The Teacher Performance evaluation is an evaluation system for education professionals who exercise as a classroom teacher. Its origin dates back to June 25th, 2003 as a result of a tripartite agreement, signed by the Ministry of Education of Chile (MINEDUC), the Municipalities Chilean Association and the Teachers’ Association of Chile, Law 19,961 (CHILE, 2004a). The purpose of the agreement was to strengthen the teaching profession, evaluating the strengths and overcoming the weaknesses of teachers, in order to obtain more quality in the learning of their students.

In this way it is intended to encourage and promote the strength of the teaching practice, which can be used to give a quality education to children with more and better tools (ARELLANO; CERDA, 2006).

The Chilean Ministry of Education is responsible for teacher evaluation through the Center for Improvement, Experimentation and Pedagogical Research (CPEIP). For its execution, MINEDUC requests technical advice from the Measuring Center of the Catholic University of Chile (MIDE UC). In this center is constituted the teaching team responsible for the evaluation process, in both aspects, technical and operative. Pilot studies and statistical analyzes related to teacher assessment were also carried out (MANZI; FLOTTS, 2007).

Teaching performance is evaluated every four years. If the teacher obtains an unsatisfactory evaluation, he is evaluated the following year, and if a basic result is obtained, he must be evaluated again in a period of two years. The localities to which these teachers belong receive resources with which they should implement Professional Improvement Plans (PSP), which should improve the weaknesses found in the teaching performance evaluation (MANZI; FLOTTS, 2007).

The assessment of the process of teacher evaluation is regulated by the Law 19,961 (2004b), through four instruments that recognize the information of their practice: a portfolio, the vision that individual being evaluated has of his teaching performance, the opinion of his peers and that of his hierarchical superiors. Specifically, the instruments are:

Design and implementation of a pedagogical unit.

Final evaluation of the pedagogical unit.

Reflection on his teaching work.

Filming a class.

Once the evaluation is completed, the teacher obtains a final result that corresponds to one of the following categories of teacher assessment regulation, 2004:

Outstanding performance: Indicates a professional performance that clearly and consistently excels with respect to what is expected in the indicator evaluated.

Competent performance: Denotes an adequate professional performance in the indicator evaluated. Fulfill what is required to practice as a professionally teaching role.

Basic performance: Indicates a professional performance that fulfills the expectations of the indicator evaluated, but with some irregularity (occasionally).

Unsatisfactory performance: Indicates a performance that presents clear weaknesses in the evaluated indicator and these significantly affect the teaching task. Those who refused (for some reasons) to submit this evaluation are included (p. 5).

INTERNATIONAL EVIDENCE

From the international background, different countries such as the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Austria, Scotland and France, have concentrated their efforts on defining criteria for professional performance, as elements of reference of policies for strengthening and evaluating the teaching profession (VAILLANT, 2016), and not differing too much from the Chilean reality, to be able to raise the quality of teaching.

However, most education systems refer to basically two aspects: improve or ensure the quality of teaching, and obtain data to make decisions regarding teaching, whether for salary increase, training and promotion (MURILLO, 2007).

In Latin America, several efforts have been made to define effective teaching based on the development of teaching profiles in several countries (ARREGUI; DÍAZ; HUNT, 1996, VAILLANT; ROSSEL, 2006). In this line, the proposals aim to establish curricular advances that allow impact on the teaching performance. Authors such as Vaillant and Rossel (2006) mention five fields: specific intellectual abilities; mastery of teaching content; didactic competitions; professional and ethical identity; and ability to perceive and respond to the conditions of their students and the school environment.

Although the different fields of intervention indicated by the previous authors are interesting, it is important to be able to consider other elements that allow a more general perspective of the teaching performance. Although the different fields of intervention indicated by the previous authors are interesting, it is important to be able to consider other elements that allow a more general perspective of the teaching performance. It is also important to monitor the effects, at the classroom level, that originate the poor performance of teachers and to approach the perception of performance in the classroom of outstanding teachers, as a way to identify good practices and the factors that favor the educational quality.

PROFESSIONAL IMPROVEMENT PLANS (PSP)

In the context of teacher evaluation, the Professional Improvement Plans are ruled by Decree No. 192 of 2004 (CHILE, 2004c), which regulates the Teaching Assessment and defines it as: “Set of teacher training actions, designed and executed in accordance with this regulation, aimed at favoring the overcoming of the professional weaknesses evidenced by teachers with a Basic or Unsatisfactory performance level” (p. 17).

The PSP guidelines are used to promote development spaces at the community level that allow teachers authentic learning and/or strengthening of the knowledge, skills and abilities declared in the Framework for Good Teaching, which will result in the improvement of his teaching practices.

The ultimate goal of the PSP is that teachers have, permanently and growing, more and better professional tools to improve the quality of their students’ learning.

APPROACH AND FORMULATION OF THE PROBLEM QUESTION

The assessing of the teaching performance must be done, in a mandatory way, by all teachers in the municipal system. This process, according to the professors, is very demanding, rejected by many, feared by several, without legitimacy, does not consider the context, is distressing, and more than one succumbed to the doctor (TORNERO, 2009).

These observations could be considered a harbinger of the results obtained, since each year a percentage of teachers that fluctuates between 30% and 35% is categorized with basic and unsatisfactory teaching performance (CHILE, 2016). The same figures also include teachers who refuse to participate in the teaching assessment, when it is appropriate to do so. These results, which are worrisome, lead us to ask: at what causal factors do the teachers of basic education, poorly evaluated, attribute the result of their teacher assessment? What level of commitment and time did they dedicate to their teacher performance assessment process? What kind of emotions did they experience when knowing the results of their evaluation? When they return to the teaching evaluation, what will be the points they must consider to improve their results? These and other questions guide the present study.

In regard to our object of study, teachers are a very important representative source of information for the deep knowledge of the in-classroom reality. From this perspective, it seems relevant to intervene in a field that, generally, is not considered in the improvement and decision making in the educational field.

Due to the background and the problems presented, the objective was to interpret what were the factors that, according to the teachers of basic education in the municipality of Osorno, had an impact on the results of the teachers’ assessment in 2015 and 2016, and to what extent this result obtained corresponds to his teaching performance.

METHODS

This research is of qualitative nature with a phenomenological design. Thus, in the words of Husserl (1967),the subject makes a reflection about the objectivity of knowledge, from the reality of teacher evaluation, but that in turn creates an awareness of the context in which the instrument was applied and developed, and the effects that could occur in this course, turning the assessment into an evaluative process of time, subjects and actions.

Therefore, to understand the process, subject and actions, a case study was conducted in order to deepen the experiences of the actors involved, and according to Stake (1998), when a case is studied in a group, it allows to identify the particularity in the depth of the situation as an integrated system of perceptions regarding teacher assessment.

PARTICIPANTS

The study was applied to teachers whose teaching performance was evaluated in the district of Osorno, in 2015 and 2016. These were 550 (MINEDUC, 2016). 15% of them were evaluated with outstanding performance. On the other hand, 25% were evaluated as basic and insufficient. For the purpose of the research, 112 poorly evaluated teachers participated in that period, which represents 82%. Mostly, teachers who work in the first and second cycle of basic education, differential education and preschool.

The teacher sample was not probabilistic with an accidental character (LABARCA, 2001). This means that all the teachers poorly evaluated participated, except those that for some justified reason don`t participated in the professional improvement plan.

According to Krejcie and Morgan (1970), the size of the sample offers guarantees to ensure that the results are representative of the population.

INSTRUMENT

The Survey was chosen as the instrument for collecting the information, which was applied at the beginning of the Professional Improvement courses. This instrument consists of eight open-ended questions. The instrument’s thematic scopes were: factors to which are attributed the results; amount of time and commitment dedicated to the educational evaluation process; emotions experienced when discovering your evaluation’s results; attitudes or behaviors expressed by colleagues when learning about their results; aspects that you should consider to improve your educational evaluation; correlation between the evaluation obtained and your performance in-class and problems you had to overcome while developing your educational evaluation.

INSTRUMENT VALIDATION

Expert judgement was used to estimate the validity of the Survey (HYRKÄS, 2003). Skjong and Wentworht (2001) were followed. They propose, for the selection of judges, the criteria of: Experience in instrument validation, studies, academic production, peer recognition as a qualified expert, availability and motivation to participate.

In relation to the number of judges, was considered what was posed by (MC GARTLAND et al., 2003), who suggest a range of 2 (two) to 20 (twenty) experts. The instrument was validated by three experts. The steps for the validation were:

Define the method and the purpose of expert judgment.

A method of individual adding is chosen. Each expert carries out the survey’s assessment individually and the results are analyzed to incorporate suggestions for changes and improvements on the instrument.

Selection of experts. The following criteria were considered:

Validation guidelines: The judges were given a validation guideline which considered the preset criteria: Clarity and accuracy of the question; Structure of the instrument: grammar and syntax; Length of the instrument and number of questions; Logical order of the questions, among others.

Experts’ report: Documents with the notes and suggestions

Forms design: collect the experts’ notes to order, refine and summarize the information delivered by the judges

Observation analysis: The judges’ answers and the concordance between them are valued.

Incorporation of the modifications to the final instrument: It is verified that the observations and points made by the experts are distributed in the category of good. There were observations of form more than of substantial nature, which were accepted and incorporated.

FIELD WORK

All teachers who participate in the Professional Improvement Program are invited to an extended meeting, where they are told about the purpose of the study, the need to know their opinion about their teacher valuation, the importance of the veracity of their answers, the commitment to get the results to the authorities to search for alternatives of improvements to the situations that will be presented, as long as we are given their consent to apply the Survey.

It is made clear the anonymity of the data provided and the freedom they had to answer the questions. Once a trust environment was created, the instrument was administered to all the teachers who were in the room.

The time utilized to answer the Survey was of approximately an hour. After the field period, a work of systematization, categorization and tabulation of the collected data and information was initiated.

USED ANALYSIS

A thorough analysis of the information, through the program ATLAS TI 7.0, allowed us to carry out a speech analysis for each of the answers of the interviewed teachers, through categorization, which facilitated ordering conceptually the events that are applicable to a same subject, since one category contains one meaning or different types of meanings andthey can be situations or contexts, activities or events, opinions, feelings, perceptions about an issue, methods, strategies and processes (OSSES et al., 2006). A selective coding of concepts (one or more words) was made, and they can be repeated and form a common model of answer, allowing to minimize the initial set of categories based on the intensive analysis of the relationship between the central category and the rest.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

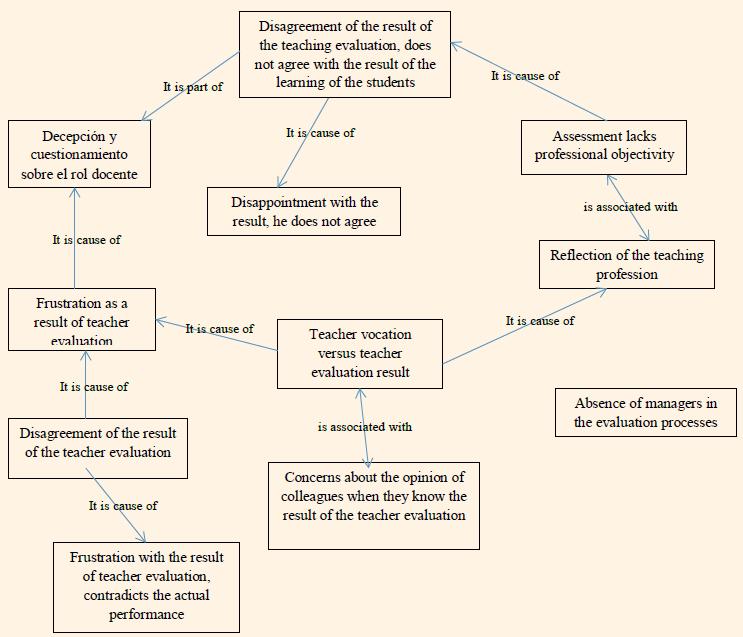

The feelings a teacher can experiment when faced with an evaluation that is bounded to results and learning experiences centered on the student can cause frustrations, that contradict the real performance that the teacher has and the learning experiences that he has fostered in his students.

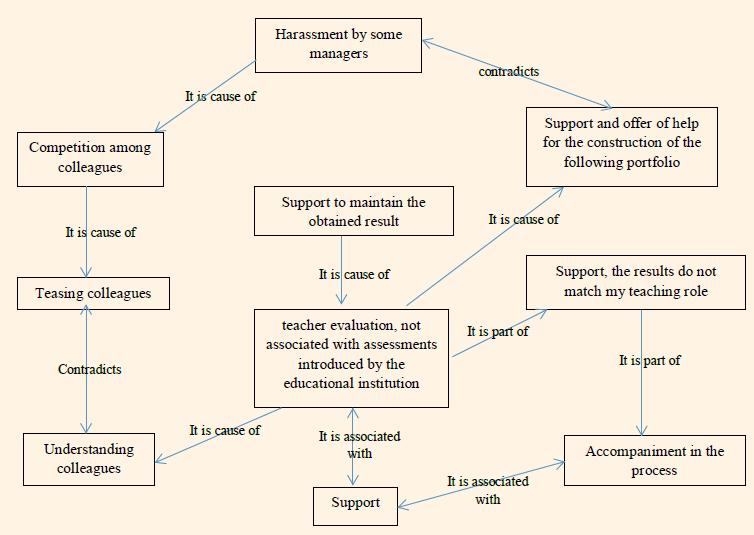

In the words of Schön (1998), the teaching praxis is characterized by the complexity, the uncertainty, the instability, the singularity and the conflict between technical perspective and problem management in the school classroom. Therefore, the constant worry of the teacher about their colleagues’ opinion upon knowing the results of the teacher evaluation can cause disappointment and question the teaching role. To this effect, they need the support of their peers and of the educational center, so the feedback from those who have already gone through this process could made them share their experience, and such scope would generate a feeling of well-being and tranquility in front of a highly subjective measuring process that would otherwise generate a state of stress in the teacher and his environment (HERNÁNDEZ, 2002).

Consequently, the teaching process is affected by these situations, which generate a difficulty in the student learning; therefore, the greatest well-being of the teacher, the more effective the influence will be in the levels of achievement of their students (BAKER et al., 2010). While the public policy is looking to improve the standards in the educational processes, the diversity of the applied instruments leave aside competencies such as transmitting knowledge from empathic models, associated to the learning environments created by the teachers, area that is left outside in the technical instruments. Then, it would be ideal to make viable the possibility to adapt this sections along with other measurements to include a broader evaluation approach.

Currently the evaluative processes standardize the competences of the teachers from psychometric parameters (MUÑIZ, 2017), leaving aside the coercive or of common agreement, to become a process that is part of public policies. However, the measurements center their structure in the results but leave aside the teacher’s support mechanisms, situations that push them to undergo the evaluation only to comply with the structures required by the Government, and the educational centers that look for teaching excellence.

Making the teaching experiences implemented in the classroom invisible, the State policies evaluations do not associate with the evaluations established by the educational institutions, which have the purpose of identifying the learning strategies applied by the teacher in the classroom (MATAMOROS, 2016).

Thus, the reflection that is made by the teacher on the results and support mechanisms provided by the educational center is that they are not bilateral but opposite, since the first seeks excellence to improve students’ learning and the second measures the strategies and instruments and doesn’t consider the result and effect of this strategy in the students (SCHÖN, 1998).

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

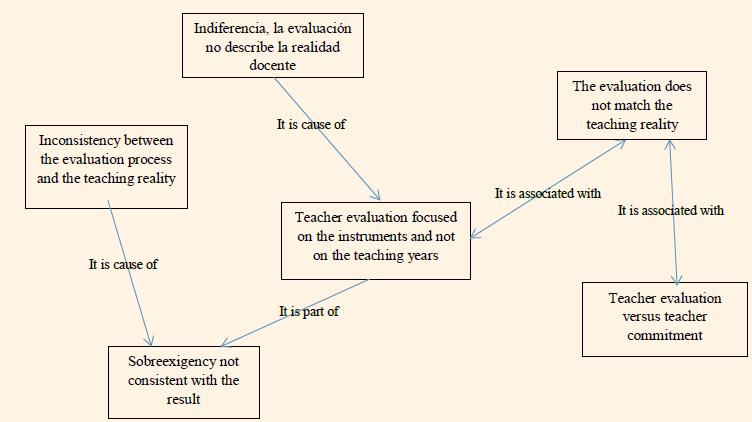

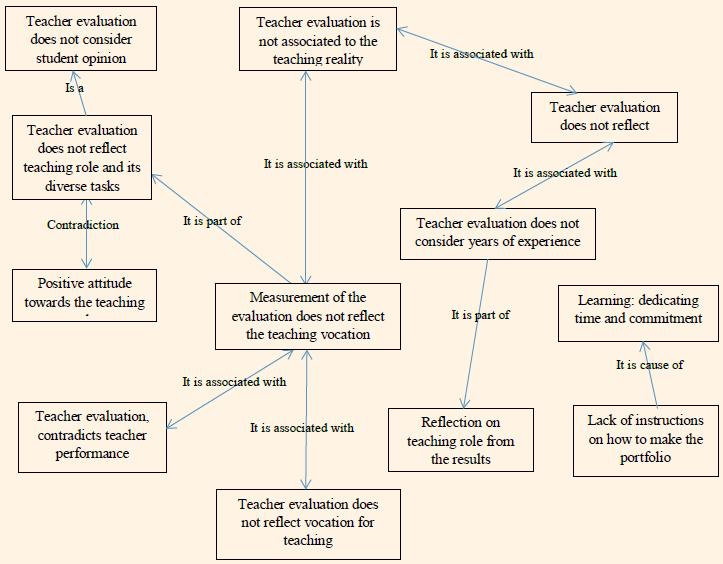

FIGURE 3 TEACHER EVALUATION: REALITIES NOT NEAR THE TEACHING PROFESSION

Proficiency over the use of the portfolio and the way in which it should be designed is one of the strains a teacher faces when preparing to be evaluated. Thus, they should invest time in the search for information and bibliography that orients them on the diversity that exists for its elaboration. At times, such evaluation is discordant with the teaching role, and for some it does not consider experience or achievement over the previous years. As Martínez (2013)affirms: “Teaching and teaching practice are in themselves complex and multidimensional constructs”, that leave aside the reflection over the teaching role, from the results.

The reflection towards teaching performance evaluations from the teacher’s statements is shaped to be an instrument which measures from the subjective appreciation of another, who at times has different process and therefore contaminates the reality of what the teacher develops at the time of being evaluated (JORNET, 2012). It causes a discordance between teaching reality and teaching commitment. Structuring in systematic cacophonic actions between results and demands made by the educational centers, such circumstances cut off any possibility of reflection on the teaching role and practice (DEWEY et al., 1989). Therefore, the evaluation should be of multidimensional character and should maintain a coherence between the school classroom reality and the measuring instruments applied. Ultimately it is being accepted by the institutions as a possibility to enhance the process of improving teaching strategies and not the association to control the teaching performance (RUEDA, 2010). In this way, reflection can be possible, allowing the teacher to feel that more than being measured, it is demonstrating his highlighted characteristics in the teaching process and that these, at the same time, can be replicated and learned by their peers, giving way to a variety in teaching strategies according to the context and profiles of teachers and students.

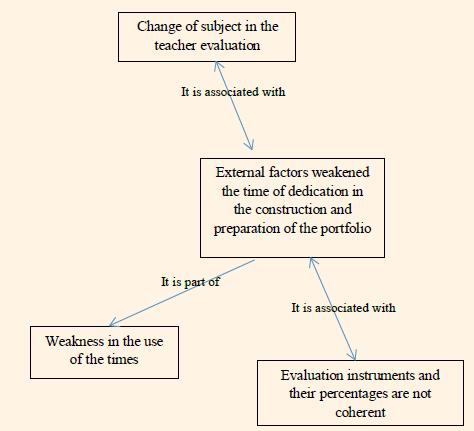

The emerging variables at the moment of carrying out or preparing for a teaching evaluation, generate a gap between reality and the years of academic experience, for it is understood that this process of measurement identifies in in the action of teaching the successes and failures, with the purpose of channeling, stimulate and building the respective scopes. But, at the same time, its bigger achievement is to validate the performance quality in the school classroom (PARRA; CORREA; ZULETA, 2001).

Nevertheless, some teachers mentioned in the interviews that they were evaluated in subjects that were not of their field, which forced them to perform in areas in which they didn’t have a vast experience; these facts were not considered within the wide range of emerging circumstances that arise at the moment of evaluation. Likewise, there is a manifesto in the weakness of the times, since the introduction of a new person to the classroom generated uneasiness in the students, causing some distraction during the class development. Due to this, we should reflect upon the traditionality of the evaluative instruments in order to adapt them to the new learning contexts and characteristics that are being established in the school classroom (VAILLANT, 2016).

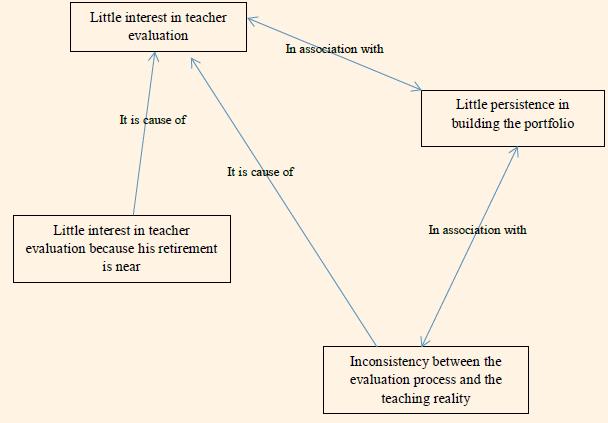

The acknowledgement from the teachers of the weakness they have upon building a portfolio and then a strategy for an optimal development of a class, at times disguises the reality of a classroom, creating incoherence between the evaluation process and the teaching reality, since they manifest little interest in the teaching evaluation and in some cases the proximity to retirements from the teacher practice adds on to it. Consequently, the interest in minimum. Nevertheless, it is worth stressing that the absence of training and orientations about how to face the teaching evaluation conducts stress states accompanied by the lack of time for preparation, and therefore it becomes a “conception of reality that is in no way a real image of the individual, but that which is pre-designed for a precise moment” (EDWARDS, 1995).Therefore, the low results can be associated to the fact that the evaluative instances are not considered the career path but an “in situ” which can be affected by external factors (change of subject, students’ mood, presence of an individual not identified by the students).

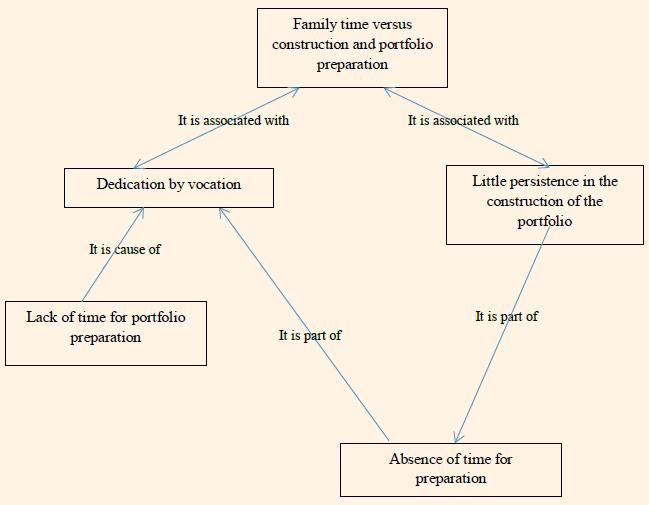

The absence of additional time for the construction and preparation of the portfolio increases in teachers the need to search for external consultancy and other instances. Moving away from the pedagogical relations and leaving an unreal reality of an ideal “outstanding teacher”, isolating that dynamic emerging construction of those who exercise teaching because of a calling of a constructed reality based in parameters of measurements (GYSLING, 2017). Meanwhile the teacher’s identity is not coherent with what is experienced on a daily basis. Then, the level of commitment is associated with the not existent enthusiasm that teachers have, even though some teachers expressed that the invested time was time taken from family time, therefore reflecting a calling for teaching.

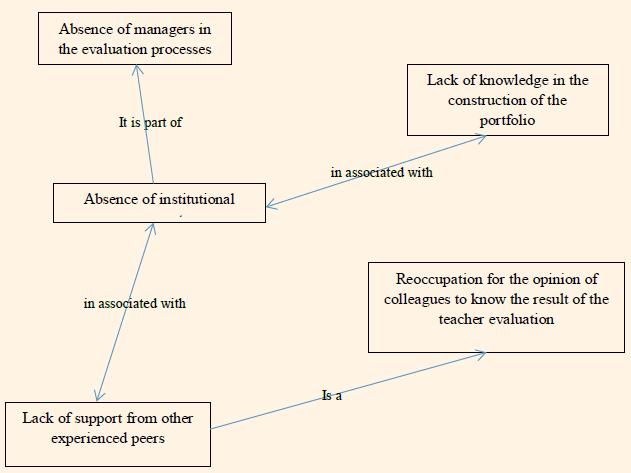

The absence of support from the administrators in teaching evaluations is a constant in the experiences narrated by the teachers, since they consider that while the teacher evaluation gives the individual and the institution a certain status, the support they receive from the institution is devoid. At the same time, the intentional silence from those peers that have already undergone the evaluation is creating a culture of silence and selfishness at the moment of orientating or lending help to those who are preparing to present themselves; at times this tense situation originates atavistic fears about the concern for the opinion of colleagues upon knowing the result, and these at the same time consider that they have gone under the same experience and needs, and therefore show a passive empathy towards their peer. The results of the investigation show evidence that teachers differ in first instance about the results obtained in their evaluation; it was found that, according to their perceptions, evaluation does not comply with the characteristics a professional evaluation should take on.

Mainly, teachers estimate that the evaluations do not possess a collaborative character, with elements that can truly contribute to its improvement and specifically, in relation to the portfolio, it is pointed out as the main cause for the lack of time in their preparation. Likewise, they express, in percentage-equitable figures, lack of support and ostensible differences between their classroom tasks and what is require in the portfolio. Together with what was mentioned before, but in a lesser scale, they take on levels of insecurity and dislikes when facing the process.

Incidentally, the teachers’ attitudes towards the acceptance that they have been qualified as “basic” or “unsatisfactory” teachers were of negation, hostility and resistance. Those attitudes were present during all the Professional Improvement Plans activities. Despite this, at the end of the process they take away a positive appreciation recognizing knowledge, responsibility and empathy and passive comprehension towards their peers.

CONCLUSIONS

According to the analysis of the collected information during the development of the present investigation, is it feasible to conclude that, in relation to the operative form to face the evaluation process, the participants express to have faced it in an individual manner, with no collaboration from peers or guidance of any sort, with limited time available for preparation and without support from the respective educational unit; along with that they assume that there was, on their part, overconfidence reflected on the lack of importance given to the process and, at the same time, presence of insecurities.

Along with that, they mention that their actions considerably differ from those made by them in the teaching performance evaluation. They consider that they have a good performance in the classroom as well as in the school. Despite these records, they point out that the results obtained were not as expected, therefore they feel deeply disappointed and affected, with an important sense of frustration, a mix of anger and sadness added to distrust and resentment towards what they perceive as disloyalty from their peers. They declare that, at the end, the entire educational community takes notice of their evaluation, fact that had an impact on their self-image, self-esteem, and they feeling judged.

This last aspect was felt with a greater negative emotional load at the moment of knowing the results due to the fact that, in most cases, they point out to not feeling supported; only a minority expresses to have received collaboration, since their lack of time was known in their working context.

They express that the vulnerable socioeconomic context in which they work, the limitations and comparative disadvantages are not considered in their teaching evaluation. Many students with special needs, serious social and family problems are part of their classrooms and in many occasions they do not have the capacity to solve these problems because they lack the formation or the required training.

In regard to the evaluative instruments, the teachers involved consider, in its majority, that these do not adjust to the working reality, therefore they are referred to as subjective and of little reliability.

In terms of feedback, an important number was dissatisfied with the given information, once the process ended; this is associated to the fact that they esteem that there is a lack of clarity in the process. In lesser percentages, they show satisfaction with the given information, but the quality of it does not satisfy as a referential element to adapt the pedagogical conducts in the future, as a concrete possibility of professional improvement in the pedagogical work.

Finally, it is important to make available to those who make the decisions the results of the present study, in order to evaluate the procedures that today are affecting teachers and so, from their respective functions, they could propose solutions. For instance, guarantee hours within the working day destined to elaborate the portfolio from a collaborative working perspective at peer level.

texto en

texto en