Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 0100-1574versión On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.50 no.177 São Paulo jul./sept 2020 Epub 20-Oct-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/198053146808

ISSUE IN FOCUS

HOSPITALITY AND INTEGRATION IN THE MAKING OF THE COMMON IN SCHOOL SOCIABILITY1

IUniversidade de Évora, Évora, Portugal; josemenator@gmail.com

IIUniversidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal; lcgouveia86@gmail.com

IIIUniversidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal; dbeirante@gmail.com

This article is based on data collected from a research project centred on school sociability, aiming, through a sociology of engagements and commonalities, to shed light on other angles of school justice and the making of the common in the school territory. Specifically, a technique termed scenario survey is mobilized, in which, based on a dilemmatic narrative, the intention is to access the moral meanings evidenced by the inquired students. We analysed particularly their inquietude around respect, recognition, hospitality and decency brought up by these actors in their interactions and critical judgments - judgments that transcend interpretations merely based on the formal governing devices of actor’s conduct in the school space.

Key words: SOCIABILITY; JUSTICE; SCHOOLS; STUDENTS

O presente artigo parte de dados recolhidos de uma pesquisa centrada nas sociabilidades escolares, pretendendo-se, na esteira de uma sociologia dos envolvimentos e comunalidades, trazer à luz outros ângulos da justiça escolar e do fazer o comum na escola. É, concretamente, mobilizada uma técnica designada por questionário por cenários, em que, a partir de uma narrativa de carácter dilemático, pretende-se aceder aos sentidos morais evidenciados por alunos inquiridos. Analisamos em particular as inquietações em torno do respeito, reconhecimento, hospitalidade e decência trazidas à colação por esses atores nas interações e nos juízos críticos produzidos - juízos esses que transcendem leituras meramente feitas a partir dos dispositivos formais reguladores das condutas no espaço escolar.

Palavras-Chave: SOCIABILIDADE; JUSTIÇA; ESCOLAS; ALUNOS

El presente artículo parte de los datos recogidos de una pesquisa centrada en las sociabilidades escolares, pretendiéndose, en la huella de una sociología de las participaciones y comunidades, traer a la luz otros ángulos de la justicia escolar y del quehacer habitual en la escuela. Es, concretamente, movilizada una técnica designada por cuestionario por situaciones, en que, a partir de una narrativa de carácter dilemático, se pretende acceder a los sentidos morales evidenciados por alumnos inquiridos. Analizamos en particular las preocupaciones en torno del respeto, reconocimiento, hospitalidad y decencia planteadas por esos actores en las interacciones y en los juicios críticos producidos - juicios esos que transcienden lecturas meramente hechas a partir de los dispositivos formales reguladores de las conductas en el espacio escolar.

Palabras-clave: SOCIABILIDAD; JUSTICIA; ESCUELAS; ALUMNOS

Cet article part des données d’une recherche axée sur les sociabilités scolaires. Dans le sillage d’une sociologie des engagements et des communalités, il s’agit de mettre en lumière d’autres aspects de la justice scolaire et du faire commun en milieu scolaire. Concrètement, à l’aide d’une technique denommée questionnaire par scénarios, à partir d’un récit à caractère dilemmatique, on vise à accéder aux significations morales mises en évidence par les étudiants interrogés. Nous analysons en particulier les préoccupations relatives au respect, à la reconnaissance, à l’hospitalité et à la décence soulevées par ces acteurs dans leurs interactions et leurs jugements critiques, jugements transcendant les lectures qui sont faites uniquement à partir des dispositifs formels régissant les conduites dans l’espace scolaire.

Key words: SOCIABILITÉ; JUSTICE; ÉCOLES; ÉLÈVES

ON SCHOOL SOCIABILITY THROUGH THE SCOPE OF STUDENT’S CRITICAL OPERATIONS

Entering any public school has been a fruitful source of multiple experiences. It began in 2004 within a research project devised to sociologically discuss how citizenship education made its entrance into school by way of public policies and actions intended to guide the schooling processes.

In fact, in the late 90s of the last century, the political leaders of Portugal’s Ministry of Education expressed their concern on the lack of interest among adolescents and young people for political issues.2 The knowledge of the extent of this detachment is given to them by the results of innumerable surveys applied in the country or by several European Union’s institutions at the time, aiming to have a notion as close as possible to the reality of the type of attachment or detachment of adolescents and young people from the political phenomenon. The greatest concern of those in charge of these observation techniques and their use is to assess, through their results, the degree of quality of democracy. And, according to those results, that degree is not a very positive one. A wide range of young people and adolescents are abstaining because they do not participate, through the vote, in electoral acts; among those who are already working at the time, a high percentage are not unionised; many are unaware of public causes, etc. Namely, the political involvement of the younger generations shows a lack of commitment to political activity - in terms of active and frequent involvement.

In the face of this general concern, since 2004, our aim has been seeking to discover the grammar of reasons for this disinterest turned into a public problem. According to data brought by political sociology at the time, “sufficient empirical evidence on the relationship of young people with politics” is shown (RESENDE; DIONÍSIO, 2005, p. 673).3 However, the formal departure of adolescents and young people from political issues is counterbalanced by other unconventional engagements, that is, engagements not formatted according to the canons of official democratic participation. It is this other side of political involvement that has been our finding through successive immersions in school spaces over the past 15 years.

The mentioned research angle, resignified in the shape of a change in the meanings of adolescents and young people’s way of political engagement, has forced us to widen the space of public action of these beings. They are no longer bounded by an institutional definition of democratic implication, like, for example, the degrees of electoral abstention or political militancy in parties or other organizations constituted for that purpose, to consider their connection to public action through inorganic movements (sometimes more episodic) or their involvement in more recent public causes - such as the defence of animals, the environment, in favour of life or the decriminalization of abortion, for or against homosexual marriage, in favour or against adoption by same-sex couples, etc.

It has been through this scope that we have been observing school sociability. In order to test, from the beginning of the research, what the best insight is, as is to say what is the best sociological outlook to capture the active modalities of adolescents and young people at school in everything that concerns their attachments to the discussions on issues of public nature, and the most appropriate tread (because it is the most promising one), it has been analysed how school sociability is made, either among peers, or among the statutory figures categorised as students, or between the latter and their teachers. It is through school sociability that has been questioned how political socialization is operated in the educational institutions where secondary education takes place.

Bringing critical operations to light is to give students a voice but in their figures of adolescents and young people. This has been another innovation in our studies. When bringing to the centre of sociological inquiries their judgments on issues related to situations, moments, occurrences that students consider to be unfair, that is, matters that they manifest in a visible or in a whistleblowing way (the school lashing produced by the rat - the invisible informer), the sociability arrangements have been constituted as the best way to understand the meanings of these beings’ critical operations, who, in the transition from Basic to Secondary School, are going through the temporal arc that goes from the end of adolescence to the beginning of the young age.

It is precisely at this age transition that the passage to the last learning cycle occurs within schooling, determined as mandatory by the State. That is why this change - of age and schooling cycle - has been an interesting moment to explore the meanings of their critical faculties regarding problems that students announce to us, both in the context of exploratory conversations and in semi-directive interviews they have provided to us. In these common interactions, which go beyond the simple moments of formal or informal exchange of words, our observations capture individual or collective action modalities that are supported by a set of equipment that students constantly manipulate at school: cell phones, laptops and other similar objects that are, in a sense, artifacts that mediate, or even interfere, with their sociability among peers and with adults - whether they are teachers, education auxiliaries, psychologists, youth workers or other cultural mediators who work with them at school. It is through these artifacts skillfully used by students that teachers have been signalling the entrance of cultural industries in schools, expressing that their arrival produces acute tensions between curricular learning and the knowledge absorbed from internet platforms. And it has been through the social uses of these artifacts that we have verified its importance in their sociable involvements (sometimes tense or even conflicting) both with colleagues and those who they qualify as friends or with older beings who present themselves with another status within school walls.

What these beings, in this age transition and learning cycle, have been able to do in terms of school commonality with multiple voices has been our guideline in the consecutive researches carried out. And if at the first stage the purpose is to apprehend how political socialization is operated through the public action of a giving school time specifically dedicated to citizenship education, in subsequent stages, the research subjects are based on other anchors left open by these first endeavours into school territories. In fact, in the first itinerary research, the guiding needle of our questioning is limited mainly to the qualifying work that is demanded by the political socialization conceived by the judgement of the teachers with whom we developed the theme of the entry of citizenship education in the secondary school curriculum at the beginning of the new millennium (from the late 1990s to the early years of the 2000s). What is curious is that, when examining with the teachers how they operate, through teaching, but also through their coexistence with the students, the problem of citizenship education at school, they raise other problems that are problematised with the support on other axes that densify the analysis of what the questioning on the formulation of a citizen education along an increasingly long compulsory schooling brings.

The axes that they raise in their inquiries about the difficulties and challenges in mobilising students to discuss problems that they consider to be public make us shift our attention to other dilemmas and disputes that students summon, such as school and relational inequalities, humiliation issues and their judgments on other injustices committed during their passage through compulsory schooling. Thus, this broadening of scope greatly densifies the analysis of the arts of making the common in the plural in Portuguese state schools.

THE COMMON IN THE PLURAL IN SCHOOL SOCIABILITY BETWEEN EQUAL AND UNEQUAL BEINGS4

School institution has been, over the decades, a central subject of sociological analysis. Among the (profuse) production developed and shaped by different theoretical and methodological frameworks, topics related to its functioning stand out as a privileged angle, focusing particularly on school performance inequalities produced within it - and their consequences in terms of social inequalities (THÉVENOT, 2011). In this set of questionings that guide the inquiries on the suitability of educational policies concerning the access to schooling, combating school inequalities and fulfilling the project of a democratic school, the analysis on the functioning of educational systems is conducted from the perspective of school meritocracy and equal opportunities as central principles of justice for the accomplishment of the goal of a fair school (DUBET, 2004; SCHILLING; ANGELUCCI, 2016).

However, an examination of the judgments produced by actors in the school space allows us to account for different perceptions of injustice that emerge on the critical operations that these actors produce regarding the functioning of the educational system and the project to build a democratic school. Namely, an ethnographic immersion, focusing on the moral vocabulary underlying these critical operations, allows bringing to light different principles of justice evoked from problems and questionings raised by experiences that result from school sociability and that trigger feelings of injustice (RESENDE, 2010; RESENDE; GOUVEIA, 2013; BOTLER, 2016). These judgments produced by students show the existence of problematic areas in schools, which are caused by events that agitate the daily life or situations caused by actions carried out by peers and/or teachers.

Indeed, the judgments that students (but also teachers) produce around school sociability transcend issues concerning equality and merit as principles of justice - in this case, mobilized in inquiries related to school results obtained (a fair grade distribution) or referring to the learning processes in the pedagogical relationship with teachers (DUBET, 2009). It is, first of all, the issue of respect (PHARO, 2001; RAYOU, 1998; RESENDE; GOUVEIA, 2013) that surfaces, as a central justice reference mobilized by students, constraining actors’ freedom of action so as not to infringe the immanent value recognised to each individual and disconnected from contingencies of hierarchy between the different beings.

This polarisation on the idea of respect in the judgments produced must be framed, secondly, in a more comprehensive problematic. Indeed, in the context of the actors’ relationships within contemporary institutions, a moralization of social criticism (ZACCAÏ-REYNERS, 2008; STAVO- -DEBAUGE; DELEIXHE; CARLIER, 2018) can be identified, in which the appeal to the semantics of respect appears in parallel with the emergence of issues such as hospitality (STAVO-DEBAUGE, 2017), recognition (HONNETH, 2011) or decency (MARGALIT, 1996) when actors critically comment on institutions’ functioning and on ways of making the common.

Effectively, the access to the moral judgments that students erect, both concerning the relationship between equal and unequal individuals (RAYOU, 1998; RESENDE; GOUVEIA, 2013), allows us to understand how sociability is built within school space, through the different grammars that support their actions in making the common in school - to access the concepts of justice and acting logics that guide young people’s action (RAYOU, 1998; RESENDE; GOUVEIA, 2013) by penetrating the different repertoires of moral and political character through which students regulate life in common with the group of actors that inhabit the school space.

One technique can be particularly fruitful for accessing the moral frameworks that guide students’ conduct in school territory. This observation technique is named scenario survey (DANIC; DELALANDE; RAYOU, 2006). In a brief description of its fundamental premises, respondents are presented with a hypothetical narrative, of a dilemmatic nature, raising different possible moral and political judgments structured by different regimes of engagement and grammars of commonality (BOLTANSKI; THÉVENOT, 2006; THÉVENOT, 2006).

The narrative is accompanied by a set of exit propositions or hypotheses for the presented dilemma towards solving or remedying the injustice committed, with respondents being invited to order - from the unfairest to the fairest - the different evaluations that these propositions contain within them. Finally, respondents are also asked to carry out their evaluation of the presented scenario by writing a justification for the proposition that they consider to be the unfairest (which is subject to later categorization by the researcher), making direct reference to the moral and normative references that underlie their position.

The scenario presented5 in this article focuses on a student with a physical limitation that restricts his ability to move. Because of this vulnerability, the student arrives at a class already after the school bell rang, finding the remaining colleagues already seated in their respective places. His (repeated) delay in arriving at the classroom on time - delaying, consequently, the beginning of the lesson - motivates the teachers’ intervention. The admonition takes place in front of the rest of the class, and it is precisely on this remark that the focus of discord between these two characters resides.

A teacher opens the classroom door for the students to enter. With all students already seated, the teacher goes to the door to close it but notices one of her students is still heading for the classroom - Ricardo, a boy who has a lame leg. The teacher then says out loud: “Darn it, Ricardo! You, more than anyone, should be cautious in going to the classroom right before the school bell rings. Haven’t you noticed that you constantly leave the whole class waiting for you?”.

To the teacher’s remark, Ricardo replies: “I go to class when others go; I don’t see why I have to be different”.

The teacher immediately responded: “Be careful how you speak! Don’t you know you have to be on time?”.

Put the solutions set out below in ascending order, from the unfairer (nº1) to the fairer (nº5), placing only one letter in each case.

A. Given the situation experienced in class, the teacher shouldn’t have made any comment.

B. The teacher was right to comment the way she did.

C. The teacher’s comment should have been made after class, addressing the student directly.

D. Ricardo should have accepted the comment without replying to the teacher.

E. The teacher’s comment was incorrect and Ricardo was right to answer. (own translation)

The situation described can be understood as a moment of tension between different justice criteria, and the dispute it contains raises questions on the composition of the common. In particular, the narrative places the respondents in face of a duality between, on the one hand, the accommodation by the teacher concerning the application of the school regulation (in this case, concerning the time of entry in the classroom) by taking into account the student’s in question condition; or, on the other hand, the perspective of equality of all students, leaving the handicapped student the responsibility of adapting to the codified norms that regulate the conduct of all actors in the school space - which entails, as the teacher advocates, him going earlier than his classmates to the classroom. On the other hand, in the assessment made of the situation, there is also the question of the teacher’s approach. Publicizing the student’s vulnerability that her conduct causes is also subject to critical appreciation by the respondents.

An analysis of the justification categories around what respondents consider to be unfairest - the denial of justice as the starting point for accessing moral and normative references around the conceptions of a fair school (BOTLER, 2016) - allows us to identify the plurality of confronting grammars in the way respondents judge the situation at hand. The justifications appear structured, namely, in three major poles.6

Firstly, we can identify justifications that fall under the category Equal treatment of the student/ Non-discriminatory attitude, corresponding to 36.2% of the students in the sample. In a convergent perspective, 21.1% advocate that The teacher must treat the student differently/must be in solidarity with the student.

Focusing on relational justice issues, 22.6% of students are critical of the teacher’s conduct due to the publicising act that it entails (Non-publicizing of difference). Convergingly, 4.3% of the students in the sample defend that The teacher should have spoken differently.

In a different perspective, 7.6% put themselves in a civic perspective of preserving equality among students, oblivious to any particularities in the judgment of the situation (Equal compliance with the rules by the student). Finally, it is worth mentioning 4% of respondents who, in a composite perspective, while assuming the same positioning of equality before the codified norms that regulate all actors’ conduct within the school, also advocate an approach from the teacher that safeguards the student’s exposure to his colleagues (Non-publicizing of the student’s difference by the teacher + Equality in compliance with the rules by the student).

To analyse in greater depth the diversity of perspectives in confrontation, and the contrasts and affinities among them, we proceed to the presentation of some of the justifications that integrate the most representative response categories.

BETWEEN CIVIC EQUALITY AND HOSPITALITY IN ADDRESSING VULNERABILITY

In the case of the category Equal treatment of the student/Non-discriminatory attitude, the judgments that fall within it are fundamentally based on the objection of what, in the light of the civic order of worth, the surveyed students qualify as discriminatory behaviour on the part of the teacher. The following excerpts illustrate this point of view.

B. If we are in a society where the aim is to have no injustice and differentiation between people and especially in a school the teacher should never have said what she said.

Ricardo just because he is lame on one leg wouldn’t go sooner, because he has the right to “play” with his friends during the same time, the teacher should have understood his problem. (Q96: Female; School A; Professional Course, own translation)

Because it is stupid the fact that Ricardo has a leg problem he will be treated less than the others. C’mon! We are all the same, we all have the same rights. (Q284: Female; School E; Professional Course, own translation)

I think that the unfairest option was B because the teacher should be aware that for the student, the situation he finds himself in isn’t something easy to deal with, especially seeing all his “normal” classmates. There is in the lecturer’s comment a certain discriminatory tone towards the student. These were the main reasons that led me to choose this option. (Q261: Female; School B; Science and Technology Course, own translation)

Common to the set of justifications is the distinction between students as an element of injustice in the position taken by the teacher. The “differentiation” resulting from a blind interpretation of the school regulations is framed and problematised by the respondents as an intolerable injustice (BREVIGLIERI, 2009), with equality emerging as a moral reference and central horizon in the judgments built. In the classification of what is fair, the civic grammar (BOLTASNKI; THÉVENOT, 2006) guides these actors’ judgments, substantiating the moral sensitivity patently expressed by respondents that differences, in capacities, do not legitimise distinctions in terms of treatment or rights.

Moreover, in the criticism of what is qualified as a discriminative action - of not recognising the student as a full participant in the school as a community - the operation of de-singularisation (BOLTANSKI; THÉVENOT, 2006) by the respondents is clear, insofar as the problem is framed as a demand for rights for the collective, a common cause, distanced from private interests. It is, particularly, the perspective of a society of equals, without differentiation and with the “same rights” that is underlined as the legal and moral sensitivity crystallised among these actors in the course of their socialisation (HONNETH, 2011; MOTA, 2009; SCHILLING; ANGELUCCI, 2016) - a horizon that school cannot be apart from.

The same civic grammar can be mobilised differently in the case of judgments that fall into the category The teacher must treat the student unequally/must be in solidarity with the student. In this case, the perspective of civic equality is articulated with the grammar of hospitality (STAVO-DEBAUGE, 2017) in the students’ understandings expressed around the functioning of the school institution. This is the case with the perspectives uttered by the following respondents.

The teacher knowing that Ricardo was lame should be more tolerant towards his situation and if she thought about saying something she should have said it in private so that Ricardo doesn’t feel humiliated. (Q154: Female; School D; Language and Humanities Course, own translation)

Because the student is disabled the teacher should have more patience and wait for the student. (Q162: Female; School D; Visual Arts Course, own translation)

The teacher should have spoken to the student with greater understanding and respect, because the poor student is not to blame for being lame (or maybe he is, but in any case he is lame) and the teacher must, obviously, give him a greater break than to other students due to his disability. (Q172: Male; School D; Visual Arts Course, own translation)

From this set of judgments stands out the mobilisation of patience, tolerance, and understanding as moral categories in the approach to the situation and in the complaints about inhospitality - evoking indulgence on the part of the teacher as an accommodating competence (STAVO-DEBAUGE, 2014) and consequent suspension of criticism based on general judgments. If the question of hospitality arises from asymmetry in the ways of appropriating spaces, it is, namely, in the recognition of the difference and vulnerability - in this case, materialised in the “deficiency” shown by the student in question - that the claim for a “greater break” to be granted by the teacher to the student is grounded, as a hospitable arrangement that safeguards the “respect” for otherness (instead of an integration that requires submission to the rules). Such modality allows us to appease the tension and, thus, living in common (STAVO-DEBAUGE, 2014).

Within an arrangement between what is the collective interest, in the civic world, and attending difference - in this case, due to the student’s vulnerability - other respondents explicit how the hospitality should be operationalised by the teacher. This is the case for the next set of justifications.

I chose answer B because Ricardo should receive support mainly from teachers, since the school sometimes tends already to be elitist to colleagues. Therefore, the teacher must have an attitude of solidarity and support towards Ricardo, therefore in my opinion, the teacher shouldn’t have made any kind of comment. (Q9: Male; School A; Science and Technology Course, own translation)

In my opinion, a minimally well-educated teacher and with principles wouldn’t even dare to say what she said, she should look at him with a smile, the problem is that there are many of these [teachers] throughout the country’s schools. (Q502: Male; School C; Socioeconomic Sciences Course, own translation)

In my opinion concerning people who have physical disabilities, we shouldn’t be treating the way that teacher did, [she] disrespected and insulted him. If I were a teacher I would just say “Good morning Ricardo, are you in a good mood today?” (Q420: Male; School E; Science and Technology Course, own translation)

Again, what is alluded is the attitude of “solidarity”, of “support” towards the student as the teachers’ form of engagement that must prevail towards the situation in question. Her comment, due to its inhospitable character, should have given place to a “smile” as a hospitable gesture and to an accommodating greeting of the student (“Good morning Ricardo”). It is up to the teacher to close her eyes, in the sense of a civil inattention - a retraction of criticism (BREVIGLIERI; STAVO-DEBAUGE, 2007), based on general judgment criteria - concerning the students’ failures (in a civic perspective), his being late. It is in this dynamic of attitudes, that involve gestures and words but also silences (“shouldn’t have made any kind of comments”), that the hospitality takes place (STAVO-DEBAUGE, 2017).

Moreover, the first respondent highlights his critical perspective on what he believes to be a school whose functioning as an institution proves to be “elitist”, distanced from the actors that integrate it as a community. It is also in conjunction with the civic imperative of a school for everyone that requires a distinct engagement from the teacher with the student when it comes to interpreting and observing school regulations.

On the other hand, the last respondent also alludes to the effect that the teacher’s comment, both in terms of content and form, has on the student (“disrespected and insulted him”). The conduct, in the publicising that entails, is perceived as a moral insult (SIMIÃO, 2006), which undermines self-esteem. It is precisely the grammar of respect and the denial of recognition, associated with the experience of humiliation (PHARO, 2001; HONNETH, 2011), that displays particular prevalence in the moral judgments and denunciations of injustice made by other respondents on the relationship between all beings that populate school space.

THE IMPERATIVE OF RESPECT AND THE LIBERAL GRAMMAR AS A HOSPITALITY DEVICE

The focus on the issue of recognition and respect as moral categories emerges distinctively in the judgments built by the respondents who belong to the category Non-publicising of difference. Indeed, it is on this moral dimension of the offense perpetrated by the teacher that the evaluation of the scenario primarily concerns, as illustrated by the next group of justifications.

In my opinion, the teacher’s comment was inappropriate and should have been done after class with Ricardo alone. Ricardo is lame, and he has already enough complexes for being like that and I don’t think it’s right on the part of the teacher a humiliation before the class. (Q302: Male; School E; Technological Course, own translation)

The teacher shouldn’t have made any kind of comment because the boy may feel inferior. (Q152: Female; School D; Language and Humanities Course, own translation)

Although I consider that the teacher is right in wanting the student to arrive on time and therefore that he should come earlier, the way things are said is very important. The ideal way would be speaking to the student with understanding and respect. The teacher ends up losing the argument by acting the way she did. (Q50: Female; School A; Science and Technology Course, own translation)

In the construction of both judgments, it is noticeable that what is contested is not the teacher’s position concerning the observation of the school regulations, even with some respondents explicitly converging with what is the teacher’s position. But what is placed at the forefront of the qualifying judgment of the situation is the teacher’s conduct. Publicising the students’ vulnerability that her action causes, produces a humiliating outcome, affecting his self-understanding (OLIVEIRA, 2008), making him “feel inferior” in his value. It is, therefore, the “respect” that is evoked as the grammar guiding the interactions among actors (PHARO, 2001) as a practical position limiting the freedom of action - a civility constraint in order not to infringe the value recognised to an individual.

This principle constitutes a particularly structuring element of the students’ judgments and critical operations concerning beings of different worth (RAYOU, 1998) - a polarisation evidenced in the judgments around the making of the common within the school space (RESENDE; GOUVEIA, 2013). Moreover, the particular phrasing from the student of school A - “the way things are said is very important” - constitutes to a certain extent the synthesising expression of this grammatical rule that must be followed so that an actor is recognised as competent in his action (LEMIEUX, 2009). Illustrative of the centrality of respect as a principle that connects beings regardless of the different states of worth, the grammatical incompetence shown by the teacher has as consequence, in the respondents’ opinion, that “she ends up losing the argument”. In addition to the set of codified rights and duties inscribed in the school’s regulation, it is also the principle of decency (MARGALIT, 1996) that should structure the rules of coexistence between members of the school space, shaping their interactions to avoid situations of humiliation and protect those who are in a vulnerable state.

Other students, in denouncing also the teacher’s disrespectful behaviour, elaborate on how exactly the composition of the common can be made considering the student’s vulnerability. The next set of justifications exemplifies this point.

The teacher humiliated the boy in front of his class, she shouldn’t have done it, because the boy must already have self-esteem problems and these comments will only worsen the boy’s mental state. And he has every right to be late, to each his own. The teacher could have left the door open and start the class. So, when he entered the classroom he wouldn’t disturb that much. (Q264: Female; School B; Science and Technology Course, own translation)

The teacher was wrong to comment the way she did, for she embarrassed Ricardo in front of the whole class. Besides, Ricardo is only hurting himself, since the teacher can start the class without his presence. (Q40: Female; School A; Science and Technology Course, own translation)

At the first level of analysis, what is highlighted and object of censorship is the “shame” and the affecting of the self-esteem, in terms of the positive appreciation of oneself (SIMIÃO, 2006; OLIVEIRA, 2008), that the teacher’s action ends up provoking on the student - the humiliating effect of disclosing his vulnerability. The moral pain caused by the teacher’s conduct is recognised by the respondents as bystanders of the situation (SIMIÃO, 2006; OLIVEIRA, 2008).

On the other hand, the particularity of the judgment lays on the fact that the grammar of recognition (HONNETH, 2011) appears equally articulated by both respondents with the liberal grammar as a way of making the common: the rule generalised to all students, codified in the school’s regulation of arriving in the classroom on time is reduced, in the argument, to a matter of individual preference or choice (ERANTI, 2018; STAVO-DEBAUGE, 2014). Under the precept that each “to each his own”, attending what their respective personal interests are, it is up to each student to make their options - and bearing (exclusively) with the corresponding consequences.

As the respondent of school B advocates, the teacher leaving the “door open” of the classroom allows for the operationalisation of this liberal perspective, securing that the student does not disturb the functioning of the class upon his arrival and, thus, also safeguarding what is the general interest (the regular functioning of classes). Since the school form cannot lend itself to all deformations in terms of what are the rules that guide its activity, it is through this liberal logic that it is possible, in the view of the two students, to encase (STAVO-DEBAUGE, 2014) the students’ difference, giving the teaching establishment proof of plasticity, openness - and, thus, resolving the dispute in question. The liberal grammar constitutes itself, therefore, as a hospitality device for making the common.

Presenting a perspective structured by the grammar of recognition are also students who understand that The teacher should have spoken differently. In this case, the justifications distinguish by emphasising the moral requirements that fall on teachers in their relationship with students. This is the case for the next set of answers.

Due to the teacher’s position of respect and knowledge, she should set the example.

By acting in such a way, she allows students to treat his classmate differently. (Q248: Female; School B; Professional Course, own translation)

We must be careful about what we say. Carefully choosing the right words and show respect for each other. (Q159: Female; School D; Language and Humanities Course, own translation)

Of course the comment was incorrect. It just denigrates her image.

There are several ways to say the same. (Q445: Female; School C; Science and Technology Course, own translation)

In this group of justifications, it is the teacher’s domestic worth, derived from her statutory “position” within the chain of relationships between the different typified figures that inhabit the school space, that is brought up in the interpretation made by these respondents - but also, correlated, her condition as an adult and the added “knowledge” that comes with it. If it is up to the teacher to be a role model for beings of lesser worth (the students) from the perspective of interpersonal relationships (having to “set the example”), it is, to that extent, the teacher’s “image” who is denigrated by her conduct - and it is this inability in her interpersonal relationship with the student in question that is disqualified in the eyes of these respondents (BOLTANSKI; THÉVENOT, 2006). Respect, as a moral principle that should guide the relationship reciprocally, not only between equals but also between unequal individuals in the school space, is highlighted as common proof binding all beings, regardless of their respective hierarchical positions (RESENDE; GOUVEIA, 2013).

THE INTEGRATIVE ACCOMMODATION AND THE TEACHER’S AUTHORITY

If previous perspectives place (with different tonalities) focus on accommodating the functioning of the teaching institution as a community to the student’s vulnerability, divergent perspectives can be found in other respondents. This is the case of respondents who fall into the category Equal compliance with the rules by the student. From a different angle stemming from the civic order of worth, it is the equality among all students under the school regulation as a device that governs the conduct of the actors in the school territory (BOLTANSKI; THÉVENOT, 2006) that is particularly emphasised. The following justifications illustrate this viewpoint.

Having a physical disability of this type is not a reason for positive discrimination when it comes to being late for class. What Ricardo should do is go to the classroom earlier, because if the other students are late due to other problems they will not be excused. (Q440: Female; School C; Science and Technology Course, own translation)

Ricardo shouldn’t answer the teacher, for she is right, if he has more difficulty walking he should arrive earlier. He is not to be blamed for being like that, but he must be treated like others, because if the teacher doesn’t scold him it will be unfair to others too. (Q325: Female; School E; Visual Arts Course, own translation)

If in previous perspectives the civic grammar is evoked to support complaints on the teacher’s discriminatory behaviour, in the case of these respondents, the same grammar is summoned but in a distinctive logic. Namely, it is the civic equality of all students under the school’s regulations that emerges, with the attending to particularisms being ruled out and any forms of “positive discrimination” being considered unfounded (BOLTANSKI; THÉVENOT, 2006). Failure to comply with the collective will is understood as favouring divisions and susceptible of generating arbitrariness in the application of regulations (“it will be unfair to others”). In this renunciation of the particular as advocated moral imperative, it is therefore up to the student in question to accommodate his conduct - by going earlier to the classroom, and thus ensuring compliance with the school regulation as an equivalence device among all students. This integrative accommodation, presupposing the imposition of the constraints of belonging to the school as a community, opposes, therefore, logics of hospitality (STAVO-DEBAUGE, 2017).

Finally, the question of authority also arises among students whose perspective fits into the category Non-publicising of the student’s difference by the teacher + Equality in compliance with the rules by the student. These judgments are characterised by a composite understanding, insofar as, while assuming a perspective in favour of the student’s conformity with the school’s regulations, the disrespectful character appointed to the teacher’s approach on the issue is nevertheless integrated into the moral evaluation produced. This is the case with the next justifications.

Although the teacher had an attitude in my perspective slightly impolite, the truth is that she is an authority figure and as such Ricardo should not have responded that way, whether he was right or not. (Q489: Female; School C; Socioeconomic Sciences Course, own translation)

Since the student has a mobility problem, I think the teacher should have made a more cautious comment so as not to “offend” her student in front of the other colleagues, but on the other hand the student shouldn’t have responded, because students should never reply to teachers. (Q522: Female gender; School C; Visual Arts Course, own translation)

Stands out from these judgments the way, in the articulation of grammars, the question of respect appears less pronounced compared to previous judgments. This is revealed in the (euphemistic) formulation of the problem related to publicising the vulnerability - characterising the conduct of the teacher as “slightly impolite” or advocating a “more cautious” addressing of the problem, so as not to “offend” the student. In this sense, if the issue of offense as a moral category associated with interpersonal forms of disrespect is nevertheless mobilised in the way the teacher’s conduct is judged and the moral principles that should guide her performance (thus recognising the moral dimension of the occurrence), it appears, however, in the background.

In turn, it is the question of teachers’ “authority” that predominates in the composition of grammars, and the student, as the subordinate element in this chain of relationships, must show obedience (BOLTANSKI; THÉVENOT, 2006). If in previous judgments it is the teachers’ worth that is disqualified by the humiliation perpetrated to the student as a consequence of her conduct, in this case, it is the student’s act of replying - interpreted as challenging the authority - that is the object of the disqualifying criticism in both judgements. Moreover, this domestic logic is strongly expressed in the postulate common to both justifications: that “students should never reply to teachers”, whether they are “right or not”.

MAPPING THE PLURALITY OF MORAL POSITIONS

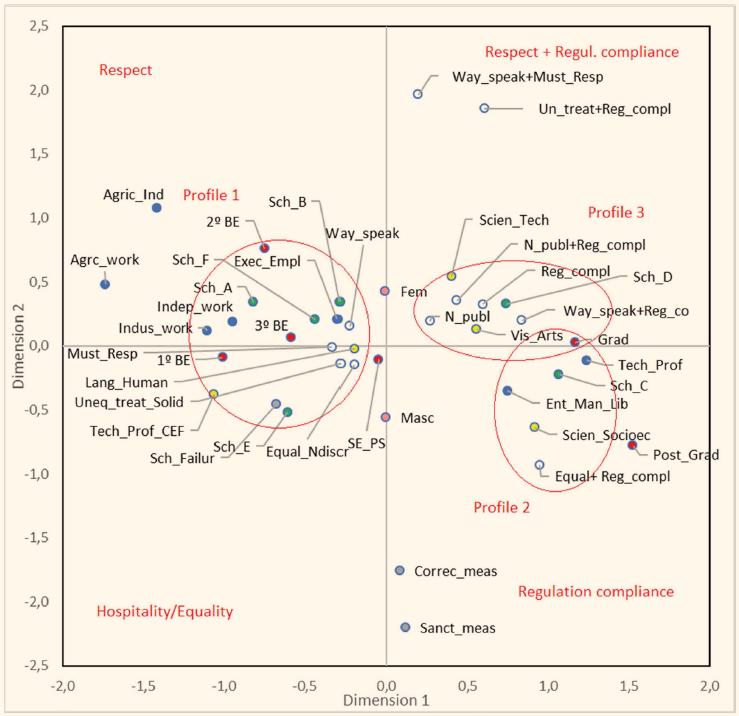

Finally, to understand how the constellation of justice principles at stake, but also the relationship of these moral judgments with a set of characterization variables of the student population inquired,7 we take a distinct look through a multiple correspondence analysis. The factorial plan obtained allows us to display in the graph’s different quadrants the plurality of judgment frames produced by the respondents (including the relations of confluence and opposition to each other), while also drawing different profiles through the social characterisation data (Figure 1).

Source: Survey applied within the research project “Gender, Inequality and Humiliation: feelings of injustice in school”, 2010-12 (N=716).

FIGURE 1 FACTORIAL PLAN

In the case of the first identified profile (profile 1), it is composed of judgments that focus, on the one hand, on relational justice issues (with respect as moral vocabulary), but also, on the other, in terms of hospitality and criticism of logics qualified, from the civic world, as discriminatory.8

The characterisation variables allow us to account for the socio-economic profile of the students whose opinions fall into these categories. Firstly, the respondents attend the teaching institutions of the sample that host the least socially favoured school population - namely, schools “A”, “B”, “E” and “F”, where students from the lower social classes are predominant, despite the contrasting geographical locations (see footnote 5).

Regarding the mother’s socio-professional categories, these are associated with the lower levels of the secondary economic sector - Industrial workers, Self-employed and Executing employees. The low socio-professional status is reinforced by the mother’s educational levels, characterised by a schooling level limited to Basic Education. In terms of their profile as students, these are students from Languages and Humanities and enrolled in the Technical and Professional courses, as well as Education and Training Courses (ETC) - teaching tracks that predominantly receive students from more disadvantaged social contexts. Moreover, this profile is also characterised by students who present, at least, one failure counted throughout their school trajectory.

This first group appears, in the factorial plan, in a relationship of opposition with profile 2, which is characterised, in turn, by an evaluation of the scenario in which the focus is placed on compliance with the school rules, in a perspective of equality of actors under the normative orientations inscribed in the school regulations as a civic device for the governing of behaviours (departed from any particularisms).9

In this case, the characterisation variables reveal a different social context. It is composed of students from school C, located at the centre of Lisbon, and attended predominantly by middle-class students. Concerning the mothers’ socio-professional categories, this group includes the two highest categories. They are, namely, children of Entrepreneurs, Managers and Liberal professionals, as well as Technical professionals. This socially advantageous landscape is also reinforced by the mother’s academic qualifications variable, with the Post-graduate category (namely, Master’s or PhD degree) integrating this profile. Regarding the course attended, they are students from the Scientific-Humanistic field, specifically Socioeconomic Sciences.

In the case of profile 3, it corresponds to the group of respondents in which the criticism of the inhospitable character of the teacher’s conduct resulting from the publicising of the student’s vulnerability is articulated with the perspective of civic equality of all students under the set of codified rules in the regulations, thereby invalidating differentiations.10 Also in opposition to the profile that judges the situation by recommending a different approach by the teacher, this profile includes students whose mother hold a graduate or bachelor diploma and that attend Visual Arts courses, along with Sciences and Technologies - the latter being typically an educational route that predominantly hosts contingents of students from more privileged socioeconomic backgrounds.

Finally, a special reference for the gender variable should be made. It is relevant to point out that if male students are located in the lower quadrants of the factorial plan - where the understandings related to the relationship towards the rules (positive discrimination or equality under the rules) are situated -, while female students are located in the two upper quadrants, where issues of relational justice predominate and where the problematic of respect and publicising in the teacher’s conduct appear more emphasised in the moral judgments and qualifying evaluations.

MAKING THE COMMON IN THE PLURAL: RECOGNITION IN THE RESPECT FOR DIFFERENCES

Having arrived at the end of this analytical path, it is worth highlighting some interpretative lines based on the scenario presented to the final year students of six Portuguese secondary education state schools. In the mapping that we have produced from the research data, in other articles (RESENDE; GOUVEIA, 2013) it has been possible to show that students from different secondary schools distributed across different regions of the country are bonded to the common in the plural when they are faced with dilemmas of similar nature to the one which appears in the intrigue narrated in the scenario. Instigating plots like this, it should be noted, do not arise from chance. They are part of everyday school experiences and are constantly revealed by students and teachers when, in the course of a conversation about school environments, we ask what events occurred that impel them to think about their commonality. In the presentation of scenarios where the unequal is unequally treated, the manifestation of these differences, not only are not forgotten but are experiences that affect them intensively. And we took seriously the data that our initial informants brought to us on these physical vulnerabilities and its consequences.

And, if there were any doubts, the treatment of the information taken from the answers provided by the respondents indicates that the intrigue exposed there, on the one hand, did not leave any respondent indifferent and, on the other, the way the story affects them mobilises different principles of justice raised to a high level of generality, often combined with other regimes of engagement of greater proximity and familiarity (THÉVENOT, 2006). And it is, from the creative modalities on how students compose their justified positions in the face of a disturbing situation, that we find that the common is built in schools, not in a unilateral, homogeneous way, but in a plurivocal one - that is, in multiple voices.

The sociological significance of the compositions skillfully drawn up by the respondents has profound meanings, since their experiences resulting from school sociability combine relative stability with frequent (often unpredictable and other times surprising) detonations. And if in the altercations between students there are treatment inequalities derived from the knowledge of the school results, that is, from the classifications obtained in school tests and assignments, the equality in the procedures of how to treat each other gains increasingly more notoriety, even when some do not express it loud and clear, out of fear or because of shells that hinder their body expression necessary for that purpose (BREVIGLIERI, 2007).

Even when the playfulness, the joking or humour enter softly or abruptly into conversations about problems that affect the ways of treatment used among peers, or, how appears in the story, the way a teacher treats a particular colleague (friend or not), that treatment is an integral part of the unplanned menu of making the common in the plural in Portuguese schools. This means that the issue is a sensitive problem, both at the relational level among students studying in the same class and that hang out with others during recess, at school breaks that are common to all classes, or between the student category (in the figures of adolescents and young people) when they confront teachers who, for example, do not reply to their greetings - “good morning, teacher” or “good afternoon, teacher”.

And only a minority of respondents present themselves stuck to the formal use of the general treatment rules inscribed in school regulations. And within this low percentage, there is a proportion of them who do not lack giving attention to the treatment issue, since they oppose the way the teacher reacts when she closes the classroom door and realises that Ricardo had not yet entered. If their normativity is based on the belief in formal equality of treatment that is inscribed in the regulations understood as conventions whose rules must be applied equally to everyone, disregarding any particularism, they are sensitive to the destructive ways of the self-esteem caused by the public criticisms addressed by adults or colleagues, in many situations that make up the daily life of a school, to figures of lesser worth (BOLTANSKI; THÉVENOT, 2006) who exhibit vulnerabilities, such as the case of this story’s protagonist.

In the plurality of beliefs on which their moralities are based, the issue of mutual respect among each other is something that permanently confronts them with themselves and in the continuous relationships they maintain with colleagues, friends, but also with beings of greater worth (BOLTANSKI; THÉVENOT, 2006), as is the case with teachers. It is through this path that vigorously enters in schools the questioning about recognition in the face of everything that differentiates them as human beings, such as the colleague who notoriously presents, in his corporeality, a motor disability. If the majority of respondents indicate that the teacher must attend to this detail, allowing the student to arrive a little later to class because, despite his limp, he has the equal right to enjoy for the same period, an even major problem is the public exposure that the colleague suffers from the aforementioned deficiency made out in the open by the teacher.

The teacher’s public remark that the class doesn’t start immediately due to his permanent delay, and that his lagging in entering the class is a result of his difficulty to walk swiftly, is generally considered to be unacceptable, and in some of the justifications is considered intolerable, i.e., as a public demonstration difficult to bear. The students’ critical operations on the teacher’s form of acting in an attempt to adapt to the tension caused by Ricardo’s delay demonstrate that the common side of students (even in their plurality) is very sensitive to the consequences of the controversies that expose in public the dignity of humanity that each one carries in its corporeality.

Displaying in public, even if in an unintentionally spiteful way, the vulnerability of a colleague, in this case, a body that exhibits a motor disability, is a reprehensible way of being with everyone at a school, namely in classrooms, privileged spaces in school to learn how to make the appropriate and adjusted coexistence among each other. In the bonding between each and everyone with their environment, in the classroom or outside the classroom, the big discomfort that is conferred by the tribulations guided by the publicising of statements performed by the teacher turns these territories into uninhabitable spaces.

This has been another discovery that has taken place with these successive immersions in school institutions over the past 15 years, designed to examine how students have been, over time, exercising the arts of making the common in the plural. The enigmas around how habitability of school space is made have led us to consider the importance of how different generations (in terms of age, but also of their seniority in a given educational institution) accommodate people who enrol every year.

It is through this acute sense that the problem of mutual respect - respect is necessary - cannot be considered, conceived as a sociological problem, within the scope of school sociability, if there is no increased attention in linking it to other modalities of creative action that result from the processes and procedures associated with welcoming, inhabiting and providing school territories as spaces of good accommodation - namely, as spaces where qualitative forms of hospitality are invested for the newcomer that arrives, with the differences manifestly brought by the corporeality of each one. These are also the sphinxes that encourage us to continue this journey of looking for other paths that are present in school governance exercises aimed at building an inclusive school. This presupposes that qualified good school governance attends to everyone since the inclusive school cannot drift to exclusionary schooling.

We must not forget that there is no school without schooling. The reverse is true, placing schooling at the centre of the analysis is a decisive bet for us, considering that school sociability establishes bridges with the formats forged by the learning processes. It is important to note that those formats give form and content to the acts of schooling, conceived as instruments that provide students with their knowledge and their wisdom - which are part of their multiple experiences and that involve them in many of the events that take place at school.

REFERENCES

BOLTANSKI, Luc; THÉVENOT, Laurent. On justification: economies of worth. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2006. [ Links ]

BREVIGLIERI, Marc. L’arc expérientiel de l’adolescence: esquive, combine, embrouille, carapace et étincelle… Éducation et Sociétés, v. 1, n. 19, p. 99-113, 2007. [ Links ]

BREVIGLIERI, Marc. L’insupportable. L’excès de proximité, l’atteinte à l’autonomie et le sentiment de violation du privé. In: BREVIGLIERI, Marc; LEFAYE, Claudette; TROM, Danny (org.). Compétences critiques et sens de la justice. Paris: Economica, 2009. p. 125-149. [ Links ]

BREVIGLIERI, Marc; STAVO-DEBAUGE, Joan. L’hypertrophie de l’œil: pour une anthropologie du passant singulier qui s’aventure à découvert. In: CEFAÏ, Daniel; SATURNO, Carole (org.). Itinéraires d’un pragmatiste: Autour d’Isaac Joseph. Paris: Economica, 2007. p. 79-98. [ Links ]

BOTLER, Alice Miriam Happ. Injustiça, conflito e violência: um estudo de caso em escola pública de Recife. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 6, n. 161, p. 716-732, jul./set. 2016. [ Links ]

DANIC, Isabelle; DELALANDE, Julie; RAYOU, Patrick. Enquêtes auprès d’enfants et de jeunes: objets, méthodes et terrains de recherche en sciences sociales. Rennes: PU Rennes, 2006. [ Links ]

DUBET, François. L’école des chances: qu’est-ce qu’une école juste? Paris: Le Seuil, 2004. [ Links ]

DUBET, François. Conflits de justice à l’école et au-delà. In: DURU-BELLAT, Marie; MEURET, Denis (org.). Les sentiments de justice à et sur l’école. Bruxelles: De Boeck, 2009. p. 43-55. [ Links ]

ERANTI, Veikko. Engagements, grammars, and the public: from the liberal grammar to individual interests. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, v. 5, n. 1-2, p. 42-65, mar. 2018. doi: 10.1080/23254823.2018.1442733 [ Links ]

EURYDICE. A educação para a cidadania nas escolas da Europa. Lisboa: Gabinete de Informação e Avaliação do Sistema Educativo do Ministério da Educação de Portugal, 2005. Disponível em: http://www.oei.es/valores2/cidpt1.pdf. Acesso em: 22 jun. 2020. [ Links ]

HONNETH, Axel. Luta pelo reconhecimento: para uma gramática moral dos conflitos sociais. Lisboa: Edições 70, 2011. [ Links ]

LEMIEUX, Cyril. Le devoir et la grâce. Paris: Economica, 2009. [ Links ]

MARGALIT, Avishaï. The decent society. London: Harvard University Press, 1996. [ Links ]

MOTA, Fábio Reis. Manda quem pode e obedece quem tem juízo? Uma reflexão antropológica sobre disputas e conflitos nos espaços públicos brasileiro e francês. Revista Dilemas: Revista de Estudos de Conflito e Controle Social, Rio de Janeiro, n. 4, p. 107-126, 2009. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Luís Roberto Cardoso de. Existe violência sem agressão moral? Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, v. 23, n. 67, p. 135-146, 2008. [ Links ]

PHARO, Patrick. La logique du respect. Paris: Les Éditions du CERF, 2001. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Decreto-Lei n. 6, de 18 de janeiro de 2001. Aprova a reorganização curricular do ensino básico. Diário da República, Lisboa, Portugal, n. 15, 18 jan. 2001. Série I-A. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Decreto-Lei n. 209, de 17 de outubro de 2002. Altera o artigo 13º e os anexos I, II e III do Decreto-Lei n. 6, de 18 de janeiro de 2001, que estabelece os princípios orientadores da organização e da gestão curricular do ensino básico, bem como da avaliação das aprendizagens e do processo de desenvolvimento do currículo nacional. Diário da República, Lisboa, Portugal, n. 240, 17 out. 2002. Série I-A. [ Links ]

PUREZA, José Manuel; HENRIQUES, António Mendo; FIGUEIREDO, Carla Cibele; PRAIA, Maria. Educação para a cidadania: cursos gerais e cursos tecnológicos 2. Lisboa: Ministério da Educação, 2001. [ Links ]

RAYOU, Patrick. La cité des lycéens. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1998. [ Links ]

RESENDE, José Manuel. A sociedade contra a escola? A socialização política escola num contexto de incerteza. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget, 2010. [ Links ]

RESENDE, José Manuel; DIONÍSIO, Bruno. A escola pública como “arena” política: contexto e ambivalências da socialização política escolar. Análise Social, Lisboa, v. 176, p. 661-680, out. 2005. [ Links ]

RESENDE, José Manuel; GOUVEIA, Luís. As artes de fazer o comum nos estabelecimentos de ensino: outras aberturas sociológicas sobre os mundos escolares. Forum Sociológico, Lisboa, v. 23, p. 97-106, 2013. [ Links ]

SCHILLING, Flávia; ANGELUCCI, Carla Biancha. Conflitos, violências, injustiças na escola? Caminhos possíveis para uma escola justa. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 46, n. 161, p. 694-715, jul./set. 2016. [ Links ]

SIMIÃO, Daniel Schroeter. Representando o corpo e violência: a invenção da “violência doméstica” em Timor-Leste. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, São Paulo, v. 21, n. 61, p. 133-45, 2006. [ Links ]

STAVO-DEBAUGE, Joan. L’idéal participatif ébranlé par l’accueil de l’étranger: l’hospitalité et l’appartenance en tension dans une communauté militante. Participations, v. 9, n. 2, p. 37-70, 2014. [ Links ]

STAVO-DEBAUGE, Joan. Qu’est-ce que l’hospitalité? Recevoir l’étranger à la communauté. Montréal: Liber, 2017. [ Links ]

STAVO-DEBAUGE, Joan; DELEIXHE, Martin; CARLIER, Louise. HospitalitéS: l’urgence politique et l’appauvrissement des concepts. SociologieS, 13 mar. 2018. Disponível em: http://journals.openedition.org/sociologies/6785. Acesso em: 10 ago. 2018. [ Links ]

THÉVENOT, Laurent. L’action au pluriel: sociologie des régimes d’engagement. Paris: La Découverte, 2006. [ Links ]

THÉVENOT, Laurent. Conventions for measuring and questioning policies: the case of 50 years of policy evaluations through a statistical survey. Historical Social Research, v. 36, n. 4, p. 192-217, Jan. 2011. [ Links ]

ZACCAÏ-REYNERS, Nathalie. Questions de respect: enquête sur les figures contemporaines du respect. Bruxelles: Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 2008. [ Links ]

1The article was reviewed by Maria Carmen de Frias e Gouveia. We would like to take this opportunity to wholeheartedly express our deepest gratitude for her overwhelming kindness and thorough revision.

2Cf. the documents that, to some extent, supported the use of this public action by the Ministry of Education and which were consulted by us at the time, in 2004-2007: Eurydice (2005); Decree-law no. 6/2001 and no. 209/2002; Pureza et al. (2001).

3In this relationship, it is noticed, namely, a “particularly marked electoral absenteeism among youth groups, less identification with political parties (Freire e Magalhães, 2002, p. 139) -, [but] no less certain is the fact that it is in the more youthful profiles that non-conventional forms of participation (Viegas e Faria, 2004, p. 245) acquire a very expressive growth” (RESENDE; DIONÍSIO, 2005, p. 673, own translation).

4This article is based on empirical data gathered from the research project funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and by the CIG-Commission for Citizenship and Gender Equality, entitled “Gender, Inequality and Humiliation: feelings of injustice in schools”, approved in 2008 with the reference PIHM/GC/0085/2008. The research took place between 2009 and 2012.

5The scenario is part of a survey developed for the research project mentioned in the previous footnote. Applied to students attending the 12th grade, a total of 716 questionnaires were validated. In a brief description of the sample, the survey was applied in six educational institutions with socially and geographically contrasting school audiences. School ‘A’, located in the centre-north of Portugal, is characterized by students from the popular social classes, related to agriculture and small companies, as well as the low educational qualifications of parents. With a profile of students predominantly from the lower social classes, we have school ‘B’ - located in the centre of Lisbon -, school ‘E’ - in a municipality adjacent to the country’s capital - and school ‘F’ - located in a district capital of Portugal’s countryside. Finally, the schools with the most socially favoured profiles are schools ‘C’ and ‘D’. The first, located in the Central Business District of Lisbon, has predominantly middle and upper-middle-class students, and with most parents presenting high school qualifications. In the case of school ‘D’, located in a municipality contiguous to the capital, it is attended mostly by middle-class students.

6Considering space constraints, on the one hand, and the lower representativeness in terms of the proportion of students whose answers fit into them, on the other, five categories are left out of the analysis - used only for the factorial analysis presented below) of this article. These categories are: The student must answer (1.3%), The teacher should have spoken differently + Equality in the student’s compliance with the rules (1.3%), Equal treatment of the student by the teacher + Equal compliance with the rules by the student (1%), The teacher should have spoken differently + The student should answer (should have spoken differently) (0.3%), Acceptance that the teacher deals with the student differently + Equality in the student’s compliance with the rules (0.3%).

7The factorial plan is constructed with a set of variables. As active variables, all 11 justification categories were inserted. Secondly, as complementary variables for social-economic characterisation, five were selected: Mother’s socio-professional category, Mother’s educational qualifications, Course attended (both scientific-humanistic and technical or professional).

8This group includes students whose justifications fall into the following categories: The teacher should have spoken differently; Student must respond; Equal treatment of the student/Non-discriminatory attitude and The teacher must treat the student differently/must be in solidarity with the student.

9It corresponds to the category Equality in the treatment of the student by the teacher + Equality in compliance with the rules by the student.

10Namely, students whose justifications fall into the categories: Non-publicising of the student’s difference by the teacher + Equality in compliance with the rules by the student; The teacher should have spoken differently + Equality in the student’s compliance with the rules; Not publicising the difference; Equality in compliance with the rules by the student.

Received: September 04, 2019; Accepted: April 09, 2020

texto en

texto en