Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 0100-1574versão On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.50 no.178 São Paulo out./dez 2020 Epub 23-Nov-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/198053147161

ARTICLES

HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION: THE PERCEPTION OF UNICAMP PROFESSORS

IUniversidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas (SP), Brazil; dibbern.thais@gmail.com

IIUniversidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas (SP), Brazil; milenaps@unicamp.br

This article aims to describe and analyze the perception of professors at the University of Campinas (Unicamp) in relation to the subject of human rights education (HRE) at the university level. Methodologically, this research was carried out by submitting a survey to professors at the University who presented productions and/or extension practices in the thematic area; then, after the analysis performed, we will present the results achieved through this. The following can be highlighted: about 80% of respondents indicated that there are barriers to the development of research and extension practices in human rights at Unicamp; it was possible to observe an agreement in relation to the consideration of HRE as one of the social commitments to be assumed by the University.

Key words: HUMAN RIGHTS; EDUCATION; HIGHER EDUCATION; UNIVERSITY

Este artigo tem como objetivo descrever e analisar a percepção de docentes da Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp) em relação à temática da educação em direitos humanos (EDH) no âmbito universitário. Metodologicamente, a pesquisa foi realizada por meio da submissão de um questionário aos docentes da Universidade que apresentaram produções e/ou práticas extensionistas na área temática. Na análise dos resultados alcançados, pode-se destacar que cerca de 80% dos respondentes indicaram haver entraves no desenvolvimento de pesquisas e práticas extensionistas em direitos humanos na Unicamp. Também foi possível observar uma concordância em relação à consideração da EDH enquanto um dos compromissos sociais a ser assumido pela Universidade.

Palavras-Chave: DIREITOS HUMANOS; EDUCAÇÃO; ENSINO SUPERIOR; UNIVERSIDADE

Este artículo tiene como objetivo describir y analizar la percepción de los profesores de la Universidad Estatal de Campinas (Unicamp) en relación con el tema de la educación en derechos humanos a nivel universitario. Metodológicamente, esta investigación se realizó mediante el envío de un cuestionario a los profesores de la Universidad que presentaron producciones y/o prácticas de extensión en el área temática; luego, después del análisis realizado, presentaremos los resultados logrados a través de esto. Se puede resaltar lo siguiente: alrededor del 80% de los encuestados indicaron que existen barreras para el desarrollo de prácticas de investigación y extensión en derechos humanos en la Unicamp; fue posible observar un acuerdo en relación con la consideración de EDH como uno de los compromisos sociales a asumir por la Universidad.

Palabras-clave: DERECHOS HUMANOS; EDUCACIÓN; ENSEÑANZA SUPERIOR; UNIVERSIDAD

Cet article vise à décrire et à analyser la perception des professeurs de l’Université Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp) sur l’éducation aux droits de l’homme a l’université. Méthodologiquement, un questionnaire a été soumis aux professeurs de l’Université qui avaient des productions et des pratiques de vulgarisation dans ce domaine. L’analyse met en évidence les résultats suivants: environ 80% des interrogés ont indiqué qu’il existe des obstacles au développement de pratiques de recherche et de vulgarisation en matière de droits de l’homme à Unicamp et aussi un accord concernant la prise en compte de l’EDH comme l’un des engagements sociaux que l’université devrait assumer.

Key words: DROITS DE L’HOMME; ÉDUCATION; ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR; UNIVERSITÉ

This article seeks to describe and analyze the perception of professors at the University of Campinas (Unicamp) in relation to the theme of human rights and human rights education at the university level. In view of this, the article is structured in two parts, in addition to this introduction and concluding remarks. In the first part, some methodological and analytical considerations are made about how the research was carried out, with a view to sending an online survey to Unicamp professors who presented productions and/or extension practices in the thematic area addressed; then, the main results obtained are described and analyzed.

In this regard, this article starts from the recognition of the social importance of the public university as a generator of a culture in human rights, since, as Dias Sobrinho (2014, p. 657, own translation) points out, “it is only worthy to be named a university institution that produces and disseminates knowledge as a social right and a public good, that is, as something essential and indispensable to the formation of subjects capable of participating creatively and critically in society”. In other words, it is assumed that higher education institutions (HEIs), especially public universities, have a privileged space, as they can contribute to the production and dissemination of knowledge for human development through the incorporation of the principle’s basic human rights in teaching, research and extension projects. Human rights education (HRE), incorporated in a transversal and interdisciplinary way, aims to contribute to a training that goes beyond the labor market, constituting, at the same time, one of the ways the university fulfills its social commitment.

According to the National Human Rights Education Plan (BRASIL, 2007), the pillars of the university must be aligned with its educational, social and institutional mission. Therefore, it is understood that their commitment must be linked to social demands, creating, disseminating and articulating academic and popular knowledge, in order to enable social transformations from a critical and citizen formation, assisting and guiding collective actions. In this sense, the university should not have a strictly utilitarian character, “giving up” its autonomy, its way of organization and purposes. However, this new paradigm reflects the subordination and submission that higher education has adopted in relation to scientific and technological production favorable to the market, legitimizing the utilitarian view of knowledge (DIAS SOBRINHO, 2013, 2014, 2015).

Thus, HRE must be understood as an educational practice, which aims to intervene in the training of people in all its dimensions, cooperating for their development as citizens and, at the same time, contributing to the recognition of their rights and duties (TAVARES, 2010). With regard to its formative aspect, Magendzo (2006) highlights that this practice starts from the recognition of historical, political and social dimensions of education itself; in practical terms, it is about the incorporation of human rights principles in teaching, research and extension methodologies and practices, as well as in the areas of administrative management and community living.

This right, therefore, is confirmed in several official documents of the Brazilian federal government, as well as in other regulations of the International and Inter-American Human Rights System. Among these we can highlight the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training (ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS - UN, 2011) and the second phase of the World Program for Education in Human Rights (ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS FOR EDUCATION, SCIENCE AND CULTURE - UNESCO, 2012), which was in force between 2010 and 2014. Such documents are emphatic regarding the commitment to be assumed by these institutions, especially within the scope of public universities and other HEIs:

Higher education institutions, through their basic functions (teaching, research and services for the community), not only have a social responsibility to train ethical citizens committed to the construction of peace, the defense of human rights and the values of democracy , but also to produce knowledge aimed at meeting current human rights challenges, such as the eradication of poverty and discrimination, post-conflict reconstruction and multicultural understanding. Therefore, the role of human rights education in higher education becomes essential. This education concerns not only the content of the curriculum, but also the educational processes, pedagogical methods and the environment in which education is present.1 (UNESCO, 2012, p. 11, own translation)

Within the Brazilian State, some documents should also be emphasized, such as the III National Human Rights Program (BRASIL, 2010) and the National Guidelines for Human Rights Education (NGHRE) (BRASIL, 2012). As for the first, special emphasis is given to its fifth axis, which explains the need for the adoption of HRE at the national, state, district and municipal levels (BRASIL, 2010). The Program proposes curricular changes, especially through the inclusion of themes such as gender and sexual orientation, as well as the recognition and appreciation of indigenous and Afro-Brazilian cultures in the scope of elementary and high school education. With regard to higher education, the program highlights, in guideline 19, “the strengthening of the principles of democracy and human rights”2 in HEIs and other educational institutions (BRASIL, 2010, p. 191, own translation). In these terms, it is recommended to incorporate the theme of HRE in courses from different areas of knowledge, based on the development of inter and transdisciplinary pedagogical methodologies; creation of lines of research and areas of concentration; university extension programs and projects; promotion of activities in the areas of teaching, research and extension through funding agencies; and encouraging continuing education, as well as graduate programs in human rights (BRASIL, 2010).

In relation to the NGHRE, these determine to higher education institutions the insertion of HRE as a guiding principle of the educational and institutional process, in order to cover the spheres of teaching, research, extension and management. Thus, such guidelines consider that, in the scope of teaching, an interdisciplinary dialogue should be drawn, in order to contemplate the various areas of knowledge, developing from a critical perspective of the curriculum through its incorporation in the pedagogical projects and other curricular activities. In research, a policy of encouraging studies and research is required, through the creation of groups and groups focusing on themes such as human rights, gender relations, violence, public security, cultural diversity, among others, in addition to organization of the collection produced. With regard to extension, it is recalled the need for these institutions to meet the demands of social segments in situations of exclusion and violation of rights, social movements and public management itself. In the scope of management, it is considered that human rights should be included in culture and organizational management, that is, this perspective must be incorporated in the scope of mediation and repair of conflicts and violations, in social interventions and in union representation, in councils, public policy committees and forums (BRASIL, 2012).

According to Rodino (2016, p. 101, own translation),

[…] in the last two decades, especially since 2000, there has been notable progress in recognizing HRE within the educational regulations of Latin American countries. To date, its institutional recognition is high. Although this phenomenon alone and automatically does not transform school practice, it is the first condition that makes any transformation possible. The progressive legitimacy of HRE (which until well into the 1990s in many countries was viewed with suspicion as dangerous), gives educators confidence to start talking about human rights, even in an incipient way, and sensitizes authorities, technicians, teachers and families regarding the value of addressing them in the classroom.3

It is evident, from this perspective, the importance of HEIs in the formation of ethical citizens and committed to the defense of human rights. Public universities, therefore, assume an important role in this matter, as they have the possibility, according to their pillars, to carry out training, research and extension in human rights, being a cognitive reference to other levels of education and other educational institutions higher. A public university is one that is committed to building citizenship and defending human rights by considering education as a public and common good. To understand and defend this is to give an account of the initial bases for structuring the broader changes that human rights education proves us today.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND METHODOLOGICAL OVERVIEW

Considering that a survey constitutes a research technique/instrument widely used in the scope of applied human and social sciences and that aims to collect information based on a set of questions sent to a representative group of individuals that provide data of interest to researchers (AMARO; PÁVOA; MACEDO, 2004; GIL, 2008), this research technique was chosen to investigate the perception of Unicamp professors in relation to human rights education in the university environment and the motivations that led them to develop such activities.

In doing so, it is worth presenting the way the survey was prepared and applied to professors at University of Campinas. First of all, the objective of the survey was defined: to analyze the perception of Unicamp professors in relation to research and extension practices in human rights and in human rights education in the university environment, as well as the motivations that led them to develop these activities and the possible barriers/challenges present in them. It is necessary to highlight that the survey was sent only to professors who presented publications and/or extension practices related to the theme of human rights and/or HRE. The search for such professors was carried out in a previous research, considering the data sources made available by the University, as well as using keywords that contemplate a diversity of human rights themes, such as: human rights education; education for peace; culture of peace; education and human rights; right to education; health rights, civil and political rights; environmental rights; diversity; gender; prejudice; discrimination; among others.

Considering analytical dimensions, the following stand out: area of knowledge; participation in research groups that address the issue of human rights; development of research in the area and themes of human rights and/or HRE; development of extension practices in these areas and themes; participation in public rights/policy councils (external to the University); existence (or not) of institutional policies to encourage research and extension in human rights; motivation for carrying out such activities; knowledge (or not) of official federal government documents related to HRE; and possible barriers/challenges in conducting research and extension practices about human rights.

According to Gil (2008), the application of survey has a number of advantages, such as: reaching a large number of people, even though they are dispersed in different geographical areas; lower personnel expenses, as it does not require training of researchers; guaranteeing the anonymity of the respondents, helping them to feel safer when presenting their opinions; possibility for individuals to respond when convenient; and, when applied at a distance, the non-exposure of respondents to possible influences by the researcher. Therefore, we visualized in this instrument the practical fit of its application, especially for reaching a large number of professors in a short period of time, in addition to ensuring their anonymity.

In addition to its advantages, Gil (2008, p. 122, own translation) highlights a series of limitations in relation to the application of this technique, such as: it excludes the participation of illiterate people; prevents the researcher from helping the respondent in case of doubts; prevents the researcher from knowing the circumstances in which it was answered; does not guarantee that all selected individuals will answer it; covers a small set of issues; and “it provides very critical results in relation to objectivity, as the items may have different meanings for each researched subject”.4 In the words of Chagas (2000, p. 2, own translation), “measurement always occurs in complex situations, where several factors influence the measured characteristics and the measurement process, which can generate non-sampling errors”.5 Such factors could be configured as personal situations that would undermine a stable response situation, as well as the lack of coherence and clarity in relation to the survey and the possible language differences between the respondent and the researcher, among others.

Thus, in its elaboration process, it is necessary to follow a set of requirements that minimize possible failures, such as: “verification of its effectiveness to verify objectives; determining the form and content of the questions; number and ordering of questions; construction of alternatives; presentation of the survey and pre-test of the survey”6 (GIL, 2008, p. 121, own translation). In fact, a series of choices must be made previously, such as defining the objectives of the research and the survey; the content of the questions, which must be consistent with the objectives; the form, sequence and ordering of the questions (open, closed and/or intensity scales); the respondent target audience (sample or population); the construction and application tool (digital format, on paper, applied via telephone, internet, personally, etc.); the possible risks, schedule and application costs; conducting tests prior to their effective application; and, after being applied, the definition of the form of analysis and description of the results obtained (CHAGAS, 2000; VIEIRA, 2009; NOGUEIRA, 2002).

In fact, despite the consideration of the dimensions mentioned above, the use of the survey required the construction of specific clippings, since not all questions were open to respondents. This is due to what Vieira (2009) and Gil (2008) emphasize when they understand the survey as techniques that have limitations regarding the types of analysis and conclusions that can be generated through the different types of questions and content included. So, for each type of question, a certain series of analytical possibilities is produced, and cannot exceed generalizations that do not match the meaning of the responses received. For this, we use some forms of open-ended questions with free answers, closed with predefined alternatives (with the possibility of choosing more than one alternative), closed with binary alternatives (yes and no) and questions with an intensity scale. Therefore, based on the consulted literature (GIL, 2008; VIEIRA, 2009; AMARO; PÁVOA; MACEDO, 2004), it was considered opportune and appropriate to carry out these types of questions.

On the other hand, questions with an intensity scale are characterized by presenting a set of sentences in which the respondents must answer by choosing a predetermined gradation of intensity, being consistent for the measurement of beliefs, opinions and attitudes (AMARO; PÁVOA; MACEDO, 2004). For this reason, in view of the existence of several types of scale, we chose to use the Likert Scale, which “consists of taking a construct and developing a set of statements related to its definition, to which the respondents will issue their degree of agreement”7 (SILVA JÚNIOR; COSTA, 2014, p. 5, own translation).

In this sense, starting with the presentation of the set of elaborated questions, we have, at first, those related to identification. However, because we value anonymity, we do not aim to identify the names and identities of the respondents, but rather the area of knowledge in which they act/acted and the institutional linkage unit, constituting themselves as closed questions with predefined options. It is necessary to highlight that some perceptions in relation to human rights and HRE in the university may differ in terms of the particularities of the great areas of knowledge. With this in mind, Chart 1 presents the construction of the survey, which was divided into three sections: the first concerns the general identification of respondents; the second relates to research activities and extension practices developed by them; and the third is aimed at identifying the respondents’ perception of the barriers/challenges of human rights and of HRE at Unicamp and other statements.

CHART 1 SURVEY APPLIED TO UNICAMP PROFESSORS

| Nº | Section 1: General identification of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Question | Description | |

| 1 | Area of knowledge that acts or acted | Closed question with predefined alternatives, with the possibility of ticking more than one alternative |

| 2 | Institution affiliated | Closed question with predefined alternatives, but with the possibility of an open answer if it does not fit the alternatives |

| 3 | Do (Did) you participate in any research center or nucleus? | Closed question with binary alternatives |

| 4 | If so for the previous question, which one? | Closed question with predefined alternatives, being conditioned to the previous question |

| Section 2: Identification of research activities and extension practices developed by respondents | ||

| 5 | Do (Did) you participate in any research group that deals directly or indirectly on any subject related to human rights? | Closed question with binary alternatives |

| 6 | During your career at Unicamp, have you developed or participated in any research that deals with the subject of human rights? | Closed question with binary alternatives |

| 7 | If so, which theme (s)? | Closed question with predefined alternatives, conditioned to the previous question (but with the possibility of an open answer if it does not fit the alternatives) |

| 8 | During your career at Unicamp, have you developed or participated in any extension practices that deal directly or indirectly with the theme of human rights? | Closed question with binary alternatives |

| 9 | If so, what was the main theme? | Open question with free answer, conditioned to the previous question |

| Nº | Section 2: Identification of research activities and extension practices developed by respondents | |

| 10 | In your institute/faculty, are there institutional policies to encourage research on human rights? | Closed question with binary alternatives |

| 11 | If there are policies, do (did) you participate in the elaboration of these actions? | Closed question with binary alternatives |

| 12 | In your institute/faculty, are there institutional policies to encourage extension practices that deal with human rights issues? | Closed question with binary alternatives |

| 13 | If there are policies, do (did) you participate in the elaboration of these actions? | Closed question with binary alternatives |

| 14 | During your career at Unicamp, have you guided/oriented undergraduate or graduate research on the subject of human rights? | Closed question with binary alternatives |

| 15 | If you develop research and / or extension practices on the theme of human rights, comment on when your interest in the topic was aroused | Closed question with predefined alternatives, conditioned to the previous question (but with the possibility of an open answer if it does not fit the alternatives) |

| 16 | Do you know the Federal Government's National Human Rights Education Plan (Brazil)? | Closed question with binary alternatives |

| 17 | If so, are you guided and/or guided through it for the development of research projects and/or extension practices? | Closed question with binary alternatives |

| 18 | Do you know the University Pact for the Promotion of Respect for Diversity, the Culture of Peace and Human Rights of the Federal Government (Brazil)? | Closed question with binary alternatives |

| Section 3: Identification of respondents' perception in relation to barriers/challenges of human rights and HRE at Unicamp and other statements | ||

| 19 | In your opinion, are there any difficulties/obstacles that hinder the development of research and/or extension practices that address the theme of human rights? Which would they be? | Open question with free answer |

| 20 | From now on, the questions aim to understand the perception of professors about human rights in higher education: What is the degree of agreement with the following statements? | Closed questions with intensity scale (Likert scale) |

Source: Author’s elaboration.

After elaborating these questions, we structured the survey through the online form creation platform, called Google Drive. Then, we collected the institutional emails of the 200 professors identified in this research,8 as well as those who participated in the University Pact Management Committee (2017-2019), sending them the survey formulated. Thus, in order to present the results obtained, we will expose the description and analysis of each question, considering its form and objective.

The survey reached a group of 200 professors, according to the criteria established by this research. However, despite having been sent by each professor’s institutional email, it is not possible to guarantee that everyone has seen the message. Thus, considering the period from October 29 to November 29, 2018, we obtained 54 responses, representing 27% of the total of professors considered. Although we did not reach all of the professors, we consider the response rate obtained to be significant, considering that, “on average, the survey sent by the researcher reach 25% return”9 (MARCONI; LAKATOS, 2003, p. 201, own translation). Therefore, although it is not possible to make generalizations in the statistical scope, we will use the answers as a starting point for the construction of hypotheses and, also, as directions to be investigated in future research. It is necessary to highlight that the present research had the approval of the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Campinas (Brazil).

PRESENTATION OF RESULTS

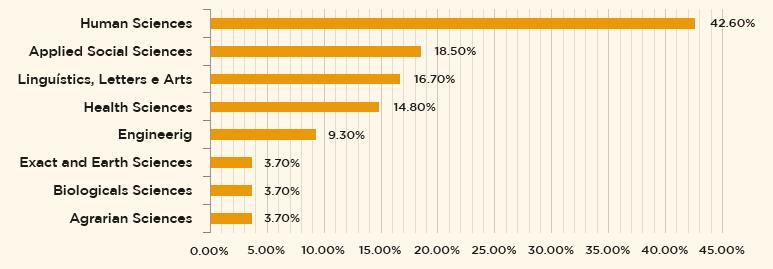

This section seeks to describe and analyze the survey submitted to Unicamp professors, starting with the data that reveal the respondents’ profile. According to the 54 survey answered and considering that professors had the option of pointing out more than one large area of knowledge, it can be seen - as shown in Figure 1 - that most of them are in the area of Human Sciences (HS), followed by Applied Social Sciences (ASS), Linguistics, Letters and Arts (LLA), Health Sciences (HES), Engineering (ENG), Exact and Earth Sciences (EES), Biological Sciences (BS) and Agrarian Sciences (AGS).

As for the institutional linkage unit, we have the following results: 16.7% (nine respondents) are from the Faculty of Applied Sciences; 13% (seven respondents) are from the Institute of Philosophy and Human Sciences; 13% (seven respondents) are allocated to the Faculty of Education; 11.1% (six respondents) belong to the Faculty of Medical Sciences; 9.3% (five respondents) are from the Institute of Arts; 9.3% (five respondents) are at the Institute of Language Studies; 5.6% (three respondents) are at the Geosciences Institute; 5.6% (three respondents) are from the Institute of Economics; and nine respondents, only one from each unit (1.9%), correspond to the Faculty of Technology, the Technical College of Limeira (Cotil), the Institute of Biology, the Faculty of Agricultural Engineering, the Faculty of Food Engineering, the Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Urbanism, the Institute of Chemistry, the Faculty of Nursing and the Dean of Extension and Culture. Therefore, we obtained the largest number of responses from professors linked to the first three units cited.

Considering all the institutes and faculties belonging to Unicamp, no answers were obtained from professors linked to the units of the Institute of Mathematics, Statistics and Scientific Computing, Institute of Computing, Institute of Physics, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Physical Education, Faculty of Dentistry of Piracicaba and Technical College Campinas (Cotuca). It is remarkable that some of these units also did not appear in the survey carried out previously, which justifies the reason why we did not obtain respondents.

Following the stage of identifying the respondents’ profile, they were asked about their participation in research centers or centers, obtaining the following results: 44.4% (24 respondents) indicated a positive answer to the question, that is, who participated in research centers or centers; 14.8% (8 respondents) mentioned that they have already participated; and 40.7% (22 respondents) indicated non-participation. Thus, considering its distribution according to the major areas of knowledge, we have that in the scope of HS, ASS, BS and AGS, most of the respondent professors indicated that they participate or have already participated in research centers or centers. For LLA, ENG and EES, there is a balance in relation to their participation. For HES, most respondents indicated a negative answer to the question, that is, they do not participate/participated in research centers or centers.

Thus, for those who answered positively, the name of the center or nucleus in which the professors participate or participated was asked, obtaining the following results: 20.7% (six respondents) in the Public Policy Studies Nucleus (Nepp); 17.2% (five respondents) at the Center for Environmental Studies and Research (Nepam); 13.8% (four respondents) at the Center for Population Studies “Elza Berquó” (Nepo); 6.9% (two respondents) at the Biomedical Engineering Center (CEB); 6.9% (two respondents) at the Creativity Development Center (Nudecri); and the aggregate of 44.2% (13 respondents, one from each center / center), at the Center for Informatics Applied to Education (NIED); Interdisciplinary Nucleus of Sound Communication (Nics); Pediatric Research Center (Ciped); Center for International Studies and Contemporary Politics (Ceipoc); Center for Union Studies and Labor Economics (Cesit); Economic Development Studies Center (Cede); Interdisciplinary Center for City Studies (Ciec); Fluxus Laboratory (Fluxus); Center for Rural Studies (Ceres); Clinical-Qualitative Research Laboratory (LPCQ); Group of Studies and Research in Continuing Education (Gepec); Research Practice Group; and the Human Rights, Democracy, Politics and Memory Research Group (USP).

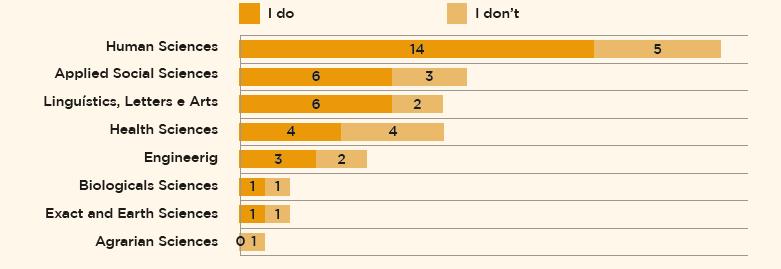

Considering the question regarding specific participation in research groups that deal directly or indirectly with any topic related to human rights, 64.8% (35 respondents) answered affirmatively and 35.2% (19 respondents) indicated that they do not participate in such groups. In view of the large areas of knowledge belonging, most of the professors of HS, ASS and HES responded positively to the question, as can be seen in Figure 2.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

FIGURE 2 PROFESSORS’ PARTICIPATION IN RESEARCH CENTERS/GROUPS ON HUMAN RIGHTS, BY MAJOR AREA OF KNOWLEDGE

So, it is observed that, in the scope of the HS, ASS and ENG, most of the respondent professors claimed to participate in research centers, and there is also an indication of participation in research groups that deal with some thematic related to rights humans. With regard to HES, only two professors indicated that he or she participated in a research center, but most respondents in this area reported participation in research groups on HR. It is also noted a balance in the scope of the LLA, EES and BS, as well as the negative answer to the question by the professor who answered the AGS.

Continuing with the presentation of the profile of the respondent professors, it was asked about the development and/or participation in research projects related to the large area of Human Rights, with the majority (75.9% or 41 respondents) answering the question affirmatively, only 24.1% (13 respondents) indicated non-development and/or participation. According to the major areas of knowledge, most respondents in all areas, except AGS, have responded positively to this question.

In this sense, for those who indicated the affirmative alternative, the issue related to the themes worked was added. It should be noted that the options in this question are constituted as analytical categories formulated for this research, and it was possible to include and/or point out more than one alternative. Within the categories considered, the results of the themes indicated were as follows: right to health (14 respondents); gender, class and race (14 respondents); right to education (13 respondents); right to the city (seven respondents); human rights, justice and memory (seven respondents); technology, production and work (six respondents); human rights and international relations (six respondents); right to the environment (five respondents); civil rights (five respondents); cultural and / or generational rights (two respondents); political rights (two respondents); secularity of the State (no respondents). When allowing the inclusion of other topics, some professors added the following: the right of people with disabilities (three respondents); access to the territory by indigenous and quilombola community (one respondent); social assistance and protection against the violation of rights (one respondent); economic and social development (one respondent); moral development and socio-moral values at school (one respondent); right to information and freedom of expression (one respondent); human right to adequate food (one respondent); humanization in mental health contexts (one respondent); school inclusion (one respondent); cognitive justice (one respondent); and interpersonal relationships at school (one respondent). Table 1 presents the results according to the major areas of knowledge. It is worth mentioning that the accounting for this table, as well as the previous figures, was performed considering only the first option selected in relation to the large area of knowledge.

TABLE 1 TOPICS OF RESEARCH PROJECTS INDICATED BY RESPONDING PROFESSORS, BY LARGE AREA OF KNOWLEDGE

| Major Area | Topics/Categories | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR and international relations | Civil rights | Political rights | Cultural and/or generational rights | HR, justice and memory | Right to the environment | Right to education | Right to health | Technology, production and work | Secular State | Right to the city | Gender, class and race | Other topics | |

| Human Sciences | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 7 |

| Applied Social Sciences | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Linguistics, Letters and Arts | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| Health Sciences | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Engineering | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Agrarian Sciences | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Biological Sciences | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Exact and Earth Sciences | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| General Total | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 13 | 14 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 14 | 13 |

Source: Author’s elaboration.

It is noted that in the areas of Human Sciences and Applied Social Sciences, a variety of themes were identified, such as “human rights and international relations”, “civil rights”, “political rights”, “cultural and/or generational rights”, “human rights, justice and memory”, “right to education”, “right to the environment”, “right to health”, “technology, production and work”, “right to the city” and “gender, class and race”. In Linguistics, Letters and Arts, the themes presented were “cultural and/or generational rights”, “human rights, justice and memory”, “right to education”, “right to the city” and “gender, class and race”. In Health Sciences, special emphasis is given to “the right to health”, “the right to education”, “human rights and international relations”, “civil rights”, “political rights”, “human rights, justice and memory”, “right to the city” and “gender, class and race”. For Engineering, Biological Sciences and Exact and Earth Sciences, the themes become a little more restricted, taking into account the “civil rights”, “right to the environment”, “right to education”, “right to health”, “technology, production and work “,” right to the city” and “gender, class and race”. As for the Agrarian Sciences, any topic was highlighted.

Within the scope of extension practices, it was also found that the majority of respondents indicated a positive answer to the question, with 70.4% (38 respondents) already developing and/or participating in extension practices in human rights and 29.6% (16 respondents) did not participate. Figure 3 shows the results according to the major areas of knowledge.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

FIGURE 3 DEVELOPMENT AND/OR PARTICIPATION OF PROFESSORS IN EXTENSIONIST PRACTICES RELATED TO THE AREA OF HUMAN RIGHTS, BY MAJOR AREA OF KNOWLEDGE

So, special emphasis is given to the HS, HES and LLA, in which a large part of the respondents indicated having developed and/or participated in extension practices whose themes are related to the HR. With regard to EES, no professor indicated a positive answer to the question and, in ASS, most indicated a negative answer, differing in relation to the research pillar.10 As for AGS, the only professor who responded in the area declared a positive answer to the question.

For those who responded positively, the main topic addressed was questioned. According to the results obtained, it is observed that, in the scope of research and extension in HR at Unicamp, there is a greater predominance of the themes like right to education, right to health and gender, class and race, and the indication of other themes can be highlighted in the scope of extension, which were not present in the sphere of research projects: care for the homeless population and the themes related to the relationship between human rights and the media. In this perspective, considering the thematic areas of university extension and in view of the National Extension Policy (Brazil), that is, the areas of “Communication, Culture, Human Rights and Justice, Education, Environment, Health, Technology and Production, and Work” (FORPROEX, 2012, p. 25, own translation), there is a convergence of themes/topics, with major emphasis on extension activities related to education and health.

With regard to the participation of professors in public rights/policy councils, human rights committees or commissions, these being external to Unicamp, 64.8% (35 respondents) declared they had never participated and 35.2% (19 respondents) claimed to have participated. This result indicates that the profile of the responding professors, in relation to participation in participatory human rights institutions, is moderate, but presents an interesting performance phenomenon, considering the sample obtained. It is worth noting, therefore, a commitment made with the University Pact, a program of the federal government, in relation to stimulating these participations within the scope of the relationship between academic and community coexistence.

As for the knowledge of professors in relation to the institutional policies to stimulate HR research at Unicamp, 42.6% (23 respondents) stated that they did not exist, 22.2% (12 respondents) pointed out the existence and 35.2% (19 respondents) indicated that they did not know how to give an opinion. Regarding their participation in the elaboration of such policies, 46.2% (18 respondents) reported not being involved, 25.6% (ten respondents) responded positively and 28.2% (11 respondents) did not know how to express their opinion.

With regard to institutional policies to encourage extension practices in HR at Unicamp, 48.1% (26 respondents) indicated that they did not exist, 24.1% (13 respondents) declared their existence and 27.8% (15 respondents) they did not know how to give their opinion. With reference to participation in the preparation of these, 51.4% (19 respondents) said they had not participated, 21.6% (8 respondents) positively indicated participation and 27% (10 respondents) did not know how to give an opinion. It is possible to say that these responses reflected within the scope of the question about the possible challenges and obstacles to conducting research and extension practices in human rights at Unicamp, which will be analyzed later.

Therefore, it appears that, despite the fact that professors develop research and/or extension activities in HR at the University, most of them are unaware of the existence of institutional policies to encourage research and university extension in this thematic area. It is also observed that, in relation to the question about institutional extension policies, most respondents indicated their inexistence, which refers to the hypothesis of the presence of difficulties and obstacles in relation to this pillar of action. In addition, there is dissonance in relation to the University Pact, as it provides for the formulation of institutional policies to promote research and extension in the area of HR. In Table 2 it is possible to identify such responses according to the areas of knowledge.

TABLE 2 ANSWERS’ QUESTIONS RELATED TO THE EXISTENCE OF INSTITUTIONAL POLICIES TO STIMULATE RESEARCH AND EXTENSION IN HR AT UNICAMP, BY MAJOR AREA OF KNOWLEDGE

| Major Areas | Policies to encourage research | Policies to encourage extension | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | I don’t know | Yes | No | I don’t know | |

| Human Sciences | 3 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 6 |

| Applied Social Sciences | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Linguistics, Letters and Arts | 5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Health Sciences | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

| Engineering | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Agrarian Sciences | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - |

| Biological Sciences | - | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 |

| Exact and Earth Sciences | - | 1 | 1 | - | 2 | - |

| Total | 12 | 23 | 19 | 13 | 26 | 15 |

Source: Author’s elaboration.

It is observed that most of the professors who are members of the major area of Linguistics, Letters and Arts indicated a positive answer in both questions. However, for the other areas, negative responses could be seen, especially in the scope of Human Sciences, Applied Social Sciences, Health Sciences and Engineering. It is also notable that all respondents in Agrarian Sciences, Biological Sciences and Exact and Earth Sciences pointed out the negative answers or answered that they did not know how to give an opinion.

With regard to the question about research guidance, 42.6% (23 respondents) have already conducted/oriented undergraduate and graduate research on the subject of human rights, 14.8% (8 respondents) have only guided undergraduate research, 11.1 % (6 respondents) guided postgraduate research and 31.5% (17 respondents) mentioned not having conducted any research related to the thematic area.

As for the motivation that led professors to develop research and/or extension practices in human rights, 46.3% (25 respondents) indicated the alternative regarding academic training, 13% (7 respondents) stated that the interest was given after the admission as a professor at Unicamp, 13% (7 respondents) stated that the interest was aroused after participating in research and/or extension projects related to the theme and 11.4% (6 respondents) indicated that the question did not apply. Special emphasis is given to those who chose to answer this question openly, showing, in some cases, the human rights activism and also the training prior to Unicamp, as shown in Chart 2.

CHART 2 MOTIVATIONS DECLARED BY THE PROFESSORS IN RELATION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF RESEARCH AND/OR EXTENSIONIST PRACTICES ABOUT HUMAN RIGHTS, BY MAJOR AREA OF KNOWLEDGE

| Human Sciences |

|---|

| “After being incorporate by the University administration” |

| “Since my master's degree, motivated by the silence of Psychology about racism” |

| “I have been a militant in the fight for school inclusion (everyone's right to education), since the 90's” |

| “All my academic training (Graduation in History and Post in Anthropology) and professional (10 years in NGOs, 5 at PUC-Rio and 6 at UNICAMP) are linked to the themes of HR, especially in their relationship with ethnic populations” |

| Applied Social Sciences |

| "Set of factors: research, social activism and understanding that labor rights are also part of the human rights agenda" |

| “I developed academic work on the female leader of DDHH” |

| Health Sciences |

| "After seeing the difficulties that some Brazilian citizens have to enjoy their constitutional rights" |

| “Militancy with human rights policies since graduation in Medicine in the 70s” |

| Biological Sciences |

| “Since before joining Unicamp, high school teachers and Religious education, which was implemented when I joined Unicamp where I did all my training and stayed as a Teacher” |

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Some motivations can be highlighted: “motivated by the silence of Psychology about racism”; “Militant in the fight for school inclusion”; and “After seeing the difficulties that some Brazilian citizens have to enjoy their constitutional rights”. These indications, as previously mentioned, incorporate the issue of HR activism, but they also add to the challenges of making them known and effectively respected, as well as the absence of debate in some areas.

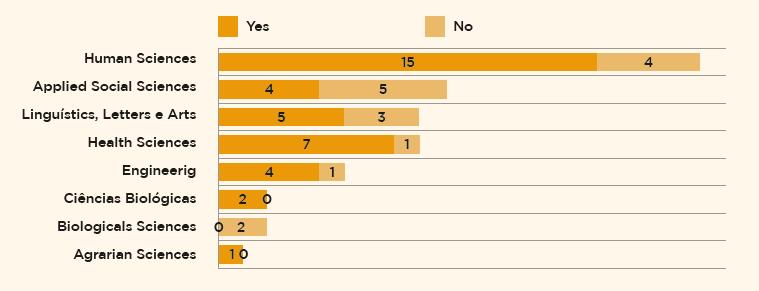

From now on, we will present the answers obtained in relation to the knowledge on the part of the professors regarding the existence of the National Plan for Human Rights Education (NPHRE) of the federal government, in which 55.6% (30 respondents) declared not to know and 44, 4% (24 respondents) indicated knowledge. For those who knew him, it was asked whether the research and extension activities developed by them are guided by the Plan, resulting in a positive response from 62.5% (15 respondents), while 37.5% (9 respondents) indicated the non-use and basement. Along the same lines, we asked about the “University Pact for the Promotion of Respect for Diversity, the Culture of Peace and Human Rights”, with 51.9% (28 respondents) declaring that they do not know it and 48.1% (26 respondents) indicated knowledge. It is noteworthy that not everyone who knew the NPHRE declared to know the Pact, and vice versa. Table 3 shows these results according to the major areas of knowledge.

TABLE 3 PROFESSORS’ KNOWLEDGE ABOUT THE NPHRE AND THE PACT, BY MAJOR AREA OF KNOWLEDGE

| Major Area | NPHRE | University Pact | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Declared to know | Declared not to know | Declared to know | Declared not to know | |

| Human Sciences | 11 | 8 | 11 | 8 |

| Applied Social Sciences | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Linguistic, Letters and Arts | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| Health Sciences | 1 | 7 | 2 | 6 |

| Engineering | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Agrarian Sciences | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Biological Sciences | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Exact and Earth Sciences | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| General Total | 24 | 30 | 26 | 28 |

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Regarding the University Pact, adhered to in 2017 by Unicamp, it is observed that a large part of the professors informed their knowledge, especially in the scope of HS, ASS, LLA and AGS. In the BS and EES, none of the respondents indicated that they had knowledge about the Pact and the NPHRE and, in the HES, the majority declared that they were unaware of such regulations. The latter, however, even though they have indicated the negative answer, present productions in the area of HR, as can be seen in the graphic representations presented.

It is necessary to emphasize the next question, which asks about the existence (or not) of obstacles and challenges that hinder the development of research and/or extension practices that address the theme of human rights. For this question, there were no alternatives, and the professors were free to answer as it was convenient. In doing so, among the 54 respondents, a large part (79.6%) indicated that there were obstacles and/or challenges in the development of research and/or extension practices within the scope of the topic addressed, mainly in the major area of Human Sciences (also due to the amount of respondents in the area). Only four professors mentioned the absence of these obstacles and challenges and seven declared that they did not know how to give an opinion. Of the latter, a professor in the area of Exact and Earth Sciences wrote:

I don’t know how to give an opinion. But there are no clear guidelines on how to deal with the most common human rights problems within Unicamp. For example, there are no clear activities that prepare professors and staff to address cultural, economic and racial differences between students, as well as between students and professors. (own translation)

In Chart 3, we highlight the main responses obtained, according to the major areas of knowledge indicated.

CHART 3 PROFESSORS’ PERCEPTION ABOUT THE EXISTENCE OF DIFFICULTIES/CHALLENGES IN RELATION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF RESEARCH AND/OR EXTENSIONIST PRACTICES IN HUMAN RIGHTS, BY MAJOR AREA OF KNOWLEDGE

| Human Sciences |

|---|

| “The absence of specific training in the area in undergraduate courses; it is often an under-valued area for research funding” |

| “Extension activities are seen as second-class academic activities. In addition, the theme of HRE is considered by a considerable part of the university community as political activism with no link to the production of academic knowledge” |

| “The demands of Postgraduate Studies with production thought in exclusively textual terms (CAPES criteria), the administrative burden imposed by Unicamp on teachers leave little room for adequate involvement with the ‘external community’ to the University. The proper valuation of the time allocated to the extension would help in promoting actions related to Human Rights” |

| “There is little knowledge from teachers to properly address the topic” |

| “Absence of institutional support and scholarships” |

| “Absence of support, funding and visibility” |

| “The knowledge about human rights, the interest only in specialized topics by students and researchers, the difficulty in understanding the importance of the topic in the university environment” |

| Applied Social Sciences |

| “The productivism and competitive logic that professors are subjected to” |

| "The difficulties are related, in my view, to the need to raise society's awareness of the theme of human rights" |

| "It is necessary to make interinstitutional partnerships to advance the theme" |

| “I don't think they are specific barriers in the area of human rights, but barriers in the humanities and social sciences in general. Lack of resources, delegitimizing the field of knowledge are some of them” |

| “In the case of the Institute of Economics, the most concrete works address institutional aspects, without much connection with the theme. The exceptions are the work of Cesit (on the world of work) and NEPP (on public policies). There is also a segment of graduate studies in applied economics that deals with the environment. However, it is not a usual feature at the Institute” |

| "A central difficulty is the long-term maintenance of initiatives that combine information, training and actions that promote a broad and qualified understanding of human rights and the need for constant observance, mobilization and social control so that they are actually implemented" |

| Linguistics, Letters and Arts |

| “Absence of institutional recognition for the academic career” |

| “Better access and debate on information related to the topic” |

| “In the area where I develop an extension project (basic education), there are difficulties that refer to the acceptance of some themes at school by pressure from parents and the fear of some teachers and the governing body. I imagine that these difficulties will intensify in the coming years” |

| “Yes, there are difficulties, precisely because the themes of social impact do not arouse much interest, perhaps because the institution and its curricula are strongly engaged in themes that are not closely linked to these realities” |

| Health Science |

| “Absence of institutional stimulus, poor funding” |

| “There is an absence of institutional stimulus. HR are not priorities” |

| “Funding for research and scholarships for similar topics and absence of curricular enhancement of extension activities for graduation” |

| “Support from the Unicamp institution” |

| “The main obstacle and the almost total disregard and devaluation of extension practices in the context of the teaching career at Unicamp. This pillar is very fragile. Regarding the subject of human rights, I have historically observed important support by PROEC [extension pro-rectory] for related projects that I coordinated. A paradox?” |

| “Yes, because it is a theme linked to the area of Human Sciences, which in health research and practices are against hegemonic. At the Faculty of Nursing, there is a privilege in Teacher Assessments for "productivism" and high impact international publications" |

| Engineering |

| “The University itself, mainly within the scope of the central administration, is unable to put into practice subjects and actions that strengthen respect for human rights. And that is extended to Institutes and Colleges” |

| “It is a theme that is spread/dispersed/pulverized through various social themes. It is embedded within many, many broader issues” |

| “Currently, these themes are seen as indoctrination or ideological. There is fear in teaching/researching/practicing on these topics. Before the current context, there was devaluation, especially of extension practices” |

| "Pre-concepts about the theoretical-scientific dimension of human rights and their potential for improving public policies" |

| Biological Sciences |

| “Ignorance of this Plan and Pact; Failure to understand the Social Function of each and each profession; No perception of the possibility of working with these themes; Lack of Interdisciplinarity and Intersectionality in Research and Practices; Distortion of Human Rights; Non-understanding of this function by Teachers and Educational Institutions at all levels; Political and religious enclosure due to the distortion of whatever” |

| Agrarian Sciences |

| “I believe that this topic is not highly valued by the University” |

Source: Author’s elaboration.

According to the indications obtained, the following challenges/obstacles stand out more frequently: absence and/or insufficient institutional and financial support for the development of these activities; academic productivism; absence of knowledge on the part of professors in relation to the theme and official documents of the federal government that legitimize it; and devaluation and delegitimization of the topic in the current context of the country. These are, therefore, challenges that the literature itself presents us (DIBBERN; CRISTOFOLETTI; SERAFIM, 2018; CANDAU; SACAVINO, 2008; SALVIOLI, 2009) and which are shown to be true also within the scope of Unicamp, hindering the development of research and extension practices in the area of human rights.

As such, in relation to Human Sciences professors, the following responses are highlighted: “absence of support, funds and visibility”; “the theme of the HRE is considered by a considerable part of the university community as political activism with no link to the production of academic knowledge”; “the demands of Post-Graduation with production [...], the administrative burden imposed by Unicamp [...] leave little room for adequate involvement with the‘ community outside ‘the University”; “there are barriers to racial issues”; “the knowledge of human rights, the interest only in specialized topics [...], the difficulty in understanding the importance of the topic in the university environment”. In this sense, the obstacles and challenges related to the financing and institutional support, the association of the subject as militancy, the specific issue of racism, the productivism logic and the understanding of the theme, as well as the treatment of them from specific themes, are evident.

In the scope of Applied Social Sciences, the following stand out: “the productivism and competition logic that professors are subjected to”; “the need to raise awareness of society on the theme of human rights”; “absence of resources, delegitimizing the field of knowledge”; and “the long-term maintenance of initiatives that combine information, training and actions that promote a broad and qualified understanding of human rights and the need for constant observance, mobilization and social control so that they are actually implemented”. In this area, more emphasis is placed on the absence of resources, on maintaining long-term projects and, again, on the issue of academic productivism. In the major area of Linguistics, Letters and Arts, the obstacles/challenges related to institutional support and the complexity of the theme in provoking attention are highlighted: “there are difficulties, precisely because the themes of social impact do not arouse much interest, perhaps because the institution and its curricula are strongly engaged in themes that are not closely linked to these realities”. As for Health Sciences, there is a notable “absence of institutional stimulus. HR are not priorities”; and “the almost total disregard and devaluation of extension practices in the context of the teaching career at Unicamp”.

In the areas of Engineering, Agrarian Sciences and Biological Sciences, the main obstacles/challenges considered by the respondents and which are at the forefront of the development of research and extension practices in human rights refer to the absence of appreciation of the theme by the University and other educational institutions, the ignorance about the federal government documents, as well as the devaluation and fear that can arise when researching these themes: “the University itself, mainly within the scope of the central administration, fails to put into practice assumptions and actions that strengthen respect human rights”; “these themes are currently seen as indoctrination or ideological. There is fear in teaching/researching/practicing on these topics. Before the current context, there was devaluation, especially of extension practices”; “ignorance of this Plan and Pact; not understanding the Social Function of each and each profession; not realizing the possibility of working with these themes; lack of interdisciplinarity and intersectionality in research and practices; distortion of what Human Rights is; lack of understanding of this role by teachers and teaching institutions at all levels ”; “this topic is not highly valued by the University”.

The last question in the survey aims to measure the degree of agreement of professors in relation to some statements. Thus, professors should indicate, after reading the statement, an alternative among the following: “I totally agree”; “Partially agree”; “Partially disagree”; and “Strongly disagree”. Table 4 shows the results of the appointments of the respondent professors, according to the statements exposed in the question.

TABLE 4 NUMBER OF ANSWERS, BY DEGREE OF AGREEMENT, OF RESPONDENT PROFESSORS

| Nº | Statement | Number of answers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I totally agree | Partially agree | Partially disagree | Strongly disagree | ||

| 1 | The University should, as a priority, encourage the development of research that deals with the theme of human rights | 51,85% (28 respondents) | 42,59% (23 respondents) | 5,55% (3 respondents) | - |

| 2 | The University should include a mandatory discipline about human rights for all courses in all areas of knowledge | 59,25% (32 respondents) | 29,62% (16 respondents) | 5,55% (3 respondents) | 5,55% (3 respondents) |

| 3 | One of the University's social commitments is providing human rights education | 87,03% (47 respondents) | 11,11% (6 respondents) | 1,85% (1 respondents) | - |

| 4 | A challenge for the incorporation of human rights education at the University level is related to distorted views about human rights | 59,25% (32 respondents) | 18,51% (10 respondents) | 14,81% (8 respondents) | 7,40% (4 respondents) |

| 5 | A challenge for the incorporation of human rights education at the University level is related to the subject's discipline | 24,07% (13 respondents) | 44,44% (24 respondents) | 5,55% (3 respondents) | 25,92% (14 respondents) |

| 6 | A challenge for the incorporation of human rights education at the University level is related to professor training on the subject | 46,29% (25 respondents) | 37,03% (20 respondents) | 11,11% (6 respondents) | 5,55% (3 respondents) |

| 7 | A challenge for the incorporation of human rights education at the University level is related to the privatization processes of the public university | 33,33% (18 respondents) | 20,37% (11 respondents) | 25,92% (14 respondents) | 20,37% (11 respondents) |

| 8 | A challenge for the incorporation of human rights education at the University level is related to the commercialization processes of the public university | 40,74% (22 respondents) | 24,07% (13 respondents) | 16,66% (9 respondents) | 18,51% (10 respondents) |

Source: Author’s elaboration.

In this sense, for the statement “The University should, as a priority, encourage the development of research that deals with the theme of human rights”, 51.85% (28 respondents) totally agreed, 42.59% (23 respondents) partially agreed and only 5.55% (three respondents) partially disagreed. About the latter, the answer was given by a professor in each area: Human Sciences; Linguistics, Letters and Arts; and Engineering. For the statement “The University should include a mandatory discipline on human rights for all courses in all areas of knowledge”, 59.25% (32 respondents) totally agreed, 29.62% (16 respondents) partially agreed, 5, 55% (three respondents) partially disagreed and 5.55% (three respondents) totally disagreed. Among the latter, the answer was given by a professor in each area: Human Sciences; Health Sciences; and Exact and Earth Sciences. For this specific statement, there was a provision for the inclusion of preferentially mandatory subjects in the pedagogical projects of the courses, in view of the NPHRE, the NGHRE and the University Pact, which was adhered to by the University in question.

The statement “One of the University’s social commitments is providing human rights education” obtained the highest degree of agreement, with 87.03% (47 respondents) fully agreeing, 11.11% (6 respondents) partially agreeing and only 1, 85% (one respondent) partially disagreed, this respondent being from the large area of Biological Sciences.

In relation to the statement “A challenge for the incorporation of human rights education at the University level is related to distorted views on human rights”, 59.25% (32 respondents) claimed to fully agree, 18.51% (ten respondents) agreed partially, 14.81% (eight respondents) partially disagreed and 7.40% (four respondents) totally disagreed, the latter two respondents from the Humanities, one from the Health Sciences and one from the Applied Social Sciences. In the statement “A challenge for the incorporation of human rights education at the University level is related to the subject’s discipline”, 44.44% (24 respondents) partially agreed, 25.92% (14 respondents) totally disagreed, 24.07% (13 respondents) totally agreed and 5.55% (three respondents) partially disagreed. Among the 14 professors who answered that totally disagreed, all areas of knowledge considered are included, except Engineering and Agricultural Sciences.

With regard to the statement “A challenge for the incorporation of human rights education at the University level is related to professor training on the topic”, 46.29% (25 respondents) totally agreed, 37.03% (20 respondents) agreed partially, 11.11% (six respondents) partially disagreed and 5.55% (three respondents) totally disagreed. The latter indicated that they belong to the major areas of Applied Social Sciences, Health Sciences and Biological Sciences. For this specific challenge, it is necessary to consider what is proposed in relation to continuing training in HR by professors and staff, in view of the documents previously mentioned. In a more balanced way, the statement “A challenge for the incorporation of human rights education at the University level is related to the privatization processes of the public university” obtained 33.33% (18 respondents) of indications of total agreement, 20, 37% (11 respondents) partial agreement, 25.92% (14 respondents) partial disagreement and 20.37% (11 respondents) total disagreement. Among the respondents who totally disagreed, all areas of knowledge considered are included, except Agrarian Sciences and Exact and Earth Sciences. Finally, with regard to the last statement, “A challenge for the incorporation of human rights education at the University level is related to the commercialization processes of the public university”, 40.74% (22 respondents) indicated total agreement, 24, 07% (13 respondents) partial agreement, 16.66% (nine respondents) partial disagreement and 18.51% (ten respondents) total disagreement. Among the latter, are all areas of knowledge considered, except Linguistics, Letters and Arts, Agrarian Sciences and Exact and Earth Sciences.

ANALYSIS OF RESULTS

In order to recover the main results obtained in this research, it can be said that most of the respondent professors participate and/or have already participated in research groups that deal directly or indirectly with the theme of human rights. Therefore, considering the questions presented on the research sphere, there are the presence of different themes worked on: within the scope of HS and ASS, the greatest predominance occurs in the themes of the right to education, the right to health and gender, class and race; in the LLA there are themes of gender, class and race, right to education and right to the city; in HES, the topic of the right to health gains more notoriety, followed by the right to education; in ENG, the theme of technology, production and work is presented, as well as the right to the environment; and in the BS and EES, there was the theme of gender, class and race. As for the AGS, the only respondent professor did not indicate any theme in the scope of the research, only for the extension pillar. It is noteworthy, in this sense, that the main themes present in the scope of issues related to research were the right to education, the right to health and gender, class and race.

In the pillar of extension, in addition to the predominance of such themes, other themes were pointed out, such as the care for the homeless population and the relationship between human rights and the media. In addition, there is a congruence between the themes worked by the respondent professors and those indicated by the National Extension Policy (Brazil). In view of this, in order to transcend these pillars, it was also noted the existence of a series of motivations that led professors to the development of research and extension activities about human rights, with emphasis on academic training, experiences related to militancy and the perception of the challenges inherent to guaranteeing such rights.

Particularly in relation to such challenges, in view of the production and dissemination of knowledge about human rights at the University, approximately 80% of the respondent professors indicated their existence. Thus, as main obstacles, the following stand out: the absence and/or insufficiency of institutional and financial support for the development of these activities; academic productivism; the absence of knowledge on the part of professors in relation to the theme and official documents of the federal government that legitimize it; and the devaluation and delegitimization of the topic in the current context of the country. These were, therefore, topics presented directly and/or indirectly within the scope of the responses obtained, configuring themselves as challenges perceived by most of the responding professors from the major areas of knowledge. Such challenges and obstacles must be better understood and explored by the University, given its recently assumed commitment to the agenda. And, in addition to this, they must be considered in the scope of other educational institutions, paying attention to their particularities.

About the professors’ knowledge in relation to the existence of the National Education Plan on Human Rights and the University Pact, it was observed that most respondents are unaware of such regulations, especially in the scope of HES, EES and BS. As for the HS and ASS, the majority of professors indicated that they knew such documents and initiatives. Regarding the knowledge related to institutional policies to support research and extension in HR, despite the fact that such professors develop activities within the scope of this theme, most of them are unaware of the existence of such policies. In addition, in the scope of university extension, most respondents indicated that they did not exist.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

This article seeks to explore the perceptions of Unicamp professors, who have publications and/or extension practices related to the subject of human rights and/or human rights education, about these themes and their practices. Even though the respondents’ cut has reduced the scope, the research managed to make an exploratory essay on these perceptions, raising interesting results. One of them is the respondents’ strong agreement (87%) regarding the consideration of human rights education as one of the social commitments to be assumed by the public university. On the other hand, most respondents are unaware of the existence of the National Human Rights Education Plan and the University Pact, especially those within the scope of the HES, EES and BS, showing that the elaboration and implementation of these norms (without induction of financial resources) have little effect on the induction of professors’ practices. That is, professors who work with these themes do so because of their sensitivity to them, making it not necessarily due to the situation of reinforcing human rights education as an educational practice of critical and reflective training of the subjects, but because of the urgency of the themes of isolated form. Finally, it is recognized that, by obtaining a greater number of respondents inserted in HS, ASS, LLA and HES, the results have become limited in relation to ENG, EES, BS and AGS. Therefore, considering the responses obtained and their limitations, the development and conduct of new research is encouraged, with a view to further deepening the topics worked by a major area of knowledge, as well as their specificities. In this sense, the research instrument and the analytical categories used in this research may help other similar studies.

REFERENCES

AMARO, A.; PÁVOA, A.; MACEDO, L. A arte de fazer questionários. Porto: Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade do Porto, 2004. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Comitê Nacional de Educação em Direitos Humanos. Plano Nacional de Educação em Direitos Humanos. Brasília: Secretaria Especial dos Direitos Humanos; Ministério da Educação; Ministério da Justiça Unesco, 2007. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Secretaria Especial dos Direitos Humanos da Presidência da República. Programa Nacional de Direitos Humanos (PNDH-3). Brasília: SEDH, 2010. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Diretrizes Nacionais para a Educação em Direitos Humanos. Brasília, 2012. [ Links ]

CANDAU, V.; SACAVINO, S. B. Educação em direitos humanos no Brasil: ideias-força e perspectivas de futuro. Pensamiento e ideas-fuerza de la educación en derechos humanos en Iberoamérica, Santiago, OIE/Orealc/Unesco, p. 68-83, 2008. [ Links ]

CHAGAS, A. T. R. O questionário na pesquisa científica. Administração On Line, São Paulo, v. 1, n. 1, p. 1-14, jan./mar. 2000. [ Links ]

DIAS SOBRINHO, J. Educação superior: bem público, equidade e democratização. Avaliação: Revista da Avaliação da Educação Superior, Campinas; Sorocaba, SP, v. 18, n. 1, p. 107-126, 2013. [ Links ]

DIAS SOBRINHO, J. Universidade e novos modos de produção, circulação e aplicação do conhecimento. Avaliação: Revista da Avaliação da Educação Superior, Campinas; Sorocaba, SP, v. 19, n. 3, p. 643-662, 2014. [ Links ]

DIAS SOBRINHO, J. Universidade fraturada: reflexões sobre conhecimento e responsabilidade social. Avaliação: Revista da Avaliação da Educação Superior, Campinas; Sorocaba, SP, v. 20, n. 3, p. 581-601, 2015. [ Links ]

DIBBERN, T. A.; CRISTOFOLETTI, E. C.; SERAFIM, M. P. Educação em direitos humanos: um panorama do compromisso social da universidade pública. Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, v. 34, e176658, 2018. [ Links ]

FORPROEX. Política Nacional de Extensão Universitária. 2012. Disponível em: https://www.ufmg.br/proex/renex/documentos/2012-07-13-Politica-Nacional-de-Extensao.pdf. Acesso em: 15 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

GIL, A. C. Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa social. São Paulo: Atlas, 2008. [ Links ]

MAGENDZO, A. Educación en derechos humanos: un desafío para los docentes de hoy. Santiago: LOM, 2006. [ Links ]

MARCONI, M. A.; LAKATOS, E. M. Fundamentos de metodologia científica. 5. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2003. [ Links ]

NOGUEIRA, R. Elaboração e análise de questionários: uma revisão da literatura básica e a aplicação dos conceitos a um caso real. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Coppead de Administração da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 2002. (Relatórios Coppead, 350). [ Links ]

ORGANIZAÇÃO DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS - ONU. Declaración de las Naciones Unidas sobre educación y formación en materia de derechos humanos. [S.l.]: Asamblea General, Resolución 16/1, de 23 de marzo de 2011. Disponível em: https://www.ohchr.org/sp/issues/education/educationtraining/pages/undhreducationtraining.aspx.aspx. Acesso em: 1 jun. 2020. [ Links ]

ORGANIZAÇÃO DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS PARA A EDUCAÇÃO, A CIÊNCIA E A CULTURA - UNESCO. Plano de Ação. Programa Mundial de Educação em Direitos Humanos, 2ª fase. Brasília: Unesco, 2012. Disponível em: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002173/217350por.pdf. Acesso em: 1 jun. 2020. [ Links ]

RODINO, A. M. La institucionalización de la educación en derechos humanos en los sistemas educativos de América Latina (1990-2012): avances, limitaciones y desafíos. In: RODINO, A. M. et al. (org.). Cultura e educação em direitos humanos na América Latina: trajetórias, desafios e perspectivas. João Pessoa: CCTA, 2016. [ Links ]

SALVIOLI, F. La universidad y la educación en el siglo XXI: los derechos humanos como pilares de la nueva Reforma Universitaria. San José: IIDH, 2009. [ Links ]

SILVA JÚNIOR, S. D.; COSTA, F. J. Mensuração e escalas de verificação: uma análise comparativa das escalas de Likert e Phrase Completion. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa de Marketing, Opinião e Mídia, São Paulo, v. 15, p. 1-16, 2014. [ Links ]

TAVARES, C. Educar em direitos humanos, o desafio da formação dos educadores numa perspectiva interdisciplinar. In: SILVEIRA, R. M. G. et al. Educação em direitos humanos: fundamentos teórico-metodológicos. Brasília: Secretaria Especial dos Direitos Humanos, 2010. p. 487-503. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, S. Como elaborar questionários. São Paulo: Atlas, 2009. [ Links ]

1In the original: “Instituições de ensino superior, por meio de suas funções básicas (ensino, pesquisa e serviços para a comunidade), não só têm a responsabilidade social de formar cidadãos éticos e comprometidos com a construção da paz, a defesa dos direitos humanos e os valores da democracia, mas também de produzir conhecimento visando a atender os atuais desafios dos direitos humanos, como a erradicação da pobreza e da discriminação, a reconstrução pós-conflitos e a compreensão multicultural. Portanto, o papel da educação em direitos humanos na educação superior torna-se fundamental. Essa educação diz respeito não só ao conteúdo do currículo, mas também aos processos educacionais, aos métodos pedagógicos e ao ambiente no qual a educação está presente”.

3In the original: “en las dos últimas décadas, en especial desde 2000, se produjeron notables progresos en reconocer a la EDH dentro de la normativa educativa de los países latinoamericanos. A la fecha, su reconocimiento institucional es alto. Aunque este fenómeno por sí solo y automáticamente no transforma la práctica escolar, es la primera condición que hace posible cualquier transformación. La progresiva legitimidad de la EDH (que hasta entrados los años 1990 en muchos países era vista con recelo como peligrosa), da confianza a las y los educadores para empezar a hablar sobre derechos humanos, aunque sea de modo incipiente, y sensibiliza a autoridades, técnicos, docentes y familias respecto al valor de abordarlos en las aulas”.

4In the original: “proporciona resultados bastante críticos em relação à objetividade, pois os itens podem ter significado diferente para cada sujeito pesquisado”.

5In the original: “a mensuração sempre ocorre em situações complexas, onde diversos fatores influenciam as características medidas e o processo de mensuração, podendo gerar erros não amostrais”.

6In the original: “constatação de sua eficácia para verificação dos objetivos; determinação da forma e do conteúdo das questões; quantidade e ordenação das questões; construção das alternativas; apresentação do questionário e pré-teste do questionário”.

7In the original: “consiste em tomar um construto e desenvolver um conjunto de afirmações relacionadas à sua definição, para as quais os respondentes emitirão seu grau de concordância”.

9In the original: “em média, os questionários expedidos pelo pesquisador alcançam 25% de devolução”.