Social movements are marked by relevant educational practices and processes, as they play an important role in the constitution of sociopolitical individuals, aware of their history and epoch, who recognize themselves as belonging to a particular social class, ethnicity and genre. As researchers in the human and social sciences, we are interested in understanding the educational processes that result in the formation of these sociopolitical individuals, due to their important role in social transformations that are necessary to achieve a more just and egalitarian society.

The educational processes that occur within social movements are usually characterized by exchanges of knowledge and practices of popular education between their members. This educational practice results in the internalization of new values that generate differentiated practices, that is, they cause behavioral change concerning social and political issues of the context in which the subjects who experience such educational action are inserted.

When talking about popular education, we refer to what Brandão (2006) conceptualizes as an educational practice concerned with the production of an egalitarian society, committed to the transformation of social structures responsible for the exploitation of the popular classes by the ruling classes. This educational paradigm corresponds to a pedagogical practice that emerges from the context of popular experiences and it is strengthened as popular pedagogy at the service of popular groups, with the purpose of politically organizing the individuals in their struggle against social inequalities. Thus, “popular education is not a variant or extension of school democratization, but else an emancipating conception that seeks to transform the social order and the educational system itself “, according to Carrilo (2013, p. 18).

This article presents the main results of a master’s research1, which aimed to understand what type of knowledge is built through the participation in a social movement and how this educational process occurs. This qualitative research involved semi-structured interviews to obtain life history narratives from six participants of a Brazilian youth social movement: the Levante Popular da Juventude.

This article is organized in three parts: in the first part we bring some contributions about education processes in social movements, placing them in the field of non-formal and informal practices of education. In the second part we describe the methodological path taken to carry out the research, showing the suitability of the life history methodology to deal with the research questions and, in the third part, we present the interviews analyses. This last part is organized in two moments: in the first, we present how the educationalprocessin the social movement was understood by the participants, guided by a dialogical pedagogy that results in transformation and emancipation of the individuals who experience it and, in the second, we present in a more detailed way whichknowledgewas built through the participation experience in this specific social movement. In this last section, excerpts from the interviews will be presented to give evidence to the voices of the subjects who, at the same time, are agents and objects of an educational action that in its entirety and circularity transformed them.

THE EDUCATIONAL DIMENSION OF SOCIAL MOVEMENTS

Education is a broad process that occurs in the most diverse social spaces. As a child we learn the necessary knowledge for life in society within the family, at school and with the community where we live. As adults, learning and knowledge are also acquired in formal educational institutions, but also at work, partying, or shopping in the supermarket, or through any other daily activity.

Canário (2006) uses a well-known metaphor to illustrate the breadth of educational processes. Referring to the image of the moon, which at certain times of the month has part of its figure darkened, the author compares it to the educational processes. The formal educational processes, represented by the luminous side of the moon, are visible to us, but the non-formal and informal ones are also present in social life, although they are not easily recognized or visible, as well as the dark side of that celestial body.

Through this recognition of the breadth of the educational processes, it became possible to realize the relevance and the need to characterize different educational modalities as acontinuumbased on the diversity of levels of formalization of the educational action:formal,non-formalandinformal education.According toFávero (2007), this typology has its origins in the 1960s in the context of “school education crisis”. According to the author, three factors are associated with this crisis. First, the growing demand for adult education after World War II and the inability of school systems to meet this demand satisfactorily. The second factor resulted from the questioning of the role of the school system in the social promotion of the individuals who participate in it. The last factor relates to the importance attached to the training of human resources for a rapidly changing industrial society.

Coombs & Ahmed (1974), considering it analytically useful and making the caveat that there is convergence and interaction between these three levels of education formalization, classified them according to the place, the type of action and the period in which these processes occur. Thus, informal education is the one from which individuals construct knowledge and skills through daily life-long experiences, which are acquired in relationships with friends and family, in reading a book, in a trip… Being a non-systematic experience of education and, although not corresponding to processes with educational intentionality, informal education can be recognized in the educational effects it produces on the individuals. In turn, formal education tends to occur in institutions such as schools and universities and is structured from an educational intentionality that takes shape in specific times, places and modes of pedagogical action, and is usually associated with assessment and certification processes.

Still according toCoombs & Ahmed (1974), non-formal education obeys to an educational intentionality and is systematic and organized, but, unlike formal education, occurs outside the formal education system, is tended to be of voluntary access and it’s directed to specific groups (e.g. age groups; professional groups), and may assume a wide array of forms such as training programs, adult literacy actions, community programs, leisure clubs activities, among other situations.

Gohn (2006) highlights some other aspects of non-formal education. According to the author it comprises:

[…] political learning of the rights of individuals as citizens; training individuals to work through skills learning and/or their potential development; the learning and exercise of practices that enable individuals to organize themselves with communitarian goals, aimed at solving daily collective problems; learning that enables individuals to read the world in order to understand what is going on around them; education developed by the media and in the media, especially electronic media etc.2(GOHN, 2006, p. 28, own translation)

Thus, social movements are potentially an important setting for non-formal and informal education, where moments of debate and reflection about certain social situations favor the construction of theoretical, technical, instrumental and ethical knowledge, as well as a deeper understanding of how our societies are structured and politically organized. Briefly, they are contexts in which those who participate in them potentially develop learning and build knowledge about rights and recognize themselves as subjects of individual and collective rights and duties.

Therefore, we argue that education is a broad process that occurs throughout life hence the experiences that the subjects live provide them with learning. Thus, according to Cavaco (2008), experiences can be understood as a process and as a product. When understood as a process, they refer to a set of events that occur throughout life, according to a timeline that builds the individual. As a product they are related to the ways of being, thinking and doing constituted throughout life.

Pires (2002) points out that for an experience to promote learning, it is necessary that the individual reflects on the lived situation and that this reflection leads him to a self-transformation, that is, the understanding of the experience he lived is an integration of previous experiences, of the values and knowledge that the individual already had, intertwined with the recently lived experience.

METHODOLOGICAL PATH

The rationalist epistemological paradigm has elected formal educational institutions, such as schools and universities, as contexts from where knowledge is widespread and disseminated. In such institutions the elaboration of knowledge follows a specific methodological protocol, based on a rational logic of the pragmatic and utilitarian science, and which gives authority to this knowledge in the perception of the communities in which it is produced, and as a consequence it is legitimized in the larger society where it is widespread.

This research breaks with the rationalist paradigm that considers scientific knowledge as the only one capable of explaining reality. We believe that it is possible to establish a dialogue between scientific and popular knowledge and, through this dialogue, to construct a valid knowledge, because in other spaces, beyond the formal, there are exchanges of knowledge and learning processes.

As the objective of this study was to identify the knowledge that the subjects acquired by participating in a social movement and the way(s) this knowledge was produced throughout their experience, it was felt as necessary to know their life stories. The life trajectories narratives also allow us to understand how the interviewed participants were constituted as persons and which experiences led them to get involved in a social movement. The method we adopted to understand the learning experiences of these subjects within the social movement, based on their own sayings and meanings on these learning processes and products, characterizes the study as qualitative. According to Godoy (1995, p. 58, own translation), a qualitative research:

[…] involves obtaining descriptive data about people, places and interactive processes through the researcher’s direct contact with the studied situation, seeking to understand the phenomena from the perspective of the subjects, that is, the participants of the situation under study.3

In order to obtain the perspective of the individuals, the life story method was used, under the scope of a narrative-biographical approach. Historically, in the Ibero-American context, biographical narratives have had different approaches and interests, but the main one has been:

[…] to recover the historical memory of episodes, characters and events of particular personal and/or social relevance or the other history, the non-official history, of the people, of the minorities, of the losers, the peasant, the silenced or “silent ones”.4(BOLIVAR; DOMINGO, 2006, p. 9, own translation)

Therefore, using the life story method, a relationship is established between the researcher and the participants. This relationship makes it possible to access the reality of the persons to the extent that they relate their lives, reframing them.

In this sense, the research included open-ended interviews conducted with six participants of the Levante Popular da Juventude, namely two men, three women and a transgender woman, all of them residing in the city of João Pessoa - PB, aged between 19 and 30 years, with education levels varying between higher education attendance to master’s degree completion. Participants also have varied family income. The guiding questions of the interviews were combined so that they followed a timeline of the subjects’ lives and the topics of interest of the investigation.

The guiding themes for the interviews were: a) the place where they were born, the constitution of the family and the school/education path, b) the circumstances in which they learned about the movement, c) the reasons that led them to participate in the movement, d) the knowledge that they have built in the militancy and how this construction took place and e ) the main differences that they perceive between the way the learning was built in the movement and in their formal processes of schooling.

The collected data was interpreted through content analysis procedures, which corresponds to:

[…] a set of communication analysis techniques that use systematic and objective procedures to describe a message content.

[...] The intention of content analysis is the inference of knowledge regarding the conditions of production (or eventually reception), an inference that uses indicators (quantitative or not).5(BARDIN, 1997, p. 38, own translation)

Also, according to Campos (2004), content analysis should enable the search for meaning within the collected data, since it allows a multifaceted look at the totality of what was obtained and is therefore widely used in qualitative research.

For this study, the interviews were audio recorded and later transcribed in order to identify key ideas, connections and similarities in the narratives, based on the themes that guided the interview, without losing sight of the completeness of each life story, in order to obtain the indications of the constructed knowledge and its forms of occurrence. By interpreting the similarities between the participants’ narratives, the data was grouped into categories and subcategories. The interviewed participants, who are identified by initials of their names, authorized the recording of the audio and the subsequent dissemination of the research results.

Qualitative Solutions Research Nvivo softwarewas used as an aid in the treatment of qualitative data, as it is

[…] useful in the administration and synthesis of the researcher’s ideas, allowing changes to be made to the documents with which it is working, being possible to add, modify, link and cross data or record ideas in the form ofmemos.6 (GUIZZO; KRZIMINSKI; OLIVEIRA, 2003, p. 9, own translation)

THE LEVANTE POPULAR DA JUVENUDE AS A KNOWLEDGE PRODUCTION SPACE

In a context of worldwide monopolization of food production, which began in the 1980’s (VIEIRA, 2011), a worldwide organization was born later in 1993, which aims to defend sustainable small-scale agriculture and promote social justice and solidarity: the Via Campesina. It is currently made up of 164 organizations from 73 countries on four continents: Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas, thus representing 200 million farmers worldwide (VIA CAMPESINA, 2011).

In Brazil, Via Campesina brings together various movements such as the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra [Landless Rural Workers Movement] (MST), the Movimento de Mulheres Camponesas [Peasant Women Movement[ (MMC), theMovimento dos Atingidos por Barragens [Dam-hit Movement] (MAB) and the Movimento dos Pequenos Agricultores [Small Farmers Movement] (MPA). Besides these, Via Campesina also articulates with other Brazilian social movements that do not have a peasant base but are linked to the international Via Campesina, they are: the Comissão Pastoral da Terra [Pastoral Land Commission] (CPT), the Federação dos Estudantes de Agronomia do Brasil [Federation of Agronomy Students of Brazil] (FEAB) and the Pastoral da Juventude Rural [Rural Youth Ministry[ (PJR). In Via Campesina Brazil, the MST is the land reform commission and the MPA is part of the food sovereignty commission.

It is in this political field of Via Campesina that, from the 1990s onwards, the need to strengthen the youth militancy of the rural movements began to be realized. TheConsulta Popular [Popular Consultation], a leftist movement that advocates a popular project for Brazil, at the time of realization of the National Assembly in Brasilia in the year 2005 established the goal “to organize the youth of the working class and, especially, the youth of urban periphery”7.

It was in the state of Rio Grande do Sul that in 2006 the Levante Popular da Juventude was born, in a youth camp that gathered around 700 people from all over the state of Rio Grande do Sul. At the moment were defined as struggle flags and fields the education, culture, work and leisure, and among these, the democratization of access to the university was chosen as a priority struggle, based on the understanding of the need to change the social composition of the public university through racial and social quotas.

The meetings where the problems of Porto Alegre local youth were discussed began the work of the movement. Six years later, in 2012, in the city of Santa Cruz do Sul, also in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, the Levante Popular da Juventude became a national organization, having as its landmark the 1st National Camp of the Levante Popular da Juventude, under the motto: “Juventude que ousa lutar, constrói o poder popular!” [Youth that dares to fight, builds popular power!] where about 1300 young people from 15 Brazilian states were brought together.

Today, the movement is present in almost all Brazilian states, acting on thepeasant,studentandterritorialfronts and has as a tripod theorganization, educationandstruggle. It has three sectors from which it organizes the struggle:black people;sexual and gender diversity;women. Operating at the national, state and municipal levels, it is based on cells in peripheral neighborhoods and educational institutions, such as high schools and universities. It promotes training actions in national and state camps and various training courses on the Brazilian political and economic reality. It haswebsitesandblogs, as well as Facebook accounts, and in the latter maintains both a national profile and profiles from various states where the movement is present.

THE EDUCATIONAL PRACTICE IN LPJ: APPROACHES TO POPULAR EDUCATION

The educational experience of participating in a social movement differs from that experienced in formal educational institutions, hence we’re talking about knowledge constructed in the course of life and through the “reading, interpretation and assimilation of facts” experienced by individuals in the experience of the movement (GOHN, 1999, p. 98). We dedicate this topic to bring some of the reflections produced about the discourses on how the educational process took place in the studied social movement, bringing some of the principles that underlie this process and the ways it occurs.

The vindication processes experienced in social movements, especially those involving the search for social transformation, citizens’ rights and their maintenance, lead participants to read daily life and social situations, to understand the discourses of power and the intentionality of actions of the leaders of the sectors that constitute society.

Thus, the first characteristic to which we want to draw attention is that this educational practice isemancipating, since it is configured as a political education carried out with and for the popular classes, aiming to enable individuals to be actors in social transformation. Therefore, it approximates the theoretical- -methodological conception of popular education, which:

[…] it is part of the tradition of Western and Latin American critical thinking, with the singularity of having its own field of action (multiple spaces of resistance, school and non-school) from an alternative political option that dialogues with other critical paradigms and understands the pedagogical dimension as a field of knowledge and power devices.8 (CARRILLO, 2013, p.18, own translation)

Other movements and currents, such as popular feminism, popular environmentalism, Liberation Theology, among others, maintain a relationship with Popular Education once they criticize the prevailing social order and propose an alternative model to the current one, through the formation of social actors by means of a pedagogy that is problematizing , transformative and dialogical.

In this sense,Carrillo (2013) presents three aspects of the emancipating paradigm of Popular Education. The first of these concerns the gnoseological dimension, i.e., a critical reading of reality. The second is presented as apolitical dimension, and consists of an alternative position to this reality, and the third concerns apractical dimensionof social transformation based on individual and collective actions. To form critical and emancipating thoughts and subjectivities, it is necessary that pedagogical practice incorporates strategies and criteria to achieve this goal and does not merely focus on the dissemination of critical content.

These processes of reading social reality and having a political position towards it can be seen in the following sayings of the participants in this research:

[…] the struggle is necessary, it’s not just something we choose, at least in my position I can choose to fight or not to fight, other people are fighting for their life, for their existence here. So this impact no book could tell me.9 (YL, 2017)

I felt very much that need for change, after I started to see that things are put that way, but also, that there is ... somehow, we can transform.10 (VP, 2017)

From the reading of these two excerpts we can see that, as described byCarrillo (2013), for these two participants the individual process of struggle for social transformation began with the critical reading of reality, which led these individuals to perceive the situation of injustice and unequal constitution of society to later position themselves politically and find in the social movement a real possibility of transformation and change.

Another two aspects we want to draw attention to about the educational practice developed in this social movement is that knowledge isbuilt collectivelythroughdialogue. The participants’ testimonies demonstrate their reflections on the construction of knowledge in the social movement and the importance given to the knowledge that each one brings to the construction of the movement and the organization of the struggle.

We bring elements that would not be present if there were no people from these places that we want to go to, like, the periphery, high schools, the university, we need everyone thinking in order to build. And I think the historical process, the contribute of each person is essential, isn’t it so?! The contribute that I have as a guy from the periphery, who came from the countryside, is a fundamental contribute, but it is not a contribute that overlaps other of a person who has a different experience from me, I don’t know, people that is more of the middle class, thus, my contribute does not overlap the contribute that this person brings. I think both contributes are very important for us to be able to build this new society.11(VP, 2017)

In the statement it is possible to see that this participant understands the importance of the different life histories and experiences of the movement’s members, and how this diversity is important so that, within the movement, knowledge is constructed collectively, based on the dialogue of different historicities in what concerns to different experiences regarding gender, social class , age group, among other factors.

All human beings have knowledge generated from the practices they develop in daily life, that is, knowledge elaborated through the experiences lived in the world they inhabit. This knowledge that each human being has, whether from the periphery, the middle class, life in the countryside or backlands, occupies an important place in the educational process if we consider that the educational relationship is a mediation (MEJÍA, 2013).

Thus, the daily life in the movement provides relevant educational experiences both through intentional actions, designed and thought by the leaders, as well as through the experience and coexistence in the movement itself:

I think that besides the theoretical formation, which in the Levante we value so much because of the formation of the militants, I think that the social struggle is also a space that forms, you know. While many spaces deform you, the struggle forms. So, to find out how you do political articulation, how to have the courage to speak in public or in different spaces, know how to behave, all this I learned in the daily struggle. Arriving in the union and bargaining a financial struggle, making a political articulation with a different political force, having the feeling to realize when it is time and to put what in discussion, all these are the militant challenges that made me grow. And besides that, going back to the more academic and professional issue, I study the regional integration in Latin America, Venezuela, the ALBA (Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America), all this I would not have discovered, even for my research of the master’s degree, if it wasn’t for my militancy contact.12(MD, 2017)

The theoretical formation to which this participant refers mainly occurs in the camps and training courses, as well as the one carried out in the moments of study and debate within the sectors, that is, they are moments intentionally destined to the study, debate and therefore deepening of certain themes and contents, which thus correspond tointentionallearning practices. But there are also these educational processes which are subsumed in the expression “the struggle forms”. Referring to these “everyday” educational processes that occur in problem solving or more practical demands, there is the recognition of educational effects, of informallearning processes. MD ends the saying by referring to how these learning built in the movement complemented his formal education and contributed to academic achievement and professional work.

THE LEVANTE POPULAR DA JUVENTUDE AS A SPACE FOR KNOWLEDGE CONSTRUCTION

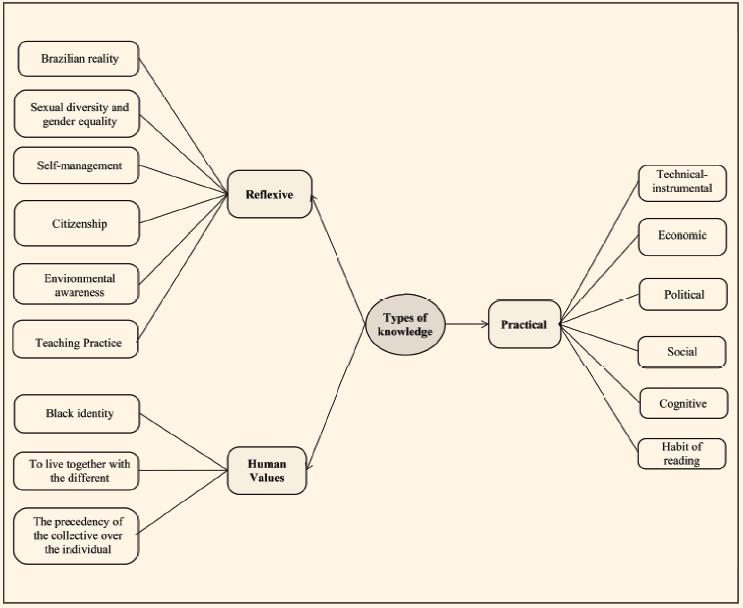

From the qualitative analysis of the interviews the knowledge built through the participation in the social movement was grouped into three large categories: thereflexiveknowledge, thepracticalknowledge and thevalues related knowledge, as can be better understood in the map below:

Source: Own elaboration, based on research data (LUCENA, 2017).

Thereflexiveknowledge is the one that allow individuals to problematize the ways of being in society, and is therefore a knowledge that is strongly associated with the personal lives of each of the interviewed subjects, allowing them to even think about personal issues, but they also make it possible to equate these issues as broader social problems. This knowledge also has a practical dimension because it results in behavioral changes when these questions were seen from the individual perspective, from the participant himself, but also from the perspective of the collective common good.

Thus, within this knowledge is the one related to the perception thatwe live in a society with great inequalities and injustices.This knowledge is usually built prior to entering the movement and is deepened later through the educational processes that take place within it. Even if in the first moment this perception was not accompanied by the problematization of the origins of such injustices and social inequalities, this perception was accompanied by the conviction that it is possible and necessary to construct another reality through a collective struggle. This belief led participants to wish to join the movement, as can be seen from the following testimony:

I felt very much that need for change, after I started to see that things are put in a way, but also, that there is ... somehow we can transform […] From the moment you see other historical experiences of change in the very structure of the State, even revolutionary processes, you start believing it is possible, isn’t it?! And you feel the need to somehow contribute to this change. So when it is presented to you that if you are organized you will be able to contribute much more than if you are doing it all alone, you feel the need to participate in a movement, a collective, where you collectively think of a new society.13 (VP, 2017)

This narrative illustrates a process of awareness raising by means of a critical reading of reality, namely about the situation of social injustice in Brazilian society, and how this individual positioned himself in front of this reality and perceived in the social movement a possibility of transformation through the collective struggle.

Other important insights that the testimony highlights as learning during participation in the movement concerns two of the themes from which the movement organizes the struggle:sexual diversityandgender equality. In the following saying, the participant describes how the struggle for gender equality is perceived within the movement:

[...] feminism, it is not only a struggle within the Levante, it is a principle. [...] it is present in everything in the Levante, it is not just a struggle, it is an internal and external struggle. We try for example to have gender parity, for instance if we are going to do an activity, and people from Levante are called to represent Levante in a place to make a speech, we take care to have parity , i.e., parity also in our internal process.. If there is going to be needed a speaker or a coordinator for a job, then there will be a man and a woman. If there is a cell to mobilize, we will do everything possible to be a man and a woman, because the fight against machismo begins within the movement. Because men and we women always need to educate ourselves against sexism, because society is sexist. And we still carry these things with us. We are not totally free, neither boys nor girls.14 (RF, 2017)

As we can see from the above sentence, the social change that is intended to be promoted, namely with regard to gender inequality, involves actions within the movement itself, seeking parity in the participation that representatives will have in the representation of the movement, in discussions, among other actions.

In the process of participation in the movement, another knowledge emerges:self-management,acquired through experiential learning. CB reports the trip to a national camp, which brought people from the state of Paraíba to Rio Grande do Sul. According to the deponent:

It was going to be a self-managed camp that we would build. So, the teams would also happen there at the camp, so that things could go, because they were students, they were young people, organizing [...] And there, the camp was like this: two states would take care of the food, in a specific day they had to cook the lunch, there were leaders, the people who were the references, but the states were responsible for helping with food, cutting, washing dishes, doing all this, others were responsible for safety…15 (CB, 2017)

The word self-management (self: being inward andmanagement: administration, governance, direction) conveys the sense of seeking change within oneself. In this sense, self-management when in the business or educational context, intends to lead the other to follow the path from dependence to autonomy.Moreira (2012) adds another meaning to what may be defined as self-management, which presupposes a work of co-responsibility with the other, even if the latter is autonomous, thus giving an idea of collective responsibility, as can be seen in the testimony about the act of care and responsibility that participants had in activities or tasks that would benefit the whole community.

The third knowledge associated with what we call reflexive knowledge concerns theright to the city, which has been one of the most important struggles waged by the movement since its inception. This struggle can be seen most clearly in the claims against the increase in bus tickets prices, the only means of public transportation in most Brazilian cities. In the saying of VP it is possible to see how the knowledge on this emerged from the participation in the movement:

[…] one question that I am very keen to delve into is the question of the right to the city. And on the issue of exile of the periphery. The right of people who live in the periphery ... the periphery is very distant from those centers where culture, where leisure takes place and so on…is distant. And the access to that place is very precarious, you know. We made that bus debate, and it’s related to this right-to-city thing, because the ticket price increases every year, and the buses get worse and worse. And now there’s a bus stop inspector who won’t let people skip the wheel or get in from behind.16(VP, 2017)

The vindications against the increase in bus tickets prices made this participant reflect on the right of people who live in the periphery to have access to the city center, where the main cultural programs,shows, popular parties, street shows, cinemas, theaters and other events take place. According to the saying, the participant developed the understanding that the struggle for access to public transport is also a struggle for access to culture.

The process of urbanization that Brazil and other Latin American countries have undergone since the second decade of the twentieth century caused the Brazilian urban population to grow from 26.3% in 1940 to 81.2% in 2000, a percentage that corresponds to roughly 138 million inhabitants. However, the way this urbanization took place culminated in the “exile” of the populations of the periphery (MARICATO, 2000). In addition to the problems of access to the city center, the periphery is also limited by:

Homogeneously poor territorial concentration (or spatial segregation), idleness and absence of cultural and sporting activities, lack of social and environmental regulation, urban precariousness, restricted mobility to the neighborhood, and, besides all these characteristics, increasing unemployment [...]17 (MARICATO, 2000, p. 29, own translation)

The issues surrounding theexile of the periphery go beyond the deprivation of the right to the city, as it implies not only the denial of access to culture, but above all the denial of social and economic rights.

The fourth knowledge resulting from experiential learning mentioned in the participants’ narratives is related to the environmenttheme. In her saying, CB tells us how the involvement in the activities and demands of the movement made her problematize global and locally the relationship of humanity with nature that derives from production relations and systems:

Cabedelo is a very small town, a peninsula, is surrounded ... on one side is the sea and on the other side is the river, has a mangrove, and is a port city here also from Paraíba. In this city products of various genres arrive and one of these products was the petcoque [petcoke], which is a black powder, the garbage or sludge, a byproduct that remains of oil. It is used a lot as fuel for the industry, it is a very cheap product, it comes from Venezuela, I don’t know if from other countries too, it comes here to Brazil to be used in the industry, to burn, and it is a highly polluting product, both in the sense of transport, polluting the air, as well as polluting the water, and what happens? Wherever this product arrives, its transportation is not suitable, the product is transported on carts only covered by canvas, it dissipates a lot in the air ... it is also stored in an inappropriate place, I don’t remember the name now, if it’s estuary, but practically on the mangrove, in the open. With the action of the wind it pollutes the mangrove and harms all species that are there, doesn’t it? Consequently, it pollutes the water and the water springs.18(CB, 2017)

This participant, along with some associations, such as the Cabedelense Association for Citizenship - ACICA, students, teachers and social movements, began to mobilize as a front and to demand from the public authorities’ solutions to this environmental problem, which provided learning about the environmental theme.

The theme of the environment is part of a critical reading of reality, as it involves the exploitation of labor and the destructive consumption of natural resources and, therefore, is related to a perverse logic of production and relationship with nature, in which, in the words of Gadotti (2001, p. 81), “we moved from the mode of production to the mode of destruction”.

Thus, there is relevance in making an articulation between Popular Education and Environmental Education, because modernity brought a distancing in the relations of men and women with each other and with nature, which also affected daily relations, training and education, ranking different forms of knowledge (FIGUEIREDO, 2013).

The sixth knowledge acquired in participating in the social movement, related toteaching practice skills, which was mentioned by those participants who are professionals of education, especially teachers of basic education. The teacher training is a continuous process, that is, does not end upon completion of the academic education, but extends throughout life and in different areas of life, and that’s how the experience of participating in the movement brought contributions for the teaching practice of these participants. According to the RF testimony:

I think the biggest contribution is in my training. Today I am a teacher, and what I work in the classroom, besides the extension project which was another great professional contribution, which was to have participated in a popular extension project of Popular Education, which also gave me a way in relation to the method, the way of doing things, the Levante gave me content [...]

I go to the classroom today and I will work, for example, music with the children, then I will work a song that we used to sing a lot, “Negro Nagô”. Through it I will teach Portuguese language, and I will work about racism, I will work the history of what is slavery, the slavery period and I will teach about resistance. If I wasn’t in the Levante I would be sensitive because I was in a field that was giving me that sensitivity to understand a lot, but I became even more sensitive to perceive things.19 (RF, 2017)

RF attributes “sensitivity” to address some issues in the classroom, especially those related to identity, due to the experience she has had in university community extension programs, but also believes that such sensitivity has been enhanced as a result of her participation in the social movement, since as one of the struggle sectors of the movement is theNegros e Negras, ,within which the issues referring to the history of the black people in Brazil are very debated within the movement, and that experience provided her with a range of learning that enabled the development of such content in the classroom in a more critical and in-depth way.

Such positioning when addressing themes related to the history of black people in Brazil in association with the current situation can contribute to the emancipation of the students, since 56.4% of the Brazilian population declares themselves to be black (INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA - IBGE , 2015), and the classes mainly in the public school are mostly composed of black people. Thus, it is indispensable to work on themes that strengthen the identity, history and culture of this ethnic group.

In addition to those mentioned earlier, participants also refer to educational processes that resulted in learning of what we callpractical knowledge.These types of knowledge consist in obtaining or developing skills resulting from activities performed in the daily organization of the movement. Based on what is described byGohn (2011), 12 types of learning can occur in the struggles of social movements: practical, theoretical, instrumental technical, political, cultural, linguistic, economic, symbolic, social, cognitive, reflective and ethical.

Some of the roles that participants play in the movement provide the basis for affirming the development of such knowledge:

My task here in the state is to pep the territorial front and also some more operational tasks, for instance if you need a bus to make a trip ... It’s some operational departments, executive departments that we have.20 (VP, 2017)

I am part of the Levante coordination at regional level and within the state coordination I am part of the finance collective. So, we think about the movement as a whole and I specifically think about the finances and help to organize.21 (YL, 2017)

Systematization also, i.e., trying to do reporting, these things I did too. Quite a lot, I did a lot of rapporteurship.22(RF, 2017)

These activities led to the construction oftechnical-instrumental and economic knowledge. Technical-instrumental knowledge is related to the understanding of how organizations and institutions work, the procedures, bureaucracy, roles… and economic knowledge, as the name proposes, relates to knowledge about finance.

Thus, according to the first testimony, the activity of providing a bus, causes the participant to mobilize a set of knowledge according to an organizational logic. For example, if the request for transportation is made within the movement itself, it has to go to the finance sector to access the money needed to fulfill such a request, but if, on the other hand, the request is made to some public agency, as the city hall or secretary of state, a bureaucratic path must also be covered.

The second deponent, a law graduate, also plays a role in the area of finance. To this end, YL also needed to develop knowledge related to this function. Likewise, RF also needed to develop the necessary knowledge to perform the reporting of the movement actions. We see examples of other practical knowledge in CB’s account that tells how she uses the knowledge acquired in the movement in her workers union practice:

Today, I am a teacher and a syndicalist. I’m in the union milieu, and there I can use many of the things I learned during my time at the Levante Popular da Juventude in my area. Of course, I keep studying, my emphasis today is education, the things that involve my profession, but I take many of the principles of the Levante there, don’t I? This thing of studying, of training, of organizing ourselves, the fact that I am in the union, is a way of organizing myself, and the struggles that we conducted and will be conducting from now on, increasingly against this government. [...]

I was always a person who had difficulties speaking in public, I am not one of the most talking persons, who has very good orality, but today I speak in public, more easily. [...] So I participated in many formations during these times, organized by the Levante and other organizations that are from the same popular field and then today I have a little more freedom, I can debate about agendas that before I would not know, political agendas, education guidelines, minimally about health care, that was the result of that.23 (CB, 2017)

Through this testimony it is possible to observe four types of learning resulting from acting in the social movement:political, social, cognitiveandpractical learning.According toGohn (2011), political learning is related to knowledge about the rights and the professional category to which each worker belongs; the social learning, in turn, is knowledge related to public speaking and about behaviors of different groups in different contexts, among other knowledge, and cognitive knowledge learning is related to those contents, problems or themes that concern ourselves, acquired in the different spaces of participation. This knowledge concerns the construction of knowledge about the performance in a social movement and its organization. In the action of this individual as a syndicalist, she applies the practical knowledge that she claims to have acquired by participating in the movement.

The third set of knowledge acquired in participating in the social movement was identified as related tohuman values, as it led individuals to reflect on themselves and about being in society. According to Schwartz (2001), human values refer to desirable goals that transcend specific situations and they may vary in importance, but overall guide the life of a person or other social entity. Gouveia et. al. (2003), stress the idea that research on the theme usually understand values as guidelines for human action, relating them to various individual behaviors and / or attitudes.

Given this, and according to the narratives, as the movement studied is a space for reflection and action in search of social transformation, aspects related to human values are addressed in the participation of the subjects in this organization. This occurs through the experienced, reflective and practical approach of principles that are intertwined with the motivations and evaluative judgments about themselves and the others, about collectivities, directing both individual and collective actions that will have social reflexes. The first of these values concernsblack identity:

And even for me to recognize myself as a black person, you know, it was a very slow process. Nowadays my hair is so big, but old, I used to cut my hair like that before (picks it up to show what it was like before and how it is now), you know, a year ago I’ve been letting it grow, you know. It’s been hard, you’re recognizing yourself even while black.24(VP, 2017)

From the problematization of issues related to racism, it was possible for this deponent to review the social representation of the black from a historically constructed view of “being black” and that this view was reconstructed for this participant now taking positive aspects.

This reconstruction was expressed by him, above all, by the recharacterization of the use of his hair, such an important element in the representation of the social body and language, because the hair represents not only individual and biological characteristics , but also the identification with a certain ethnic group and a culture (GOMES, 2006).

The second type of knowledge regarding human values was designated as to live together with who is different, because the testimonies led us to realize that the experience of participation in the movement allowed young people to review values related to racism, class, gender and sexuality, thus , the discussion on these themes is related to “identity and difference“.

Theidentityis affirmed in between the identification of what one is and the denial of thedifferent, i.e., of what one is not. Thus, when one say “I am a man”, “I am white”, “I am straight”, “I am a Christian”, is affirming oneself through the difference of the other who is “woman”, “black”, “homosexual”, “Muslim”, for example. These binary positions such as: male/female, white/black, heterosexual/homosexual, Christian/Muslim, always include a positive value due to the negativity of the counterpart. To problematize the conveniences in each of these dichotomies implies to perceive the identity and the difference from the power relations that lie underneath them (SILVA, 2000).

The following testimony describes how the experiences lived in the movement allowed a participant to make self-reflections regarding his way of relating with “the different”, especially those differences related to sexual orientation, socioeconomic origin and skin color:

[...] what struck me most about the Levante was the contact with people totally different from my reality. So that, in the beginning, it was very difficult for me, it was so much for me to assimilate; other social classes, other ways ... people are very diverse within the Levante. So, me, this white middle-class boy, with that little life ... and then I started to coexist ... not that I didn’t lived with others before, but I say like that, I don’t know. This coexistence awakened me to things, to my defects, to my addictions, to my prejudices, which started to break down. Things I even thought I had broken before. This thing of prejudice, we have in the Levante the concerns about gender, sexual diversity, race issues. In my mind, that was already solved for me, in theory, because I could already understand the LGBTphobia and the machismo thing, and in practice, when I started to live with these people, it was when I really discovered that there were things that were much deeper in my conscience. And that changed because of my action in the Levante. And in cause of that pedagogical action from other people. Not only do other people come to tell me, “Look, you’re doing this or that”, not only this, this too, but also myself seeing that and saying “Wow, I can’t believe I still thought this or did this, I had never noticed!”, finally, it has changed a lot in my life.25 (YL, 2017)

According to the testimony, it is possible to see that YL believed that before engaging in the social movement, his personal questions regarding identities other than his “were resolved”, but through situations of confrontation with other participants and through self-reflection he came to the conclusion that his way of thinking and living with one another did not agree with what he considered to be ideal or desirable, and so there was a change in behavior.

Through this narrative it is also possible to realize that the educational experience lived in the movement is able to modify the way of relating with the other, through an education that is reflexive and problematizing which goes beyond the principles of respect and tolerance, but reaches above all an analysis of the place of power in social relations.

The third set of knowledge related to human values concerns theprecedency of the collective over the individualand is associated with the concept of solidarity, intrinsic characteristic of a social movement. Etymologically the word solidarity comes from the Latin wordsolidus, which brings us to the field of geometry and to bodies in three dimensions.Costa (2009) adds to this etymological feature some others, such as ethics, commitment to another independent social being, relaxed collaboration based on social sensitivity and generosity.

Within social movements, solidarity is the articulation between those involved, through common referential base experiences, values and ideologies built by the group. The group trajectory is constructed through individual trajectories, which does not mean that internally the movement is a harmonious and homogeneous space, that there are no differences inside (GOHN, 2002), as can be seen from the following participant:

[...] this thing of understanding that when you are building something collectively, collective decisions are superior to our own conscience, so, in certain moments it happened, “Oh, I don’t think this attitude, this action, this response that we will give is the most correct for the moment”, but also understanding that this was built collectively and that I will not be boycotting. Ah, I won’t just admit my position because we are in a space to build it collectively and we need to understand that the collective constructions surpass the individual ones. I think that’s like this.26(YL, 2017)

Solidarity is expressed by the movement in the way it presents itself in public, in the speech they manifest, in the practices they articulate in external events, which makes them create in the social imagination a figure of oneness, a vision of wholeness. Thus, solidarity “also means taking up the defense of the interests and rights of others, even if their own interests, individually considered, may not be, at least immediately, at stake” (MEDINA, 2008, p. 346).

From the testimonies, as the following, it is possible to realize that there is a concern with the perpetuation of the values seen in the participation of the movement, as well as other results produced and experienced in this participation:

I think I have learned many values that govern my life today, humility, the spirit of sacrifice, of loving each other even with differences, and of realizing that what I am doing now goes beyond what is set, to other generations, for people who do not know me but are people like me, it’s indeed a learning for life.27 (MD, 2017)

In this way, solidarity goes beyond compassionate action and altruism towards the other or society, marking the collective from the individual, as a form of constancy in which the whole and the parts preserve each other and appears to be an essential value., from the perspective of the participants of the LPJ, for building individual and socially fairer human relationships.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

With its origins in the Via Campesina, which has been struggling against the monopoly of food production in the world, the social movement studied, as well as the Via, has among its objectives the promotion of social justice and solidarity. But, in addition to problematizing the relationship of workers with labor in a context of neoliberal production, the Levante Popular da Juventude has also included in its struggle’s other social conflicts concerning identity issues.

Thus, it is possible to identify a double character of the field where the struggles of this movement take place. The first of these is thesocio-political ,manifest in the actions of the sectors through which the movement organizes the struggle: black people; sexual and gender diversity; women, and which is related to the constitution of the movement identity and to cultural resistance, which allows us to study it from the theory of New Social Movements, through the works of Alain Touraine (1965), Alberto Melucci (1976) and ClausOffe (1983), for example.

The second character is thepolitical-economic one , which is based on the conflicts of interest originating from class struggles, which allows us to understand it using the Marxist theory of analysis of the new social movements, expressed in the studies of JordiBorja (1975), ManuelCastells (1974), Eric Hobsbawn (1970) and GeorgeRudé (1982), for example. It is important to note, however, that the struggles of those groups - black people, women and LGBT community -, are not inseparable from the class struggle, since Brazilian society is governed by a capitalist-patriarchal-racist system.

The path taken in the struggle for reality transformation is rich in the construction of knowledge. In the organization of the studied social movement, it is possible to notice that there is a wideintentionaleducation work of the individuals, through study, reflection and problematization of the themes that emerge from an analytical investigation of the Brazilian reality. But there is also thatunintentionalconstruction of knowledge, which results from the experience of participation itself, as the result of discussions, from listening the story or life history of the other, from the preparation for the participation in a public act, among other activities.

But, naturally, the possible paths for social movements study are not exhausted in what was addressed in this study. It was possible to identify other possible directions for further research. One of these directions is the deepening of studies on how participation in these collectivities reaches the human values that the individuals bring with them and how these values change during the struggle for social transformation. In the studied movement it was possible to identify that the praxis that involves the valuation of life experiences, the admission and recognition of the importance of black identity, gender equality, solidarity and relevance of acting and thinking collectively, modified individual and collective postures of the subjects who experienced such an educational practice. To further research on this theme is significant to understand how educational experiences in social movements and other informal and non-formal spaces of education relate to human values.

texto em

texto em