INTRODUCTION

The teaching of neuroradiology to undergraduate medical students can be used as a tool for interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary integration within the curricular matrix of universities, introducing the development of care skills since the beginning of its use in the medical course1),(2. The early inclusion of radiology in the first semesters of the medical course has a positive effect, since this area allows the clarification of pathophysiological processes and morphofunctional alterations even during the basic semesters of the medical course1)-(6.

A major limitation pointed out by students for the fixation of knowledge in basic areas is precisely the lack of integration with medical practice2. The lack of knowledge about the possible practical applications of what is being studied generates disinterest7)-(9. Radiology, in this context, can assist in introducing clinical concepts in an introductory manner within the course, establishing a link with practical questions of everyday medical practice10.

It is increasingly common in medical courses to change the curricular matrix aiming to adopt active methodologies as the mainstays of teaching, allowing students to freely search for the necessary contents, empowering them through their own knowledge11),(12. For the method to be successful, however, it is necessary for the student to be comfortable with and trust the numerous bibliographic sources available. In addition to scientific articles and books, it is currently possible to find e-books, websites, mobile applications and even social networks. However, regarding the latter, less traditional sources, although they are often even more didactic, they also tend to raise doubts about their reliability, somewhat limiting their use in a broader way2.

In teaching practice, neuroradiology is considered a complex subject by students. Some factors may be implicated, such as neuroscience-related neurophobia8),(9),(13; the limitations in understanding the most basic aspects of radiology itself, such as Physics Applied to Medicine and the correct use of radiological terminologies2; in addition to the concept of three-dimensionality of the anatomical aspects. There is also a lack of material aimed at undergraduate students, limiting learning in the absence of a professional radiologist as a mentor, something that goes against the foundations of learning through active methodologies2.

Although much has been proposed, there are few national studies aimed at this evaluation, limiting the feasibility of solutions to possible problems. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate the students’ opinions about their difficulties with the learning of neuroradiology, aiming to support the acquisition of knowledge in this field14),(15.

The aim of this study was to analyze the perception of medical students about the challenges in the teaching of neuroradiology, including the evaluation of active methodology use in this process, allowing the construction of strategies that can stimulate learning.

METHODS

This is a cross-sectional and quantitative study, carried out through the creation of a structured questionnaire aimed at students from a private medical school located in the city of Fortaleza (state of Ceará, Brazil), using a teaching strategy centered on Problem-Based Learning (PBL), which brings pedagogical tools that stimulate students to seek knowledge, unlike the passive methodology, which consists mainly of expository classes.

The questionnaire comprised a total of 16 items and was directed to the assessment of the difficulties faced by students when studying neuroradiology. The questions included the demographic characteristics of the population and their personal perceptions about the teaching of neuroradiology in undergraduate medical school.

The inclusion criteria were: students that were enrolled at and whose attendance was greater than 75% in the semesters that included neuroradiology: the second (due to the central nervous system module) and the seventh semesters (clinical neurology) of the undergraduate medical course. The absence of this criterion was considered as the sole reason for exclusion.

The software Epi Info 7 (CDC, 2019) and Google Forms were used for the analysis and handling of the results, The numerical results were expressed as absolute and percentage frequencies and analyzed using Fisher’s exact test and Pearson’s chi-square test.

As for ethical aspects, all respondents freely decided to participate in this study, by signing the Informed Consent Form and received a copy of the document. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Centro Universitário Christus, under the co-substantiated Opinion number 3,021,673. There were no conflicts of interest on the part of the researchers.

RESULTS

In all, 181 questionnaires were analyzed, being 91 students from the 2nd semester of the medical school, who have contact with basic topics such as neurosciences and neuroanatomy; and 90 students from the 7th semester, who attend the clinical modules, such as neurology, neurosurgery and trauma. All questionnaires were used, and it was not necessary to exclude any of the students. Most students were over 20 years old (67.6%) and there was a slight predominance of women (58.6%). Most of them (65.2%) had their own cars.

Initially, five questions were asked to evaluate factors that could contribute to the difficulty in teaching neuroradiology to undergraduate students. The first two sought to investigate whether the need for basic knowledge about radiology and neuroanatomy could represent a difficulty in the study of neuroradiology. The next two questions were about the importance of integrating radiology and neuroanatomy, as well as with the practice of neurology and regarding the study of the discipline. The fifth question evaluated whether the volume of content for the short time available could be seen as a difficulty for the study of neuroradiology.

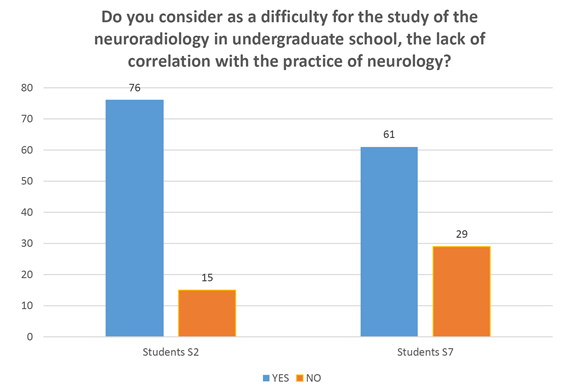

Most of the students mentioned as a difficulty in understanding neuroradiology the need to have previous basic knowledge of radiology (80.1%), knowing neuroanatomy (77.5%) and correlating radiology and neuroanatomy (70.9%). When comparing the 2nd semester and the 7th semester groups, there was a greater tendency among the students from the 2nd semester to point out the lack of practical knowledge of neurology as a factor of greater difficulty in learning neuroradiology (82.6% versus 67.4 %, with p <0.0018). These questions aimed to assess whether the students themselves had the ability to identify the role of interdisciplinary integration in their education. Moreover, most students (89.9%) pointed out the large volume of content for the short time available within the curricular matrix as a factor of neuroradiology learning difficulty.

Next, four questions were asked to assess which teaching methodologies would be preferable, in the students’ opinion, for learning neuroradiology: PBL (problem-based learning), TBL (team-based learning), expository class (passive methodology) and display of neuroradiology exams in a report workstation.

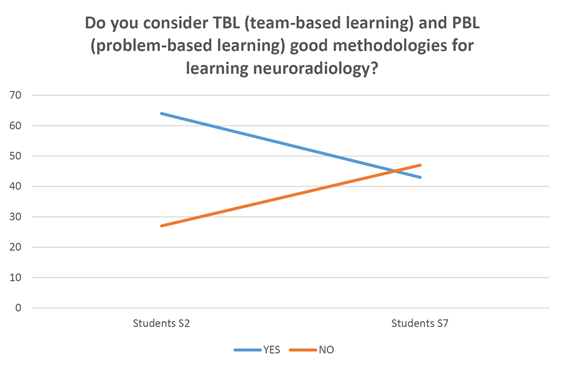

When asked whether PBL and TBL were considered good methodologies for learning neuroradiology, 2nd semester students were more likely to respond positively, when compared to 7th semester students (p <0.004), with 51.7% of 7th semester students answering that they did not consider these methods adequate for learning neuroradiology. A total of 78.2% of the students answered that the expository class would be a good methodology for learning the discipline; however there was no significant difference between the semesters. In addition, most students reported that the use of workstations with real exams (91.1%) would be useful for learning.

The next two questions aimed to understand whether an e-book and a mobile application aimed at undergraduate students could be useful in learning neuroradiology. When asked about the creation of an e-book, 85.6% of students answered affirmatively, agreeing that it could help in the study of the discipline. In the case of an application, 92.3% agreed with an expected beneficial effect.

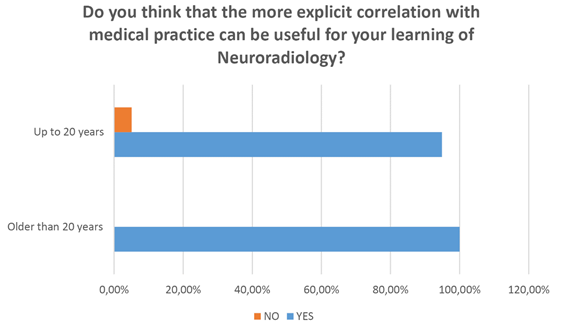

Finally, the last item sought to assess in a more incisive way whether the more explicit correlation with medical practice could be useful in learning neuroradiology. A total of 98.3% of the students answered that this correlation is useful and necessary knowledge.

DISCUSSION

The link between difficulty in understanding neuroradiology and the need to have previous basic knowledge of radiology, neuroanatomy and to correlate radiology and neuroanatomy corroborate the need for integration between these contents. These perceptions strengthen the introduction of radiology in the curricular matrix since the beginning of the medical course, in an integrated way with anatomy16),(10),(17)-(23, as well as its maintenance in the clinical cycles, together with neurology15),(19),(24)-(26.

Another critical point of these data is the lack of knowledge of the radiological bases, something that should be viewed with concern. In practice, it is observed that very often, the medical school curriculum does not have specific modules for this approach, creating an important knowledge deficit for the students, which may be resolved at the internship, or only after graduation, in medical practice, limiting the learning of numerous subjects during undergraduate school due to the lack of knowledge about radiology terminology and physical principles.

Moreover, neuroradiology can be seen as a mainstay of the active methodology teaching for learning neuroanatomy. In addition to the technical difficulties in obtaining corpses27 and the costs of an anatomy table with three-dimensional resources, it is possible to identify anatomy, physiology and pathology in vivo in magnetic resonance and computed tomography exams19),(28. A practice that has been carried out in some universities consists in the use of previously selected anonymized clinical case work lists, where all students can see the sequential images in “workstations” appropriate for reports. Moreover, the availability of online anatomy atlases brings the students closer to the practice, without the need to be inside the anatomy laboratory. It is evident that the visualization of the images allows the practical application of multidisciplinary theoretical concepts29, being a true treatment for “neurophobia” (8),(9),(13),(19.

When comparing the 2nd semester and the 7th semester groups, there was a greater tendency to point out the lack of practical knowledge of neurology by the students of the 2nd semester as a factor of greater difficulty in learning neuroradiology. This situation is pointed out in the literature as a limiting factor for the fixation of content. One solution to this issue is precisely to introduce some points of the neurological clinic in an associated manner, avoiding the lack of interest in the topic because there is no connection with practical applications8),(9),(13.

One point that deserves to be highlighted is the detailed choice of the fundamental neuroradiology and neurology content for undergraduate school, something that deserves to be discussed inside and outside the universities, since the introduction of these subjects as early as in the basic cycle must be stimulated for greater fixation of this content. (8),(9 Sporadic meetings on curriculum analysis, including coordinators, teachers and students from different years in undergraduate school, could bring a meaningful discussion on how to proceed in the construction of contextualized content. Also, bringing students closer to the institution and among teachers themselves allows a greater integration of medical content, both horizontal and vertical, facilitating the learning of neurosciences.

It is worth highlighting the opinion of recently graduate medical professionals working in emergency rooms and in basic health units, which can bring important contributions for the restructuring of a more practical and coherent curricular plan inside the universities. Although it is quite challenging to maintain ex-students close by, it is believed that the benefits of university curriculum self-assessment would be considerable.

Chart 1 Do you consider as a difficulty for the study of the neuroradiology in undergraduate school, the lack of correlation with the practice of neurology?

The greater tendency of students in the 2nd semester to appreciate the PBL and TBL methods than those in the 7th semester brought up an issue faced in the classroom environment. It can be perceived, in teaching practice, that motivation with active methodologies may decrease over the years, probably due to fatigue and repetition, as well as the large volume of the subject to be studied and, in the case of neuroradiology, the lack of educational material aimed at this group of students2. Therefore, students in the more advanced semesters have a tendency to prefer a more succint content, saving them the stress of seeking the knowledge freely offered in the literature. At this time, it is up to the university to enable students to feel more motivated in the search of knowledge, making the classroom environment an innovative moment and avoiding the repetition of teaching strategies over the years. The incentive to play and even the use of workstations with real exams can help in this process, as confirmed by most students. It is important to realize when changing dynamics is necessary, since the advantages of stimulating the empowerment of the learning protagonists are well established, understanding the pedagogical limitations of the methods at certain times 7.

Chart 2 Do you consider TBL (team-based learning) and PBL (problem-based learning) good methodologies for learning neuroradiology?

An important complaint from most students was the large volume of neuroradiology content for the short time available in the curricular matrix. It can be observed, in practice, that students go through most of the undergraduate course without adequate knowledge about the physical principles, the risks of each method, the terminology of the different exams and the practical application of test requests, something that would have a positive impact during the course if it were adequately introduced in the basic cycle2.

There was also an interest in studying with an e-book aimed at undergraduate students and/or the use of reliable mobile applications, suggesting a shortage of radiological material aimed at this group of students. The student at the beginning of the course has not yet become familiar with several medical terms and most have difficulty viewing images on different planes. Such skills can be improved with three-dimensional training, more easily available on these tools.

This result allows us to consider the use of mobile applications and e-books as good active methodologies. Such devices are highly available, being linked to smartphones and tablets, allowing quick consultations and longer study time, in addition to allowing the three-dimensional visualization of radiological structures, something that has been considered very important in the pedagogical process of radiology learning for many years30. A well-evaluated strategy in European medical institutions for the teaching of Radiology is e-Learning. It comprises precisely the use of electronic material via the internet to optimize understanding, improve skills and promote more practical experience among the students31.

It is believed that these data can necessarily be extended to a broader interpretation of possible and effective integrations within each institution. It is understood that bringing the radiologist’s daily life to the university, with the use of “workstations”, real report programs with storage of anonymized cases in work lists, can arouse greater interest in students regarding neuroradiology and, consequently, the study of neuroscience.

As for the correlation between neuroradiology and medical practice, it was practically unanimous that it is useful and necessary knowledge. This perception is clear in the literature, since radiology and clinical practice are inextricably associated8),(25),(26),(32)-(34 and the same image can represent completely different diseases. This dependence should be used as a stimulus for the early introduction of clinical cases in the initial semesters, stimulating the multidisciplinary study, both horizontal and vertical, between the semesters.

CONCLUSIONS

One can observe the need for an adequate workload of Radiology in the morphofunctional labs in the new curricular matrices, allowing basic concepts to be worked on in a more permanent manner, since, in the students’ opinion, a limitation in the learning of neuroradiology is precisely the lack of basic anatomical-radiological knowledge. It is crucial to recall the interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary role that neuroradiology plays in relation to other basic contents, adding basic anatomical and clinical knowledge at the beginning of medical education17),(22. It is up to the educational institutions to explore the real possibilities of integration, both horizontal and vertical, for better learning of neurosciences. Periodic meetings between students and teachers from different years and a closer contact between the university and the recently graduated professionals can contribute to a curricular restructuring and also to an adequate choice of the fundamental contents to be addressed throughout the course.

Neuroradiology can be seen as a teaching mainstay of the active methodology for learning neuroanatomy, both due to the technical difficulties for the acquisition of cadavers by the universities, but also because of the costs of a digital anatomy table with three-dimensional resources16),(22),(35),(36. It is possible to identify anatomy, physiology and pathology in vivo using magnetic resonance imaging and CT scans, even allowing pre-surgical planning19),(28, leading the student to integrate theoretical concepts 29 into medical practice8),(9),(13),(19.

It is necessary to introduce some neurological and neuroscience clinical aspects during the teaching of neuroradiology, so that the basic cycle students can understand the importance of what is being presented to them. Another equally fundamental point is the correlation of anatomical aspects during the teaching of neurology. These two strategies are true mainstays for the treatment and prevention of “neurophobia” (8),(9),(21),(32),(33),(36.

In the students’ opinion, previous knowledge of neuroanatomy and clinical neurology is important for learning neuroradiology, showing that multidisciplinary integration is perceived as a fundamental tool, both for the fixation of content, as well as for the arising of interest in less attractive subjects.

The creation of materials directed to undergraduate courses, such as an e-book or a mobile application focused on integrating the teaching of neurosciences is considered a good alternative to facilitate the understanding of neuroradiology, something that can reduce students’ resistance to the topic and, consequently reducing neurophobia. This result allows the assumption that, the more the real radiologist’s daily life is brought to the classroom, using lists of complete exams, visualization of images in “workstations”, the more interesting the contents of neuroradiology and related sciences will become.

This study was carried out in only one institution, which can limit generalizations.

texto em

texto em