Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica

versão impressa ISSN 0100-5502versão On-line ISSN 1981-5271

Rev. Bras. Educ. Med. vol.48 no.4 Rio de Janeiro 2024 Epub 02-Out-2024

https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-5271v48.4-2023-0301

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Suggestions from a hospital health team for professional training and preparation for pandemics

1 Faculdades Pequeno Príncipe, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil.

2 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Postgraduate Program in Medical Sciences, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil.

Introduction:

The COVID-19 pandemic provided evidence of gaps in the preparation of health professionals. The objective of this study was to know the suggestions of professionals who worked in healthcare about how to better prepare them to deal with this context.

Method:

This was an exploratory qualitative study with in-depth semi-structured interviews of diverse groups of professionals from a high-complexity teaching hospital in the South Region of Brazil. Comprehensive Sociology was used as a framework.

Results:

The suggestions for institutions that provide healthcare included greater attention to their clinical staff, with regularly offered technical training and psychological preparation programs. Suggestions for health education institutions included greater curricular emphasis on psychological aspects and comprehensive care in human health, with humanization; communication; collaborative teamwork, leadership, and management; greater theoretical and practical course load, with simulation and practice in real emergency and intensive care scenarios, in addition to contents covering crisis medicine, biosafety, bioethics when resources are scarce, and care for critically-ill patients.

Discussion:

The literature indicates that investments in permanent education programs minimize avoidable errors, improve team performance and promote professional development. In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, the need to learn self-care, communication with patients and family members and strategies for controlling and managing emotions was highlighted. With regard to technical and scientific skills to be emphasized in the presence of mass crises, topics related to biosafety and care for critically-ill patients are highlighted.

Final considerations:

The suggestions provided can contribute to better preparation of health professionals to work in pandemic contexts.

Keywords: COVID-19; Health Personnel; Teaching; Humanization of Assistance; Qualitative Research

Objetivo:

Este estudo teve como objetivo conhecer as sugestões de profissionais que atuaram na assistência à saúde sobre como melhor prepará-los para lidar com esse contexto.

Método:

Trata-se de um estudo qualitativo exploratório, em que se realizaram entrevistas semiestruturadas em profundidade com diversas categorias de profissionais de um hospital-escola de alta complexidade do Sul do Brasil. No estudo, adotou-se a sociologia compreensiva como referencial.

Resultado:

As sugestões para as instituições que prestam atenção à saúde abrangeram maior atenção a seu corpo clínico, com oferta regular de programas de treinamento técnico e preparo psicológico. No caso das instituições de ensino na saúde, houve as seguintes sugestões: maior ênfase do currículo nos aspectos psicológicos e no cuidado integral destinado à saúde do ser humano, com humanização; comunicação; trabalho colaborativo em equipe; liderança e gestão de pessoas; maior carga horária de teoria e prática com simulação e práticas em cenários reais em emergência e cuidado intensivo; aspectos relacionados a conteúdos de medicina de crise, biossegurança e bioética quando os recursos são escassos; e cuidado com pacientes críticos. A literatura aponta que investimentos em programas de educação permanente minimizam os erros evitáveis, melhoram o desempenho da equipe e promovem a valorização profissional. No contexto da pandemia de Covid-19, evidenciou-se a necessidade de aprendizagem do autocuidado, comunicação com pacientes e familiares e estratégias para controle e manejo das emoções. No que diz respeito às habilidades técnicas e científicas a serem enfatizadas frente a crises em massa, destacam-se tópicos relativos à biossegurança e cuidados com pacientes críticos.

Considerações finais:

As sugestões fornecidas podem contribuir para melhor preparo de profissionais de saúde para atuar em contextos de pandemia.

Palavras-chave: Covid-19; Pessoal de Saúde; Ensino; Humanização da Assistência; Pesquisa Qualitativa

INTRODUCTION

The Covid-19 outbreak, caused by the new coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2, began at the end of 2019 and spread globally from the beginning of 2020, being characterized as a pandemic and a Public Health Emergency of International Importance (PHEII). The pandemic surprised and affected all of humanity and required measures to control it, including hand hygiene, the use of personal protective equipment and social distancing1. More recent previous pandemics included the “swine flu”, caused by a mutation of the influenza virus subtype H1N1, which began in 2009 and spread in 20102),(3, and the Spanish flu, caused by influenza A, subtype H1N1, which began in 19184.

The lack of knowledge about various aspects related to the new coronavirus generated a lot of uncertainty and health professionals who were on the front line had to seek constantly updated knowledge to act based on evidence and best practices to provide the best possible quality of care. Given the severity and high infectivity of the disease, they suffered greater emotional and occupational stress, faced social tension, were at greater risk of becoming infected, work overload, ethical conflicts and moral suffering, anxiety disorders and depression5)-(9.

Health education had to adapt during social distancing and technological advances allowed its virtual continuation. Several studies were generated that allowed the creation of several reviews on virtual teaching during the pandemic and the pedagogical, theoretical and practical approaches for its adaptation10)-(16 and on the students’ mental health17, telehealth18)-(21 and telemedicine 22)-(28 in professional training and performance.

Fewer primary studies were dedicated to identifying other gaps in health curricula to prepare health professionals to work in pandemics29, although several manuscripts were published to improve the health professional curriculum for this context30)-(37 and on aspects of professional identity challenged by the pandemic, especially ethical dilemmas38.

Affectivity is defined as “a set of psychic phenomena that reveal themselves as emotions and feelings; the human being’s capacity to promptly react to emotions and feelings.”39 According to Ferreira and Acioly-Réigner, from Henry Wallon’s constructivist perspective, affectivity is understood as the functional domain that demonstrates different manifestations that become more complex throughout human development and that originate from a predominantly organic base until they develop dynamic relationships with cognition.40

Taking into account the need for primary studies on how training could better prepare health professionals to deal with situations such as the Covid-19 pandemic, the aim of this study was to know the suggestions of professionals who worked with patients with Covid-19 on how to better prepare them to deal with this context.

METHOD

Study design and ethical precepts

This was a qualitative and exploratory study, using Comprehensive Sociology41 as a reference, to focus on the sociocultural and economic perspective that influences the behaviors of individuals, in this case, health professionals working in the pandemic scenario. The quantitative method was used to characterize the participants’ profile.

The data presented in this study are part of a broader research project, approved by the Research Ethics Committee under number: 4,429,011, in which the meanings and impacts of the pandemic on health professionals were studied, in addition to their suggestions for better preparedness to deal with the pandemic. The research followed all ethical precepts regarding research with human beings.

Study location and population

The study was carried out in a large and highly complex teaching hospital in the city of Curitiba, state of Paraná, Brazil, a reference in clinical and surgical procedures, with a tertiary level of care, which, during the pandemic, was adapted to care for patients with Covid-19.

Those eligible for the study were professionals who worked by directly caring for patients with Covid-19 and also those who participated indirectly, whether in the reception, cleaning activities or in food planning and production. We chose to include indirect actors, taking into account that their perception would also add contributions to achieving the study objectives, as all these professionals undergo basic preparations and training, such as biosafety recommendations, to work in the hospital environment. In addition, they work in direct contact with professionals who have had health training and could bring relevant questions from their observations in their practical work. At the time of the participants’ selection, the hospital had 312 nursing technicians, 64 nurses, 17 receptionists, 34 cooks/ kitchen assistants, 22 assistant doctors (including hospitalists, ICU and emergency), 60 resident doctors, 49 hygiene assistants, 10 radiology technologists, 4 nutritionists, 3 psychologists, 13 physical therapists and 4 pharmacists.

The inclusion criteria were: being over 18 years of age and being a professional who works at the hospital. The exclusion criterion was: being emotionally shaken, unable to be approached.

The sample consisted of 20 participants and their selection was based on convenience. The hospital was asked to provide a list of all health professionals and also other professionals in each category who worked in the different hospital sectors and four assistant doctors (D) and two resident doctors (RD) were randomly selected, in addition to three nurses (N) and three nursing technicians (NT) who worked directly with patients with Covid-19 in the emergency, Intensive Care Units or Covid-19 wards, and a physical therapist (P), a nutritionist (Nut), a pharmacist (Pha), a psychologist (Psy), a hygiene assistant (HA), a kitchen assistant (K), a receptionist (R) and a radiology technologist (RT). To guarantee anonymity, the professionals were designated by the first letter of their area, and numbered, depending on the order in which the interview took place; for example, the first doctor interviewed was designated as D1.

The group consisted of more representatives of medical professionals, taking into account that they could contribute with more specific suggestions for professional training in situations such as the pandemic. It was decided to select more nursing professionals, as they spend most of their time directly caring for the patient, and who suffer the most from the emotional impacts of situations such as the pandemic8. One participant was selected from each of the other categories. Twenty professionals were invited to participate in the study, with no refusals to participate. The participants’ emotional state was assessed by the researcher, who is a doctor, at the time of the interview and none of the participants were excluded from the study due to signs of extreme suffering.

Data collection

To approach the eligible professionals, the researcher contacted them by telephone or in person, introduced himself, explained the objectives of the study, its justification, the method of data collection and its audio recording, possible benefits and risks. A free and informed consent form was applied.

The data were collected after approval by the Human Research Ethics committee, from 12/09/2020 to 04/28/2021.

Data collection was carried out through in-depth semi-structured interviews, one of which was carried out virtually and the others carried out in person. The in-person interviews were carried out at the hospital, in a closed, silent room and with the exclusive participation of the interviewer and the interviewee, with full care being taken to maintain the interviewee’s anonymity and privacy. During the virtual interview, the participant was asked to stay in a private and comfortable environment, complying with the same anonymity and privacy precautions. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed in full for analysis. Sociodemographic variables were also collected. For this manuscript, the analyzed variables were age, gender, marital status, self-reported skin color, religion and profession, and the guiding questions were: “How do you think we could improve your training to face situations like this?”; “How do you think we could improve the training of health professionals to deal with situations like this?”; “I would like to know if you have any other thoughts to add.” The interviews were then extended, based on their reflections and asking for further explanations, such as: “Tell me a little more about this”.

The interviewer was one of the researchers and was an intensive care resident doctor at the hospital at the time of data collection.

Data analysis

Quantitative data analysis was carried out using descriptive statistics.

The qualitative analysis was of thematic content, with initial reading of the material, without marking the text, followed by the decomposition of the group of messages and identification of the units of meaning (words, phrases, sentences); subsequently, the identification of the relationships between the units of meaning and their grouping into context units; and, identification of topis (or cores of meaning) encompassing these units3).(9.

RESULTS

The study participants comprised 20 professionals, aged between 27 and 51 years old, with an average of 39.1 years [Standard Deviation (SD) = 7.5 and 95% Confidence Interval (95%CI) = 35.6 - 42.6]. The median number of their children was 1 (P25 - 75 = 0 - 2). The length of professional experience ranged from 2 to 26 years, with an average of 16.3 years (SD = 7.6 and 95% CI = 9.2 - 16.3).

Other profile characteristics of these professionals are depicted in Table 1, which shows that the majority were female, self-declared white and in the medical or nursing-related field.

Table 1 Profile of the twenty professionals participating in the study, carried out in a high complexity hospital in Curitiba (southern Brazil) between the second half of 2020 and the first half of 2021.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Profession | |

| Doctor of the institution | 04 (20) |

| Resident doctor | 02 (10) |

| Nurse | 03 (15) |

| Nursing technician | 03 (15) |

| Nutritionist | 1 (5) |

| Psychologist | 1 (5) |

| Physical therapist | 1 (5) |

| Pharmacist | 1 (5) |

| Radiology Technologist | 1 (5) |

| Hygiene assistant | 1 (5) |

| Kitchen assistant | 1 (5) |

| Receptionist | 1 (5) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 17 (85) |

| Male | 03 (15) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 08 (40) |

| Married or common-law marriage | 09 (45) |

| Divorced | 03 (15 |

| Level of schooling | |

| Complete high school | 05 (25) |

| Incomplete higher education | 02 (10) |

| Complete higher education | 06 (30) |

| Postgraduate studies | 07 (35) |

| Self-reported skin color | |

| White | 10 (50) |

| Black | 04 (20) |

| Brown | 06 (30) |

| Religion | |

| Catholic | 08 (40) |

| Evangelical | 06 (30) |

| Spiritist | 01 (5) |

| Umbanda | 01 (5) |

| Advaita vedanta | 01 (5) |

| Atheism | 03 (15) |

Source: the authors.

Suggestions to better prepare health professionals to deal with the Covid pandemic were grouped into: suggestions for health care institutions and suggestions for health education institutions.

Among the suggestions for health care institutions, one of them was the implementation of well-designed care protocols and flowcharts to help them understand how to act, resulting in more homogeneous care and care integration. Another was the investment in regular and continuous professional development programs, not only to improve the quality of care but also to make professionals feel valued. In the context of crises and the pandemic, the program should prepare them to act, with theoretical information about Covid-19 and with theory and practice on biosafety, care for critically-ill patients, humanization and communication with family members. Additionally, the importance of managers valuing the psychological dimension of employees and providing psychological support was highlighted, due to the emotional overload generated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Chart 1 displays statements that illustrate some of these suggestions.

Chart 1 Statements illustrating suggestions from professionals at a highly complex teaching hospital for institutions that provide health care to better prepare their professionals for pandemics.

| Context units | Units of meaning | Illustrative statements |

|---|---|---|

| Improving the professionals with training | regular and continuous | - The institution would have to offer [...] training [...] in all categories, [...] because we were stuck in that same thing for a long time [...] so, some things we would have to have [...] an annual training [...] (NT2) |

| - The hospital has to value the professional who is inside [...]. So, if you are always employing and you are always: “Let’s train this, this and that”, the person feels valued and increases their knowledge to become a more suitable professional to work with (N3). | ||

| in biosafety | - Training for the attire [...], a guy came to the pantry explaining how we should wear it, but I think we didn’t follow it to the letter, because wearing that helmet, the glasses, was kind of strange, you know? (K) | |

| - Maybe, some lectures [...], which could reinforce hygiene care a little more, because we have here some folders on how to wash our hands, but it ends up being a routine thing that is not so reinforced [...] (RT) | ||

| - [...] how is the attire worn, and everything else, and removal of the attire [...] (NT1). | ||

| to act in emergencies and crises | - Like the ATLS (advanced trauma life support) and the ALS (advanced life support) [...], we only get better with training, there’s no point in wanting to do it right away, like: | |

| - “The guys are here, you’re working and, suddenly, we’re going to try to do some training”! You have to do something structured [...] preventive [...]. From time to time, do firefighter-type training. You don’t know what will happen or what can happen, but you have the possibility, even if it is minimal, but to do the training, something periodic, call the teams in general and always leave it fresh in their minds, at least, the basic things that need to be done. Then, we can solve this easily, it’s just like in cardiopulmonary resuscitation [...] if someone knows at least the basics, they do very well (RD1). | ||

| For humanization | - I think they should be focused on more daily training [...] about humanization, about care focused [...] on that patient’s problem [...]. I see that there are very brutal, very bad people, [...] and that affects me a lot [...]. So, I always think about the more human side, and the more humane care for the patient (NT2). | |

| Protocol implementation | - You can also make a protocol [...]. It’s true that protocols make things a little robotic, but at least if you have any doubts, you can follow that in there. (RD2). | |

| Psychological support for the employees | - In reality, this COVID took us by surprise. No one was expecting the world to stop. I think that if we had known before, the hospital would have found a way to reassure us a little more, because there were people who were very desperate, there were people [...] who are far from their families, so no one was prepared for this and I think that the hospital [...] should have prepared [...] the emotional part [...]. I think that the management, in general, the administration staff should have kept their eye on, should have paid more attention to employees, doctors, technicians, nurses. (K). |

Source: the authors.

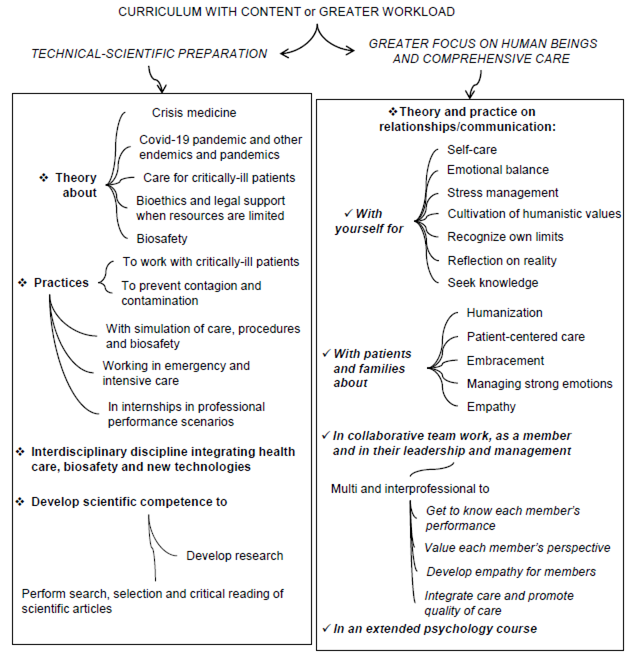

The participants’ suggestions for health education institutions are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Suggestions from professionals who work in a high-complexity teaching hospital for health education institutions to prepare their health professionals to better deal with pandemics.

As it can be observed, they included curricular insertion or increased workload of technical-scientific aspects to act in a pandemic and aspects for greater focus on human beings and comprehensive care, with theory and practice on the student’s relationships/communication with themselves, with patients and families and with team members from the same area of knowledge and interdisciplinary as a member and in their leadership and management.

Regarding the greater focus on humanization and comprehensive care, greater appreciation of the psychological aspects of the human being was suggested, as demonstrated by the statements below:

[...], how do you teach human beings, to be humane? It’s hard, isn’t it? [...] We are every day, all connected, interconnected. So, if we learn to look at each other as a team, as a group, as a community, say in a broad sense, society, [...], when we look at the patient and say ‘’Okay, the patient, he died’’, and we can understand that he is another one of us who left, I think the rest falls into place [...]. I’m looking at it in a more systemic way, but I think that’s it, everyone needs to understand each other a little better, a little more empathy, compassion (D4).

In this context, several suggestions were provided to improve the future professionals’ relationships with themselves, with self-care management in general, and to maintain emotional balance, manage stress and recognize their own limits, as illustrated below:

Things about psychology [...] help us to be okay with ourselves, so that you don’t become your nuisance. You should not be your nuisance [...] there should be more talk in health institutions about self-care, about looking at yourself. So, we are trained to look outside, look at those who are in need [...]. But and you? How do you do it? Who takes care of you? It’s a question that’s well-known, right: - Who takes care of those who take care?” It’s you who takes care of yourself! [...]. You have to be the best company for you [...]. There are days when we are so sad, that we have no strength. How am I going to take care of someone [...] with so much sadness inside? So [...] these things [...] must be taken into account, this is to improve education and to improve the world. The relationships. Have you ever thought about how much empathy that would awaken? (Psy).

The importance of learning to reflect on reality and seek knowledge was also highlighted, as illustrated below:

[...] discuss issues, especially what is happening around us [...]. What’s on the rise [...]. There are a lot of new things coming out. So, get us to debate, to seek out knowledge. It already combines the two things, you teach the student to seek knowledge, where are you going to do this. And really unite, exchange ideas, discuss (N).

To improve relationships with patients and families, humanization, embracement, knowledge of the patient’s perspective, management of strong emotions and communication of bad news were suggested, as in the statements below:

Ah, improve that grid, please [...] because [...] - “What is the most difficult within care? The person!”. The liver, we have medicine, the heart too, we know how to place an access, we have technology [...]. But what about the person? That soul, that being that is there? [...] When you look in the eye, people even find it strange [...] what should be the everyday life. Put it there: “How to deal with difficult people”, [...] “How to embrace, what is embracement, what is humanization?”. This has to go inside the university. [...] You need to take care of that angry person. [...] Say: - “I know it’s bad, I’m here, we’re going to help you” [...]. But no, they don’t do that. They want [...] to close people’s mouths (Psy).

Suggestions to promote collaborative work in multi- and interdisciplinary teams covered: knowledge of each team member’s perspective, development of empathy by team members, integration between care professionals and management and leadership skills.

Chart 2 displays some statements illustrating the content or greater load suggested to improve collaborative work in multi- and interdisciplinary teams.

Table 2 Statements illustrating suggestions on aspects to be included or increased in the workload to improve collaborative work in multi- and interdisciplinary teams.

| Suggestions | Illustrative statements |

|---|---|

| Knowledge about each member’s performance and perspective | - Work [...] more on interdisciplinarity, because we work on multidisciplinarity and we don’t work so much on interdisciplinarity [...]. Because, if the professional is not integrated into the team, there is something wrong, in my point of view [...]. There has to be a work integration, [...] it’s an integrality that we create over time, you don’t need to be friends with those people, but you have to know how to work as a team [...] (D2). |

| - [...] there is a lot missing from the interface [...], I would love to know how the day of the social worker [..] of the pharmacist [...] of the doctor [...] is like. If in our academic training there were more of these seams, in: “I know what you go through and you know what I go through”, at a time like this, we would not have certain distancings [...] (N1). | |

| Development of empathy by the team members | - If we develop a condition of empathy with the physical therapist who is stressed, tired, who makes a decision that you don’t agree with, a nursing technician who is more emotionally labile ... If we can look at everyone, as an essence exactly like yours, but with a lot of different conditions, then that person is you, who was born under other conditions and under another roof, and on other reflections of life. When you can look at it all like this, we understand each other in the rest. I think that at least this pandemic helped us to break a little of this hierarchy, which we have always, traditionally seen in the medical service, that the doctor is in charge of something, and, in the end, we were all together, us, the nursing technicians, the physical therapists, it was all the same chaos (D4). |

| Integration among care professionals | - Unite a little more, we are a very disunited class. So, we can’t seek support from other professionals. I think that would be a nice thing (Nut) |

| - We are all the same, because if I take care of the foot, you take care of the hand, the other takes care of the head, the other takes care of the lungs, the other takes care of... We are all the same, with the same purpose [...] it had to be closer [...], the teams had to be well united [...], one had to be intertwined in the service of the other so that our main and greatest focus [...] really was well achieved [...] which was the patient being well cared for (N1). | |

| - Group work, to help each other, because, perhaps, we think about ours and always forget about the other, that would be a good point. [...] Maybe I can do a better task than my colleague, and my colleague is better than me elsewhere, I think you can get together and help each other together... so, teamwork would help a lot (R). | |

| - [...] some experiences with a teacher having classes in groups of students from different disciplines such as nursing, physical therapy, nutrition, seeing the same clinical case, the same patient, and having these multiple points of view of the patient through each discipline, each specialty. [...] I had very little, knowing what a nurse does, what the physical therapist does, what the nutritionist does, what the psychologist does within the environment and the patient’s view. I think this helps both in a pandemic situation and in other day-to-day situations, to have a better idea of how each one sees the patient, this adds to the professional’s training (D1). | |

| - Put everyone in the same room to discuss, [...] with the speech therapist, with psychology, with the medical professional, everyone there. Then we discuss the patient according to the views of each one. I think this is important, to put a professional from each area to debate that patient, to understand that situation [...], so that each one will give their viewpoint until they reach a consensus, because each one has a background, each one knows a little about it and, when this knowledge is added, the patient wins (P). | |

| Development of management and leadership skills | - [...] people management is the one that is the least addressed in college, I think that this part, when we leave the university, we leave with a very big demand about it [...]. At the University we only learn in theory. So, this issue of dealing with the assistants and having guidance there regarding management [...] (P). |

Source: the authors.

Regarding the curricular components for better technical-scientific preparation in the training of health professionals to work in pandemics, many interviewees considered that their training had been predominantly theoretical and did not prepare them for future professional life, which made it difficult to work immediately after graduation. Therefore, the need for more practical classes with simulation was highlighted, initially, and internships in real-life professional practice scenarios with patients in emergency services and the intensive care units. To fill the theoretical and practical gap, an interdisciplinary discipline was suggested covering crisis medicine, health care, biosafety and new technologies, as in the following statement:

[...] a discipline in which you foresee [...] some type of situation or disease that is highly contagious and that could get out of control, like now, and that can and should happen, give some examples and try to characterize it a little and that you had a range of patients, a large number, within a short time, with impairment of their organic functions, in a very varied way, and see what you could do, what is your conduct towards these patients [... ]. Mainly on the issue of biosafety, for example washing your hands and wearing a mask [...] it would have to be debated for longer, together with these new technologies that have appeared on the market, whether they are effective or not, see which new products are that can improve this, if there is any barrier [...] Then, discuss this type of methodology and approach with technological innovation and deal in a practical way with a situation like this to train the teams (RD1).

Specific theoretical contents suggested and some statements that illustrate them are presented below:

Crisis medicine:

Crisis medicine is something that is widely discussed outside of Brazil, I don’t know if [...], we don’t work with it, or because we don’t have so many natural disasters, so many terrorisms [...]. It should be minimally worked on [...] I don’t know if it’s possible for you to prepare someone to go through what we went through, I even think, in a way, it’s practically impossible. (D2).

Covid-19 and other pandemics and epidemics - “[...] new subjects, mainly pandemics [...] a class with very advanced content on the COVID pandemic, or any other [...] (NT2).”

Action with critical patients:

Focus even more on the form of treatment of critically-ill patients [...] as early as in the beginning of the undergraduate course [...]. Because [...] the stable patient, [...] in a primary care unit, [...] in elective hospitalization, is [...] lighter. Not that you don’t need it, but if you work with critical patients, you work with any patient [...] Emergency care, you have to have a tremendous understanding of critical patients. Not just ICU, I think you have to classify everything based on critical patients, because you open the range and work with all types of patients (N3).

Ethical conflicts and legal support in decision-making, especially when resources are limited:

The teaching of ethical and legal content was greatly missed, [...] understanding how far that went. We were at the ethical limit. Many times, even these crucial decisions, about who goes to the ICU (intensive care unit), who will be intubated, who won’t, [...] I really missed understanding what we have in terms of legal support or not to be done, what the services can pressure you to do or not, [...] we were very lost in the ethical part. (D4).

Biosafety: (illustrated in RD1’s statement about an interdisciplinary discipline)

The suggestions for practical classes and supervised internships in real-life scenarios are shown in Chart 3.

Chart 3 Statements illustrating suggestions for practices to be included or increased in educational institutions for better technical-scientific preparedness of health professionals to deal with the pandemic in educational institutions.

| Suggested practices | Illustrative statements |

|---|---|

| in internships in real-life scenarios | - [...] they should focus on real situations (NT2). |

| - [...] it is also having a practical focus, of having the theoretical part, having the usual practical part of the university, but putting the pre-training professional more in the final stages of their training, in contact with the patient, [...] with the services, so that they can experience it, so that, at the end of their training, they can already do the work (D3). | |

| - [...] the practical part was missing a lot [...]. My training had a very theoretical focus [...]. The face-to-face part with the patient, I think it is even more deficient, I think that medical education as a whole in Brazil has this problem, of preparing the professional less to be working with the patient (D3) | |

| - [...] to have a practical focus as well, to have the theoretical part, [...] the usual practical part of the university, but to put the pre-training professional more in the final stages of their training, in contact with the patient, in contact with the services, so that their experience can enable them, so that, at the end of their training, they can already do the work. And we see little of this. The person who has just left college, they need a lot of help. Sometimes, they are not qualified to take on a role as a doctor, they learn, they need the help of colleagues and such, maybe we can act on this. (D3) | |

| They talk about the pandemic, endemic, these things, what it is. But they don't talk about how we are going to act [...]. What I learned the most was: medication and basic patient care. But not about more serious issues [...]. (NT1) | |

| of care for critically-ill patients in emergency settings and in intensive care units (ICUs) | - More practices in relation to what we are seeing, because [...] in the college I attended, if there is little experience inside an ICU [...], the basic thing was: - "Did you aspirate the patient? Did you mobilize?". That was it. But, you touch the respirator, understand what you are doing, that came with the post-graduation. But, it is important that the professional in training has this contact, [...] the preparation when you arrive at a hospital will be better for you, you will not get lost inside an ICU [...] because there is the discipline, I think there is a lack of practice itself. (P) |

| - More theoretical-practical classes [...], in college, I had few classes on severe patients, it was more outpatients. It was very divided between specialties. The intensive care medicine and emergency medicine part, we almost didn't have it, I don't remember having that there. I think there was an internship [...] when we just watched the preceptor making the prescription [...]. In college, I performed only one central access, I never intubated [...]. (RD2) | |

| - [...]. It should be the same as ACLS [Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support], [...], which teaches a little and we train on the dummy afterwards. A more dynamic thing [...] to have more internships, instead of staying inside the classroom [...]. When I did ACLS, I learned a lot. So I think that all medical professionals, nurses and nursing technicians should take the ACLS. You can take intubation and central access courses (RD2). | |

| in procedures | - We are very “raw” when we leave college. I really learned, and had the practice, here at the residency. Because, before, I didn't even know how to prescribe intravenous drugs, for example. We leave (College) knowing only how to make a diagnosis, for example, without knowing how to prescribe something (RD2). |

Source: the authors.

Another suggested area was the scientific competence to search, select and critically read articles and to carry out research as mentioned below:

Regarding the reading of scientific articles, the pandemic has revealed how we do not have good training to understand what a scientific article means. So: “Ah, hydroxychloroquine is good, isn’t it”, and even the medical community, everyone is a little lost, without knowing, a positive study comes out, but it’s just a study. [...] understand when to start using a medication, or a certain resource in medicine, based on studies, how many studies are necessary, which studies, what criteria (M4).

DISCUSSION

In our study, we identified many significant aspects that can make professionals better able to work in pandemics such as Covid-19. Contributions to health care institutions included the implementation of protocols for patient care, regular professional development programs or those focused on biosafety and the care of critically-ill patients. Improvement programs would be useful not only to improve the quality of care, but also to make professionals feel valued and promote greater critical reflection in them, which would avoid mechanical action.

A comprehensive and organized system of specific institutional actions, in public and private hospital environments, aimed at employee development (permanent education)42 is essential to minimize avoidable damages and errors and improve team performance and, consequently, promote the quality and effectiveness of the services offered by the institution43. In this context, managers play a crucial role in identifying the demands of their employees. The actions must include the development and dissemination of protocols with best practices, offering recycling and technical updates and making professionals aware of their social responsibility towards society as critical, conscious and participatory citizens 42)-(44. A study of the initial 250,000 Covid hospitalizations in Brazil demonstrated that greater attention was paid to the availability of resources, such as ICU beds and ventilators, than to offering adequate training to health professionals who would deal with patients. According to the authors, if attention had also been paid to training, the number of preventable deaths could have been lower45.

Regarding the contributions to educational institutions, one of the highlighted aspects was the greater focus on the teaching of psychology, on the student’s communication and relationships with themselves in relation to their self-care, including emotional balance and stress management, cultivation of humanistic values, such as empathy and solidarity, of their interpersonal communication, with patients, family members and team members, for the development of other aspects of professionalism, such as recognition of limits and reflection on reality, search for knowledge in everyday life and continuous updating. The interpersonal communication with the patient and family would encompass the humanization of care, embracing the patient, considering the perspective of the patient and of the healthcare team, demonstrating empathy and compassion for them, and knowing how to deal with them when they express strong emotions.

In a study carried out in Spain with nurses on the educational needs of nurses to face Covid-19, learning self-care, communication with patients and family members, demonstrating empathy, greater knowledge about stress and strategies for managing it were also suggested to control them and for the management of emotions. Moreover, the nurses suggested developing skills to speak and work with the general public and vulnerable groups and learning about how to deal with death and dying patients29. In line with this study, Amin et al.30 suggest that American schools place greater emphasis on humanism and humanistic care in the curricula at all levels of education, in different learning scenarios, strengthen professionalism and improve communication with patients and also promote in students: greater self-knowledge, acceptance, availability and expressiveness in the practice of care, interest and respect for dignity, construction of interpersonal bonds and relationships of trust, recognition and legitimization of the patient’s social, cultural and spiritual values and identification of emotional expressions. Na et al.36 also recommend teaching strategies such as mindfulness to maintain well-being and self-care and Nadeem et al.37 highlight the importance of preparing students and health professionals to prevent or deal with psychological trauma.

All of these elements are part of professionalism in its communication dimensions (intrapersonal and interpersonal) and the commitment to professional excellence and must be worked on throughout the curriculum at all times of health education. The need for learning them becomes even more evident when professionals face crisis situations such as the Covid-19 pandemic46)-(49.

Communication in collaborative work in a multidisciplinary and interprofessional team, as a member and in its leadership, through interdisciplinary discussion of cases, to understand the role of each professional, value their vision and integration of health care was also suggested in our study.

These findings are in line with the study with nurses in Spain29 and with several authors who highlight the extreme importance of developing competence for collaborative work and effective communication in an interprofessional team to better face the Covid-19 pandemic33),(50),(51. In the Spanish study, moreover, the need for organization, resource management, and organizational and work induction and socialization were highlighted29.

Regarding the suggestions for technical-scientific preparation, some participants in our study stated that their training had been predominantly theoretical, with little practical preparation to work in the professional reality, which made it difficult for them to work immediately after graduating. They also mentioned the importance of more classes on Covid-19 and, in addition to theory, a greater workload of simulated practical classes and internships in real work scenarios, in emergency internships and in intensive care units, to work in crisis medicine and with critical patients, to better prepare to identify signs of severity in patients and provide care to them, including carrying out invasive procedures. Classes with realistic simulation, as carried out in courses such as ATLS or ACLS, were highlighted as important learning opportunities for professional practice.

In the Spanish study, several technical, scientific and professional knowledge and skills were mentioned for mass crises, pandemics and catastrophes, covering biosafety and actions when dealing with critically-ill patients. In relation to biosafety, waste management and self-protection (equipment and other necessary measures such as hygiene), prevention and protection of vulnerable groups were highlighted. Aspects related to the clinical aspects and treatment of the aforementioned patients included basic training to work in intensive care units, emergency, surgery, intensive care resuscitation units and palliative care; use of technology and techniques in the operating rooms and use of surgical instruments29. Other articles also point out the importance of knowledge and practices related to Covid-1952),(53 and the need to address disasters in the nursing curriculum31.

Biosafety, regarding the appropriate use of personal protective measures and equipment and contamination prevention, was also mentioned in our study as an important content, as well as bioethics and bases for legal support, especially to act in scenarios with limited resources, considering the difficulty in making decisions about patients who could have access to the ventilator and the ICU.

In the Spanish study, in addition to bioethics, the need for transversal interpersonal knowledge and skills covering deontology, law and other disciplines was mentioned29. Wald and Rudy38 emphasize that the formation of the professional identity of future health professionals starts during training and continues throughout their career, being developed in medical education through critical reflection, relationships in a community of practice guided by mentors and by moral and emotional resilience. Then they reflect how dealing with the ethical dilemmas generated by the pandemic can challenge, inform and potentially transform the professional identity process of students and health professionals, favoring a more humanistic and morally resilient identity.

Other authors draw attention to the need to include content in the curriculum to develop competence in public health, including epidemiology, infectious diseases and health surveillance32),(54),(55 and to include knowledge about the determinants of health, including social and economic conditions and policies that shape individual and community health and well-being, the structural causes and roots of inequities and understanding issues related to positions, privilege and marginalization, creative and critical thinking, self-reflection, the development of bonds of trust with communities and mental health33. Moreover, some authors highlight the importance of a critical learning pedagogy in community services and working with the different aspects and social actors that are involved with it or exercise power over it, such as, for example, its leaders and political managers35.

In our study, the professionals did not mention these aspects, probably because collective and public health is already covered in the curricula of health schools, including practices in communities. However, more reflection on the social responsibility of health professionals and more practices on health surveillance and biosafety could be considered.

The importance of developing scientific competence was another aspect highlighted by the participants in our study. This finding was similar to that found in the Spanish study, in which its participants referred to the need to acquire knowledge and research skills29.

Therefore, our study shows the responsibility of healthcare institution managers to invest in the professional development of their employees to improve their professional performance during pandemics such as Covid-19, developing and disseminating protocols and offering training for technical updating and humanistic, psychological, social and moral development.

According to the perception of the authors of this study, another point of fundamental importance is the responsibility of those involved in the curriculum planning of health education institutions to include various aspects to better prepare their graduates to work in pandemics. The curriculum must include not only the comprehensive care of the patient, but also of the student, the future graduate, in their biopsychosocial, cultural and spiritual dimensions and not just their illness, with an expanded view of the social, economic and political determinants of the health-disease process of the population that leads to inequity and greater mortality in certain social groups, and must encourage the social responsibility of each professional in training.

Furthermore, more practices are needed that act as professional life and in the reality of work under supervision, more opportunities for reflection on the reality, interprofessional learning, collaborative collective work and shared leadership and people management and greater theoretical-practical content of various contents related to crisis medicine.

The limitation of our study is that it was carried out in only one institution. However, it brings contributions on several aspects that can be developed in the planning of health care institutions to better prepare their professionals and promote the quality of care provided, so that health institutions and teaching institutions can better prepare future professionals to deal with the Covid-19 pandemic and other pandemics, aiming to mitigate their impact on professionals, patients and society.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

We demonstrate that our study brought several topics relevant to the scientific community, with suggestions for professional training and preparation highlighted by professionals who worked in a health institution during the Covid-19 pandemic. The importance of developing continuing education and creating care protocols by health care institutions was highlighted. Moreover, topics that must be incorporated into curricula to improve and update teaching in health sciences, ranging from more humanistic aspects such as valuing psychological illness, communication and empathy to technical and practical training, with greater workload dedicated to topics such as intensive medicine, emergency and crisis medicine, to be emphasized in health training institutions. The results found seek to minimize the impacts of exceptional situations, such as the Covid-19 pandemic. We believe that our results can contribute to the future planning of the curriculum of health education courses, aiming to minimize the impact on professionals, patients and society.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. WHO timeline-Covid-19. WHO; 2020 [acesso em 30 maio 2020]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19 . [ Links ]

2. Lipsitch M, Finelli L, Heffernan RT, Leung GM, Redd. Improving the evidence base for decision making during a pandemic: the example of 2009 influenza A/H1N1. Biosecur Bioterror. 2011 June;9(2):89-115. [ Links ]

3. Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Pandemic Influenza. Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(18):1708-19. [ Links ]

4. Flecknoe D, Charles Wakefield B, Simmons A. Plagues & wars: the “Spanish Flu”pandemic as a lesson from history. Med Confl Surviv. 2018;34(2):61-8. [ Links ]

5. Silva Neto RM da, Benjamim CJR, Medeiros Carvalho PM de, Rolim Neto ML. Psychological effects caused by the Covid-19 pandemic in health professionals: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;104:110062. [ Links ]

6. Gómez‐Salgado J, Domínguez‐Salas S, Romero‐Martín M, Romero A, Coronado‐Vázquez V, Ruiz‐Frutos C. Work engagement and psychological distress of health professionals during the Covid‐19 pandemic. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(5):1016-25. [ Links ]

7. Koppmann A, Cantillano V, Alessandri C. Moral distress and burnout among health professionals during Covid-19. Rev Méd Clín Condes. 2021:75-80. [ Links ]

8. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. [ Links ]

9. Bohlken J, Schömig F, Lemke MR, Pumberger M, Riedel-Heller SG. Covid-19 pandemic: stress experience of healthcare workers-a short current review. Psychiatr Prax. 2020;47(4):190-7. [ Links ]

10. Ahmady S, Kallestrup P, Sadoughi MM, Katibeh M, Kalantarion M, Amini M, et al. Distance learning strategies in medical education during Covid-19: a systematic review. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10:421. [ Links ]

11. Gordon M, Patricio M, Horne L, Muston A, Alston SR, Pammi M, et al. Developments in medical education in response to the Covid-19 pandemic: a rapid BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 63. Med Teach. 2020;42(11):1202-15. [ Links ]

12. Kelly K. An opportunity for change in medical education amidst Covid-19: perspective of a medical student. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2020;13(3):345-7. [ Links ]

13. Khamees D, Peterson W, Patricio M, Pawlikowska T, Commissaris C, Austin A, et al. Remote learning developments in postgraduate medical education in response to the Covid-19 pandemic -a BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 71. Med Teach . 2022;44(5):466-485. [ Links ]

14. Lee IR, Kim HW, Lee Y, Koyanagi A, Jacob L, An S, et al. Changes in undergraduate medical education due to Covid-19: a systematic review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021; 25(12):4426-4434. [ Links ]

15. Naciri A, Radid M, Kharbach A, Chemsi G. E-learning in health professions education during the Covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2021;18:27. [ Links ]

16. Stojan J, Haas M, Thammasitboon S, Lander L, Evans S, Pawlik C, et al. Online learning developments in undergraduate medical education in response to the Covid-19 pandemic: a BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 69. Med Teach . 2022;44(2):109-29. [ Links ]

17. Mittal R, Su L, Jain R. Covid-19 mental health consequences on medical students worldwide. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2021;11(3):296-8. [ Links ]

18. Monaghesh E, Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during Covid-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1-9. [ Links ]

19. Garfan S, Alamoodi AH, Zaidan BB, Al-Zobbi M, Hamid RA, Alwan JK, et al. Telehealth utilization during the Covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Comput Biol Med. 2021;138:104878. [ Links ]

20. Lieneck C, Weaver E, Maryon T. Outpatient telehealth implementation in the United States during the Covid-19 global pandemic: a systematic review. Medicina. 2021;57(5):462. [ Links ]

21. Keenan AJ, Tsourtos G, Tieman J. The value of applying ethical principles in telehealth practices: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(3):e25698. [ Links ]

22. Budakoğlu Iİ, Sayılır MÜ, Kıyak YS, Coşkun Ö, Kula S. Telemedicine curriculum in undergraduate medical education: a systematic search and review. Health Technol (Berl). 2021;11(4):773-81. [ Links ]

23. Hartasanchez SA, Heen AF, Kunneman M, García-Bautista A, Hargraves IG, Prokop LJ, et al. Remote shared decision making through telemedicine: a systematic review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2022; 105(2):356-65. [ Links ]

24. Eichberg DG, Basil GW, Di L, Shah AH, Luther EM, Lu VM, et al. Telemedicine in neurosurgery: lessons learned from a systematic review of the literature for the Covid-19 era and beyond. Neurosurgery. 2021;88(1):E1-E12. [ Links ]

25. Novara G, Checcucci E, Crestani A, Abrate A, Esperto F, Pavan N, et al. Telehealth in urology: a systematic review of the literature. How much can telemedicine be useful during and after the Covid-19 pandemic? Eur Urol. 2020;78(6):786-811. [ Links ]

26. Haider Z, Aweid B, Subramanian P, Iranpour F. Telemedicine in orthopaedics during Covid-19 and beyond: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2022;28(6):391-403. [ Links ]

27. Oliveira Andrade A de, Soares AB, Andrade Palis A de, Cabral AM, Barreto CGL, Souza DB de, et al. On the use of telemedicine in the context of Covid-19: legal aspects and a systematic review of technology. Res Biomed Eng. 2022;38(1):209-27. [ Links ]

28. Shah AC, Badawy SM. Telemedicine in pediatrics: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2021;4(1):e22696. [ Links ]

29. Peiró T, Lorente L, Vera M. The Covid-19 crisis: skills that are paramount to build into nursing programs for future global health crisis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):6532. [ Links ]

30. Amin S, Chin J, Terrell MA, Lomiguen CM. Addressing challenges in humanistic communication during Covid-19 through medical education. Front Commun. 2021;6:619348. [ Links ]

31. Achora S, Kamanyire JK. Disaster preparedness: need for inclusion in undergraduate nursing education. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2016;16(1):15-9. [ Links ]

32. Bedi JS, Vijay D, Dhaka P, Gill JPS, Barbuddhe SB. Emergency preparedness for public health threats, surveillance, modelling & forecasting. Indian J Med Res. 2021;153(3):287-98. [ Links ]

33. De Maeseneer J, Fisher J, Iwu E, Pálsdóttir B, Perez KL, Rajatanavin R, et al. Learning from the global response to the Covid-19 pandemic: an interprofessional perspective on health professions education. NAM Perspect. 2020:10.31478/202011b. [ Links ]

34. Dashash M, Almasri B, Takaleh E, Halawah AA, Sahyouni A. Educational perspective for the identification of essential competencies required for approaching patients with Covid-19. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26(9):1011-7. [ Links ]

35. Derreth RT, Jones VC, Levin MB. Preparing public health professionals to address social injustices through critical service-learning. Pedagogy Health Promot. 2021;7(4):354-7. [ Links ]

36. Na B, Yada R, Wong R. Establishing self-care practices early in medical and health education: a reflection on lessons learnt from the Covid-19 pandemic. World J Med Educ Res. 2021;26(1):18-20. [ Links ]

37. Nadeem T, Asad N, Hamid SN, Mahr F, Baig K, Pirani S. A need for trauma informed care curriculum: experiences from Pakistan. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;63:102791. [ Links ]

38. Wald HS, Ruddy M. Surreal becomes real: ethical dilemmas related to the covid-19 pandemic and professional identity formation of health professionals. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2021;41(2):124-9. [ Links ]

39. Michaelis Dicionário Brasileiro da Língua Portuguesa. Afetividade [acesso em 17 jun 2024]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://michaelis.uol.com.br/moderno-portugues/busca/portugues-brasileiro/afetividade/ . [ Links ]

40. Ferreira AL, Acioly-Régnier NMC. Contribuições de Henri Wallon à relação cognição e afetividade na educação. Educ Rev. 2010;(36):21-38. [ Links ]

41. Minayo MCS. O desafio do conhecimento: pesquisa qualitativa em saúde. 9a ed. São Paulo: Hucitec; 2014. [ Links ]

42. Macêdo NB de, Albuquerque PC de, Medeiros KR de. The challenge of implementing continuing education in health education management. Trab Educ Saúde. 2014;12:379-401. [ Links ]

43. Sade PMC, Peres AM, Zago DPL, Matsuda LM, Wolff LDG, Bernardino E. Avaliação dos efeitos da educação permanente para enfermagem em uma organização hospitalar. Acta Paul Enferm. 2020; eAPE20190023. [ Links ]

44. Sampaio LA, Silva FML, Ramos MHT. Os impactos na educação corporativa hospitalar com o surgimento do Covid-19: uma revisão integrativa. Res Soc Dev. 2021;10(1):e54110112094-e. [ Links ]

45. Ranzani OT, Bastos LS, Gelli JGM, Marchesi JF, Baião F, Hamacher S, et al. Characterisation of the first 250 000 hospital admissions for Covid-19 in Brazil: a retrospective analysis of nationwide data. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(4):407-18. [ Links ]

46. Project MP. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physicians’ charter. Lancet. 2002;359(9305):520-2. [ Links ]

47. Sullivan WM. Medicine under threat: professionalism and professional identity. CMAj. 2000;162(5):673-5. [ Links ]

48. Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. Defining professionalism in medical education: a systematic review. Med Teach . 2014;36(1):47-61. [ Links ]

49. Bhagwan R, Rowkith S. An exploratory study of the experiences of emergency medical care (EMC) students transitioning through the Covid-19 pandemic in South Africa. J Educ Health Promot . 2023;12:281. [ Links ]

50. Brisolara KF, Smith DG. Preparing for a more public health-aware practice of medicine in response to Covid-19. J Clin Cardiol. 2021;2(3):43-5. [ Links ]

51. Nurhidayah RE, Revi H. Communication in the curriculum interprofessional education. Novateur Publication. 2020;16(09):56-8. [ Links ]

52. Dashash M, Almasri B, Takaleh E, Abou Halawah A, Sahyouni A. Educational perspective for the identification of essential competencies required for approaching patients with Covid-19. East Mediterr Health J . 2020;26(9):1011-7. [ Links ]

53. Nascimento AAA, Ribeiro SEA, Marinho ACL, Azevedo VD, Moreira MEM, Azevedo IC. Repercussions of the Covid-19 pandemic on nursing training: a scoping review. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2023 May 12;31:e3911. [ Links ]

54. Alkhateeb BF. Public health and epidemiology education in Saudi Arabia: changes required to be made following Covid-19 pandemic - an opinion of public health expert. J Health Inform Dev Ctries. 2020;14(2). [ Links ]

55. Brisolara KF, Smith DG. Preparing for a more public health-aware practice of medicine in response to Covid-19. J Clin Cardiol . 2021;2(3):43-5. [ Links ]

Received: November 24, 2023; Accepted: July 15, 2024

texto em

texto em