163, own translation).

In this work, we are interested in stressing that the type of sociability defines the social ties established with the other. That is, similar bonds that correspond to different sociabilities can have diverse expressions.

VIOLENCE, SELF-REGULATION AND INFORMALIZATION

In relation to sociability conceptualization, Simmel as well as Elias and Dunning referred to the topic of self-regulation in the interaction among individuals. It constitutes a heuristic clue to understand the behavior of our young and their expressions of violence. Sociability requires a sense of tact (SIMMEL, 2002) and it enables the relaxation of self-control codes (ELIAS; DUNNING, 1992). In accordance with Elias (2009), certain types of sociability generate the reconfiguration of the formality-informality span of social behaviors. The reference to the diachronic dimension of the informality process is necessary to tackle this topic. According to Elias (2009, p. 185-186, own translation), living together in a civilized way:

Includes very much more than just non-violence. It includes not just the negative aspect implied by the disappearance of acts of violence from human relationships, but also an entire field of positive characteristics, above all the specific molding of individuals in groups which can only take place when the threat that people will attack each other physically, or force others through their stronger muscles or better weapons to do things they could not otherwise do, has been banished from their social relations.9

In line with Elias (2011), in his theory of civilizing processes, he claimed that with the increase of the social interdependency network, the physical violence monopolized by the State is secluded, not affecting the life of individuals, except in isolated cases. A psychic apparatus emerges in which social codes, to which the individual has been adapted by external pressure at first, i.e., by means of external constraint, become then, self-restraint. The latter is the result partly of a conscious domain, and partly of a non-conscious way expressed in customs and habits. Over time, a certain fear or even a deep repulsion, a sort of disgust, upon the use of physical violence is being developed by people. Based on an increasingly strong social control, every form of pleasure associated with expressions of cruelty, joy in the destruction and torment of others “hemmed in by threats of displeasure, have gradually come to express themselves only indirectly, in a ‘refined’ form through a series of lateral mechanisms”10 (ELIAS, 2011, p. 184, own translation). In terms of Simmel, the sense of social tact is being progressively reconfigured. Thus, “as the constraint exerted by people on one another increases, the demand for ‘good behavior’ also raises more emphatically”11 (ELIAS, 2011, p. 159, own translation). Thus, the socially imposed constraints start to appear as if they were desired by the individuals themselves, by their personal impulses.

Moreover, Elias (2009, 2011) mentioned that, as a consequence of and conditioned by the turn from external constraint to self-restraint, a phenomenon of liberalization of individuals’ fixing forms takes place. A moment of relaxation of the habits may be present in the process of modeling the external constraint into self-restraint.12 A high degree of self-regulation of emotions enables certain relaxation of social codes of control and behaviors.

This impetus towards what Elias (2009) called informalization of conducts requires a high degree of individualization. As Wouters (2017), disciple of Elias, stated, the enlargement of possibilities of acceptable behaviors demands a greater degree of flexibility, precision and personal sensitivity to adjust oneself to each particular situation. Through this interpretative perspective, we can analyze a particular type of sociability in which the degree of self-regulation of emotions and the relaxation of behaviors lead to the development of violent practices which are tolerated within a ludic context.

METHODOLOGY

The incidents that are considered as empirical referents are part of a research work.13 Its general objective was aimed at understanding the perceptions regarding violence that students built in school life, based on a qualitative methodological strategy. The fieldwork was carried out in two secondary schools of State management in Avellaneda District, located in Buenos Aires Province, in the period 2012-2014. School A is situated in an industrial zone and the students interviewed were mainly from popular sectors, some of them lived in urban slums. School B is located in a residential area of middle-class people, close to a commercial zone. The students interviewed were mainly from middle class sectors.

The analysis of the critical incidents was based on: a) field notes taken at different times (students’ arrival and departure from school, before the beginning and after the ending of classes, during breaks) and spaces (classrooms, halls, school yard, convenience store/canteen and surrounding area); b) 16 in--depth interviews with students of 4th year from School B, and 5th year from School B; and c) a focus group composed of some students of the 5th year class self-called as “the bullying guys”.14

The data analysis was mainly based on the guidelines of the thematic analysis. It consists in the identification of patterns of meanings in the data and the creation of conceptual categories from emerging themes (FEREDAY; MUIR-COCHRANE, 2006). Using the computer support Atlas.ti 7.0, coding and categorization were carried out by means of a mixed inductive-deductive approach, defining thematic nuclei and categories with a greater inferential content. Thus two categories were defined, taking into account two emic expressions: a) “Harmless violence”, and b) “Flushing with embarrassment”.

Considering the ethical side of the matter, the students’ parents had to sign an authorization. A copy of those documents is kept in the school files, and another one remains with us. To keep the anonymity and preserve confidentiality as well as the identity of the young interviewed, the names of the students were modified. In each interview, students’ gender, school year, shift, and name of their school are indicated within parenthesis.

VIOLENCE AS A RITUALIZED PRACTICE OF SOCIABILITY AMONG STUDENTS

Sociability constitutes a productive dimension to study how students interact with each other, and the meanings they attribute to their actions. As previously mentioned, Martuccelli (2007) considered sociability of a situational nature, based on the quality of social relationships in diverse, ductile and elastic contexts. During our fieldwork, we observed the existence of situational sociabilities in each class, with variable levels of malleability, not only in the students of the same school class, but also among different subgroups of friends.

Some authors applied the category of violent sociability to refer to the use of physical force as a principle of regulation (pattern) that guides the courses of action among individuals in everyday life; and, besides, this principle structures social relationships, i.e., a specific social order (MACHADO DA SILVA, 2004, 2010; VISCARDI, 2002).

In his research work about urban violence in Rio de Janeiro slums (favelas), Machado da Silva (2004) claimed that violent sociability is a singular way of life in which physical force is no longer a means for action, regulated by the aims intended to be achieved. Instead, it becomes a principle of coordination (an “action regime”) of practices. In other words, violence gets rid of symbolic regulation, i.e., of its subordination to constraints and conditionings represented by material or ideal aims to which violence would have been useful in other circumstances. It becomes an end in itself, inseparable from its instrumental function as a means for action. In short, as the very meaning of the term “principle” suggests, violence explains by itself and self-regulates itself.

In the social contexts analyzed by the author, these types of interactions cause a deterioration of the quality of the interpersonal bonds:

Relationships with the Other are increasingly experienced and thought in the level of strictly interpersonal contacts taking place in the everyday practices. These interactions, in turn, start to be avoided to the extent possible because they would risk the interruption of the simple regular repetition of ordinary activities. Thus, it is in the interpersonal level that relationships with the Other become a matter of mistrust, fear and insecurity.15 (MACHADO DA SILVA, 2010, p. 287, own translation)

Viscardi (2002), in her research with students of secondary school in Montevideo city, pointed out the emergence of a violent sociability among the young in schools. It constitutes a socialization mechanism mediated by the use of the force in a ritualized logic that, at the same time, sets hierarchies within secondary school life. The relation with violence and the strategies of self-preservation against violence are part of the school life, generating a code of interaction among students, parallel to that of the educational institution. Both Brazilian and Uruguayan researchers agreed that the ordering principle of violent sociability is not opposed to other particular social orders, such as the State or school (also State-run); on the contrary, they coexist.

In our study, and according to our analytic interpretation, we observed a group of students that have built a sociability based on violent practices in School A as well as in School B. Nevertheless, as it is analyzed hereunder, this violent sociability has different characteristics from those referred to by the two abovementioned authors.

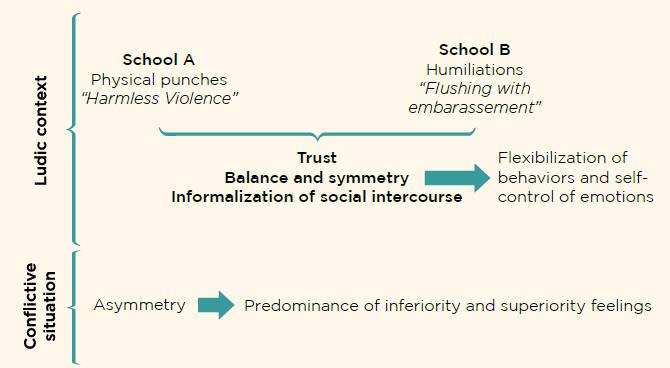

Both groups are part of school classes that the principals of each institution call “problematic classes”, even if there are students who do not have that violent behavior, or share the same kind of bonds with those groups. When questioning the students of both groups about their ways of interacting, they admit that, although they could be “violent” in abstract terms, especially from a viewpoint external to the group, they do not perceive such ways of interacting as violent. They are used to interact with others in this way and, consequently, they consider it as part of their “codes”. While the use of physical force prevails among students of School A, humiliations are the rule in the case of School B. The diagram below displays the analytical framework that will be examined in the following sections:

“HARMLESS VIOLENCE”

In the morning shift, 4th year class in School A, almost every male student uses to punch each other as part of the game. Besides bustling around and throwing objects (school supplies, bags, chairs, bins) at each other, they have a sort of ritual consisting in pushing a partner against the wall to be punched by everyone. Originally, this practice took place on somebody’s birthday, but then, it was extended to every moment of the school period.

P: How do students interact with each other in general?

G: Good, I do not really know what to say… yes, we get along with each other, we all mess around, we get along with each other. We usually fight but as a game.

P: With what or why do you fight, for example?

G: We pester each other and then we punch, but always as a game.

P: Does it happen frequently?

G: Always, always, every day [he laughs].

P: How does it start? What do you say when you are playing?

G: As a game, I do not know what we say. It comes up for nothing, but we pester each other… For example, even if it’s not someone’s birthday, we say it’s some guy’s birthday and pum!, we all go and punch him. And every day, one or other is punched, or every day we all are hit.

P: And that is all right for you?

G: It doesn’t go too far; it stops in the messing around.16 (Gabriel, 4th morning shift - School A, own translation)

One of the first days at school we witnessed how Gabriel received one of those beatings because of his birthday.

When the bell rang for the break, I thanked them for the talking and started to gather my stuff to go. At that moment, the boys stood up and one said [Manuel] “It’s Gabriel’s birthday”. All the boys jumped from the benches and leaped on him, hold him against one of the classroom walls and started to kick him and slapped him. Gabriel said “don’t get out of line”. The group of girls that were standing in front looked at what the boys were doing and laughed. Other group of girls, at the back to the left, kept talking among themselves without paying attention to what was going on. I was surprised of the boys’ reaction. I told them to stop, they laughed and walk away from Gabriel who was still stooped and disheveled. “It’s his birthday, Teach”. The boys continued laughing and Gabriel said with a warning tone “you’ll see!”.17 (Field note, September 17th 2012, own translation)

According to Duschatzky and Corea (2002), these practices may be called situation rituals where group regulations are established among peers. These are different from the institutional rituals, which are characteristic of the school sphere.

Situation rituals are only valid within a determined symbolic territory; they are not established from intergenerational transmission but from peers’ transmission, i.e. intragenerational. They are fragile; they do not generate an experience transferrable to other situations, but fulfill the purpose of anticipating what may occur.18 (DUSCHATZKY; COREA, 2002, p. 34, own translation)

This type of rituals coexists with those of institutional order. At school, there are different situation rituals that develop within the interstices of its institutional logic. It may be said that they express ways of sociability that shape an identity with which the subgroup boundaries are marked.

The boys of 4th year (morning shift) play to punch each other, happening among friends, some of them punch more than others, everybody laughs (except the one that receives the punches), no one gets mad, and the situations “don’t go too far”, they remain within the “messing around” (joda, in Spanish) limits. This dynamic is possible because they are partners/friends, that is, there is certain reciprocity in their relationship. The situation changes if this behavior appears when students don’t know each other o when there is no familiarity. In that case, the same attitude is considered offensive.

These students admit that they exert violence, but of a different type.

There are some [people] that use violence as if they are killing each other, but something different is our harmless violence, just messing around. It’s like putting everything under the same umbrella.

P: For you, would there be like two different violences?

M: Sure, one is our harmless violence that we mess around with. And then, there is the violence with gunshots, where the guys kill each other.19

(Manuel, 4th year - morning shift, School A, own translation)

[…] going into a fight is already violence. To exchange blows, but depends…. Because you know you have to get into a fight when playing ball, that’s ok. Well, not fine, but they are biffs, you’ll end knocked down, but they are just biffs. Sometimes, maybe you go and play somewhere else and they go with sticks, metal bars, that is different, that’s violence…20

(Marcelo, 4th morning shift - School A, own translation)

Taking into consideration the native category of the interviewees, the “harmless violence” is that originated within their “messing around” and/or momentary conflicts that may emerge from the ludic context itself. On the contrary, the other type of violence that they perceive as such is when life is at risk. Death appears as the line that differentiates what the young boys categorize as properly “violent” from the violence they associate with the game and their everyday interactions.

G: I mean, it’s violent because we are throwing things and punching each other, but we take it as a game. The one who gets mad is a moron because we are all playing and, if you get cross; you sit down and wait to cool off because we are all playing. Here, no one gets cross because we all know that it’s a game, and if you get cross, we are going to beat you up, it’s useless getting cross because we all know it’s a game. Today you’ll get what is coming to you, but tomorrow is someone else’s turn, and you are going to punch him. Last Monday, they gave me a beating because it was my birthday on Sunday. […] That day they beat me really hard, but I didn’t say anything because I knew that when it’s someone else’s birthday… For example, when it was Marcelo’s birthday, I killed him; I let him have it and don’t forget it for a long time. And that is the same with everyone, maybe it’s no one’s birthday and you are in for it too, like me, or Marcelo some other time, everybody. We’ve all been beaten up but we’re just playing.

P: What are the codes of this game?

G: It happens always at fights, when we play, but not with a closed fist because you receive a punch and it hurts. Then, everything else is valid; except pulling each other hairs, pinching, nothing of all that crap. Then, blows with open hand, slaps, kicks, things like that, they’re okay.21

(Gabriel, 4th morning shift - School A, own translation)

To include punches as part of the game, there should be a certain balance and self-regulation among those participating. Male students know each other; they are part of the same group (course) and accept that practice since they participate in the game. The symmetric balance lies in that there is a rotation of the beating up. Thus, the one who receives the punches cannot get mad, he has to “take the blow”, because he knows that later someone else will be in his place. He can get angry, but only momentarily, nothing else is tolerated. Eventually, he has to cool off, and return to the game when the anger has passed. If the anger goes on, the balance may be broken, and a fight would start. These are some of the rules of self-regulation which help to maintain the symmetric balance. Also, there are certain codes that regulate the use of the physical force: It must be for short periods of time, then it has to pass to another partner, and certain blows are banned.

Unlike the group of students from School B, at School A, students have personal experiences of having used the physical force both within the school and outside of it. In fact, these students told us “Who of our age hasn’t got into a fight some time?”. This could be one of the reasons why this kind of behavior is not perceived as violent.

“FLUSHING WITH EMBARRASSMENT”

With respect to school B, there was a similar sociability among a group of boys of 5th year (morning shift). They called themselves as the bullying guys. In contrast to the students from School A, they did not assault, but mocked constantly each other. In this context, we identified a strong code of reciprocal humiliations.

H: We mess a lot with each other. We make us flush with embarrassment.

S: We mortify each other.

P: Sorry, that’s only among you?

H: Flushing with embarrassment is among us […]

P: What’s that of flushing with embarrassment?

H: It’s awful, you sweat all over, those embarrassments are awful!!!

S: We have a friend who is fat and freckled [They both laugh]. And he is redheaded, so we drive him crazy.

H: And then, he is in love with a girl who doesn’t pay attention to him. We pick on the girl. We make him flush with embarrassment, it’s awful. It’s not nice. You feel bad. But it’s okay, we laugh our ass off. Then, they do it to me, to him. His girlfriend… [Laughters]

S: And that’s all day long.

P: But, how do you take it?

S: It’s like this, twelve of us mock one.

H: And the, twelve mock another one, it’s like that. No one stands up for the other. It’s like that, twelve mock one, and then that one…

S: That one joins with another, and they mock someone else.

P: And what happens when it’s your turn?

H: You have to put up with it.

S: Yes, but you also laugh.

H: You laugh your ass out. You sweat, but you laugh your ass out.22

(Héctor, 5th Year, morning shift - School B; Silvio, 5th Year, morning shift - School B, own translation)

The fun is making “flush with embarrassment” some member of the group, either among them or in front of some partners from outside the group. The game lies in all of them shaming or humiliating one who has any weak point. As Mutchinick (2013) stated in her study about humiliations among secondary school students, the presence of onlookers is relevant because it is important to show a devaluated image of the humiliated person in front of others.

The humiliation situation implies an inferiorization of the person who suffers it. However, the symmetry is reestablished when the humiliation finishes and the humiliated becomes the one who humiliates another partner. Possibly, in front of the observers, his image may be tarnished, but within the group, it stays intact, and the balance remains. As in School A, there is a symmetric balance and self-regulation among those who are part of the game.

Everybody mocks one, but there is a rotation. Nobody can get mad and they have to put up with it, even though it bothers them because it could be their turn later. Also, the mocks are self-regulated: they last a short period of time, and then, they change to another partner, and there are certain topics that are off limits (for example, the father of one of the boys had died and no jokes were allowed about it).

We observed that practice in School B too. One Friday, during the last period of the morning shift, we went to the buffet, and met some of the members of this group:

When we got inside, some of them said hello and I greeted back. They told me that they were out because they had finished their classes earlier that day. When we were at the counter waiting for the order, Silvio called me and said “Teach, do you remember I told you about one of us that haven’t done it yet, well, that’s him” [pointing at Mauro]. Everybody roared with laughter except Mauro [he had a serious and surprised face] who was sitting next to Silvio. Mauro told something to Silvio, that I couldn’t hear because of the noise. Then, he started to punch Silvio “friendlily”. I said “Don’t be mean!”, and the boys laugh again. Another boy said “Mauri, go to a whorehouse and you get it off”. Mauro stayed silent and said to Silvio with a warning tone “you’ll see!” I took what I had bought and I left the place with my partner.23

(Friday, October 5th 2012, own translation)

Silvio and Héctor told us not only how they mock Mauro but also, they did it publicly in front of us, who were observers outside the group. Clearly, the situation was uncomfortable for Mauro, who barely smiled and stayed almost all the time with a serious and ashamed face. However, at that moment, he did not show signs of irritation that could lead him to scold his partners.

This situation was mentioned again during the focus group we conducted with the entire 5th year group. Before the formal beginning of the interview, while they were sitting, the boys started to say aloud to us the derogatory nicknames with which they identify each of the members of the group. As Machado Pais states (2018, p. 923, own translation), “nicknames are creative acts generated by the critical observation of behaviors and physiognomic features of those with who people interact daily”.24 They are part of everyday symbology at school, and they may emerge ludically or violently. These students’ nicknames had certain acceptance within the group, which many times implied resignation because although they were stigmatizing, they were said in an intimate and affective context:

P: Here, you can say whatever you want, no one is being judged. The idea is chatting among us…

Lautaro: He is a Jew [with reference to Héctor]. This is confidential, right?

P: You can say whatever you want here…

Luciano: [laughing] He is stinky [with reference to Gaspar] and he is a burnt peanut [with reference to Mauro]

Gaspar: [with reference to Mauro] and he has a bleeding ass.

P: Oh, so we’ve started already…

Silvio: And he, [He points at Mauro, chokes with a cookie and says] he is a virgin, do you remember the one I told you about. [Everybody laughs. Mauro does not laugh and looks like he didn’t like the comment]

Héctor: [repeats Silvio’s line while laughing and pouring soda] “The one I told you about…”

Lautaro: He was [Mauro agrees raising his finger]

Everybody: Go, Mauri!!!! [Shouts and laughter]

Nano: Now he is a little less virgin

P: Did you help him?

Everybody: No [They start talking all at once again and it’s impossible to understand]

P: Let’s talk one by one because it’s impossible to understand. It’s not necessary to raise your hand, but let’s try to be organized so I can understand later.

Mauro: [while I’m talking, he points at Silvio and says to Hernán] “The one I told you about”, so he humiliated me before, how clever huh! [He said ironically]25

(FG, 5th year, morning shift, School B, own translation)

Again, Mauro’s episode came up and he, himself, referred to the humiliation. The comments about each other upset them, but they regulate that feeling by restraining it within the ludic context. The discomfort that they feel when it is their turn, is emotionally compensated by the humiliation they inflict on others. Something similar occurs with students of School A. The blows hurt, they even accept the bruises caused by the punches; however, they tolerate them as part of their sociability.

Many times, they said that they did it as part of their relational code and, for that reason, it did not bother them. But they also admitted that it hurt, even if they tolerated it and put up with it because it was their turn. One of the strategies to overcome humiliation is counter humiliation.

Nano: If someone from the head office sees how we treat each other and thinks that we are going to treat everybody like that, yes, he is going to say that we are bullying. Because, I mean, maybe we pick on each other but it’s because we know it doesn’t bother us.

Héctor: No, because we know there are certain codes, let’s say. We know that I say something to him [points at Silvio] about his girlfriend, and it’s not going to bother him because he knows it’s a lie. But someone else… [Luciano looks at Lautaro and makes a gesture of “more or less” with his hand, they laugh and also does Héctor]

P: More or less, then…

Silvio: What he is saying is that if he tells me that comment, I’m not going to get mad at him because is part of being friends.

Luciano: Of a familiar relation

Lautaro: Hey, at ten to the hour let’s take a break so G can go to clean his armpits because if not… [Héctor and Luciano say something to each other in a low voice and laugh]

P: [I ask G] Does it bother you, for example, what they say about your odor?

Gaspar: I mean… It’s accepted [Everybody roars with laughter except Gaspar who looks at them] I put up with it.

P: What are you laughing at?

Gaspar: [Looks at Luciano and Héctor and says] Stop it!

Nano: Actually, it bothers me, not him [with reference to the smell. Nano is sitting next to him]

Gaspar: It’s ok, I put up with it. They are messing around.

Nano: Maybe it bothers him to look bad in front of a girl or something, but okay, it’s part of the joke.

Gaspar: [Luciano and Héctor are still laughing. Gaspar looks at them and says with a more emphatic tone] Stop it! [Luciano makes the gesture of stopping, Héctor tells him something and punches him in the legs, Gaspar also punches Luciano “ludically” in the arm].

Lautaro: There is something else we mess around with [he smiles]

Héctor: No, stop!

P: Do you put up with those “jokes” or they provoke punches?

Luciano: Yes, with the bad body odor, yes.

[…]

Silvio: Anyway, when something bothers me, I give a tough answer.

Nano: Because we are not all here today, there are some missing [with reference to the students of 6th year who are part of the group, and to one of the partners that did not participate because he didn´t bring the authorization]

Lautaro: Each of us has a mock in particular that mortifies.

Héctor: Sure, everybody.

Silvio: For example, they start… they are all telling me cuckolded, cuckolded, cuckolded and I go for the jugular.

Héctor: He and his brother are the worst [Silvio’s brother is in 6th year]

Silvio: Yeah, you go without mercy to kill.

[…]

P: For example, the way you mock each other, do you see it as violent?

Silvio: Among us, no.

Héctor: If it is someone else who sees it, yes.26

(FG 1, 5th year, morning shift, School B, own translation)

Even though they do not perceive the humiliations among them as “violent”, they are aware that this kind of behavior may be seen as “violent” by other partners.

P: Some of what you consider violent, does it happen here at school?

L: Yes, but not physical, eh… not an assault. But maybe the violence of mocking, yes, and may be, our group is the one who does it the most. We are those who mock the most, but we know when to stop. When we notice that… “stop because you are hurting him”, we stop; or if a friend does not stop and he is hurting him, or I don’t stop, we tell him o they tell me to stop and you do it…27

(Luciano, 5th year, morning shift, School B, own translation)

S: If you are part of the group, you don’t see it as violent, because if I do this to him [He softly punches him with his hand], and someone from the outside comes and watches it, he’s going to say that I’m punching him in the face …28

(Silvio, 5th year, morning shift, School B, own translation)

Within this group of students, they admitted that there were two members that “have no limits” (Lautaro and Luciano). They do not self-regulate according to the rules agreed by the group. Even though they are not expelled from the group, their friends said that when they did not agree with their behavior, they let them on their own.

CONCLUSIONS

With respect to the ways of sociability of the two groups of students under study, trust is a catalyst when interpreting the “violent” nature of a situation. Based on trust, each student figures out that those who use physical force or mock others do it without the intention of hurting or causing harm; in turn, they assume that those who receive blows or are mocked will not feel hurt due to the ludic context in which they are inflicted.

Unlike the considerations of Machado da Silva (2004) regarding the increase of interpersonal mistrust in contexts of violent sociabilities, in our study, the use of violence as a ritualized practice between students is possible because of their trust. In the category violent sociability coined by the Brazilian researcher abovementioned as well as in Viscardi (2002), violence (understood only as the use of physical force) is an ordering principle of practices in a hierarchical order.

In this work, we described how violent sociability of young students takes place under a symmetrical and balanced logic in which the boy who punches or mocks others does not seek to dominate or feel superior. Here lies the difference between practices that can seem similar, but in a case expressed a conflict, and in another is part of a ludic context. Conflict supposes a confrontation where some people seek to position above others in a hierarchical logic. As Simmel (2002) claimed, sociability implies a reciprocal interaction in which someone’s satisfaction cannot be obtained without (or at the expense of) other’s satisfaction. Thus “the joy of the individual fully depends on the joy of others and, in principle, nobody can be satisfied at the expense of others’ very opposed feelings”29 (SIMMEL, 2002, p. 88, own translation). We can say that there should be a balance between the personal and collective spheres.

The sociability in each of these groups gives satisfaction to their members in terms of enjoyment, diminishing the rigidity of self-control demanded by school life. This ludic way of interacting puts them in an underworld within the school context where they can relax moderately. Even though they will be sanctioned when the game is over as they were many times before by school authorities who demand a greater self- restraint. Considering these young students’ relations, we wonder which non-punitive institutional strategies are or can be implemented at schools to improve the interaction among them (SILVA, 2018).

Elias and Dunning (1992) claimed that emotional stimulation has a main role in leisure sociability. To challenge the socially accepted limit of de-routinization stimulates the decrease of self-control boundaries. In this respect, these authors said:

[…] to play with fire, to take this risk, seems to increase the pleasant tension and, in that regard, the enjoyment of leisure-type gemeinschften. To approach the socially accepted limit and, sometimes, go beyond it; in other words, to break social taboos together with others, probably spices up this type of meetings.30 (ELIAS; DUNNING, 1992, p. 154, own translation)

This is one of the elements involved in the understanding of the reasons why, in their intersubjective relationships, young students go over the edge with respect to what is allowed in school life. According to other authors (DI LEO, 2010; FARAH NETO; MELO; ABRAMOVAY, 2012; GARCÍA BASTÁN, 2016; MEJÍA HERNÁNDEZ, 2017; NOEL, 2009; PAULÍN et al., 2015), teachers usually perceive the interactions of the young as uncivil behaviors, or typify certain situations as “violent”, while students consider them as one of the many ways of interacting. It would be interesting to build an intergenerational consensus among all actors of the educational community with respect to the meanings of the young’s practices at school. If cohabitation agreements and school councils invite to participate, they may become a fruitful space to generate such exchanges and to consolidate the quality of bonds at school.

In our research work, we found out that the perceptions of the students about violence are associated, to a larger extent, with the quality of the bonds forged in peer relations, and with the contexts in which they are developed; rather than with the type of practice itself or the a priori conception about it. Bonds based on trust are a subjective support that reassures the young to direct their actions to their peers (DI NAPOLI, 2019).

In this study, we observed that the decrease of self-control barriers in the sociability among the students does not imply its complete suppression. In fact, to be part of the game and to benefit from the more relaxed interaction, each one’s behaviors must be subjected to certain patterns of affective control.

Based on Elias and Scotson’s study (2016) on the relation between “the established and the outsiders”, we claim that the gratification felt when participating of a group is a just retribution for the personal sacrifice implied in the submission to the group rules. The self-restraint in these behaviors provides a context of stability to this way of sociability. Those young who do not maintain self-control, because they get angry or punch or mock the others in excess, are reprimanded by the group taking the risk of being separated from the game.

In terms of Elias, we may conclude that the bonds formed in these two groups of students make possible an informalization context in the social intercourse that implies a two-way process: the relaxation of behaviors, but simultaneously, the self-control of emotions (ELIAS, 2009, 2011). The “codes” forged within each group enable them, on the one hand, to behave in a more liberalized way as they can perform actions that would be banned in other contexts; and on the other hand, to have the adequate self-control to tolerate these behaviors from the other partners without reacting impulsively, taking the risk of breaking the bond.

texto em

texto em