This research derives from the question that provides the title for the present article: What parts of history do future teachers of early childhood education think that are relevant? Or, to put it in another way, what historical figures, events, and periods do they choose for their historical relevance when determining activities for the initiation of their early age pupils in history? What narratives predominate in their representations of past history? What significance do they give to the relevant events and figures that they have chosen?

Despite the current Spanish education curriculum doesn’t contain any explicit reference to the learning of history in early childhood education, the general interest that historical topics arouse among pupils at this stage of their education is evident, given the knowledge that they obtain outside the classroom of Prehistory, Ancient Egypt, Ancient Rome, and the Middle Ages recently identified in films, on TV, in toys and publications targeted at an audience comprising of pre-readers and beginner readers (KÜBLER; BIETENHADER; PAPPA, 2013). Through these pupils receive a variety of information with which they construct their first notions of eras, events, and historical figures and, so, they contribute to defining children’s preferences in this regard.

This interest advances in parallel with and is fed by the work of numerous early childhood teachers who approach these topics in their classes in accordance with what is designated by the curriculum in the area of Conocimiento del entorno (Knowledge Environment). This states that pupils should be made aware of “different social groups close to their own experience, some of their characteristics, cultural products, values, and ways of life, so as to create attitudes of trust, respect, and appreciation”. Further, in Block 3, Culture and Life in Society points to the “identification of some changes in ways of living and customs with the passage of time” and “acknowledgment of some cultural traits that identify the community and interest in becoming involved in social and cultural activities” (Spanish Early Age Education Curriculum, 2006). The fundamental tool that teachers use for this is project-based in work methodology; examples of it can be found in either the specific bibliography on the topic (MIRALLES; RIVERO, 2012; GIL; RIVERO, 2014) or in the numerous blogs and websites on which teachers post their experiences. Nonetheless, the success of what was originally the outcome of one teacher’s personal and spontaneous initiative in his/her own classroom has in recent times triggered the publication of collections of teaching materials for the three years of the second cycle of early age education (pupils aged 3, 4 and 5 years, respectively) with proposals by a number of publishing companies in the area of Spanish education based on both project-based work methodology and on areas of interest focused on historical topics: Prehistory, the Egyptians, the Greek Olympiads, the Romans, castles, St. James’ Way, the Incas, the Age of the Great Discoveries, pirates, native North Americans, and the Industrial Revolution. For example, Anaya has brought out its Por Proyectos (By Project) collection in 2010; Santillana its ¡Cuánto sabemos! (What a Lot We Know!) collection in 2011 along with some other titles specifically written for each of the school years and “cycle projects” equally designed for all three; and Edelvives its Dimensión Nubaris (The Nubaris Dimension) (2012) and Proyecto Sirabún (The Sirabun Project) (2016).

As a result, given that there are no explicit regulations in the curriculum regarding the teaching of history in early childhood education, the teachers themselves are the best positioned to exploit and orientate the influence of non formal education and there is no doubt that they are also the people who have shaped the above-mentioned products brought out by the publishing houses. It is clear that historical relevance and significance are one of the meta-concepts or part of the most important strategic content of historical thinking in the training of second cycle early age education teachers (of pupils aged 3 to 5 years) as this will shape the content that they might teach to their future pupils.

THEORETICAL GROUNDING

Historical relevance is one of the six meta-concepts defined by Seixas & Morton (2013) as the fundamental principles for the learning of historical thinking that teachers should take into account along with: sources; permanence and change; cause and consequence; historical perspectives; and the ethical dimension. It is our opinion that due to the very nature of History they are all subordinated to an overarching concept, historical time, which has its own dimensions (sequence, duration, simultaneity, rhythm, etc.). In addition, the meta-concept related to the ethical dimension should perhaps be related more to the creation of historical awareness, in the line of addressing difficult or conflictive topics in the classroom, and not expressly considered as a structuring concept of historical thinking; this is an idea that occurred to us on the basis of recent contributions made by Seixas (2017) himself.

Relevance and historical significance imply that a critical perspective must be employed when giving thought to what should be remembered and why (SEIXAS; PECK, 2004), bearing in mind factors such as the impact of change, i.e., whether a large number of people were affected, duration of the consequences and whether these continue to be felt, the importance given to it by the people at the time and its “enlightening effect”, i.e., what thinking about this past event or aspect of the past reveals about our present (LÉVESQUE, 2008; SEIXAS; MORTON, 2013). It entails, therefore, thinking about what the content of history should be as a school subject and, consequently, about the end goal of the history teaching. It also needs to be taken into account that, unlike other structuring concepts, relevance is shaped by contextual aspects, in particular, those that are identifying and ethic traits. These are issues that will be analyzed in the present research through the study of narratives.

Various studies have approached the perception of historical relevance held by high school and pre-university pupils in different countries (CERCADILLO, 2000, 2006; PHILLIPS, 2002; BARTON; LEVSTIK, 2004; LÉVESQUE, 2005) and also by Spanish university students (SÁIZ; LÓPEZ FACAL, 2015; EGEA; ARIAS, 2018). The present research is linked to this. On the one hand, its novelty lies in its inclusion of the analysis of narratives in the study of relevance, as was done by Sáiz & López Facal (2015) and, on the other, its focus on university students studying for their degree in early childhood education, who construct their historical narratives as future teachers of early age pupils, i.e., boys and girls of between 3 and 5 years of age whose curriculum does not specifically provide for historical content. Thus, the aim is to determine which historical aspects are relevant in the context of their professional career, given the total freedom that the early childhood education curriculum gives them for the choice of historical topics, figures, and periods, etc. This feature is extremely important for the research, as it is a significant factor in the consideration of the history that is to be conveyed in young children’s classrooms, which, in our opinion, will to a great extent depend on the historical relevance that the early age education teacher gives to any particular historical element. As it has been stated, the Spanish education curriculum provides for relevant historical figures and events to be addressed during the compulsory (Primary and Secondary) and post-compulsory education stages (Baccalaureate or pre-university), but does not envisage anything in this respect for early age education. The historical relevance that trainee teachers of early age education attribute to the different historical figures, events and phenomena that they address will determine the first encounter of their future 3 to 5-year-old pupils in the school setting, and their inclusion as significant historical content in their early childhood classes will enable them to begin to construct the different competencies of historical thinking or meta-concepts required for understanding the past (CERCADILLO, 2000; WINEBURG, 2001; LÉVESQUE, 2008; VANSLEDRIGHT, 2011, 2014).

METHODOLOGY

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The overarching question posed by the present research is: what aspects of history do early education trainee teachers consider to be important for teaching to their future early age pupils? We, therefore, propose research into historical relevance, although it is also broadened to include details about the actual historical significance of events, figures and phenomena regarded as relevant, and thought is given to the model of the narrative and the identities reflected in the texts prepared by the trainee teachers.

This entails the formulation of the following specific questions:

What substantive content do they present as relevant and why?

What is the dominant narrative typology?

This is an empirical, not experimental, research that systematically seeks to reveal reality and to this end uses instruments that provide qualitative information through narrative discourse. As in the case of other recent studies on historical thinking (BARCA; SCHMIDT, 2013; EGEA; ARIAS, 2015; SÁIZ; LÓPEZ FACAL, 2015), the present study uses open coding based on grounded theory in that it prioritizes data over assumed prior theories (CORBIN; STRAUSS, 2008; FLICK, 2012). It considers narrative typology to be a fundamental analytical concept that enriches data interpretation (GLASER; STRAUSS, 1967,1 apud FLICK, 2012) which, in the case of traditional typology, cannot be disassociated from reflection on identities. However, the exercise’s format as a historical story does not enable identity to be analyzed by applying the study to the subject of the narrative, as the first person is frequently used as a narrative resource, and this criterion could only be applied to the justifications presented voluntarily by some of the trainee teachers.

CONTEXT AND PARTICIPANTS

660 narratives have been analyzed in the form of a “historical story”. These were prepared by twelve groups of trainee teachers at the University of Zaragoza on the Didactics of Social Sciences course included in the degree in Early Age Teaching at the Education Faculty (Zaragoza campus) during the 2012/13 and 2013/14 academic years, and at the Faculty of Human Sciences and Education (Huesca campus) during the 2014/15, 2015/16, 2016/17 and 2017/18 academic years, i.e., since the introduction of this course as part of the University of Zaragoza degree. Convenience sampling was used rather than probability sampling as the authors of the research selected the groups to which they themselves taught the subject in question.

Participants are aged from 20 and to 51years, although 20 year-olds predominate at 30.2%; this is the age that corresponds to the trainee teachers in the academic year that have not completed any other previous studies. However, 90.2% of the subjects are between 20 and 25. This percentage includes students who have come to this degree directly after passing their university access exams and students who have studied other subjects previously, whether a cycle of vocational training -generally early age teaching- or part of the Degree in Early Age Teaching. Student record enrolment data show that a large number of students have come from cycles of vocational training: 42.5% of students enrolled in all six academic years analyzed. Participants in this research are mainly women, specifically 628 (95.2%) compared to only 32 men (4.8%).

TABLE 1 NO. OF NARRATIVES BY ACADEMIC YEAR

| ACADEMIC YEAR | NO. OF NARRATIVES (N=660) |

| 2012/2013 | 104 |

| 2013/2014 | 129 |

| 2014/2015 | 114 |

| 2015/2016 | 101 |

| 2016/2017 | 103 |

| 2017/2018 | 109 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

The “historical story” is a compulsory individual assessable activity. It is included in the practical part of the Didactics of Social Sciences subject taught during the first four-month term (September-February) in the third year of the degree course in Early Childhood Education during which students are simultaneously doing practical training in schools. The subject is compulsory and the only class related to historical content studied on the Early Childhood Education university degree. Trainee teachers must be able to use the story to present a certain item of historical interest in their in-school practical training or at a later date with their future early childhood pupils. This could be a historical figure, an event, an era, an invention, a discovery, a legend or a tradition, and can be done both in a physical format -as a kind of craft activity- and in an electronic format - in a regular or audiovisual presentation. This is a formula that has proven to be very positive for the teaching of history in early age education (MIRALLES; RIVERO, 2012; SKJÆVELAND, 2017). In this particular case, the choice of topic is left up to each of the students and this has been seen to be a great incentive that also gives very satisfactory results. The choice will therefore depend on the importance that individuals give to a topic depending on the interest and utility that, in their opinion, it will have for working with real early age pupils, e.g., their own future pupils, as during the period of practical training or at the end of the Didactics of Social Sciences course, craftwork is photographed by trainees and they can take it away to use in their future work as teachers. All this underscores the interest of the exercise for defining the degree of historical relevance of the topics selected by the students.

ANALYTICAL INSTRUMENTS AND CATEGORIZATION

As indicated, the main source of information is the 660 individually constructed narratives that reflect the thinking of 660 students of early age education over six consecutive academic years. These narratives have been numbered consecutively. With the aim of obtaining further information that might allow the interpretation of the narratives with a better triangulation of perspectives (FLICK, 1992, 2012), participants were asked to voluntarily present a short text indicating the reasons why they chose their topics, i.e., their personal feelings about the relevance of the historical event, aspect or figure and why they thought it should be used as a part of early age pupils’ learning. 237 students presented brief justifications and their answers were also coded consecutively.

The narratives and their justifications were analyzed from a variety of complementary perspectives with the aim of finding an answer to the study’s fundamental issue: what historical aspects are considered by future early childhood education teachers to be the most relevant?

The analyzed dimensions were: historical period; historical figures; episodes-events, subject matter and narrative typology. They were processed using a discourse analysis qualitative methodology with prime importance is given to coding the texts of the narratives and justifications and labeling them according to the specific dimensions. In line with the previously mentioned grounded theory, an emerging categories model was applied to the first four dimensions so as not to impose any limitations on their interpretation. As suggested by Gibbs (2012), coding by topic was applied to each of the narratives and justifications and also to each of the representative paragraphs in them that enabled specific data to be pulled up for analysis. The total number of narrations that addressed each particular event or historical figure as its principal characteristic was recorded in line with the Egea & Arias (2018) recommendation and on the understanding that qualitative research and data quantification are not mutually incompatible and can be combined (FLICK, 2012). The Plá (2005) discourse analysis model was followed for the narrative identity dimension. The use of a third person or first person singular or plural narrator was analyzed as a component of identification with the reference community, whether this was local/regional or national, and of the Rüsen (2005; 2010) narrative typologies, which distinguishes between traditional, exemplary, critical and genealogical narratives. This is in line with other recent international research studies (BARCA, 2010; LEE, 2012; MAGALHÃES, 2012; BARCA; SCHMIDT, 2013; SÁIZ; LÓPEZ FACAL, 2015).

The first four dimensions are related to historical thinking first-order concepts. We, therefore, accept that historical training should include an overarching integrative process in the teaching of knowledge or first-order concepts and competencies or meta-concepts in the line set out by Lee (2005, 2012), as both are constituent parts of historical thinking (WINEBURG, 2001; LÉVESQUE, 2008; VANSLEDRIGHT, 2011, 2014).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

SUBSTANTIVE CONTENT

We have analyzed the historical periods, the historical or mythological-legendary figures that are the principal characters in them, the narrated historical events and the general topics addressed in the narratives, to answer the question “What substantive content is presented as relevant and why?”

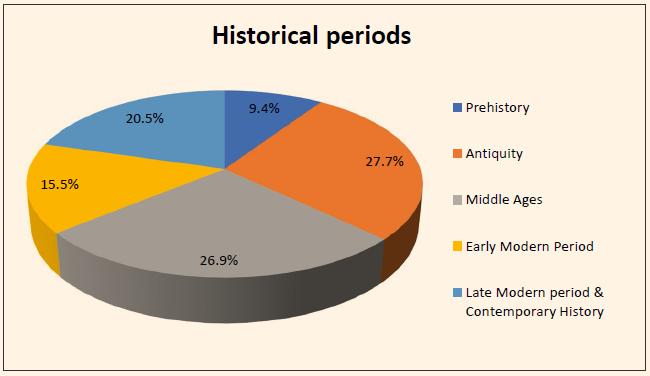

Of the 660 narratives, 118 cannot be assigned to a specific period but present: 1) different historical moments in the same geographic area; 2) a location’s different cultural assets; or 3) related historical figures (scientists, musicians, painters) from different periods of history. 542 stories focus on specific moments in history and these are distributed by historical period in the following table and diagram:

TABLE 2 NARRATIVES DISTRIBUTED BY HISTORICAL PERIOD

| HISTORICAL PERIOD | NO. OF NARRATIVES (N=542) | PERCENTAGE (%) |

| Prehistory | 51 | 9.4 |

| Antiquity | 150 | 27.7 |

| Middle Ages | 146 | 26.9 |

| Modern Age | 84 | 15.5 |

| Contemporary Age | 111 | 20.5 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

All historical periods are represented. Prehistory is addressed from the perspective of daily life and focuses primarily on the Paleolithic era. Only one story focuses on the Neolithic period (highlighting the beginnings of agriculture, ceramics and sedentary life in settlements) and also, on a single occasion, the Metal Age. As in the study by Egea & Arias (2018), a range of technological and cultural advances are highlighted (discovery and control of fire, the carving of stone tools, cave paintings), as are a number of issues related to daily life (cave dwelling, hunting, and gathering).

For Antiquity, mention is basically made of Ancient Egypt due to the value placed on the pyramids, mummies, and hieroglyphs as essential cultural assets that can instill fascination in early age pupils. Other narrations address daily life in Greece and, above all, in Roman towns - both in general terms, such as Rome with its enormous buildings and public spectacles, or Roman towns in the pupils’ local area, such as Caesaraugusta (Zaragoza) - and also the Olympic Games and a large number of mythological tales or stories relating to Ancient Christian tradition that trainees think are relevant for their links to local or regional festive events.

However, the narratives dealing with the Middle Ages generate very different results from those obtained by Egea & Arias due to participants’ different identity contexts. For early age education trainee teachers at the University of Murcia, medieval times are understood as a parenthesis in the unfolding of history with little historical relevance and characterized by darkness and oppression (EGEA; ARIAS, 2018). However, for trainee early childhood education teachers from the University of Zaragoza, the Medieval period is a reference point for the understanding of both tangible (castles, churches) and intangible (local festivals, toponyms) heritage (especially during the rise and expansion of the Kingdom of Aragon, a historical antecedent of the Autonomous Community (Region) in which the university is located.)

Daily life, with a focus on castles as a representative heritage asset, dominates narratives about the Middle Ages. On some occasions a castle that is representative of the local area is chosen as the focus for the narration -the Castle of Loarre, for instance, the best preserved Roman castle in Europe, or the Castle of Monzon, with links to the Order of the Templars and James I of Aragon’s early childhood, but also the Moorish-Andalusian Castle of La Aljafería, which provided the backdrop for Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Il Trovatore. Many of the narratives for this period also include legends related to local and regional heritage: one that stands out is the legend of St. George, who is the patron saint of Aragon, where the study was conducted. Despite the fact that they do not represent historical events, these legends have been included in the present study because of their influence on the construction of narratives related to national, local and regional identities, as is acknowledged by other researchers (LÓPEZ RODRÍGUEZ, 2015).

Most Modern Era stories are linked to the Discovery of America and this, as will be seen below, is by far the historical event most frequently considered relevant.

A wider range of topics are addressed in contemporary history, with wars and social conflicts represented. The Spanish War of Independence to repel the Napoleonic invasion, in which the siege of the city of Zaragoza -known locally as “Los Sitios”- was a major episode, stands out. However, narrations referring to the contemporary period focus above all else on progress in science and technology, with an analysis of the changes that discoveries and inventions entailed for daily life, and the space race

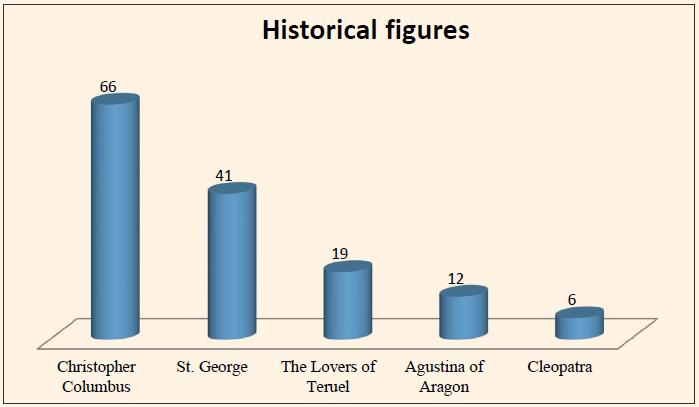

A large number of the narratives focus on one or several historical figures that the students regard as relevant. Others, however, address content related to daily life, with universal cultures or world cultures in which no historical figure stands out. This is the case of stories focused on discoveries and inventions in Prehistory and Antiquity, such as fire, agriculture, and writing. 186 exercises do not allude to any legendary or historical figure. Those that do mention a figure, refer most frequently to Columbus (66 stories) and St. George (41 stories), followed by the Lovers of Teruel (19 stories), Agustina of Aragon (12 stories) and Cleopatra (6 stories). Because of the Discovery of America, Columbus is treated as a relevant historical figure on the international scale and will be analyzed in greater detail below. St. George is chosen as he is the Patron Saint of the Aragon region, but as a historical figure, he is always dealt with through the legend of the killing of the dragon, which is not linked at all with his historical actions. Similarly, no mention is given to the tradition of his miraculous appearances during the Medieval period in the context of the expansion of Aragon over the Moorish lands in the south of Spain that resulted in his being proclaimed Patron Saint of Aragon. It is the legend of the dragon that is remembered on the Day of St. George, which is a regional holiday in the Aragon Autonomous Community, and this interest in explaining the historical roots of local festivities is what justifies his presence among the most relevant historical-legendary figures. The same thing happens with Diego and Isabel, the Lovers of Teruel, historical figures in an extremely well-known medieval legend in the same region and whose feast day is celebrated with a historical reenactment declared an event of tourist interest. On the contrary, Agustina of Aragon is a local heroine involved in the Siege of Zaragoza during the War of Independence against Napoleon’s troops and is a well-known and deep-rooted figure in local historical memory.

Despite there are three women among the six most frequently chosen historical figures, in general terms there are very few women compared to men -even though most of the students taking part in the study are female. Women can be found in a wide range of contexts, however, from heroines in the War of Independence (Agustina of Aragon and the Countess of Bureta), to queens (Cleopatra, Petronila and Berta of Aragon, Isabel the Catholic, and Letizia) to representatives from the fields of science (Marie Curie), art (Frida Khalo), religion (Sister Maria Rafols) and the struggle for women’s rights (Clara Campoamor and Simone de Beauvoir).The increase in gender studies seen in Spanish historiography in recent times may lead to a change in the situation.

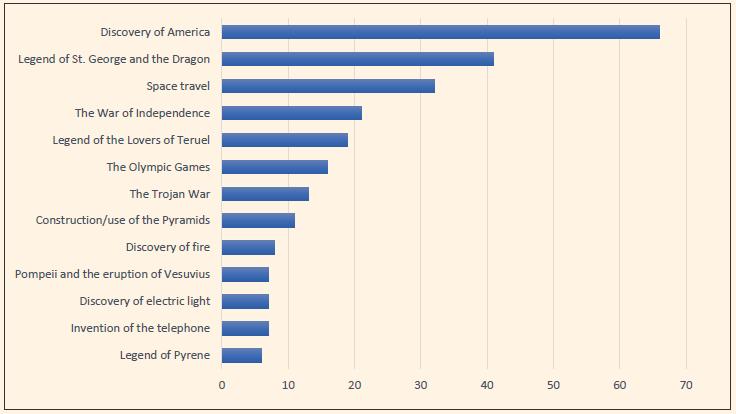

With regard to the most frequently chosen historical events, the Discovery of America stands out above all others (with 10% of the narratives).This event is always linked to the figure of Columbus, but only on very few occasions to the Catholic Monarchs, who appear as secondary historical figures and are referred to with a wide variety of names.

Justifications given for narratives about the Discovery of America often highlight its universal importance:

“This event is relevant for the history of humanity. It greatly changed the history of the world. Christopher Columbus’ reaching America is considered to be one of the most important events in history for the consequences it had” (j059).

Its relevance is explained in all cases by the consequences that it has had for basic aspects of daily life to the present day, with the emphasis always placed on food:

“You will find it strange to think that we eat many of the foods that we have today thanks to this event, including potatoes, for example” (j023); “Those unknown people gave them their best products and that’s how staples like potatoes, tobacco, corn, cotton pineapples, peanuts, peppers, and pumpkins were discovered. They learned how to grow those foods in those lands and brought them back to their own country” (j103); “Many of the foods we eat were discovered, and this gave new knowledge to western culture” (j201).

A second aspect that explains its relevance in the students’ eyes is its value for geographic and scientific progress, as for Europeans it represented the discovery of a new continent, which the students see as relevant both at the time of the event, subsequently and right up to the present day. Besides it, several students refer to the possibility of including an explanation about continents based on the Discovery of America and this first contact with American geography is, precisely, the most appealing part for its inclusion in class as a historical topic:

“Another objective that we can propose is that they learn geography as Columbus sailed to many places” (j075); “I thought it would be a good topic to address right from the start because the children learned that continents and other countries in the world were discovered only very slowly” (j189); “I also think it’s important for children’s knowledge of what the planet is like” (j220).

The meeting of cultures is another element to which future teachers give great importance. The revelatory effect that involves thinking about how people from different cultures behave is regarded as particularly important for teaching pupils in an intercultural context, although it is never focused on from the critical perspective that was to derive from colonization in the immediate aftermath of discovery. This is a topic that is never included as the story always ends with the reaching of America and, on some occasions, the celebrations on the sailors’ return. The colonizing process and its consequences are not included in any of the stories about the Discovery of America or in any of the narratives collected:

“We can use Columbus’ meetings with the natives and his dealings with them to instill values in children, such as respect for others, solidarity, and so on” (j065); “People need to be aware that this event represented a great social change, because we learned about new cultures and this led to greater tolerance toward unknown peoples, and also their values, customs and ways of life” (j084); “This story can be used to encourage tolerance toward people from other cultures” (j139); “This part of history enables children to be mindful of the fact that they can live together with different cultures and that you don’t need to look down on or prejudge other people before you get to know them just because they’re different” (j149).

There are, moreover, two justifications that refer to the multicultural composition of current society in Spain, where there is a large presence of people from all over Latin America, and give even greater relevance to this historical event:

“This is a topic that can be very interesting for our pupils because there are a lot of immigrants in our classrooms these days and there might be a classmate from America or who has got some relatives there” (j015); “Of all the events I could have chosen, with some that are as important or even more important than this one, I thought it was an attractive idea to introduce pupils to this part of history as, during my teaching practice, a little girl told us that her neighbor had been born in ‘the center of America’ and that she wanted to go there because that’s where chocolate comes from and she really loves chocolate” (j072).

However, there are other issues that affect the choice of historical episode apart from its relevance and its emotional link. One of these is the value of adventure, the emotion that can spring from being part of a feat or a journey, or a fact-finding and discovery process, by means of a story. This also influenced the choice of the Discovery of America on at least two occasions:

“Since early childhood pupils really like adventure stories, and stories about sailors and the like, I think this will help them to discover part of history in an entertaining and motivating way” (j067); “The life of this historical figures parks children’s imagination and their spirit of adventure”. (j128)

Only one student’s justification alludes to his/her own school memories and, so, to the effect that the Spanish Primary and Secondary Education curriculum had when choosing a historical event without including any other thoughts about the relevance of the event itself: “The history of how America was discovered is something they teach us in primary school and high school” (j199). Nonetheless, even though only a single person specified this in his/her justification, school knowledge might have had an influence on the choice of topic for the construction of these historical stories, as the influence of school thinking on the perception of historical relevance has been highlighted in previous research (PLÁ, 2005).

The set of historical events most frequently highlighted only partially coincides with those named by the students who took part in the study at the University of Murcia (EGEA; ARIAS, 2018). In this case, the historical events considered to be most relevant were World War II, the Discovery of America, the Neolithic revolution, control over fire, the French Revolution, the Spanish Civil War and the invention of metallurgy. All these are included in the 660 works at the University of Zaragoza, and only 1% more in the cases of the Discovery of America and the control of fire. It should be highlighted that studies’ narrations of the Discovery are usually quite simple and do not include critical thinking in any shape or form but, rather, on many occasions are more in the line of a naive tale of adventure, as is also the case in the narrations written by the University of Murcia students (EGEA; ARIAS, 2018).

As they are “sensitive” phenomena to be addressed in classrooms, wars are chosen with less frequency as these historical narratives are constructed for presentation to pupils of between 3 and 5 years of age. However, both the Second World War and the Spanish Civil War - which were among the six most relevant events chosen in the Egea & Arias (2018) study - do receive implicit representation, as one work addresses the Holocaust and another the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, whilst the Spanish Civil War is addressed on four occasions through references to local episodes. Despite also being a military conflict, the War of Independence is nonetheless seen as a relevant event on several occasions as it is more distant in time. It is also an identity element in the region’s historical memory due to popular activity in the Siege of Zaragoza, with historical figures like Agustina of Aragon represented. It seems that the remoteness of the war and its identity value mean it is not a “sensitive” topic.

Of all the chosen historical events, only a few can be classed as controversial. The fact that they are directed at 3 to 5-year-old children is doubtlessly one factor that determines this, but there are some exceptions which, precisely, highlight the need to face up from an early age some realities that may not have a “happy ending” (HARNETT, 2007). In recent decades in the French context, historical relevance has been given to subjects that are far removed from the 19th-century romanticization of the national identity, with sensitive topics such as the Holocaust, the Armenian genocide and immigration brought into the classroom (FALAIZE, 2010). Despite the young age of the children they are presented to, several participants have opted for topics such as the Holocaust (by adapting the book by Anne Frank), the Berlin Wall, the fight for Civil Rights in the USA, the Spanish Civil War (regarding the Battle of Bielsa) and the Spanish rural exodus, which is an example of the growing awareness that these topics raise among trainee teachers.

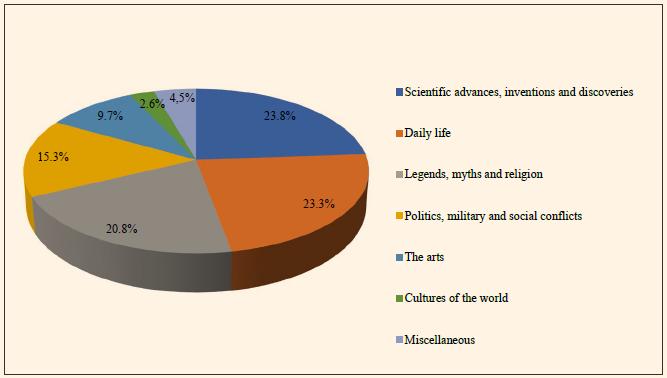

TABLE 3 TOPICS IN WHICH RELEVANT EVENTS ARE INCLUDED

| CORE TOPICS | NO. OF WORKS (N=660) | PERCENTAGE (%) |

| Scientific advances, inventions and discoveries | 157 | 23.8 |

| Daily life | 154 | 23.3 |

| Legends-myths-religion | 137 | 20.8 |

| Politics-military and social conflicts | 101 | 15.3 |

| The arts (painting, music, literature…) | 64 | 9.7 |

| Cultures of the world | 17 | 2.6 |

| Miscellaneous | 30 | 4.5 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

If we analyze the subject matter of the works we observe that most are focused on scientific advances, inventions, and discoveries, which shows a technical progress-based narrative. Fascination with the work of inventors and researchers vies with an interest in highlighting the change that these inventions brought about in the lives of a large number of people. The irrelevance lies both in the longevity of their consequences and in the depth of change - even for the people at the time - and acknowledgment of this change is particularly emphasized. This denotes genetical narrations according to the Rüsen categories.

Another point of great interest is daily life and focuses on the explanation of what is usually called “cultural universals”, including dwellings, clothes, jobs, etc. Seixas & Morton (2013) stated the need to link men’s and women’s daily lives to great historical processes -an issue that ties in with the objectives of social history (GÓMEZ; MIRALLES, 2013). The first step for this consists of introducing daily life as subject matter in class, an issue with which the participants in this study are clearly in favor, as is proven by the high number of narratives that focus on this precise topic. The consolidation of social history has been a key factor for the acceptance of the historical relevance of cultural universals that are embodied in the daily life of the different civilizations, and for their growing presence in education programs (MIRALLES; MOLINA; ORTUÑO, 2011). According to Brophy & Alleman (2006), these cultural universals include all the issues that are related to family, dwellings, food, clothes, communication systems, economic exchange, religion and professions, and these are aspects that the participants in this study introduce into their narratives on daily life. Contrasting these past modes of life with the present is an added value that frequently figures in the justifications - “They will be able to see how life has changed by comparing the way their grandparents used to live and the way they live now” (j202) - with the aim of initiating the early childhood pupils, the recipients of the narrations, in reflection on change and permanence.

Myths, legends and Christian traditions also stand out and are mostly linked to the local environment in order to explain toponyms and religious festivals. The exception is Greco-Roman mythology, which is chosen for its interest in understanding European culture and heritage. So, the relevance given to legends and myths is primarily in relation to its continuity in both tangible and intangible heritage, with basically local religious celebrations included in this. This subject matter includes both exemplary and traditional narratives according to the Rüsen classification.

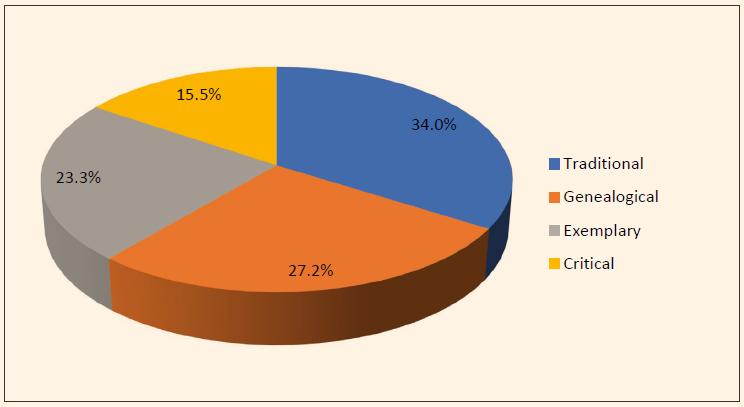

PREDOMINANT NARRATIVE TYPE

The same historical event is presented with one type of narrative or another depending on the perspective taken by the student who has written the story. It is not the event itself that determines the type of narrative, but the author’s historical awareness and the goal for which s/he constructs the text, which is not unequivocally evident in all cases. Notwithstanding, the justifications provided by the students of early childhood education comment on the reasons why they consider their chosen topics historically relevant that mean that they will be addressed in the class, which helps to confirm each story’s type of narrative. However, 36 stories have been excluded from this classification because they are merely descriptive and the justification provides no complementary data that enables them to be conclusively classified in the categories defined by Rüsen.

TABLE 4 STORIES BY NARRATIVE TYPOLOGY

| TYPOLOGY | NO. OF WORKS (N=624) | PERCENTAGE (%) |

| Traditional | 212 | 34.0 |

| Exemplary | 145 | 23.3 |

| Critical | 97 | 15.5 |

| Genetic or genealogical | 170 | 27.2 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Traditional historical narrative is in the majority (34%). It addresses the episodes that encourage unity and social cohesion; it highlights common origins and justifies a community’s traditions and customs: continuity is a key factor. Medieval legends, the Kings and Queens of Aragon, episodes linked to the War of Independence, Christian traditions linked to local and regional festivals, etc., are prime examples of this type of narrative. Many of the legends linked to local festivals also include an exemplary type of narrative, but at the current time future teachers include them for their value as a cohesive element for the community, to provide early childhood pupils with data about patterns in their localities more than for the value that they represent, given that the action is too remote in time and in a context that is hard for such young children to comprehend. This type of narrative generally coincides with justifications in which the narrative subject is shown as implicit in the first person plural: 97.3% of the justifications associated with traditional narratives include expressions such as “our history”, “our heritage”, “our community”, etc., and only a small number refers to the same realities with expressions like “their community” or “their locality”. Justifications of the following type are most commonly found:

“It’s an entertaining way of telling them about something that has happened in our culture and, of course, getting them actively and constructively involved in it [...] It’s the perfect way to draw them into our history and get them interested in learning more”. (j072)

It is also necessary to highlight the almost absolute absence of identities that refers to the nation as a whole. The local and regional identity predominate due to the importance that the early childhood education curriculum gives to understanding the children’s milieu, which is also the reason why importance is given to medieval references given the context in which the study is conducted. Even in topics in which we expected to find more references to national identity, such as the Discovery of America, only one justification stresses Spain’s involvement as an identity reference of the historical narration when it did not actually exist as a political reality at the time:

“The story ensures that the children know that America was discovered thanks to help and aid given by the then Queen of Spain and the inclusion of a great number of Spanish seamen on the voyage who believed in Christopher Columbus and wanted to help him on his long journey”. (j148)

Most of the students prefer a more Universalist approach:

“I chose the Discovery of America as my historical event to tell the children because I think it’s extremely important to introduce them to world history” (j048). “I did the story about the Discovery of America because I think it’s one of the most important events in the history of humanity, and I think that children should learn about the event and be aware of it for the rest of their lives”. (j160)

This is again justified by the research’s regional context as the historical reference point for the current Autonomous Community is the Kingdom of Aragon, which belonged to the crown of Fernando the Catholic and not the lands governed by Isabel the Catholic, an aspect that is taken into consideration in regional identity and which leads to the Discovery of America being something that is more identified with the region of Castile than Aragon. It should be borne in mind by way of example that in the episode that the children’s series Lunnis de Leyenda (“Legendary Lunnis” is a TV program produced and broadcast by Spanish public television (2016-2017) that narrates historical events and legends for a child audience) devotes to the Discovery of America, every time that Christopher Columbus appears before the Catholic Monarchs he addresses Queen Isabel while King Fernando is completely unaware of what is going on as he is listening to music through his earphones: the feeling of identity linked to the Discovery seems to be so unconnected to the King of Aragon as to the students who are the object of this present analysis some five centuries on.

Be that as it may, as in the case of exemplary narrative, stories linked to this type of narrative usually contain stereotypes and are not in any way a critical assimilation of identity history, which generally refers to the regional or local area and is linked to a romantic vision of historiography; in this aspect they are no different from the studies of narratives of other university students written in different contexts (ARIAS; SÁNCHEZ; MARTÍNEZ, 2013; EGEA; ARIAS, 2015; LÓPEZ RODRÍGUEZ; CARRETERO; RODRÍGUEZ-MONEO, 2015).

The genealogical (or genetical) type of narrative emphasizes change: transformation is portrayed as a fundamental factor, a story focused on progress would be “a good model of genetic thinking as it assumes that past experiences are susceptible of being changed and that this transformation changes things for the better in the future” (CATAÑO, 2011, p. 236). Historical stories with links to scientific advances, discoveries and the space race, and many of those linked to daily life in the past -which in their justifications state the possibility of comparing earlier lifestyles with today’s and, consequently, emphasize change- are good examples of this also very frequent narrative model (27.2%).

The exemplary type of historical narrative emphasizes behaviors whose application in the present would be considered positive. This narrative also appears frequently (23.3%) in the chosen historical episodes and figures due to the importance that participants in the research, as future teachers, give to values education. In fact, they usually emphasize the value that thinking about the actions of these historical figures has for the present time in their justifications. In this type of narratives, we find mythological stories from the Greco-Roman world such as the Wooden Horse of Troy, which is used as an example of cunning, and narrations that emphasize the defense of rights, such as those devoted to Clara Campoamor, Martin Luther King, and Nelson Mandela.

Even the Discovery of America is presented from this exemplary perspective on as many as 23 occasions, as it is made clear in several of the justifications:

“What this story intends to do is to show that by studying hard and with belief in yourself, you can make your dreams come true however difficult they may seem” (j073); “Apart from telling the story of what actually happened, I will endeavor to get the children to realize that, despite what everyone else thought at the time, Christopher Columbus thought that the Earth was round. And as he believed in that, he didn’t give up and did everything he could to prove it. The moral that I want the children to see is that, if you want something, you have to fight for it, even when you don’t count on everybody’s support” (j179).

Lastly, it should be noted that if the past is no longer a source of guidance for the present in critical historical narrative, and there is a break between the past that presents the narrative and the present time, many narratives created by the students of early childhood education do include a glimpse of the past because of pure fascination with certain cultures and constructions, with what is exotic and different, such as Ancient Egypt, Ancient China, and the Vikings.

CONCLUSIONS

The Discovery of America is by far the most relevant historical event for trainee early childhood education teachers. This is not only due to their thinking that it is relevant in all aspects, both in depth and in the permanence of its consequences even in details of daily life today -food, for example- but also because of the revelatory nature that thinking about it provides even for very young children. This is shown in the fact that this same event takes on different narrative typologies, not only traditional, but also genealogical, focusing the interest on the advancement of knowledge that came from it, and exemplary, which in this case stresses tenacity. And all this despite the narrations presented generally being simple, not subject to the critical judgment of its consequences. In addition, this single historical event gives rise to a broad range of narratives; the more narratives that a single event can achieve, the greater the frequency with which it will be chosen as a relevant event, as it is considered to be relevant from many different perspectives and its teaching is judged to be appropriate for a range of purposes.

The acknowledgment of the great relevance of all the events and historical figures that are the basis for the creation of local or regional identity is also evident due to the value that the students of early childhood education give to history as a tool for interpreting the milieu of their future pupils on the sociocultural level. This is why the events appear in traditional narratives and also explains, on the one hand, the greater prominence of the Middle Ages and the War of Independence compared to studies in other parts of Spain and, on the other hand, the less relevance that is generally given to historical events that are traditionally linked with Spanish identity. This confirms that the historical relevance given to an event or historical figure to a great extent depends on the context of those who perceive this relevance, with differences even observed among peer students from the same country, depending on the region that they are located in.

It is important to highlight the relevance given to issues related to daily life, with its cultural universals and the technological advances that bring changes to it. The idea of progress through contrasting past and present lifestyles is one of the core threads in the narratives and generates the construction of genealogical narratives. So, although historical stories are targeted at early education children of between 3 and 5 years of age, the future teachers write stories that make them begin to reflect on change and permanence, and for this, they use as their starting points cultural universals in daily life that can quite easily be compared with the present.

Finally, we would like to highlight the consideration in several stories of some events as relevant that are more difficult or “sensitive” to approach in class, such as those related to the Holocaust, the atomic bomb, the Berlin Wall and the Spanish Civil War, which, although infrequently, are beginning to emerge among the proposals precisely on account of the value that reflecting on them might have for values education.

texto en

texto en