Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 0100-1574versión On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.50 no.177 São Paulo jul./sept 2020 Epub 20-Oct-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/198053147086

ISSUE IN FOCUS

CURRICULUM IDEOLOGIES AND CONCEPTIONS OF DIVERSITY AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

IUniversidad Metropolitana de Ciencias de la Educación (UMCE), Santiago, Chile; cesar.pena@umce.cl

IIPontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso (PUCV), Viña del Mar, Chile; tatiana.lopez@pucv.cl

In this study, we aimed to identify the curriculum ideologies of preservice teachers and the relationship between those and their conceptions of diversity and social justice. Data were obtained from the application of the inventory of curriculum ideologies to 231 participants and semi-structured interviews to a purposeful sample of participants in a Chilean university. Results showed that the Learner Centered Ideology was predominant and that a significant number of participants showed ideological eclecticism. Despite the focus on learning, some defend Scholar Academic and Social Efficiency arguments. Moreover, there is a gradual relationship between ideologies and conceptions of diversity and justice, varying from a marked coherence to total absence of relationship. Finally, implications for research and initial teacher education are discussed.

Key words: TEACHER EDUCATION; CURRICULUM; IDEOLOGY; SOCIAL JUSTICE

El estudio buscó identificar las ideologías curriculares de futuros profesores y su vínculo con concepciones sobre diversidad y justicia social. Los datos se obtuvieron de la aplicación del inventario de ideologías curriculares a 231 participantes y entrevistas semiestructuradas a una muestra intencionada del total en una universidad chilena. Los resultados muestran que predomina la ideología Centrada en el Aprendizaje y que una proporción importante muestra eclecticismo ideológico. A pesar del foco en el aprendizaje, algunos defienden argumentos academicistas y eficientistas. Es gradual la relación entre ideologías y concepciones sobre diversidad y justicia, desde una marcada coherencia hasta ausencia de dicha relación. Finalmente, se discuten implicancias para la investigación y la formación inicial docente.

Palabras-clave: FORMACIÓN DE PROFESORES; CURRÍCULO; IDEOLOGÍA; JUSTICIA SOCIAL

O estudo se propôs a identificar as ideologias curriculares de futuros professores e seu vínculo com concepções sobre diversidade e justiça social. Os dados foram obtidos por meio da aplicação da lista de ideologias curriculares a 231 participantes e de entrevistas semiestruturadas a uma mostra selecionada de universitários chilenos. Os resultados demonstram o predomínio da ideologia Centrada na Aprendizagem e uma proporção importante mostra ecletismo ideológico. Apesar do foco na aprendizagem, alguns defendem argumentos acadêmicos e eficientistas. Há uma relação gradual entre ideologias e concepções sobre diversidade e justiça, de uma coerência marcante até a ausência de tal relação. Finalmente, são discutidas implicações para a pesquisa e a formação inicial docente.

Palavras-Chave: FORMAÇÃO DE PROFESSORES; CURRÍCULO; IDEOLOGIA; JUSTIÇA SOCIAL

Cette étude vise à identifier les idéologies curriculaires de futurs enseignants et leur rapport avec les conceptions de la diversité et de la justice sociale. Les données ont été obtenues en soumettant la liste des idéologies curriculaires à 231 participants et à travers des entrevues semi-structurées auprès d’un échantillon sélectionné d’étudiants universitaires chiliens. Les résultats obtenus indiquent que l’idéologie centrée sur l’apprentissage est prédominante et que l’éclectisme idéologique est aussi présent en grande proportion. Malgré l’accent mis sur l’apprentissage, quelques uns soutiennent des arguments académiques et efficientistes. Il existe une relation progressive entre les idéologies et les conceptions de la diversité et de la justice, allant d’une cohérence remarquable jusqu’à l’absence de relation. Les implications de ces résultats pour la recherche et la formation initiale des enseignants sont discutées en conclusion.

Key words: FORMATION DES ENSEIGNANTS; CURRICULUM; IDÉOLOGIE; JUSTICE SOCIALE

A great deal has happened in the curricular field since the work of Bobbitt (1918) and Tyler (1984) in the twentieth century. Their theoretical-technical momentum grew in the 1960s. Since then, the curriculum has been the object of debate, research, and theorization by various authors from different perspectives. In fact, the very meaning of the concept curriculum has been and continues to be the object of debate in the education field. At its core, Bobbitt’s work highlighted the debate on education in the capitalist context of the early 20th century in the United States. Later, the debate gained strength when Tyler (1949) developed a solid theory from a technical perspective at the service of his time’s education system. His influence has lasted until the present day, and it has become a necessary reference among those who interpret or criticize his proposal for curriculum design based on four technical questions (TYLER, 1949).

Kemmis, Fitzclarence and Manzano (2008) point out that Tyler’s proposal implies a design that is by no means neutral. On the contrary, their questions about content selection, preparation of instructional material, teaching methodologies and assessment claim neutrality, but focus on operationalizing educational objectives. Precisely because there is no such neutrality, Kemmis Fitzclarence and Manzano (2008) note that Tyler’s theoretical-technical orientation and place it historically against the practical and critical perspective of the curriculum.

Regarding the role of teachers, Diaz Barriga (1993) criticizes Tyler’s model because it ignores teachers as a source of curriculum creation, giving them a mere technical, implementing role. On the contrary, Stenhouse (1984) has a curriculum perspective that is the result of teacher research, proposing its construction from teaching practice, developing and carrying out the curriculum to action. With Stenhouse emerges a critical and emancipatory curriculum perspective, focusing on teacher participation to build curriculum from teachers’ praxis.

Since the 1970s, the critical perspective of the curriculum has gained strength. As Sanz Cabrera (2003) points out, the influence of the Frankfurt School made it possible for the critical perspective to give way to the conception of the “curriculum as a reconstruction of knowledge and configuration of practice” (p. 13). Consequently, the positivist and technocratic vision of curriculum weakened and the reconceptualist approach to curriculum emerged seeing it as intimately linked to social reality, historically situated, and culturally determined. Reconceptualists (e.g., M. Apple, S. Grundy, S. Kemmis, W. Carr, W. Pinar, J. Gimeno Sacristán, A. Pérez Gómez, and J. Torres) understand curriculum as a political act, capable of fostering the emancipation of the less privileged.

A more recent synthesis of curricular perspectives was made by Schiro (2013) who defined four major curricular ideologies that make it possible to conceptually organize what underlies technical decisions. These are: 1) Scholar Academic ideology; 2) Learner Centered ideology; 3) Social Reconstructionist ideology; and 4) Social Efficiency ideology. This categorization allows us to explain the purpose of a particular type of curriculum and reveals what, for more than a century, has been a focus of conflict among those who defend various curricular designs for the education system. We consider this classification to be appropriate for our study and we examine it in depth to later explore its relationship with the concepts of diversity and justice in education.

RESEARCH PROBLEM

In various contexts, including Chile, the majority educational discourse converges on the need for education based on the principles of quality and equity. Today, from a critical and expanded perspective, this implies a social justice approach, affirming diversity in all its dimensions and helping to eradicate segregation (SSLEETER; MONTECINOS; JIMÉNEZ, 2016; ZEICHNER, 2018). Despite the growing development of this perspective at the international level, there is no consensus on what education for social justice is (CARLISLE, JACKSON; GEORGE, 2006; MURILLO; HERNÁNDEZ-CASTILLA, 2011). Nor is there agreement on how Initial Teacher Education (ITEd) can address inequality and diversity in all its manifestations.

For example, Chilean universities are not yet making the necessary progress with explicit curricular activities on diversity and justice, despite the urgent need arising from Chilean cultural pluralism, structural inequality and the growing migration (FERNÁNDEZ, 2018). One of the studies that warned of this lack of progress was made by Venegas (2013), who noted at the time that, among teacher education programs, few incorporated contents on diversity such as native cultures, rural education, gender, multiculturalism, and community- -society relationships.

Although there has been progress in universities to include diversity and justice issues in ITEd, it is still insufficient as there are isolated changes in courses on diversity and research projects with a reduced focus (JIMÉNEZ-VARGAS; MONTECINOS-SANHUEZA, 2019). Research in the indigenous field is predominant, and there is still a need to study other areas of cultural diversity and to incorporate the social justice perspective into applied research.

In addition, the approach to concepts such as diversity and inclusion often focuses on the Special Needs approach. However, this is only one part of the spectrum of identities, sociocultural backgrounds, and orientations that enter the classroom. It is this broad spectrum that is not studied as a whole by the Chilean ITEd. For this reason, here we underline the premise of Banks and Banks (2016) who note that addressing diversity from specific instances (courses) is incomplete. On the contrary, they recommend a comprehensive approach, where many or all curricular activities are responsible for educating for diversity and justice. Hence, our study explored preservice teachers’ conceptions about diversity and justice avoiding a focus on a specific course, which also helps to reduce the social desirability bias.

Our research problem implied establishing a bridge between the need to know the ideologies of future teachers and the need to know their conceptions of diversity and justice, trying to broaden the view on these concepts and assuming that their treatment is the responsibility of all the learning spaces (BANKS; BANKS, 2016). Thus, the research question that guided this study was: What are the curriculum ideologies to which preservice teachers adhere and how do these ideologies relate to their conceptions of diversity and justice in education? To answer it, we went through three stages: 1) identifying the curricular ideologies; 2) investigating the conceptions of diversity and social justice; and, 3) establishing the possible links between the ideologies and these conceptions. By virtue of the concepts involved, we describe our theoretical framework as follows.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Here we delve into the two axes that constitute our theoretical foundation: the first one connects curriculum to ideology; the second addresses the concepts of diversity and social justice within the framework of the ITEd.

CURRICULUM AND IDEOLOGY

One of the key thematic contents in ITEd is the study of curriculum, both as curriculum theory and, design, and implementation in the classroom. Less addressed are the curricular philosophies or ideologies that impact on educators’ discourses and practices. Several authors have suggested the need to unveil the various curricular ideologies (SCHIRO, 2013) or meta-theories (KEMMIS et al., 2008) before addressing the design and practical implications, avoiding analyses that only focus on technical aspects. These ideologies are based not only on structured knowledge, but also on everyday knowledge influenced by systematic knowledge and beliefs, incorporating values and/or prejudices. In this study, a curricular ideology is understood as a set of assumptions about different educational aspects.

Schiro (2013) argues that any approach to the school curriculum derives from a curricular ideology, i.e. a platform or prism from which the view of the role of education can openly differ. In his opinion, there are four major curricular ideologies: the Scholar Academic ideology, the Learning Centered ideology, the Social Reconstructionism ideology, and the Social Efficiency ideology. These same ideologies can be expressed or defended by school systems, by institutions, or by individuals. Thus, they can also be explored in the case of preservice teachers.

The Scholar Academic ideology proposes that, over the centuries, our culture has accumulated important knowledge that has been organized into academic disciplines. Therefore, the purpose of education is for students to learn that valuable knowledge. According to this ideology, teachers should be mini-scholars with a deep knowledge of the discipline to be transmitted to the students. The Learner Centered ideology, on the other hand, focuses on the needs and interests of individuals.Thus, schools should be pleasant spaces where students develop naturally according to their innate nature. The purpose of education is the growth of individuals in harmony with their unique personal attributes (SCHIRO, 2013).

The Social Reconstructionist ideology advocates awareness of social problems and injustices. It assumes that the purpose of education is to facilitate the construction of a more just society; therefore, the curriculum is seen from a perspective of social transformation and education is seen as the social process through which society can be improved. In contrast, the Social Efficiency ideology states that the purpose of education is to meet the needs of society in an efficient manner. Through education, young people become mature, constructive members of society; they achieve a good education when they learn to perform the functions necessary for social productivity (SCHIRO, 2013). Together, the four major ideologies help us to understand the possible spectrum of views that educators may have on curriculum and its implementation. Precisely because of the focus of the study, this framework is key to investigate the curricular ideologies of preservice teachers.

It is also necessary to recognize that any manifestation of curricular ideologies arises in a more global framework where the curriculum is seen as a space for dispute among interest groups. Apple (2019) and others (e.g. GIMENO et al., 2010) have provided the analysis of ideological reproduction, highlighting the influence that a dominant ideology has on the system and its actors. Thus, along with exploring various ideologies, a fundamental question is: what is the most valuable knowledge? (APPLE, 2019). This is a key question since it is inherently ideological and political, historically linked to conflicts of class, race, gender, religion, etc., contributing to the exploration of linkages between ideology and conceptions of diversity and justice.

INITIAL TEACHER EDUCATION FOR DIVERSITY AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

The background on inequality in Chile was recently ratified with the report of the United Nations Development Program (PNUD, 2017) which highlights the challenges for schools and their actors, for society and its institutions. The report explains how socioeconomic inequalities are very clearly related to the treatment and value of people in everyday interactions, with a correlation between the challenges of cultural diversity and the search for justice in the classroom. Therefore, we developed both themes.

Diversity. A foundational reference for dealing with social and cultural diversity is that of Multicultural Education. Banks & Banks (2016) defined it as a conceptual framework, reform movement, and process that involves the idea that all students - regardless of gender, social class, ethnic, racial or cultural characteristics - should have equal learning opportunities. Sleeter and Grant (2011) assert that Multicultural Education includes attention to racial or cultural diversity, gender, social class, and aspects related to immigration and bilingualism. Accordingly, the focus should be on the various forms of difference that define unequal positions of power. Therefore, it is not only a multicultural approach, but also a social reconstructionist one that deals directly with oppression and structural inequality. Although there are differences with other authors (e.g. BENNETT, 2001; NIETO, 2004), all converge that social justice is at the base.

Derived from Multicultural Education, the Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (CRP) framework seeks to challenge and reject all forms of discrimination, accepting and affirming the broad spectrum of cultural pluralism of students and their communities. Gay (2018) describes it as a different and necessary pedagogical paradigm to improve the performance of students from different ethnic groups, teaching through their personal and cultural strengths, their intellectual capacities, and their prior achievements. Ladson-Billings (2009) describes it as a pedagogy that empowers students intellectually, socially, emotionally, and politically by using their cultural references. She highlights three essential principles of CRP: academic achievement (focus on learning), cultural competence, and sociopolitical consciousness.

Recent conceptualizations (e.g. PARIS, 2012; PARIS; ALIM, 2017; PEÑA-SANDOVAL, 2017), propose to replace the notion of cultural relevance by that of “sustaining” pedagogy (Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy, CSP) in the sense of enriching the approach with new research on linguistic diversity, forms of literacy, and other community cultural practices. This renewed approach seeks to value and sustain multi-ethnic and multilingual societies in a globalized world, embodying research and practice in the tradition of assets pedagogy, as well as promoting and sustaining cultural pluralism for a democratic school.

Social Justice. Recognizing that this term has a history and development in the philosophical tradition, here we focus on contemporary perspectives in education and, more particularly, in initial teacher education. In the contemporary debate on “social justice”, we highlight Nancy Fraser (USA) and Alex Honneth (Germany) whose approaches have implications for education. In Fraser (2006), we stress the concepts of redistribution and recognition, arguing that, unlike conceiving them in a false antithesis, they are elements that contribute jointly (two-dimensionality) to achieve justice. Honneth (2006), in turn, develops the idea of social justice based on a normative social theory that is based on reciprocal recognition for personal identity formation.

In the educational context, Fraser’s (2006) position has implications in the sense that the school classroom should be a space with intersubjective conditions (social and pedagogical) that allow every student to participate on equal terms with their peers and teachers. Following Honneth (2006), the implications are related to the search for development and the realization of human autonomy at school. These transformative proposals - relevant for an unequal education system such as Chile’s - are complemented by Crahay’s (2003) notion of justice for whom education systems are just when they treat all students as equals and seek an equitable society where essential goods are also distributed according to rules of justice.

In line with the aforementioned principles, we highlight a number of efforts directed at the school context and the IDF. Carlisle et al. (2006), define education for social justice “as the conscious and reflective combination of content and processes aimed at improving equity in groups with multiple social identities, fostering critical perspectives and promoting social action” (p. 57). In the context of ITEd, Cochran-Smith, Shakman, Jong, Terrell, Barnatt and McQuillan (2009) highlight the notion of “good and just teaching” based on their research with a justice orientation. In their view, future teachers internalize the concept of social justice and apply it in their practices. To fill the apparent gap in meaning of ITEd for Social Justice, Cochran-Smith et al. (2009) emphasize that it is not mere rhetoric, but a perspective with a focus on learning, where the improvement of students’ learning and life opportunities are key concerns.

Key elements in the preparation of future teachers guided by social justice are: subject- -matter mastery, pedagogical content knowledge, and knowledge of teaching methods and strategies. Moreover, the theoretical frameworks of interpretation, the social, intellectual and organizational aspects that prepare them to perform in diverse school settings must be added (COCHRAN-SMITH et al., 2009). Therefore, the quality of ITEd for social justice is not only played in specific courses and must incorporate more democratic and collaborative practices with communities (ZEICHNER, 2018), which is the responsibility of the entire ITEd curriculum.

In the Spanish-American context, the need for a more just education in a context of deepening socio-economic inequalities is stressed (e.g., BELAVI; MURILLO, 2016; MURILLO et al. 2011; PEÑA-SANDOVAL; MONTECINOS, 2016, PEÑA-SANDOVAL, 2019). In addition to emphasizing the concepts of educational equity, equal opportunities, human rights and attention to diversity, they emphasize that the school that aspires to social justice should seek to ensure that everyone learns, achieves full development and where democracy and the appreciation of cultural diversity are essential goals.

To respond to local context needs, Sleeter et al. (2016) reviewed the extensive international literature and grounded their analysis in the Chilean reality. They proposed follow four essential principles for a justice-oriented ITEd:

to place families and communities within an analysis of structural inequalities;

develop relationships of reciprocity with students, families and communities;

teaching with high academic expectations of students, capitalizing on their culture, language, experience and identity; and

developing and teaching a curriculum that integrates marginalized perspectives and explicitly addresses issues of equity and power.

To summarize, there is a certain consensus that ITEd’s task must be infused with principles of justice, affirming and sustaining cultural diversity, being the responsibility of ITEd programs as a whole. Therefore, it is highly relevant to investigate which are the ideologies that future teachers develop and/or deepen during their preparation and what conceptions about diversity and justice take place in those educational spaces.

METHODS

Consistent with the research problem and the question posed, our study is inserted within the qualitative research paradigm (RUIZ-OLABUÉNAGA, 2012), therefore it has an interpretative nature. This methodology is relevant because our aim is to understand, describe and explain phenomena “from within” (FLICK, 2015), capturing the phenomenon of study from the perspective of those who live it.

This is a case study because the research problem calls for an in-depth description and analysis of a system with clear boundaries (MERRIAM, 2009). The case is made up of preservice teachers from different ITEd programs (disciplines) in a Chilean university; following Stake’s (2005) definition, this constitutes the unit of study. Thus, the case is determined by the unit of analysis and not by the research topic, since the most defining characteristic of research lies in delimiting the object of study.

PARTICIPANTS

The universe corresponds to ITEd programs including the “Theory and Curricular Planning” course in a Chilean university. From this universe, six different programs were chosen: Early Childhood Education; Physical Education and Health; English; Mathematics; Spanish and Communication; and, History, Geography and Social Sciences. A total of 231 preservice teachers participated during first and second semesters of 2019.

Two groups of tasks were carried out: first, those related to the delivery, response and organization of data from the inventory of ideologies (SCHIRO, 2013); second, those related to the designing interview protocols and interviewing participants. The inventory consists of a reflective exercise divided into six items, each containing four sentences representing each of the ideologies outlined by Schiro (2013). Respondents were asked to mark numbers from 1 to 4, where 1 represents the statement that most identifies him/her. The exercise ends with the graphic representation of an ideological stance in a matrix. Since answering the inventory invites to a reflexive exercise, this one does not have measurement purpose, but it allows to contextualize and to know the ideological tendencies in a certain group, being part of the topics treated during interviews. The frequency and percentages of respondents to the inventory are detailed in Table 1.

TABLE 1 DISTRIBUTION OF INVENTORY RESPONDENTS BY PROGRAM

| Program | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Early Childhood Education | 31 | 13,4 |

| Physical Education and Health | 51 | 22,1 |

| English | 43 | 18,6 |

| Mathematics | 49 | 21,2 |

| Spanish and Communication | 35 | 15,2 |

| History, Geography and Social Sciences | 22 | 9,5 |

| Total | 231 | 100 |

Source: Developed by the authors.

Once the results of the inventory were known, the responses were grouped together to determine the endorsement to each one of the four ideologies. However, in addition to the four ideologies, other possibilities were observed when the tendency was not very marked or diffuse (eclectic) or when, in addition to being close to one of the ideologies, it was clearly against another (maximum level of disagreement).

After the inventory stage, we selected the participants for interviews, that is, we used an intentional sample (CRESWELL, 2014; RUIZ-OLABUÉNAGA, 2012) because we were not looking for standard case-subjects but those that offered a richness of content and significance (RUIZ- OLABUÉNAGA, 2012). Thus, we invited a group of 20 participants who showed greater clarity in their endorsement to an ideology in their inventories. Of these, ten agreed, signed their informed consent, and were interviewed (Table 2).

TABLE 2 PURPOSEFUL SAMPLE PARTICIPANTS (INTERVIEWS)

| PROGRAM | ITED PROGRAM | CURRICULUM IDEOLOGY |

|---|---|---|

| Fernanda | Early Childhood Education | Learner Centered |

| Patricia | Early Childhood Education | Eclectic |

| Tatiana | Early Childhood Education | Eclectic |

| Gustavo | English | Eclectic |

| Elizabeth | English | Learner Centered |

| Natalia | Spanish and Communication | Learner Centered |

| Pablo | Spanish and Communication | Eclectic |

| Carlos | Spanish and Communication | Learner Centered |

| Milena | Spanish and Communication | Eclectic |

| Vanessa | History, Geography and S. Sciences | Learner Centered |

Source: Developed by the authors.

Each participant was interviewed once following our protocol. The focus of these interviews was to deepen their closeness or distance to the curricular ideologies, as well as to learn their perspective on the issues of diversity and justice in education. The purpose of the interviews was to capture the natural, spontaneous, and deep flow of their perspectives, where the researcher provides input and captures the richness of the meanings (CRESWELL, 2014; STAKE, 2005). Provided with informed consents, each interview lasted 45 to 60 minutes, recorded in digital audio, and then transcribed into Microsoft Word.

DATA ANALYSIS

The data analysis was carried out by organizing the data corpus composed of the inventories and transcriptions of semi-structured interviews. The graphs of the inventories were visually analyzed to identify ideological trends according to Schiro (2013). This allowed to determine the final sample for the interviews and to visualize an overview of the ideological trends of the cohorts of each program for an even more contextualized analysis of the case. The data corpus of the interviews was stored and managed using MAXQDA 2018, which allowed us to manage and code a large volume of data.

The analyzed corpus corresponds to essentially “naturalistic” data (MERRIAM, 2009) which has a narrative or textual character. Consequently, the analysis was carried out following the recommendation of the Grounded Theory (STRAUSS; CORBIN, 1998), using first an open coding and then an analytical coding to recognize salient elements and raise categories. The iterative contrast between inventories and interviews made it possible to deepen the aspects that contributed to answer our research question.

The validity of the analyses and conclusions of the study were sought through the rigor of the data collection and analysis processes, with systematization and the search for clear patterns. Information was triangulated through data collection techniques, verification via subjects, and contrast with theory, for the saturation of the symbolic universe (MERRIAM, 2009). Regarding ethical considerations, we follow Kvale (2011) who warns to safeguard confidentiality, information on procedures (consents), and the freedom to withdraw from the study at any time.

FINDINGS

First, we present the findings referring to the curricular ideologies to which preservice teachers adhere; then, those related to the relationship between participants’ ideologies and conceptions of diversity and justice. Thus, we divide this section into four sections: the first is based on the results of the inventory; the following two sections delve into ideological trends based on interviews; and, the fourth section, which considers inventories and interviews, explores the above-mentioned relationship. The results of these last three sections are organized on the basis of three categories of analysis constructed during the process of analytical coding: anti-academicism, ideological eclecticism, and discursive coherence.

IDEOLOGICAL OVERVIEW

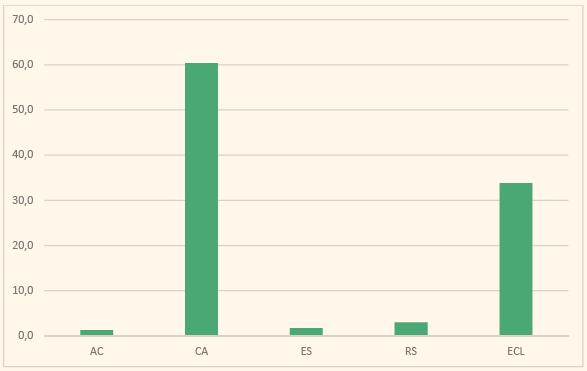

As Table 3 shows, of the 231 respondents, the predominant ideology was the Learner Centered one (60.2%). In each of the 139 inventories that represent this proportion, there is a clear adherence to this ideology, far from the Scholar Academic (1.3%), the Social Efficiency (1.7%), and the Social Reconstruction (3%) ideologies. However, it is worth noting that 33.8% corresponds to what we have called ideological eclecticism. That is, 78 of the 231 respondents did not manifest clear adherence to any ideology, but fluctuated between the different ideologies, depending on the educational topic involved.

TABLE 3 DISTRIBUTION OF CURRICULUM IDEOLOGIES IN INVENTORIES

| Curricular Ideology | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Scholar Academic | 3 | 1,3 |

| Learner Centered | 139 | 60,2 |

| Social Efficiency | 4 | 1,7 |

| Social Reconstructionism | 7 | 3,0 |

| Eclecticism | 78 | 33,8 |

| Total | 231 | 100 |

Source: Developed by the authors.

Another finding derived from the inventories is that a significant group adheres to the Learner Centered ideology along with a marked rejection of the Scholar Academic ideology. In addition, 50% of those who identify with the Social Efficiency ideology also strongly reject the Scholar Academic claims. Of the total of 231 inventories, over 10% correspond to participants who, regardless of their ideology or eclecticism, reject any manifestation of the Scholar Academic perspective.

This is noteworthy because adhering to a certain ideology does not necessarily presuppose a clear rejection of another. For example, in many cases, those who express a stance centered on learning distribute the rest of their responses among the other three ideologies, without a marked rejection. However, here we identify a group that, in addition to privileging learner- -centered statements, manifests extreme distance from scholar academic claims, which we have categorized as anti-academicism. Thus, anti-academicism represents a deep conviction with respect to privileging any approach that puts the learning subject at the center, while totally rejecting the manifestations of the traditional, teacher-centered approach. This ideological position expressed in the inventories is reaffirmed when analyzing the interviews.

AGAINST ACADEMICISM

In analyzing interviews, we found a series of statements that help to deepen and clarify the curricular perspectives expressed in inventories. In fact, whether through their own school experiences r the criticisms developed throughout university education, the preservice teachers explain how their position regarding Scholar Academic tradition has evolved. Fernanda (Early Childhood Education), for example, recalls her school experience:

Most of the teachers played the role of transmitting information, very few helped you develop as a person and very few helped you really learn. [There] you can tell that the teacher is on top and the student is at the bottom, and it shouldn’t be like that. And I feel that when we grow up [at the university] we still focus too much on the instructor.

The development of a Learner-Centered ideology, together with the anti-academicist emphasis, suggests a construction based on one’s own biography marked by the transmissive approach. At the same time, certain experiences of university education promote a focus on those who learn through learning-centered strategies. This can be seen, for example, in the case of Elizabeth (English), for whom the Scholar Academic heritage is beginning to revert in the university:

My English teacher at school was not very pedagogical or dynamic, so I learned the old-fashioned way. But here [at the university] they have taught us a lot about how to differentiate diverse approaches. She was always the center of the class, we did fill in exercises [phrases]... grammar was the focus of all her classes. And when we wanted to do something much more communicative, play, or sing or dialogue, she always minimized us, and I was very affected by that.

However, although it is hoped that university teacher education will contribute to a more didactic approach, supporting the evolution of curriculum ideologies (SCHIRO, 2013), other accounts reveal that certain spaces (disciplinary institutes) deepen the Scholar Academic approach that many want to reverse. Carlos (Spanish and Communication) highlights this, as he was previously a student at the Institute of History, so he can make a contrast and reflect on his ideological evolution accordingly:

In the History institute’s classes, it’s usually the professor who does the talking. The students are silent and the professor talks and talks [...] Many professors have no pedagogical education and have only gone through master’s and then doctoral studies. I’m not saying that’s bad, but for someone who’s going to be a teacher later on, it’s not the best option. [In History] you arrive at the classroom, sit down and listen to the professor speak. You get used to sitting and listening to professors and then having a test, and that’s it.

Thus, the analysis of the interviews allowed us to connect the development or evolution of an ideology with the school biography or university experience. While there are individuals who deploy their ideology in accordance with or in contrast to their schooling, there are also individuals who show a recent evolution according to the impact that their discipline and/or their university professors have had on their preparation.

ECLECTICISM AND IDEOLOGICAL DYNAMISM

Although this study has identified a predominance of the Learner Centered ideology, the analysis of the interviews allowed us to deepen and contrast with the inventory, revealing apparently contradictory elements. Unlike some individuals expressed anti-academicism, others referred to the teaching role in accordance with the Scholar Academic approach (erudition of teachers) or used a language of Social Efficiency. For example, Pablo (Spanish and Communication) stated:

I feel that knowledge is super important. Although it has been demonized when the teacher is the one who transmits the knowledge, I think the teacher must know a lot about the subject. I, for example, know a lot about Spanish, literature, grammar, and the student doesn’t have that knowledge, but I know he/she can acquire it. [...] I don’t think we should focus only on the student or only on the teacher, I think both are relevant to make it more productive. (the underlining is ours)

This shows that, although, in general, it is possible to adhere to the Learner Centered ideology, it does not necessarily occur “in a pure form” but coexists with a discourse permeated by the Scholar Academic tradition (transmission, acquisition) and/or by an efficiency language (productivity). Eclecticism also shows its nuances when participants, although they do not show such marked positions, reveal the coexistence of ideologies by reflecting on their responses. Natalia (Spanish and Communication) pointed out that:

In some options [of the inventory] I didn’t mark anything very strong, but there are things that I agree with. For example, with the Scholar Academic I don’t agree very much with the objectives, but I do agree that the teacher should be an expert in his or her subject. I think that once you manage your subject in an excellent manner, you are not going to be concerned with reviewing to teach. So, I think that’s going to help to focus on learning. (the underlining is ours)

This exemplifies the ideological eclecticism (SCHIRO, 2013) that does not necessarily is reflected in a contradictory discourse, but it reveals the impact of basic disciplinary education. On the basis of this conviction, a constructivist account is constructed that reflects the pedagogical instruction received recently. Thus, the preservice teacher seems to seek a balance that makes sense within the framework of his or her process of “becoming” a teacher.

Another look at the nuances of eclecticism emerges from Vanessa’s speech (History), which recognizes a dynamic process of transition between a previous academic vision and a more didactic one at present:

In the beginning I conceived the History class as a mere transmission of knowledge, because that’s how I was taught all the time, until a teacher came along who turned my way of conceiving History as a subject. Then, I said to myself “I don’t want to be that typical teacher who writes on the blackboard and passes the slide”. So, now during our student teaching practice, we adapted the classroom, we adapted the context, and we always took into consideration the different skills and talents of the students. (the underlining is ours)

This last account allows us to speculate on factors that constitute ideological eclecticism at a given time. In other words, the dynamic nature of adherence to an ideology also responds to the impact of experience. On the one hand, there are personal experiences that consolidate positions or trigger changes; on the other hand, there are practical experiences in the university’s context, courses, and student teaching, which are gradual throughout teacher education. Carlos (Spanish and Communication) exemplifies this as follows:

Now, being a student teacher, the pedagogical questions were awakened in me, because in the initial stage of the practicum and with few teaching courses I did not consider it enough [...] The experience in the classroom, working with children with family problems, I don’t know, I see the discordance between what we are taught and everything that we are going to do in the classroom and that is not learned in the university.

The practicum in schools - added to university teacher education - is a source of change of previous conceptions and favors the development of new perspectives, both because of the contact with students and because of the need to design, implement and evaluate from the teacher’s role. However, a nuance of ideological dynamism can also be represented by the deepening of previous convictions. That is, there are changes in perspectives in the sense of strengthening certain previous beliefs. Milena (Spanish and Communication) shows that this can happen thanks to the combination of practical experiences and her participation in university political spaces:

In my student teaching, I have seen social vulnerability [...] and I think I have reinforced what I believe. What happens is that I participate in a political movement, which influences the projections I have about my profession. [...] I don’t tell students that they have to be part of a political group, but without naming it, the subject of politics comes up so that they can be aware of the reality in which they live.

On the one hand, one can appreciate the ideological dynamism in terms of the deepening of beliefs, consolidated by social and political life during university education; on the other, one can see the relationship that, in some cases, a particular ideology has with discourses and practices on social justice in education. It is precisely this linkage what we explore below.

IDEOLOGY, DIVERSITY, AND JUSTICE

The second part of our research question asked about the possible relation between curriculum ideologies and conceptions of diversity and justice. Since the Learner Centered ideology predominates in half of the interviewees, while the other half manifests an ideological eclecticism (see Table 2), we present mainly findings on the first group. However, we also refer to the “eclectic” group to a lesser extent because of the interest in its nuances. According to the category “discursive coherence”, here the results show evidence of very coherent relationships, of less coherent relationships, and of absence of relationship.

Centered on learning. In this group, the example that stands out for its coherence is Natalia (Spanish and Communication) whose inventory also shows, at a lesser degree, adherence to the Social Reconstructionism ideology. In addition, she shows coherence with her conceptions on diversity and justice, and with the teaching practices she values:

[Diversity] is a super good opportunity to open up the horizons of how we teach and what we teach, because the notion of this country’s identity is changing. [...] It’s an opportunity to start thinking outside the box, to include immigration literature, an opportunity of meeting people from different cultures and holding cultural encounters, discussions, and not just the discourse of integration.

I believe that, as teachers, we can make an impression, lead by example and show the importance of ideas like equity and justice. It is necessary to participate in community work, community service. It is the possibility of making a change where it is needed. [...] I believe that the idea of success is more related to an improvement at the community level.

Her concern with the use of culturally sensitive literature for the immigrant student population connects with the principles of cultural relevance (GAY, 2018; LADSON-BILLINGS, 2009; PARIS; ALIM, 2017) and recognition (FRASER, 2006), as well as their choice of community activities is linked to the principles of reciprocity (SLEETER; MONTECINOS; JIMÉNEZ, 2016) and collaborative practices (ZEICHNER, 2018).

To refer to less pronounced relations of coherence, we illustrate this by quoting Carlos (Spanish and Communication). Although he reflects in line with the answers in his inventory, the intensity of his reflection or connection with his practice is weaker:

I think [cultural diversity] is a challenge for us, for example, in the way we evaluate immigrant students. [But] how do we evaluate children who have been evaluated differently for 12 years, and who arrive here [Chile] and have to be evaluated in another way?

I read a sociologist who says that poverty is structural, and for many years I had the misconception that with education you can overcome the gap somewhat, but there are children who grow up in contexts where no one has ever shown them the possibility of doing anything other than what they have seen all their lives. How do we get these children out of that context? Perhaps the classroom is a good way for teachers to show them that there are other possibilities, but I think that, if their family context is negative, there is not much to do.

Despite clearly adhering to the Learner Centered ideology, Carlos does not show clear convictions about how to achieve learning nor does he reflect high expectations (SLEETER et al., 2016) on the students he met in his practicum. Moreover, the reference to his readings and students seems to weaken certain convictions and generate more doubts than certainties.

Finally, to illustrate the findings around an absent relationship, we turn to Fernanda (Early Childhood Education). Interestingly, the impossibility of finding a link between her ideology and the conceptions of diversity and justice seems to be explained by her lack of conceptual clarity. For example, she recognizes that, in spite of her adherence to Learner Centered claims and her position on inequalities in education, her conception of social justice lacks the necessary clarity:

The truth is that [justice] is a difficult concept, and every time I think about it, I reach a void in which I get too tangled up. Because it is complicated that perhaps we do not have a universal definition of justice, we all talk about justice, we have representations of justice, but in truth we do not know what it is.

We recognize how problematic it is to qualify the notion of justice as absent when the interviewee recognizes and reflects on educational inequalities. However, by recognizing a conceptual vacuum, it is also plausible to suggest a vacuum of action that risks immobility in the face of the challenges of the classroom and is not consistent with the discourse that places the learner at the center, since this discourse cannot be dissociated from its context. Certainly, the conceptual vacuum is a responsibility that should be assumed by the teacher education program and is an aspect that we will discuss below.

Ideologically eclectic. Given the variability among those who show ideological eclecticism, we do not present a representative example of the group. However, in terms of the relationship between ideologies and conceptions of diversity and justice, we note that the interviews of “the eclectics” provide accounts that make transparent what they actually think and project into their profession. That is, although their inventories show little adherence to any of Schiro’s four ideologies (2013) - particularly the Learner Centered and the Social Reconstructionist ideologies, some show clear positions on diversity and justice:

I believe that the school has a responsibility and so do the teachers. I believe that all diversities must be accepted. It’s not that you have to do something different for everyone, but if a child has visual problems, why can only he/she be given facilities to learn and not the others? Another may have problems with dyslexia. That is inclusion approach that can be established in the classroom. (Tatiana, Early Childhood Education)

In my intermediate stage of practicum, I learned a lot more than in the initial one and I had a very direct mentor teacher [...] She defended students and always said things like “here there will be no bullying, here women will be treated well, and men will be treated equally, no matter the sexuality, no matter the gender, etc.” and I feel that I should do the same, it is one of the basic ways to create a safe classroom. I liked that a lot from that teacher. (Gustavo, English)

Both Tatiana’s and Gustavo’s quotes reflect important convictions associated with dealing with diversity and a focus on justice. Although in the first case the notion of diversity is associated almost exclusively with Special Needs - without considering cultural diversity, its conception stands out in terms of equal treatment, recognition, and the responsibility of the educational institution to the needs of students (CRAHAY, 2003; FRASER, 2006; SLEETER; MONTECINOS; JIMÉNEZ, 2016). Consequently, their ideological eclecticism does not rule out a particular conviction about diversity and justice in the school. Gustavo, being “eclectic”, highlights the development and consolidation of a position regarding equal treatment, respect and recognition of difference (FRASER, 2006) fostered by the practice and presence of a model to follow.

Finally, we reiterate the relevance of personal biography and personal experiences in order to understand the evolution of ideologies and conceptions. To illustrate, we quote Patricia (Early Childhood Education) who has shown an ideological eclecticism in the inventory, but has clear convictions about diversity while she evokes personal and family experiences:

There are schools and teachers who say that you have to be inclusive, but they are not [...] For example, I have Asperger’s and once I spoke with the school principal and she told me “what you have is not Asperger’s, it’s a trick”, that marked me very strongly.

Lately, there has been a lot of attack on homosexual people and our education system is still closed-minded. For example, my sister is a lesbian, and a person from Chemistry told her, “You are XX, not XY, that is, you are a woman and you have to like men”. And that’s not right. You have to teach children that everyone has the same right, that we are all equal, no matter whether you like a man or a woman.

Although Patricia’s first excerpt repeats the association between diversity and Special Needs, it highlights her conviction and clarity on the subject. That conviction also appears in relation to the need to educate in the just treatment of sexual diversity (second excerpt), both statements being a sign that, despite the eclecticism in other issues, there are clear convictions about diversity and justice that are less linked to an ideology and more to personal biography. Such convictions are closely related to the principles of multicultural education that is social reconstructionist (e.g. SLEETER; GRANT, 2011) and the social justice orientation represented by recognition (FRASER, 2006; HONNETH, 2006).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Given that the findings reveal the Learner Centered ideology as predominant among the participants and that, in addition, ideological eclecticism stands out in a significant proportion, it is necessary to discuss how ideological endorsements are expressed, the nuances of the links with conceptions of diversity and justice, and the implications this has for future research and ITEd.

First, the predominance of the Learner Centered ideology suggests that in participant preservice teachers there is a clear prioritization of the learning individual and that, at least in the Chilean context, this would be the dominant pedagogical discourse. Since the 20th century, constructivist approaches have penetrated the educational discourses and practices of our continent, overcoming traditional academicism and maintaining its primacy. However, the results of this study reveal that, in the “post-millennial” generation, there are still Scholar Academic views regarding the role of teachers and also Scholar Efficiency regarding the social role of schools.

Considering the nuances inherent in the varying nature of ideological eclecticism (SCHIRO, 2013), the emergence of this phenomenon is interesting in itself, but even more so when it is appreciated that a certain adherence to an ideology (inventories), in many cases, does not present a clear correlation in the discourses and practices of those who are being educated for the teaching profession. Most of the participants were in advanced stages of their preparation and have had a couple of clinical teaching experiences in schools; however, conceptual ambiguities still persist that should be addressed at the beginning of the ITEd programs.

It should also be discussed how, in addition to embracing a focus on learning, some participants advocate a Scholar Academic perspective with respect to teachers’ mastery of content. This can be interpreted as contradictory, as a manifestation of ideological eclecticism, or as a valid conclusion that problematizes the arbitrary separation of ideologies, stating that it is not possible to promote learning without deep mastery of the subject. Some participants expressed a preference for academicism when it comes to teachers mastering their discipline; however, it can be argued that represents the search for balance, where mastering the discipline is a condition of possibility for the promotion of learning that discipline’s contents.

However, if one adheres to the Learner Centered ideology, it is problematic to privilege content over teaching aspects, which tends to be traditionalist rather than promoting a facilitating role for the teacher. Moreover, it is striking that the inclination towards the Scholar Academic discourse appears mostly among those who belong to secondary education programs, that is, they have a strong disciplinary background component, which would explain the scholarly discourse in the participants of English, History, and Spanish.

It is important to note that, although some participants exhibit somewhat contradictory perspectives, a transition can be seen between the centrality of content (academicism) and a broadening of the pedagogical view, particularly thanks to teacher education courses and, especially, the impact of educational experiences, whether in personal or university life. Therefore, the impact of courses and clinical experiences on ideological evolution must be a key concern for both teacher educators and researchers (ZEICHNER, 2018).

With regard to our goal concerning the relationship between ideologies and conceptions about diversity and justice, the results allow us to point out that, both in the case of clear adherence to a particular ideology or when there is eclecticism, most of the participants embrace a pedagogy that affirms diversity and promotes justice. This relationship is stronger when there is a clear adherence to the Learner Centered ideology, with certain emphasis on Social Reconstructionism. Moreover, the relationship is very strong when, beyond what is stated in the inventory, the ideology manifested in the discourses emerges from participants’ biographies or personal experiences.

On the other hand, by highlighting the importance of practical experiences, we see that they facilitate the development of a perspective that focuses on learning and with social justice orientation; however, it does not cover all the dimensions expressed in the literature reviewed. For example, participants seem to focus on the notion of equal treatment and not necessarily advance to the notion of equity, in terms of how to ensure learning for all as a result of the teaching process (CRAHAY, 2003). However, in our opinion, the discussion and/or problematization of the ideologies- -conceptions relationship must also recognize that these occur in a context of transition, that is, the experience of “becoming” a teacher. Given that participants preservice teachers, they do not have such a wide range of classroom experiences that allow them to delve into dimensions or principles of justice in terms of guaranteed learning (CRAHAY, 2003). In our view, it seems natural that, in the teacher education stage, some discourses remain generic and that conceptions are evolving, particularly when the education received is not explicit in terms of a social justice orientation.

ITEd programs and teacher educators who seek to prepare for equity and social justice must understand how the discourses (ideologies) of future teachers foster relevant dispositions in the face of diversity and inequalities. Given the growing cultural diversity and the perpetuation of school segregation, explicit and purposeful preparation on these themes is unavoidable (SLEETER; MONTECINOS; JIMÉNEZ, 2016). Furthermore, as the study shows that one’s own biography and extra--university experiences have an impact on ideology and attitudes towards diversity and injustice, the implications for revising recruitment processes and offering democratic and community experiences must be considered (COCHRAN-SMITH et al., 2009; ZEICHNER, 2018). For example, a key element may be the development of an expanded notion of diversity that is not limited to the Special Needs approach, but also incorporates sociocultural, gender, ethnic, and racial diversity, among others.

Finally, we insist on the importance of the ideological evolution process that takes place thanks to the impact of practical experiences, particularly during clinical experiences during the practicum. This is a key element, since it explains the ideological eclecticism of a large part of the participants when they respond to the inventory, but who then move on to Learner Centered and Social Reconstructionist views thanks to the gradual involvement in schools. Therefore, the curriculum ideologies to which they adhere at any given time will be continuously developing visions (SCHIRO, 2013). This has implications for research and teacher education. In research, it is necessary to consider the moment (pre and post practical experiences) and the necessary follow--up to understand ideological evolution. In ITEd programs, the impact of practices and the type of practicum and school placements offered is crucial. If a program declares the affirmation of diversity and a social justice perspective, it must offer a curriculum and practical preparation in accordance with this vision; otherwise, it remains in the discourse.

REFERENCIAS

APPLE, Michael. Ideology and curriculum. 4. ed. New York: Routledge, 2019. [ Links ]

BANKS, James; BANKS, Cherry. Multicultural education: issues and perspectives. 9. ed. Hoboken: Wiley, 2016. [ Links ]

BELAVI, Guillermina; MURILLO, Francisco Javier. Educación, democracia y justicia social. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social, Madrid, v. 5, n. 1, p. 13-34, jun. 2016. [ Links ]

BENNET, Christine. Genres of research in multicultural education. Review of Educational Research, v. 71, n. 2, p. 171-217, 2001. DOI: 10.3102/00346543071002171 [ Links ]

BOBBITT, Franklin. The curriculum. United States: Nabu, 1918. [ Links ]

CARLISLE, Lenore Reilly; JACKSON, Bailey; GEORGE, Alison. Principles of social justice education: the social justice education in school’s project. Equity & Excellence in Education, Massachusetts, v. 39, n. 1, p. 55-64, Feb. 2006. DOI: 10.1080/10665680500478809 [ Links ]

COCHRAN-SMITH, Marilyn; SHAKMAN, Karen; JONG, Cindy; TERRELL, Dianna; BARNATT, Joan; MCQUILLAN, Patrick. Good and just teaching: the case for social justice in teacher education. American Journal of Education, Chicago, v. 115, n. 3, p. 347-377, May 2009. [ Links ]

CRAHAY, M. Groupe Européen de Recherche sur l’Équité des Systèmes Educatifs. L’équité des systèmes éducatifs européens: un ensemble d’indicateurs. 2003. Disponible en: http://afecinfo.free.fr/afec/documents/Indicateurs_equite.pdf. Acceso en: 20 dic. 2019. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, John. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 4. ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2014. [ Links ]

DÍAZ BARRIGA, Frida. Aproximaciones metodológicas al diseño curricular hacia una propuesta integral. Tecnología y Comunicación Educativas, México, n. 21, p. 19-39, 1993. [ Links ]

FERNÁNDEZ, María Paz. Mapa del estudiantado extranjero en el sistema escolar chileno (2015-2017). Santiago de Chile: Centro de Estudios Ministerio de Educación, 2018. [ Links ]

FLICK, Uwe. Introducing research methodology: a beginner’s guide to doing a research project. Los Angeles: Sage, 2015. [ Links ]

FRASER, Nancy. La justicia social en la era de la política de la identidad: redistribución, reconocimiento y participación. In: HONNETH, A.; FRASER, N. ¿Redistribución o reconocimiento? Un debate político-filosófico. Madrid: Morata, 2006. p. 13-88. [ Links ]

GAY, Geneva. Culturally responsive teaching: theory, research, and practice. 3. ed. New York: Teachers College, 2018. [ Links ]

GIMENO, José; FERNÁNDEZ, Mariano; TORRES, Jurjo; RODRÍGUEZ, Carmen; GONZÁLEZ, Miguel; PÉREZ, Justa. Saberes e incertidumbres sobre el currículum. Madrid: Morata, 2010. [ Links ]

HONNETH, Alex. Reconocimiento y justicia social. In: HONNETH, A.; FRASER, N. ¿Redistribución o reconocimiento?Un debate político-filosófico. Madrid: Morata, 2006. p. 126-148. [ Links ]

JIMÉNEZ-VARGAS, Felipe; MONTECINOS-SANHUEZA, Carmen. Polifonía en educación multicultural: enfoques académicos sobre diversidad y escuela. Magis, Revista Internacional de Investigación en Educación, Bogotá, v. 12, n. 24, p. 105-128, mar. 2019. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.m12-24.peme [ Links ]

KEMMIS, Stephen; FITZCLARENCE, Lindsay; MANZANO, Pablo. El curriculum: más allá de la teoría de la reproducción. 4. ed. Madrid: Morata, 2008. [ Links ]

KVALE, Steinar. Las entrevistas en investigación cualitativa. Madrid: Morata, 2011. [ Links ]

LADSON-BILLINGS, Gloria. Culturally relevant teaching. In: LADSON-BILLINGS, Gloria. The dreamkeepers: successful teachers of African American children. 2. ed. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2009. p. 102-126. [ Links ]

MERRIAM, Sharan. Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2009. [ Links ]

MURILLO, Francisco Javier; HERNÁNDEZ-CASTILLA, Reyes. Hacia un concepto de justicia social. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, Madrid, v. 9, n. 4, p. 7-23, oct. 2011. [ Links ]

NIETO, Sonia. Affirming diversity: the sociopolitical context of multicultural education. 4. ed. New York, NY: Allyn & Bacon, 2004. [ Links ]

PARIS, Django. Culturally sustaining pedagogy: a needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, California, v. 41, n. 3, p. 93-97, Apr. 2012. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12441244 [ Links ]

PARIS, Django; ALIM, H. Samy. Culturally sustaining pedagogies: teaching and learning for justice in a changing world. New York: Teachers College, 2017. [ Links ]

PEÑA-SANDOVAL, César. The remix of culturally relevant pedagogy: pertinence, possibilities, and adaptations for the Chilean context. Perspectiva Educacional, v. 56, n. 1, p. 109-126, 2017. DOI: 10.4151/07189729-Vol.56-Iss.1-Art.462 [ Links ]

PEÑA-SANDOVAL, César. Advancing culturally relevant pedagogy in teacher education from a Chilean perspective: a multi-case study of secondary preservice teachers. Multicultural Education Review, South Korea, v. 11, n. 1, p. 1-19, Jan. 2019. DOI: 10.1080/2005615X.2019.1567093 [ Links ]

PEÑA-SANDOVAL, César; MONTECINOS, Carmen. Formación inicial docente desde una perspectiva de justicia social: una aproximación teórica. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social, Madrid, v. 5, n. 2, p. 71-86, nov. 2016. [ Links ]

PROGRAMA DE LAS NACIONES UNIDAS PARA EL DESARROLLO (PNUD). Desiguales: orígenes, cambios y desafíos de la brecha social en Chile. Santiago de Chile: Uqbar, 2017. [ Links ]

RUIZ-OLABUÉNAGA, José Ignacio. Metodología de la investigación cualitativa. Bilbao: Universidad de Deusto, 2012. [ Links ]

SANZ CABRERA, Teresa. El curriculum: su conceptualización. In: GONZÁLEZ PÉREZ, M.; HERNÁNDEZ DÍAZ, A.; HERNÁNDEZ FERNÁNDEZ, H.; SANZ CABRERA, T. Currículo y formación profesional: Instituto Superior Politécnico “José Antonio Echeverría”. Habana: Editorial Universitaria, 2003. p. 125-136. [ Links ]

SCHIRO, Michael. Curriculum theory: conflicting visions and enduring concerns. 2. ed. Los Angeles: Sage, 2013. [ Links ]

SLEETER, Christine; GRANT, Carl. Educación que es multicultural y reconstructivista social. In: WILLIAMSON, G.; MONTECINOS, C. (ed.). Educación multicultural: práctica de la equidad y diversidad para un mundo que demanda esperanza. Temuco: Universidad de La Frontera, 2011. p. 43-72. [ Links ]

SLEETER, Christine; MONTECINOS, Carmen; JIMÉNEZ, Felipe. Preparing teachers for social justice in the context of education policies that deepen class segregation in schools: the case of Chile. In: LAMPERT, J.; BURNETT, B. (ed.). Teacher education for high poverty schools. Switzerland: Springer, Cham, 2016. p. 171-191. [ Links ]

STAKE, Robert. E. Multicase research methods: step by step cross-case analysis. New York: Guilford, 2005. [ Links ]

STENHOUSE, Lawrence. Investigación y desarrollo del currículum. Madrid: Morata, 1984. [ Links ]

STRAUSS, Anselm; CORBIN, Juliet. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2. ed. London: Sage, 1998. [ Links ]

TYLER, Ralph. Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984. [ Links ]

VENEGAS, Cristián. Hacia la innovación en la formación inicial docente para un desempeño exitoso en contextos alta vulnerabilidad social y educativa. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, Concepción, v. 12, n. 23, p. 47-59, ene./jul. 2013. [ Links ]

ZEICHNER, Kenneth M. Struggle for the soul of teacher education. New York: Routledge, 2018. [ Links ]

Received: January 22, 2020; Accepted: July 14, 2020

texto en

texto en