1 Introduction

The debacle of the COVID-19 pandemic imposed several challenges to humankind beyond health issues. Worldwide, the pandemic has significantly impacted social and economic life, requiring measures such as quarantine, social distancing, and isolation of infected populations (ANDERSON et al., 2020).

Regarding Education, according to United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization – Unesco (2020), around the World, national-wide school closures has been impacting the majority of the student population and localized closures are affecting millions of additional learners. In this context, using online tools, such as online live classrooms, online on-demand teaching, TV video learning, and other methods for online teaching could be a successful mechanism to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Education (ZHOU, et al., 2020).

E-learning is the learning supported by digital electronic tools and media in which the use of Internet technologies provides a wide range of solutions to enhance knowledge and performance (BASAK; WOTTO; BELANGER, 2018). In general, the adoption and integration of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) into teaching and learning environment may provide more opportunities for teachers and students to work better in a globalized digital age, improving the quality of teaching and learning in the classroom (LAWRENCE; TAR, 2018). The application on e-learning may reduce costs, provide advantages for learners (such as its availability anywhere and anytime and ease of use), and allows facilitate interaction (ALMAIAH; AL-KHASAWNEH; ALTHUNIBAT, 2020). In a COVID-19 paradigm, e-learning may be a useful instrument to provide Education without physical contact in a classroom.

Regardless of the benefits of e-learning and other ICT applications in Education, their adoption is not automatic. An extensive body of literature has dealt with the factors associated with this issue by focusing on students’ and teachers’ adoption of technology (SCHERER; SIDDIQ; TONDEUR, 2019). Some of the reasons for the e-learning adoption are students facing technological difficulty, unavailability of technical staff and lack support of facilities, internet connection, reduced interactivity, weak teachers’ IT skills and knowledge, teachers’ lack of technology acceptance, and lack of infrastructure such as hardware, software, facilities, and network capabilities (ALMAIAH; AL-KHASAWNEH; ALTHUNIBAT, 2020). Consequently, any public policy strategy aiming at implementing e-learning to mitigate the impact of a pandemic should consider the determinants of acceptance of ICT in Education.

However, countries with a higher education gap probably face more difficulties in effectively implementing e-learning due to different culture, context, and readiness (ALMAIAH; AL-KHASAWNEH; ALTHUNIBAT, 2020), requiring a specific analysis lens. As the adoption of e-learning does not have a standard form applicable to any country or region, research from the perspective of developing countries is essential, as it enables the identification of factors for the adoption of e-learning tools (VALENCIA-ARIAS; CHALELA-NAFFAH; BERMÚDEZ-HERNÁNDEZ, 2019). Specially during the Pandemic, when schools have been putting effort on using e-learning to intermediate distance Education, factors such as lack of skills and practice of teachers, staff, and families besides the scarcity of infrastructure may compromise e-learning benefits and even enhance educational inequalities (DIAS; PINTO, 2020) in developing countries.

The perspective of the so-called developing countries is the main focus of both research and practice in the ICT for development – ICT4D field (WALSHAM, 2017). The ICT4D field refers to development thinking and practice addressing the enabling role of ICT on development relation (SEIN et al., 2019).

Grounding on the ICT4D field and on Information System (IS) acceptance and resistance fields, which investigate the determinants of technology acceptance and usage, this article aims at understanding how research on acceptance and resistance to e-learning in developing countries is undertaken. To do so, it performs a systematic literature review of articles from 2007 to 2019. This review considers e-learning as the use of any digital device or system to mediate the learning process. With a strict searching method, it has selected, analyzed, and categorized 44 studies.

In what follows, this article reviews the theoretical background, discussing the technological acceptance and resistance theories, the adoption and usage of e-learning context, and shedding light on how the ICT4D field may approach e-learning adoption. Afterward, it presents the researc methods, followed by the results and discussion of findings. Finally, a conclusion section ends this article.

2 Theoretical background

This section presents a discussion of the technology acceptance and resistance theories. Then, it focuses on the adoption and usage of the e-learning context and the ICT4D field approach.

2.1 Technological Acceptance and Resistance Theories

At the very beginning of technology entering users’ everyday lives, researchers developed theories and models to understand why the technology is accepted or rejected due to the finding that information technology is underutilized in many organizations. (GRANIĆ; MARANGUNIĆ, 2019). ICT usage may emphasize behaviors toward the ‘acceptance’ of technologies or the ‘resistance’ to use them in the Information Systems field. In this sense, we can affirm that acceptance and resistance are the two sides of the motivation coin towards IS usage behavior. If acceptance refers to the conditions that motivate individuals to adopt a technology, resistance refers to those factors that motivate individuals to resist its adoption. Hereupon, one can consider acceptance and resistance theories as applications of motivation models to explain the behavioral change.

The expectancy theory is prominent among motivation models and seems to fit in IS acceptance and resistance approaches. If motivation explains behavioral change, this theory considers that people consciously choose courses of action based upon perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs related to their desires to enhance pleasure and avoid pain (ISAAC; ZERBE; PITT, 2001). Then, the motivation to engage in a behavior (which can be resistance or adoption) is a function of the expectations that an outcome may be attained, and the degree of value placed on an outcome in the person (ISAAC; ZERBE; PITT, 2001). Hence, one feels motivated when three conditions are perceived (ISAAC; ZERBE; PITT, 2001):

The personal expenditure of effort will result in an acceptable level of performance.

The performance level achieved will result in a specific outcome for the individual

The outcome attained is personally valuable.

The following presents IS acceptance and resistance approaches, which deal with individuals’ motivation to engage in or avoid, respectively, IS usage behavior.

2.2 Acceptance

Since the mid-eighties, researchers have been proposing a plethora of theoretical models to examine technology acceptance and usage, including the Theory of Reasoned Action, the Theory of Planned Behavior, the Model of Personal Computer Utilization, Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), and TAM’s extension (such as TAM2, TAM3, and UTAUT) (DWIVEDI et al., 2019; LAI, 2017).

One of the more prominent acceptance models, TAM, is based on the mediating role of perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness in the relationship between systems characteristics (external variables), attitude toward using, and actual system use. According to Davis (1986, p. 21), “external variables encompass all variables not explicitly represented in the model” (i.e., perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and usage variables), including “demographic or personality characteristics of the actor, the nature of the particular behavior under consideration, and characteristics of referents.” TAM has been widely used to study the adoption of various technologies and has arguably become the most influential theory (GRANIĆ; MARANGUNIĆ, 2019). TAM’s prominence is mainly due to its transferability to various contexts and samples, its potential to explain variance in the intention to or actual use of technology, and its simplicity of specification within structural equation modeling frameworks (SCHERER; SIDDIQ; TONDEUR, 2019).

From its initial design, TAM has received modifications: current attributes of the technology acceptance construct, besides Perceived ease of use and Perceived usefulness, include Attitudes toward technology, Technology self-efficacy, Subjective norms and Facilitating conditions (SCHERER; SIDDIQ; TONDEUR, 2019). To consolidate knowledge from modifications and divergent models derived from TAM, VENKATESH et al. (2003) performed an endeavor of reviewing user acceptance models and formulated the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). The model conveys four core variables (performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions) and four moderating variables (gender, age, experience, and voluntariness of use) (VENKATESH et al., 2003).

2.3 Resistance

The resistance perspective focuses on explaining why and how individuals resist IS implementations and aims to guide organizations on how to manage employees’ perceptions and behaviors related to threats, trust, relationships between actors, and management (LAUMER; ECKHARDT, 2011). Compared to the acceptance theory, much less attention to why individuals resist or reject technologies and which factors inhibit or discourage usage in the IS field (LAUMER; ECKHARDT, 2011).

The resistance literature often suggests that user resistance is a reaction to changes and uncertainty, usually related to loss of power, lack of involvement in the change process, and reluctance to change. Lapointe and Rivard (2005), in their seminal work, indicate five basic and standard primitives (or dimensions) of resistance to IS implementation, at individual and unit levels: resistance behaviors, which may vary, for instance, from neutrality and apathy to extremely engaging in physically destructive behavior; the object of resistance; the perceived threats (by individuals due to the implementation); the initial conditions; and, the subject of resistance.

Kim and Kankanhalli (2009) have also significantly contributed to this literature. They have explained user resistance before a new IS implementation, integrating the technology acceptance and resistance literature with the status quo bias perspective, understanding psychological and decision-making mechanisms underlying the resistance. The resistance literature is more recent and less proliferated than its acceptance pair.

Finally, even though acceptance and resistance to IS have been treated as separate approaches, some researchers have been developing and testing models aiming at integrating them (e.g. ALTHUIZEN; 2018).

2.4 Adoption and usage of ICT in Education

Determinants to the adoption and usage of ICT in Education have been studied over the last years. Among these determinants are training and professional development opportunities, level of technical support, ICT infrastructure, proper curricula, available time, confidence, resistance to change, attitudes, and beliefs (SALAM et al., 2018). It is worth mentioning that these determinants comprehend from individual traits and preferences from a micro perspective to macro conditions, such as national regulations. All these conditions and their interplay matter when studying the ICT usage in Education and its effects.

Within the technology acceptance perspective, many studies in Education have been produced, most of them applying TAM to e-learning (GRANIĆ; MARANGUNIĆ, 2019). According to Granić and Marangunić (2019), TAM and its variations represent a credible model for facilitating the assessment of diverse learning technologies, and its core constructs are robust in learning settings. The TAM’s predominance in Education seems not to differ from other sectors. The model is pervasive across sectors and ICT types. Taking the central constructs perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness, it is coherent with expectancy theory to assume that user’s perception of how easy it is to use technology and how useful this is in achieving practical goals are relevant on motivating the user to adopt this technology, not only in Education but in all sectors.

Regarding external factors (those excluding perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness), the most used ones in TAM models for e-learning are self-efficacy, subjective norm, enjoyment, computer anxiety, and experience (ABDULLAH; WARD, 2016). Also, these factors seem to matter for individual motivation in general, not only in Education.

Even though TAM is the most-used theory in ICT acceptance research in Education, some studies have used UTAUT as the ground theory (KAYALI; ALAARAJ, 2020). Some studies have applied UTAUT key constructs (performance expectancy; effort expectancy; social influence; and facilitating conditions) to evaluate e-learning adoption, such as the use of interactive whiteboards among teachers (ŠUMAK; ŠORGO, 2016), and the application of social media in research practices (GRUZD; STAVES; WILK, 2012).

Also, some studies approximate resistance perspective, but without necessarily using the IS resistance approach models and even using acceptance perspective elements. Torres, Evans and Schneider (2019) identify institutional-related barriers of institutional culture, faculty self-efficacy, and a lack of institutional support as the leading causes of implementation and adoption challenges in Education. Muqtadiroh et al. (2019), on the other hand, propose that perceived threat, perceived usefulness, perceived inequity, and behavior intention are resistance factors to ICT usage in Education.

Retaking the expectancy theory, resistance determinants as uncertainty about technology’s value, negative attitude, low self-efficacy, and lack of support are compatible with the constructs of perception of effort needed, performance level, and its outcomes in Education, which explains motivation (in this case, to resist to ICT in Education).

2.5 ICT4D and e-learning adoption

The adoption of ICT does not have a standard form that applies to any country or region, which makes research from the perspective of developing countries essential to identify specific factors for the adoption of e-learning tools (VALENCIA-ARIAS; CHALELA-NAFFAH; BERMÚDEZ-HERNÁNDEZ, 2019). In this sense, theories of technology diffusion created in developed countries should observe the context and particularities of developing countries to make sense when applied to them.

The ICT for development (ICT4D) field, which seeks to examine the development changes and its multitude of dimensions in developing countries brought about by the deployment and use of ICT and how it is enabled (SEIN et al., 2019), calls for theorizing in the context of developing countries. Also, this field aims to examine the relationship between the local context and ICT accounting for social, political, and economic issues (DE et al., 2018).

Previous research has already shown ICT failure in developing countries, related to factors such as low level of quality of infrastructure, low availability of ICT skills, complex power structures, and incongruence between the development context and the design and implementation of the ICT (CHIPIDZA; LEIDNER; 2019). As ICT usage in developing countries is more prone to failure due to specific barriers, understanding these determinants is crucial.

3 Research method

The review aimed to identify, assess and analyze representative academic literature on acceptance and resistance to e-learning in developing countries. For the review, a literature search was undertaken for one month (from March to April 2020). The following online bibliographic databases were consulted:

The following searching string was adopted:

(’Acceptance’ OR ’Resistance’ OR ’Adoption’) AND (‘E-learning’) AND (‘Developing countries’ OR ‘Developing country’)

The following exclusion criteria were applied:

Studies referring to ICT in Education in general, not strictly related to the use of a digital device or system to mediate the learning process;

Studies in which the geographical scope was not explicit and studied country was not in the list of developing countries of the United Nations;

Studies not related to acceptance or resistance.

The search was limited to publications written in English and was not limited to a specific time. The selected literature’s title, abstract, and text were screened to ensure adherence to the scope and not meeting exclusion criteria. Qualified publications were retained, lasting 71 for analysis. The following step comprised a detailed process of reading and analyzing the full text of the selected publications. The final selection in this review was composed of 44 studies.

Publications were categorized according to (i) educational stage; (ii) user, (iii) approach (TAM, UTAUT, critical success factor, and others); (iv) country (region and income group); and (v) if studies highlight specificities for developing countries (yes or not). In approach categorization, studies were assigned for TAM or UTAUT, even in cases where the model was the extension or a direct application of the constructs of one (or the two) of them.

4 Results

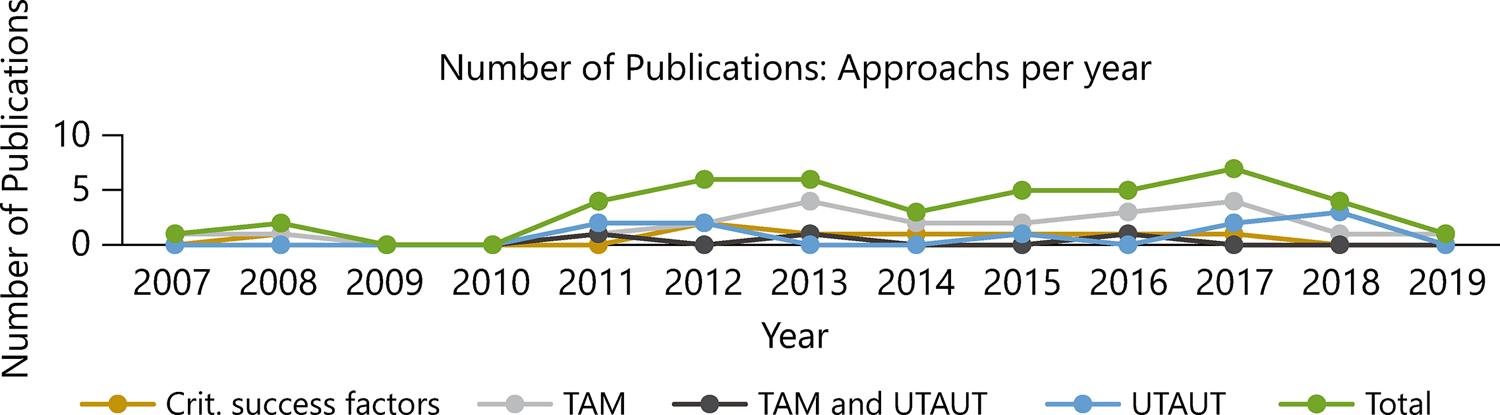

Table 1 in the appendix presents articles per categorization. Studies were about 25 countries, three of them conveying more than one country: Saudi Arabia (5), Pakistan (3), Lebanon (3), Ghana (2), South Africa (2), Jordan (2), Sri Lanka (2), Tanzania (2), Taiwan (2), Libya (2), Malaysia (2), Liberia (1), Thailand (1), Indonesia (1), Brazil (1), United Arab Emirates (1), Iraq (1), Burkina Faso (1), Peru (1), Thailand (1), Qatar (1), Tunisia (1), Colombia (1), Egypt (1), Oman (1). As Graph 1 presents, studies on the theme started being published with more frequency in 2011, with a decline in 2018.

Table1 Results

| Article | Pub. Year | Educational Stage | User | E-learning Technology/Tool and e-learning system | Approach* | Country | Income group** | Specificities for developing countries? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdel-Wahab (2008) | 2008 | Higher Education | Students | system | TAM | Egypt | Lower middle income | Yes |

| Abu-Shanab (2014) | 2014 | Primary or Secondary Education | Students&Teachers | System | TAM | Jordan | Upper middle income | No |

| Al-Adwan et al. (2013) | 2013 | Higher Education | Students | system | TAM | Jordan | Upper middle income | No |

| Al-Azawei et al. (2017) | 2017 | Higher Education | Students | System | TAM | Iraq | Upper middle income | No |

| Al-Gahtan (2016) | 2016 | Higher Education | - | - | TAM | Saudi Arabia | High income | No |

| Almazroi et al. (2016) | 2016 | Higher Education | Students | tools | TAM | Saudi Arabia | High income | No |

| Andersson (2008) | 2008 | Higher Education | Students&Staff | System | Crit. success factors | Sri Lanka | Upper middle income | Yes |

| Bellaaj et al. (2015) | 2015 | Higher Education | Students | System | UTAUT | Saudi Arabia | High income | No |

| Bhatiasevi (2011) | 2011 | Higher Education | Students | System | TAM | Thailand | Upper middle income | No |

| Bhuasiri et al. (2012) | 2012 | - | - | - | Crit. success factors | Various (experts) | - | Yes |

| Boateng (2016) | 2016 | Higher Education | Students | system | TAM | Ghana | Lower middle income | No |

| Chen (2011) | 2011 | Higher Education | Students | system | UTAUT | Taiwan | High income | No |

| El-Masri & Tarhini (2017) | 2017 | Higher Education | Students | system | UTAUT | Qatar | High income | Yes |

| Elkaseh et al. (2015) | 2015 | Higher Education | Students&Teachers | System | TAM | Libya | Upper middle income | No |

| Esterhuyse & Scholtz (2015) | 2017 | - | - | - | Crit. success factors | South Africa | Upper middle income | Yes |

| Hussein (2007) | 2007 | Higher Education | Students | System | TAM | Indonesia | Lower middle income | No |

| Ibrahim et al. (2017) | 2017 | Higher Education | Students | system | TAM | Malaysia | Upper middle income | No |

| Ismail et al. (2013) | 2013 | Primary or Secondary Education | Teachers | tools | Crit. success factors | Malaysia | Upper middle income | No |

| Kanwal & Rehman (2014) | 2014 | Higher Education | - | System | TAM | Pakistan | Lower middle income | No |

| Kanwal & Rehman (2017) | 2017 | Higher Education | Students | system | TAM | Pakistan | Lower middle income | No |

| Kisanga & Ireson (2015) | 2015 | Higher Education | Teachers | System | Crit. success factors | Tanzania | Low income | Yes |

| Liebenberg et al. (2018) | 2018 | Higher Education | Students | both | UTAUT | South Africa | Upper middle income | Yes |

| Maldonado et al. (2011) | 2011 | Primary or Secondary Education | Students | system | UTAUT | Peru | Upper middle income | Yes |

| Mwakyusa & Mwalyagile (2016) | 2016 | - | - | - | Crit. success factors | Tanzania | Low income | Yes |

| Nassuora (2012) | 2012 | Higher Education | Students | tools | UTAUT | Saudi Arabia | High income | No |

| Okazaki & Renda dos Santos (2012) | 2012 | Higher Education | Teachers | System | TAM | Brazil | Upper middle income | No |

| Ouedraogo (2017) | 2017 | Higher Education | Teachers | tools | UTAUT | Burkina Faso | Low income | No |

| Qbal & Qureshi (2012) | 2012 | Primary or Secondary Education | Teachers | System | UTAUT | Pakistan | Lower middle income | No |

| Rhema & Miliszewska (2014) | 2014 | Higher Education | Students | System | Crit. success factors | Libya | Upper middle income | No |

| Rym et al. (2013) | 2013 | Primary or Secondary Education | - | - | TAM | Tunisia | Lower middle income | No |

| Sabraz Nawaz et al. (2015) | 2015 | Primary or Secondary Education | Teachers | System | TAM | Sri Lanka | Upper middle income | No |

| Salloum & Shaalan (2018) | 2018 | Higher Education | Students | System | UTAUT | Unit.ArabEmirates | High income | No |

| Sarrab et al. (2015) | 2015 | Higher Education | Students | tools | - | Oman | High income | No |

| Tagoe (2012) | 2012 | Higher Education | Students | System | TAM | Ghana | Lower middle income | No |

| Tajudeen et al. (2013) | 2013 | Higher Education | Students | tools | TAM and UTAUT | Malaysia/Nigeria | - | No |

| Tarhini et al. (2013) | 2013 | Higher Education | Students | system | TAM | Lebanon | Upper middle income | No |

| Tarhini et al. (2017) | 2017 | Higher Education | Students | system | TAM | Lebanon | Upper middle income | No |

| Tarhiniet et al. (2016) | 2016 | Higher Education | Students | System | TAM and UTAUT | Lebanon | Upper middle income | No |

| Teo et al. (2011) | 2011 | Higher Education | Students | system | TAM and UTAUT | Thailand | Upper middle income | No |

| Valencia-Arias et al. (2019) | 2019 | Higher Education | Students | tools | TAM | Colombia | Upper middle income | No |

| Vululleh (2018) | 2018 | Primary or Secondary Education | Students | - | TAM | Liberia | Low income | No |

| Wu & Liu (2013) | 2013 | Primary or Secondary Education | Teachers | system | TAM | Taiwan | High income | No |

| Xaymoungkhoun et al. (2012) | 2012 | Primary or Secondary Education | - | - | Crit. success factors | Various (experts) | - | Yes |

| Zalah (2018) | 2018 | Primary or Secondary Education | Teachers | system | UTAUT | Saudi Arabia | High income | No |

Source: Own elaboration (2021)

* Here, I have assigned TAM and-or UTAUT also for other models directly derived from TAM and-or UTAUT constructs

** World Bank list of economies (June 2019)

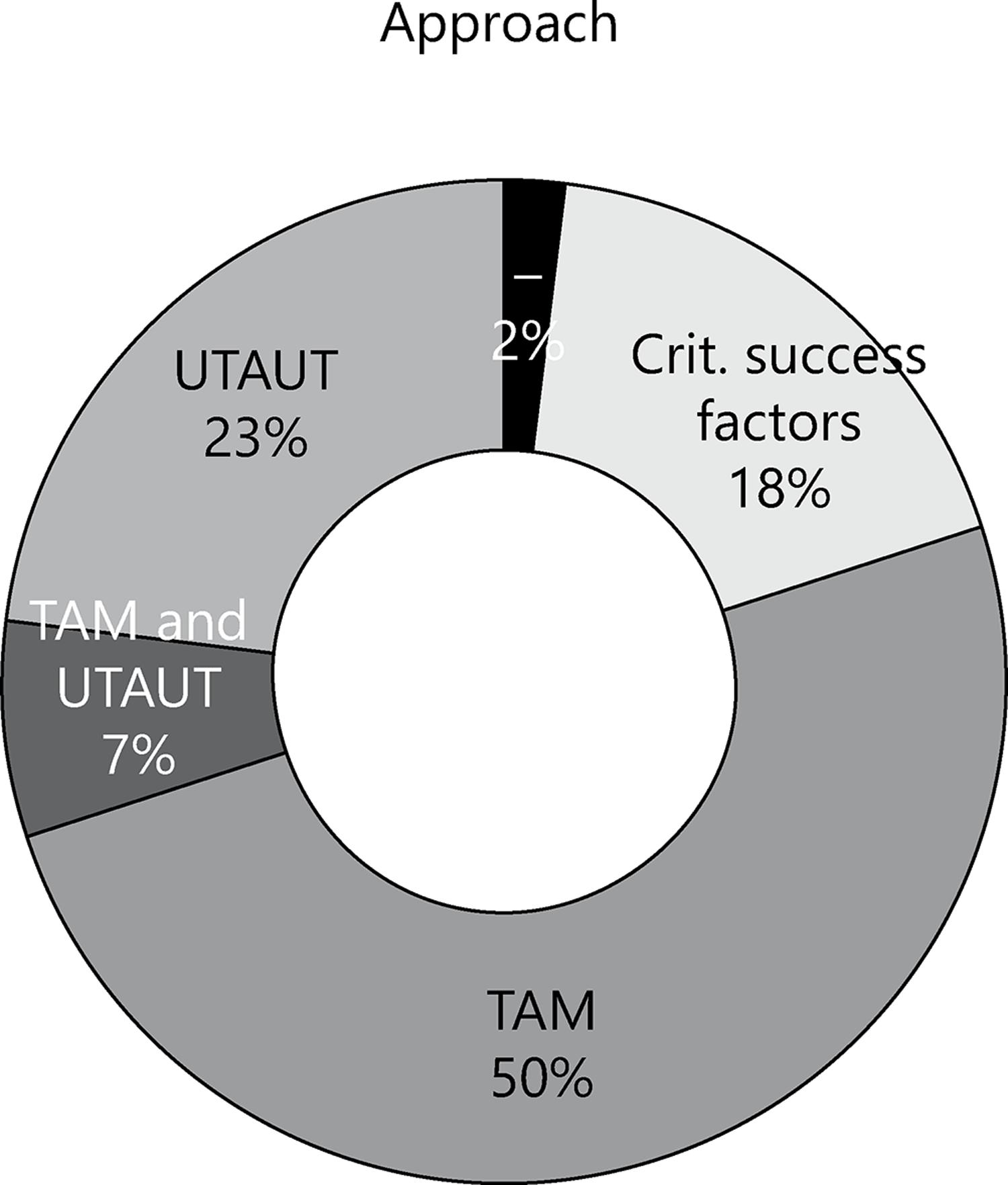

Results in Graph 2 show that most studies applied the TAM (or its extensions) framework, followed by UTAUT. Most works on TAM in developing countries follow the general pattern of e-learning acceptance studies, mainly using the TAM framework. Almost 20% applied a critical success factor perspective, which combines elements from acceptance and resistance. None of the reviewed studies used an explicit framework of resistance to adoption.

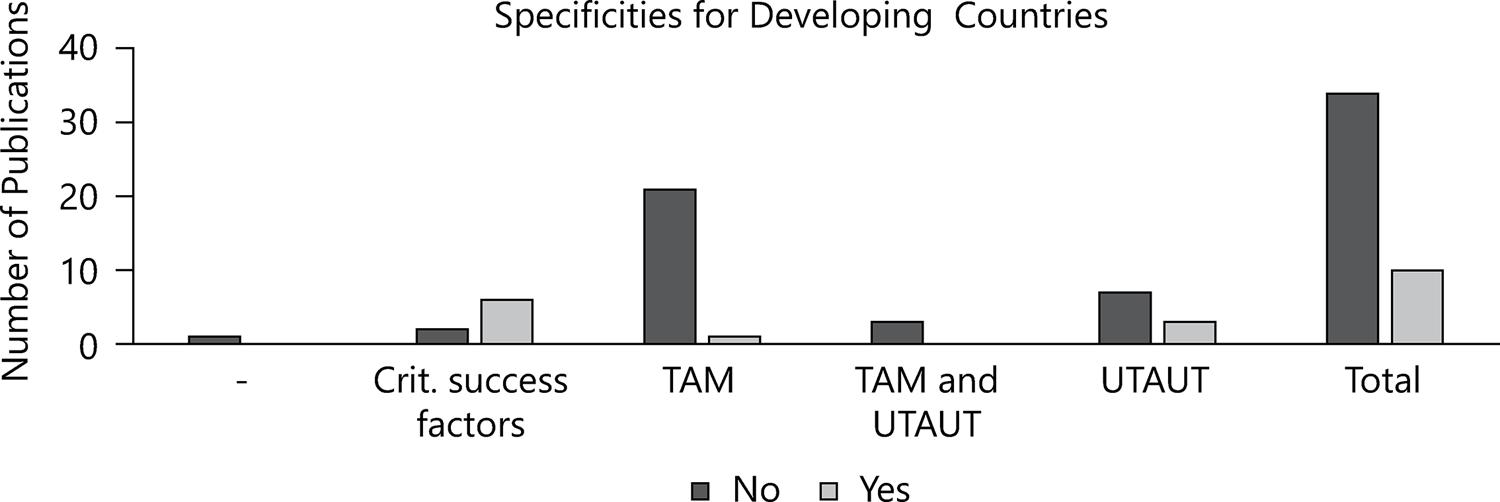

As Graph 3 demonstrates, most of the applications of TAM and UTAUT do not explore the specificities of developing countries in acceptance towards e-learning. By doing so, these studies limit themselves to test if TAM and UTAUT frameworks explain acceptance in developing countries. Although it is vital to test the external validity of these models across countries, not going beyond it reduces TAM and UTAUT’s potential to enlighten policy and initiatives to implement e-learning in developing countries. Some exceptions bring exciting insights. Abdel-Wahab (2008) recommends the sequential use of predecessor distance learning technologies from correspondence courses to radio, TV, CDROM, and internet when the infrastructure for e-learning is unavailable. Maldonado et al. (2011) argue that teachers, parents, and peers may influence students to use educational portals in cases of low technology diffusion and awareness in poor regions.

Notwithstanding, research on critical success factors commonly emphasizes developing countries’ specificities concerning barriers and determinants of adoption and usage of e-learning. Some of the frequently mentioned critical adoptions are technological infrastructures, including the availability of computers and internet access; ICT-competence among the educational stakeholders and basic technical knowledge and skills; existence of e-learning policy; organization management and social interaction; government support; teachers’ resistance to change (BHUASIRI et al., 2012; ESTERHUYSE; SCHOLTZ, 2015; MWAKYUSA; MWALYAGILE, 2016; XAYMOUNGKHOUN et al., 2012).

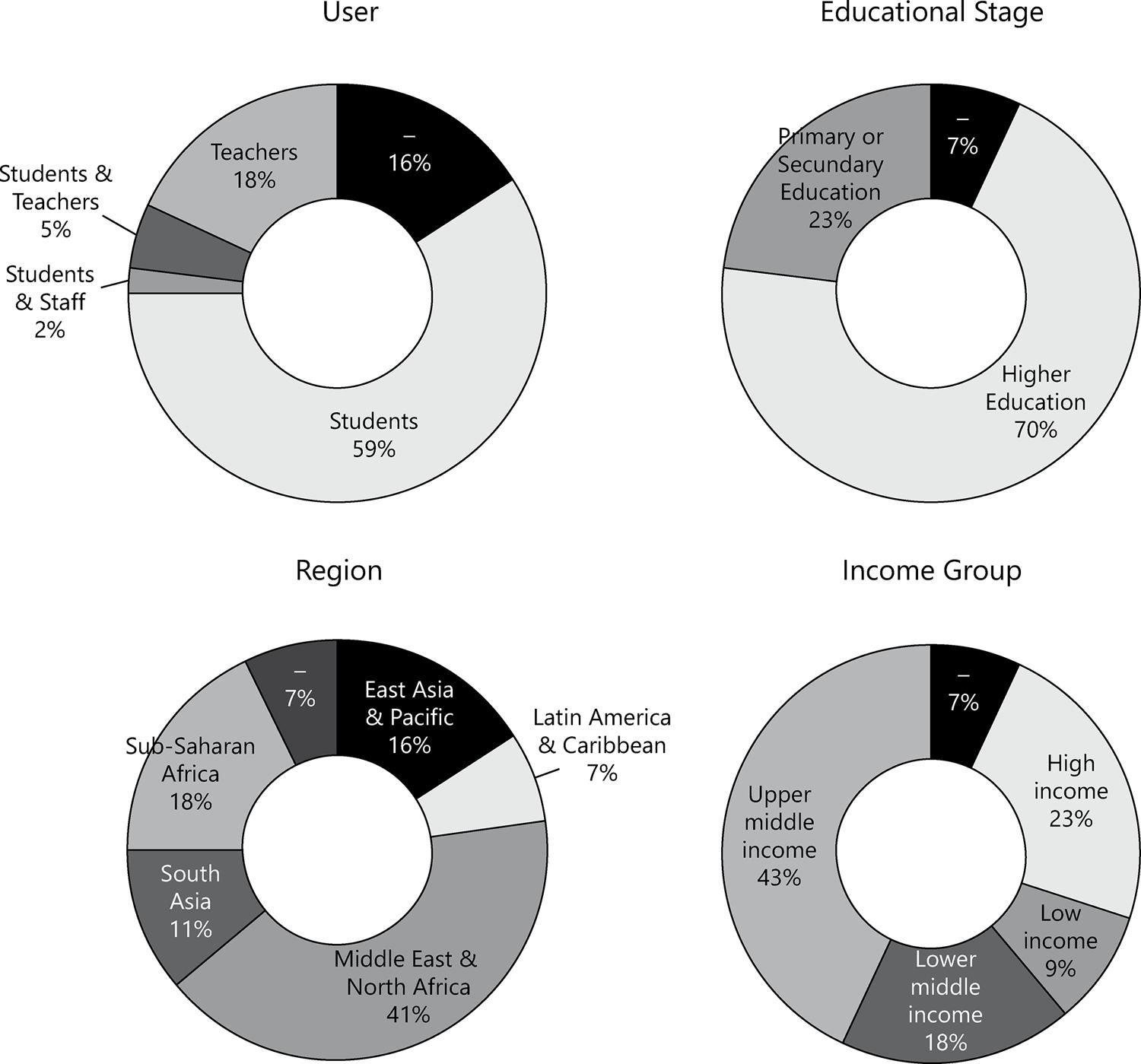

Regarding the users, there is a substantial concentration of studies on students. Only 18% of the studies focus exclusively on teachers, a portion slightly higher than studies that do not distinguish between users (16%). When it comes to the educational stage, there is a significant concentration on Higher Education (70%) in comparison to primary or secondary Education (23%). Also, most studies analyze countries with higher income levels within the developing countries (upper middle income (43%) and high income (23%), while low-income countries respond to only 9% of the reviewed articles. These information compose Graph 4.

5 Discussion

Results have shown the evolution of e-learning acceptance literature in developing countries in the last decade, mainly grounded on the TAM framework, with minor use of UTAUT and the critical success factors approach. However, the application of TAM and UTAUT models have been principally testing the robustness of the model in developing countries, without delineating which specificities of these countries must be considered to analyze acceptance. Through an ICT4D, which refers to the thinking and practice for the deployment of ICTs in developing countries with development purposes, the acceptance field can build a specific approach for developing countries. Authors such as Abdel-Wahab (2008) and Maldonado et al. (2011) demonstrate that it is possible to conciliate acceptance of consolidated frameworks and the specificities of developing countries.

In sum, although it is valuable and methodological feasible to undertake acceptance analysis on Education ICT in developing countries, most of the literature only evaluates whether it is valid to apply, in the developing countries, models that come from developed ones. However, if humankind is genuinely engaged in building a sustainably developed, it is vital to address each developing country’s particularities and challenges, including Education.

Little needs to be said about the centrality of Education in development and its enabling role in different aspects, such as per capita income, long-run growth, gender equality, and health. The United Nations has considered this pivotal role when defined “Quality Education” as a stand-alone Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 4) within the 17 ones as a means of achieving a better and more sustainable future (UN, 2015). The Education goal comprises targets to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality Education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

Inclusiveness, equitability, and opportunities are fundamental and necessary tenets of the quality Education constructs which underlie SDG 4. Each developing country has challenges and contexts to foster ICT usage in Education, effectively improving learning. These challenges and contexts are not only different when compared to developed countries. It also varies within the developing countries.

Then, without understanding and directing policies to the determinants of ICT usage in each developing country, the positive effects of ICT in Education may vary heterogeneously across countries, harming notably those less developed. It would mean that ICT could favor Education quality inequity worldwide, reducing opportunities and excluding most impoverished students and teachers.

Indeed, through the expectancy theory approach, we can conjecture how the challenge of ICT usage is higher in more impoverished schools. For instance, under the lack of infrastructure resources and connectivity, low digital culture and competencies, deficiency in process, and the availability of digital resources, students, professors, and staff may be unmotivated to use ICT in the learning process. It would happen because they understand that this use requires high effort (or even it is prohibitive) and that the ICT usage conversion in improved Education performance and outcomes is unreliable. The motivation may be scarce also because their schools have just other primary necessities than promoting ICT usage.

In fact, in multicultural and unequal countries, there are sensitive concerns about the challenges of access to digital artifacts and the articulation of digital learning and curriculum practices (IVENICKI, 2021). In Brazil, for instance, during the pandemic period, most students have not had access to digital learning to attend online courses (IVENICKI, 2021). Also, more than providing internet and infrastructure, lack of competencies, proper methods to insert technologies in a learning context and transferring competencies to virtual settings mediated by e-learning have shown decisive in transform ICT usage in Education outputs in more impoverished contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic period (OLIVEIRA; GOMES; BARCELLOS, 2020; PARREIRA; LEHMANN; OLIVEIRA, 2021).

Further, dealing with ICT usage barriers in developing countries is especially relevant considering the pos-COVID era. Due to the school closures and remote schooling, the learning deficit has harmed everyone, but mainly the least privileged students, who have been facing a more significant burden and which will require all public efforts (DIAS, 2021; GOMES; VÁZQUEZ-JUSTO; COSTA-LOBO, 2021). Besides learning deficits, pos-COVID era requires an imperative effort to recover Education in its multiple ends and goals: supporting educators, students, and families, with a specific focus on the underprivileged, counting on the participation of the social forces of community and society (GOMES; VÁZQUEZ-JUSTO; COSTA-LOBO, 2021).

E-learning usage will be a helpful tool within hybrid or on-site classes since the barriers are identified and tackled. The use of ICT in recent experiences has shown promising results in the developing world, mixing remote and on-site learning in the class return. (CASTIONI et al., 2021). ICT may be helpful since it comes with political, economic, and pedagogical conditions to empowering technological languages that facilitate dialogic teaching methods (HABOWSKI; CONTE; JACOBI, 2020).

Regarding the focus identified in the e-learning ICT usage in developing countries, the concentration of research on Higher Education seems not to dialogue with the primary educational challenges of developing countries: broadening access to Education and enhancing quality Education (KREMER; BRANNEN; GLENNERSTER, 2013). These challenges are in line with the “Quality Education” UN’s Sustainable Development Goal, and directly related to its target 4.1 (“By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary Education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes”) (UN, 2015). For e-learning acceptance literature to contribute to educational needs in developing countries, it is also vital to address analyses on basic Education. Additionally, the concentration on students restricts the analysis of the role of other essential stakeholders in e-learning adoption, such as teachers, principals, staff, and families.

Furthermore, the review has found a concentration of research on high and upper-middle-income countries. Most of the researchers of acceptance and resistance to e-learning within the developing countries are neglecting those countries with, comparatively, more barriers to the adoption of e-learning and higher educational needs.

6 Conclusion

This article, which aimed at reviewing the literature on acceptance and resistance to e-learning in developing countries, has selected, analyzed, and categorized 44 studies according to the following types (i) educational stage; (ii) user, (iii) approach (TAM, UTAUT, critical success factor, and others); (iv) country (region and income group); and (v) if studies highlight specificities for developing countries (yes or not).

Results have shown the evolvement of e-learning acceptance literature in developing countries in the last decade, mainly grounded on TAM Framework, with minor use of UTAUT and critical success factors perspective, which combines elements from acceptance and resistance. None of the reviewed studies used an explicit framework of resistance to adoption. Most of the applications of TAM and UTAUT do not explore the specificities of developing countries in the acceptance of e-learning. Consequently, its contribution reduced to build a theory of particularities of developing countries on this issue.

As the SDG agenda posits, the contribution of Education in building a sustainably developed world requires addressing inclusiveness, equitability, and opportunities in Education across all countries. For ICT usage to work as an inclusive and equitable tool to quality Education, it should provide equal opportunities in all schools. Doing that is only possible if researchers identify barriers and determinants for educational ICT usage in local contexts.

Indeed, some critical adoption factors in developing countries have already been found, such as technological infrastructures, ICT competence, basic technical knowledge and skills, lack of e-learning policy, and government support. It indicates that, in a COVID-19 paradigm in which the diffusion of e-learning could mitigate the impact of school closure, it is fundamental to design strategies and policies considering the specificities and particularities of developing countries.

Furthermore, the review has found a concentration of studies focusing on students, Higher Education, and countries with high levels of income between the developing countries. Then, the following gaps should be addressed by researchers to contribute to thinking and practice aiming at tackling the educational challenges in these countries with the contribution of e-learning: exploring the specificities of developing countries when applying consolidated acceptance frameworks; encompassing primary and secondary educational stages and all the relevant stakeholders of the adoption of e-learning in the analyses; and covering countries with lower levels of income.

Finally, from the results and discussion, the following gaps in e-learning acceptance and resistance in developing countries should be addressed by researchers:

Exploring the specificities of developing countries when applying consolidated acceptance frameworks.

Encompassing primary and secondary educational stages and all the relevant stakeholders of the adoption of e-learning in the analyses.

Covering countries with lower levels of income.

Besides these gaps, further work on acceptance and resistance in e-learning could consider using explicitly resistance frameworks. Therefore, they could disentangle tools and systems of e-learning and its relationship with acceptance and resistance, and also account for regional inequalities within each studied country.