INTRODUCTION

Teaching in multigrade classrooms is a practice in which students of different ages, abilities and degrees of educational advancement share the same classroom (Engin, 2018; Fernández-Morante et al., 2023; Ávila-Meléndez, 2024). Curiously, while in developing countries or in regions with difficult or complex social, cultural, political or economic problems, it has been seen as a contingency solution, especially in rural areas (McEwan, 2008; Morton and Harmon, 2011), in developed countries or with more consolidated educational systems, it is presented as an innovative pedagogical alternative with multiple pedagogical attractions (Hyry-Beihammer and Hascher, 2015).

In this regard, Little (2006) states that, despite being such a widespread model, teaching in multigrade classrooms turns out to be limited in pedagogical strategies that allow teachers to be supported in their teaching work, taking into account the particularities of the students in this type of classroom.

In the Latin American context, despite its particularities, it is possible to find common or similar causes related to multigrade classrooms in different geopolitical contexts (Hargreaves et al., 2001). In this sense, Rodríguez (2009) points out that multigrade and single-teacher schools correspond to more than 70% of primary schools in Peru, as a result of a systematic limitation in public spending on education, especially in areas with poorer populations.

Related to this, Galván Mora (2020) indicates that, despite the initiatives promoted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in Mexico in terms of reducing the number of multigrade schools in favor of schools with a higher concentration of students and different teachers per grade, the teaching community has begun to vindicate multi-grade classrooms based on the protection of ancestral or rural knowledge. Now, in Colombia, as a product of the recent history of the country in relation to the phenomenon of violence, the increase in multigrade classrooms has arisen closely linked to a strong migration process.

In this sense, Martínez-Restrepo, Pertuz and Ramírez (2016), point out that the enrollment in secondary education in rural areas is 68%, illiteracy in those over 15 years of age is 12.5%, and the rate permanence in the educational system is 48%, added to the above, 5% of the population in Colombia is in a situation of forced displacement and 13% live in border areas.

These circumstances, added to displacement due to causes associated with working conditions, especially in rural areas of the country, have led to the graduation rate of students for secondary education reaching only 55.7% (García, Maldonado and Jaramillo, 2016). At this time, official sources indicate that Colombia has 17 thousand rural schools, a good part of which, close to 50%, work with multigrade classrooms and serve the population in conditions of vulnerability (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2004; 2016).

From another perspective, some authors such as Bustos Jiménez (2007) do not conceive multigrade classrooms only as an educational solution to a population problem, but as an educational alternative with great potential to face the complexity of the interactions between teachers and students of different levels. In this regard, it is suggested that multigrade classrooms strengthen social relationships, reduce the presence of aggressive attitudes, promote positive coexistence and intergenerational tolerance, focusing on a requirement centered on the capabilities of each individual and not on the relationship of their age with that of the rest of their classmates (Rosas, 2009).

However, as Santos (2001) mentions, the initial experiences in multigrade classrooms are presented as negative, since the teacher usually focuses first on the difficulties observed. As progress is made in understanding the potential of multigrade classrooms, they gradually begin to emerge as one of the main pedagogical potentialities for collaborative learning, based on organizational rules and positive interactions, where students create metacognitive processes to encourage the formation of relationships and solid learning networks as a starting point for the construction of one's own knowledge (Boix Tomàs and Bustos Jiménez, 2014).

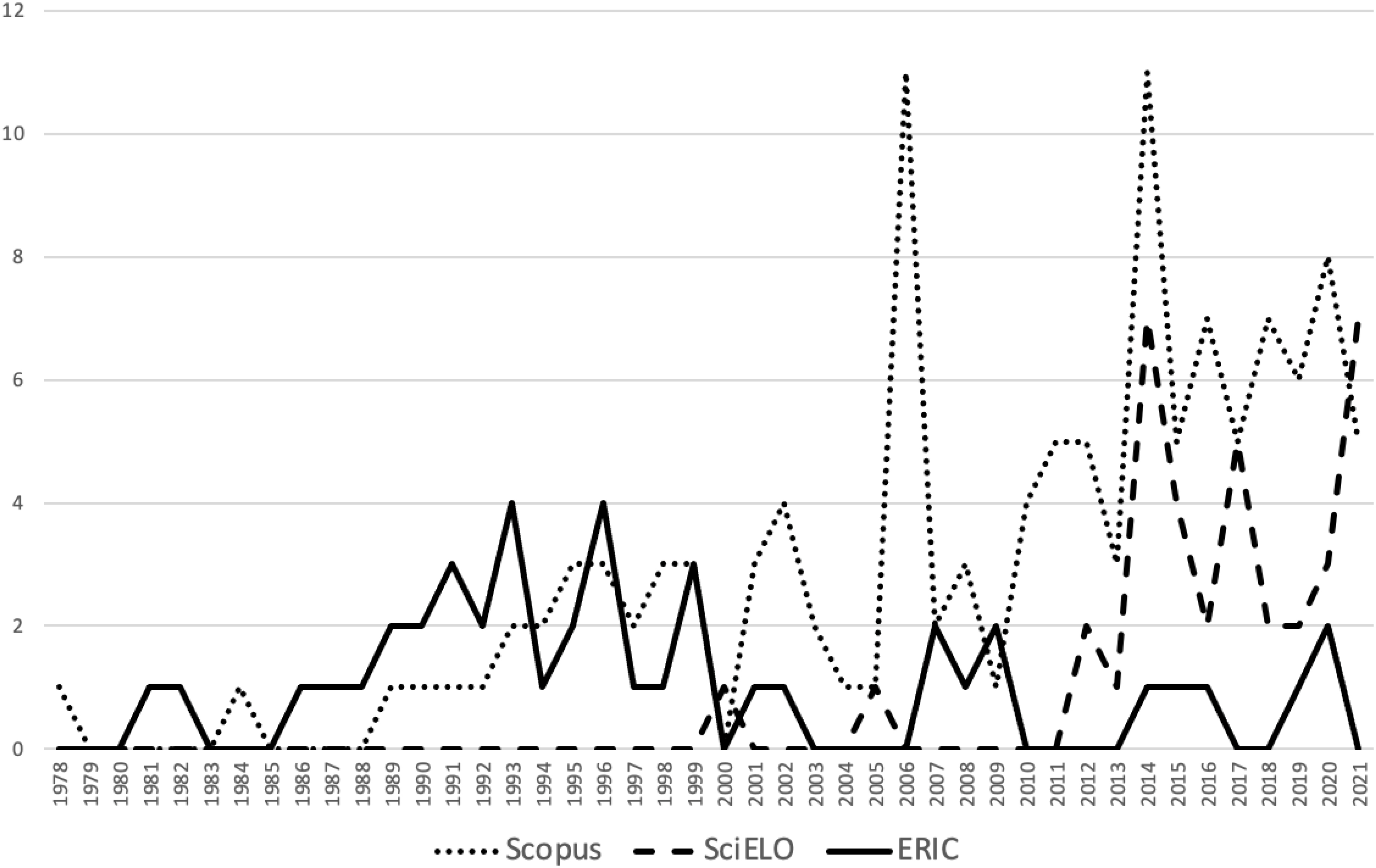

From the point of view of research, multigrade classrooms are still a field of knowledge to be explored. Although its implementation can be traced in practice for several decades, the studies published in this regard in peer-reviewed scientific journals, as can be seen in Figure 1, reflect barely incipient research on this matter with a very low average of publication of articles per year (n=2.8) and a maximum of publications in the years 2006 and 2014, with just only 11 articles per year.

Source: own elaboration (2024).

Figure 1 Publications on multigrade classrooms in the last 20 years.

On the other hand, as mentioned above, the context of implementation of multigrade classrooms makes it difficult to articulate them with educational integration processes of information and communication technologies (ICT) (Hasin and Nasir, 2021; Rana, Greenwood and Henderson, 2021; Guo et al., 2022; Carrete-Marín and Domingo-Peñaf Iel, 2023), which would lead to thinking about potential disadvantages based on the demands and challenges of education in the 21st century (Kum Yoke et al., 2020; Peña-Ayala, 2021). In that order of ideas, it is worth mentioning that such technological integration is not carried out in a single way; on the contrary, under different conditions of time, mode and place, it generates different types of learning experiences, which in turn configure several educational scenarios to be explored from the perspective of multigrade classrooms.

Within these scenarios, the following stand out: face-to-face learning supported by ICT, blended learning, e-learning, m-learning or learning mediated by mobile devices and, lastly, massive open online courses (MOOCs), which are free learning spaces, open to anyone through the internet and massive in terms of the large number of simultaneous or concurrent participants they support compared to other types of online classes (Koukis and Jimoyiannis, 2019).

Regarding the above, and specifically face-to-face learning supported by ICT, Adegbenro and Olugbara (2018) indicate that, in this scenario, technologies are not able to substantially transform the logics neither the dynamics of traditional classes, although some of its communicative components and of access to information become more efficient and durable.

On the other hand, learning experiences framed in blended learning are characterized by being carried out in a synchronized scheme of two complementary dimensions: face-to-face and virtual (Dziuban et al., 2018; Geng, Law and Niu, 2019). Unlike blended learning, e-learning experiences do not contemplate face-to-face interaction spaces; the learning process takes place entirely in digital environments in a varied combination of synchronous and asynchronous activities (Lagman and Mansul, 2017; Pham et al., 2019).

As can be seen so far, any of the three previous scenarios develops in a special way when technological mediation is carried out with mobile devices, which configures a highly flexible learning process in time and space called m-learning (Iqbal and Bhatti, 2017; Kusumastuti, Tjhin and Soraya, 2017). MOOCs appear where learning is conducted through collaborative technologies and adaptation, and sharing and re-mixing activities are favored, which leads to generating learning experiences in which it is possible to interact with a very large number of peers in spaces with free access to information (Abu-Shanab and Musleh, 2018).

Now, given such a diversity of possible learning experiences generated by the integration of ICT, it is worth asking about the way in which multigrade classrooms could be effectively articulated in them and thus manage to insert themselves adequately in the path of transformation of rural education towards the expectations of the 21st century.

Thus, as education increasingly integrates digital technologies, the potential role of artificial intelligence (AI) in addressing the challenges of multigrade classrooms is an emerging area of interest. Like the broader integration of ICT, the use of AI-powered tools in multigrade settings presents both opportunities and obstacles. On one hand, AI could enable more personalized learning, intelligent tutoring, and enhanced collaboration among students of diverse ages and abilities. On the other hand, the complex social and pedagogical dynamics of multigrade classrooms may pose unique hurdles for the effective deployment of AI-based technologies. Navigating this landscape will require close collaboration between technology developers, education researchers, and experienced multigrade teachers to ensure AI is leveraged in ways that truly empower learning and teaching in these unique educational environments.

For the purpose of addressing the possible relationships between multigrade classrooms and ICT educational integration processes, a systematic review of the literature on studies on this type of classroom has been carried out, with an approach focused on the identification of convenient and relevant teaching strategies.

METHOD

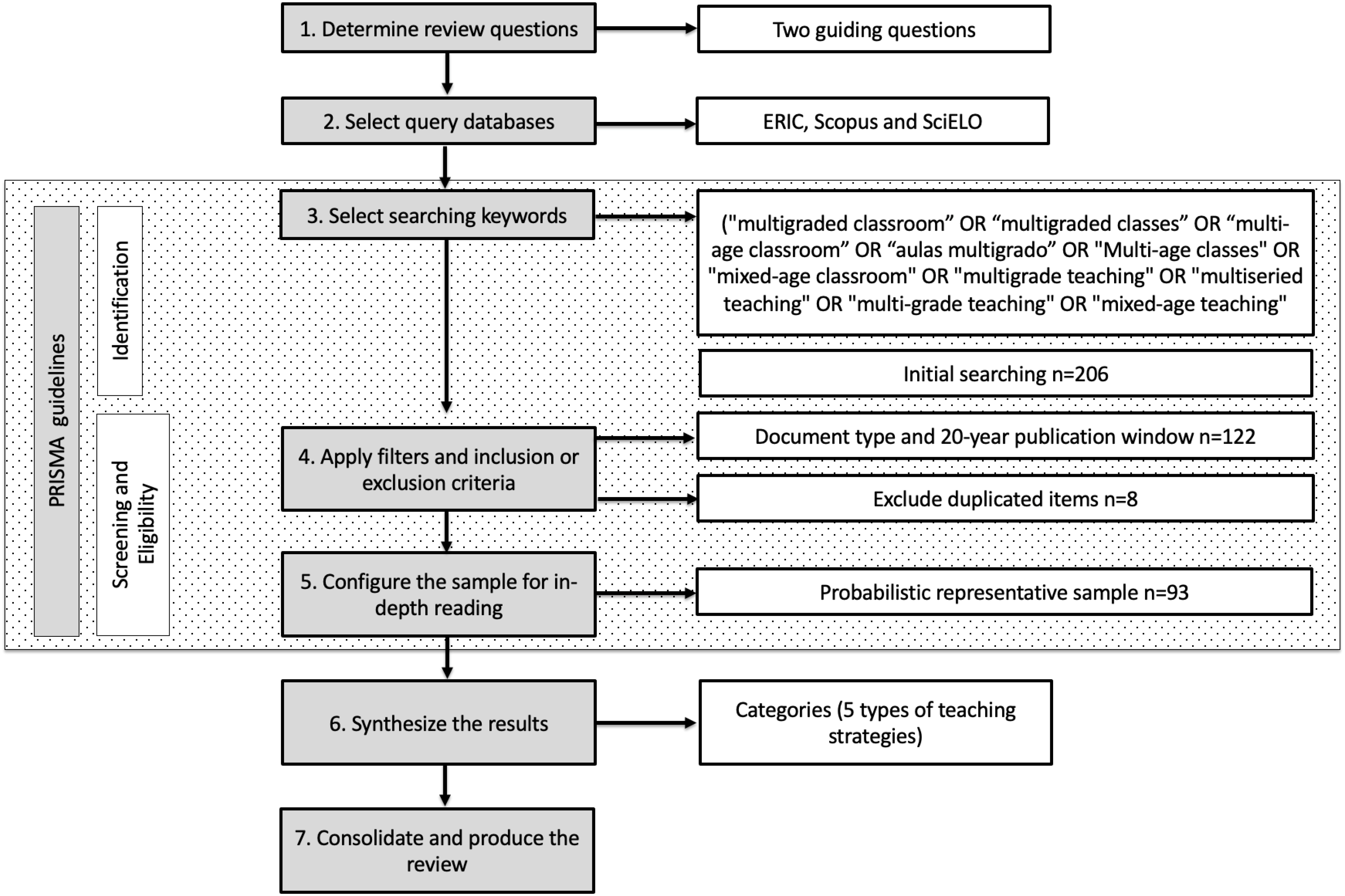

To structure the systematic review of the literature, the seven steps proposed by Fink (2013) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed, which determine a systematic, explicit and reproducible method that allows addressing the existing literature on a certain topic; in this specific case, teaching strategies in multigrade classrooms. Such steps are shown in Figure 2.

Source: own elaboration (2024).

Figure 2 Methodological steps for the elaboration of the systematic review.

DETERMINE REVIEW QUESTIONS

Taking into account the general purpose of conducting a review as explained above and doing it in a consistent and orderly manner, the following guiding questions were determined: What teaching strategies predominate in multigrade classrooms? Which of them make use of digital technologies for educational purposes?

SELECT QUERY DATABASES

In this step, the sources of information were defined according to the interest of the research and with the purpose of having a wide and varied sample on the object of study. In accordance with the above, the following databases were selected: 1. Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), as a specialized source in the educational area; 2. Scopus, as a source of wide coverage studies published in high impact journals, mainly in English; and 3. SciELO, as a source of studies published in Spanish and with relevant geographic coverage on the Latin American context.

SELECT SEARCHING KEYWORDS

Taking into consideration that multigrade classrooms are conceived and named in different ways, it was necessary to carry out a process of homologation of terms and their identification in the main international thesauri. This led to the following string of search terms: ("multigraded classroom" OR "multigraded classes" OR "multi-age classroom" OR "aulas multigrado" OR "multi-age classes" OR "mixed-age classroom" OR "multigrade teaching" OR "multiseried teaching" OR "multi-grade teaching" OR "mixed-age teaching"), which was applied in the fields "title", "abstract" and "keywords" in the three databases selected.

An initial search of this chain yielded the following results: 123 documents in Scopus, 43 documents in ERIC and 40 documents in SciELO, for a total of 206 documents as the basic documentary corpus.

APPLY FILTERS AND INCLUSION OR EXCLUSION CRITERIA

After having carried out the initial searches, the first inclusion/exclusion criterion, related to the type of document, was applied, specifically limiting results to articles with research findings. For this purpose, this filter was applied directly to the databases accompanied by an abstracting process.

The second criterion for inclusion or exclusion of filter texts was date of publication, where a publication window of the last 20 years was taken into account, due to the general accentuation in the educational use of ICT in Latin America. In this way, the search was significantly reduced to a total of 122 documents. As part of the application of PRISMA guidelines, in this process eight duplicate items from the different databases were eliminated.

CONFIGURE THE SAMPLE FOR IN-DEPTH READING

Taking into account the results of the initial filtering and abstracting process, a probabilistic and representative sample was generated with a confidence level of 95% and a 5% error. In this sense, the final sample was composed of 93 documents, which were proportionally distributed among the three databases.

SYNTHESIZE THE RESULTS

Before starting the synthesis process and to systematically conduct the extraction of information from the selected articles, the classification of teaching strategies proposed by Barriga Arceo and Hernández Rojas (2002) was used. They indicate that the teaching strategies can be ordered according to their purpose, in the following way: 1. those that seek to activate previous knowledge, 2. those that seek to orient and guide the relevant aspects of the learning content, 3. those that seek to improve the coding (elaborative) of the information to be learned, 4. those that seek to organize new information to be learned, and 5. those that seek to promote the link between prior knowledge and new information to be learned.

In order to synthesize this information, a data matrix was created which allowed the information extracted from each article to be stored and documented in small segments and relevant information from each article. Based on the data stored in the matrix, an analysis of frequencies and a process of homologation of terms and grouping (coding) were carried out.

CONSOLIDATE AND PRODUCE THE REVIEW

During this final stage, the process of writing the results of the review was carried out after data analysis in the previous step, which was structured based on the classification of the teaching strategies mentioned above, as categories of analysis. In detail, each of the articles was segmented and coded separately according to these categories, with the purpose of identifying the strategies and the use of ICT, if any.

RESULTS

From the bibliographic point of view, the results were displayed homogeneously in 59 journals. The quality of the consultation sources is referenced from the impact factor of the journals that published the studies that made up the review documentary corpus. Table 1 shows the Top 10 indexed journals that published studies related to multigrade classrooms, their impact factor and classification quartile in SCImago Journal Rankings (SJR).

Table 1 Top 10 magazines with publications on multigrade classrooms.

| Journal name | SJR Impact factor | SJR Quartile |

|---|---|---|

| International Journal of Educational Development | 0,755 | Q1 |

| International Journal of Educational Research | 0,923 | Q1 |

| Asia Pacific Journal of Education | 0,467 | Q2 |

| Educational Gerontology | 0,366 | Q2 |

| International Journal of Learning | 0,106 | Q4 |

| Revista Mexicana de Investigacion Educativa | 0,270 | Q3 |

| Teaching And Teacher Education | 1,945 | Q1 |

| Advances In Research on Teaching | 0,184 | Q4 |

| Aera Open | 0,856 | Q3 |

| Canadian Journal of Education | 0,233 | Q4 |

Source: Scopus (2024).

TEACHING STRATEGIES IN MULTIGRADE CLASSROOMS

Figure 3 shows the consolidation of the results based on the five types of teaching strategies proposed by Barriga Arceo and Hernández Rojas (2002), which were taken as the analysis categories of the literature review.

In general, there is a very marked emphasis on strategies aimed at guiding relevant aspects of learning content, followed by activation of prior knowledge. The rest have a low and similar level of occurrence (6 and 7%).

STRATEGIES TO GUIDE LEARNERS ON RELEVANT ASPECTS OF LEARNING CONTENT

According to Agran et al. (2001), these are the strategies that the teacher or instructional designer uses to guide and provide an adequate learning environment. They also work to help maintain and guide the attention of students during classes. In this sense, strategies of this type are preferably proposed as co-instructional strategies, that is, they are strategies that permeate most of the school day, which are applied after the start of class activities and before its completion. Its approach focuses on indicating to students the main concepts or ideas, in a way that allows them to focus their attention and coding processes, in addition to establishing rules to generate appropriate behaviors or habits in class. In this regard, this type of strategy is related to the concept of "classroom climate", which is defined as the learning environment that the instructor creates through teaching (Peters, 2013).

Given the conditions in which multigrade classrooms arise, which often turn out to be environments with complex social and economic problems and even areas with geographical access difficulties, it is not surprising to find that these types of strategies turn out to be among the most common, since students have difficulty following orders and instructions or behavior guidelines that are appropriate for a school environment. As Cheema and Kitsantas (2016) explain, these strategies take into account relationships between different variables, such as motivation, student interests, and prioritizing attention focus activities.

The foregoing statement becomes visible in the educational proposal of Alzate Mejía (2009), where through the so-called "human ecology", this being the study of the relationships between human beings and their environment, the "classroom climate" is regulated. This implies the development and transformation of the students themselves and the environment in which they interact, which in turn implies proposing rules and care guidelines about the student's environment, from their intra and interpersonal objectives, with the purpose of learning to care for affective niches that could be affected by external factors.

For his part, Toro Jiménez (2011) focuses on the creation of safe environments, since the study focuses on children who were victims of armed conflicts. In this study, teachers, according to the differences in age of the class group, find strategies that seek to generate the opportunity to live in an interpersonal environment of respect and mutual support, where affectivity plays a highly relevant role in learning. In this strategy, the regulation of the classroom climate is also observed and the class is oriented based on the relationships of the students, not only those between peers or teachers, but also the relationships established with their environment, through the creation or transformation of the immediate context.

STRATEGIES TO ACTIVATE PRIOR KNOWLEDGE

These types of strategies, so often associated with meaningful learning, are essential to formally integrate the knowledge that students acquire in their daily lives or in their immediate context (Márquez Valderrama, 2008). In this regard, the activation of prior knowledge supports two purposes in the teaching process: to be clear about what students know and to use said knowledge as a basis to promote new learning (Chen, Wong and Wang, 2014).

An example of the above is raised by Souza (2012), where the recognition of daily experiences and previous knowledge of the students was very useful to coordinate activities and content for children of different ages, even when some of them did not have basic reading and writing skills. Narrative is often used in these strategies to approach the development of basic literacy.

Hennessey (2010) affirms that prior knowledge can be a key element to maintain motivation in students and develop their creativity. In addition, Capellán-Ureña et al. (2022), point out the importance of this type of strategy, mainly for mathematics learning, where the teacher guides the objectives based on the student's knowledge, ensures that the purposes of the class are known in advance and through processes of observation, comparison, deduction or generalization, inducing them to reach conclusion processes.

Another interesting result that includes the use of teaching strategies leveraged on previous knowledge is proposed by Núñez (2011), where, based on productive projects aimed at teaching crop management techniques and the raising of domestic animals, an educational practice close to the context and knowledge of the students, so that in addition to generating strengthening in this learning, it was possible for the older children to serve as tutors for the younger ones thanks to their own experience.

STRATEGIES TO IMPROVE THE (ELABORATIVE) CODING OF THE INFORMATION TO BE LEARNED

These are strategies that aim to provide the student with the opportunity to carry out a complementary or alternative coding to the one exposed by the teacher. In this way, the new information is enriched based on the context, resulting in a greater elaboration so that learners assimilate the information better (Babaci-Wilhite, 2017).

For this type of strategy, the key concept is contextualization, which involves not only considering students’ ideas but also valuing the experiences they bring to the classroom, making the approach culturally relevant. Examples of this are proposed by Sánchez Tapia, Krajcik and Reiser (2018) or Karaçoban and Karakuş (2022), where students also bring with them all kinds of behavior patterns and knowledge from their environment, such as traditions and social structures that make these ideas meaningful to them.

These strategies turn out to be uncommon in multigrade classrooms, largely due to the lack of use of the context (referring to the adaptation of the physical space and contextualized material), as a viable agent to generate significant experiences.

An example of the above can be found in Millán et al. (2017), who present a study on some Mapuche communities of schools in the Ninth Region of La Araucanía in Chile, where difficulties are evident in preserving essential characteristics of the said culture. In this type of circumstance, teachers find these strategies particularly useful to carry out contextualized practices in their multigrade classrooms. As a result of this type of experience, the importance of integrating into the classroom relevant aspects that govern daily life such as beliefs, traditions, festivities, forms of work, social and family organization, linguistic uses, and interactions between the members of the community is evident (Schmelkes, 2008).

This is also visible in the study by Kuyini et al. (2016), who find patterns in some successful experiences in in Ghana, among which the use of culture, idioms and traditions often arises as a fundamental axis in the articulation of curricular contents that turn out to be more meaningful to students.

STRATEGIES FOR ORGANIZING THE INFORMATION TO BE LEARNED

According to Atapattu, Falkner and Falkner (2017), these strategies allow giving greater organizational meaning and structure to the information, representing it graphically or in writing. In this way, an adequate organization of the information to be learned is promoted, allowing the student to rank and categorize it to facilitate its understanding.

These types of strategies turn out to be rare in multigrade classrooms, where the use of graphic organizers or ordering of information is not considered as part of the routines or essential processes within the classroom. However, as mentioned by Ramírez et al. (2012), the correct management of information is a fundamental tool for decision making, organization and structure of the class, evaluation, identification of errors and control of learning processes. Despite their low frequency, these types of strategies are considered essential in good teaching practice in a multigrade classroom, which is why they are often carried out from specific activities that are not always framed in a consistent strategy.

The foregoing is found in the investigations of Bustos Jiménez (2007) and Corbatto (2017), where the pedagogical importance of graphic organizers in multigrade classrooms is highlighted to generate metacognitive processes, which help to focus attention on the learning processes of each individual, eliminating the tension that sometimes emerges from designing strategies that work for an entire group.

On the other hand, Gutiérrez Serrano (2017), from the context of rural education in Mexico, hints at how the use of strategies that allow organizing information turns out to be fundamental for some teachers, since not having a model as a reference that would allow articulating and guiding the class helps them to give meaning and structure to the contents that are addressed.

STRATEGIES TO PROMOTE THE LINK BETWEEN PRIOR KNOWLEDGE AND NEW INFORMATION

According to Morales Urbina (2009), these are strategies that aim to create or strengthen adequate links between prior knowledge and new information, ensuring more meaningful and coherent learning. These strategies are often related to the use of analogies or comparative charts.

For Braasch and Goldman (2010), analogies can be seen as a process of identifying similarities between two objects, processes or systems for explanation or extrapolation purposes. The use of analogy in teaching practices is often used in the construction of knowledge to create ways that allow students of different ages to visualize abstract concepts using context and language that is familiar or understandable (Mukwambo, Ramasike and Ngcoza, 2018).

It is worth mentioning that, since these strategies are complementary to the activation of prior knowledge, their mention in the studies reviewed is quite low and they focus mainly on the use of texts, comparative tables or contextualized material (which serve as a basis for analogies), through which the relationship of prior knowledge with new knowledge is facilitated.

This is evidenced in studies such as those by Schuh, Kuo and Knupp (2013) Boix Tomàs and Bustos Jiménez (2014), and Carrete-Marín and Domingo-Peñafiel Iel (2022), where a reference is made to the need for textbooks and printed materials that are contextualized to the didactic reality, containing analogies or comparisons that allow clarity and establish logical relationships between concepts.

In these spaces, the linking of knowledge is complex, this is due to the fact that previous pieces of knowledge, whether those coming from interaction with the environment or those obtained in school spaces, are hardly related to each other. For this reason, the use of comparative tables in this type of strategy, as evidenced by Suárez Díaz, Del Pilar Liz and Parra Moreno (2015), helps to provide greater clarity, in addition to making evident the links or relations between the different concepts.

USE OF INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY IN MULTIGRADE CLASSROOMS

Only 5.6% of the studies reviewed reported the use of ICT to support teaching strategies in multigrade classrooms, due to the aforementioned conditions, in which these classrooms usually operate. In this regard, experiences such as those presented by Aksoy (2008), Laura and Bolívar (2009) or Fargas-Malet and Bagley (2021) stand out, among which the complementary use of problem-based learning and interactive television or technological resources installed in classrooms as a means and central axis in the development of classes. In addition, it is worth mentioning that in almost all classes it was found that the use of ICT was restricted to generic devices such as laptops or computers for information query tasks.

However, as Severiano Sánchez (2013) mentions in his study on the use of technology in multigrade classrooms, when activities were proposed to obtain information from different sources, this was not limited to just a query task; rather, such activities enabled analysis and evaluation processes, taking advantage of technological tools to generate, demonstrate and socialize the students’ learning.

In this regard, it is worth mentioning that ICTs present a series of advantages for students, such as: the new possibilities of interaction, by means of which students change from a passive role in learning to an active role of construction and discovery, a search for critical information, the continuous rethinking of content and procedures, increased involvement and motivation in tasks and proposed activities (Mendoza Torres, 2014; García-Valcárcel Muñoz-Repiso, 2016).

On the other hand, initiatives such as those reported in Santos (2001) and Flores and Albarrán (2008) are to be retrieved, in which ICT-supported models are applied—for example, the Telesecundaria model, which makes use of various learning and teaching strategies, whose fundamental axis is the use of educational television aimed at children and young people in rural areas where there are often multigrade classrooms and the main objective is to continue and complete basic secondary education.

In addition, as mentioned by Rayón, Las Heras Cuenca, and Muñoz Martínez (2011), it is not enough to use platforms and technological tools, but guidelines for pedagogical use that are consistent with the complexities of the multigrade classroom must be established; that is, models that value the management of knowledge and learning in a flexible way, that encourage student autonomy and the formation of learning communities.

DISCUSSION

A look at the results of the review could lead us to address a first reflection on the tension between the relevance of multigrade classrooms based on the learning context and their effectiveness in terms of the academic performance of the students who participate in them. Although various studies (Kos, 2021; Munser-Kiefer et al., 2021; Shareefa, 2021) report that multigrade classrooms present comparatively lower results than traditional multi-teacher schools, one might wonder to what extent it would be necessary to use other strategies or incorporate other technologies with the purpose of strengthening this form of teaching, especially in rural education (Gaviria Arias, 2017).

In this sense, like many other educational initiatives that are deployed in this century, multigrade classrooms should not be oblivious to the integration of digital technologies; however, evidence shows that there is no greater tradition of technological integration in them.

In this regard, as mentioned by Harmandaoğlu, Balçikanli and Cephe (2018), the use of ICT offers possibilities for change in teaching practices and teaching forms. However, its integration in school environments poses a series of challenges, which in turn are almost insurmountable in most of the places where multigrade classrooms arise. This is largely due to isolation and lack of resources. In fact, a good part of the strategies that have been applied in these classrooms have been designed for a face-to-face context and would not make much sense in a context highly mediated by technology.

As an example, it should be remembered that the purposes of using these strategies, especially the most used according to this review, are especially related to motivation and regulation of the classroom climate, which makes much sense in the context of a face-to-face class. However, if the multigrade classroom is held in a non-face-to-face learning environment, highly mediated by ICT, such as e-learning, MOOCs or even m-learning, these strategies do not have the same meaning and impact, since, in remote or distance contexts, what we know as the "class group" or the "classroom climate" manifests itself in a totally different way.

In this case, it would be necessary to reconceptualize such concepts and try to recognize their practical implications, which are assumed to be very different from those related to traditional concepts. In this sense, teaching strategies should focus on ensuring individual concentration and motivation processes for long periods of time for remote or distributed work conditions (Kirova, Boiadjieva and Peytcheva-Forsyth, 2012).

However, it is not in all cases unfeasible to integrate ICT into multigrade classroom experiences. Examples such as those of Fang (2002) and Nedungadi, Jayakumar and Raman (2014) show the feasibility of transferring this type of experience to an m-learning scenario, in which the possibility of complementing the different methodological strategies (such as those that promote the link between prior knowledge and new information) with others (such as information organization) based on the use of mobile devices that allow reinforcing or generating other complementary, personal or collaborative learning spaces.

On the other hand, it was found that the strategies aimed at improving the coding of the information to be learned turned out to be scarce in multigrade classrooms, due largely to a lack of clarity regarding the importance of context to promote deep relations between teaching and learning. In that order of ideas, in e-learning processes or even in m-learning experiences, these types of strategies turn out to be very appropriate, since some electronic devices offer the possibility of capturing or carrying out activities that enable students to be closer to their immediate context, allowing a direct and experiential link to be established with new knowledge, and thereby fostering a sense of appropriation, self-learning and self-management (Çevik and Duman, 2018).

It is also necessary to mention that, although there are many paradigms around the use of ICT in education, especially with regard to its potential to generate collaboration, thinking of multigrade classrooms that are developed in digital environments might make us consider the possible richness in terms of feedback. This is because students of different grades and ages could share spaces for digital collaboration, more so if they come from different contexts and different domains, both technological and in terms of areas of knowledge.

Based on the results found in this review and considering the previous reflections, various spaces are opened for educational practice and research on these issues, especially focused on developing and exploring ways in which the strategies that are usually applied to face-to-face multigrade classrooms could or should be transformed or replaced by others that are more relevant to the demands and characteristics of digital teaching and learning environments.

Looking to the future, as education increasingly leverages AI and other advanced technologies, the challenges faced by multigrade classrooms may become more pronounced. AI-powered learning systems, for example, are often designed for more homogeneous classroom environments, and may struggle to cater to the diverse needs and abilities present in multigrade settings. Similarly, AI-enabled virtual assistants and chatbots may not be able to effectively manage the complex social and pedagogical dynamics of multigrade classes. However, the integration of AI in multigrade classrooms also presents opportunities. Thus, AI-powered tools for content personalization, real-time assessment, and intelligent tutoring could help teachers better cater to the varied learning needs of students (Kim et al., 2023). Besides the above, AI-enabled collaboration platforms could facilitate peer-to-peer learning and knowledge sharing across age and ability levels, and AI-driven analytics could provide teachers with deeper insights into students’ progress and challenges, informing more targeted instructional strategies, which is, by the way, a very critical issue in multigrade classrooms.

FUTURE RESEARCH SHOULD PRIORITIZE SEVERAL KEY DIRECTIONS

Firstly, empirical studies are needed to evaluate the impact of integrating AI-powered technologies in multigrade classroom settings. These studies should examine their effects on student learning outcomes, engagement, and teachers’ pedagogical practices. Design-based research is also essential to develop AI-enabled learning systems and collaboration platforms tailored for the unique needs and constraints of multigrade classrooms. This process should involve multigrade teachers in the iterative design and evaluation process. Also, ethnographic investigations can provide valuable insights into the social, cultural, and organizational dynamics of multigrade classrooms, helping to understand how these factors shape the potential application of AI and other digital technologies. Furthermore, comparative analyses of multigrade classroom experiences in different geographical and socioeconomic contexts can identify common challenges and successful strategies for technology integration that could be shared across communities.

Finally, studies on the professional development needs of multigrade teachers in the era of AI and advanced educational technologies are crucial, mainly because the importance of understanding how best to prepare them to effectively integrate these tools into their instructional practices is vital for successful implementation. By pursuing research along these lines, the education community can better understand how to harness the power of AI and other emerging technologies to address the unique needs and challenges of multigrade classrooms, ultimately improving learning outcomes for students in these important educational settings.