The Law no. 10.436 (BRASIL, 2002) officially established the Brazilian Sign Language (Libras) as a linguistic system for the communities of deaf people in Brazil, thus securing the use and dissemination of this language by the public authorities. From this legal framework, school institutions have become obliged to adapt in order to provide deaf students with the right to a bilingual education in which Libras is recognized and valued as their first language.

To enable bilingual education for deaf students, the decree no. 5.626 (BRASIL, 2005), among other provisions, determined the inclusion of Libras as a curricular discipline in undergraduate courses and established guidelines on the qualification of the Libras teacher.

Thus, according to Chapter 2 of the aforementioned decree, Libras became “a compulsory curricular discipline in qualification courses for the teaching profession, at the intermediate and higher levels, and in Speech Therapy courses”1 (BRASIL, 2005, p. 28; own translation), in addition to becoming an elective course for other graduate and professional education courses. This measure complied with art. 59 of Law no. 9.394 (BRASIL, 1996), which determines that education systems will ensure the special education student (which the deaf integrate),2 teachers with specific training to provide them with specialized educational services, and regular teachers trained to work in usual classes. It is worth remembering that Resolution CNE/CEB n. 2 (BRASIL, 2001) clarifies that trained teachers are those who, in their middle or higher education, had contents that trained them to work with students who are part of the target audience of special education. From this point of view, teachers who had the discipline of Libras3 in their initial training are considered qualified teachers to assist deaf students from their area of education, be it math, geography, history, etc. In other words, a trained teacher with qualification, for example in mathematics, may work with deaf students in common class or bilingual classes and schools for the deaf, teaching curriculum content in mathematics.

On the other hand, the teaching of the Libras curricular discipline rests with another professional, whose profile of qualification and performance was subdivided in Decree n. 5.626 (BRASIL, 2005) in two segments.

For “the teaching of Libras in early childhood education and early years of elementary education”, the required training consists of the Pedagogy course or Normal course (higher or intermediate level), “in which Libras and written Portuguese have been languages of bilingual education” of the individual.4 On the other hand, to function in the teaching of Libras in the “final years of elementary school”, “high school” and “higher education” the qualification must take place by means of “graduation course with a degree in Languages: Libras or Languages: Libras/Portuguese as a second language” (hereinafter Languages Libras)5 (BRASIL, 2005, p. 28) (own translation). According to Quadros (2006), in order to comply with the legal decision involving the insertion of the Libras discipline in graduation courses, initially, it was faced with the inexistence of qualified teachers for its teaching.

Faced with the need to meet the immediate demand for these qualifications and considering that the courses mentioned were practically non-existent until then, the aforementioned decree established a provisional period of ten years, in which unqualified professionals could be admitted to teach Libras through the certification obtained through a proficiency exam in Libras, promoted by the Education Ministry [Ministério da Educação] (MEC).

However, since its publication, according to the article 11 of Decree n. 5.626/05, MEC was tasked with promoting specific programs for the creation of undergraduate courses for the training of deaf and hearing teachers qualified to teach Libras (BRASIL, 2005). In compliance with this determination, it is possible to contemplate the proposal of the National Plan for the Rights of People with Disabilities - Live Without Limit Program (hereinafter Live Without Limit Program) (own translation) - (Plano Nacional dos Direitos da Pessoa com Deficiência - Programa Viver Sem Limite), officially established through Decree n. 7.612 (BRASIL, 2011), among its goals for the period from 2011 to 2014, the expansion of bilingual education in the country through the creation of 27 Libras Language courses (licenciate and bachelor degree) and 12 Pedagogy courses in the bilingual perspective (BRASIL , 2013).

Given the above, considering that the acceptance period of the temporary professional profile for teaching Libras ended on December 22, 2015, it is necessary to unveil the reality that happened in our country to enjoy the right of deaf students to a bilingual education provided by professionals with legally-endorsed training. For this reason, the aim of this article is to identify and analyze the developments of higher education policy for teacher training in Libras during the decade following Decree no. 5626/05,6 by means of mapping the entrance announcements and the analysis of the offer conditions of Bilingual Pedagogy and Languages Libras courses made by the federal institutions of higher education [instituições federais de educação superior] (Ifes). In this way, we will first approach the context concerning bilingual education for the deaf, thus positioning our theoretical foundation.

SITUATING THE TEACHING OF LIBRAS

For a long time, the discourse of disability, authorized and legitimized by the oral practices that advocated (and still do) the standardization and rehabilitation of deaf people under the focus on the use of auditory residue, the benefit of technologies in the field of audiology, orofacial reading, speech training, among others.

Under the aegis of this oralist conception, in addition to curtailing the use of sign language, oral language learning overlapped with curricular content, and with it, the school performed a similar role as a “repair clinic” for the deaf, assuming “a pedagogy of correction, of normalization of the other that is different”7 (GESSER, 2012, p. 86; own translation). Many deaf people educated in this approach report that they had their hands tied during the school experience as a way to prevent them from communicating through sign language (GESSER, 2012).

According to Albres (2005), the understanding of sign language as harmful was even supported by the first national curricular proposal for the education of the deaf, published by the MEC in 1979, in which the sign language was not recommended, becuse it was alleged that it restricted the expression of concrete concepts and impaired the acquisition of writing by deaf students. The author adds that, in the 1990s, the teaching of sign language, not yet officialized in the country, began to be considered as an alternative by the MEC guidelines, although the bias of the documents still portrayed the specialized teachers as technicians and speech therapists, whose pedagogical action, based on oralist philosophy, consisted, essentially, of acquiring oral language.

According to Skliar (2016), this scenario began to change in Brazil in the 1990s, when the representation of the deaf and deafness as disabled and disability, respectively, began to be produced by some scholars and professionals under a new ideological conception based, respectively, on the different and difference. In the words of this author, it was a moment that led to the strengthening of socio-anthropological discourses about deafness, mainly influencing school organization and pedagogical practices dedicated to the education of the deaf.

Thus, the deaf person, as a bilingual individual having recognized Libras as his first language and Portuguese as the second language, is part of the conception of socio-anthropological bias, a term that has become widespread in the area and a concept which we are affiliated with to construct this article.

In the context of this discussion, it should be noted that the arguments are not restricted to the use of sign language as an identifying aspect of this group. In agreement with Lopes (2011, p. 22-23, emphasis added; own translation):

[...] ways of relating, ways of identifying with some and distancing oneself from others, ways of communicating and using vision as an approximate link between similar individuals are implied. Deafness in this narrative is marked by the presence of a set of elements that inscribe some individuals in a group, while others are left out of that group.8

Following this analysis, the ways of communicating and experiencing the world through the visual experiences constitute the identity markers of the deaf communities (LOPES, 2011), not only the sign language and in no way the biological character. In fact, the view of the deaf and the deafness from the lens of the concept of linguistic difference presupposes the distancing of biological theories and, in consonance with Santana and Bergamo (2005), this posture is also associated with a terminological and conceptual change, abandoning expressions such as “hearing impaired”, whose semantics is based on absence, to accept the “deaf” or “Deaf” nomenclature.

For Brito (2013), this new look at the context of deafness was central to consecrate the greatest achievement of the deaf communities in the country, since it guided the organization of the Brazilian deaf social movement, fomenting a series of demands that resulted, in 2002, as already mentioned, with the official recognition of Libras in our legal system (BRASIL, 2002).

From the legal recognition of its bilingual condition, to the deaf was granted by the public power, according to arts. 22 and 23 of Decree n. 5.626 (BRASIL, 2005, p. 29; own translation) among other provisions, that “federal educational institutions” promote to this public, from “children’s education”, “bilingual schools and classes” with “bilingual teachers”; “regular schools of the regular system” with teachers “aware of the linguistic singularities of the deaf, as well as the presence of translators and interpreters of Libras”; and in the scope of higher education, besides “translators and interpreters of Libras”, the provision of equipment for “access to information, communication and education”.9

In addition, it should be noted that the National Education Plan (Plano Nacional de Educação - PNE), approved by Law n. 13.005, reinforces the determinations of the referred decree, establishing as one of its strategies:

4.7) to guarantee the offer of bilingual education, in the Brazilian Sign Language - LIBRAS as the first language and in the written language of the Portuguese language as a second language, to the deaf and hearing impaired students from 0 (zero) to 17 (seventeen) years old, in schools and bilingual classes and in inclusive schools [...].10 (BRASIL, 2014, p. 3; own translation)

According to Quadros (2006), the proposals of the deaf communities have always been focused on defending a bilingual school with bilingual teachers, preferably deaf. However, as pointed out by Campos (2013), although there is a preference for bilingual schools for the deaf, not all Brazilian municipalities rely on this structure. In these cases, two alternatives adopted for the guarantee of bilingual education for deaf students have been the bilingual education classes in regular schools and the common classes with the presence of translators and interpreters of Libras-Portuguese (TILSP). In the first space, the deaf are with their peers in the same room, accompanied by bilingual teachers who use the Libras as a language of instruction. Already in the second proposal, the language of instruction is Portuguese and mediation between the deaf student and his peers and listening teachers occurs by the figure of TILSP. It should be noted that in schools and bilingual classes the teaching of Libras as the first language of the deaf and Portuguese written as a second language will occur as curricular subjects, while in the configuration of the common classes with the presence of the TILSP, generally, the learning of Libras and Portuguese Language will take place through the specialized educational service offered by the services of special education in the period after/before school (DAMÁZIO, 2007). In both cases the Libras teacher is necessary, because it is a right of the deaf students, but in the specialized educational service, often, this task is attributed to the specialized teacher, whose qualification has been made feasible from a more generalist profile, because their work is advised to the target audience of special education. This means that these professionals may not have the necessary training for the teaching of Libras, except those who have a dual qualification, that is, in special education and teaching of Libras.

This special education organization is criticized by some advocates of the socio-anthropological conception of deafness. For Skliar (2016), special education is guided by the representation that the deaf, the blind and people with intellectual or physical disabilities have something in common, and that this similarity is based on the organic issue linked to a clinical report that seals the access to their services. In opposition to this reasoning, the author proposed the split between special education and the education of the deaf, from a new conceptual field: the deaf studies.

Also known in international studies, especially in the United States, as “deaf studies”, in Lopes’ words (2011, p. 13; own translation), deaf studies integrate “a wide range of themes, problems and theoretical approaches that have contributed a lot to a deeper, refined and nuanced understanding of the deaf and the deafness”11. According to Lunardi (2016), deaf studies are aligned with the concept of deafness as a difference and are closely related to cultural studies, as well as being a conceptual field for political and educational debates articulated with linguistic, community, and identities studies covering the theme of deafness.

Although many researchers agree with Skliar (2016) on the need to break the education of deaf people with special education, it is worth noting that special education has advanced in recent years toward the substitution of organic conceptualization for a social model of disability, whose proposal shifts studies on this context, traditionally situated in the biomedical field and based on physical impairments, into new theoretical and political perspectives (DINIZ, 2013). In this regard, it is possible to mention the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [Convenção Internacional sobre os Direitos das Pessoas com Deficiência] (BRASIL, 2009), which abandons the biological definition of disability in order to register an understanding that this condition arises from the interaction between disability of the individual and attitudinal / environmental barriers. In the wake of this social conception, the term “disabled” is rejected because it circumscribes disability exclusively in the individual, as an individual aspect of the “disabled person”, in other words, that does not belong to society (DINIZ, 2013) and replaced by person with disabilities.

In view of the above, there is a trend of distance from special education (similar to what happens with the education of the deaf) in relation to the clinical approach and located only in the individual, which has allowed that studies under socio-anthropological bias have been conducted, also, by undergraduate and graduate programs in special education.12

However, although that such movement of special education, we admit that there is still a great influence of the medical-psychological perspective in this area and that the concept of the disability located in the body of the individual, in practice, ends up being the preponderant factor for the grouping of this public. For this reason, Skliar (2016) argues that the deaf should be placed in a new conceptual theoretical field: deaf studies.

It should be pointed out that in accordance with the socio-anthropological view defended by deaf studies, we understand that deafness is assumed as a linguistic, cultural and identity difference. Thus, we place deaf people in the context of minority bilingualism, alongside, for example, indigenous and immigrant communities (CAVALCANTI, 1999; SKLIAR, 2016). This posture, even, is in line with the current national legal system, which has already recognized sign language, deaf culture and deaf people as bilinguals for almost two decades (BRASIL, 2002, 2005, 2014).

However, despite the legal support, we concur with Skliar (2016) when emphasizing that the mere admission of the deaf individual as bilingual has not guaranteed the reconversion of the problem. According to this author, we still witness a small percentage of deaf students accessing higher education, and although the democratization of access to a university course can also be restricted to hearers, it is undeniable that the picture is more alarming for the former. According to data from the 2010 Demographic Census (INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA - IBGE, 2010), 18% of the hearing population above 19 years old declared to have complete or incomplete higher education, while among the deaf population with the same age this percentage reached only 7%.

For Skliar (2016), three explanations have been repeatedly projected when looking for those responsible for the ineffectiveness of deaf education. The first blames the deaf themselves, inferring biological, linguistic and cognitive aspects that restrict them. A second explanation is centered on hearing teachers and a third on teaching methods, which should be more systematized and rigorous with the deaf. It is noted that the responsibilities of the State, the educational policies and the school institution are hardly considered.

The regulation of Libras by means of Decree no. 5.626 (BRASIL, 2005) established that the compulsory insertion of this subject in the curriculum of undergraduate and speech language courses is insufficient and, according to Lacerda, Albres and Drago (2013), there are still few undergraduate courses for qualification of Libras teachers, resulting in a scarce number of professionals trained to meet the demand for teaching Libras to deaf students.

In this direction, Gesser (2012) reports that the teaching of Libras has often been conducted by people without the necessary pedagogical qualification, under the simple requirement of mastery (or knowledge) of Libras.13 The author states that, in effect,

[…] knowing a language to use is not the same as knowing about a language to theorize. But for those who work in the pedagogical field, having linguistic notions about the functioning of languages is a basic premise of professional qualification14 (GESSER, 2012, p. 82; own translation)

In our opinion, the recognition of Libras as a curricular discipline not only in the undergraduate courses has been glimpsed (BRASIL, 2002, 2005), but also in the training program for deaf students, allowing them to progress in their first language, consequently, acquiring more linguistic and cognitive tools to achieve success in the second language, as it happens with the hearing students who have in school the opportunities to develop in their first language. For this reason we consider necessary to invest more in the training and hiring of qualified teachers to conduct the tuition of Libras, which corroborates the relevance of our proposal to analyze the offer of university courses in this area.

CONTEXTUALIZING THE RESEARCH

In order to understand the research context, we initially made an incursion into the literature by consulting four scientific production repositories, namely: the Portal of Periodicals of the Capes (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) [Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel] and its Bank of Theses and Dissertations; in the SciELO (Scientific Eletronic Library Online database); in the Brazilian Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations. Among the 55 productions found (14 journals and 41 theses and dissertations), published in the period between 2005 and 2015, only 14 references dealt with the higher teacher training courses in Libras, 10 of which were linked to Languages Libras and four to Pedagogy bilingual course.

It should be pointed out that in the scope of these 14 publications, three studies had as their research context the Bilingual Pedagogy course of the National Institute of Education of the Deaf [Instituto Nacional de Educação de Surdos] (Ines), a research study about the Bilingual Pedagogy course offered by the Santa Catarina State University (Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina) and the other 11 papers, involving the Language Libras course, were restricted to the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC). In this bibliographic review no research was found involving the other courses of higher education aimed at the training of Libras teachers.

According to a survey carried out in the registration system of higher education institutions and courses e-MEC (BRASIL, 2015), 34 institutions of higher education [instituições de ensino superior] (IES) were identified by 2015 (deadline of our temporal cut), with 27 public institutions (2 state and 25 federal) and seven private institutions, responsible for offering two Bilingual Pedagogy courses and other 36 degree courses in Language Libras.15

Among the 36 above-mentioned degree courses in Language Libras, four are offered in the distance education modality [Educação a distância] (EaD) for an amount of 27 poles. Thus, in Mato Grosso do Sul, the Federal University of Grande Dourados [Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados] (UFGD) presented two courses authorized by MEC, being distributed in three municipalities of the same state. Likewise, the Federal University of Paraíba [Universidade Federal da Paraíba] (UFPB) has, through a single course authorized by MEC, its distribution in six municipalities of the same state.16 On the other hand, UFSC stood out in the EaD modality, for pioneering and embracing the offer of degree courses in Language Libras in 18 municipalities belonging to 16 different states.17 In addition, when comparing the courses offer (whether in-person or distance) by Brazilian state, we noticed that Rondônia was the only one not included in the offer of undergraduate courses for teacher training in Libras.

Based on the delineation of this first panorama containing the IES and the undergraduate courses authorized by MEC for the training of Libras teachers, we began an electronic search for public notices of selective processes for admission to IES. From this pre-selection, we identified a great difficulty in finding public notices from private and state institutions, even resorting to contact via electronic address with some of these. Thus, considering the greater interference of Federal Decree no. 5.626/2005 on the public institutions and among them the expressive quantitative of federal ones, we decided to make a cut by IES, opting to focus on the training courses of Libras teachers provided by 25 Ifes and their respective 27 courses for the training of Libras teachers, being two Bilingual Pedagogy courses and 25 of Language Libras courses, including those offered in the EaD modality.

With clarity of our research context, we come to the definition of methodological procedures that guided us.

METHODOLOGICAL PATH

In the light of the theoretical and methodological presuppositions of documentary research (BAUER, 2002), we have elected as our corpus 80 public notices and 217 annexed and complementary documents of selective processes for admission to higher education courses aimed at the training of Libras teachers. The annexes and complementary documents included, for example, videos of tests in Libras, videos of the public notices in Libras, test templates, lists and partial and final results, etc. The videos were included for the purposes of this documentary research, in agreement with Le Goff (2003), for whom the document concept covers a diversity of categories, since it expanded from the twentieth century, admitting that its record can manifest itself in written form, illustrated or transmitted by image and sound. The public notices and the attached documents were of great importance to allow the intersection of information and inferences, for without this it would not be possible, for example, to map the number of subscribers and the number of approved only from the public notices.

The collection of these documents was done by means of an online search from the access to the institutional pages of the investigated Ifes and also through the Google virtual search engine. This online selection was based on the year of beginning of each of the courses authorized by MEC, according to information extracted in the e-MEC database. This strategy allowed recovering most of the documents of selective processes, with the exception of eight Ines public notices, referring to the selective processes from 2006 to 2012, which were located only in the Union Official Gazette [Diário Oficial da União].

For an analysis of the data, we follow the assumptions of content analysis. According to Bauer (2002, p. 195; own translation), there is more than one outline for a content analysis, with the same winners as the researcher approaching the same context over a period of time, thus allowing “the fluctuations, regular and irregular, in content, and infer concomitant changes in context”18. This was one of the premises which we aligned with during the analysis of the public notices from selective process to illustrate by means of graphic representations the scenario concerning the offer of teacher training courses in Libras between 2006 and 2015. Insofar as the documents were explored, the units of analysis were identified, followed by tabulation in a spreadsheet19 that allowed the recording of qualitative and quantitative data.

According to Lüdke and André (1986), the first stage of content analysis consists of the decision on the analysis units, which can be from a registration unit or a context unit. In the registration unit the verification will be guided by the frequency in which a topic or theme emerges in the text, whereas in the context unit it may be considered more relevant to observe, in addition to the frequency, the context in which the unit is located.

In the present research, the analysis units were distributed in columns of a spreadsheet. In this organization, cells of the spreadsheet were considered as context units in which the record consisted, for example, by excerpts of public notices paragraphs, in which the trigger element in question was contained. On the other hand, the registration units are being understood as those in which the filling was carried out to allow that within the spreadsheet is applied the filter based on its recurrence.

The procedures adopted are in line with the precepts of Lüdke and André (1986, p. 41; own translation), for whom in the content analysis:

There may, for example, be variations in the unit of analysis, which may be the word, sentence, paragraph or text as a whole. There may also be variations in how these units are treated. Some may prefer counting words or expressions, others may analyze the logical structure of expressions and utterances, and still others can do thematic analyzes. The focus of interpretation may also vary. Some may work on the political aspects of communication, others on psychological aspects, others on literary, philosophical, ethical, and so on.20

In this path, from our corpus we define some units of analysis guided by the registration unit and others by the context unit. Among these, included in the public notices, for example: year and semester of public notices publication (registration unit); name of the institution (registration unit); municipality (registration unit); state (registration unit); course name (registration unit); number of vacancies offered (registration unit); criteria to meet the priority of the deaf candidate and/or to obtain the accessibility conditions served (context unit); prediction of test translated into Libras (registration unit); prediction of additional time (registration unit); crossing between the affirmative action policy and the priority for the deaf (registration unit), etc. In the complementary documents it was possible to select as units of analysis, for example: public notices available in Libras by means of videos that had partial, summarized or total translation (registration unit); extra localized files (context unit); number of extra localized files (registration units); comments and observations (context unit).

In addition, it should be noted that our main documents of analysis were the public notices, since not all the institutions presented or published complementary documentation associated to its selection process, and therefore, the quality and quantity of these documents varied in each Ifes.

In the light of the above, we present partial results obtained with the research, being for this article focused the mapping of entry public notices and the analysis of the offering conditions for Bilingual Pedagogy and Language Libras courses performed by the Brazilian Ifes.

OFFER OF LIBRAS TEACHER QUALIFICATION IN FEDERAL INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER EDUCATION

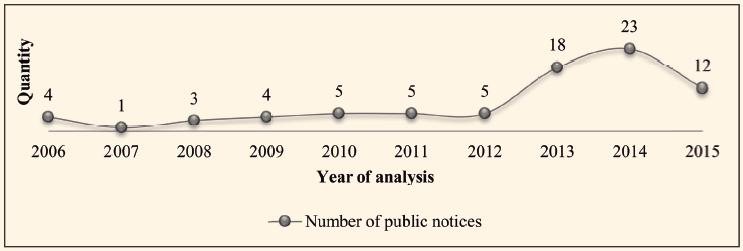

It should be noted that, since the Decree no. 5.626/2005 was promulgated at the end of the year, that is, on December 22, 2005, its effect could only be measured from the selective processes published in 2006. That said, our research covered the period between 2006 and 2015, when we found 25 Ifes that offered more than 4.315 places for the qualification of Libras teachers.21 The institutions with the highest tradition and volume in this area were the Ines with 11 selective processes, the UFPB and the Federal University of Goiás [Universidade Federal de Goiás] (UFG) with 7, the UFSC with 6 and the Federal University of Pará [Universidade Federal do Pará] (UFPA) with 5. The number of public notices of this segment produced by the Ifes can be followed in Chart 1.

Source: Prepared by authors based on the analysis of the Ifes public notices.

CHART 1 IFES PUBLIC NOTICES FOR SELECTED PROCESSES FOR QUALIFICATION OF LIBRAS TEACHERS - 2006-2015

It should be noted that the 80 public notices, in fact, come from 73 selective processes, since there were situations in which the same selection process was subdivided into more than one public notice. Nevertheless, as projected in Chart 1, there is a significant increase in the number of public notices in the period from 2013 to 2015, with 18 public notices in 2013, 23 in 2014 and 12 in 2015, resulting in an average of 17 public notices per year, reaching more than that the fourfold of the quantity envisaged in the years following the publication of Decree no. 5.626/2005.

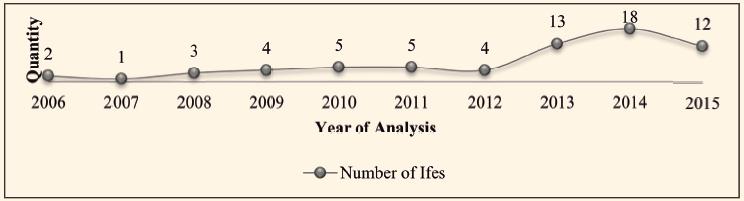

The increase in the number of public notices of selective processes is linked to the increase in the number of Ifes that were launched in this project, as illustrated in Chart 2.

Source: Prepared by authors based on the analysis of the public notices.

CHART 2 NUMBER OF IFES THAT OFFERED COURSES FOR LIBRAS TEACHERS QUALIFICATION - 2006-2015

Thus, one year after the profile formalization of graduation courses for teacher training in Libras was decided (BRASIL, 2005), only two Ifes (Ines and UFSC) proposed to offer courses in this segment, when in 2014, 18 can be verified, and one of them published three public notices of selective process that same year. With this, it can be noted that this growth has not occurred gradually over the years, but it has emerged, especially since 2012, a fact that can be at least partially attributed to the aforementioned Live Without Limit Program. This assertion is due to the fact that we have found reference to the aforementioned government program in the writing of Ifes selective processes, as well as reinforced by authors such as Quadros and Stumpf (2014), who also link it to the offer of Language Libras courses at UFSC.

However, the balance of the courses offer found is still not positive compared to the goal of the Live Without Limit Program, constituting as the most fragile segment in the training of Libras teachers for early childhood education and initial years of elementary education, which must be formed from Bilingual Pedagogy courses. Since the goal of this program was to create 12 Bilingual Pedagogy courses for the period from 2011 to 2014, no open courses were found in this interval, since the Ines course was inaugurated in 2006 and another one from the Federal Institute of Goiás [Instituto Federal de Goiás] (IFG) in 2015.

Regarding Language Libras courses, among the 18 Ifes found in 2014, four existed before the Live Without Limit Program, with only 14 of these courses being eligible for the goal calculation of creating 27 Libras courses. However, this math is not so simple, because it should be emphasized that among these courses, the bachelor degree courses not included in the present research can be included because they do not integrate our cut.

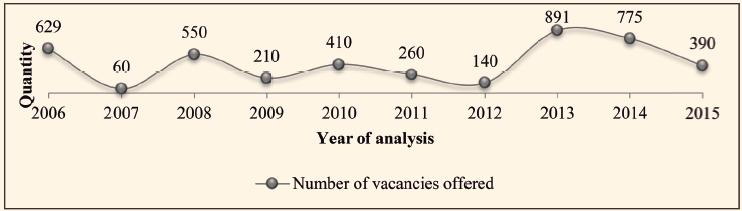

At any rate, another alert from this longitudinal analysis concerns the fact that the number of selective process calls and even of Ifes that have grown in recent years does not necessarily correspond to an increase in vacancies offered. According to Chart 3, the number of places was not always linked to the values corresponding to the quantity of Ifes and public notices.

Source: Prepared by authors based on the analysis of the public notices.

CHART 3 NUMBER OF VACANCIES OFFERED FOR LIBRAS TEACHER QUALIFICATION - 2006-2015

The analysis of Chart 3, compared to Charts 1 and 2, shows that, for example, in 2006, when there were only two Ifes and four public notices, 629 vacancies were reported, while in 2014, 775 vacancies were offered in 18 Ifes in 23 public notices. This disproportion is closely related to the modality of the training courses for teaching Libras, that is, whether they were in-person or EaD. Thus, distance education courses of three Ifes were responsible for the offer of 2,043 vacancies, which corresponds to 47%, while in-person courses managed by 24 Ifes totaled 2,272 vacancies, equivalent to 53% of the total vacancies of that period. Therefore, it is possible to assert that the EaD was a great ally in the expansion of the offer of vacancies for Libras teachers’ qualification.

For Quadros and Stumpf (2014), the use of technology allowed UFSC to promote the decentralization of professional training for the teaching of Libras, by making the course feasible for different Brazilian states and, thereby, serving a larger number of students and localities.

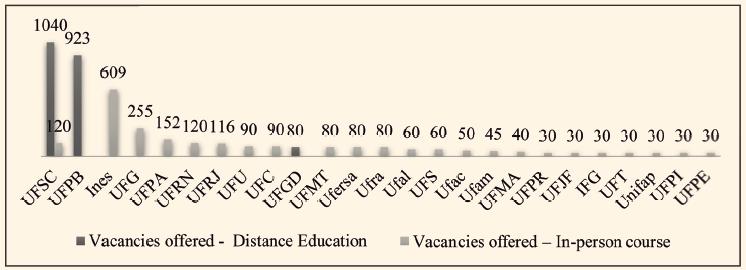

In fact, UFSC corresponded to the institution with the greatest number of vacancies for degree in Language Libras courses in the analyzed period. In all, there were 1,160 vacancies, of which 1,040 for EaD courses and another 120 for in-person courses. The UFPB also stood out as the second Ifes in this ranking, with 923 vacancies, all in the EAD mode, distributed among the states of Paraíba and Bahia. It can be observed, therefore, that these two Ifes together total 2.083 vacancies, corresponding to almost half of the offer in the period from 2006 to 2015. A sample of this distribution of vacancies by Ifes and modality of education can be followed in Chart 4.

Source: Prepared by authors based on the analysis of the public notices.

CHART 4 TOTAL VACANCIES OFFERED IN GRADUATION COURSES FOR LIBRAS TEACHER QUALIFICATION - 2006-2015

However, this quantitative cannot be considered in isolation, since, for judgment on the number of professionals trained, it is necessary to consider that many vacancies offered were not fully met. Although it is not possible to present a cross-reference of the supply and filling of vacancies in all Ifes, since not all the institutions made the list of approved ones available, some situations can be punctuated for reflection. In 2009, the UFPB, for example, offered 40 vacancies for the Libras course at the Taperoá center and, according to the analysis of documents complementary to that year’s selection process, this Ifes had only 22 participants. The same occurred in the municipalities of Cabeceiras and Itaporanga, where the same Ifes offered 40 vacancies at each polo and there were not enough candidates, since there were only 31 and 25 registered respectively. In addition, it is important to consider that many incoming students may not have completed the course, because although this data was not captured in this research, according to information provided by the Ines Academic Registry Division, until July 2014, in the Ines Bilingual Pedagogy course there was a considerable number of students who locked the enrolment or left during that course, as represented in Table 1.

TABLE 1 MOVEMENT OF STUDENTS IN THE INES BILINGUAL PEDAGOGY COURSE - 2006-2014

| EGRESS STUDENTS | STUDENTS IN PROGRESS | STUDENTS WHO LOCKED THE ENROLLMENT | DISMISSED STUDENTS | |

| Deaf | 21 | 85 | 16 | 52 |

| Hearers | 69 | 174 | 21 | 74 |

| Total | 90 | 259 | 37 | 126 |

Source: Ines Academic Registry Division (2014).

In the case of Ines, whose first offer of the Bilingual Pedagogy course dates back to 2006 and considering that since then, according to Chart 4, 609 vacancies were opened, observance of Table 1 shows that, until 2014, that is, after 8 years of the Bilingual Pedagogy course, there were only 90 graduating students. Although this conference has not been extended to all Ifes, due to the difficulty of accessing these data, the alert provoked by these numbers indicates that the total number of vacancies offered or of incoming students may not correspond to the number of graduates of these courses. That said, it is worrying that after a decade of Decree no. 5.626 (BRASIL, 2005), the segment of the Libras teaching in early childhood education and early years of elementary education counted on only that small number of professionals graduated from the Ines, since the course of Bilingual Pedagogy course of the IFG was inaugurated in 2015 and therefore had not yet formed his first class.

It should be noted that the number of vacancies offered for courses of Bilingual Pedagogy course between 2006 and 2015 is already low (639 vacancies), compared to the Libras courses, which presented a total offer of 3,676 vacancies. Therefore, it is possible to infer that higher education policies have proved even less effective in training Libras teachers to work in early childhood education and early years of elementary education. In our view, this picture bare not only the challenges posed to the implementation of higher education policies aimed at the training of Libras teachers, but also the distance from the current school reality in relation to the construction of a society that celebrates and respects the space of Libras as a language, of the deaf individual as bilingual and deafness as a difference.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The data analysis of this research confirmed that, a little more than a decade after the regulation of Libras and the establishment of the professional qualification for the teaching of this linguistic system, the reality still reflects a great lack in the area. There is a shortage of research on institutions, courses and vacancies dedicated to degree in Libras and Bilingual Pedagogy in the country. As explored in this article, the literature has given great focus to the pioneering courses of UFSC and Ines, making invisible the contributions of other Ifes. With this, it is noted that in practice and even in scientific productions, the context of teacher training has been constantly associated only with these two Ifes.22 In addition, in identifying noncompliance with the goals of the Live Without Limit Program (2011-2014), the results also denounce the inefficiency of higher entities to supervise and ensure compliance with the actions of the MEC and the above-mentioned program for the creation of courses aimed at the training of Libras teachers, as provided in art. 11 of Decree n. 5.626 (BRASIL, 2005).

After the temporary acceptance of professionals without the appropriate training for Libras teaching, despite the great contribution of the EaD in the expansion of the number of vacancies offered for the courses of Bilingual Pedagogy and Libras, as well as in the greater territorial reach, the results are still critical for basic education, especially in the area of early childhood education and early years of primary education, which so far have only two graduates in the country (Ines and IFG). There is also the state of Rondônia without any course of Libras or Bilingual Pedagogy offered in the years 2005 to 2015 and places like São Paulo in which the only Ifes to offer the graduation for the teaching of Libras were UFSC in the modality EaD, that formed two groups and is currently no longer available to interested parties, and Ines, which opened its first selection process in 2018, also through the EaD.

From the perspective of the numbers here mentioned, it is not difficult to see how the demand for bilingual education for the deaf still needs to be studied so that we can dimension more accurately the need for professionals trained to meet the presuppositions of bilingual education, including research that evaluates the geo-referencing of the data, that is, that relates where the deaf are and the number of these teachers to attend them, thus capturing the investment needs in training, be it Bilingual Pedagogy or Language Libras. Thus, in sharing our results, we hope to bring to the table broader and more critical contributions and reflections on the feasibility of the deaf rights to bilingual education, as enshrined in our educational legislation.

texto en

texto en