including child in the community of philosophical enquiry

Through the exclusion of child as unable to contribute politically or pedagogically, to make determinations of what and how schools could work, or even what the im/possibilities could be, this frames child as deficit. Child is deficit in terms of the expectations of what children are capable of bringing, being, embodying and creating. Mathebula and Ndofirepi (2011, p. 127) argue that in “modern societies, including South Africa, children are still viewed as citizens-in- waiting, and as citizens who need to be inducted into their future role.” This deficit model of childhood is reflected in the construction of democratic citizenship education in post-Apartheid South Africa.” What questions can we ask about this image of child in South Africa and in the world? Who is this child? What purpose does this child serve? How does schooling and education work for this child? Although writing from a Western European context, Moss (2014) helps answer these questions. He argues that child is seen as a “fixed entity, with an essence that can be known, represented and predicted; as a reproducer of knowledge and values, whose task it is to acquire what we, in the adult world have designated as normal and necessary ... (p. 45)”. There is an accepted adult/child binary that is supported by the current and past education system in South Africa, where the authority is held by the adult teacher (Murris & Haynes, 2018). The work of this research is to contest this concept of child, in South Africa and beyond. I read a reframing of the inclusion of child in all aspects of schooling through this profound insight:

...we are accountable for and to not only specific patterns of marks on bodies-that is, the differential patterns of mattering of the world of which we are a part-but also the exclusions that we participate in enacting. Therefore, accountability and responsibility must be thought in terms of what matters and what is excluded from mattering. Barad (2007, p. 394).

The reconfiguring of the inclusion of child in school matters. Children endured the violence of Apartheid, which is not in a fixed past, but endures through the dynamic present(s) and future(s). Child (as concept) are habitually excluded not only from participating fully in all aspects of schooling, but also from making a difference to pedagogical choices and political imperatives affecting their schooling. Some of the work of this article is about reconfiguring the manner of including. What are the structures which enact exclusions, particularly of child? Philosophy with Children and its pedagogy, the Community of Philosophical Enquiry (CPE) has helped me think about what matters and what is excluded from mattering in school. Who and what else is routinely excluded? Under certain conditions, the CPE has the potential to be a democratising and transformative pedagogical practice (See, e.g., Echeverria & Hannam, 2017; Gregory, Haynes & Murris, 2017; Kennedy, 2010; Kohan, 2015; Michaud & Välitalo, 2017; Reed-Sandoval, 2019). In some ways it is practised and facilitated, the CPE also creates the possibilities for child to be included in the pedagogical decisions that affect their teaching and learning (Costa-Carvahlo & Mendonça, 2019; Stanley & Lyle, 2017; Vansieleghem & Kennedy, 2011; Elicor, 2017). This is very rare in South African classrooms where schooling is compulsory and children are taught a national standard curriculum which is followed in all government schools and some private schools.

In this article I share one of thirteen communities of philosophical enquiry I facilitated with a group of Grade 3 children in one government primary school in Cape Town, South Africa. An embroidered tapestry of the school, created by the principal in 1998 is used as a provocation for each of the thirteen intra-generational philosophical enquiries I facilitated at the school with children in Grades 1-7. Temporal and spatial diffraction (Barad, 2007, 2010, 2014, 2017) is adopted as a posthuman methodology to re-turn to the data in this experiential, dis/embodied and experimental research project. For this philosophical enquiry the group of Grade 3 children who consented to the research, their teacher and I used the school’s audio-visual room, a space without any desks, which is deliberately not the children’s classroom where we briefly discussed a tapestry designed and hand emboidered by the principal of the school, in 1998. The children were given some thinking time during which they were encouraged to draw their thoughts about the tapestry (their school), using their crayons, pencils or markers on large sheets of paper. Then, on their own or in small groups (they could choose) the children developed a question that they were curious or puzzled by which was evoked by the tapestry. Once back in the circle, one child from each group then reported to the larger group on their drawing and their group’s question. I then wrote each question onto a big sheet of paper, in large letters.The questions became the focus of our attention. Kennedy and Kohan (2008, p. 9) suggest that we should allow questions to do something with our thinking and that is to question. They explain that “[t]his implies that a question is interesting not so much because of what it is or it might be, but because of the movement that it can generate in the questioner and the questioned” (Kennedy & Kohan, 2008, p. 9).

Laverty and Gregory (2018, p. 1) argue “in a community of inquiry, people with diverse experiences, ideas and concerns join in dialogue around a shared question...” These shared questions are essential to a CPE. It matters that questions are asked and it matters deeply that the children create the questions, or allow the questions to emerge from the provocation presented to them. Very often in schools, teachers ask questions and the role given to children is to simply answer them correctly (or not). Oliverio (2018, p. 69) argues, “the classroom community of inquiry is the domain where students are led to recognize their own beliefs and are at the same time, constantly challenged and shaken out of their complacency.” The questions that emerge help challenge the children to question their beliefs and create a different kind of accountability to the process of learning they are engaged in. This is a radical reconfiguring of an early childhood education classroom. The facilitator of the CPE is what Murris (2016, p. 182) calls a “pregnant stingray.” This posthuman figuration of ‘teacher’ sees their role as a “co-enquirer, a participant that ‘numbs’, asking questions that provoke philosophical enquiry, without knowing the answers to the questions s/he poses; and facilitating only where appropriate, that is benefiting the community’s construction of ideas” (Murris, 2016, p. 182). This kind of questioning by the “pregnant stingray” is very different from the usual questions asked in classrooms where one word answers are expected or only answers that are uncontested. Matthews (1994, p. 5) suggests that once children have been in school a while, “they learn that only ‘useful’ questioning is expected of them” which, through my observations generally appears to refer to questions of clarification about what the teacher or activity wants of them, not what could disrupt the status quo.

I argue that the questions developed by the children make new ways of ‘being’ possible in the classroom and create conditions for deeply meaningful intragenerational dialogue and learning to occur, which disrupts and destabilises the adult/child relations in a classroom. Sharp (1996/2018a, p. 180) suggests that “to question is to take a stance of curiosity or challenge toward someone or something, which constitutes a relationship of freedom in regard to it.

developing the questions

A question that propels this research is ‘Where is the place for philosophical questions and the kind of philosophical thinking/drawing/creating/being for child (and adults) in schools? How do we make space for such questioning- so that the richness of these pedagogical encounters can really matter and make a difference to the teaching and learning taking place? A CPE creates the space for children’s thinking and deep wonderings. This is made possible relationally as part of a pedagogical encounter in between adult-child-art-floor-space-land-history-philosophy. As I read and re-read the children’s questions the children have developed I am affected by the depth and breadth of thinking required to start answering them. Matthews (1994, p.13) suggests “much of philosophy involves giving up adult pretensions to know.” Therefore, when I look at these questions as a philosopher and educator, I do not have the ready-made answers and this response excites me. This act of questioning destabilises the adult/child relationality in this classroom. Also, answering these questions requires care, collaboration, creativity and criticality in thinking as a ‘group’, not as ‘individuals’. The answers are about developing hypotheses, imaginings, dreams and yearnings for new and different ways of knowing/being together. Being able to ask a question that does not immediately open a door to an obvious answer brings to the fore the multidirectional relations that exist between questioner, questions and answers. This is the kind of learning and teaching that is valuable and worth engaging in because it shatters who controls what matters. Haynes (2008, p. 41) reminds us that philosophical questions asked by children have profound mystification and they are drawn from beyond the confines of what are usually considered bounded school subjects.

These are the questions the children came up with in their groups:

How long will it be until the school breaks up and dies?

Why are there ink pens?

Why did XXXX make it? (The name of the principal has been removed)

Will there be sport when we are older?

What will happen to the animals if the school falls down?

Matthews (1994) argues that “philosophical thinking in children has been left out of the account of childhood that developmental psychologists have given us” (p.13). The expectation is that the questions above are unusual or unexpected and therefore may not necessarily be philosophical in a usual early childhood education setting that focuses on a developmental account of childhood. I think through what Gareth Matthews has suggested and realise that I cannot really imagine talking to a teacher colleague about the school which is the research site no longer being in existence - and asking this question: ‘How long will it be until the school breaks up and dies?’ Yet, this question was conceived of and asked by a 9-year-old in the CPE. I acknowledge that it is entirely conceivable that the school could catch alight and burn to the ground or that a nuclear event could decimate the entire city of Cape Town (Koeberg Nuclear Power Station is only 20 kilometres away from the city centre). Matthews (1994) points out there is a “staleness and uninventiveness” brought on by maturity, which is why he rejects the evaluational assumption built into the stage/maturational model of child development (p. 18). Thinking about the school breaking up and dying forces me to think differently. Matthews (1994, p. 122) calls children the ‘natural philosophers’ - adults can only cultivate that kind of wonder (artificially).

questions stretching across traditional school subject boundaries

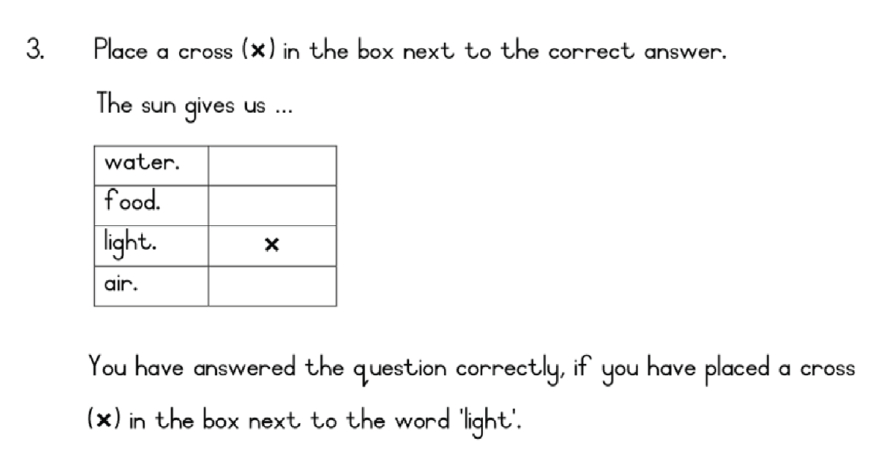

Often the questions asked by children in philosophical enquiries, stretch across traditional school subject boundaries. Yet, most questions found in standardised tests and exams for Foundation Phase children in South Africa tend to be limited by the defined categories with human-made taxonomies and boundaries of Mathematics, Literacy and Life Skills, the only three designated ‘subject areas’ in the South African birth-9 curriculum. We find these kinds of questions in large scale standardised tests and exams regularly administered to children in South Africa. According to the Bua-Lit Collective (2018, p.10) “Typically, literacy tests - particularly large-scale tests - measure what can be quantitatively analysed. This leads to an emphasis on words and small segments of language that are taken out of context… decoding words is not the same thing as literacy as a social practice. Tests reinforce a narrow view of what literacy means…” For example, in South Africa from 2010-2015, a test called the Annual National Assessment (ANA) was administered to all the Grade 1-9 children in Literacy and Mathematics who attended government schools. See below for an Exemplar from the Grade 3 First Language Literacy ANA - The sun:

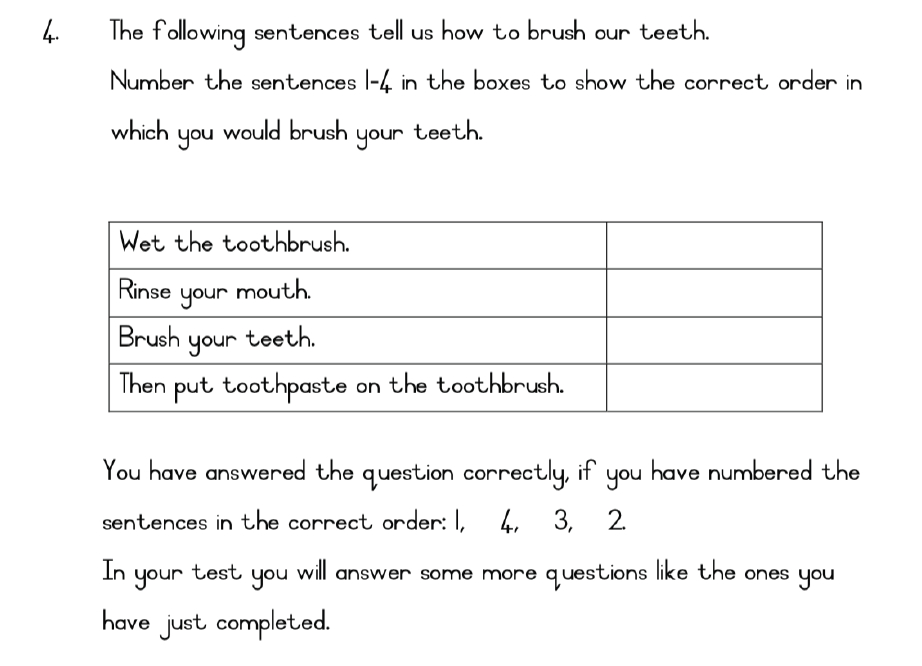

Exemplar from a Grade 3 First Language Literacy ANA - The toothbrush:

These questions reinforce a Newtonian understanding of knowledge, where cause and effect explain most of what needs to be learnt and understood in schools. The order of brushing your teeth could happen in many different ways, not necessarily in the order the examiners have provided as ‘the truth’ and the right way. The question about the sun also offers a very limited understanding of the sun by implying that it only provides light. If this was true there would be no human left on earth to write the Annual National Assessments as all forms of life would have perished. This kind of question speaks to the formulation of child who the group of adults (only adults design tests of this nature for children to take) has envisioned as needing to write this test. A child who has no power to question the accuracy of the question being asked or the answer being provided as a given. I put forward that this is a kind of epistemic violence which children have to endure in most of their schooling. They are not being taken seriously as knowledge producers, or are afforded the dignity at 9 years old of knowing that the sun provides the planet with heat, light, warmth, food through complex and very simple processes and and and ...

The questions the children come up with in class are often dismissed or not given the chance to be heard - or as Kohan (2014) suggests allowed to generate movement in the question or the questioner. This kind of movement is not encouraged in transmission-based teaching. Philosophical questions on the other hand are powerful and can contribute to a de/colonial politics of childhood (Rollo, 2016, p. 33) for many different reasons. Epistemologically - what knowledge is; ethico-politically: because they disrupt ways of knowing and being that maintain the colonial relations of adult vs. child, known vs. to-be- known in this post-Apartheid school setting. Also, as an invitation to transdisciplinary work where subjects are not bounded by false demarcations.

I agree with Matthews (1994, p. 17) when he claims that children’s questions have a “freshness and inventiveness that is hard for the most inventive adult to match”. Without being sentimental or romanticising the five questions above I suggest that they share these properties of freshness and inventiveness. I question what conditions need to come into existence for a child to ask, to care enough, to want to know:

how long will it be until the school breaks up and dies?

The question, ‘How long will it be until the school breaks up and dies?’, has the potential to bring up the philosophical concepts and entanglements related to death, mortality, immortality, life, birth, rebirth, reincarnation, animism, more-than-human, school, education, learning, time, temporality, depth, movement, statis, change, destruction, organic/inorganic, materials, sand, trauma, fire, dust, connection/disconnection, void, noise, silence, cycle, expectation, fantasy, reality, imagination, knowledge, known/unknown, beginning, ending, maths, science, story, narrative, physics, chemistry, history, geography, recycling, politics, art, justice, belonging, inclusion/exclusion, possibility/impossibility, fracture. This is an incomplete list. Deleuze and Guattari (1991, p. 2) suggest that “philosophy is the art of forming, inventing, and fabricating concepts.” I would argue that this is exactly what the children, the questions, the colours, the paper, the pvc tiles, Apartheid South Africa, fires, burning, narratives of life and death and all in between are in the process of doing. This is a process of philosophising.

In the next section of this article we will discuss voting on the questions and why this matters. A way to choose ‘the question’ that has become standard practice in a CPE, and specifically the way practitioners of PwC whom I have learnt from, practice, is that the children, not the teacher/ facilitator create the questions and vote on each question. The question which receives the most votes is then discussed. This process can be viewed as a democratic practice. Democratic practices rarely apply to all humans and seldom to children, especially children in early education childhood settings and primary schools, not just in South Africa.

voting on the questions

After sharing their drawings and their questions with the group, it is time to vote on the questions to see which one holds the most intrigue for the children and which one will start off the philosophical enquiry. This is the process of PwC as it tends to be taught.

As I re-turn to the co-created data through video-recorded footage,I pay attention to the circle formation that the children are seated in, created by the chairs, which changes shape as the children leave their chairs. They are using buttons to vote which they are placing on the poster on the ground, which holds the questions they have developed. They are voting on the questions. There is a drawing nearer to each other, to the colours, to the questions to the carpet, to the earth and the land. I re-watch and re-listen to the data created via the video recording and I think with Murris and Menning (2019, p. 2) and do not read the video recorded data as an “objective, neutral methodological tool” because the ethics are implied, entangled and present. I know too that I am limited by my human ways of seeing and this video-recording makes a different re-membering of the event possible. I am excited that my theoretical framework of critical posthumanism gives me a way to make sense of, and to “shift the role of the researcher using videography in educational settings” (Murris & Menning, 2019, p. 3), because this is not an event I am looking back at, to write about now, in ‘this’ ‘present’. Temporal diffraction (Barad, 2007, 2014, 2017) means that the event is not over and has not already happened. Temporal diffraction changes how we understand what we are seeing and are implicated in. The video recording is not of children playing, thinking, philosophising, voting, speaking or learning in a container of space and time, in 2017 when the CPE took place in chronological time. Posthumanism and the notion of temporal diffraction explode the notion of ‘there’ and ‘then’ and ‘here’ and ‘now’ - and this is how I read ‘this’ video-recording. It is still in its becoming. I am challenged by Murris and Menning (2019, p. 3) who illustrate in their introduction to a special journal issue, through various examples that the “indeterminacy and uncertainty of this ontological shift in research opens up possibilities to evaluate children’s movements differently, troubling hierarchical relationships between younger and older humans.” The apparatus of the CPE as research which the children are participating in, is where the thinking, learning, evaluating and creating is happening through the intra-actions that are emerging.

What makes voting in this particular way possible? Michaud and Välitalo (2017, p. 28) argue that a traditional model of authority in a PwC classroom would be a constraint to the ethico-onto-epistemology flexibility. I diffract through this theorising as I confront this question: ‘How long will it be until the school breaks up and dies?’ The question would not fit into the desired format of the classroom - where the “teacher is in authority...her authoritative role in the classroom comes from her knowledge” (Michaud & Välitalo, 2017, p. 28). In other words, the teacher would need to know exactly when the school would break up and die in order to answer the question. In contrast, in an anarchic model of authority which is seen as “radically student-centred” the students control how learning happens in the classroom (Michaud & Välitalo, 2017, p. 29). This is not the case in the enquiry above. I did not give the students complete free reign on the choice of the provocation (the tapestry) and how they would find themselves asking these questions. As a teacher/researcher very deliberate “agential cuts” (Barad, 2007) were made - about the choice of provocation, where and when the lesson happened, why we walked to the foyer to see the tapestry in situ, how they worked in pairs, the time given for thinking and the art materials and paper provided for creating artworks that made their thinking visible.

The so-called “shared model of authority” as suggested by Michaud and Välitalo (2017, p. 29) is what helps to destabilise the unequal adult/child relations in this lesson. According to a shared authority model (Murris & Haynes, 2020, p. 32) the authority in this lesson does not reside within the teacher, or within the children and I would add not within the more-than-human, but a more complex relational model of authority becomes possible. As the facilitator I am not there to tell the children what to think, I have guided the process, but not controlling the event, although I am in a position of authority.

how voting usually works: learning with Mangaliso Nxesi

In 2018, 10-year-old Mangaliso Nxesi addressed the Republic of South Africa’s parliament and made the following statement: “...just because somebody has a different age than another person does not necessarily mean that they should have less access to things because of their age or anything like that...” He was referring to the fact that children in South Africa cannot vote and participate in the election of government leaders and the national president until they turn 18. Mangaliso was building a specific argument about the exclusion of children from the national voting process and was asking the parliamentary committee to consider his suggestion. Children are not just excluded from national voting processes as Mangaliso Nxesi reminds us, but are also excluded (not included in) from participating in decisions about what and even how they are learning at school.

“So my question, which is not really so much of a question...well it is kind of like a statement, so...let’s say we are in let’s say we are in 2019 and it is the elections and a child wants to vote, but they don’t have that opportunity to vote because they are under age...what if...we make this change...what if...the child studies and studies all the things that different political parties want to um change in the country and they understand the depth of what they are doing and they go through one or two assessments and they have like the voting intelligence of an adult, coz just because somebody has a different age than another person does not necessarily mean that they should have less access to things because of their age or anything like that. But like um, many adults expect children to be um ...to not have as much intelligence as adults, but if the child has surprisingly high intelligence...

[laughter from the members of parliament] he stops briefly to look towards the sound of the laughter

...but they are still not allowed that just because of their age. It’s not because of what’s on the outside [gesturing with both hands, palms turned upwards], it’s because of what’s on the inside.”

[applause from the members of parliament] ...

(Transcript from YouTube clip on 11 July 2018)

Acknowledging the full equality of children is transformative of society itself because it necessitates a fundamental rethinking of democratic ideals and institutions around the particular capacities of children. Politics presupposes difference and disagreement. Where there is undifferentiated uniformity, there is no politics. Political equality, then, is the form of equality we establish between people with diverse interests, ideas, identities and capacities. Establishing the formal equality of people with diverse capacities is a necessary part of the anti-colonial shift that democratic politics offers. Recognizing the political equality of children means recognizing that speech and reason can no longer wholly define politics. What we need to get there is a decolonial politics of childhood (Rollo, 2016, p. 33).

Mangaliso Nxesi does a remarkable job of contextualising and then making his statement about the voting age and his proposition about children voting. It is clear he has internalised adult discourses about children vs adults in terms of what is and is not allowed in a functioning democracy like the Republic of South Africa. Voting is reserved for adults, denied to children. His formulation of his statement is focused on the perceived intelligence and what would enable an adult to vote - intelligence, rationality, thought and reasoning. Voting and participating in a democratic process in this way is a no-go area for children. After he is interrupted by the laughter of all the members of parliament, he pauses, recollects himself and then continues. It is difficult to be in parliament, as a child, specifically a black child, in a place that breathes coloniality, patriarchy and childism. Rollo (2018, p. 317) who draws on the work of Chester Pierce refers to childism as the “societal prejudice against children.” and uses the term in respect to an oppressive power relation like racism. John Wall (2022, p.260 ) whose work on childism while deeply rooted in the field of childhood studies, differs from it in that he argues that “childism focuses on transforming understandings and practices, not just around children themselves, or even around child-adult inter-generationality, but also around the pervasive normative assumptions that ground scholarship and societies overall.” Wall (2022) has redefined the original definition of childism, so that it is not only connected to deeply oppressive power structures like racism. The two different uses of the term (how it is used by Rollo and Wall) have different disciplinary traditions.

The conversation and discussions about children’s rights to vote can be found across many disciplines. For example, Lecce (2009, p. 133) argues that the continued political disenfranchisement of children is a form of social injustice. He suggests that we look at proceduralism and children’s right to an open future to think through lowering the voting age, this is in order not to only make the argument about ageism. “Lowering the voting age will be one way of encouraging children to take more active interest in the values, processes and results of political decsion-making” (Lecce, 2009, p.137). Wall (2011, p.86) argues that existing conceptualisations of democracy are the reasons for the exclusion of children from direct political representation. Children are considered citizens, yet exercise very little actual political influence over their lives (Wall, 2011 p. 88). While there are many well theorised arguments for or against the lowering the voting age for children, “arguments against children’s suffrage are premised on an adult-centred conception of political representation “(Wall, 2011, p. 97). I agree with Wall that democracy can represent children, only if it is fundamentally reimagined (Wall, 2011, p.98). There however, seems to be fewer and fewer reasons for this reimagining to take place - certainly in the South African context where Mangaliso Nxesi lives.

Joseffson and Wall (2020) argue that global justice for children and youth can be addressed by what they theorise as empowered inclusion, a transformative social justice. Children and youth are not just disempowered because of their age, but there are multiple factors which contribute to the marginalisation which children continue to be confronted with. “…global injustice is not just a problem of marginalization from power, but, in addition, one of deep reliance on others for standing together with children in their justice struggles (Joseffson and Wall, 2020, p. 1050).

There is a deep interdependency in the global arena which is often ignored and at the expense of children and youth. This means the response from the global community, with all its facets needs to be different. Joseffson and Wall (2020) advocate for expanding children’s rights to vote by lowering the voting age for example, because their empowerment must be connected and deeply rooted in disrupting the historical processes that contribute to their continued disempowerment.

come and vote

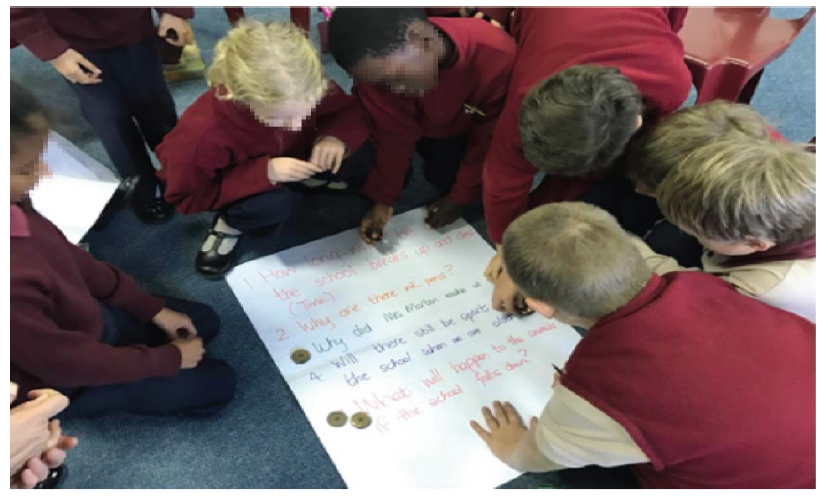

In order to vote for the questions they are most interested in as a starting point for the enquiry, I give each child two oversized brown buttons to use to cast their votes. There are heads, paper, hands, colour, feet, bodies, legs of maroon chairs and blue carpet in the photograph in Figure 1 below. In the top left hand corner the left hand of the child’s body is clenched, gripping the oversized brown button. The straightened body without head visible, waits to vote. The chair legs are parallel to the human legs. There are feet pointed outwards and the hands folded towards each other holding the oversized button. A tilted-head, leans to the right to aid with the reading. A hand hovers and casts a shadow over the red words. Another hand, palm down, five fingers outstretched as a stabiliser, leans on the bottom of the poster. Four heads, five heads, six heads bow together, all looking down, three more hands on the poster. Then kneeling, waiting, decisions already made and yet to be made.

The question with the highest number of votes will be the question that is explored in the philosophical enquiry to follow. There is hunching, leaning, squatting on haunches and sitting down with knees on the ground, bottom on the backs of legs. Hands leaning on the poster for support, buttons on the paper, three on the left, two close together and one on the number three. There is a leaning over of a child closer to the poster and placement of a button obscured by a head. Why does this matter? It matters because the idea that children can make decisions about what they will learn in class is generally ignored. Benjamin and Echeverria (1992, p. 64) argue that “the teacher therefore takes the most active role in the classroom”, the one who gets to move, leave and enter without permission, and make the most important pedagogical decisions. In this activity though, the children are also making important pedagogical decisions, about how the lesson will proceed next in terms of content. This process can act to destabilise the various established roles in the classroom - for example that the teacher/facilitator is making all the decisions that matter.

There are now 14 buttons on the poster. There are fingers close to the mouth in the right-hand corner, thinking and listening, about to make a decision and yet to be moved away from the mouth. The arm outstretched pointing, but not putting down the button yet. Arm, button, poster, fingers, thoughts, reflexes, movement all in decision making together. Not the usual expectation for adult voting, which is always shown to be an individual exercise, contained well within the human subject, as if this is ever possible.

There is a hum in the room as the children leave their chairs in the circle and move inward and forward to vote and then back to their chairs again. One boy motions with two fingers to his friend to come and vote. Pedagogically this is a significant moment in this philosophical enquiry. I think with Michaud (2020, p. 39) who suggests a “pedagogy of interruption” is what education should be about. Michaud (2020, p. 39) argues that “education is...about creating conditions ...which requires interrupting the normal flow of classroom life, activities, and thinking.” The voting creates this pause and interruption. The children deliberately and intentionally interrupt the flow of what could be a traditional lesson. I cannot know and neither can they before the time, which question will get the most votes and therefore be a continuing point for our philosophical discussion. The ‘moments’ in time that are, and are not evident, in the photographs above, show how an emergent curriculum comes into be(com)ing. A school is essentially an adult-dominated institution, where children are given very few opportunities to express their preferences (Chan, 2010, p. 40). The two questions which get the most votes are: ‘Will there still be sport at the school when we are older?’ and ‘What happens to the animals if the school falls down?’ which has a clear link to the question 1: ‘How long will it be until the school breaks up and dies?’

political rights and moral rights for children?

Besides arguing for lowering the voting age, Mangaliso was also making a point about something more radical needing to occur for example the empowered inclusion of children (Joseffson and Wall, 2022) and children’s continued political disenfranchisement as a social justice concern (Lecce, 2009). As parliaments and governments are designed by adults for adults who will in turn (hopefully) care for children. Mangaliso is also showing through the responses from the adults in parliament the ontoepistemic injustice (Murris, 2016) that children face. The inability to be taken seriously by the adults they interact with. The argument I am making here about voting is not only related to lowering voting ages, but also what the voting makes possible, in a classroom in South Africa, where a national standard curriculum is in place that children have to follow with very little choice. Abebe and Biswas (2021, p. 121) argue for education to also be “co-generational” in that they “ refer to a childist understanding of educational relationality that moves away from the hierarchy of adults as teachers and children as learners to instead fostering horizontal educational practices, with children and adults as co-learners .” The pedagogy of interruption which Michaud (2020) argues for, would be possible with co-generational learning in a classroom, in a CPE where the adults and children together are exploring what else is possible when normalised, rigid ways of being in classrooms are disrupted.

What the children in the philosophical enquiry are doing is not simply mimicking what adults do when they vote. This step in the CPE is not only about voting as a solitary, bounded subject. The children in the CPE are not simply voting so it can mimic a future action they are currently denied participation in. Rather, the voting in the philosophical enquiry (which is open to collaboration, discussion, and participation), is significant as it is about the kind of change which gives the child in the classroom political rights about decision-making of a pedagogical nature. Rights, usually reserved for the teacher who has the authority to determine what should be learnt and how. The purpose of this process from developing the philosophical questions to the voting on the questions as developed by the children, could be to decide what to learn about, how to work in a group, the way to present knowledge, whether to always work at a desk, on a chair or at a table, how to draw and create art in a classroom or other such enquiries. This process disrupts what the possibilities are for learning, talking, thinking, silence, drawing, being and becoming. What is also significant is the inequality that exists between the adults and the children, and the more-than-human others including the land in the classroom is not done away with - it is worked, recognised and paid attention to in a way that disrupts the usual flow of knowledge production. Adults and children, the questions as material-discursive, the buttons, the poster, the colours, the carpet are all entangled with the philosophical enquiry.

Mangaliso Nxesi (2018) argues that “just because somebody has a different age than another person does not necessarily mean that they should have less access to things because of their age.” He makes the same argument philosophers Murris (1997, 2016, 2021); Matthews (1994); Haynes (2008); Kohan (2014); Sharp (1996/2018) have made, about the marginalisation of children, in relation to adults and usually, but not only based on their age.

The conventions that maintain the status quo in schools reinforces the way children remain unable to make significant pedagogical decisions, because adults refuse to give up that power. Rollo (2016) argues that “whatever we wish to name it, the exclusion of children is a remnant of colonial injustice, the preservation of which has a profound impact on modern politics” (p. 32).Therefore the othering of those who are younger works for the capitalist model, where some can be disenfranchised and so the plants, water, animals, precious stones, air, space, the depth of the ocean - can all continue to be manipulated by adults who are the only ones making decisions for all who co-exist on the earth and in the cosmos. When children are given political rights as well as moral rights it will change the kind of learning that is and could become possible in school. CPE’s can facilitate the changing roles of the children, adults and the questions and votes reconfigured and understood as the more-than-human. Also, developing questions and then voting on them becomes a pedagogical practice because the choice about what is possible to learn is no longer only determined by the adult in the classroom but also by the children. This is a pedagogy of interruption (Michaud, 2020) in a schooling system which Abebe and Biswas (2021, p191) remind us is built on knowledge transmission. Philosophy with Children and its pedagogy, the community of philosophical enquiry provide ways to think differently about schooling with a changing adult teacher role and through what child(ren) already offer and have always brought to the learning process. The CPE can show what is possible when pedagogical practices like developing and voting on questions, which children recognised as political and moral agents, are engaged in are taken seriously.