Introduction

Motivation and engagement are the main goals in using gamification (KAPP; BLAIR; MESCH, 2014; ZICHERMMAN; CUNINGHAN, 2011). Gamification is about the use of game mechanics and game thinking in non-game contexts (DETERDING; DIXON; KHALED; NACKE, 2011) to any projects, even in education (WERBACH; HUNTER, 2012). According to Kapp (2013), this strategy can improve learners’ performance in learning. The purpose of the work described in this paper is to understand if the use of a game design strategy can help adolescent Brazilian students with dyslexia to be motivated and engaged in a reading activity, and also to verify if it helps to increase students’ awareness about their dyslexic difficulties.

Gamification is not about points, badges, leader boards or programs that help students to have fun or fulfil activities at school; instead, it is about being involved with compromise and feeling motivated (VILLAGRASA; FONSECA; REDONDO, 2014). In the specific case of students with dyslexia, motivation is essential because these learners are constantly feeling demotivated in academic activities (CARVALHAIS, 2010). Hence, they need to feel they can overcome their difficulties in reading, to develop new skills and learn new skills.

This paper presents a study developed with students with dyslexia and teachers of special education of two schools located in the city of Belém, in Brazil, and describes part of a PhD research entitled Gamification in the learning of reading of Brazilian Students with dyslexia, developed in the Doctoral Programme of Multimedia in Education of Aveiro University, Portugal. Its methodology applied is qualitative: scales and opened interviews were applied aiming to get feedback of the participants about the test of a prototype described as a gamified storytelling tool. Specifically, the study aimed to understand if: (i) the inclusion of game design elements provides more engagement and motivation; (ii) the use of a gamified storytelling contributes to students’ learning. Data was collected through the students and teachers’ perspectives about the game mechanics used in the prototype.

The first section of this paper presents a briefly overview about the concept of gamification, research on gamification and dyslexia, and game design elements. Section named Procedures and Study Design includes the design of the prototype - a gamified storytelling resource. The main results are present subsequently; and a discussion and conclusions about the participants understanding of the contributions of the game mechanics to motivation, engagement and learning is presented in the last session.

Gamification

Concept of gamification

The basic idea of gamification refers to the use of game elements in non-game contexts (DETERDING; DIXON; KHALED; NACKE, 2011), for other non-entertainment purposes and with other aims besides the game itself (SAILER; HENSE; MANDL; KLEVERS, 2013). In this definition, three important components may be outlined, as described below.

- Game elements: games are composed by essential elements found in several kind of games (SIMÕES; REDONDO; VILLAS, 2015), and help to distinguish gamification from serious games (SAILER; HENSE; MANDL; KLEVERS, 2013);

-Non-game contexts: the area of the use of gamification is broad, therefore, gamification involves the application of game mechanics in various areas as marketing, business and education (WERBACH; HUNTER, 2012;ALVES, 2014);

-Non entertainment purposes: gamification is used with diverse aims making this strategy different of common games (SAILER; HENSE; MANDL; KLEVERS, 2013).

This concept helps to understand that gamification does not refer to a complete game (DETERDING; DIXON; KHALED; NACKE, 2011), being necessary to differentiate it from “other concepts related to gaming and provides a basis for investigations without constricting the phenomenon” games (SAILER; HENSE; MANDL; KLEVERS, 2013, p. 30). The purpose in using gamification is, therefore, to use game mechanics, dynamics and aesthetics to promote users’ motivation and engagement (ZICHERMMAN; CUNINGHAN, 2011), in solving problems, and also too support learning (KAPP; BLAIR, 2014). Gamification is an instrument focused on people and supposed to be an effective strategy to explorer the levels of engagement of an individual and, so that foster motivation (KAPP, 2013; WERBACH; HUNTER, 2012).

Research on gamification and dyslexia

According to Marques (2014), games are seen as relevant tools to support the learning process of students with dyslexia, since they can contribute to the development of reading skills. In the educational field there are various works describing games potential to support children/teenagers with dyslexic difficulties to overcome their literacy difficulties.

Specifically, literature show how video-games can help in reading accuracy and attention (FRANCESCHINI et al., 2015), and in supporting grapheme-phoneme correspondences skills of decoding and second-grade learners with impairment in reading (RONIMUS; EKLUND; PESU; LYYTINEN, 2019). The serious games have also been described as important tools to detect dyslexic difficulties in pre-readers (GAGGI et al, 2012), as well as the game apps to perform phonological exercises (RELLO; BAYARRI; GORRIZ, 2012) and the web-based games to early identifying dyslexia (RELLO et al, 2016).

Despite these findings, there is a restricted number of studies focusing on game design when describing gamification solution to support the learning process of students with dyslexia. Authors as Gooch, Vasalou and Benton (2016) used the platform ClassDojo with children with dyslexia in order to verify how gamification can provide learner’s motivation due to the pedagogic appropriation and creative use of the platform by teachers. Also, Saputra (2015) created a gamified tool named Lexipal to foster engagement of children with dyslexia. Rello et al (2016) with the purpose of predicting risk of dyslexia in Spanish children also tested an online gamified tool. Additionally, the company Learning Dragon announced, in 2018, the creation of gamified platform - dyslexia dragon- with the purpose of helping learners with dyslexia in reading and spelling skills (KRONK, January 11, 2018)

In view of the contributions presented above, there are reasons to deepen knowledge on the role of gamification to help students with dyslexia, namely as a learning strategy to: promote motivation and engagement (ZICHERMMAN; CUNNINGHAN, 2011); monitor and assess learning achievements of students’ engagement in learning of reading skills (SAPUTRA, 2015); and support reading in a faster and efficiently manner (FRANCESCHINI et al., 2015).

It’s, therefore, important, to better understand how gamification can be used in special education as an effective tool to monitor and assess learners’ difficulties and needs and to improve their skills. Gamified should be tested in order to ensure that they are aligned to pedagogic purposes, and that they present effective contributions to affective and learning achievements.

Materials and Methods

Case Selection: participants

The study design that supported the research presented in this paper was based on an immersive process developed with 4 participants: two adolescent Brazilian students with dyslexia of two Brazilian Elementary Schools and four teachers, aimed to conceptualize and test a gamified storytelling tool.

Study Design

This study follows a qualitative approach, which means it is interested on creating meaning as a central concept (COUTINHO, 2016), and on building of meanings in the context investigated. Its main methodological inspiration is Design Thinking, an iterative and human-centred approach applied to define solutions with the purpose of solving problems (CARROL, 2014). The research process was conducted in four adapted phases, as seen in figure 1:

These phases represent the process of creation of a gamified prototype and each one of them fulfilled specific functions, as shown in table 1:

Table 1 Functions of the research

| Phases | Functions |

| Exploration and immersion | Explore the educational context where would be proposed the use of gamification |

| Analysis and Definition | Analyze and cross the data collected in order to redefine the strategical challenge of the process |

| Ideate | Creation of the gamification plan in collaborative sessions with student and teachers |

| Prototype | Prototype of the gamified system |

| Test | Testing prototype and getting feedback with the purpose of iterate. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors

The phases of the whole process resulted in the creation and testing of a prototype of a gamified storytelling.

Data Collection

Participants took part in sessions of activities during the prototyping phase of the gamified tool. Along with these sessions, questionnaires and opened interviews were applied after testing the digital-version of the prototype.

These instruments were used to collect the participants’ perspectives. Interviews were conducted to assess the use of game elements, as challenges and levels/progression, feedback reaction, etc. Interviews were recorded in audio and subsequently transcribed. They lasted between 12-20 minutes each one.

Data Analysis

In the questionnaires’ analysis, values were assigned to each agreement according to table 2:

Table 2 Value in order of agreement of variables

| Strongly disagree | disagree | neutral | agree | Strongly disagree |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors

Data was tabbed by using simple statistics with the agreement value multiplied by the number of answers received, and also the agreements average.

As to opened interviews, the content analysis technique (BARDIN, 2009) was used in three analytical phases: pre-analysis, material exploration and results treatment and interpretation.

The first phase permitted us to develop the indicators, that is, the theme elements that were frequently repeated over the text that would enable us to discuss the results.

In second stage, with the purpose to understand the meaning ascribed to the data, after proceeding with exploration of the data, it was possible,

to stablish two main classifications: (i) the recording units - sentences related to the perceptions of the students repeated throughout the text, which allows to trace thematic units about the investigation; and (ii) the context units - the text segments used as unit of comprehension to identify the sentences defined as recording units;

To enumerate the recording units. This process was developed by quantifying the presence or absence of units.

To categorize the content, an operation was used to classify the units in classes that bring together data information for each conception and organize the messages (BARDIN, 2009). Category system was defined in the process of treatment of results and interpretations. The study allowed to build sub-categories emerged from the content. The frequency of indicators of the categories was identified.

The Gamified prototype

Type of tool: a storytelling gamified

A narrative named Piazinho em uma Aventura com Seres Fantásticos da Amazônia (Piazinho in an adventure with fantastic beings of the Amazon) was created. It is based on Amazon legends, as MatintaPerera, Fogo do Campo, Mãe D’agua and Boitatá stories. Its main character is named Piazinho, a slender boy whose adventures in the small village Caetés help to show the importance of protecting forest and its flora. The story is divided in 13 main chapters and three bonus scenes.

This narrative plays an important role, since it is the foundation on the resource. From specific chapter seven challenges were created to help students with reading skills, as summarized in table 3:

Table 3 Challenges and their learning goals

| Missions | Learning goals |

|---|---|

| Mission 01 | Recognizing punctuation |

| Mission 02 | Focus, attentions and memory |

| Mission 03 | Decoding and reading comprehension |

| Mission 04 | Word meanings and memory |

| Complementary mission | Lexical awareness |

| Mission 05 | Word contextualization |

| Mission 06 | Identification of main ideas of a text and summarizing |

Source: Elaborated by the authors

In the final of each mission, students get a verbal feedback of the tool in three different ways: verbal incentives, with the purpose of keep them in game, badges and punctuations, representing achievements, and hints, giving them suggestions about a better production.

The framework

The creation of this prototype was inspired by the design framework of Werbach and Hunter (2012) namely in what concerns the implementation of the gamification design. Figure 2 presents our basic framework:

The framework generated a gamified design founded in six actions:

DEFINE learning objectives: provide motivation and engagement and expand student’s awareness about their reading difficulties;

DETERMINE skills, behaviour and knowledge aligned with learning goals;

DESCRIBE learners, which included the type of players they are;

DEVISE activity loops of fun: mobilized the creation of challenges and levels of difficulties;

DON’T FORGET the fun allowed the accomplishment of features as, collections of badges, progress display, which help student to keep engaged; creation of challenges; use of rewards, as points and badges; constant feedback; and inclusion of a learning curve (challenges with different levels of difficult);

DEPLOY the gamified system, which consists in the creation of the structure and content of the gamified storytelling. This whole work allowed the creation of a paper-version prototype and, subsequently, a digital version one.

Gamification design

Table 4 presents design principles of game strategies and game mechanics used in the gamified prototype:

Table 4 Design Principles and game Mechanics

| Game Strategies | Game mechanics applied |

| StorytellingOffer learning through a story | Adventure map |

| Clear goalsEach task in the system present clear purposes. | |

| Time restrictionThere is restrict time to thestudent performs the tasks of his / her responsibility | Timer/pressure |

| Freedom to failThe system allowsthe learner to havemore than one attempt in each mission, giving you freedom to take risks and fail. | |

| Unlocking contentThe systemoffers to the student to access blocked content through actions that grant you permission. | |

| Achievements The system provides visible forms of rewards and status | Badges, points |

| Classification/increasing levelsThe system displays, by means of classification or increasing levels, the progression of the student. | Points, badges |

| Immediate feedback The system gives immediate feedback after each mission fulfilled | Badges, verbal and non-verbal feedback |

| Clear challenges with rising complexity The system offers are objective and clear; and their level of complexity increase according to the learners’progression | Missions |

| Customization of the activities and levels of difficulty adapted to the studentsThe system offers adapted content according to the students’ difficulties and skills | |

| Progress indicator The system offers a visible indicator as long as the student fulfil the missions | Points, collection board |

Source: Elaborated by the authors

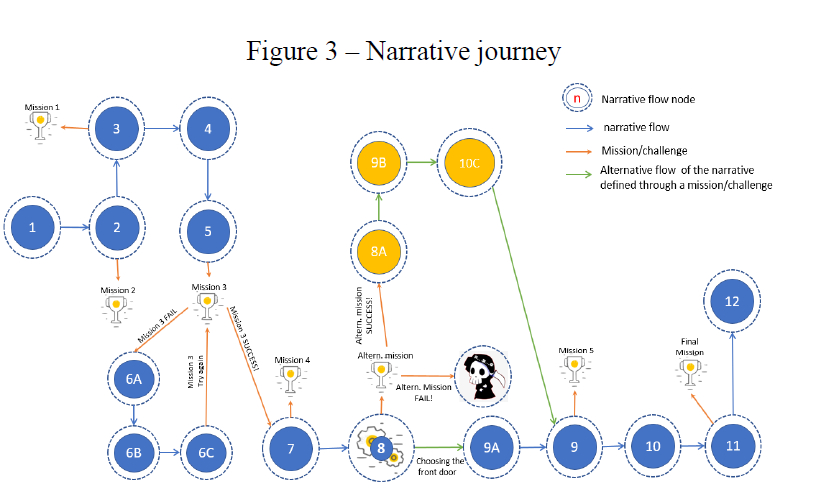

Structure of the Narrative Journey was also produced, as presented in figure 3:

Figure 3 illustrates the structure of the whole gamified tool, in which circles represent the chapters, trophies pose the missions, figure of death symbolizes fail and narrows represent ways. The figure also demonstrates tan alternative path with alternative chapters signalized by the orange circles.

The gamified tool prototypes

Prototyping is consolidating, what involves getting ideas and making them tangible and actionable (SCHEER; NOWESKI; MEINEL, 2012). As result of this designing iterative process, a gamified storytelling tool was produced.

The prototypes were developed using a three-stage approach: consolidation (the creation of the concrete prototype), test (with the purpose to provide feedback, in order to know what work or not and then iterate and redefine the prototype) and evaluation (which provided participants’ assessment of the prototype by the application of interviews). As main results, two subsequent versions were created, as described in the next paragraphs:

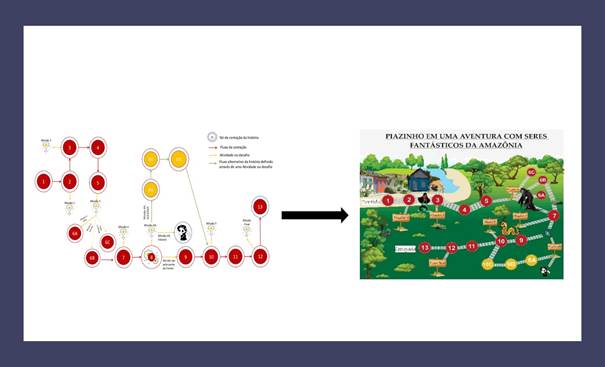

#1. Paper-version prototype

This version provided the elements would be used in the final version as follows:

- The adventure map produced based on the narrative journey planned, as seen in figure 4:

- A main character avatar, the badges, the achievements representation, and the collection map were also produced, as shown in figures 5:

All of these tools were printed in paper in order to test with the same participants. This test was recorded in video, but those findings are not focused in this article. It is important to say that participants contributed with information to the next step of prototyping.

#2 Digital-version prototype

The final prototyping resulted in a digital gamified storytelling, which can be downloaded and locally accessed at a computer. In this version, an adventure map is showed as the menu, a kind of game board from which each chapter of the story is reached, as illustrated in figure 6.

After the creation of the prototype, the testing stage was conducted. Different iterations took place, allowing testing and getting feedback of students and teachers about the prototype in order to redefine it.

Results

This gamified tool was created according to students reading experience and difficulties; hence it is adapted to their skills and reading level. Along testing, they were challenge to face their difficulties when trying to comply with the missions. In order to help them in this goal, teachers assumed the hole of guides by helping in word recognition, text and missions’ comprehension, and mainly giving sustained feedback.

Tests were developed in a reading process split in three steps:

Pre-reading: it was made prediction about theme and content, and activation of previous knowledge from the application of activities with figures and title analysis;

Reading: this part meant the reading of the chapters and accomplishment of all missions;

Post-reading: application of scales and interviews, in order to get participants evaluation.

Tests mainly provided participants evaluation about the contributions of game mechanics to affective and learning domain.

Questionnaires’ results

Questionnaires’ were applied only to the students. Data was tabbed by using simple statistics with the agreement value multiplied by the number of votes received, and also the agreements average.

Table 5 summarizes results of motivation and engagement scale:

Table 5 Paper-version prototyping evaluation- analysis of data and average of motivation and engagement scale according to students’ answers

| Level of agreement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | strongly disagree | disagree | neutral | agree | strongly disagree | average |

| Influenced by the desire to be rewarded | 4 | 5 | 4,5 | |||

| Motivated due to missions and progression | 4 | 5 | 4,5 | |||

| Appreciated the tool due to clear objectives | 8 | 4 | ||||

| Motivated by storytelling | 4 | 5 | 4,5 | |||

| Motivated by time and pression | 8 | |||||

| Appreciated challenges | 10 | 54 | ||||

| Satisfied in learning | 4 | 5 | 4,5 | |||

| Sense of focus and concentration | 4 | 5 | 4,5 | |||

| Feeling of enthusiasm using the gamified tool | 4 | 5 | 4,5 | |||

| Use of skills to do fulfill challenges | 10 | 5 | ||||

| Increased skills | 4 | 5 | 4,5 | |||

| Expectation to learn motivated the student to continue on reading journey | 10 | 5 | ||||

| Persistence on using the tool in order to know how well the learner could do the challenges | 10 | 5 | ||||

| Had fun | 4 | 5 | 4,5 | |||

| Feeling of satisfaction in completing the reading journey | 4 | 5 | 4,5 | |||

Source: Elaborated by the authors

As evidence, motivation and engagement are on average from 4 to 5: these results are perceptibly positive representing students’ agreement with statements about contributions of the gamified storytelling to the affective domain.

Table 6 presents results of students’ perceived learning scale:

Table 6 Paper-version prototyping evaluation - analysis of data and average of perceived learning according to students’ answers

| Level of agreement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | strongly disagree | disagree | neutral | agree | strongly disagree | average |

| Recognizing reading and writing difficulties | 4 | 5 | 4,5 | |||

| Better comprehension of my reading difficulties | 4 | 5 | 4,5 | |||

| Expansion of knowledge about punctuation | 10 | 5 | ||||

| Amelioration of decoding | 10 | 5 | ||||

| Make inferences | 10 | 5 | ||||

| Make word contextualization | 4 | 5 | 4,5 | |||

| Connect parts of the text | 3 | 5 | 4 | |||

| Amelioration of reading comprehension | 4 | 5 | 4,5 | |||

| Amelioration of word comprehension skill | 8 | 4 | ||||

| Use of adjectives in description text | 3 | 4 | 3,5 | |||

| Improvement in focus and concentration | 4 | 5 | 4,5 | |||

| Improvement of skill of summarize texts | 8 | 4 | ||||

Source: Elaborated by the authors

Findings of table 6 reveal an average from 3,5 to 5, demonstrating more agreement with the statements. Student of Case 01 could not give opinion about two statements ‘Connect parts of the text’ and ‘Use of adjectives in description text’; hence she selected the neutral value. Most of values express agreement, that is, a positive evaluation about the contribution of the gamified storytelling to learning.

Open-ended interviews results

This instrument was applied to teachers and students, since it was aimed to know their verbalization about the use of the tool.

The results of the content analysis for students and teachers are presented in tables 7 and 8. Shortened terms are used in tables in order to identify the participant’s frequency of utterances: S1 (student 1), S2 (student 2), T1 (teacher 1) and T2 (teacher 2):

STUDENTS

Table 7 Definition of categories, subcategories and indicators of the students' verbalizations

| Categories | Subcategories | Indices | Presence of indicators | Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contributions to the affective domain | Engagement /motivation | Storytelling | Great | S1: 2 | S2:3 | |

| Missions | The core of fun | S1: 2 | S2:3 | |||

| Motives/engages | S1: 3 | S2:4 | ||||

| Achievement | Stimulation | S1: 3 | S2:2 | |||

| Time | element of frustration | S1: 1 | S2: 2 | |||

| Motivate | S1: 1 | S2: 2 | ||||

| Provoke anxiety | S1: 7 | S2: 2 | ||||

| Progression | Motivate and incentive | S1: 1 | S2: 1 | |||

| Map of adventure | Motives | S1: - | S2: 1 | |||

| Guide in reading | S1: 2 | S2: - | ||||

| Feedback | Motivates | S1: 2 | S2: 1 | |||

| Game experience | Fun and engagement | S1: - | S2: 7 | |||

| Partial | 52/80 | |||||

| Contributions to the cognitive domain | Awareness about reading difficulties | Storytelling | Learning of legends | S1: - | S2: 1 | |

| Comprehension | S1: - | S2: 1 | ||||

| Missions | Punctuation | S1: 1 | S2: 5 | |||

| Comprehension | S1: 1 | S2: 1 | ||||

| Provoke frustration | S1: - | S2: 1 | ||||

| Achievement | Represent learning | S1: - | S2: 1 | |||

| Time | Regulation of learning | S1: - | S2: 1 | |||

| Game experience | Recognition of own difficulties | S1: 5 | S2: 1 | |||

| Reading skill | Map of adventure | Help to link parts | S1: - | S2: 1 | ||

| Feedback | Help to learn | S1: - | S2: 1 | |||

| Game experience | Learn new words | S1: 2 | S2: 1 | |||

| Improve reading | S1: 3 | S2: 1 | ||||

| Partial | 28/80 | |||||

| Total | 80 | |||||

Source: Elaborated by the authors

TEACHERS

Table 8 Definition of categories, subcategories and indicators of the teachers' verbalizations

| Categories | Subcategories | Indices | Presence of indicators | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contributions to the affective domain | Engagement /motivation | Missions | The core of fun | S: - | S2:1 |

| Stimulate interest | S: - | S2:2 | |||

| Accomplishment | S: - | S2:3 | |||

| Comprehension of the game | S: - | S2:2 | |||

| Motivation | S: 3 | S2: - | |||

| Achievement | Motivation | S: 3 | S2:4 | ||

| Stir self-stem | S: - | S2:3 | |||

| Achieved objectives | S: - | S2:2 | |||

| Time | Pression | S1: 1 | S2: 5 | ||

| Essential in game | S1: - | S2: 3 | |||

| Provoke anxiety | S1: - | S2: 4 | |||

| Challenging and exciting | S1: 11 | S2: - | |||

| Progression | Motivate and incentive | S1: 2 | S2: 3 | ||

| Provoke emotions | S1: | S2: 3 | |||

| Challenging | S1: 2 | S2: - | |||

| Motivation of the teacher | S1: 3 | S2: - | |||

| Feedback | Motivation | S1: - | S2: 3 | ||

| reengagement | S1: 8 | S2: - | |||

| (re) orientation | S1: 5 | S2: - | |||

| Teachers’ feedback is complementary | S1: 2 | S2: - | |||

| Partial | 78/115 | ||||

| Contributions to the cognitive domain | Reading skill | Game experience | Learn new words | T1: - | T2: 4 |

| Motivation for reading of legends | T1: 3 | T2: - | |||

| Comprehension | T1: 7 | T2: 7 | |||

| Awareness about reading difficulties | Game experience | No recognition of own difficulties | T1: - | T2: 4 | |

| Recognition and self-evaluation | T1: 9 | T2: - | |||

| Teachers perceivestudents’ difficulties | T1: - | T2: 3 | |||

| Partial | 37/115 | ||||

| Total | 115 | ||||

Source: Elaborated by the authors

Comparing data in table 7 allows verifying that some frequencies detach the type of game design element that seems to contribute more to motivation and engagement: missions, at first, and subsequently storytelling, game experience and time. Regarding the cognitive domain, student 1 reveals more awareness about her difficulties along the use of the prototype than student 2. The latter was able to relate the game elements individually, at least once, with some types of learning.

In table 8, the most prominent findings in teachers’ verbalization demonstrate that these participants perceived more contributions of game mechanics to motivation and engagement than to reading learning.

Discussion and conclusions

Participants were able to assess the contributions of the game mechanics applied to the prototype from their experience to the cognitive and affective domain.

Interpretations and Inferences

Returning to the central questions of this work, it is possible to say that results provided suggestive answers about the application of a lay of game elements/structure to a narrative to the motivation/engagement and learning. Therefore, let is focus on these main domains below.

Contributions to the affective domain

In both scale and opened-interview, students were able to have a sense of enjoyment and motivation by exploring the gamified tool and progressing through chapters representing levels. As widely discussed in literature of gamification in education (ZICHERMMAN; CUNNINGHAN, 2011; LI; GROSSMAN; FITZMAURICE, 2012; DETERDING; DIXON; KHALED; NACKE, 2011), this strategy is used to foster motivation and engagement. Hence, in the context of special education, it was scrutinized how individual game elements impact of students’ motivation and engagement.

Analysis of scales indicates that students perceived this application of gamification as providing strong motivational effects. In the course of the analysis, it was identified that all the game strategies used positively influenced motivation in that particular teaching environment. Thus, the tool seems to have potential to increase affective domain, mainly as for fun and enjoyment.

In general, participants commented that the game and the storytelling were fun and interesting as a reading activity, as presented in table 9:

Table 9 Participants’ verbalization about fun

| P1: The game makes reading more fun; P2: The gamified activity evokes students’ interest in reading and make it funnier. S1: if it was not the game, it was not so fun S2: It was funnier |

Source: Elaborated by the authors

References to fun in these kind of tools reveals the test of the gamified tool as an enjoyable experience, and this exactly what was planned to this tool to be for the participants. According to Zichermman and Cunninghan (2011), fun must be the first the “job #1” when planning an educational resource, in order to provoke this sensation of enjoyment.

As these students have reading impairments, one of the main purposes of this work was add a lay of game mechanics to try to give fun to an academic practice. However, diversion is not the core of this proposal, it is about to make reading more effective. Additionally, Alves (2014) claims that diversion can be associated with engagement and motivation to learning, therefore the use of game design to try to become a reading activity funnier seemed successfully achieved in these gamified prototype’s tests.

Content analysis allowed to comprehend how the gamified tool influenced positively students along the use of the prototype. Some positive words/expressions were highlighted in verbalizations, as shown in figure 7:

These kind of utterances from participants’ evaluation were related to game elements, as missions, achievement, time, progression, map of adventure, feedback and also to the game experience itself. These game mechanics are the tools that yielded “meaningful responses (aesthetics)” (ZICHERMMAN; CUNINGHAN, 2011) from the students. Learners perceived themselves as motivated and engaged in the process, as seen in table 10:

Table 10 Students’ verbalization about game elements

| S1 | S2 |

|---|---|

| ChallengesMissions are great and challenge me | ChallengesMissions and progression make motivated and also engaged |

| ProgressionProgression make us more motivated | FeedbackFeedback incentives and motivates me |

| LevelsLevels stimulate us | Time/PressureTime frustrates me, but makes me excited |

| AchievementsBadges and trophies let us engaged in reading process | AchievementsIt was more enjoyable the whole game experience than to get badges and points |

| FeedbackFeedback stimulated me and made me more motivated to complete the missions |

Source: Elaborated by the authors

Although students with dyslexia have impairments in reading (CARVALHAIS, 2010), learners during this study showed to be perseverant in tasks and made effort to use organizational and memory skills when testing the prototype, which demonstrate their engagement in doing the missions and fulfil the whole narrative journey.

These tools offered by gamification make students “forwards and become more interested and stimulated to learn” (MUNTEAN, 2011) that is, according to students’ perspectives, gamification turned reading more fun and engaging.

Both students declared they were very happy with the narrative itself because it was interesting and about Amazon legends, which helps to conclude that offer a story is one of most important aspects of a game design (DIANA; GOLFETTO; BALDESSAR; SPANHOL, 2014)

Additionally, teachers, as mediators and advisors in testing of the prototype, also made considerations as presented in table 11:

Table 11 Teachers’ verbalization about game elements

Source: Elaborated by the authors

These utterances reveal teachers’ perspectives about two important points:

how the game mechanics harmonically work to motivate learners to focus on the process and progress (MUNTEAN, 2011);

the feeling of failure (MUNTEAN, 2011), that is, to feel free to fail and to be (re) motivated and engaged in the process from the feedback.

Hence, the primary game elements added to the prototype were able to work properly to increase student’s interest in the reading activity. Nonetheless, learner’s perception about the gamification needed to be more researched in order to help us to better understand the of the effect of game structures in motivation and engagement.

b) Contributions to the cognitive domain

When studying gamification, it is more common to research about the effective contributions to the affective domain; nevertheless, this strategy can also help in the process of learning. Therefore, as for the knowledge learning outcomes (SCHMITIZ et al, 2012) results show that students perceived contributions to awareness about reading difficulties, as seen in table 12:

Table 12 Students’ verbalization about learning outcome

| S1 | S2 |

|---|---|

| I notice that I had difficulties with comma, semicolon, with punctuation | I had difficulties with comma, semicolon, with punctuation |

| It helped me with comprehension | I found out new words |

Source: Elaborated by the authors

The teacher who worked directly with student 02 stated that the prototype helped with improvement of vocabulary, comprehension and decoding; nevertheless, it was found that learners’ difficulties were more visible to the teacher than to the students. On the other side, the teacher who guided the student 01 during the session perceived that she was able to talk about her difficulties with comprehension and punctation after accomplished the activity, as seen in table 13.

Table 13 Teachers’ verbalization about learning outcomes

| T1 | T2 |

|---|---|

| She could to talk about her difficulties on punctuation, so I think the resource helped in this sense | The game certainly helped with new vocabulary and words comprehension |

| She better understands that she needs to read slowly in order to understand. | He also understood his problems with some words |

Source: Elaborated by the authors

In sum, questionnaires and opened-interviews results converge to a comprehension about the potential of gamified reading to motivation, enjoyment and engagement, and learning outcomes as well. The participants’ agreeable responses to scales and statements in opened interviews provided little evidence that game mechanics applied to reading can provide better learning to students with dyslexia because of their engagement and interest in the whole process of being challenging and completing missions.

With regard with these two domains, it seems that they are connected, since motivation seems to be vital to the process of learning (SCHMITZ; KLEMKE; SPECHT, 2012), that is, enjoyment and motivation become a ground to learning, specifically in this scenario of special education with students who need to feel more interested and engaged in academic tasks.

Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, the procedures and design framework of a gamified prototype were presented, and the applied game mechanics to a storytelling approach were described. Data was collected from interviews applied to students with dyslexia and their teachers after testing the prototype. The main findings answer our initial questions indicating that the game design elements applied to the prototype contributed to the motivation and engagement of the students and also provided indicators of learning outcomes. On this matter it is important to underline that it was not the purpose of this paper to discuss the learning outcomes or to explore what kind of extrinsic motivation the game mechanics applied to the gamified storytelling resource could be generated.

The main results show that the inclusion of game design elements provide more engagement and motivation, and contribute to students learn as well. Nonetheless, it is not intended to generalize these results, since they represent the perspectives of participants of a specific educational context.

From the findings of testing of the prototype, it can be concluded that missions, feedback, storytelling, game experience and time were the game design elements that seem to contribute more to motivation and engagement. Students perceived themselves as motivated and engaged in the process and showed to be perseverant in tasks and made effort to use organizational and memory skills when testing the prototype, which demonstrate their engagement in doing the missions and fulfil the whole narrative journey. Teachers’ perspectives show that these participants perceived more contributions on motivation and engagement than on reading learning. To offer a story seems to be one of most important dimensions to consider when designing a game and, according to students’ perspectives, the experience of using the prototype turned reading more fun and engaging.

In the future, further work should be done in order to provide more comprehensive data about the use of game mechanics, their function and contributions to cognitive learning. It would be interesting to better understand how the use of game mechanics in reading activities of poor readers could provide learning outcomes. Moreover, it would be important to conduct a study focusing on these students’ emotions when using gamified solutions at school.

Finally, it would be interesting to apply game mechanics of cooperation/collaboration, so that the prototype could storage the points and badges of the students and create a kind of leader board that could be used to verify the contribution of these elements to the motivation and engagement of pupils with dyslexic difficulties.