Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Cadernos de História da Educação

versão On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.21 Uberlândia 2022 Epub 13-Set-2022

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v21-2022-113

Dossier 3 - Personalized and community pedagogy in the ibero-american space (1950-1970)

The reception of the Personalized and Community Pedagogy in Spain in the Franco’s dictatorship. The case of Madrid1

1Universidad Complutense de Madrid (España). sramosz@ucm.es

2Universidad Complutense de Madrid (España). rabarom@ucm.es

Personalized teaching is a pedagogical trend that was originated in France in the post-war context of the World War II. It emerged as a response to the identity crisis of the subject caused by European totalitarianisms. In Spain, the reception and appropriation of this pedagogical trend took place at the end of the sixties during the Franco’s dictatorship, a political context far removed from the French or the Italian. It will be introduced through the works and publications of the Professor of Experimental Pedagogy at the Complutense University of Madrid (Spain), Victor García Hoz; and on the other hand, through the Teresian Institution (TI). This article focuses especially on the latter, exposing the different initiatives that the organization developed to train its female teachers in the pedagogical principles of Pierre Faure's pedagogy as well as the practical application that these teachers developed in schools run by TI.

Keywords: Personalized and community education; Víctor García Hoz; Teresian Insitution; Madrid; Francoism

La enseñanza personalizada es una corriente pedagógica que se originó en Francia en el contexto posbélico de la II Guerra Mundial. Surgió como una respuesta a la crisis de identidad del sujeto que provocaron los totalitarismos europeos. En España, la recepción y apropiación de esta corriente pedagógica se produce a finales de los años sesenta durante la dictadura franquista, contexto político muy alejado del francés o el italiano. Será introducido a través de los trabajos y publicaciones del catedrático de Pedagogía Experimental de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (España), Victor García Hoz; y por otro lado, a través de la Institución Teresiana. Este artículo se centra especialmente en esta segunda, exponiendo las diferentes iniciativas que la organización desarrolló para formar a su profesorado femenino en los principios pedagógicos de la pedagogía de Pierre Faure así como la aplicación práctica que estas maestras desarrollaron en las escuelas dirigidas por la IT.

Palabras clave: Educación personalizada y comunitaria; Víctor García Hoz; Institución Teresiana; Madrid; Franquismo

O ensino personalizado é uma tendência pedagógica que se originou na França no contexto do pós-guerra da Segunda Guerra Mundial. Surgiu como uma resposta à crise de identidade do sujeito provocada pelos totalitarismos europeus. Na Espanha, a recepção e apropriação dessa tendência pedagógica ocorreram no final dos anos 60 durante a ditadura de Franco, um contexto político muito distante do francês ou do italiano. Será apresentado através dos trabalhos e publicações do Professor de Pedagogia Experimental da Universidade Complutense de Madrid (Espanha), Victor García Hoz; e, por outro lado, por meio da Instituição Teresiana. Este artigo enfoca especialmente este último, expondo as diferentes iniciativas que a organização desenvolveu para formar suas professoras nos princípios pedagógicos da pedagogia de Pierre Faure, bem como na aplicação prática que essas professoras desenvolveram em escolas administradas por TI.

Palavras-chave: Educação personalizada e comunitaria; Víctor García Hoz; Instituição Teresiana; Madrid; Franquismo

Introduction

Personalised education is a pedagogical trend that was originated in France after the World War II, and gradually spread to other European countries such as Germany, England, Holland, Italy, Portugal and Spain, and also to Latin America, in Colombia, Mexico and Brazil (Dallabrida, 2018), as well as to Canada, Lebanon and Syria (Faure, 1976: p. 5). It emerged as a response to the identity crisis of the subject provoked by European totalitarianisms. In this context, the French philosopher Emmanuel Mounier stands out as one of the main promoters of Christian thought known as personalism. Through his works, such as the magazine Esprit created in 1932 or Quèst-ce que le personnalisme? published in 1947, Mounier critically analysed the individualistic society of those years in opposition to the spirit of Christianity (Ruiza; Fernández, Tamaro, 2004), defending a current of thought in which "priority should be given to the human person over the material conditions and over the collective structures that sustain his development." (Galino, 1991: 114-115). His thinking would be reflected in French educational policy in the 1940s, calling for a model of comprehensive education for children, taking into account the importance of the individual, his or her formative dimension and moral education, to the detriment of the exclusivism of the sciences. All this as a prelude to a direct integration into social life, a rationalisation of programmes and the application of active learning methods. Alongside the figure of Mounier, the Christian philosopher Jacques Maritain should also be mentioned, especially for his influence in the Italian context, as a defender of neo-Thomist thought and of an integral humanism, on the basis of which he also reflected on the person, not only as an individual but also as a social and dialogical human being (Jiménez, 1991). (Jiménez, 1991).

The French Jesuit Pierre Faure joins this personalize current, arguing that a men is the first and foremost himself and, almost at the same time, social, and is therefore both personal and communitarian. Based on this premise, he defends a school that educates and trains human beings in democratic states through a humanist, spiritual, personalist and community education based on the empowerment of the personal and the harmonisation of the social context. She worked with a disciple of Maria Montessori, Helene Lubienska de Lenval, and participated in the creation of various institutions for teacher training: the Centre for Pedagogical Studies (1937); the Centre for Pedagogical Training (1959), where she taught dozens of summer courses; three Teacher Training Colleges in France and an application school in Paris (1947-1952). He contributed to various journals and in 1945 he founded the journal Pedagogie, Éducation et Culture, which he edited from its creation until 1972 and which would serve as an organ of expression for all his educational activity and proposals. He also participated in the founding of the International Association for Educational Research and Animation (IAERA), made up of educators from different countries around the world, mainly belonging to public schools run by Catholic religious and Jesuits (Klein, 2002), including the teaching staff of the Teresian Institution (TI). Since 1972 and through this association, teacher training courses have been held in France, Spain, Brazil, Mexico, Beirut, Canada, Bogotá, Santo Domingo, Venezuela, among many other countries, to promote this pedagogical model based on a humanist, spiritual, personalist and community education, as Faure advocated.

Pierre Faure's pedagogical project is based on three pillars: the Catholic tradition, the biopsychological perspective and classic pedagogical authors. In relation to the Catholic tradition, it is framed within the documents of the ecclesial magisterium, the Jesuit spirituality, the personalist current of Mounier and the spiritualism of Lubienska integrate the anthropological-religious bases of his proposal. As for the biopsychological perspective, it is based on Montessori - whom Faure described as "a humble disciple of Eduardo Seguin", Piaget, Bourneville and Seguin, who worked with handicapped and unstable children2. He adopted the didactic material of Seguin and Bourneville in order to achieve precision and individualisation of the child's acquisitions and their objective progression. Finally, the pedagogical basis of her project is based on some classical authors (Plato, Montaigne and Pestalozzi), the personal work of the Ratio Studiorum, the New School movement, the Dalton Plan (Pozo and Braster, 2017), Freinet (Rabazas, Ramos and Sanz, 2019) and the French educational reforms of the post-war period. (Klein, 2002: 32-33 and Faure, 1976: 5-10).

The projection of personalist pedagogy was introduced in Spain in different ways. In this article we will focus specifically on one of them, as we will explain below, through the Teresian Association. Taking into consideration the results of previous studies carried out by the authors (Rabazas and Ramos, 2018 and Rabazas, Sanz and Ramos, 2020), in this paper takes an example of two educational centres in the context of Madrid: Veritas Institute, a private educational institution, with a great pedagogical impact on the educational community, as it is a reference centre for teacher training and research (Institute of Pedagogical Studies); and Father Poveda School Group, a public school located in a working-class neighbourhood of Madrid, where this pedagogical model is projected under the management of this organisation. For this purpose, we have mainly used primary documentary sources from the institutional archives of the IT in Madrid, as well as the Lasalliennes archives in Lyon (France). 3 For a more complete analysis, these sources have been triangulated with oral testimonies and memories of pedagogical practices, which describe the teaching practice of the centres under study, located in the Museum of Educational History "Manuel Bartolomé Cossío" of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

1. Pierre Faure's pedagogy in Spain

The reception and appropriation of this pedagogical current in Spain took place in a political context very different from France or Italy. While this movement arose in democratic contexts, it was introduced in Spain during the Franco’s dictatorship, specifically in the period of Spanish desarrollism in the 1960s, when there was an opening towards the outside world. At the same time, it should be in mind that its positive reception was also motivated by the fact that it was a philosophical and educational model with a Christian basis, and was projected through two channels:

a) Victor García Hoz and personalised teaching

Víctor García Hoz was a Professor of Experimental Pedagogy at the Complutense University of Madrid (Spain) and founder of the Spanish Society of Pedagogy. He came into contact with pedagogical personalism when he attended the First Congress of the Schòle Centre for Pedagogical Studies in Italy in 1954. He met Christian-inspired university professors such as Agazzi, Buyse, Planchard and Flores d'Arcais (Machietti, 1982). His first work is the result of several conferences he gave on personalised education, compiled in a book published by the Valdecilla Foundation of the University of Madrid. Later, in 1970, he published a book entitled Education Personalizade (Educación Personalizada) edited by the Pedagogical Institute of the Superior Council of Scientific Investigations (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas-CSIC) in which he deals with the doctrinal bases of personalised education and its practical applications (García, 1970).

Years later, in the 1990s, he directed several publications dealing with personalised education from different points of view, having a great impact on the university community, especially in teacher training centres. He focused his interest on the family, special education, teacher training, and the objectives of this pedagogy and some problems and research methods in relation to personalised education4.

His approach combines two traditions: individualised teaching, which offers constant attention to the difficulties and special possibilities that the child encounters in the educational process; and collective teaching, which allows the socialisation of schoolchildren and represents a greater economy in teaching time and effort (García, 1970: 18-19). In his work we can see how his approach to personalised education is not associated with a form or a new method of teaching but with an education in which the work of learning is an element of "personal formation through the choice of work and the acceptance of responsibilities by the pupil himself" (García, 1970: 20). From the concept of person derives the fundamental orientations of personalised education pointed out by the author, based on uniqueness, autonomy, creativity, openness and communication5.

b) The Teresian Association (TI) and personalised and communitarian pedagogy

The Teresian Institution was created by Father Pedro Poveda in 1911 as an ecclesial association of lay people, with the aim of strengthening the dialogue between faiths - insofar as the Incarnation is considered the key to all educational structures - (Galino, 1965: 58) and science - through education and culture. Its two foci of action were directed towards women's education and teacher training. He recognised a specific mission of women in society that required an education that promoted women "cultured, virtuous, healthy in body and soul, but as women and not as men; with the modalities proper to their sex to perfection, but not confusing perfection with sex, and judging, as mistakenly happens, that a perfect woman is the one who resembles a man" (Galino, 1965: 86), inspired by the spiritual physiognomy of St. Teresa of Jesus.

Pedro Poveda was concerned with creating religious institutes to train women for teaching positions in official education. He advocated the renewal of public education through innovative centres that would improve the training of women teachers while "maintaining the Christian spirit and professional union in all members of the TA (Galino, 1965: 178). The first Academies specialised in the training and preparation for competitive examinations for female teachers and, in parallel, Catholic Girls' Institutes were created to complete the secondary education of women. In the first pedagogical publication, El Ensayo de Proyectos Pedagógicos, which he began to write in 1911 in Covadonga, he established a plan for the foundation of Academies for teachers. In the words of Father Poveda, these educational initiatives had a clear purpose:

la Institución no se fundó para proporcionar facilidades a las jóvenes, ni para instruirlas y hacerlas cultas, ni para brillar en el campo de la ciencia, sino para santificarse y santificar al prójimo; para hacer maestras santas, capaces de salvar a los pueblos; para educar cristianamente a las que después en sus cátedras, en el ejercicio de sus respectivas profesiones, en sus casas, en la sociedad, han de ser modelos de virtud, formar legión de apóstoles de Cristo, para extender el reinado de Jesús6

The thought and work of Father Poveda was oriented towards a pedagogy based on the principles of communication -insisting on the coexistence between teachers and students-; creativity -as the individual initiative, spontaneity and freedom of the learner-, and differentiation -linked to the individualisation of teaching-. Inspired by authors such as Andrés Manjón, Rufino Blanco or Ruiz Amado, Pedro Poveda accepted the "Herbartian scheme of Pedagogy determined by a psychology and ethics" (García Hoz, 1974: 338-339) under a philosophical and social conception of "man and human life, a methodological and practical content and, finally, a historical reflection" (García Hoz, 1974: 338-339).

But the death of his mentor in 1936 led the TI to seek new pedagogical references close to Poveda's values. The personalize current developed in France in this period with Mounier and Maritain, implemented by the Jesuit priest Pierre Faure in a pedagogical project, would become the basis of the educational model developed by the TA In this sense, at the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s, a group of Teresian female teachers travelled to France at the initiative of Carmela Álvarez, Regional Director of the TI in Madrid (1958-1966), to attend training courses on personalised teaching organised by Faure in Paris, at the Centre de Formation Pédagogique (CFP). They were also accompanied by Father Emiliano Mencía, a member of the Congregation of the De La Salle Brothers. On their return to Spain, these educators introduced this pedagogical proposal in the centres they ran in Madrid. They disseminated this educational model through various courses, which they in turn organised from one of their institutions: the Véritas Institute. Created in 1960 by the TA it is located in a luxury residential area on the outskirts of Madrid, called Somosaguas, belonging to the municipality of Pozuelo de Alarcón. Its origins are to be found within the group of schools created in Madrid by the TAin the first third of the 20th century, such as the Academia, in 1914; the Female Catholic Institute, in 1924 and the Veritas School, located in the street Españoleto and which operated from 1932 to 1970. Once the Civil War was over, the first three centres were integrated into the Veritas School, which led to the need to design a new building on the suburbs of Madrid in the late 1950s, with spaces and facilities that responded to the educational principles of the TA educational model, which led to the construction Verita's Institute.

In 1965, Ángeles Galino, Carmela Álvarez, Irene Gutiérrez de la TA and Brother Emiliano Mencía, from La Salle, directed the first course on Didactic Orientation in Spain at the Veritas Institute. In one of the school memories of this centre, corresponding to the academic year 1965-1966, some details are mentioned of this training course for teachers, which took place from 5 to 18 August 1966, in which 120 religious men and women from Madrid and various Spanish provinces took part. As regards the content of the course, it is noted that during the two weeks there was an alternation of theoretical presentations and practical classes. In this way, the teachers were able to see how personalised teaching was applied in practical sessions with the students, verifying the pedagogical system of the TI by direct observation. The aim of these courses was to provide the participants with a very complete vision and a very practical orientation of this teaching system.

These were years in which there was an opening and a demand for pedagogical renewal from different associations and groups of teachers. Summer schools were organised to renew the training of teachers at all levels of education. (Milito and Groves, 2013) The TI also took part in this renewal, with Professor Ángeles Galino being part of this teaching staff, and with these words she points out some of the reasons for these changes: "It was a change that was demanded for different reasons, among others, the economic growth of the sixties, the Spanish participation in international organisations such as the OIT, UNESCO, the Council of Europe, etc." (Milito and Groves, 2013).

In conclusion, the pedagogical teaching model developed by the TI integrates a Christian and humanist pedagogy inspired by the pedagogical thought of Pedro Poveda with the personalised and communitarian teaching developed by the French Jesuit, Pierre Faure.

2. The training of female AT teachers in the personalised and community education model.

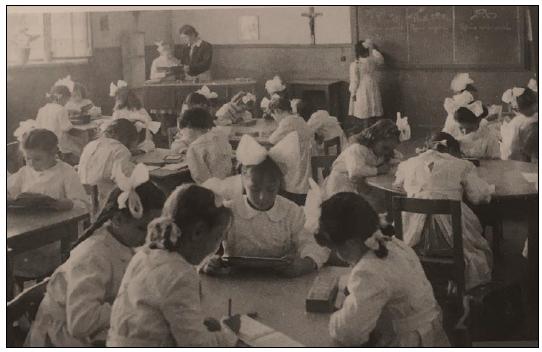

Created in 1960, the Veritas Institute introduced new methodologies based on personalised education. The dissemination of this model through the courses given at this institution made it a pilot centre at which educators from the country and abroad came as classes and teaching session´s observers, as can be seen in the photograph (I).

Photo I Picture of teachers participating in teacher improvement training courses at Veritas Institute7.

A large number of Church and public schools joined this movement. This initiative sought to disseminate personalised teaching through Experience and studies seminars aimed at training of teachers and school managers. Irene Gutiérrez mentions some of the activities that took place in this pilot centre: "the visits and stays of teachers in the renovated centres, mainly in Somosaguas, the supervision of the centres themselves, the school and teacher training materials created, the conferences and talks" (2009: 188).

The consolidation of this movement take place with the creation of the Somosaguas Institute for Pedagogical Studies (to be referred as IEPS) in 1969. It is set up as a centre for documentation, training, study and pedagogical research, as well as for dissemination through the different activities promoted by the IEPS. Another of the instruments of dissemination used by this movement was the foundation of the journal Orientaciones Pedagógicas, which had the task of disseminating and propagating the training work of the TA, and was the link with the pilot centres that were intended to be set up in each of the provinces of the Institution. (Gutiérrez, 1971, 2009; Sánchez, 1996).

The dissemination of personalised pedagogy gradually spread throughout Spain, thanks to Pierre Faure and María Nieves Pereira, Head of the Research and Information Division of the ICE and teacher at the Teacher Training College. We highlight in 1970, the Conference on Personalised Pedagogy held in Navarre, attended by some 200 teachers and involving 150 children. In an interview with Faure himself in the local press, he stated: "my method is aimed at training the teacher, because the secret of success is hidden in this point, the training of teachers. It is the most important thing" (Vida, 1970). Later, in 1972, from 14 to 16 February, Pierre Faure again took part in a conference in Murcia on Personalised Education, this time at the invitation of the Institute of Education Sciences of the University of Murcia, in collaboration with the Technical Inspectorate of Primary Education and the Teacher Training College. It was attended by recent graduates, inspectors, teachers from teacher training colleges and teachers. Two years later, in 1974, they were held again between 31 October and 3 November, with the collaboration of the Inspection and IAERA. On this occasion, the training received was validated with a Certificate of Participation - provided in the Ministerial Order of 14 July 1971 and the Resolutions of the Directorate General for Educational Planning of 9 May and 3 October 1972). Following the same methodological structure as in the courses at the Veritas Institute, these seminars also combined theoretical and practical training. Direct observation of children and the teacher´s activity of the during a school day made it possible to analyse aspects related to the children, including: arrival and entry to the classroom, incorporation into ork, development of personal work and sharing, etc.; and in relation to the teacher, the participants could analyse his or her attitude during personal work and sharing, help given to students, presentation of material and teacher-pupil relationship.

During those years, this pedagogical project was also extended to public schools by teachers belonging to the TA, as in the case of the Father Poveda School. From 1940 onwards, the Ministry of National Education agreed that this public school would be run by the TA under the special Patronage system as a testing and experimental centre. In some way, it was intended to rescue the purpose for which the Republican government built this school in 1933, appointing Justa Freire, a disciple of Ángel Llorca, as its first director. The demand of the directors of these schools, who introduced the educational renewal of the New School into Madrid, was precisely that they should select their teaching staff, in order to implement an innovative educational project. This circumstance implied that the school's teaching staff were from the TA, but they had to belong to the National Teaching Profession, i.e. they had to have competed for the public posts convoked by the Ministry. Therefore, we find ourselves with a public school run by the Teresian teachers and whose teaching staff was trained in the pedagogical ideology of Father Poveda and, afterwards, in the personalised education of the French Jesuit Pierre Faure. The management of this school remained in the hands of the TA until 1974.

The school was created in a suburban area of Madrid, in an area of the industrial expansion of Madrid, called Garden City (Ciudad Jardín, Prosperidad). The population is of lower social class, working class people living in the suburbs of Madrid. Recent research carried out by the authors of this paper has explored the history and purpose of these centres in much greater depth (Rabazas; Ramos, 2018; Rabazas; Sanz and Ramos, 2020). With regard to the social origin of the pupils at this school, it has been found that they were the daughters of skilled workers from the factories and industries set up in this neighbourhood and that were going established in this industrial area: pharmaceutical laboratories, textile factories, cardboard factories, automobile industry, precision apparatus, watches, etc. Many of these factories and industries became immediate employment positions for many of the students who were trained in this school, according to one of the authors, responding "to the ideal of forming an efficient, skilful, responsible, dignified, good collaborator, companion and subordinate worker".

However, some students who studied at this school confirm in their testimonies that the most advanced girls were prepared for the entrance exams to secondary school and for the revalidation exam at High Schools for girls: Beatriz Galindo and Lope de Vega. Most of the exams were oral and they presented many materials they had made themselves (collections of animals, plants, minerals, synoptic tables of history, science, etc.), demonstrating a high level of preparation, which was admired by the examining board. This higher education enabled them to opt for other professions, such as teaching, shorthand, secretarial work, conservatory, etc.

This school, despite being in a working class area, was a pilot and experimental centre, in which innovative methodologies were applied, in accordance with the autonomy conferred to it as an educational institution under the Patronage regime. Numerous testimonies testify to its educational work, affirming the solid preparation provided by excellent teachers. In the words of a female former student, they received a human and professional training very close to the excellence in demand at the time8.

3. Application of the personalised pedagogical model in the Véritas Institute and the Father Poveda School Group (Madrid, Spain).

To individualice the teaching in order to personalise education is the main element of this pedagogy. This allows everyone to find in a community framework the answer to its personal needs. If it is diversified to the point of individualisation, equal opportunities are achieved for all students, not to equalise them, but so that each one has the opportunity to develop and to reach as far as his or her possibilities allow.

In order to develop this pedagogical teaching model, Faure proposes an educational practice based on new forms of spatial organisation and time modulations; he transforms the relationship between the teacher and the students; new teaching methodologies; he introduced innovations in the distribution of spaces, furniture and school time; curricular adaptations to the individual pace of the students are proposed; curricular innovations; extracurricular activities, etc. We will now analyse the most important changes that move this teaching model away from the traditional pedagogical model.

The figure of the teacher is based on the pedagogical approach of paidocentrism which, following modern pedagogy, places the child at the centre of the teaching-learning process and not in the mere transmission of the teacher's teaching, thus connecting with the principles of the New School of the first third of the 20th century. Therefore, teachers accompany and guide students' learning, helping them to discover their own possibilities, interests, aptitudes and potential, bringing out the best in each person. (Faure, 1981). The teacher mediates and helps but does not supplant (Faure, 1988)9. They do not give help if it is not necessary. This view of the teacher was already laid out in Poveda's programme, which stressed the necessary equality between teacher and pupil (Galino, 1965: 73), insofar as the educational task is fundamentally a work of communication between the two, in which the teacher influences and is influenced in such a way that he/she acquires the status of pupil and the pupil that of teacher. Both participate in "life and common knowledge, exercising, although to different extents, a reciprocal influence" (García, 1974: 334-335).

Special attention in this pedagogical model deserves the observation skills of teachers. Direct reference is made to the important task of observing at the beginning of the school year in order to get to know the children in depth, discovering their "desires, their hobbies, their ways of seeing things, their feelings, their environments, their networks of friendships" (De las Heras, 1976, 247: 67). Knowledge of the child provides the necessary information to be able to accept his/her personality and to be able to help him/her in what he/she really needs. This is a key aspect of personalised education. Accepting him/her as a person means respecting his/her autonomy and independence and therefore, the work carried out must be the child's decision and not imposed by the teacher. As Pierre Faure states:

aquel que quiere practicar una enseñanza personalizada y comunitaria [...] deseará ser educador y no sólo docente, animador de sus alumnos y no sólo su maestro. Necesita animarse a sí mismo y tomar las medidas necesarias: reflexión, observación, puesta en tela de juicio y también iniciativa para buscar los mejores medios para el grupo que constituye su clase y para cada uno de sus alumnos. De ello se deriva una exigencia: no existe enseñanza personalizada sin la preocupación de cada persona, sin el respeto a la personalidad, a lo que cada uno ha adquirido, a su carácter, a sus posibilidades, casi siempre subestimadas, a su ritmo de adquisición. De esta forma el profesor se convierte no sólo en animador y educador, sino también en psicólogo. Otra exigencia: buscar sin descanso el verdadero progreso, interior y de asimilación, en vez del resultado inmediato; buscar el trabajo que hacen reflexionar y que ayudan a encontrar por uno mismo los textos y los autores que enriquecen, en vez de los manuales y los resúmenes.»10

Therefore, this pedagogical model is going to change the role of the teacher, who should be more oriented to show the work, the methods, the instruments, to make the child aware of what he/she does, of what he/she has to do, of his/her weaknesses, of everything that can help him/her to overcome, and that he/she is the one who has to work. The teacher becomes a counsellor and is the one who provides spaces for the students to interact with their classmates and help each other, at the same time fostering community or cooperative education. The girls carry out their individual work with a certain degree of autonomy11, taking as a premise that "all useless help delays the development of the pupil; useful help provokes the activity of the spirit" (Gutiérrez, 1970: 26), and maintaining the programmatic line of personalised pedagogy pointed out by Monique Le Gall12:

Los niños, aún más que los adultos, tienen necesidad de un medio pensado para ellos. En la medida de lo posible el local debe ser preparado de forma que quede salvaguardada la existencia de un espacio, de un local libre para la realización de diversas actividades. EI mobiliario (sillas y mesas) individual, que debe ser manejable, se desplazará según el gusto de cada uno, bien para aislarse, bien para aproximarse a los otros, bien para facilitar los intercambios y la comunicación entre los niños. De esta forma la clase puede transformarse de acuerdo con las necesidades. Los locales anexos: pasillos, escaleras..., no permanecen sin ser utilizados y los alumnos los utilizan ampliamente.

The practice of this teaching model is based on the principle of individualisation of teaching. Faure explains what it consists of in these words: "It is the putting into action of the individuals themselves who reveal to themselves their development and progress´ possibilities by discovering that they are capable of it, just as they are, with what little they think they are. Each person learns by himself to be and to become more than he is" (1981: 17). From the students' interests, interest in learning and the freedom to choose subjects, exercises and activities, are established. In this way, students can organise their learning autonomously, one of the priority objectives of this pedagogical theory, as Irene Gutiérrez points out, is "the person who must become what she is potentially and is called to be: singular, free and responsible; active, manager of her own development; autonomous and integrated; open to the world and to history (to science and culture), to other people, to transcendence" (2009: 182).

This new form of teaching proposes new methodological tools that make it possible to adapt the contents to the individual pace of the students, called Monthly or Weekly Work Plans and Directive Cards or Guide Cards. This educational instrument can be seen to have been used by the TI in the two centres under study: the public school Father Poveda and the private centre Véritas Institute. It was a teaching resource that provided an incentive to encourage the motivation of the pupils to learn. On the basis of a well thought-out programme, designed and elaborated by the teacher, the child selected the elements she wanted to learn at her individual pace, also respecting the principle of autonomy. The individual work plans depended on good programming. Faure's personal work plan technique is clearly influenced by the Dalton Plan and the Winnetka system (Pozo and Braster, 2017) -systems of individualised education emphasising individual learning and the social nature of school work- as well as by Freinetian pedagogy (Faure, 1981). The making of a personal plan was an apprenticeship for freedom along the lines of Bouchet (1951: 201).

Another elementary principle to be taken into account by the teacher will be the respect for the freedom and autonomy of students to organise their tasks according to their personal pace. The concept of freedom is the basis of human activity and is based on choice, acceptance and initiative (García, 1970: 33). The organisation of time is much more flexible and not as rigid as in traditional teaching. The teacher does not explain his/her lesson, but the students carry out their personal work, so that they can choose some of the activities proposed in the work plans (monthly, fortnightly or weekly). The guide sheets orients the activities, which can be compulsory or voluntary, and once the compulsory activities have been completed, students can carry out free work as a distraction or relaxation, such as drawing, reading, modelling, etc. Individualised teaching by guide sheets was not an original technique of Faure's; it had been developed by other educators such as Mademoiselle Deschamps, a disciple of Decroly, or Robert Dotrens, a teacher in Geneva and director of the Mail Experimental School, and also by Celestín Freinet in the Modern School.

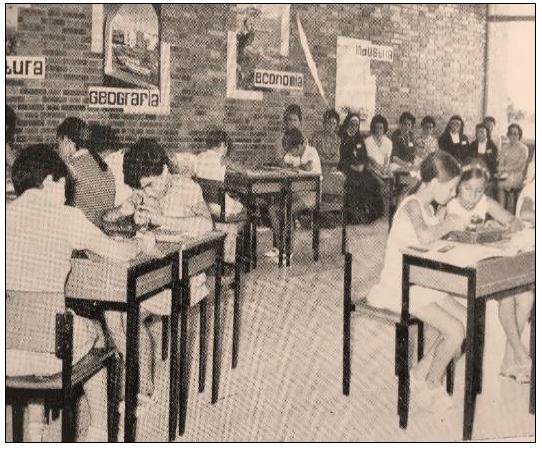

Individualised teaching required a new way of organising school spaces and furniture. As an example, we have selected some of these elements that contributed to the development of the personalist model of education. Unlike other public and private schools of the time, the organisation of the classroom reflects a break with the traditional units of time and space. It responds to Faure's idea based on the need to adapt to different levels, in the author's own words "thinking in equality of levels is an abstract vision of the teacher and not a real vision of the pupils. That is why we must, as educators, think of a variety of means and work instruments adapted to each one"13.

In relation to space, classrooms become flexible spaces for study and work, with shelves or furniture suitable with pigeonholes for students' dossiers and works, and they have a small library where they can research and consult various sources of information (Faure, 1981). It is important to stress out the importance of the library as a main working tool for students. This avoids the teacher's being the only one to speak. The arrangement of the tables is also adapted to the convenience of the teacher and the students, who can be grouped together when necessary, or work at individual tables, so that individual teaching and cooperative methodologies are applied and combined at the same time.

The French pedagogical model is applied in both centres, where the subject is enabled to "manage his or her own personalisation, configuring the theory and practice of a certain style of education called personalised"14. Ángeles Galino is in charge of basing the french personalised pedagogy and points out, quoting Faure, that "what it is important in the individualisation of work is not the material realisation of a series of exercises, even if they help to understand, memorise or apply a series of notions, but the invitation to the personal work, to the capacity to conquer and assimilate the notions."15 Therefore, the principle of activity was going to be essential in that students had to play an active role in learning situations, breaking with the traditional methods based on encyclopaedic knowledge, the memorisation of contents, the disconnection between school and what is learnt there and the life. TI mentions the influence of some authors of the New School movement such as John Dewey, learning by doing, or Froebel, when he refers to the fact that "progress must arise from a voluntary action carried out by the child himself". (Gutiérrez, 1971: 27).

The principle of activity will be associated with globalised teaching which aims to establish relationships between thematic contents and its reflection in reality, adapting to the specific needs of students and avoiding the departmentalised teaching of the traditional model. Father Faure insists on the idea that learning is not about acquiring notions of mathematics, grammar and geography as if they were watertight compartments, but about relating everything learned to each other. Globalisation was projected around a significant aspect of reality, by objectives - based on learning situations and learning units with internal coherence and perceived by the pupil as a whole, favouring interdisciplinarity - or by axis-ideas - consisting of integrating similar disciplines, structuring them into learning units. It implies the choice of aspects of reality with significance for the students. One of the globalising elements introduced in the Teresian centres was the wall poster around which the fortnightly or weekly thematic unit revolved. This material had an informative character and served to help understand the topics dealt with. They were displayed for a limited time so as not to lose their effectiveness.

Personal work is always followed by sharing with the rest of the classmates, it is the moment to share with the others the fruit of personal work (observation, information and documentation), to share discoveries and, in addition, to learn to express themselves in public16, what Father Faure called "the party in common": "each one or a few say what they have done and how they have done it, they are asked to take responsibility and are animatedand encouraged to improve it [...], it is the moment of truth"17. It is an act in which the teacher listens and so do the other children. It is insisted on the idea that the child should not say anything superfluous and should be well prepared. They used to be done at the end of each work session, at the end of the week or every fortnight. In accordance with Faure's pedagogical model, influenced by Freinet's innovative techniques, the assembly will develop the community dimension, complementary to individualised education.

From a didactic point of view, the sharing is an excellent way of rectifying errors, highlighting the most important points, clarifying, systematising and making final syntheses. It allows for feedback and participation of the whole class, which shows the progress made by the students. It is a collective lesson in which everyone shares their difficulties and achievements, facilitating dialogue and community learning.

On the other hand, the teacher should plan activities that develop the religious, social, human, intellectual, artistic and physical formation of the individual. Fundamental dimensions that integrate all the formative aspects of a christian person, as complete as possible. In this sense, we would like to point out some activities that encouraged artistic expression. It is linked to one of the essential pedagogical principles of the educational model of the Teresian centres: creativity, both at work and in free time. The aim was to encourage creativity through the knowledge of artistic works and the practice of life drawing, painting, modelling, etc. The life drawing classes were also carried out in the Father Poveda School, and although we do not have any corroborating images, we do have the testimonies of the pupils of that school18. The aim of artistic expression was to provide the pupils with techniques "that make personal expression possible, develop creative capacity and create habits of communication and criticism"19. Physical education also forms part of the integral conception of the pupils, contributing to the harmonious perfection of body movement and developing a series of habits such as team spirit, effort, responsible freedom, etc.

Finally, the optional activities were aimed at providing the pupils with opportunities to encourage personal initiative in terms of choice, freedom, responsibility and creativity. Music, drama, art, sports, crafts, laboratory techniques, collecting, library, languages, excursions, attendance at youth concerts and sports competitions with other schools were some of these activities. The testimony of one of the directors of the Véritas Institute illustrates the pedagogical ideology developed in this centre:

respondía al deseo y necesidad de crear un centro con los mejores métodos pedagógicos para contribuir a la educación y la cultura desde horizontes y objetivos acordes con el humanismo cristiano. Desde el centro se daba respuesta a una de las líneas fundamentales de la pedagogía: la educación personalizada, que diera como fruto personas autónomas, libres y responsables. Entre los principios presentes citamos el respeto a la individualidad y al ritmo personal de cada alumno, el ejercicio de la libertad, el principio de actividad, la preocupación por una formación equilibrada y armónica, la socialización, el rol desempeñado por el profesor… Quienes vivieron directamente la experiencia educativa del Instituto Veritas en aquellos primeros años, saben que lo que queda apuntado en el terreno de los principios fue una realidad en las aulas. Evidentemente se hizo realidad una renovación que animó a emprender otros modos de educación y de escuela distintos a los vividos hasta entonces.20

In view of the above, we believe that the documentary and iconographic sources consulted reveal that the system of personalised teaching was applied in the two Madrid schools run by the TA, with different public and private ownership. However, this pedagogical model shows differences depending on the social class of the pupils, conditioned by the socio-economic context in which the schools are located.

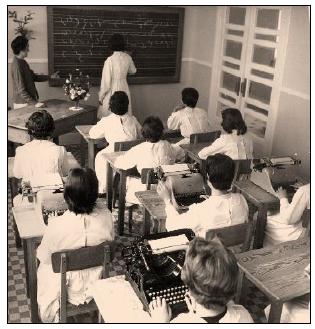

In the Father Poveda public school, professional activities were promoted to train future workers, mainly in the specialities of weaving and dressmaking. Many women worked as seamstresses in textile factories and for large commercial stores. Young women preparing the loom, weaving carpets, sewing classes, ironing activities, practising sewing with sewing machines, were a common sight in this school, which was well equipped with modern machinery with looms, sewing machines, irons, etc. Another of the most characteristic professional activities of the Father Poveda School was the training of secretaries for the students who excelled intellectually, through the teaching of shorthand and typing, as can be seen in the photograph. In one of the memoirs, the author mentions that these pupils were sought after by companies and factories to work in them21.

The concern of the TA led it to give a practical sense to the training received by the girls by creating a labour exchange, through which it placed them in workshops, factories, laboratories and commerce. The aim was twofold: to prepare for working-class society, but also to provide a solid religious and patriotic education. All this meant that the girls trained at Father Poveda offered a guarantee of job training and professional projection22. In the ideology of Father Poveda we find a harmony with the governmental directives because it was a public school. However, we can see that the ideology of this centre is far from some of the personalist principles of Father Faure, where primary education is seen as a preparatory stage for secondary education. Nevertheless, some of the oral testimonies mention that the brightest girls were prepared for the entrance exam for the first and second baccalaureate23.

Without neglecting the traditional academic curriculum, the school programme incorporated the teaching of drawing, painting, dance, modelling, sewing, leather and tin embossing, lace and embroidery crafts, choir, piano, looms, typing, shorthand, accounting... In short, everything that could be formative and useful for the future employment. Such was the T's concern for the girls' vocational training that, in the form of a manual of good practice, it drew up the profile of a good worker:

Conciencia del propio deber, sinceridad, tenacidad, buena voluntad, interés por el trabajo; perseverancia en el trabajo; paciencia en la ejecución; docilidad a las observaciones; adaptación al cumplimiento del trabajo juntamente con otros o a coordinar su trabajo con el del que sabe más; influir en los demás con el ejemplo; espíritu de adaptación; rectitud de juicio sobre el trabajo de los compañeros; trato respetuoso y cordial con los jefes; criterio de justicia sobre el contrato de trabajo; afán de capacitación personal para mejorar la producción. (TA Historical Archive, FIII/C65-45)

This training was a guarantee of entry into the employment exchange that the TI set up, through which girls were placed in workshops, factories, laboratories and commerce. Even for those students who excelled intellectually, secretarial training was offered by teaching them shorthand and typing. The centre was equipped with typing machines and specialised teachers to teach shorthand language. The aim was twofold: to prepare for working-class society, but also to provide a solid religious and patriotic education. All this meant that the girls trained at Father Poveda offered a guarantee of job training and excellent professional projection: "the certificate of having done primary education in the Father Poveda School is, in all industries in the area, a guarantee of ability, safety and honesty at work, as well as docility, respect and courtesy with the bosses and good companionship with the workers" (TA Historical Archive, FII/Cb3-45).

In conclusion

Personalised and community education was introduced in Spain from the 1960s onwards in two scenarios. On the one hand, from the scientific-university sphere, by the experimental pedagogy professor Victor García Hoz, through his extensive bibliographical production; and on the other hand, from the teacher training centres of the TA. This organisation managed to make a very "personal" application of the personalised education model by integrating the pedagogical ideology of the founder of the TA, Pedro Poveda, and the communitarian personalist principles of the French Jesuit, Pierre Faure. Likewise, the TA, from a more practical dimension, applied personalised education in its schools. To this end, it drew on some innovative methodologies that had been introduced earlier by the precursors of active pedagogy such as Pestalozzi and Froebel, or the New School movement of the first third of the 20th century, taking up John Dewey's principle of activity, some of Freinet's techniques, Decroly's principle of globalisation, the work plans of the Dalton Plan, or Montessorian pedagogy for the infant stage, among others. As the most significant contributions of the teaching model of personalised and community-based teaching, it is worth highlighting how the teaching-learning process is centred on the student and not on the teacher; how the teacher ceases to be a mere transmitter of knowledge and becomes a helper, a guide who guides the students in their own learning process, placing the focus of teaching on the child and not on the teacher.

It is paradoxical how such an innovative pedagogical project could be conceived and developed in a totalitarian context, such as Franco's dictatorship. We think that it was thanks to the Catholic basis of the Povedan pedagogy of TA and the christian personalism of personal and communitarian teaching, which could give certain guarantees to the Francoist government. We believe that this may also be due to the fact that in addition to being experimental pilot schools, they were schools with more freedom than other schools because they were in the hands of a christian-based organisation, in line with the catholic values of the Franco regime, to the extent that the Véritas Institute served as a pedagogical model for other schools and teachers, not only in the TI, but also in the rest of Spain and Latin America. The TA was shaping a pedagogical renovation movement in the 1960s, just as other pedagogical renovation movements were taking shape in public schools.

In the particular case investigated in this article, two TA schools in Madrid, we have seen how innovative methodologies were applied which encouraged the individualisation of teaching, through techniques such as work plans which favoured the freedom and autonomy of pupils, not to mention the principle of activity introduced by the personalised teaching system itself. New forms of school organisation were configured, transforming spaces, furniture, contents and school times, which allowed simultaneous activities and tasks in the classroom to be carried out by the students. New forms of student participation were introduced, with students sharing their progress, difficulties and learning progress. Cooperative work was also promoted and different creative activities such as theatre, music, painting (life drawing), walks, excursions, physical education, etc. were encouraged.

However, we have observed some differences between the educational aims of the two schools, conditioned by the social class of the pupils. In the public school Father Poveda, professional activities were promoted to train future workers, while in the private school (Véritas Institute), more creative and intellectual activities were promoted to prepare upper middle class girls for higher or university education.

In short, the teaching model based on personalised and community education, introduced by the TA, can be seen as a very advanced model for its time, since it achieved to introduce many educational innovations into the school, which were unthinkable or questioned by the ministerial authorities of the Franco regime. At the same time, its contribution to the education of women at that period should be acknowledged, being crucial and very relevant in Spain because it managed to overcome some of the barriers of Franco's discourse on women's education.

REFERENCES

Bouchet, H. (1951). La individualidad del niño en la educación. Buenos Aires: Kapelusz. [ Links ]

Dallabrida, N. (2018). Circulação e apropriação da pedagogia personalizada e comunitária no Brasil (1959-1969). Educação, 22 (3), 297-304, julho-setembro. [ Links ]

De las Heras, J. A. (1976). Testimonio personal: actitudes y procedimientos en la educación personalizada. Revista de Educación, 247, 65-79. [ Links ]

Faure, P. (1976). Estudios generales. La enseñanza personalizada, orígenes y evolución. Revista de Educación, 247, 5-10. [ Links ]

Faure, P. (1978). Entrevista a Pierre Faure. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 127, 135-139. [ Links ]

Faure, P. (1981). Enseñanza personalizada y también comunitaria. Madrid: Narcea. [ Links ]

Galino, A. (1965). Itinerario Pedagógico. Madrid: CSIC. Segunda Edición. [ Links ]

Galino, A. (1991). La pregunta por el hombre. En, V. García Hoz (Dir.), Personalización educativa. Génesis y estado actual (pp. 19-51). Madrid: Rialp. [ Links ]

Galino, A. (1991). El personalismo y la educación personalizada en Francia. En, V. García Hoz (Dir.), Personalización educativa. Génesis y estado actual (pp. 113-160). Madrid: Rialp. [ Links ]

Gall, M. Le. (1976). ¿Por qué y cómo una pedagogía personalizada? De los objetivos a las técnicas. Revista de Educación, 247, noviembre-diciembre, 11-20. [ Links ]

García Hoz, V. (1970). Educación personalizada. Madrid: CSIC. [ Links ]

García Hoz, V. (1974). La pedagogía de Pedro Poveda. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 127, julio-septiembre, 327-348. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez Ruiz, I. (1971). Experiencia Somosaguas (3ª Edición). Madrid: Iter Ediciones (Hoy Narcea S.A. Ediciones). [ Links ]

Gutiérrez Ruiz, I. (2009). El maestro de la Experiencia Somosaguas. Tendencias pedagógicas, 14, 181-189. [ Links ]

Institución Teresiana (2015). La Institución Teresiana y el Grupo Escolar Padre Poveda. Folleto conmemorativo del 75 aniversario del Colegio Padre Poveda. Madrid: IT. [ Links ]

Jiménez Ruiz, J.M. (1991). Introducción al pensamiento de Jacques Maritan. Madrid: Instituto Enmanuel Mounier. [ Links ]

Klein, L. F. (2002). Educación personalizada. Desafíos y perspectivas. São Paulo: Edições Loyola. [ Links ]

Le Gall, M. (1976). ¿Por qué y cómo una pedagogía personalizada? De los objetivos a las técnicas, Revista de Educación, 247, 11-20. [ Links ]

Macchietti, S. S. (1982). Pedagogía del personalismo italiano. Roma: Città Nuova Edizione. [ Links ]

Mencía, E. (s.d.). Un movimiento de renovación escolar en la línea de la educación personalizada. Madrid: Mimeo. [ Links ]

Peña, A. de la. (2011). 50 años del Instituto Véritas. Boletín informativo de la Federación Pedro Poveda de Asociaciones de Madres y Padres de Alumnos de Centros Educativos Institución Teresiana, 16, 16-17. [ Links ]

Pereira, M. N. (1976). Educación personalizada. Un proyecto pedagógico en Pierre Faure. Madrid, Narcea. [ Links ]

Pozo, M. M. del y Rabazas, T. (2013). Políticas y prácticas escolares: la aplicación de la Ley de Enseñanza Primaria de 1945 en las aulas. Bordón. Revista de pedagogía, 65 (4), 119-133. DOI: https://doi.org/10.13042/Bordon.2013.65408 [ Links ]

Pozo Andrés, Mª M. del (2003-2004). La Escuela Nueva en España: Crónica y semblanza de un mito. Historia de la Educación, 22-23, 317-346. [ Links ]

Pozo, M. M. del y Braster, S. (2017). El Plan Dalton en España: Recepción y Apropiación (1920-1939). Revista de Educación, 377, Julio-Septiembre, 113-135. [ Links ]

Rabazas Romero, T.; Ramos Zamora, S. (2018). The school child: two images of a pedagogical model in Madrid, 1960s. History of Education & Children’s Literature, 13 (1), 305-326. [ Links ]

Rabazas Romero, T.; Ramos Zamora, S. y Sanz Simón, C. (2019). Freinet pedagogy in the university. An innovative project in the History of Education. Paedagogica Histórica.International Journal of the History of Education, 55, 589- 607. [ Links ]

Rabazas Romero, T.; Sanz Simón, C. y Ramos Zamora, S. (2020). La renovación pedagógica de la Institución Teresiana en el franquismo. Revista de Educación, 388 (ab-jun), 109-132. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2020-388-449. [ Links ]

Ruiza, M.; Fernández, T. y Tamaro, E. (2004). Biografía de Enmanuel Mounier. En Biografías y Vidas. la enciclopedia biográfica en línea. Barcelona (España). Recuperado de https://www.biografiasyvidas.com/biografia/m/mounier_emmanuel.htm. [ Links ]

Sánchez, C. (1996). El movimiento renovador de la Experiencia Somosaguas. Madrid: Narcea. [ Links ]

s.a. (1988). El Padre Faure, líder de la Educación Personalizada en Murcia. Diario de Murcia, 754, abril, 33. [ Links ]

2Á. Galino. (1991). El personalismo y la educación personalizada en Francia, in García Hoz, V. Personalización educativa: génesis y estado actual (pp. 113-160). Madrid: Rialp, p.136.

4García Hoz, V. (Dir.) (1990). La educación personalizada en la familia. Madrid: Rialp; García Hoz, V. (Dir.) (1991). Educación especial personalizada. Madrid: Rialp; García Hoz, V. (Dir.) (1994). Problemas y métodos de investigación en educación personalizada. Madrid: Rialp; García Hoz, V. (Dir.) (1995). La personalización educativa en la sociedad informatizada. Madrid: Rialp; García Hoz, V. (Dir.) (1995). Del fin a los objetivos de la educación personalizada. Madrid: Rialp; García Hoz, V. (Dir.) (1996). Formación de profesorado para la educación personalizada Madrid: Rialp; García Hoz, V. (Dir.) (1997). Glosario de educación personalizada.Índices. Madrid: Rialp.

5The following article has recently been published to explore these fundamental aspects in more detail: Pérez Guerrero, J. y Ahedo Ruiz, JA. (2020). La educación personalizada según García Hoz. Revista Complutense de Educación, 31 (2), 153-161.

6Collected in a document on Pedagogical Principles of the Center. Veritas Institute. Archive of the Veritas Institute.

7Gutiérrez Ruiz, I. (1971). Experiencia Somosaguas (3ª Edition). Madrid: Iter Ediciones (Actually Narcea S.A. Ediciones), p. 17.

8Testimonio de Virginia Fernández Aguinaco. Folleto conmemorativo celebrando 75 años del colegio Padre Poveda, publicado por la Institución Teresiana, 2015, p. 14.

9s.a. (1988). El Padre Faure, líder de la Educación Personalizada en Murcia. Diario de Murcia, 754, abril, 33. Archives Lasalliennes, Fonds du Père Pierre Faure, S.J., España (1909-1988), 1P1-530.

11A handwritten document has been located, which details how a class and the material should be organized, just as the classroom represented in photograph XV: «The class is distributed in zones and on three planes, separated by some small stairs and a balaustrade. In each plane the activities are different: in the foreground, the lowest is the home area (drying rack, ironing board, dining service, cleaning corner with the necessary tools); in the background or intermediate area is the work area. The material is around the class on benches and tables. In the center the Montessori line for collective lessons and intuitive exercises. And in the third plane there are several corners: the religious, the library, manual work (cutting, gluing, painting, modeling)». Aplicaciones del método Faure a Somosaguas. 1965. Archivo Local de Madrid de la IT. F III/C.b.6/58. Caja 1.67, p. 1. Although not authored, we suspect that it was written by one of the teachers who attended Father Faure's training courses in France. It is a small memory where the application of the method in the Véritas Institute is described

12Le Gall, M. (1976).¿Por qué y cómo una pedagogía personalizada? De los objetivos a las técnicas, Revista de Educación, 247, 11-20

13Faure, P. Jornadas de educación personalizada. Cursos de formación del profesorado, Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, 15 de diciembre de 1973, Cfr. en Pereira, M. N. (1976). Educación personalizada. Un proyecto pedagógico en Pierre Faure. Madrid: Narcea, p. 107.

14Galino, A. (1991). La pregunta por el hombre. En V. García Hoz (Dir.), Personalización educativa. Génesis y estado actual (pp. 19-51). Madrid: Rialp, p. 51.

15Galino, A. (1991). El personalismo y la educación personalizada en Francia. En V. García Hoz (Dir.), Personalización educativa. Génesis y estado actual (pp. 113-160). Madrid: Rialp, p. 149.

18Folleto conmemorativo del 75 aniversario del Colegio Padre Poveda. La Institución Teresiana y el Grupo Escolar Padre Poveda, Madrid, 2015, p. 23.

20A. de la Peña, «50 años del Instituto Véritas», Boletín informativo de la Federación Pedro Poveda de Asociaciones de Madres y Padres de Alumnos de Centros Educativos Institución Teresiana, 16 (2011): 16-17, cfr. p. 17.

21García Alonso, M.L. (1959). Iniciación profesional femenina en el Grupo Escolar Padre Poveda, Op. Cit., p. 85.

23Some pupils confirm in their testimonies that the most advanced girls were prepared for the entrance exams for the elementary baccalaureate and for the baccalaureate revalidation exam at the Beatriz Galindo and Lope de Vega public secondary schools for girls. Most of the exams were oral and they presented a lot of material they had made themselves (collections of animals, plants, minerals, synoptic tables of history, science, etc.), demonstrating a high level of preparation, which was admired by the examining board. This higher education enabled them to opt for other professions, such as teaching, shorthand, secretarial work, conservatoire, etc. Folleto conmemorativo celebrando 75 años del colegio Padre Poveda, publicado por la Institución Teresiana, 2015, pp. 14-16.

Received: September 02, 2021; Accepted: December 10, 2021

texto em

texto em