Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versão impressa ISSN 0100-1574versão On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.51 São Paulo 2021 Epub 27-Ago-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/198053147248

THEORIES, METHODS, EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH

EDUCATION, POVERTY, AND GENDER: AN INTERCULTURAL AND DECOLONIAL ANALYSIS IN THE ANDEAN REGION

IUniversidad Nacional de Educación (Unae), Azogues, Ecuador; javier.collado@unae.edu.ec

IIUniversidad de Cuenca (U de Cuenca), Cuenca, Ecuador; joselin.segovias@ucuenca.edu.ec

IIIUniversidad Nacional de Educación (Unae), Azogues, Ecuador; sacufuna@unae.edu.ec

The objective of this article is to contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 1, 4, and 5 in the Andean Region, based on a critical, intercultural, and decolonial dialogues. The methodology systematizes, analyzes and interprets data obtained from the comparative study in the seven Andean countries, using different poverty, educational, and gender indexes from 2007 to 2017. As a result, the article allows to know the political, economic, educational, and social evolution in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela. An intersectoral approach is also developed in order to recognize the conditions of structural inequality suffered by indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples of these Andean societies. To conclude, proposals are made to (re)think and (re)build strategies, plans, and public policies in the region.

Key words: EDUCATION; GENDER; INTERCULTURALITY; POVERTY

El propósito del artículo es contribuir a los objetivos de desarrollo sostenible (ODS) 1, 4 y 5 en la Región Andina, desde una posición crítica, intercultural y decolonial. La metodología sistematiza, analiza e interpreta los datos obtenidos del estudio comparativo en los siete países andinos, usando distintos índices de pobreza, educación y género de 2007 a 2017. Como resultado, el artículo permite conocer la evolución política, económica, educativa y social en Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Perú y Venezuela. También se desarrolla un enfoque intersectorial con el fin de reconocer las condiciones de inequidad estructural que sufren los pueblos indígenas y afrodescendientes de estas sociedades andinas. Para concluir, se formulan propuestas para (re)pensar y (re)construir las estrategias, planes y políticas públicas de la región.

Palabras-clave: EDUCACIÓN; GÉNERO; INTERCULTURALIDAD; POBREZA

O intuito do artigo é contribuir com os objetivos de desenvolvimento sustentável (ODS) 1, 4 e 5 na Região Andina, a partir de uma posição crítica, intercultural e decolonial. A metodologia sistematiza, analisa e interpreta os dados obtidos no estudo comparativo nos sete países andinos, utilizando diferentes índices de pobreza, educação e gênero entre 2007 e 2017. Dessa forma, o artigo permite conhecer a evolução política, econômica, educacional e social da Argentina, Bolívia, Chile, Colômbia, Equador, Peru e Venezuela. Também é desenvolvida uma abordagem intersetorial para reconhecer as condições de desigualdade estrutural sofridas pelos povos indígenas e afrodescendentes dessas sociedades andinas. Para concluir, são formuladas propostas para (re)pensar e (re)construir as estratégias, planos e políticas públicas da região.

Palavras-Chave: EDUCAÇÃO; GÊNERO; INTERCULTURALIDADE; POBREZA

Cet article vise à contribuer aux objectifs de développement durable (ODD) 1, 4 et 5 pour la région andine, dans une perspective critique, interculturelle et décoloniale. La méthodologie systématise, analyse et interprète les données obtenues dans une étude comparative des sept pays andins, en utilisant des différents taux de pauvreté, d’éducation et de genre évalués entre 2007 et 2017. Pae ce biais l’article permet de connaître l’évolution politique, économique, éducationnelle ve et sociale de l’Argentine, de la Bolivie, du Chili, de la Colombie, de l’Équateur, du Pérou et du Venezuela. Une approche intersectorielle a aussi été adoptée permettant de reconnaître les inégalités structurelles dont sont victimes les peuples autochtones et les afro-descendants de ces sociétés andines. Pour conclure, des propositions sont formulées pour (re)penser et (re)élaborer les stratégies, plans et politiques publiques de la région.

Key words: ÉDUCATION; GENRE; INTERCULTURALITÉ; PAUVRETÉ

IN 2015, the Member States of the United Nations agreed to meet 17 Sustainable Goals (SDGs) by 2030 (United Nations, 2015). In this context, the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) was born as a global initiative that helps the United Nations to achieve the SDGs, and the SDSN of the Andes integrated Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela intending to mobilize different public and private sectors. According to the SDSN report (SDSN, 2018), tackling local, national, and regional socio-environmental issues requires cooperation between governments, civil society, and the private sector.

Overall, the mission and vision of the SDGs were well received by national governments, international organizations, and development cooperation agencies, as well as by civil society NGOs. Surprisingly, the academic world has also given rise to numerous articles, books, seminars, congresses, courses, and workshops that reinforce the SDGs discourses. However, there is no debate that analyzes the SDGs from a critical, intercultural, and decolonial perspective. There are academic criticisms of the SDGs because they do not question the fundamental epistemic pillars on which Western societies are based on modernity, capitalism, and anthropocentrism (Kowii, 2011).

This developmentalist, monocultural and Western vision is gaining ground in the collective imagination of all the countries of the world. In contrast, this paper approaches the SDGs from an axis of paradigmatic enunciation of the cosmovision of the indigenous peoples of the Andean countries. This implies other epistemological, cultural, and political ways of being, feeling, and acting to achieve the SDGs, which are decolonial, post-capitalist, and biocentric. This article adopts a polylogical view of the SDGs as it is an instrument to unite international efforts of governments, civil society, and private companies. It also considers that the SDGs are a pluri-paradigmatic frame of reference and should be approached from an ecology of knowledge (De Sousa, 2009). This academic position implies a decolonial turn to the SDGs that includes alternative ways of life to the concept of “development” imposed from the West (Maldonado, 2008).

If we want future generations to be able to live in a dignified manner, we must question the concept of “sustainable development”, which is rooted in political and academic discourse. For Escobar (1996) and Esteva (1997), the concepts of “development” and “sustainable development” are an invention and a myth that we must quickly overcome. Since the report “The Limits to Growth” (Meadows et al. 1972), we have been believing for four decades that the idea of “sustainable development” would solve socio-environmental problems. However, this is a simplistic developmental view that lacks scientific credibility.

According to Wackernagel and Rees (1996), the ecological footprint that we leave on our planet has multiplied exponentially since the 1970s. Oberhuber (2004) estimates that between 1990 and 2020, 10% to 38% of planetary biodiversity will have disappeared. This means that the SDGs represent an innate opportunity to avoid falling into ecological points of no return, which threatens the sixth mass extinction (Pievani, 2014). Whether we like it or not, we are all on the same ship, Earth, and we must walk towards common welfare. However, that does not imply imposing a cultural vision or a developmental perspective on others. On the contrary, we must enrich each other to design cultures that restore natural resources and rebuild communities (Pauli, 2017).

Methodology and research focus

This research work compiles documentary studies to obtain quantitative and qualitative information that examines the economic, educational, and social evolution of the Andean Region. An analytical, systematic, and interpretive methodology was used on the data and indicators that address SDG 1, 4, and 5. Among the data collected, the most important reports used for this research were obtained from the following institutions: World Bank (2020a), Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe [Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean] - Cepal (2020), Naciones Unidas [United Nations] (2015), ONU Mujeres [UN Women] (2015), Oxford Committe for Famine Relief - Oxfam (2016), SDSN (2018), Unesco (2015, 2020b) and other institutions and researchers. The focus of this research is, therefore, to analyze the evolution of these countries from 2007 and 2017. It then concludes with an intersectoral approach that identifies the situation of the most disadvantaged sectors.

It is important to clarify that, although this article seeks to encourage governments, the private sector, NGOs, and civil society to achieve the goals of SDG 1, 4, and 5, it also aims to think critically about the plans, strategies, and public policies of regional cooperation. This research seeks to create an inter-epistemological and cross-border space that allows deconstructing the intrinsic coloniality in the SDGs (Collado, 2016). According to Hidalgo et al. (2019, p. 7), the SDGs are based on “. . . the coloniality-patriarchalism-heteronormality of power-knowledge-being, on capitalism and anthropocentrism. . . ,” that is why they propose the Goals of Good Living as a geopolitical decolonial praxis. For Hidalgo and Cubillo (2016), Good Living is an alternative that emerged in the Andean countries as a response to the concept of “development” imposed from the West, which seeks to live in harmony with all living beings.

Inspired by the philosophy of life of the ancestral indigenous peoples of Abya Yala (Latin America), Good Living has emerged as a geopolitical alternative to western development since the 1990s. According to Viteri et al. (1992), the Amazanga Plan was elaborated by the Organization of the Indigenous Peoples of Pastaza (OPIP) to manage the natural resources of the Amazon, in critical opposition to the concept of “sustainable development” proposed by international organizations (Brundtland, 1987). This indigenous reaction was caused by the objectification and reification that this concept carries out on nature since it excludes the character of a living, sacred and mythical entity that constitutes the Pachamama, our Mother-Earth according to the Andean worldviews.

Nowadays, Good Living emerges as a geopolitical alternative based on the critical theory of development, initiated by indigenous authors (Dávalos, 2008; Bautista, 2010), environmentalists and post-developmentalists (Acosta, 2013; Gudynas, 2011), socialists (Ramírez, 2010; García, 2010), and by other critical thinkers (Latouche, 2006; Tortosa, 2009; Viteri, 2002; Walsh, 2003). This whole current of authors opposes the concept of ‘development’ imposed by the West and argues that this notion has not been achieved either in the so-called “developed countries” or in the “developing countries” (Escobar, 1996). On the contrary, they defend that economic, social, cultural, and environmental policies were conceived from the excluding epistemic pillars of modernity, which have given rise to the current ecological unsustainability (Naredo, 2000), to the coloniality of power (Mignolo, 2007; Quijano, 2000), to a socio-ecological crisis (Craig, 2017) and to “bad development” or “bad living” in all the countries of the world (Tortosa, 2009).

For this reason, we cannot continue to perpetuate the Western development model inherent in the SDGs, and we must conceive other geopolitical horizons based on the ways of life of the Andean peoples and the Abya Yala people. It is against this backdrop that this paper sets out to position the discourse of the SDGs from the pluri-paradigmatic reality that characterizes the countries of the Andean Region. Although SDG 1, 4, and 5 are approached from a critical perspective that seeks to overcome cognitive fallacies, epistemicide, and the monocultural character that every project of modernity entails (De Sousa, 2009), they are also approached in the spirit of helping to achieve them. Ultimately, they represent a cry of hope for millions of people living in extreme poverty and misery.

Comparative analysis of poverty, education, and gender in the Andean Region (2007-2017)

This article systematizes, analyzes, and interprets different poverty indices and educational and gender indicators, corresponding to the seven countries of the Andean Region during the years 2007 to 2017. First, it describes the situation of SDG 1 on poverty eradication, comparing poverty rates and national poverty risk, the feminization of poverty, and the distribution of national income. Secondly, SDG 4 on education is addressed, where national rural/urban illiteracy rates, primary and secondary school enrollment rates, and secondary school completion rates are studied and compared. Thirdly, SDG 5 regarding gender equality is discussed, where the population with no income of their own and classified by gender, the ratio of urban wages between men and women, and the percentage of women in parliamentary seats are analyzed and compared. Finally, an intercultural analysis is carried out to identify the sociodemographic situation of indigenous and Afro groups, who suffer greater poverty and social exclusion in this region.

What is the status of SDG 1 to eradicate poverty?

The 2015 United Nations report (Naciones Unidas, 2015, p. 4) compared extreme poverty rates worldwide which noted that “. . . the number of people living in extreme poverty has been reduced by more than half, falling from 1,900 million in 1990 to 836 million in 2015. Most of this improvement has occurred since 2000”. In the so-called “developing countries” it shows that between 1990 and 2015, the population that lived on less than USD 1.25 a day has been reduced from 47% to 14%. This means that in 1990 one in two people lived in extreme poverty, on less than USD 1.25 a day, while in 2015, one in five people did. “In 2011, almost 60% of the world’s one billion extremely poor people lived in just five countries”, explains former UN Secretary- -General Ban Ki-moon (Naciones Unidas, 2015, p. 3).

Although these data are encouraging, there is the problem of monetizing the definition of extreme poverty, ignoring other social dimensions. Moreover, the SDG studies and reports do not address the causes of this poverty, and this prevents us from having an impact on its causes, such as inequality in the distribution of wealth imposed by the markets (Yunus, 2007). For Sen (2009), what is important is the effective capacity to satisfy their own needs (be it in monetary, in-kind, or market terms) and not their income level. Globally, the highest rates of extreme poverty are found in rural areas of South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa that are landlocked or affected by armed conflict (Sachs, 2005).

In Latin America and the Caribbean, the period 2000-2010 has been the one with the highest economic growth in the last four decades. The development of active social policies has led to an increase in the middle class, especially in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. According to the United Nations (Naciones Unidas, 2015), this growth has decreased the population living in poverty, but there are still about 216 million people in Latin America (38% of the population) who are at risk of living in conditions of poverty. This means that we must still invest in public social security policies that ensure decent conditions for families at risk in the region.

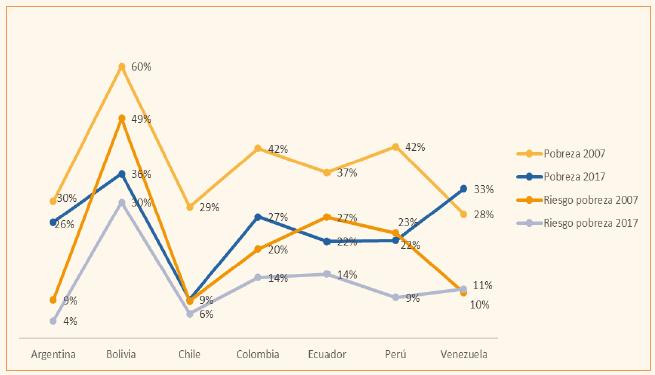

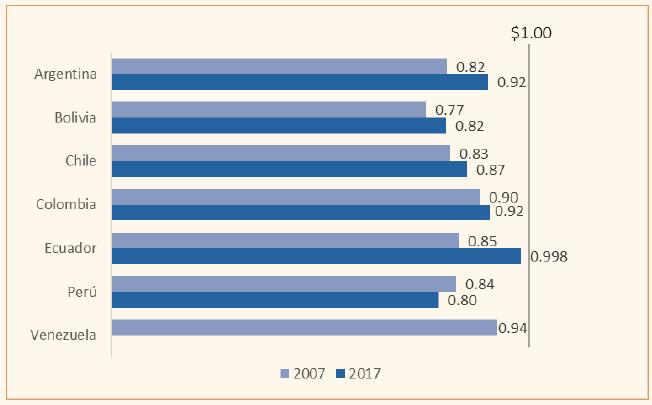

Figure 1 provides an analysis of poverty considering two variables: the poverty rate, defined as the percentage of people living below the national poverty line measured based on their income, and the risk of impoverishment. The latter indicator is represented by the percentage of people at risk of falling below the national poverty line when covering medical expenses. This measure is of utmost importance in the region because Latin America is the second region in the world with the highest percentage of people at risk (World Bank, 2020b).

Figure 1 shows the behavior of these two variables in 2007 and 2017. In general, poverty patterns have decreased in all the countries of the Andean region, except in Venezuela, where it is increasing. The poorest country in the region in both periods of analysis is Bolivia. However, Bolivia stands out as the country with the best results in terms of percentage reduction of poverty, followed by Chile, Peru, and Ecuador. In fact, these three countries are the Andean nations with the lowest income poverty in 2017. These results are attributed to the increase in the number and scope of social programs in both Peru and Ecuador, because of the boom in basic products, oil, and copper, during this period (World Bank, 2019).

The Chilean case is notable, which, being the country with the second-lowest poverty rate in 2007, carries out a significant struggle to obtain the highest reduction rate and be the country with the lowest percentage of poor population in 2017. One of the factors to which this result is attributed is the implementation of the Chile Solidario program, characterized by a multidimensional and multisectoral approach to poverty, which replaced the traditional monetary transfers with the promotion of the capacities and skills of the most vulnerable population (Larrañaga et al., 2014).

It is also interesting to analyze what happens with the percentage of people at risk of falling into poverty due to medical expenses. Again, this percentage decreased from 2007 to 2017 in all countries except Venezuela. Moreover, Bolivia ranks as the country with the highest percentage of the population at risk, while Chile is the country with the lowest percentage in both periods. Peru and Ecuador again emerge among the three countries with the highest risk of poverty due to medical expenses in 2007. Despite presenting a significant improvement, Ecuador continues to be among the worst-performing countries in 2017, along with Colombia and Bolivia. Peru, on the other hand, moves into the top three because 61% of the population is no longer at risk of poverty, rising from a rate of 23% to 9%.

From a critical and decolonial analysis, it is possible to discern that those countries with the highest percentages of poverty are also those that present a greater risk of poverty, which shows the level of vulnerability of these societies. This fact is of crucial importance when considering that the social policy that has made it possible to generate much of the progress in the region has been financed by the increase in the price of commodities, a phenomenon that is no longer part of the global scenario and that could jeopardize this progress. Therefore, public policymakers need to focus not only on the pure evolution of poverty but also on the evolution of triggers such as medical expenses.

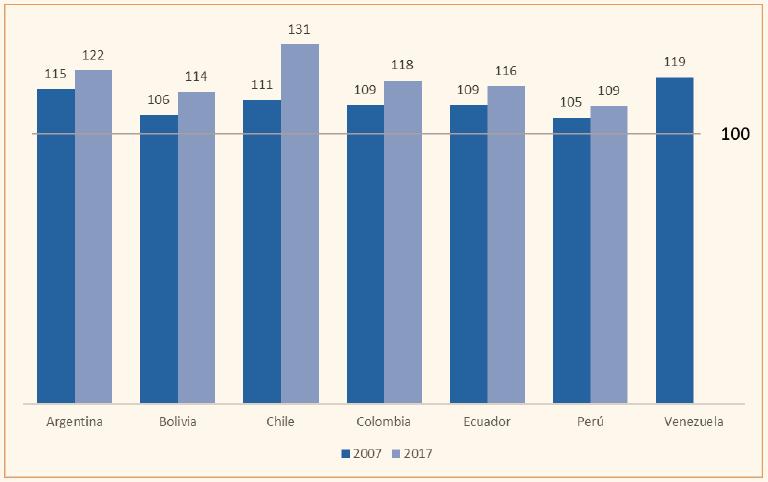

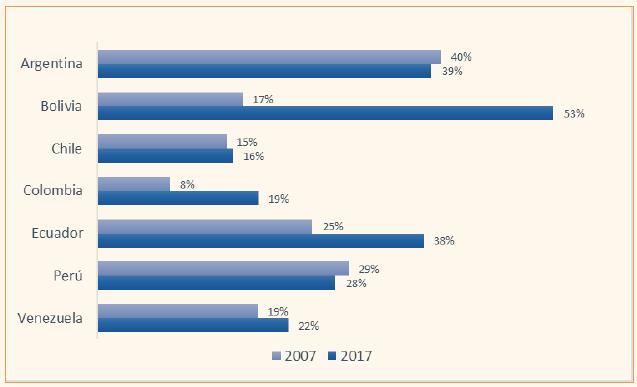

To extend the analysis of SDG 1, Figure 2 presents an index of feminization of poverty, which shows a significant disparity in incidence between men and women. Based on the information available, it is evident that women are much more affected than men. It is also worrying that this feminization of poverty has increased in all countries from 2007 to 2017. Therefore, even though poverty has improved in the regional panorama, a cross-cutting gender analysis shows that the situation of women has worsened drastically.

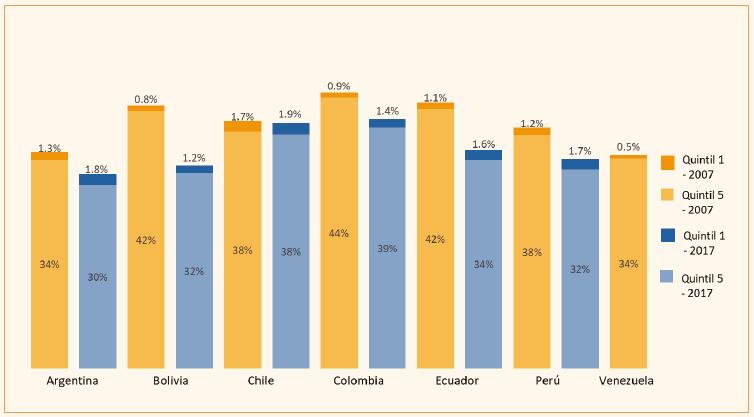

Just as economic income makes it possible to achieve a decent standard of living, how this income is distributed among the inhabitants greatly influences their possibilities to access available goods and services. Figure 3 shows what percentage of national income is distributed between the highest (richest) income quintile of the population and the lowest (poorest) income quintile in each country during 2007 and 2017. An equitable distribution would imply the distribution of approximately 20% of income in each quintile.

Source: World Bank (2020a).

FIGURE 3 DISTRIBUTION OF NATIONAL INCOME 2007-2017: INCOME QUINTILES 1 AND 5 3

A first interpretive analysis of Figure 3 clearly shows that the total percentage of income distributed between these two segments of the population has decreased in all countries. This means a shift of income towards middle-income segments, which is in line with the evidence showing a strengthening of the middle class throughout the Latin American region (World Bank, 2019). This interpretation is supported by observing that the concentration of income in the wealthiest segment of the population decreases in all countries, while for the most impoverished population, it increases, except in Chile.

Bolivia and Ecuador show a remarkable improvement in this indicator. In 2007 these countries presented the highest concentration of income in the wealthiest segment of the population. In 2017, these two countries presented the most significant reduction in concentration in the high-income sector in favor of the middle-income sectors. Colombia, on the contrary, with the lower-income redistribution, remains the country with the worst performance. In general, income distribution has improved for the poorest sector of the Andean region. However, there is still a long way to go to reach a more equitable society. As a proposal for other critical readings of the SDG indicators, Martínez (2009) argues that co-development strategies are required to implement equitable policies for the redistribution of natural resources that bring us closer to models of life that are less harmful to the environment and that allow for dignified human development for all humanity, present, and future.

What is the status of SDG 4 to ensure quality, inclusive and equitable education?

According to the United Nations (Naciones Unidas, 2015, p. 24), “the net primary school enrollment rate in developing regions has reached approximately 91% in 2015, compared with 83% in 2000”. The number of children of primary school age who did not attend school decreased by almost half worldwide: from 100 million in 2000 to about 57 million in 2015. It is estimated that half of those children who did not attend elementary school live in conflict-affected areas. While the literacy rate among 15-24-year-olds has increased globally from 83% to 91% between the years 1990 and 2015, Unesco’s EFA Global Monitoring Report 2015 (Unesco, 2015, p. 3) estimates that “at least 750 million adults, about two-thirds of whom are women, will not have rudimentary literacy skills in 2015”. Despite notable progress worldwide, there are still many challenges in the Andean region to achieve universal, free, equitable, and quality primary and secondary education.

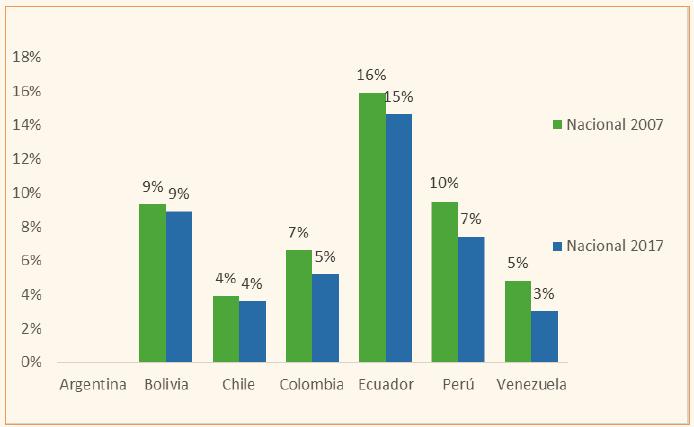

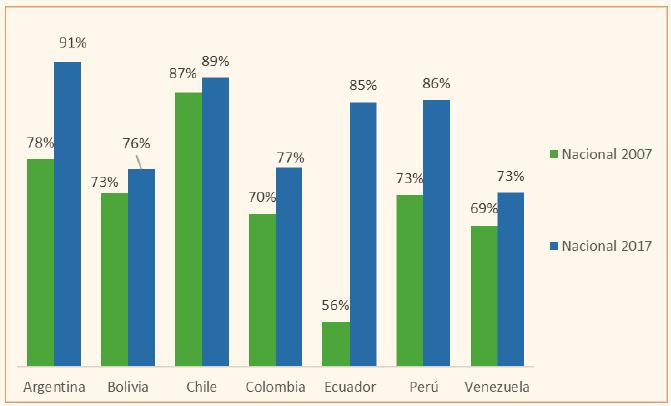

Figure 4 presents information on the illiteracy rate of the population 15 years of age and older. Despite the limitations of this indicator, it is interesting to show its behavior at the national level, as well as its array at the urban and rural levels. As revealed at the national level, Venezuela, Chile, and Colombia have the lowest percentage of people who cannot read or write in 2017. On the contrary, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru present the highest percentages of illiterate people. A decrease in the national illiteracy rate is observed in the countries for which information is available. It can be interpreted that this progress is a result of the variation in the rural rate since the urban rate shows almost no variation. According to Cepal (2020), this indicator shows significant gaps in the literacy levels between areas of residence and between age groups. Notably, in Bolivia and Ecuador, more than 30% of the adult population over 60 years of age are illiterate, a percentage that reaches 50% and 43% in the rural areas of these countries, respectively. This highlights the need to deepen the educational public policy proposals developed in rural areas since these are the areas that suffer the most from structural illiteracy.

Primary education is fundamental for training students in basic skills related to reading, writing, and mathematics. However, other interpretations of the SDG indicators also propose to include studies focused on critical social, cognitive, emotional, and physical skills for student development (World Bank, 2020a). Figure 5 shows that the country with the highest percentage of children enrolled in primary school in Argentina, a finding that remains at the same level in both study periods. It is important to emphasize that the enrollment rate has decreased throughout the region, except for Colombia and Argentina. Venezuela, on the other hand, reports the lowest level of primary enrollment. Given this indicator of universalization of primary education as suggested by Unesco (2020b), it can be affirmed that the Andean Region has distanced itself from this important objective; thus, urgent strategies must be created to improve enrollment rates. This situation suggests the creation of indicators for the SDGs that study the economic costs of student enrollment, both in public and private institutions.

Secondary education develops skills, abilities, and competencies for personal performance. It also prepares young people for better job options and enables them to stay away from certain illicit and criminal activities. Although several countries in the Andean Region have created regulatory frameworks and passed educational laws to expand education at this level, attention to adolescent schooling still needs to be strengthened (Claro, 2007). Figure 6 exposes the national net secondary enrollment rate. It is evident that from 2007 to 2017, the indicator has improved both globally and for men and women in all countries. In 2007 the country with the highest access to secondary education was Chile, while in 2017, it was Argentina. In the evolution of this indicator, Ecuador stands out notably, with an increase of almost 30% of young people in the secondary education system.

Source: World Bank (2020a).

FIGURE 6 NATIONAL NET SCHOOL ENROLLMENT RATE: SECONDARY LEVEL 2007-2017 6

When analyzing the national net school enrollment rate from a gender perspective, all countries have improved access to secondary level for both men and women, with slight differences. In both periods, the enrollment rate of women is higher than that of men throughout the region. This apparently positive result for women could be reversed when analyzing the secondary completion rate due to the high rates of teenage pregnancy that prevent high school completion unequally for men and women (Organización Panamericana de la Salud [OPS], 2016).

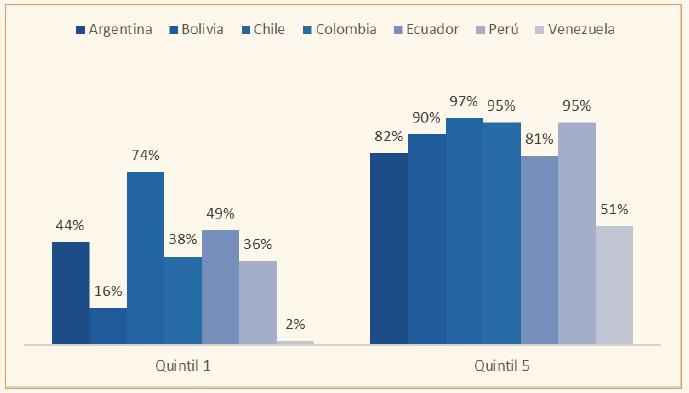

Figure 7 presents the secondary school completion rate by income level to look at educational inclusion in the countries of the Andean Region. Despite its relevance, this indicator does not have a complete record, and the information presented refers to different years for each country. Although it is possible to analyze each country’s scenario separately, it does not allow for regional comparison. In general, the population with the highest income level (quintile 5) is more likely to complete secondary education in each country, revealing substantial inequalities that begin at school age. The country with the most significant difference in the possibilities of school success between economic strata is Bolivia, where 90% of people with high incomes complete secondary education, while only 16% of people with limited resources do so. In contrast, the country with the highest secondary education completion rate is Chile, with 97% for the wealthiest quintile and 74% for the poorest quintile.

Source: Unesco (2020a).

FIGURE 7 NATIONAL SECONDARY SCHOOL COMPLETION RATE BY INCOME LEVEL: QUINTILES 1 AND 5 7

On the other hand, there are still high rates of pregnancy among teenagers in the region that keep them away from secondary education. Moreover, the gap between young people accessing secondary education in urban and rural areas also remains. This leads us to consider the urgent need to create educational management proposals that focus on improving the quality of services in rural areas.

In sum, the educational goals of SDG 4 should ensure the achieved goals, eliminate gender disparities, improve teacher training, and adopt new approaches that teach the skills required for the 21st century. Also, the SDG indicators should be complemented with other methodological proposals that go beyond the quantification, measurement, and commensurability of knowledge through instruments related to the labor market. That is qualitative complementation that includes new perspectives of educational innovation open to the complexity and integrality of people: through a transdisciplinary epistemic vision, a dialogue of intercultural knowledge, and community regenerative practices (Collado et al., 2019).

What is the status of SDG 5 to achieve gender equality?

The education of girls and women has had a multiplier effect in all socio-cultural areas, but significant gaps still exist between men and women in the region (Cepal, 2017a). Due to the efforts of national governments, civil society, and international institutions, many more girls now attend school compared to a decade ago, and women have achieved better working conditions and greater political visibility in governments. According to the United Nations report (Naciones Unidas, 2015), 64% of the so-called “developing countries” have achieved gender parity in primary education. It was only achieved in secondary education by one-third of the 148 countries or territories analyzed.

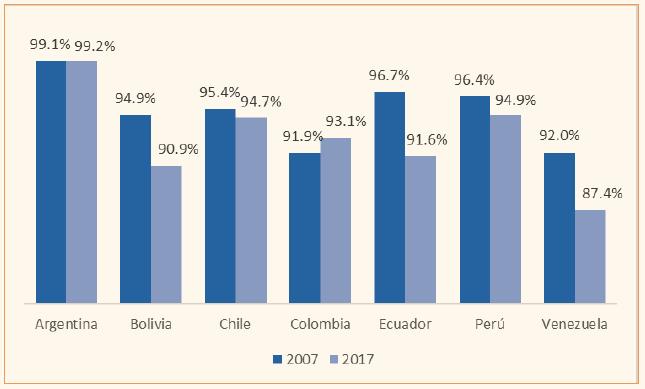

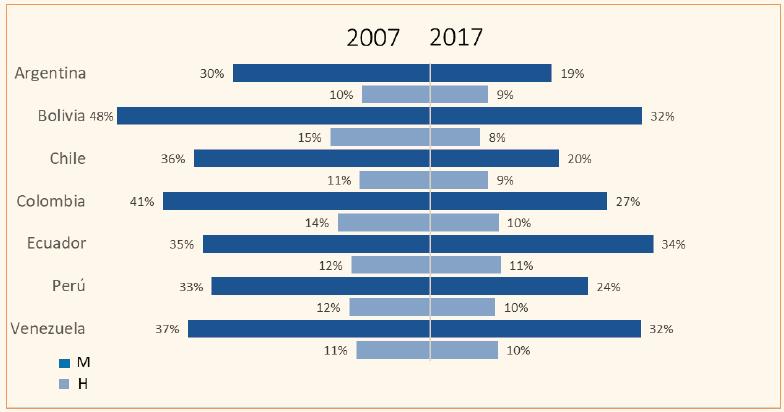

The Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean monitors SDG 5 by defining three categories, called autonomies (Cepal, 2017b; Observatório de Igualdad de Género de América Latina y el Caribe, 2020): (i) economic, (ii) in decision-making, (iii) physical. Due to the availability of information, this research analyzes and interprets the first two. Figure 8 represents the percentage of the national population that does not receive income and economic autonomy. The first pattern that can be interpreted from the analysis is that women have a significantly higher percentage in the two periods analyzed and in all countries. This means that they do not receive an income that allows them to be financially independent. On average, almost 3 in 10 women are economically vulnerable in the region, compared to 1 in 10 men.

Source: Cepal (2020).

FIGURE 8 PERCENTAGE OF THE NATIONAL POPULATION WITHOUT OWN INCOME BY GENDER 2007-2017 8

It is also clear that this indicator has improved from 2007 to 2017, indicating that more men and women are earning an income. Likewise, there is evidence of greater female participation in the labor market, although they continue to be more economically vulnerable than men. The year-on-year evolution shows that the countries where the situation of women has improved the most are Chile, Bolivia, and Colombia. The latter two were the countries with the most unfavorable situation in 2007. In particular, half of the Bolivian women depended on another person for their economic subsistence in 2007. Ecuador, on the other hand, registers the least progress in this indicator, ranking as the country with the highest percentage of economically vulnerable women in the Andean Region.

Figure 9 shows the ratio between men and women who work in urban areas and receive a salary. This indicator is related to the level of economic autonomy that a woman possesses. It shows how much a woman earns for every dollar earned by a man in each country. The first analytical interpretation is that there is no equitable relationship between wages. Regarding 2007, most of the countries have advanced towards more equal wages, except Peru, where this relationship has worsened. In 2017, Perú was the country where a woman’s salary has the most significant disadvantage compared to that of a man in the entire Andean Region. In 2007, this position was held by Bolivia. In contrast, the countries with the greatest wage equality are Ecuador, Argentina, and Colombia. Ecuador appears to be the country with the highest wage equity in the region since for every dollar a man earns; a woman earns 0.99 cents.

At this point of the comparative analysis, a critical comment should be made, since the SDG indicators enunciate gender equity from a heterosexual and binary logic (male-female), excluding and making invisible the so-called queer genders (Butler, 2007). For this reason, there is hardly any data showing the situation of these vulnerable genders. Hence the need to create new SDG indicators that include these gender perspectives to “leave no one behind”. In addition to fighting against all forms of misogyny, violence, and discrimination suffered by women and girls, it is also necessary to confront the different forms of discrimination and violence suffered by other genders, such as homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, and queerphobia (Tin, 2003).

To finish the comparative analysis, an indicator of women’s decision-making autonomy is presented. Figure 10 represents the percentage of women who hold a seat in the national parliament. The importance of this indicator lies in the fact that greater female participation would guide legislative discourses to expand and strengthen women’s rights (Cepal, 2017b).

It is relevant to note that all countries have experienced a percentage increase in women participating in parliamentary positions in 2017, except for Argentina and Peru, which show slight decreases. Overall, the balance is positive (ONU Mujeres, 2015). The countries with the highest representation in 2017 are Bolivia, Argentina, and Ecuador. Bolivia, in particular, presents gender parliamentary equity, with 53% of women occupying a seat. While these data are encouraging, the SDG data should begin to develop studies that include those LGBTI genders excluded by the binary logic of its indicators. A clear example is Brigitte Baptiste, the first trans woman to be a university rector in Colombia, or the case of Sarah McBride, the first transgender state senator in the United States.

Intercultural and decolonial conclusions to fulfill the SDGs in the Andean Region

Undoubtedly, economic disparity, child malnutrition, access to primary and secondary education, and gender inequality continue to be limiting factors in reducing poverty in the short, medium, and long term in the region. Beyond investigating and analyzing statistical data, scientists and academics have the ethical responsibility to formulate proposals that help governments and civil society to (re)think about public policies and regional cooperation strategies. The data and arguments of this research lead us to propose the intercultural and decolonial approach as a transversal axis in public policies to rescue the cultural practices, worldviews, and social demands of the Andean peoples (Candau, 2016).

In this sense, Mignolo (2003) argues that European intellectuals left out the rest of the epistemes and worldviews of Africa, America, Asia, and the Middle East. In other words, they called their own “local” experience and knowledge “universal” history, excluding the rest of the planet. This epistemic vision established colonial power relations that still persist today (Quijano, 2000). For Walsh (2003), coloniality is the hidden face of modernity, which still maintains in epistemological silence the knowledge that was subalternate and marginalized, considering it non-academic knowledge.

That is why many critical thinkers in Latin America advocate the establishment of intercultural projects that rescue this historically forgotten knowledge. Here it is pertinent to conceptualize the term “interculturality” as an alternative to the value system imposed by the Western idea of “development”. In this line of thought, Dietz (2017) reviews the anthropological and social science literature to classify the notion of interculturality according to three different complementary semantic axes:

1) The distinction between interculturality as a descriptive concept as opposed to a prescriptive one; 2) the underlying implicit assumption of a static notion of culture, as opposed to a dynamic notion; and 3) the rather functionalist application of the concept of interculturality, to analyze the status quo of a specific society, versus its critical and emancipatory application, to identify inherent conflicts and sources of societal transformation.11 (Dietz, 2017, p. 192, own translation).

Dietz (2017) uses these three semantic axes to organize the complex academic debate that addresses cultural diversity, with its respective worldviews and ways of life. As a whole, the definitions generated on interculturality point towards the visualization of decolonizing practices and discourses (Rivera, 2010). Exclusion, subalternation, and epistemological invisibilization have given way to historical structural violence that policymakers must confront in political and social spaces.

Another important proposal of this research is to initiate a process of revaluation of Andean rural customs since their deep spiritual sense of nature allows them to have more resilient and regenerative relationships (Viteri, 2002). A good example is Good Living, whose Inti Raymi ceremonies are celebrated during the winter solstice in June, with numerous offerings to the Pachamama to thank her for the harvests obtained.

This article also proposes to generate guidelines for governments, policymakers, and civil society to develop inclusive policy campaigns for the most disadvantaged social sectors, such as indigenous peoples and Afro-descendants. Discrimination, racism, and violence towards these peoples further aggravate poverty, exclusion, and inequity in the region.

From a deeper critical analysis, it is worth noting that the debates on intra- and interculturality in the region have been led by indigenous movements, and Afro-descendants have had little recognition (Bello & Rangel, 2002). Discourses on intercultural education and intercultural bilingual education have been marked by a strong indigenous vision, which has monopolized almost all the protagonism (Wade, 2008). In addition to the legal prohibition on racism in the 19th century, several Latin American countries implemented reforms in the 1980s and 1990s to recognize ethnic and racial subgroups of their national culture. However, many Afro-descendant peoples failed to assert themselves as an ethnic identity and were politically excluded (Hooker, 2006). Only a minority managed to assert a position similar to that of the indigenous people and achieved certain collective rights (Restrepo & Rojas, 2004).

Del Popolo et al. (2009) claim that the children of illiterate women of indigenous or Afro--descendant origin and belonging to Andean communities are the most vulnerable sector of the population to suffer from malnutrition. Given the invisibility of indigenous and Afro-American women in the statistical figures provided by the studies of organizations and universities, it is challenging to know their exact situation of poverty and educational level. Therefore, another fundamental proposal is to carry out more in-depth intersectoral studies that analyze these marginalized populations from an intercultural and inclusive approach.

Intersectoral analysis reveals hidden manifestations of oppression that co-constitute each other and give rise to multiple discrimination. The theory of intersectionality has an important academic recognition in the field of social justice, despite the difficulty in conceptualizing social hierarchies in a complex and multidimensional manner (Hirata, 2014). From the late 1960s and early 1970s, multiracial feminist movements began to denounce the social stratification of the time, and their intersectoral studies revealed multiple discriminations among the most disadvantaged sectors (Crenshaw, 1989).

For this reason, the debate on the fulfillment of the SDGs should be extended to include cross-cutting studies that help explain how systemic social injustice and inequality occur in a multidimensional manner among the most disadvantaged social sectors. Gender, race, ethnicity, and culture are variable analytical categories that we have constructed in the historical narratives of our peoples (Fivush et al., 2011). These studies would also contribute to critical development theory to decolonize and interculturalize the SDGs since the intersectoral approach shows how different biological, social, and cultural categories interact simultaneously at multiple levels of poverty, education, and gender. As shown in Table 1, around 12.25% of the Andean population is indigenous, and 4.95% is Afro-descendant. Herein lies the need to increase research and intersectoral studies to better understand the situation of multidimensional discrimination suffered by these social groups in the Andean Region, especially women and girls from rural sectors (Del Popolo, 2017).

TABLE 1 POPULATION OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND AFRO-DESCENDANTS OF THE ANDEAN REGION ACCORDING TO CENSUSES AND ESTIMATES

| Country and census year | Total population | Indigenous population | Indigenous peoples | Afro-descendant population** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nº | % | Nº | % | ||||

| Argentina, 2010 | 40,117,096 | 955,032 | 2.4 | 32 | 149,493 | 0.37 | |

| Bolivia, 2010* | 9,995,000 | 6,216,026 | 62.2 | 39 | 16,329 | 0.16 | |

| Chile, 2012 | 16,341,929 | 1,805,243 | 11 | 9 | No data | ||

| Colombia, 2010* | 46,448,000 | 1,559,852 | 3.4 | 102 | 4,689,000 | 10 | |

| Ecuador, 2010 | 14,483,499 | 1,018,176 | 7 | 34 | 1,041,559 | 7.2 | |

| Perú, 2010* | 29,272,000 | 7,021,271 | 24 | 85 | 828,841 | 2.85 | |

| Venezuela | 27,227,930 | 724,592 | 2.7 | 57 | 1,087,427 | 4 | |

| TOTAL | 157,540,654 | 19,300,192 | 12.25 | 358 | 7,812,649 | 4.95 | |

Source: Own elaboration based on Cepal (2014, p. 98 and 140), census information, and other sources.

*Cepal estimates. **Estimates from other sources.12

Although Table 1 does not show exact data, and each country’s census varies in some years, its sources are reliable and allow legislators and civil society organizations to have a more articulated sociodemographic perception of the regional situation. In the censuses carried out during the 2010s, the category “other people” was used, which made it possible to register the different indigenous peoples, where some peoples who were believed to have disappeared (re)appeared. According to estimates made by Cepal (2014), there are approximately 358 different denominations of indigenous peoples, which highlights the enormous and heterogeneous demographic and cultural diversity that exists in the Andean Region. To this estimation, we should add the indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation and the uncontacted, which are unknown. These censuses also revealed the fragility of many indigenous peoples, who are in danger of disappearing physically and culturally.

On the other hand, census information of the Andean countries and other consulted sources estimate that there are around 8 million Afro-descendants in our region. This supposes a large population that is still denied many social rights and suffers from multiple problems of racism, discrimination, and violence (Cepal, 2017c). Hence, the United Nations named the period 2015-2024 as the “International Decade for People of African Descent”, to address the conditions of structural inequity of these peoples and to establish the axes of recognition, justice, and development. Corbetta (2018) posits that territorial vulnerability, soil degradation, water pollution, malnutrition, food security, and high mortality are the factors that have the greatest impact on the low academic performance of indigenous and Afro populations in the Andean Region. Therefore, Table 1 aims to provide statistical data highlighting the situations of multiple discrimination suffered by these ethnically and racially diverse peoples.

According to García (2001) and Moya (1999), there is a strong relationship between knowledge, identity, and territory that is a central axis in the lives of indigenous and Afro communities. However, the wisdom acquired by these peoples over centuries does not appear in books, school curriculum, or university analyses. Nor are there any studies that highlight the academic performance of populations that suffer discrimination based on their economic, gender, ethnic, racial, or territorial status. For this reason, it is important to deepen educational cooperation in the Andean Region through an inclusive approach to cultural diversity (González & De la Torre, 2004).

In this regard, this research proposes the creation of didactic materials of Afro and indigenous cultures to be taught in the educational curriculum of each member country of the Andean Region. Public policies should also be created to help these historically mistreated peoples move up the social ladder, especially in schools, institutes, and universities. Moreover, the cultural wealth of these peoples must be disseminated and communicated at an interregional level. It is recommended that governments and civil society in the Andean countries work on plans, strategies, and policies that transform the State and Nation model to include an intercultural and plurinational vision that puts an end to the colonial and post-colonial racism that is structurally rooted in the societies of the region. These proposals should be implemented primarily in rural areas, where there are higher poverty rates, illiteracy, school dropouts, gender inequality, violence, and femicides.

In sum, these proposals should aim to achieve SDG 1, 4, and 5, for which it is necessary to adopt a geopolitical perspective that analyzes the physical, territorial, and epistemic marginalization still suffered by indigenous and Afro peoples of the Andean Region. From a critical and decolonial vision, it is concluded that the epistemic approach adopted by the SDGs does not contribute to decolonizing power-knowledge-being since they ignore and marginalize social and solidarity economy alternatives to achieve food and energy sovereignty. In fact, the SDGs still fail to recognize the economy as a subsystem of the Earth System (Duarte, 2006), which implies recognizing the laws of thermodynamics in the limits of economic growth (Ayres, 1998; Daly, 2014; Georgescu, 2011).

This failure to question economic growth is due to the current model of modern development. The notion of “development” implicit in the SDGs is inspired by the three sustainability (economic, social, and environmental) that the World Bank reinterpreted on the original concept of “sustainable development” postulated in the Brundtland (1987). Hence, the SDGs do not propose limiting the power of transnational corporations, which already surpass the power of nation-states and control markets to monopolize and degrade the productive factors of land, labor, and capital (Stiglitz et al., 2010). Nor do the SDGs recommend limiting the accumulation in a few hands of the means and resources that make it possible to improve the levels of well-being of citizens (Oxfam, 2016). Nor do they propose the depatriarchalizing and deheteronormalization of the notion of gender.

For these reasons, there are many critical voices that demand a profound change in the “universal” formulation of the SDGs (Domínguez, 2016). It is urgent to address the SDGs from a pluri--paradigmatic axis of enunciation that includes historically marginalized cosmovisions, epistemes, knowledge, and socio-environmental practices. This implies a paradigm based on intercultural, decolonial, postmodern, post-capitalist, and biocentric principles. As Steffen et al. (2007) argue, we do not have much time to debate, as the serious impact of human activity on our planet has led to the “Anthropocene”, a geological epoch that the scientific community recognizes for the global change caused. We must act quickly and develop public policies, plans, and strategies for regional cooperation to ensure the well-being of humanity and nature. This means going beyond the civilizational paradigm based on the anthropocentric pillars of modernity and capitalism. These cooperative actions between governments, civil society, and the private sector must include the wisdom of the Andean cosmovision, which recognize nature as a subject of rights, with spiritual and sacred values (Simon, 2013). Are you ready? Readers are encouraged to work along these lines of critical thinking and collaborative work.

Acknowledgment

Funded by the Universidad Nacional de Educación de Ecuador under the VIP-UNAE-2017-5 research project “Educación y pobreza en Ecuador: factores, desafíos y propuestas para la transformación educativa y el desarrollo sostenible”.

REFERENCES

Acosta, A. (2013). Buen vivir/sumak kawsay. Icaria. [ Links ]

Ayres, R. (1998). Turning Point. The End of the Growth Paradigm. Earthscan. [ Links ]

Bautista, R. (2010). Hacia una constitución del sentido significativo del “Vivir Bien”. Rincón Ediciones. [ Links ]

Bello, A., & Rangel, M. (2002). Equity and exclusion in Latin America and the Caribbean: The Case of Indigenous and Afro-descendant Peoples. CEPAL Review, (76), 39-53. [ Links ]

Brundtland, H. (Dir.). (1987). Our Common Future. United Nations. [ Links ]

Butler, J. (2007). El género en disputa. Paidós. [ Links ]

Candau, V. (2016). Cotidiano escolar e práticas interculturais. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 46(161), 802-820. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053143455 [ Links ]

Claro, J. (2007). Estado y desafíos de la inclusión educativa en las regiones andina y cono sur. REICE - Revista Electrónica Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 5(5), 179-187. [ Links ]

Collado, J. (2016). Epistemología del Sur: Una visión descolonial a los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. Sankofa: Revista de História da África e de Estudos da Diáspora Africana , 9(17), 137-158. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1983-6023.sank.2016.119065 [ Links ]

Collado, J., Madroñero, M., & Álvarez, F. (2019). Training transdisciplinary educators: Intercultural learning and regenerative practices in Ecuador. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 38(2), 177-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11217-019-09652-5 [ Links ]

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe - Cepal. (2014). Los pueblos indígenas en América Latina: Avances en el último decenio y retos pendientes para la garantía de sus derechos. Cepal. [ Links ]

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe - Cepal. (2017a). Brechas, ejes y desafíos en el vínculo entre lo social y lo productivo. Cepal. [ Links ]

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe - Cepal. (2017b). Planes de igualdad de género en América Latina y el Caribe. Mapas de ruta para el desarrollo. Cepal. [ Links ]

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe - Cepal. (2017c). Situación de las personas afrodescendientes en América Latina y desafíos de políticas para la garantía de sus derechos. Cepal. [ Links ]

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe - Cepal. (2020). Base de datos integrada CEPALSTA. https://estadisticas.cepal.org/cepalstat/WEB_CEPALSTAT/buscador.asp [ Links ]

Corbetta, S. (Coord.). (2018). Educación intercultural bilingüe y enfoque de interculturalidad en los sistemas educativos latinoamericanos. Cepal. [ Links ]

Craig, M. (2017). Ecological political economy and the socio-ecological crisis. Palgrave. [ Links ]

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of discrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracistpolitics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, (1), 139-167. [ Links ]

Daly, H. (2014). From uneconomic growth to a steady-state economy. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

Dávalos, P. (2008). Reflexiones sobre el sumak kawsay (el buen vivir) y las teorías del desarrollo. Boletín ICCI-ARY Rimay, (113). http://icci.nativeweb.org/boletin/113/davalos.html [ Links ]

De Sousa, B. (2009). Una epistemología del Sur: La reinvención del conocimiento y la emancipación social. Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

Del Popolo, F. (2017). Los pueblos indígenas en América (Abya Yala): Desafíos para la igualdad en la diversidad. Cepal. [ Links ]

Del Popolo, F., López, M., & Acuña, M. (2009). Juventud indígena y afrodescendiente en América Latina: Inequidades sociodemográficas y desafíos de políticas. Cepal. [ Links ]

Dietz, G. (2017). Interculturalidad: Una aproximación antropológica. Perfiles Educativos, 39(156), 192-207. [ Links ]

Domínguez, R. (2016). Pensando críticamente la nueva agenda de los ODS. In J. Agudelo, & A. G. Rodríguez (Eds.), La cooperación internacional en transición 2015-2030: Análisis global y experiencias para Colombia (pp. 11-16). Universidad de San Buenaventura. [ Links ]

Duarte, C. (Coord.). (2006). Cambio global: Impacto de la actividad humana sobre el sistema tierra. CSIC. [ Links ]

Escobar, A. (1996). La invención del tercer mundo. Construcción y deconstrucción del desarrollo. Norma. [ Links ]

Esteva, G. (1997). El mito del desarrollo sustentable. Ojarasca. [ Links ]

Fivush, R., Habermas, T., Waters, T., & Zaman, W. (2011). The making of autobiographical memory: Intersections of culture, narratives and identity. International Journal of Psychology, 46(5), 321-345. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2011.596541 [ Links ]

García, Á. (2010). El socialismo comunitario. Un aporte de Bolivia al mundo. Revista de Análisis - Reflexiones sobre la coyuntura, 3(5), 7-18. [ Links ]

García, F. (2001). Política, Estado y diversidad cultural. La cuestión indígena en la región andina. Nueva sociedad, (173), 94-103. [ Links ]

Georgescu, N. (2011). From bioeconomics to degrowth. Routledge. [ Links ]

González, I., & De la Torre, M. (2004). La cooperación educativa internacional ante la diversidad cultural: Un estudio comparativo en la región andina. Revista Española de Educación Comparada, (10), 237-273. [ Links ]

Gudynas, E. (2011). Buen vivir: Germinando alternativas al desarrollo. América Latina en Movimiento, (462), 1-20. [ Links ]

Hidalgo, A., & Cubillo, A. (2016). Transmodernidad y transdesarrollo. Bonanza. [ Links ]

Hidalgo, A., García, S., Cubillo, A., & Medina, N. (2019). Los objetivos del Buen Vivir: Una propuesta alternativa a los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. Iberoamerican Journal of Development Studies, 8(1), 6-57. https://doi.org/10.26754/ojs_ried/ijds.354 [ Links ]

Hirata, H. (2014). Gênero, classe e raça: Interseccionalidade e consubstancialidade das relações sociais. Tempo Social: Revista de Sociologia da USP, 26(1), 61-73. [ Links ]

Hooker, J. (2006). Inclusão indígena e exclusão dos afro-descendentes na América Latina. Tempo Social: Revista de Sociologia da USP, 18(2), 89-111. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-20702006000200005 [ Links ]

Kowii, A. (2011). El Sumak Kawsay. Revista Electrónica Aportes Andinos, (28), 1-5. [ Links ]

Larrañaga, O., Contreras, D., & Cabezas, G. (2014). Políticas contra la pobreza: De Chile solidario al ingreso ético familiar. PNUD. [ Links ]

Latouche, S. (2006). Le Pari de la décroissance. Fayard. [ Links ]

Maldonado, N. (2008). La descolonización y el giro des-colonial. Revista Tabula Rasa, (9), 61-72. [ Links ]

Martínez, J. (2009). El ecologismo de los pobres: Conflictos ambientales y lenguajes de valoración. Icaria. [ Links ]

Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., & Behrens, W. (1972). Los límites del crecimiento. Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Mignolo, W. (2003). Historias locales/diseños globales: Colonialidad, conocimientos subalternos y pensamiento fronterizo. Akal. [ Links ]

Mignolo, W. (2007). La idea de América Latina. Gedisa. [ Links ]

Moya, R. (Ed.). (1999). Interculturalidad y Educación: Diálogo para la democracia en América Latina. La interculturalidad en la educación bilingüe para poblaciones indígenas de América Latina. Abya-Yala. [ Links ]

Naciones Unidas - ONU. (2015). Los Objetivos de Desarrollo del Milenio (Informe 2015). ONU. [ Links ]

Naredo, J. M. (2000). Insostenibilidad ecológica y social del “desarrollo económico” y la brecha norte-sur (Tema Central). Revista Ecuador Debate, (50), 171-203. http://hdl.handle.net/10469/5212 [ Links ]

Oberhuber, T. (2004). Camino de la sexta gran extinción. Ecologista, (41). [ Links ]

Observatorio de Igualdad de Género de América Latina y el Caribe. (2020). Autonomías. https://oig.cepal.org/es/autonomias [ Links ]

ONU Mujeres. (2015). El progreso de las mujeres en el mundo 2015-16: Transformaciones económicas para realizar los derechos. ONU Mujeres. https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2015/poww-2015-2016-es.pdf?la=es&vs=0 [ Links ]

Organización Panamericana de la Salud - OPS. (2016). Acelerar el progreso hacia la reducción del embarazo en la adolescencia en América Latina y el Caribe (Informe de consulta técnica). PAHO. https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/34853/9789275319765_spa.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [ Links ]

Oxford Committe for Famine Relief - Oxfam. (2016). Una economía al servicio del 1%: Acabar con los privilegios y la concentración de poder para frenar la desigualdad extrema (Informe n. 210). [ Links ]

Pauli, G. (2017). The third dimension: Restoring natural resources & the environment to rebuild communities. JJK Books. [ Links ]

Pievani, T. (2014). The sixth mass extinction: Anthropocene and the human impact on biodiversity. Rendiconti Lincei. Scienze Fisiche e Naturali, 25(1), 85-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12210-013-0258-9 [ Links ]

Quijano, A. (2000). Colonialidad del poder y clasificación social. Journal of World Systems Research, 6(2), 342-386. [ Links ]

Ramírez, R. (2010). Socialismo del sumak kawsay o bioigualitarismo republicano. Senplades. [ Links ]

Restrepo, E., & Rojas, A. (Eds.). (2004). Conflicto e (in)visibilidad: Retos en los estudios de la gente negra en Colombia. Ed. Universidad del Cauca. [ Links ]

Rivera, S. (2010). Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: Una reflexión sobre prácticas y discursos descolonizadores. Tinta Limón. [ Links ]

Sachs, J. (2005). El fin de la pobreza: Cómo conseguirlo en nuestro tiempo. Debate. [ Links ]

Sen, A. (2009). La idea de la justicia. Taurus. [ Links ]

Simon, F. (2013). Derechos de la naturaleza: ¿Innovación trascendental, retórica jurídica o proyecto político? Iuris Dictio. Revista del Colegio de Jurisprudencia de la Universidad San Francisco de Quito, 13(15), 9-38. https://doi.org/10.18272/iu.v13i15.713 [ Links ]

Steffen, W., Crutzen, P., & McNeill, J. (2007). The anthropocene: Are humans now overwhelming the great forces of nature? AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 36(8), 614-621. [ Links ]

Stiglitz, J., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J. (2010). Mis-measuring our lives: Why GDP doesn´t add up. The report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. The New Press. [ Links ]

Sustainable Development Solutions Network - SDSN. (2018). SDSN Networks in action 2018. UNSDSN. [ Links ]

Tin, L. (Ed.). (2003). Dictionnaire de l’homophobie. Presses Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

Tortosa, J. M. (2009). Maldesarrollo como mal vivir. América Latina en Movimiento, (445), 18-21. [ Links ]

United Nations - UN. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. UN. [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization - Unesco. (2015). EFA Global Monitoring Report 2015. Education for All 2000-2015: Achievements and Challenges. Unesco. [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization - Unesco. (2020a). World Inequality Database on Education - Wide. https://www.education-inequalities.org/ [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization - Unesco. (2020b). Glosario de indicadores de educación. http://uis.unesco.org/en/glossary-term/adjusted-net-enrolment-rate [ Links ]

Viteri, A., Tapia, M., Vargas, A., Flores, E., & Gonzáles, G. (1992). Plan Amazanga: Formas de manejo de los recursos naturales en los territorios indígenas de Pastaza, Ecuador. OPIP. [ Links ]

Viteri, C. (2002). Visión indígena del desarrollo en la Amazonía. Polis - Revista Académica Universidad Bolivariana, 1(3), 1-6. [ Links ]

Wackernagel, M., & Rees, W. E. (1996). Our Ecological Footprint. New Society. [ Links ]

Wade, P. (2008). Población negra y la cuestión identitaria en América Latina. Universitas Humanística, 65(65), 117-137. [ Links ]

Walsh, C. (2003). Estudios culturales latinoamericanos: Retos desde y sobre la región andina. Abya-Yala. [ Links ]

World Bank. (2019). Effects of the Business Cycle on Social Indicators in Latin America and the Caribbean: When Dreams Meet Reality (LAC Semiannual Report), World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/31483/9781464814136.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y [ Links ]

World Bank. (2020a). Indicator. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator [ Links ]

World Bank. (2020b). Universal Health Coverage Data. http://datatopics.worldbank.org/universal-health-coverage/ [ Links ]

Yunus, M. (2007). Creating a world without poverty. Social business and the future of capitalism. Public Affairs. [ Links ]

1The impoverishment risk indicator is the percentage of people at risk of facing impoverishing medical expenses, which is defined as an individual’s medical payments that bring him or her below the poverty line.

2This index shows the disparities in the incidence of poverty (extreme poverty) between women and men. A value above 100 indicates that extreme poverty affects women to a greater degree than men; a value below 100, the opposite situation. There is no data for Venezuela for 2017.

3The percentage of total national income corresponding to population subgroups according to their income level. Quintiles 1 and 5 represent the lowest and highest income population subgroups. The sum of the percentages for all quintiles may not add up to 1 due to rounding. No data were available for Venezuela in 2017.

4People who answer “no” to the question “Can you read and write?”. For Argentina, this indicator is only available in the urban area and the national or rural rates are not included. In the case of Venezuela, this indicator is available at the national level, without urban or rural disaggregation.

5The net enrollment rate for primary education corresponds to the ratio between the number of students of primary school age enrolled in primary education and the total population that is of primary school age.

6The net enrollment rate in secondary education corresponds to the ratio between the number of students of secondary school age enrolled in secondary education and the total population of secondary school age. The values in the figure indicate the national rate.

7The secondary completion rate is obtained as the ratio of people who have completed secondary education divided by the total population between the ages of 20 and 29. The information corresponds to different years and has been obtained from https://www.education-inequalities.org/

8The proportion of the female and male population over 15 years of age who are not individual income earners and who are not studying (according to their activity status), in relation to the total of the female and male population aged 15 and over who are not studying.

9The ratio of the average wage of urban female wage earners, aged 20-49, working 35 hours or more per week, to each dollar of men’s wages with the same characteristics. Information was not available for Venezuela in 2017.

10Women members of parliaments are the number of women who occupy seats in a lower house or a single house. This number is divided by the total members within these instances.

11In the original: “1) La distinción entre la interculturalidad como un concepto descriptivo en oposición a otro prescriptivo; 2) la subyacente asunción implícita de una noción de cultura estática, en oposición a una noción dinámica; y 3) la aplicación más bien funcionalista del concepto de interculturalidad, a fin de analizar el status quo de cierta sociedad, versus su aplicación crítica y emancipatoria, para identificar los conflictos inherentes y las fuentes de transformación societaria”.

12Estimates of Afro-descendants in: Argentina (2010) w.censo2010.indec.gov.ar/cuadrosDefinitivos/Total_pais/P42-Total_pais.xls Bolivia (2012) www.cedib.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Tabla-Poblacion-Indigena1.pdf Colombia (2005) www.dane.gov.co/files/censo2005/etnia/sys/visibilidad_estadistica_etnicos.pdf Ecuador (2011) https://www.eluniverso.com/2011/10/12/1/1447/censo-revela-aumento-poblacion-afro-indigena.html Perú (2017) https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1539/libro.pdf Venezuela (2011) www.ine.gob.ve/documentos/Demografia/CensodePoblacionyVivienda/pdf/nacional.pdf

Received: March 30, 2020; Accepted: February 08, 2021

texto em

texto em