Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educar em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0104-4060versão On-line ISSN 1984-0411

Educ. Rev. vol.40 Curitiba 2024 Epub 11-Nov-2024

https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-0411.94095

DOSSIER: Quality, learning and systemic assessment: discourses from international organizations for Latin American countries

Large-scale assessment and establishment of educational goals and indicators: uses and abuses of quantophrenia

PhD in Education, Universidade de São Paulo (USP); researcher, Fundação Carlos Chagas (FCC), São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; professor, Universidade de São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5942-9181

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5942-9181aUniversidade de São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; Fundação Carlos Chagas (FCC), São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. adbauer@fcc.org.br

This article seeks to problematize the emphasis given by Brazilian municipalities to quantitative aspects of student performance, measured by large-scale assessments, instead of the discussion about the learning process and the pedagogical meaning of data and the production of process indicators associated (or not) to achievement of learning goals. For this, it showed the consolidation and expansion of the large-scale tests, with national and international examples, to focus on initiatives developed in Brazil at the district level, The conclusions highlight the need to retake the technical debate, along with political considerations, on the use of assessment results and educational indicators for the proposal of public policies directed to schools.

Keywords: Large-Scale Assessment; Educational Indexes; Districts; Performance; Quantophrenia

Este artigo problematiza a ênfase dada em municípios brasileiros a aspectos quantitativos do desempenho dos alunos, mensurados por indicadores e médias de proficiência, em detrimento à discussão sobre a aprendizagem e o significado pedagógico dos dados e à produção de indicadores de processos que se associam ao atingimento (ou não) das metas. Inicialmente, contextualiza-se a consolidação e expansão das testagens em larga escala no Brasil e no mundo para, em um segundo momento, discutir iniciativas desenvolvidas nacionalmente, em âmbito municipal. Conclui-se que é necessário retomar o debate técnico e pedagógico, aliado às considerações políticas sobre o uso dos resultados das avaliações e de indicadores educacionais para a proposição de políticas públicas voltadas às escolas.

Palavras-chave: Avaliação em Larga Escala; Índices Educacionais; Municípios; Desempenho; Quantofrenia

Introduction

The expansion and consolidation of external and large-scale assessments of learning networks and educational systems, a phenomenon observed in several countries and in Brazil, at the federal, state and municipal levels (Madaus et al., 2009; Bauer, 2010; Rey, 2010; Tobin et al., 2015), has been widely discussed in recent years, and is not a new phenomenon. The explanations for this expansion vary, ranging from the need to monitor the progress of students’ access to basic levels of education and their level of learning, to the influence of new forms of educational management proposed by multilateral organizations. These organizations would use these assessments as one of their monitoring and control tools (Rey, 2010; Mons, 2009). Connections between the expansion of large-scale testing and changes in the logic of educational organization and management, driven by globalization and the subjection of education to market forces (Benett, 1998; Afonso, 2000; Ball, 2004), are also present in the literature in the field, which is full of arguments both for and against this type of initiative (Bauer; Alavarse; Oliveira, 2015).

Although very much centered on the US and European contexts, the growing presence of large-scale testing encompasses countries on all continents. A survey carried out by the present author in 2010 already pointed out that, of the 35 countries on the American continent, 21 had their own external assessment systems or initiatives (Bauer, 2010).

At the same time, Rey (2010) also noted the expansion of this type of initiative on the European continent, stating that, by the beginning of the last decade, most countries1 were already using some type of standardized external assessment, either at federal or regional levels:

A large majority of European countries now use external standardized assessments at the regional or national level. Up until the 1990s, only a small number of countries used national tests in compulsory education (primary and lower secondary education), either for transition purposes to the next year (Iceland, Portugal, Scotland, Northern Ireland, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Denmark and Malta) or to provide diagnostic information on the education system as a whole (Ireland, France, Hungary, Sweden and the United Kingdom). Ten other countries and regions followed suit in the 1990s, including Spain, the French Community of Belgium, Latvia, Estonia, and Romania. Since the early 2000s, national tests have been introduced in the Flemish Community of Belgium, Lithuania, Poland, Norway, Slovakia, Austria, Germany, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Denmark and Italy (Rey, 2010, p. 140-141)2.

The present author points out that, from the 1990s onwards, testing began to be used not only to control results from the perspective of an evaluating state - which would be absent from educational processes, controlling only the results obtained -, as much of the relevant literature discusses, but also to direct what is done in these educational systems. This allows us to question the extent to which there is, in fact, decentralization of management in the various administrative spheres that make up the educational systems of the countries analyzed. This question is valid, as will be argued later, for the Brazilian case, based on the reality of municipal assessments.

In any case, the management logic that calls for external assessment of student results as a tool to control what is done in educational systems is not a privilege of the Western world. The report produced by Clarke, Liberman and Ramirez (2012), experts at the World Bank, indicates that, in East Asia, nine countries had national assessment systems at the time of the study: Cambodia, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Laos, Malaysia, Mongolia, Thailand and Vietnam. In addition to these countries, Hong Kong and Shanghai, in China, have also implemented external student assessment systems, including budgets for these assessments. Tobin et al. (2015), in addition to reinforcing the information on most Asian countries already mentioned, report that there are large-scale assessments in New Zealand and Australia.

Finally, there are reports of large-scale assessments developed in Mozambique (World Bank, 2009), South Africa (Hoadley; Muller, 2016), Uganda (Allen et al., 2016) and several countries on the African continent, driven by three assessment programs: the Monitoring Learning Achievement (MLA) (Chinapah, 2003), the Southern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SACMEQ) and the Programme d’Analyse des Systèmes Educatifs des Pays de la CONFEMEN (PASEC). Kellanghan and Greaney (2001) had already identified 47 countries participating in the MLA, 15 in SACMEQ and 9 involved in PASEC3. The authors point out the connection between the various assessments and the proposal of educational policies, not necessarily proposed or influenced by multilateral organizations, which is common in critical studies of the phenomenon. They also notice a number of problems in the proposed assessment designs, which will not be discussed in depth in this text.

In other words: obtaining information of various kinds about the education system, the flow of students and their learning, has become a practice in various countries since the end of the 20th century. Initially, in the wealthiest and most central of those countries and, later, in those who face more socioeconomic challenges, whether semi-peripheral or peripheral (Barfield, 1997). The point is that the use of information for educational management, whether encouraged by multilateral organizations or not, is a reality regardless of a country’s level of economic power or its political regime.

The common aspect of the assessments developed both locally, in the various countries, and in the international assessment programs, is that their main goal is to improve the quality of education. This is true at least on a discursive level, even though the concept of quality varies from place to place. There are, for example, countries where quality is understood as access to basic schooling. Meanwhile, others have already resolved access issues and are looking for good learning standards for students, whereby quality is understood as reaching performance standards in school subjects.

What seems to differ between countries is the culture that is created around these assessments, the learning areas they assess, the educational systems they affect, the level of data collection they achieve and the use made of the results. These are sometimes seen as tools used to manage educational policies and programs at the level of the educational system, and sometimes as proposals that seek to reverberate at the level of the schools. According to Brink (2020), different types of assessment designs serve different purposes. Census assessments, for example, suitable for smaller systems, would serve to assess the educational “health” of each country and analyze differences between groups of individuals, while sample assessments could be used to monitor the development of learning, to design paths for the future.

Although there has been an increase in the use of these assessments, focused on student performance, in determining public educational policies, what seems to differ in Brazil from some international initiatives is the widespread use of census designs and the growing reliance on the results obtained for educational management at a meso- and micro-level, both inside and outside the classroom.

It is worth remembering that the proposal for assessments of student performance in the country began to develop in the early 1990s, first at the federal level (Gatti, 2013) and later moving on to the states, with several changes to their objectives and methodological designs (Bonamino, 2013) over time. Initially, the expansion of these assessments across the states was uneven. However, following the proposal of the Basic Education Development Index (IDEB4) (Bauer; Horta Neto, 2018), there has been an expansion of state-level assessments: by the end of the last decade, 21 of the 27 subnational states had their own assessment systems. More recently, in addition to state proposals, we have seen the emergence of municipal assessment proposals, as will be discussed later. In addition, there was a trend to incorporate assessments of new stages of education into the Basic Education Assessment System (SAEB) and the Science curriculum component, in addition to the already existing assessments for students in the 5th and 9th grades of primary education and the 3rd year of high school.

Initially, in Brazil, external assessments were justified by the need to obtain information that could be useful to support decision-making at the national levels (Pestana, 2013; Gatti, 2013), assuming a diagnostic function, without any direct consequences for schools, their actors and the pedagogical practices carried out in them. However, since the early years of the 21st century, with the expansion of the proposals and the technical changes introduced in the assessment designs of the main initiatives, there have also been changes in the objectives and underlying functions of the assessments. These include the tendency to attach strong or mild consequences (Brooke, 2005, 2006; Andrade, 2008), “symbolic” or “material” (Bonamino; Sousa, 2012), to the results obtained, as well as a strong appeal to their inductive character, either by establishing standards and desirable levels of performance, or by strengthening the system of targets and performance indicators that allow the monitoring and evolution of the results obtained.

The establishment of this modus operandi has led to various criticisms about the excessive valuation of quantitative information, to the detriment of information about the educational processes that take place in the contexts that generate these results.

Regarding test performance results and the IDEB, little has been discussed about the technical aspects themselves. There is still a timid discussion about the validity and reliability of the data collected, measurement errors, and the limits and potential of establishing goals, their meanings, and other factors that would be important for making informed decisions. It is also noted that technical aspects are rarely reported in the reports produced. Furthermore, in the dissemination and use of results in the daily management of education departments and schools, it is common to see actions that seem to disregard the fact that the indicators obtained from the assessments are a portrait of a more complex reality. Therefore, they should not be confused with this same reality, nor should they assume the status of absolute truth about the development of students and educational systems, as Paulo Jannuzzi (2001) states.

The following sections will illustrate the emphasis placed on measurable aspects of educational results in Brazilian municipalities, based on data obtained from a study that aimed to map the characteristics of existing assessments in these federal entities. The study and its methodological approaches are outlined below.

Study procedures on educational assessment in Brazilian municipalities5

The mapping of existing municipal assessment initiatives in Brazil was carried out through a survey, using the online tool Survey Monkey, with the objectives of: (1) obtaining information on whether or not municipalities have their own external assessments, (2) identifying the reasons for their creation, and (3) characterizing their methodological outlines and the uses made of the results for educational management. The questionnaire, structured in four dimensions and with 44 questions (open and closed), was sent to 5,532 of Brazil’s 5,570 municipalities, i.e., 99% of the total.6

The structuring dimensions of the instrument were: identification of the municipality; participation of the municipality in assessments proposed at the federal and state levels; existing assessments in the municipal network (which may consist of students, teaching professionals and managers or institutional assessment) and characterization of the uses of the assessments. Data were collected between April and July 2014 (Bauer; Horta Neto, 2018).

Of the 5,532 municipalities contacted, 4,309 responded to the survey, representing 77% of the total number of all Brazilian municipalities. Of these, 1,573 claimed to have their own assessment system. The present text uses the answers obtained from this subset of municipalities, which cover all five geographic regions of the country and all Brazilian states.

First, there is no apparent link between any specific assessment and the characteristics of the municipality - size, number of inhabitants and number of schools in the education networks. This is because assessment initiatives were reported by the education departments within small, medium and large municipalities, with larger and smaller school networks. This allows us to say that this type of assessment exerts an apparent fascination over the education secretaries, who generally perceive them as an education management strategy, but do not necessarily have a previously defined, logical management plan.

Table 1 shows the expansion of municipal external assessments since 2010. The data show that the expansion process began, with few exceptions, in the 2000s, consistent with the international expansion movement. Only 34 municipalities claimed to have their own assessments before the 2000s (up to 1999). Of these, 15 claim that the year in which this type of assessment began coincides with the year in which the municipalization of schools began in the municipality7.

Table 1: Distribution of responding municipalities

| Year in which the municipal assessment initiative began | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Before 1990 | 2 | 0.1 |

| Between 1990 and 1999 | 32 | 2.0 |

| Between 2000 and 2009 | 449 | 28.5 |

| Between 2010 and 2013 | 794 | 50,5 |

| January to July 2014 | 106 | 6.7 |

| Missing responses | 190 | 12.1 |

| Total | 1,573 | 100 |

Source: Author, based on research data.

It should be noted that this expansion process does not necessarily seem to be linked to the search for alternatives, at the municipal level, to the logic that governs the assessments already existing at the federal and state levels. This is because most municipalities that claim to use their own external assessment also participate in other assessment initiatives, proposed by the federal or state government, concomitantly with the local proposal in an accumulative movement. This fact is evidenced when, of the 1,573 municipalities that claim to have their own assessment system, 96.8% also participate in Prova Brasil, 99% in Provinha Brasil, 97.4% in the National Literacy Assessment and 98.3% in assessments organized by their respective state government.

In addition, among the possible types of external assessment carried out by municipal education management, large-scale assessment initiatives focused on student performance stand out, mentioned by 1,302 municipalities. Meanwhile, proposals for institutional assessment are mentioned by 977 respondents, professional assessment by 624, and other types of assessment by 99 representatives of the municipalities consulted. The proposal for an external, large-scale assessment of their own, focused on students, is generally seen as a complement to what already exists, rather than a replacement or an alternative. This generates the aforementioned overlapping of tests in education networks.

According to the testimonies collected from the municipal departments of education of these municipalities, the proposal for their own large-scale assessment initiatives is justified by the concern with the quality of the educational services offered. It is also justified by the demand for better management (understood as efficient and effective) of the available resources and educational policies and programs, considering the data produced by them as sources of information for their improvement (Bauer; Horta Neto, 2018).

Added to these factors is the idea of diagnosing and monitoring teaching and learning, which is very present in the respondents’ speeches. Also present is the view of assessment as an instrument for planning pedagogical interventions, controlling and adapting curricula, proposing continuing education activities, evaluating teaching work and mobilizing teachers and students for educational activity.

The answers also reveal the belief that student assessment can lead to improvements in educational indices (flow, dropout and repetition), as well as help to achieve results and targets set both at the federal level and by the municipal administrations themselves. In the statements made in the open questions, there were explicit references to the increase in the IDEB. In other words, there was a concern with the quantitative aspects of the assessment results.

Discussion of results

As previously mentioned, of the 1,573 municipalities that claimed to have their own evaluation in place in the middle of the last decade, 1,302 attest that the focus of the evaluation proposal is the students, by assessing their school performance. These municipalities were given a closed question, listing eight objectives8 that they were trying to achieve through their own evaluation initiative, and they could choose the alternatives that best matched their reality.

Table 2 shows the highest response rates, in descending order. In addition to affirming their concern for student learning, pointed out by 71.8% of respondents, the main objectives highlighted were: improving the IDEB and defining the management priorities, i.e., a concern with increasing a measure.

Table 2: Objectives of their own assessments, focusing on student performance, proposed by Brazilian municipalities

| Objectives of student-focused assessments | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Improve student learning | 1,130 | 71.8 |

| Improve the IDEB | 528 | 33.6 |

| Set priorities for municipal education management | 524 | 33.3 |

| Obtain information for continuing education | 454 | 28.9 |

| Reduce the repetition and/or dropout rate | 431 | 27.4 |

| Improve municipal network management processes | 239 | 15.2 |

| Disseminate school results to parents and the community | 73 | 4.6 |

| Obtain information for school awards/bonuses | 45 | 2.9 |

Source: Author, based on survey data.

To understand the methodological designs proposed in the municipal assessments aimed at students, a series of questions were asked that aimed at gathering information on the subjects and grades assessed, the ways in which the results were analyzed, the periodicity of the assessment, the types of items produced, among other information.

Although, more recently, there has been a movement to broaden the subjects and grades assessed, including at the municipal level, the focus of the various assessments is usually on the same aspects: cognitive content, especially in Portuguese and Mathematics, the final grades of each cycle or stage of education. Results found in a study by Bauer and Horta Neto (2018), focused on mapping the usual designs in municipal large-scale assessment proposals, show that 48.1% of municipalities already tried to measure students’ knowledge in science (even before the introduction of these components at the federal level), 45.1% considered monitoring the results obtained in History, and 44.7% observed performance in Geography. Other curricular components also considered by the municipalities in their own assessments were Arts (32.6%), Physical Education (32.0%) and Foreign Language (29%); although, thinking about an external assessment for these curricular components can be challenging and even lead to estrangement. In relation to the subjects commonly assessed, 93.8% of the municipalities claimed to assess Reading and Interpretation, 76.9% assessed knowledge of Grammar, and 72.8% sought to monitor the development of writing skills through writing tests. 91.7% assess Mathematics.

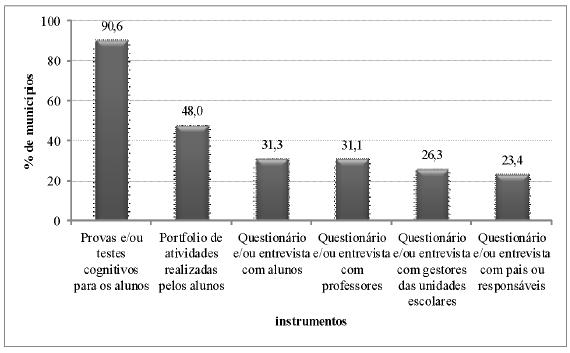

Graph 1 shows the data collected with the assessment instruments used. From this analysis, it can be said that the student assessments proposed in the municipal networks tend to use tests and/or cognitive examinations to assess their performance, which may or may not be associated with questionnaires or interviews with various actors (managers, teachers, students, parents or guardians).

Source: Bauer and Horta Neto, 2018.

Graph 1: Proportion of municipalities that use each of the aforementioned instruments, among the municipal networks that have student assessment

This question was aimed at identifying the characteristics of the data processing and analysis models. It was answered by 1,096 of the 1,302 municipalities that reported having an external assessment aimed at students. The indications obtained allow us to claim that the results tend to be analyzed using tabulations and/or graphs, and to organize summaries of the results and information in databases. Fewer respondents stated that the results are analyzed collectively, through meetings, gatherings and seminars (112 indications). There are also records of data being compared with matrices or other defined targets (90 records). Two capital cities reported using the Item Response Theory (IRT) as their analysis methodology.

The impression one gets from reading the testimonies is that many of the evaluations lack the basic technical requirements to guarantee their validity and reliability. The analysis and dissemination of the data does not seem to incorporate more sophisticated statistical methodologies but mentions, instead, the production of graphs and tables as a means of organizing and interpreting the data, as the following statements illustrate.

A notebook containing 20 items of Portuguese Language and 20 items of Mathematics. The school receives the kit containing the question notebooks, a document with application and return guidelines. The correction is made by the technicians of the Municipal Department of Education and the results are cataloged and represented in graphs (Bauer; Horta Neto, 2018, p. 86).

The diagnostic assessment is carried out every six months with elementary school students. Teachers receive from the Municipal Department a key to correct the tests that are applied to students. The results are forwarded by the school unit coordinator, and the data are tabulated at the Department for analysis and later dissemination (Bauer; Horta Neto, 2018, p. 87).

This is not to say that municipal education networks should resort to experts in educational measurement to produce data to support educational management. The question of technical quality is controversial, and there is a vast body of literature critical of the emphasis on the technical aspects of assessment to the detriment of the political, ideological and pedagogical aspects underlying the models used for measuring and analyzing student performance data.

What is being questioned is the emphasis that has been placed on monitoring proficiency measures as a way of improving educational quality, which leads even small municipalities, often with a reduced financial, administrative and technical structure, to adopt large-scale assessment of student performance as an educational management tool, even without having the technical capacity to carry out in-depth analysis of the data produced. It seems that the idea that monitoring learning is important is taken for granted, with no discussion of the nature of the instruments used, their validity, and the reliability of the results obtained in any depth. In fact, concepts such as validity, reliability, test statistics, among others, which illustrate a concern with the quality of what is being “measured” or with the information that is being collected through the initiatives, are missing from the responses obtained in the survey.

However, this does not prevent important decisions from being made about the education system: the data obtained is used, according to the testimonies, to improve the curriculum, affect teacher training, etc. Although the uses “with strong consequences” (Carnoy; Loeb, 2002; Brooke, 2006) are residual, and many of the testimonies attest to the fact that the rationale behind these assessments is formative and diagnostic, it would be important to take a more critical look at the possibilities and limits of the data produced.

In addition to the proposals to test students’ knowledge, some of the municipal assessment initiatives produce quantitative indicators, similar to the IDEB, the national indicator mentioned above. Of the 1,573 municipalities that claimed to produce their own assessments, 231 said they had been producing their own educational indicators for around ten years, which corresponds to 14.7% of all valid responses. Others claim to use a system for producing educational quality indicators similar to the one proposed at the federal level.

When mentioning the components considered as indicators for local management, most managers refer to results indicators, such as flow measures (approval, retention, absenteeism, dropout and school evasion rates) and proficiency (averages obtained in the various tests / external evaluations), considered by the interviewees as central concerns in education. Some managers claim to be aware of the need to produce input and process indicators, as exemplified below with aspects collected from the survey responses:

Input indicators: infrastructure, expenditure per student, investment in teacher training, teacher salary;

Process indicators: information on didactic-pedagogical organization, institutional planning, information on student service, teaching and learning process, organization of the physical school environment, pedagogical practice, democratic school management, working conditions of school professionals, and student access and permanence rates at school;

Outcome indicators: flow (approval, retention, dropout and absenteeism rates), age-grade distortion rate, literacy rate and student performance in standardized exams (results obtained in the various external tests/assessments), etc.

However, although the testimonies point to various types of indicators, the emphasis is on the results indicators: of the 199 valid responses obtained, to the open question that asked respondents to explain the components of the indicator proposed by the municipality, 75.4% referred to results indicators and 14.6% to process indicators. Only two responses mentioned input indicators, and several answers did not refer to the subject of the question and were disregarded from the analysis. Among the responses that referred to aspects considered by the municipal education network, when assessing the quality of teaching, the majority of mentions refer to aspects related to students; in second place, items related to schools are mentioned; and, those related to teachers are practically disregarded (only five responses).

In the municipalities studied, the indicators do seem to be used as an aid to decision-making and to guide management processes. Following on from this appropriation of the idea of having educational indicators to monitor education, which has probably been influenced by the IDEB, there is a tendency to set targets - understood as quality drivers - to guide the performance of schools. This is illustrated by statements about the purpose of developing municipal educational indicators:

“Achieving the targets proposed by the municipal education network”.

“Based on the IDEB results and improvement in literacy, indicators and targets to be achieved were created.”

“Performance and participation based on targets set by the Department of Education”.

“Set targets to reach 100% proficiency by all students in the municipal network by 2016. Projection of 30% in the year 2014; 50% in the year 2015; 20% in the year 2016”.

“Seven learning targets were created/established based on the map and strategic planning of the Municipal Department of Education.”

“Setting educational quality targets for the Municipal Network, expanding Continuing Education, instituting internal assessment in the municipality in accordance with the standards, norms and criteria of the Federal and State Government Assessments, so that students take ownership of these norms established when carrying out the assessments” (Bauer; Horta Neto, 2018, p. 118).

While there is a lot of concern and discussion around the numerical targets that municipalities and schools should reach, little attention seems to be paid to what the results obtained mean and what clues they may or may not provide for achieving desirable levels of student learning. There has been little discussion of the performance scales themselves within the policy-making bodies, even though municipal managers’ statements refer to the SAEB matrices and scales, endorsing them.

If there has been little discussion in academic circles about what a rise in the IDEB - the best-known educational indicator - means, in terms of learning, it’s not surprising that this absence is also present in the discourse of school administrators. After all, in addition to reducing failure rates, wouldn’t it be desirable for students to develop more complex skills and knowledge in the curricular components assessed? Have educational systems in general, and schools, more specifically, discussed strategies to ensure that students learn more and better, a crucial objective in the educational process? Or, have they just tried to respond thoughtlessly to the demands for an increase in the indices and indicators valued in the policy discourse? Based on the research, the impression is that the tendency is to respond positively to the last question raised here: there is a lot of concern with the search for results (which is not a bad thing in itself), but without trying to understand the real meaning of the result in terms of learning and the processes involved in the school environment. It is this unbridled and ill-considered search for numbers that is considered, in the present text, to be a quantophrenic outburst that does not necessarily contribute to improving the quality of learning and, consequently, of education.

The importance that is currently attached to the IDEB - especially its component for assessing student performance - at the municipal level, even leading to proposals for its own assessment and indicators, and the adoption of mock exams and curricula related to the content covered in the national tests, seems to lie in the common understanding that what is being assessed is the quality of teaching or of education itself, given that this is how the indicator is understood and has mistakenly been propagandized to society.

However, there is no evidence in the respondents’ statements that the concern with the metric is accompanied by the understanding of the existing challenges to improve learning, or of the concrete situations to overcome them, given the context in which the results are produced, even though the concern with this improvement is part of the discourse.

Measures of educational quality: a quantophrenic9 outbreak or a need for management? Proposal for a research agenda

In the early 2000s, Iaies (2003) warned of the need to recover the meaning of evaluating educational systems and of the links between this type of evaluation and the political-philosophical decisions of managers. For the author, evaluations were becoming models whose priority was to measure student performance and not to evaluate10 the system as a whole.

According to Iaies, the lack of clarity about the objectives of the system assessment and the difficulty of defining and agreeing upon clear quality standards, which allow us to compare longitudinally the results obtained and which could be used to analyze the possible changes, operated from the policies and programs implemented. This made the concerns fall on the results of the tests and their technical dimension (at most), disregarding the contextual analyses that would allow a better understanding of the educational situation and a more effective intervention. As the author explains, “the educational systems stopped working to improve educational quality and equity, and started working to improve the results of the assessments” (Iaies, 2003, p. 18).

Thus, there would be a distance between technical considerations (which underlie the assessment) and the political-educational debate (which needs to be addressed both at the school and the central levels). According to the author:

Indicators were built that were technically defined, and that almost exclusively consider academic skills. Our indexes do not consider the increase in schooling rates, the system’s ability to homogenize actors in an increasingly segmented society, to account for the new audiences that the school has been able to house, the ability to contain other social realities, etc. And these definitions imply taking an ideological stance, using some variables and abandoning others; what is certain is that the experience of the 90s makes us think more of a “non-taking” of a political position, in the sense that decision makers did not position themselves on this point (Iaies, 2003, p. 20-21).

The analysis of the configuration of network assessment proposals, provided by several Brazilian municipalities, allows us to affirm the timeliness of the debate proposed by IAIs twenty years ago, when network assessment models were only expanding. In addition, it allows us to question whether the regional assessment designs are really guided by multilateral organizations or whether there is a proper management logic being re-signified and built at this federated level. This is the central argument in the present article: Brazil would have developed its own culture in the implementation of external and large-scale assessments, not necessarily being hostage to the indications of multilateral organizations. There is no denying that there is also a quantophrenic outbreak that has affected several countries, states and educational districts, often generating an overlap of assessments in the same context, even designed to assess the same aspects.

Thus, it is necessary to resume the discussion about the role that large-scale assessments have assumed in society (Broadfoot, 1996), and more specifically, their role in the management of education and teaching quality (Pestana, 2013). This is mainly because such initiatives are increasingly related to educational policies and programs.

The lack of clarity about the purposes, possibilities and limits of large-scale assessment, to support the management of the educational system, may perhaps be related to the apparent lack of effectiveness of the proposals themselves. After all, if evaluating and providing accurate measures of student performance were a sufficient strategy, to overcome the teaching difficulties of schools, it would not be necessary to appeal to high-impact policies which are almost always based on the results obtained by students.

What the quantophrenia that is currently observed in Brazil seems to disregard is that the measure, even when of undeniable technical quality - as is the case with federal and some state and municipal tests -, does not replace the actions that need to be carried out to conduct a broader educational reform. The focus of such reform would be the improvement of education in several aspects, not only in quantifiable aspects of students’ cognitive performance.

Another aspect that can be observed in the municipal initiatives analyzed, related to the above, is that the central concern of the technical teams seems to be to produce information, obtained through the instruments used, to the detriment of exploring the potential of that information for educational change. Even in municipal proposals, where there is greater concern with a reflected analysis of the results and their use for decision making, the development and dissemination of this type of analysis seems still rudimentary, being little used for the re-development of pedagogical strategies or redirecting of educational policies. In other words, the strong appeal to the results, indicators and establishment of learning goals seems to assume its own characteristics in the Brazilian context. Although there is a pedagogical discourse as a justification for the appreciation of tests and indicators, and even for more pointed management intervention in the classrooms directly, there is no evidence that quantitative information is understood in its pedagogical sense.

This mismatch between the production of information, and its analysis and use for the improvement of education, had already been pointed out by Iaies in the 2000s (Iaies, 2003) and is also identified in several other works (Bauer, 2010).

On the other hand, managers are concerned about obtaining information that can be used at the local level, that is, in the schools. There have been few studies that are concerned with analyzing how the results obtained through their own external assessments can be used positively at the local level, either by the education departments or by schools. In this sense, although the assessments produced locally may be more committed to assessing the reality of the work carried out by schools, little is known about the characteristics of these local assessments and the mechanisms that they give rise to in schools.

It is also necessary to discuss the statistical models used in the assessments (design, scales, reference matrices), the methodologies of data analysis (IRT versus Classical Theory), and the procedures for analysis and use of the data obtained. It is also necessary to discuss the extent to which the results, as presented, make sense for the managers and teachers who should appropriate them. There are even researchers who point to the limits of the quantitative data that have been produced by the various tests of existing students, especially with regard to their pedagogical use and their limitations to support the work of teachers who do not appropriate their results.

My opinion is that, with assessment, we have fallen into a numerology that is becoming empty. The results of Item Response Theory are translatable on a scale - 125, 250, etc. - that does not bring easily understandable information to schools and teachers. For example, a student who reaches a 125 (sic) scale can write a note, with some language difficulties. But that doesn’t mean anything to the literacy teacher. What’s behind this? What process is built into this? Item Response Theory - the way the scale is done and the matrix is designed - doesn’t give that kind of answer. You were meant to wear this swimsuit. The test is a “random” test. It is something designed to evaluate, in theory, a latent trait of learning potential. It’s a potential trait. It is very difficult for schools to understand and deal with this indicator, even turning it into a scale from 0 to 10 or from 0 to 100, closer to general understanding. It does not inform about the specific performances and learning processes. The information is generic (Gatti, 2011, p. 10).

Although the benefits for public policies arising from the use of analysis theories such as IRT cannot be disregarded - since they allow comparisons between populations over time and they answered different tests (as long as they have common items), they allow us to analyze the development and evolution of individuals evaluated in a certain latent trait (Valle, 2000) -, they are poorly understood and need a lot of investment in training and support materials so that teachers can appropriate their results in support of learning.

Another aspect that deserves in-depth reflection refers to the selection of the content and skills that support the assessments, as well as their definition of performance levels or standards, in both their technical (what to measure and how to measure) and pedagogical characters. The concern with the relationships established between assessment and curriculum, as well as the discussion about what is measured and the more general curriculum, which constitute the broader training project to which all students should have access, appear secondarily in the discourses of managers registered through the survey.

Until the middle of the second decade of the present century, there was a movement in Brazil that sought to formulate and disseminate the Assessment Reference Matrices, which began to be considered as a subsidy to the pedagogical work of schools. This movement proceeded without such formulation having been accompanied by a broad debate on the purposes of education which, in theory, would define the curricula and later the discussion on the basic learning whose acquisition one would like to monitor (Bauer; Gatti; Tavares, 2013). No evidence was found in the literature that such logic also accompanied the assessments that occur in other countries, based on guidelines from multilateral organizations. Even in relation to the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), which has been considered an instrument to induce pedagogical practices for countries participating in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), it is worth questioning this critical trend since the curricula of this international program are neither widely known nor disseminated.

In any case, until the approval of the National Common Curricular Base (BNCC) in 2017, the debates on the selection of content and skills that support the assessments seem to have been relegated to the background, to the detriment of discussions on standards, goals and indicators. In this sense, it is worth asking: what views of education, youth and the world, guide the matrices and assessment parameters that have been adopted in Brazil’s education networks? What basic content are all students expected to learn? Or, what are the minimum standards that are desired, considering the real social needs and development possibilities of students? Even at the time of implementation of the first national common curricular base11, it seems that such reflections still lack development at the national level.

Finally, it should be noted that, although many researchers dedicate themselves to the study of system assessments or large-scale testing (Bauer, 2010) and the problems arising from them, these reflections seem to have little dialogue with the needs and interests of managers and proposers of educational policies. This results in an apparent disarticulation, or distancing, between the academic environment and the reality of management, which remain isolated in their respective fields of activity.

Despite the growing expansion of these assessments, and their consolidation worldwide, it is necessary to continue the technical and political discussion about this object of study. This discussion is necessary to denaturalize the current assessment practices and not allow the political frameworks and managerial principles to which these evaluations were initially linked to submerge.

In Brazil, where more than thirty years have passed since the implementation of the first assessment systems, there is an urgent need to resume the studies already carried out and to conduct a broad review of the assumptions that have been guiding the assessment actions at all levels. Questions raised by members of the academy, more distant from the bodies responsible for the design and management of assessments, seem to have little influence on managers and assessment teams that, with rare exceptions, remain, at least at the level of discourse, unaware of the limitations of the uses of assessment results to achieve educational improvement.

From the study partially reported in part in the present text, it is clear that the debate on assessment must be faced in its complexity. This is so that the systems already consolidated can develop and produce information that allows them to overcome the political and ideological uses that have been made of the results. This debate would effectively contribute to shed light on the educational problem, making it possible to carry out actions that are actually directed to the improvement of education, which requires an analysis that goes beyond the comparison of quantitative results on learning levels. That analysis also considers curricular, infrastructure and teacher training aspects, among others.

REFERENCES

AFONSO, Almerindo. Avaliação educacional: regulação e emancipação. São Paulo: Cortez, 2000. [ Links ]

ALLEN, Reg; ELKS, Phil; OUTHRED, Rachel; VARLY, Pierre. Uganda’s assessment system: a road map for enhancing assessment in education. Oxford: Health & Education Advance & Resource Team, 2016. [ Links ]

ANDRADE, Eduardo de Carvalho. “School accountability” no Brasil: experiências e dificuldades. Revista de Economia Política, v. 28, n. 3, p. 443-453, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-31572008000300005 [ Links ]

BALL, Stephen. Performatividade, privatização e o pós Estado. Educação e Sociedade, v. 25, n. 89, p. 1105-1126, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302004000400002 [ Links ]

BARFIELD, Thomas. The dictionary of anthropology. Hiboken: Wiley-Blackwell, 1997. [ Links ]

BAUER, Adriana. Uso dos resultados das avaliações de sistemas educacionais: iniciativas em curso em alguns países da América. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos, v. 91, n. 228, p. 315-344, 2010. https://doi.org/10.24109/2176-6681.rbep.91i228.576 [ Links ]

BAUER, Adriana; GATTI, Bernardete Angelina; TAVARES, Marialva Rossi. Ciclo de debates. Vinte e cinco anos de avaliação de sistemas educacionais no Brasil: origem e pressupostos. Florianópolis: Insular, 2013. [ Links ]

BAUER, Adriana; ALAVARSE, Ocimar Munhoz; OLIVEIRA, Romualdo Portela de. Avaliações em larga escala: uma sistematização do debate. Educação e Pesquisa, v. 41, n. spe, p. 1367-1384, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-9702201508144607 [ Links ]

BAUER, Adriana; HORTA NETO, João Luiz. Avaliação e gestão educacional em municípios brasileiros: mapeamento e caracterização das iniciativas em curso. Relatório Final - Resultados do survey. Brasília: INEP, 2018. v. 2. [ Links ]

BENETT, Randy Elliot. Reinventing Assessment. Speculations on the Future of Large-Scale Educational Testing. A Policy Information Perspective. Princeton: Educational Testing Service, 1998. [ Links ]

BONAMINO, Alicia. Avaliação educacional no Brasil 25 anos depois: onde estamos? In: BAUER, Adriana; GATTI, Bernardete Angelina (Org.). 25 anos de avaliação de sistemas educacionais no Brasil: implicações nas redes de ensino, no currículo e na formação de professores. Florianópolis: Insular, 2013. p. 43-60. [ Links ]

BONAMINO, Alicia; SOUSA, Sandra Zákia. Três gerações de avaliação da educação básica no Brasil: interfaces com o currículo da/na escola. Educação e Pesquisa, v. 38, n. 2, p. 373-388, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-97022012005000006 [ Links ]

BRINK, Satya. Effective use of large-scale learning assessments: to improve learning outcomes and education system reform. Dakar: Unesco, 2020. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000375333 [ Links ]

BROADFOOT, Patricia. Education, assessment and society: a sociological analysis. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1996. [ Links ]

BROOKE, Nigel; CUNHA, Maria Amália de Almeida. Avaliação externa como instrumento da gestão educacional nos estados. São Paulo: Fundação Victor Civita, 2014. Volume 4 - série Estudos & Pesquisas Educacionais. [ Links ]

BROOKE, Nigel. Accountability educativa en Brasil: una visión general. In: SEMINARIO INTERNACIONAL ACCOUNTABILITY EDUCACIONAL: POSIBILIDADES Y DESAFÍOS PARA AMÉRICA LATINA A PARTIR DE LA EXPERIENCIA INTERNACIONAL, 2005, Santiago do Chile. Programa de Promoción de la Reforma Educativa en América Latina y el Caribe. Santiago de Chile: Unesco, 2005. [ Links ]

BROOKE, Nigel. O futuro das políticas de responsabilização no Brasil. Cadernos de Pesquisa, v. 36, n. 128, p. 377-401, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-15742006000200006 [ Links ]

CARNOY, Martin; LOEB, Susanna. Does external accountability affect student outcomes? A cross-state analysis. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, v. 24, n. 4, p. 305-331, 2002. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737024004305 [ Links ]

CHINAPAH, Vinayagum. Monitoring Learning Achievement (MLA) Project in Africa. In: ADEA BIENNIAL MEETING, 2003, Grand Baie. Proceedings […]. Grand Baiei: Association for the Development of Education in Africa, 2003. https://biennale.adeanet.org/2003/papers/2Ac_MLA_ENG_final.pdf [ Links ]

CLARKE, Marguerite; LIBERMAN, Julia; RAMIREZ, Maria-Jose. Student Assessment. In: PATRINOS, Harry (Ed.). Strengthening education quality in East Asia: SABER System Assessment and Benchmarking for Education Results. Washington: The World Bank, 2012. p. 27-44. [ Links ]

EURYDICE. National testing of pupils in Europe: Objectives, Organization and Use of Results [online], 2009. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/dac32463-5f05-4782-898b-dd399e66efc6 [ Links ]

GATTI, Bernadette. Números vazios. In: BAUER, Adriana (Org.). Avaliação Educacional. Escola Pública (Especial Avaliação Educacional), São Paulo, 2011. p. 45-59. [ Links ]

GATTI, Bernardete. Possibilidades e fundamentos de avaliações em larga escala: primórdios e perspectivas contemporâneas. In: BAUER, Adriana; GATTI, Bernardete Angelina; TAVARES, Marialva Rossi (Orgs.). Ciclo de debates. Vinte e cinco anos de avaliação de sistemas educacionais no Brasil: origem e pressupostos. Florianópolis: Insular, 2013. p. 47-70. [ Links ]

HOADLEY, Ursula; MULLER, Johan. Visibility and differentiation: systemic testing in a developing country context. The Curriculum Journal, v. 27, n. 2, p. 272-290, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2015.1129982 [ Links ]

IAIES, Gustavo. Evaluar las evaluaciones. In: IAIES, Gustavo et al. Evaluar las evaluaciones: una mirada política acerca de las evaluaciones de la calidad educativa. Buenos Aires: IIPE: UNESCO, 2003. p. 15-36. [ Links ]

JANNUZZI, Paulo. Indicadores sociais no Brasil. Campinas: Alínea, 2001. [ Links ]

KELLANGHAN, Thomas; GREANEY, Vicent. Using assessment to improve the quality of education. Paris: UNESCO, 2001. p. 19-20. [ Links ]

MADAUS, George; RUSSELL, Michael; HIGGINS, Jennifer. The paradoxes of high stakes testing: how they affect students, their parents, teachers, principals, schools, and society. Charlotte: Information Age, 2009. [ Links ]

MONS, Nathalie. Theoretical and real effects of standardized assessment policies. Revue Française de Pédagogie, v. 169, p. 139-140, 2009. https://doi.org/10.4000/rfp.1531 [ Links ]

PESTANA, Maria Inês de Sá. A experiência em avaliação de sistemas educacionais: em que avançamos? In: BAUER, Adriana; GATTI, Bernardete Angelina; TAVARES, Marialva Rossi. Ciclo de debates. Vinte e cinco anos de avaliação de sistemas educacionais no Brasil: origem e pressupostos. Florianópolis: Insular, 2013. p. 117-136. [ Links ]

REY, Olivier. The use of external assessments and the impact on education systems. In: STONEY, Sheila (Ed.). Beyond Lisbon 2010: perspectives from research and development for education policy in Europe. Slough: National Foundation for Educational Research, 2010. p. 137-157. [ Links ]

TOBIN, Mollie; LIETZ, Petra; NUGROHO, Dita (Anindita); VIVEKANANDAN, Ramya; NYAMKHUU, Tserennadmid. Using large-scale assessments of students’ learning to inform education policy: insights from the Asia-Pacific region. Melbourne: ACER; Bangkok: Unesco, 2015. [ Links ]

VALLE, Raquel da Cunha. Teoria da resposta ao item. Estudos em Avaliação Educacional, n. 21, p. 7-92, 2000. https://doi.org/10.18222/eae02120002225 [ Links ]

VIANNA, Heraldo Marelim. Avaliação educacional: teoria, planejamento, modelos. São Paulo: IBRASA, 2000. [ Links ]

WORLD BANK. Mozambique: Student Assessment. Systems Approach for Better Education Results (SABER) country report. Washington, 2009. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/246021468321879999/pdf/ [ Links ]

HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE BAUER, Adriana. Large scale assessment and establishment of educational goals and indicators: uses and abuses of quantophrenia. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, v. 40, e94095, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-0411.94095

1Based on the 2009 Eurydice report, the present author states that only five countries do not have a proposal for large-scale external assessment, namely: the Czech Republic, Greece, Wales, Liechtenstein and the German-speaking community of Belgium.

2A majority of European countries now use external standardized assessments at a regional or national level. Until the 1990s, only a small number of countries used national tests in compulsory education (primary and lower secondary education), either for the purposes of transition to the next year (Iceland, Portugal, Scotland, Northern Ireland, the Netherlands, Luxemburg, Denmark and Malta) or for providing diagnostic information about the education system as a whole (Ireland, France, Hungary, Sweden and the UK). Ten other countries and regions followed suit in the 1990s, including Spain, the French Community of Belgium, Latvia, Estonia and Romania. Since the early 2000s, national tests have been introduced in the Flemish Community of Belgium, Lithuania, Poland, Norway, Slovakia, Austria, Germany, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Denmark and Italy (Rey, 2010, p. 140-141).

3In 2019, in the second edition of Pasec, the number of countries had already risen to 15: Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Congo, Ivory Coast, Gabon, Guinea, Madagascar, Mali, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Senegal, Chad and Togo.

4The IDEB is calculated from two components: school performance rate (approval) and performance averages in standardized exams applied by the National Institute of Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira (INEP). The approval rates are obtained from the School Census, and the performance averages used are those of Prova Brasil (for schools and municipalities) and SAEB (in the case of the states and national), all produced by INEP.

5The data used in the present paper were obtained from two studies entitled “Assessment and educational management in Brazilian municipalities: mapping and characterization of ongoing initiatives”, and “Relationships between assessment and educational management in Brazilian municipalities: a study in ten municipalities of the federation”. The former study was developed through a partnership between the Fundação Carlos Chagas (FCC) and Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais - Anísio Teixeira (INEP), under the coordination of Adriana Bauer and João Luis Horta Neto, with financial support from FCC and INEP. The latter study received financial support from FCC, INEP and the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP). The considerations expressed in this paper are the sole responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily express the opinions of those who participated in the research.

6At the time of the research proposal, it was not possible to obtain the electronic address of 38 municipalities, which is why they were not contacted to participate in the study.

7Trying to understand the nature of these initiatives and their relationship with the educational network’s management process was beyond the limits of the present study, although it was a very pertinent question to help us understand how educational networks understand and appropriate external assessment.

8The objectives that were proposed as alternatives to the issue were inspired by discussions in the relevant literature, especially Bauer (2010) e Brooke e Cunha (2014).

9An allusion to the term used by the Russian sociologist Sorokin in the mid-20th century to explain the excessive appeal of the quantitative and measurable aspects of phenomena, determined by the psychological and social sciences, which reduced knowledge to what can be observed and measured.

10The differentiation between assessment and measurement has been the subject of attention by numerous researchers in the field and can be found in the works of Vianna (2000).

11The 2014 National Education Plan established, among several strategies, the need to establish, by 2016, a common national curriculum base, to serve as a curricular reference for all entities of the federation. This basis, approved in December 2017, establishes a common part of knowledge and skills, called learning rights, to which all students must have access, in addition to guiding principles for the elaboration of a diversified part.

Received: January 25, 2024; Accepted: August 12, 2024

texto em

texto em